Abstract

Lexical iconicity—signs or words that resemble their meaning—is over-represented in children’s early vocabularies. Embodied theories of language acquisition predict that symbols are more learnable when they are grounded in a child’s first-hand experiences. As such, pantomimic iconic signs, which use the signer’s body to represent a body, might be more readily learned than other types of iconic signs. Alternatively, the Structure Mapping Theory of iconicity predicts that learners are sensitive to the amount of overlap between form and meaning. In this exploratory study of early vocabulary development in ASL, we asked whether type of iconicity predicts sign acquisition above and beyond degree of iconicity. We also controlled for concreteness and relevance to babies, two possible confounding factors. Highly concrete referents and concepts that are germane to babies may be amenable to iconic mappings. We re-analyzed a previously published set of ASL CDI reports from 58 deaf children learning ASL from their deaf parents (Anderson & Reilly, 2002). Pantomimic signs were more iconic than other types of iconic signs (perceptual, both pantomimic and perceptual, or arbitrary), but type of iconicity had no effect on acquisition. Children may not make use of the special status of pantomimic elements of signs. Their vocabularies are, however, shaped by degree of iconicity, which aligns with a Structure Mapping Theory of iconicity, though other explanations are also compatible (e.g., iconicity in child-directed signing). Previously demonstrated effects of type of iconicity may be an artifact of the increased degree of iconicity among pantomimic signs.

Keywords: type of iconicity, degree of iconicity, concreteness, babiness, sign language, vocabulary acquisition

Mounting evidence shows that, despite previous reports to the contrary (Meier, Mauk, Cheek, & Moreland, 2008; Orlansky & Bonvillian, 1984), children are sensitive to lexical iconicity, the ways in which word forms can represent characteristics of the referent (see Ortega, 2017 for a review). Spoken words iconically represent meaning in a variety of ways. For example, syllabic or lexical reduplication often indicates repeated events, and changing vowel length is associated with the duration of an action (see Dingemanse, Blasi, Lupyan, Christiansen, & Monaghan, 2015 for an overview). Moreover some phonemes consistently appear crosslinguistically in words representing specific concepts (e.g., /r/ for rough textures; Winter, Sóskuthy, & Dingmanse, 2017). What is represented iconically in a language may be shaped by language modality. In spoken English, auditory and tactile words exhibit the greatest levels of iconicity (Winter, Perlman, Perry, & Lupyan, 2017). On the other hand, lexical iconicity in a sign language more frequently picks out the visual features or action affordances of a referent, for example, tracing the outline of an object or enacting an action (Taub, 2001). Children learning language in either modality exploit these iconic features during language learning; they produce highly iconic words more frequently than less iconic words (Massaro & Perlman, 2017; Perry, Perlman, Winter, Massaro, & Lupyan, 2017; Perlman, Fusaroli, Fein, & Naigles, 2017), and iconicity significantly predicts early vocabulary development among deaf children exposed to a sign language (Caselli & Pyers, 2017; Thompson, Vinson, Woll, & Vigliocco, 2012). Yet, the mechanisms that underpin the effects of iconicity in early vocabulary development remain unclear. To better understand such mechanisms, we conducted an exploratory analysis of early sign language production where we asked whether any of three potentially related features, type of iconicity, concreteness, and relatedness to babyhood (“babiness”) could account for effects of degree of iconicity in sign acquisition.

Some studies of iconicity in early vocabulary development have used continuous ratings of iconicity that capture degree of iconicity from low to high (Caselli & Pyers, 2017; Massaro & Perlman, 2017; Perry, Perlman, & Lupyan, 2015; Thompson, et al, 2012). Yet, iconicity is not a one-dimensional construct. The forms of lexical items can capture different sensory features of a referent such as its visual, auditory, or tactile properties (Dingmanse, et al., 2015). In the visualmanual modality (e.g., gestures and signs), iconic signs vary in whether they depict the perceptual elements of the referent (e.g., shape), pantomimic elements of the referent (e.g., how the referent is used or enacting an animate referent), or a combination of the two (see Figure 2). In experimental studies investigating gesture learning (Magid & Pyers, 2017; Namy, 2008), sign recognition (Tolar, Lederberg, Gokhale, & Tomasello, 2007), and sign production (Ortega, Sumer, & Özyürek, 2017), preschoolers’ sensitivity to iconicity is shaped by type of iconicity, with pantomimic (action-based) gestures or signs recognized, learned, and produced earlier than iconic symbols that capture only perceptual elements of a referent. However, we do not know how type of iconicity and degree of iconicity relate to one another. Pantomimic signs may be more iconic than other types of signs. As such, the effects of degree of iconicity could be an artifact of an advantage for pantomimic signs (Ortega, 2017), or vice versa, effects of type of iconicity could be an artifact of an advantage for highly iconic signs.

Figure 2.

The signs BABY, BUTTERFLY, and GLASSES from left to right. The sign BABY was considered pantomimic because it is mimics how the arms hold a baby. The sign BUTTERFLY was considered perceptual because the hands are used to depict the wings of a butterfly. The sign GLASSES was considered both pantomimic and perceptual because the hand is used to depict the shape of the lens, and place of articulation (the eye) is also where glasses are worn.

Understanding the unique or shared effects of type and degree of iconicity on acquisition helps distinguish between two accounts of the role of iconicity in sign acquisition. The first has its roots in theories of embodied cognition that suggest that language creation, acquisition, and processing is shaped by the sensorimotor experiences of humans (e.g., Barsalou, 1999; Barsalou, 2009; Viglioco, Meteyard, Andrews, & Kousta, 2009), and motor experiences, in particular, shape the use of manual symbols (Cook & Tannenhaus, 2009). Thus, the acquisition of pantomimic signs may piggyback on children’s existing action schemas such that children may more readily leverage iconicity when they can map it to their first-hand motor experiences (Ortega et al., 2017). Some support for the link between action and representational form comes from studies of gesture use in children with autism spectrum disorder. Those with motor impairments are less likely to produce pantomimic instrumental gestures, where the hand holds an invisible object (e.g., holding an invisible toothbrush while gesturing brushing teeth), and they are more likely to produce gestures where the perceptual features of the referent are depicted (e.g., extending the index finger to represent a toothbrush; Eigsti, 2013; Smith & Bryson, 2007).

Alternatively, Structure Mapping Theory (Gentner, 1983), a cognitive framework that attempts to explain how humans understand analogical relations, has been used as a way of explaining how people access and use iconicity in language given that iconicity is an analogical representation of a referent (Emmorey, 2013). Signs may vary in the degree of alignment between elements of the form and the elements of meaning (i.e., how distal the mappings are). Over the course of development, children become able to make more and more distal mappings between a symbol and a referent. In a classic study of symbolic representation, two-year-olds succeeded in interpreting a model of a room when the surface features of that model were identical to the room (DeLoche, Kolstad, & Anderson, 1991); only as they developed were they able to correctly interpret more abstract representations of room-elements (e.g., a block in the model represents a chair in the room; Gentner & Ratterman, 1991). We posit that a Structure Mapping Theory of iconicity in acquisition would predict that signs in with high degrees of alignment between form and meaning are easier to learn than those with less overlap.

