Abstract

Objective

The aim of the study was to assess the relationship between body mass index (BMI) and the incidence of abnormalities in selected parameters measured in the trunk area.

Design

Cross-sectional studies.

Setting

The research was conducted in a primary school in the Trzebownisko Municipality, a rural area in south-eastern Poland.

Participants

A group of 464 children, ranging in age from 6 to 16 years (234 boys and 230 girls), was recruited to participate in the study.

Outcome measures

The examination of their body postures was conducted with the use of the Zebris system. Body mass was determined using a body mass analyser Tanita MC-780 MA. BMI was calculated based on the acquired data.

Results

It was noticed that the children with overweight and obesity tended to have an incorrect position of the shoulders and pelvis in comparison to children with normal body weight. It was found that greater body mass (higher BMI) coincided with a larger distance of the scapulae from the frontal plane (p=0.009).

Conclusions

Increase in children’s BMI produces adverse effects in the position of the shoulder blades, reflected by their greater distance from the frontal plane. Increase in BMI is not significantly related to the position of the shoulder joints or pelvis; however, the subjects with overweight or obesity presented a greater difference in the position of the shoulder joints and pelvis.

Keywords: posture, body mass index, child, rural population

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The homogeneity and large size of the study group from rural areas.

Objective and standardised measuring devices.

We cannot entirely rule out the possibility of unmeasured or unknown confounding factors (parental genetic predisposition to higher body mass index) that may account for the associations observed in this study. However, the homogeneity of the study population and comprehensive data on the risk factors minimised potential confounding effects.

Other elements that can affect trunk muscle tension include muscular problems, for example, neonatal hypertonia or hypotonia and their consequences in childhood, as well as past injuries and chronic neurological diseases, and these should be taken into account in future studies.

Introduction

A child’s correct body posture favourably affects the growth of their whole body.1 It contributes for instance to the normal development and functioning of body organs, and improves the effectiveness of motor activity and general well-being.2 If they are developed early in life, correct motor habits contribute to normal development of the muscles, joints and ligaments and provide beneficial stimulation to the child’s growing skeleton. Even the smallest defects in the body posture of a school-age child can lead to the development of a habitual bad posture and, consequently, to health problems.3 4

Body postures are subject to large changeability, which depends on factors such as age, sex, somatic type, ethnicity, environment and psychophysical condition. The major risk factors that may induce the development of incorrect body posture include excessive body mass in relation to height and age.5 6 A vast majority of overweight or obese children live in developed countries with growth rates over 30% higher compared with the developing countries. If the current trends continue, the number of overweight or obese infants worldwide will increase to 70 million in 2025.7 Overweight and obesity in children, often associated with insufficient physical activity, lead to decreased use of the motor system; at the same time the increasing fat deposition contributes to overloading of the skeletal system, and this is a precondition for the development of postural defects.8 Children with body mass above the 95th percentile (body mass index (BMI) z-score>+2 SD) far more often present postural defects involving the spine, thoracic cage, as well as lower limbs, and suffer from musculoskeletal pain.9

Maciałczyk-Paprocka et al report that postural deficits may affect as many as 74.1% of boys and 85.5% of girls with excessive body mass, and the predominant problems include knock knees and fallen arches.10 Also, in the last decades there has been an unprecedented increase in the number of obese children, and the problem is associated with a number of functional disorders, for example, pain, joint stiffness and reduced muscle strength, which contribute to the development of poor posture. General rates of obesity among children worldwide are estimated at the level of 10% and, like in the case of postural deficits, the problem is constantly growing. The top of the ranking is dominated by the North American countries including USA, where the level of overweight and obesity reaches the unprecedented rates of almost 32%. In Western Europe the rates reach up to 20%, whereas in Central and Eastern Europe they reach the level of 16%.11 12

According to numerous clinical data, a child’s body posture is particularly at risk during the periods of the fastest pace of growth, which mainly include the time corresponding to the start of school education (6–7 years of life) and the puberty period (12–16 years of life). In view of the above, research focusing on body posture in school-age children, taking into account body mass, is of particular importance.12–14

