Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the relation between mode of birth and women’s long-term sexual health.

Design

Maternal follow-up of the Danish National Birth Cohort (1996–2002) in 2013–2014 including questions on sexual health. Logistic regression was used to relate registry-based information about mode of birth and perineal tears with data on sexual problems.

Setting

Denmark.

Participants

Of 82 569 eligible mothers in the Danish National Birth Cohort, 43 639 (53%) completed the follow-up. Of these, 37 417 women had a partner, and answered at least one question on sexual health.

Main outcome measures

Self-reported sexual health.

Results

Participants were on average 44 years old, and 16 years after their first birth. The frequency of sexual problems among women with only spontaneous vaginal births, the reference group, was 37%. For women who only had caesarean sections, more problems were reported (OR 1.18; 95% CI 1.09 to 1.28). For women who had a spontaneous vaginal birth subsequent to a caesarean, and for women with only vaginal births who had experienced one or more instrumental vaginal births, the odds of sexual problems did not differ from women with only spontaneous vaginal births (OR 1.00; 95% CI 0.91 to 1.11) and (OR 1.01; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.08), respectively.

Conclusions

These findings indicate that caesarean section does not protect against long-term sexual problems. Rather, vaginal birth, even after caesarean section, was associated with fewer long-term sexual problems.

Keywords: mode of birth, sexual health, caesarean section, perineal tears, Danish National Birth Cohort

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the largest study on mode of birth and long-term sexual health to date with 37 417 participants, allowing for a detailed investigation of the exposure.

Information on mode of birth was obtained from registries, limiting the risk of differential misclassification.

Participation in the maternal follow-up was 53%, which may limit the generalisability of the study.

Chance and residual confounding, including confounding by birth route indication, cannot be ruled out, but the results were stable in sensitivity analyses.

Introduction

Sexual health is an important part of reproductive health1 and quality of life.2 It is influenced by many factors, including women’s reproductive history.3 Short-term studies have shown that mode of birth, and perineal injury are associated with sexual problems up to 18 months’ post partum.3–6 Although the only randomised trial of mode of birth, where one group of women was allocated to planned caesarean section and the other to planned vaginal birth, reported no significant differences after 2 years of follow-up, the point estimates for pain and being unhappy during sex marginally favoured caesarean section.7 There is also a widespread lay belief that caesarean section, perhaps by maintaining vaginal tone, or avoiding perineal injury, might improve sexual function.

The results of longer-term studies are inconsistent.8–12 One found reduced desire in women with previous instrumental birth, and reduced lubrication in women with a history including both caesarean section and vaginal birth.12 Another reported no associations between mode of birth and sexual problems.10 For women with anal sphincter tears, some studies found no effect,9 12 while others observed a higher prevalence of reduced lubrication10 or dyspareunia.11

We investigated the associations between reproductive history and long-term sexual problems in a large cohort of Danish mothers. Our hypotheses were that instrumental vaginal birth would be associated with a higher risk of sexual problems than spontaneous birth whereas caesarean section would not, and that women with birth-induced perineal injuries would have more sexual problems than women without birth-induced perineal injuries.

Methods

Data sources

The study was based on data from the Danish National Birth Cohort.13 14 The cohort enrolled 91 386 women in early pregnancy between 1996 and 2002, about 30% of births in that period.15 The first interview, conducted around week 16 of gestation, included information on health, lifestyle and socio-occupational factors. Participants consented to use of their information from Danish health and social registries. Between December 2013 and December 2014, participants were invited to respond to a questionnaire on physical, mental and sexual health. Altogether, 53% (43 639 women) of eligible mothers participated.16

Under Danish law, ethical permission is not required for public registry-based studies.17

Outcome

The outcome was self-reported sexual health. Participants provided information about whether their sexual needs had been met in the past year, the frequency of sexual activity with a partner, their experience of dyspareunia, vaginismus, insufficient lubrication and difficulty in getting an orgasm. They were also asked about sexual desire, and whether any lack of desire was considered problematic by them or their partner. Questions were adapted from the Danish National Health Survey18 (online supplementary table 1).

bmjopen-2019-029517supp001.pdf (194.6KB, pdf)

Four types of sexual difficulties were dichotomised into the presence or absence of a sexual problem in the past year. Reduced lubrication or difficulty in achieving orgasm were considered a problem if the women had answered that they ‘often’ or ‘always’ had experienced these difficulties during sex with their partner. Dyspareunia was classified by location, at the vaginal introitus (entry dyspareunia) and/or deep in the abdomen (deep dyspareunia), and considered a problem if women reported that they ‘sometimes’, ‘often’ or ‘always’ had either type. In addition, we defined frequent dyspareunia if it was present ‘often’ or ‘always’. Reduced sexual desire was considered a problem if women ’sometimes’, ’often’ or ’always’ experienced it, and also considered it a problem. All four specific sexual problems (reduced lubrication, difficulty in achieving orgasm, dyspareunia and reduced sexual desire) were combined in one outcome, ‘the presence or absence of one or more sexual problems within the past year’.

