Abstract

Background

Intramuscular fat (IMF) is one of the most important factors positively associated with meat quality. Triglycerides (TGs), as the main component of IMF, play an essential role in muscle lipid metabolism. This transcriptome analysis of pectoralis muscle tissue aimed to identify functional genes and biological pathways likely contributing to the extreme differences in the TG content of broiler chickens.

Results

The study included Jingxing-Huang broilers that were significantly different in TG content (5.81 mg/g and 2.26 mg/g, p < 0.01) and deposition of cholesterol also showed the same trend. This RNA sequencing analysis was performed on pectoralis muscle samples from the higher TG content group (HTG) and the lower TG content group (LTG) chickens. A total of 1200 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified between two groups, of which 59 DEGs were related to TG and steroid metabolism. The HTG chickens overexpressed numerous genes related to adipogenesis and lipogenesis in pectoralis muscle tissue, including the key genes ADIPOQ, CD36, FABP4, FABP5, LPL, SCD, PLIN1, CIDEC and PPARG, as well as genes related to steroid biosynthesis (DHCR24, LSS, MSMO1, NSDHL and CH25H). Additionally, key pathways related to lipid storage and metabolism (the steroid biosynthesis and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) signaling pathway) may be the key pathways regulating differential lipid deposition between HTG group and LTG group.

Conclusions

This study showed that increased TG deposition accompanying an increase in steroid synthesis in pectoralis muscle tissue. Our findings of changes in gene expression of steroid biosynthesis and PPAR signaling pathway in HTG and LTG chickens provide insight into genetic mechanisms involved in different lipid deposition patterns in pectoralis muscle tissue.

Keywords: Triglyceride metabolism, Steroid biosynthesis, Intramuscular fat, Pectoralis muscle tissue, Gene expression, Pathways, Chicken

Background

With the improvement of living standards, there is a gradual increase in consumer demand for meat quality, especially in China. Meat quality is a complex concept that includes appearance, sensory, hygienic and nutritional attributes [1]. Intramuscular fat (IMF) content is commonly used in livestock and poultry industry as an indicator of meat quality influencing tenderness, color, juiciness and flavor [2–5]. Chickens with higher IMF content usually have a higher level of consumer preference.

Given the effect of lipid deposition on poultry meat, many studies have investigated the control of IMF traits in chickens. Genome-wide association analysis, polymorphism analysis and “omics” data is a common approach to identify loci and candidate genes associated with IMF [6–8]. The differential deposition mechanism of IMF in different breeds, tissues and ages has also been studied. In our previous study, the effects of breed and age on IMF deposition were explored in Beijing-you chicken and Arbor Acres, and several differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (MYBPC1, CETP, GLTPD1 and SNX4) were identified for IMF developmental processes [9]. For Beijing-you and Cobb chicken, ACADL, ACAD9, HADHA and HADHB were identified as candidate biomarkers for IMF deposition [10]. Hub genes related to IMF deposition might be interfered by genetic background when the investigation involves various chicken breeds. Therefore, under the same genetic background, chickens with different IMF content are considered as a good model for studying the molecular mechanism of IMF deposition. Jingxing-Huang broiler, a high-quality chicken breed in China, has a higher capability of IMF deposition. Exploring the mechanism of IMF deposition in Jingxing-Huang chicken may contribute largely to improving meat quality and cultivating high-quality breed.

IMF is the amount of fat within muscles and consists mainly of triglycerides (TGs), but also contains phospholipids and cholesterol. As a complex trait, it is extremely difficult to accurately target key genes involved in IMF deposition. TGs, the most major component of IMF, are helpful to simplified phenotype and explore the underlying deposition mechanism of IMF. As a major factor in the regulation of energy metabolism, the synthesis and deposition of TG appear to be extremely important for energy metabolism and lipid deposition in muscle tissue [11]. Presently, although several studies have been reported on TG metabolism in chickens [12–14], little is known about the key genes and molecular mechanisms of TG metabolism in chicken pectoralis muscle tissue. In this study, 18 Jingxing-Huang female chickens with extremely different TG content were chosen for transcriptomic study aimed at identifying DEGs and investigating the underlying molecular mechanisms involved in alterations of lipid metabolism in pectoralis muscle tissue.

Results

Different lipid metabolism in pectoralis muscle tissue of HTG and LTG chickens

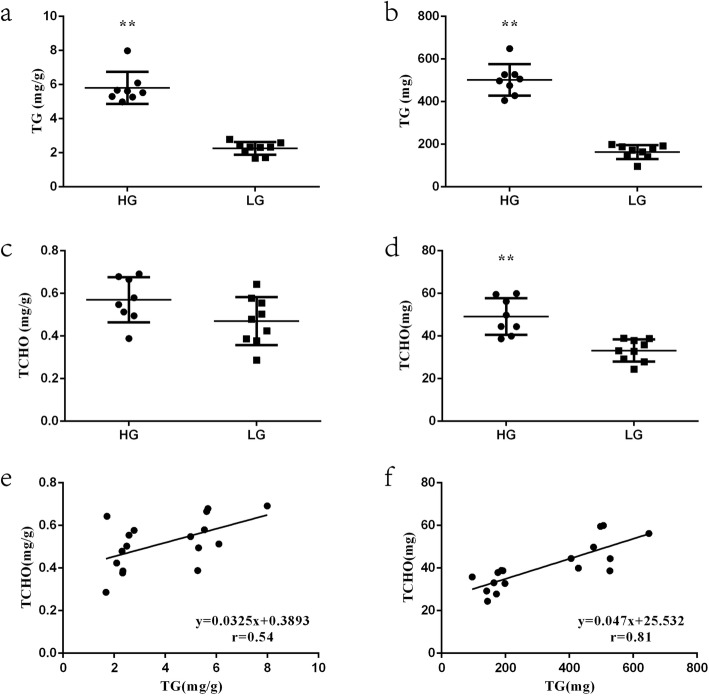

To study lipid metabolism in pectoralis muscle tissue from HTG and LTG chickens, the relative and absolute content of TG and TCHO in pectoralis muscle tissue samples were measured. The results revealed significant differences in the TG content between chickens from the HTG and LTG groups, as shown in Fig. 1a-b. The TG content in the HTG group was extremely significantly (p < 0.01) higher than that in LTG group (both relative and absolute content). There was no difference (p > 0.05) between the two groups in the relative TCHO content, while the absolute TCHO content in the HTG group was significantly higher (p < 0.01) than that in the LTG group (Fig. 1c-d). The contents of TG and TCHO in pectoralis muscle tissue samples, whether the relative or absolute content, were correlated (relative content correlation, r = 0.54, p < 0.05, absolute content correlation, r = 0.81, p < 0.01), as shown in Fig. 1e-f.

