Abstract

Two bidentate dihomooxacalix[4]arene receptors bearing phenylurea moieties substituted with electron-withdrawing groups at the lower rim via a butyl spacer (CF3-Phurea 5b and NO2 Phurea 5c) were obtained in the cone conformation in solution, as shown by NMR. The X-ray crystal structure of 5b is reported. The binding affinity of these receptors toward several relevant anions was investigated by 1H NMR, UV-Vis absorption in different solvents, and fluorescence titrations. Compounds 5b and 5c were also tested as ditopic receptors for organic ion pairs, namely monoamine neurotransmitters and trace amine hydrochlorides by 1H NMR studies. The data showed that both receptors follow the same trend and, in comparison with the unsubstituted phenylurea 5a, they exhibit a significant enhancement on their host-guest properties, owing to the increased acidity of their urea NH protons. NO2-Phurea 5c is the best anion receptor, displaying the strongest complexation for F−, closely followed by the oxoanions BzO−, AcO−, and HS. Concerning ion pair recognition, both ditopic receptors presented an outstanding efficiency for the amine hydrochlorides, mainly 5c, with association constants higher than 109 M−2 in the case of phenylethylamine and tyramine.

Keywords: dihomooxacalix[4]arenes, phenylurea anion receptors, biogenic amine hydrochlorides, ditopic receptors, proton NMR titrations, UV-Vis absorption studies, fluorescence studies, X-ray diffraction

Introduction

Anion recognition by synthetic receptors continues to attract much attention, as documented by the reviews published recently (Evans and Beer, 2014; Busschaert et al., 2015; Gale et al., 2016). Anions play essential roles in numerous biological systems, as well as in many environmental and industrial processes.

Macrocyclic compounds have been developed as anion receptors, in which the interactions are mainly established by hydrogen bond donor groups, such as ureas and thioureas, incorporated in the macrocycle scaffolds. These receptors are able to recognize anions with different geometries through effective and directional H-bonds. However, to bind a charged species these monotopic receptors need to overcome the tendency of the target ion to form an ion pair with its counter ion, especially in non-polar solvents. Thus, heteroditopic receptors, molecules capable of simultaneously bind both ions of a given ion pair, have been obtained and are an emerging area in supramolecular chemistry (Kim and Sessler, 2010; McConnell and Beer, 2012). These systems have important applications, as membrane transport agents, and in salt extraction and solubilisation. The binding ability of these ditopic receptors toward organic ion pairs, namely ammonium and amino acid salts, has been more investigated in the last years. Alkylammonium moieties are a constant presence in compounds of biological interest, such as biogenic amines, trace amines and amino acids (Mutihac et al., 2011).

Calixarenes are a particularly attractive class of macrocyclic compounds owing to the relatively ease functionalization of both the upper and the lower rims, and to the presence of a pre-organized cavity available in different sizes and conformations (Gutsche, 2008). These compounds have been largely used as anion receptors. In particular, calix[4]arenes (Quinlan et al., 2007; Babu et al., 2009; Curinova et al., 2009; De Solis et al., 2015; Klejch et al., 2016; Rezankova et al., 2017) and calix[6]arenes (Hamon et al., 2008; Nehra et al., 2016) bearing phenylurea moieties incorporating electron-withdrawing groups, such as NO2 and CF3, have been investigated. These groups are expected to increase the acidity of the urea NH protons, thus enhancing the anion binding ability of the receptors. Calixarenes have also been used as building blocks for the construction of ditopic receptors able of simultaneous binding of anions and cations. Examples of such receptors based on calix[4] (Pescatori et al., 2009), calix[5] (Capici et al., 2010), and mainly calix[6]arenes (Hamon et al., 2008; Lascaux et al., 2010; Cornut et al., 2015; Moerkerke et al., 2017) are reported in the literature.

In the course of our studies on anion binding by disubstituted dihomooxacalix[4]arenes (calix[4]arene analogs in which one CH2 bridge is replaced by one CH2OCH2 group) (Marcos, 2016) with phenylurea units (Marcos et al., 2014a,b), we were interested in determine the enhancement on the anion binding affinity of the receptors by the introduction of electron-withdrawing groups. Along with this research, the phenylurea derivatives were also evaluated as ditopic receptors (Gattuso et al., 2015). They combine in the same molecule two different binding sites, i.e., an ureido anionic site and a hydrophobic cavity suitable for organic cations.

In this paper we describe the synthesis of two new disubstituted dihomooxacalix[4]arenes bearing, via a butyl spacer, para CF3- (5b) or NO2-phenylurea (5c) moieties, at the 1,3-positions of the lower rim. The host-guest properties of these receptors, obtained in the cone conformation, toward several relevant anions were established by proton NMR and UV-Vis absorption titrations in chloroform (or dichloromethane) and acetonitrile. Some photophysical properties of these receptors (due to their intrinsic fluorescence) were evaluated and, in a few cases, fluorescence studies were also performed to investigate the calixarene binding affinity. These dihomooxa derivatives were also tested as heteroditopic receptors for n-alkylammonium chlorides, and monoamine neurotransmitters and trace amine hydrochlorides by proton NMR studies. The results are compared to those obtained with the analog unsubstituted phenylurea (5a). The solid state structure of 5b is also presented.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Structural Analysis

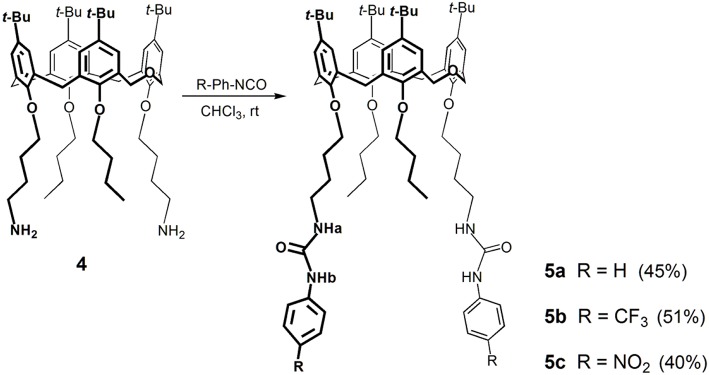

Previously, we have reported the synthesis of a lower rim 1,3-disubstituted dihomooxacalix[4]arene receptor containing two phenylurea moieties and two n-butyl groups (Marcos et al., 2014a). Following this line of research, we synthesized two new ureido-dihomooxacalix[4]arenes bearing CF3 or NO2 groups at the p-position of the phenylurea moiety, via a butyl spacer. The binding ability of these receptors is expected to be increased by the introduction of the electron-withdrawing groups. Thus, the alkylation reaction of the parent p-tert-butyldihomooxacalix[4]arene (1) with 4-bromobutyronitrile and K2CO3 gave the dicyano-dihydroxy compound 2, which was further alkylated with n-butyl iodide and NaH, yielding the dicyano-dibutoxy derivative 3. Reduction of the cyano groups with NaBH4/CoCl2 afforded diamine 4. These reactions and products were already described (Marcos et al., 2014a). Diamine 4 reacted with p-(trifluoromethyl)- or p-nitro-phenylisocyanate to yield the corresponding p-CF3-phenylurea 5b and p-NO2-phenylurea 5c, in the cone conformation (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of the phenylurea receptors 5a–5c.