According to the data reported in the literature, the rate of overweight and obesity in children is consistently increasing.15 A similar situation is observed in the case of postural defects.16 In previously conducted studies numerous authors have investigated factors affecting obesity or postural defects, though usually focusing on these problems separately.15 17 18 There are no studies that link these two aspects to each other. Additionally, the majority of the reports are related to children from urban areas, more affected by globalisation, and those from highly developed countries where children more commonly present musculoskeletal disorders related to incorrect body posture.19–21 On the other hand, it would be worthwhile to carry out related research focusing on rural areas where children grow up in more natural environments, have more opportunities for outdoor activity, and better access to healthy food, yet they are also frequently affected by the two problems.22 23 Overweight and obesity occur much more often among children and teenagers from rural areas, compared with towns and cities, mostly from multi-child families of low economic status, where the education level of the parents is quite low. The problem mainly affects the population of developmental age, and so the scale of the phenomenon is a matter of concern.24 There is also a scarcity of studies examining body posture with objective measurement methods, such as the Zebris APGMS Pointer, which performs detailed assessment of static body posture, range of motion and the shape of spinal curves.10

The aim of the study was to assess the relationship between BMI and abnormalities in the trunk area, that is, scapula distance difference (SDD), pelvic height difference (PHD) and shoulder height difference (SHD) in children living in rural communities.

Material and methods

The participants were informed about the course of the study. The examinations were conducted after written consent was received from the headmasters of the schools, parents of the children participating in the project and the children themselves.

Participants

First, the sample size was calculated with reference to the total number of children (n=3790) living in the Trzebownisko Municipality, a rural area in south-eastern Poland, with a 95% confidence level and a CI of 0.05. It was calculated that the minimum sample size should be 349. The study took into account 464 school-age children, from 6 to 16 years of age (234 boys and 230 girls). They were qualified for the study (from June 2016 to March 2018), designed to be conducted in schools in a rural region. Five primary and secondary schools were randomly selected out of the nine schools located in the specific rural region in the south-eastern area of the country in which the study was conducted. Examinations were conducted in nurses’ offices in the relevant educational facilities. In order to ensure the reliability of the measurements, all the subjects were examined in the morning, on an empty stomach, by the same members of a qualified team.

The study applied the following inclusion criteria: age from 6 to 16 years and consent of the parents and children for the examination. Exclusion criteria: metal implants, electronic implants, periods in girls, epilepsy and failure to refrain from eating in the morning on the day of the study. Children with a diagnosis of neonatal hypertonia or hypotonia, chronic neurological diseases or past injuries and surgical interventions during the last 6 months before examination were excluded from the study group.

Body posture

The study of body posture was conducted with the use of the Zebris APGMS Pointer system. An examination is carried out with an ultrasound pointer used to mark characteristic anatomical locations corresponding to specific bone structures on the patient’s body. These locations are treated by the software as passive points. Their position and movement are tracked and recorded in real time by the software. The study was carried out in static conditions, in a motionless standing position.

The reference markers were three miniature transmitters attached to the patient with flexible straps. These define points with reference to which the device specifies the positions of pointer markers. By applying the pointer to the characteristic anatomical locations on the body and by activating the device it is possible to visualise the relevant points on the screen and to create a three-dimensional image of the body posture.25 26

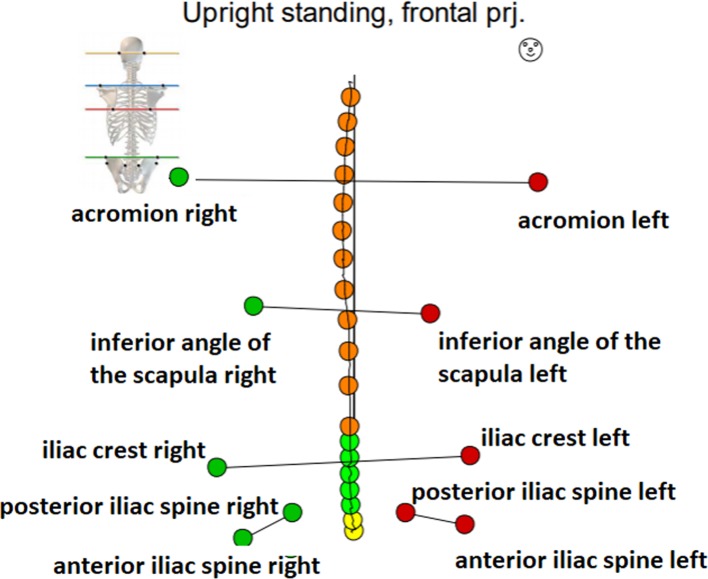

At the start, topographic points were marked on the body of each subject to correspond with: acromion right and left, posterior iliac spine right and left, anterior iliac spine right and left, iliac crest right and left, the point where the thoracic spine meets the lumbar spine, Th 12/L1, inferior angle of the scapula right and left, spinous process of the spine. A sample result of the examination as well as the defined topographic points are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Topographic points marked on the body of patients.

