Abstract

Despite the documented and well-publicized health and well-being benefits of regular physical activity (PA), low rates of participation have persisted among American older adults. Peer-based intervention strategies may be an important component of PA interventions, yet there is inconsistent and overlapping terminology and a lack of clear frameworks to provide a general understanding of what peer-based programs are exactly and what they aim to accomplish in the current gerontological, health promotion literature. Therefore, a group of researchers from the Boston Roybal Center for Active Lifestyle Interventions (RALI) collaborated on this paper with the goals to: (a) propose a typology of peer-based intervention strategies for use in the PA promotion literature and a variety of modifiable design characteristics, (b) situate peer-based strategies within a broader conceptual framework, and (c) provide practice guidelines for designing, implementing, and reporting peer-based PA programs with older adults. We advance clarity and a common terminology and highlight key decision points that offer guidance for researchers and practitioners in using peers in their health promotions efforts, and anticipate that it will facilitate appropriate selection, application, and reporting of relevant approaches in future research and implementation work.

Keywords: Physical activity behavior, Peer mentors, Peer coaching, Intervention

Promoting and sustaining regular engagement in physical activity (PA) continues to be a prominent public health issue. Despite the well-documented health and well-being benefits of regular PA, low rates of participation have persisted among American midlife and older adults. Although estimates range, some studies have reported that as few as 27% of those aged 65 years and older in the United States meet the recommended minimal PA guideline of 150 min/week of moderate-to-vigorous PA (Keadle, McKinnon, Graubard, & Troiano, 2016). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Centers for Disease Control, 2016), 28% of the individuals aged 50 years or older in the United States are not physically active beyond the basic movements needed for daily life activities and these rates were higher for women (29.4%), racial and ethnic minorities (Hispanics, 32.7% and non-Hispanic blacks, 33.1%), those aged 75 years or older (35.3%) and those with at least one chronic disease (31.9%). A sedentary lifestyle increases the risk for adverse physical and cognitive outcomes including chronic diseases such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, dementia, and some cancers, disability and premature death (CDC, 2016).

There is clearly no one-size-fits all approach to PA promotion among older adults, but many interventions have been developed. Chase (2013), in a systematic review of PA interventions with older adults, characterized interventions into two general categories: (a) behavioral strategies that introduce observable and participatory physical actions to promote behavior change, e.g., technology-based approaches that involve prompting and self-monitoring (e.g., Bickmore et al., 2013; O’Reilly & Spruijt-Metz, 2013; Sullivan & Lachman, 2016), and (b) cognitive strategies that aim to alter or enhance thought processes, attitudes, or beliefs related to a specific behavior in order to achieve behavior change, e.g., education and goal-setting activities, and barrier identification and management (e.g., Brodie & Inoue, 2005; Pinto, Goldstein, Ashba, Sciamanna, & Jette, 2005). Social strategies, and particularly peer-based strategies, may be an important yet often overlooked component of PA interventions (Ginis, Nigg, & Smith, 2013). One recent study found that older adults watch three times more TV than any other age group and they seem to enjoy it less than their younger counterparts (Depp, Schkade, Thompson, & Jeste, 2010). Other research (Reed, Crespo, Harvey, & Andersen, 2011) suggests that sedentary life styles in older adulthood correlate with social isolation, and carry a mortality risk like smoking (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010). Thus, it is possible that peer-based strategies that embed behavior-change within a context of peer support may not only be health-promoting on multiple levels (i.e., physically, cognitively, socially, emotionally), but also may be more likely to contribute to sustained behavior change over time.

Peer-based interventions, not limited to PA, have been utilized in a wide variety of settings ranging from support for people with similar life experiences (e.g., death of child or spouse, common chronic illness, substance abuse, etc.) to leadership from an aspirational peer example. These approaches provide guidance in the workplace (e.g., peer mentoring/coaching) and to peer-led or peer-supported health promotion program delivery (e.g., Matter of Balance; Tennstedt et al., 1998). In many contexts, peers have been shown to be important in moving people toward desired goal achievement (e.g., Layne et al., 2008).

Peer-based intervention strategies to promote PA among older adults may include a wide range of approaches that leverage the power of relationships to facilitate behavior change with peers providing knowledge, experience and emotional, social or practical help to each other (Mead, Hilton, & Curtis, 2001). Some studies have shown the effectiveness of peer-based strategies for facilitating and sustaining behavior change when it comes to increasing PA. In a systematic review of the effects of peer-based interventions on PA behavior, Ginis and colleagues (2013) found that peer-based interventions were just as effective as professionally delivered interventions and more effective than control conditions for increasing PA. In contrast, Kullgren and colleagues (2014) found that peer support (i.e., linkage to a peer network of four others through an online message board) delivered through eHealth technology was not effective in getting older adults to walk more. Inconsistent and overlapping terminology on peer-based PA promotion among older adults presents an important problem in the literature, however, and may contribute to the somewhat mixed research findings (e.g., how did factors such as modality or the passive vs active role of the peers in these “peer networks” have an impact on outcome?).

