Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study is to assess criteria for gout remission and to use the results to inform criteria for a complete response (CR).

Methods

A post hoc analysis of two clinical trials was undertaken to determine the frequency with which subjects with chronic refractory gout who were treated with pegloticase met remission criteria. Mixed modeling was then employed to identify the components that best correlated with time to maximum benefit.

Results

Of the 56 subjects treated with biweekly pegloticase for whom adequate data were collected, 48.2% met the remission criteria. When subjects with persistent lowering of urate levels were examined separately, 27 of 32 (84.4%) met the criteria for remission. In contrast, even when the requirement for lowering of serum urate levels was waived, only 2 of 24 (8.3%) subjects without persistent lowering of urate levels and 0 of 43 subjects receiving placebo met criteria. Mixed modeling indicated that in addition to urate levels, assessment of tophi, swollen joints, and tender joints and patient global assessment best correlated with time to maximum benefit. Using these criteria of CR, 23 of the responders (71.9%) met the criteria. All patients who achieved a CR maintained it for a mean duration of 507.4 days. Finally, 64% of persistent responders to monthly pegloticase also met criteria for CR.

Conclusion

These results have validated the proposed remission criteria for gout and have helped define criteria for CR in individuals with chronic gout treated with pegloticase. This composite CR index can serve as an evidence‐based target to inform the design and end points of future clinical trials.

Significance & Innovations.

A post hoc analysis of data from published randomized controlled trials of pegloticase in chronic refractory gout clearly documented the ability of the proposed remission criteria in gout to distinguish subjects who had persistent lowering of urate levels from those who had only transient lowering or who received placebo.

Using these results and mixed modeling, novel evidence‐based criteria for a complete response (CR) were generated and tested using the data from the pegloticase trials.

Of persistent responders to pegloticase, 71.9% met the criteria of a CR in a mean time of 346 days.

These composite outcome measures should be useful as end points in clinical trials and treat‐to‐target strategies.

Introduction

Treating to target is an approach to disease management that considers well‐defined physiologic targets for controlling disease activity and the means to achieve them (1). This approach has become the standard of care in many chronic diseases, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis (2, 3), and a treat‐to‐target approach has been suggested for gout (1, 4, 5, 6). However, the treatment goals for patients with this disease have not been fully defined (7, 8, 9).

Treatment goals for gout have typically been focused on the biochemical response to treatment (ie, lowering serum urate levels to less than 6 mg/dl) and on even lower levels in selected patients, such as those with extensive monosodium urate (MSU) crystal deposition (7, 8, 9). However, reaching these levels does not guarantee achievement of clinical goals. Gout flares may still occur despite urate levels at less than 6.8 mg/dl (the saturation level for urate) possibly because of persistent tophi and an increased body urate pool (10).

It is likely that in subjects with chronic or advanced gout, the focus on serum urate to define success of gout treatment is too narrow and that clinical goals may vary based on factors including the burden of MSU crystal deposition, the nature of the clinical manifestation, and expectations of patients (11, 12). In subjects with advanced gout, resolution of tophi is a major goal of treatment, but it is difficult to achieve with current oral urate level–lowering therapy. Although the development of tophi in subjects with gout is related to the serum urate level and the duration of hyperuricemia (13), the relationship between urate and tophus development is not precise because only 50% of subjects develop obvious tophi within 10 years of an initial gout flare, whereas 28% remain free of tophi even 20 years after an initial gout flare (14). Moreover, although the velocity of reduction of tophus burden is correlated with serum urate levels, the correlations reported are modest (r = 0.4 and 0.6) (15, 16), indicating that other variables influence this process.

Composite indices have been developed to assess the activity of gout, and one of these, the Gout Activity Score (GAS), has recently been demonstrated to be sensitive to change (17, 18, 19). However, the GAS measures the level of disease activity in a number of domains and does not provide a target for remission of gout activity. In a recent Delphi exercise focused on defining criteria for remission in gout, consensus was reached on a multidimensional definition that included serum urate levels less than 6 mg/dl, no flares, resolution of all tophi, and limited pain and low patient global assessment (PGA) score of disease activity, each with a score of less than 2 on a 10‐cm visual analog scale (VAS) (20). Although these proposed remission domains have some overlap with those of the GAS, they are not identical, including pain as an outcome. Moreover, the remission criteria encompass achievement of specific goals to be considered to have achieved remission. Although the criteria for remission were proposed, they have not been tested in longitudinal clinical trials. Moreover, their utility in chronic or advanced gout have not been examined.

