Abstract

Objectives

To use wrist-worn accelerometers (Axivity AX3) to establish normative physical activity (PA) and acceptability data for the high-risk elderly preoperative population, to assess whether PA could be modified by a prehabilitation intervention as part of routine care, to assess any correlation between accelerometer-measured PA and self-reported PA and to assess the acceptability of wearing wrist-worn accelerometers in this population.

Study design

Prospective, observational, pilot study.

Setting

Single National Health Service Hospital.

Participants

Frail patients≥65 years awaiting major surgery referred to a multidisciplinary preoperative clinic at which they received a routine intervention aimed at improving their PA. 35 patients were recruited. Average age 79.9 years (SD=5.6).

Primary outcomes

Normative PA data measured as a mean daily Euclidean norm minus one (ENMO) in milli-gravitational units (mg).

Secondary outcomes

Measure PA levels (mg) following a routine preoperative intervention. Determine correlation between patient-reported PA (measured using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly) and accelerometer-measured PA (mg). Assess acceptability of wearing a wrist-worn accelerometer measured using Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) questionnaire and device wear time (hours).

Results

Median baseline daily PA was 14.3 mg (IQR 9.75–22.04) with an improvement in PA detected following the intervention (median ENMO post intervention 20.91 mg (IQR 14.83–27.53), p=0.022). There was no significant correlation between accelerometer-measured and self-reported PA (baseline ρ=0.162 (p=0.4), post intervention ρ=−0.144 (p=0.5)). We found high acceptability ratings (median score of 10/10 on VAS, IQR 8–10) and wear-time compliance (163.2 hours (IQR 150–167.5) preintervention and 166.1 hours (IQR 162.5–167) post intervention).

Conclusions

Accelerometery is acceptable to this population and increases in PA levels measured following an unoptimised routine clinical intervention which indicates that health behavioural change interventions may be successful during the preoperative period. Accelerometers may therefore be a useful tool to design and validate interventions for improving PA in this setting.

Trial registration number

Keywords: adult anaesthesia, surgery, elderly, perioperative medicine, physical activity, wearable technology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to look at the use of wearable accelerometers to measure and characterise physical activity in high-risk elderly patients in the preoperative period.

We present a robust and objective method of measuring physical activity levels and compared this to self-reporting methods of measuring physical activity.

We were able to assess the impact of an existing unoptimised preoperative intervention using accelerometery.

Limitations of this study include small sample size although this is justified by the fact that it was an initial pilot study to establish normative physical activity and acceptability data to facilitate power calculations for further studies.

Introduction

The ‘high-risk’ surgical population is characterised by advanced age, frailty and multiple comorbidities particularly when undergoing major surgery. This population accounts for just 12.5% of surgical procedures, but over 80% of perioperative deaths in the UK.1 With an ageing population, increasing numbers of high-risk patients require surgery. It is therefore important to improve our understanding of risk factors for perioperative complications in order to facilitate shared decision-making and appropriate planning of perioperative care.

Frailty status is an independent predictor of postoperative morbidity and mortality2 3 and physical inactivity is a defining feature of frailty. Older adults spend a significant part of their day being sedentary4 and do not meet current physical activity (PA) recommendations.5 6 Increased PA can slow progression to a frail state7 and there is growing evidence for the positive association between preoperative PA and perioperative outcomes.8 Prehabilitation programmes incorporate optimisation of medical, nutritional and psychological status alongside prescribed exercise training programmes with specific goals of muscle strengthening and increased physical fitness, but are labour intensive and most have suboptimal participant adherence rates.9 PA may also be an attractive prehabilitation target although it is currently not known whether improving PA is feasible or leads to improvements in outcome.

Sustained changes in habitual, environmentally cued health behaviours are notoriously difficult to achieve,10 but it is plausible that the preoperative period, due to the well-defined target endpoint (surgery), may represent a unique teachable moment during which motivation to convert intention into action may be elevated, and a sustained change in behaviour may be more achievable than other settings. Thus, it may be possible to influence patient behaviours in order to reduce perioperative risk and improve outcomes.

