Abstract

Background and Objectives

To determine how the wellbeing of carers of people with dementia is understood and measured in contemporary health research.

Research Design and Methods

A systematic review of reviews was designed, registered with PROSPERO, and then conducted. This focused on systematic reviews of research literature published from 2010 onwards; with the wellbeing of carers of people with dementia being a primary focus. N = 19 studies met the inclusion criteria. Quality appraisal was conducted using the AMSTAR tool (2015). A narrative synthesis was conducted to explore how wellbeing is currently being understood and measured.

Results

Contemporary health research most frequently conceptualizes wellbeing in the context of a loss–deficit model. Current healthcare research has not kept pace with wider discussions surrounding wellbeing which have become both more complex and more sophisticated. Relying on the loss–deficit model limits current research in understanding and measuring the lived experience of carers of people with dementia. There remains need for a clear and consistent measurement of wellbeing.

Discussion and Implications

Without clear consensus, health professionals must be careful when using the term “wellbeing”. To help inform healthcare policy and practice, we offer a starting point for a richer concept of wellbeing in the context of dementia that is multi-faceted to include positive dimensions of caregiving in addition to recognized aspects of burden. Standardized and robust measurements are needed to enhance research and there may be benefit from developing a more mixed, blended approach to measurement.

Keywords: Enriching caring, Social gerontology, Wellbeing

Background and Objectives

Wellbeing is a central concept in research exploring the experiences of carers of people with dementia. Creating the conditions in which people can thrive in later life holds a prominent position in social gerontology research (Martinson & Berridge, 2015). For people affected by dementia, creating these conditions requires further investment in the wellbeing of carers. More than 47 million people are living with dementia worldwide. The informal unpaid input of carers is considerable with family care frequently the cornerstone of support for people with dementia (Alzheimer Disease International, 2016). This care can be challenging given the progressive nature of dementia and the behavioral and psychological symptoms associated with a condition that changes over time; although solely associating caring with stress and burden is over-simplistic as it denies the positive aspects of caring in the context of family relationships (Tremont, 2011). Given the importance of family caring in the provision of support for people with dementia, national dementia plans have emphasized the need to support family carers as well as people with dementia (Robertson et al., 2016).

The concept of wellbeing has been applied and researched intensively, particularly in the context of intervention development to reduce burden and improve quality of life (Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2012). It is natural to assume, therefore, that there is a common, agreed, understanding of wellbeing. Unfortunately, despite its prevalence, wellbeing has proven a difficult concept to capture or define, not least because of its interchangeable use with “quality of life” which is arguably one dimension of wellbeing rather than an alternative term for the concept (Dodge, Daly, Huyton, & Saunders, 2012). Due to the conceptual association with “burden”, carer wellbeing is most frequently situated in the context of mental health, and depression in particular (Thompson et al., 2007) despite recognition that wellbeing is more than the absence of “illness” (Herzlich, 1973). Consequently, wellbeing is framed primarily from a perspective that emphasizes ill health, as opposed to encompassing both positive and negative dimensions.

Interestingly, discussion within a wider policy and legislative context has become much more complex and sophisticated, identifying a range of psychological, physical, and social outcomes that influence the health and wellbeing of the carer and highlighting seven key domains of wellbeing (Brown, Abdallah, & Townsley, 2017). This demonstrates that wellbeing is a multi-faceted and multi-layered concept that should account for multiple components (Lindert, Bain, Kubzansky, & Stein, 2015). Cross-disciplinary approaches are currently making progress in understanding the concept of wellbeing. The University of Cambridge (2017) aims to study wellbeing across disciplines to identify appropriate measures across sectors and circumstances. Contemporary debates in philosophy, for example, continue to explore the possibility of an overarching “theory of wellbeing” (Fletcher, 2016); whether that be based on hedonism, satisfaction of desires, or other, objective, factors. Focusing specifically on dementia caregivers, a range of studies have investigated the effect caring for someone can have on an individual’s wellbeing (Chappel, Dujela, & Smith, 2015; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2004). With an emphasis on loss and deficit, this impact has been conceptualized as “caregiver burden”, a construct encompassing both subjective and objective components and having multiple repercussions (Carretero, Garcés, Ródenas, & Sanjosé, 2009; McCabe, You, & Tatangelo, 2016). Caregivers of people with dementia demonstrate higher levels of unmet needs, lower levels of service utilization and are more likely to suffer from a range of physical and mental health issues, leading to caregiver burnout and poorer outcomes for the care recipient (Etters, Goodall, & Harrison, 2008; McCabe et al., 2016). The difficulties of caregiver adaptation over time may also lead to early institutionalization, poor quality of life, depression, and early mortality for the care recipient (Gaugler, Kane, Kane, Clay, & Newcomer, 2005). For the purposes of this review, we adopt a widely accepted definition of caregiver burden proposed by (George & Gwyther, 1986) as “a perceived complex and multidimensional construct, which includes the physical, psychological or emotional, social and financial consequences that can be experienced by family members caring for dementia patients”.

Given the emphasis placed on caring and wellbeing in current healthcare legislation, policy, and practice—particularly in relation to the carers of people with dementia—it is important to clarify just what this concept means in contemporary research, whether it is being measured in an objective and meaningful way and whether there is a common understanding of the term in dementia care. The extent to which more sophisticated wider debate has filtered down into health research in this field remains to be seen. Indeed, are politicians, policy-makers, health-care professionals, family members, and researchers always talking about the same thing when they discuss the wellbeing of carers? These are significant and complex questions to assess, ones that this review aims to lay the groundwork for answering and in so doing contribute further to the development of an intellectually rich social gerontology (Cole, 1995, p. 343).

To further assist development in this field, and with a focus on the health sector, we conducted a systematic review of reviews to answer the following question: “how is wellbeing currently measured and understood in relation to the carers of people with dementia?” In addition to establishing the current picture, this timely review aims to look forward to inform future research, policy, and practice.

Research Design and Methods

The three core elements of this review (dementia, carers, and the concept of wellbeing) have been extensively researched in recent years, with a wealth of published material. Initial reading on the subject identified a number of existing systematic reviews explicitly analysing the wellbeing of carers of people with dementia (e.g. Leung, Orgeta, & Orrell, 2017; Tyack & Camic, 2017). A systematic review brings analytic and scientific rigor to the literature review process by “using systematic and explicit accountable methods” (Gough, Oliver, & Thomas, 2012, p. 12). Adopting pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, systematic reviews are reproducible, involve the systematic presentation and synthesis of study characteristics and findings, and minimize bias. Systematic reviews are therefore valuable in making sense of, and then condensing information from, large bodies of information. A systematic review of reviews has become increasingly popular where there is more than one review on an important topic. As a form of “umbrella review” (Loannidis, 2009), this brings together several systematic reviews and, as such, can provide a comprehensive summary of available evidence, its clinical and/or policy implications and highlight where more research is needed (Smith, Devane, Begley, & Clarke, 2011; Thomson, Russell, Becker, Klassen, & Hartling 2010).

