Abstract

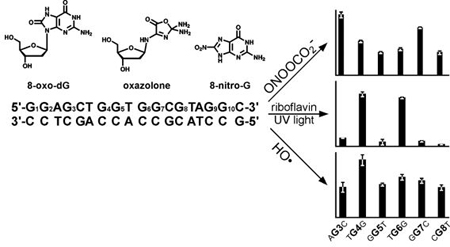

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species generated during respiration, inflammation, and immune response can damage cellular DNA, contributing to aging, cancer, and neurodegeneration. The ability of oxidized DNA bases to interfere with DNA replication and transcription is strongly influenced by their chemical structures and locations with the genome. In the present work, we examined the influence of local DNA sequence context, DNA secondary structure, and oxidant identity on the efficiency and the chemistry of guanine oxidation in the context of the Kras protooncogene. A novel isotope labeling strategy developed in our laboratory was used to accurately map the formation of 2,2-diamino-4-[(2-deoxy-β-D-erythropentofuranosyl)amino]-5(2H)-oxazolone (Z), 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-deoxyguanosine (OG), and 8-nitroguanine (8-NO2-G) lesions along DNA duplexes following photooxidation in the presence of riboflavin, treatment with nitrosoperoxycarbonate, and oxidation in the presence of hydroxyl radicals. Riboflavin-mediated photooxidation preferentially induced OG lesions at 5’ guanines within GG repeats, while treatment with nitrosoperoxycarbonate targeted 3’-guanines within GG and AG dinucleotides. Little sequence selectivity was observed following hydroxyl radical-mediated oxidation. However, Z and 8-NO2-G adducts were overproduced at duplex ends, irrespective of oxidant identity. Overall, our results indicate that the patterns of Z, OG, and 8-NO2-G adduct formation in the genome are distinct and are influenced by oxidant identity and the secondary structure of DNA.

Keywords: 8-oxo-guanine, Kras protooncogene, Reactive oxygen species, DNA damage, Isotope labeling of DNA-mass spectrometry

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (e.g. hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, superoxide, peroxynitrite, singlet oxygen) can be induced in living cells upon exposure to ionizing radiation and also form endogenously as a result of aerobic metabolism, immune response, and inflammation (1,2). Oxidative degradation of DNA is implicated in aging, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases (1–9). Among the four DNA bases, guanine has the lowest redox potential and is preferentially targeted for oxidation (10,11). Interestingly, oxidative guanine lesions can be found at nucleobases remote from the site of initial one-electron oxidation as a result of electron hole migration along DNA duplex to the sites of lowest ionization potential, e.g. the 5’ guanines of GG and GGG repeats (10,12–15) and endogenously methylated MeCG dinucleotides (16).

Guanine oxidation gives rise to a variety of products, including 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-deoxyguanosine (OG), spiroiminodihydantoin (Sp), 5-guanidinohydantoin (Gh), 2-amino-5-[2-deoxy-β-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)amino]-4H-imidazol-4-one (Im) and its hydrolysis product, 2,2-diamino-4-[(2-deoxy-β-D-erythropentofuranosyl)amino]-5(2H)-oxazolone (Z) (17–23), while guanine nitration in the presence of peroxynitrite produces 8-NO2-G (24). These nucleobase adducts are associated with specific biological outcomes as a result of their distinct base pairing characteristics, sequence-dependent formation, and structural recognition by regulatory and DNA repair proteins (11,25–28). However, our understanding of sequence-dependent formation of specific DNA lesions is incomplete because of the limitations of experimental methodologies employed in previous studies.

Sequence specificity for DNA oxidation has been traditionally determined by PAGE of alkali- generated DNA fragments to reveal the sites of nucleobase damage and thus have provided little information about lesion structures (29). Oxidative DNA lesions have been broadly classified as “Fpg sensitive lesions” and “piperidine sensitive lesions” based on their propensity to be cleaved by repair proteins and alkali treatment, respectively (30–32). More recently, a novel methodology based in isotope labeling of DNA-mass spectrometry (ILD-MS) developed in our laboratory has enabled structural characterization and quantification of oxidative nucleobase lesions originating from specific sites within DNA (16,33–36). We have previously used ILD-MS to show that photooxidation-induced OG and Z lesions preferentially form at guanine bases adjacent to 5-methylcytosine, an epigenetic DNA modification frequently found at CpG repeats of gene promoter sequences (16).

The main goal of the present investigation was to map the formation of structurally defined oxidative DNA lesions within a frequently mutated region of the K-ras protooncogene (codons 10–15) following photooxidation in the presence of riboflavin, treatment with nitrosoperoxycarbonate, and exposure to hydroxyl radicals. To our knowledge, this study is the first to map sequence–dependent formation of specific guanine oxidation and nitration products (OG, Z, and 8-NO2-G) following treatment with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. These results are important for our understanding of DNA oxidation chemistry and will be helpful in establishing a link between ROS exposure, DNA damage, mutations, and epigenetic regulation of antioxidant response.

METHODS

Chemicals.

Ammonium acetate, acetonitrile, methanol, ascorbic acid, sodium bicarbonate, hydrogen peroxide, nuclease P1, alkaline phosphatase, 8-bromo-dG, and riboflavin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI). Sodium phosphate and isopropyl alcohol were from Fisher Scientific (Hanover Park, IL). Peroxynitrite was obtained from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). 15N3,13C1-dG and 15N3,13C1-dG phosphoramidites were synthesized at Rutgers University as described elsewhere (37,38).

Preparation of Nucleoside Adduct Standards and Isotopically Labeled Standards.

Z, OG and their 15N3,13C1-labeled analogues were synthesized from 2’-deoxyguanosine (dG) and 15N3,13C1-dG, respectively (39). 8-NO2-G was prepared by reacting 8-bromo-dG (Sigma-Aldrich) with a 10-fold molar excess of sodium nitrite in DMF (24,40). The reaction mixture was refluxed for 24 hours at 150 °C under nitrogen atmosphere, concentrated under vacuum, dissolved in 100 mM triethylammonium acetate (pH 7), filtered, and separated by HPLC (39). Molar concentrations of 8-NO2-G solutions were determined by UV spectrophotometry (ε400 = 9.14 × 103 M−1 cm−1) (41). 15N3,13C1-8-NO2-G was prepared analogously starting with 15N3,13C1-8-bromo-dG. 15N3,13C1-8-bromo-dG was generated by treating 15N3,13C1-dG with aqueous bromine (42), followed by purification by SPE. 15N3,13C1-8-bromo-dG was converted to 15N3,13C1-8-NO2-G by reaction with sodium nitrite and purified as described above (24,40). Structural identities of all synthetic standards were confirmed by HPLC-UV, NMR, and tandem mass spectrometry.

DNA Oligodeoxynucleotides.

Synthetic DNA 18-mers (G1G2ACTG3G4TG5G6CG7TAG8G9C were prepared by solid phase synthesis, and stable isotope tag was introduced at specified positions (G1, G3, G4, G5, G6, G7, G8, or G9 as shown in Table 1). Their sequence was derived from a frequently mutated region of the K-ras protooncogene (codons 10–15). All oligodeoxynucleotides were prepared by standard solid phase chemistry on an Applied Biosystems ABI 394 instrument (Foster City, CA). 15N3,13C1-dG was introduced using 1,7,NH2-15N-2-13C-dG phosphoramidite (37,38). Synthetic DNA oligomers were purified by HPLC as described previously (43). The identity and the purity of each DNA strand (> 99%) were confirmed by HPLC-ESI--MS (Table 1). Isotopically labeled DNA oligomers (200 μM) were annealed the corresponding complementary strands in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer containing 50 mM sodium chloride (pH 8). UV melting curves were generated with a Cary 100 spectrophotometer using a 20 μM dsDNA solution in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer containing 50 mM NaCl (pH 7). The samples were heated from 30 °C to 90 °C at a rate of 0.5 °C/min with a 10 min hold time, and UV260 data was recorded every 0.2 °C.

Table 1.

DNA sequences used in the present study.

| ID | Sequence | Observed MW | Calculated MW |

|---|---|---|---|

| [15N3,13C1]-Kras-G1 | [15N3,13C1-G]GAGCTGGTGGCGTAGGC | 5639.9 | 5640.7 |

| [15N3,13C1]-Kras-G3 | GGA[15N3,13C1-G]CTGGTGGCGTAGGC | 5639.7 | 5640.7 |

| [15N3,13C1]-Kras-G4 | GGAGCT[15N3,13C1-G]GTGGCGTAGGC | 5640.0 | 5640.7 |

| [15N3,13C1]-Kras-G5 | GGAGCTG[15N3,13C1-G]TGGCGTAGGC | 5639.9 | 5640.7 |

| [15N3,13C1]-Kras-G6 | GGAGCTGGT[15N3,13C1-G]GCGTAGGC | 5640.0 | 5640.7 |

| [15N3,13C1]-Kras-G7 | GGAGCTGGTG[15N3,13C1-G]CGTAGGC | 5640.0 | 5640.7 |

| [15N3,13C1]-Kras-G8 | GGAGCTGGTGGC[15N3,13C1-G]TAGGC | 5640.0 | 5640.7 |

| [15N3,13C1]-Kras-G9 | GGAGCTGGTGGCGTA[15N3,13C1-G]GC | 5640.3 | 5640.7 |

| (–)-Kras | GCCTACGCCACCAGCTCC | 5365.0 | 5365.5 |

Exonuclease Sequencing.

