Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study was to evaluate the association of genetically determined leptin with lipids.

Design

We conducted a Mendelian randomisation study to assess a potential causal relationship between serum leptin and lipid levels. We also evaluated whether alcohol drinking modified the associations of genetically determined leptin with blood lipids.

Setting and participants

3860 participants of the Framingham Heart Study third generation cohort.

Results

Both genetic risk scores (GRSs), the GRS generated using leptin loci independent of body mass index (BMI) and GRS generated using leptin loci dependent of BMI, were positively associated with log-transformed leptin (log-leptin). The BMI-independent leptin GRS was associated with log-transformed triglycerides (log-TG, β=−0.66, p=0.01), but not low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C, p=0.99), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C, p=0.44) or total cholesterol (TC, p=0.49). Instrumental variable estimation showed that per unit increase in genetically determined log-leptin was associated with 0.55 (95% CI: 0.05 to 1.00) units decrease in log-TG. Besides significant association with log-TG (β=−0.59, p=0.009), the BMI-dependent GRS was nominally associated with HDL-C (β=−10.67, p=0.09) and TC (β=−28.05, p=0.08). When stratified by drinking status, the BMI-dependent GRS was associated with reduced levels of LDL-C (p=0.03), log-TG (p=0.004) and TC (p=0.003) among non-current drinkers only. Significant interactions between the BMI-dependent GRS and alcohol drinking were identified for LDL-C (p=0.03), log-TG (p=0.03) and TC (p=0.02).

Conclusion

These findings together indicated that genetically determined leptin was negatively associated with lipid levels and the association may be modified by alcohol consumption.

Keywords: epidemiology, leptin, lipids, alcohol consumption, genetic risk score

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Population-based Mendelian randomisation studies may offer an opportunity to provide better evidence for the association of leptin with lipid metabolism in the adult population compared with observational epidemiology studies.

The stringent quality control methods were used in measuring genotypes, phenotype and covariates in the current study to reduce measurement error and increase the statistical power.

Pleiotropy effects of single-nucleotide polymorphisms included in the leptin genetic risk score (GRS) may confound the leptin GRS and lipids associations.

Our analyses were restricted to individuals of European ancestry.

Introduction

Leptin is a key hormone that regulates appetite and food intake, body weight and energy balance.1 2 Leptin is secreted primarily from the stomach, placenta and adipose tissue.3 Biological studies have demonstrated that elevated leptin levels may play an important role in the pathogenesis of lipid accumulation.4–9 As an active endocrine organ, the adipose tissue secretes leptin and plays a key role in immunometabolism.10 Leptin can regulate both innate and adaptive immune responses11 12 and subsequently regulate lipid profiles. Animal study demonstrated that hyperleptinaemia decreases the expression of sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 (SREBP-1c), a master regulator of lipid metabolism, in liver and adenovirus-induced hyperleptinaemia decreases triglyceride (TG) synthesis through SREBP-1c downregulation.13 Meanwhile, SREBP-1c is involved in innate immune response in macrophages.14 Therefore, it is rational to see immune connects with leptin in respect of lipid regulation. Case reports and case series have documented that leptin therapy can improve lipid profiles among patients with lipoatrophy or congenital leptin deficiency.15–19 On contrary, in a cross-sectional survey of 12–16 years old high-school students, plasma leptin was positively associated with total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and TG.20 Since observational epidemiologic studies cannot rule out all confounding effects, it is unclear whether such an association is causal. On the other hand, there are studies that demonstrate a neutral effect of leptin on blood lipid levels.21 A small clinical trial that involved 17 patients with HIV-associated lipodystrophy suggested that leptin treatment did not improve fasting lipid kinetics.21 Population-based Mendelian randomisation studies may offer an opportunity to provide better evidence for the effect of leptin on lipid metabolism in the adult population. Recently, a large-scale genome-wide association study (GWAS) meta-analysis identified five genomic loci associated with circulating leptin,22 which provides an opportunity to conduct a Mendelian randomisation study to delineate the association between serum leptin and lipid levels. In addition, alcohol consumption has been shown to influence leptin secretion in both human and animal models.23–36 In rodent models, leptin has been demonstrated to be increased26–28 or decreased29 30 after alcohol intake. Similarly, leptin levels in human was decreased,32 increased31 33 or even unchanged34–36 after drinking. It is unclear whether alcohol consumption modifies the association of genetically determined leptin with lipid levels.37 38

Therefore, the objectives of the current study were to evaluate the relationship between genetically determined leptin and lipid levels and to explore whether the leptin–lipids associations could be modified by alcohol consumption among participants of the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) third generation cohort.

