Abstract

Background

Jianpi-yangwei (JPYW), a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), helps to nourish the stomach and spleen and is primarily used to treat functional declines related to aging. This study aimed to explore the antiaging effects and mechanism of JPYW by employing a Caenorhabditis elegans model.

Methods

Wild-type C. elegans N2 worms were cultured in growth medium with or without JPYW, and lifespan analysis, oxidative and heat stress resistance assays, and other aging-related assays were performed. The effects of JPYW on the levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and the expression of specific genes were examined to explore the underlying mechanism of JPYW.

Results

Compared to control worms, JPYW-treated wild-type worms showed increased survival times under both normal and stress conditions (P < 0.05). JPYW-treated worms also exhibited enhanced reproduction, movement and growth and decreased intestinal lipofuscin accumulation compared to controls (P < 0.05). Furthermore, increased activity of SOD, downregulated expression levels of the proaging gene clk-2 and upregulated expression levels of the antiaging genes daf-16, skn-1, and sir-2.1 were observed in the JPYW group compared to the control group.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that JPYW extends the lifespan of C. elegans and exerts antiaging effects by increasing the activity of an antioxidant enzyme (SOD) and by regulating the expression of aging-related genes. This study not only indicates that this Chinese compound exerts antiaging effects by activating and repressing target genes but also provides a proven methodology for studying the biological mechanisms of TCMs.

Keywords: Jianpi-yangwei formula, Traditional Chinese medicine, Caenorhabditis elegans, Aging

Background

Aging is believed to be an inevitable physiological process that occurs in all living organisms [1] and has been a concern since ancient times. Some researchers have suggested that the aging process is affected by environmental [2, 3], nutritional [4], and genetic factors [5] and have attempted to explore the mechanisms of aging. In addition, in modern times, an increasing number of aging-related diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, chronic degenerative diseases and other aging-related dysfunctions, have threatened human health [6, 7]. Even though increasing evidence has demonstrated that pharmacological intervention may delay the senescence process [8, 9], a definitely effective antiaging treatment has not yet been found since the mechanisms of aging are complicated.

In contrast to mainstream modern medicine, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) aims to interfere with the aging process as early as possible, thus preventing and delaying the occurrence and development of aging-related diseases, and has begun to draw increasing research interest [10–12]. TCM has been used as a complementary medicine for 5000 years and has garnered much attention as a result of its high medical efficacy and its preventative functions [10, 11, 13]. In recent years, many studies have suggested that lots of TCMs exhibit an array of antiaging effects [12, 14, 15]. According to TCM theory, Jianpi-yangwei (JPYW) therapy is one of the main treatment modalities for aging and has been clinically demonstrated to be effective [16–20]; however, further research on the nature of JPYW is necessary due to the complexity of its composition. JPYW is a TCM formula that is mainly composed of 8 ingredients: Panax ginseng C. A. Mey, Radix Paeoniae Alba, Codonopsis Radix, Poria cocos, Rhizoma Atractylodis Macrocephalae, Crataegus pinnatifida, Pericarpium Citri Reticulatae, and Cinnamomum cassia Presl. In TCM theory, JPYW is based on the Sijunzi decoction, which is a classic Chinese medicine that has been demonstrated to be beneficial for the spleen and stomach as a result of its antiaging effects [19, 21]. In a previous study, a JPYW capsule was proven to have therapeutic effects on gastric precancerous lesions and cancer-related fatigue [22]. In the present study, we found that JPYW exhibited a spleen-fortifying and stomach-nourishing effect that helped to replenish energy and recover functions that were declining as a result of aging. Moreover, we drew our conclusions from ten years of clinical experience showing that JPYW has strong antiaging effects. Notably, previous studies suggested that Caenorhabditis elegans was a comparatively ideal model for aging research [23, 24].

This study aimed to explore the antiaging effects and the mechanism of JPYW in wild-type C. elegans N2 worms (Bristol). Lifespan assays, stress resistance assays and other aging-related factors and properties were assessed to evaluate antiaging effects. The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and the expression levels of aging-related genes were assessed to illustrate the potential mechanisms.

Methods

Preparation of JPYW

JPYW mainly consists of 8 crude herbs: P. ginseng C. A. Mey, Radix Paeoniae Alba, Codonopsis Radix, P. cocos, Rhizoma Atractylodis Macrocephalae, C. pinnatifida, Pericarpium Citri Reticulatae, and C. cassia Presl. For this study, we used a mixture of water extracts of the crude herbs. The water extracts were provided by Kangmei Pharmaceutical Co. (Guangzhou, China), were produced according to the rigid specifications of the Pharmacopeia of the People’s Republic of China and were approved by the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA). In accordance with TCM research conventions, all concentrations reported in this study refer to the concentrations of the crude herbs. The JPYW used in the study was dissolved in 1% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO).

C. elegans: strains and maintenance

The wild-type C. elegans N2 worms (Bristol) and E. coli OP50 were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC) (Minneapolis, MN, USA). The C. elegans strains were cultured at 20 °C on solid nematode growth medium (NGM) plates seeded with E. coli OP50. The wild-type C. elegans N2 worms (Bristol) were aged and were considered adults at 7 days.

Lifespan analysis

A bleaching technique was used to synchronize the worm population in this study. The age-synchronized N2 nematodes were transferred to NGM plates containing 150 μg/ml JPYW or a vehicle control (1% DMSO). E. coli OP50 was added to the medium. Two NGM plates containing 25 worms each were used, and the worms were transferred to new NGM plates every day for the first 7 days so that the new eggs did not have a disruptive effect. Then, the survival rate was assessed every other day until the worms died. The survival fraction was calculated by recording the number of surviving worms. We considered the nematodes to be dead when there was no respond after touching them with a platinum loop (failed to exhibit touch-provoked movement). At least three independent trials of the lifespan assay were performed.