PROSPERO (Prospero, n.d.) is an international prospective register of systematic reviews where there is a health related outcome (Booth et al., 2012). This database helps avoid duplication and reduces opportunity for reported bias by enabling comparison. No systematic review of reviews was identified in PROSPERO or in systematic review databases. The subsequent submitted review protocol (Supplementary Appendix 1) ensured topic, approach, and search strategy were clear in advance, and that findings could be linked back to the given protocol. Providing an a priori protocol is recognized as good practice by Prospero (n.d.) and AMSTAR (2015) guidelines.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Systematic reviews were included in the search strategy. Primary research studies, such as randomized controlled trials, or assessments of specific interventions, were necessarily excluded from this kind of review, as were other kinds of reviews not systematic in nature. The quality control and appraisal of this approach is discussed below. The focus is on reviews that examine the wellbeing of family and informal carers in detail, and as such reviews examining solely the experience of paid/professional carers were excluded, as are carers not providing support in a family or home setting. Consideration was given to a suitable inclusion and exclusion timeframe. A start date of 2010 was chosen to align with proposed wider conceptualizations of wellbeing as a multidimensional construct and tracking wellbeing over several domains (Lindert et al., 2015). Health and wellbeing is also central to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Health Policy Framework, “Health 2020” (WHO, n.d.) and action to improve the health and wellbeing of populations and reduce health inequalities. Dementia, and the support needs of carers, has been prioritized. Reviewing how wellbeing is measured and understood will enable the identification of appropriate measurement tools by researchers, policy-makers and politicians (Lindert et al., 2015). Reviews written in English, or with English translations, are included in the search strategy, although limitations of understanding from the research team means that reviews not in English are excluded. The explicit statement of the inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in Supplementary Appendix 2.

Search and Selection Strategy

Two databases specifically developed for systematic reviews provided the starting point for the search: the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (Cochrane Library, 2017) and the Database of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2017). Given the limitations of CDSR (restricted to quantitative reviews) and DARE (limited in date up to 2015) it was felt prudent to search other databases for reviews potentially more recent and more qualitative in nature. Three databases were chosen: (1) MEDLINE (2016); (2) CINAHL Complete (2016), and (3) PsycINFO (2016). Investigating results from these databases provided a broader picture of the known literature.

Explicit statement of the search terms—for both the systematic review databases and the wider search databases—can be found in Supplementary Appendices 3 and 4. Three key areas identified (dementia, carers, and wellbeing) are informed by review focus and background reading on dementia. The three key areas were explored for suitable synonyms and related words. Whether or not to include “quality of life” in the search terms proved a difficult decision to make a priori. The decision to exclude the term was justified by a recognized lack of conceptual clarify and specified relationship to wellbeing. Quality of life has been considered a vague, difficult concept to define, with little consistency and may include a range of indicators (EUROSTAT, 2015). Including quality of life in the search criteria of this review had the potential, therefore, to overwhelm, confuse, and distort the focus on the concept of wellbeing. The Results and Discussion sections will demonstrate, however, that this research suggests that quality of life may be a constituent component of a multi-layered understanding of wellbeing. For the EBSCOhost databases, an additional layer of searching was required to ensure that the search narrowed to systematic reviews and reviews systematic in nature. Strategies to achieve this were informed by Montori, Wilczynski, Morgan, & Hayes, (2005) and Wilcynski, Haynes, & The Hedges Team (2007).

The terms and concepts being researched (dementia, carers, and wellbeing) are very broad in nature. It was decided prior to searching to limit results to the abstracts of reviews, where possible, as this would mean only relevant results were recorded. This ensures that the results gather well-crafted abstracts, where guiding terms are strongly identified to enable appropriate information retrieval (Chatterley & Dennet, 2012). As this is a review of reviews, looking for strict analytical and intellectual rigor, so-called “grey” literature was not considered appropriate to be included in the search protocol. For review purposes, grey literature is broadly defined as material not controlled by commercial publishers (Grey Literature Report, n.d.) in a conventional way and difficult to identify or obtain via usual systematic review routes.

Quality Appraisal

The review protocol was submitted to PROSPERO (Supplementary Appendix 1) prior to the search process starting. Providing an a priori protocol and submitting this in advance of research beginning is recognized as good practice by PROSPERO and the AMSTAR (2015) guidelines. The AMSTAR tool was identified as a suitable and validated method (Pollock, Fernandes, Becker, Featherstone, & Hartling, 2016; Pollock, Fernandes, & Hartling, 2017; Smith et al., 2011) to assess the quality of systematic reviews. This is achieved through by a checklist of 11 questions determining the quality of the systematic review (see Table 1 for a detailed list of AMSTAR questions). Pollock et al. (2016, 2017) have evaluated the appropriate use of AMSTAR for reviewing systematic reviews in health care. Pollock et al. (2017) make four specific recommendations. First, quality assessments should be conducted independently, in duplicate, with a process for consensus. This was achieved in this review by the authors independently scoring the chosen reviews by the AMSTAR guidelines, meeting to discuss differences to reach consensus. Second, to promote transparency authors should “provide breakdowns of individual AMSTAR questions” for all of the selected systematic reviews (Pollock et al., 2017, p. 9). A table (Table 1) showing each reviews result, question by question, is therefore provided in the findings. Third, despite some debate surrounding overall AMSTAR scores, such as whether each question is of equal importance or value, Pollock et al. (2017) argue that there is a precedent for reporting overall scores in overviews of healthcare interventions. This review has, therefore, provided the total AMSTAR score for each included review. Fourth, Pollock et al. (2017) demonstrate the reliability of the AMSTAR tool for assessing the quality of systematic reviews. This is the case for reviews both in established Cochrane databases such as CDSR and DARE, and other systematic reviews elsewhere. The AMSTAR results have therefore been used to help reach conclusions in this review.

Table 1.

