Abstract

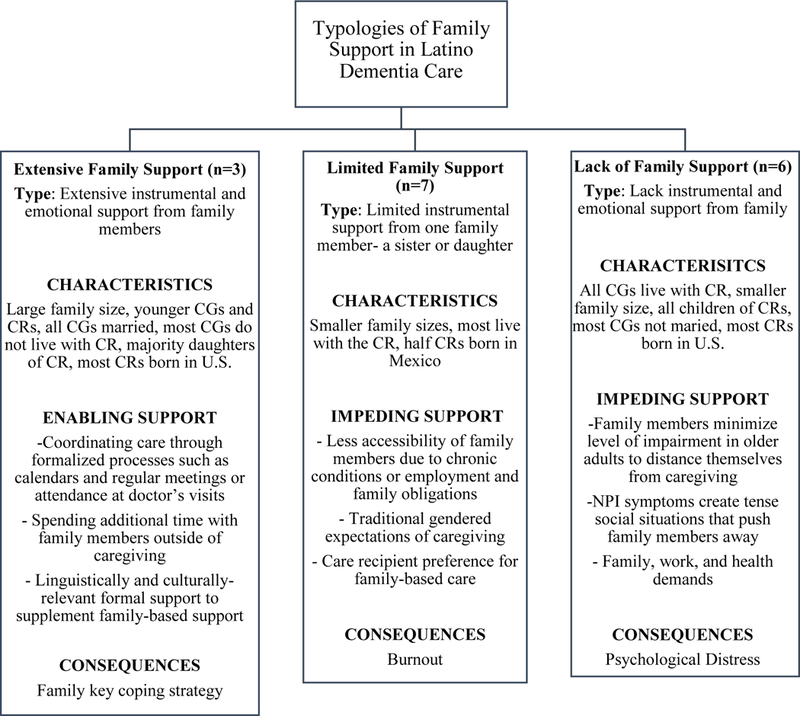

The purpose of this study is to explore variations in family support for Latino dementia caregivers and describe the role of the family in dementia caregiver stress processes. Content analysis is utilized with themes derived inductively from 16 in-depth interviews with Latino caregivers recruited in California from 2002 to 2004. Three types of family support are described: extensive (instrumental and emotional support from family, n=3), limited (instrumental support from one family member, n=7), and lacking (no support from family, n=6). Most caregivers report limited support, high risk for burnout and distress, and that dementia-related neuropsychiatric symptoms are obstacles to family unity. Caregivers with extensive support report a larger family size, adaptable family members, help outside of the family, and formalized processes for spreading caregiving duties across multiple persons. Culturally competent interventions should take into consideration diversity in Latino dementia care by (a) providing psychoeducation on problem solving and communication skills to multiple family members, particularly with respect to the nature of dementia and neuropsychiatric symptoms, and by (b) assisting caregivers in managing family tensions — including, when appropriate, employing tactics to mobilize family support.

Keywords: Dementia Caregiving, Latino Aging, Family Support

Over 8% of the population aged 65 and over identifies as Hispanic or Latino (Roberts, Ogunwole, Blakeslee, & Rabe, 2018) and this percentage is expected to increase to over 21% by 2060 (ACL, 2017). National studies also show that dementia is more prevalent among the Latino population than the non-Latino White population (Alzheimer’s Association, 2016; Wu et al., 2018) and that, by 2050, the number of Latinos with dementia is expected to rise to close to 1.3 million (National Institute on Aging, 2012). Latino older adults have longer life expectancies than other racial/ethnic groups, but also a higher prevalence of risk factors for dementia such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Wu et al., 2018; Latinos and Alzheimer’s Disease: New Numbers Behind the Crisis, 2016). As a result, older Latinos spend relatively more years living with dementia (Garcia et al., 2017). These trends in dementia are coupled with economic challenges affecting older Latinos, including high risk of poverty, high price of dementia-related costs, and less access to formal, paid dementia care (Wu et al., 2018).

Less access to formal care means that older Latinos tend to reside in the community and rely on family members for care and assistance (National Alliance on Caregiving and AARP Policy Institute, 2015). Given that Latino older adults tend to live longer with dementia and without formal support, Latino family caregivers tend to report more time-intensive caregiving situations than other racial/ethnic groups (National Alliance on Caregiving and AARP Policy Institute, 2015; Rote & : Moon, 2016). Some scholars attribute the trend of Latino family members providing a majority of long-term care support for older adults to cultural factors that emphasize family support (Angel, Rote, & Markides, 2017; Dilworth-Anderson, Williams, & Gibson, 2002). For instance, familism – the idea that family need ought to be placed before individual need – is a key factor implicated in Latino caregiving processes (Aranda & Knight, 1997; Knight & Sayegh, 2010; Mendez-Luck et al., 2016).

However, recent studies show variability in the size of Latino caregiver support networks and in adherence to this cultural norm, specifically regarding dementia care (Gelman, 2014; Losada et al., 2010; Mendez-Luck & Anthony, 2016). Adherence to cultural factors such as familism is likely reaffirming or stressful based on the availability of family support. The current study adds to the existing literature by exploring and describing the differing roles that families play in Latino dementia caregiving. The study utilizes the Sociocultural Caregiver Stress Process Model to describe (a) family support availability and functionality, (b) factors that enable or impede family support, and (c) the relationship between family support and caregiver well-being for Latino dementia caregivers.