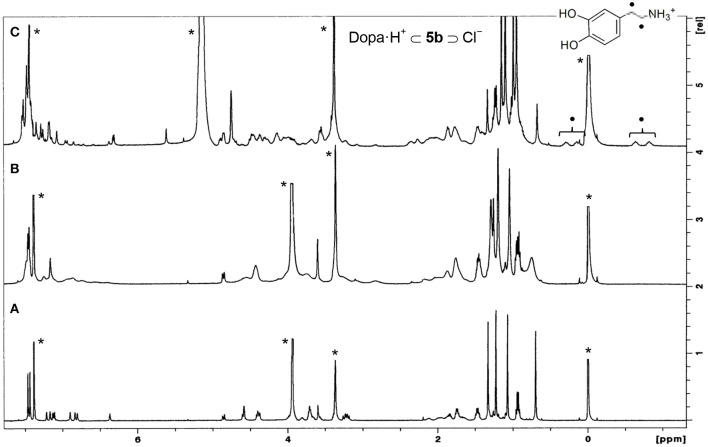

These receptors are inherently chiral, as indicated by their NMR spectra in CDCl3. The proton spectra show four singlets for the tert-butyl groups, five AB quartets for the CH2 bridge protons, four pairs of doublets for the aromatic protons, and two triplets and two singlets for the NHa and NHb protons, respectively. The aromatic and NH region of the three phenyl ureas is shown in Figure 1. Increasing downfield shifts for the NH protons, mainly the NHb, can be observed from Phurea 5a to NO2-Phurea 5c, indicating the increased acidity of these protons. Moreover, the proton spectra display two triplets and several multiplets for the methyl and methylene protons of the butyl spacers and n-butyl groups. The 13C spectra exhibit three ArCH2Ar resonances in the range 28.8–31.5 ppm, indicative of a cone conformation (Jaime et al., 1991). The proton assignments were confirmed by COSY spectra.

Figure 1.

1H NMR partial spectra (500 MHz, CDCl3, 25°C) of: (A) Phurea 5a, (B) CF3-Phurea 5b, and (C) NO2-Phurea 5c.

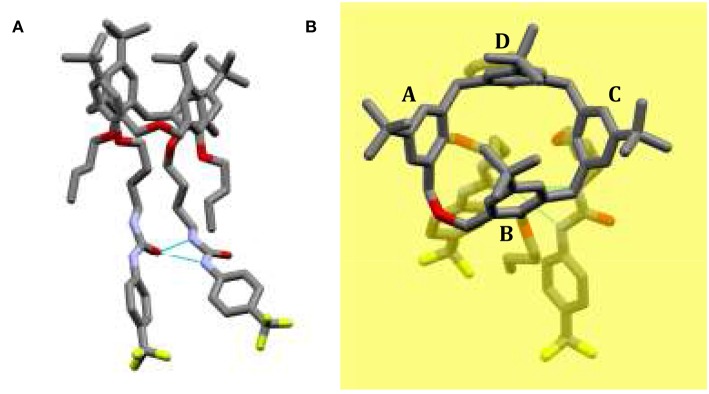

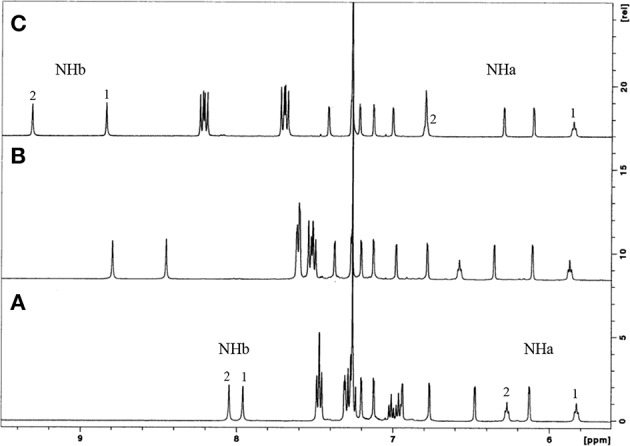

Small colorless single crystal needles were obtained by slow evaporation of a chloroform solution containing compound 5b. The X-ray structure was determined using synchrotron radiation with crystals frozen at 100 K. The asymmetric unit of the monoclinic crystal (space group P21/c) is composed of one molecule of 5b and a disordered co-crystallized chloroform solvent molecule with a total occupancy factor of 0.7. The dihomooxacalixarene macrocycle adopts the expected cone conformation, producing an inherently chiral molecule due to the 1,3-substitution pattern on the lower rim (Figure 2, rings A and C). The centrosymmetric space group implies the presence of a racemic mixture of the two enantiomers in the crystals. The mean planes of the two ureido substituted phenyl rings (A and C) make large outward (dihedral) angles of 125° and 131°, respectively, with respect to the dihomooxacalixarene mean plane, defined by the methylene bridging groups (Figure 2B). With regard to the butoxy substituted phenyl rings, the one connected with the homooxo bridge (B) shows a mean plane of the phenyl ring inclined inwards with a dihedral angle of 66°. As a result, its p-tert-butyl group partially occupies the calixarene cavity. The facing butoxy substituted phenyl ring (D) is inclined slightly outwards, with a dihedral angle of 101°. Consistently with previous reports, the ureido groups form an intramolecular N–H···O bifurcated hydrogen bond (Marcos et al., 2014b; Augusto et al., 2018). In this case the H-bond is rather asymmetric, with the N···O distance of the NH directly bonded to the phenyl ring, para to the electron-withdrawing CF3 group, shorter with respect to the other N···O distance (2.89 vs. 3.06 Å). The relative orientations of the skeletons of the NCON ureido moieties show a mean plane dihedral angle of 28°, while the terminal phenyl groups form dihedral angles of about 20° (Ring A) and 40° (Ring C) with respect to their corresponding planar ureido groups. The overall result is that these phenyl groups show a dihedral angle of about 74° between their mean planes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Solid state structure of CF3-Phurea 5b. (A) The molecule shows a cone conformation, with the phenylureido moieties involved in an intramolecular N–H···O bifurcated hydrogen bond. (B) Orthogonal view of 5b with respect to the dihomooxacalixarene mean plane (yellow) defined by the methylene bridging groups.

The crystal packing shows that the ureido groups are involved in an intermolecular N–H···O hydrogen bonds network. More specifically, one-dimensional chains of bifurcated H-bonds, formed by iso-orientated calixarenes (generated by crystallographic glide planes), are propagated antiparallel along the c-axis (Figure 3). The resulting intermolecular N···O distances show that these bifurcated intermolecular H-bonds are even more asymmetric than the intramolecular H-bonds. In this case the NH group directly bound to the phenyl ring forms a weaker H-bond with the carbonyl oxygen of a symmetry related molecule in comparison to the second NH group (N···O distances are 3.14 and 2.85 Å, respectively). The antiparallel chains are related by crystallographic screw axes and stacked along the b-axis with the calix cups facing the CF3-phenyl rings (Figure 3). The chloroform molecules at partial occupancy fill the voids created by the crystal packing of the calixarene molecules.

Figure 3.

Crystal packing of 5b shows two chains of bifurcated N–H···O hydrogen bonds from NH donors to O acceptor. The one-dimensional chains propagate along the c axis in antiparallel fashion.

The comparison with the solid state structure of 5a containing two crystallographic independent molecules, previously reported (Gattuso et al., 2015), shows an analogous crystal packing arrangement, despite the significant differences in the unit cells and the different space groups. However, in 5a the orientations of the NHCONH ureido moieties are quite different in the two crystallographic independent molecules, being almost parallel in one (similar to the conformation found in 5b) and orthogonally oriented in the other (Gattuso et al., 2015). For each independent molecules of 5a, the cone macrocycle adopts a similar conformation to 5b, in which the p-tert-butyl groups of the B rings lean into the cavity. More specifically, for the molecule with the almost parallel orientation of the ureido groups, the four dihedral angles formed by the mean planes of the phenyl rings and the dihomooxacalixarene bridging mean plane are within two degrees of the molecule found in 5b. On the other hand, the 5a molecule having an orthogonal orientation of the NHCONH ureido moiety shows a more open cone conformation (121, 74, 137, 97° for A, B, C, and D angles, respectively). This comparison suggests that the openness of the cone is to some degree related to the conformation and reciprocal orientation of the NHCONH ureido moieties.