To confirm the location of the 15N3,13C1-dG in each synthetic strand, they were subjected to controlled digestion with phosphodiesterase I or phosphodiesterase II, followed by analysis of the resulting exonuclease ladders by MALDI-TOF (Supplementary Tables S1 – S6) (44).

Riboflavin Mediated Photooxidation.

DNA duplexes (3 nmol, in triplicate) were dissolved in 15 μL of 100 mM NaCl. Oxygenated riboflavin solution was prepared by purging an aqueous solution of riboflavin (62.5 μM, containing 10 mM sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7) with oxygen. DNA duplexes were combined with riboflavin solution (60 μL) to achieve the final concentrations of 50 μM riboflavin and 40 μM DNA. The reactions were placed into clear glass vials suspended in ice-cold water and irradiated for 20 min with a 60-watt tungsten bulb positioned 5 cm from the vial. Photooxidized DNA samples were either analyzed immediately or transferred to low actinic vials and stored at −80 °C.

Nitrosoperoxycarbonate Treatment.

DNA duplexes (3 nmol aliquots, in triplicate) were dissolved in 20 μL of 31 mM sodium bicarbonate/188 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.9 and cooled on ice. A 5 μL aliquot of 5 mM peroxynitrite solution (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) in 50 mM NaOH was added to each sample to achieve the final concentration of 1 mM peroxynitrite. Samples were vigorously mixed by vortexing for 30 s and incubated at room temperature for 30 min, followed by DNA precipitation with cold ethanol.

Hydrogen Peroxide/Ascorbic Acid Treatment.

DNA duplexes (3 nmol, in triplicate) were oxidized in the presence of 12 mM ascorbic acid and 3.5 mM of H2O2 in 150 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) (45). Samples were incubated at 37 °C for 4 hours, followed by DNA precipitation with cold ethanol.

Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Oxidized DNA.

DNA samples (2 nmol) were diluted with buffer to reach the final concentration of 25 mM ammonium acetate/2.5 mM zinc chloride/5 mM TEMPO, pH 5.3. DNA hydrolysis was performed in the presence of nuclease P1 (4.5 U) and alkaline phosphatase (25 U) for 2 hours at 37 °C. The completeness of enzymatic hydrolysis was confirmed by HPLC-UV analysis of enzymatic digests (39). Our previous experiments have revealed that under these conditions, 8-nitro-dG is quantitatively converted to 8-NO2-G via spontaneous depurination (29). Samples were split into two for separate analyses of Z and OG/8-NO2-G. Aliquots designated for Z analysis were incubated 18 h at 25 °C in the dark to allow for the conversion of imidazolone to Z (46).

Concentration Dependence Experiments.

Unlabeled DNA duplexes (3 nmol, in triplicate) were irradiated in the presence of riboflavin for 0, 2, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 60 min, treated with increasing concentrations of peroxynitrite (0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2, 5, and 10 mM), or incubated with H2O2/ ascorbate (0, 1, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 15, and 20 mM) as described above. Following DNA precipitation with cold ethanol, samples were spiked with 15N2,13C1-Z and 15N3,13C1-OG (6 pmol each, internal standards for mass spectrometry) and subjected to enzymatic hydrolysis as described above.

Sample Preparation for Z Analysis by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS.

Z was purified by solid phase extraction (SPE) using 150 mg Carbograph SPE cartridges (Grace, Columbia, MD) Samples were diluted to 1 mL with water and loaded onto the cartridges, which were pre-equilibrated with methanol and water. SPE columns were washed with 1 mL of water, and Z was eluted with 3 mL of 20% methanol in water. SPE fractions containing the analyte were dried under reduced pressure and re-dissolved in 20 μL of water prior to HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis.

Sample Preparation for 8-oxo-dG and 8-nitro-G Analysis by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS.

OG and 8-NO2-G were isolated from DNA hydrolysates using off-line HPLC. A Synergi Hydro-RP [4.6 × 250 mm, 4 μm] column (Phenomenex) was eluted at a flow rate of 1 mL/min with a gradient of 10 mM ammonium formate, pH 4.2 containing 6% methanol (solvent A) and 100% acetonitrile (solvent B). Solvent composition was maintained at 0% B from 0 to 32 min, followed by a linear increase to 50% B from 32 to 36 min, and kept at 50% B for 4 min. HPLC fractions containing 8-NO2-G (16 – 20.4 min) and OG (26.9 – 32.6 min) were collected using an Agilent 1100 fraction collector and immediately placed in –20 °C freezer to minimize secondary oxidation.

Capillary HPLC-ESI-MS/MS Analysis.

TSQ Quantum mass spectrometer was interfaced with an Agilent Technologies 1100 capillary HPLC. For analysis of Z, a Hypercarb column (0.5 × 100 mm, 5 μm) was eluted with a flow rate of 12 μL/min at a gradient of 3:1 isopropanol: acetonitrile (solvent B) in 0.05% acetic acid (solvent A). HPLC solvent composition was gradually changed as follows: 0 min, 1.5% B; 7.1 min, 10.2% B; 7.6 min, 1.5% B; 16 min, 1.5% B. Typically, the electrospray ionization (ESI) ion source temperature was set to 250 °C, with a spray voltage at 3.1 kV. Quantitative analyses were performed in the selected reaction monitoring mode. The first quadrupole was set to isolate the protonated molecules ([M + H]+) of Z (m/z 247.1) and 15N2,13C1-Z (m/z 250.1), and their fragmentation was induced in the second quadrupole serving as a collision cell. Typical fragmentation energy was 14 V, with a collision gas pressure (Ar) of 1 mTorr. The third quadrupole was set to isolate the product ions corresponding to the neutral loss of deoxyribose and CO2 ([M + 2H – dR – CO2]+): m/z 87.1 for Z and m/z 90.1 for 15N2,13C1-Z). The lower limit of detection for detection of Z was estimated as 5 fmol (S/N = 10).

For HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis of OG and 15N3,13C1-OG, an Agilent Extend C18 column (0.5 × 150 mm, 3.5 μm) was eluted isocratically with 13% methanol in 10 mM ammonium formate, pH 4.2. The HPLC flow rate was 11 μL/min, and the column was maintained at 10 °C. The mass spectrometry parameters were optimized to achieve maximum sensitivity. Typically, the source temperature was kept at 50 °C, and the spray voltage was set to 3.1 kV. Quantitative analyses were performed in the selected reaction monitoring mode. The first quadrupole was set to isolate the protonated molecules ([M + H]+) of OG (m/z 284.1) and 15N3,13C1-OG (m/z 288.1), and their fragmentation was induced in the second quadrupole serving as a collision cell. Typical fragmentation energy was 14 V, with a collision gas pressure (Ar) of 1 mTorr. The third quadrupole was set to isolate the product ions corresponding to the neutral loss of deoxyribose ([M + 2H – dR]+): m/z 168.1 for 8-oxo-dG and m/z 172.1 for 15N3,13C1-OG. The lower limit of detection for OG was 3 fmol (S/N = 10).

For analyses of 8-NO2-G, an Agilent Extend-C18 column (0.5 × 150 mm, 3.5 μm) was eluted with a flow rate of 14 μL/min at 25 °C with a gradient of 3:1 methanol:acetonitrile (solvent B) in 5 mM N,N-dimethylhexylamine (DMHA), pH 9.2 (solvent A). Solvent composition was changed as follows: 0 min, 3% B; 9 min, 8.4% B; 11 min, 60% B; 14 min, 60% B; 16 min, 3% B; 28 min, 3% B. 8-NO2-G was detected in the negative ion mode. Typically, the ESI source temperature was set to 250 °C, and the spray voltage was −2.7 kV. Quantitative analyses were performed in the selected reaction monitoring mode. The first quadrupole was set to isolate the deprotonated molecules ([M - H]-) of 8-NO2-G (m/z 195.0) and 15N3,13C1-8-NO2-G (m/z 199.0), and their fragmentation was induced in the second quadrupole serving as a collision cell. Typical fragmentation energy was 17 V, with a collision gas pressure (Ar) of 1.3 mTorr. The third quadrupole was set to isolate the product ions at m/z 153.1 for 8-NO2-G and m/z 154.1 for 15N3,13C1-8-NO2-G. The lower limit of detection for 8-NO2-G was estimated as 10 fmol (S/N = 10).