Exposures

Exposures were mode of birth and perineal tears from the woman’s entire reproductive history. These were obtained from the Danish Medical Birth Registry, which contained data about all live and still births since 1973,19 and from the National Patient Registry, which contained data about all contacts with Danish hospitals since 1977.20 Registry data up to the date the woman answered the follow-up questionnaire were linked to cohort participants through personal identification numbers. Mode of birth was categorised as only spontaneous vaginal births, one or more instrumental vaginal births in women with only vaginal births, only caesarean sections, one or more spontaneous vaginal births after a first caesarean section, instrumental vaginal birth in women who delivered vaginally after a first caesarean section, and caesarean section after vaginal birth.

Data on perineal tears were first kept and stored in Denmark from 1994 using International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision(ICD10). For this study, perineal tears were categorised as no tear, first-degree (ICD10 code O70.0), second-degree (O70.1), third-degree (O70.2) or fourth-degree tear (O70.3), or episiotomy (procedure code KTMD00). During the years, the women from the cohort gave birth, it was common practice to register only sutured tears, and many first-degree tears were left unsutured. No tear and first-degree tears were therefore combined into one category. As fourth-degree tears amount to only 1% of perineal tears, they were combined with third-degree tears in a single category ‘anal sphincter tear’. Data on third-degree and fourth-degree tears analysed separately is available in online supplementary table 2. Anal sphincter tear together with an episiotomy was categorised as the former.

Potential covariates

Covariates were chosen a priori based on a literature review and depicted in directed acyclic graphs21 (online supplementary figure 1). Maternal age at first birth, and calendar year at first birth were obtained from the Medical Birth Registry. Information about socio-occupational status, prepregnant body mass index (BMI), mental and physical health, and smoking and exercise in pregnancy came from the woman’s first interview in the Danish National Birth Cohort, and was thus related to her first childbirth in the cohort. For 51% of participants, this was also their first birth. Socio-occupational status was categorised as high (four or more years of education after high school, or job as manager), middle (skilled manual work, office or service work) or low (unskilled work or unemployment).22 Diseases were defined as those that had been diagnosed by a physician, and included hypertensive disorders, diseases of the heart, thyroid or musculoskeletal system, epilepsy, diabetes, gynaecological diseases and mental illness. Self-assessed health at the first pregnancy, smoking in pregnancy and exercise in pregnancy were categorised as shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by mode of birth

| All (n=37 417) | Mode of birth | ||||||

| Only spontaneous births (n=23 608) | Instrumental vaginal birth, ever (n=5003) | Only c-sections (n=3244) | Spontaneous VBAC (n=2 038) | Instrumental VBAC (n=457) | C-section after vaginal birth (n=3 067) | ||

| Age at first birth, n (%) | |||||||

| <25 | 7140 (19) | 4864 (21) | 775 (15) | 363 (11) | 356 (17) | 75 (16) | 707 (23) |

| 25–29 | 19 839 (53) | 12 758 (54) | 2656 (53) | 1433 (44) | 1144 (56) | 233 (51) | 1615 (53) |

| 30–34 | 8614 (23) | 5063 (21) | 1280 (26) | 1024 (32) | 465 (23) | 125 (27) | 657 (21) |

| ≥35 | 1824 (5) | 923 (4) | 292 (6) | 424 (13) | 73 (4) | 24 (5) | 88 (3) |

| Socio-occupational status, n (%)* | |||||||

| Low | 2233 (6) | 1393 (6) | 265 (6) | 202 (7) | 123 (6) | 28 (7) | 222 (8) |

| Middle | 11 832 (34) | 7444 (34) | 1562 (33) | 1056 (35) | 656 (34) | 133 (31) | 981 (34) |

| High | 21 059 (60) | 13 318 (60) | 2875 (61) | 1779 (59) | 1133 (59) | 269 (63) | 1685 (58) |

| Missing | 2293 | 1453 | 301 | 207 | 126 | 27 | 179 |

| Prepregnant BMI, n (%)* | |||||||

| <18.5 | 1417 (4) | 906 (4) | 196 (4) | 87 (3) | 82 (4) | 26 (6) | 120 (4) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 24 554 (71) | 15 991 (73) | 3275 (70) | 1843 (62) | 1286 (68) | 268 (63) | 1891 (66) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 6405 (18) | 3748 (17) | 899 (19) | 697 (23) | 369 (20) | 93 (22) | 599 (21) |

| ≥30.0 | 2321 (7) | 1249 (6) | 278 (6) | 355 (12) | 150 (8) | 37 (9) | 252 (9) |

