Abstract

Objective

Obstruction release from urolithiasis can be delayed with a lack of suggested time for preventing the deterioration of renal function. The objective of this study was to investigate the effect of obstruction duration, concomitant acute kidney injury (AKI) or acute pyelonephritis (APN) during the obstruction on the prognosis of renal function.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting and participants

1607 patients from a urolithiasis-related obstructive uropathy cohort, between January 2005 and December 2015.

Outcome measures

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decrease ≥30% and/or end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and eGFR decrease ≥50% and/or ESRD, according to obstruction duration, AKI and APN accompanied by obstructive uropathy.

Results

When the prognosis was divided by obstruction duration quartile, the longer the obstruction duration the higher the probability of eGFR reduction >50% (p=0.02). In patients with concomitant APN or severe AKI during hospitalisation with obstructive uropathy, an eGFR decrease of >30% and >50% occurred more frequently, compared with others (p<0.001). When we adjusted for sex, age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, APN, AKI grades and obstruction release >7 days for multivariate analysis, we found that concomitant APN (HR 3.495, 95% CI 1.942 to 6.289, p<0.001), concomitant AKI (HR 3.284, 95% CI 1.354 to 7.965, p=0.009 for AKI stage II; HR 6.425, 95% CI 2.599 to 15.881, p<0.001 for AKI stage III) and an obstruction duration >7 days (HR 1.854, 95% CI 1.095 to 3.140, p=0.001) were independently associated with an eGFR decrease >50%. Tree analysis also showed that AKI grade 3, APN and an obstruction duration >7 days were the most important factors affecting renal outcome.

Conclusions

In patients with urolithiasis-related obstructive uropathy, concomitant APN was strongly associated with deterioration of renal function after obstruction release. The elapsed time to release the obstruction also affected renal function.

Keywords: acute pyelonephritis, chronic renal failure, acute renal failure, nephrolithiasis, urolithiasis, obstructive uropathy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

In this study, considering the difficulties in performing a randomised controlled trial, it is possible to consider that lowering the incidence of acute kidney injury or acute pyelonephritis through early obstruction release may have an additional benefit in improving prognosis, especially in patients with recurrent urolithiasis.

There is a possibility that the symptom occurrence date was not an obstruction-specific date, and as the evidence was required for the spontaneous resolution of obstruction release, the document date may be later than the actual obstruction release date.

The results cannot prove a causal relationship, and the retrospective aspect of this study may introduce selection bias and misclassification.

Introduction

Urolithiasis-related obstructive uropathy is increasingly becoming one of the leading causes of chronic kidney disease (CKD), which is commonly encountered in the clinical field.1 2 It occurs worldwide, but the incidence and prevalence can vary widely from country to country.2–7 The differences are generally known to be affected by sex, age, regional characteristics (diet habit and environment), race, amount of water intake, obesity and other comorbidities.8–10

Urolithiasis causes various discomforting symptoms, such as severe pain, haematuria or lower urinary tract symptoms, which worsen quality of life. In addition, it is associated with socioeconomic losses in various aspects as it often requires invasive treatment, such as intervention or surgery to remove stones, leading to hospitalisation of an economically active age population. Patients with urolithiasis commonly experience recurrent episodes of ureteral obstruction, or concomitant metabolic disorders such as hyperuricaemia, diabetes mellitus (DM) or dyslipidaemia.11 Also, if obstructive uropathy by urolithiasis causes additional complications such as acute kidney injury (AKI) or infection, and postobstructive diuresis, socioeconomic burden is further increased due to longer hospital stay and CKD progression.12–16 The incidence of acute renal injury due to renal stones has been reported to be 0.72%–9.7%. Stone removal improves occlusion and restores renal function.17 Therefore, early obstruction release is thought to have an important effect on prognosis, by preventing infections and renal dysfunction. However, obstruction release from urolithiasis can be easily delayed for various reasons in clinical practice with the lack of suggested best time for preventing the deterioration of renal function.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of obstruction duration itself, due to urolithiasis, and the effect of concomitant AKI or acute pyelonephritis (APN) during the obstruction on the prognosis of renal function.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

A total of 2314 patients with urolithiasis were screened and admitted to Chung-Ang University Hospital (online supplementary table S1) from January 2005 to December 2015. Of these patients, 1607 were eligible for analysis, excluding 707: no evidence of obstructive uropathy (259), obstruction onset date unknown (187), obstruction release date unknown (the date the symptom was relieved is not specified in spontaneous release or there is no image evidence) (175), staghorn stone (55), paediatric patients (12), obstructive uropathy due to other causes besides a renal stone (11), and loss of follow-up after discharge (8). All included patients were at least 15 years of age, were admitted to the hospital because of obstructive uropathy due to urolithiasis and were able to estimate the date of occurrence of the obstruction as the symptom date was recorded. Basic clinical parameters were collected, such as age at the time of admission, sex, underlying comorbidities (hypertension (HT), DM and alleged CKD), information on laboratory findings (at the time of admission, peak C reactive protein (CRP), highest serum creatinine (SCr) and lowest estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)), information about urolithiasis (performed radiological modality for diagnosis, obstruction site, obstruction side, selected procedure to release obstructive uropathy, stone size and grade of hydronephrosis), use of pain killers and outcome profiles (follow-up eGFR).

bmjopen-2019-030438supp001.pdf (48.4KB, pdf)

Measurement and definition of parameters

Obstruction duration was calculated as the difference between the documented symptom onset date and the date on which the obstruction was directly resolved by procedure, or from the date on which the pain was markedly improved in the spontaneous release patients.

Concomitant APN was defined as the presence of APN diagnosis in the medical records or use of antibiotics for urinary tract infection treatment for more than 7 days in patients with CRP >10 mg/L.

All SCr and eGFR data were collected before, during and after admission to confirm baseline renal function and AKI during hospitalisation. AKI was defined by SCr change as described in the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes clinical practice guideline18: AKI was diagnosed when there was an abrupt reduction in kidney function, with an absolute increase in SCr level by ≥0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours and/or an increase of more than 1.5-fold from the baseline SCr level within 7 days. Then, AKI stages were further evaluated as follows: AKI stage I, an increase in SCr 1.5–1.9 times from baseline or by ≥0.3 mg/dL; AKI stage II, an increase in SCr of 2.0–2.9 times from baseline; and AKI stage III, an increase in SCr more than 3.0 times from baseline, ≥4.0 mg/dL, or initiation of renal replacement therapy. Urine output criteria were not considered due to the inaccuracy of the data, which should be collected retrospectively.

