Abstract

Aim

The aim of this study was to investigate if working in a cold environment and feeling cold at work are associated with chronic pain (ie, lasting ≥3 months).

Methods

We used data from the sixth survey (2007–2008) of the Tromsø Study. Analyses included 6533 men and women aged 30–67 years who were not retired, not receiving full-time disability benefits and had no missing values. Associations between working in a cold environment, feeling cold at work and self-reported chronic pain were examined with logistic regression adjusted for age, sex, education, body mass index, insomnia, physical activity at work, leisure time physical activity and smoking.

Results

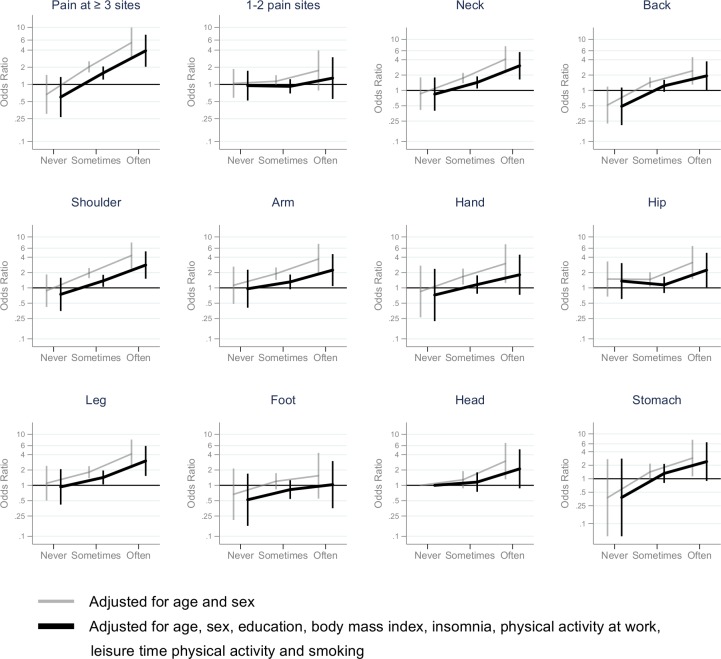

779 participants reported working in a cold environment ≥25% of the time. This exposure was positively associated with pain at ≥3 sites (OR 1.57; 95% CI 1.23 to 2.01) and with neck, shoulder and leg pain, but not with pain at 1–2 sites. Feeling cold sometimes or often at work was associated with pain at ≥3 sites (OR 1.58; 95% CI 1.22 to 2.07 and OR 3.90; 95% CI 2.04 to 7.45, respectively). Feeling cold often at work was significantly and positively associated with pain at all sites except the hand, foot, stomach and head.

Conclusion

Working in a cold environment was significantly associated with chronic pain. The observed association was strongest for pain at musculoskeletal sites and for those who often felt cold at work.

Keywords: epidemiology, occupational & industrial medicine, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study has a high response rate (65.7%) which increases the likelihood that it is a representative sample of the working population.

The observed associations in the present study are consistent for pain at multiple sites and at specific sites.

The healthy worker effect may cause an underestimation of the associations.

The results are to some extent vulnerable to residual confounding by other occupational risk factors.

Introduction

By evolution, humans are not physiologically fit to live in cold environments. To survive in such environments, we must use different strategies, such as insulating clothing, houses and heating, which protect us from low temperatures. However, these protective measures may not be sufficient, as there is an excess of deaths recorded during the winter season. This excess is only partly explained by seasonal diseases and thus indicates that even moderately cold temperatures induce a strain on the body and negatively affect health.1

Cold exposure can cause pain. Indeed, immersing one’s hand in cold water is commonly used as a test of pain tolerance.2 Exposure to a cold environment, at work or during leisure time, can cause one to experience acute pain. In Finland, the reported prevalence of musculoskeletal pain believed by respondents to be caused by cold exposure is as high as 30% for men and 27% for women.3 4 Cold exposure is also known to reduce both physical and cognitive performance.5 6 Cold temperatures may also have subacute effects. Working in a cold environment has been found to be associated with an increased prevalence of back, neck and shoulder pain.7–10 In addition, it has been suggested that working in a cold environment is related to respiratory, cardiovascular and dermatological complaints and diseases.11

