Abstract

Introduction

The number of patients taking oral chemotherapy is increasing around the world. It is essential to maximise the adherence to oral chemotherapy to improve the overall survival and life expectancy of the patients. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we aim to evaluate the effectiveness of mobile applications in improving the adherence to oral chemotherapy and adjuvant hormonal therapy in cancer survivors.

Methods and analysis

MEDLINE, Embase, LILACS, clinicaltrials.gov, Scopus and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials will be searched for randomised or quasi-experimental studies published between January 2009 and July 2019. This systematic review and meta-analysis will include studies investigating the use of mobile applications by cancer survivors to aid adherence to oral chemotherapy and adjuvant hormonal therapy. Patient education, reminder tools, calendars, pillboxes and electronic reminders will not be evaluated. The primary outcome will be the improvement in adherence to anticancer drugs. The secondary outcomes will be an improvement in the overall survival and life expectancy, improved quality of life and control of cancer-related symptoms. Three independent reviewers will select the studies and extract data from the original publications. The risk-of-bias will be assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. Data synthesis will be performed using the Review Manager software (RevMan V.5.2.3). To assess heterogeneity, we will compute the I2 statistics. Additionally, a quantitative synthesis will be performed if the included studies are sufficiently homogenous.

Ethics and dissemination

This study will be a review of the published data, and thus, ethical approval is not required. Findings of this systematic review will be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42018102172.

Keywords: mobile application, medication adherence, oral anticancer agents, health informatics, patient compliance

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review and meta-analysis aims to combine the results of different studies that have comparable effect sizes and can be computed.

Three reviewers will independently select the eligible studies, extract data without different variables and assess the risk-of-bias.

There is a possibility that we get a small sample size and a limited number of studies; this may influence the validity and reliability of the findings.

Different types of mobile applications may cause considerable heterogeneity that could limit generating convincing conclusions.

Despite these limitations, the findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis may suggest whether mobile applications or other approaches are more useful in improving the adherence to oral chemotherapeutic treatment.

Introduction

Description of the condition

About 25% of the new antineoplastic agents under development are estimated to be oral drugs. Notably, the number of oral chemotherapeutic drugs will be more than doubled over the next few years.1–3 Compared with intravenous therapy, oral therapy is more convenient, faster and easier to administer, and requires fewer clinic visits and hence, preferred by the patients.4 5 Additionally, oral therapy can provide a feeling of control over treatment, reduce the interference of treatment with work and social activities, and eliminate the requirement of travelling to an infusion clinic and the discomfort of inserting an intravenous line.2 Once an antineoplastic agent is ordered, the administration is the responsibility of the patient.5 However, patients and clinicians are facing new challenges in managing adherence to these oral therapies.6

Most patients attempt to adhere to the treatment according to the prescription, nevertheless, adherence continues to be a problem. It is difficult to obtain a reliable estimate of adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies from the literature. This is because the few intervention studies that have been conducted on treatment adherence have notable methodological concerns. Thus, there is limited evidence to promote treatment adherence in patients with cancer.6 Moreover, studies on non-adherence to treatment and pharmacological limitations are inadequate.3

Hershman et al 7 showed that the interventions to enhance the psychosocial well-being of patients should be evaluated to increase treatment adherence. Furthermore, the authors explained that adherence to therapy has been reported to be associated with belief in the efficacy of the drug and with belief in the benefits of taking prescribed drugs; and a high level of cancer-specific emotional distress was associated with subsequent non-adherence to treatment. Another study suggested that poor physician–patient communication, negative feeling regarding the efficacy of the drugs and fear of toxicities were associated with failure to initiate the therapy.6

In a systematic review, Greer et al 6 assessed the interventions to improve adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies in patients with various malignancies. These interventions included educational support, monitoring treatment, pharmacy-based programme, counselling programme, and use of pre-filled pillboxes and automated voice response systems. Nevertheless, most of the studies included in this systematic review had a high risk-of-bias due to non-randomised designs, small sample sizes, subjective assessments of adherence and missing data. In another systematic review of interventions to promote adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies, the investigators drew similar conclusions, as problems non-adherence to treatment.8

A variety of education, symptom management and reminder-based interventions, which involve face-to-face interactions, phone calls and texting short message service (SMS) have been developed and tested. However, the effectiveness of these interventions remains inconclusive.9–11

Description of the intervention

The American Society of Clinical Oncology/Oncology Nursing Society recommends educating patients on the administration of oral chemotherapy.12 This includes the following:

The storage, handling, preparation, administration and disposal of oral chemotherapeutic drugs.