Based on the defined topographic points, the software computes the values of selected body posture parameters. The following were taken into account in the assessment of posture:

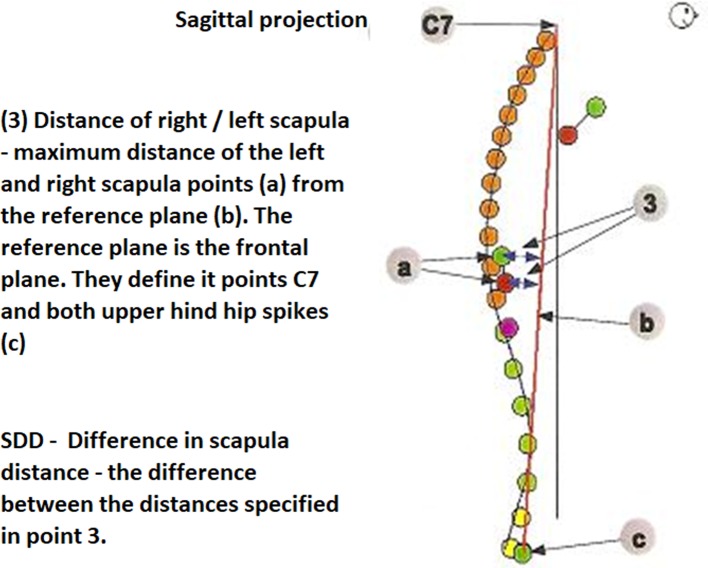

In the sagittal projection: SDD (in mm) (figure 2).

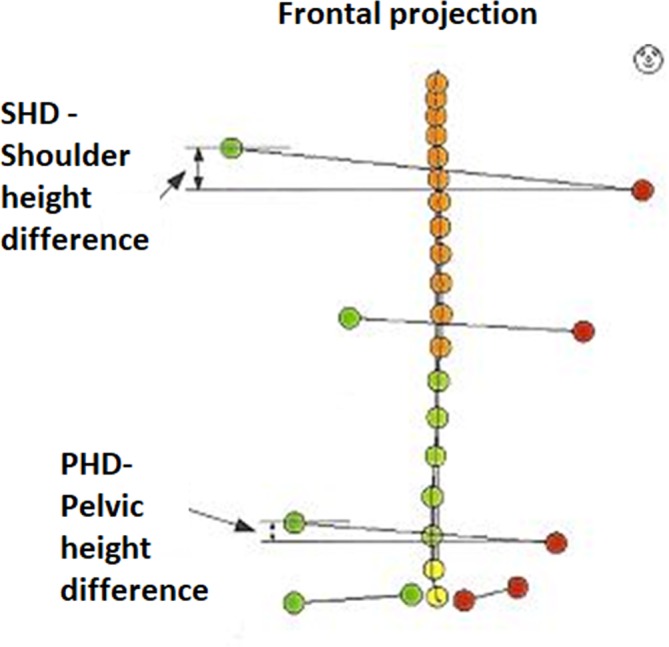

In the frontal projection: PHD (in mm) and SHD (in mm) (figure 3).

Figure 2.

The difference in the distance of the scapula in the sagittal projection.

Figure 3.

Pelvic height difference and shoulder height difference in the frontal projection.

During the examination the subject, wearing no shoes, was asked to assume a relaxed standing position, with his/her back to the measurement unit, and did not have with him/her any devices interfering with the transfer of data (eg, smartwatch, mobile phone).

Following calibration of the horizontal plane, the subject’s body posture was examined. The measurement, performed with an ultrasound pointer, involved registration of the topographic points marked earlier on the subject’s body. The measurements were performed three times in each subject and the spine line was scanned nine times (three times in each examination). The final result was the mean value of the measurements.27

Anthropometric measurements and bioelectrical impedance

Body height was measured with an accuracy up to 0.1 cm, with the use of a portable stadiometer PORTSTAND 210. Body mass was measured with the Tanita MC-780 MA analyser with an accuracy up to 0.1 kg. The examinations were conducted in standard conditions. During the measurement, each subject was barefoot and dressed in underwear, and was asked to assume an upright extended position.

