Abstract

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is associated with an increased fracture risk despite normal-to-increased bone mineral density, suggesting reduced bone quality. Exercise may be effective in reducing fracture risk by ameliorating muscle dysfunction and reducing risk of fall, though it is unclear whether it can improve bone quality.

Methods and analysis

The ‘Study to Weigh the Effect of Exercise Training on BONE quality and strength (SWEET BONE) in T2D’ is an open-label, assessor-blinded, randomised clinical trial comparing an exercise training programme of 2-year duration, specifically designed for improving bone quality and strength, with standard care in T2D individuals. Two hundred T2D patients aged 65–75 years will be randomised 1:1 to supervised exercise training or standard care, stratified by gender, age ≤ or >70 years and non-insulin or insulin treatment. The intervention consists of two weekly supervised sessions, each starting with 5 min of warm-up, followed by 20 min of aerobic training, 30 min of resistance training and 20 min of core stability, balance and flexibility training. Participants will wear weighted vests during aerobic and resistance training. The primary endpoint is baseline to end-of-study change in trabecular bone score, a parameter of bone quality consistently shown to be reduced in T2D. Secondary endpoints include changes in other potential measures of bone quality, as assessed by quantitative ultrasound and peripheral quantitative CT; bone mass; markers of bone turnover; muscle strength, mass and power; balance and gait. Falls and asymptomatic and symptomatic fractures will be evaluated over 7 years, including a 5-year post-trial follow-up. The superiority of the intervention will be assessed by comparing between-groups baseline to end-of-study changes.

Ethics and dissemination

This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee. Written informed consent will be obtained from all participants. The study results will be submitted for peer-reviewed publication.

Trial registration number

Keywords: type 2 diabetes, bone quality, bone mass, bone fractures, exercise, physical fitness

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study investigating whether a specifically designed exercise training programme of 2-year duration is effective in improving bone quality and strength in patients with type 2 diabetes, thus reducing the increased fracture risk characterising these individuals.

A wide range of parameters of bone quality and strength is assessed, together with measures of bone mass and muscle mass, strength and power, which all may affect fracture risk, and falls and fractures over an extended 7-year period.

All the physicians, exercise specialists and outcome assessors have been specifically trained for conducting this trial and participated in a pilot study aimed at setting up the trial protocol.

There are no data on the effect of exercise on the primary endpoint trabecular bone score, a surrogate measure of bone quality.

Generalisability and implementation in clinical practice of this approach will require further investigation and validation in different cohorts or contexts.

Introduction

Risk of fracture is significantly increased in type 1 diabetes (T1D) and, to a lower extent, in type 2 diabetes (T2D).1 2 Nevertheless, bone mineral density (BMD) was reported to be normal or even increased in patients with T2D, whereas it was found almost consistently reduced in T1D individuals.1 Notably, in patients with T2D, the increase in fracture risk remained after adjustment for BMD3–5 and also for falls,3 4 6 which are more frequent in older individuals with T2D than in those without.7 In addition, as compared with non-diabetic individuals, patients with T2D have a higher T-score for a similar fracture risk.8 While the preserved bone mass may account for the lower fracture risk in T2D versus T1D, a reduced bone quality has been claimed to explain the discrepancy between normal BMD and increased fracture risk in patients with T2D.1 2

Bone quality is determined by: (A) bone architecture, including geometry (macroarchitecture) and microarchitecture; and (B) material properties, including mineralisation and collagen cross-links which, in turn, are influenced by bone turnover as well as by accumulation of microdamage and microstructural discontinuities.9 10 While conventional dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) measures bone mass, several techniques have been proposed for non-invasive assessment of bone quality.11 12 The trabecular bone score (TBS) is a grey-level texture measurement based on two-dimensional projection images acquired during a DXA lumbar spine scan.13 It was consistently found to be reduced in T2D patients with fracture versus those without14 and in T2D versus non-diabetic individuals15–20 and to predict fracture risk independently of BMD.15 Quantitative ultrasound (QUS) provides an estimate of BMD,21 which predicted fracture risk better than DXA-derived BMD in older women with T2D22; in addition, QUS evaluates microarchitecture and material properties.23 24 However, QUS-derived bone structure measures were not consistently lower in T2D patients with versus those without fracture22 25 and in T2D versus non-diabetic individuals.26 27 In addition to volumetric BMD (vBMD), low-resolution and high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) provides measures of bone geometry and architecture.11 Higher cortical porosity and lower calculated strength were reported in T2D patients with versus those without fracture28 29 and in T2D versus non-diabetic individuals.30–33

Physical activity (PA)/exercise has been suggested as an effective tool for improving bone health in individuals at high fracture risk. It is known that both compressive loading from weight bearing and muscle contraction deform the osteocytes, which function as strain transducers by signalling osteoblasts, osteoclasts and other cells to produce or break down bone.34 35 Appropriate types, amounts and directions of strain result in bone mass maintenance, bone formation and/or changes in bone geometry that improve bone strength.36

Exercise was shown to improve BMD to a relatively small but clinically significant extent.37 There is also a great deal of evidence from observational studies that higher PA levels are associated with fewer fractures in community-dwelling populations,38 and postmenopausal women who performed spinal extension exercises showed a lower incidence of vertebral fractures.39 Combination of diet and exercise was shown to provide greater improvement in physical function than either intervention alone.40 Moreover, exercise training prevented the increase in bone turnover and attenuated the decrease in hip BMD associated with diet-induced weight loss,41 and resistance exercise attenuated diet-induced decrease in muscle mass and BMD more than aerobic training.42 Resistance exercise was also shown to decrease falls and risk of falls, especially when focused on strengthening the hip and ankle muscles involved in balance maintenance.43

These observations indicate that PA/exercise, especially of resistant type, may be effective in reducing fracture risk in patients with T2D by ameliorating muscle mass, strength and quality44 and reducing falls and risk of fall.7 However, it is unclear whether PA/exercise may reduce fracture risk also by directly improving bone health in individuals with preserved BMD, such as those with T2D. Indeed, to date, there are no data on whether exercise training is effective in ameliorating bone quality and whether improved quality results in increased bone strength and reduced fracture risk in patients with T2D.

The ‘Study to Weigh the Effect of Exercise Training on BONE quality and strength (SWEET BONE) in T2D’ is aimed at investigating the efficacy of a specific exercise intervention programme of 2-year duration on parameters of bone quality and strength in patients with T2D.