The size of the renal stone causing the occlusion was measured, with the longest diameter as the most accurate image for each patient. Hydronephrosis was divided into four grades (I–IV), with reference to existing literature19: grade I, dilation of the renal pelvis without dilatation of the calyces; grade II, dilation of the renal pelvis and calices, which become convex, and no signs of cortical thinning; grade III, the presence of cortical thinning; and grade IV, massive dilation of the renal pelvis and calices, with severe cortical thinning.

Primary and secondary objectives

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate whether the duration of urinary tract obstruction affects renal outcome. The secondary objective was to evaluate whether AKI, APN or both events affect renal outcome. Renal outcomes were evaluated with an eGFR decrease ≥30% and/or end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and an eGFR decrease ≥50% and/or ESRD. Each renal outcome was collected from an event that occurred 3 months after discharge from obstructive uropathy.

Statistical analysis

Analyses and calculations in this study were performed using SPSS Statistics V.20.0 and R V.3.4.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Continuous variables did not satisfy normality tests, so non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U test) were performed and median (minimum–maximum) was provided. For categorical variables, data were expressed as number (percentage) and compared using the χ2 test. Renal outcome-free survival rates were also performed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and comparison between groups was performed using the log-rank test. Building tree-based regression and classification models (decision and survival tree analyses) were performed by recursive partitioning using party package. Input variables were age, sex, APN, AKI stages and obstruction duration-based groups.

The Cox proportional hazard model was used to identify independent risk factors for renal outcome and to calculate the HR and 95% CI. Statistical significance was set at the level of p<0.05.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design of this analysis.

Results

Baseline data by obstruction duration

From January 2005 to December 2015, a total of 2314 patients with urinary tract stone disease were identified, and a total of 1607 patients were confirmed suitable for analysis. The baseline characteristics of 1607 enrolled patients are described in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics according to obstruction duration

| Obstruction duration ≤7 days | Obstruction duration >7 days | Total (N=1607) | |

| (group 1, n=913) | (group 2, n=694) | ||

| Male gender, n (%) | 538 (58.9) | 435 (62.7) | 973 (60.5) |

| Age (years) | 52 (39–62) | 56 (45–67) | 54 (41–64) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 220 (24.1) | 273 (39.3) | 493 (30.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 114 (12.5) | 156 (22.5) | 270 (16.8) |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 14 (1.5) | 16 (2.3) | 30 (1.9) |

| Obstruction release procedure, n (%) | |||

| Spontaneous release | 71 (7.7) | 17 (2.5) | 88 (5.4) |

| Double-J stenting | 269 (29.5) | 236 (34.0) | 505 (31.4) |

| Percutaneous nephrostomy | 31 (3.4) | 21 (3.0) | 52 (3.2) |

| Operation (stone removal) | 206 (22.6) | 288 (41.5) | 494 (30.7) |

| ESWL | 336 (36.8) | 132 (19.0) | 468 (29.1) |

| Obstruction duration (days) | 3.0 (3.0–5.0) | 18.0 (11.0–31.3) | 6.0 (2.0–15.0) |

| Baseline SCr (mg/dL) | 0.80 (0.42–0.96) | 0.80 (0.66–1.00) | 0.80 (0.65–0.98) |

| Baseline eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2)* | 94.89 (78.66–113.66) | 91.67 (74.68–112.77) | 93.62 (77.00–113.43) |

| SCr on admission (mg/dL) | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) | 1.00 (0.80–1.20) | 1.00 (0.80–1.21) |

| eGFR on admission (mL/min/1.73 m2)* | 74.14 (58.15–91.37) | 74.76 (57.19–90.92) | 74.54 (57.81–91.25) |

| Performed imaging modality for diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| KUB | 43 (4.7) | 75 (10.8) | 118 (7.3) |

| Kidney sonography | 11 (1.2) | 6 (0.9) | 17 (1.1) |

| CT | 696 (76.2) | 493 (71.0) | 1189 (74) |

| IVP | 163 (17.9) | 120 (17.3) | 283 (17.6) |

| Hydronephrosis grade, n (%) | |||

| Grade 0 (no hydronephrosis) | 179 (20.9) | 141 (23.0) | 320 (21.8) |

| Grade 1 | 202 (23.6) | 115 (18.8) | 317 (21.6) |

| Grade 2 | 365 (42.6) | 172 (28.1) | 537 (36.6) |

| Grade 3 | 94 (11.0) | 117 (19.1) | 211 (14.4) |

| Grade 4 | 17 (2.0) | 67 (11.0) | 94 (5.8) |

| Obstruction side, n (%) | |||

| Left | 456 (50.2) | 328 (47.7) | 784 (49.1) |

| Right | 393 (43.3) | 300 (43.6) | 693 (43.4) |

| Bilateral | 35 (3.8) | 26 (3.8) | 61 (3.8) |

| Undefined | 24 (2.6) | 34 (4.9) | 58 (3.7) |

| Stone size (mm) | 5.6 (4.3–7.7) | 7.7 (5.6–10.9) | 6.5 (4.8–9.0) |

| Pain killer, n (%) | |||

| No use | 169 (18.5) | 159 (22.9) | 328 (20.4) |

| NSAIDs (old)† | 293 (32.1) | 195 (28.1) | 488 (30.4) |

| NSAIDs (new)‡ | 389 (42.6) | 303 (43.7) | 692 (43.1) |

| Narcotic analgesics | 62 (6.8) | 37 (5.3) | 99 (6.2) |

*eGFR was calculated using the Isotope Dilution Mass Spectrometry (IDMS) traceable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation (mL/min/1.73 m2).

†Old NSAIDs: naproxen, aceclofenac and ketorolac.

‡New NSAIDs: talniflumate.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate;ESWL, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy; IVP, intravenous pyelogram; KUB, kidney ureter bladder X-ray;NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SCr, serum creatinine.

Obstruction duration was at least 0 days (obstruction release at the day of symptom onset), with the maximum being 1099 days; the median obstruction duration was 6 days (IQR 2–15 days), and the mean obstruction duration was 16.6 days. APN due to obstruction was observed in 14.6% of patients, and the mean CRP value of patients with APN was 54.8 mg/L. Patients with HT, DM and CKD had significantly higher rates of APN (19.3% in HT, 23% in DM and 43.3% in CKD), accompanied by obstructive uropathy. AKI was observed in 629 patients (39.1%): 467 (74.2%) were stage I, 101 (16.1%) were stage II and 61 (9.7%) were stage III. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were prescribed for pain control in 73.5% of patients. The mean follow-up duration of patients was 18.4 months.

When comparing obstruction release time within 7 days (group 1) and obstruction release time over 7 days (group 2), patients in group 2 were older and the prevalence of HT and type 2 DM was significantly higher. No significant differences were found in serum Cr and eGFR values between the two groups at the time of admission for obstructive uropathy due to urolithiasis.