The data acquired during the measurement of body height and mass were used to calculate the BMI. The BMI value was examined by reference to the growth chart, taking into account sex and age. Based on the achieved percentile ranking, the BMI status was classified in the following four categories: obesity (BMI ≥95th percentile), overweight (BMI ≥85th percentile and <95th percentile), normal body mass (BMI <85th percentile and ≥5th percentile) and underweight (BMI <5th percentile).28

Data analysis

Spearman’s rank correlation test was applied to assess the correlation between BMI and body posture. Differences in the selected parameters between the groups were analysed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The accepted level of significance was α<0.05. All calculations and statistical analyses were performed with the use of STATISTICA V.10.0 (StatSoft, Poland).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design of the study. The parents of the children who participated in the study received the results of the measurements and recommendations about treatment opportunities.

Results

The characteristics of the study group are shown in tables 1 and 2. On average the subjects were 11.52 years old (SD=2.99). The mean body height was 152.48 cm (SD=17.77) and the mean body mass was 45.39 kg (SD=16.81). On average the subjects’ BMI was 18.8 kg/m2 (SD=3.75) (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study group

| N | Mean | Me | SD | Q1 | Q3 | |

| All | ||||||

| Age (years) | 464 | 11.52 | 12.00 | 2.99 | 9.00 | 14.00 |

| Height (cm) | 464 | 152.48 | 155.50 | 17.77 | 137.00 | 167.00 |

| Weight (kg) | 464 | 45.39 | 44.75 | 16.81 | 30.40 | 56.45 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 464 | 18.80 | 18.24 | 3.75 | 16.10 | 20.97 |

| Girls | ||||||

| Age (years) | 230 | 11.55 | 12 | 2.96 | 9.00 | 14.00 |

| Height (cm) | 230 | 150.46 | 155 | 15.69 | 136.00 | 163.00 |

| Weight (kg) | 230 | 43.63 | 44.35 | 15.38 | 29.70 | 54.60 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 230 | 18.64 | 18.00 | 3.87 | 15.90 | 20.90 |

| Boys | ||||||

| Age (years) | 234 | 11.49 | 12 | 3.02 | 9.00 | 14.00 |

| Height (cm) | 234 | 154.46 | 156.50 | 19.43 | 138.00 | 172.00 |

| Weight (kg) | 234 | 47.13 | 45 | 17.97 | 31.80 | 60.00 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 234 | 18.94 | 18.56 | 3.63 | 16.40 | 21.05 |

Me: median; n: number of subjects; Q1: first quartile;Q3: third quartile SD.

Table 2.

The body mass category based on BMI depending on the sex

| BMI category | Sex | |||||

| Boys | Girls | Total | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Underweight | 16 | 6.8 | 17 | 7.4 | 33 | 7.1 |

| Normal body mass | 170 | 72.7 | 172 | 74.8 | 342 | 73.7 |

| Overweight | 27 | 11.5 | 28 | 12.2 | 55 | 11.9 |

| Obesity | 21 | 9.0 | 13 | 5.6 | 34 | 7.3 |

| Total | 234 | 100.0 | 230 | 100.0 | 464 | 100.0 |

| Significance (p) | χ²(3)=1.90; p=0.591 | |||||

%: per cent of subjects; N: number of subjects; p: test probability value; χ2: chi-square Pearson test.

BMI, body mass index.

Based on the BMI percentiles a categorisation of the body mass of the study group was performed. 6.8% of the boys and 7.4% of the girls were found to be underweight. Normal body mass was identified in 72.7% of the boys and 74.8% of the girls. 11.5% of the boys and 12.2% of the girls were found to be overweight, and obesity was identified in 9% of the boys and in 5.7% of the girls (table 2).

Analyses of the correlations between BMI and the body posture parameters measured in the trunk area showed statistically significant differences in the case of the distance of the scapulae from the corresponding plane. Statistical significance was not observed in the relationship of the position of the pelvis (H=5.33; p=0.150) and the BMI. It was found that greater body mass (higher BMI) coincided with a larger distance of the scapulae from the frontal plane (H=11.47; p=0.009). It was noticed that people with overweight and obesity have incorrect position of the shoulders and pelvis in comparison to people with normal body weight (table 3).