Methods and analysis

Trial design

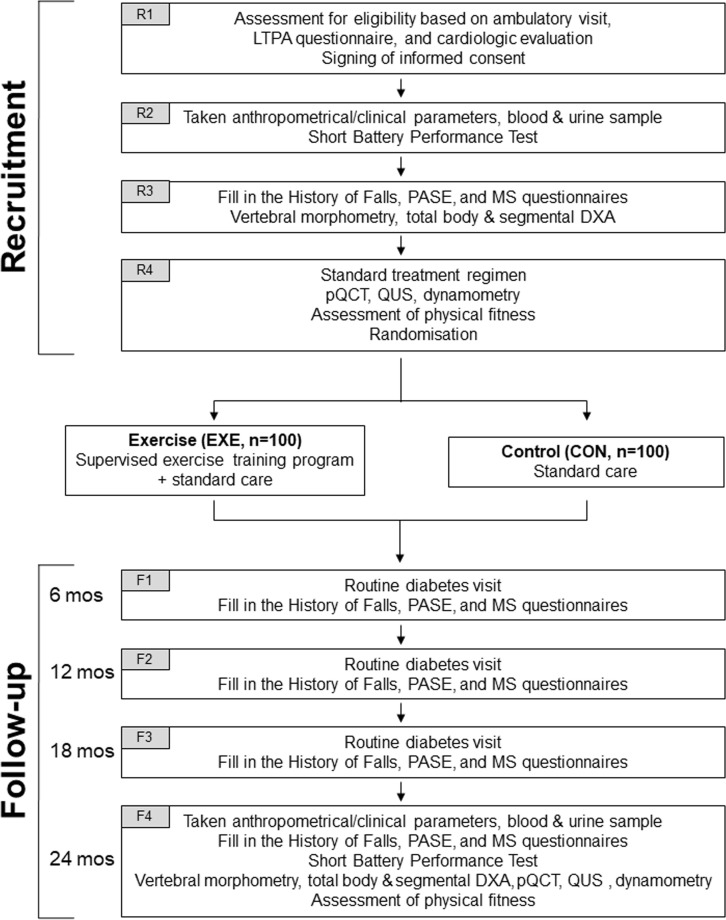

The SWEET BONE is an open-label, assessor-blinded, parallel, superiority randomised clinical trial (RCT) comparing a specifically designed exercise intervention programme with standard care in T2D individuals. The trial flow chart is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. DXA, dual‐energy X‐ray absorptiometry; LTPA, leisure time physical activity; MS, musculoskeletal; PASE, Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly; pQCT, peripheral quantitative; qUS, quantitative ultrasound.

Participants

This study will enrol patients with T2D (defined by the American Diabetes Association criteria45) of ≥5 year duration, of both sexes, aged 65–75 years. Additional requirements will be: physically inactive (ie, insufficient amounts of PA according to current guidelines)46 and sedentary lifestyle (ie, ≥8 hours/day spent in a sitting or reclining posture)47 from ≥6 months; body mass index (BMI) 27–40 kg/m2; ability to walk 1.6 km without assistance; a Short Battery Performance Test score ≥4; and eligibility after cardiological evaluation.

The criteria listed in box 1 will be used to exclude individuals with conditions limiting or contraindicating PA, reduce lifespan and affect conduct of the trial and/or the safety of intervention. Among exclusion criteria, there are treatment with antifracture agents, oestrogens, aromatase inhibitors, testosterone, corticosteroids and/or glitazones; previous documented non-traumatic fractures; spinal deformity index (SDI) >5 (>2 in a single vertebra); and a T score <−2.5 at DXA. Individuals with haemoglobin (Hb) A1c >9.0%, blood pressure (BP) >150/90 mm Hg and/or vitamin D <10 ng/mL will be re-evaluated for eligibility after appropriate treatment.

Box 1. Exclusion criteria.

Unable or unwilling to give informed consent or communicate with local study staff.

Current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder or hospitalisation for depression in the past 6 months.

Self-reported alcohol or substance abuse within the past 12 months.

Self-reported inability to walk two blocks.

Musculoskeletal disorders or deformities that may interfere with participation in the intervention.

History of central nervous dysfunction such as haemiparesis, myelopathies and cerebral ataxia.

Clinical evidence of vestibular dysfunction.

Postural hypotension defined as a fall in BP when changing position of >20 mm Hg (systole) or >10 mm Hg (diastole).

Cancer requiring treatment in the past 5 years, except for cancers that have clearly been cured or in the opinion of the investigator carry an excellent prognosis (eg, stage 1 cervical cancer).

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

End-stage liver disease.

-

Chronic diabetic complications:

Recent major acute cardiovascular event, including heart attack, stroke/transient ischemicischaemic attack(s), revascularisation procedure or participation in a cardiac rehabilitation programme within the past 3 months.

Preproliferative and proliferative retinopathy.

Macroalbuminuria and/or eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Severe motor and sensory neuropathy.

Diabetic foot with history of ulcer.

-

Cardiovascular disease at cardiological examination:

History of cardiac arrest.

History of pulmonary embolism in the past 6 months.

Unstable angina pectoris or angina pectoris at rest.

Resting HR <45 beats/min or >100 beats/min.

Complex ventricular arrhythmia at rest or with exercise.

Uncontrolled atrial fibrillation (HR ≥100 beats/min).

NYHA Class III or IV congestive heart failure.

Acute myocarditis, pericarditis or hypertrophic myocardiopathy.

Left bundle branch block or cardiac pacemaker.

ECG treadmill test suggestive of myocardial ischaemia.

-

Poor glycaemic and BP control.

Haemoglobin (Hb) A1c >9.0%.

BP >150/90 mm Hg.

-

Bone abnormalities.

Vitamin D <10 ng/mL.

Treatment with antifracturative agents, oestrogens, aromatase inhibitors, testosterone, corticosteroids and/or glitazones.

Previous documented non-traumatic fractures.

SDI >5 (and >2 in a single vertebra).

T score ≤−2.5 at spine/hip at DXA.

Conditions not specifically mentioned above at the discretion of the clinical site.

Participants with HbA1c or BP above the indicated threshold will be receive appropriate treatment and will be re-evaluated after 3 months. Patients with vitamin D levels <10 ng/dL will be treated with cholecalciferol 25 000 IU/week for 6 weeks and will be re-evaluated 2 weeks after the last dose.