Factors that affect workers’ thermal balance are contact with water or cold surfaces, humidity, air velocity, radiation, type of clothing and the heat produced by executing the work.12 A cold working environment is defined as an environment with an ambient temperature below 10°C.13 However, the ambient air temperature might not be a good measure of a worker’s heat loss. In a study of seafood-processing workers, no relationship was found between workers’ reports of feeling cold and measured air velocity, air temperature at the feet or air temperature 1.1 m above the floor.14 This indicates that actual cold exposure is difficult to measure. Some studies have circumvented this problem by using self-reported cold experience as a measure of cold exposure.15 16 Among workers in the food processing industry, self-reported experiences of cooling of the neck, shoulder, wrist and lower back were associated with a self-reported disadvantage in daily routines due to pain at those sites.15 In a study of seafood industry workers, feeling cold often at work was associated with musculoskeletal pain.16 Feeling cold often at work has also been associated with an increased prevalence of symptoms from skin and airways.14

These previous studies mostly used 12 months prevalence, that is, musculoskeletal pain over the last 12 months, as the outcome. This includes acute periods of pain within the past 12 months, but contributes no information about the duration of pain. Chronic pain, defined as pain lasting 3 months or longer, may be a better measure of the impact on quality of life and future work ability.17 18 However, there is a lack of studies on the association between cold exposure and chronic musculoskeletal pain or pain in other tissues. Therefore, the main aim of this study was to investigate if working in a cold environment and feeling cold at work are associated with chronic pain. We hypothesise that exposure to a cold work environment increases the prevalence of chronic pain.

Methods

Participants

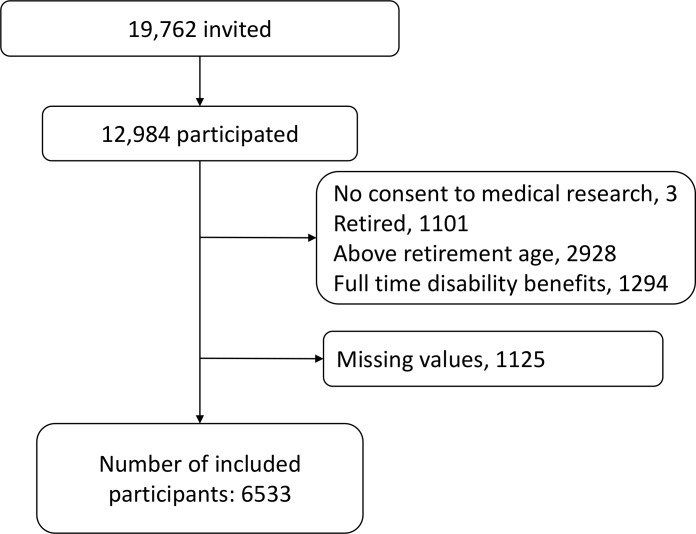

The Tromsø Study is a prospective cohort study performed in the municipality of Tromsø in Northern Norway. The study currently consists of seven surveys, with the first conducted in 1974 and the seventh in 2015–2016. Tromsø has a coastal climate; the outdoor temperature is below 10°C for a major part of the year and seldom falls below −10°C.19 This study includes participants from the sixth survey of the Tromsø Study (Tromsø 6), which was carried out in 2007–2008 and encompassed physical examinations and extensive health questionnaires.20 Of the 19 762 individuals invited to Tromsø 6, 12 984 (65.7%) participated. The age of the participants ranged from 30 to 87 years. We excluded participants who were retired, were above retirement age (ie, 67 years), on full-time disability benefits and those with missing values. Thus, the final study population comprised 6533 men and women (figure 1). The Regional Committee of Research Ethics approved Tromsø 6 and this particular analysis.

Figure 1.

Flowchart presenting number of subjects invited to Tromsø 6, those who participated in Tromsø 6 and those excluded and included in the present analysis.

Pain

Participants were asked ‘Do you have persistent or recurrent pain lasting 3 months or more’ (Yes/No), and if so, at which anatomical site the pain was situated. The alternatives were jaw, neck, back, shoulder, arm (including elbow), hand, hip, leg (including thigh, knee and calves), foot (including ankle), head (including face), chest, stomach, genitals, skin and other. Sites where participants reported pain were then counted, and participants were categorised as having: no pain, pain at 1–2 sites and pain at ≥3 sites.