Therefore, this study evaluated the utility of these proposed criteria using clinical results from patients with chronic refractory gout who received pegloticase (8 mg every 2 weeks), a mammalian recombinant uricase conjugated to polyethylene glycol that is approved for treatment of adult patients with chronic gout refractory as an oral urate level–lowering therapy. Specifically, all clinical data from subjects collected at each clinical visit were evaluated by an independent investigator to determine whether the subject met remission criteria at that visit.

Patients and Methods

Design of pegloticase clinical trials

Results from two identical randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of pegloticase and their open‐label extension (OLE) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT00325195 and NCT01356498) were analyzed. The methods for these studies have been described in detail, and they will be summarized only briefly here (21, 22).

Patients were 18 years of age or older and had chronic refractory gout (defined as a baseline serum urate acid [sUA] of 8.0 mg/dl or more) and one or more of the following: 1) three or more self‐reported gout flares during the previous 18 months; 2) one or more tophi; 3) gouty arthropathy, defined clinically or radiographically as joint damage caused by gout; and 4) contraindication to treatment with allopurinol or history of failure to normalize serum urate despite 3 or more months of treatment with the maximum medically appropriate allopurinol dose as determined by the treating physician. Patients were randomly assigned to 6 months of treatment with intravenous infusions of either pegloticase 8 mg at each infusion, pegloticase 8 mg alternating with a placebo, or a placebo (21). Flare‐prevention medication (hydrocortisone and antihistamines) was given to all subjects. After the RCT, subjects were given the option of entering an OLE to assess the persistence of the response.

A responder to treatment (primary end point for the RCTs) was defined as a patient with a serum urate level less than 6.0 mg/dl for greater than or equal to 80% of the time during months 3 and 6. Nonresponders were all other subjects, including those who left the study early. Secondary end points included tophus resolution, reductions in the proportion of patients with gout flares and in the number of flares per patient during months 1‐3 and 4‐6 of the trial, reduction in tender joint counts (TJCs) and swollen joint counts (SJCs), and patient‐reported changes in pain, physical function, and quality of life, as measured by the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) pain scale, the HAQ–Disability Index, and the 36‐item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36), respectively (21). This study was completed before the remission criteria were proposed, and remission was not an outcome measure.

Tophus assessment was conducted using Computer‐Assisted Photographic Evaluation in Rheumatology (CAPER) methodology (23). Photographs of the hands and feet were taken for each patient at baseline. Photographs of up to two additional regions were taken at the discretion of the investigator based on other tophi identified at baseline. Digital media cards containing the photographs were sent to RadPharm, where central readers, who were blinded to treatment assignment, evaluated the photographs prospectively and identified sites of tophi present at the start of treatment and identified response to therapy. Patients completing either of two replicate RCTs were eligible to enter an OLE for up to 3 years in which they received 8 mg of pegloticase every 2 weeks. Safety was evaluated as the primary outcome, but the previously described efficacy variables were also assessed (22).

Relating clinical responses to published criteria for gout remission

Of the 85 subjects who entered the RCTs and received 8 mg of pegloticase biweekly, a total of 56 proceeded to the OLE, and sufficient data were collected to assess whether they met criteria of remission. Of these subjects, 36 responded to treatment in the RCTs (ie, a persistent serum urate level less than 6 mg/dl), 34 entered the OLE (20), and 32 had adequate data collected to assess. Of those without persistent lowering of urate levels in the RCT (nonresponders), 24 proceeded to the OLE and had sufficient data collected to be analyzed. Initially, individual patient data from each clinic visit were reviewed by an independent evaluator to establish the frequency with which subjects met the proposed remission criteria. To be classified as meeting remission criteria, a subject was required to have a serum urate level less than 6 mg/dl, no flares during the time since the last visit, no detectable tophi, and a pain and PGA score of less than 2 on a 10‐cm VAS. Only subjects who met all five criteria were considered to meet criteria of remission. Subsequently, this group of subjects was employed to determine new criteria for a complete response (CR) by using mixed modeling.

A repeated‐measures mixed‐effects model that controlled for repeated observations was used to relate the time when a response was noted in PGA scores, SF‐36 bodily pain scores, VAS pain levels, TJC, SJC, the number of flare episodes, and the degree of tophus resolution. Variables were then excluded by using backward elimination of the least statistically significant term. The final model included all terms that were statistically significant. The results from the analysis of patients who responded to administration of pegloticase every 2 weeks were validated with a second analysis of results for patients who responded to administration of pegloticase every 4 weeks in the RCTs.