Concurrent anticancer treatment and supportive drugs/measures (when applicable).

Possible drug–drug and drug–food interactions.

A plan for missed doses.12

The oncology nurses can use tools and technology to assist with education, which may promote treatment adherence. In this context, patient education programme and physical devices, such as pillboxes and glowing pill bottles have been developed. Additionally, computer and mobile applications have paved the way for electronic reminders, such as calendars, text messaging, and alarms.5 13 14

Mobile applications are softwares that support a wide range of function of the mobile phone, including television, telephone, video, music, word processing and internet service.15 The first drug reminder application was developed in 2009.5 6 Mobile applications have several advantages compared with other interventions; this include simple and easy use, often in an automated fashion using a computerised programme.6 Thus, mobile applications may be used to encourage healthy lifestyles while monitoring, tracking, collecting, and transmitting data in real-time, facilitating the doctor–patient communication and increasing the cooperation between the patient and health professionals.7

Several techniques may increase treatment adherence, the most effective being behavioural approaches. However, there is no consensus on which behavioural techniques (such as specific goal-setting, self-monitoring and social comparison) are most effective in promoting treatment adherence.7

With the ever-increasing use of smartphones and development of potentially effective behavioural intervention technologies, scientists may be able to collect data in real-time in a real-world setting. Additionally, researchers are able to optimise the delivery of behavioural interventions and collect data with minimal burden to the patient and provider.11 Recently, a review suggested that adopting mobile technologies to deliver accessible interventions could improve health behaviours in patients with cancer.13

Intervention mechanisms

Adherence remains a complicated issue in the treatment of chronic diseases.8–14 16–18 In this context, the benefits of using technology, even in the form of a simple text message, have been recognised.19 This may improve adherence to the prescribed dosage, with an increase in adherence rates ranging from 50% to 67.8%.14 Mobile applications are suitable for delivering various educational and behavioural interventions while enabling caregivers and health professionals to monitor the patients' drug consumption patterns.10

Why it is important to perform this review

The traditional interventions to improve long-term treatment adherence are complex and not widely used. There is a widespread need for innovations that would provide convenient and feasible techniques to help patients remain adherent to the treatment.18

Currently, the average rate of non-adherence to oral anticancer therapy is estimated to be around 21%.4 This demonstrates that poor adherence is a barrier to completing the treatment.18 19 Non-adherence is complex and systemic; moreover, when at home, there is no professional method to know whether patients are correctly taking the drugs as prescribed. Oral regimens may be associated with complicated dosing schedules; additionally, due to food–drug interactions treatment adherence may become difficult. In busy clinics, patients may be given documents about the new drug(s); however, the time available for one-on-one interaction may not be sufficient.5 Ensuring patient adherence to a treatment that involves self-administration is a challenge faced by healthcare providers.2 20 Many factors can affect treatment adherence: lack of understanding regarding proper administration, complex dosing regimens, administration of other potentially interacting drugs, the timing of drug doses with respect to food intake, cost of the drug and unpleasant side effects. Furthermore, common health conditions of the patients, such as visual and cognitive impairment, memory deficits or forgetfulness can pose additional difficulties.2

Poor adherence has been linked to successive hospitalisation, increased need for medical interventions, morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, non-adherence results in increased healthcare costs, with North America having estimates of approximately $100 billion being spent annually and $2000 spent per patient per year for additional visits to the physician.19 It is necessary to verify if the use of mobile applications can help the patients to overcome these difficulties and improve treatment adherence. Despite the increased use of oral chemotherapy, the number of studies addressing the issue of adherence remains surprisingly low.20

Objectives

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to evaluate the effectiveness of mobile applications in improving adherence to oral chemotherapy and adjuvant hormonal therapy in cancer survivors.

Methods and analysis

This protocol is registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)21 guidelines were used to design this systematic review protocol.