Problems with Terminology and Comparability

A variety of terms and ideas exist for peer-based approaches within the PA promotion arena, e.g., peer support, peer coach/mentor, peer counselor, peer-delivered programming (sometimes referred to as lay-led, consumer-led, peer-led), peer intervener, peer educator, or peer volunteer, among others. Terms in the literature are often used generically and interchangeably with few explicit definitions or consistent agreement on what a given peer role involves and what are the expectations (e.g., Is there a difference between activities performed by a peer mentor versus a peer coach?). Also, lack of clarity or comparability can also occur as a result of key differences in design characteristics of peer programs. Prior work has reported a variety of approaches including telephone call advisement, peer-delivered, peer-led group exercise classes, peer coparticipants, and face-to-face encounters providing informational and emotional support (Ginis et al., 2013). Furthermore, the rationale for using peers is often not a theory-based rationale for why the given peer-based strategy would be expected to have an influence on the desired outcomes, but rather, factors such as cost-effectiveness (e.g., ability to improve translation of evidence-based PA programs for older adults), acceptability of peers (e.g., some individuals more open to learning from a peer than from a professional), and benefits to the peer themselves are cited as rationale (Ginis et al., 2013; Simoni, Franks, Lehavot, & Yard, 2011).

Lack of clarity around these issues challenges achieving consensus about terminology and approaches for research and practice, and makes it confusing when deciding on a course of action. Without a clear framework to provide a general understanding of what peer-based programs are exactly and what they aim to accomplish, the process of evaluating and comparing programs is impeded, jeopardizing the benefits and sustainability of existing programs and funding of new programs. Situating peer-based strategies in a broader theoretical framework and providing practical guidelines for designing and implementing peer-based strategies for PA-promotion interventions with older adults is important to enhance our understanding of why peer-based strategies may be implemented successfully in one setting, but not in another—a top-priority in implementation research (Kirk et al., 2016). The approach enables researchers to fully translate effective peer-based interventions and to close gaps in the scientific pipeline between evidence impact and widespread uptake.

The current paper is the product of an interdisciplinary collaboration of researchers from the Boston Roybal Center for Active Lifestyle Interventions (RALI), who had received support to conduct three pilot intervention studies aimed at promoting PA among older adults (Castaneda-Sceppa, Cloutier, Isaacowitz, & John, under review; Matz-Costa, Lubben, Lachman, Lee, & Choi, under review; Howard & Louvar, 2017). This RALI working group was formed in 2017 as a result of our collective observations regarding the lack of consistency and guidance in the design, application, and reporting of peer-based intervention strategies in the current literature. In order to fill this gap, the specific goals of this paper are to: (a) articulate a typology with concise definitions of several commonly employed peer-based intervention strategies in the PA promotion literature as well as additional design characteristics that should be considered, (b) situate peer-based strategies within a broader conceptual framework, and (c) provide practice guidelines for designing and implementing peer-based PA programs with older adults. The establishment of a common terminology and framework around peer-based PA strategies will facilitate appropriate selection and application of relevant approaches in implementation studies and will foster cross-disciplinary dialogue among implementation researchers.