| Missing | 2720 | 1714 | 355 | 262 | 151 | 33 | 205 |

| Exercise in pregnancy, min/week, n (%)* | |||||||

| None | 21 156 (60) | 13 137 (59) | 2881 (61) | 1888 (62) | 1149 (60) | 274 (64) | 1827 (63) |

| 1–180 | 11 184 (32) | 7222 (33) | 1475 (31) | 900 (30) | 615 (32) | 122 (28) | 850 (29) |

| >180 | 2826 (8) | 1825 (8) | 348 (7) | 255 (8) | 148 (8) | 33 (8) | 217 (8) |

| Missing | 2251 | 1424 | 299 | 201 | 126 | 28 | 173 |

| Smoking in pregnancy, n (%)* | |||||||

| No smoking | 28 295 (80) | 17 973 (80) | 3774 (80) | 2372 (77) | 1545 (80) | 352 (81) | 2279 (78) |

| Smoking cessation | 3099 (9) | 1892 (8) | 425 (9) | 318 (10) | 173 (9) | 28 (6) | 263 (9) |

| Smoking | 4062 (11) | 2489 (11) | 536 (11) | 378 (12) | 222 (11) | 54 (12) | 383 (13) |

| Missing | 1961 | 1254 | 268 | 176 | 98 | 23 | 142 |

| Self-assessed health, n (%)* | |||||||

| Very good | 19 750 (56) | 12 630 (57) | 2642 (56) | 1631 (53) | 1079 (56) | 228 (53) | 1540 (53) |

| Normal | 14 578 (41) | 9056 (41) | 1963 (42) | 1319 (43) | 798 (41) | 195 (45) | 1247 (43) |

| Not so good | 970 (3) | 576 (3) | 116 (2) | 109 (4) | 47 (2) | 11 (3) | 111 (4) |

| Missing | 2 119 | 1346 | 282 | 185 | 114 | 23 | 169 |

| Presence of disease, n (%)*† | |||||||

| No | 20 305 (58) | 13 105 (59) | 2774 (59) | 1577 (52) | 1095 (57) | 251 (58) | 1503 (52) |

| Yes | 14 855 (42) | 9070 (41) | 1932 (41) | 1468 (48) | 820 (43) | 182 (42) | 1383 (48) |

| Missing | 2257 | 1433 | 297 | 199 | 123 | 24 | 181 |

*Percentage of non-missing values.

†Diseases that, according to the women, had been confirmed by a physician, including hypertensive disorders, diseases of the heart, thyroid or musculoskeletal system, epilepsy, diabetes, gynaecological diseases and mental illness.

BMI, body mass index; C-section, caesarean section; VBAC, vaginal birth after caesarean section.