Photophysical Properties

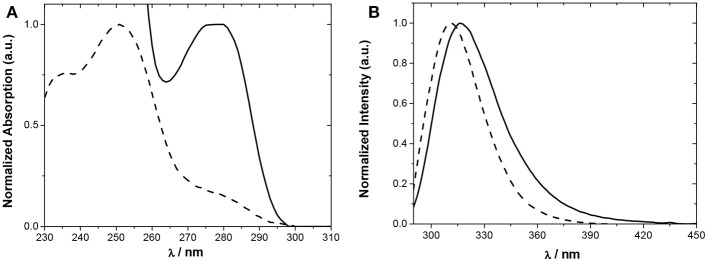

Owing to the intrinsic fluorescence of receptors 5, and to evaluate the changes caused by the introduction of the substituent groups at the p-position of the phenylurea ring, some photophysical properties of 5a and 5b were determined, following previous studies (Miranda et al., 2017).

The absorption and steady-state fluorescence spectra of Phurea 5a and CF3-Phurea 5b in dichloromethane are shown in Figure 4. The compounds present a well-defined absorption in the UV region, exhibiting a blue shift of 28 nm for 5b (Figure 4A). The same trend is observed in the emission spectrum, the normalized spectra being again similar for both compounds (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Normalized spectra of 5a (5.0 × 10−5 M; solid line) and 5b (5.0 × 10−6 M; dashed line) in CH2Cl2. (A) Absorption and (B) emission.

Relevant photophysical properties of the two Phureas are collected in Table 1. Stokes shifts were calculated as the difference between the excitation and the emission peak wavelengths. The results show that CF3-Phurea 5b presents a higher value compared to 5a. The fluorescence lifetimes (τf) and quantum yields (ϕF) were also determined. Overall, fluorescence lifetimes and yields do not change much upon para substitution, the fluorescence quantum yields are significant (0.2–0.6) and lifetimes moderate (1–2 ns). The quantum yield decreases and the lifetime increases upon para substitution, both effects resulting mainly from a decrease of the radiative rate constant (kr) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Photophysical properties of Phureas 5a and 5b in CH2Cl2 at 25°C.

| λmax, abs (nm) | λmax, em (nm) | ε (M−1 cm−1) | Stokes shifta (nm) | τf (ns) | ϕF | kr (ns−1) | knr (ns−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5a | 278 | 316 | 5.0 × 103 | 38 | 1.15 | 0.59b | 0.51 | 0.36 |

| 5b | 250 | 310 | 7.1 × 104 | 60 | 1.57 | 0.21c | 0.13 | 0.50 |

Compute as λmax,em− λmax,abs.

Against quinine sulfate ϕF = 0.60 in HCl 0.1 M.

Against tryptophan ϕF = 0.12 in water.

Anion Recognition

Proton NMR Studies

The binding properties of bidentate CF3-Phurea 5b and NO2-Phurea 5c toward several relevant anions of different geometries (spherical, linear, trigonal planar, and tetrahedral) were studied in CDCl3 through 1H NMR titrations using tetrabutylammonium (TBA) salts. The association constants (as log Kass) reported in Table 2 were determined using the WinEQNMR2 program (Hynes, 1993) and following the urea NH chemical shifts. In a few cases where those protons became broad or disappeared, the association constants were calculated through the complexation induced shifts of the aromatic protons of the calixarene skeleton.

Table 2.

Association constants (log Kass)a of dihomooxa ureas 5a-5c determined by 1H NMR in CDCl3 at 25°C.

| Spherical | Linear | Trigonal planar | Tetrahedral | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F− | Cl− | Br− | I− | CN− | SCN− | N | AcO− | BzO− | HS | H2P | Cl | |

| I. Radius/Åb | 1.33 | 1.81 | 1.96 | 2.20 | 1.91 | 2.13 | 1.79 | 2.32 | — | 1.90 | 2.00 | 2.40 |

| Phurea 5ac | 3.10 | 2.73 | 2.23 | 1.59 | 2.71 | 1.90 | 2.42 | 2.88 | 2.93 | 2.58 | 2.69 | 1.65 |

| CF3-Phurea 5b | 3.48 | 3.12 | 2.68 | 2.18 | 3.13 | 2.18 | 2.68 | 3.34 | 3.46 | 3.07 | 3.15 | 2.04 |

| NO2-Phurea 5c | 3.88 | 3.65 | 3.07 | 2.65 | 3.66 | 2.67 | 3.15 | 3.67 | 3.83 | 3.61 | 3.49 | 2.37 |

Hydrogen bonding interactions between the anions and the urea groups of the receptors were clearly evidenced by the downfield shifts of their NH protons, as shown in Figure 5. In all the studied cases, the complexation process occurs under fast exchange conditions on the NMR time scale at room temperature. The titration curves obtained (Figure S1) indicate the formation of 1:1 host-guest complexes. This stoichiometry was also confirmed by Job plots (Figure S2).

Figure 5.

Partial 1H NMR spectra of NO2-Phurea 5c (500 MHz, CDCl3, 25°C) with several equiv of TBA Cl.

The anion binding results obtained by proton NMR titrations (Table 2) show that both phenylureas bearing the electron-withdrawing groups CF3 and NO2 are better receptors than Phurea 5a (with no substituents), due to the increased acidity of their NH protons. All the receptors follow the same trend: the association constants decrease in general with decreasing anion basicity. The data show that NO2-Phurea 5c is the best anion receptor, exhibiting high association constants. Among the spherical halides, 5c displays the strongest complexation for F− (log Kass = 3.88). The results with F− showed no evidence for the formation of the H species (Amendola et al., 2006, 2010; Babu et al., 2009) Although the acidity of Phureas 5b and 5c is higher compared to that of 5a, the solvent used, chloroform, is a weakly competitive one, contributing to stabilize the H-bond complexes. Moreover, small downfield and upfield shifts for the ortho and meta protons, respectively, of the phenylurea groups of 5c were also observed (Figure S3), corroborating the expected effects for the formation of hydrogen-bonding complexes (Amendola et al., 2010). In the case of the pseudo-halides, the more basic CN− anion was complexed with higher selectivity with respect to SCN− (Kass CN−/Kass SCN− = 8.9 and 9.8 for 5b and 5c, respectively). With regard to the planar oxoanions, receptors 5b and especially 5c show a very efficient binding toward the carboxylates BzO− and AcO− (log Kass = 3.83 and 3.67, respectively, for 5c). As observed before with 5a and with other dihomooxa ureas (Marcos et al., 2014b; Teixeira et al., 2017), there is a slight inversion of the basicity order. π staking interactions may contribute to this slight increase of the BzO− complexation over that of AcO−. The inorganic oxoanions, HS and H2P, are also tightly bound by these receptors.

UV-Vis Absorption and Fluorescence Studies

The binding properties of CF3- and NO2-Phureas (5b and 5c) were complemented through UV-Vis absorption titrations. Thus, the interactions between these receptors and some selected anions of different geometries (F−, Cl−, Br−, N, AcO−, BzO−, HS, and H2P) as TBA salts were studied in chloroform (or dichloromethane) and acetonitrile solvents.

