Abstract

Purpose of review:

Currently, the clinical evaluation of neuro-ophthalmologic diseases are mainly focused on identifying stages where structural or functional damage occur. Recognition of retinal ganglion cell (RGC) functional patterns as well as monitoring RGC dysfunction can be performed using steady-state pattern electroretinogram (PERG). The analysis of the amplitude and latency shift aid on providing information on early damage or monitoring of the RGC, allowing for prompt clinical intervention and management modification, potentially changing the natural history of the disease. The purpose of this article is to review the latest findings in PERG, in early manifest glaucoma, non arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy, multiple sclerosis with unilateral recovered optic neuritis and its fellow eyes.

Recent Findings:

The steady-state PERG responses provide new and early specific information in neuro-ophthalmic diseases affecting the inner retina.

Summary:

Steady state PERG presents specific amplitude and latency outcomes based on the neuro-ophthalmic disease affecting the inner retina, allowing early recognition of changes at the level of RGC and the degree of RGC dysfunction. In addition, PERG alterations may be induced in healthy subjects as well as susceptible eyes using different stress tests such as head down tilting or water drinking tests.

Keywords: Retinal ganglion cell function, Non-arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION), Multiple sclerosis, Optic Neuritis, Glaucoma, Steady state PERG

INTRODUCTION:

The pattern electroretinogram (PERG) consists of a visual patterned stimulus (stripes or checkboards) displayed on a LED monitor that generates a retinal biopotential response. Different from the standard ERG which its response is mainly generated by the outer retina (photoreceptors and bipolar cells), PERG focuses mainly on the function of retinal ganglion cells (RGC) and its response is abolished when RGCs are degenerated. Historically PERG has been used to evaluate and monitor RGC function [1, 2]. Hence, PERG may be a useful tool when monitoring or evaluating neuro-ophthalmic diseases [3]. Previous PERG studies usually follow standard guidelines that use transient PERG recordings that consist of slow temporal frequency (< 3 reversals/s) and produces a small initial negative component with a peak time around 35 ms (N35), followed by a much larger positive component around 45 to 60 ms (P50), this positive component is finally followed by a larger negative component at 90–100 ms (N95) [4]. The evidence indicates that N95 is thought to have a greater effect on ganglion cell damage than P50 [5]. In this review we want to expand on the latest findings using the steady-state PERG that consist of 16 reversals/s and provides a higher amplitude and an improved latency response [** 6, 4].

In the inner neural retina, previous studies have reported that according to the type of disease, the damage might be selective for certain types of cells. Those studies state that acute, inflammatory damage affects mainly the parvocellular ganglion cells, meanwhile, chronic damage, is most likely to affect magnocellular ganglion cells [**7, **6, 8],[9, 10, 8, 11]. Based on this previous statement, the PERG can manifest specific change inresponse before OCT or visual field damage can be evidenced. In addition, steady-state PERG allows to measure RGCs amplitude decrease over time which is a physiological condition that presents as a slow adaptive change response (adaptation). In different optic nerve pathologies the slow adaptive change response is limited and could represent a novel source of information on RGC function [12, 13],[14],[ **7]. Our goal is to present the steady state PERG amplitude and latency response and its changesin different diseases that affect the RGCs such as glaucoma, non-arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy(NAION), multiple sclerosis and optic neuritis.

Steady state PERG Method

The steady state PERG method used by our institution uses a LED monitor that permits the use of a higher luminance and projects a synchronous pattern reversal. For an alternation of 16 reversals/s a sinusoidal like waveform is generated whose periods correspond to the reversal frequency. Steady-state PERG has been considered to be more sensitive to RGC dysfunction compared to transient PERG [15, 16, **6].

