Abstract

Background:

The use of radiation therapy in the treatment of retroperitoneal sarcomas has increased in recent years. Its impact on survival and recurrence is unclear.

Methods:

A retrospective propensity score matched (PSM) analysis of patients with primary retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcomas, who underwent resection from 2000 to 2016 at eight institutions of the US Sarcoma Collaborative, was performed. Patients with metastatic disease, desmoid tumors, and palliative resections were excluded.

Results:

Total 425 patients were included, 56 in the neoadjuvant radiation group (neo-RT), 75 in the adjuvant radiation group (adj-RT), and 294 in the no radiotherapy group (no-RT). Median age was 59.5 years, 186 (43.8%) were male with a median follow up of 31.4 months. R0 and R1 resection was achieved in 253 (61.1%) and 143 (34.5%), respectively. Overall 1:1 match of 46 adj-RT and 59 neo-RT patients was performed using histology, sex, age, race, functional status, tumor size, grade, resection status, and chemotherapy. Unadjusted recurrence-free survival (RFS) was 35.9 months (no-RT) vs 33.5 months (neo-RT) and 27.2 months (adj-RT), P = .43 and P = .84, respectively. In the PSM, RFS was 17.6 months (no-RT) vs 33.9 months (neo-RT), P = .28 and 19 months (no-RT) vs 27.2 months (adj-RT), P = .1.

Conclusions:

Use of radiotherapy, both in adjuvent or neoadjuvent setting, was not associated with improved survival or reduced recurrence rate.

Keywords: predictors, radiation therapy, recurrence, retroperitoneal sarcomas

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

Retroperitoneal sarcomas represent a heterogeneous and rare entity of tumors arising from mesenchymal cells with high rates of recurrence that are associated with high mortality. Even though surgical resection is key to the treatment, there remains controversy in the optimal management scheme and the role of chemotherapy and radiation especially given the high histologic variability.

Radiation has been studied in single center and multicenter studies, as well as large dataset studies (SEER, NCDB) with considerable controversy remaining.1-3 Its role is thought to facilitate local control, complete resection, and potentially leading to improved survival as shown in certain studies. ACOSOG-Z9031 was a randomized trial designed to evaluate the role of preoperative radiotherapy combined with surgery vs surgery alone in retroperitoneal sarcomas, with 5-year progression free survival as the primary endpoint. It was closed before completion due to lack of accrual and most recently the STRASS trial4 comparing neoadjuvant vs no radiotherapy, combined with surgery, showed no difference in recurrence-free survival (RFS).

The NCCN guidelines as well as the consensus statement by the Trans-Atlantic RPS Working Group recommend consideration of neoadjuvant radiotherapy in select patients, but do not support the use of postoperative radiotherapy, except for isolated cases where it is deemed necessary.5,6 Without any definitive answers to the role of radiotherapy, further investigation of its role is warranted.

Our aim was to study a large multi-institutional database for the impact of neoadjuvant and adjuvant radiotherapy for retroperitoneal sarcomas. Furthermore, propensity score models were created to attempt to account for biases inherent to a retrospective analysis.

2 ∣. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A prospectively collected multi-institutional database comprising eight institutions participating in the US Sarcoma Collaborative (USSC) was retrospectively reviewed for all patients with retroperitoneal sarcomas that underwent surgical resection from January 2000 to April 2016. USSC is a consortium of the following institutions: Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina; Winship Cancer Institute, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia; Stanford University, Palo Alto, California; The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio; Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin; University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago, Illinois; Washington University, and St Louis, Missouri. Only adult patients with primary retroperitoneal sarcomas and no evidence of metastatic disease or sarcomatosis were analyzed after approval by each respective institutional review board. Patients who received intraoperative radiation therapy (RT) or brachytherapy alone were excluded from this analysis. Basic demographics, clinical, imaging, and pathologic characteristics were reviewed. The primary outcomes were RFS while overall survival (OS; defined as time from diagnosis to date of death), and local recurrence (LR) were secondary outcomes.