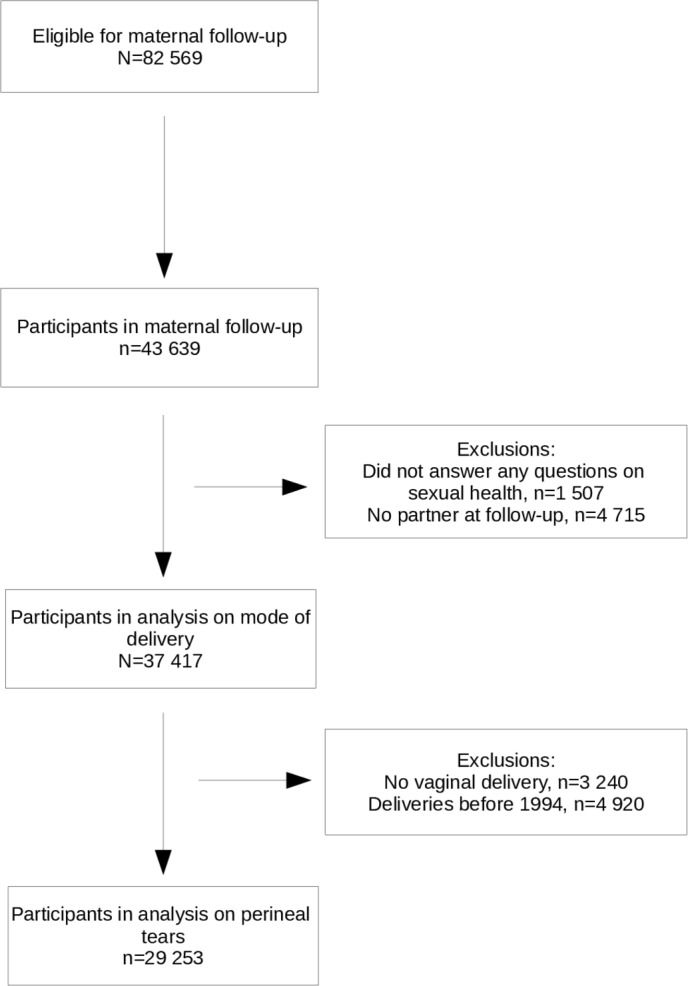

Study population

Women who participated in the follow-up and answered at least one question on sexual health (n=42 132) were eligible. Two separate analyses were done: one for mode of birth and one for degree of perineal tear. Study populations varied slightly in the two analyses (figure 1). For both study populations, we excluded 4715 (11%) women without a partner, as they were not considered comparable with women with a partner when it came to sexual activity and sexual problems. Women without a partner were less sexually active, less likely to feel that their sexual needs were met, and less likely to consider any reduced desire problematic. The sexual health of women with and without a partner can be compared in online supplementary table 1. The study included women with male and/or female partners. In the study population for mode of birth, 37 417 women were included. For the analysis on perineal tears, 3240 women (8%) who only had caesarean sections were excluded. Another 4920 women (12%) with births before 1994, when degree of perineal tear registration started, were excluded, leaving 29 253 women in the study population.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study population.

Participant and public involvement

Some study participants were involved in developing and testing the questionnaire in the maternal follow-up. The results of the research conducted in the Danish National Birth Cohort are available at www.dnbc.dk.

Statistical analysis

To estimate the association between mode of birth, or degree of perineal tear, and the prevalence of sexual problems, we used logistic regression for calculating ORs with 95% CIs. For mode of birth, the reference group was women who had only delivered spontaneously. For perineal tears, the reference group was ‘no tear or first-degree tear’. Multiple logistic regressions were adjusted for age, year at first birth and prepregnant BMI as continuous variables, and socio-occupational status, self-assessed health, disease, exercise and smoking in pregnancy as categorical variables. The number of answers available for analysis for each outcome differed, as the response option ‘I do not wish to answer this question’ was provided for all questions on sexual health, and only participants with complete information on exposure and outcome were analysed. To address missing data on covariates, multivariate imputation by chained equations was done, and the number of datasets created was 20, as no difference in results was seen when moving from 10 to 20 datasets. As recommended by Sterne et al,23 both exposure, outcome and covariates with complete information were included in the imputation model. Complete case analyses were done as well, and the results did not differ substantially from the results based on multiple imputation (online supplementary tables 3 and 4). For non-participants in the maternal follow-up, we also had available data on mode of birth and degree of tear, and the distributions were compared with that observed in participants and found to be similar (online supplementary table 5). Because some categories of mode of birth could only include women with more than one child, the categorisation may be seen as a conditioning on parity or future events. In a sensitivity analysis, we therefore adjusted for parity and year at last birth, even though they were also considered intermediates in the directed acyclic graph. As vaginismus is associated with a lower prevalence of vaginal births, a second sensitivity analysis excluded women with vaginismus. In a third sensitivity analysis, the population was restricted to women who had their first child in the Danish National Birth Cohort, as women who choose to have another child may represent a selected group, where women who have the worst experiences of childbirth, or who have sequelae, are under-represented. All analyses were done using Stata V.13.1 (StataCorp).

Results

The mean age of participants at follow-up was 44 years (SD 4.4), and the mean interval since the women’s first birth to the maternal follow-up 16 years (SD 3.8, range 11–40 years). Socio-occupational status, BMI, and smoking and exercise practice in pregnancy are shown in table 1. Most women, 23 608 (63%), had delivered all of their children spontaneously. For 6359 women (17%), their reproductive history included at least one instrumental vaginal birth, almost all of which were vacuum extractions (99%). Some of these women also had a caesarean section in their reproductive history. In 8806 women (24%), at least one birth had been by caesarean section, and 3244 women (8%) had only caesarean sections.

Of the 36 691 women who answered the question on sexual needs, 25 289 women (69%) felt that their needs had been met completely or almost completely within the past year (online supplementary table 1). Of the 35 710 women who answered all questions on sexual problems, 13 449 (38%) reported one or more sexual problems. Reduced or lacking sexual desire was the most prevalent sexual difficulty, and 7945 women (22%) had experienced reduced desire to an extent that they found problematic for themselves. Reduced desire to an extent that the women felt was problematic for their partner was experienced by 35%.

Mode of birth

Compared with women with only spontaneous vaginal births, there was no evidence for a difference in the prevalence of any sexual problems in women with instrumental vaginal births (table 2). Odds for one or more sexual problems were increased in women who had only delivered by caesarean section (OR 1.18; 95% CI 1.09 to 1.28), in women who had an instrumental vaginal birth after caesarean section (OR 1.35; 95% CI 1.11 to 1.64), and in women who had a caesarean section after vaginal birth (OR 1.10; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.19), but not in women with spontaneous vaginal birth after caesarean section (OR 1.00; 95% CI 0.91 to 1.11). The specific sexual problems that were more prevalent in women with a history of caesarean section were reduced lubrication (OR=1.41, 95% CI 1.24 to 1.60) and dyspareunia (OR=1.78, 95% CI 1.59 to 1.99), including frequent dyspareunia (OR=2.82, 95% CI 2.32 to 3.41) (online supplementary table 6). When asked about the localisation of the pain, ORs for women with only caesarean section were higher for entry dyspareunia (OR=2.76, 95% CI 2.36 to 3.24) than for deep dyspareunia (OR=1.25, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.45).