Assessment of stress resistance

Age-synchronized N2 worms were bred on NGM plates with or without 150 μg/ml JPYW. For a heat tolerance assay, day 4 adult worms (on the 4th day after the worms reached adulthood, n = 50) were transferred to fresh plates containing 150 μg/ml JPYW or a vehicle control and then incubated at 37 °C. Survival was recorded every hour until all worms had died. The tolerance to oxidative stress was measured as reported previously [25]. Briefly, day 4 adult worms (n = 50) were placed on plates with various concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (from 0 mM to 1 mM, intervals of 0.2 mM) as well as 150 μg/ml JPYW or a vehicle control, and then the survival was recorded after 15 h. Each test was repeated at least twice.

Measurement of SOD activity

To measure SOD activity, wild-type worms (n = 50) were collected from plates with M9 buffer on the 5th day of adulthood (day 5 after the worms reached adulthood) and washed 3 times. Then, the collected worms were resuspended in homogenization buffer (10 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane hydrochloride(Tris-HCl), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mM ethylenedinitrilotetraacetic acid (EDTA), pH 7.5) and homogenized through ultrasonication on ice. A total of 0.5 mg protein from every group was used to measure SOD activity. The SOD activity was spectrophotometrically analyzed on the basis of the decolorization of formazan. A Total Superoxide Dismutase (T-SOD) Assay Kit (hydroxylamine method) and a Total Protein Assay Kit (standard: bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method) were purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China) and were used to determine the SOD activity and protein concentration, respectively. The procedures were performed in strict accordance with the manufacturers’ protocols.

Measurement of aging-related factors

For a pharyngeal pumping assay, age-synchronized N2 worms (n = 10) were treated with 150 μg/ml JPYW or vehicle until the 4th day after the worms reached adulthood, and then their pharynx contractions were counted under an inverted microscope for 10 s in the fresh plates.

For reproduction assay, worms (n = 5) were cultured from eggs. Worms were individually moved to a fresh plate every day once they became adults. The progeny were counted at the L2 or L3 stage.

For a growth alteration assay, on the 4th day of adulthood, worms were photographed and their body length was analyzed by using Nikon software (Nikon, Japan).

For a body movement assay, age-synchronized N2 worms (n = 10) were bred on NGM plates with or without 150 μg/ml JPYW. On the 7th day of adulthood, their body movements expressed as the travel distance were recorded under an inverted microscope for 20 s in fresh plates, and were analyzed by using Nikon software.

The fluorescence intensity of lipofuscin and autofluorescence were assessed in the worms on the 10th day of adulthood, and were quantified using ImageJ to determine the average pixel intensity. All tests were repeated more than 2 times.

Quantitative analysis of aging-related genes in C. elegans

Age-synchronized N2 worms were treated with 150 μg/ml JPYW or vehicle at 20 °C until the 4th day after the worms reached adulthood. Total RNA was extracted from approximately 600 worms per group with TRIzol (TaKaRa, Beijing, China). For RNA extraction and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), more detailed steps have been described in the previous study [26]. Briefly, the collected worms were moved to 1.5-ml RNase-free microfuge tubes to extract RNA and the RNA concentration was quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized by reverse transcription using a PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time; TaKaRa, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed using TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNase H Plus; TaKaRa, Beijing, China) with SuperReal PreMix Plus (SYBR Green; TaKaRa, Beijing, China). The primers were as follows: act-1, 5-TCCCTCTCCACCTTCCAACA-3 (forward) and 5-GCACTTGCGGTGAACGATG-3 (reverse); skn-1, 5-CCAGTGACAACGAGCTTCCA-3 (forward) and 5-GTGACGATCCGTGCGTCTTT (reverse); clk-2, 5-ACTCCGATCTACTCGCCTCA-3 (forward) and 5-GATGCAGGCAGTCCGTAGTT-3 (reverse); sod-3, 5′-CCAACCAGCGCTGAAATTCAATGG-3′ (forward) and 5′- GGAACCGAAGTCGCGCTTAATAGT-3′ (reverse); daf-16, 5′- CCAGACGGAAGGCTTAAACT-3′ (forward) and 5′-ATTCGCATGAAACGAGAATG-3′ (reverse). The cDNA was produced using random 6-mers and oligo (dT) primers. qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR green as the detection method. The comparative 2−ΔΔCT method was used to assess the expression levels of each mRNA relative to those of act-1. The test was performed in triplicate.

Statistical analyses

All the datas in the study were analyzed by using GraphPad Prism 6.0. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and log-rank test were conducted for the lifespan assay. Student’s t-test was used for comparing two datasets. For all the datas, the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) were analyzed. P values < 0.05 were considered to indicate significance.