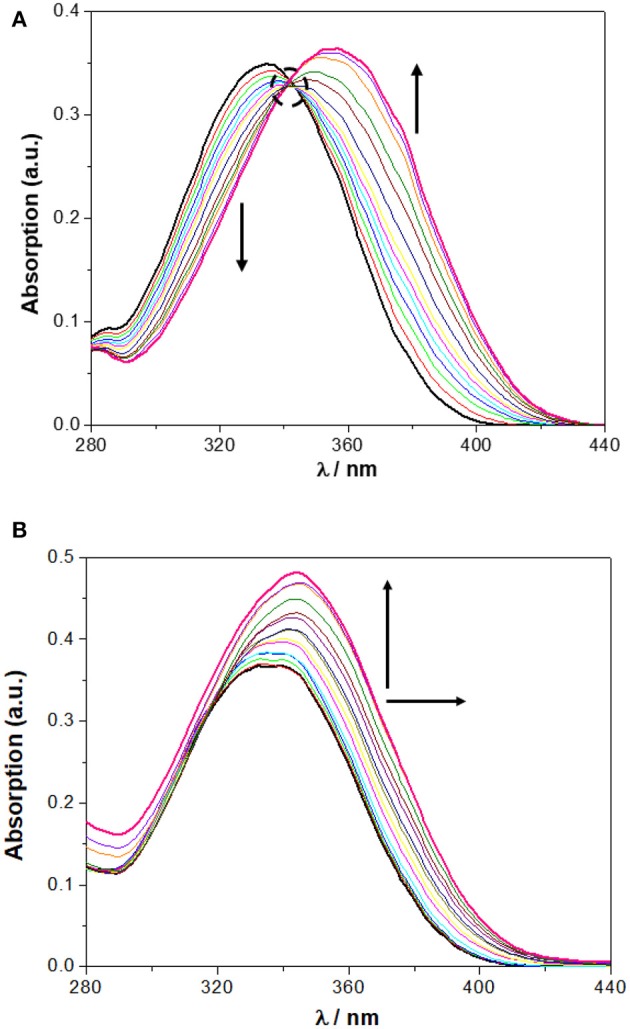

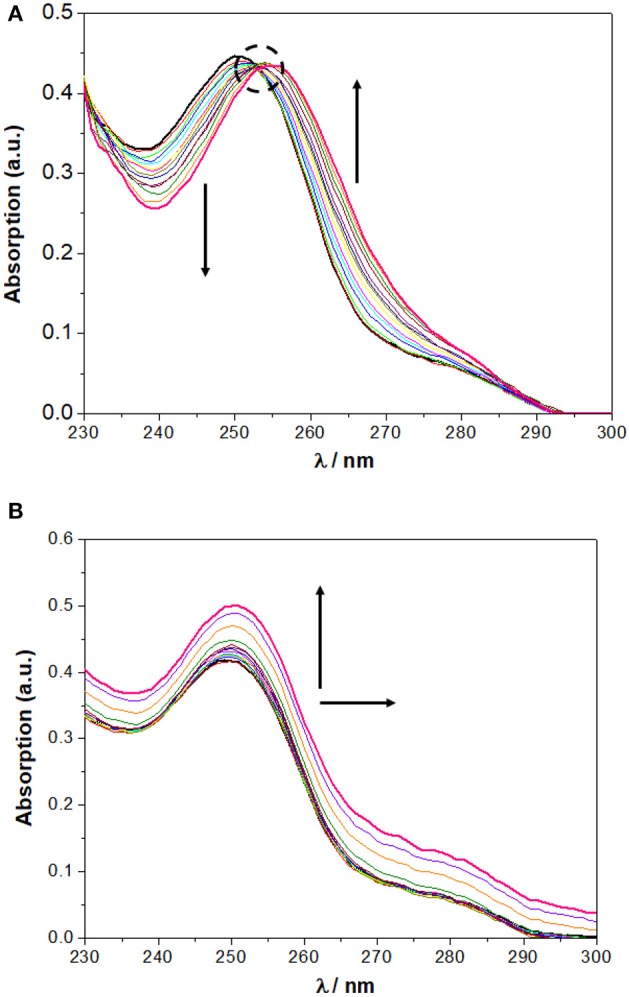

In chloroform, NO2-Phurea 5c displays an absorption band centered at approximately 335 nm. Upon addition of increasing amounts of F− ion, this band decreases in intensity while a new one is progressively formed, reaching a maximum at 356 nm (red shift of 21 nm) and exhibiting an isosbestic point at 341 nm, which reveals the existence of only two species (Figure 6A). Similar absorption spectral changes were observed for the carboxylates AcO− and BzO−, both leading to red shifts of 15 nm and presenting isosbestic points, as well as for the inorganic oxoanions HS and H2P, although to a smaller extent. In the case of addition of the spherical Cl− and Br− anions, and the planar N, successive increases of the absorption were recorded, but with almost no shifts in their maxima. Similar absorption spectra were obtain for NO2-Phureido-calix[4]arene analogs (Babu et al., 2009; Curinova et al., 2009). CF3-Phurea 5b exhibits a similar behavior in dichloromethane. In this case it was not possible to use chloroform solvent due to absorption overlapping with urea 5b. The addition of increasing amounts of F−, AcO−, BzO−, and H2P anions to a solution of 5b leads to a decrease of the intensity of its absorption peak at 250 nm, while a new band appears and progressively moves to longer wavelength. Isosbestic points can also be observed, as illustrated in Figure 7A for the BzO− anion. The other anions studied showed no new band formation at higher wavelengths; only a gradual increase of the absorption band centered at 250 nm was observed as the anion concentration increased. In acetonitrile, both receptors showed identical behaviors toward all the anions: a successive increase of the absorption in the presence of the anions, with no significant modification of their band shapes (Figures 6B, 7B).

Figure 6.

Changes in the UV spectra of NO2-Phurea 5c (1.0 × 10−5 M) upon addition of TBA F (up to 10 equiv) in: (A) CHCl3 and (B) MeCN. The dotted circle indicates the isosbestic point. The arrows indicate the decreasing or increasing amounts of salt and maximum displacement.

Figure 7.

Changes in the UV spectra of CF3-Phurea 5b (5.0 × 10 −6 M) upon addition of TBA BzO (up to 10 equiv) in: (A) CH2Cl2 and (B) MeCN. The dotted circle indicates the isosbestic point. The arrows indicate the decreasing or increasing amounts of salt and maximum displacement.

In all cases, the spectral variations were sufficiently important to allow the determination of the corresponding binding constants. The data presented in Table 3 show a stronger complexation in chloroform (or dichloromethane in the case of 5b) than in acetonitrile for both ureas, in agreement with the competitiveness of the solvents. The association constants in both solvents are higher than those obtained by NMR, but follow the same trend: F−, AcO−, and BzO− are the best bound anions. The UV concentrations are more than 200 times less than those used in the NMR titrations, and this fact influences the association constants. The more diluted solutions used in the UV experiments favor the dissociation of the salts, thereby providing a higher concentration of the anions available for binding and resulting in higher association constants.

Table 3.

Association constants (log Kass)a of dihomooxa ureas 5b and 5c determined by UV-Vis absorption at 25°C.

| Spherical | Trigonal planar | Tetrahedral | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent | F− | Cl− | Br− | N | AcO− | BzO− | HS | H2P | |

| CF3-Phurea 5b | CH2Cl2 | 4.57 | 4.02 | 3.66 | 3.72 | 4.54 | 4.65 | 3.93 | 3.93 |

| MeCN | 4.10 | 3.81 | 3.54 | 3.50 | 4.03 | 4.20 | 3.81 | 3.60 | |

| NO2-Phurea 5c | CHCl3 | 4.74 | 4.30 | 3.90 | 3.97 | 4.65 | 4.72 | 4.19 | 4.24 |

| MeCN | 4.52 | 4.04 | 3.61 | 3.63 | 4.13 | 4.30 | 3.77 | 3.83 | |

Estimated error <10%.