Table 2.

Sexual problems by mode of birth

| Only spontaneous births | Instrumental vaginal birth, ever | Only c-sections | Spontaneous VBAC | Instrumental VBAC | C-section after vaginal birth | |

| One or more sexual problem(s), n=35 710 | ||||||

| Cases (%) | 8323 (37) | 1788 (37) | 1278 (42) | 718 (37) | 194 (45) | 1148 (39) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.02 (0.96 to 1.09) | 1.24 (1.15 to 1.34) | 1.01 (0.92 to 1.11) | 1.37 (1.14 to 1.66) | 1.11 (1.03 to 1.20) |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Reference | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.08) | 1.18 (1.09 to 1.28) | 1.00 (0.91 to 1.11) | 1.35 (1.11 to 1.64) | 1.10 (1.01 to 1.19) |

| Reduced desire, n=36 509 | ||||||

| Cases (%) | 4981 (22) | 1042 (21) | 723 (23) | 437 (22) | 106 (24) | 656 (22) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.07) | 1.09 (1.00 to 1.19) | 1.03 (0.92 to 1.15) | 1.13 (0.91 to 1.41) | 1.03 (0.94 to 1.13) |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Reference | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.07) | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.15) | 1.03 (0.92 to 1.15) | 1.13 (0.91 to 1.41) | 1.02 (0.93 to 1.11) |

| Difficulty in obtaining orgasm, n=36 019 | ||||||

| Cases (%) | 2861 (13) | 641 (13) | 421 (14) | 255 (13) | 73 (17) | 399 (14) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.07 (0.97 to 1.17) | 1.10 (0.99 to 1.23) | 1.04 (0.91 to 1.20) | 1.39 (1.08 to 1.79) | 1.09 (0.98 to 1.22) |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Reference | 1.06 (0.96 to 1.16) | 1.06 (0.95 to 1.18) | 1.04 (0.91 to 1.19) | 1.38 (1.07 to 1.78) | 1.09 (0.97 to 1.22) |

| Insufficient lubrication, n=36 148 | ||||||

| Cases (%) | 1700 (7) | 383 (8) | 344 (11) | 138 (7) | 46 (10) | 298 (10) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.07 (0.95 to 1.20) | 1.55 (1.37 to 1.76) | 0.94 (0.78 to 1.12) | 1.44 (1.06 to 1.96) | 1.39 (1.23 to 1.59) |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Reference | 1.01 (0.90 to 1.13) | 1.41 (1.24 to 1.60) | 0.92 (0.77 to 1.10) | 1.35 (0.99 to 1.85) | 1.35 (1.18 to 1.54) |

| Dyspareunia, n=36 266 | ||||||

| Cases (%) | 2040 (9) | 446 (9) | 467 (15) | 170 (9) | 57 (13) | 319 (11) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.03 (0.93 to 1.15) | 1.81 (1.62 to 2.02) | 0.96 (0.82 to 1.13) | 1.50 (1.13 to 1.99) | 1.23 (1.09 to 1.40) |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Reference | 1.05 (0.94 to 1.17) | 1.78 (1.59 to 1.99) | 0.97 (0.82 to 1.14) | 1.52 (1.14 to 2.01) | 1.20 (1.06 to 1.36) |

| Entry dyspareunia, n=35 720 | ||||||

| Cases (%) | 640 (3) | 160 (3) | 243 (8) | 68 (4) | 25 (6) | 117 (4) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.19 (1.00 to 1.42) | 2.99 (2.57 to 3.49) | 1.24 (0.96 to 1.60) | 2.09 (1.38 to 3.15) | 1.43 (1.17 to 1.75) |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Reference | 1.14 (0.96 to 1.37) | 2.76 (2.36 to 3.24) | 1.24 (0.96 to 1.59) | 2.03 (1.35 to 3.07) | 1.41 (1.15 to 1.73) |

| Deep dyspareunia, n=35 720 | ||||||

| Cases (%) | 1425 (6) | 278 (6) | 233 (8) | 102 (5) | 36 (8) | 203 (7) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.92 (0.80 to 1.05) | 1.24 (1.07 to 1.43) | 0.82 (0.67 to 1.01) | 1.34 (0.95 to 1.89) | 1.11 (0.95 to 1.29) |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Reference | 0.96 (0.84 to 1.09) | 1.25 (1.08 to 1.45) | 0.83 (0.67 to 1.02) | 1.38 (0.98 to 1.96) | 1.07 (0.91 to 1.25) |

*Adjusted for maternal age at first birth, calendar year at first birth, prepregnant body mass index, socio-occupational status, self-assessed health, disease, exercise in pregnancy and smoking in pregnancy.