AMSTAR Results

| Boots et al. (2014) | Caceres et al. (2015) | Chien et al. (2011) | Dam et al. (2016) | Feast et al. (2016) | Quinn et al. (2010) | Leung et al. (2017) | Schoenmakers et al. (2010) | Stansfield et al. (2017) | Tyack & Camic (2017) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. “a priori” design provided? | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, N, N | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y |

| 2. Duplicate study selection and data extraction? | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | N, N, N | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y |

| 3. Comprehensive literature search performed? | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y |

| 4. Publication status used as an inclusion criterion? | N, N, N | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | N, CA, N | Y, CA, CA | N, N, N | Y, Y, Y | N, N, N | N, N, N |

| 5. List of studies (included and excluded) provided? | N, N, N | N, N, N | N, N, N | N, N, N | N, N, N | N, N, N | N, N, N | N, N, N | N, N, N | N, N, N |

| 6. Characteristics of the included studies provided? | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | N, CA, N | Y, Y, Y | Y, N, N | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, N, Y | Y, N, Y | Y, Y, Y |

| 7. Scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented? | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | N, N, N | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y |

| 8. Scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions? | N, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | N, N, N | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y |

| 9. Methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate? | N, NA, NA | NA,NA,NA | Y, Y, Y | N, N, N | Y, Y, Y | NA,NA,NA | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | N, N, N | NA,NA,NA |

| 10. Likelihood of publication bias assessed? | N, N, N | N, N, N | N, N, N | N, N, N | N, N, N | N, N, N | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | N, N, N | N, N, N |

| 11. Conflict of interest stated? | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y | N, N, N | Y, Y, Y | Y, Y, Y |

| Overall score out of 11 | 6, 7, 7 | 8, 8, 8 | 8, 8, 8 | 8, 8, 8 | 8, 7, 7 | 5, 3, 3 | 9, 9, 9 | 9, 8, 9 | 7, 6, 7 | 7, 7, 7 |

Note: First column: first author response. Second column (italic): second author response. Third column (bold): consensus response. CA = cannot answer/not enough information provided; N = no; NA = not applicable/not combined/too few studies; Y = yes.

Data Extraction, Analysis, and Synthesis

The AMSTAR (2015) guidelines recommend a minimum of two independent data extractors, with clear procedures in case of disagreement. The first author acted as secondary reviewer and the second author as primary reviewer. The procedure for disagreement was to discuss this to reach consensus, with appeal to a third party if required. Consensus was in fact reached for every decision. Data extraction focused on the primary issue of how wellbeing is understood and then the secondary issue of measurement. The information extracted was compiled into a findings table (see Table 2) providing information on the authors, summary of topic, number of papers reviewed, the aggregate AMSTAR score, the understanding(s) of wellbeing used, how wellbeing was measured, and the key findings. This is provided for each of the included reviews.

Table 2.

Summary of Findings

| Authors | Topic | No | AS | Wellbeing terms | Measurement | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boots et al. (2014) | Internet-based carer supportive interventions | 12 | 7 | Self-efficacy, stress, burden, depression, mental health, QoL, social contact, goals attained | Quantitative measures of self-efficacy, depression, and burden. QoL indicators. Qualitative reporting | Beneficial effects on caregiver confidence, stress, depression, self-efficacy. More research is required |

| Caceres et al. (2015) | Family caregivers’ frontotemporal dementia | 8 | 8 | Burden, depression, physical health, carer– patient relationship | Quantitative measures for burden, mental health, depression, physical health | Family caregivers have unique needs, with special caregiver burden |

| Chien et al. (2011) | Caregiver support groups | 30 | 8 | Psychological Wellbeing, depression, burden, social outcomes | Quantitative measures: psychological wellbeing, depression, burden, and social outcomes | The impact of support groups on caregiver psychological wellbeing, depression, social outcomes was moderate, but smaller in regards to burden |

| Dam et al. (2016) | Impact support interventions for caregivers | 39 | 8 | Social isolation, self- esteem, QoL, depression, and burden | Quantitative measures for social isolation, self-esteem, QoL, depression, and burden | Outcomes do not often match the goals of the interventions. Further research is required |

| Feast et al. (2016) | Relationship behavioral psychological symptoms caregiver wellbeing | 40 | 7 | Distress, burden, depression, and apathy | Quantitative measures for distress, burden, and depression | The relationship between psychological and behavioral symptoms and caregiver wellbeing is varied. Consistent measures for wellbeing required |

| Quinn et al. (2010) | Impact of motivations and meanings on wellbeing | 10 | 3 | Stress, depression, burden, physical health, Carer–patient relationship | Quantitative measures for stress, depression, burden and physical health. Narrative discussion | Limited evidence to demonstrate that motivations and meanings have a positive impact on carer wellbeing |

| Leung et al. (2017) | Effect on carer wellbeing of cognition- based interventions | 9 | 9 | QoL, stress, mood, physical health, mental health, burden, and Carer–patient relationship | Quantitative measures for QoL, physical health, mental health, burden, and carer–patient relationship | Carer involvement in cognition based interventions may improve carer wellbeing. Research required |

| Schoenmakers et al. (2010) | Effect of home care intervention on general wellbeing | 26 | 9 | Burden, depression, stress | Quantitative measures for burden and depression | Home care interventions help carers feel less depressed and burdened. Research required |

| Stansfeld et al. (2017) | Exploring positive outcomes for caregivers | 18 | 7 | Mental health, self- efficacy, spirituality, reward, meaning, and resilience | Quantitative measures for self-efficacy, spirituality, rewards, meaning, and resilience | Further development of measurement scales required. Extrinsic factors influencing wellbeing should also be researched |

| Tyack & Camic (2017) | Impact of touchscreen interventions on wellbeing for patients and caregivers | 16 | 7 | Subjective wellbeing, QoL, and burden | Quantitative measure for burden | Further research is required, including mixed methods |

Note: AS = AMSTAR SCORE; No = Number; QoL = Quality of Life.

Analysis and synthesis involves the bringing together of results from different research studies and ensuring that new knowledge is grounded in the information gleaned from multiple research studies (Ryan, 2013; Smith et al., 2011). For the purposes of this review, the two questions concerning how wellbeing is (i) understood and (ii) measured were synthesized in different ways.