Results

Effects of JPYW on lifespan extension and stress resistance

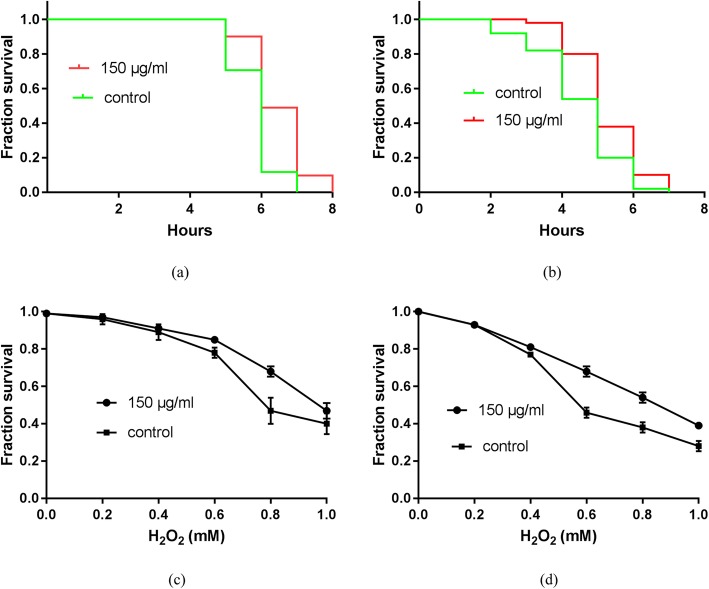

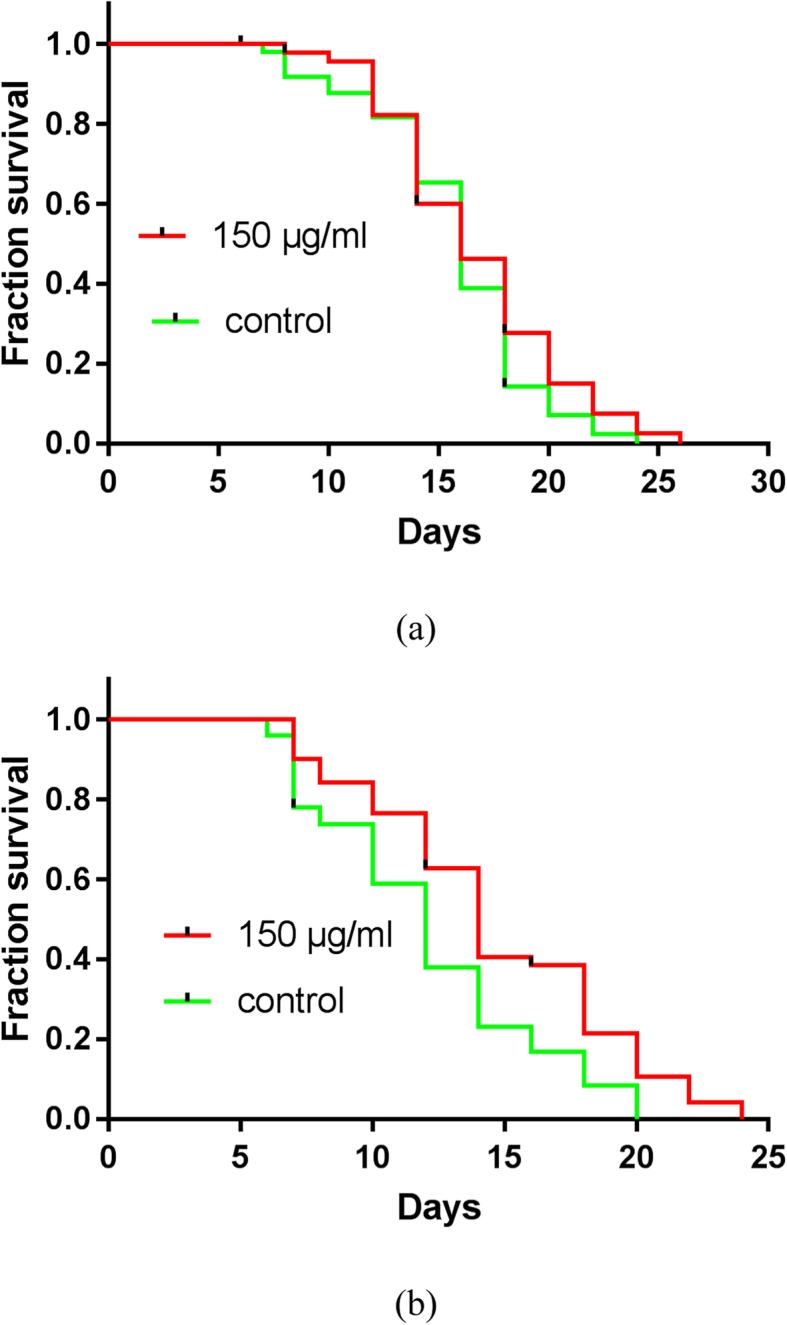

To determine the lifespan-extending properties of JPYW, lifespan assays were performed using wild-type worms with or without 150 μg/ml JPYW treatment. We found significantly more worms in the old-age phase among the JPYW-treated worms than among the controls (Fig. 1a). Therefore, we hypothesized that JPYW may affect the lifespan of worms without affecting worm development. We subsequently used aged wild-type worms (7-day-old adult worms) as the experimental models for the lifespan assay. Interestingly, after 7 days of treatment, there was a significant difference between the JPYW group and the control group for every day; in addition, compared to control worms, JPYW-treated worms displayed significant increases in lifespan (11.86 ± 4.24 vs. 14.49 ± 4.78 days, P < 0.05) (Fig. 1b). To evaluate stress resistance, we performed heat stress assays and oxidative stress assays using wild-type worms with or without 150 μg/ml JPYW treatment. As shown in Fig. 2a, compared to control worms, 150 μg/ml JPYW-treated worms had a significantly increased mean lifespan during heat stress (5.82 ± 0.62 vs. 6.49 ± 0.81 h, P < 0.01). Thermotolerance was also elevated in aged worms. As shown in Fig. 2b, compared to the control treatment, JPYW treatment significantly increased the survival rate in aged worms (4.50 ± 1.20 vs. 5.29 ± 0.97 h, P < 0.01). Then, we determined whether JPYW also exerted protective effects on wild-type and aged worms under oxidative stress conditions. Interestingly, compared to the control treatment, JPYW treatment improved survival under mild to moderate oxidative stress but did not improve survival under severe oxidative stress. The results showed that JPYW-treated wild-type worms lived longer than control vehicle-treated worms under 0.6 to 0.8 mM hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress (Fig. 2c). Significant differences were also observed between aged wild-type worms and aged control worms under 0.4 to 1.0 mM hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 1.