BP, blood pressure; DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, heart rate; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SDI, total spine deformity index.

A sample of 50 non-diabetic individuals meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria reported above (except for T2D-related criteria) and matched 1:4 by age, gender and BMI will serve as controls for baseline measures.

Investigators

All the SWEET-BONE physicians, exercise specialists and outcome assessors (see online supplementary appendix A) have been specifically trained for conducting this RCT and participated in a pilot study aimed at setting up the trial protocol.

bmjopen-2018-027429supp001.pdf (162.4KB, pdf)

To minimise dropout and reduce the attrition bias due to missing data, both physicians and exercise specialists have been instructed on how to promote participant retention in the trial, that is, contact participants at regular intervals, keep up to date contact information for participants and collect complete data for the primary and secondary outcomes, regardless of whether individuals continue to receive the assigned intervention.

Recruitment

Starting on 1 November 2018, 200 patients will be recruited at the Diabetes Unit of Sant’Andrea University Hospital, a tertiary referral, outpatient diabetes clinic in Rome, Italy. All patients attending the clinic will be evaluated for eligibility. The recruitment process will include four visits designated as R1, R2, R3 and R4.

On R1, eligible patients will be identified based on medical history, clinical examination and results of the Minnesota leisure-time PA questionnaire. Then, patients will be asked to sign an informed consent and will be registered in the SWEET-BONE database available at http://www.metabolicfitness.it/. Finally, patients will undergo a cardiological examination, including a resting ECG and, based on clinical judgement, an echocardiogram and/or an ECG treadmill test.

On R2, baseline anthropometrical and clinical parameters and blood and urine samples for biochemical testing will be taken. Subsequently, participants will perform a Short Battery Performance Test and undergo measurement of ankle-brachial index and fundus evaluation. Finally, patients will attend a run-in session for familiarisation with testing devices and protocols for the assessment of physical fitness.

On R3, patients will be asked to fill in the History of Falls questionnaire, the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) questionnaire and a questionnaire for musculoskeletal (MS) symptoms. Then, participants will undergo X-ray of dorso-lumbar spine for vertebral morphometry, and total body and segmental DXA. Finally, they will attend another run-in session for familiarisation prior to the assessment of physical fitness.

On R4, patients will be prescribed a standard treatment regimen. Then, they will undergo the following procedures: pQCT, calcaneal QUS and dynamometry. Finally, patients will be subjected to the assessment of physical fitness and will be informed about group assignment.

Randomisation

Patients will be randomised 1:1 to supervised exercise training on top of standard care (exercise (EXE) group; n=100) versus standard care (control (CON), group; n=100) for 24 months.

Randomisation will be stratified by gender (males vs females), age (65–70 vs 71–75 years) and type of diabetes treatment (non-insulin vs insulin), using a permuted-block randomisation software that randomly varies the block size. To ensure allocation concealment, randomisation will be centralised at the Centre for Outcomes Research and Clinical Epidemiology (CORESEARCH), and the group assignment of newly recruited patients will be communicated to the investigators by telephone call.

After randomisation, participants, physicians and exercise specialists will not be blinded to group assignment, as blinding is unfeasible in exercise intervention studies.

Follow-Up

Participants from both groups will attend four follow-up visits, designated as F1, F2, F3 and F4, at month 6, 12, 18 and 24, respectively.

On F1, F2 and F3, patients will undergo a routine diabetes visit, with eventual adjustment of dietary and pharmacological prescriptions and will be asked to fill in the History of Falls, PASE and MS questionnaires.

On F4, end-of-study anthropometrical and clinical parameters and blood and urine samples for biochemical testing will be taken. Then, participants will be asked to fill in the History of Falls, PASE and MS questionnaires and to perform a Short Battery Performance Test. On different days, patients will undergo X-ray of dorso-lumbar spine for vertebral morphometry, total body and segmental DXA, pQCT, calcaneal QUS, dynamometry and assessment of physical fitness.

Post-trial follow-up

Participants will be followed every 6 months for additional 5 years for routine diabetes visits. On these occasions, they will be asked to provide clinical records on eventual fractures, to fill in the History of Falls, PASE and MS questionnaires and to perform a Short Battery Performance Test. At the end of the 5-year post-trial follow-up, participants will undergo vertebral morphometry to detect asymptomatic fractures.

Intervention

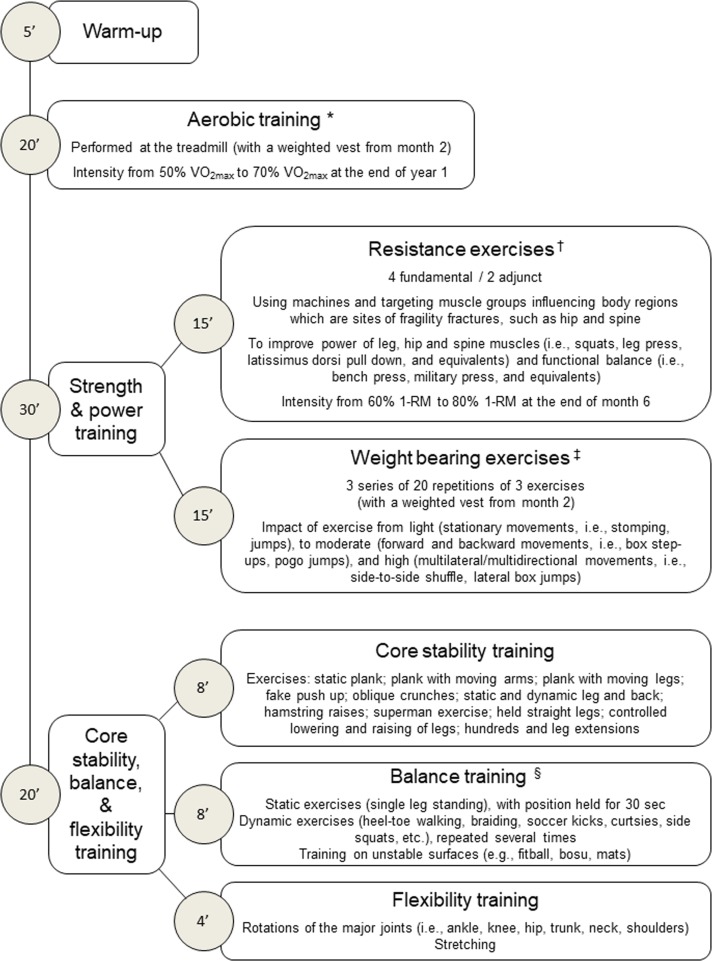

The training programme for the EXE group will consist of two 75 min weekly sessions, supervised by an exercise specialist in the gym facility of the Metabolic Fitness Association (figure 2). We conducted a pilot study on a small sample of patients with T2D meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria for this RCT in order to set up the training programme.