Cold exposure

The Tromsø 6 questionnaire included the question ‘Do you work outdoors at least 25% of the time or in cold buildings (eg, storage/industry buildings)?’. Only those who answered ‘Yes’ were given an extra set of questions about working in a cold environment in the second questionnaire. Among those questions were ‘Do you feel cold at work?’ (yes, often/yes, sometimes/no, never).

Confounders

Possible confounders obtained from the questionnaires were age, sex, education, insomnia, physical activity at work, leisure time physical activity and smoking. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from weight and height measured at the examination. BMI was categorised into underweight/normal weight (<25 kg/m2), overweight (≥25 kg/m2 and <30 kg/m2) and obese (≥30 kg/m2) in the descriptive statistics, but it was included as a continuous variable in the regression analysis. Insomnia was assessed by the question ‘In the past 12 months, how often have you suffered from sleeplessness?’ (never or just a few times a year/1–3 times a month/approximately once a week/more than once a week). Physical activity at work was measured with the question ‘If you have paid or unpaid work, which statement describes your work best?’ (mostly sedentary/requires a lot of walking/requires a lot of walking and lifting/heavy manual labour). Leisure time physical activity had four categories: sedentary, low, moderate and hard. Sedentary was described as ‘reading, watching TV or other sedentary activity’, low as ‘walking, cycling or other forms of exercise at least 4 hours per week’, moderate as ‘recreational sports, heavy gardening for at least 4 hours per week’ and hard as ‘hard training or sports competition, regularly several times per week’. Smoking was categorised into current, former and never smoker.

Statistics

Pearson χ² test was used to test differences in prevalence if all cells had n>5; Fisher’s exact test was used if n≤5. T-test was used for age. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the association between working in a cold environment ≥25% of the time and self-reported pain. All statistical analyses were performed in Stata MP 15.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in this particular substudy.

Results

Participants

Among the 6533 participants included in the study, 779 reported to work in a cold environment ≥25% of the time. These individuals were younger, were mostly men, had lower levels of education compared with the rest of the working population and had a higher BMI. They were also more likely to have physically demanding work, have lower levels of leisure time physical activity and to be current or former smokers (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Working in a cold environment ≥25% of the time | |||||

| No, n=5754 | Yes, n=779 | t/χ2 | |||

| n | % | n | % | P value | |

| Age (years)* | 49.9 | 8.8 | 48.8 | 8.7 | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 3178 | 55.2 | 143 | 18.4 | |

| Male | 2576 | 44.8 | 636 | 81.6 | <0.001 |

| Education | |||||

| Primary/secondary | 727 | 12.6 | 262 | 33.6 | |

| Technical school | 1261 | 21.9 | 308 | 39.5 | |

| High school | 513 | 8.9 | 75 | 9.6 | |

| College/university<4 years | 1350 | 23.5 | 94 | 12.1 | |

| College/university≥4 years | 1903 | 33.1 | 40 | 5.1 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index | |||||

| Under and normal weight (<25 kg/m2) | 2233 | 38.8 | 205 | 26.3 | |

| Overweight (≥25 and <30 kg/m2) | 2494 | 43.3 | 406 | 52.1 | |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 1027 | 17.8 | 168 | 21.6 | <0.001 |

| Insomnia | |||||

| Never or just a few times a year | 3927 | 68.2 | 576 | 73.9 | |

| 1–3 times a month | 1042 | 18.1 | 118 | 15.1 | |

| Approximately once a week | 365 | 6.3 | 42 | 5.4 | |

| More than once a week | 420 | 7.3 | 43 | 5.5 | 0.014 |

| Physical activity at work | |||||

| Mostly sedentary work | 3497 | 60.8 | 87 | 11.2 | |

| Work that requires a lot of walking | 1454 | 25.3 | 176 | 22.6 | |

| Work that requires a lot of walking and lifting (n, %) | 760 | 13.2 | 379 | 48.7 | |

| Heavy manual labour | 43 | 0.7 | 137 | 17.6 | <0.001 |

| Leisure time physical activity | |||||

| Sedentary | 1081 | 18.8 | 186 | 23.9 | |

| Low | 3350 | 58.2 | 410 | 52.6 | |

| Moderate | 1176 | 20.4 | 174 | 22.3 | |

| Hard | 147 | 2.6 | 9 | 1.2 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | |||||

| Current | 1111 | 19.3 | 211 | 27.1 | |

| Former | 2227 | 38.7 | 319 | 40.9 | |

| Never | 2416 | 42 | 249 | 32 | <0.001 |

*Numbers are mean and SD for age, otherwise n and %.