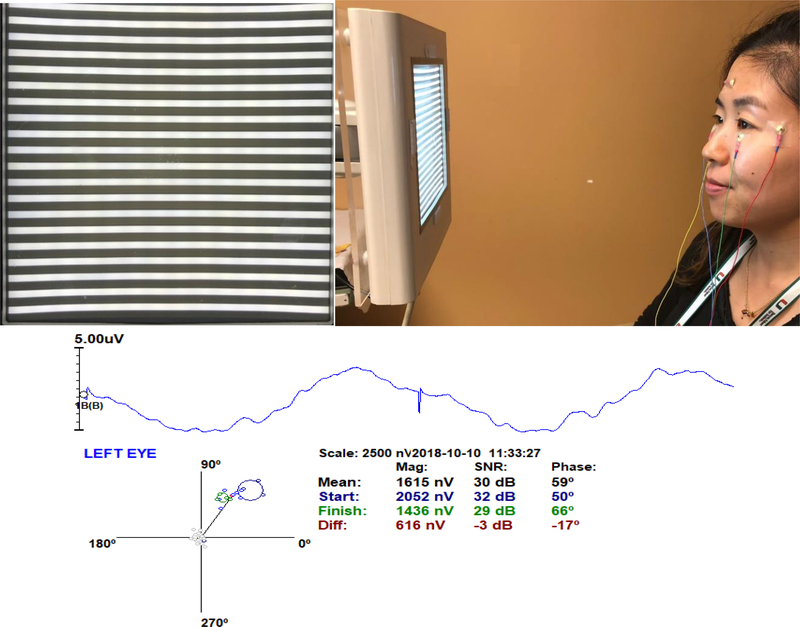

In brief the steady-state PERG method visual stimulus consists of a contrast reversing pattern displayed on a 14 × 14 cm LED monitor at 15.63 reversals/s, 98% contrast, 800 cd/m2 mean luminance, presented at 30 cm viewing distance in a dimly lit room.Subjects looked at the center of the screen with non dilated pupils and wore corrected lenses in order to achieve Jaeger J1+ visual acuity. Steady-state PERG signals were recorded from gold cup skin electrodes taped to the lower eyelids, temples and forehead, and averaged in sync with the pattern reversal over 1024 sweeps, the recording time lasted around 2 min. These sweeps were divided into 16 blocks by averaging 64 sweeps per block and were analyzed for adaptation (progressive change over time) [**7]. Sweeps contaminated by blinking artifacts were automatically rejected. Figure 1 shows the setup for the PERG recording with its corresponding PERG waveform, polar plot, amplitude and phase values.

Figure 1:

PERG method set up: A.) LED monitor displaying a horizontal grating (98% contrast, 800 cd/m2, 14 × 14 cm size). For PERG recording, the grating reversed 15.63 times/s. B.) Signals were acquired using gold skin electrodes placed on the lower eyelids, temples and forehead. During the 2 minute recording, subjects were allowed to blink freely with undilated pupils. C.) Polar plot representing combined amplitude and phase samples (Blue-Green circles) and noise samples (Grey circles). The amplitude is represented by the length of the vector connecting the origin of the axes with the cluster centroid (red circle). The blue circles represent the first 4 blocks of the recording and the green circles represent the last four blocks. Next to the polar plot represented in columns are the mean values for the amplitude, signal to noise ratio (SNR) and phase. The numbers in black represent the average of the 16 blocks for amplitude, SNR and phase. The numbers in blue color represent the average of the first four blocks and the numbers in green color represents the average of the last four blocks. Values in red represent the difference between the average of the first four and the last four samples. The average phase is represented by the angle between the average phase and the x axis and it can be transformed to latency in milliseconds by the following formula: (Latency= ((Phase° * 64ms)/360°) – 64). In the case above a phase of 59° equals 53.5 ms. When the angle decreases the latency increases.