Materials and methods

Data sources and study participants

The FHS was designed to identify common factors or characteristics that contribute to cardiovascular disease (CVD) by tracking the development of CVD over a long period of time. Participants of the FHS were free from overt symptoms of CVD or stroke at baseline. Later on, the FHS was extended to including offspring and third generation of the original participants. A detailed description of the FHS third generation cohort has been outlined in previous publications.39 Genotype and phenotype data of the FHS are catalogued on the database of genotype and phenotype (dbGaP) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). We have received approval to use the FHS data by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Georgia and the NCBI. Serum leptin levels, genotypes, lipid levels and important covariates were available for 3860 (94.7%) participants of the third generation cohort at baseline in 2002–2005 (table 1). Those participants were included in the current analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants by GRS1* for log-leptin in FHS third generation cohort

| Covariates | Overall | Quartiles of the leptin GRS | ||||

| (n=3860) | Q1 (n=964) | Q2 (n=961) | Q3 (n=977) | Q4 (n=958) | P value | |

| GRS, mean (SD) | 0.07 (0.03) | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.11 (0.01) | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 40.2 (8.9) | 40.5 (8.7) | 39.9 (8.8) | 40.3 (9.1) | 39.9 (8.8) | 0.23 |

| Male, N (%) | 1808 (46.8) | 453 (47.0) | 437 (45.5) | 460 (47.1) | 458 (47.8) | 0.89 |

| Education levels, N (%) | ||||||

| No more than high school | 591 (15.4) | 141 (14.7) | 146 (15.3) | 157 (16.1) | 147 (15.4) | 0.22 |

| Some college | 1213 (31.5) | 306 (31.8) | 287 (30.0) | 313 (32.1) | 307 (32.3) | |

| Bachelor’s degree and above | 2041 (53.1) | 514 (53.5) | 524 (54.8) | 505 (51.8) | 498 (52.3) | |

| Current smoker, N (%) | 603 (15.6) | 144 (15.0) | 152 (15.8) | 165 (16.9) | 142 (14.8) | 0.53 |

| Current drinker, N (%) | 3419 (89.1) | 858 (89.4) | 853 (89.1) | 863 (88.9) | 845 (89.0) | 0.32 |

| Physical activities index score, mean (SD) | 37.5 (7.9) | 37.8 (8.0) | 37.3 (8.1) | 37.4 (7.7) | 37.4 (7.8) | 0.51 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 26.9 (5.5) | 26.9 (5.5) | 26.7 (5.5) | 26.9 (5.5) | 27.1 (5.5) | 0.94 |

| Waist girth, inches, mean (SD) | 36.6 (6.0) | 36.7 (6.0) | 36.3 (5.8) | 36.7 (5.9) | 36.8 (6.1) | 0.70 |

| Treated for lipids, N (%) | 265 (6.9) | 80 (8.3) | 56 (5.8) | 66 (6.8) | 63 (6.6) | 0.26 |

| Treated for diabetes, N (%) | 72 (1.9) | 22 (2.3) | 23 (2.4) | 19 (1.9) | 8 (0.8) | 0.03 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 111.7 (31.4) | 112.1 (30.5) | 111.5 (31.1) | 111.9 (32.4) | 111.3 (31.8) | 0.94 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 54.3 (16.1) | 54.1 (15.4) | 54.4 (15.9) | 54.5 (16.2) | 54.4 (16.7) | 0.62 |

| TG, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 92.0 (65.0–138.0) | 92.0 (65.0–142.0) | 96.0 (66.0–140.0) | 92.0 (65.0–137.0) | 90.0 (63.0–134.0) | 0.03† |

| TC, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 188.8 (35.5) | 189.1 (34.1) | 188.9 (37.1) | 189.5 (35.7) | 187.9 (35.2) | 0.64 |

| Leptin, ng/dL, median (IQR) | 12.5 (3.5–15.1) | 6.7 (3.4–14.5) | 7.2 (3.4–14.8) | 7.7 (3.7–14.9) | 7.7 (3.6–16.8) | 0.02† |

| Log-leptin, mean (SD) | 2.00 (1.1) | 1.95 (1.0) | 1.98 (1.1) | 2.00 (1.0) | 2.06 (1.1) | 0.02 |

| Age, sex, BMI and waist girth adjusted log-leptin, mean (SD) | 2.0 (1.1) | 2.0 (1.0) | 2.0 (1.1) | 2.0 (1.0) | 2.1 (1.1) | 0.00005 |

*GRS1 for leptin was generated by summing leptin increasing alleles of three SNPs adjusted for BMI, weighted by their corresponding effect sizes reported by Kilpeläinen et al.

†Log-leptin and TG were used to calculate the p values.

BMI, body mass index; GRS, genetic risk score;HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Log-leptin, logarithmically transformed leptin; SNPs, single-nucleotide polymorphisms; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

Genotyping and GRS

Genetic loci for circulating leptin levels have been reported in a large GWAS meta-analysis by Kilpeläinen and colleagues.22 This study included 32 161 individuals of European ancestry and identified three single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), GCKR rs780093, LEP rs10487505 and SLC32A1 rs6071166, that were robustly associated with body mass index (BMI) adjusted leptin at a genome-wide significance level (p<5×10−8). In addition, GCKR rs780093, CCNL1 rs900400 and FTO rs8043757 were associated with circulating leptin without adjustment for BMI.22 We assumed the additive genetic model for each SNP and constructed two genetic risk scores (GRSs) for leptin by combining leptin-increasing alleles for SNPs weighted by their corresponding effect sizes on logarithmically transformed leptin (log-leptin) as reported in the original GWAS meta-analysis.22 The first score, GRS1, was generated using the three SNPs associated with BMI-adjusted leptin, and the second score, GRS2, using the three SNPs associated with leptin unadjusted for BMI.