2.1 ∣. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each measure (counts and percent’s for categorical measures and medians and ranges for continuous). The neoadjuvant RT (neo-RT) and adjuvant RT (adj-RT) groups were each compared with the no radiotherapy group (no-RT) using χ2 tests or Kruskal-Wallis tests. Primary outcomes among subgroups were compared using Kaplan-Meier survival methods using logrank χ2 tests. Proportional hazards regression models were created first for univariate analyses; multivariable models were created, and included all variables significant at P < .20 in single variable models. Hazard ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated for all variables where P < .10. Statistical significance was assumed for all variables with P < .05. In addition, two propensity score models were estimated, one for neo-RT vs no-RT and one for adj-RT vs no-RT. In each model, the following covariates were included: age, sex, histologic type, tumor size, tumor grade, resection status, and adjuvant chemotherapy. Using the estimated propensity scores, matching was performed to create groups of patients who were balanced on all covariates included in the propensity score models. Balance statistics (χ2or t tests) were examined for the full groups before matching and the matched groups to guarantee that balance was achieved on all covariates. Survival models were then re-fit using the propensity score matched data for each primary outcome for the neo-RT vs no-RT and adj-RT vs no-RT comparisons. For the purposes of the analyses, the histologic groups including 10 patients or less were combined to facilitate data interpretation. Patients that underwent R2 resections were only included in the descriptive tables for reference but were excluded from all the survival and recurrence analyses. SAS (version 9.4, Cary, NC) was used for the statistical processing.

3 ∣. RESULTS

In this cohort of 425 patients with retroperitoneal sarcomas who underwent resection, 56 (13.2%) patients received neo-RT, 75 (17.6%) patients received radiotherapy in the adjuvant setting (adj-RT), and 294 (69.2%) received no radiation (no-RT). Median age was 59.5 years, 186 (43.8%) male, predominantly Caucasian 310 (73.5%), and 393 (97.3%) were functionally independent. The most common histologies in descending order were leiomyosarcomas (28.2%), dedifferentiated liposarcomas (20.2%), well-differentiated liposarcomas (14.1%), other sarcomas (9.6%), and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas (7.8%). There were no statistical differences in sex (P = .81), median age (P = .44), race (P = .81), functional status (P = .72), tumor size (P = .43), resection status (P = .22), lymphovascular invasion (P = .08), and adjacent organ involvement on pathology (P = .31) among the three groups. The predominant histologies in the no-RT group were leiomyosarcomas (27.9%), dedifferentiated liposarcoma (LPS) (18.4%), and well-differentiated LPS (17%); in the neo-RT group were leiomyosarcomas (30.4%), dedifferentiated LPS (28.6%), and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas (19.6%) while in the adj-RT group were leiomyosarcomas (28%), dedifferentiated LPS (21.3%), and sarcoma, other (10.7%); P = .001. In the neo-RT, adj-RT, and no-RT, high-grade tumors comprises 47 (85.5%), 52 (73.2%), and 156 (56.3%), respectively (P < .001). Necrosis was noted in the pathologic specimens of 39 (81.3%) patients in the neo-RT group, in 35 (59.3%) in the adj-RT group, and in 134 (64.1%) in the no-RT group (P = .04). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was administered in 16 (28.6%), 0, and 5 (1.7%) (P < .001) while adjuvant chemotherapy was given in 4 (7.3%), 18 (24.3%), and 37 (12.8%) in the neo-RT, adj-RT, and no-RT group, respectively, (P = .01) (Table 1). Median follow up for the cohort was 31.4 months.