Pattern electroretinogram in NAION

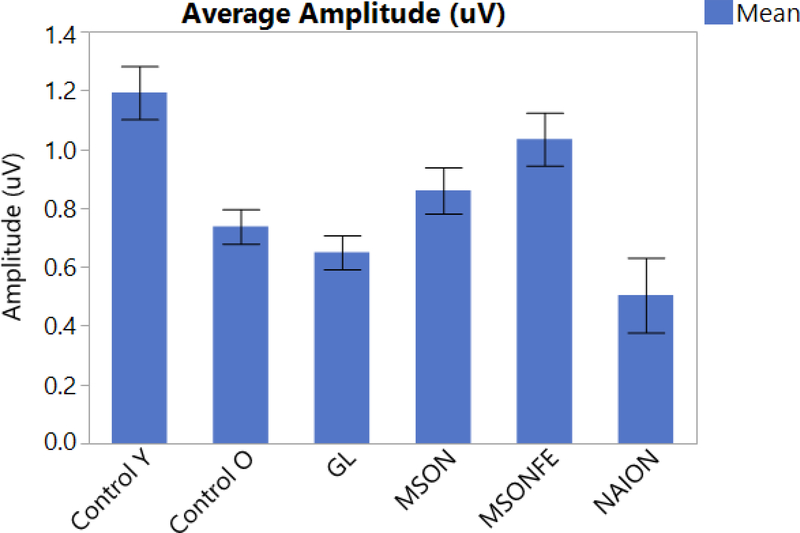

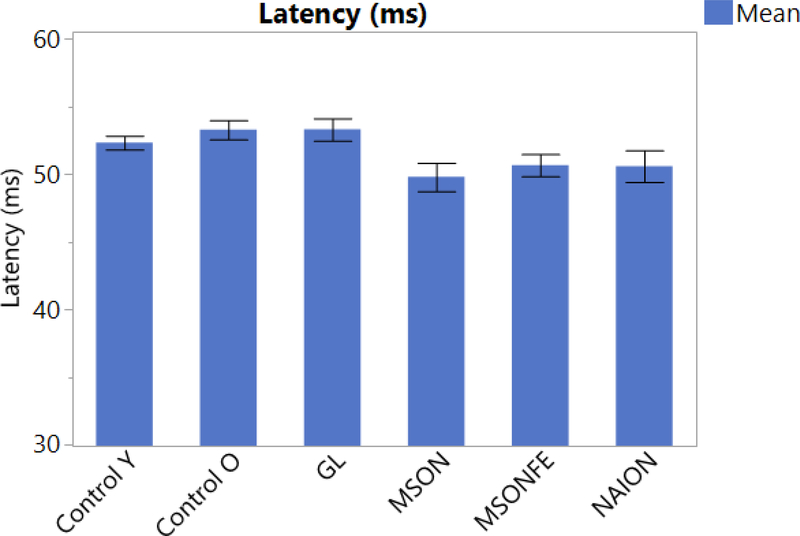

NAION is the most common acute optic neuropathy [17]. It is characterized by sudden vision loss, papillary edema and papillary hemorrhage. Currently, structural and functional damage due to NAION is measured and monitored through OCT or angiographic OCT imaging and visual field tests. In spite of being the most common acute optic neuropathy, only a small number of subjects develop NAION which is why the data involving PERG is limited. Transient PERG has been used on previous studies for the evaluation of NAION. Parisi et al performed a study on 20 patients (mean age: 63.7 ± 5.96 years), logMAR VA 0.040 ± 0.05 with NAION and compared it to 20 age-matched controls (mean age: 62.8 ± 6.54), logMAR VA 0.565 ± 0.16. A reduced amplitude and a delay in latency for P50 and P50 + N95 compared to controls was found [18]. More recent studies involving steady state PERG performed on 5 patients diagnosed with NAION (mean age: 59.4 ± 8.6), were compared to 11 age matched controls (mean age: 57.9 ± 8.09). A significant decrease in amplitude and a significant shortening in latency compared to healthy controls were found (p<0.001). Figure 2 and 3 [**6] This findings suggest that in NAION a shortening in latency corresponds to a more pronounced damage of the parvocells compared to magnocells.

Figure 2:

PERG amplitude shows significantly different responses between different diseases (bars). Steady-state PERG amplitude in eyes of control subjects, patients with history of multiple sclerosis and recovered unilateral optic neuritis, multiple sclerosis fellow eye, patients diagnosed with early manifest glaucoma and Non-arteritic optic neuropathy. (Control eyes, MSON: eyes with recovered unilateral optic neuritis, MSONFE: fellow eyes without history of optic neuritis, EMG: Early manifest glaucoma and NAION: Non-arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy). Bars represent the group means and corresponding SE.

Figure 3:

PERG latency compared between different diseases (bars). Steady-state PERG latency in eyes of control subjects, patients with history of multiple sclerosis and recovered unilateral optic neuritis, multiple sclerosis fellow eye, patients diagnosed with early manifest glaucoma and Non-arteritic optic neuropathy. (Control eyes, MSON: eyes with recovered unilateral optic neuritis, MSONFE: fellow eyes without history of optic neuritis, EMG: Early manifest glaucoma and NAION: Non-arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy). Bars represent the group means and corresponding SE.

PERG in MS/Optic Neuritis

Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune demyelinating disease that affects different areas of the central nervous system [22, 23]. It has been characterized by a chronic axonal damage and might present with an acute episode of optic neuritis [24]. Up to 75% of patients with multiple sclerosis will have an acute episode of optic neuritis [25]. Multiple studies have focused on RNFL sectorial thickness in order to characterize the progression of optic neuritis vs. the fellow eye [25–27].It has been shown that eyes with multiple sclerosis and optic neuritis present a global decrease in thickness but more pronounced on the temporal sectors compared to aged match controls and the fellow eyes [28, 29, 26]. Previous studies involving PERG applied to multiple sclerosis have mainly used transient PERG. Janaky et al, recruited 85 patients (mean age: 35.8 range 19 – 45), 38 patients had a history of optic neuritis and were compared to 47 subjects with no history of optic neuritis. These results were compared to 47 healthy controls (mean age: 35.5 range 18 – 48). A significant decrease in amplitude for P50 + N95 was found (p< 0.008) [34]. Rodriguez Mena et al, studied 114 subjects, 57 MS patients (mean age: 42.28 ± 11.12) and 57 controls (mean age: 43.32 ± 13.59) and found mainly a delay in latency for N95 (p=0.012) and a significant difference between N95/P50 amplitude ratio (p=0.001) [35]. Hokazono et al, studied 28 patients, 51 eyes with MS, 29 eyes with a history of optic neuritis and 22 eyes without ON (mean age: 36.75 ± 11.45), VA: 20/20 (20/16 – 20/200) and compared it to 26 controls subjects, 30 eyes (mean age: 36.0 ± 12.5), VA: 20/20 (20/16 – 20/25) and have described a reduced amplitude for N95 (p <0.0001) and P50+N95 (p= 0.001) [36]. Fraser et al, studied 46 patients (mean age: 45 range 23– 68) and found a significantly lower N95 amplitude in eyes affected with optic neuritis (p<0.001) [37]. Parisi et al, studied 14 patients with MS with a complete recovery of optic neuritis (mean age: 34.1 ± 5.8) and were compared to 14 age-matched controls subjects and found a delayed latency for P50 and a reduced amplitude for N35 - P50 and P50 - N95 (p<0.001) [38]. Most studies involving transient PERG found a decrease in amplitude and delay in latency.