Since the high-risk surgical group is likely to differ from the general population, normative PA data and patient acceptability data are lacking and this needs to be established before targeted intervention studies can be designed. To this end, it is critical to first have a robust, precise method of measuring PA and to understand PA related to daily routine in order to establish a baseline against which the impact of future interventions could be measured. Traditionally, in the perioperative setting, patients’ PA levels have been evaluated using brief self-report questionnaires; however, these are prone to error and recall bias.11 The gold standard method of direct observation is labour intensive and time consuming, and therefore not feasible for widespread use.12 Accelerometers could offer a potential solution; triaxial accelerometers detect magnitude and direction of acceleration and have been used in large-scale epidemiological studies to provide a valid estimate of overall PA.13 They are unobtrusive and non-invasive and can measure PA in free-living environments and may offer a means to assess the efficacy and therefore optimise interventions to improve PA. However, this first requires the specific population of interest to be characterised. Although wrist-worn accelerometery has been validated to measure PA in older patients,13 to our knowledge wearable accelerometers have not previously been used to characterise PA in a high-risk elderly population in the preoperative period. Furthermore, the acceptability of PA measurement has not been established in these patients.

Through this pilot study, we aimed to characterise PA levels in relation to daily routine across a variety of surgical specialties in order to obtain normative data to inform sample size calculations for future intervention studies. We also sought to assess whether there was a change in PA following current preoperative interventions (which form part of usual care in our centre) and quantify the variability of that change. We set out to quantify the correlation between objectively measured and self-reported PA in this patient group. Finally, as accelerometers have not previously been used in this setting, we aimed to assess how acceptable it is to use wrist-worn accelerometers to measure PA in high-risk elderly patients in the preoperative period prior to rolling them out into a larger scale programme of research.

Methods

Study approvals and population

This study was conducted at Cambridge University Hospitals National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All patients awaiting high-risk surgery are seen in a nurse-led preoperative assessment clinic (outpatient setting) as part of routine care, at which point they undergo frailty screening and may be referred to the ‘perioperative review informing management of elderly patients’ (PRIME) clinic (a multidisciplinary clinic specifically designed to optimise frail elderly patients preoperatively). Inclusion criteria for this study were patients referred to the PRIME clinic, participants must have had capacity to consent and complete activity questionnaires and be willing and able to wear the accelerometer around their wrist. PRIME clinic referral criteria were patients listed for major or complex surgery who were aged ≥65 years and either had a Rockwood Clinical Frailty Scale14 score (CFS) of ≥4 or had a clinical picture that gave the preassessment nurse enough concern to refer for a multidisciplinary preoperative assessment. Referral to, and attendance at the PRIME clinic formed part of usual preoperative care at our institution. Participants were excluded from the study if they did not meet the inclusion criteria, they refused to participate or their PRIME clinic appointment was scheduled <72 hours after referral for recruitment, as previous research has shown a minimum period of 72 hours of continuous accelerometer wear time is required to produce valid data.13 Recruitment took place between July and December 2018.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) was sought during the study design process with the aim of ensuring that the research question was agreed to be important, the methods and running of the study were likely to be acceptable to patients and the documents were written appropriately for the target study population. Study documents including patient information leaflets, consent forms and information posters were circulated to Cambridge University Hospital PPI panel for review. Feedback from the PPI panel allowed us to construct more lay-friendly documents. The PPI panel considered the burden of intervention and time required to participate in research. We will consider further PPI involvement in order to disseminate the study results to those participants who requested to be informed.

Accelerometer and data collection

Participants wore a waterproof triaxial accelerometer (Axivity AX3, Newcastle, UK15) which has been used in other studies of functionally impaired people.16 The device was worn around the wrist for 24 hours per day, for 7 days prior to their PRIME clinic visit and 7 days immediately after their PRIME clinic visit. Participants wore the device around their preferred wrist for convenience and to maximise compliance. Participants were instructed by the research team how to refit the accelerometer should they remove it for any reason. Accelerometer devices were programmed to commence data collection on the same day that the device was fitted and to record for 7 days. The accelerometer measures acceleration in three axes sampled at 100 Hz with a dynamic range of ±8 g.

