Abstract

Background:

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and preeclampsia both disproportionally affect African American women. Evidence continues to grow linking a history of preeclampsia to future CVD. Therefore, we sought to determine whether abnormalities in cardiac function, as determined by echocardiography, could be identified at the time of preeclampsia diagnosis in African American women, and if they persist into the early postpartum period.

Study design:

This prospective blinded longitudinal cohort study was performed from April 2015 to May 2017. We identified African American women diagnosed with preterm (< 37 weeks) preeclampsia with severe features and compared them to control normotensive pregnant women matched on race, gestational age, maternal age, and body mass index. We obtained transthoracic echocardiograms on cases and controls at time of diagnosis and again 4–12 weeks postpartum. We quantified the systolic function with longitudinal strain, ventricular-arterial coupling parameters and diastolic function.

Results:

There were 29 matched (case-control) pairs of African American women for a total of 58 women. At time of preeclampsia diagnosis, there was more abnormal cardiac function as evidenced by worse cardiac systolic function (longitudinal strain), increased chamber stiffness (end systolic elastance), and worse diastolic function (E/e’) in preeclampsia cases compared to controls. These findings persisted 4–12 weeks postpartum. There were additional notable abnormalities in E/A, and Ea (arterial load) postpartum, indicative of potentially worse diastolic function and increased arterial stiffness in the postpartum period.

Conclusions:

Among African American women, we found notable cardiac function differences between women with severe preeclampsia and healthy pregnant controls that persist postpartum.

Keywords: African American, Cardiac function, Echocardiogram, Preeclampsia, Pregnancy

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death for women in the United States and worldwide [1–6]. CVD disproportionally affects African American women who are at higher risk of coronary artery disease, acute myocardial infarction, and cardiac death compared to age-matched Caucasian women [2,4–7]. The racial disparities in the prevalence of CVD has led the American Heart Association (AHA) to highlight the importance of further research and preventive strategies in the sub-group of African American women, yet most research continues to be done in predominantly Caucasian populations [4,6].

Preeclampsia (PEC) affects up to 8–10% of all pregnancies in the United States and is a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality worldwide [8,9]. Similar to CVD, PEC disproportionally affects African American women [10,11]. Traditionally, since PEC is a pregnancy-specific condition limited to reproductive age women, these women had not traditionally been considered high risk for CVD. Within the last decade, there has been a growing body of epidemiologic evidence that supports a markedly increased risk of CVD in women with a history of PEC, including a 4-fold increased risk of heart failure and a 2-fold increased risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke [12–18]. In support of these findings, the AHA recently added a history of PEC to its list of risk factors for CVD and indicated that PEC is as potent a risk factor for CVD as diabetes or a lifetime of smoking [4].

While women with PEC are known to be at higher risk for CVD, there are insufficient data to identify which women with PEC will develop CVD later in life. Studies in predominantly Caucasian women with PEC provide evidence of subclinical cardiac dysfunction even at the time of diagnosis [19–22]. Subclinical cardiac dysfunction, as measured by echocardiographic measures of left ventricular strain and abnormalities in left ventricular ejection fraction are associated with the subsequent risk of CVD [23–25]. It has also been shown that therapeutic interventions during the asymptomatic phase of cardiovascular impairment can improve overall prognosis [26–29].

Therefore, we sought to evaluate differences in cardiac function, as determined by quantitative echocardiography, in African American women with and without PEC at the time of diagnosis and 4–12 weeks postpartum. Our objective was to identify whether abnormalities in cardiac function, as determined by echocardiography, could be identified as early as the time of PEC diagnosis and if they persist into the early postpartum period. We focused on African American women, as they represent a high-risk and understudied population.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patient selection

This prospective longitudinal cohort study (SCOPE: Study of Cardiovascular Outcomes of Preeclampsia with Echocardiography) was comprised of women with severe preterm preeclampsia compared to normotensive controls. Women (≥18 years) were enrolled in this study from April 2015-May 2017 at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania after obtaining written informed consent. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to initiation of the study.