TABLE 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics

| No-RT (n = 294) | Neoadjuvant RT (n = 56) | Adjuvant RT (n = 75) | Total (n = 425) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histology | .001 | ||||

| Carcinosarcoma | 9 (3.1) | 0 | 4 (5.3) | 13 (3.1) | |

| Hemangiopericytoma | 6(2) | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 7 (1.6) | |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 82 (27.9) | 17 (30.4) | 21 (28) | 120 (28.2) | |

| LPS, dedifferentiated | 54 (18.4) | 16 (28.6) | 16 (21.3) | 86 (20.2) | |

| LPS, myxoid/round cell | 5 (1.7) | 0 | 4 (5.3) | 9 (2.1) | |

| LPS, NOS | 7 (2.4) | 0 | 0 | 7 (1.6) | |

| LPS, Well-differentiated | 50 (17) | 3 (5.4) | 7 (9.3) | 60 (14.1) | |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | 3(1) | 0 | 2 (2.7) | 5 (1.2) | |

| Sarcoma, NOS | 14 (4.8) | 5 (8.9) | 1 (1.3) | 20 (4.7) | |

| Stromal sarcoma | 14 (4.8) | 0 | 2 (2.7) | 16 (3.8) | |

| Synovial sarcoma | 5 (1.7) | 1 (1.8) | 2 (2.7) | 8 (1.9) | |

| Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma | 15 (5.1) | 11 (19.6) | 7 (9.3) | 33 (7.8) | |

| Sarcoma, other | 30 (10.2) | 3 (5.4) | 8 (10.7) | 41 (9.6) | |

| Male | 128 (56.5) | 23 (41.1) | 35 (46.7) | 186 (43.8) | .81 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 60 (49, 70.8) | 59.3 (49.8, 70.6) | 58.1 (50.3, 70) | 59.5 (49.4, 70.2) | .44 |

| Race | |||||

| Caucasian | 213 (72.9) | 41 (74.5) | 56 (74.7) | 310 (73.5) | .81 |

| African American | 33 (11.3) | 7 (12.7) | 9 (12) | 49 (11.6) | |

| Latino | 18 (6.2) | 3 (5.5) | 4 (5.3) | 25 (5.9) | |

| Asian | 6 (2.1) | 2 (3.6) | 4 (5.3) | 12 (2.8) | |

| Other | 5 (1.7) | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 6 (1.4) | |

| N/A | 17 (5.8) | 2 (3.6) | 1 (1.3) | 20 (4.7) | |

| Functional status | |||||

| Independent | 269 (97.1) | 51 (96.2) | 73 (98.6) | 393 (97.3) | .72 |

| Dependent | 8 (2.9) | 2 (3.8) | 1 (1.4) | 11 (2.7) | |

| Tumor size, median (IQR) | 14.5 (8.5, 23) | 14.5 (9.6, 20) | 11.2 (7.8, 20) | 14 (8.5, 22) | .43 |

| Final resection status | |||||

| R0 | 180 (63.6) | 30 (53.6) | 43 (57.3) | 253 (61.1) | .22 |

| R1 | 88 (31.1) | 25 (44.6) | 30 (40) | 143 (34.5) | |

| R2 | 15 (5.3) | 1 (1.8) | 2 (2.7) | 18 (4.3) | |

| Combined grade | |||||

| Unspecified | 32 (11.6) | 2 (3.6) | 5 (7) | 39 (9.7) | <.001 |

| Low-Grade | 89 (32.1) | 6 (10.9) | 14 (19.7) | 109 (27) | |

| High-Grade | 156 (56.3) | 47 (85.5) | 52 (73.2) | 255 (63.3) | |

| Necrosis | 134 (64.1) | 39 (81.3) | 35 (59.3) | 208 (65.8) | .04 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 21 (15.6) | 0 | 5 (11.6) | 26 (12.6) | .08 |

| Other organ Involvement None |

141 (61.8) | 30 (60) | 40 (62.5) | 211 (61.7) | … |

| Adherent | 41 (18) | 7(14) | 16 (25) | 64 (18.7) | .31 |

| Invading | 46 (20.2) | 13 (26) | 8 (12.5) | 67 (19.6) | … |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 5 (1.7) | 16 (28.6) | 0 | 21 (5) | <.001 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 37 (12.8) | 4 (7.3) | 18 (24.3) | 59 (14.1) | .012 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; LPS, liposarcoma; N/A, not available; NOS, not otherwise specified; RT, radiation therapy.