ILD-MS experiments to determine sequence-dependent adduct formation.

The extent of adduct formation at the 15N3,13C1-labeled guanine (X) was calculated using the following equation: % reaction at X = Aadduct-dX/(Aadduct-dX + Aadduct-dG) x 100%,where Aadduct-dX and Aadduct-dG are the areas under the HPLC-ESI-MS/MS peaks corresponding to the 15N,13C labeled and unlabeled adducts, respectively.

Statistical Analyses.

All statistical analyses were performed at the Biostatistics and Informatics Core of the Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the differences in mean percent reactivity among groups. If the overall F-test showed significance, the Bonferroni method was applied to adjust the p-values for pair-wise comparisons between groups. The Bonferroni method was used to maintain the overall level of significance for multiple comparisons. The two-way ANOVA tested for differences in reactivity within and between the groups, while controlling for the effect of the individual Gs. Again, the Bonferroni method was applied to adjust p-values of pair-wise comparisons. All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS (Statistical Analysis Software) version 9.1. The significance level was set at 5%.

RESULTS

Stable Isotope Labeling Approach.

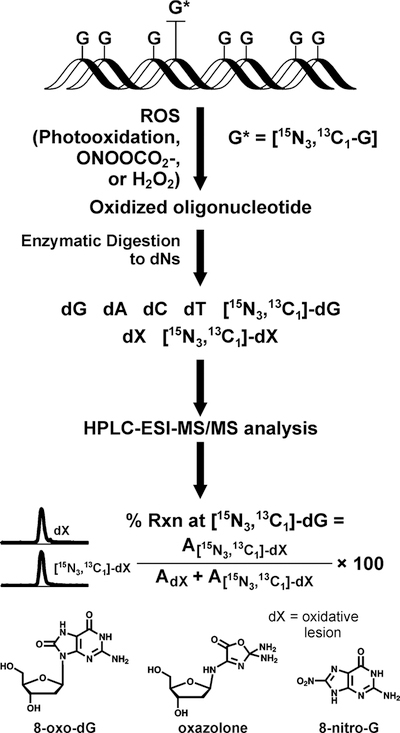

Our experimental strategy to quantify Z, OG, and 8-NO2-G adducts originating from specific guanine bases within DNA duplexes relies on the stable isotope labeling approach (ILD-MS) developed in our laboratory (Scheme 1) (16,43). A series of DNA oligomers were constructed representing a region of K-ras exon 1 containing frequently mutated codon 12. In each of them, a single guanine base was replaced with a stable isotope tagged guanine (15N3,13C1-dG) (Table 1). Following annealing to the complementary strand, site-specifically labeled DNA duplexes were subjected to riboflavin mediated photooxidation, peroxynitrite treatment, or incubated with hydrogen peroxide in the presence of ascorbic acid to induce hydroxyl radicals. The resulting oxidized DNA was enzymatically digested to 2ʹ-deoxyribonucleosides under conditions that led to quantitative release of 8-nitro-G as a free base adduct. Relative amounts of oxazolone, 8-oxo-dG, and 8-nitro-G formed at each site of interest were determined by isotope ratio HPLC-ESI-MS/MS (Scheme 2 and Figure 1). Any nucleobase lesions originating from isotopically labeled G carry the 15N,13C label and undergo a characteristic mass shift, making it possible to quantify the extent of adduct formation at that site by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS (16). Exact patterns of Z, OG, and 8-NO2-G formation within K-ras derived duplexes were established by sequentially replacing each guanine of interest with 15N3,13C1-dG (Table 1).

Scheme 1.

Strategy for quantitation of oxidative guanine lesions originating from specific sites within DNA sequence.

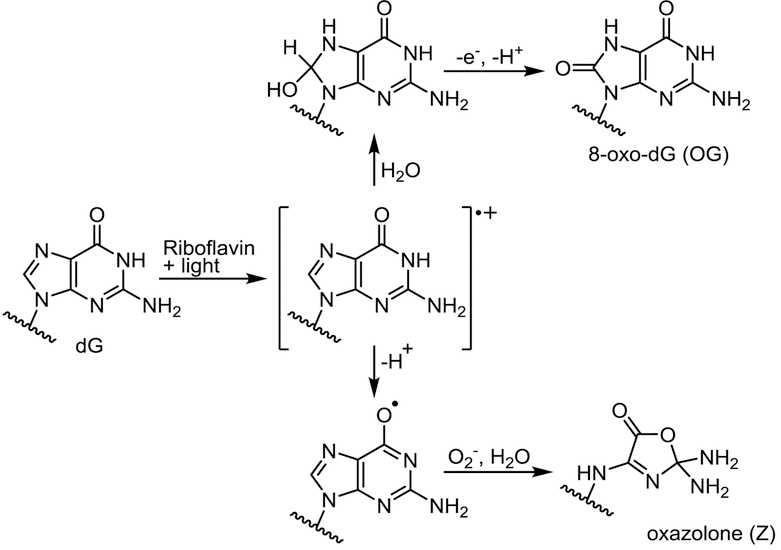

Scheme 2.

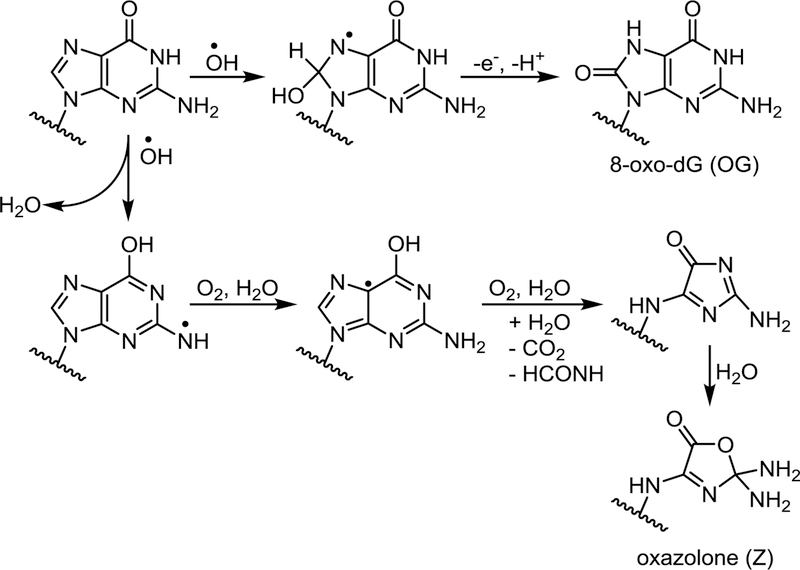

Guanine oxidation in the presence of riboflavin.

Figure 1.

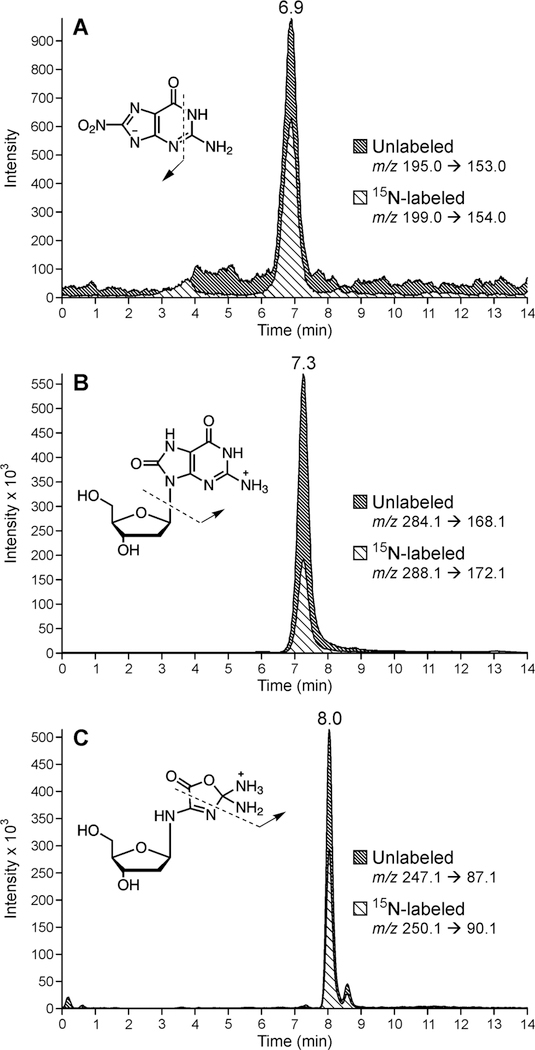

HPLC-ESI- MS/MS analysis 8-NO2-G (A) OG (B), and Z (C) in enzymatic hydrolysates of peroxynitrite-treated DNA duplex (G1G2AG3CTG4[15N3,13C1-G5]TG6G7CG8TAG9G10C). 15N-labeled signals correspond to adduct formation at G5 as compared to unlabeled adducts generated elsewhere in the sequence.