Effect of JPYW on the lifespan of C. elegans N2 worms under normal conditions. a The worms were treated with JPYW beginning at the larval stage. The curves show the percentages of surviving worms on different days after treatment with a vehicle control (1% DMSO) or 150 μg/ml JPYW. JPYW did not significantly prolong the lifespan of wild-type worms, but it caused a positive trend in the number of surviving aged worms (n = 50). b The aged worms were exposed to JPYW beginning on the 7th day of adulthood. The curves show the percentages of surviving worms on different days after treatment with a vehicle control (1% DMSO) or 150 μg/ml JPYW. JPYW significantly prolonged the lifespan of aged wild-type worms; n = 50–51, P < 0.05

Fig. 2.

The effect of JPYW on stress resistance in C. elegans N2 worms. a Heat stress resistance in wild-type larvae. Wild-type worms that were incubated at a constant temperature (37 °C) were pretreated with 150 μg/ml JPYW or vehicle control (1% DMSO). Survival was assessed every hour after heat stress treatment. JPYW significantly prolonged the lifespan of wild-type worms under heat stress compared to the vehicle control (n = 50–55, P < 0.05). b Heat stress resistance in aged C. elegans N2 worms. Aged worms that were incubated at a constant temperature (37 °C) were pretreated with 150 μg/ml JPYW or vehicle control (1% DMSO). Survival was assessed every hour after heat stress treatment. JPYW treatment significantly prolonged the lifespan of aged wild-type worms under heat stress compared to the control treatment (n = 50–55, P < 0.05). c Oxidative stress resistance in C. elegans N2 worms. Wild-type worms were pretreated with 150 μg/ml JPYW or vehicle control (1% DMSO) and were exposed to various concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1 mM). Survival was assessed after 15 h of each treatment. d Oxidative stress resistance in aged C. elegans N2 worms. Aged worms were pretreated with 150 μg/ml JPYW or vehicle control (1% DMSO) and were exposed to various concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1 mM). Survival was assessed after 15 h of each treatment

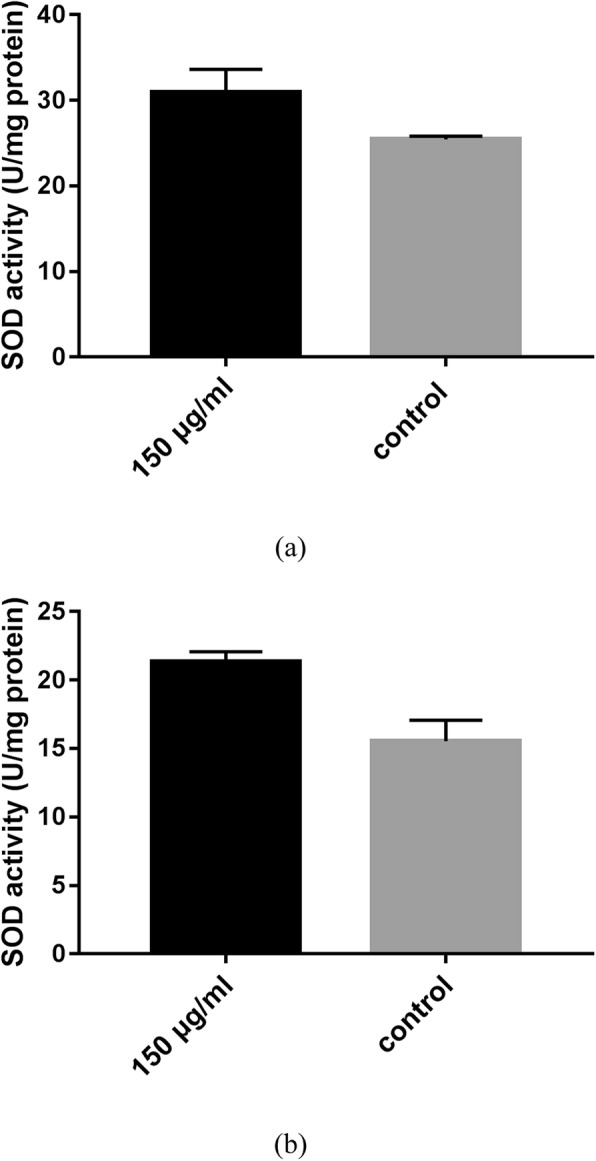

Effects of JPYW on antioxidant enzyme activity

To verify the possible mechanism by which JPYW mediated longevity extension and elevated stress tolerance, the activity of individual stress resistance proteins was investigated in wild-type worms and aged worms. In this study, we assessed the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD. As shown in Fig. 3a and b, SOD was significantly upregulated in the presence of 150 μg/ml JPYW in both wild-type and aged worms compared to controls (P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Effect of JPYW on SOD activity in C. elegans N2 worms. a SOD activity in C. elegans N2 worms. Quantitative comparisons showed that SOD levels were significantly higher in JPYW-pretreated worms than in control worms (25.44 ± 0.22 vs. 30.96 ± 1.53 U/mg of protein, P < 0.05). b SOD activity in aged C. elegans N2 worms. Quantitative comparisons showed that SOD levels were significantly higher in JPYW-pretreated aged worms than in control worms (15.54 ± 1.09 vs. 21.35 ± 0.52 U/mg of protein, P < 0.05)

