Abstract

Given the pace of social changes, meanings of “family” and what makes a family healthy are changing. How can these changing meanings and understandings contribute to social justice for all families? First, I acknowledge how my personal history has intersected with research I do on youth and families. I define social justice with respect to healthy families, and then consider how contemporary scholarship helps define, redefine, and refine what is meant by “family.” Examples are presented from research on cultural influences on parenting; parenting in same-sex couple or lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ) families; and coming out in adolescence as LGBTQ. These examples illustrate how the notion of family is defined, redefined, and refined to provide new vantage points on the complexities, possibilities, and potential for social justice among contemporary families, especially those that are marginalized.

Keywords: Families, health, LGBTQ, parenting, social justice

What is the future of healthy families? In the context of today’s extraordinary social changes, how can the future for families and what will keep them healthy be understood and anticipated? These are generative questions—prompting questions—that not only reach forward but also look back to understand the changing nature of family life and the changing meanings of health for families. First, I ground my responses to these questions in my personal experience, acknowledging how it intersects with my research on families and thus shapes my response to these questions. Next, social justice is defined with respect to healthy families, and with this background, ways that contemporary scholarship defines, redefines, and refines the meaning of “family” are considered, focusing on cultural influences on parenting, and on parenting in same-sex couple or lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) families in particular. Finally, research on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth and their families is used to illustrate and document contemporary changes in family relationships and healthy families. Together this scholarship is used as grounding for an analysis of healthy families, human rights, and social justice.

Personal History and Family Scholarship

During my postdoctoral studies, I worked with Glenn H. Elder, Jr. and Rand D. Conger on a study of families in changing times, considering connections across generations to family land and farming in central Iowa during the farm crisis of the 1980s, which was a period of unprecedented economic change for rural families in the United States (Elder & Conger et al., 2000). I also began using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (the Add Health Study), which was being conducted at the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill where I was a postdoctoral scholar. With these data I began some of the first studies of adolescent sexual orientation and health, using national representative data (Russell, Franz, & Driscoll, 2001; Russell & Joyner, 2001; Russell, Seif, & Truong, 2001; Russell, Truong, & Driscoll, 2002), as well as research on cultural differences in parenting practices and parent–adolescent relationships (Crockett, Brown, Russell, & Shen, 2007; Crockett, Randall, Shen, Russell, & Driscoll, 2005; Driscoll, Russell, & Crockett, 2008). Several years later, I received an early-career training grant from the William T. Grant Foundation that encouraged me to train in qualitative methods and approaches that would advance my training as a sociologist and demographer, which extended my scholarship in studies of adolescent sexual orientation as well as of cultural differences in parent–adolescent relationships. From 2004 to 2015, I lived in Southern Arizona near the Mexican border during the 49th Arizona Legislature and the infamous anti-immigration legislation (SB 1070) of 2010 and was conducting community-based research with young people on the intersections of immigration, racial justice, sexuality, health, and rights (see Fields, Snapp, Russell, Licona, & Tilley, 2014; Licona & Russell, 2013).

In the early 1990s, I came out as gay while a doctoral student and was involved in LGB (before it was LGBTQ) activism. At that time, being out and gay was understood as risky in the academy (and depending on the setting, it still is). In 2009, still living in Arizona, I became a parent to an undocumented Mexican-origin, gay 13-year-old boy, the same year that the state legislature passed SB 1070. Looking back now, I see that the historical and political contexts of the past decades have intersected with my personal and academic life in ways that have shaped my values and approach to the study of families. It is in this historical, political, geographic, cultural, and personal context that I had been writing about cultural differences in parent–adolescent relationships and LGBTQ adolescent health and development, all of which have informed my thinking about the future of healthy families.

Social Change, Social Justice, and Contemporary Families

In thinking about the future of healthy families, I begin with a broad goal: That the field of family science will value and prioritize research that is useful for promoting social change in service of social justice for families (Russell, 2015). I define social justice as the ability of people and families to realize their potential for health and thriving in the context of the society in which they live. In simple terms, this means that families (and the individuals in them) will have the potential to become the best version of themselves that they can possibly be. Social justice is manifest when families have opportunities to maximize their health and happiness across the life span. Social justice is therefore contingent on the character of society in terms of its political, economic, social, and cultural milieu and history (Russell, 2015, 2016).

Across time and cultures, social stratification has fundamentally characterized societies. Stratification and inequalities have taken multiple forms across historical time, place, and culture, but in contemporary terms, they have to do with gender, race, class, ethnicity, religion, sexuality, and the other things that make up who we are as people. Personal characteristics and statuses—the identities that give our lives meaning—become the vectors of the equality that operates in our lives, and directly impact the full range of dimensions of health. Thus, matters of social justice are defined by inequalities, and therefore by human health and rights. Inequalities play out at multiple interacting levels: the interpersonal, social, cultural, and policy levels. The social change to which I refer has to deal with directly identifying, challenging, and dismantling the multiple and typically intersecting forms of social inequalities that define the realities of family lives today (Parke, 2013).