Figure 2.

Sequence of exercises during each supervised exercise training session. *Intensity of aerobic exercise will be adjusted according to improvements in predicted VO2max, as recorded every 6 months. †Intensity of resistance exercise will be adjusted according to improvements in 1-RM, as recorded every 6 months; new resistance exercises will be introduced every 12 weeks to maintain patient’s adherence, and the velocity of execution during the concentric phase of the movement will be progressively increased to enhance muscle power. ‡Height of jumps and amplitude of movements of weight-bearing exercise will be also progressively increased. §Difficulty level of balance training will be gradually increased by performing the exercises with closed eyes, reducing the support area, changing visual fixation (eg, head rotations), varying the centre of mass (eg, limb raising) or adding a manual or cognitive task. 1-RM, one-repetition maximum; VO2max, maximal oxygen consumption.

Each session will start with 5 min of warm up, followed by 20 min of aerobic training using treadmill. Then, patients will perform 30 min of resistance (strength and power) training consisting of six resistance exercises using machines and targeting muscle groups influencing body regions that are sites of fragility fractures (15 min) and three 20-repetition series of three different ‘weight bearing’ exercises (15 min). The session will end with 20 min of core stability training (8 min), which improves the ability to control the position and movement of the central portion of the body and targets the deep abdominal muscles that assist in posture maintenance and arm and leg movements, followed by balance (8 min) and flexibility (4 min) training.

The exercise intensity and difficulty level will be increased gradually in order to ensure safety and prevent attrition, as shown in a previous RCT48 and confirmed by the pilot study. In particular, the intensity of aerobic and resistance exercise will be increased from light to moderate and adjusted according to improvements in physical fitness. The velocity of execution of resistance exercises during the concentric phase of the movement, the impact, height of jumps and amplitude of movements of weight bearing exercises, and the difficulty level of balance training will be also progressively increased.

Starting at month 2, a weighted vest will be worn during each session (while performing aerobic training and weight bearing exercises) and also outside the sessions (for at least 1 hour and during three 10-repetition series of step-up and sit-to-stand in three non-training days every week). Patients will be asked to record in a daily diary the time spent wearing the weighted vest outside the sessions. Weight of vests will be 2% of body weight and will be increased by 2% every 6 months (ie, up to 8%).

Standard care

All patients will be subjected to a treatment regimen aimed at achieving glycaemic, lipid, BP and body weight targets, as established by current guidelines and including nutritional therapy and glucose-lowering, lipid-lowering and BP-lowering agents as needed.45 Vitamin D will be supplemented to maintain levels higher than 30 ng/mL.

At intermediates routine diabetes visits, drugs will be adjusted to attain target levels, following a prespecified algorithm, and changes will be recorded into the SWEET-BONE database.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint is baseline to end-of-study change in TBS, based on previous reports showing that it is consistently lower in T2D versus non-diabetic individuals.15–20

Secondary endpoints include: (A) other potential measures of bone quality, as assessed by QUS and pQCT; (B) bone mass (BMD); (C) markers of bone turnover; (D) body composition; (E) muscle strength, mass and power; (F) balance and gait; (G) number of falls; and (H) asymptomatic and symptomatic fractures. Falls and fractures will be evaluated over 7 years (ie, including the 5-year post-trial follow-up).

PA level, cardiorespiratory fitness, flexibility, MS symptoms, modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, medications and coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke 10 year risk scores will be also evaluated.

The assessors of outcome measures will be blinded to group assignment.

Measurements

Bone mass and quality

Bone mass will be assessed by DXA scans of the lumbar spine (L1–L4) and total femur using Hologic QDR 4500 W 2000 (Hologic, Bedford, Massachusetts, USA). Areal BMD g/cm2) in the lumbar spine and femoral neck will be recorded, and the corresponding T scores and Z scores will be obtained. Composite indices of femoral neck strength will be also computed, as previously reported.49 TBS will be then measured using the Hologic TBS Insight software (Hologic). Calcaneal QUS measurements will be performed using the Sahara Clinical Bone Sonometer (Technologic, Turin, Italy). Broadband ultrasound attenuation (dB/MHz) and speed of sound (SOS; m/s) will be measured, and the quantitative ultrasound index will be then calculated. BMD will be also estimated from QUS measurements (eBMD; g/cm2). Bone density and macroarchitecture will be evaluated using an XCT-2000 pQCT scanner (Norland Stratec, Stratec, Pforzheim, Germany).50 Slices (2.5 mm) will be obtained at the 4%, 14%, 38% and 66% sites of the left tibia and at the 4% site of the non-dominant radius. At the metaphyses (4% site) of tibia and radius, total vBMD and trabecular-vBMD (mg/cm3) will be measured. At the 14% site of the tibia, cortical bone area (mm2) and cortical bone mineral content (mg/cm), two markers of resistance to compressive and tensile loads, will be measured, and the section modulus will be calculated from the antero-posterior, latero-lateral and polar moments of inertia (Ix, Iy and Ip, respectively) and used to obtain the stress–strain index (SSI; mm3), a surrogate measure of resistance to bending (xSSI and ySSI) and torsional (pSSI) loads. At the 38% site of the tibia, cortical vBMD mg/cm3) and total cross-sectional area (mm2) will measured, together with calculation of cortical thickness (mm) and circularity index, a proxy of tibial geometrical load adaptation.

Markers of bone turnover

Serum calcium and phosphorus, 25OH vitamin D and parathyroid hormone will be measured, together with the following markers of bone turnover: total and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, osteocalcin and procollagen I intact N-terminal for bone formation, and C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b, sclerostin and Dickkopf-1 for bone resorption. These measurements will be centralised at the Laboratory of Clinical Chemistry of Sant’Andrea University Hospital, using the methods reported in table 1.

Table 1.