Structure Mapping Theory is agnostic to the role of action schemas in accessing iconicity. Young children may be better able to access the iconicity of pantomimic signs than other types of iconicity because many features of the sign form correspond to the meaning (e.g., in the pantomimic sign BABY, the entire hand and body is available in the form and aligns with how a person holds a baby; Figure 2). Not only do the phonological features correspond to meaning (e.g., back and forth movement :: rocking a baby), but also facts about bodies and hands (e.g., having skin). Children may be less able to detect the iconicity of perceptual signs because the hands and locations of the sign map onto non-hand/body features of a referent (e.g., the hands in the perceptual sign BUTTERFLY represent the wings of a butterfly). In this way pantomimic signs depict a more proximal mapping of the form and referent, while perceptual signs depict a more distal mapping. By the same token, however, in pantomimic signs salient aspects of the referent may be missing in the sign form. For example, many semantic features of a baby (namely the baby itself) are not directly represented in the sign BABY, so despite being pantomimic it may be a more distal mapping. As such, Structure Mapping Theory may or may not predict an acquisition advantage for pantomimic signs.

To date all of the studies demonstrating an advantage of pantomimic signs have included only preschool-aged participants and have observed the advantage only in experimental settings. Unlike preschoolers, infants and toddlers may not have the first-hand motor experiences to offer such an advantage for pantomimic signs. Similarly, infants and toddlers may be less able to make use of distal mappings. Thompson et al. (2013) found stronger effects of degree of iconicity among older toddlers, a finding consistent with the idea that older children may have developed cognitive tools to better leverage the iconic form-meaning mapping (e.g., Gentner & Namy, 2006, though see Caselli & Pyers, 2017 for a failure to replicate). For these reasons, infants and toddlers may not be sensitive to iconicity type.

The iconicity of a word or sign may also be intertwined with the concreteness of the referent. Concreteness captures the degree to which a referent of a word is perceptible by the five senses and is one of the most robust predictors of vocabulary acquisition cross-linguistically (Braginsky, Yurovsky, Marchman, & Frank, 2016; Braginsky, Yurovsky, Marchman, & Frank, under review). Concrete words may be best learned when accompanied by first-hand experience with the referent (learning the word “apple” may leverage perceptual experience with an apple), while abstract words are learned via language (learning the word “cycle” requires using other linguistic information to discover the meaning; Vigliocco, Vinson, Lewis, & Garrett, 2004; Andrews, Vigliocco, & Vinson, 2009). Concreteness does not merely play a role in early language acquisition, its effects extend to adult language processing; concrete words are both easier for adults to learn (de Groot & Keijzer, 2000; Swingley & Humphrey, 2018) and remember than abstract words (e.g., Jessen, et al., 2000; Fleissbach et al., 2006 Bleasdale, 1987; Van Schie et al., 2005; Schwanenflugel, Harnishfeger, & Stowe, 1988).

In sign languages iconicity is related to, but not isomorphic with, concreteness (Perlman et al., 2018), and disentangling the two constructs is key to understanding how each could differently aid acquisition. For a sign to resemble its meaning (i.e., to be iconic), it generally must be possible to have a sensory experience of the meaning (i.e., concrete)1. However, just because a referent is concrete does not mean that the sign form will be highly iconic. For example, the concept FROG is concrete (mean rating of 5 on a scale of 1–5) but the ASL sign (see Figure 1) is low in iconicity (mean rating of 2.25 on a scale of 1–7, Caselli, Sevcikova Sehyr, Cohen-Goldberg, & Emmorey, 2016). Indeed, concreteness and iconicity affect adult sign language processing differently (Emmorey, Sevcikova Sehyr, Mideley, & Holcomb, 2016; Thompson, Vinson, Vigliocco, 2010). Further, concrete concepts might be more easily expressed by some types of iconicity than others. For example, though not exclusively the case, pantomimic signs may more commonly refer to actions than do perceptual signs, and thus pantomimic signs may not be as concrete as perceptual signs. On the other hand, pantomimic mappings may more readily encode tactile rather than other sensory features. Thus, even though degree of iconicity predicts spoken acquisition, when concreteness is controlled (Perry et al., 2015), it is unclear that it would do the same in a sign language where the two constructs are more highly correlated than is observed in spoken languages (although see Note 1 in Thompson et al., 2012 that suggests that degree of iconicity plays a role in acquisition above concreteness in a small sample of BSL learners). In addition, it is unclear whether type of iconicity and concreteness would independently shape acquisition.

Figure 1.

The concept “frog” is concrete, but the sign FROG is not iconic.

Finally, across different languages, the earliest learned words include words that are highly associated with infancy, or high in so-called “babiness” (Perry et al, 2015). In a mega-study using the WordBank of Macarthur-CDI reports of more than 30,000 children, babiness was among the strongest predictors of very early vocabulary development across ten languages (Braginsky et al, 2016; Braginksy et al, under review). It is not clear what it is about their association with babies that makes these words appear in children’s early vocabularies. One possibility is that words or concepts that are highly associated with babies appear frequently in babies’ environments. Alternatively, these words and concepts may be especially salient to babies. Although more work is needed to understand how babiness relates to vocabulary acquisition, the construct is correlated with iconicity in spoken language (Perry et al., 2015). That is, concepts that are evaluated as being related to babies are slightly more iconic than those that are not in spoken language. We may expect a similar relationship in a sign language, and as such babiness should be considered as a possible explanation for the effect of iconicity in acquisition.

Thus, the effects of iconicity might be an artifact of uncontrolled properties regarding the distribution of signs in the lexicon: some concepts might be more amenable to iconicity than others (e.g., concrete concepts), and some kinds of iconicity might be prevalent in the input (e.g., baby-related concepts might be expressed with highly iconic signs and/or more pantomimic signs). While there have been studies looking separately at how iconicity degree, iconicity type, concreteness, and babiness shape acquisition, no single study controls for and examines their effects together. Because these factors may be correlated to some degree, we cannot draw conclusions about the effects of each individual factor without controlling for them all together. With the largest available dataset of early productive ASL vocabulary development, we explored inter-relationships between iconicity, concreteness, and babiness and asked whether each independently contributes to early vocabulary acquisition.

In sum, there is mounting evidence that children learn signs that are iconic more easily than signs that have limited or no iconic motivation. It is less clear though what drives this effect. Iconicity is not a unidimensional construct, and can be broken down into different types (e.g., pantomimic or perceptual in the case of sign languages), and children may be able to leverage some types of iconic mappings better than other types. While there are studies showing that type of iconicity affects vocabulary acquisition among infants and toddlers and others showing that degree of iconicity affects vocabulary learning and use among preschoolers, no study to date has examined the relationship between type and degree of iconicity and whether these two variables independently contribute to vocabulary acquisition during the earliest years of life. The effects of degree of iconicity may be driven primarily by one type of iconic sign. Alternatively the observed effects of type of iconicity may be driven by the fact that some types are more iconic than others. In this exploratory study, we asked whether type and degree of iconicity have independent effects vocabulary acquisition, while controlling for potentially correlated variables.