Re/De/fining Healthy Families

The very notion of “family” has been historically defined and situated and carries powerful cultural meanings that often are unquestioned (Parke, 2013). Yet much of the terrain of the contemporary dominant public discourse on families is based on romanticized and historically unique understandings of family as a construct. Coontz (1993) importantly called attention to “the way we never were” by pointing out that several cultural beliefs about the idea of family are actually myths. Ideas like “the American nuclear family” (i.e., two first-marriage parents and their biological children) became dominant for understanding U.S. family life (based on gender, race, and social class opportunities or constraints) in the period after World War II. Yet throughout Western literary history, there have been consistently identified forms of family that challenge this mid-20th-century stereotype of what constitutes a family. Consider the works of Jane Austen (e.g., Austen, 1817) or the Brontë sisters (e.g., A. Brontë, 1848; E. Brontë, 1847) and the complex, contested, and nonnormative relationships that defined and redefined families in their novels. If contemporary families are believed to be uniquely complex or complicated, or more diverse, a look to the past will show that families have always been complicated and changing. That is, “the family” is fundamentally complex, contested, and ever-changing in the context of historical times and cultures.

Looking to the future of healthy families therefore involves not only defining but also refining and redefining what we mean by family. In the sections that follow, I review findings from my own research and the work of others that have contributed to such refinement and redefinition of healthy families. I begin with studies of cultural group differences in the United States with regard to parenting processes in adolescence. This work was conducted during the same period as studies of parenting processes in adolescence, comparing youth who grew up with same-sex-coupled versus heterosexual parents (Wainright, Russell, & Patterson, 2004). I then turn to research on LGBTQ youth and their parents.

Cultural Differences in Parenting Processes

To illustrate lessons learned about healthy families from the study of cultural differences in parenting, I turn first to analyses that focused on the largest ethnic subgroups among Asian American (Chinese and Filipino) and Hispanic or Latino (Cuban, Mexican, and Puerto Rican) youth in the United States (Russell, Crockett, & Chao, 2010). The broad goal was to understand the meaning and quality of these adolescents’ relationships with their parents. This study was conducted when some scholars were arguing that the body of knowledge on parenting in adolescence had yielded consistent understandings of parenting processes that applied across cultures (Steinberg, 2001), whereas other scholars were arguing that models of parenting were based on Western understandings of meanings of family and that things might work differently in families from different cultural groups (Chao, 1994). My collaborators and I questioned whether cultural group differences would be evident in parenting practices across diverse ethnic groups in a national study, and whether we could understand the meaning of those potential differences through in-depth qualitative analysis.

Several findings from this research project challenged mainstream understandings of parenting processes, which at that time were based predominantly on studies of Anglo families in North America (Russell, Crockett, & Chao, 2010). First, based on data from youth focus groups, we learned from both Asian American and Latino youth, for example, about the distinctiveness of adolescents’ expectations of parental control as a defining feature of “good relationships” (Crockett et al., 2007; Russell, Crockett, & Chao, 2010). That is, when we asked what made for a good relationship with parents, a common theme among Mexican American youth was that physical and verbal affection were not important or expected; their descriptions of what characterized good parental relationships was not what we expected based on typical understandings of high-quality parent–adolescent relationships (Crockett et al., 2007). Explicit verbal and physical affection were not expected by many of these Mexican American adolescents, and the same was true to a lesser degree for the Cuban American adolescents (Crockett, Brown, Iturbide, Russell, & Wilkinson-Lee, 2009). The Mexican American youth did not, for example, expect to be told that they were “good kids.” These findings challenged some of the ideas that are fundamental to given understandings of parental warmth and “good relationships” and, further, indicated that parental control was expected by these adolescents and understood as normal. The adolescents noted that “you know that your parents care” when they monitor or regulate the behavior of their children (Crockett et al., 2009). These characteristics—lack of explicit affection but the presence of monitoring—were the things that define a “good parent–child relationship” according to these Mexican American youth.

In focus groups with Asian American adolescents, we heard similar themes with respect to good relationships. For example, when asked to describe a good relationship with their mothers, the Filipina girls said (in effect), “I can’t have boyfriends, and I need to make good grades.” This theme came up consistently and as the first response to our question about the meaning of a great relationship with mothers (Russell, Chu, Crockett, & Doan, 2010). What they apparently were saying was that monitoring by parents is what makes a good relationship and what demonstrates care and love.

We also asked the youth in these studies about the notions of autonomy and independence: “Do you get to make your own decisions?” Nearly all the youth we spoke with said that they could make their own decisions, but notably, Asian American youth (both boys and girls, and Chinese and Filipino/a) consistently defined independence with reference to their relationships with their parents, and in contingent or interdependent terms. For girls, independence was based on mutually understood family roles, including the understanding that parents know what is best for their daughters and that girls should make decisions consistent with their parents’ wishes. For boys, autonomy was negotiated with parents or contingent on their approval. Drawing from studies of Asian cultural meanings regarding families (Chao, 1994) and Asian American parenting, we can understand the nature of parent–adolescent relationships as “interdependent independence” (Russell et al., 2010).

These findings refine and redefine the dominant core of our understanding of the meanings and qualities of “good” parent–adolescent relationships. Note that these were not comparative studies; we did not have similar data to compare other cultural perspectives with those of Anglo adolescents about the meaning of good relationships with parents or autonomy with respect to parents. Yet the meanings that emerged stand in contrast to dominant understandings of the classic models that frame parental warmth and control as distinct rather than overlapping or even complementary dimensions of parenting. However, it follows that the dominant Western body of knowledge on parenting also came from a culturally distinct group (i.e., Western Anglo, middle-class families living in 20th-century North America). This realization, in turn, provides an opportunity to refine and redefine core beliefs and models that scholars hold about family relationships and parenting that are rooted in a particular time and place. I am not suggesting that the historical models are necessarily wrong but rather that they may be informed—and constrained by (and thus biased toward)—Western Anglo family culture.