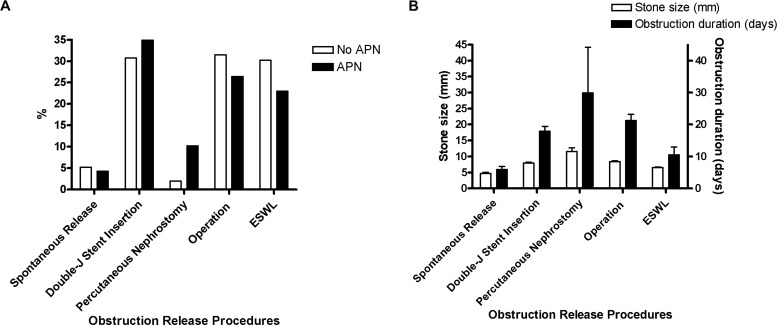

In group 1, 7.4% of patients were spontaneously released, whereas in group 2 only 1.9% were spontaneously released. Percutaneous nephrostomy was performed more frequently in patients with APN than in non-APN patients (10.2% vs 2.0%; figure 1).

Figure 1.

Performed obstruction release procedures by APN, stone size and obstruction duration. (A) Percutaneous nephrostomy was performed more frequently in patients with APN compared with non-APN patients (10.2% vs 2.0%). (B) Stone size was significantly different according to the obstruction release method (p<0.001). Patients who had the obstruction released through percutaneous nephrostomy showed the longest obstruction duration. APN, acute pyelonephritis; ESWL, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy.

Stone size was significantly different according to the obstruction release method, as it was 4.7±2.8 mm in the spontaneous release group and 11.6±7.9 mm in the percutaneous nephrostomy group (figure 1B). Group 1 patients were more likely to take CT as diagnostic modality and to have hydronephrosis less than grade II.

Baseline data of subcategorisation by APN and/or AKI

The baseline characteristics of 1607 patients subcategorised by APN and/or AKI are described in table 2. In group 1, obstruction duration tended to be longer in patients with complications. However, in group 2, obstruction duration was longer in patients without complications. In both groups 1 and 2, the prevalence of underlying diseases such as HT, DM and baseline CKD was higher in patients with AKI. NSAID was the most commonly used analgesic in these patients. However, only those with both APN and AKI had more narcotic analgesics prescriptions. Patients with AKI showed a lower initial eGFR compared with patients without AKI at the time of admission. People who had the obstruction released within 7 days and people with complications (APN or AKI) tended to have a larger stone size, but those with the obstruction released after more than 7 days did not show any correlation.

Table 2.

Characteristics according to obstruction duration and AKI/APN

| Obstruction duration ≤7 days (group 1) | Obstruction duration >7 days (group 2) | |||||||

| APN−AKI− (n=504) |

APN−AKI+ (n=267) |

APN+AKI− (n=38) |

APN+AKI+ (n=103) |

APN−AKI− (n=413) |

APN−AKI+ (n=188) |

APN+AKI− (n=24) |

APN+AKI+ (n=69) |

|

| Male gender, n (%) | 287 (56.9) | 182 (68.2) | 13 (34.2) | 55 (53.4) | 251 (60.8) | 135 (71.8) | 10 (41.7) | 39 (56.5) |

| Age | 48.0 (37.0–58.0) | 55.0 (42.0–65.0) | 52.5 (39.0–69.0) | 60.0 (50.0–69.5) | 54.0 (43.0–63.0) | 59.0 (48.0–67.0) | 55.5 (40.5–67.5) | 67.0 (56.0–76.0) |

| Obstruction release procedure, n (%) | ||||||||

| Spontaneous release | 46 (9.1) | 16 (6.0) | 4 (10.5) | 5 (4.9) | 10 (2.3) | 4 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.4) |

| Double-J stenting | 142 (28.2) | 78 (29.2) | 11 (29.0) | 38 (36.9) | 139 (33.7) | 63 (33.5) | 11 (45.8) | 23 (33.3) |

| PCN | 8 (1.6) | 6 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (16.5) | 7 (1.7) | 8 (4.3) | 1 (4.2) | 5 (7.3) |

| Operation (stone removal) | 106 (21.0) | 66 (24.7) | 14 (36.8) | 20 (19.4) | 182 (44.1) | 78 (41.5) | 6 (25.0) | 22 (31.9) |

| ESWL | 202 (40.1) | 101 (37.8) | 9 (23.7) | 23 (22.3) | 75 (18.2) | 35 (18.6) | 6 (25.0) | 16 (23.2) |

| Obstruction duration | 3.0 (1.0–5.0) | 3.0 (1.5–4.0) | 4.0 (2.0–6.0) | 4.0 (2.0–5.0) | 21.0 (12.0–33.0) | 15.0 (10.0–30.0) | 16.0 (10.0–27.0) | 15.0 (10.0–27.0) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 87 (17.3) | 85 (31.8) | 10 (26.3) | 38 (36.9) | 137 (33.2) | 88 (46.8) | 7 (29.2) | 41 (59.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 37 (7.3) | 47 (17.6) | 4 (10.5) | 26 (25.2) | 67 (16.2) | 57 (30.3) | 4 (16.7) | 28 (40.6) |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (6.8) | 2 (0.5) | 7 (3.7) | 1 (4.2) | 6 (8.7) |

| Pain killer, n (%) | ||||||||

| No use | 59 (11.7) | 60 (22.5) | 9 (23.7) | 41 (39.8) | 58 (14.0) | 58 (30.9) | 7 (29.2) | 36 (52.2) |

| NSAIDs (old)* | 20 (4.0) | 19 (7.1) | 5 (13.2) | 18 (17.5) | 17 (4.1) | 10 (5.3) | 1 (4.2) | 9 (13.0) |

| NSAIDs (new)† | 251 (49.8) | 100 (37.5) | 17 (44.7) | 21 (20.4) | 214 (51.8) | 70 (37.2) | 9 (37.5) | 10 (14.5) |

| Narcotic analgesics | 174 (34.5) | 88 (33.0) | 7 (18.4) | 23 (22.3) | 124 (30.0) | 50 (26.6) | 7 (29.2) | 14 (20.3) |

| Baseline SCr (mg/dL) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 0.7 (0.5–0.8) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) |

| Baseline eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2)‡ |

96.6 (81.0–112.9) | 91.4 (74.5–113.8) | 105.2 (89.7–126.4) | 93.7 (73.4–111.3) | 94.0 (79.1–113.7) | 91.3 (68.7–114.9) | 92.4 (69.1–109.2) | 79.1 (59.6–103.4) |

| SCr on admission (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) | 1.2 (1.0–1.6) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 1.6 (1.1–2.0) |