C-section, caesarean section; VBAC, vaginal birth after caesarean section.

Among women with one or more vaginal births, 16 404 (56%), had no tear or a first-degree tear (online supplementary table 7). Episiotomy was frequently used in 1997 to 2002, and 6615 women (23%) had a second-degree tear from a mediolateral episiotomy as their largest tear. Anal sphincter tears were seen in 1967 women (7%).

Neither second-degree tears nor episiotomies were associated with increased odds of any of the studied sexual problems (table 3). Women with previous episiotomies had lower odds of deep dyspareunia (OR=0.87, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.99) than women with no tear or a first-degree tear. Women with previous anal sphincter tears had moderately higher odds of reduced lubrication and entry dyspareunia (OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.43, & OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.73, respectively). The latter association was unaltered when frequent dyspareunia was considered (online supplementary table 8).

Table 3.

Sexual problems by degree of perineal tear

| No tear/first degree | Second degree | Episiotomy | Anal sphincter tear | |

| One or more sexual problem(s), n=27 992 | ||||

| Cases (%) | 5882 (37) | 1560 (38) | 2278 (36) | 716 (38) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.04 (0.97 to 1.12) | 0.95 (0.90 to 1.01) | 1.03 (0.93 to 1.14) |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Reference | 1.03 (0.96 to 1.11) | 0.95 (0.90 to 1.01) | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.12) |

| Reduced sexual desire, n=28 586 | ||||

| Cases (%) | 3523 (22) | 935 (22) | 1342 (21) | 423 (22) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.02 (0.94 to 1.11) | 0.94 (0.87 to 1.00) | 1.01 (0.90 to 1.13) |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Reference | 1.01 (0.93 to 1.10) | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.01) | 1.00 (0.89 to 1.12) |

| Difficulty in obtaining orgasm, n=28 217 | ||||

| Cases (%) | 2006 (13) | 553 (14) | 817 (13) | 261 (14) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.08 (0.97 to 1.19) | 1.02 (0.93 to 1.11) | 1.11 (0.96 to 1.27) |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Reference | 1.07 (0.96 to 1.18) | 1.01 (0.93 to 1.11) | 1.09 (0.95 to 1.25) |

| Insufficient lubrication, n=28 308 | ||||

| Cases (%) | 1133 (7) | 314 (8) | 481 (8) | 163 (9) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Reference | 1.08 (0.95 to 1.23) | 1.06 (0.95 to 1.19) | 1.22 (1.03 to 1.45) |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Reference | 1.09 (0.96 to 1.25) | 1.02 (0.91 to 1.14) | 1.2 (1.01 to 1.43) |

| Dyspareunia, n=28 398 | ||||

| Cases (%) | 1469 (9) | 372 (9) | 562 (9) | 184 (10) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.98 (0.87 to 1.10) | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.05) | 1.05 (0.90 to 1.24) |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Reference | 0.97 (0.86 to 1.10) | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.07) | 1.07 (0.91 to 1.25) |

| Entry dyspareunia, n=28 006 | ||||

| Cases (%) | 453 (3) | 115 (3) | 201 (3) | 74 (4) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.98 (0.80 to 1.21) | 1.11 (0.94 to 1.31) | 1.38 (1.08 to 1.78) |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Reference | 0.98 (0.79 to 1.20) | 1.09 (0.92 to 1.30) | 1.34 (1.04 to 1.73) |

| Deep dyspareunia, n=28 006 | ||||

| Cases (%) | 1035 (7) | 265 (7) | 355 (6) | 117 (6) |

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Reference | 0.99 (0.86 to 1.14) | 0.85 (0.75 to 0.96) | 0.94 (0.77 to 1.15) |

| Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | Reference | 0.98 (0.85 to 1.13) | 0.87 (0.77 to 0.99) | 0.97 (0.80 to 1.19) |

*Adjusted for maternal age at first birth, calendar year at first birth, prepregnant body mass index, socio-occupational status, self-assessed health, disease, exercise in pregnancy and smoking in pregnancy.

In sensitivity analyses, adjusting for parity and year at last birth did not change the results (data not shown), and restricting the population to women who had their first birth in the Danish National Birth Cohort only changed the results marginally (online supplementary tables 9 and 10). Vaginismus was rare in this study population (1%), but more prevalent in women who had a history of caesarean section. However, results were not substantially altered when we excluded women with vaginismus (online supplementary table 11).

Discussion

In this large sample of Danish mothers, a history of caesarean section was associated with an increased risk of sexual problems in midlife compared with women who had only delivered vaginally. The estimated effect sizes were small to moderate, but if causative would be clinically important. For example, women who had only given birth by caesarean section had a relative risk of 1.11 of sexual problems in later life. This 11% proportional increase amounts to a five percentage points absolute increase from 37% to 42%. In contrast, instrumental vaginal birth was not associated with long-term sexual problems. Among women who had delivered by caesarean but had a subsequent spontaneous vaginal birth, the risk of long-term sexual problems was similar to those who had only delivered vaginally.