Raw accelerometery data were downloaded and visually inspected in order to detect any accelerometer technical issues, to ensure that the accelerometer was worn and recorded for the correct duration and had recorded the signals as expected. Data analyses were performed in R-package GGIR, the details of which have been previously described.17

PA-related acceleration was calculated using autocalibrated Euclidian norm minus one (ENMO).18 The values presented are the average ENMO for all of the available data normalised per 24 hours cycle (diurnally balanced), with invalid data imputed using the average at similar time points on different days of the week. We chose to use ENMO as our measure of PA since previously published cut-offs for mild/moderate/vigorous intensity PA may not apply to this patient population.

The PRIME clinic visit involves a preoperative review by an anaesthetist, geriatrician, physiotherapist and occupational therapist. During this clinic visit, patients were provided with a behavioural change intervention as part of usual perioperative care at our institution (see the Behavioural change intervention section). At the PRIME clinic visit, a member of the research team retrieved the accelerometer worn by participants for the initial 7-day period and provided the participant with a new device for the second 7-day period. Participants completed two questionnaires at the PRIME clinic visit: a validated self-reported activity questionnaire; Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE),19 and a locally designed acceptability questionnaire (see the Assessment of acceptability section). Participants were asked to repeat the PASE questionnaire at the end of the second 7-day wear period and return the accelerometer and completed PASE questionnaire back to the study centre in a prepaid envelope.

Assessment of acceptability

Overall acceptability was assessed using a participant completed questionnaire using a Visual Analogue Scale from 0 to 10, 0 being ‘very unacceptable’ and 10 being ‘very acceptable’. We also measured the length of time that the devices were worn in hours (wear-time compliance).

Behavioural change intervention (PRIME clinic visit)

The behavioural change intervention (given as part of usual care) consisted of PA and exercise advice described as follows according to the template for intervention description and replication checklist.20 The goals of the intervention were to improve PA levels on a day-to-day basis through activities of daily living (ADLs) or leisure activities, to improve specific aspects of fitness, perioperative respiratory function and promote independence with personal and domestic ADLs and leisure activities. Verbal and written advice was provided as follows: two generic exercise leaflets (general exercises for the whole body, and walking exercises), bespoke exercise programmes (generated using online Physiotools21 software) and local hospital-specific respiratory exercise information leaflets were provided along with advice and information about appropriate community services. The intervention was administered by an NHS band seven physiotherapist with a background in surgery and elderly rehabilitation and an NHS band seven occupational therapist with a background in surgery, orthopaedics and elderly rehabilitation via one face-to-face session (PRIME clinic visit) lasting 40 min. The information described above was given to participants in the PRIME clinic room with the expectation that they would undertake the activities in their own homes. The intervention was tailored to each participant, depending on presentation and planned surgical procedure. Advice given to participants was decided by experienced clinicians in the PRIME clinic and was based on their clinical judgement following a comprehensive assessment. Personalised exercise programmes were designed by the physiotherapist during the clinic visit and taught to participants during this session, with a written information leaflet given to the participant to take home. Adherence to this intervention was not otherwise assessed.

Statistical analysis

We generated descriptive statistics for the number of participants, wear time in hours and average daily ENMO milligravitational units (mg). We analysed the difference in ENMO before and after the existing intervention using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. We also analysed ENMO stratified into orthopaedic and non-orthopaedic surgical populations.

Since accelerometery and self-reported PA (measured using PASE) are continuous variable, we analysed correlation using the Pearson correlation coefficient.

Statistical analysis was conducted using the R statistical language.22 Mixed-effect models were constructed using the lme4 package23; significance testing was done using analysis of deviance. A statistical significance level of 5% was assumed throughout and no correction for multiple comparisons was made.