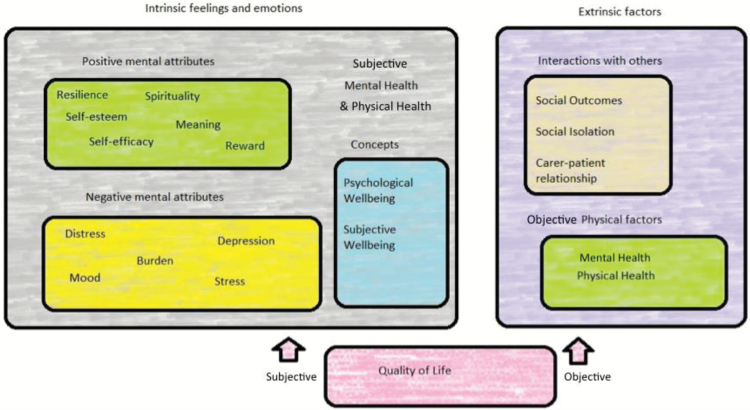

To explore how wellbeing is being understood a narrative synthesis was conducted using an adapted version of the procedures outlined by (Popay et al., 2006). Four stages are identified. Stage 1 involves developing a theoretical model. As this is a systematic review of reviews, this theoretical work has been achieved in the exploration of the issue of the wellbeing in relation to the carers of people of dementia, and the conceptual discussions surrounding the meaning of wellbeing. Stage 2 involved developing a “preliminary synthesis” whereby the results of the included studies are organized so that “patterns across them” can be identified (Popay et al., 2006, p. 13). A table of wellbeing terms (see Table 3) provides this preliminary synthesis and is further reported in the results section. Tabulation is one of the seven recognized techniques recommended for this stage as it is particularly useful developing initial descriptions of the studies and the relationships between them (Popay et al., 2006, p. 17). Stage 3 builds on the preliminary findings to explore relationships within and between studies. The relationships of interest are highlighted as (1) those between characteristics of individual studies and reported findings, and (2) those between the findings of different studies (Popay et al., 2006, p. 14). The concept map for this review can be found further below (see Figure 1). As a mid-summary tool, this map attempts to bring together the topics identified into core themes, common within and across studies. The final stage (Stage 4) is to assess the robustness of the synthesis. This is completed in this review in the limitations section, which includes reflection on the synthesis process.

Table 3.

Wellbeing Terms: Represents the Frequency by Which the Number of Reviews Characterize and Understand Wellbeing Using Specific Terms

| Wellbeing term | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Burden | 10 |

| Depression | 8 |

| Stress | 5 |

| Mental health | 4 |

| Quality of life | 4 |

| Physical health | 3 |

| Carer–patient relationship | 3 |

| Self-efficacy | 2 |

| Social outcomes | 1 |

| Social isolation | 1 |

| Self-esteem | 1 |

| Distress | 1 |

| Mood | 1 |

| Psychological wellbeing | 1 |

| Spirituality | 1 |

| Reward | 1 |

| Meaning | 1 |

| Resilience | 1 |

| Subjective wellbeing | 1 |

| Goals attained | 1 |

| Social contact | 1 |

| Apathy | 1 |

Figure 1.

Wellbeing concept map detailing an initial breakdown of the concept into intrinsic and extrinsic aspects of wellbeing, each containing a range of factors. The relationship between quality of life and wellbeing is complex, with this map suggesting that quality of life (understood as having subjective and objective factors) is a component part of wellbeing.

To analyse the secondary issue of how wellbeing is being measured in the selected reviews was a simpler task for the purposes of this review. We were interested at the broad level as to how the wellbeing of carers of people with dementia is being measured, whether that is through qualitative and/or quantitative methods, and whether it is an objective assessment, or carer’s expressions, of their wellbeing. The findings table (Table 2) provides this level of information.

Results

Selected Reviews

The search was conducted as outlined in the protocol submitted to PROSPERO and the search strategy explained above. The initial search returned 54 reviews from the Systematic Review databases CDSR and DARE, with a further 101 reviews identified through the EBSCOhost search engine for CINHAL Complete, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO databases. A summary of the EBSCOhost search process can be found in Supplementary Appendix 6. With duplicates removed, this resulted in 153 reviews to be considered. This was agreed (by authors) to be a manageable number for a more detailed search and screening process. No changes were therefore made to the search strategy.

Following the initial search, the 153 abstracts were read and assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Supplementary Appendix 2). This resulted in 123 reviews being excluded. The three most common reasons for this were: (1) the review not being systematic in nature, most commonly literature, or narrative reviews; (2) the review focusing primarily or exclusively on the person with dementia rather than the carer and; (3) the topic of wellbeing was not included in the findings of the review. The 30 remaining reviews were read in detail to indicate if they did, in fact, meet these criteria. Eleven reviews were rejected at this stage, six because the issue of caring and carers was not a focus of the review, three because this could not be identified as a systematic review according to known protocol, and two for specific focus on quality of life as opposed to wellbeing.

The remaining 19 reviews were reread and assessed for their relevance and applicability to the research question. Consensus was reached on the inclusion of 10 and the exclusion of 9 reviews. Table 1 illustrates this process and includes first author review, second author review, and agreed consensus. A list of the excluded reviews, and the reasons for their exclusion, can be found in Supplementary Appendix 7. This process raised questions concerning the search strategy, as reviews were rejected for their focus on “Quality of Life” as opposed to wellbeing. In some cases (such as Farina et al., 2017) this left some detailed and developed reviews excluded, with significant crossover in themes identified in included reviews. The relationship between quality of life and wellbeing will be discussed further below.

A full PRISMA (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009) statement is provided in Supplementary Appendix 5. An initial summary of the selected reviews and their findings is provided in Table 2.

Quality Appraisal Results

The AMSTAR tool and guidelines were used to assess the quality of the selected reviews (Tables 1 and 2). Quality assessment of the included studies was carried out in all the reviews except for Quinn, Clare, & Woods (2010). This may have been due to the qualitative nature of the studies included, although this does not mean a quality appraisal should not have been completed. The result of the methods used to combine findings was mixed. Four reviews (Boots, de Vugt, van Knippenburg, Kempen, & Verhey, 2014; Caceres, Frank, Jun, Martelly, & Sadarangani, 2015; Quinn et al., 2010; Tyack & Camic, 2017) included findings so diffuse that combining made little sense, two reviews (Dam, de Vugt, Klinkenberg, Verhey, & von Boxtel, 2016; Stansfeld et al., 2017) did not describe adequately the method used for synthesis, the remaining four were deemed appropriate. The totaled scores show a range of quality in the selected reviews from three for Quinn et al. (2010) at lowest, to nine for Leung et al. (2017) and Schoenmakers, Buntinx, & DeLepelaire (2010) at highest. The mean average score of 7.3, demonstrating that, with the exception of Quinn et al. (2010), the standard of reviews was high. This gives robustness to the conclusions that can be drawn in this systematic review of reviews.

Consideration was given as to whether, following these results, to exclude the findings of Quinn et al. (2010) from the subsequent analysis and synthesis. Pollock et al. (2017, p. 2) discuss the suitability of using AMSTAR results to inform inclusion and exclusion decisions. The argument for this is that poorly conducted systematic reviews could increase the complexity of synthesizing findings between reviews, and may have deficiencies in their findings that influence the outcome of the systematic review of reviews. In this instance, Quinn et al. (2010) reach similar conclusions to other, higher scoring, included reviews, and used concepts outlined in these other reviews to describe wellbeing. As such, it was agreed that including Quinn et al. (2010) would not distort the overall findings.

