Abstract

Objectives

Our study aimed to examine the longitudinal association between social participation and both mortality and the need for long-term care (LTC) simultaneously.

Design

A prospective cohort study with 9.4 years of follow-up.

Setting

Six Japanese municipalities.

Participants

The participants were 15 313 people who did not qualify to receive LTC insurance at a baseline based on the data from the Aichi Gerontological Evaluation Study (AGES, 2003–2013). They received a questionnaire to measure social participation and other potential confounders. Social participation was defined as participating in at least one organisation from eight categories.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcomes were classified into three categories at the end of the 9.4 years observational period: living without the need for LTC, living with the need for LTC and death. We estimated the adjusted OR (AOR) using multinomial logistic regression analyses with adjustment for possible confounders.

Results

The primary analysis included 9741 participants. Multinomial logistic regression analysis revealed that social participation was associated with a significantly lower risk of the need for LTC (AOR 0.82, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.97) or death (AOR 0.78, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.88).

Conclusions

Social participation may be associated with a decreased risk of the need for LTC and mortality among elderly patients.

Keywords: successful ageing, preventative healthcare, physical function, social capital

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The present study was based on a large cohort of community-dwelling older people which enabled us to accurately measure participants’ need to receive care or survival with a median follow-up of 9.4 years and few dropouts.

Using the combination of the two outcomes, we showed the prognosis of older people with or without social participation.

The limitation of the study was that the cohort questionnaire only measured social participation at a baseline, and no measurements were obtained from the same participants during the follow-up periods.

Further research will be required to evaluate the association between outcomes and social participation based on the measurement in several points, and then to examine whether an intervention of some social activity may decrease both the need for long-term care and death in older people.

Introduction

An ageing society is a major issue in high-income countries as well as in some low-income and middle-income countries. In 2015, the United Nations reported that there were almost 901 million people over the age of 60 years, comprising 12% of the global population.1 Japan is experiencing the most rapid global increase of an older population, with about 33% of its population consisting of people over the age of 60.2 One of the major concerns of a rapidly ageing society is the social burden of older people who need care. In 2015, >5.6 million people, or 36.2% of people aged 65 years and over, required care within the Japanese healthcare system.3 These populational transitions would have enormous influence on our access to high-quality health and social care. WHO has proposed the concept of ‘Healthy Ageing’, defined as ‘the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age’,4 for all people to live long and healthy lives.

Recently, social capital has received increased attention because it may have some potential for preventing functional decline and death. Social participation has been defined by Putnam,5 Berkman6 and various other researchers. It was defined by WHO as a component of the social determinant of health and it contains various kinds of forms as follows: informing people with balanced, objective information; consulting, whereby the affected community provides feedback; involving or working directly with communities; collaborating by partnering with affected communities in each aspect of the decision-making process, including the development of alternatives and the identification of solutions and empowering people by ensuring that communities retain ultimate control over the key decisions that affect their well-being.7 Previous studies have shown that social participation among older people is associated with a reduced risk of the need for long-term care (LTC)8–11 or death.12–16 However, previous studies have several limitations. For example, in studies that examined the relationship between social participation and the need for LTC, patients who died were treated as censored cases or were not described in the results.8–11 Other studies that investigated the association between social participation and mortality did not simultaneously analyse functional disability and death. For example, one study13 investigated the relationship between social participation and functional decline and death, but these two outcomes were analysed separately instead of in a single model. Both functional disability and death are relevant outcomes for older people. No long-term, follow-up study has thus far elucidated the proportion of participants who require LTC or who die based on their degree of social participation.

We conducted a longitudinal cohort study to investigate the association between social participation and the need for LTC and death using the Aichi Gerontological Evaluation Study (AGES).

Methods

Design and setting

The relationship between social participation and the long-term outcomes of older people was analysed based on the AGES longitudinal data.17 Participants were 65 years and older and did not have physical or cognitive impairments at the baseline. The participants were randomly selected from six municipalities (Handa city, Tokoname city, Agui town, Taketoyo town, Minamichita town and Mihama town) in Aichi prefecture, Japan. If the municipal population was ≤5000, all people in the municipality were selected as participants. If the municipal population was >5000, 5000 persons were randomly sampled using the resident registration list. In 2003, participants answered a self-reported questionnaire by mail, including questions about their health status, social participation and socioeconomic status for the baseline survey data; they were followed up until the development of functional decline, eligibility for LTC or death. More information on AGES is available elsewhere.17 Written informed consent was assumed with the voluntary return of the questionnaires.