Representative HPLC-ESI--MS/MS traces of 15N3,13C1-8-NO2-G and 8-NO2-G adducts resulting from nitrosoperoxycarbonate treatment of a site-specifically labeled DNA duplex (GGAGCTG[15N3,13C1-G]TGGCGTAGGC) are shown in Figure 1. Signals corresponding to 8-NO2-G and 15N3,13C1-8-NO2-G are observed at m/z 195.1 → m/z 153.1 and m/z 199.1 → m/z 154.1, respectively (Figure 1A). The extent of adduct formation at the isotopically labeled site can be calculated directly from the areas under the HPLC-ESI-MS/MS peaks corresponding to the labeled and unlabeled 8-NO2-G (Scheme 1). Site-specific formation of OG and Z adducts was analyzed analogously by following MS/MS transitions m/z 284.1 → m/z 168.0 (OG), m/z 288.1 → m/z 172.0 (15N3,13C1-OG), m/z 247.1 → m/z 87.2 (Z) and m/z 250.1 → m/z 90.1 (15N2,13C1-Z), respectively (Figure 1B,C) (16). By repeating the experiment using DNA duplexes labeled at specific positions, it was possible to determine the relative amount adduct formation at each guanine of interest along the DNA duplex.

Development of optimal oxidation conditions.

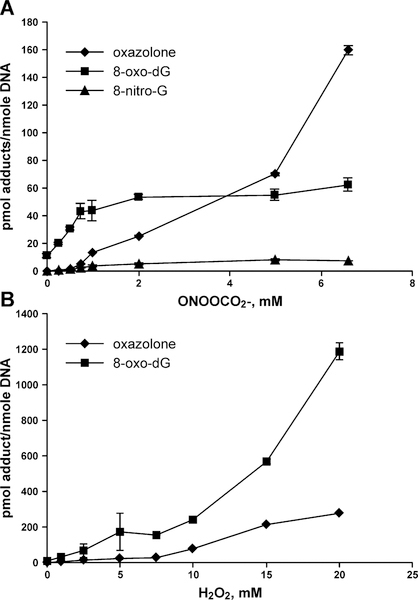

Preliminary experiments were conducted with unlabeled DNA duplexes to identify optimal oxidation conditions that lead to sufficient adduct numbers while maintaining sequence selectivity for DNA oxidation. We define “optimal conditions” as the lowest oxidant concentration that leads to quantifiable amounts of adducts at all positions of DNA duplex, including unfavorable oxidation sites. HPLC-ESI-MS/MS experiments have revealed that following treatment with 1 mM peroxynitrite, ~ 4.4% of total DNA strands contained 8-oxo-dG, ~1.3% of strands carried Z, and ~0.4% contained 8-NO2-G (Figure 2A). Treatment with 12 mM ascorbic acid/3.5 mM H2O2 (45) for 4 hours generated 8-oxo-dG in ~11% of total DNA strands and Z in ~ 1.5% of strands (Figure 2B). We previously established that photooxidation in the presence of riboflavin for 20 min induced 8-oxo-dG in ~ 4% of strands and Z in ~ 2% of strands (16). These conditions were selected for our experiments because they produced sufficient adduct numbers for HPLC-ESI-MS/MS quantitation at all sites, including low reactivity sites, while keeping the overall oxidation levels as low as possible to preserve DNA sequence selectivity.

Figure 2.

Concentration-dependent formation of OG, Z, and 8-NO2-G in dsDNA subjected to oxidation in the presence of peroxynitrite (A) and H2O2/ascorbate (B).

Sequence-dependent formation of OG, Z, and 8-NO2-G.

Riboflavin-mediated photooxidation.

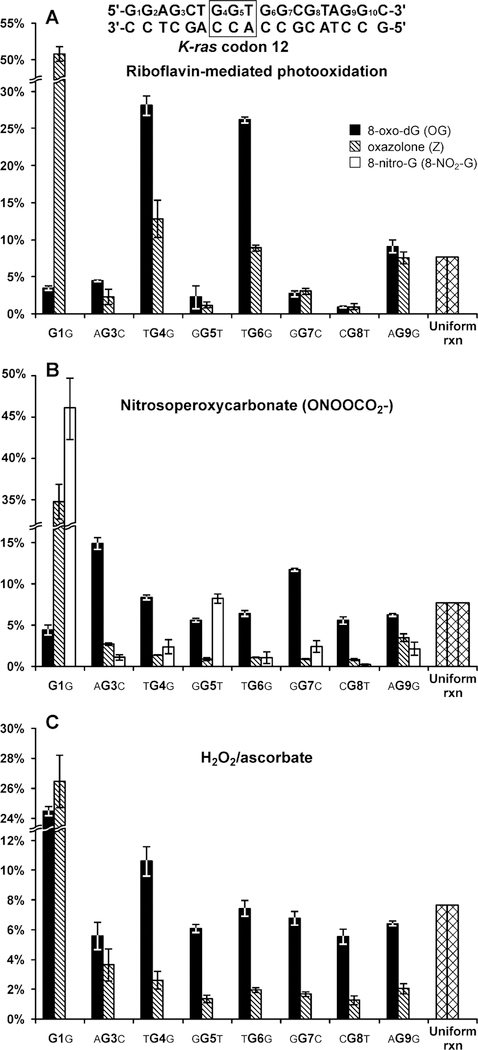

Site-specifically labeled DNA 18-mers (Table 1) were subjected to photooxidation in the presence of photosensitized riboflavin, and the extent of OG and Z formation at each site (G1-G9) was determined by ILD-MS as described above (Scheme 1, Figure 1). In an event of a random reaction, each of the 13 guanines present in this duplex should give rise to 7.7% of total adducts (100%/13; “uniform reaction” bars in Figure 3A). With an exception of terminal guanine (G1), similar numbers of OG adducts originated from all guanine bases when single stranded K-ras oligomer was subjected to photooxidation (Supplementary Figure S1). In contrast, significant sequence effects were observed for double stranded DNA of the same sequence. OG adducts were preferentially formed at G4 (TGG, 28.1%), G6 (TGG, 26.2%), and G9 (AGG, 9.2%), with these locations giving rise to over 63% of the total OG adducts formed (black bars in Figure 3A). By comparison, OG formation at G1, G3, G5, G7, and G8 was less efficient (< 5% of total reaction, black bars in Figure 3A). These results indicate that Watson-Crick base pairing with the complementary strand and π-π stacking between neighboring bases are required for the observed sequence specificity. The same guanine bases within GG repeats were also targeted for Z formation, accounting for 12.8, 8.9, and 7.6% of total adducts at G4, G6, and G9, respectively (striped bars in Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Distribution of OG and Z lesions along K-ras-derived DNA duplex following riboflavin mediated photooxidation (A), treatment with nitrosoperoxycarbonate (B) and hydrogen peroxide/ascorbate (C).

The elevated OG and Z formation at G4 (TGG), G6 (TGG), and G9 (AGG) is consistent with low redox potential of these nucleobases (6.52, 6.52, and 6.50 eV, respectively) (47), which are located at 5’ guanine in a runs of two Gs (48,49). In contrast, the sites of low reactivity (G3, G5, G7, and G8) are characterized by higher ionization potentials (7.01, 6.59, 6.63, and 6.91 eV, respectively) (47). One notable exception is the 5’-terminal guanine G1, which gave rise to over 50% of total Z adducts, but less than 3% of total OG adducts (Figure 3A). This may be rationalized by different fate of guanine radical cations produced at the end of duplexes (see below).

Nitrosoperoxycarbonate mediated oxidation.

We next examined sequence specificity for guanine oxidation in the presence of nitrosoperoxycarbonate, a key reactive species generated from peroxynitrite and carbon dioxide under inflammatory conditions (50–52). The patterns of OG and Z formation following treatment with ONOOCO2- were drastically different from those observed for riboflavin-mediated photooxidation (compare Figures 3A and 3B). While photooxidation targeted G4 (TGG) and G6 (TGG) (Figure 3A), OG formation following ONOOCO2- treatment was most efficient at G3 (AGC, 14.9%) and G7 (GGC, 11.8%). These two guanines are characterized by relatively high redox potential (7.01 and 6.63 eV, respectively) (47).

A different trend was observed for Z, which was formed inefficiently at all “internal” guanines examined (G3, G4, G5, G6, G8, G9). Instead, Z was overproduced at duplex ends, with 34.7% of total adducts originating from G1 (Figure 3B). G1 was also targeted for oxidation is ss DNA (Fig. S1B). The pattern of 8-NO2-G formation was similar to that observed for Z, with 46.0% of 8-NO2-G preferentially formed at G1 (white bars in Figure 3B). These results reveal striking differences between the patterns of OG and Z adduct formation following treatment with ONOOCO2-.

Hydroxyl radical-mediated oxidation.