Out of the 779 workers who reported working in a cold environment ≥25% of the time, 92 never felt cold at work, 635 felt cold sometimes and 52 felt cold often. The prevalence of chronic pain at different anatomical sites was higher in those who often or sometimes felt cold at work compared with those who never felt cold (table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of chronic pain in participants working in a cold environment <25% of the time and in those working in a cold environment ≥25% of the time by frequency of feeling cold

| Anatomical sites | Working in a cold environment <25% of the time n=5754 |

Frequency of feeling cold at work among those working in a cold environment ≥25% of the time n=779 |

||||||

| Never, n=92 | Sometimes, n=635 | Often, n=52 | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 1–2 sites | 783 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 91 | 14 | 8 | 15 |

| ≥3 sites | 904 | 16 | 7 | 8 | 128 | 20 | 21 | 40 |

| Neck | 765 | 13 | 8 | 9 | 106 | 17 | 18 | 35 |

| Back | 811 | 14 | 6 | 7 | 106 | 17 | 14 | 27 |

| Shoulder | 753 | 13 | 8 | 9 | 113 | 18 | 18 | 35 |

| Arm | 465 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 69 | 11 | 11 | 21 |

| Hand | 341 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 39 | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| Hip | 514 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 49 | 8 | 9 | 17 |

| Leg | 557 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 76 | 12 | 13 | 25 |

| Foot | 385 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 36 | 6 | 4 | 8 |

| Head | 318 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 5 | 7 | 14 |

| Stomach | 210 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 27 | 4 | 5 | 10 |

Multiple pain sites

Working in a cold environment ≥25% of the time was significantly associated with pain at ≥3 sites after adjustment (OR 1.57; 95% CI 1.23 to 2.01) (table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis with pain at 1–2 or ≥3 sites and specific pain sites as outcomes

| Anatomical sites | Working in a cold environment <25% of the time n=5754 |

Working in a cold environment ≥25% of the time n=779 |

||||

| Reference | Adjusted for age and sex | Fully adjusted model* | ||||

| n | n | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| 1–2 sites† | 783 | 113 | 1.15 | 0.92 to 1.44 | 0.95 | 0.73 to 1.24 |

| ≥3 sites‡ | 904 | 156 | 2.02 | 1.64 to 2.48 | 1.57 | 1.23 to 2.01 |

| Neck | 765 | 132 | 1.78 | 1.44 to 2.20 | 1.46 | 1.13 to 1.89 |

| Back | 811 | 126 | 1.38 | 1.12 to 1.71 | 1.18 | 0.91 to 1.52 |

| Shoulder | 753 | 139 | 1.96 | 1.58 to 2.42 | 1.39 | 1.08 to 1.78 |

| Arm | 465 | 86 | 1.93 | 1.49 to 2.50 | 1.34 | 0.98 to 1.83 |

| Hand | 341 | 48 | 1.66 | 1.19 to 2.32 | 1.16 | 0.79 to 1.71 |

| Hip | 514 | 65 | 1.59 | 1.19 to 2.12 | 1.26 | 0.90 to 1.75 |

| Leg | 557 | 96 | 1.87 | 1.47 to 2.40 | 1.47 | 1.10 to 1.96 |

| Foot | 385 | 43 | 1.16 | 0.83 to 1.63 | 0.80 | 0.54 to 1.19 |

| Head | 318 | 39 | 1.28 | 0.89 to 39 | 1.13 | 0.75 to 1.70 |

| Stomach | 210 | 33 | 1.42 | 0.96 to 33 | 1.30 | 0.82 to 2.04 |

Statistically significant results are highlighted in bold (p < .05)

*Adjusted for age, sex, education, body mass index, insomnia, physical activity at work, leisure time physical activity and smoking.

†Model does not include those with pain at ≥3 sites.

‡Model does not include those with pain at 1–2 sites.

n the fully-adjusted model, those who worked in a cold environment ≥25% of the time did not have higher odds for pain at 1–2 sites compared with those who worked in a cold environment <25% of the time. When those who worked in a cold environment ≥25% were divided by frequency of feeling cold, feeling cold sometimes and often was associated with pain at ≥3 sites (OR 1.58; 95% CI 1.22 to 2.07 and OR 3.90; 95% CI 2.04 to 7.45, respectively) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

ORs with 95% CIs for chronic pain. Working in a cold environment ≥25% of the time and feeling cold never, sometimes or often compared with those working in a cold environment <25% of the time.