Methods

The current study used the same dataset that was reported in Caselli and Pyers (2017; https://osf.io/uane6/). Caselli and Pyers (2017) examined the effect of degree of iconicity, neighborhood density, and frequency in children’s early vocabularies using an existing dataset of parental reports from 58 deaf children from the original ASL-CDI norming study (Anderson & Reilly, 2002). Parents read English glosses of 537 signs, and indicated whether or not their child could produce each sign. Parents were told to indicate that a child knew the sign even if the child did not use the “correct” adult sign (e.g., used a dialectical variation or produced the sign with a phonological error). The average age of the children was 24 months (Mdn = 26; range 8–35 months). All children had at least one deaf parent, and 55 had two deaf parents. From the 332 items reported in Caselli and Pyers (2017), we excluded seven body part signs because data was only available for a handful of participants and because these signs generally involve pointing at the body part and it is unclear whether these items should be treated as unique lexical items or as pronouns, for example. We also excluded 80 items for which we did not have babiness ratings. The remaining 245 signs included 165 nouns, 38 verbs, 31 adjectives, nine adverbs, and two number signs. Videos of the signs are available at http://asl-lex.org/.

Because this study examined de-identified, existing data, the Institutional Review Boards at Boston University and Wellesley College determined this study to be “exempt” from human subjects protections review.

Measures

Degree of Iconicity

Degree of iconicity was taken from ASL-LEX, a lexical database of ASL (Caselli et al., 2016), and was the same measure that was reported in Caselli and Pyers (2017). Degree of iconicity was collected by asking roughly 30 hearing non-signers to rate how much each sign looks like its English translation on a scale of 1 to 7. The z-transformed values reported in ASLLEX were used here.

Iconicity Type

Signs that had a degree of iconicity below a 4 were considered “arbitrary” (n = 123). The remaining signs were coded as pantomimic (n = 40), perceptual (n = 39), or both (n = 43). Pantomimic signs were those in which the signer’s body and/or hands were used to represent the analogous body parts of the referent (e.g., in EAR, the signer’s ear represents the referent’s ear) or body parts related to the referent (e.g., in BABY, the signer’s body represents a person holding a baby, not the baby’s body). The body of, or related to, the referent could be human or another human-like body (e.g., a statue of a person, a robot, an animal). Perceptual signs were those in which the signer’s body and/or hands were used to represent any feature of a referent (e.g., its shape, movement, spatial location) other than an analogous body part or hand. To aid in making these determinations, the raters considered each of the phonological parameters (handshape, location, and movement) and determined whether those parameters were iconically motivated and if so which category they belonged to. If a particular sign had some pantomimic mappings and some perceptual mappings, then the “both” category was used. If the rater was on the fence as to whether or not to use the “both” category, the “both” category was avoided. Pointing (regardless of the handshape used to point) was taken as a way of highlighting iconicity and not as intrinsically iconically motivated. For example, the sign ARM is produced by passing the hand down the length of the arm. The arm location was taken as pantomimic (the body location used to produce the sign is the same as the body part in the referent), and the hand pointing toward the arm was taken as a way of magnifying this iconicity. Examples of each can be found in Figure 2. All of the iconicity type ratings are available at https://osf.io/fju7c/ and in the supplementary material. Iconicity type was coded by the two authors, who are both hearing, native ASL users. Inter-rater reliability was high (κ = 0.75, p < 0.001). Iconicity type was subsequently coded by two additional signers who were naïve to the study purpose, and interrater reliability among all four raters was also high (Fleiss’ κ = .693, p < 0.001). For 94% of signs, the iconicity type included in the analysis was the majority rating across raters. For the remaining seven items (EARRING, HAPPY, PRETTY, SCARED, SLEEP, TEAR, and TIRED), we used the first author’s category judgments. However, we confirmed that all of our analyses are qualitatively the same excluding the seven items.

Babiness

Babiness ratings were taken from Perry, et al. (2015). These were ratings made by 291 people who evaluated words on the English version of the CDI according to how much they associated the word with babies on a scale of 1 to 10. The English words were matched to the ASL signs by either an identical (n = 221) or close match to the ASL gloss (i.e., BUNNY and RABBIT; n = 24). A megastudy of vocabulary acquisition across ten languages used the same babiness ratings from English and found the construct to be among the strongest predictors of word acquisition cross-linguistically (Braginsky et al., 2016, Braginksy et al, under review). Out of concern that English ratings may not be appropriate for examining ASL acquisition and may interact with degree and type of iconicity in ways we could not foresee, we also collected babiness ratings from two deaf mothers who were fluent ASL signers, and took the average of their ratings. The ASL-based ratings and the English translation ratings were correlated (r = 0.6, p < 0.01).

Concreteness

We used concreteness ratings from Brysbaert, Warriner, and Kuperman (2014) via Perry, et al. (2015) for the 245 items for which we had babiness ratings. Brysbaert et al. (2014) asked raters to use a 5-point scale from abstract (1) to concrete (5). Concreteness was defined as follows:

“A concrete word comes with a higher rating and refers to something that exists in reality; you can have immediate experience of it through your senses (smelling, tasting, touching, hearing, seeing) and the actions you do. The easiest way to explain a word is by pointing to it or by demonstrating it (e.g. To explain ‘sweet’ you could have someone eat sugar; To explain ‘jump’ you could simply jump up and down or show people a movie clip about someone jumping up and down; To explain ‘couch’, you could point to a couch or show a picture of a couch).”

At the other end of the scale, an abstract word was defined as:

“An abstract word comes with a lower rating and refers to something you cannot experience directly through your senses or actions. Its meaning depends on language. The easiest way to explain it is by using other words (e.g. There is no simple way to demonstrate ‘justice’; but we can explain the meaning of the word by using other words that capture parts of its meaning).”

While these ratings are based on English translations of the signs and not ASL signs themselves, concreteness ratings are highly correlated cross-linguistically (e.g., Tokowicz, Kroll, de Groot, & van Hell, 2002 found English and Dutch concreteness ratings to have a correlation of 0.94) and English concreteness ratings have been used cross-linguistically in several studies of signed languages (Perlman, Little, Thompson, & Thompson, 2018; Emmorey, McCullough, & Weisberg, 2015; Thompson, Vinson, Vigliocco, 2010; Vinson, Thompson, Skinner, Vigliocco, 2015).

Neighborhood Density2:

Phonological neighborhood density was taken from ASL-LEX. It was defined as the number of signs from the 994 signs in ASL-LEX that share at least four of five phonological properties (selected fingers, flexion, path movement, major location, and sign type, Caselli et al., 2016).

Frequency

Subjective frequency was also taken from ASL-LEX. This measure was collected by asking roughly 30 deaf adult signers to rate on a scale of 1 to 7 how often they use each sign in everyday conversation. The z-transformed values reported in ASL-LEX were used here.

All continuous variables were z-transformed, except degree of iconicity and subjective frequency, which were already z-transformed in ASL-LEX.