Our case group included African American women diagnosed with preterm preeclampsia with severe features who were admitted to the Obstetrical unit at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Preterm status was defined by women with a gestational age from 23 weeks to 36 6/7 weeks gestation. Preeclampsia with severe features was defined by current guidelines from the Hypertension Task Force of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [9]. Cases with a pre-existing diagnosis of hypertension were included if they developed preeclampsia super-imposed on the chronic hypertension.

Normotensive African American pregnant controls were recruited in the outpatient setting. Each individual control was matched to a case by gestational age of preeclampsia diagnosis (± 3 weeks), maternal age (± 8 years), and body mass index (± 5 kg/m2). All women were followed prospectively from the time of enrollment into the postpartum period for up to 12 weeks. Women who developed any form of pregnancy related hypertension were subsequently excluded post enrollment from the control group. Women with preexisting cardiovascular disease, chronic hypertension or multiple gestations were excluded.

The first echocardiogram was performed at the time of diagnosis of preeclampsia for the cases and at a similar gestational age (± 3 weeks) for the matched outpatient controls, which was considered visit 1 or baseline. A second echocardiogram and blood draw was performed 4–12 weeks postpartum; this was denoted as visit 2.

2.2. Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiograms were performed and quantitated at the University of Pennsylvania Center for Quantitative Echocardiography. Two-dimensional and Doppler images were acquired using GE Vivid E9 and E95 platforms (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) in the parasternal long and short-axis views and apical views with 2D images at 60–80 frames/second and digitally archived at the acquisition frame rate. Quantitation of left ventricle (LV) volumes, diastolic function parameters, and strain measures [30] were performed using Tomtec Imaging Systems 2D Cardiac Performance Analysis (Unterschleissheim, Germany) by sonographers blinded to clinical status of the patient.

LV end-diastolic volume (EDV) and end-systolic volume (ESV) was calculated using the Simpson’s method of discs as recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography. LVEF was derived as the difference between EDV and ESV divided by the EDV. Diastolic function parameters including mitral inflow velocities (E/A) and tissue Doppler indices of the LV lateral and septal (e’, a’) were quantified. Longitudinal and circumferential peak systolic strain was quantified in a semi-automated method on digitally archived images in the apical 4 chamber and 2 chamber (longitudinal strain) and short axis views at the midpapillary level (circumferential strain). Peak strain was computed automatically and averaged across all segments [31]. Moreover, additional measures of cardiovascular function including end systolic elastance (Ees), effective arterial elastance (Ea), and the ratio Ea/Ees, indicative of ventricular-arterial coupling were determined using modified single-beat algorithm as previously described [32]. Ea was derived from the end-systolic pressure (ESP)/Stroke Volume, where ESP was estimated as 0.90 × systolic pressure measured by manual blood pressure cuff measurement at the time of the echocardiogram.

2.3. Statistical methods

Demographic factors were compared between cases and controls using Pearson chi-square, Fisher exact, and t-tests were used as appropriate. Wilcoxon Ranksum methods were used to test group differences for gestational age at delivery and weeks post-partum at time of echocardiogram.

Echocardiographic parameters, blood pressure, and heart rate at each time point (visit 1 and visit 2) were compared between cases and controls using a random effects linear model for each matched pair. This extension of a paired t-test allows for adjustment for potential confounding factors. For each visit, baseline measures of ejection fraction, longitudinal and circumferential strain, E/E’ average and E/A were adjusted for systolic BP to control for differences in load dependency in echocardiographic parameters between case-control pairs. Post-partum assessments and change from baseline for these measures were also adjusted for number of weeks post-partum as time of follow-up may differ between case-control pairs. Additional analyses were performed excluding case-control sets where the case had reported chronic hypertension prior to pregnancy (n = 11).

Statistical significance was set at the 0.05 level. P-values were not adjusted for multiplicity. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 14.2 (College Station, TX).