3.1 ∣. Radiation treatment details and adverse events

The median radiation dose in the neo-RT group was 50 Gray, interquartile range (IQR: 46.8, 50.4) with 21 of 56 (37.5%) missing dosing information. Overall 12 (28.6%) were treated by external beam radiation and 12 (21.4%) with intensity-modulated radiation therapy, and 28 (50%) had missing information in terms of the radiation technique used. The majority of patients received RT in an academic setting 31 (55.4%), 11 (19.6%) in community setting, and 14 (25%) did not have information regarding the setting. Intraoperative radiation was used in 3 (5.4%) patients and brachytherapy in 2 (3.6%) patients. There were no complications directly related to the radiotherapy recorded.

In the adj-RT group, 72 (96%) received full dose radiation, median dose 50.4 Gray (IQR [45, 54.3], 27 of 75 [36%] missing dosing data), 3 (4%) received adjuvant boost, and median dose 36.25 Gray with 1 of 3 (33.3%) with no dosing information. Total 34 (45.3%) were treated by external beam radiation and 18 (24%) with intensity-modulated radiation therapy, and 23 (30.7%) had missing information in terms of the radiation technique used. The majority of patients were treated in an academic setting 43 (57.3%), 14 (18.7%) in community setting, and 18 (24%) did not have information regarding the setting. Intraoperative radiation was used in 11 (14.7%) patients and brachytherapy in 3 (4%). Radiotherapy related complications were documented in 5 (6.7%) of adj-RT patients with the exact nature not specified.

Overall in-hospital complication rates in the no-RT, neo-RT, and adj-RT were 33.9%, 41.1%, and 28.4%, respectively, P = .32. Similarly, reoperation rates were 7.6%, 3.6%, and 1.4% (P = .1) and readmission rates 10.6%, 16.4%, and 8.3% (P = .34) in the no-RT, neo-RT, and adj-RT groups.

3.2 ∣. Propensity matched groups

After propensity score matching, 46 patients in the neo-RT group were matched to 46 patients in the no-RT group. Covariates included in the matching algorithm were histologic subtype, sex, age, race, functional status, tumor size, resection status, tumor grade, necrosis, lymphovascular invasion, organ involvement on pathology, neoadjuvant, and adjuvant chemotherapy. There were no statistical differences in any of the covariates with the exception of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, 15 (32.6%) in the neo-RT vs 5 (10.9%) in the no-RT group (P = .02). Before matching, this variable had been much more unbalanced (28.6% in neo-RT vs 1.7% in no-RT (P < .0001). Similarly, 59 patients in the adj-RT group were matched 1:1 to the no-RT group and were well balanced on all the aforementioned covariates (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Clinicopathological characteristics after propensity-score matching

| No-RT (n = 46) | Neoadjuvant RT (n = 46) | P value | No-RT (n = 59) | Adjuvant RT (n = 59) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histology | ||||||

| Leiomyosarcoma | 12 | 16 | … | 17 | 19 | … |

| LPS, dedifferentiated | 13 | 11 | … | 14 | 14 | … |

| LPS, well-differentiated | 1 | 1 | 0.88 | 6 | 5 | 0.99 |

| Undifferentiated | 13 | 10 | … | 7 | 6 | … |

| pleomorphic sarcoma | ||||||

| Sarcoma, other | 7 | 8 | … | 15 | 15 | … |

| Male | 17 | 17 | 1 | 30 | 30 | 1 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 64.6 (51.9, 78.9) | 59.3 (50.5, 68.5) | 0.14 | 65.8 (51.9, 77.5) | 58.3 (52, 70) | 0.19 |