Results

Relationships among lexical variables

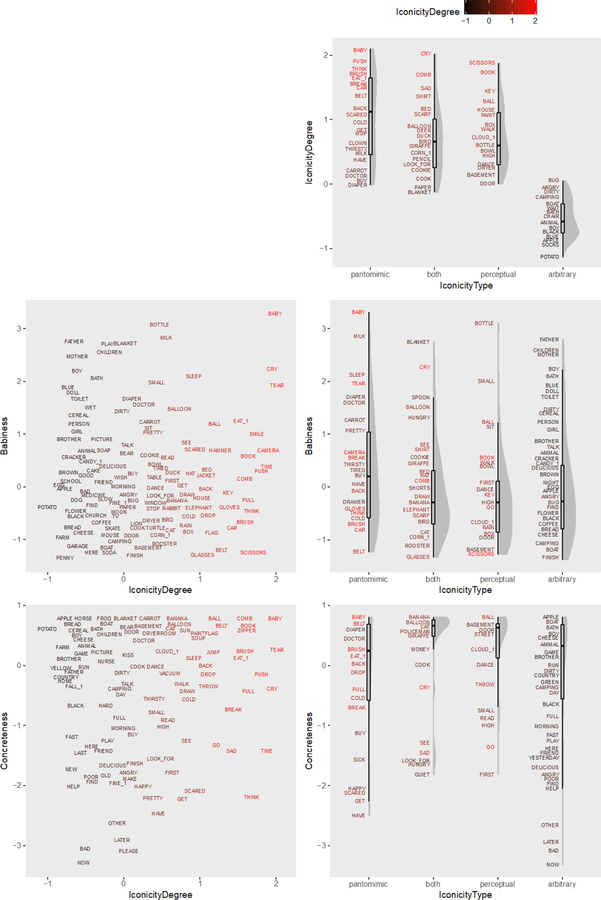

A one-way ANOVA indicated that degree of iconicity differed significantly by iconicity type (F(3, 241) = 198.5, p < 0.001). A Tukey HSD test showed that pantomimic signs were more iconic than both signs (p < 0.01) and more iconic than perceptual signs (p < 0.01). There was no difference between both and perceptual signs (p = 0.998). By definition, the arbitrary signs were less iconic than all other categories (all p’s < 0.01; see Figure 3). Babiness was not correlated with degree of iconicity (see Table 1), and there was no statistically significant difference in babiness by iconicity type (F(3, 241) = 2.274, p = 0.08). Tukey’s HSD indicated that pantomimic signs were numerically, but not significantly, more babyish than perceptual signs (p = 0.069); the other pairwise comparisons were not significant (all p’s > 0.16; see Figure 3). Concreteness was not correlated with degree of iconicity (see Table 1), but concreteness did differ as a function of iconicity type (F(3, 241) = 3.588, p = 0.01); Tukey’s HSD indicated that both signs were numerically, but not significantly, more concrete than arbitrary signs (p = 0.06); the other pairwise comparisons were not significant (all p’s > 0.1; see Figure 3). Of the 40 pantomimic signs 30% were verbs (50% nouns), and of the 39 perceptual signs 23% were verbs (69% nouns).

Figure 3.

The relationships between degree of iconicity, type of iconicity, babiness, and concreteness. On the right, the grey shapes in the violin plots indicate the density of the distribution of each type of iconic sign. The hinges of the boxplots indicate the 25th and 75 percentiles, and the whiskers indicate 1.5 times the interquartile range. Note that for the sake of readability only a subset of items were labeled here. The labels are English glosses from ASLLEX. Videos of each sign can be found at http://asl-lex.org/. Figures were plotted using the library ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016), and the geom_flat_violin function (Robinson, 2015).

Table 1.

Means (M), standard deviations (SD), and Pearson correlations (r) with confidence intervals of all untransformed lexical variables

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Iconicity | 0.14 | 0.81 | ||||

| 2. Babiness | 3.65 | 1.91 | .03 [−.10, .15] | |||

| 3. Concreteness | 4.31 | 0.86 | .07[−.05, .20] | −.06 [−.18,.07] |

||

| 4. SignFrequency | 0.26 | 0.63 | −.20** [−.32, −.08] |

.24** [.11, .35] |

−.36** [−.46, −.24] |

|

| 5. NeighborhoodDensity | 34.15 | 27.29 |

.14* [.02, .26] |

.14* [.01, .26] |

.01 [−.11, .14] |

.15* [.03, .27] |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01.

Modeling Procedure

Using the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2014) in R, we used mixed-effects logistic regressions to examine the factors that predict productive vocabulary acquisition. This type of model allows one to account for item-specific and participant-specific variability at once. The dependent variable was acquisition (the child can = 1 or cannot produce the sign = 0). The predictor variables were iconicity type, iconicity degree, babiness, and concreteness. We also controlled for fixed effects of neighborhood density, subjective frequency, and age and random effects of participant and item. Out of concern that variables in this model were collinear, a log likelihood test was used to compare the full model to a model excluding each variable of interest in turn to determine whether including the variable was justified. This procedure allows the modeler to determine whether the variable in question has an effect above and beyond other possibly correlated variables (e.g., confirm effects of type of iconicity above and beyond degree of iconicity and vice versa). Because collinearity can make the magnitude and direction of effects difficult to interpret, we examined the effect of each variable of interest in a bare model that included only that variable plus random effects of participants and items.

Model Results

We confirmed that the results reported in Caselli and Pyers (2017) hold in this smaller set of items; there were positive effects of age, degree of iconicity, subjective frequency, and neighborhood density on acquisition. Iconicity type did not significantly improve the fit of the model (χ(3) = 5.23, p = .16). In other words, it did not predict enough variance to justify including it in the model. See Table 2 for the results of a model including (Model 1) and excluding iconicity type (Model 2). Because these analyses are exploratory, we report the pairwise comparisons here, but the strength of evidence for the following results is weak and should be taken with appropriate caution. Only one of the pairwise comparisons was significant (both signs were acquired significantly earlier than perceptual signs). We had speculated that pantomimic signs might be acquired earlier than perceptual signs, but even numerically the difference between the groups was negligible (see Figure 4). Because the signs in the both category are also pantomimic, we ran the same analysis but collapsed the both and pantomimic categories. There results were qualitatively the same: iconicity type with collapsed categories did not significantly improve the fit of the model (χ(2) = 2.83, p = .24), and there was no significant difference between this collapsed type of iconicity and arbitrary or perceptual signs.

Table 2.

Acquisition in productive ASL vocabulary. The comparison level of Iconicity Type is pantomimic.

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratios | CI | P | Odds Ratios | CI | P | Odds Ratios | CI | P | Odds Ratios | CI | P | |

| (Intercept) | 0.37 | 0.16 – 0.85 | 0.019 | 0.50 | 0.32 – 0.77 | 0.002 | 0.62 | 0.32 – 1.19 | 0.152 | 0.45 | 0.18 – 1.13 | 0.088 |

| Both | 1.82 | 0.84 – 3.97 | 0.130 | 1.55 | 0.72 – 3.33 | 0.265 | 2.01 | 0.87 – 4.68 | 0.103 | |||

| Arbitrary | 1.51 | 0.55 – 4.14 | 0.422 | 0.70 | 0.37 – 1.32 | 0.270 | 1.11 | 0.37 – 3.34 | 0.852 | |||

| Perceptual | 0.82 | 0.37 – 1.83 | 0.626 | 0.70 | 0.31 – 1.54 | 0.373 | 0.85 | 0.36 – 2.01 | 0.713 | |||