Thus, as Parke (2013) pointed out, examining basic family processes in underrepresented groups illuminates processes that may exist in all families but that we have not considered. Of course not all Anglo families are explicitly verbally or physically affectionate, and the absence of such displays of affection may not be a sign of poor relationships or neglect. And if asked, many Anglo adolescents also might understand monitoring by their parents as a sign of a “good relationship.” But such understandings are not incorporated into dominant models for understanding families and parenting (e.g., these themes are absent in contemporary discourses about positive teen–parent relationships in the United States). Thus, through the study of youth and families that have been historically underrepresented in Western scholarship, deep understandings can be gained among specific subgroups, but those new understandings can also help to refine existing theories and enhance discourse concerning the fundamental components and processes of healthy families.

Same-Sex Versus Heterosexual Parents and Adolescent Adjustment

For one study, my colleagues and I examined family differences in adolescent adjustment for adolescents growing up with same-sex coupled parents (Wainright et al., 2004). We were motivated by political debates about the suitability of gay and lesbian individuals and couples to be parents. One perspective in these debates was that only (married) heterosexual couples are suitable parents, and thus gays and lesbians would not be good parents and their children would be maladjusted. Another perspective was that, given the pervasive prejudice and discrimination against others’ sexual identities and lifestyles, same-sex parents and their children would experience discrimination, which could undermine parenting as well as youth well-being and adjustment. Most research on same-sex parents and child development had focused on young children, and most relevant research had been based on community samples of same-sex couple (often lesbian) families rather than on population-based, representative samples. Using data from Add Health, we examined a broad range of indicators of psychosocial well-being and achievement for youth, comparing those who grew up with same-sex coupled parents to a matched group with heterosexual parents. We examined indicators of the children’s depression, anxiety, grade-point average, school troubles, school attendance, school connectedness, and family relationship processes.

The results of our analyses showed that were there no differences across multiple measures of adolescent adjustment. Further, and especially important for the future of healthy families, there were no differences between adolescents with same-sex couple parents and adolescents with heterosexual parents in family processes (Wainright et al., 2004). Our research confirmed what the family scientists have long known: What happens within the context of families—family relationships—is what matter for adolescent adjustment. This work helped refine our understanding of what a healthy family is and can be. Children’s healthy development and adjustment depend not on family makeup but on the processes within a family (Parke, 2013).

LGBTQ Youth and Their Families

The focus of most of my recent research has been on LGBTQ youth and their health and well-being. From that work, I consider two areas of study that have implications for healthy families: the coming out of LGBTQ youth and the effects of parental or family rejection and acceptance on these adolescents’ well-being.

Coming out.

I begin with the issue of sexual identity disclosure, or “coming out.” Most of what has been known about coming out is that it is associated with negative outcomes for youth: bullying in school and negative relationships at home (D’Augelli, Pilkington, & Hershberger, 2002). In fact, the risks associated with coming out have been used to argue that LGBTQ content and activity should be banned from schools. In one important legal case, a school district banned the presence of a gay–straight alliance high school club because, the school district argued, youth would be at risk for victimization (Gay–Straight Alliance of Okeechobee High School v. School Board, 2007). Further, because prior research had documented mental and behavioral health risks, the school district argued that the presence of LGBTQ youth would make other youth in the school vulnerable to taking on the same identity. According to this school district, the presence of out LGBTQ students at school was not only a danger to themselves but to all students.

Studies of coming out in adolescence have indeed documented serious potential risks. Yet a separate body of research considers coming out as crucial for well-being in adults. Early models of adult sexual identity development focused on the culmination of healthy sexual identities through identity integration (Cass, 1979); that is, integrating gay or lesbian sexual identity as part of one’s master identity was understood as a positive, healthy adjustment. Indeed, research on adults suggests that coming out should be associated with positive adjustment and identity integration (Griffith & Hebl, 2002; Luhtanen, 2002), whereas the research on youth has historically framed coming out as related to vulnerability. So an important question has been: Despite the potential vulnerabilities of coming out as a young person, is coming out associated with positive overall adjustment as an adult?

Colleagues and I tested this question with data from the Family Acceptance Project, a study of 245 White and Latino 21- to 25-year-olds from Northern California (Russell, Toomey, Ryan, & Diaz, 2014). We examined being out in high school (as well as having to hide one’s LGBT identity) and its association with victimization during high school, as well as the association of those factors with young adult adjustment. First, consistent with the studies of youth, we found that being out in high school was associated with more victimization. However, we also found that the direct positive effects of being out were the strongest predictors of adjustment—stronger than the effect of LGBT victimization on subsequent adjustment. In short, even though being out was associated with a greater likelihood of being bullied, the data suggested that being out is associated with better adjustment later in young adulthood (Russell et al., 2014).

Coming out is an especially important period for families (and the study of families) because it is a period of heightened emotions for LGBTQ youth and for those to whom they come out. It is also characterized by shifts and tensions in family relationships (D’Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2005; Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2009). Thus, although coming out has been conceptualized largely in terms of individual identity development, much of the impact of coming out has to do with how the process is shaped by family rejection or acceptance (in addition to peer relationships and interactions at school), and the implications of these processes for individual youths’ well-being and for healthy families.

Family rejection and acceptance.