Hydroxyl radicals were generated from hydrogen peroxide and ascorbate as described by Nappi and Vass (45). Unlike our results for other two reactive oxygen species, •OH-mediated formation of OG adducts within K-ras derived DNA duplexes showed little sequence specificity, with most of the internal Gs giving rise to similar adduct numbers (Figure 3C). The yields of Z were low at all internal guanine bases tested. However, enhanced formation of both OG and Z was observed at duplex ends (24.4% and 26.5% of total adducts at G1, Figure 3C).

DISCUSSION

Recent studies within the framework of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) have revealed that K-ras is among the most frequently mutated genes in human cancer, with activating mutations of K-ras codon 12 and 13 found in colon and rectal carcinoma, uterine endometrial carcinoma, and lung adenocarcinoma (53). Specifically, K-ras codon 12 mutations (GGT → TGT, GTT, GAT) are observed in 24 – 56% of adenocarinomas of the lung (54–56). In normal cells, KRAS protein is essential to the regulation of cellular growth and development (55). However, point mutations within K-ras codons 12, 13, or 61 activate this protooncogene, leading to uncontrolled cell growth, a loss of cell differentiation, and malignant transformation (57).

The majority of lung cancer cases (> 80%) are induced by cigarette smoking. It has been hypothesized that smoking-mediated oxidative degradation of DNA contributes to the development of smoking-mediated lung cancer (58,59). Cigarette tar contains phenolic and polyphenolic compounds which can become sources of the superoxide anion radical (O2•-) via redox cycling (58). O2•- can undergo dismutation to form hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which is converted to hydroxyl radicals (•OH) via Fe2+-mediated Fenton reaction (1). Tobacco smoke also contains high concentrations of nitric oxide (•NO) (>300 ppm) (60,61). •NO combines with O2•- to form peroxynitrite (ONOO-), a potent oxidizing and nitrating agent (62,63). Peroxynitrite can undergo homolysis to ∙OH and nitrogen dioxide (∙NO2) or can react with carbon dioxide to yield nitrosoperoxycarbonate (ONOOCO2─). The latter rapidly decomposes to carbonate radical (CO3•-) and ∙NO2 (30,51,62,64), which readily react with DNA to form a range of guanine lesions including 8-nitro-G, 8-oxo-dG, and oxazolone (2,65–67).

If formed within K-ras codons 12 and 13, oxidative guanine lesions can be misread by DNA polymerases, contributing to initiating mutations within this important protooncogene (6,7,66–68). However, it is not known to what extent codons 12 and 13 are targeted by reactive oxygen species and what nucleobase lesions are formed. Previous studies have relied on gel electrophoresis (30,31,69), next generation sequencing, and nanopore methodologies (70–72) to detect oxidative damage within DNA duplexes. Although these methodologies enable mapping DNA oxidation along broad genomic regions, they provide little information about adduct structures.

The goal of the present work was to quantify the formation of structurally defined DNA lesions (OG, Z, and 8-NO2-G) at specific guanine bases within K-ras derived DNA duplexes (5’-G1G2AG3CTG4G5TG6G7 CG8TAG9 G10C-3’; codon 12 = G4G5T) following treatment with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. We took advantage of a new stable isotope labeling of DNA-mass spectrometry strategy developed in our laboratory (IDL-MS) because it provides accurate quantitation of specific DNA lesions formed at each site of interest (16,33,34).

Three types of oxidative treatments were chosen for the present study of DNA sequence effects on guanine oxidation: riboflavin-mediated photooxidation, treatment with nitrosoperoxycarbonate, and exposure to hydroxyl radicals generated from H2O2/ascorbate. Riboflavin is a typical triplet-excited Type I photosensitizer previously used in many previous studies of DNA oxidation (16,21,48,69,73–77). Nitrosoperoxycarbonate (ONOOCO2-) is a product of peroxynitrite reaction with carbon dioxide and is considered the chemical mediator of inflammation (78–80). Hydroxyl radicals (HO•) are highly reactive species that are formed endogenously via Fenton reaction between hydrogen peroxide and ferrous iron (Fe 2+) (81). Hydrogen peroxide is a product of superoxide dismutase-mediated reaction of superoxide anions, which is commonly found in vivo as a byproduct of oxidative metabolism (23). The three oxidants selected for this study engage in DNA oxidation via distinct mechanisms (Schemes 2–4) and were anticipated to target different sites within DNA duplex.

Scheme 4.

Guanine oxidation in the presence of hydroxyl radicals.

Riboflavin-mediated photooxidation of K-ras derived DNA duplexes resulted in non-random formation of oxidized bases, with both OG and Z showing a preference for the 5’-G in GG repeats in internal regions of the duplex (G4 and G6 in Figure 3A) (16,47,82). Photosensitization-mediated oxidation of DNA gives rise to guanine radical cation (G•+), which can undergo nucleophilic addition of water at the C8 position to generate OG or deprotonation to form the guanyl radical (G(-H)•), which gives rise to Z (Scheme 2) (75,83,84). Preferential oxidation of 5’-G in GG runs following photooxidation is likely a result of their relatively low ionization potential, leading to electron hole migration to these sites (48,69). This is consistent with earlier reports that GG repeats are among the most electron-rich sites in B-form of DNA (48) and may act thermodynamic “sinks” for oxidative damage following long-range charge transport from other sites in the helix (GG stacking rule) (12,30,48,69,85).

In addition, Z (but not OG) adducts were overproduced at duplex termini (G1 in Figure 3A), probably a result of preferential deprotonation of G•+ to G(-H)• at partially separated duplex ends. Rokhlenko et al. have shown that G:C base pairing in double stranded DNA inhibited the full release of the proton from G•+, causing G(-H)• to retain some of the cationic characteristics of G•+ (84). These authors reported that the [G(-H)•:H+C ↔ G•+:C] equilibrium had a lifetime of ~ 0.22 ms, compared ~ 50 ns for free G•+ (84,86). The stabilization of G•+ was not observed at duplex ends where the double stranded character of DNA is compromised, resulting in the rapid deprotonation of G•+ and its ultimate conversion to Z rather than to OG (Scheme 2, Figure 3A) (30,84,86).

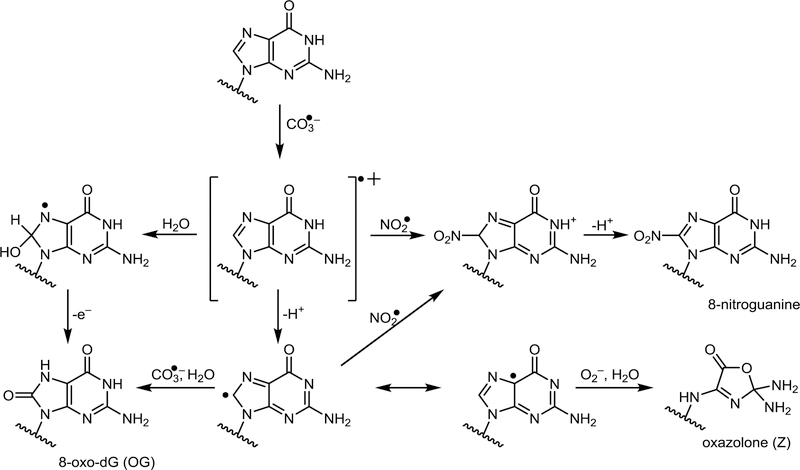

Treatment of site-specifically labeled K-ras DNA duplexes with nitrosoperoxycarbonate (ONOOCO2-) exhibited a different sequence specificity, with G3, and G7 (sites of relatively high redox potential) (49) preferentially forming OG and G1 giving rise to the greatest numbers of NO2-G and Z (Figure 3B). These drastic differences between the patterns of adduct formation may be explained by the chemistry of DNA oxidation in the presence of ONOOCO2- and its homolysis products, carbonate radical anion (CO3•-) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2•) (51,79). Electron abstraction from G by CO3•- produces G•+, which can be hydrated to form OG, deprotonated to form Z, or react with •NO2 to form 8-NO2-G (Scheme 3) (87–94). As noted previously by Dedon et al. (30). ONOOCO2- mediated oxidation does not take place at the sites of lowest redox potential, but rather is dependent on solvent accessibility of guanine bases and the extent of double stranded character.

Scheme 3.

Guanine oxidation in the presence of ONOOCO2.

The hydrophobic interior regions of dsDNA are not solvent accessible, therefore the initial radical attack on dG must occur either in the major (C8 position exposed) or minor (N2 position exposed) grooves of DNA. Small radical species such as •OH, CO3•-, and •NO2 will form hydrogen bonds with the surrounding water. In a bulk solvent, it takes between 1 and 5 ps to break and reform hydrogen bonds allowing solute molecules to randomly diffuse through the solvent (95). Compared to the bulk solvent, the water molecules in the grooves of dsDNA are more ordered, especially in the minor groove (95–98). The re-ordering of hydrogen bonds is slower in the grooves, with more than a 5-fold reduction in speed in the minor groove, in addition to constraints on solute orientation, which can slow down or inhibit reaction of radical with DNA (95,98). The loss of duplex character of DNA at the ends of the strand causes a widening of the grooves which disrupts the water layer which accelerates the ability of solutes to approach the DNA and removed the constraints on orientation (95,97,98). Therefore small radical species such as CO3•- can easily approach at these locations, resulting in enhanced oxidative nucleobase damage at duplex ends (G1 in Figure 3B).