Analysis and Synthesis of Results: Understanding Wellbeing

Table 2 provides an initial summary of the terms used to describe and characterize wellbeing in the 10 selected reviews. This information enables a preliminary synthesis to be completed, by providing a summary list of the terms used, and their frequency across the reviews. This information is presented in Table 3 and represents the frequency by which the reviews characterize and understand well-being using specific terms, for example burden (10 reviews), depression (8 reviews), or stress (5 reviews). Here, we can see the aggregate score for each of the terms raised.

Burden was the most commonly used term used to characterize wellbeing, with all (10) reviews mentioning it in their discussion. As outlined, the notion of “caregiver burden” is well defined in the literature. Depression (8) was the next most common term, with reviews using the level of depression to describe the amount of carer wellbeing. Other negative emotions featured across the papers: social isolation (1), distress (1), mood (1), and apathy (1). Positive emotions were mentioned less frequently with self-efficacy (2), self-esteem (1), reward (1), meaning (1), resilience (1), spirituality (1), and goals attained (1) all appearing. The social aspect of being a carer was mentioned in a number of reviews, expressed in places as the carer–patient relationship (3), social outcomes (1), and isolation (1). Different aspects of wellbeing were separated in the reviews by distinguishing between mental (4) and physical (3) aspects of wellbeing, and by drawing distinctions between subjective (1) and psychological wellbeing (1). Quality of life also featured as a component part of wellbeing in four of the selected reviews.

Core themes were identified using a constant comparative process comparing relative frequencies of key themes and terms to enable initial mapping. The first and second authors completed this procedure independently. Similarities, consistencies and agreed consensus ensured reliability and trustworthiness of this thematic process. The preliminary findings were developed into a concept map (Figure 1). The first larger box on the left in Figure 1 brings together themes under the heading of “intrinsic feelings and emotions”. These are the subjective and personal elements of wellbeing. Within this, at the bottom left, are the negative mental attributes such as burden, depression, and stress. As Stansfeld et al. (2017, p. 1282) describe it, wellbeing is often understood on the basis of a “loss–deficit model, […] measuring well-being by the absence of negative factors such as stress and depression.” This emphasis on deficit is reinforced by (Schoenmakers et al., 2010, p. 45):

[Caregivers] well-being expressed in terms of burden, depression, or dysphoria and stress are now acknowledged to be appropriate in assessing the effect of an intervention on family caregivers in dementia[.]

This “loss–deficit” understanding of wellbeing is prevalent across other reviews. (Boots et al., 2014, p. 332) describe enhancing wellbeing as “reducing care burden and depression”. (Caceres et al., 2015, p. 72) introduce wellbeing in the context of “caregiver burden”. Feast, Moniz-Cook, Stoner, Charlesworth, & Orrell (2016, p. 1762) argue that carer’s outcomes should be understood in terms of “distress, burden, strain [and] stress”.

In contrast to these negative attributes, yet within the same overall “intrinsic” heading, wellbeing is understood in a more positive light in several reviews, evidenced by the references to meaning, reward and self-efficacy outlined in Table 3. (Stansfeld et al., 2017, p. 1294) claim that there is increasing recognition in the “importance of positive psychology in measuring and understanding well-being”, but that more theoretical work is needed in support. Boots et al. (2014, p. 338) note that a few of the studies reviewed examined the “positive aspects of caregiving”. (Quinn et al. 2010) discuss the kind of positive motivations and meanings that contribute to carer wellbeing.

Attempts to conceptualize this intrinsic aspect of wellbeing are also included in this heading. (Chien et al., 2011) use the term “psychological wellbeing”, where this is understood as an individual’s mental health. This explains the reason why subjective “mental and physical health” appear outside of the boxes in the intrinsic theme, as they are relevant to all these intrinsic factors. Tyack & Camic (2017, p. 1262) use the term “subjective wellbeing” to describe the “experience of positive emotion, low levels of negative emotions, and high life satisfaction.”

The second key heading—the main box on the right of the concept map—brings together the extrinsic factors concerning wellbeing. These are elements of wellbeing beyond the subjective mental state or psychological felt experience of individuals. This can be external objects, people, or indeed relationships. Objective aspects of physical and mental health are also included here; which would include facts about an individual’s status beyond their felt emotion or psychological state. As Stansfeld et al. (2017, p. 1294) state in their study limitations, this extrinsic element has often been overlooked:

This review did not extend to extrinsic factors that may influence well-being and only searched for intrinsic positive psychology factors, in order to contain the breadth of the review. Therefore, future authors may wish to conduct a review on positive psychology outcome measures related to extrinsic factors such as social support and external locus of control to explore how far these aspects contribute to well-being.

A number of the selected reviews for this review do study such extrinsic factors. The patient–carer relationship is particularly prominent in this regard. In their assessment of “touchscreen-based interventions” Tyack & Camic (2017, p.1275) highlight the importance of the carer–patient dyad in promoting “both members’ well-being”. Quinn et al. (2010, p. 52) describe how the pre-dementia relationship between a person with dementia and their carer plays a role in both their experiences of care. Leung et al. (2017) develop this point further in discussing the potential “enriching” process in caregiving, a process that “only occurs either within the context of an existing positive relationship or being motivated to improve the relationship.” (Caceres et al., 2015, p. 75) discuss how changes brought about by frontotemporal dementia create emotional distance between the person with dementia and carer: “The loss of shared meaning that occurs from this experience leaves caregivers feeling isolated and also gives way to loss of caregiver self-esteem.” Frustratingly, however, none of the reviews discuss the relationship between the intrinsic and extrinsic elements of wellbeing. The distinction will not always be a clear one. The impact of the relationship with the person with dementia may be an extrinsic factor, but it will also be influence and be influenced by intrinsic, subjective, experiences. We are left, then, agreeing with Stansfeld et al. (2017) that more work exploring the relationship between the subjective and objective influences on carer wellbeing is much needed.

Underpinning and related to both intrinsic and extrinsic factors is the concept “Quality of Life”. It may be seen as relating to felt subjective feeling, or a range of external factors associated with an individual life, or indeed about both. As indicated above, the relationship between quality of life and wellbeing has been contested. The findings of this review of reviews unfortunately do not provide a clear consensus. For some reviews, quality of life is seen as a component part of wellbeing. Leung et al. (2017), for example, state that the components of carer wellbeing include mood, physical health, mental health, and quality of life. For other reviews, such as Tyack & Camic (2017, p. 1262), quality of life is “synonymous with subjective well-being”, suggesting it refers to just the intrinsic felt experience of individuals. Other reviews simply use the terms wellbeing and quality of life interchangeably. This is why quality of life has a place in the wellbeing concept map, but clarifying how the two concepts intersect remains problematic due to inconsistent conceptualization across studies. Developing more sophisticated conceptual models that define and separate quality of life and wellbeing will enable greater consensus and methodological precision.