| eGFR on admission (mL/min/1.73 m2)‡ |

85.6 (73.7–99.7) | 58.0 (46.7–69.1) | 80.6 (68.6–100.2) | 48.4 (34.1–63.9) | 83.5 (71.8–100.7) | 57.6 (43.9–73.5) | 75.6 (59.5–91.9) | 40.9 (31.0–61.6) |

| Performed imaging modality for diagnosis, n (%) | ||||||||

| KUB | 3 (6.0) | 10 (3.8) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (1.9) | 47 (11.4) | 26 (13.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.9) |

| Kidney sonography | 8 (1.6) | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) |

| CT | 368 (73.0) | 198 (74.2) | 35 (92.1) | 94 (91.3) | 283 (68.5) | 128 (68.1) | 21 (87.5) | 61 (88.4) |

| IVP | 98 (19.4) | 56 (21.0) | 2 (5.3) | 7 (6.8) | 79 (19.1) | 33 (17.6) | 3 (12.5) | 5 (7.3) |

| Hydronephrosis grade, n (%) | ||||||||

| No hydronephrosis | 127 (25.2) | 37 (13.9) | 4 (10.5) | 11 (10.7) | 97 (23.5) | 28 (14.9) | 7 (29.2) | 9 (13.0) |

| Grade 1 | 116 (23.0) | 55 (20.6) | 12 (31.6) | 19 (18.5) | 65 (15.7) | 34 (18.1) | 3 (12.5) | 13 (18.8) |

| Grade 2 | 178 (35.3) | 120 (44.9) | 18 (47.4) | 48 (46.6) | 98 (23.7) | 48 (25.5) | 6 (25.0) | 20 (29.0) |

| Grade 3 | 39 (7.7) | 34 (12.7) | 3 (7.9) | 18 (17.5) | 66 (16.0) | 30 (16.0) | 6 (25.0) | 16 (23.2) |

| Grade 4 | 7 (1.4) | 5 (1.9) | 1 (2.6) | 4 (3.9) | 36 (8.7) | 22 (11.7) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (11.6) |

| Obstruction side, n (%) | ||||||||

| Left | 252 (50.4) | 132 (49.6) | 21 (55.3) | 50 (48.5) | 190 (46.3) | 92 (49.7) | 12 (50.0) | 34 (49.3%) |

| Right | 210 (42.0) | 121 (45.5) | 13 (34.2) | 49 (47.6) | 179 (43.7) | 76 (41.1) | 11 (45.8) | 34 (49.3) |

| Bilateral | 4 (0.8) | 5 (1.9) | 2 (5.3) | 3 (2.9) | 9 (2.2) | 4 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Undefined | 19 (3.8) | 5 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (5.6) | 10 (5.4) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Stone size (mm) | 5.3 (4.1–7.34) | 6.0 (4.6–7.7) | 6.0 (4.8–6.9) | 6.1 (4.8–8.9) | 7.6 (5.6–10.7) | 8.4 (5.8–12.0) | 6.3 (4.1–9.4) | 8.2 (6.2–10.0) |

*Old NSAIDs: naproxen, aceclofenac and ketorolac.

†New NSAIDs: talniflumate.

‡eGFR was calculated using the Isotope Dilution Mass Spectrometry (IDMS) traceable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation (mL/min/1.73 m2).

AKI, acute kidney injury; APN, acute pyelonephritis; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESWL, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy; IVP, intravenous pyelogram; KUB, kidney ureter bladder X-ray;NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PCN, percutaneous nephrostomy; SCr, serum creatinine.

Outcome by obstruction duration

In this study, APN occurred more frequently in group 2 patients compared with group 1 patients (29.3% vs 10.2%, p<0.001). The last SCr (0.86 vs 0.90 mg/dL, p=0.004) and eGFR (87 vs 81 mL/min/1.73 m2, p=0.001) also showed worse renal function in group 2 patients (table 3).

Table 3.

Outcome variables by obstruction duration

| Obstruction duration ≤7 days | Obstruction duration >7 days | Total (N=1607) | P value | |

| (group 1, n=913) | (group 2, n=694) | |||

| Acute pyelonephritis, n (%) | 24 (10.2) | 46 (29.3) | 235 (14.6) | <0.001 |

| Peak CRP (mg/L) | 3.3 (0.8–42.3) | 31.3 (1.7–145.0) | 5.9 (1.0–73.3) | <0.001 |

| Peak SCr during admission (mg/dL) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.454 |

| Lowest eGFR during admission (mL/min/1.73 m2)* |

72.4 (56.1–89.6) | 71.9 (53.4–88.6) | 72.0 (55.1–89.0) | 0.307 |

| AKI, n (%) | ||||

| No AKI | 542 (59.4) | 436 (62.8) | 978 (60.9) | 0.491 |

| KDIGO stage I | 274 (30.0) | 192 (27.7) | 466 (29.0) | |

| KDIGO stage II | 62 (6.8) | 39 (5.6) | 101 (6.3) | |

| KDIGO stage III | 34 (3.7) | 27 (3.9) | 61 (3.8) | |

| GFR 30% reduction, n (%) | 100 (11.0) | 105 (15.1) | 205 (12.8) | 0.016 |

| GFR 50% reduction, n (%) | 24 (2.6) | 39 (5.6) | 63 (3.9) | 0.003 |

| Final SCr (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.004 |

| Final eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2)* | 87.0 (71.1–102.4) | 81.0 (64.0–100.5) | 84.4 (68.3–101.1) | 0.001 |

| ΔGFR/year | 2.5 (0.0–35.8) | 5.7 (0.0–162.8) | 4.0 (0.0–78.5) | 0.004 |

*eGFR was calculated using the Isotope Dilution Mass Spectrometry (IDMS) traceable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation (mL/min/1.73 m2).

AKI, acute kidney injury;CRP, C reactive protein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate;GFR, glomerular filtration rate; KDIGO, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes; SCr, serum creatinine.