Methods for measurements of markers of bone turnover

| Analyte | Method | Manifacturer |

| Ca | Colorimetric spectrophotometric | Architect, Abbot Diagnostics, Lake Forest, IL, USA |

| P | Colorimetric spectrophotometric | Architect, Abbot Diagnostics, Lake Forest, IL, USA |

| 25OH Vitamin D | Competitive ECLIA | Liaison, DiaSorin SpA, Saluggia, Italy |

| PTH | ECLIA | Liaison, DiaSorin SpA, Saluggia, Italy |

| Total ALP | Colorimetric spectrophotometric | Architect, Abbot Diagnostics, Lake Forest, Illinois, USA |

| Bone-specific ALP | ECLIA | Liaison, DiaSorin SpA, Saluggia, Italy |

| Osteocalcin | ELISA | RayBiotech, Norcross, Georgia, USA |

| PINP | ELISA | RayBiotech, Norcross, Georgia, USA |

| CTX-1 | ELISA | RayBiotech, Norcross, Georgia, USA |

| TRAcP 5b | ELISA | RayBiotech, Norcross, Georgia, USA |

| Sclerostin | ELISA | RayBiotech, Norcross, Georgia, USA |

| DKK-1 | ELISA | RayBiotech, Norcross, Georgia, USA |

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; TRAcP 5b, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b;Ca, calcium; CTX-1, C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen; DKK-1, Dickkopf-1; ECLIA, chemiluminescent immunoassay;p, phosphorus; PINP, procollagen I intact N-terminal; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

Body composition

Total body DXA will be used to evaluate body composition, with measurement of total body lean mass and total body fat mass.

Muscle strength

Isometric muscle strength will be also assessed by means of a strain gauge tensiometer (Digimax, Mechatronic GmbH, Germany), as previously reported.51 Maximal voluntary contractions are performed at the shoulder press (Technogym, Gambettola, Italy) along the sagittal plan, with a 45° and 90° angle at the elbow and between the upper arm and the trunk, respectively, for the upper body, and at the leg extension machine (Technogym), with a 90° angle at the knee and the hip, for the lower body. Values will be expressed in Nm for two arms.

Muscle cross-sectional area

The cross-sectional areas of muscles of the leg will be measured by pQCT at the 66% site of the tibia at the end of bone assessments.52

Physical fitness

Physical fitness will be evaluated at baseline, end-of-study and, in the EXE group, also at month 6, 12 and 18, in order to adjust training loads. Cardiorespiratory fitness, muscle fitness and flexibility will be assessed by a submaximal evaluation of oxygen consumption at 80% of the maximal heart rate to predict maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max), a maximal repetition (or 5–8 RM) to predict one-repetition maximum (1-RM) and a standard bending test, respectively, as previously reported.48 53

Balance, gait and power

A ‘Short Battery Performance Test’ will be performed for the assessment of balance (side-by-side stand, semitandem stand and tandem stand), gait (gait speed test) and power (chair stand test).54

Number of falls

Falls will be recorded using the 17-item History of Falls questionnaire (see online supplementary appendix B1).55

Symptomatic and asymptomatic fractures

Patients will be interviewed to record symptomatic fractures, which will be adjudicated based on clinical and radiographic records. Asymptomatic fractures will be identified by vertebral morphometry.

PA level

The level of PA will be evaluated throughout the study by asking patients to fill in the PASE questionnaire (see online supplementary appendix B2), a validated instrument for the measurement of PA level in individuals aged ≥65 years.56 The amount of supervised exercise in the EXE group will be measured as previously reported.48 53

MS symptoms

MS symptoms will be evaluated by a 50-item self-report questionnaire (see online supplementary appendix B3).57

Cardiovascular risk factors and scores

The BMI will be calculated from body weight and height, while waist circumference will be taken at the umbilicus and BP will be recorded with a sphygmomanometer after a 5 min rest with the patient seated. Blood and urine samples will be taken for measuring the biochemical parameters reported in table 2 at the Laboratory of Clinical Chemistry of Sant’Andrea University Hospital. Global and fatal CHD and stroke 10-year risk scores will be calculated using the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study risk engine.58 Cardiovascular risk factors and scores will be assessed at baseline and end of study.

Table 2.

Methods for measurements of cardiovascular risk factors

| Analyte | Method | Manufacturer |

| HbA1c | HPLC (Adams TMA1C HA-8160) | Menarini Diagnostics, Florence, Italy |

| FPG | VITROS 5,1 FS Chemistry System | Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics Inc, Raritan, New Jersey, USA |

| Triglycerides | VITROS 5,1 FS Chemistry System | Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics Inc, Raritan, New Jersey, USA |

| Total cholesterol | VITROS 5,1 FS Chemistry System | Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics Inc, Raritan, New Jersey, USA |

| HDL cholesterol | VITROS 5,1 FS Chemistry System | Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics Inc, Raritan, New Jersey, USA |

| hs-CRP | VITROS 5,1 FS Chemistry System | Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics Inc, Raritan, New Jersey, USA |

| Blood count | VITROS 5,1 FS Chemistry System | Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics Inc, Raritan, New Jersey, USA |

| Uric acid | VITROS 5,1 FS Chemistry System | Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics Inc, Raritan, New Jersey, USA |

| Serum creatinine | VITROS 5,1 FS Chemistry System | Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics Inc, Raritan, New Jersey, USA |

| Urinary albumin | mAlb VITROS | Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics Inc, Raritan, New Jersey, USA |

| Urinary creatinine | VITROS 5,1 FS Chemistry System | Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics Inc, Raritan, New Jersey, USA |

LDL cholesterol will be calculated using the Friedewald formula (https://www.mdcalc.com/ldl-calculated), whereas glomerular filtration rate will be estimated from serum creatinine by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation (http://www.qxmd.com/calculate-online/nephrology/ckd-epi-egfr).

FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C reactive protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Adverse events

Adverse events will be reported at intermediate visits and, for EXE participants, also at supervised sessions, by completing a standard form.

The risk of injuries and other adverse events during the training sessions will be covered by an insurance (N. 390-01583709-14010, HDI-Gerling Industrie Versicherung AG, Leipzig, Germany).

Data collection, storage and security

Data collected into the SWEET-BONE database will be saved to a password-protected server in the Metabolic Fitness Association and accessed only by members of the research team.