Study population

Eligible participants were individuals over the age of 65 years who answered the AGES self-reported questionnaire in 2003. Participants who qualified to receive long-term care at the beginning of the observational period were excluded. We also excluded those who could not independently perform the activities of daily living (ADL) or who did not answer the questionnaire related to social participation.

Social participation

We divided social participation into eight types based on a previous study9: neighbourhood associations/senior citizen clubs/fire-fighting teams (local community), hobby groups (hobby), sports groups or clubs (sports), political organisations or groups (politics), industrial or trade associations (industry), religious organisations or groups (religion), volunteer groups (volunteer) and citizen or consumer groups (citizen). The questions used to measure social participation were based on the Japanese version of the General Social Survey (JGSS).18 Participants answered ‘currently participate’ or ‘do not currently participate’ for each type of social participation at the baseline. In the primary analysis, participants were categorised in the non-participation group (no participation in any group) or the social participation group (participation in at least one group).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the need for LTC or death at the end of the 9.4 years observational period. The need for LTC was determined based on a formal evaluation in accordance with routine criteria that combine a home visit evaluation with the judgement of the primary doctor.19 Applicants or their family members essentially apply to their municipality for certification of LTC when the applicants find themselves in the need of some care support or when users’ family members recognise that they need to introduce care support in the user’s life. When applicants are certified, they would be classified as Needed Support or the need for LTC. The applicants with lighter functional decline (eg, those who are ambulatory but find it difficult to walk long distances) are classified as Needed Support. The LTC certification is generally considered as the ADL that the applicant partially or wholly depends on others for.20 We defined the reference category as ‘without the need for LTC’ and this category included those who were not certified or certified as Needed Support. Secondary outcomes were the incidence of the need for LTC or death at 2 and 5 years. We derived information on the certification of the need for LTC or death from the database provided by the municipalities. Data were also obtained regarding whether participants moved out of the area; we excluded participants who moved out at the end of the observational period before the start of the primary analysis.

Statistical analysis

We described the baseline characteristics using means and SD for the continuous variables and percentages for the categorical variables. Additionally, we showed the proportion of participants with each outcome by social participation group (yes or no), as well as by the number of types of social participation. In the primary analysis, we performed multinomial logistic regression analyses with adjustment for possible confounders (age per 5-year increment), gender, living alone, educational attainment (more than >9 years), smoking, alcohol consumption, walking time (>30 min/day), annual household income (>3 000 000 yen per year) and the number of comorbidities (one or more than two) to examine the relationship between social participation and the development of each outcome (the need for LTC or death) during the 9.4 years follow-up. Missing data for all variables were not imputed.

In the secondary analysis, we examined the relationship between each type of social participation and outcomes (the need for LTC or death) during the 9.4 years follow-up using multinomial logistic regression with adjustment for the same confounders as above. Using the model above, we then investigated the number of types of social participation and outcomes. Participants were placed into one of four categories: people with no social participation, one type of social participation, two types of social participation and at least three or more types of social participation. Furthermore, we conducted multinomial logistic analysis regarding outcomes at 2 and 5 years with adjustment for the same confounders as above.

Finally, we performed a sensitivity analysis, changing one of the outcome definitions from the development of LTC to the certification of Needed Support using a multinomial logistic model with adjustment for the same confounders as listed above. Certification for Needed Support indicates that ADL and instrumental ADL could mostly be performed independently, but some daily support was required. The tendency for functional decline is generally milder than those who need LTC.

All analyses were performed using STATA V.14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). A p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement

No participants were involved in establishing the research question, outcome measures including the study design, and interpretation. We will disseminate the results through the website and on social media.