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasian | 33 | 31 | 0.55 | 44 | 45 | 0.098 |

| African American | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | ||

| Latino | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Asian | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | ||

| Other | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| N/A | 4 | 2 | 5 | 0 | ||

| Functional status | ||||||

| Independent | 45 | 41 | 0.52 | 57 | 57 | 1 |

| Dependent | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Tumor size, median (IQR) | 15.25 (10.2, 21.0) | 13.75 (9.5, 19.0) | 0.3 | 15 (8, 23) | 12.5 (8.5, 20) | 0.56 |

| Final resection status | ||||||

| R0 | 23 | 26 | … | 32 | 34 | … |

| R1 | 23 | 20 | 0.53 | 27 | 25 | 0.71 |

| Combined grade | ||||||

| Unspecified | 0 | 2 | … | 5 | 4 | … |

| Low-grade | 5 | 4 | 0.35 | 12 | 11 | 0.9 |

| High-grade | 41 | 40 | … | 42 | 44 | … |

| Necrosis | 29 | 32 | 0.75 | 34 | 26 | 0.07 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 3 | 0 | 0.24 | 3 | 5 | 0.23 |

| Other organ involvement | ||||||

| None | 20 | 28 | … | 27 | 30 | … |

| Adherent | 10 | 4 | 0.14 | 10 | 13 | 0.72 |

| Invading | 8 | 10 | … | 8 | 6 | … |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 5 | 15 | 0.02 | 1 | 0 | 0.32 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 3 | 4 | 0.69 | 10 | 13 | 0.49 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; LPS, liposarcoma; N/A, not available; NOS, not otherwise specified; RT, radiation therapy.

3.3 ∣. Multivariate regression analyses

Multivariate regression models were performed for the entire cohort, including radiotherapy (neoadjuvant and adjuvant), chemotherapy (neoadjuvant and adjuvant), histologic type, sex, age, tumor size, tumor grade, and resection status. Tumor size (hazards ratio [HR]: 1.03 per 1 cm increase, P = .002) and tumor grade (HR: 0.34 for unspecified vs high-grade, P = .04) were predictors of RFS.

Tumor size (HR: 1.03 per 1 cm increase, P = .006), R0 resection status (HR: 0.57 for R0 vs R1, P = .05), and dedifferentiated LPS (HR: 2.84, P = .04) were predictors of LR. Well-differentiated liposarcoma histology (HR: 0.2, P = .01), age (HR: 1.04, P < .001), tumor size (HR: 1.03, P = .005), and low-grade tumor (HR: 0.39, P = .02) were predictors of OS. Neither adjuvant nor neoadjuvant radiation were significant predictors in any of these analyses (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Multivariate regression analysis for OS, LR, and RFS

| OS |

LR |

RFS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | P value | HR | P value | HR | P value | |

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy | 1.14 | .69 | 1.18 | .7 | 0.98 | .95 |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | 0.8 | .4 | 0.47 | .07 | 0.7 | .15 |

| Histology | ||||||

| Sarcoma, other (ref) | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 0.69 | .2 | 0.81 | .68 | 1.53 | .14 |

| LPS, dedifferentiated | 0.58 | .12 | 2.84 | .04 | 1.19 | .6 |

| LPS, well-differentiated | 0.2 | .01 | 0.63 | .47 | 0.47 | .14 |

| Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma | 0.6 | .23 | 2.19 | .2 | 1.19 | .67 |

| Female | 0.98 | .94 | 0.84 | .53 | 0.92 | .66 |

| Age | 1.04 | <.001 | 1.01 | .51 | 1.01 | .22 |

| Tumor size | 1.03 | .005 | 1.03 | .006 | 1.03 | .002 |

| Combined grade | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| High-grade (ref) | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Unspecified grade | 0.22 | .01 | 0.75 | .71 | 0.34 | .04 |

| Low-grade | 0.39 | .02 | 1.15 | .78 | 0.62 | .15 |

| R0 resection status | 0.68 | .09 | 0.57 | .05 | 0.71 | .1 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 1.15 | .66 | 0.92 | .85 | 0.87 | .59 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 0.9 | .41 | 1.09 | .88 | 0.75 | .46 |

Abbreviations: LPS, liposarcoma; LR, local recurrence; OS, overall survival; ref, reference group; RFS, recurrence-free survival.