Additional analyses conducted using results from this patient cohort included analyses of the following: 1) time to achieve remission according to the criteria set forth in the Delphi exercise (20); 2) correlations among components of remission and CR for patients meeting the criteria for remission; 3) the relationship between flares, serum urate levels, and clinical characteristics for patients who met the criteria for remission; 4) time to CR for all responders in the RCTs for pegloticase; and 5) the relationship between time to achieve CR and duration of that response.

The relationships between flares and other clinical variables, including TJCs and SJCs, VAS pain, SF‐36 pain, PGA, percent reduction from baseline in tophus area, and sUA, were also evaluated for all 56 patients (responders and nonresponders) who were treated with pegloticase every 2 weeks in the RCTs and who continued to the OLE. Each subject was evaluated every 2 weeks, and if a flare was reported, the values for all measures were evaluated at the subsequent visit to determine the association with the flare. If no flare was reported for the 2 weeks before the evaluation, all measures were considered to be unrelated to flares. Values for each measure that were associated or not associated with flares were compared using Wilcoxon signed rank tests.

Results

Achievement of remission

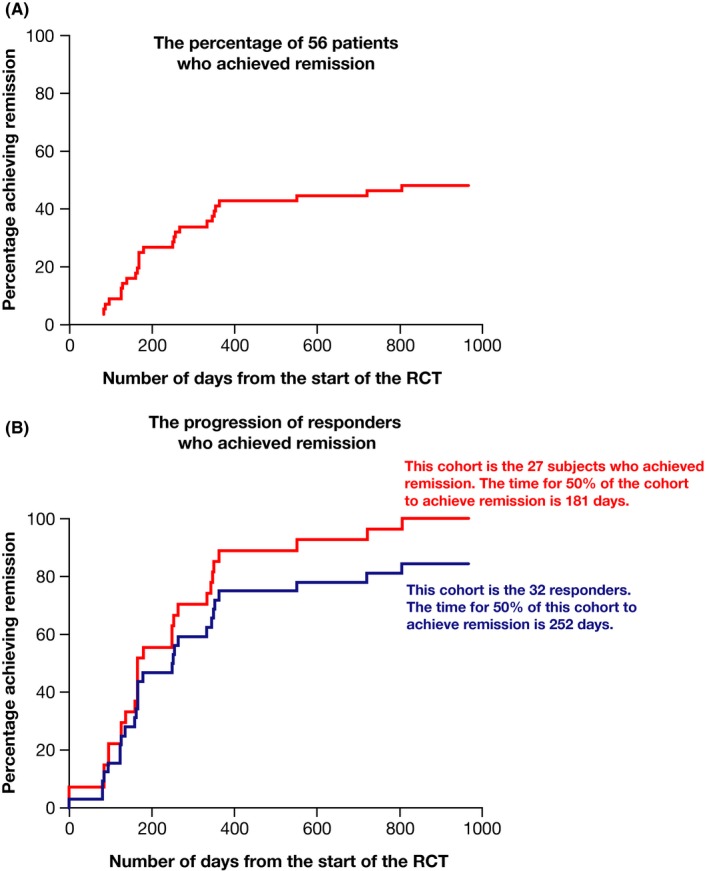

Of the 56 evaluable subjects treated with biweekly pegloticase, 27 (48.2%) met criteria for remission (Figure 1A). Because this group of subjects included both those who had persistent lowering of urate levels in response to pegloticase (n = 32) and those with only transient lowering of urate levels (n = 24), it was of interest to determine whether the attainment of remission was associated with persistent lowering of urate levels. Of the 32 responders to pegloticase in the RCTs who entered the OLE, 27 (84.4%) met the criteria for remission (Figure 1B). When the requirement of a serum urate level less than 6 mg/dl was waived, only 2 of 24 (8.3%) nonresponders and 0 of 43 (0.0%) subjects receiving a placebo met clinical criteria for remission. The times to achieve remission for all responders to pegloticase in the RCTs and for those who met the criteria for remission are shown in Figure 1B. The length of time required for 50% of patients to achieve remission was 252 days (8.4 months) for all responders and 181 days (6.0 months) for responders who achieved remission.

Figure 1.