Inclusion criteria

This systematic review will include the following studies: those with randomised or quasi-experimental designs; those that include patients aged >18 years and those that evaluate the use of mobile applications by cancer survivors for adherence to oral chemotherapy and adjuvant hormonal therapy. There will be no language restrictions while selecting the studies.

Patient, intervention, comparison and outcome strategy

Patient: those undergoing oral chemotherapy or adjuvant hormonal therapy.

Intervention: use of mobile applications.

Comparator/control: no use of mobile applications.

Outcome: improvement adherence to anticancer treatment.

Types of patients

Studies where the patients are aged >18 years, diagnosed with cancer, undergoing oral chemotherapy or adjuvant hormonal therapy, and using mobile applications to improve treatment adherence will be included in this systemic review.

Type of interventions

Studies that compare the use of mobile applications with a concurrent control group to evaluate treatment adherence will be included in this systemic review.

Type of outcome measures

Non-adherence may lead to additional treatment costs due to the increased frequency of hospitalisation and medical appointments, recurrence of symptoms and consequent increase in drug toxicity caused by an overdose (to make up for the missed dose).4 22–25

The primary outcome will be to assess the improvement in treatment adherence.17 The secondary outcomes will be to assess the improvement in overall survival and life expectancy, improved quality of life and control of cancer-related symptoms.9–11

Patient and public involvement

This is a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis; the research will be conducted based on a wide and comprehensive literature search from relevant databases; the individual patient data will not be included. Thus, patients will not be involved while setting the search terms, in determining outcome measures, implementing study design and analysing the results.

Search strategy

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, clinicaltrials.gov, Medline, Literatura latino-americana e do Caribe em Ciencias da Saúde (LILACS), Scopus and Embase will be used to search for articles published between January 2009 and July 2019. We selected the publications starting from January 2009 because the first drug reminder application was developed in 2009.5 6

The medical subject headings (MESH) terms will be: (antineoplastic agents OR oral anticancer agents OR drug therapy) AND (mobile application OR mobile apps OR app OR smartphone OR health informatics OR mobile health) AND (medication adherence OR patient empowerment OR treatment adherence and compliance) (table 1).

Table 1.

Medline search strategy

| Search items | |

| 1 | Antineoplastic agents |

| 2 | Oral anticancer agents |

| 3 | Drug therapy |

| 4 | OR/1–3 |

| 5 | Mobile application |

| 6 | Mobile apps |

| 7 | Smartphone |

| 8 | Health informatics |

| 9 | Mobile health |

| 10 | OR/5–9 |

| 11 | Medication adherence |

| 12 | Patient participation |

| 13 | Patient compliance |

| 14 | Treatment adherence and compliance |

| 15 | Medication therapy management |

| 16 | OR/11–15 |

| 17 | 4 AND 10 AND 16 |

Eligible studies will also be selected from the reference lists of the retrieved articles.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

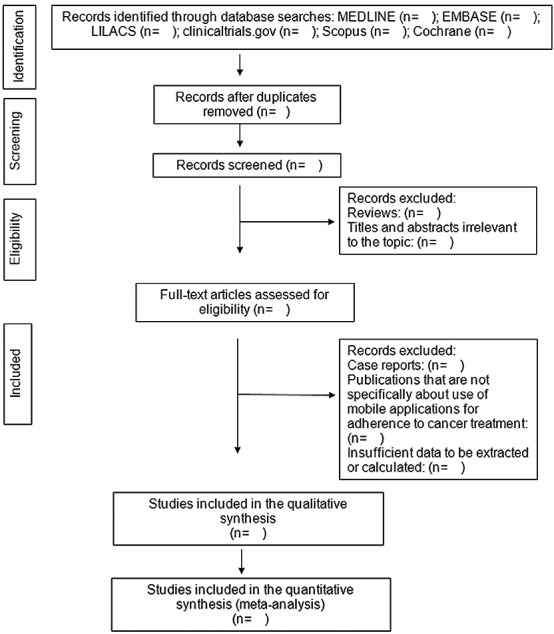

Three authors, KSM, WAC and JFQ, will independently screen the search results using the titles and abstracts. Duplicate studies and reviews will be excluded. Two reviewers, KSM and MNM, will then go through the full text to determine whether the studies meet the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies will be resolved by a third reviewer, AKG. The selection of the studies is summarised in a PRISMA flow diagram (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram. Flow diagram of the search for eligible studies in the use of mobile applications for adherence tocancer treatment: CENTRAL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials.