Fig. 1.

The content of triglyceride (TG) and total cholesterol (TCHO) in the higher TG content (HTG) group and lower TG content (LTG) and their correlation. a The relative content of TG in pectoralis muscle tissue (mg/g). b The absolute content of TG in pectoralis muscle tissue (mg). c The relative content of TCHO in pectoralis muscle tissue (mg/g). d The absolute content of TCHO in pectoralis muscle tissue (mg). e The correlation between the relative content of TG and TCHO in pectoralis muscle tissue (mg/g) was analyzed by Pearson correlation coefficient in the HTG and LTG groups (r = 0.54, p < 0.05). f The correlation between the absolute content of TG and TCHO in pectoralis muscle tissue (mg) was analyzed by Pearson correlation coefficient in the HTG and LTG groups (r = 0.81, p < 0.01). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05 or ** p < 0.01)

RNA sequencing data analysis

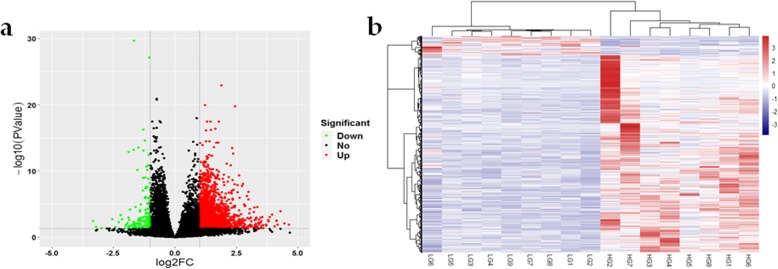

A total of 1200 known DEGs were identified, of which 1142 were upregulated and 58 were downregulated, in the HTG group compared with the LTG group (log2 FC ≥ 1 and FDR < 0.05), as shown in Fig. 2a and Additional file 1. One (odd-one-out) extreme individual with abnormal gene expression in the HTG group was excluded from the analysis. Hierarchical clustering analysis (based on DEGs) were performed to evaluate the consistency and variance of the samples from the HTG and LTG groups. The hierarchical clustering analysis results showed that only individuals within the same group clustered more closely (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

The results of the RNA sequencing analysis. a Volcano plot. The red dots (Up) represent significantly upregulated genes, the green dots (Down) represent significantly downregulated genes (|log2 fold change (FC)| ≥ 1 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05), and the black dots (No) represent insignificantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs). b Hierarchical clustering analysis. Hierarchical clustering analysis was performed based on DEGs, the heat-maps of all 17 samples revealed that the gene expression profiles in same group were closely related

Identification of DEGs related to lipid metabolism of HTG and LTG group

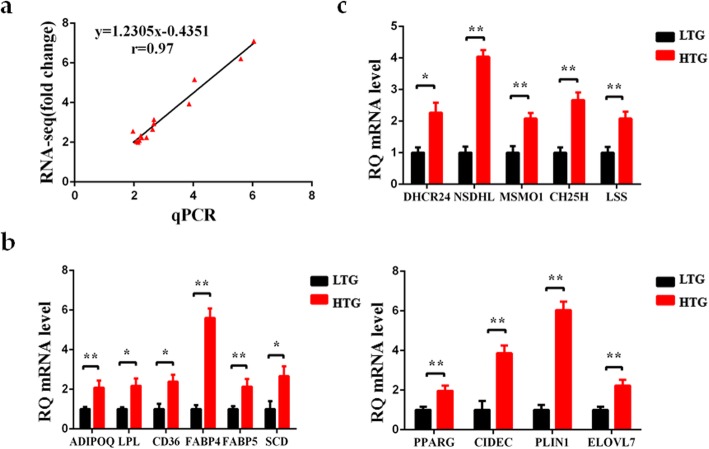

Based on 1200 known DEGs, 59 DEGs related to lipid metabolism were screened. Compared with the LTG group, 58 upregulated and 1 downregulated DEGs related to lipid metabolism were identified in the HTG group (Additional file 2), and were found to be involved in many biological processes: fatty acid binding and transport, fatty acid elongation, adipocyte differentiation, cholesterol metabolism and steroid biosynthesis. Also, almost all DEGs related to lipid deposition were significantly upregulated in the HTG group, indicating a greater capacity in lipid deposition than the LTG group. To confirm the reliability of the results, the transcript abundance of 15 key genes related to lipid metabolism were verified by qRT-PCR analysis. As shown in Fig. 3a, the fold-changes of gene expression determined by RNA-seq analysis and qRT-PCR analysis were highly correlated (r = 0.97, p < 0.05). The transcript abundance of the classical transcription factor PPARG was significantly upregulated in HTG group (p < 0.01). The expression of 7 genes (ADIPOQ, CD36, FABP4, FABP5, LPL, SCD and PLIN1) in the PPAR signaling pathway was significantly higher in the HTG group (p < 0.05 or p < 0.01). CIDEC, which plays an important role in controlling lipid droplet (LD) fusion and lipid storage, was significantly upregulated in the HTG group (p < 0.01). Additionally, ELOVL7, which participates in fatty acid elongation, also was significantly increased in the HTG group (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3b). In addition, the expression of DHCR24, LSS, MSMO1, NSDHL and CH25H, which are related to steroid metabolism, was significantly higher than that in the LTG group (Fig. 3c). These findings suggested that these genes are likely responsible for the higher lipid deposition in the HTG group compared with that in the LTG group.