3.4 ∣. Unadjusted and propensity matched survival and LR analyses

3.4.1 ∣. Neoadjuvant radiation

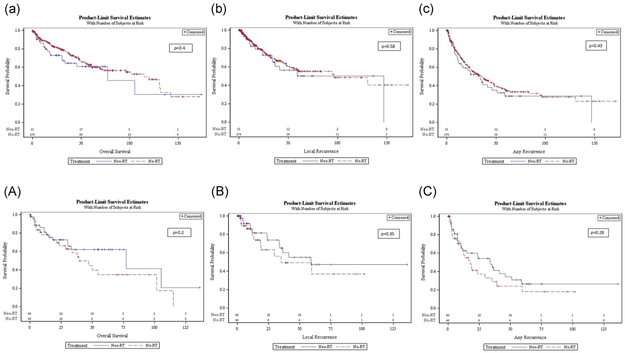

In the unadjusted analysis, OS was 77.24 vs 115 months in the neo-RT vs no-RT group (P = .4) (Figure 1a). LR interval was 146.73 vs 96.49 months in the neo-RT and no-RT group (P = .58) (Figure 1b). RFS in the neo-RT vs no-RT group was 33.54 vs 35.94 months (P = .43) (Figures 1c).

FIGURE 1.

Unadjusted (lower case) and propensity score matched (capital), OS (a, A), LR rate (b, B), and RFS (c, C) Kaplan-Meier curves for the neoadjuvant (blue line) vs no radiation (red line) groups. LR, local recurrence; OS, overall survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In the propensity matched analysis, OS in the neo-RT vs no-RT groups was 77.24 vs 39.1 months (P = 0.19) (Figure 1A). LR interval was 59 vs 35.12 months (P = 0.35) and RFS was 33.87 vs 17.64 months (P = .28), in the neo-RT vs no-RT groups respectively (Figure 1B and 1C).

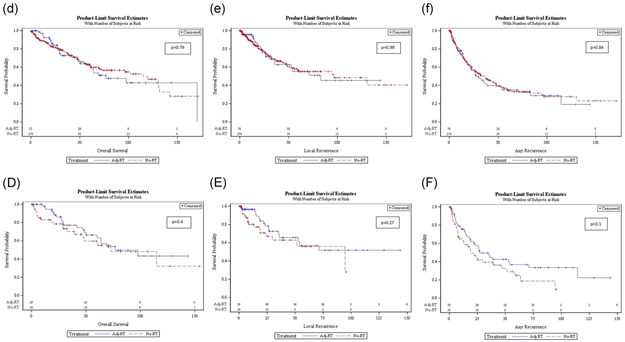

3.4.2 ∣. Adjuvant radiation

In the unadjusted analysis, OS was 76.85 vs 115 months (P = .79) in the adj-RT vs no-RT group (Figure 2d). LR interval was 82.92 vs 96.49 months in the adj-RT vs no-RT group (P = .99) (Figure 2e). RFS in the adj-RT and no-RT group was 27.24 vs 35.94 months (P = .84). (Figure 2f).

FIGURE 2.

Unadjusted (lower case) and propensity score matched (capital), OS (d, D), LR rate (e, E), and RFS (f, F) Kaplan-Meier curves for the adjuvant (blue line) vs no radiation (red line) groups. LR, local recurrence; OS, overall survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In the propensity matched analysis, OS was 76.85 vs 72.74 months (P = .4) in the adj-RT vs no-RT groups (Figure 2D). LR interval was 71.06 vs 94.5 months (P = .27) and RFS was 27.24 vs 18.96 months (P = .1) in the adj-RT vs no-RT groups, respectively (Figure 2E and 2F).