Results

Thirty-six patients were invited to take part in the study, of which 35 participants were recruited, 19 (54%) were women. Twenty participants (57%) were listed for orthopaedic surgery, 7 (20%) gastrointestinal surgery, 5 (14%) urological surgery and 1 each for vascular, gynaecology and breast surgery. The mean age was 79.9 years (SD=5.6 years). Characteristics of the study population are given in table 1. Our study was not powered to fully define the spectrum of comorbidities in this group. Instead, we summarised physical status in terms of the American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status classification score which is widely used for perioperative risk assessment. Median nurse-assessed Rockwood CFS was 5 (IQR 4–5).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population, values are mean (SD), number (proportion)

| Characteristics of study sample (n=35) | Value |

| Age; years | 79.9 (5.6) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 19 (54%) |

| Male | 16 (46%) |

| Rockwood Clinical Frailty Score | |

| 3 | 1 (2.9%) |

| 4 | 12 (34.3%) |

| 5 | 17 (48.6%) |

| 6 | 5 (14.3%) |

| Surgical specialty | |

| Orthopaedic | 20 (57%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 7 (20%) |

| Urology | 5 (14%) |

| Gynaecology | 1 (3%) |

| Vascular | 1 (3%) |

| Breast | 1 (3%) |

| ASA score* | |

| 2 | 8 (23%) |

| 3 | 27 (77%) |

*ASA, American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status classification system score.

Accelerometery data were available for analysis for 34 participants before the intervention and 30 participants after the intervention. Data from one preintervention participant were unavailable due to an accelerometer programming error, and three participants were withdrawn from the postintervention part of the study because their surgical procedure was scheduled to be <72 hours after the PRIME clinic visit; thus, participants would not have been able to wear the device for the minimum required time of 72 hours. One participant was withdrawn from the postintervention part of the study due to skin irritation around the wrist strap (notably similar irritation was also caused by their own wristwatch), and one participant was withdrawn due to an area of bruising around the wrist strap. This participant was taking oral anticoagulants.

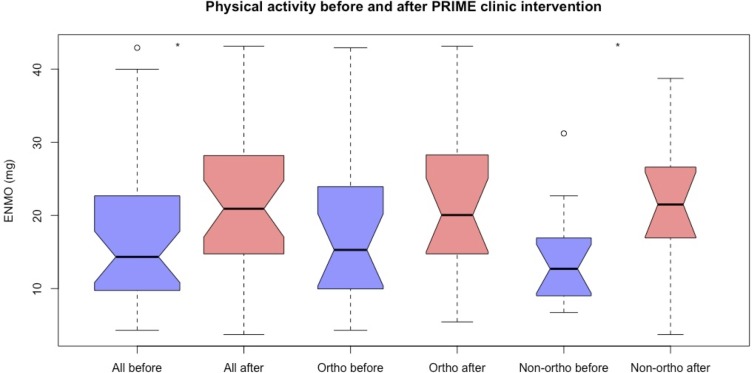

Preoperative baseline PA levels were obtained in 34 participants. The median baseline daily PA level was 14.3 mg (IQR 9.75–22.04). There was no significant difference in baseline median PA between men (12.6 mg (IQR 9.5–15.7)), and women (16.9 mg (IQR 12.5–23.9)), p=0.18). Median baseline daily PA in orthopaedic patients was 15.3 mg (IQR 10.1–23.5), compared with a median of 12.7 mg (IQR 9.2–16.6) in non-orthopaedic patients (p=0.271) as shown in figure 1. Baseline PA was higher in women than men in this orthopaedic subgroup (22.84 mg vs 10.17 mg, p=0.046).

Figure 1.

Notched box plots representing physical activity (Euclidian norm minus one (ENMO), milligravitational units mg) before (blue) and after (red) the perioperative review informing management of elderly patients (PRIME) clinic intervention in all participants (left), participants listed for orthopaedic surgery (middle) and non-orthopaedic surgery (right). Open circle (o) represents outliers. The notch represents the 95% CI of the median; 95% CI that the medians differ if two boxes’ notches do not overlap. Significant differences between ‘before-’, and ‘after-’ intervention groups are indicated with an asterisk (*).