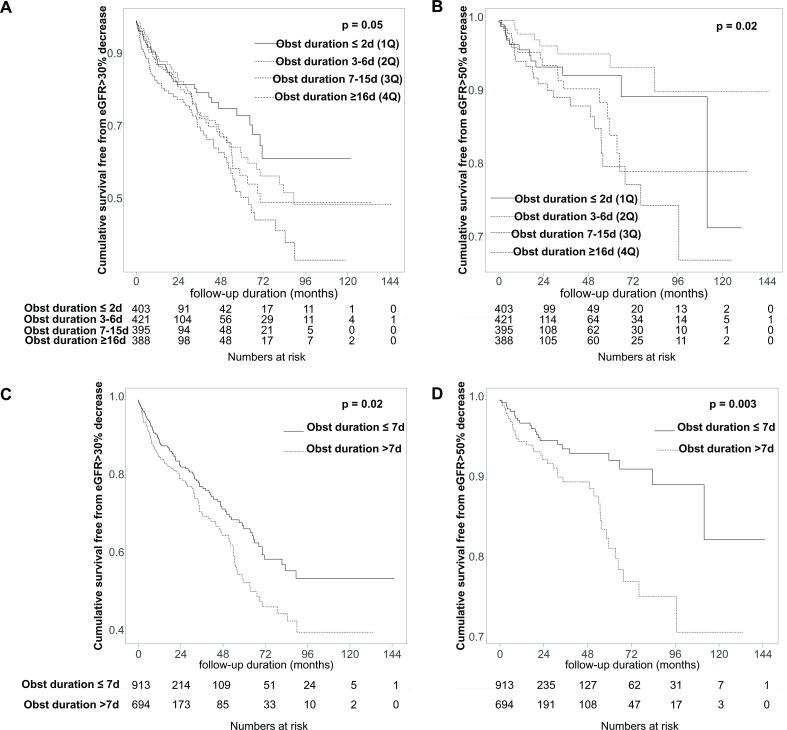

When the prognosis was evaluated by quartile of obstruction duration of all patients, the longer the obstruction duration the greater the likelihood of a decrease in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) more than 30% (log-rank p for pooled analysis=0.052, pairwise analysis; p=0.009 for first quartile vs third quartile, p=0.037 for second quartile vs third quartile; figure 2A) and a decrease in GFR of more than 50% (log-rank p for pooled analysis=0.016, pairwise analysis; p=0.002 for second quartile vs third quartile, p=0.022 for second quartile vs fourth quartile; figure 2B), respectively. When we compared the results of the two groups, there was a significant increase in the possibility of GFR reduction >30% (log-rank p=0.022, HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.81; figure 2C) and >50% (log-rank p=0.003, HR 2.12, 95% CI 1.27 to 3.53; figure 2D) in group 2 (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for renal outcomes. (A, B) When the prognosis was evaluated by quartile of obstruction duration of all patients, the longer the obstruction duration the greater the likelihood of a decrease in GFR of more than 30% (log-rank p for pooled analysis=0.052, pairwise analysis; p=0.009 for 1Q vs 3Q, p=0.037 for 2Q vs 3Q) (A) and a decrease in GFR of more than 50% (p for pooled analysis=0.016, pairwise analysis; p=0.002 for 2Q vs 3Q, p=0.022 for 2Q vs 4Q) (B). (C, D) When we compared the results of the two groups, there was a significant increase in the possibility of GFR reduction >30% (p=0.022) (C) and >50% (p=0.003) (D) in group 2. 1Q, first quartile; 2Q, second quartile; 3Q, third quartile; 4Q, fourth quartile; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; Obst, obstruction.

Outcome by APN and/or AKI

Patients who did not have APN or AKI in group 1 had no events, with a GFR reduction of more than 50% (table 4).

Table 4.

Outcomes according to the obstruction duration and AKI/APN

| Obstruction duration ≤7 days (group 1) | Obstruction duration >7 days (group 2) | |||||||||

| APN−AKI− (n=504) |

APN−AKI+ (n=267) |

APN+AKI− (n=38) |

APN+AKI+ (n=103) |

P value | APN−AKI− (n=413) |

APN−AKI+ (n=188) |

APN+AKI− (n=24) |

APN+AKI+ (n=69) |

P value | |

| Peak CRP (mg/L) | 1.0 (0.4–2.5) | 1.4 (0.7–3.3) | 69.2 (29.0–122.6) | 78.4 (33.5–171.2) | <0.001 | 1.1 (0.4–2.1) | 1.6 (0.9–3.7) | 55.1 (28.6–95.6) | 141.3 (61.0–224.3) | <0.001 |

| Peak SCr (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | <0.001 | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 1.3 (1.1–1.7) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 1.8 (1.3–2.6) | <0.001 |

| Lowest eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2)* | 84.4 (72.9–97.9) | 55.1 (44.6–66.4) | 79.1 (68.6–98.4) | 46.2 (32.1–59.7) | <0.001 | 81.1 (69.2–97.0) | 54.9 (41.0–69.1) | 74.2 (58.0–82.7) | 36.9 (25.0–50.7) | <0.001 |

| GFR 30% reduction, n (%) | 21 (4.17) | 48 (18.0) | 6 (15.8) | 25 (24.3) | <0.001 | 32 (7.8) | 50 (26.6) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (33.3) | <0.001 |

| GFR 50% reduction, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (3.8) | 1 (2.6) | 13 (12.6) | <0.001 | 8 (1.9) | 18 (9.6) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (18.8) | <0.001 |

| Final SCr (mg/dL) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 0.9 (0.8–1.2) | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | <0.001 | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.8 (0.7–1.1) | 1.1 (0.8–1.7) | <0.001 |

| Final eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2)* | 90.5 (75.5–105.8) | 80.3 (63.4–97.6) | 92.0 (81.5–109.4) | 76.7 (60.1–95.8) | <0.001 | 86.0 (73.0–103.2) | 75.8 (53.7–97.8) | 78.0 (64.2–100.2) | 61.1 (38.4–85.4) | <0.001 |

*eGFR was calculated using the Isotope Dilution Mass Spectrometry (IDMS) traceable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation (mL/min/1.73 m2).

AKI, acute kidney injury; APN, acute pyelonephritis; CRP, C reactive protein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate;GFR, glomerular filtration rate; SCr, serum creatinine.