Results

Baseline characteristics

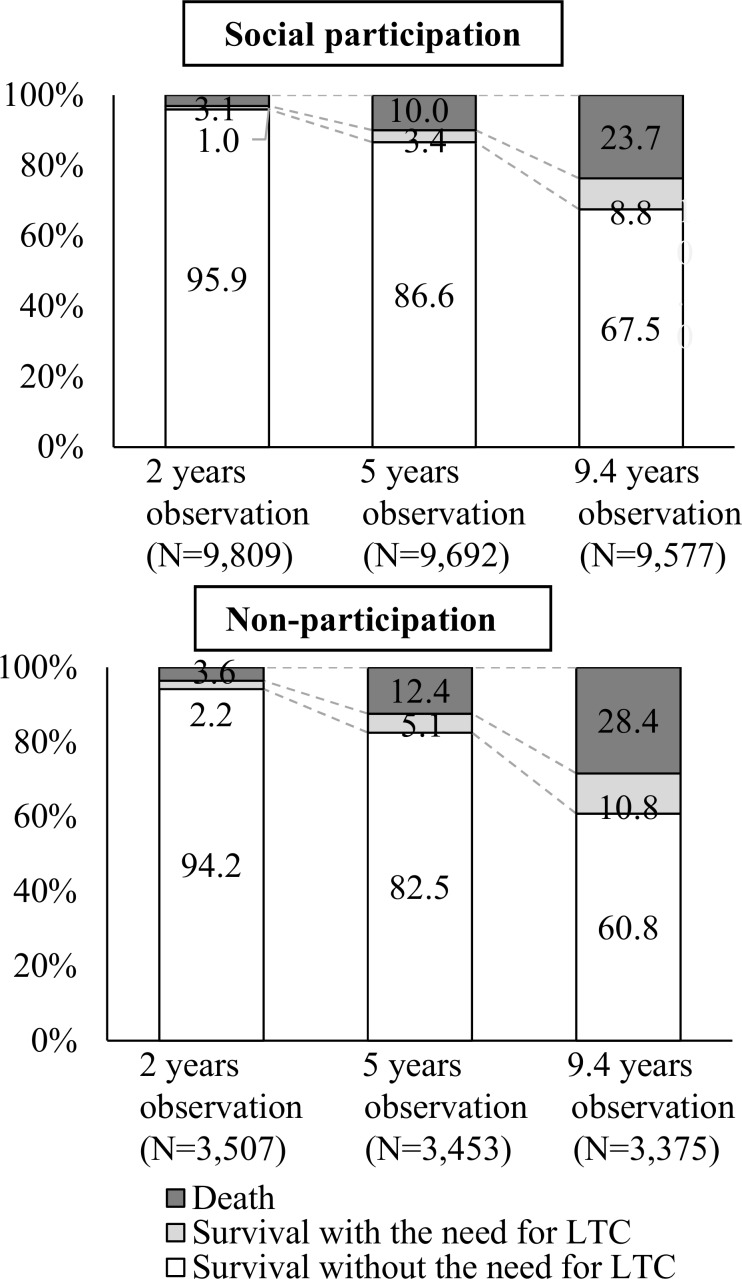

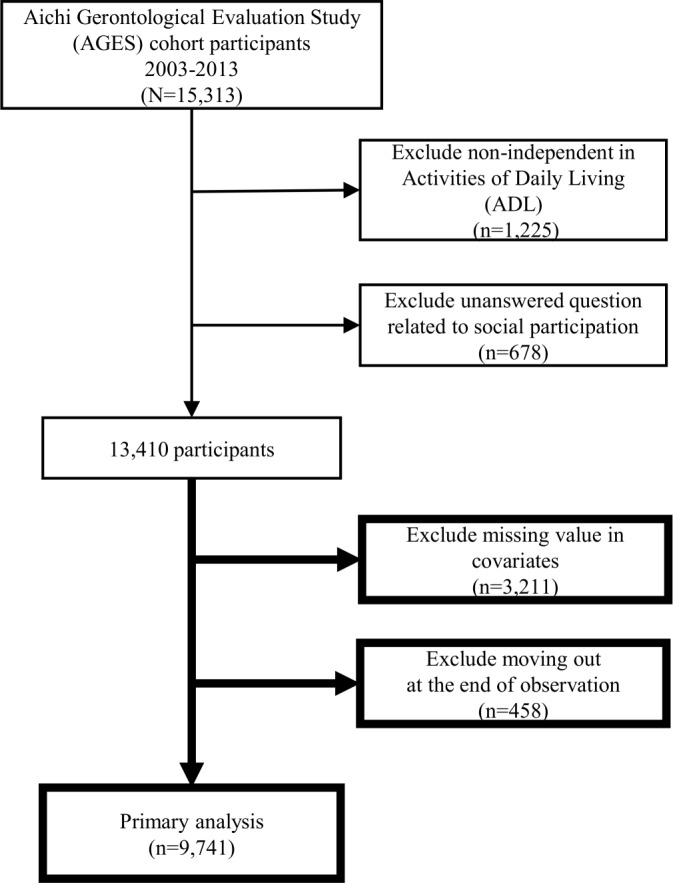

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the study. Among 15 313 participants, 9863 (73.6%) were in the social participation group. The mean age was 72.5 in participants with social participation and 72.9 in those without social participation. The highest proportion of social participation was seen in local community and hobby groups. Around 10% of the social participation group participated in political groups, industrial groups, religious groups and volunteer groups. The proportion of higher educational attainment and higher household income was about 10% higher in the social participation group. Thus, participants who engaged in social participation were likely to present higher educational attainment and higher household income than those who were not (online supplementary table S1). Figure 2 shows the proportion of participants who developed each outcome at 2, 5 and 9.4 years. At the end of the observational period, in those engaged in social participation, 6463 participants (67.5%) lived without the need for LTC, 839 (8.8%) lived with the need for LTC and 2275 participants (23.7%) had died.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

Figure 2.

Incidence of the need for long-term care (LTC) and death at 2, 5 and 9.4 years.

bmjopen-2019-030500supp001.pdf (78KB, pdf)

Primary analysis

The primary analysis included 9741 participants. Multivariable multinomial logistic regression analysis showed that participants who engaged in social participation were significantly less likely to develop the need for LTC or die than those who were not engaged in social participation during the 9.4 years follow-up period: adjusted OR (AOR) 0.82, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.97; AOR 0.78, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.88, respectively (table 1).

Table 1.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis: association between social participation and the need for LTC or death at 9.4 years (n=9741) AOR (95% CI)—reference category: without the need for LTC and death