Measuring Wellbeing

Table 2 demonstrates that all the included reviews involved measuring wellbeing with quantitative scales, either through self-assessment or agreed scales for various mental states, particularly for negative emotions. As Schoenmakers et al. (2010, p. 54) put it: “Negative feelings are often described in terms of depression or stress and assessed quantitatively with the aid of depression scales.”

The findings demonstrate a wide range and variety of measurement scales and approaches within and between the reviews. Feast et al. (2016, p. 1764) highlight that even when research considered the same issue—distress for example—the articles they reviewed measured these outcomes differently. Leung et al. (2017) demonstrate that across the papers they reviewed, four different scales were used to measure one component of wellbeing (quality of life), whereas six different scales were used to measure carer depression, two different scales were used to measure physical health, two different scales were used to measure the strength of the carer–patient relationship, and a further two scales were used to measure carer burden. Compounding this, the measurements used have not been of consistent quality or large enough in sample size (Leung et al. 2017, p. 384). As Table 2 demonstrates, only Chien et al. (2011), Dam et al. (2016), Feast et al. (2016), and Schoenmakers et al. (2010) had more than 20 research papers included for analysis in their reviews.

Dam et al. (2016) complain that even when appropriate areas of study for carer wellbeing are identified they are not actually measured properly: “Remarkably, 44% of the intervention studies aiming to improve social support actually did not include formal measures of social support.” The conclusion Stansfeld et al. (2017) reach—that more development of measurement scales associated with wellbeing is required—is an appropriate one. A sharper conception of what wellbeing is, and how it should be understood in the context of carers of people with dementia, ought to provide a clearer picture of what should be measured.

Discussion

Understanding Wellbeing

Wellbeing is a complex concept and one difficult to define. For people affected by dementia, creating the conditions to continue to thrive requires continued investment in the wellbeing of carers. This review highlights the need standardized and robust measurements to enhance research in this area and ones that are cognizant of wellbeing as a multi-faceted concept.

The findings of this review clearly demonstrate that no clear, settled, consensus has been reached as to what wellbeing is, or how best to understand it, in current healthcare research. The area of most agreement is what (Stansfeld et al., 2017) call the “loss–deficit model”; that individual wellbeing can be understood in terms of moderating or diminishing the levels of stress, burden, depression or anxiety a person must endure. All the included reviews mentioned burden when discussing wellbeing.

Whilst the research identified in this review continues to look at wellbeing in terms of this loss–deficit model, wider discussion around wellbeing has become more complex and sophisticated. Consider, for example, the recent What Works Wellbeing [WWW] Scoping Report (Brown et al., 2017). This report identifies seven key domains of wellbeing: (1) Personal wellbeing, (2) Economy, (3) Education and childhood, (4) Equality, (5) Health, (6) Place, and (7) Social relationships. Each of these domains has a range of indicators, “11 are objective, 14 are subjective” (2017, p. 8). The Social Care Institute for Excellence [SCIE] (2017) provide guidance to professionals on how to understand wellbeing in a legislative context. They argue that wellbeing has nine key elements: (1) personal dignity, (2) emotional wellbeing, (3) protection from abuse or neglect, (4) control over everyday life, (5) work, education and training, (6) social, (7) domestic, (8) accommodation, and (9) contribution to society. The Royal Surgical Aid Society [RSAS] (2016) updated Literature Review discusses in detail the needs of carers, identifying a range of psychological, physical, and social outcomes that influence the health and wellbeing of the carer.

Given this richness, the findings of this systematic review of reviews suggest that current healthcare research has not kept pace with wider discussions surrounding wellbeing, and may be out of step with how the public, professionals, and legislators understand the term. Reliance on the loss–deficit model appears too simplistic and underdeveloped in comparison to the discussions surrounding the concept wellbeing in wider debates. By not reflecting current discussions and developments surrounding wellbeing, contemporary health research could be seen to be falling short and does not fully capture the lived experience of caregivers’ wellbeing. While it is appropriate to measure negative aspects of caregiver wellbeing, this is not a comprehensive approach that also considers positive aspects. Whilst this criticism seems valid, it should be noted that the ingredients for a more sophisticated understanding of wellbeing can be found in the reviews considered is this systematic review. The concept map (Figure 1) developed here through a synthesis of findings coheres with both the WWW and SCIE models for wellbeing; it recognizes the tension between intrinsic (subjective) and extrinsic (objective) aspects of wellbeing, and brings out the range of positive and negative factors influencing individuals. The concept map recognizes the different aspects of wellbeing and challenges us to consider how they relate to one another. It is true to say that the concept map would need further development to outline and delineate all the seven or nine factors, but it shows that the resources for a richer notion of wellbeing is there in the current literature. This review lays the groundwork for a new theoretical or conceptual approach to measuring dementia caregiver wellbeing as a multidimensional construct.

The uneasy and uncertain relationship between quality of life and wellbeing was again revealed in this systematic review. It should be expected, however, that developing more sophisticated models of wellbeing will allow for closer inspection of this question. It is clear that “quality of life” has an important conceptual role to play in our understanding of carer experiences and carer wellbeing. This is evidenced, for example, by the current research project funded by the Alzheimer’s Society (2017) into developing a measurement tool for quality of life for carers of people with dementia. Precisely where to place it remains a challenge.

Measuring Wellbeing

Dementia is a progressive and profoundly complicated condition. Understanding caregiver wellbeing therefore warrants a complex research approach. The evidence presented in this review highlights the need for clear and consistent measurement regarding wellbeing to enable comparison across and between research into the lives of carers of people with dementia. As models are developed, it should become clearer as to what needs to be measured. But the wide range of different approaches to, say, measuring depression or stress, will continue to make this a challenging research area. The reviews considered here all used quantitative measurement tools, with only two (Boots et al., 2014; Quinn et al., 2010) using narrative or qualitative material to enhance their findings. Given the complex definition and understand of wellbeing emerging in the literature, we ought to expect more sophisticated measurement taking place, including mixed and blended methods. Adopting mixed and blended methods may provide the appropriate and diverse range of method required to examine the same phenomenon and provide more in-depth information on participants’ experiences and feelings (Morse & Field, 1996).

Limitations

Methodology

A systematic review of reviews has been completed. It is worth noting the potential limitations of this approach. As Thomson et al. (2010, p. 209) rightly point out: such overviews are only as good as the systematic reviews on which they are based. Smith et al. (2011, p. 5) stress how important it is that data from individual studies are not used more than once across the review, for risk of distorting the conclusions. Care was taken in the design and implementation of this review to provide accurate reflection of the research literature, and robust quality assessment. Nevertheless, there remains the small risk of bias in the findings. For example, Martin Orrell appears as a named author in three of the reviews selected: Feast et al. (2016), Leung et al. (2017), and Stansfeld et al. (2017). Whilst there does not appear to be duplication of studies between these reviews, it is important to recognize connections in authorship between them, and the potential this has to distort the findings.