In contrast to our results for photooxidation (Figure 3A) and nitrosoperoxycarbonate (Figure 3B), hydroxyl radical-mediated guanine oxidation exhibited little sequence selectivity (Figure 3C) (99). Unlike the former two ROS, •OH does not produce guanine radical cation intermediates (G•+), but instead directly adds to the C8 position of dG (Scheme 4). Due to their extreme reactivity, hydroxyl radicals can on average diffuse no more than 70 Å in a cell before reacting with biomolecules (100). Hydroxyl radical-mediated “footprinting” has been exploited to reveal DNA-protein and DNA-small molecule interactions (99,101,102). Hydroxyl radicals can directly add to the C8 position of guanine producing 8-OH-G• radical, which further oxidizes to OG (100,103). Alternatively, HO• can abstract a hydrogen atom from guanine to yield the G(-H)• radical, which can further oxidize to form Z (Scheme 3) (100,103). Previous reports suggested that DNA sequence has little, if any, effect on •OH mediated oxidation (102,104,105). Therefore, solvent accessibility to •OH appears to be the driving force defining the reactivity patterns and leading to the preferential production of both OG and Z at duplex ends (Figure 3C).

Preferential formation of OG rather than Z in the interior regions of the DNA duplex following treatment with H2O2/ascorbate (Figure 3C) may be explained by their mechanism of formation (Scheme 4), which involves •OH attack at the C8 and the N2 positions of guanine, respectively. The N2 position of dG is buried in the minor groove under an ordered layer of water and is therefore less accessible than the C8 position which faces the major groove where the water is less structured and without the constraints to solute orientation (95,97,98) Therefore, in dsDNA, •OH attack at the C8 position to form 8-OH-G• is more favorable than the abstraction of a hydrogen atom from the N2 position (Scheme 4), leading to preferential formation of OG (106). In regions of partially single stranded DNA such as duplex ends, the water layer in the minor groove break down, resulting in a lower energy barrier for •OH attack at guanine N2 and an increased formation of Z (95–98).

Our observation that OG lesions are preferentially formed at the first guanine of K-ras codon 12 under conditions of one electron oxidation (GGT, G4 in Figure 3A) is of potential significance because this site is commonly mutated in lung cancer (G →T) (54,107–109). Site specific mutagenesis and polymerase bypass studies have revealed that OG and its secondary oxidation products primarily cause G to T transversions (25,68,110). Therefore, oxidative damage induced by smoking and inflammation is a possible contributor to the induction of cancer-initiating mutations at K-ras codon 12. However, it should be noted that the reactivity of DNA bases towards ROS in cellular systems is anticipated to be mediated by chromatin structure, and the mutational spectra in tumors will be further affected by mutant selection for growth.

In addition, our results suggest that Z and 8-NO2-G adducts are formed in preference to OG in genomic regions with reduced double stranded character, e.g. in DNA that is undergoing replication, actively transcribed regions, and at guanines paired with abasic sites. Previous studies have shown that 8-NO2-G preferentially pairs with dA during DNA replication, giving rise to G to T transversions, while Z causes G to C transversions (66,89,111,112). This may lead to increased mutagenesis within actively transcribed regions, unless DNA repair machinery is recruited to remove the damage.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the U.S. National Cancer Institute (CA-095039). The sponsor had no role in the design, data collection, or writing of this report, or in the decision to submit this article for publication.

We thank Dr. Guru Madugundu (UMN) for his helpful comments on the paper and Robert Carlson (UMN) for help with figures and manuscript formatting.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Z