Falsini et al, performed a study involving steady state PERG and found a decrease in amplitude and a delay in latency in patients with a history of optic neuritis compared to controls [39, 40]. A most recent study involving steady-state PERG, 17 patients with a diagnosis of MS and a history of recovered optic neuritis, its fellow eye (mean age: 43 ± 9.43) were compared to age matched controls (mean age: 42 ± 12.69). No significant difference in amplitude was found between controls, patients with multiple sclerosis with a history of optic neuritis and its fellow eyes (p>0.23). Interestingly a significant shortening in latency was found between patients with multiple sclerosis and a history of optic neuritis compared to controls (p<0.0001), as well as the fellow eyes compared to controls (p<0.05) Figure 2 and 3 [**41].

PERG in glaucoma

Glaucoma is the most common chronic optic neuropathy and most common cause of blindness in developed countries [30]. Due to its nature, structural damage has been reported with OCT, retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and ganglion cell inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) thickness measurements. It has been previously reported that patients with normal tension glaucoma have shown an increase in PERG amplitude after treatment, implying that cells undergo a dysfunctional phase before they are taken out of the cell pool [30, 31],[32], [33]. PERG has been reported to be a useful tool for detecting glaucoma before visual field or structural changes occur [42], [32]. Hood et al, used transient PERG to study 15 patients (mean age: 58 range: 31–77) with a diagnosis of glaucoma compared to 16 control subjects (mean age: 44 range, 26 – 65) which showed a decrease in N95 on patients with glaucoma compared to healthy controls.Nevertheless 6 eyes (25%) that met the criteria for glaucoma with an increased cup to disc ratio and visual field defect did show a normal PERG response [5]. Porciatti et al, recorded steady-state PERGs on 200 glaucoma suspects (GS) and 42 early manifest glaucoma (EMG) patients (mean age: 57 ± 13) and 114 normal subjects (mean age: 46.4 ± 18.2), which showed a decrease in amplitude on GS and EMG patients. A more significant decrease was seen on patients with lower visual field mean deviations and increased cup to disc ratio [43]. Bode et al, performed steady state PERG in 64 patients (120 eyes) with high risk ocular hypertension (OHT) and followed them for a period of 10.3 years. Thirteen eyes converted to glaucoma based on strict visual field definition. Steady state PERG showed a significant decrease in amplitude in converters compared to non-converters (p<0.001) [44].

More recent studies have applied stress tests in order to trigger reversible RGC dysfunction such as the head down tilting test [45]. Porciatti et al, studied 28 glaucoma suspects (GS) (mean age: 58 ± 8.9) and followed them for 5 years and compared them to 11 similar-age controls (SAC) (mean age: 56.9 ± 13). From the GS cohort, 9 patients had a retinal nerve fiber layer thinning greater than 5.4 μm and where classified as thinners “T” while the rest were classified as non-thinners “NT”. The study found non-significant difference between groups on seated position (p = 0.08). In the tilted position however, there was a significant (p=0.0025) difference between groups (SAC>NT p=0.001; SAC>T, p= 0.0075). Monsalve et al, performed steady state PERG in 7 EMG patients (mean age: 59.4 ± 8.6) and compared to 11 age matched controls (mean age: 65.7 ± 11.6) finding aa significant difference in amplitude (p<0.001) but a non-significant difference in latency (p>0.05) Figure 2 and 3 [6]. In addition Gameiro et al, performed a different stress test known as water drinking test (WDT), on 16 healthy subjects (mean age: 33.5 ± 7.9) which consists on drinking 1 liter of water at room temperature within a period of 5 minutes. Blood pressure, heart rate, intraocular pressure, steady state PERG amplitude and latency were assessed before the test and every 15 minutes over a period of 1 hour. The same protocol was performed on the same cohort without WDT. The main study finding was a significant delay in latency at 15 minutes that slowly recovered at 60 minutes (p<0.002).