Sociocultural Caregiving Stress and Coping Model

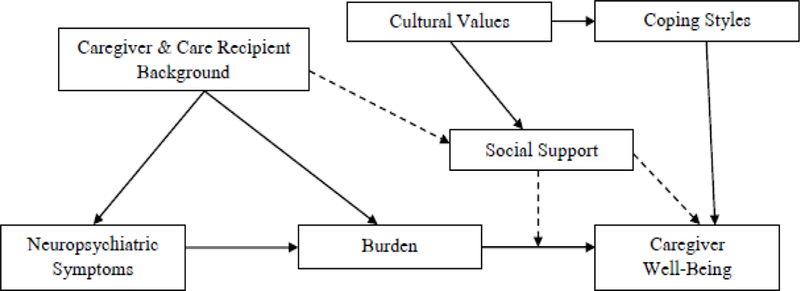

Aranda and Knight (1997) adapted general models of caregiving stress to describe the Sociocultural Caregiving Stress and Coping Model. This is the most common theoretical model used in research on Latino dementia care and is a contribution over general models due to the emphasis on the intersection of ethnicity and culture in caregiving (Knight & Sayegh, 2010). This model states that variations in caregiver health are shaped by caregiver and care recipient background, care recipient needs, and cultural values which influence caregiver burden, family support, and coping processes. Figure 1 presents an adapted model which guides our study of family support in Latino dementia care. First, the ability to cope with dementia caregiving is influenced by caregiving intensity, which encompasses care recipient functional ability or need for assistance.

Figure 1.

Caregiver Sociocultural Stress and Coping Model

Dementia-Related Neuropsychiatric Symptoms

In general, research shows that dementia care is especially stressful when the person with dementia displays neuropsychiatric symptoms related to dementia (Robinson & Knight, 2004). Common symptoms include agitation, wandering, resistance to care, physical aggression, inappropriate behavior, repetitive behavior, and sleep disturbance (Lyketsos et al., 2002). About 60% of all individuals living with dementia experience neuropsychiatric symptoms that undermine quality of life and impair the ability to carry out self-care tasks and live independently (Lyketsos et al., 2002). Research on Latino caregivers supports the sociocultural stress and coping model in that care recipient neuropsychiatric symptoms are linked to elevated caregiver depressive symptoms because they are related to greater caregiver stress and burden (Rote, Angel, & Markides, 2015).

There are many reasons dementia-related neuropsychiatric symptoms may be especially challenging for Latino caregivers. First, Latinos with dementia display more neuropsychiatric symptoms compared to other groups (Hinton et al., 2003; Sink et al., 2005). Second, there is a tendency for Latino caregivers to attribute such symptoms to other causes than dementia such as personality changes or normal aging processes, which can interfere with seeking support or adhering to treatment (Hinton et al., 2005, 2009; Latinos and Alzheimer’s Disease: New Numbers Behind the Crisis, 2016). Third, neuropsychiatric symptoms require additional monitoring and home modifications, as well as resources in terms of time, money, and support to cope with these demands. Lack of formal dementia care support utilization along with high rates of poverty among Latino family caregivers pose challenges for resource mobilization in the face of care for dementia-related neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Cultural Values of Family Support

As discussed earlier, familism – or the idea that family need takes precedence over individual need – is one cultural factor that influences caregiving preferences and structures. Gelman (2014) described variations in adherence to familism and identified three groups of Latino caregivers: caregivers who endorsed familism in a traditional or expected way, caregivers who did not identify with familism, and caregivers who described familism as an obligation that created strain or that was not reflective of actual support networks. Endorsing familistic cultural orientations towards caregiving is related to better health and well-being for Latino caregivers when caregiving is less time-intensive (Mendez-Luck et al., 2016) and when caregivers receive support from family members (Losada et al., 2010). Taken together, the literature shows that familism is not a consistent narrative in Latino dementia care and other factors such as care recipient health, caregiver income, family size, and family support influence coping processes (Angel et al., 2014; Mendez-Luck & Anthony, 2016).

Family Support

Families may be the basis for different types of support in dementia care. Instrumental support, which includes the provision of physical and material resources (House, 1981), is provided through assistance with activities of daily living, financial support, and monitoring of neuropsychiatric symptoms. Emotional support, which includes empathy, love, and trust from others (House, 1981), may lead older persons with dementia and their primary caregiver to feel interconnected. In so doing, emotional support may offset caregiver fatigue and overload. Support may be received, which includes actual, tangible support offered to the caregiver in times of need, as well as perceived, which refers to subjective assessments of social relationships in meeting the needs of caregivers (Uchino, 2009). Latino caregivers with a lack of family support report difficulty in managing dementia-related neuropsychiatric symptoms while families who accept, adapt to, and facilitate routines of care are better equipped to cope with neuropsychiatric symptoms (Llanque & Enriquez, 2012).

While the literature explores variation in cultural values and shows that adaptable families are more capable of providing support, more research is needed to identify and describe different forms of family support in Latino dementia care, the cultural and structural factors that shape family support networks, and the relationship between different forms of family support and caregiver well-being. Guided by the sociocultural stress and coping model and research on social support, the current study describes different types of family support in Latino dementia care, based on reports of both received and perceived instrumental and emotional support from family members. Understanding the different forms of social support available to Latino dementia caregivers —and the factors associated support — will provide more evidence for the types of interventions that will be most effective for subgroups within this larger population.

The Current Study

The aims of the current study are to:

Explore and describe a typology of family support based on the primary caregiver’s reports of instrumental and emotional support.

Identify the characteristics of each type of family support and the factors that enable or impede family support processes.

Describe the mental health of caregivers based on level of reported family support.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

Data.

The study is a cross-sectional, qualitative study that utilizes interview data collected as part of a larger study of non-Latino White and Latino older adults living with dementia-related neuropsychiatric symptoms which was conducted from 2002–2004 in the greater Sacramento area. Family caregivers of community-dwelling older adults with a diagnosis of dementia were referred from several sources, including the UC Davis Alzheimer Disease Center (Hinton et al, 2010), the Sacramento Latino Study on Aging (SALSA; Haan et al., 2003), an NIA funded and community-based study of cognitive impairment and dementia in Latinos in the Sacramento area, and a small number from local community agencies serving older adults. Subjects were recruited from multiple sources to reach recruitment goals for the larger project. Prospective participants were recruited by mail followed by a phone call from study staff explaining the study and screen for eligibility. To be eligible, caregivers needed to be age 21 or above and be identified as the family member providing the most day-to-day care for the person with dementia.