Time to achieve remission criteria in the entire group of subjects treated with biweekly pegloticase (A) and in subjects who met the criteria of responder and had persistent lowering of urate levels (B). The two lines in B represent data from the entire responder cohort (n = 32) and data from those who met remission criteria (n = 27). RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Relationships between flares, serum urate levels, and patient clinical characteristics

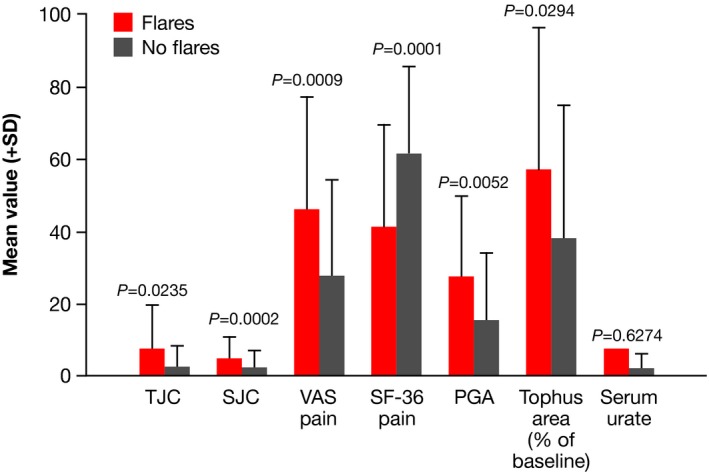

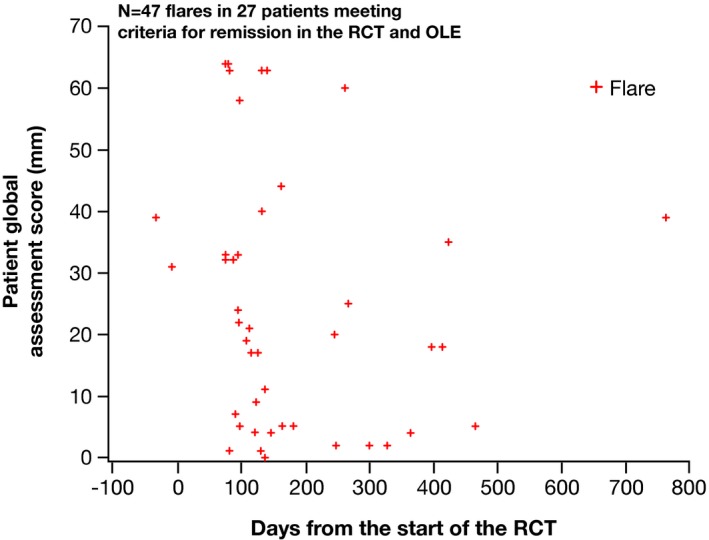

In order to determine whether the various domains of the remission model contributed information, we attempted to develop correlations between the various components. First, we assessed relationships between gout flares and other variables. As can be seen in Figure 2, all clinical variables were significantly worse at the time of a flare compared with assessments when there was no flare. However, the variance was great, and the differences, albeit statistically significant, were small. Notably, there was no significant difference between the serum urate level at the time of a flare and the serum urate level at other times. To examine this in greater detail, we assessed each clinical variable at the time of flares in the 26 subjects who met criteria of remission and experienced flares. As can be seen in Figure 3, PGA, for example, varied widely at the times of flares in these subjects.

Figure 2.

Mean values (+SD) for clinical measures taken at clinical visits that were or were not associated with flares. Results are for all patients (n = 56) treated with pegloticase every 2 weeks in the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and the open‐label extension (OLE). There were 147 observations associated with flares and 201 observations not associated with flares. PGA, patient global assessment score; SF‐36, 36‐item Short Form Health Survey; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count; VAS, visual analog scale.

Figure 3.

Values for patient global assessment at the time of flares for q2w responders who met the remission criteria. OLE, open‐label extension; q2w, every 2 weeks; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Table 1 shows correlations between all components of remission and other clinical features in the 29 responders that met criteria of remission. Results of this analysis indicated weak or absent correlations among many of these variables. The highest correlation noted was between the two pain assessments (r = 0.79), whereas the association between pain and TJC was lower (r =0.32‐0.34), and the association between pain and SJC was even less (r = 0.16‐0.23). Even the association between pain and PGA was modest (r = 0.45‐0.49). These results indicate that the components of the remission criteria may not all be improving contemporaneously in subjects with chronic or advanced gout and that other sets of characteristics may be more effective at defining a state of disease quiescence.

Table 1.