The N and HS anion binding constants with CF3-Phurea 5b were also determined by fluorescence in CH2Cl2. The data obtained (log Kass: N = 3.87 and HS = 4.00) are higher, as expected, than those obtained for 5a (log Kass = 3.5 and 3.7) (Miranda et al., 2017), but follow the same trend. The results are also similar to those obtained by UV-Vis absorption (Table 3), indicating that fluorescence can also be a good method for the determination of the receptor-anion association constants.

Organic Ion Pair Recognition

Based on our earlier good results obtained with Phurea 5a (Gattuso et al., 2015), dihomooxa receptors 5b and 5c have also been tested as heteroditopic receptors for n-propyl and n-butylammonium chlorides in a preliminary study to evaluate their complexation behavior. Besides the presence of a hydrophobic cavity and an anionic binding site in close proximity, CF3- and NO2-Phureas displayed an enhancement of their binding efficiency for Cl− anion compared to that of 5a (almost one log unity in the case of 5c), being expected a higher positive effect on the salt complexation.

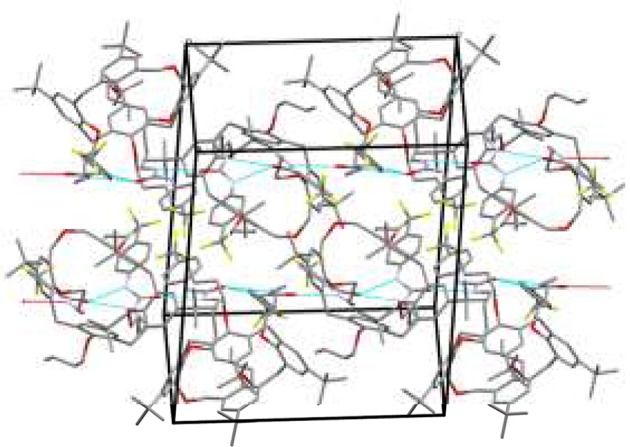

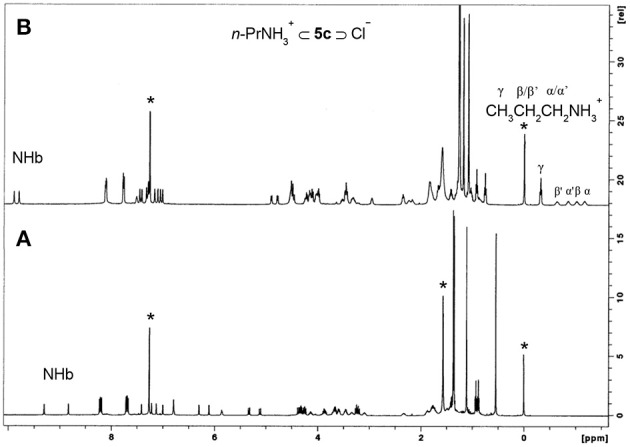

Proton NMR titrations were performed in CDCl3 by adding increasing amounts (up to two equiv) of the salts to solutions of the receptors 5b and 5c. Three sets of resonances corresponding to the free and complexed receptors, and to the guest bound to the host were observed on addition of the first aliquot of the salts. The alkylammonium cation inclusion inside the dihomooxa cavity is demonstrated by the appearance of the alkyl group resonances in the negative region of the spectrum. On the other side, simultaneous chloride binding to the urea moiety is shown by the downfield shifts observed for all the NH protons, indicating complexation of the anion through hydrogen-bond interactions (Figure 8). This Figure also shows the pairs of enantiotopic hydrogen atoms of the α- and β-CH2 groups of the included guest displaying non-equivalent signals owing to the chiral environment of the host. The free host signals disappeared with subsequent additions of the salts. This binding process occurs under slow exchange condition on the NMR time scale. All these host-guest pairs studied displayed percentages of complexation higher than 95%, corresponding to association constants higher than 109 M−2.

Figure 8.

1H NMR spectra (500 MHz, CDCl3, 25°C) of: (A) NO2-Phurea 5c, (B) 5c + 1 eq of n-PrNH2·HCl. *Denotes residual solvent signals.

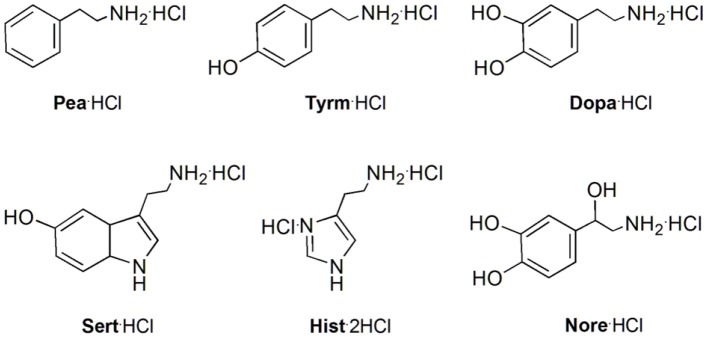

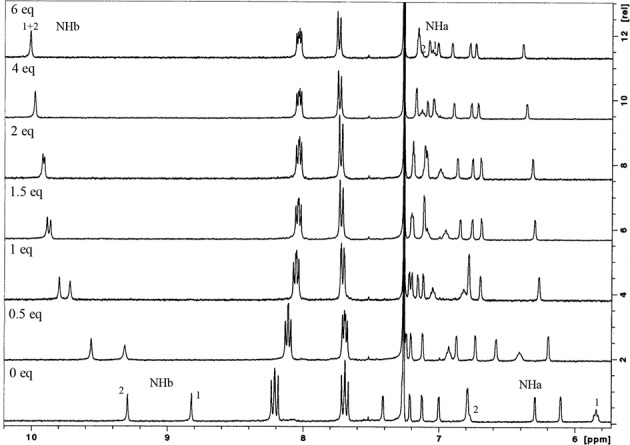

These ureas were then tested in the recognition of the monoamine neurotransmitter and trace amine hydrochlorides shown in Figure 9. The studies were done in a CDCl3/CD3OD solvent mixture (5:1, v/v) for a better solubility of the guests. The addition of one equiv. of the guests to a solution of the hosts at room temperature (Figure 10A) induced a large broadening of all signals, indicating a strong host-guest interaction (Figure 10B). To obtain a clear interpretation of the spectra, it was however necessary to lower the temperature to 233 K. As illustrated in Figure 10C for 5b with dopamine·HCl, four high field signals for the α- and β-CH2 protons of the guest were observed, showing their inclusion inside the asymmetric cavity of the host. The slow exchange rate between the free and the complexed receptors allowed the determination of the percentages of complexation and of the corresponding association constants, by direct integration of the peaks. The data (Table 4) show that both ureas display an outstanding efficiency toward the biogenic amines, being as expected better than Phurea 5a. Both ureas present very high percentages of complexation and association constants, even preventing us from calculating Kass for phenylethylamine and also tyramine in the case of NO2-Phurea 5c. This urea is more efficient than CF3-Phurea 5b, but the latter is slightly more selective. Ureas 5b and 5c display a similar affinity trend, comparable with 5a, showing some selectivity for Pea and Tyrm and no interaction with histamine and norepinephrine. As mentioned before (Gattuso et al., 2015), it seems that the less bulky Pea and Tyrm guests fit better inside the dihomooxa cavity.

Figure 9.

Structures of the monoamine neurotransmitters and trace amine hydrochlorides studied: 2-phenylethylamine (Pea·HCl), tyramine (Tyrm·HCl), dopamine (Dopa·HCl), serotonin (Sert·HCl), histamine (Hist·2HCl), and norepinephrine (Nore·HCl).

Figure 10.

1H NMR spectra (500 MHz, CDCl3/CD3OD, 5:1, v/v) of: (A) [CF3-Phurea 5b] = 1.0 mM at 298 K, (B) [5b] = [Dopa·HCl] = 1.0 mM at 298 K, and (C) [5b] = [Dopa·HCl] = 1.0 mM at 233 K. *Residual solvent signals.