Table 3.

The correction between the body mass category, based on BMI and the body posture

| Scapula distance difference (mm) | ||||||||

| BMI category | N | Mean (95% Cl) | SD | Me | Min. | Max. | Q1 | Q3 |

| Underweight | 33 | 4.58 (3.13 to 6.02) |

6.07 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 18.00 | 2.00 | 6.00 |

| Normal body mass | 342 | 6.90 (6.27 to 7.53) |

6.13 | 5.50 | 0.00 | 32.00 | 2.00 | 9.00 |

| Overweight | 55 | 8.04 (6.34 to 9.73) |

6.16 | 6.00 | 0.00 | 28.00 | 4.00 | 10.00 |

| Obesity | 34 | 9.50 (6.44 to 12.56) |

6.10 | 7.00 | 0.00 | 41.00 | 4.00 | 10.00 |

| H=11.47; p=0.009 | ||||||||

| Shoulder height difference (mm) | ||||||||

| BMI category | N | Mean (95% Cl) |

SD | Me | Min. | Max. | Q1 | Q3 |

| Underweight | 33 | 6.96 (4.98 to 8.93) |

6.90 | 5.50 | 0.10 | 19.60 | 2.10 | 10.80 |

| Normal body mass | 342 | 10.00 (9.16 to 10.84) |

6.72 | 8.00 | 0.10 | 59.80 | 4.10 | 14.60 |

| Overweight | 55 | 10.66 (8.33 to 12.99) |

8.45 | 7.40 | 0.50 | 32.80 | 3.70 | 16.50 |

| Obesity | 34 | 11.04 (7.99 to 14.09) |

7.74 | 9.35 | 0.50 | 39.90 | 5.20 | 15.10 |

| H=5.43; p=0.143 | ||||||||

| Pelvis height difference (mm) | ||||||||

| BMI category | N | Mean (95% Cl) |

SD | Me | Min. | Max. | Q1 | Q3 |

| Underweight | 33 | 9.27 (6.83 to 11.72) |

5.57 | 7.70 | 0.10 | 23.20 | 3.60 | 12.50 |

| Normal body mass | 342 | 7.97 (7.25 to 8.68) |

7.90 | 6.30 | 0.00 | 35.60 | 2.60 | 11.10 |

| Overweight | 55 | 9.96 (7.67 to 12.24) |

8.62 | 7.40 | 0.10 | 37.40 | 4.50 | 14.70 |

| Obesity | 34 | 10.07 (7.37 to 12.77) |

8.74 | 7.50 | 0.20 | 28.80 | 4.70 | 15.90 |

| H=5,33 p=0,150 | ||||||||

H: Kruskall-Wallis test; Max.: maximum value; Me: median; Min.: minimum value; N: number of subjects; p: test probability value; Q1: quartile 25; Q3: quartile 75.

BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

The start of school education marks a period when a child’s posture is very sensitive to changes due to the new co-occurring environmental factors. The adverse risk factors include mainly the long periods when the child remains seated in class and during other school-related activities, wearing a heavy schoolbag, asymmetry of schoolbag straps, or asymmetric position of a schoolbag worn by the child, as well as more frequently occurring fatigue and stressful experiences at school. All of these may promote different postural habits involving more pronounced thoracic kyphosis and downward head positioning.29 30 As a result, natural physical activity is restricted to a degree, and children tend to spend their free time in a passive way, in front of a computer or TV. This situation produces adverse effects because a sedentary lifestyle not only increases the risk of excessive body mass in the children but also contributes to the development of postural deficits.

The time when a child attends school may produce beneficial effects as it is likely to foster development of habits related to physical activity and sport, which are of extreme importance for ensuring the child’s normal physical development.31 32 It is important to enable early diagnosis, since body posture in adults to a large degree is a result of the early stages of development.33 34 It should be emphasised that early and non-invasive body posture studies among school-age children, with the use of the external diagnostic systems, are crucially important.