3. Results

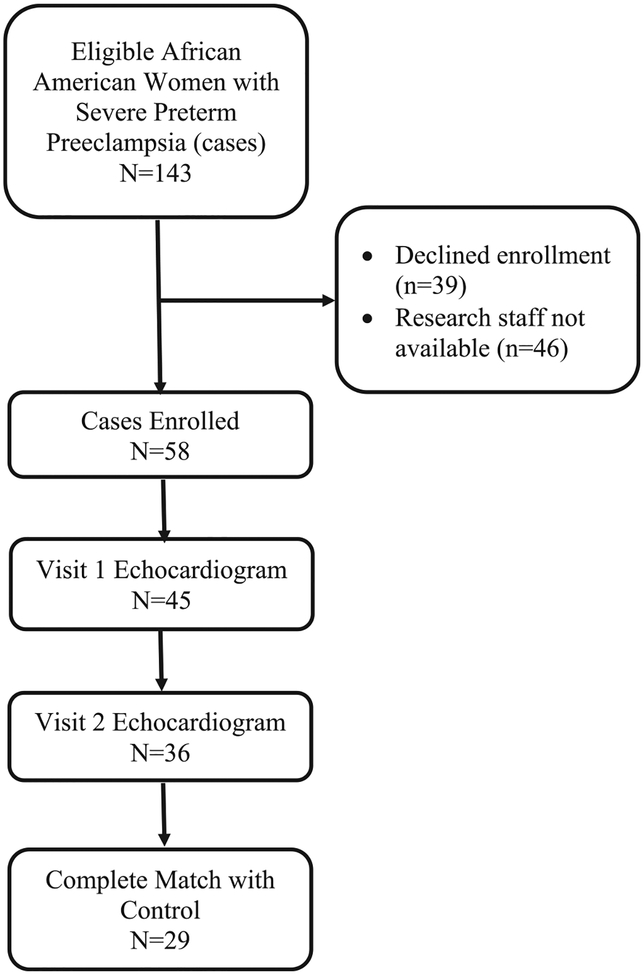

Fig. 1 shows the flow diagram of women included in the analysis. There were 29 matched sets of African American women cases and controls (58 women total). Table 1 displays the demographic information for the cohort. The cases were more likely to be older compared to the controls (case-control matching was ± 8 years). There were 11 cases with chronic hypertension and 9 cases with gestational or pre-gestational diabetes and none in the controls. Consistent with the management of severe preterm preeclampsia, the cases were delivered at an earlier gestational age than controls.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of women included in the analysis.

Table 1.

Demographic Information.

| Cases (N = 29) | Controls (N = 29) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 30.7 (7.32) | 27.8 (5.53) | 0.0005 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2)a | 33.9 (6.59) | 33.4 (5.85) | 0.353 |

| Nulliparityb | 18 (62) | 12 (41) | 0.115 |

| History of Smokingb | 2 (7) | 2 (7) | 1 |

| Diabetesb | |||

| Gestational | 2 (7) | 0 | 0.003 |

| Pre-gestational | 7 (24) | 0 | |

| Chronic Hypertensionb | 11 (38) | 0 | 0.001 |

| Gestational age at Baseline (weeks)a | 31.3 (3.90) | 31.7 (3.61) | 0.345 |

| Gestational age at Delivery (weeks)c | 33 (32–35) | 39 (38–39) | < 0.0001 |

| Time of postpartum echocardiogram (weeks)c | 6 (5–6) | 7 (6–9) | 0.005 |

Mean (± Standard Deviation).

Number (Percent).

Median (Interquartile range).

3.1. Echocardiographic changes

Table 2 displays the estimated adjusted regression coefficients and compares the changes in echocardiographic parameters between cases and controls at baseline (visit 1) and postpartum (visit 2). At baseline (visit 1), cases appeared to have globally preserved LVEF. However, cases had evidence of worse systolic cardiac function, as assessed by longitudinal strain; increased chamber stiffness, as assessed by Ees; and worse diastolic function, as assessed by E/e’ compared to controls.