Effects of JPYW on aging-related factors

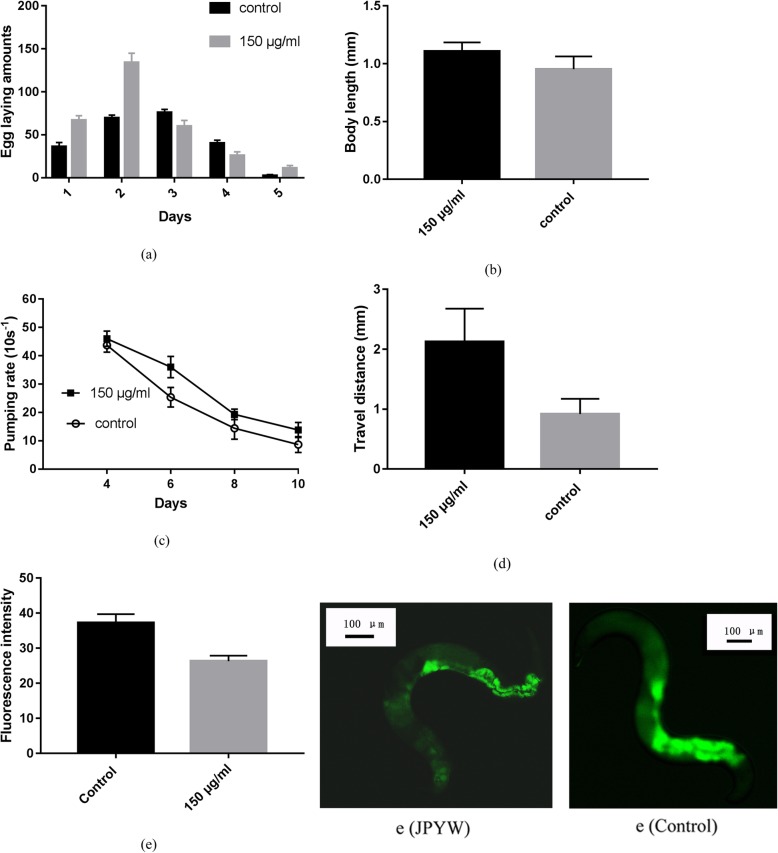

Previous study has indicated that lifespan was associated with reproduction, pharyngeal pumping, body size and motility in many species, such as C. elegans [27]. In this study, we found that JPYW treatment significantly increased the total number of progeny compared to the control treatment (297.4 ± 15.3 vs. 223.8 ± 6.3 progeny, n = 5, P < 0.01, Fig. 4a). In addition, a significant change in worm body length was detected after JPYW exposure (0.953 ± 0.035 vs. 1.108 ± 0.024 mm, n = 10, P < 0.05, Fig. 4b), suggesting that JPYW activity affects growth as well as fertility (Fig. 4a). Then, we assessed the muscle activity and the movement ability of the worms by recording the rate of pharyngeal pumping. The graph in Fig. 4c showed that the rate of pharyngeal contractions declined gradually with increasing age, and this aging-associated decline was attenuated by JPYW treatment compared to the control treatment (Fig. 4c). Then, we measured the body movements to estimate the healthspan of aged worms (worms that had been adults for more than 7 days) by recording the distances the worms traveled over 20 s. As shown in Fig. 4d, worm body movement was significantly higher in the JPYW group than in the untreated control group (0.92 ± 0.08 vs. 2.13 ± 0.18 mm, n = 10, P < 0.01), suggesting that the functional aging of worms is strongly delayed by JPYW. As shown in Fig. 4e, the fluorescence intensity of intestinal lipofuscin was significantly attenuated in the JPYW group compared to the control group (37.29 ± 0.54 vs. 26.32 ± 0.35, n = 20, P < 0.01).

Fig. 4.

Effect of JPYW on aging-related factors. a Daily and total reproductive outputs. The progeny were counted at the L2 or L3 stage. JPYW treatment significantly increased the total progeny number (297.4 ± 15.3 vs. 223.8 ± 6.3, n = 5, P < 0.01) compared to the control treatment. b For the growth alteration assay, photographs were taken of the worms, and the body length of each animal was analyzed. A small but significant change in body length was detected after JPYW treatment compared to the control treatment (0.953 ± 0.035 vs. 1.108 ± 0.024 mm, n = 10, P < 0.05). c JPYW slowed the decline in pharyngeal pumping during aging. Worms were treated with 150 μg/ml JPYW and the pumping rates (pumps per 10 s) of 10 animals were scored in two trials (untreated vs. treated: day 6, P < 0.05; day 8, P < 0.05; day 10, P < 0.05; n = 10). d Body movement in wild-type N2 nematodes. Worm body movement was evaluated under a dissecting microscope for 20 s. The differences between the JPYW-treated worms and controls were significant (0.92 ± 0.08 vs. 2.13 ± 0.18 mm, n = 10, P < 0.01). e Fluorescence intensity of lipofuscin and autofluorescence on the 10th day of adulthood. Compared to that in control worms, the intestinal lipofuscin accumulation in JPYW-treated worms was reduced (37.29 ± 0.54 vs. 26.32 ± 0.35, n = 20, P < 0.01)