The current study enabled the assessment of body posture parameters in relation to the BMI category identified in children attending primary and middle schools. In the study group 6.8% of the boys and 7.4% of the girls were identified as being underweight. Normal body mass was found in 72.7% of the boys and 74.8% of the girls. 11.5% of the boys and 12.2% of the girls were identified as being overweight. Obesity was found in 9% of the boys and in 5.7% of the girls. These values are similar to the data published by the WHO, according to which in 2016 overweight and obesity were found in 18% of children and adolescents between 5 and 19 years of age.35

The current study shows a strong correlation between the BMI and the body posture parameters. Also, a correlation was found between the height of the left shoulder and excessive weight. Children with higher BMI were far more often found to have a decreased distance between the scapula and the frontal plane.

A study by Batistão et al, involving 288 school-age children, reported asymmetry in the position of shoulders in 74.3% of the subjects; the problem was particularly pronounced among older children, aged 13–15 years, which supports the claim that this type of deficit may be associated with the rapid growth of specific segments of the body occurring during puberty. In fact, the problem appears to be more closely related to age than to body mass. These asymmetries in the position of the shoulders may also be explained by the varied overloads of the body linked with environmental factors, for example, asymmetrical body posture in sitting position and carrying of schoolbags on one side, a habit frequently observed in teenagers.36 As shown by the present study, incorrect body mass may also be a contributing factor, producing similar effects.

Many authors have discussed the relation of body posture and BMI. An important problem was pointed out by Pausić et al as well as Barszczyk et al who claim that both excessively low and excessively high body mass lead to negative changes in the position of the spine, lower extremities and feet.37 38 Partly similar results were reported by Walicka-Cupryś et al. These authors examined children with genu valgum and found that the defect was most common in overweight children (28.6%), followed by children with normal weight (14.7%), and it was least frequent in underweight subjects (10.7 %).25

Bogucka and Glebocka in their study examined the body posture of 227 school-age children. The authors observed that in the subgroup of underweight girls, the protruding scapulae were present significantly more often than in their peers with normal weight and height. However, underweight boys more frequently than their peers with normal BMI were characterised by asymmetry of the scapulae towards the spine. It was suggested that faulty body postures in the scapulae area occurred more frequently in underweight subjects (r=0.359; p<0.001).39

Likewise, Grivas et al reported that excessively low BMI is more frequently associated with body asymmetry in teenagers.40 Similar conclusions can be drawn from the study by Grabara and Pstrągowska41 The present study identified the opposite tendency. Children with greater body mass (overweight and obesity) were found to have a larger distance between the scapulae and the frontal plane (H=11.47; p=0.009). However, all the above findings suggest that height-related and weight-related abnormalities are closely linked with postural defects during developmental age.

People with overweight and obesity show higher abnormalities in the position of the shoulders and pelvis than people with normal weight. Age-related analysis of the study group showed a negative correlation between the subjects’ age and oblique position of the pelvis (r=0.09; p=0.049). Similarly, Rosa et al reported low rates of incorrect pelvis position in grades I–III children. No related abnormalities were identified in 68% of the girls and 72% of the boys.42 Different findings were reported by Słoń, who performed similar measurements in a group of 162 primary school students (grades IV–VI) in Warsaw. The author observed incorrect position of the pelvis in 77% of the subjects.43

The current study enabled the assessment of BMI in relation to the incidence of abnormalities in selected parameters measured in the trunk area. In the literature we can find data related to the growing number of children and teenagers with excessive body weight, as well as more and more evidence proving the adverse health related effects of overweight and obesity. Excessive body weight to a large extent contributes to postural defects, and adversely affects health condition, as well as body water and electrolyte balance. That is why it was justifiable to specify the body mass category based on BMI and to investigate its influence on body posture in school-age children. In view of the fact that obesity is more and more common among children, schools should provide instruction on healthy diet and encourage students to take up physical activity.

The results of the examinations made it possible to increase awareness among parents and primary school teachers related to the important role of body weight in a child’s development, including the effects of this factor in body posture. Following the study, the headmasters of the relevant schools initiated cooperation with a Rehabilitation Centre offering specialist consultations and optional corrective exercise programmes for children with postural defects. Overweight and obesity among children and adolescents should be prevented by introducing educational programmes for whole families and showing them the negative impact of obesity on body posture.

Conclusions

Increase in children’s BMI produces adverse effects in the position of the shoulder blades, reflected by their greater distance from the frontal plane. Increase in BMI is not significantly related to the position of the shoulder joints or pelvis; however, the subjects with overweight or obesity presented a greater difference in the position of the shoulder joints and pelvis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participants and their families who volunteered their time to participate in this research.