Table 2.

Comparison of Echocardiograms for Cases and Controls at Baseline and Postpartum.

| Baseline echocardiogram (visit 1) | Postpartum echocardiograms (visit 2) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases N = 29 | Controls N = 29 | Coefficient a[95% Confidence Interval] | p-value | Cases N = 29 | Controls N = 29 | Coefficient a[95% Confidence Interval] | p-value | |

| Systolic function | ||||||||

| Ejection Fraction | 55.8 (50.4–58.1) | 50.8 (48.3–53.8) | 4.0 [0.4–8] | 0.028b | 50.2 (43.3–54.1) | 50.9 (46.5–54.8) | −0.9 [−4.6 to 2.8] | 0.6c |

| Longitudinal strain | −12.94 (−15.22 to −10.66) | −15.06 (−17.15 to −12.97) | 2.22 [0.95–3.49] | 0.001b | −13.11 (−15.54 to −10.76) | −15.15 (−17.63 to −12.62) | 1.45 [0.063–2.84] | 0.04c |

| Circum-ferential strain | −24.69 (−30.73 to −18.65) | −22.54 (−26.19 to −18.89) | −2.40 [−5.36 to 0.57] | 0.11b | −20.95 (−25.10 to −16.84) | −22.97 (−26.65 to −19.29) | 1.10 [−1.29 to 3.49] | 0.4c |

| Ees | 2.23 (1.44–3.02) | 1.76 (1.34–2.18) | 0.47 [0.16–0.78] | 0.003 | 1.91 (1.45–2.37) | 1.64 (1.30–2.98) | 0.27 [0.04–0.50] | 0.02 |

| Diastolic function | ||||||||

| E/E’ average | 8.78 (6.54–11.02) | 7.58 (5.72–41) | 1.34 [0.041–2.63] | 0.04b | 9.32 (6.30–12.34) | 8.00 (5.52–10.79) | 1.56 [−0.11 to 3.22] | 0.07c |

| E/A | 1.31 (0.79–1.83) | 1.60 (1.19–2.01) | −0.24 [−0.59 to 0.10] | 0.2b | 1.45 (1.13–1.77) | 1.80 (1.29–2.31) | −0.37 [−0.64 to −0.11] | 0.006c |

| Ventricular-arterial coupling | ||||||||

| Ea | 1.95 (1.42–2.48) | 1.83 (1.48–2.17) | 0.11 [−0.12 to 0.33] | 0.4 | 2.16 (1.74–2.58) | 1.81 (1.45–2.07) | 0.41 [0.19–0.63] | 0.001 |

| Ea/Ees | 0.86 (0.68–1.16) | 1.01 (0.91–1.17) | −0.12 [−0.29 to 0.06] | 0.2 | 1.15 (0.96–1.29) | 1.15 (0.92–1.24) | 0.09 [−0.04 to 0.22] | 0.19 |

| Maternal vital signs at time of echocardiogram | ||||||||

| Systolic Blood Pressure | 142.1 (123.2–161.1) | 119.4 (110.2–128.6) | < 0.001 | 137.8 (117.2–158.3) | 120.9 (113.2–128.6) | < 0.001 | ||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | 82.4 (68.9–95.9) | 70.7 (62.4–79.0) | 0.006 | 84.9 (73.0–96.8) | 71.6 (65.6–77.6) | < 0.001 | ||

| Heart rate | 85.6 (75.4–95.9) | 86.1 (76.1–96.1) | 0.9 | 75.3 (63.2–87.4) | 68.6 (55.4–81.8) | 0.06 | ||

Data are presented as medians (inter-quartile range).

Longitudinal strain: A measure of systolic function with less negative numbers correlating to worse function.

Ees: End systolic elastance (chamber stiffness) – higher number more abnormal.

E/e’: higher number more abnormal.

E/A: lower number more abnormal.

Ea: Arterial load – higher number more abnormal.

Ea/Ees: ventricular-vascular coupling.

Coefficient: The difference between case and control (case minus control).