A comprehensive measure of parental rejection related to youth’s LGBT status was developed for the Family Acceptance Project. The measure included items ranging from physical and verbal abuse and rejection, coming-out rejection, victim blaming, regulation of gender and behavior, and regulation in the context of family activities (Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009). They found that high rejection during adolescence was associated with a dramatically higher rate of suicide ideation and a host of other risk behaviors and outcomes in young adulthood. In a different study, Rosario and colleagues (2009) showed that rejection in response to coming out was a strong predictor of a range of indicators of substance use and abuse in an ethnically diverse sample of more than 150 LGB youth, aged 14 to 21 years. Specifically, positive or neutral reactions did not directly reduce substance use and abuse, but positive reactions did buffer the link between rejection and substance use and abuse. Thus, although positive reactions alone were not protective, they tempered the negative influence of rejection (Rosario et al., 2009).

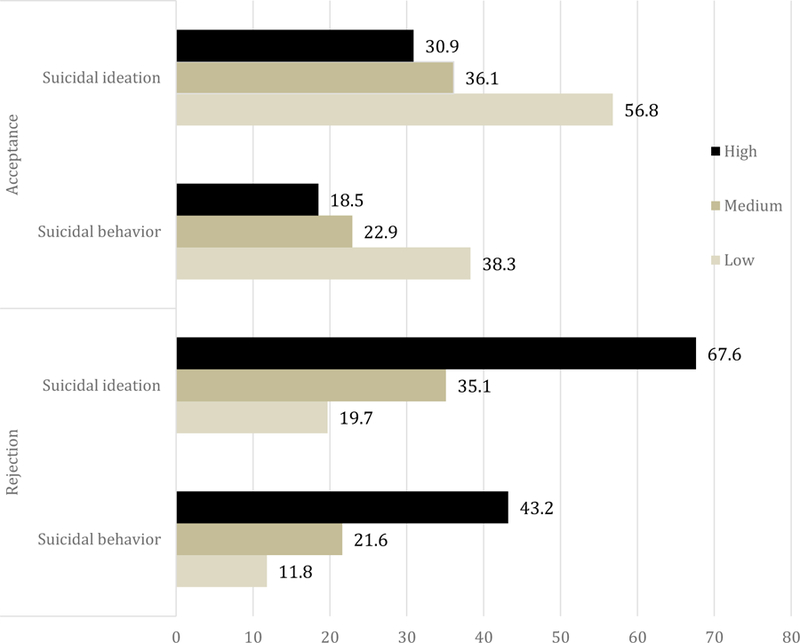

The Family Acceptance Project also included a measure of accepting behaviors, and a recent report found that fewer LGBT young adults reported high-risk outcomes if they also reported high levels of parental acceptance during adolescence (Ryan, Russell, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2010). Comparisons of parental acceptance and rejection for outcomes related to suicide risk are illustrated in Figure 1 (original data were reported in Ryan et al., 2009, 2010). High rejection is associated with extremely high rates of reported suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior compared with low rejection (67.6% vs. 19.7% for suicidal ideation, and 43.2% vs. 11.8% for suicidal thoughts), whereas high acceptance is protective. Youth with high family acceptance were nearly half as likely to report suicidal ideation or behavior compared with youth who reported low acceptance (30.9% vs. 56.8% for suicidal ideation, and 18.5% vs. 38.3% for suicidal behavior). There are several notable patterns here. First, the patterns are not clear opposites. Negative versus supportive reactions to children’s LGBT identity have been described as different constructs (Perrin et al., 2004), and in fact in the Family Acceptance Project, the correlation between rejection and acceptance was negative, but the size of the correlation was modest (r = –.34, p < .001). Thus, parents engaged in a range of behaviors with their LGBT children, and many youth reported both accepting as well as rejecting behaviors. For example, parents might allow or be supportive of their child’s social interactions with LGBT friends, but might regulate gender expression in the child’s dress or behavior. Second, the differences between the groups were larger for rejection than acceptance. This pattern was consistent with the finding that rejecting reactions to coming out are the distinct predictor of substance use and abuse (Rosario et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

Family acceptance and rejection in adolescence in association with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender young adult suicidal ideation and behavior (percentages), Family Acceptance Project. Note. Data sources for acceptance (Ryan et al., 2010) and rejection (Ryan et al., 2009).

Given the encouraging protective association of family acceptance in the context of coming out, scholars have attempted to determine whether family acceptance might also be a buffer for LGBTQ minority stress, such as homophobic victimization, bullying, and the negative outcomes that have been consistently documented for LGBTQ youth. However, there is little supporting evidence to suggest that this is the case. Rosario and colleagues’ (2009) study showed that positive reactions to coming out mitigated the association between rejecting reactions and substance use and abuse. Yet others have not found evidence for such moderation (including unpublished analyses from the Family Acceptance Project). For example, a large population-based sample of more than 15,000 adolescents in grades 7 to 12 showed that homophobic victimization predicts suicidality and that support from parents buffers the effect of homophobic victimization on suicidality—but only for heterosexual youth, not for LGBTQ youth (Poteat, Mereish, DiGiovanni, & Koenig, 2011). It may be that heterosexual youth are more likely to tell their parents when they experience homophobic bullying given that this disclosure would not threaten their sexual identity, whereas LGBTQ youth may not tell their parents and thus may not benefit from parental support. It also could be that parents provide heterosexual children different support in response to homophobic bullying (e.g., “don’t listen to them, it isn’t true”) compared with the support parents may provide LGBTQ children (e.g., “try to ignore them”), with distinct implications and meanings of comfort or support for their children.