| Iconicity Degree | 1.65 | 0.99 – 2.74 | 0.053 | 1.42 | 1.07 – 1.88 | 0.015 | 1.41 | 0.81 – 2.46 | 0.226 | |||

| Concreteness | 1.98 | 1.56 – 2.51 | <0.001 | 1.97 | 1.56 – 2.50 | <0.001 | 1.94 | 1.52 – 2.46 | <0.001 | |||

| Babiness | 1.55 | 1.23 – 1.95 | <0.001 | 1.55 | 1.23 – 1.95 | <0.001 | 1.54 | 1.22 – 1.95 | <0.001 | |||

| Sign Frequency | 2.20 | 1.48 – 3.27 | <0.001 | 2.13 | 1.43 – 3.17 | <0.001 | 2.07 | 1.39 – 3.07 | <0.001 | 1.72 | 1.16 – 2.55 | 0.007 |

| Neighborhood Density | 1.27 | 1.02 – 1.60 | 0.034 | 1.25 | 1.00 – 1.57 | 0.053 | 1.32 | 1.05 – 1.65 | 0.016 | 1.40 | 1.09 – 1.79 | 0.007 |

| Age | 10.68 | 7.39 – 15.43 | <0.001 | 10.68 | 7.39 – 15.43 | <0.001 | 10.68 | 7.39 – 15.44 | <0.001 | 10.65 | 7.37 – 15.39 | <0.001 |

| Random Effects | ||||||||||||

| σ2 | 3.29 | 3.29 | 3.29 | 3.29 | ||||||||

| ∞ | 2.82 Sign | 2.88 Sign | 2.87 Sign | 2.82 Sign | ||||||||

| 1.88 Subject Number | 1.88 Subject Number | 1.88 Subject Number | 1.88 Subject Number | |||||||||

| ICC | 0.35 Sign | 0.36 Sign | 0.36 Sign | 0.40 Sign | ||||||||

| 0.24 Subject Number | 0.23 Subject Number | 0.23 Subject Number | 0.22 Subject Number | |||||||||

| Observations | 14198 | 14198 | 14198 | 14198 | ||||||||

| Marginal R2 / Conditional R2 | 0.450 / 0.774 | 0.446 / 0.774 | 0.447 / 0.774 | 0.410 / 0.774 | ||||||||

| AIC | 10339.576 | 10338.801 | 10341.526 | 10381.519 | ||||||||

Figure 4.

The percentage of children who have acquired each sign as a function of the sign’s type of iconicity. The grey shapes indicate the density of the distribution. The hinges of the boxplots indicate the 25th and 75 percentiles, and the whiskers indicate 1.5 times the interquartile range. Note that for the sake of readability only a subset of items were labeled here. The labels are English glosses from ASL-LEX. Videos of each sign can be found at http://asl-lex.org/ Figures were plotted using the library ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016), and the geom_flat_violin function (Robinson, 2015).

Because pantomimic signs are significantly more iconic than other signs, it is possible that effects of iconicity degree on children’s early vocabularies are primarily driven by the disproportionate number of highly iconic signs that are also pantomimic. If true, then there may be no effect of iconicity type above and beyond degree because all of the variance associated with pantomimic signs is soaked up by degree of iconicity. To examine the possibility that effects of degree of iconicity might really reflect differences in type of iconicity, we ran a model that included type but not degree of iconicity (Model 3). This model had a numerically but not significantly poorer fit than a model excluding both type and degree of iconicity (χ(3) = 7.57, p = .06), indicating that including type of iconicity may not be justified even when degree of iconicity is not included in the analysis. As such, we again warn the reader to interpret the following pairwise comparisons with appropriate caution. There was no acquisition advantage of pantomimic signs, and there was a significant difference between both signs and perceptual signs (β=0.80, SE=0.39, z = 2.04, p = 0.04) as well as both signs and arbitrary signs (β=0.80, SE=0.31, z = 2.52, p = 0.01).

There was a positive effect of babiness on acquisition whereby words that were more associated with babies were also more likely to be acquired. There was also a positive effect of concreteness on acquisition; children were more likely to have acquired concrete signs. Model comparison confirmed that including babiness, concreteness, degree of iconicity, frequency, neighborhood density, and age were justified, as each had an effect above and beyond all other variables (all p’s < 0.05).

Because several of the factors were collinear, we confirmed the direction and magnitude of each effect by running a model with only that fixed variable (plus random effects of subjects and items). The effects were qualitatively the same except for type of iconicity: there was a significant difference between both signs and arbitrary signs (β=0.86, SE=0.35, z = 2.45, p = 0.01) but not between both signs and perceptual signs (β=−0.62, SE=0.44, z = −1.41, p = 0.16). There was again no advantage for pantomimic signs.

Because it is not clear that subjective frequency ratings based on adult conversations are the ideal measure of frequency in the input children receive, we compared this to a few other measures of frequency. These included log transformed subjective frequency, log frequency from the American Nation Corpus (Reppen, Ide, & Suderman, 2005 via Perry et al., 2015), and frequency in child-directed English from the CHILDES corpus (Li & Shirai, 2000; MacWhinney, 2000). None significantly improved the model fit over the z-transformed subjective frequency ratings from ASL-LEX.

Ratings of concreteness and babiness based on English words may be inappropriate in the analysis of ASL signs. Therefore we confirmed the effects of iconicity type and degree in a model excluding concreteness and babiness (see Table 2, Model 4). This model had a significantly poorer fit (χ(2) = 45.9, p < 0.01), confirming that these constructs based on English ratings accounted for a significant amount of the variance in ASL vocabulary acquisition. There was again no effect of iconicity type, and the effect of iconicity degree was no longer significant. We also examined the effects of babiness using ratings of ASL signs from two deaf mothers of infants. We redid all of the analyses using the ASL babiness measure instead of the English one and all of the results were qualitatively the same.

The items on the ASL-CDI are more frequent, more iconic, and have more phonological neighbors than the rest of the signs in the ASL lexicon (Caselli & Pyers, 2017). Further, concreteness and iconicity were not correlated among the items on the ASL-CDI, despite the fact that they are correlated in the larger lexicon. Therefore the effects of iconicity and concreteness on children’s early signed vocabularies may arise not because children are sensitive to these lexical properties but because of the idiosyncratic properties of the ASL-CDI dataset. To rule out this possibility, we conducted a Monte Carlo analysis to compare the distribution of pantomimic signs and degree of iconicity in children’s actual vocabularies relative to the distributions in vocabularies randomly selected from the CDI. For each participant, we randomly selected without replacement as many items as the child knew from the entire set of items on the CDI, and repeated this 1,000 times. We calculated the proportion of pantomimic signs and the average degree of iconicity of these randomly generated vocabularies (see Figure 5). If pantomimic signs and highly iconic signs are not overrepresented in children’s vocabularies, then based on chance we would expect the proportion of pantomimic signs and average iconicity in children’s actual vocabularies to fall above the 95th percentile of the randomly generated vocabularies to be about 5% (three children). We observe such a pattern for type of iconicity: only five children had more pantomimic signs in their vocabulary than appear in the randomly generated vocabularies, this was not different from chance (8%; z = 9.40, p = 0.34). However, for degree of iconicity, nineteen of the observed iconicity ratings fall above the 95th percentile, far more than expected by chance (33%; z = 0.96, p < 0.001)

Figure 5.