Footnotes

Contributors: WR: conception and design, revising critically for intellectual content, final approval of the manuscript; JL: acquisition of data, drafting the article, final approval of the manuscript; JB: acquisition of data, revising critically for intellectual content, final approval of the manuscript; MA: analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, final approval of the manuscript; AW: analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, final approval of the manuscript; RB: acquisition of data, drafting the article, final approval of the manuscript; GI: acquisition of data, revising critically for intellectual content, final approval of the manuscript; EC-L: acquisition of data, revising critically for intellectual content, final approval of the manuscript; SP: acquisition of data, drafting the article, final approval of the manuscript and TP: conception and design, revising critically for intellectual content, final approval of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was accepted by the local Bioethical Commission on 28 June 2016 (consent no. 2016/06/28).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Ferguson KT, Cassells RC, MacAllister JW, et al. The physical environment and child development: an international review. Int J Psychol 2013;48:437–68. 10.1080/00207594.2013.804190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McEvoy MP, Grimmer K. Reliability of upright posture measurements in primary school children. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2005;6:35 10.1186/1471-2474-6-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mrozkowiak M, Walicka-Cupryś K, Magoń G. Comparison of spinal curvatures in the sagittal plane, as well as body height and mass in Polish children and adolescents examined in the late 1950s and in the early 2000s. Med Sci Monit 2018;24:4489–500. 10.12659/MSM.907134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Araújo FA, Lucas R, Simpkin AJ, et al. Associations of anthropometry since birth with sagittal posture at age 7 in a prospective birth cohort: the generation XXI study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013412 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kowalski IM, Protasiewicz-Fałdowska H, Siwik P, et al. Analysis of the sagittal plane in standing and sitting position in girls with left lumbar idiopathic scoliosis. Polish Annals of Medicine 2013;20:30–4. 10.1016/j.poamed.2013.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Komro KA, Tobler AL, Delisle AL, et al. Beyond the clinic: improving child health through evidence-based community development. BMC Pediatr 2013;13 10.1186/1471-2431-13-172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. WHO: Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity. "Facts and figures on childhood obesity", 2017. Available: https://www.who.int/end-childhood-obesity/facts/en/ [Accessed 14 Jun 2019].

- 8. Barańska E, Gajewska E, Sobieska M. Obesity and the resulting motor organ problems versus motoric fitness in girls and boys with overweight and obesity. Medical News 2012;4:337–41. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith SM, Sumar B, Dixon KA. Musculoskeletal pain in overweight and obese children. Int J Obes 2014;38:11–15. 10.1038/ijo.2013.187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maciałczyk-Paprocka K, Stawińska-Witoszyńska B, Kotwicki T, et al. Prevalence of incorrect body posture in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity. Eur J Pediatr 2017;176:563–72. 10.1007/s00431-017-2873-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. 10 facts on obesity, world Health organization, 2018. Available: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/obesity/en/ [Accessed 2 May 2018].