4 ∣. DISCUSSION

The role of neoadjuvant or adjuvant radiation treatment in the treatment of retroperitoneal sarcomas has been debated.7 The use of RT is individualized through multidisciplinary discussion and based on multi-institutional or large dataset studies. Most recently, the STRASS trial showed no difference in RFS between a neo-RT and surgery vs surgery alone arms with the exception of well-differentiated liposarcomas in an unplanned subset analysis.4 In this multicenter study, there was no difference in OS in the no-RT, neo-RT, adj-RT groups on unadjusted and propensity-score matched analyses. However, in the propensity matched analysis, there was a trend towards improved RFS with both neoadjuvant and adjuvant radiation, while neoadjuvant seemed to improve LR rates as well.

Compared with large recent and historic cohorts, an increase in the use of neo-RT (13.2% received neo-RT) and a decrease in the use of adjuvant radiation (17.6% received adj-RT) was noted in our cohort.2,3 These results are in accordance with the NCCN guidelines supporting the use of neo-RT preferential as it tends to spare the adjacent normal tissues, allows for more time to document absence of disease progression, facilitates local control with a favorable side effect profile.5 There were no complications directly related to neo-RT and 6.7% of the adj-RT patients had radiation-related complications. In-hospital complication and reoperation rates were also not statistically different during the index admission and the three groups had comparable readmission rates.

Our results showed no difference in LR rates in the RT groups vs no-RT even though after propensity matching, the neo-RT group appeared to have a trend towards decreased LRs. These results are in discordance with studies recently published including a recent metaanalysis that found improved LR rates with neo-RT and adj-RT.8,9 The heterogeneity in histologic subtypes, tumor grade, and resection status constitute well known potential sources for variability in the responses to radiotherapy. The baseline characteristics of our group are similar to the published reports in the literature, with more than 60% negative margin resections, 63% high-grade tumors, tumors with median maximum diameter of 14 cm, while more than one-third exhibited histologic evidence of invasion or adherence to adjacent organ. Post hoc analyses of specific histologies also failed to identify any statistically significant LR or survival results after radiation.

Furthermore, there was no difference in recurrence-free and OS rate between radiation and no radiation groups. A trend towards improved survival was noted for the propensity matched radiation groups, but this was not statistically significant. Tumor grade and size were found to be significant predictors of survival in accordance with multiple previous reports.1,8,10,11 It is possible that the large tumor sizes included in this study did not allow for a statistical difference in recurrence rate to be shown as there is a higher chance for missing a close positive margin or not covering the area at risk with sufficient radiation dose. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy has been shown to decrease the area at risk while at the same time minimizing exposure of adjacent normal tissues to radiation.12,13 The impact of radiation technique impact could not be assessed in the current study due to lack of adequate reporting. In a recent NCDB study investigating the role of radiation, it was the small size, high-grade tumors that benefited the most from radiation leading to improved OS through a decrease in LRs.1

Patients in the neo-RT group were more likely to receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy both in the overall and in the matched cohort, but there was no associated improvement in survival or recurrence in the regression model. The role of preoperative chemotherapy is endorsed in the guidelines and supported by the EORTC 62961-ESHO 95.5,6,14 However, the data are limited to chemosensitive histologies and to highly selected patients, particularly with unresectable or borderline resectable disease.15-18

The current multicenter study is one of the largest published and does not support the use of radiation in the treatment of retroperitoneal sarcomas but several limitations have to be acknowledged. The retrospective nature of the report predisposes the analysis to inherent flaws and biases despite the granularity of the data collected. There was a significant number of missing data in the dosing and radiation technique used that could also constitute a confounder.19 Institution specific therapeutic protocols could have skewed the data even though they provide a real-world current picture of management for this heterogeneous tumor type. Although the data collection spanned 17 years and included eight large-volume institutions, the number of patients included could have been a potential barrier to allow for a demonstration of statistical difference in the radiation groups.