Measures of association are adjusted for blood pressure.

Measures of association are adjusted for blood pressure and number of weeks postpartum.

At the postpartum visit, there were similar findings of worse longitudinal strain and increased chamber stiffness (Ees) for cases compared to controls. There were additional notable abnormalities in E/A, and Ea postpartum, indicative of potentially worse diastolic function (E/A) and increased arterial stiffness (Ea). There were no differences in circumferential strain or ventricular/vascular coupling (Ea/Ees) at baseline or postpartum. In sensitivity analyses, we excluded women with chronic hypertension (and their matched controls) and results were unchanged (see Supplemental table).

4. Discussion

In this prospective blinded longitudinal cohort study comprised of African American women with severe preterm preeclampsia, we found notable differences in both systolic and diastolic measures of cardiac function between women with severe preeclampsia and healthy controls at the time of diagnosis. Moreover, these aberrant changes persisted six weeks postpartum. Our findings are of clinically important since subclinical cardiac dysfunction has been associated with future risk of CVD [23–25] and therapeutic interventions during the asymptomatic phase of CV impairment can improve overall prognosis [26–29]. Therefore, these changes may identify women who should be followed more closely for the development of interval CVD.

Abnormal cardiac findings have been noted previously on echocardiography in women with preeclampsia including systolic measures of function such as longitudinal strain and ventricular mass [19–21,33–36]. Our study found similar findings in our cohort of African American women, a traditionally understudied group that is at higher risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease. The magnitude of dysfunction in our population of African American women appears to be slightly more than those in predominantly Caucasian populations, potentially highlighting the known racial cardiovascular differences. Abnormalities in strain precede changes in ejection fraction and may be used to identify subclinical systolic dysfunction prior to overt cardiomyopathy development [24,31,37–39]. Our findings of increased chamber stiffness (Ees), worse systolic function (longitudinal strain); and worse diastolic function (E/e’) are suggestive of abnormalities seen in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) [40]. Thus our data are consistent with the notion that PEC may cause persistent damage to cardiac function, which manifests similarly to echocardiographic findings observed with HFpEF. We do also recognize that pregnancy itself is a condition associated with increased cardiac stress, so it may not be surprising that the population of African American controls have borderline normal left ventricular eject fraction at baseline.

Prior studies evaluating preeclampsia and echocardiographic findings only had a small representation of African American women. Therefore, our focus on African American women is a critical strength of our study given the known worse outcomes of both preeclampsia and cardiac disease in this group of women. An additional strength of our study is that we prospectively identified women and followed them through the pregnancy and into the postpartum period. Furthermore, all of the quantitative analyses were performed by personnel blinded to the case-control status. Our study is limited by sample size, which may have affected our ability to detect additional significant findings. Furthermore, our follow-up time was that of 6 weeks postpartum, and therefore we do not know if these abnormalities persist beyond the immediate postpartum time period and if they will be associated with cardiovascular outcomes long-term. Lastly, while our cases included women with chronic hypertension whereas the controls did not, the differences in our results remained significant even when limiting the analyses to women without hypertension at baseline.

5. Conclusion

Our findings further support the recent consensus statement from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and AHA that highlights the critical importance of collaborations between Obstetricians Gynecologists and Cardiologists to improve the cardiovascular health of women [41]. Identifying early echocardiographic changes, even if women are asymptomatic, is a key step in providing opportunities for risk stratification and early intervention to decrease the associated risk of long-term cardiovascular disease in this high-risk group of women with a history of preeclampsia. Given that our findings suggest echocardiographic abnormalities are present early in the postpartum period, it is reasonable to consider performing screening echocardiograms on women thought to be at highest risk. In addition to risk stratification, detecting early markers of cardiac dysfunction will likely aid in understanding the pathogenesis by which preeclampsia exposure leads to cardiovascular disease. Future studies will aim to follow women prospectively and determine the association with our findings and overt CVD.