Correlations between all components of remission and other clinical features in the 29 serum urate responders meeting criteria of remission

| Variable | SF‐36 pain | VAS pain | SJC | TJC | PGA | Tophus Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum urate | ‐0.34787 | 0.22553 | −0.09753 | 0.00727 | 0.13198 | 0.00523 |

| P‐value | <.0001 | 0.0004 | 0.0854 | 0.8982 | 0.0201 | 0.9493 |

| SF‐36 pain | −0.79152 | −0.23102 | −0.34343 | −0.49247 | −0.13874 | |

| P‐value | <0.0001 | 0.0006 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0915 | |

| VAS pain | 0.15509 | 0.32799 | 0.45337 | 0.20606 | ||

| P‐value | 0.0226 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0123 | ||

| SJC | 0.55837 | 0.57825 | −0.04911 | |||

| P‐value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.5506 | |||

| TJC | 0.63261 | 0.0923 | ||||

| P‐value | <0.0001 | 0.2613 | ||||

| PGA | 0.0688 | |||||

| P‐value | 0.4028 | |||||

|

Tophus Category Progressive disease = 2 Stable disease = 3 Partial response = 4 Complete response = 5 | ||||||

Abbreviation: PGA, patient global assessment score; SF‐36, 36‐item Short Form Health Survey; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count; VAS, visual analog scale.

Results of mixed modeling

To develop new composite criteria for a CR from this data set, repeated‐measures mixed‐effects modeling with backward elimination of components with the least statistical significance was conducted. Because gout is a chronic disease with a genetic predisposition and a biochemical underpinning, the new composite outcome measure determined from mixed modeling was considered to be a CR rather than remission. The final criteria for CR were a serum urate level less than 6 mg/dl, resolution of all measured tophi, a PGA score of 1 or more, a SJC of 1 or more, and a TJC of 1 or more.

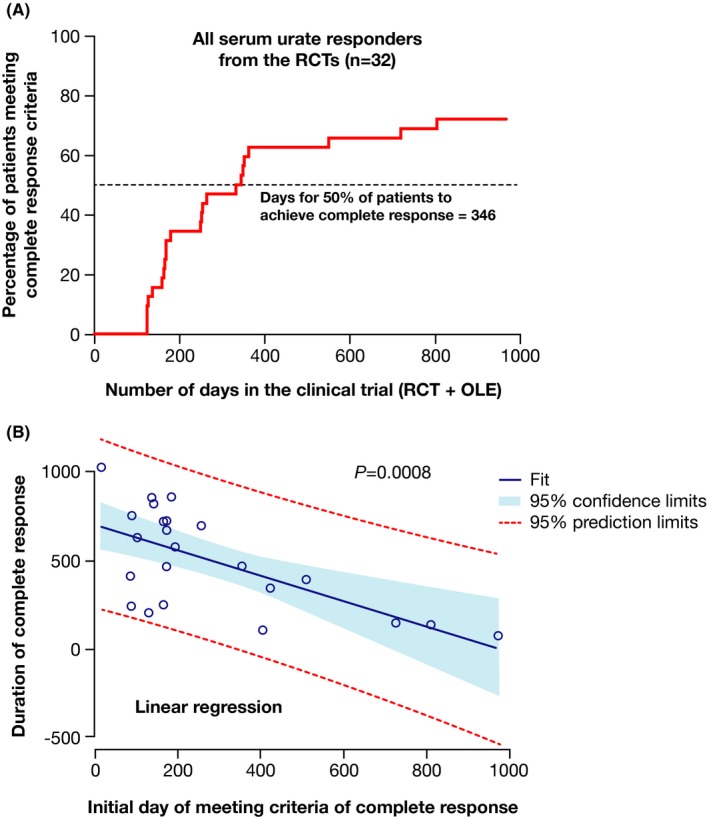

Achievement and maintenance of CR

The time to achieve a CR for all 34 responders is shown in Figure 4A. Of the 32 responders, 23 (71.9%) met the criteria of CR. The time it took for 50% of patients to achieve a CR was 346 days. All patients who achieved a CR maintained it until the end of the follow‐up. The mean duration of a CR was 507.4 days. There was a significant inverse relationship between the time to CR and the duration of the response (P = 0.0008; Figure 4B).

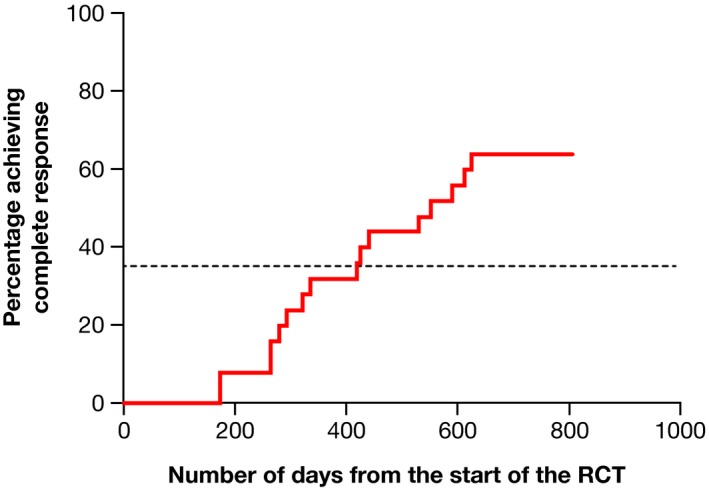

Figure 4.