Genome-wide SNPs were genotyped using Affymetrix and Illumina platforms in the FHS. The 1000 Genome genotype data for the FHS was already imputed and catalogued on the dbGaP. According to the document of the FHS,40 before imputation, quality control removed SNPs with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium p<1×10−6, missing rate>3%, minor allele frequency (MAF) <1%, missing physical position or cannot mapped to build 37 positions, Mendelian errors >1000 or duplicate. MACH software was used for genotype phasing, followed by imputation using MiniMac software.41 42 Imputation results were summarised as dosage scores, which represent the expected numbers of copies of the coded allele for each SNP, ranging from 0 to 2. After imputation, SNPs with r 2<0.30, MAF <1% or Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium p<1×10−6 were removed. We retrieved genotypes of the SNPs for GRSs from the imputed data for all study participants (online supplementary tables S1 and S2).

bmjopen-2018-026860supp001.pdf (895.6KB, pdf)

Leptin and lipids measurement

In the FHS, blood samples were collected after overnight fasting and analysed following standard protocols.43 Serum leptin levels were determined by ELISA method at R&D Systems using the Quantikine Human Leptin Immunoassay.43 Leptin was logarithmically transformed for analyses in the current study so that the data distribution can meet the assumptions of linear regression models.

Fasting blood lipids, including TC, HDL-C and TG, were measured using automated enzymatic assays.43 For participants taking lipid-lowering medications, TC was adjusted as TC/0.8.44 After adjustment, LDL-C was calculated using the Friedewald formula.45 The adjusted TC and LDL-C were used for analyses in the current study. TG were logarithmically transformed (log-TG) in the current study so that the data distribution can meet the assumptions of linear regression models.

Covariates

Demographic and health behavioural variables, including age, gender, education, smoking and drinking, were based on self-report. Education levels were categorised into ‘no more than high school’, ‘some college’ and ‘bachelor’s degree or above’. Smoking was categorised into ‘current smoker’ or ‘non-current smoker’ and drinking status into ‘current drinker’ and ‘non-current drinker’. Physical activity was measured with the physical activity index composite score, which was calculated by summing the number of hours spent in each activity intensity level weighted by their corresponding weight factor derived from the estimated oxygen consumption requirement for each intensity level.46 BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres. Waist circumference was measured to next lower 1/4 inch by regional anthropometry.

Statistical analysis

Weighted GRSs for leptin were calculated for each participant as the sum of the products of the participant’s dosage scores for each SNP and the SNP’s estimated effect size. Since obesity is highly associated with both leptin and blood lipids, our main focus was on GRS1, the score generated using loci associated with leptin independent of BMI. The GRS1 for participants was then categorised into quartiles. Means and SD for continuous and frequencies and percentages for categorical characteristics at baseline were calculated for each quartile of the GRS1. P values for linear trends in those variables across quartiles of the GRS1 were estimated.

Three multivariate linear regression models were used to assess associations between log-leptin and lipids, leptin GRS and log-leptin and the leptin GRS and lipids, respectively. All models were adjusted for age, sex, BMI and waist circumference. To test robustness of the leptin GRS and lipids associations, we additionally controlled for education, smoking, drinking and physical activity index score in the fully adjusted models. To explore whether associations between the leptin GRS and lipids levels were modified by alcohol consumption, we performed stratified analyses by drinking status. In each stratum of the drinking status, we tested associations between leptin GRS and lipids by adjusting for age, sex, BMI and waist circumference in the base model and additionally adjusting for education, smoking and physical activity in the full model. Interactions between the leptin GRS and alcohol consumption were tested among the overall participants by adding drinking and the interaction term, GRS×drinking, to the models. All the above analyses were done for GRS1 and GRS2 separately. We quantified the strength of the causal association of leptin with lipids using the instrumental variable estimator.47 The estimator was calculated as the ratio of the coefficient for leptin GRS and lipids association to the coefficient for the leptin GRS and log-leptin association from the base models.

To rule out the effect of lipid-lowering medications, sensitivity analyses were performed among those not taking lipid medication. To rule out the effect of both diabetes and lipid-lowering medications, sensitivity analyses were performed among those not taking lipid-lowering or glucose-lowering medications. All analyses were performed using SAS software (V.9.4; SAS Institute). Two-sided p values were provided, and p<0.05 was considered significant.