Data extraction and management

Various characteristics of the eligible studies will be extracted, including the first authors’ last names, year of publication, location of the study (country), study design, primary objective, population, sample size, follow-up period, inclusion/exclusion criteria, type of mobile application used, type of control and primary results. Standardised data extraction forms will specifically be created for this review and the results will be subsequently entered into a database. All data entries will be double-checked.

Addressing missing data

We will attempt to obtain any missing data by contacting the first or corresponding authors or coauthors of an article via phone, email or post. If we fail to receive any necessary information, the data will be excluded from our analysis and will be addressed in the discussion section.

Risk-of-bias assessment

Three authors, KSM, JFQ and BS, will independently assess the risk-of-bias in the eligible studies using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool.25 The modified Cochrane Collaboration tool will be used to assess the risk-of-bias. Bias is assessed as a judgement (high, low or unclear) for individual elements from five domains (selection, performance, attrition, reporting and other).

Assessment of heterogeneity

The heterogeneity between study results will be evaluated using a standard χ2 test with a significance level of p<0.1. To assess heterogeneity, we plan to compute the I2 statistic, which is a quantitative measurement of inconsistency across studies. A value of 0% indicates no heterogeneity, whereas I2 values≥50% indicate a substantial level of heterogeneity; however, heterogeneity will be assessed only if it is appropriate to conduct a meta-analysis.

Analysis

Data will be entered into the Review Manager software (RevMan5.2.3). This software allows the user to enter protocols; complete reviews; include text, characteristics of the studies, comparison tables and study data; and perform meta-analyses. For dichotomous outcomes, we will extract or calculate the OR and 95% CI for each study. In case of heterogeneity (I2 ≥50%), the random-effects model will be used to combine the studies to calculate the OR and 95% CI, using the DerSimonian-Laird algorithm in the meta for package, which provides functions for conducting meta-analyses in R.

Other study characteristics and results will be summarised narratively if the meta-analysis cannot be performed for all or some of the included studies. Sensitivity analyses will be used to explore the robustness of the findings regarding the study quality and sample size. This is only possible if we can conduct a meta-analysis. Sensitivity analyses will be shown in a summary table.

Grading quality of evidence

For grading the strength of evidence from the included data, we will use the Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development, and Evaluation approach. The summary of the assessment will be incorporated into broader measurements to ensure the judgement on the risk-of-bias, consistency, directness and precision.26

Discussion

Non-adherence to cancer treatment is a very common and relevant clinical problem, with a significant adverse impact on the healthcare system. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we aim to determine the effect of mobile applications on the improvement of treatment adherence in cancer survivors. In theory, mobile applications can improve adherence to anticancer treatment, because they can remind the patient to take the medicine on time and assist in care management.27 28 We expect that our study will provide accurate data to develop effective strategies for adherence to anticancer treatment and help to improve our understanding of the role of mobile applications in this context.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not required because this systematic review will use the published data. Findings of this systematic review will be published in a peer-reviewed journal and will be updated if there is enough new evidence to change the conclusions of the systematic review.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance provided by the Graduate Program in Health Sciences of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN) in conducting the literature search.