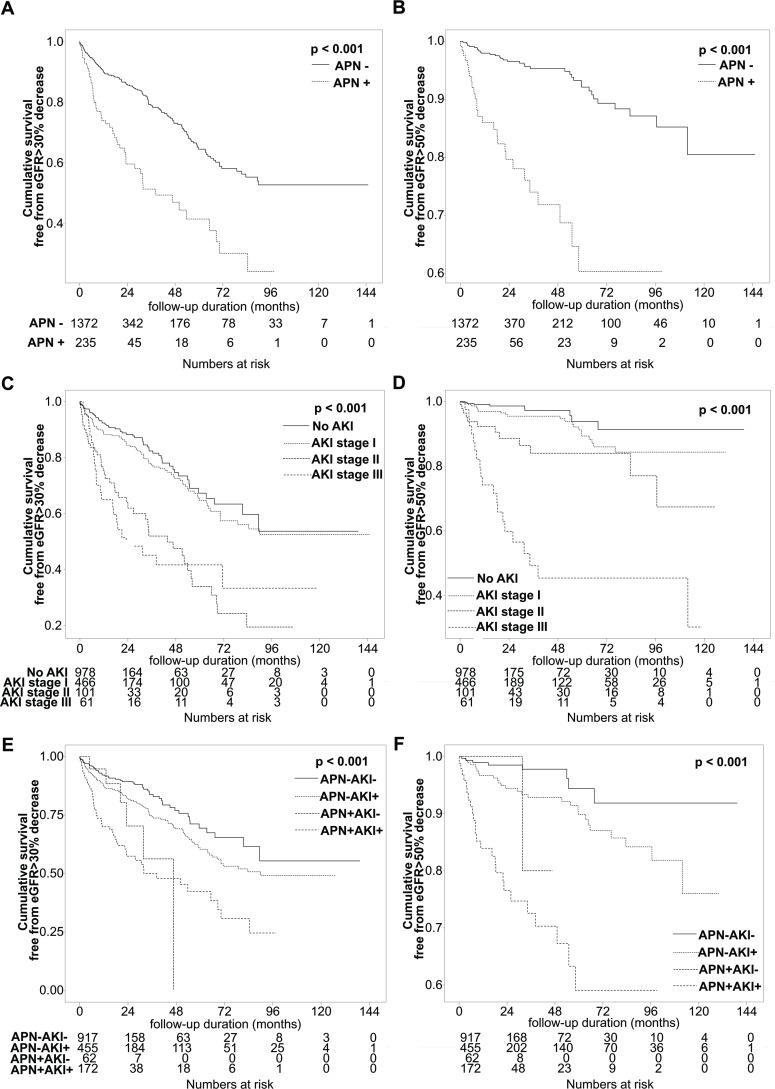

When examining the effect of APN during hospitalisation with obstructive uropathy on renal outcome, patients with APN were significantly more likely to have a GFR reduction >30% (log-rank p<0.001, HR 2.61, 95% CI 1.91 to 3.56; figure 3A) and a GFR reduction >50% (log-rank p<0.001, HR 5.81, 95% CI 3.50 to 9.63; figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for renal outcomes by occurrence of APN and/or AKI. (A, B) Patients with APN were significantly more likely to have a GFR reduction >30% (p<0.001) (A) and a GFR reduction >50% (p<0.001) (B). (C, D) In patients with severe AKI of grade II or III, the probability of GFR reduction >30% (p for pooled analysis <0.001, HR 1.58, 95% CI 1.37 to 1.82, pairwise analysis; p<0.001 for no AKI vs AKI stage II or III, and AKI stage I vs stage II or III) (C) and >50% (p for pooled analysis <0.001, HR 2.62, 95% CI 2.05 to 3.34, pairwise analysis; p<0.001 for no AKI vs AKI stage II or III, p=0.035 for AKI stage I vs II, p<0.001 for AKI stage I vs III, and p=0.001 for AKI stage II vs III) (D) was significantly higher than the others. (E, F) The prognosis was best when neither AKI nor APN was present, and the prognosis was progressively worse with AKI alone, APN alone, and both AKI and APN, consecutively (p for pooled analysis <0.001, HR 1.50, 95% CI 1.33 to 1.71, pairwise analysis: p=0.029 for AKI(−)APN(−) vs AKI(+), p=0.027 for AKI(−)APN(−) vs APN(+), p<0.001 for AKI(−)APN(−) vs AKI(+)APN(+), and p<0.001 for AKI(+) vs AKI(+)APN(+) (E); p<0.001 for pooled analysis, HR 2.18, 95% CI 1.75 to 2.71, pairwise analysis: p=0.024 for AKI(−)APN(−) vs AKI(+), p<0.001 for AKI(−)APN(−) vs AKI(+)APN(+), and p<0.001 AKI(+) vs AKI(+)APN(+) (F)). APN, acute pyelonephritis; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

When we examined the renal outcome according to the extent of AKI during hospitalisation, AKI stage I showed a favourable outcome. However, in patients with severe AKI of grade II or III, the probability of GFR reduction >30% (log-rank p for pooled analysis <0.001, HR 1.58, 95% CI 1.37 to 1.82, pairwise analysis; p<0.001 for no AKI vs AKI stage II or III, and AKI stage I vs stage II or III; figure 3C) and >50% (log-rank p for pooled analysis <0.001, HR 2.62, 95% CI 2.05 to 3.34, pairwise analysis; p<0.001 for no AKI vs AKI stage II or III, p=0.035 for AKI stage I vs II, p<0.001 for AKI stage I vs III, p=0.001 for AKI stage II vs III; figure 3D) was significantly higher than the others.

The prognosis was best when neither AKI nor APN was present, and the prognosis was progressively worse with AKI alone, APN alone and both AKI and APN, consecutively (log-rank p for pooled analysis <0.001, HR 1.50, 95% CI 1.33 to 1.71, pairwise analysis: p=0.029 for AKI(−)APN(−) vs AKI(+), p=0.027 for AKI(−)APN(−) vs APN(+), p<0.001 for AKI(−)APN(−) vs AKI(+)APN(+), and p<0.001 for AKI(+) vs AKI(+)APN(+), figure 3E; log-rank p<0.001 for pooled analysis, HR 2.18, 95% CI 1.75 to 2.71, pairwise analysis: p=0.024 for AKI(−)APN(−) vs AKI(+), p<0.001 for AKI(−)APN(−) vs AKI(+)APN(+), and p<0.001 AKI(+) vs AKI(+)APN(+), figure 3F).

Factors affecting renal outcomes

We conducted multivariate analysis for the occurrence of a decrease in eGFR >50%. When we adjusted for age, sex, HT, DM, APN, AKI and obstruction duration group (defined by before and after 7 days), we found that concomitant APN (HR 3.495, 95% CI 1.942 to 6.289, p<0.001), concomitant AKI (HR 3.284, 95% CI 1.354 to 7.965, p=0.009 for AKI stage II; HR 6.425, 95% CI 2.599 to 15.881, p<0.001 for AKI stage III) and obstruction duration >7 days (HR 1.854, 95% CI 1.095 to 3.140, p=0.001) were independently associated with an eGFR decrease of >50% (table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis for the occurrence of eGFR decrease of >50%

| HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Female | 1.177 | 0.691 to 2.006 | 0.548 |

| Age | 1.017 | 0.997 to 1.037 | 0.103 |

| Hypertension | 1.743 | 0.994 to 3.057 | 0.053 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.939 | 0.533 to 1.656 | 0.829 |