Toward a Typology of Peer-Based Intervention Strategies

Defining Peer-Based Strategies

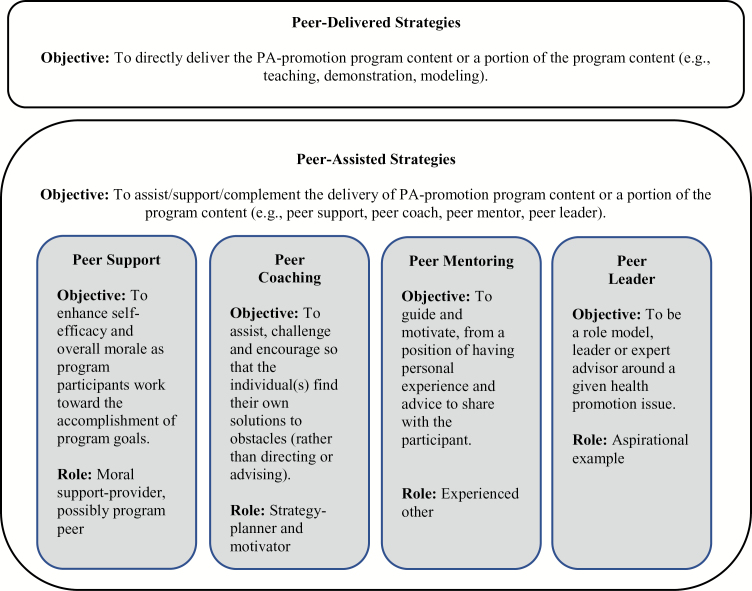

A review of the PA intervention literature using peers revealed that peer-based strategies are usually conceptualized in two distinct ways. The first conceptualization, we refer to as the peer-delivered intervention approach, and the second as the peer-assisted approach (see Figure 1). The functional purpose of the peer differs in each approach. In the peer-delivered approach, the goal is to directly deliver the PA-promotion program content or a portion of the program content (e.g., teaching, demonstration, modeling). By contrast, the goal of peer-assisted approach is to assist, support, or complement the delivery of a PA-promotion program content or a portion of the program content (e.g., peer support, peer coach, peer mentor, peer leader). It is possible for a peer-based strategy to be a hybrid of these two approaches. It is important to note that while we are proposing that these could be useful distinctions in clarifying the functional purpose of peers in studies moving forward, these distinctions have not necessarily been explicated in the existing literature.

Figure 1.

A typology for peer-based intervention strategies for physical activity (PA) intervention with older adults.

Peer-Delivered Programming

Sometimes referred to as lay-led, consumer-led, or peer-led, peers in this role aim to achieve a change of a person’s knowledge, attitude, beliefs, norms, and behavior towards a healthier lifestyle by delivering the program content or a portion of the program content directly. Teaching participants how to do something or direct demonstration and performance (e.g., education, leading an aerobics class) are two examples. Dorgo, Robinson, and Bader (2009), for instance, utilized a peer-delivered intervention strategy by providing extensive training to peers who then led fitness programs for older adult program participants.

Peer-Assisted Programming

There are several ways in which peers could assist or complement the implementation of a PA intervention with older adults. Below is a defined series of roles and boundaries that we propose based loosely on prior literature. Though not a comprehensive list, it offers some examples.

Peer support

Peer support typically refers to efforts by a peer to enhance self-esteem, self-efficacy, and overall morale as program participants work toward the accomplishment of program goals as well as try to stay on track in the long term. Peers in this role are not typically positioned as experts who are role modeling in any way, but more as collaborators and problem-solvers. These peers may be going through the program themselves along-side the other(s) they are supporting. Peers in this role are “moral support providers.” In a study by Buman et al. (2011), for example, peer volunteers provided support for PA behavior change through 16 weeks of sessions with participants. Participants were encouraged to engage in a variety of lifestyle physical activities including walking and resistance exercises and peers provided different types of support (e.g., self-management skills, encouragement, regular feedback, goal setting, and problem solving) in order to improve long-term maintenance of PA for program participants.

Peer coaching

Peer coaching is a partnership that is either one-to-one or one-to-many where the coach helps the individual(s) work out what they need to do themselves to improve and, in the process, what motivates them and what gets in their way (attitudes, beliefs, etc.). A coach will assist, challenge, and encourage so that the individual(s) find their own solution (rather than directing or advising). Peer coaching may be more effective when individuals already recognize that they need to change their behaviors. Peers in this role are “strategy-planners and motivators.” van de Vijver, Wielens, Slaets, and van Bodegom (2018) describe the Vitality club, a self-sustainable group of older adults that gather every weekday to exercise coached by an older adult. The peers in this program all have experience in giving training to groups, either as instructor of some sport or yoga teacher (e.g., one was a retired athletic trainer). There was no program manual and all peer coaches used their own experience to assist the exercisers.

Peer mentoring

Peer mentoring refers to efforts that form a relationship between two individuals, in which the more experienced individual uses their greater knowledge and understanding to support, guide, and motivate the less experienced individual. Peers in this role often draw from personal experiences that they may have either because they have successfully gone through the program themselves or because they have been successful in making and sustaining healthy behavior changes. Peer mentors often offer their own advice and opinions and can be more “directive” than peer supporters or peer coaches who typically support or guide individuals in finding their own solutions. Peers in this role are “experienced others.” As one example, Castro, Pruitt, Buman, and King (2011) identified individuals who regularly engaged in at least 150 min of moderate-to-vigorous PA per week and trained them as volunteer peer mentors to provide telephone-based PA advice.

Peer leaders

Peer leaders are often those who have been provided training on how to be a role model, leader or expert advisor around a given health promotion issue. Peers in this role are “aspirational leaders.” Kerr and colleagues (2012) used peers in this capacity by identifying individuals from staff and resident recommendations, flyers, and personalized letters who were leaders in their continuing care retirement community, engaged in the programs offered at the site, and, in at the PA sites only, a good role model for PA. Peers in this instance were given a $600 personal honorarium for the 12-month study period in the intervention sites.

These peer-assistance-types of roles can be thought of along a continuum from low status/power differential (i.e., peer supporters) to higher status/power differential (i.e., peer leaders). Training needs will vary for each of these peer roles and some may require compensation, while others might not.