There was a significant increase in overall daily ENMO after the standard clinical intervention (median baseline ENMO 14.3 mg (IQR 9.75–22.04), median ENMO postintervention 20.91 mg (IQR 14.83–27.53), p=0.022) as shown in figure 1. There was no significant difference in ENMO before and after the intervention in patients awaiting orthopaedic surgery (median baseline ENMO 15.29 mg (IQR 10.07–23.5), median ENMO postintervention 20.05 mg (IQR 14.83–27.61), p=0.304). However, in those participants listed for non-orthopaedic surgery, there was a significant increase in mean PA following the intervention (median baseline ENMO 12.71 mg (IQR 9.20–16.61), median ENMO post intervention 21.49 mg (IQR 18.04–25.82), p=0.019); see figure 1.

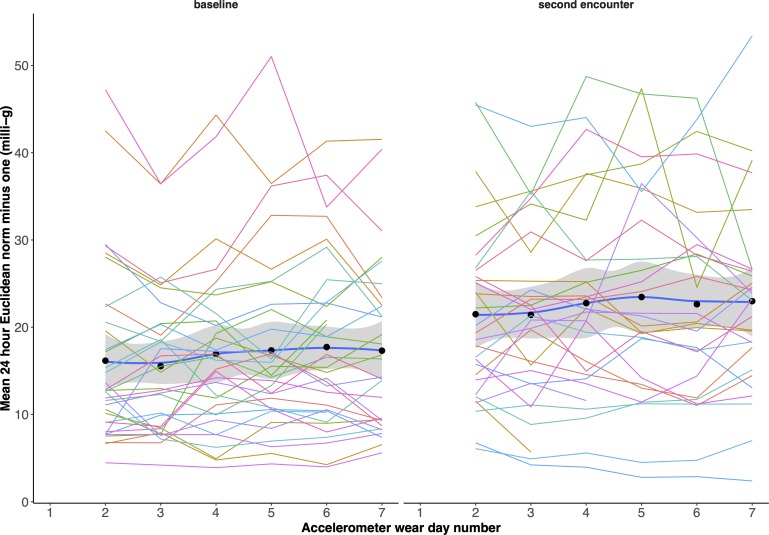

The distribution of PA over time for all patients is shown in figure 2 for both preintervention and postintervention. There was evidence for a linear increase (mixed-effect model) in PA over time in the preintervention group +0.28 mg/day (95% CI 0.011 to 0.53, p=0.04) with a similar finding in the postintervention group +0.15 mg/day (95% CI −0.19 to 0.50, p=0.37), although not achieving statistical significance. There was no evidence for a significant effect of whether the day was a weekend or not, nor was there evidence for a nonlinear time dependency.

Figure 2.

Physical activity (ENMO) against time before (left panel) and after (right panel) the intervention for each patient. The dots/blue lines represent the mean across the patient group with ±1 SD shaded. Only complete (2–6) days included. Mean physical activity is increased after the intervention with no discernible decline in activity over time.

There was no significant difference in self-reported PASE scores before and after the PRIME clinic intervention (median PASE preintervention was 67 (IQR 31–89.75), median PASE postintervention was 65 (IQR 45.5–101) p=0.247). Furthermore, no significant statistical correlation was found between the accelerometer-measured PA and the self-reported PA measured using the PASE questionnaire, either before or after the intervention (baseline ρ=0.162 (p=0.4), postintervention ρ=−0.144 (p=0.5)).

The median wear time of the wrist-worn accelerometer was 163.2 hours (IQR 150–167.5) preintervention and 166.1 hours (IQR 162.5–167) postintervention. On average, participants wore the accelerometers for 98% of the measurement period indicating excellent wear-time compliance, with values comparable to those achieved in other studies.13 Thirty-three participants completed the acceptability questionnaire, and the median overall acceptability score obtained was 10 (IQR 8–10). The high wear-time compliance, low voluntary withdrawal rate and high acceptability scores indicate overall acceptability and feasibility of measuring PA in high-risk elderly patients in the preoperative period using these accelerometers.