| Variable† | Survival with the need for LTC | Death |

| 845 (8.7) | 2443 (25.1) | |

| AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Social participation (yes) | 0.82 (0.69 to 0.97)* | 0.78 (0.70 to 0.88)** |

| Age (per 5 years) | 2.06 (1.93 to 2.19)** | 2.16 (2.06 to 2.26)** |

| Gender (men) | 0.80 (0.67 to 0.95)* | 1.98 (1.76 to 2.24)** |

| Family (living alone) | 1.03 (0.78 to 1.31) | 0.91 (0.74 to 1.11) |

| Educational attainment (>9 years) |

0.92 (0.79 to 1.08) | 0.94 (0.85 to 1.05) |

| Smoking (yes) | 1.50 (1.19 to 1.88)** | 1.74 (1.51 to 2.00)** |

| Alcohol (yes) | 1.05 (0.86 to 1.30) | 0.92 (0.81 to 1.05) |

| Walking time (>30 min/day) | 0.80 (0.69 to 0.94)** | 0.73 (0.66 to 0.81)** |

| Household income (>3 000 000 yen/year) |

0.88 (0.75 to 1.03) | 0.96 (0.86 to 1.07) |

| One comorbidity | 1.39 (1.10 to 1.75)** | 1.28 (1.10 to 1.50)** |

| Two or more comorbidities | 1.59 (1.27 to 1.98)** | 1.67 (1.45 to 1.94)** |

Note: LTC, long-term care; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01.

†Adjusted age, gender, living alone or not, educational attainment, smoking, alcohol, walking time, household income, and the number ofcomorbidities.; AOR, adjusted OR; LTC, long-termcare.

AOR, adjusted OR; LTC, long-term care.

Secondary analysis

Multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the relationship between each type of social participation and the outcomes. The results showed that participants in local community, hobby and sports groups were significantly less likely to die than those without participation in these groups (AOR 0.85, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.99; AOR 0.71, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.85 and AOR 0.65, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.80, respectively). On the other hand, participants in religious organisations or groups were significantly more likely to develop the need for LTC than those without such participation (AOR 1.33, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.65) (table 2).