Observed versus randomly generated estimates of proportion of pantomimic signs, degree of iconicity, concreteness, and babiness. Red bars indicate the 5th and 95th percentile of the proportion (pantomimic signs) or average (iconicity degree, concreteness, and babiness) in 1,000 randomly generated vocabularies of a given size, and black dots indicate the observed proportion or mean for each child.

Discussion

In our exploration of the factors that may account for the effects of degree of iconicity on vocabulary development among signing infants and toddlers, we found that degree of iconicity, concreteness, and babiness, but not type of iconicity made independent contributions to expressive vocabulary development. This pattern of results shows that children are sensitive to the degree of iconicity, and that the effect of degree of iconicity on acquisition cannot be explained by any of these potentially related factors. We discuss each of these in turn, and then consider implications for theories of iconicity in language acquisition.

While we replicated the effect of degree of iconicity on sign acquisition, we did not find that infants and toddlers were more likely to know pantomimic signs than other types of iconic signs when degree of iconicity was controlled. Moreover, even in a model excluding degree of iconicity, children were not more likely to know pantomimic signs than other types of signs. If anything, in one post hoc analysis the both signs were more likely to be acquired than perceptual signs, and there was again no advantage for pantomimic signs. Because including iconicity type in the model was not justified, this result would need to be replicated for us to draw strong conclusions. This pattern of findings speaks against an embodied cognition account of the role of iconicity in early vocabulary development. The results here differ from the observed advantage in pantomimic signs among preschoolers learning and producing gestures and signs in experimental settings (e.g., Ortega et al., 2017). One possible reason for the difference between our results and those of previous studies is that the children in our sample were significantly younger. Accordingly, these infants and toddlers may not yet have the first-hand motor experience necessary to build a robust action schema that would allow them to easily make the pantomimic mapping between form and meaning. Once children gain motor experience, perhaps by the preschool years, they may use embodiment to acquire new pantomimic signs better than signs with perceptual elements. In this way, embodiment could shape how people use and learn signs at later stages of development, even if its effects are absent in the first years of language acquisition.

Interestingly, the literature on early symbolic development has robustly demonstrated a non-preference for pantomimic gestures among young 2–3 year olds, in favor of gestures that also encoded the perceptual features of the object (e.g., cupping the hand to gesture a shovel digging instead of using a pantomimic gesture of holding a shovel while digging; Overton & Jackson, 1973). The argument here is that young children do not have the cognitive abilities to represent the invisible objects in their gestures and need to use a body part to represent the object to ease the cognitive load (Boyatzis & Watson, 1993). As their symbolic abilities develop, they are better able to produce pantomimic gestures. Many of the pantomimic signs in this dataset are of the sort that have an invisible referent (e.g., BABY, BRUSH; Figures 2 and 6). In as much as manual gestures and manual lexical signs share properties, growing symbolic reasoning abilities may account for the patterns observed. It may be the case that we found no advantage for pantomimic signs because the children studied here were too young and did not have the necessary cognitive capacity to represent an invisible object. A Structure Mapping Theory of iconicity in acquisition corresponds with the cognitive accounts for the developmental capacity to represent an invisible object. The degree of alignment between form and meaning relates both to the number of phonological features of the sign form that are semantically motivated and to the number of semantic features that appear in the sign form. For example all of the phonological features of the sign BABY are semantically motivated, but not all of the semantic features are represented in the sign form (crucially, the baby). Pantomimic signs with invisible referents have less complete alignment between form and meaning as they omit salient aspects of the semantic representation. We expect a Structure Mapping Theory of iconicity would predict that signs should be easiest to learn when (1) many phonological features correspond to semantic features and (2) many semantic features correspond to phonological features. We await more sophisticated measures of overlap between sign form and meaning to test these predictions.

Figure 6.

Many aspects of the form map to aspects of meaning in the pantomimic sign BRUSH. It also has an invisible referent (the brush itself is not represented in the form).

The pantomimic signs on the ASL-CDI were more iconic than other types of signs, which has critical implications for interpreting studies of type and degree of iconicity. Demonstrated effects of iconicity type on acquisition (Tolar et al, 2008; Ortega et al., 2017) may arise not because of the kind of mapping between form and meaning but because pantomimic signs generally have a higher degree of iconicity, a variable not considered in those previous studies. According to a Structure Mapping Theory of iconicity, the relationship between degree and type of iconicity might exist because when using the body to represent the body, there is a high level of overlap between the sign form and meaning. Alternatively, an embodied theory of iconicity might predict that pantomimic signs are rated more iconic exactly because they are embodied. The relationship between type and degree of iconicity cannot be explained by concreteness: pantomimic and perceptual signs did not differ in concreteness.

However, the fact that pantomimic signs were more iconic than other signs does not indicate that pantomimic signs drive the effect of degree of iconicity on acquisition. Not only does type of iconicity not predict acquisition above and beyond degree of iconicity, it does not predict acquisition in a model excluding degree of iconicity entirely. The latter test is important because the relationship between type and degree of iconicity could mean that the effects of iconicity degree on acquisition could have soaked up variance that was in fact associated with pantomimic signs. The fact that we do not see an advantage of pantomimic signs even when iconicity degree is excluded from the model altogether confirms that the effect of iconicity on acquisition is driven by degree not type of iconicity. As such, an embodiment account that draws on the importance of motor representations and action schemas in learning cannot explain the effects of degree of iconicity on acquisition.

Structure Mapping Theory may provide a better account of the effect of iconicity on sign acquisition in the first years of life. The effect of degree of iconicity on acquisition may arise as a consequence of the degree of alignment between the semantic features and the phonological form. This is compatible with a lack of advantage for pantomimic signs, which would not necessarily be privileged in a Structure Mapping Theory of iconicity. If any category of iconicity was advantaged in our data set, it was the both category where pantomimic and perceptual information is combined in a linguistic form, perhaps capturing a richer iconic representation of the referent, although more work is needed to fully understand this pattern.

While we conducted these analyses with one of the largest sets of sign language acquisition data available, compared to many other studies of language acquisition this sample is small. More work is needed to confirm the null effects of iconicity type, and to confirm whether the patterns observed here hold across different sign languages. It is worth noting, that the categories of iconicity type that we examined here, while used commonly in the early gesture and sign literature are neither exhaustive nor as fine-grained as have been proposed by others. Taub (2000) outlines a rich set of iconic mappings that includes tracing and handling as well as more abstract metaphorical iconic mappings. Children may certainly attend to other, currently unanalyzed, types of iconicity.