- 12. Hruby A, Hu FB. The epidemiology of obesity: a big picture. Pharmacoeconomics 2015;33:673–89. 10.1007/s40273-014-0243-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mazur A. The epidemiology of childhood overweight and obesity on the world, in Europe and in Poland. Prz. Med. Uniw. Rzesz. Inst. Leków 2011;2:158–63. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Villarrasa-Sapiña I, Álvarez-Pitti J, Cabeza-Ruiz R, et al. Relationship between body composition and postural control in prepubertal overweight/obese children: a cross-sectional study. Clinical Biomechanics 2018;52:1–6. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2017.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017;390:2627–42. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Drzał-Grabiec J, Snela S, Truszczyńska A. The development of anterior-posterior spinal curvature in children aged 7–12 years. Biomed Hum Kinet 2016;8:72–82. 10.1515/bhk-2016-0011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Latalski M, Bylina J, Fatyga M, et al. Risk factors of postural defects in children at school age. Ann Agric Environ Med 2013;20:583–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dereń K, Nyankovskyy S, Nyankovska O, et al. The prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity in children and adolescents from Ukraine. Sci Rep 2018;8:3625 10.1038/s41598-018-21773-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Paranjape S, Ingole V. Prevalence of back pain in secondary school students in an urban population: cross-sectional study. Cureus 2018;10 10.7759/cureus.2983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maciałczyk-Paprocka K, Dudzińska J, Stawińska-Witoszyńska B, et al. Incidence of scoliotic posture in school screening of urban children and adolescents: the case of Poznań, Poland. Anthropol Rev 2018;81:341–50. 10.2478/anre-2018-0030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Akbar F, AlBesharah M, Al-Baghli J, et al. Prevalence of low back pain among adolescents in relation to the weight of school bags. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019;20:37 https://doi.org/ 10.1186/s12891-019-2398-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dudonienė V, Šakalienė R, Švedienė L, et al. Differences of age and gender related posture in urban and rural schoolchildren aged 7 to 10. BJSHS 2013;1:25–31. 10.33607/bjshs.v1i88.142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Drzał-Grabiec J, Snela S. The influence of rural environment on body posture. Ann Agric Environ Med 2012;19:846–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wyszyńska J, Podgórska-Bednarz J, Drzał-Grabiec J, et al. Analysis of relationship between the body mass composition and physical activity with body posture in children. BioMed Res Int 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Walicka-Cupryś K, Skalska-Izdebska R, Drzał-Grabiec J, et al. Correlation between body posture and postural stability of school children. Advances in Rehabilitation 2013;27:47–54 https://doi.org/ 10.2478/rehab-2014-0026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Illyés A, Kiss RM. Method for determining the spatial position of the shoulder with ultrasound-based motion analyzer. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2006;16:79–88. 10.1016/j.jelekin.2005.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rusek W, Pop T, Glista J, et al. Assessment of student’s body posture with the use of Zebris system. Prz Med Uniw Rzesz Inst Leków 2010;3:277–88. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barlow SE, Expert Committee . Expert Committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics 2007;120 Suppl 4:S164–92. 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Walicka-Cupryś K, Piwoński P, Rachwał M, et al. Shape of sagittal plane spinal curvatures in prematurely born children at the start of school education. J Novel Physiotherapies 2017;5. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brzęk A, Dworrak T, Strauss M, et al. The weight of pupils' schoolbags in early school age and its influence on body posture. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2017;18:117 10.1186/s12891-017-1462-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Villarrasa-Sapiña I, García-Massó X, Serra-Añó P, et al. Differences in intermittent postural control between normal-weight and obese children. Gait Posture 2016;49:1–6. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Maciałczyk-Paprocka M, Krzyżaniak A, Kotwicki T, et al. Postural defects in primary school students in Poznan. Probl Hig Epidemiol 2012;2:309–14. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kapo S, Rađo I, Smajlović N, et al. Increasing postural deformity trends and body mass index analysis in school-age children. Zdravstveno varstvo 2018;1:25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Walicka-Cupryś K, Skalska-Izdebska R, Rachwał M, et al. Influence of the weight of a school backpack on spinal curvature in the sagittal plane of seven-year-old children. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:1–6. 10.1155/2015/817913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Global health Observatory (GHO) data. Available: www.who.int [Accessed 7 Aug 2018].

- 36. Batistão MV, de Fátima Carreira Moreira R, Cote Gil Coury HJ. Prevalence of postural deviations and associated factors in children and adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Fisioter mov 2016;4:778–85. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barczyk K, Skolimowski T, Anwajler J, et al. Somatic features and parameters of anterior-posterior spinal curvature in 7-year-olds with particular posture types. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil 2005;7:555–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pausić J, Cavala M, Katić R. Relations of the morphological characteristic latent structure and body posture indicators in children ages seven to nine years. Coll Antropol 2006;3:621–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bogucka A, Głębocka A. Body posture of children aged 9 –12 years as related to their body mass index (BMI). Physical Activity and Health 2017;12:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grivas TB, Burwell RG, Mihas C, et al. Relatively lower body mass index is associated with an excess of severe truncal asymmetry in healthy adolescents: do white adipose tissue, leptin, hypothalamus and sympathetic nervous system influence truncal growth asymmetry? Scoliosis 2009;4 10.1186/1748-7161-4-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grabara M, Pstrągowska D. Estimation of the body posture in girls and boys related to their body mass index (BMI). Med Sport 2008;4:231–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rosa K, Muszkieta R, Zukow W, et al. The incidence of defects posture in children from classes I to III elementary school. J Health Sci 2013;3:107–36. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Słoń A. The incidence of selected postural disorders in children aged 10 –12 years. WSKFiT 2015;10:49–55. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.