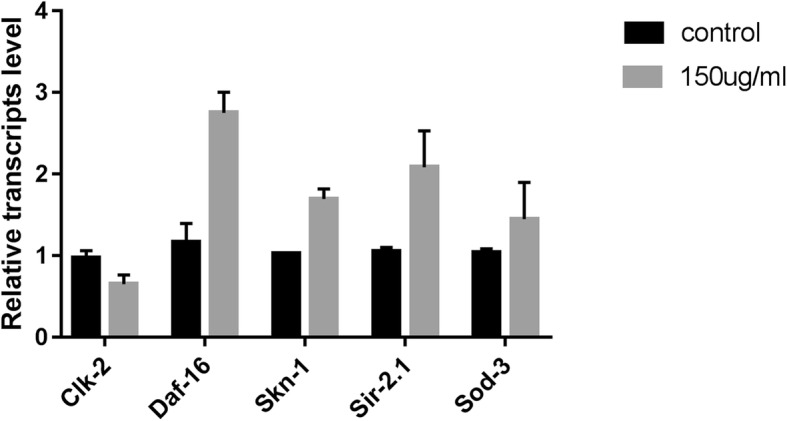

Effects of JPYW on aging-related gene expression

Pathways for the induction of stress-response genes that affect lifespan have been identified in C. elegans. JPYW treatment might improve survival by activating these genes. Treatment with JPYW can increase C. elegans lifespan through sir-2.1, which regulates this effect through kat-1-mediated fatty acid oxidation [28]. As shown in Fig. 5a, the expression level of the sir-2.1 gene was significantly upregulated in JPYW-treated worms compared to control-treated worms. In C. elegans, two transcription factors, daf-16 and skn-1, promote the expression of antioxidant or detoxification enzymes, enhance stress resistance and increase lifespan [29, 30]. JPYW treatment significantly increased the expression levels of the daf-16 and skn-1 genes compared to the control treatment, suggesting that JPYW may act in a manner that is dependent on these genes (Fig. 5a). JPYW treatment also significantly downregulated the expression level of clk-2 compared to the control treatment, which may have slowed the shortening of telomere length in the JPYW-treated worms, resulting in increased lifespan. Surprisingly, compared to the vehicle control, JPYW significantly increased SOD activity, but it did not increase the expression of the sod-3 gene.

Fig. 5.

Effects of JPYW treatment on the expression of aging-related genes. The expression levels of aging-related genes were determined by qRT-PCR using the 2−ΔΔCT method in worms with or without 150 μg/ml JPYW treatment at 20 °C. The graph shows the mean and SEM values from two independent experiments. Compared to the control treatment, JPYW treatment significantly changed the expression levels of the genes daf-16, clk-2, skn-1 and sir-2.1 (P < 0.05), but not those of the gene sod-3 (P > 0.05)

Discussion

In the present study, one control group (1% DMSO) and one experimental group (150 μg/ml) were used to explore the antiaging effects of JPYW and their underlying mechanisms in a C. elegans model. Since the experiments were not designed as noninferiority tests or superiority tests, a positive control group was not used. Each test in the study was performed at least two times to control for random effects and to ensure the repeatability and accuracy of the results. We found that JPYW treatment significantly prolonged the lifespan of wild-type worms under stress conditions. In addition, the lifespan of aged worms increased more significantly than that of wild-type worms under both normal and stress conditions. This result indicates that JPYW may have a strong antiaging effect and that JPYW therapy may be a useful antiaging treatment. As previously reported, most of the plants in JPYW have antiaging effects. For instance, P. ginseng C. A. Mey, one of the main herbs in this formula, has been proven to be very effective in delaying senility [31], and ginsenosides, the active ingredients in P. ginseng, have been proven to promote development and growth and to prolong lifespan of C. elegans [32]. In addition, ginsenoside Rg1, the main active pharmaceutical ingredient in P. ginseng, has been found to improve the antiaging ability of the hematopoietic microenvironment by enhancing the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capacities of bone marrow stromal cells in a D-galactose-induced aged rat model and also to act on hematopoietic cells to protect them from aging [33, 34]. Pachymic acid, a main compound in P. cocos, can induce autophagy via the IGF-1 signaling pathway in aged cells to delay the aging process [35]. Additionally, nobiletin, an active ingredient in Pericarpium Citri Reticulatae, may ameliorate isoflurane-induced cognitive impairment and delay the aging process through antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic effects via modulation of Akt, Bax, pCREB and BDNF in aging rats [36]. Finally, C. cassia Presl can increase C. elegans lifespan via insulin signaling and stress-response pathways [37], and the major chemical components of C. cassia, cinnamates, may promote adiponectin production during adipogenesis in human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells and prevent skin aging [38]. JPYW may thus exert antiaging effects through the combined effects of all of its components.

Recently, antiaging medicine has aimed at not only simply increasing longevity but also extending healthspan. In this study, we showed that JPYW treatment effectively delayed aging-related declines in function, such as pharyngeal pumping, body movement, egg laying and development, compared with the control treatment, indicating that JPYW can enhance the healthspan of worms.

To explore the potential mechanisms by which JPYW exerts antiaging effects, SOD activity and aging-related gene expression were assessed in C. elegans. As was reported in the previous studies [39, 40], the oxidative stress caused by oxygen free radicals played an important role in aging, and eliminating free radical and enhancing oxidative stress resistance could delay senility. Our research indicated that compared to the control treatment, JPYW treatment elevated the activity of an antioxidant enzyme (SOD), which resulted in elimination of oxygen free radicals that might contribute to aging. Notably, previous studies have revealed that gene expression can change during aging in C. elegans. Using qRT-PCR, we confirmed that compared to control-treated worms, JPYW-treated worms exhibited upregulated expression of the antiaging genes daf-16, skn-1, and sir-2.1 and downregulated expression of the proaging gene clk-2, while they did not exhibit changes in the antiaging gene sod-3. Overall, four key genes are involved in the ameliorative effects of JPYW on the aging pathway. The first, daf-16 [41], is a part of FOXO-family transcriptional factor, which can regulate many target genes that can improve stress resistance and increase longevity. The second, sir-2.1 [42, 43] belongs to NAD+-dependent histone deacetylases, which involves in regulating lifespan conservatively. As was previously reported, overexpression of sir-2.1 can extend the longevity of C. elegans by suppressing the IIS pathway or activating daf-16. The third, skn-1 [44], involves in regulating oxidative stress resistance and lifespan by encoding a worm homolog of Nrf2. The fourth key gene, clk2 [45], reduces longevity and telomere length.