Finally, in another study of more than 1,000 LGBTQ youth, my colleagues and I examined supportive family reaction to coming out as a possible buffer of the strong link between school victimization and suicidal ideation (Frank et al., 2013). When the initial results were null (consistent with the study by Poteat et al., 2011), we investigated five patterns of reaction to disclosure among parents: two nonsupportive parents, one nonsupportive (single) parent, one nonsupportive and one supportive parent, one supportive (single) parent, and two supportive parents. We found only one pattern for which family acceptance buffered children from school victimization and suicide: having positive reactions from two parents. These analyses showed that for parental support to be a buffer, the bar is very high: Only two supportive parents mitigated the effect of school victimization on suicide risk (Frank et al., 2013).

We had expected to find that parental support could buffer negative school experiences. Clearly, parents do matter: In all of these studies the main effect of parents’ support and acceptance was strong and protective (e.g., Ryan et al., 2010; Snapp, Russell, Watson, Diaz, & Ryan, 2015). However, these studies indicated that parent support does not balance out family rejection, nor does it buffer the effects of homophobic victimization that many LGBTQ youth experience.

These studies showed that parental rejection of children based on their LGBTQ identities is a key factor in youth well-being. Clearly, parental rejection is maladaptive for children (Rohner, Khaleque, & Cournoyer, 2005) and, from an evolutionary perspective (Bardwick, 1974), is contrary to the fundamental goals of parenting to protect and nurture offspring. What is remarkable is that during the past century in the United States (and around the world), cultures of homophobia and transphobia have developed that are so rigid, many parents believe they have no other alternative than rejection if their child is LGBTQ (Herdt & Koff, 2001). Most parents want the best for their children, but the fact that they are rejecting their LGBTQ children points to the challenges of normative cultural structures of homophobia and transphobia (Oswald, Blume, & Marks, 2005). Although efforts to change a child’s sexual or gender identity are understood to be harmful (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015), parental refusal to acknowledge a child’s asserted sexual identity or gender is rarely viewed as abuse. Thus, although parental rejection of LGBTQ children should be taboo, it is almost seen as “normal.” Parental acceptance should not be exceptional; it should be normative—and expected by children.

Therefore, socially, culturally, and historically speaking, LGBTQ family relationships are a distinct and strategic locus of inquiry for family scientists. In the context of societal heteronormativity (Oswald et al., 2005) and homo- and transphobia (McGuire, Kuvalanka, Catalpa, & Toomey, 2016), LGBTQ families are a unique setting in which fundamental expectations about family relations may be upended (for some) and thus provide novel insights into family processes. The results of these studies challenge the belief that parents can protect their children from all forms of harm, including discrimination and stigma in their communities and schools. Thus, studies of LGBTQ youth and their families offer new (although sobering) insights for all families. To fully understand and promote healthy families, we must broaden our view, from individuals and family processes and relationships to the structural conditions that either constrain families through prejudice and discrimination or create possibilities for full rights and social justice.

Families, Rights, and Justice

The research on LGBTQ youth and families shows that despite the risk of victimization, coming out appears to be adaptive, yet parental rejection has stronger negative effects than the positive effects of parental acceptance. Further, LGBTQ youth thrive when they have support from their parents and families, but that support is not enough in the context of discrimination and stigma in their communities and schools. In effect, it is not realistic to look to parents to be the source of intervention in preventing the negative influence of homophobia on LGBTQ youth. This is sobering news for those who study healthy families. However, given that experiences of LGBTQ victimization are only one form of the explicit manifestation of cultural homophobia and transphobia, it is also unrealistic to think that parents alone could protect youth against these pervasive structural conditions of discrimination and prejudice.

However, encouraging research identifies factors that can change the structural conditions related to LGBTQ families and youth. For example, several studies conducted in the United States have shown the association between legislation related to marriage for same-sex couples on LGB adult health. Specifically, LGB adults who lived in states that passed bans on marriage for same-sex couples reported more minority stress and psychological distress in one study (Rostosky, Riggle, Horne, & Miller, 2009), and another study showed increased levels of psychiatric morbidity in the years following a marriage ban (Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, Keyes, & Hasin, 2010). Given the breadth of rights and protections that marriage affords couples and their children, the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) to legally recognize marriage for same-sex couples is a structural change that should markedly improve the well-being of LGBTQ families.

Evidence has also emerged from the study of LGBTQ issues in education that points to concrete strategies to reduce homophobic discrimination in the lives of LGBTQ and all youth (Russell, Kosciw, et al., 2010). Specifically, there is solid evidence that policies, programs, and practices in schools can serve as moderators or buffers for LGBTQ stressors such as victimization. At the most basic level, inclusive laws and policies provide a foundation for creating supportive communities and schools for LGBTQ youth. Multiple studies have documented the links between LGBTQ-inclusive antibullying and nondiscrimination policies with student achievement and well-being (for a review, see Russell, Kosciw, et al., 2010). One study used a statewide, population-based study to show that suicide behaviors were lower for lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth who attended schools with inclusive antibullying policies (Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, 2013). Another study showed that the presence of school policies and practices focused on sexual orientation and gender identity was associated with teachers’ assessments of fewer bullying problems in schools, especially in schools that were judged as unsafe (Russell, Day, Ioverno, & Toomey, 2016).