| Acute pyelonephritis | 3.495 | 1.942 to 6.289 | <0.001 |

| Acute kidney injury | |||

| Stage I | 1.580 | 0.706 to 3.536 | 0.265 |

| Stage II | 3.284 | 1.354 to 7.965 | 0.009 |

| Stage III | 6.425 | 2.599 to 15.881 | <0.001 |

| Group 2 (obstruction duration >7 days) | 1.854 | 1.095 to 3.140 | 0.022 |

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

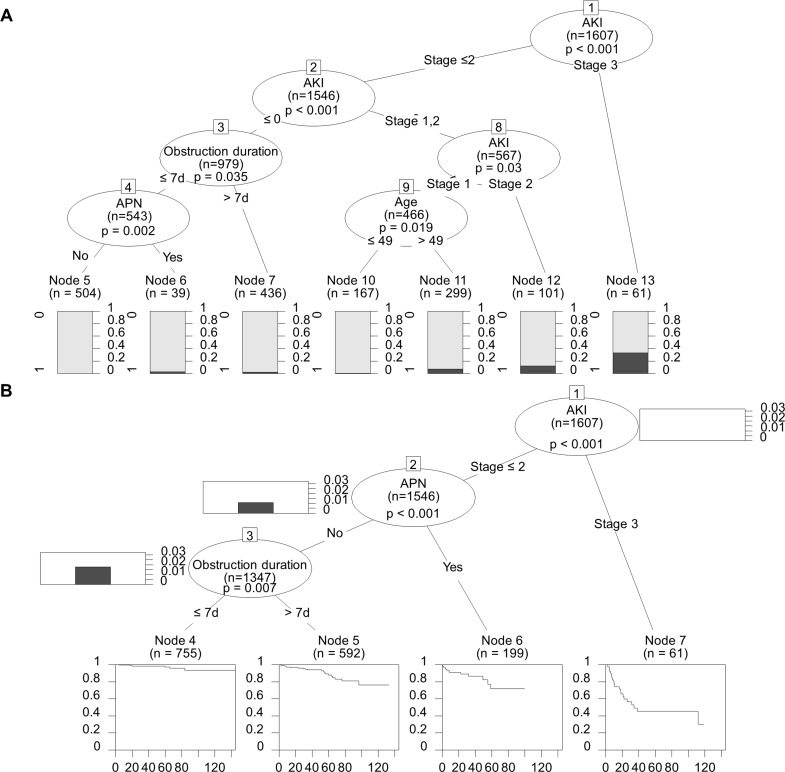

Tree analysis

Using a decision tree model, AKI stage III was identified at the first decision node as being the most important risk factor. It predicted a rate of GFR decrease >50% of 31.7% (p<0.001; figure 4A). The second most important risk factor was AKI stage II (p=0.03). An age >49 years at the time of obstructive uropathy was selected at the next node in the group of patients with AKI stage I (p=0.019). Concomitant APN during the obstruction episode was presented for the next node in the group of patients without AKI, and the obstruction duration is <7 days (p=0.002). An obstruction duration >7 days was selected at the next node in the group of patients without AKI (p=0.035). Input variables were sex, age, APN, AKI stage and obstruction duration group; the accuracy of this tree analysis was 96.1%.

Figure 4.

Tree analyses. (A) In a decision tree model, AKI was the most important risk factor for the GFR decrease >50% (p<0.001). The second most important risk factor was AKI stage II (p=0.03). An age >49 years at the time of obstructive uropathy was selected at the next node in the group of patients with AKI stage I (p=0.019). Concomitant APN during the obstruction episode was presented for the next node in the group of patients without AKI and the obstruction duration is <7 days (p=0.002). An obstruction duration >7 days was selected at the next node, in the group of patients without AKI (p=0.035). (B) In a survival tree analysis with the variables sex, age, APN, AKI stage and obstruction duration groups, AKI stage III (p<0.001) was the most potent factor for the development of a GFR decrease >50%; APN was the second highest factor (p<0.001). An obstruction duration of more than 7 days (p=0.007) was also an independent risk factor for major renal outcomes in the survival tree analysis. AKI, acute kidney injury; APN, acute pyelonephritis; GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

When we performed a survival tree analysis with the variables sex, age, APN, AKI stage and obstruction duration groups, AKI stage III (p<0.001) was the most potent factor for the development of a GFR decrease >50% and APN (p<0.001) was the second. An obstruction duration of more than 7 days (p=0.007) was also an independent risk factor for major renal outcome in the survival tree analysis (figure 4B).

Discussion

In this study, we discovered that obstructive uropathy caused by urolithiasis had the worst effect on renal outcome in patients with stage II or higher AKI at the time of obstruction. We also found that patients with APN and obstruction release after 7 days or more were associated with poor prognosis.

In general, renal failure due to unilateral renal stones is known to be rare.20 In some previous studies, the incidence of acute renal injury due to renal stones was reported to be in the range of 0.72%–9.7%, and AKI affects the development or progression of CKD.21 22 However, in this study, AKI occurred in 39.1% of patients with unilateral obstructive uropathy, and even if only patients with AKI stage II or III, excluding AKI stage I, were included AKI was associated in 10.1%. Unilateral ureteral obstruction is known to result in GFR reduction due to renal vasoconstriction related to tubuloglomerular feedback, as the intratubular pressure is increased.23 Furthermore, recurrent episodes of obstructive uropathy by urolithiasis and obstructive uropathy in single kidneys have a high risk of deteriorating renal function. In the presence of underlying latent CKD, even unilateral obstructive uropathy may cause acute renal function decline due to insufficient compensation in the opposite kidney.20 Nephrolithiasis itself is known to cause interstitial fibrosis and glomerulosclerosis due to inflammatory cascade stimulation, as well as the recurrence of episodes and infection of the occlusion, ultimately increasing the risk of CKD and ESRD.24 25

In group 2 patients with obstruction release after 7 days, the obstruction duration was longer when there were no complications. Considering the features and limitations of this retrospective study, complications such as AKI or APN urgently needed obstacle release. This is probably because obstruction release was performed more quickly than those without AKI or APN. Conversely, in the case of asymptomatic urolithiasis, which did not cause any particular complications, selection bias could be possible since treatment was not performed in an urgent manner. Nevertheless, when AKI and APN were both adjusted, various statistical analyses confirmed the association of poor renal outcome with those who had an obstruction duration of more than 7 days. It seemed to be important to release the obstruction as soon as possible.

In the present study, NSAIDs were the most commonly considered analgesics, as recommended by the guideline.26 Only those with both APN and AKI tended to use narcotic analgesics instead of NSAIDs. This is probably because people with both APN and AKI had the worst renal function. People with AKI alone were either not aware of AKI as it was very mild or did not consider it significant enough to have any effect on NSAID usage.