As has been robustly observed in the acquisition of vocabulary across many languages, the degree to which a referent can be perceived by one of the senses is a significant predictor of early vocabulary development. Among the items on the ASL-CDI, concreteness and degree of iconicity were not correlated, and both had independent effects on acquisition. Yet, visualizations of the data (see Figure 3) bore out the idea that concepts that are not concrete are almost never highly iconic (i.e., few signs appear in the bottom right quadrant of the scatterplot).3 There were many signs that were concrete but whose sign forms were not iconically motivated. This pattern could arise because some sensory features (e.g., color) may be difficult to convey with the hands alone (though pointing to body parts that match the color, like eyebrows or lips, is a possible iconic mapping, e.g. the ASL sign RED is produced near the lips). It may simply be that, although it is possible to have a sensory experience of a concept, an arbitrary mapping may be just as useful as an iconic one in representing that concept. Indeed, the majority of signs in the ASL lexicon (~70% of the signs in ASL-LEX) have low iconicity ratings (i.e., below the median). The lack of a relationship between iconicity and concreteness may also be an artifact of the signs in the ASL-CDI, which are more iconic than the rest of the ASL-LEX lexicon (Caselli & Pyers, 2017). The two are also correlated in BSL and in a larger sample of 893 items from the ASL-LEX database (r = approximately 0.2; Perlman et al., 2018). Thus, the weak relationship between iconicity and concreteness in child language may arise because there are few items that are highly iconic but not concrete (Figure 3 lower right quadrant), and many items that are highly concrete but not iconic (Figure 3 upper left quadrant). Nevertheless what is clear, is that, as is the case cross-linguistically, highly concrete items were more likely to appear in children’s early productive vocabularies, and this was true regardless of how iconic the items were and vice versa.

The independent effect of babiness on early sign vocabulary development is in keeping with observations from spoken languages. Crucially, the effect of babiness does not explain the effect of degree of iconicity on children’s expressive vocabulary. Unlike other datasets which indicate a weak correlation between iconicity and babiness in spoken language (Perry et al., 2015), we observed no correlation with degree of iconicity in our dataset. There was a numerical, albeit non-significant difference in babiness as a function of iconicity type (pantomimic signs were numerically more related to babies than other types of iconicity). This numerical pattern mirrors patterns of iconicity type present in child-directed signing. For example, in an elicited task, adults prefer pantomimic signs in child-directed conversations despite exhibiting a dispreference for pantomimic signs in adult-directed signing (Ortega et al., 2017). More work is needed to determine exactly what this measure captures (e.g., frequency in infant-directed signing that is not captured by frequency estimates based on adult conversations, presence in babies’ environments, importance to babies). Nevertheless, our data allow us to rule babiness out as an explanation for the effect of iconicity in early acquisition.

Beyond a growing ability to engage in structure mapping during language learning, what viable alternative, outside the factors considered here, could explain children’s sensitivity to iconicity? One possibility is that children know more iconic signs not because they themselves are sensitive to iconicity, but because of the way iconic signs are used in child-directed signing. Studies of child-directed speech have highlighted the prevalence of iconic words in the input to children as opposed to adults (Perry et al., 2017). The effect may be quite different in sign language where there is robust iconicity to which adults are quite sensitive. Signing parents prefer pantomimic alternatives when talking to children as opposed to adults (Ortega et al., 2017) and they make more child-friendly prosodic modifications to signs directed to children, especially in ostensive contexts, than to adults (Perniss et al., 2017). These modifications seem to not only exaggerate the iconic elements of the sign, but intensify the child-directed characteristics of the language possibly making it more salient to children. In addition, parents may point out the correspondence between phonological form and meaning. Extended conversations about vocabulary items, especially those that draw attention to phonological forms, may be responsible for their advantage in early acquisition. We await more systematic measures of child-directed signing in naturalistic settings to address this question. However, it is unclear how much the relationship between iconicity and early vocabulary development will reflect patterns of iconicity in child-directed signing: despite a reported preference of pantomimic signs in child-directed signing, pantomimic signs were not overrepresented in the early productive vocabularies of children in this dataset.

The current study focused on children learning a sign language from birth, which is alarmingly rare among deaf children. The vast majority of deaf children are at risk for language deprivation because they have reduced access to speech sounds and their parents do not know sign language (Hall & Glickman, 2018). Language-deprived children begin learning language later in development when they may have different cognitive resources and life experiences to bring to bear on the language acquisition processes. These resources may make these children better equipped to make better use of iconicity and the ‘babiness’ of signs may no longer matter. More work is needed to understand this sadly typical case of sign language acquisition.

Though children seem to make use of iconicity to learn new words, they appear to make use of degree of iconicity rather than type of iconicity. We found that pantomimic signs were not overrepresented in native signing children’s productive vocabularies, even though pantomimic signs were more highly iconic and perhaps more likely to be associated with babies. This pattern suggests that motor representations are insufficient to drive the effects of iconicity on early language acquisition. Iconicity, regardless of type, may be a useful tool for children to link form and meaning to acquire new words.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Diane Anderson, Judy Reilly, and Michael Frank for sharing and digitizing the ASLCDI reports, and to Cindy O’Grady Farnady the use of her likeness. Thanks also to participants, and to Amy Lieberman and Karen Emmorey for feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript. In addition, we thank three anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Deafness And Other Communication Disorders of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21DC016104. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work is also supported by a James S. McDonnell Foundation Award to Jennie Pyers, and National Science Foundation grant BCS 1625793 to Naomi Caselli.

Footnotes

Data are available at: https://osf.io/uane6/ and https://osf.io/fju7c/

Sometimes iconicity picks out the sensory experience not of the direct referent, but of a symbol associated with that referent. For example, the iconic motivation in the sign SWITZERLAND is the cross on the flag and does not represent a direct sensory experience of the country of Switzerland.

Neighborhood density was calculated using the best available phonological coding, though this coding is not a complete description of each sign. As such, signs may be neighbors in this calculation, yet not be true minimal pairs.

Some exceptions were a handful of mental and emotional terms where the signer might use a facial expression that is associated with the feeling, and a location near the body (SCARED) or head (SAD, THINK).

Contributor Information

Naomi K. Caselli, Boston University

Jennie Pyers, Wellesley University.

References

- Anderson D, & Reilly J (2002). The MacArthur communicative development inventory: Normative data for American Sign Language. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 7(2), 83–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews M, Vigliocco G, & Vinson D (2009). Integrating experiential and distributional data to learn semantic representations. Psychological Review, 116(3), 463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsalou LW (1999). Perceptions of perceptual symbols. Behavioral and brain sciences, 22(4), 637–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsalou LW (2009). Simulation, situated conceptualization, and prediction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 364(1521), 1281–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S, Christensen RHB, Singmann H, … & Grothendieck G (2014). Package ‘lme4’. R foundation for statistical computing Vienna, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Bleasdale FA (1987). Concreteness-dependent associative priming: Separate lexical organization for concrete and abstract words. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 13(4), 582. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis CJ, & Watson MW (1993). Preschool children’s symbolic representation of objects through gestures. Child Development, 64(3), 729–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braginsky M, Yurovsky D, Marchman VA, Frank MC (2016). From uh-oh to tomorrow: Predicting age of acquisition for early words across languages. Proceedings of the 38th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society Austin, TX: Cognitive Science Society. [Google Scholar]