Participant and public involvement

Neither patients or public were directly involved in the development, design or recruitment of the study. Results will not be disseminated directly to study participants.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants are presented in table 1. Participants were on average 40.2 years old at baseline. There were slightly more females (53.2%), and only 15.4% had less than a high-school education. The majority (89.1%) of the participants were current drinkers, and 15.6% were current smokers. Participants were on average over weighted, with a mean BMI of 26.9 kg/m2 and mean waist girth of 36.6 inches. About 6.9% of the participants were treated for dyslipidemia, and 1.9% were treated for diabetes. The BMI-independent leptin GRS1 was not associated with age (p=0.23), sex (p=0.89), education (p=0.22), smoking (p=0.53), drinking (p=0.32), BMI (p=0.94), waist circumference (p=0.70), lipid-lowering medication usage (p=0.26) or the physical activity index score (p=0.51), but with diabetes-lowering medication usage (p=0.03). As expected, the GRS1 was positively associated with age, sex, BMI and waist circumference-adjusted log-leptin (p=4.56×10−5).

BMI-independent leptin GRS1 and blood lipids

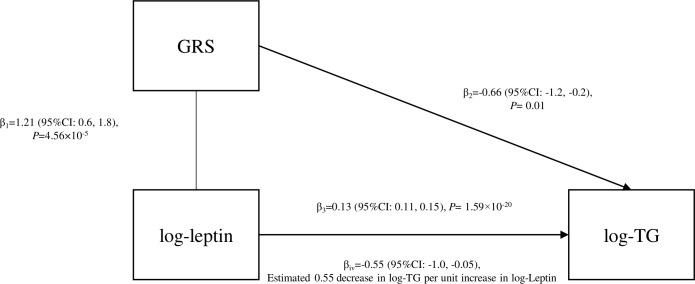

After controlling for age, sex, BMI and waist circumference, log-leptin was positively associated with TC (β=8.56, p=6.35×10−18), LDL-C (β=6.46, p=1.85×10−13) and log-TG (β=0.13, p=1.59×10−20), but was not associated with HDL-C (β=−0.62, p=0.11, figure 1 and online supplementary figure S1). Per unit increase in the leptin GRS1 was associated with a 1.21 unit increase in the age, sex, BMI and waist circumference adjusted log-leptin (p=4.56×10−5). The leptin GRS1 was inversely associated with age, sex, BMI and waist circumference-adjusted log-TG (β=−0.66, p=0.01, figure 1). When further adjusting for education, smoking, drinking and physical activity, the GRS1 and log-TG association was still significant (β=−0.69, p=0.008, table 2). Instrumental variable estimation indicated that log-TG levels decreased by 0.55 (95% CI: 0.05, 1.00, p=0.02) per unit increase of genetically determined log-leptin level (figure 1). The leptin GRS1 was inversely associated with TC (β=−12.50, p=0.49) and LDL-C (β=−0.11, p=0.99) and positively associated with HDL-C (β=5.42, p=0.44), however, the correlations were not significant. The GRS1 and blood lipids associations were not modified by drinking status (table 2).

Figure 1.

The relationship between log-leptin, GRS1 for leptin and log-TG in FHS the third generation cohort. FHS, Framingham Heart Study; GRS, genetic risk score; log-TG, logarithmically transformed triglycerides.

Table 2.

Association of BMI-independent leptin GRS1* with baseline lipids among overall, drinking and non-drinking participants of the FHS third generation cohort, respectively

| Age, sex, BMI, waist circumference adjusted model | Pinteraction † | Fully adjusted model‡ | Pinteraction § | |||

| Beta (SE) | P value | Beta (SE) | P value | |||

| HDL-C | ||||||

| Overall | 5.42 (7.10) | 0.44 | 0.74 | 7.79 (7.11) | 0.27 | 0.71 |

| Not current drinkers | 20.42 (18.29) | 0.26 | 22.22 (18.76) | 0.24 | ||

| Current drinkers | 6.00 (7.61) | 0.43 | 7.02 (7.64) | 0.36 | ||

| LDL-C | ||||||

| Overall | −0.11 (16.09) | 0.99 | 0.79 | −1.09 (16.24) | 0.95 | 0.93 |

| Not current drinkers | 3.37 (48.63) | 0.94 | −4.18 (50.10) | 0.93 | ||

| Current drinkers | −0.14 (17.10) | 0.99 | −1.80 (17.18) | 0.92 | ||

| Log-TG | ||||||

| Overall | −0.66 (0.26) | 0.01 | 0.31 | −0.69 (0.26) | 0.008 | 0.32 |

| Not current drinkers | −1.41 (0.80) | 0.08 | −1.32 (0.82) | 0.11 | ||

| Current drinkers | −0.58 (0.27) | 0.04 | −0.61 (0.27) | 0.03 | ||

| Total cholesterol | ||||||

| Overall | −12.50 (18.21) | 0.49 | 0.96 | −12.58 (18.31) | 0.49 | 0.86 |

| Not current drinkers | −15.20 (54.11) | 0.78 | −19.13 (55.66) | 0.73 | ||

| Current drinkers | −10.20 (19.37) | 0.60 | −11.43 (19.42) | 0.56 | ||

*GRS1 for leptin was generated by summing leptin increasing alleles of three SNPs adjusted for BMI, weighted by their corresponding effect sizes reported by Kilpelainen et al.

†Assessed by adding an interaction term, drinking×GRS along with the drinking variable to the age, sex, BMI and waist circumference adjusted model among the overall participants.