Discussion

These data demonstrate that wrist-worn accelerometers can successfully be used to measure PA in high-risk elderly patients in the preoperative period, and that this process was acceptable to participants. The fact that there was no statistical correlation between participant-reported PASE and accelerometer-measured PA highlights the need for more objective measures of PA24 and suggests a role for such devices in perioperative research and perhaps clinical care.

We demonstrated a substantial variability in baseline PA in the frail elderly preoperative population. Our study also gives an estimate of the typical mean daily PA levels in this specific group of patients which has not previously been described. Such data should inform the planning of potential studies involving PA measurements in this setting. We found low PA levels in this population: we do not have access to a ‘control’ group as such a group would be difficult to define. However, by way of comparison, the UK Biobank study reported mean daily ENMO values in over three thousand 75–79 year olds (the most comparable group to ours) women of 23.9 mg (SD=6.5) and in men this was 22.9 mg (SD=6.8).13 Our study population had lower baseline mean daily ENMO of 18.9 mg (SD=10.5) in women, and 13.71 mg (SD=6.1) in men, which may reflect their underlying medical conditions, frailty and increased age (mean age of our study population was 79.9 years SD 5.6).

ENMO may not be as intuitive as postprocessed PA intensity metrics such as step count or time spent in various intensities of PA. However, such metrics may not generalise outside the population in which they were developed.25 Furthermore, we wanted to avoid using any potentially proprietary algorithms. Using unprocessed ENMO avoids both of these problems as it is the fundamental physical quantity measured by all accelerometers and should therefore be agnostic to patient group. Further work is be needed to develop metabolically meaningful PA intensity cut points in this patient group, but we suggest from our work that ENMO summary data are a useful surrogate even without this.

In the non-orthopaedic subgroup, we found a significant increase in PA following the PRIME clinic intervention, even though this was not optimised. Mixed-effect modelling did not show any decrease in PA over time in either the preintervention or postintervention group suggesting that PA levels were sustained at least for the duration of the measurement period. Because we had no control on which day of the week participants would be recruited from clinic, we also looked at whether activity might be different on weekend days, but this did not seem to be the case in this population. The PA levels in some patients postintervention resembled more closely the baseline levels reported in the Biobank study. The fact that PA levels increased to this extent following the unoptimised intervention is a remarkable and somewhat unexpected finding as health behavioural change is notoriously difficult to achieve.10 Our findings provide some evidence to suggest that the preoperative setting may indeed represent a unique period during which behavioural interventions are more likely to result in improvements in PA, perhaps due to the well-defined endpoint (surgical procedure) and the motivation that PA may impact perioperative outcome. It seems reasonable to suggest that a well-designed complex intervention could result in greater changes in PA.

The lack of significant improvement in PA in those participants awaiting orthopaedic surgery may indicate a restriction of PA in this population, in which mobility is likely to be limited due to underlying orthopaedic problems (all orthopaedic participants were awaiting major lower limb joint replacements). The potential to increase preoperative PA in the orthopaedic population may be limited; waiting lists for joint replacement surgery in the UK are long, and such patients may have already been in the hospital system prior to the PRIME clinic visit (intervention). This potentially restricted PA, and prior engagement with hospital services may mean that these patients may have already received PA advice from their surgical and primary care teams prior to referral to the PRIME clinic and may have already reached their prehabilitation limit. Nevertheless, although PA in this subgroup group did not change following the existing unoptimised intervention, there is perhaps still scope for a better intervention, and wearable accelerometers may assist in determining what this may be. Our finding provides support for the idea that a complex intervention would need to be tailored to this population.