In the present study, JPYW upregulated the activity of the antioxidant enzyme SOD but did not significantly increase the expression of the relevant gene sod-3. This finding indicates that protein expression did not correlate with gene expression, which is an intriguing and unexplained phenomenon. The precise mechanisms underlying these results are uncertain, but it is known that some proteins are not encoded by only single genes. For example, SOD is encoded not only by the gene sod-3 but also by the genes sod-2, sod-1, etc. In addition, the process of gene regulation is complex and unclear. This issue requires further study, and this discrepancy is one of the limitations of our study. In addition, JPYW is a Chinese herbal compound that contains many complex components, such as steroid-like compounds, but no specific compound extracted from JPYW was tested in this study. Hence, it is not clear how many ingredients were related to the observed antiaging effects or how these active ingredients may have interacted. This uncertainty is another limitation of the present study. Further studies are warranted to identify the active ingredients in JPYW.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that JPYW, a TCM formula, increases stress resistance and promotes longevity in C. elegans by activating and repressing target genes related to aging, including daf-16, sir-2.1, skn-1 and clk-2.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted at the Key Laboratory of the Neurology Department, The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University for Model Organisms and the Lingnan Medical Research Center of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China. The authors are grateful to Professor Qiuying Xu, Dr. Simei Long and Fengyin Liang for their technical support and assistance.

Abbreviations

- BCA

Bicinchoninic acid

- C. elegans

Caenorhabditis elegans

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- CFDA

China food and drug administration

- CGC

Caenorhabditis genetics center

- DMSO

Dimethylsulfoxide

- EDTA

Ethylenedinitrilotetraacetic acid

- JPYW

Jianpi-yangwei

- NGM

Nematode growth medium

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- TCM

Traditional Chinese medicine

- Tris-HCl

Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane hydrochloride

- T-SOD

Total superoxide dismutase

Authors’ contributions

ZLL, XFP and YZM conceived and designed the study. ZLL, YTC, CZW, SC and FSY performed the experiments. ZLL and XFP wrote the manuscript. ZLL, YZM and PZ analyzed the data. ZLL, FSY and YTC searched and reviewed the literature. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Guangdong Provincial Hospital of the Traditional Chinese Medicine Scientific and Technological research of China (no. YN2015QN08), the National Key Research and Development Plan for the 13th Five-Year Plan (no. 2018YFC1705600), and the Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81503515). None of the funding agencies participated in the study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available since a follow-up study is undergoing, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Liling Zeng, Email: Liling.zeng@yale.edu.

Zhimin Yang, Email: yangyo@vip.tom.com.

Tianchan Yun, Email: yuntc92@163.com.

Shaoyi Fan, Email: 408671469@qq.com.

Zhong Pei, Email: peizhong@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Ziwen Chen, Email: 651061776@qq.com.

Chen Sun, Email: sunchen87319@163.com.

Fuping Xu, Email: xufuping163@163.com.