Table 4.

Percentages of complex formation and corresponding association constants, Kass (M−2)a.

| Pea·HCl | Tyrm·HCl | Dopa·HCl | Sert·HCl | Hist·2HCl | Nore·HCl | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phurea 5ab | 86% 41,000 | 85% 36,000 | 67% 6,300 | 61% 4,100 | c | c |

| CF3-Phurea 5b | >95% >109 | 91% 1,23,000 | 79% 18,000 | 81% 22,000 | c | c |

| NO2-Phurea 5c | >95% >109 | >95% >109 | 87% 51,000 | 86% 42,000 | c | c |

CDCl3/CD3OD (5:1, v/v), 233 K; Estimated error ≤15%.

Data taken from Gattuso et al. (2015).

c No complexation observed.

Conclusions

Two new 1,3-disubstituted dihomooxacalix[4]arene receptors containing para CF3- (5b) or NO2-phenylurea (5c) moieties on the lower rim linked by a butyl spacer were obtained in the cone conformation in solution. The X-ray structure of 5b was obtained and confirms the cone conformation with one tert-butyl-phenyl group oriented toward the center of the cup. The 1,3-substitution pattern on the lower rim results in inherently chiral molecules, present as racemic mixture in the centrosymmetric crystals. In the crystal structure, the ureido groups are involved in asymmetric intra- and inter-molecular bifurcated H-bonds.

The anion binding affinity of 5b and 5c was established by 1H NMR, UV-Vis and fluorescence studies. These receptors form 1:1 complexes with anions of different geometries through hydrogen bonding. Comparing to the unsubstituted phenylurea 5a, CF3-Phurea and especially NO2-Phurea showed, as expected, a relevant enhancement on their binding efficiency, due to the increased acidity of their urea NH protons. Compound 5c displayed the strongest complexation for F− (log Kass = 3.88), closely followed by the oxoanions BzO−, AcO−, and HS. The association constants obtained by UV-Vis absorption titrations followed the same trend of those obtained by NMR, and were higher in CHCl3 (or CH2Cl2) than in MeCN, according to the competitiveness of the solvents.

As heteroditopic receptors, both compounds exhibited remarkable ion pair recognition, displaying very high association constants for the monoamine neurotransmitters tyramine, dopamine and serotonin, and the trace amine phenylethylamine hydrochlorides. The more efficient ditopic receptor 5c presented Kass higher than 109 M−2 in the case of Pea and Tyrm, which turns it into a potential candidate for biogenic amine chemosensors in biological fluids.

Experiment

Synthesis

All chemicals were reagent grade and were used without further purification. Chromatographic separations were performed on Merck silica gel 60 (particle size 40–63 μm, 230–400 mesh). Melting points were measured on a Stuart Scientific apparatus and are uncorrected. FTIR spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu Model IRaffinity-1 spectrophotometer. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz spectrometer, with TMS as internal reference. The conventional COSY experiment was collected as 256×2 K complex points. Elemental analysis was determined on a Fisons EA 1108 microanalyser.

Procedure for the Synthesis of Ureas 5b and 5c

To a solution of 4 (0.71 g, 0.762 mmol) in CHCl3 (35 mL) was added 1.53 mmol of the appropriate isocyanate. The mixture was stirred at room temperature under N2 for 4 h. Evaporation of the solvent yielded the crude products which were purified as described below.

7,13,19,25-Tetra-Tert-Butyl-27,29-Bis[[N′-(p-Trifluoromethylphenylureido)butyl]oxy]-28,30-dibutoxy-2,3-dihomo-3-oxacalix[4]arene (5b)

Flash chromatography (SiO2, eluent CH2Cl2/MeOH, 99.7:0.3): it was obtained in 51% yield (0.51 g); mp 151–152°C; IR (KBr) 3,350 cm−1 (NH), 1,647 cm−1 (CO); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 0.55, 1.10, 1.34, 1.37 [4s, 36H, C(CH3)], 0.89, 0.93 (2t, 6H, J = 7.4 Hz, CH3), 1.33–1.54 (m, 8H, OCH2CH2CH2CH3 and OCH2CH2CH2CH2NHa), 1.77, 1.89, 2.31 (3m, 8H, OCH2CH2CH2CH3 and OCH2CH2CH2CH2NHa), 3.16, 3.37, 3.59 (3m, 4H, OCH2CH2CH2CH2NHa), 3.20, 4.28 (ABq, 2H, J = 12.6 Hz, ArCH2Ar), 3.22, 4.26 (ABq, 2H, J = 14.1 Hz, ArCH2Ar), 3.24, 4.38 (ABq, 2H, J = 12.5 Hz, ArCH2Ar), 3.45, 3.71, 3.90, 4.07 (4m, 4H, OCH2CH2CH2CH2NHa), 3.59, 3.66, 3.82 (3m, 4H, OCH2CH2CH2CH3), 4.32, 5.26 (ABq, 2H, J = 12.4 Hz, CH2OCH2), 4.33, 5.04 (ABq, 2H, J = 12.7 Hz, CH2OCH2), 5.87, 6.57 (2t, 2H, NHa), 6.11, 6.35, 6.78, 6.98, 7.12, 7.20, 7.27, 7.37 (8d, 8H, ArH), 7.50, 7.53 (2d, 4H, Ph-Ho), 7.60, 7.61 (2d, 4H, Ph-Hm), 8.45, 8.79 (2s, 2H, NHb); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125.8 MHz) δ 13.9, 14.1 [O(CH2)3CH3], 19.3, 19.4 (OCH2CH2CH2CH3), 25.0, 25.5, 25.8, 28.8 (OCH2CH2CH2CH2NHa), 28.9. 31.0, 31.3 (ArCH2Ar), 31.2, 31.4, 31.6, 31.7 [C(CH3)], 32.2, 32.6 (OCH2CH2CH2CH3), 33.6, 33.9, 34.21, 34.22 [C(CH3)], 39.3, 39.4 (OCH2CH2CH2CH2NHa), 71.7, 71.9 (CH2OCH2), 73.2, 74.8, 75.0, 75.6 (OCH2CH2CH2CH2NHa and OCH2CH2CH2CH3), 117.7, 1,178, 123.7, 125.4, 125.6, 126.0, 126.1, 126.3, 126.49, 126.52, 126.9, 129.5 (ArH), 123.3, 124.1 (q, J = 32 Hz, CF3), 128.6, 130.2, 131.8, 132.7, 133.1, 134.3, 134.6, 136.2, 143.1, 143.4, 144.4, 145.0, 145.1, 145.7, 152.7, 153.1, 153.9, 155.3 (Ar), 155.6, 156.7 (CO). Anal. Calcd for C77H100N4O7F6: C, 70.73; H, 7.71; N, 4.28. Found: C, 70.78; H, 8.01; N, 4.02.