We asked participants to wear the accelerometers around their wrist. Traditionally, the hip has been the most widely used site for placement of the accelerometer as this was believed to best represent total body movement.26 However, wear-time compliance has been a problem with hip-worn devices which limits the validity of the data analysis.27 Cui et al 28 fixed an accelerometer to participants’ chests using an adhesive plaster; however, one quarter of participants did not wear the device for 72 hours which may limit the validity of data. We opted for a wrist-worn device to circumvent this issue, and asked participants to wear the device continuously (day and night) for a 7-day period to simplify proceedings. We also felt that this placement would capture PA associated with ADL, likely to form a significant proportion of PA among a high-risk elderly population. While previous studies have used the non-dominant wrist,13 for this pilot study we allowed a pragmatic approach to allow participants to select their preferred wrist in order to maximise compliance and total wear time. Furthermore, previous work has shown no difference in PA measurements when measured simultaneously on the dominant and non-dominant wrist.29 We accept that in a frail elderly population, many of whom use walking aids, a wrist-worn device must be used with caution and further work is warranted to evaluate the transferability of data from different sites.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size. Within this small sample, we were non-selective regarding recruitment of participants from various surgical specialties. As such, we were unable to further analyse data from subgroups other than orthopaedics versus non-orthopaedics. This is an area of potential future research incorporating larger patient numbers in various subspecialties. One further limitation was that we did not attempt to relate ENMO measurements to specific ADL. This will be an important subsequent study but was outside the scope of this work as it might have reduced tolerability.

While we have demonstrated that patients’ behaviour can change in the preoperative period, we do not know how this translates clinically, and indeed what degree (if any) of change in PA might lead to a change in the outcomes that are important to patients. However, it is reasonable to propose that such a relationship might exist, and further work is needed to investigate whether increasing PA levels in the preoperative period has any impact on perioperative outcome, and if so, whether the response is dose or timing dependent. Furthermore, if an association between preoperative PA and perioperative outcome is discovered, it is important to determine the minimum duration of increased PA levels required to influence patient outcome, and whether this would be feasible in the preoperative period. If optimum PA level targets can be determined, it would then be important to find out whether it is actually possible to meet PA ‘targets’ in the high-risk elderly population by use of preoperative interventions. Further research into the optimum prehabilitation programme for frail elderly patients in various patient cohorts is also required. While we have demonstrated that the increase in PA after the intervention was sustained throughout the 7-day measurement period, we do not know whether the increase in PA is sustained beyond this period. Further work is required to elucidate this.

Conclusion

Using wrist-worn accelerometers to characterise daily typical activity levels and assess the impact of an existing clinical intervention was feasible and acceptable in this patient population. An increase in PA levels was measured following an unoptimised routine clinical intervention, and this increase in PA was sustained for at least a week suggesting that the preoperative period may be a teachable moment in which health behavioural change interventions may be successful. Patient-reported PA did not correlate with our objective measurements. Accelerometers may therefore be a useful tool to design and validate interventions for improving PA in this setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the help of the nursing staff of the Preoperative Assessment Clinic at Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Christopher Hall and Mark Vivian for their assistance with participant recruitment, and Amanda Saunders and Sarah Lester for assistance with retrieval and distribution of accelerometers in the PRIME clinic visit.

Footnotes

Twitter: @abitgrim

Contributors: LG, AE and SJG contributed to the conception and design of the study. LG and JGO contributed to data collection. LG and AE wrote the protocol, were responsible for data analysis and prepared the manuscript. All authors contributed to the review and revision of the manuscript and provided final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Approval by a Research Ethics Committee was obtained prior to participant recruitment (Research ethics number: 18/SC/0287).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: The authors will consider reasonable collaborative requests to share data.