Once uploaded to the server, data will be securely deleted from the recording devices. Patient questionnaire data will be made anonymous and stored in locked filing cabinets.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation was based on our pilot study showing that TBS was 1.225±0.085 (SD) in T2D individuals. To detect a between-group difference of 0.045 in TBS (ie, effect size=0.50) with statistical power of 90% (α=0.05) by two-sided two-sample equal variance t-test, 86 patients per arm are needed. A sample of 200 patients allows to tolerate a 14% dropout rate.

The χ2 or, where appropriate, the Fisher’s exact test, for categorical variables, and the Student’s t-test or the corresponding non-parametric Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables will be used to compare patients’ characteristics at baseline. The intention-to-treat analysis will be applied to all randomised patients. The superiority of the intervention on the primary and secondary endpoints will be assessed by mixed models for repeated measures. Prespecified subgroup analyses will be conducted by gender, age (65–70 vs 71–75 years) and type of diabetes treatment (non-insulin vs insulin).

To account for change in medication throughout the study period, which might affect bone parameters, we will perform both multiple regression and sensitivity analyses. In the regression models, the dependent variable will be represented by baseline to end-of-study changes. Treatment at baseline and treatment initiation during the study will be included in the model as dichotomous variables (yes vs no), whereas drug dosage will be not taken into consideration. Sensitivity analysis will be conducted by comparing study arms after exclusion of patients who modified treatment.

Repeated measures models with an autoregressive correlation type matrix make an assumption of missing at random and account for both missingness at random and potential correlation within participants, as they allow evaluating all individuals, including those with incomplete data.59 Finally, to guarantee replicability and avoid outcome selective reporting, a fully specified statistical analysis plan will be written before unmasking.

Statistical analyses will be performed by at the CORESEARCH using SAS software release V.9.3, and the statistical significance level will be set at α<0.05 (two tailed). Because of the potential for type 1 error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary endpoints should be interpreted as exploratory.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or public will not be involved in the study, except for the burden of the intervention, which will be assessed by patients themselves and reported to the exercise specialist at each session, in order to identify the appropriate training modalities to minimise the risk of injury or adverse events.

Ethics and dissemination

The research protocol (version #3, 28 February 2013), which follows the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials guideline, complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. It has been registered with ClinicalTrials.gov on 20 April 2014 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02421393) (see online supplementary appendix C). Important protocol amendments (eg, changes to eligibility criteria, outcomes and analyses) will be communicated to relevant parties, that is, investigators, trial participants, trial registry and the ethics committee.

All participants will provide written informed consent (see online supplementary appendix D) following verbal and written explanation of the study protocol and the opportunity to ask questions. Participants will not be provided with an honorarium and will be free to withdraw from the trial at any time without prejudice to future treatment.

To the best of our knowledge, the SWEET-BONE is the first study investigating whether a specifically designed exercise training programme is effective in improving bone quality and strength in patients with T2D, thus potentially reducing the increased fracture risk characterising these individuals despite preserved bone mass. The beneficial effects on bone quality would be additional to those on muscle strength and mass and risk of fall, which may reduce per se the risk of fracture. Potential pitfalls include the lack of data on TBS change over time in T2D individuals and the impact of exercise on this surrogate measure of bone quality. However, an age-dependent reduction in TBS of up to 0.5%/year has been reported in the general population60–63 and such decrease is likely to be accelerated in patients with T2D, given the large reduction in TBS detected in T2D versus non-diabetic individuals.15–20 64 In addition, in osteoporotic individuals, TBS was shown to be markedly increased (by ~4% in 2–3 years) by osteoanabolic agents such as teriparatide, though less than spine BMD,65–67 whereas antiresorptive agents, which merely increase bone mineralisation, were virtually ineffective.63 Therefore, exercise, by virtue of its potential osteoanaboolic effect, is likely to influence positively TBS,68 consistent with a recent cross-sectional study showing that people with higher levels of objectively measured PA had higher TBS (and BMD).69 Finally, generalisability and implementation in clinical practice of this approach will require further investigation and validation in different cohorts or contexts.

Results will be presented at scientific meetings and published in peer-reviewed journals. All publications and presentations related to the study will be authorised and reviewed by the study investigators. The ICMJE Recommendations will be adopted for authorship.70

After publication of results, public access to the full protocol, participant-level dataset and statistical code will be eventually granted on request.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Collaborators: See online supplementary appendix A for the complete list of the SWEET_BONE Investigators.

Contributors: SB, FC and GP conceived and designed the study. All the other authors made substantial contributions to specific parts of the protocol: recruitment and follow-up programme (MV and LB), training programme (MS, GO, GR and SZ), imaging procedures (GA, LP and AL), quantitative ultrasound and peripheral quantitative CT protocols (CRR, JH and VD), biochemical testing panel (PC) and statistical analysis plan (AN). GP drafted the manuscript; SB, FGC, MS, CRR, GA, JH, GO, GR, VD, PC, LP, AL, MV, LB, SZ and AN revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors have given their final approval of the manuscript to be published.

Funding: This work is supported by the Metabolic Fitness Association, Monterotondo, Rome, Italy, by the EFSD/Novo Nordisk A/S Programme for Diabetes Research in Europe 2019 to GP, and, for the pilot study, by a grant from the Italian Ministry of Health (RF-2010-2310812) to GP.