Pain at specific sites

In the analysis with pain at specific sites as outcomes, the low number of participants who worked in a cold environment ≥25% with pain in the jaw (n=4), chest (n=10), skin (n=5), genitals (n=8) and other location (n=3) prevented separate analyses for these outcomes. When using pain at the remaining 10 sites as separate outcomes, working in cold environments ≥25% of the time was significantly associated with pain at all sites except the foot, head and stomach in the model adjusted for age and sex (table 3). Although those working in cold environments ≥25% of the time had higher odds for pain at all sites except the foot in the fully-adjusted model, only the associations for pain at the neck, shoulder and leg were statistically significant (table 3).

When those working in cold environments ≥25% of the time were divided by frequency of feeling cold, those who felt cold sometimes or often at work had significantly higher odds for pain at most musculoskeletal sites compared with those working in a cold environment <25% of the time. In the model adjusted for age and sex, feeling cold often was significantly associated with head and stomach pain (figure 2).

After adjusting for possible confounders, only pain from musculoskeletal pain sites remained significant; workers who felt cold often had higher odds for neck, shoulder, arm, leg, back and hip pain compared with the group that worked in a cold environment <25% of the time (figure 2). The strongest association was for neck pain (OR 3.05; 95% CI 1.64 to 5.66). Among those working in cold environments ≥25% of the time, the group that reported feeling cold sometimes at work had higher odds for neck, shoulder and leg pain, with ORs between those who never felt cold and those who felt cold often at work (figure 2). In the group working in cold environments ≥25% of the time, never feeling cold at work was not significantly associated with chronic pain at any specific site in either of the models.

Discussion

Key results

In this study, working in a cold environment ≥25% of the time was associated with chronic pain (ie, pain lasting ≥3 months) at the neck, shoulder and leg, as well as pain at ≥3 sites, even after adjusting for age, sex, education, BMI, insomnia, physical activity at work and leisure time physical activity. Those who felt cold often at work had significantly higher odds for pain at ≥3 sites and for pain at all specified sites except the hand, foot, head and stomach. Feeling cold sometimes at work was significantly associated with neck, shoulder and leg pain. We found no significant differences in chronic pain between those who never felt cold when working in a cold environment ≥25% of the time and those who worked in cold environment <25% of the time.

There are many different aetiologies of pain and we do not have sufficient information to appropriately identify the origin of the pain.21 Additionally, we have no information on whether the reported pain was present at all times or only when exposed to cold environment. Nevertheless, the ORs for chronic pain at musculoskeletal locations in the present study were lower than estimates for musculoskeletal pain during the last 12 months from studies of slaughterhouse and seafood industry workers.15 16 Interestingly, in the fully-adjusted model, we found no association between working in a cold environment ≥25% of the time and hand and foot pain. These are the body parts that are most susceptible to cooling. If cooling of local tissue is the mechanism for a higher prevalence of chronic pain, one could assume that body parts most exposed to cold would be at a higher risk for pain. The results for hand and foot in the present study do not support such an assumption. However, this observation is in contrast to other studies that found associations between a cold environment or an experience of cooling of the wrist and pain in the wrist, hand and forearm.7 15 22 The difference between earlier findings and the present study might be due to a different aetiology and pathology for chronic musculoskeletal pain and 12 month pain prevalence. Different study populations and cold exposures could also contribute to the contradictory results.

Feeling cold is a subjective experience and contains little or no information about the actual environment, such as ambient temperature, humidity and air velocity. However, ambient temperature could also be a poor measure of cold exposure. A study of seafood industry workers could not establish a simple relationship between thermal environmental factors and the prevalence of workers feeling cold. The same study also found that working in relatively high temperatures (>12°C) led to low finger temperatures and a major drop in foot temperature.14 Thermal comfort and sensation seem to be closely connected to both average skin temperature and rectal temperature.23 Although subjective, feeling cold might be a better indication of the environment’s effect on the body than ambient air temperature.

The general health status of a person might also influence to what degree they feel cold. Individuals with already existing diseases are more prone to report cold-related musculoskeletal pain,24 and male slaughterhouse workers with chronic pain had more complaints about indoor climate, including complaints about temperatures that were too low and draughts, when compared with those without pain.25 Chronic pain could also influence the perception of feeling cold. The design of the present study is not adequate to address the direction of the observed association.