Narrative Synthesis

Narrative synthesis is a complex process. This systematic review of reviews has completed a limited narrative synthesis, using an adapted version of the stages identified by Popay et al. (2006). Tabulation and concept mapping exercises did provide valuable insight and enabled synthesis within and between reviews to be completed. Popay et al. (2006) identify other, more sophisticated methods that could be used: such as a thematic analysis to form a preliminary synthesis, or conceptual triangulation for exploring relationships. As such, this review should be seen as the starting point for a fully developed synthesis, building on the groundwork completed here.

Conclusion

This review provides a systematic overview of how the concept of wellbeing is currently being understood and measured in contemporary health research on carers of people with dementia. Current research most commonly understands the wellbeing of dementia caregivers through the loss–deficit model; where enhancing carer wellbeing involves reducing negative emotions such as stress, burden, and depression. This review has identified that, despite the recognized limitations of a loss–deficit model of caregiving, the concept of carer burden continues to dominate the wellbeing field. Such a narrow interpretation misses out on other important elements of wellbeing, such as positive mental aspects and other, extrinsic, factors. The concept of wellbeing has been recognized as multi-faceted and multi-layered in wider contemporary discussions but this review demonstrates that is as yet to be fully reflected in health research on carers of people with dementia.

The concept map developed in this review (Figure 1) provides a useful starting point to consider how the different elements of wellbeing may combine and contribute to the development of a fuller understanding of wellbeing and what it means in a dementia carer context. This is currently underdeveloped in the literature. While the reviews commonly focus on the loss–deficit model, taken together they provide the building blocks for a richer and more sophisticated understanding of wellbeing. It is encouraging that the same kind of questions about extrinsic versus intrinsic, and positive versus negative, elements of wellbeing identified across some of the reviews considered in this systematic review mirror more sophisticated treatments in the grey literature, current policy, and practice discussions (see Brown et al., 2017; Social Care Institute for Excellence, 2017).

This review demonstrates that the measure of wellbeing in relation to the carers of people with dementia lacks consensus between and within studies. Even when appropriate items to measure are agreed upon (such as burden or stress), the way in which those items are measured varies markedly. Standardized and robust measurements are therefore needed to enhance research in this area and ones that are cognizant of wellbeing as a multi-faceted concept. All reviews considered used quantitative tools to measure wellbeing. There may be benefit from developing a more mixed, blended approach to measurement. Given this, further developments embedding a sharpened, richer concept of wellbeing in health research ought to provide researchers with more detailed guidance as to what methods, tools, and indeed evidence they should be looking for in researching carer wellbeing.

Funding

None reported.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

Supplementary Material

References

- Alzheimer Disease International.(2016). World Alzheimer Report 2016: improving healthcare for people living with dementia - coverage, quality and costs now and in the future Retrieved from https://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2016 (Accessed 29 September 2017).

- Alzheimer’s Society.(2017). Developing a method to measure the quality of life in family carers of people with dementia Retrieved from https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/info/20053/research_projects/794/developing_a_method_to_measure_the_quality_of_life_in_family_carers_of_people_with_dementia (Accessed 15 August 2017).

- AMSTAR (2015). “What is AMSTAR” Retrieved from https://amstar.ca/About_Amstar.php (Accessed 15 July 2017).

- Booth A., Clarke M., Dooley G., Ghersi D., Moher D., Petticrew M., & Stewart L (2012). The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: An international prospective register of systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 1, 2. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-1-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boots L. M., de Vugt M. E., van Knippenberg R. J., Kempen G. I., & Verhey F. R (2014). A systematic review of Internet-based supportive interventions for caregivers of patients with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29, 331–344. doi:10.1002/gps.4016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown H., Abdallah S., & Townsley R (2017). Understanding local needs for wellbeing data: measures and indicators Retrieved from https://www.whatworkswellbeing.org/product/understanding-local-needs-for-wellbeing-data/ (Accessed 15 August 2017).

- Caceres B., Frank M., Jun J., Martelly M., & Sadarangani T (2015). Family caregivers of patients with frontotemporal dementia: An integrative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 55, 71–84. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carretero S., Garcés J., Ródenas F., & Sanjosé V (2009). The informal caregiver’s burden of dependent people: Theory and empirical review. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 49, 74–79. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2008.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination.(2017). CRD Database Retrieved from https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/CRDWeb/ (Accessed 3 August 2017).

- Chappel N. L., Dujela C., & Smith A (2016). Caregiver well-being. Intersections of relationship and gender. Research on Aging, 37, 623–645. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2005.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterley T., & Dennet L (2012). Utilisation of search filters in systematic reviews of prognosis questions. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 29, 309–322, 309–322. doi:10.1111/hir.12004/pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien L. Y., Chu H., Guo J. L., Liao Y. M., Chang L. I., Chen C. H., & Chou K. R (2011). Caregiver support groups in patients with dementia: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26, 1089–1098. doi:10.1002/gps.2660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CINAHL (2016). CINAHL Database Retrieved from https://health.ebsco.com/products/the-cinahl-database (Accessed 14 November 2016).

- Cochrane Library.(2017). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Retrieved from http://www.cochranelibrary.com/cochrane-database-of-systematic-reviews/ (Accessed 3 August 2017).

- Cole T.R. (1995). What have we “made” of ageing?The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, i50, 341–343. doi:10:1093/geront/50b.6.s341 [Google Scholar]

- Dam A. E., de Vugt M. E., Klinkenberg I. P., Verhey F. R., & van Boxtel M. P (2016). A systematic review of social support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia: Are they doing what they promise?Maturitas, 85, 117–130. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge R., Daly A., Huyton J., & Sanders L (2012). The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2, 222–235. doi:10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4 [Google Scholar]

- Etters L., Goodall D., & Harrison B. E (2008). Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: A review of the literature. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 20, 423–428. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00342.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUROSTAT.(2015). Quality of life indicators – measuring quality of life Retrieved from http://www.ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Quality_of_life_indicators_-_measuring_quality_of_life (Accessed 15 November 2016).