Footnotes

Contributors: KSM, BS and AKG designed this systematic review and meta-analysis. KSM drafted the manuscript, and AKG revised it. KSM, RNC and AKG developed the search strategies and KSM, JFQ and MNM will implement it. KSM, MNM, JFQ and WAC will track potential studies, extract data and assess the quality; in case of disagreement between the authors, AKG will advise on the methodology and will be the referee. RNC will complete the data synthesis. All authors have approved the final version of this manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Weingart SN, Flug J, Brouillard D, et al. . Oral chemotherapy safety practices at US cancer centres: questionnaire survey. BMJ 2007;334 10.1136/bmj.39069.489757.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wood L. A review on adherence management in patients on oral cancer therapies. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2012;16:432–8. 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moody M, Jackowski J. Are patients on oral chemotherapy in your practice setting safe? Clin J Oncol Nurs 2010;14:339–46. 10.1188/10.CJON.339-346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chabrier M, Bezy O, Mouret M-A, et al. . Impact of depressive disorders on adherence to oral anti-cancer treatment. Bull Cancer 2013;100:1017–22. 10.1684/bdc.2013.1824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burhenn P, Smudde J. Using tools and technology to promote education and adherence to oral agents for cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2015;19:53–9. 10.1188/15.S1.CJON.53-59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Greer JA, Amoyal N, Nisotel L, et al. . A systematic review of adherence to oral antineoplastic therapies. Oncologist 2016;21:354–76. 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Hillyer GC, et al. . Psychosocial factors related to non-persistence with adjuvant endocrine therapy among women with breast cancer: the breast cancer quality of care study (BQUAL). Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016;157:133–43. 10.1007/s10549-016-3788-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mathes T, Antoine S-L, Pieper D, et al. . Adherence enhancing interventions for oral anticancer agents: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev 2014;40:102–8. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ali EE, Chan SSL, Leow JL, et al. . User acceptance of an app-based adherence intervention: perspectives from patients taking oral anticancer medications. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2019;25:390–7. 10.1177/1078155218778106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ali EE, Chan SSL, Poh HY, et al. . Design Considerations in the Development of App-Based Oral Anticancer Medication Management Systems: a Qualitative Evaluation of Pharmacists’ and Patients’ Perspectives. J Med Syst 2019;43:63 10.1007/s10916-019-1168-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fishbein JN, Nisotel LE, MacDonald JJ, et al. . Mobile application to promote adherence to oral chemotherapy and symptom management: a protocol for design and development. JMIR Res Protoc 2017;6:e62 10.2196/resprot.6198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Neuss MN, Polovich M, McNiff K, et al. . 2013 updated American Society of clinical Oncology/Oncology nursing Society chemotherapy administration safety standards including standards for the safe administration and management of oral chemotherapy. J Oncol Pract 2013;9:5s–13. 10.1200/JOP.2013.000874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Darlow S, Wen K. Development testing of mobile health interventions for cancer patient self-management: a review. Health Informatics J 2015;27:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jacobs JM, Pensak NA, Sporn NJ, et al. . Treatment satisfaction and adherence to oral chemotherapy in patients with cancer. JOP 2017;13:e474–85. 10.1200/JOP.2016.019729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Medicine, U.S. National library of medicine. Medical subject Headings: mobile applications, 2018. Available: <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/68063731> [Accessed 16 Mar 2019].

- 16. Elliott M, Liu Y. The nine rights of medication administration: an overview. Br J Nurs 2010;19:300–5. 10.12968/bjon.2010.19.5.47064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zerillo JA, Goldenberg BA, Kotecha RR, et al. . Krzyzanowska MK interventions to improve oral chemotherapy safety and quality: a systematic review. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:105–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Makubi A, Sasi P, Ngaeje M, et al. . Rationale and design of mDOT-HuA study: a randomized trial to assess the effect of mobile-directly observed therapy on adherence to hydroxyurea in adults with sickle cell anemia in Tanzania. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016;16:140 10.1186/s12874-016-0245-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thakkar J, Kurup R, Laba T-L, et al. . Mobile telephone text messaging for medication adherence in chronic disease. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:340–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barillet M, Prevost V, Joly F, et al. . Oral antineoplastic agents: how do we care about adherence? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015;80:1289–302. 10.1111/bcp.12734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shimada CS. Adherence to treatment with oral medications. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ruddy K, Mayer E, Partridge A. Patient adherence and persistence with oral anticancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;59:56–66. 10.3322/caac.20004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jin J, Sklar GE, Min Sen Oh V, et al. . Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: a review from the patient's perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2008;4:269–86. 10.2147/tcrm.s1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. . The Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Cochrane bias methods group; Cochrane statistical methods group. BMJ 2011;343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. . Grade guidelines: 3. rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:401–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jupp JCY, Sultani H, Cooper CA, et al. . Evaluation of mobile phone applications to support medication adherence and symptom management in oncology patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2018;65:e27278 10.1002/pbc.27278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Carmody JK, Denson LA, Hommel KA. Content and usability evaluation of medication adherence mobile applications for use in pediatrics. J Pediatr Psychol 2019;44:333–42. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsy086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.