Additional Design Characteristics of Peer-Based Strategies

Peer-based strategies in the PA-intervention literature vary greatly across multiple dimensions. While the above proposed typology clarifies the functional purpose of peers in a PA intervention, a variety of additional design characteristics are embedded within these functions that must be considered, including the basis for the “peer” relationship, setting, modality, level of formality/structure, and peer assignment strategy. These dimensions upon which peer-strategies can vary are fundamental to our understanding of how peers operate, what contributes to their efficacy, and how to explain why some peer-based intervention strategies work and others do not. They also represent modifiable design characteristics that an interventionist or researcher could consider when designing and implementing peer-based strategies. In fact, we argue later that interventionists and researchers need to be explicit and intentional about these characteristics.

Basis for “Peer” Relationship

Peers are, by definition, persons who share some fundamental characteristic(s) with study/program participants, whether that be age, life experience(s) (e.g., caregivers, a particular chronic illness), ability level, or some other trait. The extent of shared characteristics, however often varies. For example, the relationship can be one of equality, where peers and program participants are seen as equals on all levels (e.g., in approaches where program participants serve as supportive peers to each other). On the other extreme, peers may only be of similar age and are aspirational examples. An example of a program somewhere in the middle of this continuum might be one where the peer is of similar age and is able to offer support or knowledge by virtue of relevant experience and can relate to others who are now in a similar situation (Mead et al., 2001). In some cases, it is merely the lack of professional training or status in the scope of their work (compared to nonpeer professionals) that makes someone a “peer.”

Setting

Peer-based strategies can be implemented in a variety of different settings (e.g., a clinic or hospital, at home, in the community), which may or may not enhance or inhibit the effectiveness of the peer. For example, a PA-promotion intervention with a peer-based component conducted within a medical setting might affect the credibility, perceived power differential, and garnered trust that is achieved between peers differently than if the same intervention was carried out at an individual’s home, or a community location like a Council on Aging or public library.

Modality

There are many different modalities through which a peer-based intervention component could be implemented. For example, one-on-one face-to-face, one-on-one telephone, group face-to-face, group telephone, or group internet. A peer-support model that is administered via a social media group modality between peers could be appropriate for some studies, while, depending on the goals, face-to-face, one-one-one meetings may be more appropriate for others. For instance, Colón-Semenza, Latham, Quintiliani, and Ellis (in press) developed an intervention that delivered peer content through mHealth technology targeting PA in people with Parkinson Disease.

Level of Formality/Structure

The activities that the peer is asked to perform may be largely informal and unstructured, with peers taking an active role in self-generating content, or they could be more formalized and structured, with the content and approach to be utilized by the peer being fully scripted and prescribed by the researchers or others. On the one extreme, an example of the informal approach might be when older adult study participants are matched with a peer that they meet with on a regular basis, but no guidance is provided as to how their meetings should be structured or what they should focus on in their meetings. On the other extreme, an example of a formal approach would be when peers are provided with training and a comprehensive protocol laying out what meetings with peers should look like and accomplish.

Peer assignment Strategy

Finally, one can consider the strategy with which peers are assigned to groups or people. Peers could be assigned to program participants randomly, using a convenience-based approach (e.g., a peer who lived in geographic proximity), or matched to a program participant(s) using very specific criteria (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, prior experiences, disease/condition).

Table 1 presents two case examples of PA intervention studies with older adults and specifies the various design characteristics of their peer-based components.

Table 1.

Case Examples of the Design Characteristics PA Intervention Studies with Older Adults that Used Peers

| Case Example 1: A Peer Support Approach | Case Example 2: A Hybrid Peer-delivered with Peer Support Approach | |

|---|---|---|

| The Study |

Matz-Costa et al. (under review

).

- A pilot randomized trial of an intervention to enhance the health-promoting effects of older adults’ activity portfolios - 15 adults aged 65 years or older were randomized to receive technology-assisted self-monitoring only and 15 to receive technology-assisted self-monitoring, b) psychoeducation + goal setting via a 3-hr workshop, and c) one-on-one peer support (via phone 2×/week for 3 weeks) to support goal implementation. - Primary outcome was physical activity as measured by steps per day (FITBIT® pedometers) |

Castaneda-Sceppa et al. (under review

).