References

- 1. Pearse RM, Harrison DA, James P, et al. Identification and characterisation of the high-risk surgical population in the United Kingdom. Crit Care 2006;10:R81 10.1186/cc4928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg 2010;210:901–8. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Louwers L, Schnickel G, Rubinfeld I. Use of a simplified frailty index to predict Clavien 4 complications and mortality after hepatectomy: analysis of the National surgical quality improvement project database. Am J Surg 2016;211:1071–6. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harvey JA, Chastin SFM, Skelton DA. Prevalence of sedentary behavior in older adults: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013;10:6645–61. 10.3390/ijerph10126645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Taylor D. Physical activity is medicine for older adults. Postgrad Med J 2014;90:26–32. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. British Heart Foundation Physical inactivity across the four nations. Phys Inact Sedentary Behav Rep 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rogers NT, Marshall A, Roberts CH, et al. Physical activity and trajectories of frailty among older adults: evidence from the English longitudinal study of ageing. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170878 10.1371/journal.pone.0170878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nilsson H, Angerås U, Bock D, et al. Is preoperative physical activity related to post-surgery recovery? a cohort study of patients with breast cancer. BMJ Open 2016;6:e007997 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Picorelli AMA, Pereira LSM, Pereira DS, et al. Adherence to exercise programs for older people is influenced by program characteristics and personal factors: a systematic review. J Physiother 2014;60:151–6. 10.1016/j.jphys.2014.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Middleton KR, Anton SD, Perri MG. Long-Term adherence to health behavior change. Am J Lifestyle Med 2013;7:395–404. 10.1177/1559827613488867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bond DS, Jakicic JM, Unick JL, et al. Pre- to postoperative physical activity changes in bariatric surgery patients: self report vs. objective measures. Obesity 2010;18:2395–7. 10.1038/oby.2010.88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vanhees L, Lefevre J, Philippaerts R, et al. How to assess physical activity? how to assess physical fitness? Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2005;12:102–14. 10.1097/00149831-200504000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Doherty A, Jackson D, Hammerla N, et al. Large scale population assessment of physical activity using wrist worn accelerometers: the UK Biobank study. PLoS One 2017;12:1–14. 10.1371/journal.pone.0169649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. Can Med Assoc J 2005;173:489–95. 10.1503/cmaj.050051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Axivity AX3_Data_Sheet (1), 2015. Available: https://axivity.com/files/resources/AX3_Data_Sheet.pdf [Accessed 12 Jun 2019].

- 16. Clarke CL, Taylor J, Crighton LJ, et al. Validation of the AX3 triaxial accelerometer in older functionally impaired people. Aging Clin Exp Res 2017;29:451–7. 10.1007/s40520-016-0604-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van Hees VT, Fang Z, Zhao JH. GGIR: RAW Accelerometer data analysis. R Packag version 18-1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Hees VT, Fang Z, Langford J, et al. Autocalibration of accelerometer data for free-living physical activity assessment using local gravity and temperature: an evaluation on four continents. J Appl Physiol 2014;117:738–44. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00421.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, et al. The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:153–62. 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Physiotools PhysioTools key features. Available: https://www.physiotools.com/physiotools-key-features [Accessed 24 Feb 2019].

- 22. Team RC R: a language and environment for statistical computing, 2017. Available: https://www.R-project.org/ [Accessed 12 Jul 2019].

- 23. Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, et al. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4 . J Stat Softw 2015;67:1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wareham NJ, Rennie KL. The assessment of physical activity in individuals and populations: why try to be more precise about how physical activity is assessed? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1998;22 Suppl 2:S30–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schrack JA, Cooper R, Koster A, et al. Assessing daily physical activity in older adults: unraveling the complexity of monitors, measures, and methods. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016;71:1039–48. 10.1093/gerona/glw026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cleland I, Kikhia B, Nugent C, et al. Optimal placement of accelerometers for the detection of everyday activities. Sensors 2013;13:9183–200. 10.3390/s130709183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Troiano RP, McClain JJ, Brychta RJ, et al. Evolution of accelerometer methods for physical activity research. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1019–23. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cui HW, Kirby GS, Surmacz K, et al. The association of pre-operative home accelerometry with cardiopulmonary exercise variables. Anaesthesia 2018;73:738–45. 10.1111/anae.14181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dieu O, Mikulovic J, Fardy PS, et al. Physical activity using wrist-worn accelerometers: comparison of dominant and non-dominant wrist. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2017;37:525–9. 10.1111/cpf.12337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.