The current analysis is based on 16 Latino family caregivers randomly selected from the caregivers in the larger study who were interviewed in English. Family caregivers were interviewed in their home using a semi-structured interview guide that covered a range of topics, including social and family contexts of caregiving, neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, and patterns of help-seeking related to dementia-relate behavioral symptoms. The guide specifically asked about family functioning and support in Latino dementia are and methods of coping with caregiver stress. Interviews lasted one to two hours and were tape-recorded and transcribed. The study is approved by the UC Davis Institutional Review Board. Most of the caregivers identify as Mexican American (n=15) with one caregiver identifying as Puerto Rican.

Analysis

The analysis uses a conceptual content analysis approach (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) and began with initial coding of interview transcripts by the first two authors. This was followed by a discussion and identification of emergent patterns found within the interviews that characterized family support. The first two researchers developed operational definitions of family support based on both received and perceived as well as emotional and instrumental support identified by general models of social support availability and receipt (House, 1981; Uchino, 2009). The two researchers then reviewed all transcripts again and carefully and highlighted text that described family support, including the forms of support, impeding/enabling factors of family support, and the effects of support on caregiver well-being. The first two authors then determined the extent to which the data were supportive of general models describing forms of family and social support. The analysis included an iterative process where the researchers moved back and forth between the interview data and existing definitions of family support to establish the final codebook which was grounded in both a) the voices of your participants and b) existing definitions of family support which fit your participants’ lived experiences. The finalized codebook is based on iterative discussions of themes, interview transcripts, and existing theory (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Through the analysis process, the researchers discovered that three types of family-based social support were reported by Latino caregivers: extensive, limited, and lacking. These types were constructed based on the extent and quality of support from family reported by the caregiver. This classification scheme is based on data collected from each caregiver interview regarding the respondent’s perceptions of the amount (frequency), type (instrumental, emotional), and level (intensity) of family support received for dementia caregiving.

Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) criteria for rigor were employed to ensure credibility and confidence in our findings. During the analysis phase, the researchers enhanced credibility through peer debriefing and consensus building around themes. Data was collected and coded separately by research team members who met regularly to discuss, identify themes and meanings. In addition, the research team met to review negative cases, and discussed elements of the participants’ experiences that did not support the main patterns and themes that emerged from the analysis. Research team members engaged in reflexivity through memo writing to incorporate a continuous examination of bias throughout the research process.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents a description of the sample based on typology of family support: Type I - extensive, Type II - limited, and Type III - lacking help from a family member. Caregivers consisted of immediate members of the family, of which the majority were adult daughters of the care recipient. Presented next are both the characteristics that depict each type and the health consequences of differences forms of support in dementia family caregiving.

Table 1.

Sample Description

| Caregiver | CG Age Range |

CG Education | CG Married |

CG Born in US |

CG Relation to CR |

CR Born in the U.S. |

Lives with CR |

CG Household Income |

CR Age Range |

CR’s # Children |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maria | 40–49 | HS Degree | Yes | Yes | Daughter | Yes | No | Less than $30,000 | 70–79 | 7 |

| Tina | 40–49 | College Degree | Yes | Yes | Daughter | No | No | Missing | 70–79 | 12 |

| Sabrina | 60–69 | None | Yes | Yes | Wife | Yes | Yes | $30,000-$45,000 | 70–79 | 4 |

| Dominic | 40–49 | Some College | No | Yes | Son | No | Yes | Missing | 70–79 | 3 |

| Philip | 50–59 | Some College | No | No | Son | No | No | Over $45,000 | 80–89 | 4 |

| Lorenzo | 60–69 | HS Degree | Yes | Yes | Husband | Yes | Yes | Less than $30,000 | 60–69 | 2 |

| Ronaldo | 70–79 | HS Degree | Yes | Yes | Husband | Yes | Yes | $30,000-$45,000 | 80–89 | 6 |

| Alma | 50–59 | College Degree | No | Yes | Daughter | No | Yes | Less than $30,000 | 80–89 | 5 |

| Karina | 50–59 | HS Degree | No | Yes | Daughter | No | Yes | $30,000-$45,000 | 70–79 | 3 |

| Carla | 60–69 | Less than HS | Yes | Yes | Wife | Yes | Yes | Less than $30,000 | 70–79 | 4 |

| Emma | 60–69 | HS Degree | Yes | Yes | Daughter | Yes | Yes | Missing | 80–89 | 4 |

| Gabriel | 60–69 | Some College | No | Yes | Son | No | Yes | $30,000-$45,000 | 90+ | 1 |

| Rita | 40–49 | Some College | No | Yes | Daughter | Yes | Yes | Over $45,000 | 70–79 | 7 |

| Monica | 50–59 | HS Degree | No | No | Daughter | No | Yes | Over $45,000 | 80–89 | 4 |

| Melissa | 50–59 | Some College | Yes | Yes | Daughter | Yes | Yes | Over $45,000 | 80–89 | 2 |

| Cecilia | 50–59 | Some College | No | Yes | Daughter | Yes | Yes | Less than $30,000 | 70–79 | 3 |

Notes: CG=caregiver, CR=care recipient; Data Collection 2002–2004

Extensive Family Support: “We All Pitch In”

Latino dementia caregivers with extensive family support report frequent help with care responsibilities, receipt of emotional support from family members, and help outside of the family. Most dementia caregivers with this type of family support are married daughters of the care recipient, and do not live full-time in the same household as their care recipient/s.