5 ∣. CONCLUSIONS

This multicenter study of patients with retroperitoneal sarcomas treated with curative intent surgery showed no improvement in OS, associated with the use of either neoadjuvent or adjuvent RT on both unadjusted and propensity matched analysis. There was a nonstatistically significant trend towards improved disease free survival on the propensity matched neo-RT and adj-RT groups. These results need to be interpreted with caution and warrant further investigation in the role of radiation particularly in the neoadjuvant setting.

Acknowledgments

Funding information

NCI, Grant/Award Number: NCI CCSG P30CA012197

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

DATA ACCESSIBILITY

Data are available upon request from the author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leiting JL, Bergquist JR, Hernandez MC, et al. Radiation therapy for retroperitoneal sarcomas: influences of histology, grade, and size. Sarcoma. 2018. December 5;2018:1–8. 10.1155/2018/7972389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nussbaum DP, Rushing CN, Lane WO, et al. Preoperative or postoperative radiotherapy versus surgery alone for retroperitoneal sarcoma: a case-control, propensity score-matched analysis of a nationwide clinical oncology database. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(7):966–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nussbaum DP, Speicher PJ, Gulack BC, et al. Long-term oncologic outcomes after neoadjuvant radiation therapy for retroperitoneal sarcomas. Ann Surg. 2015;262(1):163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonvalot S, Gronchi A, Le Pechoux C, et al. STRASS (EORTC 62092): A phase III randomized study of preoperative radiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for patients with retroperitoneal sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15 suppl):11001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Mehren M, Randall RL, Benjamin RS, et al. Soft tissue sarcoma, version 2.2018, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(5):536–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trans-Atlantic RPS Working Group. Management of primary retroperitoneal sarcoma (RPS) in the adult: a consensus approach from the Trans-Atlantic RPS Working Group. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22: 256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohindra P, Neuman HB, Kozak KR. The role of radiation in retroperitoneal sarcomas. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2013;14:425–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toulmonde M, Bonvalot S, Méeus P, et al. French Sarcoma Group. Retroperitoneal sarcomas: patterns of care at diagnosis, prognostic factors and focus on main histological subtypes: a multicenter analysis of the French Sarcoma Group. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:735–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albertsmeier M, Rauch A, Roeder F, et al. External beam radiation therapy for resectable soft tissue sarcoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;25:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zlotecki RA, Katz TS, Morris CG, Lind DS, Hochwald SN. Adjuvant radiation therapy for resectable retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma: The University of Florida experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2005;28:310–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kattan MW, Leung DH, Brennan MF. Postoperative nomogram for 12-year sarcoma-specific death. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koshy M, Landry JC, Lawson JD, et al. Intensity modulated radiation therapy for retroperitoneal sarcoma: a case for dose escalation and organ at risk toxicity reduction. Sarcoma. 2003;7(3-4):137–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bossi A, De Wever I, Van Limbergen E, Vanstraelen B. Intensity modulated radiation-therapy for preoperative posterior abdominal wall irradiation of retroperitoneal liposarcomas. Intl J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67(1):164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Issels RD, Lindner LH, Verweij J, et al. Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus regional hyperthermia on long-term outcomes among patients with localized high-risk soft tissue sarcoma: the EORTC 62961-ESHO 95 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:483–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Movva S, von Mehren M, Ross EA, Handorf E. Patterns of chemotherapy administration in high-risk soft tissue sarcoma and impact on overall survival. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13:1366–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasquali S, Gronchi A. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in soft tissue sarcomas: latest evidence and clinical implications. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2017;9:415–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gortzak E, Azzarelli A, Buesa J, et al. A randomised phase II study on neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for ‘high-risk’ adult soft-tissue sarcoma. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:1096–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miura JT, Charlson J, Gamblin TC, et al. Impact of chemotherapy on survival in surgically resected retroperitoneal sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:1386–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zagar TM, Shenk RR, Kim JA, et al. Radiation therapy in addition to gross total resection of retroperitoneal sarcoma results in prolonged survival: results from a single institutional study. J Oncol. 2008; 2008:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]