Table 2.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis: association between each type of social participation and the incidence of the need for LTC or death at 9.4 years (n=9741) AOR (95% CI)—reference category: without the need for LTC and death

| Social participation group, n (%)† | Survival with the need for LTC |

Death |

| AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| 845 (8.7) | 2443 (25.1) | |

| Local community 5692 (58.4) | 0.85 (0.73 to 0.99)* | 0.84 (0.76 to 0.93)* |

| Hobby groups 3101 (31.8) | 0.71 (0.60 to 0.85)* | 0.70 (0.63 to 0.79)* |

| Sports groups or clubs 2067 (21.1) | 0.65 (0.52 to 0.80)* | 0.64 (0.56 to 0.73)* |

| Political organisations or groups 820 (8.4) | 1.08 (0.82 to 1.43) | 1.04 (0.87 to 1.25) |

| Industrial or trade associations 1040 (10.7) | 1.02 (0.79 to 1.33) | 1.01 (0.86 to 1.20) |

| Religious organisations or groups 1114 (11.4) | 1.33 (1.08 to 1.65)* | 1.15 (0.98 to 1.34) |

| Volunteer groups 1052 (10.8) | 0.86 (0.66 to 1.13) | 0.98 (0.83 to 1.17) |

| Citizen or consumer groups 456 (4.7) | 1.03 (0.71 to 1.48) | 1.15 (0.90 to 1.46) |

*p<0.05.

†Adjusted age, gender, living alone or not, educational attainment, smoking, alcohol, walking time, household income and the number of comorbidities.

AOR, adjusted OR; LTC, long-term care.

With regard to the association between the number of types of social participation and the incidence of the need for LTC or death at the 9.4 years follow-up, results showed that participants who engaged in two types of social participation were less likely to die than those without any participation (AOR 0.76, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.88). Participants who engaged in three or more types of social participation were less likely to develop the need for LTC or die than participants without any participation (AOR 0.67, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.85; AOR 0.67, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.78, respectively) (table 3).

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis: relationship between the number of types of social participation and the need for LTC and death at 9.4 years (n=9741) AOR (95% CI)—reference category: without the need for LTC and death

| No. of participants, n (%) | Survival with the need for LTC |

Death |

| AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Social participation group, n (%)† | 845 (8.7) | 2443 (25.1) |

| One social group, 2994 (30.7) | 0.86 (0.71 to 1.05) | 0.88 (0.77 to 1.01) |

| Two social groups, 2192 (22.5) | 0.92 (0.74 to 1.13) | 0.76 (0.65 to 0.88)* |

| Three or more social groups, 2174 (22.3) | 0.67 (0.53 to 0.85)* | 0.67 (0.57 to 0.78)* |

*p<0.01.

†Adjusted age, gender, living alone or not, educational attainment, smoking, alcohol, household income, walking time and the number of comorbidities.

AOR, adjusted OR; LTC, long-term care.

After 2 years of follow-up, participants who were engaged in social participation were significantly less likely to develop the need for LTC than those without participation (AOR 0.45, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.64). After 5 years of follow-up, participants who engaged in social participation were less likely to develop the need for LTC and die than those without social participation (AOR 0.68, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.86; AOR 0.83, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.96, respectively) (online supplementary table S2).

Sensitivity analysis

In sensitivity analysis, the results indicated that participants who participated in social groups were less likely to develop the need for Needed Support than those who were not (AOR 0.93, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.07); however, the results were not statistically significant (online supplementary table S3).

Discussion

This study showed the association between social participation and the need for LTC or death during 9.4 years of follow-up. At the end of the follow-up period, participants who were engaged in social participation were more likely to remain functionally independent than participants who were not engaged in social participation. The results were significant in all of the primary outcomes in the multinomial logistic regression analysis adjusted for confounding factors. Furthermore, a relationship was seen between the number of types of social participation and each outcome, suggesting that engaging in many varieties of participation may be more effective on the health of participants than a few varieties of participation. The secondary analyses based on the 2 and 5 years follow-up were similar to the results of the primary analysis. Sensitivity analysis was performed by examining the results from living with and without mild impairment and using the outcome criteria as a person’s history of certification of Needed Support. The findings were similar to those of the main analysis.

The results of the present study support previous studies, but these studies evaluated only one outcome (the need for LTC or death)8–16 and did not take both outcomes into account in a single model.14 The present study is the first to focus on the combination of two relevant outcomes in the same model.