Z, 2,2-diamino-4-[(2-deoxy-β-D-erythropentofuranosyl)amino]-5(2H)-oxazolone

- OG

8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-deoxyguanosine

- 8-NO2-G

8-nitroguanine

- MeC

5-methyl-2ʹ-deoxycytidine

- ILD-MS

isotope labeling of DNA-mass spectrometry

- SPE

solid phase extraction

- DMHA

N,N-dimethylhexylamine

REFERENCES

- 1.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JM, Cross CE. Free radicals, antioxidants, and human disease: where are we now? J Lab Clin Med 1992;119:598–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marnett LJ. Oxyradicals and DNA damage. Carcinogenesis 2000;21:361–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett MR. Reactive oxygen species and death: oxidative DNA damage in atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2001;88:648–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canella KA, Diwan BA, Gorelick PL, Donovan PJ, Sipowicz MA, Kasprzak KS, et al. Liver tumorigenesis by Helicobacter hepaticus: considerations of mechanism. In Vivo 1996;10:285–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malins DC, Holmes EH, Polissar NL, Gunselman SJ. The etiology of breast cancer. Characteristic alterations in hydroxyl radical-induced DNA base lesions during oncogenesis with potential for evaluating incidence risk. Cancer 1993;71:3036–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenberg MM. In vitro and in vivo effects of oxidative damage to deoxyguanosine. Biochem Soc Trans 2004;32:46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paz-Elizur T, Krupsky M, Blumenstein S, Elinger D, Schechtman E, Livneh Z. DNA repair activity for oxidative damage and risk of lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2003;95:1312–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helbock HJ, Beckman KB, Shigenaga MK, Walter PB, Woodall AA, Yeo HC, et al. DNA oxidation matters: the HPLC-electrochemical detection assay of 8-oxo-deoxyguanosine and 8-oxo-guanine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95:288–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malins DC. Free radicals and breast cancer. Environ Health Perspect 1996;104:1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prat F, Houk KN, Foote CS. Effect of guanine stacking on the oxidation of 8-oxoguanine in B-DNA. J Am Chem Soc 1998;120:845–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neeley WL, Essigmann JM. Mechanisms of formation, genotoxicity, and mutation of guanine oxidation products. Chem Res Toxicol 2006;19:491–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kino K, Saito I, Sugiyama H. Product analysis of GG-specific photooxidation of DNA via electron transfer: 2-aminoimidazolone as a major guanine oxidation product. J Am Chem Soc 1998;120:7373–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirakawa K, Yoshida M, Oikawa S, Kawanishi S. Base oxidation at 5’ site of GG sequence in double-stranded DNA induced by UVA in the presence of xanthone analogues: relationship between the DNA-damaging abilities of photosensitizers and their HOMO energies. Photochem Photobiol 2003;77:349–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirakawa K, Suzuki H, Oikawa S, Kawanishi S. Sequence-specific DNA damage induced by ultraviolet A-irradiated folic acid via its photolysis product. Arch Biochem Biophys 2003;410:261–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yun BH, Lee YA, Kim SK, Kuzmin V, Kolbanovskiy A, Dedon PC, et al. Photosensitized oxidative DNA damage: from hole injection to chemical product formation and strand cleavage. J Am Chem Soc 2007;129:9321–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ming X, Matter B, Song M, Veliath E, Shanley R, Jones R, et al. Mapping structurally defined guanine oxidation products along DNA duplexes: influence of local sequence context and endogenous cytosine methylation. J Am Chem Soc 2014;136:4223–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cadet J, Treoule R. Comparative study of oxidation of nucleic acid components by hydroxyl radicals, singlet oxygen and superoxide anion radicals. Photochem Photobiol 1978;28:661–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Douki T, Cadet J. Peroxynitrite mediated oxidation of purine bases of nucleosides and isolated DNA. Free Radic Res 1996;24:369–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo W, Muller JG, Rachlin EM, Burrows CJ. Characterization of spiroiminodihydantoin as a product of one-electron oxidation of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine. Org Lett 2000;2:613–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niles JC, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Spiroiminodihydantoin is the major product of the 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine reaction with peroxynitrite in the presence of thiols and guanosine photooxidation by methylene blue. Org Lett 2001;3:963–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo W, Muller JG, Rachlin EM, Burrows CJ. Characterization of hydantoin products from one-electron oxidation of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine in a nucleoside model. Chem Res Toxicol 2001;14:927–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravanat JL, Cadet J. Reaction of singlet oxygen with 2’-deoxyguanosine and DNA. Isolation and characterization of the main oxidation products. Chem Res Toxicol 1995;8:379–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cadet J, Berger M, Douki T, Ravanat JL. Oxidative damage to DNA: formation, measurement, and biological significance. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 1997;131:1–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yermilov V, Rubio J, Becchi M, Friesen MD, Pignatelli B, Ohshima H. Formation of 8-nitroguanine by the reaction of guanine with peroxynitrite in vitro. Carcinogenesis 1995;16:2045–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson PT, Delaney JC, Gu F, Tannenbaum SR, Essigmann JM. Oxidation of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine affords lesions that are potent sources of replication errors in vivo. Biochemistry 2002;41:914–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leipold MD, Muller JG, Burrows CJ, David SS. Removal of hydantoin products of 8-oxoguanine oxidation by the Escherichia coli DNA repair enzyme, FPG. Biochemistry 2000;39:14984–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tretyakova NY, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Peroxynitrite-induced secondary oxidative lesions at guanine nucleobases: chemical stability and recognition by the Fpg DNA repair enzyme. Chem Res Toxicol 2000;13:658–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krokeide SZ, Laerdahl JK, Salah M, Luna L, Cederkvist FH, Fleming AM, et al. Human NEIL3 is mainly a monofunctional DNA glycosylase removing spiroimindiohydantoin and guanidinohydantoin. DNA Repair (Amst) 2013;12:1159–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tretyakova NY, Burney S, Pamir B, Wishnok JS, Dedon PC, Wogan GN, et al. Peroxynitrite-induced DNA damage in the supF gene: correlation with the mutational spectrum. Mutat Res 2000;447:287–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Margolin Y, Cloutier JF, Shafirovich V, Geacintov NE, Dedon PC. Paradoxical hotspots for guanine oxidation by a chemical mediator of inflammation. Nat Chem Biol 2006;2:365–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Margolin Y, Shafirovich V, Geacintov NE, DeMott MS, Dedon PC. DNA sequence context as a determinant of the quantity and chemistry of guanine oxidation produced by hydroxyl radicals and one-electron oxidants. J Biol Chem 2008;283:35569–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Margolin Y, Dedon PC. A general method for quantifying sequence effects on nucleobase oxidation in DNA. Methods Mol Biol 2010;610:325–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tretyakova N Sequence distribution of nucleobase adducts studied by isotope labeling of DNA-mass spectrometry In: Banoub JH, Limbach PA, editors. Mass Spectrometry of Nucleosides and Nucleic Acids. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tretyakova N, Matter B, Jones R, Shallop A. Formation of benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide-DNA adducts at specific guanines within K-ras and p53 gene sequences: stable isotope-labeling mass spectrometry approach. Biochemistry 2002;41:9535–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tretyakova N, Villalta PW, Kotapati S. Mass spectrometry of structurally modified DNA. Chem Rev 2013;113:2395–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tretyakova N, Goggin M, Sangaraju D, Janis G. Quantitation of DNA adducts by stable isotope dilution mass spectrometry. Chem Res Toxicol 2012;25:2007–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao H, Pagano AR, Wang W, Shallop A, Gaffney BL, Jones RA. Use of a 13C atom to differentiate two 15N-labeled nucleosides. Syntheses of [15NH2]-Adenosine, [1,NH2-15N2]- and [2-13C-1,NH2-15N2]-Guanosine, and [1,7,NH2-15N3]- and [2-13C-1,7,NH2-15N3]-2’-Deoxyguanosine. J Org Chem 1997;62:7832–5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shallop AJ, Gaffney BL, Jones RA. Use of 13C as an indirect tag in 15N specifically labeled nucleosides. Syntheses of [8-13C-1,7,NH2-15N3]adenosine, -guanosine, and their deoxy analogues. J Org Chem 2003;68:8657–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matter B, Malejka-Giganti D, Csallany AS, Tretyakova N. Quantitative analysis of the oxidative DNA lesion, 2,2-diamino-4-(2-deoxy-β-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl)amino]-5(2H)-oxazolone (oxazolone), in vitro and in vivo by isotope dilution-capillary HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Nucleic Acids Res 2006;34:5449–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kennedy LJ, Moore K, Caulfield JL, Tannenbaum SR, Dedon PC. Quantitation of 8-oxoguanine and strand breaks produced by four oxidizing agents. Chem Res Toxicol 1997;10:386–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen H-JC, Chen Y-M, Wang T-F, Wang K-S, Shiea J. 8-nitroxanthine, an adduct derived from 2’-deoxyguanosine or DNA reaction with nitryl chloride. Chem Res Toxicol 2001;14:536–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bodepudi V, Shibutani S, Johnson F. Synthesis of 2’-deoxy-7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanosine and 2’-deoxy-7,8-dihydro-8-oxoadenosine and their incorporation into oligomeric DNA. Chem Res Toxicol 1992;5:608–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matter B, Wang G, Jones R, Tretyakova N. Formation of diastereomeric benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide-guanine adducts in p53 gene-derived DNA sequences. Chem Res Toxicol 2004;17:731–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tretyakova N, Matter B, Ogdie A, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Locating nucleobase lesions within DNA sequences by MALDI-TOF mass spectral analysis of exonuclease ladders. Chem Res Toxicol 2001;14:1058–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nappi AJ, Vass E. Hydroxyl radical production by ascorbate and hydrogen peroxide. Neurotoxicity Research 2000;2:343–55. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cadet J, Berger M, Buchko GW, Joshi PC, Raoul S, Ravanat J- L. 2,2-Diamino-4-[(3,5-di-O-acetyl-2-deoxy-beta-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl)amino]-5-(2H)-oxazolone - A novel and predominant radical oxidation-product of 3’,5’-di-O-acetyl-2’-deoxyguanosine. J Am Chem Soc 1994;116:7403–4. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saito I, Nakamura T, Nakatani K, Yoshioka Y, Yamaguchi K, Sugiyama H. Mapping of the hot spots for DNA damage by one-electron oxidation: Efficacy of GG doublets and GGG triplets as a trap in long-range hole migration. J Am Chem Soc 1998;120:12686–7. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saito I, Takayama M, Nakamura T, Sugiyama H, Komeda Y, Iwasaki M. The most electron-donating sites in duplex DNA: guanine-guanine stacking rule. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser 1995;34:191–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saito I, Takayama M, Sugiyama H, Nakatani K, Tsuchida A, Yamamoto M. Photoinduced DNA Cleavage via Electron Transfer: Demonstration That Guanine Residues Located 5’ to Guanine Are the Most Electron-Donating Sites. J Am Chem Soc 1995;117:6406–7. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shafirovich V, Dourandin A, Huang W, Geacintov NE. The carbonate radical is a site-selective oxidizing agent of guanine in double-stranded oligonucleotides. J Biol Chem 2001;276:24621–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Radi R. Peroxynitrite reactions and diffusion in biology. Chem Res Toxicol 1998;11:720–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lymar SV, Hurst JK. Rapid reaction between peroxynitrite ion and carbon dioxide: implications for biological activity. J Am Chem Soc 1995;117:8867–8. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, Lu C, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature 2013;502:333–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rodenhuis S, Slebos RJ, Boot AJ, Evers SG, Mooi WJ, Wagenaar SS, et al. Incidence and possible clinical significance of K-ras oncogene activation in adenocarcinoma of the human lung. Cancer Res 1988;48:5738–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koera K, Nakamura K, Nakao K, Miyoshi J, Toyoshima K, Hatta T, et al. K-Ras is essential for the development of the mouse embryo. Oncogene 1997;15:1151–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Slebos RJ, Rodenhuis S. The molecular genetics of human lung cancer. Eur Respir J 1989;2:461–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barbacid M ras genes. Annu Rev Biochem 1987;56:779–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gackowski D, Speina E, Zielinska M, Kowalewski J, Rozalski R, Siomek A, et al. Products of oxidative DNA damage and repair as possible biomarkers of susceptibility to lung cancer. Cancer Research 2003;63:4899–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loft S, Svoboda P, Kawai K, Kasai H, Sorensen M, Tjonneland A, et al. Association between 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine excretion and risk of lung cancer in a prospective study. Free Radic Biol Med 2012;52:167–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Norman V, Keith CH. Nitrogen oxides in tobacco smoke. Nature 1965;205:915–6. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cueto R, Pryor WA. Cigarette smoke chemistry: conversion of nitric oxide to nitrogen dioxide and reactions of nitrogen oxides with other smoke components as studied by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Vibrational Spectroscopy 1994;7:97–111. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Radi R, Peluffo G, Alvarez MN, Naviliat M, Cayota A. Unraveling peroxynitrite formation in biological systems. Free Radic Biol Med 2001;30:463–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peluffo G, Calcerrada P, Piacenza L, Pizzano N, Radi R. Superoxide-mediated inactivation of nitric oxide and peroxynitrite formation by tobacco smoke in vascular endothelium: studies in cultured cells and smokers. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2009;296:H1781–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pryor WA, Prier DG, Church DF. Electron-spin resonance study of mainstream and sidestream cigarette smoke: nature of the free radicals in gas-phase smoke and in cigarette tar. Environ Health Perspect 1983;47:345–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hiraku Y Formation of 8-nitroguanine, a nitrative DNA lesion, in inflammation-related carcinogenesis and its significance. Environ Health Prev Med 2010;15:63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ohshima H, Sawa T, Akaike T. 8-nitroguanine, a product of nitrative DNA damage caused by reactive nitrogen species: formation, occurrence, and implications in inflammation and carcinogenesis. Antioxid Redox Signal 2006;8:1033–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Valko M, Rhodes CJ, Moncol J, Izakovic M, Mazur M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chem Biol Interact 2006;160:1–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yu DS, Berlin JA, Penning TM, Field J. Reactive oxygen species generated by PAH o-quinones cause change-in-function mutations in p53. Chemical Research in Toxicology 2002;15:832–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burrows CJ, Muller JG. Oxidative nucleobase modifications leading to strand scission. Chem Rev 1998;98:1109–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.An N, Fleming AM, Burrows CJ. Human telomere G-quadruplexes with five repeats accommodate 8‑oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine by looping out the DNA damage. ACS chemical biology 2016;11:500–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhu J, Fleming AM, Orendt AM, Burrows CJ. pH-Dependent equilibrium between 5-guanidinohydantoin and iminoallantoin affects nucleotide insertion opposite the DNA lesion. J Org Chem 2016;81:351–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Riedl J, Fleming AM, Burrows CJ. Sequencing of DNA lesions facilitated by site-specific excision via base excision repair DNA glycosylases yielding ligatable gaps. J Am Chem Soc 2016;138:491–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoshioka Y, Kitagawa Y, Takano Y, Yamaguchi K, Nakamura T, Saito I. Experimental and theoretical studies on the selectivity of GGG triplets toward one-electron oxidation in B-form DNA. J Am Chem Soc 1999;121:8712–9. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Naseem I, Ahmad M, Hadi SM. Effect of alkylated and intercalated DNA on the generation of superoxide anion by riboflavin. Biosci Rep 1988;8:485–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kasai H, Yamaizumi Z, Berger M, Cadet J. Photosensitized formation of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine) in DNA by riboflavin: A nonsinglet oxygen mediated reaction. J Am Chem Soc 1992;114:9692–4. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gasparutto D, Ravanat JL, Gerot O, Cadet J. Characterization and chemical stability of photooxidized oligonucleotides that contain 2,2-diamino-4-[(2-deoxy-β-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl)amino]-5(2H)-oxazolone. J Am Chem Soc 1998;120:10283–6. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Douki T, Ravanat J-L, Angelov D, Wagner JR, Cadet J. Effects of duplex stability on charge-transfer efficiency within DNA. Top Curr Chem 2004;236:127–39. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lymar SV, Hurst JK. Role of compartmentation in promoting toxicity of leukocyte-generated strong oxidants. Chem Res Toxicol 1995;8:833–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lymar SV, Hurst JK. CO2-catalyzed one-electron oxidations by peroxynitrite: Properties of the reactive intermediate. Inorg Chem 1998;37:294–301. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Goldstein S, Czapski G. Formation of peroxynitrate from the reaction of peroxynitrite with CO2: Evidence for carbonate radical production. J Am Chem Soc 1998;120:3458–63. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Frelon S, Douki T, Favier A, Cadet J. Comparative study of base damage induced by gamma radiation and Fenton reaction in isolated DNA. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 2002:2866–70. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ito K, Inoue S, Yamamoto K, Kawanishi S. 8-Hydroxydeoxyguanosine formation at the 5’ site of 5’-GG-3’ sequences in double-stranded DNA by UV radiation with riboflavin. J Biol Chem 1993;268:13221–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reynisson J, Steenken S. DFT calculations on the electrophilic reaction with water of the guanine and adenine radical cations. A model for the situation in DNA. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2002;4:527–32. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rokhlenko Y, Cadet J, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Mechanistic aspects of hydration of guanine radical cations in DNA. J Am Chem Soc 2014;136:5956–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nunez ME, Rajski SR, Barton JK. Damage to DNA by long-range charge transport. Methods Enzymol 2000;319:165–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kobayashi K, Tagawa S. Direct observation of guanine radical cation deprotonation in duplex DNA using pulse radiolysis. J Am Chem Soc 2003;125:10213–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu N, Ban F, Boyd RJ. Modeling Competititve reaction mechanisms of peroxynitrite oxidation of guanine. J Phys Chem A 2006;110:9908–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shafirovich V, Mock S, Kolbanovskiy A, Geacintov NE. Photochemically catalyzed generation of site-specific 8-nitroguanine adducts in DNA by reaction of long-lived neutral gaunine radicals with nitrogen dioxide. Chem Res Toxicol 2002;15:591–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Agnihotri N, Mishra PC. Mutagenic product formation due to reaction of guanine radical cation with nitrogen dioxide. J Phys Chem B 2009;113:3129–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Agnihotri N, Mishra PC. Formation of 8-nitroguanine due to reaction between guanyl radical and nitrogen dioxide: catalytic role of hydration. J Phys Chem B 2010;114:7391–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat JL. One-electron oxidation of DNA and inflammation processes. Nature Chemical Biology 2006;2:348–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Joffe A, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. DNA lesions derived from the site selective oxidation of guanine by carbonate radical anions. Chem Res Toxicol 2003;16:1528–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rokhlenko Y, Geacintov NE, Shafirovich V. Lifetimes and reaction pathways of guanine radical cations and neutral guanine radicals in an oligonucleotide in aqueous solutions. J Am Chem Soc 2012;134:4955–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Misiaszek R, Crean C, Geacintov N, Shafirovich V. Combination of nitrogen dioxide radicals with 8-oxo-7,8-dihydoguanine and guanine radicals in DNA: Oxidation and Nitration End-Products. J Am Chem Soc 2005;127:2191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Laage D, Elsaesser T, Hynes JT. Water dynamics in the hydration shells of biomolecules. Chem Rev 2017;117:10694–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dickerson RE, Drew HR, Conner BN, Wing RM, Fratini AV, Kopka ML. The anatomy of A-, B-, and Z-DNA. Science 1982;216:475–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Duboue-Dijon E, Fogarty AC, Hynes JT, Laage D. Dynamical disorder in the DNA hydration shell. J Am Chem Soc 2016;138:7610–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nakano M, Tateishi-Karimata H, Tanaka S, Tama F, Miyashita O, Nakano S, et al. Local thermodynamics of the water molecules around single- and double-stranded DNA studied by grid inhomogeneous solvation theory. Chem Phys Lett 2016;660:250–5. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rokita SE, Romero-Fredes L. The ensemble reactions of hydroxyl radical exhibit no specificity for primary or secondary structure of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 1992;20:3069–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cadet J, Delatour T, Douki T, Gasparutto D, Pouget JP, Ravanat JL, et al. Hydroxyl radicals and DNA base damage. Mutat Res 1999;424:9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tullius TD. DNA footprinting with hydroxyl radical. Nature 1988;332:663–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tullius TD. Chemical ‘snapshots’ of DNA: using the hydroxyl radical to study the structure of DNA and DNA-protein complexes. Trends Biochem Sci 1987;12:297–300. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cadet J, Douki T, Ravanat JL. Oxidatively generated base damage to cellular DNA. Free Radic Biol Med 2010;49:9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tullius TD, Dombroski BA. Iron(II) EDTA used to measure the helical twist along any DNA molecule. Science 1985;230:679–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hertzberg RP, Dervan PB. Cleavage of DNA with methidiumpropyl-EDTA-iron(II): reaction conditions and product analyses. Biochemistry 1984;23:3934–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chatgilialoglu C, D’Angelantonio M, Guerra M, Kaloudis P, Mulazzani QG. A reevaluation of the ambident reactivity of the guanine moiety towards hydroxyl radicals. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2009;48:2214–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rodenhuis S, Slebos RJC. Clinical significance of ras oncogene activation in human lung cancer. Cancer Res 1992;52:2665s-9s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Slebos RJC, Hruban RH, Dalesio O, Mooi WJ, Offerhaus GJA, Rodenhuis S. Relationship between K-ras oncogene activation and smoking in adenocarcinoma of the human lung. J Natl Cancer Inst 1991;83:1024–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Westra WH, Slebos RJC, Offerhaus GJA, Goodman SN, Evers SG, Kensler TW, et al. K-Ras oncogene activation in lung adenocarcinomas from former smokers evidence that K-ras mutations are an early and irreversible event in the development of adenocarcinoma of the lung. Cancer 1993;72:432–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Breen AP, Murphy JA. Reactions of oxyl radicals with DNA. Free Radic Biol Med 1995;18:1033–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bhamra I, Compagnone-Post P, O’Neil IA, Iwanejko LA, Bates AD, Cosstick R. Base-pairing preferences, physicochemical properties and mutational behaviour of the DNA lesion 8-nitroguanine. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40:11126–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kino K, Takao M, Miyazawa H, Hanaoka F. A DNA oligomer containing 2,2,4-triamino-5(2H)-oxazolone is incised by human NEIL1 and NTH1. Mutat Res 2012;734:73–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.