When accompanied with sepsis, decompression therapy by percutaneous nephrostomy was performed frequently in patients with APN, which was consistent with the guideline recommending urgent decompression, such as percutaneous drainage.27 28

In this study, the most important prognostic factors of renal outcome were AKI stage II or III, APN and obstruction duration, from both multivariate analyses and the decision tree analysis. Although renal insult due to the occurrence of obstructive uropathy should have been apparent, decision tree analysis showed a good prognosis for renal function if both AKI and APN are absent and the obstruction was released within 7 days. The result showed that performing obstruction release as soon as possible, even for those without complications, is important for improved renal outcome.

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design, and the results cannot prove a causal relationship. However, considering the difficulties in performing a randomised controlled trial, it is possible to consider that lowering the incidence of AKI or APN through early obstruction release may have an additional benefit in improving prognosis. Especially in patients with recurrent urolithiasis, it would be better to minimise the insult to the patient’s kidney per episode. In addition, the retrospective aspect of this study may introduce selection bias and misclassification.

In addition, although the date of symptom occurrence and the date of obstruction release were collected from electronic medical records, there is a possibility that the symptom date was inaccurate and that it was not an obstruction-specific date. As evidence was required for the spontaneous resolution of obstruction release dates, the actual date may be later than the date on which the symptoms were relieved.

Obstruction duration is an independent risk factor for poor renal outcome with concomitant APN and AKI in urolithiasis-related obstructive uropathy. Early obstruction release may contribute to the improvement of prognosis by reducing the incidence of infection or acute renal failure.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Research idea and study design: JHH. Data acquisition: EHL, S-HK, J-HS, SBP, BHC, JHH. Data analysis/interpretation: EHL, SBP, BHC, JHH. Statistical analysis: S-HK, J-HS, JHH. Supervision or mentorship: JHH. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision, and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This study was supported by a research grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Korean government (NRF-2018R1C1B6007937).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by Chung-Ang University Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB number: 1810-008-16212), and the need for informed consent was waived as this study used a retrospective design. All clinical investigations were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository.

References

- 1. Morgan MSC, Pearle MS. Medical management of renal stones. BMJ 2016;352 10.1136/bmj.i52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Romero V, Akpinar H, Assimos DG. Kidney stones: a global picture of prevalence, incidence, and associated risk factors. Rev Urol 2010;12:e86–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. López M, Hoppe B. History, epidemiology and regional diversities of urolithiasis. Pediatr Nephrol 2010;25:49–59. 10.1007/s00467-008-0960-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stamatelou KK, Francis ME, Jones CA, et al. Time trends in reported prevalence of kidney stones in the United States: 1976-1994. Kidney Int 2003;63:1817–23. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00917.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Indridason OS, Birgisson S, Edvardsson VO, et al. Epidemiology of kidney stones in Iceland: a population-based study. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2006;40:215–20. 10.1080/00365590600589898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yasui T, Okada A, Hamamoto S, et al. The association between the incidence of urolithiasis and nutrition based on Japanese National health and nutrition surveys. Urolithiasis 2013;41:217–24. 10.1007/s00240-013-0567-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jung JS, Han CH, Bae S. Study on the prevalence and incidence of urolithiasis in Korea over the last 10 years: an analysis of national health insurance data. Investig Clin Urol 2018;59:383–91. 10.4111/icu.2018.59.6.383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ansari MS, Gupta NP. Impact of socioeconomic status in etiology and management of urinary stone disease. Urol Int 2003;70:255–61. 10.1159/000070130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bartoletti R, Cai T, Mondaini N, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors in urolithiasis. Urol Int 2007;79:3–7. 10.1159/000104434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ferrari P, Piazza R, Ghidini N, et al. Lithiasis and risk factors. Urol Int 2007;79:8–15. 10.1159/000104435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jeong IG, Kang T, Bang JK, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and the presence of kidney stones in a screened population. Am J Kidney Dis 2011;58:383–8. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lotan Y. Economics and cost of care of stone disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2009;16:5–10. 10.1053/j.ackd.2008.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Trinchieri A. Epidemiological trends in urolithiasis: impact on our health care systems. Urol Res 2006;34:151–6. 10.1007/s00240-005-0029-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chawla LS, Kimmel PL. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease: an integrated clinical syndrome. Kidney Int 2012;82:516–24. 10.1038/ki.2012.208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Horne KL, Packington R, Monaghan J, et al. Three-Year outcomes after acute kidney injury: results of a prospective parallel group cohort study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015316 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hamdi A, Hajage D, Van Glabeke E, et al. Severe post-renal acute kidney injury, post-obstructive diuresis and renal recovery. BJU Int 2012;110:E1027–34. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11193.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wood K, Keys T, Mufarrij P, et al. Impact of stone removal on renal function: a review. Rev Urol 2011;13:73–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ashizawa K, Ozawa Y, Okauchi K. Comparative studies of elemental composition on ejaculated fowl, bull, rat, dog and boar spermatozoa by electron probe X-ray microanalysis. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol 1987;88:269–72. 10.1016/0300-9629(87)90482-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Klahr S, Harris K, Purkerson ML. Effects of obstruction on renal functions. Pediatr Nephrol 1988;2:34–42. 10.1007/BF00870378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gosmanova EO, Baumgarten DA, O'Neill WC. Acute kidney injury in a patient with unilateral ureteral obstruction. Am J Kidney Dis 2009;54:775–9. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang S-J, Mu X-N, Zhang L-Y, et al. The incidence and clinical features of acute kidney injury secondary to ureteral calculi. Urol Res 2012;40:345–8. 10.1007/s00240-011-0414-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hussain M, Hashmi AH, Rizvi SAH. Problems and prospects of neglected renal calculi in Pakistan: can this tragedy be averted? Urol J 2013;10:848–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gaudio KM, Siegel NJ, Hayslett JP, et al. Renal perfusion and intratubular pressure during ureteral occlusion in the rat. Am J Physiol 1980;238:F205–9. 10.1152/ajprenal.1980.238.3.F205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Keddis MT, Rule AD. Nephrolithiasis and loss of kidney function. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2013;22:390–6. 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32836214b9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Loeffler I, Wolf G. Transforming growth factor-β and the progression of renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014;29:i37–45. 10.1093/ndt/gft267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Türk C, Petřík A, Sarica K, et al. EAU guidelines on diagnosis and conservative management of urolithiasis. Eur Urol 2016;69:468–74. 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.07.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Assimos D, Krambeck A, Miller NL, et al. Surgical management of stones: American urological Association/Endourological Society guideline, part I. J Urol 2016;196:1153–60. 10.1016/j.juro.2016.05.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Assimos D, Krambeck A, Miller NL, et al. Surgical management of stones: American urological Association/Endourological Society guideline, part II. J Urol 2016;196:1161–9. 10.1016/j.juro.2016.05.091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030438supp001.pdf (48.4KB, pdf)