Fig. 3.

Validation of the RNA sequencing analysis data by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis. a Correlation analysis of the relative expression levels of 15 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the RNA sequencing and qRT-PCR (r = 0.97, p < 0.05). b-c Expression level of representative genes involved in TG and steroid metabolism by qRT-PCR in the HTG and LTG chickens. All genes were significantly upregulated in the HTG group compared with LTG group. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05 or ** p < 0.01). RQ: relative quantification

Functional classification and pathway enrichment of DEGs in the HTG and LTG chickens

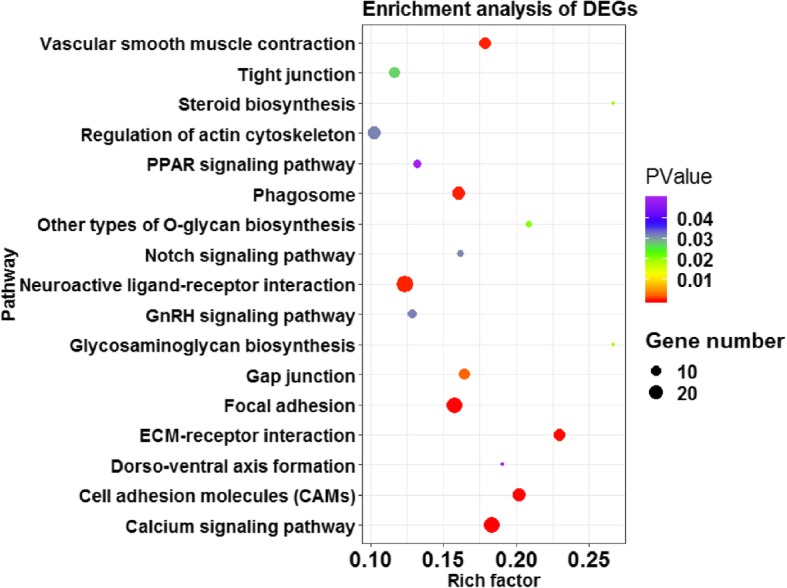

The function of the known DEGs was classified by GO enrichment analysis. A total of 55 Biological Process (BP) terms were significantly enriched (FDR < 0.05) (Additional file 3). These BP terms were mainly associated with metabolism process, muscle development, angiogenesis, signal transduction, cell activities (cell motility, migration, adhesion, communication, development and differentiation) and cytokine production. A KEGG pathway analysis was performed based on the 1200 known DEGs, and 17 pathways were significantly enriched (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4 and Additional file 4). Additionally, several pathways related to lipid metabolism were significantly enriched (p < 0.05), including steroid biosynthesis, PPAR signaling and cell junctions (focal adhesion, cell adhesion molecules, ECM-receptor interaction, gap junction, tight junction and regulation of actin cytoskeleton).

Fig. 4.

Advanced bubble chart shows significantly enriched pathways based on differentially expressed genes (DEGs) by Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis (p < 0.05). The x-axis represents rich factor (rich factor = number of DEGs enriched in the pathway/number of all genes in the background gene set). The y-axis represents the enriched pathway. Color represents enrichment significance, and the size of the bubble represents the number of DEGs enriched in the pathway

Discussion

In recent decades, poultry meat consumption is steadily increasing worldwide [15–17]. IMF content is an important factor determining meat flavor and texture parameters for chicken meat [2–5]. An appropriate IMF content is beneficial to improve meat quality, while excessive fat content may have adverse effects, such as white striping muscle [18]. Therefore, studying the genetic mechanism of IMF deposition in muscle tissue may contribute to improving the meat quality of chicken.

Currently, it is a common way to explore candidate genes related IMF metabolism using chickens with different IMF content. Given the composition and limitation of measurement accuracy, TG content was chosen as the major phenotype instead of conventional IMF to explore the hub genes involved in lipid deposition of pectoralis muscle tissue. In this study, broiler chickens with extremely high and low TG content were used to identify the important candidate genes and pathways affecting lipid metabolism in pectoralis muscle tissue by RNA sequencing analysis.

The phenotypic analysis results indicated that the lipid metabolism processes are different between the two investigated chicken groups, including TG metabolism as well as cholesterol biosynthesis in pectoralis muscle tissue. In the present study, TG and TCHO content were correlated in both relative and absolute content. As the neutral lipid core of LD, TG and sterol esters are indispensable for LD formation [19, 20], and the amount and composition of cholesterol esters and TG can affect lipoprotein metabolism and adiposity. Therefore, it is logical to infer that increased lipid deposition in pectoralis muscle tissue is affected by TG and TCHO content. To investigate the molecular regulation of TG and steroid lipid metabolism in chicken pectoralis muscle tissue, 59 DEGs related to lipid deposition were further analyzed.