Few plausible causal mechanisms between cold exposure and musculoskeletal pain, chronic or not, have been suggested. Studies have found that cooling induces acute physiological alterations in the musculoskeletal and neural system. There seems to be a dose-response relationship between the temperature in the muscle and muscle power, and the contraction velocity decreases with decreasing temperature. Further, there is an increased activation of the antagonist muscles indicating a reduced motor control.26–28 Another study reports an enhanced fatigue in the muscles when performing repetitive work in a cold environment.29 These alterations point in the direction that cold exposure increases the strain on the musculoskeletal apparatus. Repeated exposure to a cold environment can also have a long-term effect in the form of habituation or acclimatisation. Habituation is described as a reduction in shivering, vasoconstriction stress response and cold sensation. Additionally, different acclimatisation processes like lowering core temperature, increasing the metabolic rate and increasing vasoconstriction or subcutaneous fat have been reported.30 However, a relationship between these altered acute and long-term physiological responses, and subsequent chronic pain has not been satisfactorily established. A cross-sectional study of slaughterhouse workers found that a lower pressure pain threshold was associated with more complaints about the indoor climate.25 A possible explanation for the observed association between chronic pain and frequency of feeling cold in the present study could be that persons who felt cold have a lower pain threshold than those who did not. Future research should explore whether this is genetic or if thermal stimuli could contribute to a sensitisation process.

Strengths and limitations

In our study, participants who worked in a cold environment ≥25 of the time had generally low education and executed a lot of heavy physical work, both of which have been identified as risk factors for musculoskeletal pain31–33; adjusting for these confounders attenuated the associations in the present study. Workers exposed to cold are also exposed to several other occupational risk factors that can be associated with poor health, and physical activity at work is not a satisfactory measure of these risk factors.34 Consequently, the results are to some extent vulnerable to residual confounding.

There are a number of clinical conditions that could be a cause of pain or increase the risk of chronic pain.21 As these conditions could be unevenly distributed, they could confound the observed association. Our results could also be influenced by the healthy-worker effect.35 Feeling cold is uncomfortable, and individuals negatively affected by a cold environment might change their occupation or workplace to avoid getting cold. The remaining employees exposed to cold may therefore be the ones that are the least negatively affected by the cold. Additionally, chronic pain can contribute to selection bias by having a different impact in different occupations. There is a social gradient in disability benefits, and physical work has been found to increase the risk for disability pension, even after adjustment for health status.36 Thus, the effect estimates may be underestimated.

The high response rate (65.7 %) of Tromsø 6 is a major strength and increases the likelihood that the findings are representative of the general population. Nevertheless, non-participants in Tromsø 6 tend to have lower education than participants;20 therefore, we cannot rule out that the prevalence of cold-exposed workers was higher among non-participants. Additionally, some of the occupations in which workers are typically exposed to cold environments have a high number of migrant workers, a group not invited to participate in The Tromsø Study. As an example, in 2008 in Norway, approximately 12% of workers in the construction industry were migrant workers.37 These aspects may have led to selection bias and thus an underestimation of the proportion of workers exposed to a cold environment. How this selection bias affects the association between feeling cold and musculoskeletal pain or cold-related health complaints is not known.

A clear limitation of the study is the low number of participants who reported feeling cold often or never, resulting in large CIs. Also, there were few female participants working in a cold environment ≥25% of the time (n=123), which prevented any useful analysis stratified by sex. There are sex differences in types of work, prevalence of cold discomfort or cooling15 and in the prevalence of musculoskeletal pain.33 The association between working in cold environment and musculoskeletal pain is likely different by sex.

The observed associations in the present study are consistent for pain at multiple sites and at specific sites. Although not all the effect estimates were significant, the direction of the associations was consistent, with increased reporting of pain with increasing experience of cold at work, at all sites except the hip. This consistency and the high effect estimates indicate that the observed associations are robust and that additional adjustment for occupational risk factors would not explain all associations.

Even though Tromsø is situated at 69°N, the climate is relatively mild due to the Gulf Stream. There are also several factors other than ambient air temperature that can affect a worker’s thermal balance, for example, amount of protective clothing. At work, individual differences in heat loss, protection and adaptations, such as behavioural responses, adjusting clothing or increasing physical activity, are very difficult to measure and would vary throughout a workday. The heat loss of one worker in a cold environment may be the same as that of another in a moderately cold environment if not properly protected. Thus, we believe the results of the present study are not specific to our study population, but relevant to others working in cold environments, whether they are indoor or outdoor.