- Braginsky M, Yurovsky D, Marchman V, & Frank MC (under review). Consistency and variability in word learning across languages 10.31234/osf.io/cg6ah [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brysbaert M, Warriner AB, & Kuperman V (2014). Concreteness ratings for 40 thousand generally known English word lemmas. Behavior Research Methods, 46(3), 904–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caselli NK, & Pyers JE (2017). The road to language learning is not entirely iconic: Iconicity, neighborhood density, and frequency facilitate acquisition of sign language. Psychological Science, 28(7), 979–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caselli N, Sevcikova Sehyr Z, Cohen-Goldberg A, & Emmorey K (2016). ASL-LEX: A lexical database for American Sign Language. Behavior Research Methods, 9(2), 784–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook SW, & Tanenhaus MK (2009). Embodied communication: Speakers’ gestures affect listeners’ actions. Cognition, 113(1), 98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot AM, & Keijzer R (2000). What is hard to learn is easy to forget: The roles of word concreteness, cognate status, and word frequency in foreign language vocabulary learning and forgetting. Language Learning, 50(1), 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- DeLoache JS, Kolstad V, & Anderson KN (1991). Physical similarity and young children’s understanding of scale models. Child Development, 62(1), 111–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingemanse M, Blasi DE, Lupyan G, Christiansen MH, & Monaghan P (2015). Arbitrariness, iconicity, and systematicity in language. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19(10), 603–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigsti IM (2013). A review of embodiment in autism spectrum disorders. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmorey K (2014). Iconicity as structure mapping. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 369(1651), 20130301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmorey K, Sevcikova Sehyr Z, Midgley KJ, & Holcomb PJ (2016). Neurophysiological correlates of frequency, concreteness, and iconicity in American Sign Language. Poster presented at the 23rd Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Fliessbach K, Weis S, Klaver P, Elger CE, & Weber B (2006). The effect of word concreteness on recognition memory. NeuroImage, 32(3), 1413–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frishberg N (1975). Arbitrariness and iconicity: Historical change in American Sign Language. Language, 696–719.

- Gentner D (1983). Structure-mapping: A theoretical framework for analogy. Cognitive Science, 7(2), 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Gentner D & Ratterman MJ (1991). Language and the career of similarity. In Gelman SA & Byrnes JP (Eds.), Perspectives on thought and language: Interrelations in development, (pp. 225–277). London: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall W, & Glickman N (Eds.). (2018). Language deprivation and deaf mental health Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jessen F, Heun R, Erb M, Granath DO, Klose U, Papassotiropoulos A, & Grodd W (2000). The concreteness effect: Evidence for dual coding and context availability. Brain and language, 74(1), 103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, & Shirai Y (2000). The acquisition of lexical and grammatical aspect Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney B (2000). The CHILDES project (3rd Edition). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Magid R, & Pyers JE (2017). “I use it when I see it”: The role of development and experience in Deaf and hearing children’s understanding of iconic gesture. Cognition, 162, 73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massaro DW, & Perlman M (2017). Quantifying iconicity’s contribution during language acquisition: Implications for vocabulary learning. Frontiers in Communication, 2, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Meier RP, Mauk CE, Cheek A, & Moreland CJ (2008). The form of children’s early signs: Iconic or motoric determinants? Language Learning and Development, 4(1), 63–98. [Google Scholar]

- Namy LL (2008). Recognition of iconicity doesn’t come for free. Developmental Science, 11, 841–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’reilly AW (1995). Using representations: Comprehension and production of actions with imagined objects. Child Development, 66(4), 999–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlansky MD, & Bonvillian JD (1984). The role of iconicity in early sign language acquisition. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 49(3), 287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega G (2017). Iconicity and sign lexical acquisition: A review. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega G, Sümer B, & Özyürek A (2017). Type of iconicity matters in the vocabulary development of signing children. Developmental Psychology, 53(1), 89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overton WF, & Jackson JP (1973). The representation of imagined objects in action sequences: A Developmental study. Child development, 309–314. [PubMed]

- Perniss P, Lu JC, Morgan G, & Vigliocco G (2017). Mapping language to the world: The role of iconicity in the sign language input. Developmental Science [DOI] [PubMed]

- Perry LK, Perlman M, & Lupyan G (2015). Iconicity in English and Spanish and its relation to lexical category and age of acquisition. PloS One, 10(9), e0137147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry LK, Perlman M, Winter B, Massaro DW, & Lupyan G (2018). Iconicity in the speech of children and adults. Developmental Science, 21(3), e12572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman M, Fusaroli R, Fein D, & Naigles L (2017). The use of iconic words in early childparent interactions. In the 39th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (CogSci 2017)(pp. 913–918). Cognitive Science Society. [Google Scholar]

- Perlman M, Little H, Thompson B, & Thompson RL (2018). Iconicity in signed and spoken vocabulary: A comparison between American sign language, British sign language, English, and Spanish. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reppen R, Ide N, & Suderman K (2005). American National Corpus (ANC) Second Release [DVD]

- Robinson D (2015). Geom Flat Violin. Github repository, https://gist.github.com/dgrtwo/eb7750e74997891d7c20

- Schwanenflugel PJ, Harnishfeger KK, & Stowe RW (1988). Context availability and lexical decisions for abstract and concrete words. Journal of Memory and Language, 27(5), 499–520. [Google Scholar]

- Senghas A, Pyers J, Zola C, & Quincoses C (2018). Different patterns of iconic influence in the creation vs. transmission of the Nicaraguan Sign Language lexicon. In the Proceedings of the 12 International Conference of the Evolution of Language Evolang; 12. [Google Scholar]

- Smith IM, & Bryson SE (2007). Gesture imitation in autism: II. Symbolic gestures and pantomimed object use. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 24(7), 679–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swingley D, & Humphrey C (2018). Quantitative linguistic predictors of infants’ learning of specific english words. Child Development, 89(4), 1247–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taub SF (2000). Language from the body: Iconicity and metaphor in American Sign Language Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RL, Vinson DP, & Vigliocco G (2010). The link between form and meaning in British Sign Language: Effects of iconicity for phonological decisions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 36(4), 1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RL, Vinson DP, Woll B, & Vigliocco G (2012). The road to language learning is iconic: Evidence from British Sign Language. Psychological Science, 23(12), 1443–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolar TD, Lederberg AR, Gokhale S, & Tomasello M (2007). The development of the ability to recognize the meaning of iconic signs. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 13(2), 225–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokowicz N, Kroll JF, De Groot AM, & Van Hell JG (2002). Number-of-translation norms for Dutch—English translation pairs: A new tool for examining language production. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 34(3), 435–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Schie HT, Wijers AA, Mars RB, Benjamins JS, & Stowe LA (2005). Processing of visual semantic information to concrete words: temporal dynamics and neural mechanisms indicated by event-related brain potentials. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 22(3–4), 364–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigliocco G, Meteyard L, Andrews M, & Kousta S (2009). Toward a theory of semantic representation. Language and Cognition, 1(2), 219–247. [Google Scholar]

- Vigliocco G, Vinson DP, Lewis W, & Garrett MF (2004). Representing the meanings of object and action words: The featural and unitary semantic space hypothesis. Cognitive Psychology, 48(4), 422–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H (2016). Elegant graphics for data analysis Springer-Verlag; New York. [Google Scholar]

- Winter B, Perlman M, Perry LK, & Lupyan G (2017). Which words are most iconic? Iconicity in English sensory words. Interaction Studies, 18(3), 433–454. [Google Scholar]

- Winter B, Sóskuthy M, & Perlman M (2017). R is for rough: Iconicity in English and Hungarian surface descriptors. Types of iconicity in language use, development, and processing MPI Nijmegen, Netherlands, July 2017. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.