- Farina N., Page T., Daley S., Brown A., Bowling A., Basset T., … Banerjee S (2017). Factors associated with the quality of life of family carers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 10. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2016.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feast A., Moniz-Cook E., Stoner C., Charlesworth G., & Orrell M (2016). A systematic review of the relationship between behavioral and psychological symptoms (BPSD) and caregiver well-being. International Psychogeriatrics, 28, 1761–1774. doi:10.1017/S1041610216000922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher G. (2016). The Philosophy of well-being: An introduction. London, Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D., Tzuang Y. M., Au A., Brodaty H., Charlesworth G., Gupta R., … Shyu Y-I (2012). International perspectives on nonpharmacological best practices for dementia family caregivers: A review. Clinical Gerontologist, 35, 316–355. doi:10.1080/07317115.2012.678190 [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J. E., Kane R. L., Kane R. A., Clay T., & Newcomer R.C (2005). The Gerontologist, 45, 78–89. doi:10.1093/geront/45.1.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George L. K., & Gwyther L.P (1986). Caregiver well-being: A multidimensional examination of family caregivers of demented adults. Gerontologist, 26, 253–59. doi:10.1093/geront/26.3.253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough D., Oliver S. & Thomas J (2012). An Introduction to Systematic Reviews, SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Grey Literature Report (n.d.) Fill the Gaps in Your Public Health Research Retrieved from http://www.greylit.org/ (Accessed 9 June 2016).

- Herzlich C. (1973). Health and Illness – A social psychological analysis. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leung P., Orgeta V., & Orrell M (2017). The effects on carer well-being of carer involvement in cognition-based interventions for people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32, 372–385. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindert J., Bain P. A., Kubzansky L. D., & Stein C (2015). Well-being measurement and the WHO health policy Health 2010: Systematic review of measurement scales. European Journal of Public Health, 25, 731–740. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cku193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loannidis J. (2009). Integration of evidence from multiple meta-analyses: A primer on umbrella reviews, treatment networks and multiple treatments meta-analyses. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 181, 487–493. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinson M., & Berridge C (2015). Successful aging and its discontents: A systematic review of the social gerontology literature. The Gerontologist, 55, 58–69. doi:10.1093/geront/gnu037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe M., You E., & Tatangelo G (2016). Hearing their voice: A systematic review of dementia family caregivers’ needs. The Gerontologist, 56, e70–e88. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEDLINE.(2016). Fact Sheet Retrieved from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/factsheets/medline.html (Accessed 14 November 2016).

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., & Altman D (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine, 6. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montori V., Wilczynski N., Morgan D., & Haynes B (2005). Optimal search strategies for retrieving systematic reviews from Medline: Analytical survey. British Medical Journal, 330, 68. doi:10.1136/bmj.38336.804167.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J., & Field P (1996). Qualitative research methods for health professionals. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. doi:10. 0803973276 [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M., & Sörensen S (2004). Associations of caregiver stressors and uplifts with subjective well-being and depressive mood: A meta-analytic comparison. Aging & Mental Health, 8, 438–449. doi:10.1080/13607860410001725036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock M., Fernandes R., Becker L., Featherstone R., & Hartling L (2016). What guidance is available for researchers conducting overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions? A scoping review and qualitative metasummary. Systematic Reviews, 190, 5. doi:10.1186/s13643-016-0367-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock M., Fernandes R. M., & Hartling L (2017). Evaluation of AMSTAR to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews in overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 17, 48. doi:10.1186/s12874-017-0325-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay J., Roberts H., Sowden A., Petticrew M., Arai L., Rodgers M., … Duffy S (2006). Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233866356_Guidance_on_the_conduct_of_narrative_synthesis_in_systematic_reviews_A_product_from_the_ESRC_Methods_Programme (Accessed 3 August 2017).

- PROSPERO – International prospective register of systematic reviews (n.d) About PROSPERO Retrieved from https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#aboutpage (Accessed 10 June 2017).

- PsycINFO (2016). PsycINFO Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pubs/databases/psycinfo/index.aspx (Accessed 14 November 2016).

- Quinn C., Clare L., & Woods R. T (2010). The impact of motivations and meanings on the wellbeing of caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 22, 43–55. doi:10.1017/S1041610209990810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J., Bowes A., Gibson G., McCabe L., Reynish E., Rutherford A. C., & Wilinska M (2016). Spotlight on Scotland assets and opportunities for aging research in a shifting socio-political landscape. The Gerontologist, 55, 979–989. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal Surgical Aid Society.(2016). “The experiences, needs, and outcomes for carers of people with dementia: Literature Review” Retrieved from http://www.thersas.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/RSAS-ADS-Experiences-needs-outcomes-for-carers-of-people-with-dementia-Lit-review-2016.pdf (Accessed 2 August 2017).

- Ryan R. (2013). Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group: data synthesis and analysis Retrieved from http://cccrg.cochrane.org (Accessed 3rd August 2017).

- Schoenmakers B., Buntinx F., & DeLepeleire J (2010). Supporting the dementia family caregiver: The effect of home care intervention on general well-being. Aging & mental health, 14, 44–56. doi:10.1080/13607860902845533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith V., Devane D., Begley C. M., & Clarke M (2011). Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11, 15. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social Care Institute for Excellence.(2017). How is Wellbeing Understood Under the Care Act? Retrieved from http://www.scie.org.uk/care-act-2014/assessment-and-eligibility/eligibility/how-is-wellbeing-understood.asp (Accessed 13 August 2017).

- Stansfeld J., Stoner C. R., Wenborn J., Vernooij-Dassen M., Moniz-Cook E., & Orrell M (2017). Positive psychology outcome measures for family caregivers of people living with dementia: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 29, 1281–1296. doi:10.1017/S1041610217000655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C. A., Spilsbury K., Hall J., Birks Y., Barnes C., & Adamson J (2007). Systematic review of information and support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. BMC Geriatrics, 7. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-7-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson D., Russell K., Becker L., Klassen T., & Hartling L (2010). The evolution of a new publication type: Steps and challenges of producing overviews of reviews. Research Synthesis Methods, 1,198–211. doi:10.1002/jrsm.30/abstract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremont G. (2011). Family caregiving in dementia. Medical Health Research, 94, 36–38. Retrieved from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3487163/ (Accessed 3 August 2017). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyack C., & Camic P. M (2017). Touchscreen interventions and the well-being of people with dementia and caregivers: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 29, 1261–1280. doi:10.1017/S1041610217000667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- University of Cambridge (2017). Well-being Institute Retrieved from http://www.wellbeing.group.cam.ac.uk/ (Accessed 24 July 2017).

- Wilczynski N. L., & Haynes R. B; Hedges Team (2007). EMBASE search strategies achieved high sensitivity and specificity for retrieving methodologically sound systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60, 29–33. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. (n.d). Health 2020: the European policy for health and well-being Retrieved from http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-policy/health-2020-the-european-policy-for-health-and-well-being (Accessed 2 August 2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.