The formation of LDs is a complex process, which includes the synthesis of neutral fat as well as the formation, growth and expansion of LD. In general, there is a balance between dietary absorbed fat, de novo synthesis of fatty acids (lipogenesis) and fat catabolism involving key enzymes and transcription factors [21]. SCD encodes a key rate-limiting enzyme in lipogenesis, which transform palmitic acid (C16:0) and stearic acid (C18:0) to palmitoleic (C16:1) and oleic (C18:1n-9) [22]. C16:0 and C18:1, the most abundant cellular long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs), are mainly used as components of TGs [23]. In addition, very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) also have unique functions in lipid metabolism. The elongation of very long-chain fatty acid (ELOVL) protein family is required for the rate-limiting step in the elongation cycle of the synthesis of LCFAs and VLCFAs [24, 25]. ELOVL7 is a newly discovered ELOVL protein family member, which triggers lipid accumulation in differentiated adipocytes [26]. Previous studies revealed that female chickens exhibited increased SCD expression in pectoralis muscle tissue than male chickens [27]. However, the relationship between ELOVL7 gene and lipid deposition is still poorly understood in chicken muscle tissue. The expression of SCD and ELOVL7 in the HTG group was higher than that in the LTG group, indicating that increased synthesis of fatty acids might promote the synthesis and deposition of TGs. Except for de novo synthesis and elongation of FA, the utilization of free FA is also a key step in lipid metabolism. FABP5 was found to be involved in the transport of large amounts of intracellular FAs into the nucleus to activate PPARG [28, 29]. Previous study indicated that upregulated FABP5 might contribute to excessive fat deposition in domestic ducks [30]. Compared with the LTG group, the mRNA level of FABP5 and PPARG was elevated in the HTG group. In addition, the upregulated expression of certain adipocyte differentiation markers, including ADIPOQ, FABP4, LPL and CD36 [31–36] may be associated with increased lipid accumulation in the HTG group. CIDEC, a kind of LD-associated enzymes involved in LD fusion and growth, is mainly expressed to increase intracellular TG concentration [37]. CIDEC binds to the surface of LD and co-locates with the lipid-binding proteins, perilipins (PLINs) [38, 39]. PLIN1 was found to interact with CIDEC to promote LD formation by activating the PPARG signaling pathway [40–42]. According to published reports, higher PLIN1 and CIDEC expression promoted higher fat accumulation in chickens [43]. In this study, CIDEC and PLIN1 were all upregulated in the HTG group, which is consistent with their increased TG content. The upregulation of all these genes indicated a higher lipid biosynthesis in the HTG group. Previous studies have identified numerous candidate genes (PPARs, FABPs, LPL, SCD, KLFs and ACSLs) related to IMF deposition in chickens [7–10]. Most of these genes are associated with TG deposition in this study, indicating they might play an important role in IMF deposition by regulating TG metabolism.

Most of the intracellular cholesterol is positively correlated with LDs and cholesterol homeostasis may play a key role in the regulation of adipocytes size and function [44]. In this study, consistent with the phenotypic trait, the expression of key genes (DHCR24, LSS, MSMO1, NSDHL and CH25H), which encode proteins that are involved in steroid biosynthesis process [45–49], was upregulated in the HTG group compared with the LTG group. The quantity of fat deposition increases faster and earlier in fast-growing chickens than that in slow-growing chickens. The expression of genes involved in cholesterol biosynthesis in liver and hypothalamus tissues, such as LSS, NSDHL and DHCR24, was higher in the fast-growing chickens than that in the slow-growing chickens [50]. Consistent with our results, active cholesterol metabolism may be associated with increased fat deposition in chickens. Currently, reported studies mainly focused on the dietary effect on cholesterol synthesis [51] and the function of endogenous steroid metabolism in hepatic lipid deposition [52]. This study highlighted the contribution of steroid metabolism to muscle lipid metabolism and provided a new clue for exploring the mechanism of IMF deposition in chickens.

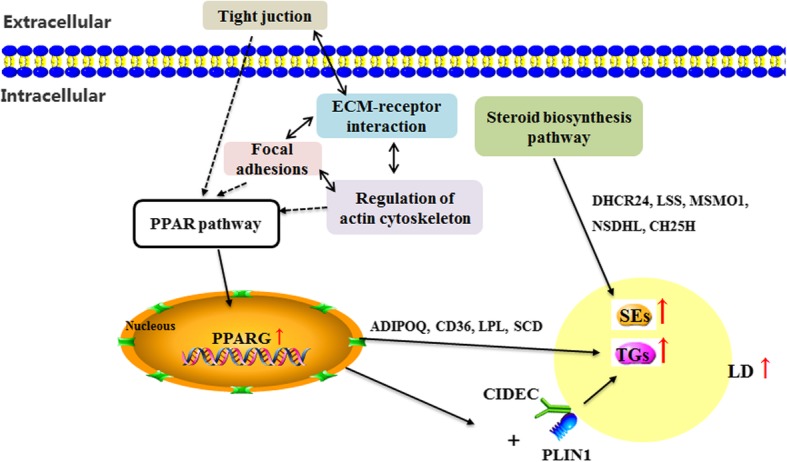

Based on the identified DEGs, KEGG pathway analysis was conducted to investigate the regulatory network underlying differential lipid deposition in chicken pectoralis muscle tissue. Among the DEGs associated with lipid metabolism, six DEGs (ADIPOQ, CD36, LPL, SCD, PPARG and PLIN1) were significantly enriched in the PPAR signaling pathway (p < 0.05). Several DEGs (DHCR24, LSS, MSMO1, NSDHL and CH25H) that participate in cholesterol synthesis were significantly enriched in the steroid biosynthesis pathway (p < 0.05). Additionally, DEGs were also significantly enriched (p < 0.05) in calcium signaling pathway and junction-related pathways (focal adhesions, cell adhesion, gap junction, tight junction, regulation of actin cytoskeleton and ECM-receptor interaction). Many studies have shown that the cell junction-related pathways may contribute to lipid deposition [9, 53, 54]. These results indicated that the above pathways might be the key pathways for lipid deposition in chicken pectoralis muscle tissue and a possible molecular regulatory network was constructed (Fig. 5). After activating the transcription factor PPARG in the PPAR signaling pathway, lipogenesis genes (ADIPOQ, CD36, LPL and SCD) may be upregulated to promote TG synthesis. In addition, PPARG may promote the interaction of PLIN1 with CIDEC to accelerate LD formation. At the same time, the upregulated expression of cholesterol synthesis genes (DHCR24, LSS, MSMO1, NSDHL and CH25H) in the steroid biosynthesis pathway may increase steroid ester synthesis. There is no doubt for the importance of PPAR signaling pathway in regulating lipid metabolism among muscle, liver and adipose tissues. However, different regulatory network centered on PPAR signaling pathway may contribute to specific lipid deposition in tissues. In this study, the active network, including PPAR signaling pathway and steroid biosynthesis pathway, might lead to an increase in lipid deposition in chicken pectoralis muscle tissue. In the future, much effort is still needed to further insight into the genetic regulation of IMF deposition in chickens.