Strengths of this study include study size, and long-term follow-up with linkage to registry data, allowing a detailed investigation of exposures while limiting the risk of differential misclassification. Limitations include a participation rate of 53%. A recent study found that participants in the maternal follow-up were older, and of higher socio-occupational status and healthier lifestyle than non-participants, but also that selected exposure-outcome associations were not substantially affected by selection bias.16 However, the relatively high socio-occupational level of participants could affect generalisability. Residual confounding, including confounding by time-varying factors and confounding by indication, should be considered. A study found lower prevalence of vaginal births in women with vaginismus.24 It is possible that some of the biopsychological mechanisms that cause sexual problems may also alter the likelihood of vaginal birth. Among these mechanisms could be mental or somatic illness, which we adjusted for in our analysis, but also vaginismus prior to childbirth, for which we did not have information. This could draw the results towards an association between caesarean section and more sexual problems. However, caesarean section on maternal request was rare in Denmark in the 1990s and 2000s—less than 2% of all births.25 Results were unchanged when we only considered women who had their first birth in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Finally, chance findings cannot be ruled out.

The prevalence of sexual problems in midlife in the present study is broadly within the range from previous reports. In this study, as in previous studies,10 12 episiotomies were not associated with more sexual problems. Rather, women with episiotomies reported less deep dyspareunia than women with no tears or first-degree tears. Shorter second stages of labour are observed when episiotomy is used5 which might explain why these women have less deep dyspareunia. However, at present our results do not justify a change in the advice on avoiding routine use of episiotomy.26 Some previous studies found no association between anal sphincter tears and long-term sexual problems,9 12 whereas others found increased risk of dyspareunia11 or reduced lubrication10 as we did. Scar tissue and a higher prevalence of incontinence might explain this finding, but the underlying reasons for the tear could also play a role.

Previous studies of long-term sexual health between different modes of birth were small.10 12 The studies were carried out in the USA and in Switzerland, countries with different obstetric traditions from Denmark, and neither found indication that caesarean section protected against sexual problems in the long term.10 12 If the association between caesarean sections and sexual problems identified in this study is causal, there are a number of possible underlying mechanisms. Abdominal adhesions after caesarean section are not likely to be the whole explanation, since this would not explain why women who had delivered by caesarean section also reported more entry dyspareunia, nor why vaginal birth after caesarean section reduces sexual problems. It is possible that expectation of deep dyspareunia can reduce lubrication and heighten the risk of entry dyspareunia. Another explanation could be that the achievement of at least one vaginal birth is protective against sexual problems in later life. This might be a physical effect if, contrary to anecdote, changes to the perineum after vaginal birth are in some way associated with less pain or greater pleasure. There may also be psychosexual benefits from achieving a vaginal birth.

Caesarean section has been proposed as preventive of pelvic floor dysfunctions, such as pelvic organ prolapse, and urinary and anal incontinence.8 The experience of pelvic floor dysfunctions may in turn influence sexual health.3 Therefore pelvic floor dysfunctions can be considered as intermediate factors between mode of birth and sexual health (see online supplementary figure 1). For this reason, we did not adjust for pelvic floor dysfunctions in the analyses. Yet, when discussing long-term effects of mode of birth, knowledge about pelvic floor dysfunctions is important. Caesarean section appears to protect against pelvic organ prolapse in both the short and long term.8 For urinary incontinence, there appears to be a protective effect of caesarean section in the short term. However, as women age, this potential effect is no longer found.8 The current evidence does not support any protective effect of caesarean section on anal incontinence outside the immediate postpartum period.8 These factors should all be taken into account, along with sexual health, when counselling a woman about the choice of mode of birth.

Our findings do not support choosing caesarean section over vaginal birth in order to prevent long-term sexual problems. Instead, vaginal birth appears to be associated with fewer sexual problems, even when it involves instrumental birth, or an episiotomy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all women who participated in the maternal follow-up.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design of the study. JO and EAN were responsible for the data collection. SH analysed the data with help from HK. SH, HK, EAN, JGT and JO interpreted the results. SH wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and EAN, HK, JGT and JO critically revised it. All authors approved the final manuscript. All authors are guarantors.

Funding: The Danish National Birth Cohort was established with a significant grant from the Danish National Research Foundation. Additional support was obtained from the Danish Regional Committees, the Pharmacy Foundation, the Egmont Foundation, the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, the Health Foundation and other minor grants. The Danish Council for Independent Research supported the maternal follow-up.

Disclaimer: The funders of the Danish National Birth Cohort and the maternal follow-up had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. SH and HK had full access to all the data in the study, and all authors had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Under Danish law, ethical permission is not required for public registry-based studies. The Danish National Birth Cohort was initially approved by the Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics (reference no. [KF] 01-471/94) and all participants gave written, informed consent. This study was also approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (approval no. 2014-41-2848).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.