Inclusive policies provide a foundation for other inclusive programs and practices in schools (Russell & McGuire, 2008), including proactive intervention by school personnel. Such strategies include intervening when harassment takes place (Kosciw, Diaz, & Greytak, 2008), as well as instituting supportive programs and curricula (Blake et al., 2001; Snapp, Burdge, Licona, Mordy, & Russell, 2015; Snapp, McGuire, Sinclair, Gabrion, & Russell, 2015), each of which is associated with supportive school climates and positive adjustment for students. There is also evidence that these factors make a difference at the school level, independent of individual students’ experiences: One study showed that students reported fewer anti-LGBT slurs if they attended schools where a greater proportion of teachers intervened in LGBT harassment and where a greater proportion of students reported learning about LGBT issues in the curriculum (Russell & McGuire, 2008).

Finally, at the level of students’ daily interactions in schools, strategies that promote visibility and inclusion of LGBTQ and other underrepresented groups promote student achievement and well-being. Availability of and access to LGBTQ information and resources have been linked to students’ perceptions of safety at school (for LGBTQ and heterosexual students), as well as to perceived school safety for LGBTQ and gender-nonconforming students (O’Shaughnessy, Russell, Heck, Calhoun, & Laub, 2004). Gay–straight alliance clubs (GSAs) are growing in number, and numerous studies now document their positive influence. For example, multiple studies have documented the importance of GSAs for their members (Russell, Muraco, Subramaniam, & Laub, 2009), and other studies have shown that even the presence of a GSA at a school (not necessarily participation in it) is associated with general school safety as well as a range of positive health behaviors, including lower rates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Goodenow, Szalacha, & Westheimer, 2006; Poteat, Sinclair, DiGiovanni, Koenig, & Russell, 2012; Szalacha, 2003) and improved school safety over time (Ioverno, Belser, Baiocco, Grossman, & Russell, 2016).

Taken together, the results of these studies have indicated that visibility and inclusion, proactive intervention, and inclusive policies are each strongly associated with LGBTQ student adjustment and achievement. In particular, these studies show that inclusive policies and proactive intervention—school-wide strategies independent of students’ daily activities and relationships—appear to be associated with well-being and buffering the effects of LGBTQ-related stressors.

Promoting Structural Change: The Role of Families

Overall, the research findings described thus far indicate that it may be too much to expect parents or families to be the primary buffers against stressors that come from structural discrimination toward LGBTQ youth, yet structural changes have the power to shift the conditions in which families live and promote their well-being. If what we need are structural interventions, what is the role then for families?

As part of a larger study of LGBT-inclusive antibullying and nondiscrimination laws for U.S. schools, colleagues and I (Russell, Horn, Moody, Fields, & Tilley, 2016) learned about the role that families can play in promoting structural changes to support LGBTQ youth and well-being. We were conducting a study to understand why some states had passed inclusive and enumerated antibullying and nondiscrimination laws for education that include sexual orientation and gender identity or expression but others had not. During the past decade, all U.S. states have passed bullying prevention laws: Some include enumeration of status characteristics associated with bullying (e.g., race, ethnicity, religion, disability, sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity or expression), whereas others have passed nonenumerated laws. Missouri, Alabama, and Massachusetts, for example, did not pass enumerated laws, yet Illinois, Oregon, Washington, and North Carolina did. We wanted to understand the unexpected pattern that some states considered to be at the forefront of LGBTQ issues (e.g., Massachusetts) had passed nonenumerated laws, whereas more historically conservative states (e.g., North Carolina) had passed enumerated or inclusive laws. We conducted interviews with 33 policy advocates—people directly involved in the advocacy process—from three states that had passed enumerated laws and three that had passed nonenumerated laws.

We did not design the study to focus on the role of parents, yet we learned that they were involved in policy advocacy in some states, and what we learned about their involvement was illuminating. In states that passed nonenumerated laws, policy advocates described opposition from conservative parents as a key impediment to enumeration. Notably, in the same states, parents supportive of enumerated legislation were consistently described as “just a small group of parents.” Thus, the rhetorically and legislatively powerful parents were those opposed to enumeration. In contrast, in states that passed enumerated laws, parents were described as being strong advocates who passionately shared their stories and the stories of their children regarding bullying. In North Carolina, we learned that groups of parents of students who had been bullied for different reasons (race, disability, and sexual orientation or gender identity) were explicitly involved in a coalition with one another to support enumerated legislation. Although we had not set out to study the role of parents or families in the legislative enumeration process, we observed that in states that did not pass enumeration, parents were perceived to be powerful and conservative in opposition to inclusion of sexual orientation and gender identity, and those in support were “a small group.” Yet in the historically conservative state of North Carolina, parents worked together in coalitions across differences to advocate for inclusion, and an enumerated law was passed.

Moving Forward

The example of the role of parents in policy advocacy for inclusive antibullying laws suggests the potential for parents and families to be involved in creating the structural changes that make a difference for reducing and buffering against discrimination and supporting healthy youth and families. There is great and untapped potential for family leadership and advocacy in policy changes that will create social justice for all children and all families; there is also an important role for family scholars in identifying these strategies and mechanisms and in supporting families in such engagement. What role do interpersonal and institutional stigma and prejudice play in undermining the health and well-being of families, and even in the very meaning of family in contemporary society? How can families themselves be encouraged and supported to promote health and social justice for their own families and others? In what ways might family scholars address those questions, especially in a cultural period in which conservative cultural constructions of “the family” increasingly shape the ways we understand social welfare and develop policies for families (Fineman, 1995)?