Fig. 5.

The potential regulatory network of lipid metabolism according to the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) enriched in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways. TGs: Triglycerides; SEs: Sterol esters. Dotted arrows indicate possible regulatory relationships; solid arrows indicate reported regulatory relationships; double-ended arrows indicate bidirectional regulatory relationships

Conclusions

In summary, chickens from the higher TG content group (HTG) and lower triglyceride (TG) content group (HTG) were used to identify candidate genes and pathways related to differential lipid metabolism in pectoralis muscle tissue. The results showed that increased TG metabolism was accompanied by an increase of the steroid synthesis by regulating the expression of related genes (ADIPOQ, CD36, FABP4, FABP5, LPL, SCD, PLIN1, PPARG, CIDEC, DHCR24, LSS, MSMO1, NSDHL and CH25H). The results suggested that the PPAR pathway and steroid biosynthesis pathway might play a dominant role in this process. These findings provide new clues to understand revealing the molecular mechanisms underlying differential lipid deposition in chicken pectoralis muscle tissue.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for Experimental Animals established by the Ministry of Science and Technology (Beijing, China). All experimental protocols were approved by the Science Research Department (in charge of animal welfare issues) of the Institute of Animal Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Beijing, China) (No. IAS2019–21).

Animals and sampling

Jingxing-Huang female broilers were obtained from the Institute of Animal Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. All birds (n = 520) were raised in three-story step cages (one bird per cage) under the same recommended environmental and nutritional conditions. The basal diet was formulated based on the National Research Council (1994) requirements and the Feeding Standards of Chickens established by the Ministry of Agriculture, Beijing, China (2004).

All chickens were individually euthanized by carbon dioxide anesthesia and exsanguination by severing the carotid artery at 98 days of age after 12-h fasting (no additional feed was supplied and the feed trough was not emptied). After slaughtering, the pectoralis major muscle was dissected in the same area in all chickens. The pectoralis major muscle samples were weighed, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C for subsequent RNA isolation. The remaining pectoralis major muscle tissues were removed, weighed, and stored at − 20 °C for the measurement of TG and total cholesterol (TCHO) contents.

Measurement of biochemical indices

The TG and TCHO contents in pectoralis muscle tissue samples were measured using TG and TCHO assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). Pectoralis muscle tissue samples (about 2 g) from each chicken were homogenized with absolute ethanol at room temperature and centrifuged (1000×g, 20 min). After centrifugation, the supernatant was used for TG and TCHO measurement. A 2.5-μL aliquot of the supernatant and 250 μL reagent were co-incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. The absorbance of each sample was measured using a microplate reader at 510 nm. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA extraction and sequencing

Chickens with extremely higher (HTG, n = 9) and lower (LTG, n = 9) TG content were used for RNA extraction and sequencing. Pectoralis muscle tissue samples from the HTG and LTG group were selected to isolate total RNA using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The detection of RNA quality was referred to in Resnyk et al. [55]. RNA purity was checked using the kaiaoK5500®Spectrophotometer (Kaiao, Beijing, China) and RNA integrity and concentration was assessed using the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit of the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). After determining the concentration, purity and integrity, the RNA samples with an A260/A280 ratio between 1.8 and 2.0 and an RNA integrity number > 7.5 were used for RNA sequencing and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis.

We used the methodology of cDNA library construction previously described by Chen et al. [56]. The mRNA was enriched by binding of the mRNA poly-A tail to magnetic beads with Oligo (dT) and fragmented into small pieces. Single strand cDNA and double strand cDNA were synthesized using mRNA as a template. The double-stranded cDNA was purified using the QIAQuick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA). After purification, end repair, and ligation to sequencing adapters, agarose gel electrophoresis was used for fragment size selection. Finally, PCR enrichment was performed to obtain the final cDNA library. RNA-sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 S2 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) by Annoroad Genomics (Beijing, China) and 150-bp paired-end reads were generated (Additional file 5).

Data analysis of RNA sequencing

Sequence adapters and low-quality reads (read quality < 30) were removed by Trimmomatic (v0.32), and quality control checks on raw sequence data were performed with FastQC. Sequencing reads were mapped to the chicken reference genome [Ensembl GRCg6a (GCA_000002315.5)] using the HISAT2 program [57]. To quantify the expression of each transcript, alignment results were analyzed by the Cufflinks (v2.0.2) software [58]. Analysis of differential expression of transcripts was performed with DESeq2 package (v 1.24.0). Genes with false discovery rate (FDR) value < 0.05 and |log2 fold change (FC)| ≥ 1 were considered to be DEGs.

Hierarchical clustering analysis was performed to determine the variability and repeatability of the samples and a volcano plot was used to visualize the overall distribution of DEGs. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed to identify the gene function classes and categories of DEGs using the DAVID functional annotation clustering. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis was performed by KOBAS 3.0 [59] (http://kobas.cbi.pku.edu.cn). The significance level for GO terms and the KEGG pathway was set with FDR < 0.05 and p < 0.05, respectively.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

All PCR primers were designed at or just outside exon/exon junctions to avoid the amplification of residual genomic DNA using the Primer-BLAST on the NCBI website, and specificity was determined using BLASTN (Additional file 6).

qRT-PCR analysis was performed after a reverse transcription reaction. cDNA was prepared with 2.0 μg of total RNA of each sample, by reverse transcription using the FastQuant RT Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) in accordance with the kit manufacturer’s instructions. Each PCR mixture was prepared in a final volume of 20 μL consisting of 10 μL of 2 × iQTM SYBR Green Supermix, 0.5 μL (10 mmol/L) of each primer, and 1 μL of cDNA. Samples were amplified on the QuantStudio 7 Flex system (Applied Biosystems, Shanghai, China) using 40 cycles (95 °C for 3 min, 95 °C for 3 s and 60 °C for 34 s). The amplification procedure was performed with 3 replicates for each sample. The collected data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method [60], and all the results were normalized to the 18S rRNA gene.