‡Adjusted for age, sex, education, smoking, drinking, BMI, waist circumference and physical activity among the overall sample.

§Assessed by adding an interaction term, drinking×GRS to the fully adjusted model among the overall participants.

BMI, body mass index; FHS, Framingham Heart Study; GRS, genetic risk score; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; log-TG, logarithmically transformed triglycerides; SE, standard error; SNPs, single-nucleotide polymorphisms.

BMI-dependent leptin GRS2 and blood lipids

As expected, the BMI-dependent leptin GRS2 was not associated with any covariate except for the BMI (p=0.02) and waist circumference (p=0.03). In the analyses controlling for age, sex, BMI and waist circumference, the GRS2 was significantly associated with lower levels of log-TG (p=0.009) and nominally associated with lower levels of HDL-C (p=0.09) and TC (p=0.08, online supplementary figure S2). When stratified by drinking status, the leptin GRS2 was negatively associated with LDL-C (β=−92.51, p=0.03), log-TG (β=−2.07, p=0.004) and TC (β=−144.68, p=0.003) only among non-current drinkers (table 3). When further adjusting for education, smoking, drinking and physical actvity, those associations persisted (table 3). Furthermore, significant interactions between leptin GRS2 and alcohol drinking were identified for LDL-C (p=0.03), log-TG (p=0.03) and TC (p=0.02, table 3).

Table 3.

Association of BMI-dependent leptin GRS2* with baseline lipids among overall, drinking and non-drinking participants of the FHS third generation cohort, respectively

| Age, sex, BMI, waistadjusted model | Pinteraction † | Fully adjusted model‡ | Pinteraction § | |||

| Beta (SE) | P value | Beta (SE) | P value | |||

| HDL-C | ||||||

| Overall | −10.67 (6.20) | 0.09 | 0.56 | −10.98 (6.22) | 0.08 | 0.52 |

| Not current drinkers | −0.69 (16.31) | 0.97 | 0.82 (16.55) | 0.96 | ||

| Current drinkers | −12.15 (6.64) | 0.07 | −11.94 (6.68) | 0.07 | ||

| LDL-C | ||||||

| Overall | −2.11 (14.05) | 0.88 | 0.03 | −2.81 (14.21) | 0.84 | 0.02 |

| Not current drinkers | −92.51 (43.02) | 0.03 | −101.15 (43.78) | 0.02 | ||

| Current drinkers | 9.21 (14.91) | 0.54 | 7.89 (15.02) | 0.60 | ||

| Log-TG | ||||||

| Overall | −0.59 (0.23) | 0.009 | 0.03 | −0.59 (0.23) | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Not current drinkers | −2.07 (0.71) | 0.004 | −2.03 (0.72) | 0.005 | ||

| Current drinkers | −0.40 (0.24) | 0.09 | −0.42 (0.24) | 0.08 | ||

| Total cholesterol | ||||||

| Overall | −28.05 (15.91) | 0.08 | 0.02 | −28.74 (16.02) | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| Not current drinkers | −144.68 (47.61) | 0.003 | −151.32 (48.37) | 0.002 | ||

| Current drinkers | −13.19 (16.90) | 0.44 | −14.67 (16.98) | 0.39 | ||

*GRS2 for leptin was generated by summing leptin increasing alleles of three SNPs unadjusted for BMI, weighted by their corresponding effect sizes reported by Kilpelainen et al.

†Assessed by adding an interaction term, drinking×GRS along with the drinking variable to the age, sex, BMI and waist-adjusted model among the overall participants.

‡Adjusted for age, sex, education, smoking, drinking, BMI, waist and physical activity among the overall sample.

§Assessed by adding an interaction term, drinking×GRS to the fully adjusted model among the overall participants.

BMI, body mass index; FHS, Framingham Heart Study; GRS, genetic risk score; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; log-TG, logarithmically transformed triglycerides; SE, standard error.

When restricting to participants not taking lipid-lowering medication and those not taking lipid- or glucose-lowering medications, respectively, the associations of GRS1 and GRS2 with blood lipids were similar to those as shown above (online supplementary tables S3–S6).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first Mendelian randomisation analysis on leptin and blood lipids. We provide robust evidence to support a potentially causal relation between leptin and reduced levels of TG among a majority of overweight and obese population of European ancestry. Furthermore, we demonstrated that alcohol consumption modified the association of BMI-dependent GRS2 with lipids in that genetically determined leptin levels were inversely associated with LDL-C, log-TG and TC, but only among individuals who were not current drinkers.