I have argued that through critical analysis of how we define, redefine, and refine the notion of family, we gain new vantage points on the complexities and possibilities of contemporary families, especially those that are marginal and marginalized. I have also acknowledged that our perspectives on healthy families are rooted in the context of our own personal experiences. With that context and with insights from scholarship on contemporary families, it may be possible to rethink the meaning of family, and even to do so in a way that contributes to the understanding and potential of not only marginal families but of all families. Given the research reviewed here, perhaps engagement in advocacy in schools and communities is as important a role for a parent as is personal social support for their individual children. Without losing sight of the processes within families to support individuals in their growth and development, attention to the role of families in producing structural change could shift what it means to parent, to be a parent, or to be a family. In other words, perhaps what it means to be a family may incorporate the actions individuals and families take to work for social justice in schools, policies, and communities, and in all institutions that shape the health of a family. Such a shift in thinking opens the possibility that as part of living and being in families, we might work together toward social change and justice for all families.

References

- Austen J (1817). Northanger Abbey London, England: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Bardwick JM (1974). Evolution and parenting. Journal of Social Issues, 30, 39–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb01754.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blake SM, Ledsky R, Lehman T, Goodenow C, Sawyer R, & Hack T (2001). Preventing sexual risk behaviors among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents: The benefits of gay-sensitive HIV instruction in schools. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 940–946. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.6.940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brontë A (1848). The tenant of Wildfell Hall London, England: T. C. Newby. [Google Scholar]

- Brontë E (1847). Wuthering Heights London, England: T. C. Newby. [Google Scholar]

- Cass VC (1979). Homosexuality identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality, 4, 219–235. doi: 10.1300/J082v04n03_01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK (1994). Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Development, 65, 1111–1119. doi: 10.2307/1131308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coontz S (1993). The way we never were New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Brown J, Iturbide MI, Russell ST, & Wilkinson-Lee A (2009). Conceptions of parent–adolescent relationships among Cuban American teenagers. Sex Roles, 60, 575–587. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9469-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Brown J, Russell ST, & Shen Y-L. (2007). The meaning of good parent–child relationships for Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17, 639–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00539.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Randall BA, Shen Y, Russell ST, & Driscoll AK (2005). Measurement equivalence of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Latino and Anglo adolescents: A national study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 47–58. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, & Starks MT (2005). Parents’ awareness of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth’s sexual orientation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 474–482. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00129.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Pilkington NW, & Hershberger SL (2002). Incidence and mental health impact of sexual orientation victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths in high school. School Psychology Quarterly, 17, 148–167. doi: 10.1521/scpq.17.2.148.20854 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll AK, Russell ST, & Crockett LC (2008). Parenting style and youth outcomes across immigrant generations. Journal of Family Issues, 29, 185–209. doi: 10.1177/0192513X07307843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr., & Conger RD, with King V, Mekos D, Russell ST, & Shanahan MJ (2000). Children of the land: Adversity and success in rural America Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fields A, Snapp S, Russell ST, Licona AC, & Tilley EH (2014). Youth voices and knowledges: Slam poetry speaks to social policies. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 11, 310–321. doi: 10.1007/s13178-014-0154-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fineman ML (1995). Masking dependency: The political role of family rhetoric. Virginia Law Review, 2181–2215. [Google Scholar]

- Frank J, McCutcheon MJ, Belsera A, Huynha PTT, Greenberg M, Russell ST, & Grossman AA (2013, November). Suicidal ideation and parental reactions to LGBT identity disclosure Poster presented at the 2013 American Public Health Association Convention, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Gay–Straight Alliance of Okeechobee High School v. School Board, 483 F. Supp. 2d 1224, 2007. U.S. Dist. LEXIS 25729 (S.D. Fla., 2007) [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow C, Szalacha L, & Westheimer K (2006). School support groups, other school factors, and the safety of sexual minority adolescents. Psychology in the Schools, 43, 573–589. doi: 10.1002/pits.20173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith KH, & Hebl MR (2002). The disclosure dilemma for gay men and lesbians: “Coming out” at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 1191–1199. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.6.1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, & Keyes KM (2013). Inclusive anti-bullying policies and reduced risk of suicide attempts in lesbian and gay youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(Suppl. 1), S21–S26. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, & Hasin DS (2010). The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 452–459. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdt G, & Koff B (2001). Something to tell you: The road families travel when a child is gay New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ioverno S, Belser AB, Baiocco R, Grossman AH, & Russell ST (2016). The protective role of gay–straight alliances for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning students: A prospective analysis. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3, 397–406. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Diaz EM, & Greytak EA (2008). 2007 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation’s schools New York, NY: GLSEN. [Google Scholar]