A, Time to complete response (sUA responders in RCTs). B, Relationship between time to achieve complete response and duration of response. OLE, open‐label extension; RCT, randomized controlled trial; sUA, serum uric acid.

Analysis of results for patients who responded to administration of monthly pegloticase

The additional analysis of 25 patients who responded to administration of pegloticase every 4 weeks and completed the RCTs indicated that 16 (64%) met the criteria for a CR and that 50% of this subgroup achieved this response in 424 days (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Time to complete response for patients who responded to administration of pegloticase every 4 weeks. Complete response was achieved by 16 (64%) of 24 patients, with 50% achieving this response in 424 days. RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Discussion

We report herein the first effort to validate the proposed remission criteria in gout using a data set from a therapeutic intervention. The proposed criteria for remission had been developed by Delphi consensus exercises but had not been tested using a data set from a randomized clinical trial (20). This post hoc evaluation indicated that 85.3% of responders to biweekly pegloticase met the criteria for remission, which included a serum urate level less than 6 mg/dl, no tophi, no flares, a pain score of less than 2 on a 10‐cm VAS, and a PGA score of less than 2 on a 10‐cm VAS. These criteria were assessed at each clinic visit by an independent evaluator who reviewed the individual patient records, and all five criteria were required to be present contemporaneously for the subject to be considered as meeting the criteria of remission. Importantly, the clinical components of the criteria (omitting serum urate levels) could also distinguish between those with persistent lowering of serum urate levels (responders) and those without persistent lowering of urate levels (nonresponders) to the study medication and also between treated subjects and those receiving a placebo.

Therefore, the proposed remission criteria clearly appeared to be effective in distinguishing the quality of the response in subjects with chronic refractory gout treated with pegloticase. Notably, however, there was modest or no correlation between many components of the remission criteria. This suggested that the remission criteria were not ideal in assessing the quality of responses in chronic or advanced gout and that an alternative model might be more effective. Using a repeated‐effects mixed model with backward elimination, criteria for a CR in chronic or advanced gout were developed. Using these criteria, the vast majority of individuals (71.9%) with chronic or advanced gout treated with pegloticase who achieved persistently lower serum urate levels reached criteria for CR; 50% of patients treated with pegloticase achieved CR in 11.5 months. The results from the subjects in the RCTs who responded to treatment with intravenous pegloticase administered every 2 weeks were validated with a second independent analysis of clinical results of patients treated with monthly intravenous pegloticase who met the response criteria in the RCT; 64% of these patients met the criteria for a CR, with 50% achieving this response in 424 days. Although this validation exercise is not ideal because these subjects were part of the same RCTs that were used to generate the CR criteria, few other clinical trial data sets are available with sufficient clinical impact to assess the induction of a CR.

Although optimistically biased, the results from the monthly pegloticase cohort are intriguing because they suggest that fewer subjects in the monthly pegloticase treatment group achieve a CR and that it takes a longer period of treatment than was determined in the group receiving biweekly pegloticase, a result suggested in the RCTs, in which monthly pegloticase was less effective (21). All of these results support the view that a composite index to determine a CR could be useful in a treat‐to‐target strategy.

It should be noted that the Delphi exercise (20) and the present study are not the only efforts to develop a composite measure of disease control in patients with gout. In one retrospective chart review, disease control for patients with gout was defined as a 12‐month average serum urate level less than or equal to 6 mg/dl, no flares, and no tophi (three of the five criteria in the proposed remission criteria), and it was noted that only 11% of 858 patients whose records were evaluated achieved this goal (24). The Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials (OMERACT) also endorsed specific domains that should be assessed in clinical trials of therapies for chronic gout and corresponding instruments for their measurement (25). Based on OMERACT core domains and Delphi exercises, the GAS was developed. The first candidate of the GAS included seven indicators: 1) a 12‐month flare count, 2) the serum urate level, 3) pain (VAS), 4) VAS global activity assessment, 5) SJC, 6) TJC, and 7) the cumulative measure of tophi. A second iteration included flares, serum urate, PGA, and the number of tophi. This final GAS demonstrated a good correlation with functional disability (criterion validity) and discrimination between patient‐ and physician‐reported measures of active disease (construct validity) (17). In comparing different response criteria, it should be noted that those selected on the basis of the analysis conducted in the present study were the first set to be derived from data in a clinical trial to clearly show responsiveness to change and to focus on chronic or advanced gout.