Adaptation applied on clinical findings:

Findings in healthy patients:

Adaptation, a new parameter useful for RGC function assessment has been measured using steady state PERG. Porciatti et al, recorded 14 healthy subjects for 4 minutes looking at a contrast reversing (16.28/s) patterns with different contrast (12%−99%) and mean luminance (40 −1.3cd/m2) where the temporal period of the stimulus (122.8 ms) was sampled and averaged in packets of 50 sweeps (15 seconds each). Data was fitted with an exponential decay function to evaluate PERG change over time (Adaptation). This study found that the peak PERG amplitude was significantly larger than the plateau amplitude at 99% contrast and all luminances (t-test p<0.001, ANOVA p<0.001 respectively) (52). On a different study 32 healthy subjects (mean age: 41.7 ± 16), best corrected Snellen VA 20/20 or better were recorded using steady state PERG. Delta amplitude was calculated by the difference between the initial and the final amplitude. This study found that the higher the initial amplitude values, the deltas showed a negative sign, indicating amplitude decline. The magnitude of delta progressively decreased with decreasing initial amplitude. The correlation between delta and initial amplitude was very strong (R2 = 0.68, p =<0.001) [12, 13].

Findings in patients with optic nerve diseases:

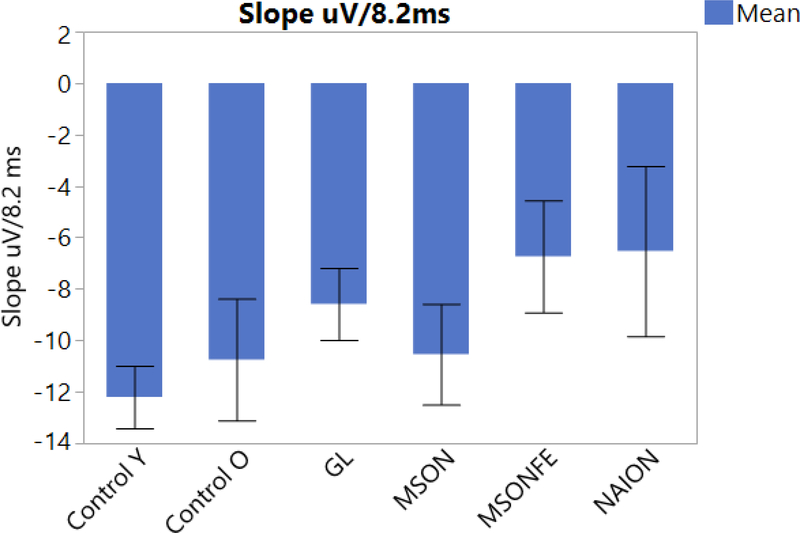

Fadda et al, recorded 14 patients with a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (mean age: 37.1 ± 12.0) and 8 normal subjects (mean age: 40.2 ± 11.8), with 20/20 or better Snellen visual acuity using steady-state PERG, and found that the mean delta amplitude for normal subjects was significantly different from the delta amplitude for MS patients (p=0.003) [46]. Monsalve et al, studied 10 young healthy subjects (mean age: 38 ± 8.3), 11 older controls (mean age: 57.9 ± 8.09), 7 patients with EMG (mean age: 65.7 ±11.6), and 5 patients with NAION (Mean age: 59.4 ±8.6). The slope of the linear regression was calculated; a univariate ANOVA on amplitude slopes showed a strong group effect (p=0.0036), with steeper negative slopes occurring in younger controls and the shallower negative slopes occurring with NAION patients. Figure 4 [**6]. Clinically, lack of adaptation may suggests that RGCs are not able to autoregulate the increased metabolic demand provided by the pattern stimulus.

Figure 4:

PERG adaptation slope bars for each disease. Steady-state PERG measuring amplitude decrease over time (Adaptation) in eyes of control subjects, patients with history of multiple sclerosis and recovered unilateral optic neuritis, multiple sclerosis fellow eye, patients diagnosed with early manifest glaucoma and Non-arteritic optic neuropathy. (Control eyes, MSON: eyes with recovered unilateral optic neuritis, MSONFE: fellow eyes without history of optic neuritis, EMG: Early manifest glaucoma and NAION: Non-arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy). Bars represent the group means and corresponding SE.

Discussion:

Functional assessment of RGC are mostly focused on visual field tests, or visual evoked potentials based on the type of neuro-ophthalmological disease. The steady state PERG is a functional test that aids in the clinical evaluation and monitoring of RGC function on different neuro-ophthalmic diseases.

Depending on the type and duration of injury affecting the inner retina, a shortening or delay in latency, as well as a decrease in amplitude, might be present. It has been previously hypothesized that an acute injury to the inner retina will affect the parvocells, in contrast to a chronic damage to the inner retina that will affect mostly the magnocells [**7, **6, 8],[9, 10, 8, 11].