- A pilot randomized trial to examined whether improved physical function from engaging in a community-based, group exercise program would favorably influence emotional regulation and free-living PA among community-dwelling frail older adults. - 20 community-dwelling frail older adults were randomized to group exercise once a week or an attention-control group on a ratio of 2:1. |

| Function/Role of Peer |

Peer-assisted strategy: Peer support

- During a 2-hr, in-person session, peers were trained to offer: (a) moral support, by being supportive and caring as their peer works toward their stated goals, (b) informational support, by providing personal life examples of success and overcoming barriers, and (c) problem-solving support, by working to facilitate a conversation or reflection to assist their peer in overcoming barriers to achieving their stated goals. Peer supporters were trained as facilitators and supporters, not teachers/motivators, and to avoid any direct teaching/advising to the program participant such as telling the program participant that what they are doing is “wrong”, or formulating goals for the program participants (i.e., program participants were to create and implement their own, personalized goals). In addition to laying out these roles and responsibilities of the peer supporter, training included an overview of the program their peers would be participating in, followed by content, discussion and role play activities on general communication and interpersonal skills, active listening, critical thinking, and strategies for engaging participants, and ethics and resources. |

Hybrid peer-delivered and peer-assisted strategy

- Participants in the exercise group met as a group once a week to perform upper and lower body strength, balance and core exercises led by a staff member in partnership with a group participant willing to serve at the “peer” for the group or liaison between the participants and the staff. This peer communicated with participants once per week during a different day from the trainer-led group exercise time when participants, peer and community-based staff gathered in the community-based organization to exercise and socialize together. Because the peer was also a program participant, they would fall into the role of peer support in our typology, in that they were helping other participants to work toward the accomplishment of their goals and providing moral support. |

| Basis for the peer relationship | Similar-age and a lack of professional training or status. Here, the aim was for the relationship to be perceived as one of equality, and for there to be a low power/status differential. Most, but not all of the peers for this study lived in the same city as the participants and peers were generally active older adults. |

Similar-age and a lack of professional training or status.

- In this instance, there was a very low power/status differential, as peers were also program participants. |

| Setting | A community-based setting that serves older adults: A Council on Aging/senior center | A community-based setting where older frail and sedentary adults were receiving support services |

| Modality |

Face-to-face, one-to-group and telephone, one-on-one

- An initial face-to-face meeting in a small group setting (one-to-group), and then subsequent one-on-one telephone sessions |

Face-to-face, one-to-group

- As cofacilitators of the exercise group once a week and informally provided support as program participants gathered in the community-based organization to exercise and socialize together. |

| Level of formality or structure |

Informal/nonstructured

- Peers were given a good deal of latitude in how they structured their interactions with their peers, so long as they maintained the facilitator/support type of role, thus the structure was informal rather than prescribed. |

Informal/nonstructured

- Peers were participants of the study who self-identified as peers to provide social support to the fellow participants; the structure was not prescribed. |

| Peer assignment strategy |

No matching, random

- Each of the five peers were randomly assigned two or three program participants, although authors did take into account requests from some peers to have two rather than three peers that they were supporting due to personal time limitations. |

No matching, self-selecting

- An individual from the group exercise class volunteered to be the peer |

Situating Peer-Based Strategies Within a Broader Conceptual Framework

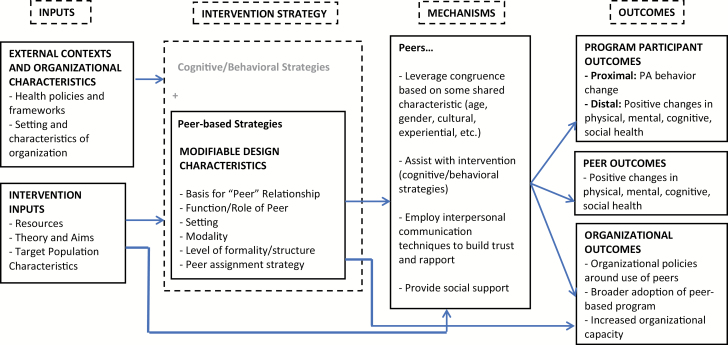

This section presents a conceptual framework for integrating peer-based strategies into PA interventions with older adults that can be used to ground the concepts within broader theoretical contexts (see Figure 2). In this framework, available resources (e.g., funding, program staff, training resources, and materials provided to deliver intervention), theory and aims, and consideration of the target population’s characteristics will shape the PA-promotion intervention strategy chosen, as will various external contexts, including the host organization’s characteristics (e.g., grassroots agency vs large, well-established agency, the type of population typically served by the organization, types of services typically offered) and broader health policies and frameworks (e.g., most recent guidelines for PA put out by leading health organizations). Whether peer-based strategies are being used as the primary intervention strategy or in addition to another cognitive and/or behavioral intervention strategy, the peer-based strategy invoked should have a theoretical basis that justifies the design characteristics chosen and these design characteristics should be explicitly defined and thoroughly described. Modifiable design characteristics of a peer-based intervention strategy include, but are not limited to, the basis for the “peer” relationship with the target group, function/role of peer, setting, modality, employment of a formal or informal structure, and peer assignment strategy.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework for integrating peer-based strategies into physical activity (PA) interventions with older adults.