Enabling Support: Formal Process for Management of Care

Maria is a middle-aged caregiver for her parents and has six siblings. Her mother was recently hospitalized while Maria was caring for her father who has been diagnosed with dementia. She explains that caring for both parents is challenging, and that caregiving for her father is especially stressful due to his symptoms of anger and agitation. However, like other caregivers with extensive support, Maria explains that she and her family - especially her sisters -are in constant contact with one another about their parents care:

“The sisters, we’re always calling each other to see how my mom’s doing, how dad’s doing. It’s like a full-time project for us, you know, so we’re all like mini caregivers.”

Maria has a large family and all sisters are willing to take on the role as a caregiver. Family members use clear communication as to who performs which task to cover their father’s care needs together as a family. Maria explains,

“…I’m the one responsible to do the bills and take my dad grocery shopping…we all kind of pitch in to, you know, fill in…if he needs anything he can call on us… I just take care of what I have to take care of, the sisters make sure he’s eaten, make sure everything’s okay at the house, you know, one of my sisters cleans up and stuff like that.”

Communication is also supplemented with more formal processes. As an illustration, Tina, who has eleven siblings, is providing dementia care for her mother, who has neuropsychiatric symptoms of forgetfulness, stubbornness, and antisocial behavior. Tina explains her family’s strategy for sharing care duties:

“…we have a calendar, and everybody has their week and I’m the keeper of the calendar, and I just remind everybody. The week starts on Sunday and it ends on Saturday, and if you can it’s nice for whoever can stay overnight. Most of us have tried to do that at least two or three times a week, stay overnight, but if not just visit in the evening and we all work full time, so I usually end up being there about six and I leave about nine. We try to have her eat something with us, and she seems to like that, she seems to like having us there in the evening.”

A calendar of care creates a more formal mechanism to involve family members in specific tasks and times of care. This process supports the primary caregiver in spreading responsibilities across multiple family members, which allows the primary caregiver to address competing demands from work and other family obligations.

Enabling Family Support: Spending Time Together

Dementia caregivers with extensive support also describe reciprocal exchange among family members, and a sense of belonging in the family. When asked what helps her get through difficult times, Maria emphasizes spending time with family:

“My family, just sharing with my sisters and, you know, my daughters and stuff like that, that’s what helps a lot.”

Dementia caregivers with extensive family support reveal that spending time with family members outside of caregiving helps to facilitate emotional closeness and reduce stress. Sabrina is an older caregiver to her husband who has dementia-related neuropsychiatric symptoms of agitation and aggression. She relies on her daughters for help with instrumental activities of daily living such as driving and doctors’ appointments for her husband. When asked about what helps her cope with dementia care, she highlights that spending time with her daughters is her primary coping strategy:

“We have four daughters but all four of them work every day, but they come here, like this week, I know they ‘re going to be here, you know. We get together for birthdays, and they have a party someplace, we all go and that, you know… We try to stay as happy, all of us together, you know, and cope with, try to do the best, because there’s nothing else you can you do, try to be happy, calm, and be patient…”

Spending time together and having a positive outlook as a family helps Sabrina manage the stress associated with spousal dementia care.

Enabling Family Support: Help Outside of the Family

Caregivers with extensive family-based rely on sources outside of the family unit to either bring the family together or supplement their efforts in dementia care. Even though Tina has eleven siblings and is providing care for her mother, she explains that, at first,

“…[A] few of my sisters were not even coming around to my mother’s house because they felt that mom was just being rude, she was just acting, acting out…”.

To mobilize family involvement, Tina had all her siblings present at a doctor’s appointment to hear from a medical professional that symptoms of stubbornness and antisocial behavior are dementia-related. She explains that this helped mobilize support,

“.and so now that has changed, it’s like we realize mom is sick and not that she’s doing it on purpose, she has an illness.”

Two caregivers with extensive support also utilize formal, paid caregivers to help with household tasks and daytime monitoring to supplement family care. It is important to highlight that formal support needed to be culturally and linguistically competent. Tina explains:

“…we didn’t want to put just anybody there with mom, we wanted somebody that was Hispanic, and she is fluent in Spanish and English. She is bilingual and we like that because…I don’t know I just feel more comfortable with somebody that is Hispanic…we feel really lucky that she was available to work.”

Although caregivers with extensive support indicate that family members are their primary sources of coping, help outside of the family allows families to better understand neuropsychiatric symptoms and manage dementia care.

Caregiver Well-Being with Extensive Support: Concerns for Future

Even with support from family which helps caregivers cope with caregiving demands, caregivers with family support report concerns about the future toll that caregiving may take on themselves and family members as the care recipient’s health declines further.

Tina explains:

“…sometimes I feel like I need it [a break], and I heard a few of my sibling say the same thing. But then, we think, well there’s so many of us and we should be able to support each other. But then instead my sister told me the other day, ‘sometimes you need to seek support outside of your own family’, but maybe later, I’m okay, right now we’re okay. My husband’s really supportive of and he’s real easy to talk to so I can talk to my husband, and there’s a few brothers and sisters that I feel closer to.”

A large family support system can also be constraining in that caregivers feel their existing family should be adequate in addressing future care needs of their family members living with dementia.

Limited Family Support: “They’ll Come Once in A While”

Eight dementia caregivers report that they receive some instrumental care help from one family member -- usually a sister or daughter. Compared to caregivers with extensive support, caregivers with limited support report having low or nonexistent emotional support from their families, smaller family sizes, and therefore less potential support-givers. Their care recipients tend to be older with more limitations and greater need for help, and they tend to reside with their dementia care recipient, thus experience more time-intensive caregiving situations.

Impeding Factor: Lack of Family Availability or Adaptability

Dominic is an unmarried middle-aged dementia caregiver to his mother and has two siblings. He describes the limited instrumental support that he receives from his sister:

“They come once in a while, my sister and my brother. My sister comes more than my brother, my brother comes once in a great while, to say hi, you know, but mostly my sister comes and takes her to the store, buys her clothes, if she needs clothes.”