Statistical analyses

Significance of differences between groups was tested by the Student t-test using the SPSS Version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Confidence limits were set at 95% and p < 0.05 (*) or p < 0.01 (**) was considered significant. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error (SEM).

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. The screened DEGs between HTG and LTG group.

Additional file 2. The 59 DEGs related to lipid metabolism.

Additional file 3. The enriched GO-terms based on 1200 DEGs.

Additional file 4. The enriched pathways based on 1200 DEGs.

Additional file 5. The details about RNA-seq data statistics in this study.

Additional file 6. The specific primers for qPCR in this study.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ADIPOQ

Adiponectin

- BP

Biological Process

- CH25H

Cholesterol 25-hydroxylase

- CIDEC

Cell death-inducing DNA fragmentation factor subunit alpha (DFFA)-like effector c

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- DHCR24

24-Dehydrocholesterol reductase

- ELOVL7

Fatty acid elongase 7

- ELOVLs

Fatty acid elongases

- FABP4

Fatty acid binding protein 4

- FABP5

Fatty acid binding protein 5

- FABPs

Fatty acid binding proteins

- FC

Fold change

- FDR

False discovery rate

- FFA

Free fatty acid

- GO

Gene Ontology

- HTG

Higher TG content

- IMF

Intramuscular fat

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LCFAs

Long-chain fatty acids

- LD

Lipid droplet

- LPL

Lipoprotein lipase

- LSS

Lanosterol synthase

- LTG

Lower TG content

- MSMO1

Methylsterol monooxygenase 1

- NSDHL

NAD(P) dependent steroid dehydrogenase-like

- PLINs

Perilipins

- PPAR

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- SCD

Stearoyl-CoA desaturase

- TCHO

Total cholesterol

- TG

Triglyceride

- VLCFAs

Very long-chain fatty acids

- WAT

White adipose tissue

Authors’ contributions

LL performed of the study, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. LXJ performed of the study and analyzed the data. HXC contributed to the design of the study, acquiring the funding and modifying the manuscript. GPZ contributed to providing resources. RRL contributed to the acquiring the funding. JW designed the study and was in charge of the overall project. All authors submitted comments on drafts, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFD0500401), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31872340), Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences Institute of Animal Sciences Basic Research (2019-YWF-YB-07), the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (ASTIP-IAS04), and the Earmarked Fund for Modern Agro-Industry Technology Research System (CARS-41). The funding agencies had not involved in the experimental design, analysis and interpretation of the data or writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The RNA sequencing clean data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive [61] in BIG Data Center [62] under accession number CRA001908 which can be publicly accessed at http://bigd.big.ac.cn/gsa.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for Experimental Animals established by the Ministry of Science and Technology (Beijing, China). All experimental protocols were approved by the Science Research Department (in charge of animal welfare) of the Institute of Animal Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS), Beijing, China. Consent to participate: Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lu Liu and Xiaojing Liu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Lu Liu, Email: liulu_0907@126.com.

Xiaojing Liu, Email: 18810610203@163.com.

Huanxian Cui, Email: cuihuanxian78@126.com.

Ranran Liu, Email: liuranran@caas.cn.

Guiping Zhao, Email: zhaoguiping@caas.cn.

Jie Wen, Email: wenjie@caas.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12864-019-6221-0.