Both the BMI dependent-GRS and independent-GRS were associated with lower level of log-TG in the current study. Inconsistent associations between leptin and blood lipids have been observed in previous studies. In a small study of 80 postmenopausal women, serum leptin was positively associated with HDL-C, TG and TC, and inversely associated with LDL-C.48 Another study conducted with 294 healthy school children reported that leptin was only associated with increased TG.49 However, a study of 476 residents from Cameroon reported a positive correlation between leptin, LDL-C and TC, and a positive association between leptin and TC, but no association between leptin and HDL-C or TG.50 In a more recent study of 134 physically active postmenopausal women, no significant correlation was detected for leptin and blood lipids.51 The divergent results of previous studies make it impossible to infer a relationship between leptin and blood lipids. Possible reasons for the divergent findings include varying sample sizes, failure to account for residual and unmeasured confounding and the genetic background of the study population. Through Mendelian randomisation analyses, we demonstrated that genetically determined leptin was inversely associated with log-TG. It is well known that alleles, such as risk alleles for leptin, are randomly assigned at meiosis and therefore, are independent of non-genetic confounders. The association between leptin GRS and log-TG in the current study was less prone to confounding. This also highlights the importance of using Mendelian randomisation to delineate causal relationships. Our finding is further supported by previous physiologic studies, among which, leptin was demonstrated to inhibit lipogenesis, stimulate lipolysis and reduce TG uptake.52 However, the association of HDL-C and TC was only nominally significant with BMI-dependent GRS2 in the current study. It could be due to lack of statistical power or existing interaction of leptin and drinking. Therefore, we cannot rule out causal relationships between leptin and those lipid measures. Future large-scale Mendelian randomisation studies are warranted to evaluate associations of leptin GRS with HDL-C, LDL-C, and TC.

The BMI-independent GRS1 was only associated with log-TG, while the BMI-dependent GRS2 was also in nominal associations with HDL-C and TC. In addition, alcohol drinking modified the GRS2–lipids associations but not the GRS1–lipids associations. This indicated that the role of leptin in blood lipids regulation may be through multiple mechanisms. The BMI-dependent GRS2 was inversely associated with LDL-C, log-TG and TC only among non-current drinkers, but not among current drinkers. Although future studies are warranted to confirm these interactions, previous physiological studies may provide a reasonable explanation. Singh and colleagues demonstrated that the increased expression of caveolin-1 impairs leptin signalling and attenuates leptin-dependent effect to prevent lipid accumulation in human white preadipocytes.53 Meanwhile, caveolin-1 can be increased by alcohol drinking.54

Our study represents the first Mendelian randomisation analyses for leptin and blood lipids in a population of European ancestry. A major strength of this study is the stringent quality control methods used in measuring genotypes, phenotype and covariates in the FHS third generation cohort. Those methods can reduce measurement error and increase the statistical power needed to identify associations between leptin GRS and lipids. We also identify some limitations. First, pleiotropy effects of SNPs included in the leptin GRS may confound the leptin GRS and lipids associations. It is possible that our results may represent a shared genetic basis between leptin and lipids rather than a causal relationship. Second, we may not have sufficient power to detect associations between genetically determined leptin levels and LDL-C, HDL-C and TC. Larger Mendelian randomisation studies are warranted to evaluate associations between leptin and LDL-C, HDL-C and TC. Third, we did not control for total energy intake in our analyses because food frequency questionnaire survey was not conducted in the third generation cohort at baseline when leptin was measured. However, leptin combines with receptors in the hypothalamus to reduce appetite and increase energy expenditure. Therefore, total energy intake is in the pathway from leptin to lipids metabolism and may not meet the criteria of being a confounder. Forth, the type of alcohol consumed for current drinker was not measured and cannot be considered in the current analyses. It is possible that the alcohol consumed in the studied population is mainly wine and/or beers, which contains high level of resveratrol and phytochemical. The two chemicals may benefit lipid metabolism.55 56 However, the two chemicals do not share similar genetic profile with leptin, and consequently, they should not be correlated with leptin and cannot affect the associations between leptin GRS and blood lipids. Fifth, genetically determined ratio of leptin to leptin receptor may be a better measure to study the role of leptin in lipid metabolism. However, we could not find a genome-wide study on the ratio of leptin to leptin receptor; therefore, a GRS on the ratio cannot be calculated. Future genome-wide studies on the ratio of leptin to leptin receptor are warranted. Finally, our analyses were restricted to individuals of European ancestry. Our findings may not be generalisable to populations of other ancestries.

In summary, the present study provided robust evidence for a potential causal effect of leptin on reduced TG. In addition, genetically determined leptin may regulate blood lipids through different mechanisms, and the association between leptin and lipid metabolism may be modified by alcohol consumption.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge editorial assistance of Ms Jessica Ho.

Footnotes

Contributors: CL, JFC, J-SW, SL and ZZ helped in the study conceptualisation. LS and YS performed the formal analysis. Supervision was done by CL, JFC, J-SW, SL and ZZ. The original draft was written by LS. CL, JFC, LS, LL and ZZ helped in review and editing.

Funding: Dr. Zhiyong Zou was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81773454) and China Scholarship Council (201806015008).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository.