Conclusion

Working in a cold environment ≥25% of the time was associated with chronic pain at ≥3 sites and with neck, shoulder and leg pain. Those who worked in a cold environment and felt cold often at work had higher odds for neck, shoulder, arm, back, hip and leg pain compared with those who worked in a cold environment <25% of the time. Working in a cold environment ≥25% of the time and never feeling cold was not associated with pain at any site. Organising work and workplaces in a way that ensures thermal balance for workers might reduce the risk of chronic pain.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Collaborators: Lisbeth Aasmoe contributed to the data acquisition of questions regarding work in the cold from the 6th survey of the Tromsø Study.

Contributors: EHF, ACH and MS designed the study. EHF conducted the data analysis and wrote the manuscript with the assistance of ACH and MS. TB assisted in the analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation and revised the manuscript. CN and AS contributed to the data acquisition of questions regarding pain from the 6th survey of the Tromsø Study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This particular study has been funded by UiT—The Arctic University of Norway. The 6th survey of The Tromsø Study is a collaboration between the Northern Norway Regional Health Authority, UiT—The Arctic University of Norway, Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services, Troms County and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. The publication charges for this article have been funded by a grant from the publication fund of UiT The Arctic University of Norway.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data are available by applying to The Tromsø Study http://tromsoundersokelsen.uit.no/tromso/

References

- 1. Gasparrini A, Guo Y, Hashizume M, et al. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observational study. Lancet 2015;386:369–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62114-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Modir JG, Wallace MS. Human experimental pain models 2: the cold pressor model. Methods Mol Biol 2010;617:165–8. 10.1007/978-1-60327-323-7_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pienimäki T, Karppinen J, Rintamäki H, et al. Prevalence of cold-related musculoskeletal pain according to self-reported threshold temperature among the Finnish adult population. Eur J Pain 2014;18:288–98. 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00368.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Raatikka V-P, Rytkönen M, Näyhä S, et al. Prevalence of cold-related complaints, symptoms and injuries in the general population: the FINRISK 2002 cold substudy. Int J Biometeorol 2007;51:441–8. 10.1007/s00484-006-0076-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mäkinen TM, Palinkas LA, Reeves DL, et al. Effect of repeated exposures to cold on cognitive performance in humans. Physiol Behav 2006;87:166–76. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pilcher JJ, Nadler E, Busch C. Effects of hot and cold temperature exposure on performance: a meta-analytic review. Ergonomics 2002;45:682–98. 10.1080/00140130210158419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pienimäki T. Cold exposure and musculoskeletal disorders and diseases. A review. Int J Circumpolar Health 2002;61:173–82. 10.3402/ijch.v61i2.17450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burström L, Järvholm B, Nilsson T, et al. Back and neck pain due to working in a cold environment: a cross-sectional study of male construction workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2013;86:809–13. 10.1007/s00420-012-0818-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dovrat E, Katz-Leurer M. Cold exposure and low back pain in store workers in Israel. Am J Ind Med 2007;50:626–31. 10.1002/ajim.20488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Skandfer M, Talykova L, Brenn T, et al. Low back pain among mineworkers in relation to driving, cold environment and ergonomics. Ergonomics 2014;57:1541–8. 10.1080/00140139.2014.904005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mäkinen TM, Hassi J. Health problems in cold work. Ind Health 2009;47:207–20. 10.2486/indhealth.47.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Parsons K. Human thermal environments: the effects of hot, moderate, and cold environments on human health, comfort, and performance. CRC Press, Inc, 2014: 635. [Google Scholar]