We defined and classified social participation from the baseline questionnaire to a binary variable denoting the presence or absence of any social participation and adopted it onto the main analysis. Furthermore, we conducted secondary analysis using the original eight-type classification of social participation based on the JGSS questionnaire.18 The results of the secondary analysis showed that several types of social participation were associated with lower incidences of LTC and mortality. Our results indicated that specific types of social participation may be effective for LTC and mortality. Although it was difficult for us to know the detailed contents of these forms of participation from the baseline questionnaire, local community, hobby groups and sports groups or clubs may be effective in contributing to participants’ future health. In particular, our results indicate that participation in sports groups is the most effective form of social participation listed in our questionnaire. Previous studies have revealed that participation in sports clubs means that participants would be less likely to develop the need for LTC than if exercising alone.8 Therefore, participation in sports clubs may contribute to healthy ageing so we might as well recommend the national and local politics to grow more interests in the participation in sports clubs or groups.

The mechanisms regarding why and how social participation affects healthy ageing and death are not yet known, but growing evidence suggests that social participation stimulates the body and brain, helping participants remain highly functional.12 21 Another study suggested that participants who engage in social participation may have easier access to social support.22 With regard to biomedical mechanisms, social participation may suppress inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6 or C reactive protein and reduce physical stress.23 Further studies are needed to reveal the underlying mechanisms regarding the relationship between social participation and healthy ageing, that is, what kind of form or content of participation may sustain the health of older people or the frequency of social participation that may maintain a participant’s health or their health-related behaviours. To analyse the relationship between a participant’s behaviours and health-related outcomes will be beneficial for the individual’s health, and for policy makers who are trying to promote social participation.

The strength of the present study is that it is the first study to use composite outcomes of both the need for care support and death to examine the relationship between social participation and the elderly’s relevant outcomes. This study found that social participation may reduce both the need for care support and death. It is also worthwhile to describe the proportions of each outcome in this long-term study. By using outcomes that include the presence or absence of healthy ageing, we were able to show the prognosis in detail after the long-term observation of older people. Moreover, the AGES cohort is a relatively large-scale study. The proportion of participants lost to follow-up was low (3.4%), even after 9.4 years.

However, there are several limitations to this study. First, the measurement of social participation was only performed at the baseline. No measurements were obtained during the follow-up periods. Second, social participation is a subset of social capital as described by Putnam.5 It has been measured in various ways as an indicator that measures the quality of the social network. The questions in this study were designed to measure only the presence or absence of social participation. We could not use the information regarding the intensity and duration of social participation. Third, there was no information about dementia or cerebrovascular disease in this study, which are two of the main causes of death among elderly patients.24 Fourth, multinomial logistic analysis may be superior to previous methods to compare the elderly’s need for LTC and death without the need for LTC, but other methods such as the competing risk regression model may be suggested when we focus separately on the incidence of LTC. Fifth, this study used data taken from a single area; thus, the generalisability of results to other areas or countries cannot be assumed. Finally, the present study is observational; thus, we could not adjust for the effect of unknown confounding factors in the association between social participation and outcomes, or prove a causal effect between social participation and outcomes.

In conclusion, this study indicated that social participation may reduce the risk of death, and reduce the risk of developing a disability. Living with disability in the midst of a super-ageing society impairs the quality of life of the individual, and places an additional burden on society. Further research is needed to examine whether an intervention that encourages social participation may reduce death and functional disability among the elderly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all staff members in each study area and in the central office for their painstaking efforts in conducting the baseline survey and follow-up. The authors would like to thank everyone who participated in the survey. The authors would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for its English-language editing services.

Footnotes

Contributors: ST and TO conceived of the idea. ST, YY, SS and SF contributed to the study design. TO and KK contributed to defining the data variables and the acquisition of the data. ST and YY performed statistical analysis, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. TO, KK, SS and SF reviewed the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final submission.

Funding: This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP18390200 and Health Labour Sciences Research Grant, Comprehensive Research on Ageing and Health (H22-Choju-Shitei-008) from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

Disclaimer: The grant sponsors had no role in the design, methods, participant recruitment, data collection, analysis or preparation of this paper.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Kyoto University Ethics Committee approved this study (approval number: R0425). The Nihon Fukushi University Ethics Committee originally approved the AGES projects (approval number: 13–14).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: The data were acquired from the JAGES study. All enquiries are to be addressed to the data management committee via e-mail: dataadmin.ml@jages.net. All JAGES datasets have ethical or legal restrictions for public deposition due to the inclusion of sensitive information from human participants. Following the regulation of local governments that cooperated in our survey, the JAGES data management committee has imposed these restrictions on the data.