Disclaimer: The funding sources have no role in design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the report for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Vestergaard P. Discrepancies in bone mineral density and fracture risk in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes--a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 2007;18:427–44. 10.1007/s00198-006-0253-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Janghorbani M, Van Dam RM, Willett WC, et al. . Systematic review of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of fracture. Am J Epidemiol 2007;166:495–505. 10.1093/aje/kwm106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schwartz AV, Sellmeyer DE, Ensrud KE, et al. . Older women with diabetes have an increased risk of fracture: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:32–8. 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Strotmeyer ES, Cauley JA, Schwartz AV, et al. . Nontraumatic fracture risk with diabetes mellitus and impaired fasting glucose in older white and black adults: the health, aging, and body composition study. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1612–7. 10.1001/archinte.165.14.1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Napoli N, Strotmeyer ES, Ensrud KE, et al. . Fracture risk in diabetic elderly men: the MrOS study. Diabetologia 2014;57:2057–65. 10.1007/s00125-014-3289-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bonds DE, Larson JC, Schwartz AV, et al. . Risk of fracture in women with type 2 diabetes: the women's health Initiative observational study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:3404–10. 10.1210/jc.2006-0614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schwartz AV, Hillier TA, Sellmeyer DE, et al. . Older women with diabetes have a higher risk of falls: a prospective study. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1749–54. 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schwartz AV, Vittinghoff E, Bauer DC, et al. . Association of BMD and FRAX score with risk of fracture in older adults with type 2 diabetes. JAMA 2011;305:2184–92. 10.1001/jama.2011.715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fonseca H, Moreira-Gonçalves D, Coriolano H-JA, et al. . Bone quality: the determinants of bone strength and fragility. Sports Med 2014;44:37–53. 10.1007/s40279-013-0100-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Farr JN, Khosla S. Determinants of bone strength and quality in diabetes mellitus in humans. Bone 2016;82:28–34. 10.1016/j.bone.2015.07.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rubin MR, Patsch JM. Assessment of bone turnover and bone quality in type 2 diabetic bone disease: current concepts and future directions. Bone Res 2016;4 10.1038/boneres.2016.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jiang N, Xia W. Assessment of bone quality in patients with diabetes mellitus. Osteoporos Int 2018;29:1721–36. 10.1007/s00198-018-4532-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bousson V, Bergot C, Sutter B, et al. . Trabecular bone score (tbs): available knowledge, clinical relevance, and future prospects. Osteoporos Int 2012;23:1489–501. 10.1007/s00198-011-1824-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhukouskaya VV, Ellen-Vainicher C, Gaudio A, et al. . The utility of lumbar spine trabecular bone score and femoral neck bone mineral density for identifying asymptomatic vertebral fractures in well-compensated type 2 diabetic patients. Osteoporos Int 2016;27:49–56. 10.1007/s00198-015-3212-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leslie WD, Aubry-Rozier B, Lamy O, et al. . Tbs (trabecular bone score) and diabetes-related fracture risk. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2013;98:602–9. 10.1210/jc.2012-3118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dhaliwal R, Cibula D, Ghosh C, et al. . Bone quality assessment in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Osteoporos Int 2014;25:1969–73. 10.1007/s00198-014-2704-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim JH, Choi HJ, Ku EJ, et al. . Trabecular bone score as an indicator for skeletal deterioration in diabetes. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2015;100:475–82. 10.1210/jc.2014-2047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Choi YJ, Ock SY, Chung Y-S. Trabecular bone score (tbs) and TBS-Adjusted fracture risk assessment tool are potential supplementary tools for the discrimination of morphometric vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Clinical Densitometry 2016;19:507–14. 10.1016/j.jocd.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Holloway KL, De Abreu LLF, Hans D, et al. . Trabecular bone score in men and women with impaired fasting glucose and diabetes. Calcif Tissue Int 2018;102:32–40. 10.1007/s00223-017-0330-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rianon N, Ambrose CG, Buni M, et al. . Trabecular bone score is a valuable addition to bone mineral density for bone quality assessment in older Mexican American women with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Densitom 2018;21:355–9. 10.1016/j.jocd.2018.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Glüer CC. Quantitative ultrasound techniques for the assessment of osteoporosis: expert agreement on current status. The International quantitative ultrasound consensus group. J Bone Miner Res 1997;12:1280–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Patel S, Hyer S, Tweed K, et al. . Risk factors for fractures and falls in older women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Calcif Tissue Int 2008;82:87–91. 10.1007/s00223-007-9082-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Padilla F, Jenson F, Bousson V, et al. . Relationships of trabecular bone structure with quantitative ultrasound parameters: in vitro study on human proximal femur using transmission and Backscatter measurements. Bone 2008;42:1193–202. 10.1016/j.bone.2007.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bouxsein ML, Radloff SE. Quantitative ultrasound of the calcaneus reflects the mechanical properties of calcaneal trabecular bone. J Bone Miner Res 1997;12:839–46. 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.5.839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yamaguchi T, Yamamoto M, Kanazawa I, et al. . Quantitative ultrasound and vertebral fractures in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Bone Miner Metab 2011;29:626–32. 10.1007/s00774-011-0265-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tao B, Liu J-M, Zhao H-Y, et al. . Differences between measurements of bone mineral densities by quantitative ultrasound and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in type 2 diabetic postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:1670–5. 10.1210/jc.2007-1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bulló M, Garcia-Aloy M, Basora J, et al. . Bone quantitative ultrasound measurements in relation to the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus in a cohort of elderly subjects at high risk of cardiovascular disease from the PREDIMED study. J Nutr Health Aging 2011;15:939–44. 10.1007/s12603-011-0046-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Patsch JM, Burghardt AJ, Yap SP, et al. . Increased cortical porosity in type 2 diabetic postmenopausal women with fragility fractures. J Bone Miner Res 2013;28:313–24. 10.1002/jbmr.1763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Samelson EJ, Demissie S, Cupples LA, et al. . Diabetes and deficits in cortical bone density, microarchitecture, and bone size: Framingham HR-pQCT study. J Bone Miner Res 2018;33:54–62. 10.1002/jbmr.3240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burghardt AJ, Issever AS, Schwartz AV, et al. . High-Resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomographic imaging of cortical and trabecular bone microarchitecture in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:5045–55. 10.1210/jc.2010-0226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Farr JN, Drake MT, Amin S, et al. . In vivo assessment of bone quality in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes. J Bone Miner Res 2014;29:787–95. 10.1002/jbmr.2106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Paccou J, Ward KA, Jameson KA, et al. . Bone microarchitecture in men and women with diabetes: the importance of cortical porosity. Calcif Tissue Int 2016;98:465–73. 10.1007/s00223-015-0100-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nilsson AG, Sundh D, Johansson L, et al. . Type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with better bone microarchitecture but lower bone material strength and poorer physical function in elderly women: a population-based study. J Bone Miner Res 2017;32:1062–71. 10.1002/jbmr.3057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arnett TR. Osteocytes: regulating the mineral reserves? J Bone Miner Res 2013;28:2433–5. 