- Licona AC, & Russell ST (2013). Transdisciplinary and community literacies: Shifting discourses and practices through new paradigms of public scholarship and action-oriented research. Community Literacy Journal, 8, 1–7. doi: 10.1353/clj.2013.0013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luhtanen RK (2002). Identity, stigma management, and well-being: A comparison of lesbians/bisexual women and gay/bisexual men. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 7, 85–100. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n01_06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JK, Kuvalanka KA, Catalpa JM, & Toomey RB (2016). Transfamily theory: How the presence of trans* family members informs gender development in families. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 8, 60–73. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shaughnessy M, Russell ST, Heck K, Calhoun C, & Laub C (2004). Safe place to learn: Consequences of harassment based on actual or perceived sexual orientation and gender non-conformity and steps for making schools safer San Francisco: California Safe Schools Coalition; Retrieved from http://www.casafeschools.org/SafePlacetoLearnLow.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Oswald RF, Blume LC, & Marks SR (2005). Decentering heteronormativity: A model for family studies. In Bengtson VL, Acock AC, Allen KR, Dilworth-Anderson P, & Klein DM (Eds.), Sourcebook of family theory and research (pp. 143–166). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD (2013). Future families: Diverse forms, rich possibilities Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin EC, Cohen K, Gold M, Ryan C, Savin-Williams R, & Schorzman C (2004). Gay and lesbian issues in pediatric health care. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 34, 355–398. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2004.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Mereish EH, DiGiovanni CD, & Koenig BW (2011). The effects of general and homophobic victimization on adolescents’ psychosocial and educational concerns: The importance of intersecting identities and parent support. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 597–609. doi: 10.1037/a0025095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Sinclair KO, DiGiovanni CD, Koenig BW, & Russell ST (2012). Gay–straight alliances are associated with student health: A multi-school comparison of LGBTQ and heterosexual youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23, 319–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00832.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP, Khaleque A, & Cournoyer DE (2005). Parental acceptance–rejection: Theory, methods, cross-cultural evidence, and implications. Ethos, 33, 299–334. doi: 10.1525/eth.2005.33.3.299 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, & Hunter J (2009). Disclosure of sexual orientation and subsequent substance use and abuse among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: Critical role of disclosure reactions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23, 175–184. doi: 10.1037/a0014284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky SS, Riggle EDB, Horne SG, & Miller AD (2009). Marriage amendments and psychological distress in lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 56–66. doi: 10.1037/a0013609 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST (2015). Human developmental science for social justice. Research in Human Development, 12, 274–279. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2015.1068049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST (2016). Social justice, research, and adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26, 4–15. doi: 10.1111/jora.12249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Chu JY, Crockett LJ, & Doan SN (2010). The meanings of parent–adolescent relationship quality among Chinese American and Filipino American adolescents. In Russell ST, Crockett LJ, & Chao R (Eds.), Asian American parenting and parent-adolescent relationships: Advancing responsible adolescent development New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Crockett LJ, & Chao R (Eds.). (2010). Asian American parenting and parent–adolescent relationships New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Day JK, Ioverno S, & Toomey RB (2016). Are school policies focused on sexual orientation and gender identity associated with less bullying? Teachers’ perspectives. Journal of School Psychology, 54, 29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2015.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Franz B, & Driscoll AK (2001). Same-sex romantic attraction and violent experiences in adolescence. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 907–914. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.6.903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Horn SS, Moody RL, Fields A, & Tilley E (2016). Enumerated U.S. state laws: Evidence from policy advocacy. In Russell ST & Horn SS (Eds.), Sexual orientation, gender identity, and schooling: The nexus of research, practice, and policy New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, & Joyner K (2001). Adolescent sexual orientation and suicide risk: Evidence from a national study. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 1276–1281. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.8.1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Kosciw J, Horn S, & Saewyc E (2010). Safe schools policy for LGBTQ students. Society for Research in Child Development Social Policy Report, 24(4), 3–17. doi: 10.1002/j.2379-3988.2010.tb00065.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, & McGuire JK (2008). The school climate for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) students. In Shinn M & Yoshikawa H (Eds.), Changing schools and community organizations to foster positive youth development (pp. 133–158). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Muraco A, Subramaniam A, & Laub C (2009). Youth empowerment and high school gay–straight alliances. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 891–903. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9382-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Seif HM, & Truong NL (2001). School outcomes of sexual minority youth in the United States: Evidence from a national study. Journal of Adolescence, 24, 111–127. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Toomey RB, Ryan C, & Diaz RM (2014). Being out at school: The implications for school victimization and young adult adjustment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84, 635–643. doi: 10.1037/ort0000037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Truong NL, & Driscoll AK (2002). Adolescent same-sex romantic attractions and relationships: Implications for substance use and abuse. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 198–202. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.2.198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, & Sanchez J (2009). Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics, 123, 346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Russell ST, Huebner D, Diaz R, & Sanchez J (2010). Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23, 205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snapp S, Burdge H, Licona AC, Moody R, & Russell ST (2015). Students’ perspectives on LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum. Equity and Excellence in Education, 48, 249–265. doi: 10.1080/10665684.2015.1025614 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snapp S, McGuire J, Sinclair K, Gabrion K, & Russell ST (2015). LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum: Why supportive curriculum matters. Sex Education, 15, 580–596. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2015.1042573 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snapp S, Russell ST, Watson RJ, Diaz RM, & Ryan C (2015). Social support networks for LGBT young adults: Low cost strategies for positive adjustment. Family Relations, 64, 420–430. doi: 10.1111/fare.12124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2001). We know some things: Parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11, 1–19. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2015). Ending conversion therapy: Supporting and affirming LGBTQ youth (HHS Publication No. (SMA) 15–4928) Rockville, MD: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Szalacha LA (2003). Safer sexual diversity climates: Lessons learned from an evaluation of Massachusetts safe schools program for gay and lesbian students. American Journal of Education, 110, 58–88. doi: 10.1086/377673 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wainright JL, Russell ST, & Patterson C (2004). Psychosocial adjustment, school outcomes, and romantic attractions of adolescents with same-sex parents. Child Development, 75, 1886–1898. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00823.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]