The present results, particularly the weak relationship between the occurrence of flares and other response measures in the patients who achieved remission, challenge the utility of this outcome. The findings that there were modest or absent correlations between many of the clinical characteristics and that there was wide variation in clinical features at the time of a flare support the results of the repeated‐measures mixed‐effects modeling that did not include absence of flares in the criteria for a CR. The lack of a strong relationship between flares and other clinical characteristics should not be taken as evidence that flares are unimportant in patients with gout. This view is supported by results for all patients who received pegloticase every 2 weeks, which showed that TJCs and SJCs, pain, and PGA were all significantly worse near the times of flares versus times when flares had not occurred. The absence of a relationship between flares and other variables and the high variability in PGA scores at the time of flares in patients who met the criteria for remission may be related to the very broad definition of flares in these studies, which was “self‐reported acute joint pain and swelling requiring treatment” (21). A more rigorous flare definition, such as the one recently proposed by Gaffo et al (26) (ie, presence of three or more of the four following criteria: 1) patient‐defined gout flare, 2) pain at rest of more than 3 on a 0‐10 numeric rating scale, 3) presence of at least one swollen joint, and 4) presence of at least one warm joint), may be more suitable for use in future studies of gout treatment and could result in flares being included in CR criteria.

It has been noted that when establishing treatment targets, clinicians should consider outcomes most important to patients (27), and results from one analysis have suggested that development of a composite outcome may be difficult from this perspective. Results from a study in which three patient groups rated the importance of different outcomes indicated that the relative importance accorded to each outcome domain was different across the groups. Both the presence of tophi and pain between flares were ranked as less important, whereas gout flares were ranked as more important, and the relative importance of serum urate levels and activity limitations was variable (27). The relatively low importance of tophi to patients in this study is surprising because an assessment of 110 patients with severe treatment‐failure gout showed that the presence of tophi was associated with significantly worse bodily pain, general health, physical role functioning, social functioning, vitality, and physical component scores, as measured by the SF‐36 (28). However, another analysis indicated that frequency of flares and severity and duration of pain, but not serum urate levels or the presence of tophi and the number of joints involved in a typical flare, significantly impacted the patient's quality of life (29). The development of evidence‐based criteria for CR may provide the basis for future examination of the relationship between patient expectations and results of clinical trials and may provide more effective goals for a treat‐to‐target strategy.

There are limitations to this study. First, the data were derived from two identical RCTs with an OLE and will require confirmation with other data sets. Secondly, as mentioned previously, the results of the validation exercise for the CR criteria were likely to be optimistically biased because they were obtained from a cohort from the same RCTs used to generate the composite measure. Finally, this analysis was conducted in a group of subjects with advanced gout who met entry criteria for a clinical trial of subjects with chronic refractory gout. Whether the proposed criteria will be useful in subjects with less advanced gout remains to be determined. Regardless, the data provide a first step in validating the proposed criteria for remission in gout and suggest an additional evidenced‐based set of criteria to identify subjects with a CR.

In conclusion, the present study employed clinical trial data to validate the proposed gout remission criteria and to define criteria that tended to track together more than the components of the remission criteria. This composite complete responder measure can serve as an evidence‐based target to inform the design and end points of future urate level–lowering therapy trials in chronic gout.

Author Contributions

All authors drafted the article, revised it critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published, had full access to all of the data in the study, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Independent data analysis was supported by funding from Horizon Pharma. Dr. Schlesinger's work was not supported by research grants from Pfizer and Amgen.