10.1002/jbmr.2119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kerschnitzki M, Kollmannsberger P, Burghammer M, et al. . Architecture of the osteocyte network correlates with bone material quality. J Bone Miner Res 2013;28:1837–45. 10.1002/jbmr.1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sinaki M, Pfeifer M, Preisinger E, et al. . The role of exercise in the treatment of osteoporosis. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2010;8:138–44. 10.1007/s11914-010-0019-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Howe TE, Shea B, Dawson LJ, et al. . Exercise for preventing and treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;32 10.1002/14651858.CD000333.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Karlsson M. Does exercise reduce the burden of fractures? A review. Acta Orthop Scand 2002;73:691–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sinaki M, Itoi E, Wahner HW, et al. . Stronger back muscles reduce the incidence of vertebral fractures: a prospective 10 year follow-up of postmenopausal women. Bone 2002;30:836–41. 10.1016/S8756-3282(02)00739-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Villareal DT, Chode S, Parimi N, et al. . Weight loss, exercise, or both and physical function in obese older adults. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1218–29. 10.1056/NEJMoa1008234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shah K, Armamento-Villareal R, Parimi N, et al. . Exercise training in obese older adults prevents increase in bone turnover and attenuates decrease in hip bone mineral density induced by weight loss despite decline in bone-active hormones. J Bone Miner Res 2011;26:2851–9. 10.1002/jbmr.475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Villareal DT, Aguirre L, Gurney AB, et al. . Aerobic or resistance exercise, or both, in dieting obese older adults. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1943–55. 10.1056/NEJMoa1616338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gillespie LD, Gillespie WJ, Robertson MC, et al. . Interventions for preventing falls in elderly people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Orlando G, Balducci S, Bazzucchi I, et al. . Neuromuscular dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: underlying mechanisms and effect of resistance training. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2016;32:40–50. 10.1002/dmrr.2658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in Diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care 2018;41:S1–159.29222369 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Inoue M, Iso H, Yamamoto S, et al. . Daily total physical activity level and premature death in men and women: results from a large-scale population-based cohort study in Japan (JPHC study). Ann Epidemiol 2008;18:522–30. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sedentary Behaviour Research Network Letter to the editor: standardized use of the terms "sedentary" and "sedentary behaviours". Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2012;37:540–2. 10.1139/h2012-024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Balducci S, Zanuso S, Nicolucci A, et al. . Effect of an intensive exercise intervention strategy on modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetic subjects. A randomized controlled trial: the Italian diabetes and exercise study (ides). Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1794–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Karlamangla AS, Barrett-Connor E, Young J, et al. . Hip fracture risk assessment using composite indices of femoral neck strength: the Rancho bernardo study. Osteoporos Int 2004;15:62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Russo CR, Lauretani F, Seeman E, et al. . Structural adaptations to bone loss in aging men and women. Bone 2006;38:112–8. 10.1016/j.bone.2005.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Balducci S, Sacchetti M, Orlando G, et al. . Correlates of muscle strength in diabetes. the study on the assessment of determinants of muscle and bone strength abnormalities in diabetes (samba). Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2014;24:18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Erlandson MC, Lorbergs AL, Mathur S, et al. . Muscle analysis using pQCT, DXA and MRI. Eur J Radiol 2016;85:1505–11. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Balducci S, Zanuso S, Massarini M, et al. . The Italian diabetes and exercise study (ides): design and methods for a prospective Italian multicentre trial of intensive lifestyle intervention in people with type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2008;18:585–95. 10.1016/j.numecd.2007.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, et al. . Lower-Extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med 1995;332:556–62. 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Talbot LA, Musiol RJ, Witham EK, et al. . Falls in young, middle-aged and older community dwelling adults: perceived cause, environmental factors and injury. BMC Public Health 2005;5:86 10.1186/1471-2458-5-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, et al. . The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:153–62. 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Balducci S, Vulpiani MC, Pugliese L, et al. . Effect of supervised exercise training on musculoskeletal symptoms and function in patients with type 2 diabetes: the Italian diabetes exercise study (ides). Acta Diabetol 2014;51:647–54. 10.1007/s00592-014-0571-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stevens RJ, Kothari V, Adler AI, et al. . The UKPDS risk engine: a model for the risk of coronary heart disease in type II diabetes (UKPDS 56). Clin Sci 2001;101:671–9. 10.1042/cs1010671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dufour R, Winzenrieth R, Heraud A, et al. . Generation and validation of a normative, age-specific reference curve for lumbar spine trabecular bone score (tbs) in French women. Osteoporos Int 2013;24:2837–46. 10.1007/s00198-013-2384-8 10.1007/s00198-013-2384-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Iki M, Fujita Y, Tamaki J, et al. . Trabecular bone score may improve FRAX® prediction accuracy for major osteoporotic fractures in elderly Japanese men: the Fujiwara-kyo osteoporosis risk in men (FORMEN) cohort study. Osteoporos Int 2015;26:1841–8. 10.1007/s00198-015-3092-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Krieg MA, Aubry-Rozier B, Hans D, et al. . Effects of anti-resorptive agents on trabecular bone score (tbs) in older women. Osteoporos Int 2013;24:1073–8. 10.1007/s00198-012-2155-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Leslie WD, Majumdar SR, Morin SN, et al. . Change in trabecular bone score (tbs) with antiresorptive therapy does not predict fracture in women: the Manitoba BMD cohort. J Bone Miner Res 2017;32:618–23. 10.1002/jbmr.3054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ho-Pham LT, Nguyen TV. Association between trabecular bone score and type 2 diabetes: a quantitative update of evidence. Osteoporos Int 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Senn C, Günther B, Popp AW, et al. . Comparative effects of teriparatide and ibandronate on spine bone mineral density (BMD) and microarchitecture (tbs) in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: a 2-year open-label study. Osteoporos Int 2014;25:1945–51. 10.1007/s00198-014-2703-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Di Gregorio S, Del Rio L, Rodriguez-Tolra J, et al. . Comparison between different bone treatments on areal bone mineral density (aBMD) and bone microarchitectural texture as assessed by the trabecular bone score (tbs). Bone 2015;75:138–43. 10.1016/j.bone.2014.12.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Saag KG, Agnusdei D, Hans D, et al. . Trabecular bone score in patients with chronic glucocorticoid therapy-induced osteoporosis treated with alendronate or teriparatide. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2122–8. 10.1002/art.39726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Russo CR. The effects of exercise on bone. basic concepts and implications for the prevention of fractures. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 2009;6:223–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Jain RK, Vokes T. Physical activity as measured by accelerometer in NHANES 2005–2006 is associated with better bone density and trabecular bone score in older adults. Arch Osteoporos 2019;14:29 10.1007/s11657-019-0583-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors Recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing, and publication of scholarly work in medical journals 2017. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027429supp001.pdf (162.4KB, pdf)