Potential mechanisms represent the program theory or logic—it explicates why the chosen peer-based strategy and selected design characteristics are hypothesized to have an effect on the targeted outcomes. Figure 2 provides examples of such logic. A peer-based strategy, for example, could be designed to leverage congruence based on some shared characteristic (age, gender, cultural, experiential, etc.), trusting relationship, or power gradient. Peers might assist with the intervention either through helping participants to plan for healthy behavior changes (e.g., design a workout plan), teaching specific skills, role modeling, or enhancing self-efficacy. Or, peers could employ interpersonal communication techniques to build trust and rapport and provide social support (e.g., information, empathy, reinforcement, access to tools and resources), for example. Proximal, intermediate, and distal outcomes, in turn, are affected. These outcomes may be just for the participants, or, depending upon the theory, target population, and chosen design characteristics, outcomes could also be hypothesized to change for the peers as well and for the organization.

Practice Guidelines for Designing, Implemen ting, and Reporting Peer-Based PA Programs

We build off of existing recommendations and frameworks from the literature (e.g., Ginis et al., 2013; Simoni et al., 2011) to propose a series of practice guidelines to guide the design, implementation and reporting of peer-based intervention strategies to support PA interventions for older adults.

-

Develop a theoretical basis to guide the multicomponent intervention strategy, outcomes and target population

First and foremost, developing the theoretical basis of the intervention and why it is expected that the intervention is likely to have an impact on desired outcomes in the target population is crucial. However, this can be challenging when it comes to complex, multicomponent interventions. Very rarely are peer-based PA-promotion strategies implemented in the absence of other cognitive or behavioral change strategies. In other words, peer-based strategies are usually one component of a multicomponent intervention aimed to increase PA. Boston RALI is guided by a conceptual model that recognizes the multiple influences on human behavior that interact in complex ways and applies a unique multicomponent model of behavior change (Lachman, Lipsitz, Lubben, Sceppa, & Jette, 2018). While multicomponent PA interventions have the ability to address the host of challenges facing older adults as they make health behavior changes and have, in many cases, been found to be more effective than single-component interventions (Sallis, Owen, & Fisher, 2008), they tend to be largely atheoretical, as we have argued above and as is pointed out in other literatures (e.g., Pillemer, Suitor, & Wethington, 2003). Further, with multicomponent interventions, it is difficult to determine the precise intervention mechanism(s) (i.e., the “active ingredient”) that bring about effects.

Nevertheless, theory-based intervention development is necessary. As Pillemer and colleagues (2003) point out, “…if an intervention study serves as a test of theoretically derived hypotheses and basic research findings, the results may then be highly useful, regardless of whether the intervention is a success….the absence of effects in a theoretically derived intervention provides a useful opportunity to revise the theory and to inspire new fundamental and applied research” (p. 21).

-

Use a combination of theory, basic research, and practice wisdom to explicitly and intentionally define and report on the design characteristics of the peer component

After the theoretical basis for the intervention is laid out, interventionists and researchers should consider: (i) whether peers are truly a needed component of the intervention in order to achieve target outcomes and (ii) if so, explicitly and intentionally define the design characteristics of the peer component, considering how each design feature might enhance or inhibit the effectiveness of the peer in moving the participant toward desired outcomes. It is unrealistic to suggest that every design decision for the peer-based component be fully theory-based, but instead a combination of theory, basic research, and practice knowledge (e.g., cost-effectiveness or acceptability of peers) might be used to inform the design characteristics of the peer-based component. What is most important is that attention to design characteristics is promoted in the literature, and that reporting on these characteristics become a key part of the dissemination process. This practice will enhance our understanding of “what works, where and why” when it comes to peer-based strategies for promoting PA.

Using the modifiable design characteristics presented in this paper as guidance, we proposes a series of questions that can be considered as part of this design specification process:- What type of peer-based strategy does this design represent? Is the peer delivering the intervention, assisting with the intervention, or a combination of both? Is training necessary? What is the power-differential here? How will this enhance or inhibit the effectiveness of the peer in moving the participant toward desired outcomes? What are the skills and knowledge that peers need to be effective in their role and how will that be provided? Should it be organic (peer driven) or prescribed (e.g., active listening skills, problem solving skills, leadership skills, content knowledge, training regarding working in specified setting or modality)?

- What is the basis for the “peer” relationship in this design? In what ways are the peers similar or different from the program participants? Beyond these shared characteristics, what are the characteristics of the peers (e.g., an exemplar when it comes to later life PA, have experience of transforming from sedentary to active?)? Is this known to program participants? Should inclusion and exclusion criteria be identified for peers (e.g., have to be at a certain level of physical fitness, have certain skills or knowledge?)

- In what type of setting will the peer-based strategy be implemented? How might the setting in which the peer-based strategies is implemented serve to enhance or inhibit the effectiveness of the peer in moving the participant toward desired outcomes? Could it have an influence on the credibility, perceived power differential and garnered trust that is achieved between peers?