Caregivers with limited support report that one family member provides inconsistent help with one task. All caregivers with limited support recall asking family members for help; however, family members are unresponsive. Dominic recalls trying to mobilize support,

“I call my sister and my brother and see if they’ll take her and give me a chance off, that’s what I told them. They said they’d try to work it out more, you know…but it doesn’t happen.”

Impeding Factor: Work and Other Family Obligations

An impeding factor that leads to the unavailability of support is work or other family, obligations. Lorenzo, who is in his sixties, and is a spousal dementia caregiver with two children, reports that one daughter keeps track of medical records and provides financial assistance for paid support a few hours a week. Lorenzo notes, however, that other family and work obligations, impede on his daughter’s ability to provide more support.

“Well the daughter, she helps me, you know, she’s busy Monday through Friday, you know, with that kind of position. And it goes with, you know parenting. She works late.”

Similarly, Ronaldo is also a spousal caregiver with six children and is responsible for, most of his wife’s care. While Ronaldo receives some help from his oldest daughter, he explains, that work and family obligations make it difficult to mobilize family members, hence why his, other children do not assist him in his caregiving duties.

“…the kids don’t come over, you know, and things like that…they have their jobs to do, and they have their families to take care of and we’re just secondary now, you know, their families are first…”

Impeding Factor: Gendered Expectations of Family Care

Karina is a middle-aged dementia caregiver and has three siblings. When asked about the help she receives from family, she explains a lack of widespread support from family members,

“My sister does, but my brothers are kind of in their own little world, you know, I think it has to do with the culture a lot of it, you know how they’re brought up. Like my Mom always had this thing that men are to be catered to and women are pretty [much] basic[ally] on their own, you know.”

She attributes her brothers’ lack of help to her mother’s cultural expectations that women are care providers. She expresses feeling distance between this cultural norm and the current demands she faces from employment and other family obligations and her personal need for additional support from family members.

Caregiver Well-Being with Limited Support: Caregiver Burnout

Lack of consistent and extensive support is related to caregiver burnout. Alma is a middle-aged dementia caregiver for her mother and has four siblings. She explains that while she is primarily responsible for her mother’s care, one of her sisters:

…[H]as been taking her with her when they go shopping, she helps me that way… other than that that’s all she does, I take care of my mother, all of her medications, all of her doctor visits, all of her follow ups, all her entertainment, all her dining out, all her grocery shopping, and what else, and I keep her. I’m her companion, okay, and sometimes it bugs me I guess because I’m feeling that way right now. I’m a little but [bit] frustrated, there’s five of us, and my brother’s nowhere to be found, he himself has health problems…”

Many caregivers report feeling frustrated and overwhelmed with the responsibility associated with the intense demands of dementia caregiving in a context of limited family support, especially when other family members are available but unwilling to help.

All caregivers with limited support report a need for help outside of the family in terms of a formal, paid caregiver, or a desire to place the care recipient in a nursing home. One of the barriers to accessing formal support is the care recipient’s preference for family-based care. For example, Emma, who is in her sixties, is a dementia caregiver to her mother and remembers a conversation wherein her mother invokes reciprocity as a primary reason for family-based care.

“She told me, ‘you got to take care of me because I took care of you when you were small.’ And I said, ‘I didn’t tell you to have me.’ I said, and besides, I says, ‘I got other brothers and sisters.’ I said, ‘they could take care of you…’”

However, family members are unresponsive to her requests for more support. Emma also reports feeling trapped and at risk for caregiver burnout and overload. She explains that, due to the nature of dementia progression, her mother is

“…going to expect more from me, which I’m not going to do it. I’m not going to stay here day and night with her. I’m not.”

All caregivers report the utilization of, or the need for, formal care to augment a lack of family support as well as a high risk for burnout. Ronaldo further emphasizes a need for support under low levels of family support, his risk for burnout, and his concerns about the future:

“All I can think of is [getting some help], because I figure sooner or later, my health may break down; it isn’t all that good anyhow right now.”

Lacking Family Support: “They Go Away”

The third pattern identified is dementia caregivers with a lack of both emotional and instrumental family-based support. Six caregivers - most of whom are women - report this type of family support. Most of these caregivers are unmarried, have some college education, and have a higher household income than other groups of caregivers do. All caregivers who report a lack of family support also co-reside with the care recipient. Caregivers with more resources hire formal caregivers, though they still report a need for family support.

Impeding Factor: Family Minimizes Impairment

Some families distance themselves from support provision by minimizing the severity of the care recipient’s limitations due to dementia. Gabriel, an older adult and an only child, provides dementia care for his mother in her nineties who displays depression and aggression. Gabriel, like other family caregivers without support, notes that the nature of the disease – mental rather than physical - makes it difficult rely on family members:

“…[T]hey look at her, and they say, ‘Well, how can anything be wrong with her?’ But the mind is a hard thing.”

Caregivers lacking support note that, because family members do not recognize symptoms as part of the disease, it is difficult for family members to provide support. Gabriel adds:

“You know, I have family members, cousins, who are very close. Hey she is fine, [they say]. I said, ‘Good, you take care of her this weekend.’ You don’t see them ever again… they go away.”

Gabriel’s children also distance themselves from caregiving. He attributes this to his adult children’s work and family demands, along with cultural, generational, and educational differences regarding who should provide care to aging family members. He adds:

“they all went through college and are very successful, but seem to be less patient with the theory of me taking care of her.”

Rita, a middle-aged caregiver who lives with both of her parents, is providing support to her mother, who shows dementia-related symptoms of forgetfulness, anger, and anxiety.

Although Rita has six siblings, she is the only one responsible for caring for her mother and lacks support from her siblings since they do not see or acknowledge the severity of their mother’s dementia symptoms. Rita describes her irritation,

“…[T]hat’s the frustrating thing that I find with my brothers because they’ll come over, ‘Oh mom’s doing good!’ like I’m making it up.”

When asked whether her brothers help care for her parents, Rita explains,

“No, not to help out, they’ll come by to visit but they’ll stay for like 10–15 minutes and then they leave. I think they struggle with my parents’ situation.”