References

- 1.Harman D. Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J Gerontol. 1956;11(3):298–300. doi: 10.1093/geronj/11.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MSN N, Longo-Mbenza B, Adeniyi OV, et al. Ageing, exposure to pollution, and interactions between climate change and local seasons as oxidant conditions predicting incident hematologic malignancy at KINSHASA University clinics, Democratic Republic of CONGO (DRC) BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):559. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3547-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bijnens EM, Zeegers MP, Derom C, et al. Telomere tracking from birth to adulthood and residential traffic exposure. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):205. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0964-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calder PC, Bosco N, Bourdet-Sicard R, et al. Health relevance of the modification of low grade inflammation in ageing (inflammageing) and the role of nutrition. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;40:95–119. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villa F, Carrizzo A, Spinelli CC, et al. Genetic analysis reveals a longevity-associated protein modulating endothelial function and angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2015;117(4):333–345. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krut'ko VN, Dontsov VI, Khalyavkin AV, Markova AM. Natural aging as as a sequential poly-systemic syndrome. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2018;23:909–920. doi: 10.2741/4624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gladyshev TV, Gladyshev VN. A disease or not a disease? Aging as a pathology. Trends Mol Med. 2016;22(12):995–996. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellantuono I. Find drugs that delay many diseases of old age. Nature. 2018;554(7692):293–295. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-01668-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savage N. New tricks from old dogs join the fight against ageing. Nature. 2017;552(7684):S57–S59. doi: 10.1038/d41586-017-08387-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J, Peng L, Huang W, et al. Balancing between aging and Cancer: molecular genetics meets traditional Chinese medicine. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118(9):2581–2586. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen KJ. Reflections on human longevity and Chinese medicine prevention and treatment of chronic diseases. Chin J Integr Med. 2015;21(9):643–647. doi: 10.1007/s11655-015-2286-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang ZH, Yin DZ. Preventive treatment of traditional Chinese medicine as antistress and antiaging strategy. Rejuvenation Res. 2010;13(2–3):248–252. doi: 10.1089/rej.2009.0867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou DH. Preventive geriatrics: an overview from traditional Chinese medicine. Am J Chin Med. 1982;10(1–4):32–39. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X82000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu YC, Chiu CJ, Wray LA, Beverly EA, Tseng SP. Impact of traditional Chinese medicine on age trajectories of health: evidence from the Taiwan longitudinal study on aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(2):351–357. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan F, Zhi D, Liu D, et al. Lifespan extension in Caenorhabiditis elegans by several traditional Chinese medicine formulas. Biogerontology. 2014;15(4):377–387. doi: 10.1007/s10522-014-9508-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan GR, Zong WJ, Wang XL. Effect of yishen jianpi drugs on T lymphocyte subsets, soluble interleukin-2 receptor and red blood cell immunity of senile deficiency syndrome patients. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 1995;15(1):18–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang JY, Tao DQ, Liu S, Zhang S, Ma W, Shi ZH. Effects of three Wenyang Jianpi Tang on cell proliferation and apoptosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver cells. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2017;42(8):1591–1596. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20170222.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng W, Zhang S, Zhang Z, et al. Jianpi Jiedu decoction, a traditional Chinese medicine formula, inhibits tumorigenesis, metastasis, and angiogenesis through the mTOR/HIF-1alpha/VEGF pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;224:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Chao, Zhu Zhongkai, Cao Xiyue, Chen Xingfu, Fu Yuping, Chen Zhengli, Li Lixia, Song Xu, Jia Renyong, Yin Zhongqiong, Ye Gang, Feng Bin, Zou Yuanfeng. A Pectic Polysaccharide from Sijunzi Decoction Promotes the Antioxidant Defenses of SW480 Cells. Molecules. 2017;22(8):1341. doi: 10.3390/molecules22081341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao AG, Zhao HL, Jin XJ, Yang JK, Tang LD. Effects of Chinese Jianpi herbs on cell apoptosis and related gene expression in human gastric cancer grafted onto nude mice. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8(5):792–796. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i5.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gong YX, Sun Y, Lin AP. Comparative study on the anti-free-radical damage by vital energy-reinforcing method and blood-tonifying method. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 1993;18(7):438–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi XY, Zhao FZ, Dai X, Ma LS, Dong XY, Fang J. Effect of jianpiyiwei capsule on gastric precancerous lesions in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8(4):608–612. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i4.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guarente L, Kenyon C. Genetic pathways that regulate ageing in model organisms. Nature. 2000;408(6809):255–262. doi: 10.1038/35041700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sluder AE, Baumeister R. From genes to drugs: target validation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2004;1(2):171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munoz MJ, Riddle DL. Positive selection of Caenorhabditis elegans mutants with increased stress resistance and longevity. Genetics. 2003;163(1):171–180. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng L, Sun C, Pei Z, et al. Liangyi Gao extends lifespan and exerts an antiaging effect in Caenorhabditis elegans by modulating DAF-16/FOXO. Biogerontology. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Xian B, Shen J, Chen W, et al. WormFarm: a quantitative control and measurement device toward automated Caenorhabditis elegans aging analysis. Aging Cell. 2013;12(3):398–409. doi: 10.1111/acel.12063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berdichevsky A, Nedelcu S, Boulias K, Bishop NA, Guarente L, Horvitz HR. 3-Ketoacyl thiolase delays aging of Caenorhabditis elegans and is required for lifespan extension mediated by sir-2.1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(44):18927–18932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013854107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukhopadhyay A, Oh SW, Tissenbaum HA. Worming pathways to and from DAF-16/FOXO. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41(10):928–934. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chavez V, Mohri-Shiomi A, Maadani A, Vega LA, Garsin DA. Oxidative stress enzymes are required for DAF-16-mediated immunity due to generation of reactive oxygen species by Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2007;176(3):1567–1577. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.072587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y, Ren C, Zhang Y, Wu X. Ginseng: an nonnegligible natural remedy for healthy aging. Aging Dis. 2017;8(6):708–720. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.0707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JH, Choi SH, Kwon OS, et al. Effects of ginsenosides, active ingredients of Panax ginseng, on development, growth, and life span of Caenorhabditis elegans. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30(11):2126–2134. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu W, Jing P, Wang L, Zhang Y, Yong J, Wang Y. The positive effects of Ginsenoside Rg1 upon the hematopoietic microenvironment in a D-Galactose-induced aged rat model. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:119. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0642-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Y, Liu J, Cai S, Liu D, Jiang R, Wang Y. Protective effects of ginsenoside Rg1 on aging Sca-1(+) hematopoietic cells. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12(3):3621–3628. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee SG, Kim MM. Pachymic acid promotes induction of autophagy related to IGF-1 signaling pathway in WI-38 cells. Phytomedicine. 2017;36:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bi J, Zhang H, Lu J, Lei W. Nobiletin ameliorates isoflurane-induced cognitive impairment via antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects in aging rats. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14(6):5408–5414. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu YB, Dosanjh L, Lao L, Tan M, Shim BS, Luo Y. Cinnamomum cassia bark in two herbal formulas increases life span in Caenorhabditis elegans via insulin signaling and stress response pathways. PLoS One. 2010;5(2):e9339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rho HS, Hong SH, Park J, et al. Kojyl cinnamate ester derivatives promote adiponectin production during adipogenesis in human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24(9):2141–2145. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408(6809):239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bokov A, Chaudhuri A, Richardson A. The role of oxidative damage and stress in aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125(10–11):811–826. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy CT, McCarroll SA, Bargmann CI, et al. Genes that act downstream of DAF-16 to influence the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2003;424(6946):277–283. doi: 10.1038/nature01789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tissenbaum HA, Guarente L. Increased dosage of a sir-2 gene extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2001;410(6825):227–230. doi: 10.1038/35065638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berdichevsky A, Viswanathan M, Horvitz HR, Guarente L. C. elegans SIR-2.1 interacts with 14-3-3 proteins to activate DAF-16 and extend life span. Cell. 2006;125(6):1165–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park SK, Tedesco PM, Johnson TE. Oxidative stress and longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans as mediated by SKN-1. Aging Cell. 2009;8(3):258–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benard C, McCright B, Zhang Y, Felkai S, Lakowski B, Hekimi S. The C. Elegans maternal-effect gene clk-2 is essential for embryonic development, encodes a protein homologous to yeast Tel2p and affects telomere length. Development. 2001;128(20):4045–4055. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.20.4045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available since a follow-up study is undergoing, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.