- What is the modality through which the peer-based component will be delivered? Will it be one-on-one or one to many? Will it be in-person, by phone, by text, by e-mail or by social media? How does the modality enhance or inhibit the effectiveness of the peer in moving the participant toward desired outcomes?

- Will the peer-based component be informal or formal? Will the activities that the peer is asked to perform be largely informal and unstructured, with peers taking an active role in self-generating content, or more formalized and structured, with the content and approach to be utilized by the peer being fully scripted and prescribed by the researchers or others? How will this enhance or inhibit the effectiveness of the peer in moving the participant toward desired outcomes?

- How will peers be assigned to program participants? Will this process be random, convenience-based, or using a peer-matching strategy based on predefined criteria? How will this enhance or inhibit the effectiveness of the peer in moving the participant toward desired outcomes?

-

Consider how the implementation of the peer-based component will be monitored (i.e., fidelity and quality control) and whether there are additional outcomes that you are interested in measuring

When peer-based strategies are being utilized in research, the peers represent a group of individuals that are strategically incorporated into the study per the design characteristics described above, but one need also consider the fact that peers are likely to play an important role in intervention delivery and that peers could be conceived of as targets of intervention themselves. Further, if we can find ways to measure each of the design characteristics (e.g., assessment of the nature and quality of the peer-participant relationship) and the other features in the conceptual model proposed here, we can begin to answer important implementation questions about which components of the design is important in influencing which outcomes, and through what mechanisms.

Thus, program developers should ask themselves:- What are the standards by which you will assess the quality of intervention delivery (e.g., program satisfaction with peer; quality, content, and duration of interactions with participants, effectiveness of any training of peers on learning outcomes)?

- Are there expected effects of the peer-based component on outcomes other than those of direct interest to the study, such as organizational capacity or on outcomes for the peers themselves? How do you plan to measure these?

- Do you anticipate any unintended consequences of the peer interaction and how do you plan to prevent or address these issues?

Conclusion

Ginis et al.’s (2013) call for “interventionists…to include peer mentors in their intervention delivery models [and for]…[i]nvestigators…to pursue a more comprehensive understanding of factors that can explain and maximize the impact of peer-delivered activity interventions” (p. abstract), emphasizes the need for implementation studies that clearly describe “what works, where and why” when it comes to peer-based strategies for promoting PA. We believe, the proposed typology and conceptual framework, in addition to practical guidelines for more rigorous conceptualization, implementation and reporting of peer-based PA interventions, helps advance not only the PA promotion field, but also the health promotion field more broadly. These ideas could be extended to other arenas of health promotion among older adults, for example, health care utilization, disease management, falls prevention, or healthy eating. However, attention should be paid to whether modifications would be necessary depending on type of health behavior or special population being targeted. In sum, a common terminology and further refinement of peer-based strategies will facilitate appropriate selection and application of relevant behavior change approaches in future work.

Funding

The research was supported by the National Institute on Aging, Boston Roybal Center for Active Lifestyle Interventions, RALI Boston, Grant # P30 AG048785; the Boston College Institute on Aging; and the Institute for Aging Research, Hebrew SeniorLife, National Institute for Nursing Research P20 “NUCare: Northeastern University Center in Support of Self-Management and Health Technology and Resources for Nurse Scientists” Grant # P20 NR015320.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the study participants and peers for their kind and valuable participation.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

References

- Bickmore T. W., Silliman R. A., Nelson K., Cheng D. M., Winter M., Henault L., & Paasche-Orlow M. K (2013). A randomized controlled trial of an automated exercise coach for older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61, 1676–1683. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie D. A., & Inoue A (2005). Motivational interviewing to promote physical activity for people with chronic heart failure. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 50, 518–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03422.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buman M. P., Giacobbi P. R. Jr, Dzierzewski J. M., Aiken Morgan A., McCrae C. S., Roberts B. L., & Marsiske M (2011). Peer volunteers improve long-term maintenance of physical activity with older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 8(Suppl. 2), S257–S266. doi:10.1123/jpah.8.s2.s257 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaneda-Sceppa C., Cloutier G. J., Isaacowitz D. M., & John D (under review). Exercise-induced relationships between physical performance, activity and psychological wellbeing in community-dwelling frail older adults. [Google Scholar]

- Castro C. M., Pruitt L. A., Buman M. P., & King A. C (2011). Physical activity program delivery by professionals versus volunteers: The TEAM randomized trial. Health Psychology, 30, 285–294. doi:10.1037/a0021980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control (2016). More than 1 in 4 us adults over 50 do not engage in regular physical activity, PR Newswire; Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/p0915-physical-activity.html [Google Scholar]