References

- 1. Campfield LA, Smith FJ, Guisez Y, et al. Recombinant mouse ob protein: evidence for a peripheral signal linking adiposity and central neural networks. Science 1995;269:546–9. 10.1126/science.7624778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Halaas JL, Gajiwala KS, Maffei M, et al. Weight-reducing effects of the plasma protein encoded by the obese gene. Science 1995;269:543–6. 10.1126/science.7624777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, et al. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature 1994;372:425–32. 10.1038/372425a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sáinz N, Barrenetxe J, Moreno-Aliaga MJ, et al. Leptin resistance and diet-induced obesity: central and peripheral actions of leptin. Metabolism 2015;64:35–46. 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang MY, Lee Y, Unger RH. Novel form of lipolysis induced by leptin. J Biol Chem 1999;274:17541–4. 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harris RBS. Direct and indirect effects of leptin on adipocyte metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014;1842:414–23. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Enser M, Ashwell M. Fatty acid composition of triglycerides from adipose tissue transplanted between obese and lean mice. Lipids 1983;18:776–80. 10.1007/BF02534635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Selenscig D, Rossi A, Chicco A, et al. Increased leptin storage with altered leptin secretion from adipocytes of rats with sucrose-induced dyslipidemia and insulin resistance: effect of dietary fish oil. Metabolism 2010;59:787–95. 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kosztáczky B, Fóris G, Paragh G, et al. Leptin stimulates endogenous cholesterol synthesis in human monocytes: new role of an old player in atherosclerotic plaque formation. leptin-induced increase in cholesterol synthesis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2007;39:1637–45. 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Francisco V, Pino J, Campos-Cabaleiro V, et al. Obesity, fat mass and immune system: role for leptin. Front Physiol 2018;9:640 10.3389/fphys.2018.00640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. La Cava A. Leptin in inflammation and autoimmunity. Cytokine 2017;98:51–8. 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maurya R, Bhattacharya P, Dey R, et al. Leptin functions in infectious diseases. Front Immunol 2018;9:2741 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kakuma T, Lee Y, Higa M, et al. Leptin, troglitazone, and the expression of sterol regulatory element binding proteins in liver and pancreatic islets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000;97:8536–41. 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Im S-S, Yousef L, Blaschitz C, et al. Linking lipid metabolism to the innate immune response in macrophages through sterol regulatory element binding protein-1a. Cell Metab 2011;13:540–9. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Paz-Filho G, Mastronardi CA, Licinio J. Leptin treatment: facts and expectations. Metabolism 2015;64:146–56. 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Park JY, Javor ED, Cochran EK, et al. Long-term efficacy of leptin replacement in patients with Dunnigan-type familial partial lipodystrophy. Metabolism 2007;56:508–16. 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Javor ED, Cochran EK, Musso C, et al. Long-term efficacy of leptin replacement in patients with generalized lipodystrophy. Diabetes 2005;54:1994–2002. 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ebihara K, Kusakabe T, Hirata M, et al. Efficacy and safety of leptin-replacement therapy and possible mechanisms of leptin actions in patients with generalized lipodystrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:532–41. 10.1210/jc.2006-1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kamran F, Rother KI, Cochran E, et al. Consequences of stopping and restarting leptin in an adolescent with lipodystrophy. Horm Res Paediatr 2012;78:320–5. 10.1159/000341398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu DM, Shen MH, Chu NF. Relationship between plasma leptin levels and lipid profiles among school children in Taiwan--the Taipei Children Heart Study. Eur J Epidemiol 2001;17:911–6. 10.1023/a:1016280427032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sekhar RV, Jahoor F, Iyer D, et al. Leptin replacement therapy does not improve the abnormal lipid kinetics of hypoleptinemic patients with HIV-associated lipodystrophy syndrome. Metabolism 2012;61:1395–403. 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kilpeläinen TO, Carli JFM, Skowronski AA, et al. Genome-Wide meta-analysis uncovers novel loci influencing circulating leptin levels. Nat Commun 2016;7:10494 10.1038/ncomms10494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Röjdmark S, Calissendorff J, Brismar K. Alcohol ingestion decreases both diurnal and nocturnal secretion of leptin in healthy individuals. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001;55:639–47. 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01401.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roth MJ, Baer DJ, Albert PS, et al. Relationship between serum leptin levels and alcohol consumption in a controlled feeding and alcohol ingestion study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003;95:1722–5. 10.1093/jnci/djg090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Otaka M, Konishi N, Odashima M, et al. Effect of alcohol consumption on leptin level in serum, adipose tissue, and gastric mucosa. Dig Dis Sci 2007;52:3066–9. 10.1007/s10620-006-9635-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pravdova E, Macho L, Fickova M. Alcohol intake modifies leptin, adiponectin and resistin serum levels and their mRNA expressions in adipose tissue of rats. Endocr Regul 2009;43:117–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Slomiany BL, Slomiany A. Role of epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation in the activation of cytosolic phospholipase A(2) in leptin protection of salivary gland acinar cells against ethanol cytotoxicity. J Physiol Pharmacol 2009;60:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yu H-cai, Li S-ying, Cao M-feng, et al. Effects of chronic ethanol consumption on levels of adipokines in visceral adipose tissues and sera of rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2010;31:461–9. 10.1038/aps.2010.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maddalozzo GF, Turner RT, Edwards CHT, et al. Alcohol alters whole body composition, inhibits bone formation, and increases bone marrow adiposity in rats. Osteoporos Int 2009;20:1529–38. 