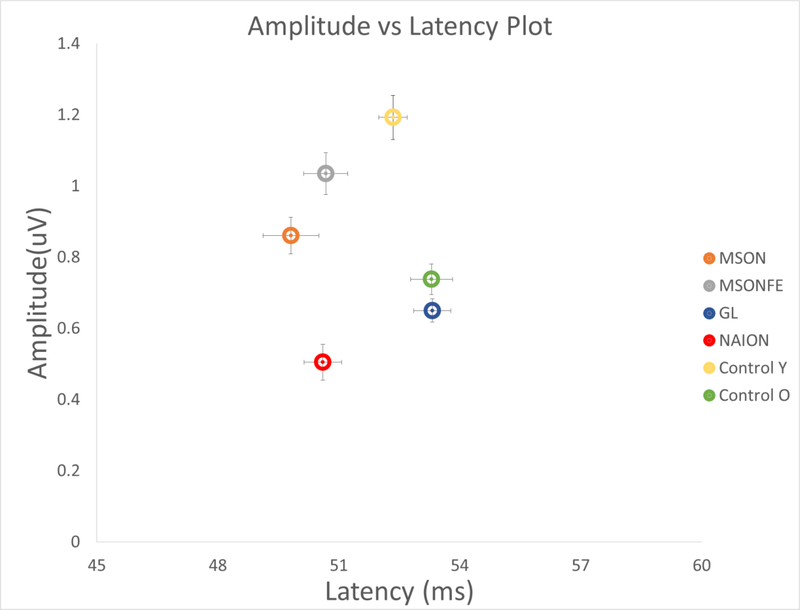

Chronic diseases such as glaucoma, tend to affect mainly the magnocells. [49, 50]. On those subjects, steady state PERG has shown a significant reduction in amplitude but a similar delay in latency compared to older subjects. This could be explained by the fact that magnocells have the ability to discriminate lower spatial frequency needing less time to process information (Figure 2, 3 and 5). On the other hand, acute diseases such as recovered optic neuritis, affect mainly the parvocells. Our study found that amplitude response was similar to young age matched controls, but with a significant shortening in latency. These findings suggests that parvocellular RGCs mainly discriminate higher spatial frequency, and need an increased amount of time to process information. [51, 45, 10].

Figure 5:

Amplitude vs. Latency plot showing amplitude and latency combined for all diseases. Steady-state PERG amplitude/latency plot in eyes of control subjects, patients with history of multiple sclerosis and recovered unilateral optic neuritis, multiple sclerosis fellow eye, patients diagnosed with early manifest glaucoma and Non-arteritic optic neuropathy. (Control eyes younger (Yellow circle), Older (Green circle), MSON: eyes with recovered unilateral optic neuritis (Orange circle), MSONFE: fellow eyes without history of optic neuritis (Grey circle), EMG: Glaucoma (Blue circle) and NAION: Non-arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy (Red circle). Circles represent the amplitude and latency combined in a plot representation group and its corresponding bidirectional error bars. Different neuro-ophthalmic diseases present with different amplitude and latency response.

Previous studies have also described retinal ganglion cell adaptation when the steady state PERG was recorded, over an increased period of time [12, 13, 46, 14, **7]. As described above, our steady state PERG method, allows us to measure adaptation on a recording performed on a shorter period of time(Figure 4). In healthy subjects, adaptation gradually decreases over time. In different diseases as the ones described above PERG adaptation might be largely limited due to the lack of autoregulation from the retinal ganglion cells[13].

Finally, PERG presents with a specific response for amplitude and latency based on the age of the subjects and the disease being evaluated. [47, 48]. As shown in Figure 5, a significant difference in amplitude and latency between young controls compared to old controls is seen. In addition, old controls present a similar latency compared to patients with glaucoma but with a significantly different amplitude response. In contrast, in younger subjects the amplitude response compared to multiple sclerosis subjects with recovered optic neuritis and its fellow eye was similar, yet the latency in patients with multiple sclerosis and recovered optice neuritis was significantly shortened.

Conclusion:

Steady-state PERG has a characteristic response based on the type of disease being tested making it a useful tool to differentiate between different disease processes in the optic nerve. It also allows to evaluate and monitor different neuro-ophthalmological diseases, including early detection of functional abnormalities prior to the development of permanent structural damage. If subjects present a normal PERG response or an improvement on amplitude and latency on follow up, the clinician can be confident that the RGCs are still functional or have recovered from a previous dysfunctional state.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Supported by NIH Center Core Grant R43EY023460 and Research to Prevent Blindness Unrestricted Grant

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Pedro Monsalve declare that he has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References:

- 1.Porciatti V Electrophysiological assessment of retinal ganglion cell function. Exp Eye Res. 2015;141:164–70. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porciatti V, Ventura LM. The PERG as a Tool for Early Detection and Monitoring of Glaucoma. Current Ophthalmology Reports. 2017;5(1):7–13. doi: 10.1007/s40135-017-0128-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holder GE. Pattern electroretinography (PERG) and an integrated approach to visual pathway diagnosis. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20(4):531–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bach M, Brigell MG, Hawlina M, Holder GE, Johnson MA, McCulloch DL et al. ISCEV standard for clinical pattern electroretinography (PERG): 2012 update. Doc Ophthalmol. 2013;126(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10633-012-9353-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hood DC, Xu L, Thienprasiddhi P, Greenstein VC, Odel JG, Grippo TM et al. The pattern electroretinogram in glaucoma patients with confirmed visual field deficits. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2005;46(7):2411–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monsalve P, Triolo G, Toft-Nielsen J, Bohorquez J, Henderson AD, Delgado R et al. Next Generation PERG Method: Expanding the Response Dynamic Range and Capturing Response Adaptation. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2017;6(3):5. doi: 10.1167/tvst.6.3.5.** This study compares the new steady state PERG method to a previously validated PERG method.