References

- 1.Pena R, Ros-Freixedes R, Tor M, Estany J. Genetic marker discovery in complex traits: a field example on fat content and composition in pigs. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(12):2100. doi: 10.3390/ijms17122100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuentes V, Ventanas J, Morcuende D, Ventanas S. Effect of intramuscular fat content and serving temperature on temporal sensory perception of sliced and vacuum packaged dry-cured ham. Meat Sci. 2013;93(3):621–629. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerbens F, Verburg FJ, Van Moerkerk HT, Engel B, Buist W, Veerkamp JH, et al. Associations of heart and adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein gene expression with intramuscular fat content in pigs. J Anim Sci. 2001;79(2):347–354. doi: 10.2527/2001.792347x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nogalski Z, Pogorzelska-Przybylek P, Bialobrzewski I, Modzelewska-Kapitula M, Sobczuk-Szul M, Purwin C. Estimation of the intramuscular fat content of m. longissimus thoracis in crossbred beef cattle based on live animal measurements. Meat Sci. 2017;125:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2016.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okeudo NJ, Moss BW. Interrelationships amongst carcass and meat quality characteristics of sheep. Meat Sci. 2005;69(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun Y, Zhao G, Liu R, Zheng M, Hu Y, Wu D, et al. The identification of 14 new genes for meat quality traits in chicken using a genome-wide association study. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:458. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Liu W, Hang C, Du Y, Chen Y, Xing J, et al. Association of A-FABP gene polymorphism and mRNA expression with intramuscular fat content (IMF) in Baicheng-You chicken. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2019;103:1447–1452. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li G, Zhao Y, Li Y, Chen Y, Jin W, Sun G, et al. Weighted gene coexpression network analysis identifies specific transcriptional modules and hub genes related to intramuscular fat traits in chicken breast muscle. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(8):13625–13639. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cui HX, Liu RR, Zhao GP, Zheng MQ, Chen JL, Wen J. Identification of differentially expressed genes and pathways for intramuscular fat deposition in pectoralis major tissues of fast-and slow-growing chickens. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:213. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu R, Wang H, Liu J, Wang J, Zheng M, Tan X, et al. Uncovering the embryonic development-related proteome and metabolome signatures in breast muscle and intramuscular fat of fast-and slow-growing chickens. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):816. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4150-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nye C, Kim J, Kalhan SC, Hanson RW. Reassessing triglyceride synthesis in adipose tissue. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008;19(10):356–361. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu Y, Sun Q, Hu Y, Hou Z, Zong Y, Omer NA, et al. Corticosterone-induced Lipogenesis activation and Lipophagy inhibition in chicken liver are alleviated by maternal Betaine supplementation. J Nutr. 2018;148(3):316–325. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxx073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu L, Cui HX, Zheng MQ, Zhao GP, Wen J. Comparative analysis of differentially expressed genes related to triglyceride metabolism between intramuscular fat and abdominal fat in broilers. Br Poult Sci. 2018;59(5):514–520. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2018.1483573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y, Shen J, Yang X, Sun Q, Yang X. Folic acid reduced triglycerides deposition in primary chicken hepatocytes. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66(50):13162–13172. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b05193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He Y, Yang X, Xia J, Zhao L, Yang Y. Consumption of meat and dairy products in China: a review. Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;75(3):385–391. doi: 10.1017/S0029665116000641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rouger A, Tresse O, Zagorec M. Bacterial contaminants of poultry meat: sources, species, and dynamics. Microorganisms. 2017;5(3):50. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms5030050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sans P, Combris P. World meat consumption patterns: an overview of the last fifty years (1961-2011) Meat Sci. 2015;109:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pampouille E, Berri C, Boitard S, Hennequet-Antier C, Beauclercq SA, Godet E, et al. Mapping QTL for white striping in relation to breast muscle yield and meat quality traits in broiler chickens. BMC Genomics. 2018;19(1):202. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4598-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khor VK, Shen WJ, Kraemer FB. Lipid droplet metabolism. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16(6):632–637. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283651106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walther TC, Chung J, Farese RV., Jr Lipid Droplet Biogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2017;33:491–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alberdi G, Rodriguez VM, Miranda J, Macarulla MT, Arias N, Andres-Lacueva C, et al. Changes in white adipose tissue metabolism induced by resveratrol in rats. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2011;8(1):29. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-8-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meng Q, Sun S, Sun Y, Li J, Wu D, Shan A, et al. Effects of dietary lecithin and l-carnitine on fatty acid composition and lipid-metabolic genes expression in subcutaneous fat and longissimus thoracis of growing-finishing pigs. Meat Sci. 2018;136:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodson L, Skeaff CM, Fielding BA. Fatty acid composition of adipose tissue and blood in humans and its use as a biomarker of dietary intake. Prog Lipid Res. 2008;47(5):348–380. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denic V, Weissman JS. A molecular caliper mechanism for determining very long-chain fatty acid length. Cell. 2007;130(4):663–677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leonard AE, Pereira SL, Sprecher H, Huang YS. Elongation of long-chain fatty acids. Prog Lipid Res. 2004;43(1):36–54. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7827(03)00040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen S, Hu Z, He H, Liu X. Fatty acid elongase7 is regulated via SP1 and is involved in lipid accumulation in bovine mammary epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(6):4715–4725. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin J, Lim S, Latshaw JD, Lee K. Cloning and expression of delta-like protein 1 messenger ribonucleic acid during development of adipose and muscle tissues in chickens. Poult Sci. 2008;87(12):2636–2646. doi: 10.3382/ps.2008-00189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shrestha N, Cuffe JSM, Holland OJ, Perkins AV, McAinch AJ, Hryciw DH. Linoleic acid increases prostaglandin E2 release and reduces mitochondrial respiration and cell viability in human Trophoblast-like cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2019;52(1):94–108. doi: 10.33594/000000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang D, Li Y, Xing L, Tan Y, Sun J, Zeng B, et al. Utilization of adipocyte-derived lipids and enhanced intracellular trafficking of fatty acids contribute to breast cancer progression. Cell Commun Signal. 2018;16(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12964-018-0221-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen L, Luo J, Li JX, Li JJ, Wang DQ, Tian Y, et al. Transcriptome analysis of adiposity in domestic ducks by transcriptomic comparison with their wild counterparts. Anim Genet. 2015;46(3):299–307. doi: 10.1111/age.12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bensadoun A. Lipoprotein lipase. Annu Rev Nutr. 1991;11:217–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.11.070191.001245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J, Liu Y, Lu S, Yin L, Zong C, Cui S, et al. The role and possible mechanism of lncRNA U90926 in modulating 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation. Int J Obes. 2017;41(2):299–308. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao Y, Li F, Zhang Y, Dai L, Jiang H, Liu H, et al. Silencing of ADIPOQ efficiently suppresses preadipocyte differentiation in porcine. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2013;31(2–3):452–461. doi: 10.1159/000343381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldberg IJ. Lipoprotein lipase and lipolysis: central roles in lipoprotein metabolism and atherogenesis. J Lipid Res. 1996;37(4):693–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagy L, Tontonoz P, Alvarez JG, Chen H, Evans RM. Oxidized LDL regulates macrophage gene expression through ligand activation of PPARgamma. Cell. 1998;93(2):229–240. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zizola CF, Schwartz GJ, Vogel S. Cellular retinol-binding protein type III is a PPARgamma target gene and plays a role in lipid metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295(6):E1358–E1368. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90464.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu L, Zhou L, Li P. CIDE proteins and lipid metabolism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(5):1094–1098. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.241489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez-Botas J, Anderson JB, Tessier D, Lapillonne A, Chang BH, Quast MJ, et al. Absence of perilipin results in leanness and reverses obesity in Lepr(db/db) mice. Nat Genet. 2000;26(4):474–479. doi: 10.1038/82630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu W, Wu L, Yu M, Chen FJ, Arshad M, Xia X, et al. Differential roles of cell death-inducing DNA fragmentation factor-alpha-like effector (CIDE) proteins in promoting lipid droplet fusion and growth in subpopulations of hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(9):4282–4293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.701094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Bojiang, Weng Qiannan, Dong Chao, Zhang Zengkai, Li Rongyang, Liu Jingge, Jiang Aiwen, Li Qifa, Jia Chao, Wu Wangjun, Liu Honglin. A Key Gene, PLIN1, Can Affect Porcine Intramuscular Fat Content Based on Transcriptome Analysis. Genes. 2018;9(4):194. doi: 10.3390/genes9040194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsusue K, Kusakabe T, Noguchi T, Takiguchi S, Suzuki T, Yamano S, et al. Hepatic steatosis in leptin-deficient mice is promoted by the PPARgamma target gene Fsp27. Cell Metab. 2008;7(4):302–311. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou L, Xu L, Ye J, Li D, Wang W, Li X, et al. Cidea promotes hepatic steatosis by sensing dietary fatty acids. Hepatology. 2012;56(1):95–107. doi: 10.1002/hep.25611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peng G, Huang E, Ruan J, Huang L, Liang H, Wei Q, et al. Effects of a high energy and low protein diet on hepatic and plasma characteristics and Cidea and Cidec mRNA expression in liver and adipose tissue of laying hens with fatty liver hemorrhagic syndrome. Anim Sci J. 2019;90(2):247–254. doi: 10.1111/asj.13140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Le Lay S, Krief S, Farnier C, Lefrere I, Le Liepvre X, Bazin R, et al. Cholesterol, a cell size-dependent signal that regulates glucose metabolism and gene expression in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(20):16904–16910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nes WD. Biosynthesis of cholesterol and other sterols. Chem Rev. 2011;111(10):6423–6451. doi: 10.1021/cr200021m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xin Y, Li C, Guo Y, Xiao R, Zhang H, Zhou G. RNA-Seq analysis reveals a negative role of MSMO1 with a synergized NSDHL expression during adipogenesis of 3T3-L1. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2019;83(4):641–652. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2018.1559719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luu W, Zerenturk EJ, Kristiana I, Bucknall MP, Sharpe LJ, Brown AJ. Signaling regulates activity of DHCR24, the final enzyme in cholesterol synthesis. J Lipid Res. 2014;55(3):410–420. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M043257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Getz GI, Parag-Sharma K, Reside J, Padilla RJ, Amelio AL. Identification of NSDHL mutations associated with CHILD syndrome in oral verruciform xanthoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2019;128:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blanc M, Hsieh WY, Robertson KA, Kropp KA, Forster T, Shui G, et al. The transcription factor STAT-1 couples macrophage synthesis of 25-hydroxycholesterol to the interferon antiviral response. Immunity. 2013;38(1):106–118. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jin S, Yang L, Zang H, Xu Y, Chen X, Chen X et al. Influence of free-range days on growth performance, carcass traits, meat quality, lymphoid organ indices, and blood biochemistry of Wannan Yellow chickens. Poult Sci. 2019. 10.3382/ps/pez504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Li H, Wang T, Xu C, Wang D, Ren J, Li Y, et al. Transcriptome profile of liver at different physiological stages reveals potential mode for lipid metabolism in laying hens. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:763. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1943-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Claire D'Andre H, Paul W, Shen X, Jia X, Zhang R, Sun L, et al. Identification and characterization of genes that control fat deposition in chickens. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2013;4(1):43. doi: 10.1186/2049-1891-4-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee HJ, Jang M, Kim H, Kwak W, Park W, Hwang JY, et al. Comparative Transcriptome analysis of adipose tissues reveals that ECM-receptor interaction is involved in the depot-specific Adipogenesis in cattle. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weibel GL, Joshi MR, Jerome WG, Bates SR, Yu KJ, Phillips MC, et al. Cytoskeleton disruption in J774 macrophages: consequences for lipid droplet formation and cholesterol flux. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821(3):464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Resnyk CW, Carre W, Wang X, Porter TE, Simon J, Le Bihan-Duval E, et al. Transcriptional analysis of abdominal fat in chickens divergently selected on bodyweight at two ages reveals novel mechanisms controlling adiposity: validating visceral adipose tissue as a dynamic endocrine and metabolic organ. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):626. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4035-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen Fuxiang, Wu Pengfei, Shen Manman, He Mingliang, Chen Lan, Qiu Cong, Shi Huiqiang, Zhang Tao, Wang Jiahong, Xie Kaizhou, Dai Guojun, Wang Jinyu, Zhang Genxi. Transcriptome Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes Related to the Growth and Development of the Jinghai Yellow Chicken. Genes. 2019;10(7):539. doi: 10.3390/genes10070539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Siren J, Valimaki N, Makinen V. Indexing graphs for path queries with applications in genome research. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform. 2014;11(2):375–388. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2013.2297101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ghosh S, Chan CK. Analysis of RNA-Seq data using TopHat and cufflinks. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1374:339–361. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3167-5_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu J, Mao X, Cai T, Luo J, Wei L. KOBAS server: a web-based platform for automated annotation and pathway identification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Web Server issue):W720–W724. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Y, Song F, Zhu J, Zhang S, Yang Y, Chen T, et al. GSA: genome sequence archive<sup/>. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2017;15(1):14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Members BDC. Database resources of the BIG data center in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D8–D14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. The screened DEGs between HTG and LTG group.

Additional file 2. The 59 DEGs related to lipid metabolism.

Additional file 3. The enriched GO-terms based on 1200 DEGs.

Additional file 4. The enriched pathways based on 1200 DEGs.

Additional file 5. The details about RNA-seq data statistics in this study.

Additional file 6. The specific primers for qPCR in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The RNA sequencing clean data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive [61] in BIG Data Center [62] under accession number CRA001908 which can be publicly accessed at http://bigd.big.ac.cn/gsa.