10.1007/s00198-009-0836-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tan X, Sun X, Li Q, et al. Leptin deficiency contributes to the pathogenesis of alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Am J Pathol 2012;181:1279–86. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Henriksen JH, Holst JJ, Møller S, et al. Increased circulating leptin in alcoholic cirrhosis: relation to release and disposal. Hepatology 1999;29:1818–24. 10.1002/hep.510290601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Santolaria F, Pérez-Cejas A, Alemán M-R, et al. Low serum leptin levels and malnutrition in chronic alcohol misusers hospitalized by somatic complications. Alcohol Alcohol 2003;38:60–6. 10.1093/alcalc/agg015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nicolás JM, Fernández-Solà J, Fatjó F, et al. Increased circulating leptin levels in chronic alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001;25:83–8. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02130.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Beulens JWJ, de Zoete EC, Kok FJ, et al. Effect of moderate alcohol consumption on adipokines and insulin sensitivity in lean and overweight men: a diet intervention study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2008;62:1098–105. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Voican CS, Njiké-Nakseu M, Boujedidi H, et al. Alcohol withdrawal alleviates adipose tissue inflammation in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Liver Int 2015;35:967–78. 10.1111/liv.12575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Greco AV, Mingrone G, Favuzzi A, et al. Serum leptin levels in post-hepatitis liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2000;33:38–42. 10.1016/S0168-8278(00)80157-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wannamethee SG, Tchernova J, Whincup P, et al. Plasma leptin: associations with metabolic, inflammatory and haemostatic risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis 2007;191:418–26. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Balasubramaniyan V, Nalini N. Intraperitoneal leptin regulates lipid metabolism in ethanol supplemented Mus musculas heart. Life Sci 2006;78:831–7. 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.05.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Splansky GL, Corey D, Yang Q, et al. The third generation cohort of the National heart, lung, and blood Institute's Framingham heart study: design, recruitment, and initial examination. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165:1328–35. 10.1093/aje/kwm021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sebro R, Peloso GM, Dupuis J, et al. Structured mating: patterns and implications. PLoS Genet 2017;13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006655. [published Online First: 2017/04/06]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015;526:68–74. 10.1038/nature15393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Das S, Forer L, Schönherr S, et al. Next-Generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat Genet 2016;48:1284–7. 10.1038/ng.3656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Andersson C, Lyass A, Larson MG, et al. Low-Density-Lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations and risk of incident diabetes: epidemiological and genetic insights from the Framingham heart study. Diabetologia 2015;58:2774–80. 10.1007/s00125-015-3762-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rao DC, Sung YJ, Winkler TW, et al. Multiancestry study of Gene-Lifestyle interactions for cardiovascular traits in 610 475 individuals from 124 cohorts: design and rationale. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2017;10 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kannel WB, Sorlie P. Some health benefits of physical activity. The Framingham study. Arch Intern Med 1979;139:857–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Palmer TM, Sterne JAC, Harbord RM, et al. Instrumental variable estimation of causal risk ratios and causal odds ratios in Mendelian randomization analyses. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:1392–403. 10.1093/aje/kwr026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jaleel F, Jaleel A, Rahman MA, et al. Comparison of adiponectin, leptin and blood lipid levels in normal and obese postmenopausal women. J Pak Med Assoc 2006;56:391–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kavazarakis E, Moustaki M, Gourgiotis D, et al. Relation of serum leptin levels to lipid profile in healthy children. Metabolism 2001;50:1091–4. 10.1053/meta.2001.25606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ayina CNA, Noubiap JJN, Etoundi Ngoa LS, et al. Association of serum leptin and adiponectin with anthropomorphic indices of obesity, blood lipids and insulin resistance in a sub-Saharan African population. Lipids Health Dis 2016;15:96 10.1186/s12944-016-0264-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jürimäe T, Jürimäe J, Leppik A, et al. Relationships between adiponectin, leptin, and blood lipids in physically active postmenopausal females. Am J Hum Biol 2010;22:609–12. 10.1002/ajhb.21052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hynes GR, Jones PJ. Leptin and its role in lipid metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol 2001;12:321–7. 10.1097/00041433-200106000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Singh P, Peterson TE, Sert-Kuniyoshi FH, et al. Leptin signaling in adipose tissue: role in lipid accumulation and weight gain. Circ Res 2012;111:599–603. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.273656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gao L, Zhou Y, Zhong W, et al. Caveolin-1 is essential for protecting against binge drinking-induced liver damage through inhibiting reactive nitrogen species. Hepatology 2014;60:687–99. 10.1002/hep.27162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Haghighatdoost F, Hariri M. Effect of resveratrol on lipid profile: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis on randomized clinical trials. Pharmacol Res 2018;129:141–50. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.12.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Leng E, Xiao Y, Mo Z, et al. Synergistic effect of phytochemicals on cholesterol metabolism and lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells. BMC Complement Altern Med 2018;18:122 10.1186/s12906-018-2189-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026860supp001.pdf (895.6KB, pdf)