- 7.Monsalve P, Ren S, Triolo G, Vazquez L, Henderson AD, Kostic M et al. Steady-state PERG adaptation: a conspicuous component of response variability with clinical significance. Doc Ophthalmol. 2018;136(3):157–64. doi: 10.1007/s10633-018-9633-2.** This study describes the within test variability of the steady state PERG reponse and describes its significant physiological and clinical implications

- 8.Porciatti V, Sartucci F. Retinal and cortical evoked responses to chromatic contrast stimuli. Specific losses in both eyes of patients with multiple sclerosis and unilateral optic neuritis. Brain. 1996;119 ( Pt 3):723–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jansonius NM, Kooijman AC. The effect of defocus on edge contrast sensitivity. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1997;17(2):128–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Digre KB. Evangelou N, Konz D, Esiri MM, et al. Size-selective neuronal changes in the anterior optic pathways suggest a differential susceptibility to injury in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2002;22(2):143. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200206000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centofanti M, Fogagnolo P, Oddone F, Orzalesi N, Vetrugno M, Manni G et al. Learning effect of humphrey matrix frequency doubling technology perimetry in patients with ocular hypertension. Journal of glaucoma. 2008;17(6):436–41. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31815f531d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porciatti V, Sorokac N, Buchser W. Habituation of retinal ganglion cell activity in response to steady state pattern visual stimuli in normal subjects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(4):1296–302. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porciatti V, Ventura LM. Adaptive changes of inner retina function in response to sustained pattern stimulation. Vision Res. 2009;49(5):505–13. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porciatti V, Bosse B, Parekh PK, Shif OA, Feuer WJ, Ventura LM. Adaptation of the steady-state PERG in early glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2014;23(8):494–500. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e318285fd95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bach M Electrophysiological approaches for early detection of glaucoma. European journal of ophthalmology. 2001;11 Suppl 2:S41–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trick GL. Retinal potentials in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma: physiological evidence for temporal frequency tuning deficits. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 1985;26(12):1750–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hattenhauer MG, Leavitt JA, Hodge DO, Grill R, Gray DT. Incidence of Nonarteritic Anteripr Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123(1):103–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70999-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parisi V, Gallinaro G, Ziccardi L, Coppola G. Electrophysiological assessment of visual function in patients with non-arteritic ischaemic optic neuropathy. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(8):839–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Froehlich J, Kaufman DI. Use of pattern electroretinography to differentiate acute optic neuritis from acute anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;92(6):480–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janaky M, Fulop Z, Palffy A, Benedek K, Benedek G. Electrophysiological findings in patients with nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy☆. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117(5):1158–66. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atilla H, Tekeli O, Örnek K, Batioglu F, Elhan AH, Eryilmaz T. Pattern electroretinography and visual evoked potentials in optic nerve diseases. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13(1):55–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kidd DP, Plant GT. Chapter 6 Optic Neuritis. Blue Books of Neurology. 2008. p. 134–52.