7,13,19,25-Tetra-Tert-Butyl-27,29-Bis[[N′-(p-Nitrophenylureido)Butyl]oxy]-28,30-dibutoxy-2,3-dihomo-3-oxacalix[4]arene (5c)

Flash chromatography (SiO2, eluent CH2Cl2/MeOH, 99.7:0.3) followed by recrystallization from CH2Cl2/n-hexane: it was obtained in 40% yield (0.38 g); mp 157–159°C; IR (KBr) 3,367 cm−1 (NH), 1,647 cm−1 (CO); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 0.54, 1.11, 1.35, 1.37 [4s, 36H, C(CH3)], 0.88, 0.93 (2t, 6H, J = 7.4 Hz, CH3), 1.38–1.50 (m, 4H, OCH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.48, 1.76, 1.87, 2.34 (4m, 12H, OCH2CH2CH2CH2NHa and OCH2CH2CH2CH3), 3.09, 3.34, 3.45, 3.59 (4m, 4H, OCH2CH2CH2CH2NHa), 3.20, 4.26 (ABq, 2H, J = 12.7 Hz, ArCH2Ar), 3.23, 4.24 (ABq, 2H, J = 14.0 Hz, ArCH2Ar), 3.26, 4.37 (ABq, 2H, J = 12.6 Hz, ArCH2Ar), 3.45, 3.59, 3.66, 4.14 (4m, 4H, OCH2CH2CH2CH2NHa), 3.66, 3.87 (2m, 4H, OCH2CH2CH2CH3), 4.31, 5.33 (ABq, 2H, J = 12.3 Hz, CH2OCH2), 4.33, 5.12 (ABq, 2H, J = 12.3 Hz, CH2OCH2), 5.85, 6.79 (2t, 2H, NHa), 6.10, 6.29, 6.79, 7.00, 7.12, 7.21, 7.26, 7.41 (8d, 8H, ArH), 7.68, 7.71 (2d, 4H, Ph-Ho), 8.20, 8.23 (2d, 4H, Ph-Hm), 8.83, 9.31 (2s, 2H, NHb); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125.8 MHz) δ 13.9, 14.1 [O(CH2)3CH3], 19.3, 19.4 (OCH2CH2CH2CH3), 24.8, 25.2, 25.7, 28.81 (OCH2CH2CH2CH2NHa), 28.84, 31.1, 31.4 (ArCH2Ar), 31.2, 31.4, 31.5, 31.7 [C(CH3)], 32.2, 32.6 (OCH2CH2CH2CH3), 33.6, 34.0, 34.24, 34.23 [C(CH3)], 39.3 (2C) (OCH2CH2CH2CH2NHa), 71.7, 72.1 (CH2OCH2), 73.9, 74.9, 75.1, 75.6 (OCH2CH2CH2CH2NHa and OCH2CH2CH2CH3), 117.0, 117.1, 123.6, 125.3, 125.56, 125.60, 125.63, 126.0, 126.1, 126.6, 126.9, 130.0 (ArH), 128.3, 129.7, 131.6, 132.7, 133.1, 134.3, 134.6, 136.2, 141.6, 142.1, 144.4, 145.1, 145.2, 145.8, 146.1, 146.7, 152.7, 153.2, 153.8, 154.9 (Ar), 155.7, 156.3 (CO). Anal. Calcd for C75H100N6O11: C, 71.40; H, 7.99; N, 6.66. Found: C, 70.99; H, 7.99; N, 6.48.

Determination of the Crystallographic Structure of Compound 5b

Small colorless single crystal needles were obtained by slow evaporation of a chloroform solution containing compound 5b. The single crystals investigated were very small (0.01, 0.01, 0.05 mm) and synchrotron radiation was necessary to obtain a dataset suitable to solve the structure. The data was also collected with frozen crystal at 100 K. Despite these provisions, the best small crystal showed poor diffraction data with a maximum resolution of 0.98 Å. Data collection was carried out at the Macromolecular crystallography XRD1 beamline of the Elettra synchrotron (Trieste, Italy), employing the rotating-crystal method with a Dectris Pilatus 2M area detector. Single crystals were dipped in PEG200 cryoprotectant, mounted on a loop and flash-frozen under a liquid nitrogen stream at a 100 K. Diffraction data were indexed and integrated using the XDS package (Kabsch, 2010a), while scaling was carried out with XSCALE (Kabsch, 2010b). The structure was solved using the SHELXT program (Sheldrick, 2015) and structure refinement was performed with SHELXL-14 (Sheldrick, 2008), operating through the WinGX GUI (Farrugia, 2012) by full-matrix least-squares (FMLS) methods on F2.

The structure was solved using the SHELXT program (Sheldrick, 2015). The asymmetric unit of the monoclinic crystal (space group P21/c) is composed of one molecule of 5b and disordered co-crystallized chloroform solvent molecule with a total occupancy factor of 0.7. The chloroform molecule shows disorder over two positions, which were isotropically refined at 0.4/0.3 partial occupancies. All other non-hydrogen atoms were anisotropically refined at full occupancy. Hydrogen atoms were added at the calculated positions and refined using the riding model. Crystallographic data and refinement details are reported in Table S1.

1H NMR Titrations

The anion association constants (as log Kass) were determined in CDCl3 by 1H NMR titration experiments. Several aliquots (up to 10 equiv) of the anion solutions (as tetrabutylammonium salts) were added to 0.5 mL solution of the receptors (2.5 × 10−3 – 5 × 10−3 M) directly in the NMR tube. The spectra were recorded after each addition of the salts, and the temperature of the NMR probe was kept constant at 25°C. For each anion-receptor system titrations were repeated at least two times. The association constants were evaluated using the WinEQNMR2 program (Hynes, 1993) by following the urea NH chemical shifts. When possible, Kass was calculated as a mean value of the four NH chemical shifts. The Job plots were performed keeping the total concentration in the same range as before. Concerning ion-pair recognition experiments, the percentage of complex formation, necessary for the calculation of the corresponding Kass, was determined by direct 1H NMR integration of the free and complexed resonances of the hosts and/or the guests, present at equilibrium. The samples were prepared by mixing aliquots of stock solutions of the host (600 μl) and guests (60 μl) to obtain a final equimolar host-guest solution of 1.0 × 10−3 M. Details related to these experiments have already been described (Gattuso et al., 2015).

UV-Vis Absorption and Fluorescence Studies

Absorption and fluorescence studies were done using an UV-3101PC UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer and a Fluorolog F112A fluorimeter in right-angle configuration, respectively. The association constants were determined in CHCl3 (or CH2Cl2) and MeCN by UV-Vis absorption spectrophotometry at 25°C. A few anion complexation studies were also done by steady-state fluorescence in CH2Cl2. The spectra were recorded between 230 and 300 nm or 280–440 nm, in the case of NO2-Phurea 5c, and using quartz cells with an optical path length of 1 cm. Several aliquots (up to 10 equiv) of the anion solutions (as TBA salts) were added to a 2 mL solution of the receptors (5.0 × 10−6 – 5.0 × 10−5 M) directly in the cell. The spectral changes were interpreted using the HypSpec 2014 program (Gans et al., 1996). Details concerning the photophysical properties determination are given in the Supporting Information.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

AM synthesized and characterized the compounds, carried out the UV-Vis absorption, and fluorescence studies. DS contributed to the synthesis, characterization, and UV-Vis titrations of one of the compounds. PM designed the study, performed the NMR experiments, their analysis and interpretation, and wrote the manuscript. JA carried out some NMR experiments, their analysis and interpretation, contributed also to the writing, and critical review of the manuscript. MB-S performed the analysis, interpretation, and writing of the photophysics results. NH did the crystallization and structure determination by X-ray diffraction, the analysis, interpretation, and manuscript preparation for structural data. SG performed the analysis, interpretation, and manuscript preparation for structural data.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, Project ref. UID/QUI/00100/2013; AM thanks a Ph.D. Grant ref. SFRH/BD/129323/2017. DS thanks to UPMC (Paris) for an internship grant.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2019.00758/full#supplementary-material