References

- 1. United Nations World population prospects (online). Available: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/publications/files/key_findings_wpp_2015.pdf [Accessed 17 Nov 2017].

- 2. Statistics of Japan. List of statistical tables (online). Available: http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/GL38020103.do?_toGL38020103_&tclassID=000001077438&cycleCode=0&requestSender=estat [Accessed 5 Dec 2017].

- 3. Cabinet office government of Japan. annual report on the aging Society, 2016. Available: http://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/whitepaper/w-2016/html/gaiyou/index.html [Accessed 7 Mar 2017].

- 4. Who | what is healthy ageing? who, 2018. Available: https://www.who.int/ageing/healthy-ageing/en/ [Accessed 29 Jun 2019].

- 5. Putnam RD. Bowling alone: America's declining social capital. Journal of Democracy 1995;6:65–78. 10.1353/jod.1995.0002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berkman LF. The role of social relations in health promotion. Psychosom Med 1995;57:245–54 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7652125 10.1097/00006842-199505000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Who | social participation. who, 2013. Available: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/countrywork/within/socialparticipation/en/ [Accessed 2 Jul 2019].

- 8. Kanamori S, Kai Y, Kondo K, et al. . Participation in sports organizations and the prevention of functional disability in older Japanese: the ages cohort study. PLoS One 2012;7:e51061 10.1371/journal.pone.0051061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kanamori S, Kai Y, Aida J, et al. . Social participation and the prevention of functional disability in older Japanese: the JAGES cohort study. PLoS One 2014;9:e99638 10.1371/journal.pone.0099638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murata C, Saito T, Tsuji T, et al. . A 10-year follow-up study of social ties and functional health among the old: the ages project. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:pii:E717 10.3390/ijerph14070717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saito M, Aida J, Kondo N, et al. . Reduced long-term care cost by social participation among older Japanese adults: a prospective follow-up study in JAGES. BMJ Open 2019;9:e024439 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aida J, Kondo K, Hirai H, et al. . Assessing the association between all-cause mortality and multiple aspects of individual social capital among the older Japanese. BMC Public Health 2011;11:499 10.1186/1471-2458-11-499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Ascherio A, et al. . A prospective study of social networks in relation to total mortality and cardiovascular disease in men in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health 1996;50:245–51. 10.1136/jech.50.3.245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hsu HC. Does social participation by the elderly reduce mortality and cognitive impairment? Aging Ment Health 2007;11:699–707. 10.1080/13607860701366335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Glass TA, de Leon CM, Marottoli RA, et al. . Population based study of social and productive activities as predictors of survival among elderly Americans. BMJ 1999;319:478–83. 10.1136/bmj.319.7208.478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Väänänen A, Murray M, Koskinen A, et al. . Engagement in cultural activities and cause-specific mortality: prospective cohort study. Prev Med 2009;49:142–7. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nishi A, Kondo K, Hirai H, et al. . Cohort profile: the ages 2003 cohort study in Aichi, Japan. J Epidemiol 2011;21:151–7. 10.2188/jea.JE20100135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Iwai N. Japanese General social surveys (JGSS) and measurements of family and gender attitudes: results of the 1st preliminary survey. Kazoku Syakaigaku Kenkyu 2001;12:261–70. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tsutsui T, Muramatsu N. Care-needs certification in the long-term care insurance system of Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:522–7. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53175.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matsuda S, Muramatsu K, Hayashida K. Eligibility classification logic of the Japanese long term care insurance. Asian Pacific Journal of Disease Management 2011;5:65–74. 10.7223/apjdm.5.65 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, et al. . Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108:3017–22. 10.1073/pnas.1015950108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang W, Chen M. Psychological distress of older Chinese: exploring the roles of activities, social support, and subjective social status. J Cross Cult Gerontol 2014;29:37–51. 10.1007/s10823-013-9219-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Glei DA, Goldman N, Ryff CD, et al. . Social relationships and inflammatory markers: an analysis of Taiwan and the U.S. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:1891–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Statistics and Information Department, Minister’s Secretariat, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Graphical Review of Japanese Household (online). Available: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/dl/20-21-h25.pdf [Accessed 7 Mar 2017].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030500supp001.pdf (78KB, pdf)