Impeding Factor: Symptoms Push Family Members Away

Neuropsychiatric symptoms related to dementia also create tension in family living arrangements. Rita explains how symptoms themselves push family members away,

“My daughter is working at getting moved out because I think it’s been more, it’s becoming damaging for them, and, you know…she [her mother] gets very angry and very agitated and upset.”

Similarly, Carla has four children and is a caregiver to her husband who displays symptoms of stubbornness and verbal aggression. She tells the story of the time her daughter-in-law and son visited to help clean out the garage:

“I said, ‘thank you.’ I needed somebody to do that. But he [her husband] was mad because he says, ‘I don’t want nobody touching my stuff…I don’t want my kids coming in here doing stuff, and I don’t want them to touch.’”

When family members are adaptable and willing to help, dementia-related symptoms such as frustration and verbal aggression from the care recipient can stand in the way of the, primary caregiver receiving help from family.

Two caregivers lacking family support also report that, in addition to dementia care, they, provide care for grandchildren. Melissa, for example, provides care to her mother living with, dementia, as well as her four grandchildren. When asked about support from family, she explains, the lack of availability of it:

“There’s no other alternative, there’s just no other, nobody else is around.”

Like other caregivers without support, Melissa experiences tense social situations, because of neuropsychiatric symptoms, which becomes especially distressing when Melissa is, also providing care for her grandchildren. She provides an example:

“My mother stands watch as they [the grandchildren] watch television, and if they move the covers on the sofa, that’s an issue and it’s very difficult because she will actually stand over them and watch, and won’t leave them alone. And it’s difficult…it’s very tense…it’s very uncomfortable when they’re here, but they do have to be here sometimes.”

Consequences: Psychological Distress

All caregivers without family support describe a need for reprieve and report high levels, of distress. Because Melissa does not have the financial resources for formal, paid support and lacks any family members to rely on for help, she faces acute financial struggles and distress:

“I can’t work now. I’m trying to work out of the house but it’s very difficult, cause I’m always watching her, so my income goes… It’s taking its toll on me, you know, it’s very stressful, frustrating when they become very stubborn…I’m at the point where I’m getting, it’s affecting me a lot, and I know it cause I’m crying a lot, you know, and I look at my face and I’m angry and it’s happening.”

In addition to financial difficulty and stress, caregivers without support also report feeling, trapped in their role as a dementia caregiver. Monica is a middle-aged, unmarried caregiver to, her father, who has symptoms of hallucinations and depression. When asked about the biggest, challenge she faces, Monica says its being the sole care provider to her father and having, unresponsive siblings:

“[T]hat my whole life has been consumed by this [caregiving] …I’m going to have to make a decision to find a place for him because I know that it can affect my health, and I could end up getting sick and dying and then what’s going to happen to him? Then there’s also a little resentment toward my siblings, that they haven’t stepped up to the plate, even though I’ve asked them…I told them I didn’t want to be the sole person responsible for my dad, and that if I were I probably would only do it maybe for another couple of years. I told them that on the weekend it would be nice if, since there’s four of us, we could take turns. That hasn’t happened, and they are not willing to do that… I just basically feel I have no support from them, and I’m not - how shall I say - I’m to the point where I’m not expecting any support from them.”

Caregivers with unresponsive family members describe a desire to give up asking for, help or trying to mobilize family members, and a strong desire to leave the caregiving role, altogether. Monica explains that when she asked for help from her siblings:

“…[T]hey didn’t respond to it…and I’m thinking my options are maybe to hire somebody full time and have that person move in, or maybe put my dad in a home, or just say to one of them, ‘okay, it’s somebody else’s turn, I’m gone.’…I’ve been kind of rehearsing this, to say to my brother and sisters, you know, ‘I’m finished, one of you guys has to take over.’”

Cecilia is a caregiver to her mother, who has dementia-related symptoms of depression asm, well as difficulty remembering and eating. Cecilia has three siblings, one daughter, five, grandchildren, and is not currently married. In addition to dementia care, she provides care for, two of her grandchildren. She recalls calling on her siblings for help. To her sister she said,

“‘You know what, I’m not having trouble with mom or nothing, but you need to get involved with your mother’…that’s a lie…I told her I needed help…I’m really tired… I usually don’t ask for help either.”

While Cecilia’s sister helped her for two months, she stopped suddenly because the dementia-related symptoms of depression scared her sister and were hard to manage, thus, leaving Cecilia to provide all the care for her mother.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study supports previous research showing variability in family support availability for Latino dementia caregivers (Adams, Aranda, Kemp, & Takagi, 2002; Gelman, Tompkins, & Ihara, 2013; Janevic & Connell, 2001; Mendez-Luck & Anthony, 2015; Tuner et al., 2015). We contribute to this literature by describing a typology of family support that includes extensive support (high instrumental and emotional support), limited support (limited instrumental support), and lacking support (no instrumental or emotional support). We also describe the processes through which instrumental and emotional family support gets mobilized (or not) in dementia care. Drawing from the sociocultural caregiver stress and coping model and research on social support, we found that when instrumental and emotional family support is mobilized caregivers are better equipped at dealing with the stressors related to care for dementia-related neuropsychiatric symptoms. Data also reveal that lack of family support is a major stressor for Latino dementia caregivers and is a key factor in caregiver distress and burnout. Figure 1 summarizes the results of the study.

Precursors to supportive and adaptive families in dementia care include large family size, responsive family members, and the establishment of processes to mobilize family members. Our results reveal that a calendar of care and other organized, formal processes that bring family members into day-to-day caregiving activities may be an especially effective intervention for Latino dementia caregivers. The use of fotonovelas or pictorial tools that depict the ways primary caregivers can utilize existing resources have been shown to be effective in reducing stress for Latino dementia caregivers (Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2015). Therefore, fotonovelas that focus on mobilizing family support - both instrumental and emotional - in formal, concrete ways for specific tasks or at specific times is a key area for intervention with Latino dementia caregivers. These types of interventions, however, are likely most effective with the existence of available and responsive family members.