References

- Amendola V., Esteban-Gómez D., Fabbrizzi L., Licchelli M. (2006). What anions do to N-H containing receptors. Acc. Chem. Res. 39, 343–353. 10.1021/ar050195l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amendola V., Fabbrizzi L., Mosca L. (2010). Anion recognition by hydrogen bonding: urea-based receptors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 3889–3915. 10.1039/b822552b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augusto A. S., Miranda A. S., Ascenso J. R., Miranda M. Q., Félix V., Brancatelli G., et al. (2018). Anion recognition by partial cone dihomooxacalix[4]arene based receptors bearing urea groups: remarkable affinity for benzoate ion. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 5657–5667. 10.1002/ejoc.201800880 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Babu J. N., Bhalla V., Kumar M., Puri R. K., Mahajan R. K. (2009). Chloride ion recognition using thiourea/urea based receptors incorporated into 1,3-disubstituted calix[4]arenes. New J. Chem. 33, 675–681. 10.1039/b816275a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Busschaert N., Caltagirone C., Van Rossom W., Gale P. A. (2015). Applications of supramolecular anion recognition. Chem. Rev. 115, 8038–8155. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capici C., De Zorzi R., Gargiulli C., Gattuso G., Geremia S., Notti A., et al. (2010). Calix[5]crown-3-based heteroditopic receptors for n-butylammonium halides. Tetrahedron 66, 4987–4993. 10.1016/j.tet.2010.05.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cornut D., Moerkerke S., Wouters J., Bruylants G., Jabin I. (2015). A biomimetic heteroditopic receptor for zwitterions in protic media. Chem. Asian J. 10, 440–446. 10.1002/asia.201403082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curinova P., Stibor I., Budka J., Sykora J., Kamil L., Lhotak P. (2009). Anion recognition by diureido-calix[4]arenes in the 1,3-alternate conformation. New J. Chem. 33, 612–619. 10.1039/b816790g [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Solis S., Elisei F., Gunnlaugsson T. (2015). Lower rim amide (1,3) functionalized calix[4]arene amido-thiourea derivatives as dimetallic Zn(II) coordination complexes for anion recognition/sensing. Supramol. Chem. 27, 697–705. 10.1080/10610278.2015.1079633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans N. H., Beer P. D. (2014). Advances in anion supramolecular chemistry: from recognition to chemical applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 11716–11754. 10.1002/anie.201309937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia L. J. (2012). WinGX and ORTEP for windows: an update. J. Appl. Cryst. 45, 849–854. 10.1107/S0021889812029111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gale P. A., Howe E. N. W., Wu X. (2016). Anion receptor chemistry. Chem 1, 351–422. [Google Scholar]

- Gans P., Sabatini A., Vacca A. (1996). Investigation of equilibria in solution. Determination of equilibrium constants with the HYPERQUAD suite of programs. Talanta 43, 1739–1753. 10.1016/0039-9140(96)01958-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattuso G., Notti A., Parisi M. F., Pisagatti I., Marcos P. M., Ascenso J. R., et al. (2015). Selective recognition of biogenic amine hydrochlorides by heteroditopic dihomooxacalix[4]arenes. New J. Chem. 39, 817–821. 10.1039/c4nj01423e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutsche C. D. (2008). Calixarenes (Monographs in Supramolecular Chemistry). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- Hamon M., Ménand M., Le Gac S., Luhmer M., Dalla V., Jabin I. (2008). Calix[6]tris(thio)ureas: heteroditopic receptors for the cooperative binding of organic ion pairs. J. Org. Chem. 73, 7067–7071. 10.1021/jo800712q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes M. J. (1993). EQNMR: a computer program for the calculation of stability constants from nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shift data. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 311–312. 10.1039/DT9930000311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaime C., de Mendoza J., Prados P., Nieto P., Sanchez C. (1991). Carbon-13 NMR chemical shifts. A single rule to determine the conformation of calix[4]arenes. J. Org. Chem. 56, 3372–3376. 10.1021/jo00010a036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. (2010a). XDS. Acta Cryst. D 66, 125–132. 10.1107/S0907444909047337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. (2010b). Integration, scaling, space-group assignment and post-refinement. Acta Cryst. D 66, 133–144. 10.1107/S0907444909047374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. K., Sessler J. L. (2010). Ion pair receptors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 3784–3809. 10.1039/c002694h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klejch T., Slavicek J., Hudecek O., Eigner V., Gutierrez N. A., Curinova P., et al. (2016). Calix[4]arenes containing a ureido functionality on the lower rim as highly efficient receptors for anion recognition. New J. Chem. 40, 7935–7942. 10.1039/c6nj01271j [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lascaux A., le Gac S., Wouters J., Luhmer M., Jabin I. (2010). An allosteric heteroditopic receptor for neutral guests and contact ion pairs with a remarkable selectivity for ammonium fluoride salts. Org. Biomol. Chem. 8, 4607–4616. 10.1039/c0ob00211a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos P. M. (2016). Functionalization and properties of homooxacalixarenes, in Calixarenes and Beyond, eds Neri P., Sesseler J. L., Wang M. X. (Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; ), 445–466. 10.1007/978-3-319-31867-7_17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos P. M., Teixeira F. A., Segurado M. A. P., Ascenso J. R., Bernardino R. J., Brancatelli G., et al. (2014b). Synthesis and anion binding properties of new dihomooxacalix[4]arene diurea and dithiourea receptors. Tetrahedron 70, 6497–6505. 10.1016/j.tet.2014.07.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos P. M., Teixeira F. A., Segurado M. A. P., Ascenso J. R., Bernardino R. J., Michel S., et al. (2014a). Bidentate urea derivatives of p-tert-butyldihomooxacalix[4]arene: neutral receptors for anion complexation. J. Org. Chem. 79, 742–751. 10.1021/jo4026012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus Y. (1997). Ion Properties. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker, 50–51. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell A. J., Beer P. D. (2012). Heteroditopic receptors for ion-pair recognition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 5052–5061. 10.1002/anie.201107244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda A. S., Martelo L. M., Fedorov A. A., Berberan-Santos M. N., Marcos P. M. (2017). Fluorescence properties of p-tert-butyldihomooxacalix[4]arene derivatives and the effect of anion complexation. New J. Chem. 41, 5967–5973. 10.1039/c7nj00652g [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moerkerke S., Malytskyi V., Marcélis L., Wouters J., Jabin I. (2017). Selective recognition of quaternary ammonium ions and zwitterions by using a biomimetic bis-calix[6]arene-based receptor. Org. Biomol. Chem. 15, 8967–8974. 10.1039/c7ob02031g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutihac L., Lee J. H., Kim J. S., Vicens J. (2011). Recognition of amino acids by functionalized calixarenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 2777–2796. 10.1039/c0cs00005a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehra A., Bandaru S., Yarramala D. S., Rao C. P. (2016). Differential recognition of anions with selectivity towards F– by a calix[6]arene-thiourea conjugate investigated by spectroscopy, microscopy, and computational modeling by DFT. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 8903–8914. 10.1002/chem.201600844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescatori L., Arduini A., Pochini A., Secchi A., Massera C., Ugozzoli F. (2009). Monotopic and heteroditopic calix[4]arene receptors as hosts for pyridinium and viologen ion pairs: a solution and solid-state study. Org. Biomol. Chem. 7, 3698–3708. 10.1039/b906409e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan E., Matthews S. E., Gunnlaugsson T. (2007). Colorimetric recognition of anions using preorganized tetra-amidourea derived calix[4]arene sensors. J. Org. Chem. 72, 7497–7503. 10.1021/jo070439a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezankova M., Budka J., Miksatko J., Eigner V., Cisarova I., Curinova P., et al. (2017). Anion receptors based on intramolecularly bridged calix[4]arenes bearing ureido functions. Tetrahedron 73, 742–749. 10.1016/j.tet.2016.12.054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. (2008). A short history of SHELX. Acta Cryst. A 64, 112–122. 10.1107/S0108767307043930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. (2015). SHELXT - Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Cryst. A 71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053273314026370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira F. A., Marcos P. M., Ascenso J. R., Brancatelli G., Hickey N., Geremia S. (2017). Selective binding of spherical and linear anions by tetraphenyl(thio)urea-based dihomooxacalix[4]arene receptors. J. Org. Chem. 82, 11383–11390. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b01801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.