- 13. International Organization of Standardisation ISO 15743:2008 Ergonomics of the thermal environment - Cold workplaces- Risk assessment and managment. Geneva, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bang BE, Aasmoe L, Aardal L, et al. Feeling cold at work increases the risk of symptoms from muscles, skin, and airways in seafood industry workers. Am J Ind Med 2005;47:65–71. 10.1002/ajim.20109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sormunen E, Remes J, Hassi J, et al. Factors associated with self-estimated work ability and musculoskeletal symptoms among male and female workers in cooled food-processing facilities. Ind Health 2009;47:271–82. 10.2486/indhealth.47.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aasmoe L, Bang B, Egeness C, et al. Musculoskeletal symptoms among seafood production workers in North Norway. Occup Med (Lond) 2008;58:64–70. 10.1093/occmed/kqm136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Skevington SM. Investigating the relationship between pain and discomfort and quality of life, using the WHOQOL. Pain 1998;76:395–406. 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00072-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mallen CD, Peat G, Thomas E, et al. Prognostic factors for musculoskeletal pain in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:655–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weather statistics for Tromsø observation site Tromsø (Troms) yr.no: the Norwegian meteorological Institute, 2018. Available: https://www.yr.no/place/Norway/Troms/Troms%C3%B8/Troms%C3%B8_observation_site/statistics.html [Accessed 13 Nov 2018].

- 20. Eggen AE, Mathiesen EB, Wilsgaard T, et al. The sixth survey of the Tromso study (Tromso 6) in 2007-08: collaborative research in the interface between clinical medicine and epidemiology: study objectives, design, data collection procedures, and attendance in a multipurpose population-based health survey. Scand J Public Health 2013;41:65–80. 10.1177/1403494812469851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Treede R-D, Rief W, Barke A, et al. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain 2015;156:1003–7. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kurppa K, Viikari-Juntura E, Kuosma E, et al. Incidence of tenosynovitis or peritendinitis and epicondylitis in a meat-processing factory. Scand J Work Environ Health 1991;17:32–7. 10.5271/sjweh.1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gagge AP, Stolwijk JA, Hardy JD. Comfort and thermal sensations and associated physiological responses at various ambient temperatures. Environ Res 1967;1:1–20. 10.1016/0013-9351(67)90002-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Näyhä S, Hassi J, Jousilahti P, et al. Cold-related symptoms among the healthy and sick of the general population: national FINRISK study data, 2002. Public Health 2011;125:380–8. 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sundstrup E, Jakobsen MD, Brandt M, et al. Central sensitization and perceived indoor climate among workers with chronic upper-limb pain: cross-sectional study. Pain Res Treat 2015;2015:793750 10.1155/2015/793750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oksa J, Sormunen E, Koivukangas U, et al. Changes in neuromuscular function due to intermittently increased workload during repetitive work in cold conditions. Scand J Work Environ Health 2006;32:300–9. 10.5271/sjweh.1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sormunen E, Rissanen S, Oksa J, et al. Muscular activity and thermal responses in men and women during repetitive work in cold environments. Ergonomics 2009;52:964–76. 10.1080/00140130902767413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Racinais S, Oksa J. Temperature and neuromuscular function. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010;20(Suppl 3):1–18. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01204.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Oksa J, Ducharme MB, Rintamäki H. Combined effect of repetitive work and cold on muscle function and fatigue. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2002;92:354–61. 10.1152/jappl.2002.92.1.354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mäkinen TM. Nordic Society for Arctic medicine. The effects of cold adaptation on human performance. Int J Circumpolar Health 2003;62:445 10.3402/ijch.v62i4.17589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lötters F, Burdorf A, Kuiper J, et al. Model for the work-relatedness of low-back pain. Scand J Work Environ Health 2003;29:431–40. 10.5271/sjweh.749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hoozemans MJM, Knelange EB, Frings-Dresen MHW, et al. Are pushing and pulling work-related risk factors for upper extremity symptoms? A systematic review of observational studies. Occup Environ Med 2014;71:788–95. 10.1136/oemed-2013-101837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Andorsen OF, Ahmed LA, Emaus N, et al. A prospective cohort study on risk factors of musculoskeletal complaints (pain and/or stiffness) in a general population. The Tromsø study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0181417 10.1371/journal.pone.0181417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Niedhammer I, Chastang J-F, David S, et al. The contribution of occupational factors to social inequalities in health: findings from the National French SUMER survey. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:1870–81. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li CY, Sung FC. A review of the healthy worker effect in occupational epidemiology. Occup Med (Lond) 1999;49:225–9. 10.1093/occmed/49.4.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Krokstad S, Johnsen R, Westin S. Social determinants of disability pension: a 10-year follow-up of 62 000 people in a Norwegian County population. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:1183–91. 10.1093/ije/31.6.1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Andersen RK, Jordfald B. Arbeidstakere I byggenæringen I 2008 OG 2014. Report No: 39 Fafo, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.