References

- 1. WHO WHO | Reproductive health [Internet]. WHO, 2017. Available: http://www.who.int/topics/reproductive_health/en/ [Accessed cited 2017 Sep 10].

- 2. Flynn KE, Lin L, Bruner DW, et al. Sexual satisfaction and the importance of sexual health to quality of life throughout the life course of U.S. adults. J Sex Med 2016;13:1642–50. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Srivastava R, Thakar R, Sultan A. Female sexual dysfunction in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2008;63:527–37. 10.1097/OGX.0b013e31817f13e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hicks TL, Goodall SF, Quattrone EM, et al. Postpartum sexual functioning and method of delivery: summary of the evidence. J Midwifery Womens Health 2004;49:430–6. 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2004.tb04437.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ejegård H, Ryding EL, Sjögren B. Sexuality after delivery with episiotomy: a long-term follow-up. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2008;66:1–7. 10.1159/000113464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McDonald EA, Gartland D, Small R, et al. Dyspareunia and childbirth: a prospective cohort study. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy 2015;122:672–9. 10.1111/1471-0528.13263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hannah ME, Whyte H, Hannah WJ, et al. Maternal outcomes at 2 years after planned cesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: the International randomized term breech trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:917–27. 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sandall J, Tribe RM, Avery L, et al. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. Lancet 2018;392:1349–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31930-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fornell EU, Matthiesen L, Sjödahl R, et al. Obstetric anal sphincter injury ten years after: subjective and objective long term effects. BJOG 2005;112:312–6. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00400.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Otero M, Boulvain M, Bianchi-Demicheli F, et al. Women's health 18 years after rupture of the anal sphincter during childbirth: II. urinary incontinence, sexual function, and physical and mental health. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194:1260–5. 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.10.796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mous M, Muller SA, De Leeuw JW. Long-Term effects of anal sphincter rupture during vaginal delivery: faecal incontinence and sexual complaints. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2008;115:234–8. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01502.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fehniger JE, Brown JS, Creasman JM, et al. Childbirth and female sexual function later in life. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:988–97. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a7f3fc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olsen J, Melbye M, Olsen SF, et al. The Danish National Birth Cohort - its background, structure and aim. Scand J Public Health 2001;29:300–7. 10.1177/14034948010290040201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Statens Serum Institut About the DNBC - Statens Serum Institut [Internet], 2015. Available: http://www.ssi.dk/English/RandD/Research%20areas/Epidemiology/DNBC/About%20the%20DNBC.aspx [Accessed 3 Mar 2017].

- 15. Nohr EA, Frydenberg M, Henriksen TB, et al. Does low participation in cohort studies induce bias? Epidemiology 2006;17:413–8. 10.1097/01.ede.0000220549.14177.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bliddal M, Liew Z, Pottegård A, et al. Examining Nonparticipation in the maternal follow-up within the Danish national birth cohort. Am J Epidemiol 2018;187:1511–9. 10.1093/aje/kwy002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ministeriet for Sundhed og Forebyggelse Lov om videnskabsetisk behandling af sundhedsvidenskabelige forskningsprojekter [Internet]. LOV nr 593 Jun 14, 2011. Available: https://www.retsinformation.dk/Forms/R0710.aspx?id=137674 [Accessed 3 Jan 2017].

- 18. Christensen AI, Jensen HAR, Ekholm O, et al. Seksuel sundhed. Resultater fra Sundheds- OG sygelighedsundersøgelsen 2013. Denmark: Statens Institut for Folkesundhed, SDU, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Knudsen LB, Olsen J. The Danish medical birth registry. Dan Med Bull 1998;45:320–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thygesen LC, Daasnes C, Thaulow I, et al. Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:12–16. 10.1177/1403494811399956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Glymour MM, Greenland S. Causal Diagrams. In: Modern epidemiology : Philadelphia Baltimore New York London Buenos Aires Hong Kong Sydney Tokyo: Wolters Kluwer health. 3rd edn Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008: 183–209. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nohr EA, Bech BH, Davies MJ, et al. Prepregnancy obesity and fetal death: a study within the Danish national birth cohort. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:250–9. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000172422.81496.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009;338:b2393 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Möller L, Josefsson A, Bladh M, et al. Reproduction and mode of delivery in women with vaginismus or localised provoked vestibulodynia: a Swedish register-based study. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy 2015;122:329–34. 10.1111/1471-0528.12946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Forstholm MM, Lidegaard O. [Cesarean section on maternal request]. Ugeskr Laeger 2009;171:497–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jiang H, Qian X, Carroli G, et al. Selective versus routine use of episiotomy for vaginal birth : Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 10 Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2017. 10.1002/14651858.CD000081.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029517supp001.pdf (194.6KB, pdf)