Latino dementia caregivers without responsive or available family members tend to co-reside with their care recipient, due to lack of other tertiary caregivers and financial concerns. Additionally, caregivers without support report that either (a) family members minimize the level of impairment in older family members, or (b) neuropsychiatric symptoms are so severe and disruptive that family members avoid encounters with the primary caregiver and the older adult. This supports prior research that finds that older adults become isolated as cognitive impairment and comorbid neuropsychiatric symptoms make interactions with others more challenging (Hinton, Chambers, & Velásquez, 2009). Educational interventions that focus on how to effectively address neuropsychiatric symptoms, navigate the dementia caregiving role, and adopt a biomedical view of neuropsychiatric symptoms are additional ways to intervene with Latino dementia caregivers (Apesoa-Varano et al., 2012; Napoles et al., 2010), especially caregivers with low levels or without family support.

Factors that compound the effects of lack of support on Latino dementia caregiver well-being include the cultural-based care preferences of the older adults and the caregivers’ competing work, family, and health demands. Cultural- or personal- based care preferences, which tend to call on the oldest daughter to be the primary and oftentimes sole caregiver, limit support mobilization within and outside of the family and, thus, created strain for caregivers. Additionally, work, health (e.g., diabetes and depression), and other family (care for children and grandchildren) demands limited the ability of family members to provide support to the primary caregiver. Data also reveal that similar demands also made it difficult for primary caregivers to navigate the role of dementia caregiver alone. One potential way to intervene is the use of paid and culturally and linguistically relevant services. In-home care services may be most effective for Latino dementia caregivers as they complement cultural or personal preferences for in-home care, but also give families reprieve from caregiving duties to fulfill other obligations (Crist et al., 2009). The financial implications of such services is also a constraint to caregivers.

There are certain limitations of the current study. The sample is non-probability, and based in one region (i.e., California’s central valley), which leads to limitations in generalizability. These results are based on a small sample of mostly Mexican American caregivers and therefore not generalizable to all Latino caregivers. However, these findings describe important underlying processes that facilitate or impede family support in Latino dementia care, of which are likely generalizable across settings. Future studies, therefore, should examine whether similar patterns of family support may be observed in larger samples with representation from Mexican-origin and other Latino caregivers from all over the U.S. In areas of the country with a lower population of Latinos, caregiver reliance on family members may be especially pronounced. Similarly, as other studies have found, adherence to cultural values and caregiving networks are highly dependent on immigration-related factors (Angel et al., 2014; Mendez-Luck & Anthony, 2016). While our data show that a larger percentage of caregivers with limited compared to extensive support provide care for immigrant older adults, the current study did not focus specifically on whether nativity, generational status, or language use influenced family support processes; we encourage this for a future study.

Overall, our findings indicate that many Latino caregivers and their family members would greatly benefit from additional education on dementia-related behavioral symptoms provided by primary care providers, geriatric social workers and lay members of the community who work for pay or as volunteers in association with the local health care system. Community health workers (CHWs) such as Promotoras who typically focus on physical health issues can serve as supplemental support for older Latinos with dementia (Askari, Bilbrey, Garcia Ruiz, Humber, & Gallagher-Thompson, 2018) by assisting family members in managing a care plan that is customized to address behavioral symptoms as the disease progresses (Vega, Cabrera, Wygant, Velez-Ortiz, & Counts, 2017). Customized care plans can focus on mobilizing family support (if available) or support outside of the family (if preferred). This can alleviate individual and cultural obstacles faced by Latino family caregivers that inhibit their access to community-based aging services and supports.

Figure 2.

Characteristics, Factors, and Consequences by Type of Family Support

Notes: CR= Care Recipient, CG= Caregiver; Data Collection 2002–2004

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest. There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Adams B, Aranda MP, Kemp B, & Takagi K (2002). Ethnic and gender differences in distress among Anglo American, African American, Japanese American, and Mexican American spousal caregivers of persons with dementia. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology, 8(4), 279–301. [Google Scholar]

- Administration for Community Living (ACL), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). Profile of Hispanic Americans Aged 65 and Over: 2017. Retrieved from: https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/Aging%20and%20Disability%20in%20America/2017OAProfileHA508.pdf

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2016). 2016 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Retrieved from https://www.alz.org/documents_custom/2016-facts-and-figures.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- Angel JL, Rote SM, Brown DC, Angel RJ, & Markides KS (2014). Nativity status and sources of care assistance among elderly Mexican-Origin adults. Journal of cross-cultural gerontology, 29(3), 243–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel JL, Rote S, & Markides K. (2017). “The Role of the Latino Family in Late-Life Caregiving” Pp. 38–53 in Later-Life Social Support and Service Provision in Diverse and Vulnerable Populations co, edited by Wilmoth JM and Silverstein MD. New York: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Apesoa-Varano EC, Barker JC, & Hinton L (2012). Mexican-American Families and Dementia: An Exploration of “Work” in Response to Dementia-Related Aggressive Behavior In Angel JL (Ed.), Torres-Gil F(Ed.), & Markides K(Ed.), Aging, Health, and Longevity in the Mexican-Origin Population (pp. 277–291). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda MP, & Knight BG (1997). The influence of ethnicity and culture on the caregiver stress and coping process: A sociocultural review and analysis. The Gerontologist, 37(3), 342–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askari N, Bilbrey AC, Garcia Ruiz I, Humber MB, & Gallagher-Thompson D (2018). Dementia, Awareness Campaign in The Latino Community: A Novel Community Engagement Pilot Training Program with Promotoras. Clinical Gerontologist, 41(3), 200–208. Doi: 10.1080/07317115.2017.1398799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crist JD, Marylyn Morris McEwen PB, Suk-Sun Kim RN, & Alice Pasvogel RN (2009). Caregiving burden, acculturation, familism, and Mexican American elders’ use of home care services. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice, 23(3), 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Williams IC, & Gibson BE (2002). Issues of Race, Ethnicity, and Culture in Caregiving Research: A Twenty - year Review (1980–2000). The Gerontologist, 42(2), 237–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Tzuang M, Hinton L, Alvarez P, Rengifo J, Valverde I, … & Thompson LW (2015). Effectiveness of a fotonovela for reducing depression and stress in Latino dementia family caregivers. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders, 29(2), 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MA, Downer B, Chiu CT, Saenz JL, Rote S, & Wong R (2017). Racial/ethnic and nativity differences in cognitive life expectancies among older adults in the United States. The Gerontologist, 59(2), 281–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman CR (2014). Familismo and its impact on the family caregiving of Latinos with Alzheimer’s disease: a complex narrative. Research on Aging, 36(1), 40–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman CR, Tompkins CJ, & Ihara ES (2013). The complexities of caregiving for minority older adults: Rewards and challenges. Handbook of minority aging, 313–328. [Google Scholar]