Dr. Schlesinger has received research grants from Pfizer and Amgen, that did not support the work in this paper, and also has received consulting fees from Novartis, Horizon Pharma, Selecta Biosciences, Olatec, IFM Therapeutics, and Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Edwards has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Horizon Pharma, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and Swedish Orphan Biovitrum International. Dr. Khanna has received consulting fees from Horizon Pharma, Ironwood, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Yeo has received contractor fees from Horizon Pharma. Dr. Lipsky has received consulting fees from Horizon Pharma. No other disclosures relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1. Kiltz U, Smolen J, Bardin T, Cohen Solal A, Dalbeth N, Doherty M, et al. Treat‐to‐target (T2T) recommendations for gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;76:632–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Atar D, Birkeland KI, Uhlig T. ‘Treat to target’: moving targets from hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes to rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:629–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smolen JS. Treat‐to‐target as an approach in inflammatory arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2016;28:297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Perez‐Ruiz F. Treating to target: a strategy to cure gout. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48 Suppl 2:ii9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jansen TL. Treat to target in gout by combining two modes of action. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53:2131–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Neogi T, Mikuls TR. To treat or not to treat (to target) in gout. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:71–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, Bae S, Singh MK, Neogi T, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:1431–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, Barskova V, Becce F, Castañeda‐Sanabria J, et al. 2016 updated EULAR evidence‐based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sivera F, Andrés M, Carmona L, Kydd AS, Moi J, Seth R, et al. Multinational evidence‐based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of gout: integrating systematic literature review and expert opinion of a broad panel of rheumatologists in the 3e initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:328–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schlesinger N, Norquist JM, Watson DJ. Serum urate during acute gout [published erratum appears in J Rheumatol 2009;36:1851]. J Rheumatol 2009;36:1287–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morillon MB, Stamp L, Taylor W, Fransen J, Dalbeth N, Singh JA, et al. Using serum urate as a validated surrogate end point for flares in patients with gout: protocol for a systematic review and meta‐regression analysis. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Taylor WJ, Schumacher HR Jr, Baraf HS, Chapman P, Stamp L, Doherty M, et al. A modified Delphi exercise to determine the extent of consensus with OMERACT outcome domains for studies of acute and chronic gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:888–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gutman AB. The past four decades of progress in the knowledge of gout, with an assessment of the present status. Arthritis Rheum 1973;16:431–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hench PS. The diagnosis of gout and gouty arthritis. J Lab Clin Med 1936;22:48–55. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mandell BF, Yeo A, Lipsky PE. Tophus resolution in patients with chronic refractory gout who have persistent urate‐lowering responses to pegloticase. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20:286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Perez‐Ruiz F, Calabozo M, Pijoan JI, Herrero‐Beites AM, Ruibal A. Effect of urate‐lowering therapy on the velocity of size reduction of tophi in chronic gout. Arthritis Rheum 2002;47:356–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scirè CA, Carrara G, Viroli C, Cimmino MA, Taylor WJ, Manara M, et al. Development and first validation of a disease activity score for gout. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:1530–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. La‐Crette J, Jenkins W, Fernandes G, Valdes AM, Doherty M, Abhishek A. First validation of the gout activity score against gout impact scale in a primary care based gout cohort. Joint Bone Spine 2018;85:323–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chinchilla SP, Doherty M, Abhishek A. Gout Activity Score has predictive validity and is sensitive to change: results from the Nottingham Gout Treatment Trial (Phase II). Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019. E‐pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. De Lautour H, Taylor WJ, Adebajo A, Alten R, Burgos‐Vargas R, Chapman P, et al. Development of preliminary remission criteria for gout using Delphi and 1000Minds consensus exercises. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:667–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sundy JS, Baraf HS, Yood RA, Edwards NL, Gutierrez‐Urena SR, Treadwell EL, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pegloticase for the treatment of chronic gout in patients refractory to conventional treatment: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2011;306:711–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Becker MA, Baraf HS, Yood RA, Dillon A, Vázquez‐Mellado J, Ottery FD, et al. Long‐term safety of pegloticase in chronic gout refractory to conventional treatment. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1469–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maroli AN, Waltrip R, Alton M, Baraf HS, Huang B, Rehrig C, et al. First application of computer‐assisted analysis of digital photographs for assessing tophus response: phase 3 studies of pegloticase in treatment failure gout. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60 Suppl:S1111. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khanna P, Khanna D, Storgard C, Baumgartner S, Morlock R. A world of hurt: failure to achieve treatment goals in patients with gout requires a paradigm shift. Postgrad Med 2016;128:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. De Lautour H, Dalbeth N, Taylor WJ. Outcome measures for gout clinical trials: a summary of progress. Curr Treat Opt Rheumatol 2015;1:156–66. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gaffo AL, Dalbeth N, Saag KG, Singh JA, Rahn EJ, Mudano AS, et al. Brief report: validation of a definition for flare in patients with established gout. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018;70:462–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Taylor WJ, Brown M, Aati O, Weatherall M, Dalbeth N. Do patient preferences for core outcome domains for chronic gout studies support the validity of composite response criteria? [original article]. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:1259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Becker MA, Schumacher HR, Benjamin KL, Gorevic P, Greenwald M, Fessel J, et al. Quality of life and disability in patients with treatment‐failure gout. J Rheumatol 2009;36:1041–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hirsch JD, Terkeltaub R, Khanna D, Singh J, Sarkin A, Shieh M, et al. Gout disease‐specific quality of life and the association with gout characteristics. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 2010;2010:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]