- Chase J. A. (2013). Physical activity interventions among older adults: A literature review. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice, 27, 53–80. doi:10.1891/1541-6577.27.1.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colón-Semenza C., Latham N. K., Quintiliani L. M., & Ellis T (2018). Peer coaching through Mhealth targeting physical activity in people with Parkinson disease: A feasibility study. Journal of Medical Internet Research: Mhealth and Uhealth, 6, e42. doi:10.2196/mhealth.8074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depp C. A., Schkade D. A., Thompson W. K., & Jeste D. V (2010). Age, affective experience, and television use. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 39, 173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorgo S., Robinson K. M., & Bader J (2009). The effectiveness of a peer-mentored older adult fitness program on perceived physical, mental, and social function. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 21, 116–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00393.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginis K. A., Nigg C. R., & Smith A. L (2013). Peer-delivered physical activity interventions: An overlooked opportunity for physical activity promotion. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 3, 434–443. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0215-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J., Smith T. B., & Layton J. B (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med, 27, p.e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard E. P., Louvar K. E, (2017). Evaluating goals of community-dwelling, low-income older adults. Research in Gerontological Nursing 10: 205–214. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20170831-02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keadle S. K., McKinnon R., Graubard B. I., & Troiano R. P (2016). Prevalence and trends in physical activity among older adults in the United States: A comparison across three national surveys. Preventive Medicine, 89, 37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J., Rosenberg D. E., Nathan A., Millstein R. A., Carlson J. A., Crist K., … Marshall S. J (2012). Applying the ecological model of behavior change to a physical activity trial in retirement communities: Description of the study protocol. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 33, 1180–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk M. A., Kelley C., Yankey N., Birken S. A., Abadie B., & Damschroder L (2016). A systematic review of the use of the consolidated framework for implementation research. Implementation Science, 11, 72. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0437-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullgren J. T., Harkins K. A., Bellamy S. L., Gonzales A., Tao Y., Zhu J., … Karlawish J (2014). A mixed-methods randomized controlled trial of financial incentives and peer networks to promote walking among older adults. Health Education & Behavior, 41(1 Suppl), 43S–50S. doi: 10.1177/1090198114540464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman M. E., Lipsitz L., Lubben J., Castaneda-Sceppa C. & Jette A. M (2018). When adults don’t exercise: Behavioral strategies to increase physical activity in sedentary middle-aged and older adults. Innovation in Aging, 2, 1–12. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igy007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layne J. E., Sampson S. E., Mallio C. J., Hibberd P. L., Griffith J. L., Das S. K., … Castaneda-Sceppa C (2008). Successful dissemination of a community-based strength training program for older adults by peer and professional leaders: The people exercising program. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 56, 2323–2329. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02010.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matz-Costa C., Lubben J., Lachman M., Lee H.N., & Choi Y.J (under review). The Engaged4Life Study: A pilot randomized trial of an intervention to enhance the health-promoting effects of older adults’ activity Portfolios. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead S., Hilton D., & Curtis L (2001). Peer support: A theoretical perspective. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 25, 134–141. doi:10.1037/h0095032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly G. A., & Spruijt-Metz D (2013). Current mHealth technologies for physical activity assessment and promotion. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45, 501–507. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K., Jill Suitor J., & Wethington E (2003). Integrating theory, basic research, and intervention: Two case studies from caregiving research. The Gerontologist, 43(Suppl. 1), 19–28. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_1.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto B. M., Goldstein M. G., Ashba J., Sciamanna C. N., & Jette A (2005). Randomized controlled trial of physical activity counseling for older primary care patients. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 29, 247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed S. B., Crespo C. J., Harvey W., & Andersen R. E (2011). social isolation and physical inactivity in older us adults: Results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. European Journal of Sport Science, 11, 347–353. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2010.521585 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis J. F., Owen N., & Fisher E. B (2008). Ecological models of health behavior. In Glanz K., Rimer B., & Viswanath K. (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice (4th ed, pp. 464–85). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Simoni J. M., Franks J. C., Lehavot K., & Yard S. S (2011). Peer interventions to promote health: Conceptual considerations. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81, 351–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01103.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan A. N., & Lachman M. E (2016). Behavior change with fitness technology in sedentary adults: A review of the evidence for increasing physical activity. Frontiers in Public Health, 4, 289. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennstedt S., Howland J., Lachman M., Peterson E., Kasten L., & Jette A (1998). A randomized, controlled trial of a group intervention to reduce fear of falling and associated activity restriction in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53, P384–P392. doi:10.1093/geronb/53B.6.P384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Vijver P.L., Wielens H., Slaets J. P. J., & van Bodegom D (2018). Vitality club: A proof-of-principle of peer coaching for daily physical activity by older adults. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 8, 204–211. doi:10.1093/tbm/ibx035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]