- 23.Plant GT. Optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21(1):16–21. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282f419ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petzold A, Wattjes MP, Costello F, Flores-Rivera J, Fraser CL, Fujihara K et al. The investigation of acute optic neuritis: a review and proposed protocol. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(8):447–58. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szilasiová J, Klímová E, Veselá D. [Optic neuritis as the first sign of multiple sclerosis]. Cesk Slov Oftalmol. 2002;58(4):259–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lizrova Preiningerova J, Grishko A, Sobisek L, Andelova M, Benova B, Kucerova K et al. Do eyes with and without optic neuritis in multiple sclerosis age equally? Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:2281–5. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S169638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hokazono K, Raza AS, Oyamada MK, Hood DC, Monteiro MLR. Pattern electroretinogram in neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis with or without optic neuritis and its correlation with FD-OCT and perimetry. Doc Ophthalmol. 2013;127(3):201–15. doi: 10.1007/s10633-013-9401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klistorner A, Sriram P, Vootakuru N, Wang C, Barnett MH, Garrick R et al. Axonal loss of retinal neurons in multiple sclerosis associated with optic radiation lesions. Neurology. 2014;82(24):2165–72. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akçam HT, Capraz IY, Aktas Z, Batur Caglayan HZ, Ozhan Oktar S, Hasanreisoglu M et al. Multiple sclerosis and optic nerve: an analysis of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and color Doppler imaging parameters. Eye. 2014;28(10):1206–11. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(3):262–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Porciatti V, Ventura LM. Retinal ganglion cell functional plasticity and optic neuropathy: a comprehensive model. J Neuroophthalmol. 2012;32(4):354–8. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e3182745600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banitt MR, Ventura LM, Feuer WJ, Savatovsky E, Luna G, Shif O et al. Progressive loss of retinal ganglion cell function precedes structural loss by several years in glaucoma suspects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(3):2346–52. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karaśkiewicz J, Drobek-Słowik M, Lubiński W. Pattern electroretinogram (PERG) in the early diagnosis of normal-tension preperimetric glaucoma: a case report. Doc Ophthalmol. 2013;128(1):53–8. doi: 10.1007/s10633-013-9414-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janaky M, Janossy A, Horvath G, Benedek G, Braunitzer G. VEP and PERG in patients with multiple sclerosis, with and without a history of optic neuritis. Documenta ophthalmologica Advances in ophthalmology. 2017;134(3):185–93. doi: 10.1007/s10633-017-9589-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez-Mena D, Almarcegui C, Dolz I, Herrero R, Bambo MP, Fernandez J et al. Electropysiologic evaluation of the visual pathway in patients with multiple sclerosis. Journal of clinical neurophysiology : official publication of the American Electroencephalographic Society. 2013;30(4):376–81. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e31829d75f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hokazono K, Raza AS, Oyamada MK, Hood DC, Monteiro ML. Pattern electroretinogram in neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis with or without optic neuritis and its correlation with FD-OCT and perimetry. Documenta ophthalmologica Advances in ophthalmology. 2013;127(3):201–15. doi: 10.1007/s10633-013-9401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fraser CL, Holder GE. Electroretinogram findings in unilateral optic neuritis. Documenta ophthalmologica Advances in ophthalmology. 2011;123(3):173–8. doi: 10.1007/s10633-011-9294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parisi V, Manni G, Spadaro M, Colacino G, Restuccia R, Marchi S et al. Correlation between morphological and functional retinal impairment in multiple sclerosis patients. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 1999;40(11):2520–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Falsini B, Porrello G, Porciatti V, Fadda A, Salgarello T, Piccardi M. The spatial tuning of steady state pattern electroretinogram in multiple sclerosis. European journal of neurology. 1999;6(2):151–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Falsini B, Porciatti V. The temporal frequency response function of pattern ERG and VEP: changes in optic neuritis. Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology. 1996;100(5):428–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monsalve P, Ren S, Jiang H, Wang J, Kostic M, Gordon P et al. Retinal ganglion cell function in recovered optic neuritis: Faster is not better. Clin Neurophysiol. 2018;129(9):1813–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2018.06.012.** This study describes the steady state PERG response in patients with multiple sclerosis and recovered optice neuritis.

- 42.Bach M, Hoffmann MB. Update on the pattern electroretinogram in glaucoma. Optometry and vision science : official publication of the American Academy of Optometry. 2008;85(6):386–95. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318177ebf3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ventura LM, Porciatti V, Ishida K, Feuer WJ, Parrish RK 2nd. Pattern electroretinogram abnormality and glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(1):10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bode SF, Jehle T, Bach M. Pattern electroretinogram in glaucoma suspects: new findings from a longitudinal study. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2011;52(7):4300–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Porciatti V, Feuer WJ, Monsalve P, Triolo G, Vazquez L, McSoley J et al. Head-down Posture in Glaucoma Suspects Induces Changes in IOP, Systemic Pressure, and PERG That Predict Future Loss of Optic Nerve Tissue. Journal of glaucoma. 2017;26(5):459–65. doi: 10.1097/ijg.0000000000000648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fadda A, Di Renzo A, Martelli F, Marangoni D, Batocchi AP, Giannini D et al. Reduced habituation of the retinal ganglion cell response to sustained pattern stimulation in multiple sclerosis patients. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2013;124(8):1652–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trick GL, Nesher R, Cooper DG, Shields SM. The human pattern ERG: alteration of response properties with aging. Optometry and vision science : official publication of the American Academy of Optometry. 1992;69(2):122–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Porciatti V, Burr DC, Morrone MC, Fiorentini A. The effects of aging on the pattern electroretinogram and visual evoked potential in humans. Vision research. 1992;32(7):1199–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yücel YH. Loss of Neurons in Magnocellular and Parvocellular Layers of the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus in Glaucoma. Arch Ophthal. 2000;118(3):378. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.La Morgia C, Di Vito L, Carelli V, Carbonelli M. Patterns of Retinal Ganglion Cell Damage in Neurodegenerative Disorders: Parvocellular vs Magnocellular Degeneration in Optical Coherence Tomography Studies. Front Neurol. 2017;8. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gameiro G, Monsalve P, Golubev I, Ventura L, Porciatti V. Neurovascular Changes Associated With the Water Drinking Test. J Glaucoma. 2018;27(5):429–32. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]