- Haan MN, Mungas DM, Gonzalez HM, Ortiz TA, Acharya A, & Jagust WJ (2003). Prevalence of dementia in older Latinos: the influence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, stroke and genetic factors. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51(2), 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L, Carter K, Reed BR, Beckett L, Lara E, DeCarli C, & Mungas D (2010). Recruitment of a community-based cohort for research on diversity and risk of dementia. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders, 24(3), 234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L, Chambers D, & Velasquez A (2009). Making sense of behavioral disturbances in persons with dementia: Latino family caregiver attributions of neuropsychiatric inventory domains. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders, 23(4), 401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L, Haan M, Geller S, & Mungas D (2003). Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Latino Elders with Dementia or Cognitive Impairment without Dementia and Factors that Modify their Association with Caregiver Depression. The Gerontologist, 43(5), 669–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS (1981). Work stress and social support. Reading, MA: Adison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 5(9), 1277–1288. doi:doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janevic MR, & M Connell C (2001). Racial, ethnic, and cultural differences in the dementia caregiving experience: Recent findings. The Gerontologist, 41(3), 334–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight BG, & Sayegh P (2010). Cultural values and caregiving: The updated sociocultural stress and coping model. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 65(1), 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latinos and Alzheimer’s Disease: New Numbers Behind the Crisis. (2016). USC Edward R. Roybal Institute on Aging and the LatinosAgainstAlzheimer’s Network. Retrieved from: https://www.usagainstalzheimers.org/sites/default/files/2018-02/Latinos-and-AD_USC_UsA2-Impact-Report.pdf

- Lincoln YS, & Guba EG (1985). Establishing trustworthiness. Naturalistic inquiry, 289, 331. [Google Scholar]

- Llanque SM, & Enriquez M (2012). Interventions for Hispanic caregivers of patients with dementia: A review of the literature. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 27(1), 23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losada A, Márquez-González M, Knight BG, Yanguas J, Sayegh P, & Romero-Moreno R (2010). Psychosocial factors and caregivers’ distress: Effects of familism and dysfunctional thoughts. Aging & Mental Health, 14(2), 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, & DeKosky S (2002). Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA, 288(12), 1475–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Luck CA, & Anthony KP (2016). Marianismo and caregiving role beliefs among US-born and immigrant Mexican women. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71(5), 926–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez- Luck CA, Applewhite SR, Lara VE, & Toyokawa N (2016). The Concept of Familism in the Lived Experiences of Mexican- Origin Caregivers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(3), 813–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoles AM, Chadiha L, Eversley R, & Moreno-John G (2010). Reviews: developing culturally sensitive dementia caregiver interventions: are we there yet?. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias®, 25(5), 389–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance on Caregiving AARP Public Policy Institute. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S. 2015 - Focused Look at Caregivers of Adults Age 50+. Retrieved from http://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/2015_CaregivingintheUS_Care-Recipients-0ver-50WEB.pdf

- National Institute on Aging. (2012). Health disparities and Alzheimer’s disease. Retrieved from http://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/publication/2011-2012-alzheimers-disease-progress-report/health-disparities-and

- Roberts AW, Ogunwole SU, Blakeslee L, & Rabe MA (2018). The Population 65 Years and Older in the United States: 2016 Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/acs/ACS-38.pdf

- Robinson GS, & Knight BG (2004). Preliminary study investigating acculturation, cultural values, and psychological distress in Latino caregivers of dementia patients. Journal of Mental Health and Aging, 10, 183–194 [Google Scholar]

- Rote S, Angel J, & Markides K. (2014). Health of Elderly Mexican American Adults and Family Caregiver Distress. Research on Aging. doi: 10.1177/0164027514531028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rote SM, & Moon H (2016). Racial/Ethnic Differences in Caregiving Frequency: Does Immigrant Status Matter?. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, gbw106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RM, Hinton L, Gallagher-Thompson D, Tzuang M, Tran C, & Valle R (2015). Using an emic lens to understand how Latino families cope with dementia behavioral problems. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 30(5), 454–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN (2009). Understanding the links between social support and physical health: A life-span perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspectives on psychological science, 4(3), 236–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega IE, Cabrera LY, Wygant CM, Velez-Ortiz D, & Counts SE (2017). Alzheimer’s Disease In The Latino Community: Intersection Of Genetics And Social Determinants Of Health. Journal Of Alzheimer’s Disease, 58(4), 979–992. Doi: 10.3233/Jad-161261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Rodriguez F, Jin H, & Vega WA (2019). Latino and Alzheimer’s: Social Determinants and Personal Factors Contributing to Disease Risk In Contextualizing Health and Aging in the Americas (pp. 63–84). Springer, Cham. [Google Scholar]