Supplementary Material

Sources of funding

This research was supported by the following funds: Women’s Reproductive Health Research Award: K12-HD001265–15; Penn Presbyterian Harrison Fund and the McCabe Fund pilot grant award.

Footnotes

Presentations

This was an oral presentation at the Annual Meeting for the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine in Las Vegas in January 2017.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preghy.2019.05.021.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].http://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fs_women_heart.htm. Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Women and Heart Disease. Accessed 3/1/2017.

- [2].Foundation WsH. Women and Heart Disease. http://www.womensheart.org/content/heartdisease/heart_disease_facts.asp.

- [3].Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. , Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report from the american heart association, Circulation 133 (4) (2016) 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, et al. , Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women–2011 update: a guideline from the american heart association, Circulation 123 (11) (2011) 1243–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Erqou S, Kip KE, Mulukutla SR, Aiyer AN, Reis SE, Endothelial dysfunction and racial disparities in mortality and adverse cardiovascular disease outcomes, Clin. Cardiol 30 (10) (2016) 22534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mehta LS, Beckie TM, DeVon HA, et al. , Acute myocardial infarction in women: a scientific statement from the american heart association, Circulation 133 (9) (2016) 916–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. , Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: a report from the american heart association, Circulation 135 (10) (2017) e146–e603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sibai B, Dekker G, Kupferminc M, Pre-eclampsia, Lancet. 365 (9461) (2005) 785–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hypertension in pregnancy, Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task force on hypertension in pregnancy, Obstet. Gynecol 122 (5) (2013) 1122–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Breathett K, Muhlestein D, Foraker R, Gulati M, Differences in preeclampsia rates between African American and Caucasian women: trends from the National Hospital Discharge Survey, J. Womens Health 23 (11) (2014) 886–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Shahul S, Tung A, Minhaj M, et al. , Racial disparities in comorbidities, complications, and maternal and fetal outcomes in women with preeclampsia/eclampsia, Hypertens Pregnancy 34 (4) (2015) 506–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ, Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis, BMJ 335 (7627) (2007) 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].McDonald SD, Malinowski A, Zhou Q, Yusuf S, Devereaux PJ, Cardiovascular sequelae of preeclampsia/eclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analyses, Am. Heart J. 156 (5) (2008) 918–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lin YS, Tang CH, Yang CY, et al. , Effect of pre-eclampsia-eclampsia on major cardiovascular events among peripartum women in Taiwan, Am. J. Cardiol 107 (2) (2011) 325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Funai EF, Friedlander Y, Paltiel O, et al. , Long-term mortality after preeclampsia, Epidemiology 16 (2) (2005) 206–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kestenbaum B, Seliger SL, Easterling TR, et al. , Cardiovascular and thromboembolic events following hypertensive pregnancy, Am. J. Kidney Dis. 42 (5) (2003) 982–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Behrens I, Basit S, Lykke JA, et al. , Association between hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and later risk of cardiomyopathy, JAMA 315 (10) (2016) 1026–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wu P, Haththotuwa R, Kwok CS, et al. , Preeclampsia and future cardiovascular health: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 10 (2) (2017) 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Melchiorre K, Sutherland GR, Liberati M, Thilaganathan B, Preeclampsia is associated with persistent postpartum cardiovascular impairment, Hypertension 58 (4) (2011) 709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Melchiorre K, Sutherland GR, Watt-Coote I, Liberati M, Thilaganathan B, Severe myocardial impairment and chamber dysfunction in preterm preeclampsia, Hypertens Pregnancy 31 (4) (2012) 454–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shahul S, Rhee J, Hacker MR, et al. , Subclinical left ventricular dysfunction in preeclamptic women with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: a 2D speckle-tracking imaging study, Circ. Cardiovasc. Imag 5 (6) (2012) 734–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Patten IS, Rana S, Shahul S, et al. , Cardiac angiogenic imbalance leads to peripartum cardiomyopathy, Nature 485 (7398) (2012) 333–338 310.1038/nature11040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Tsao CW, Lyass A, Larson MG, et al. , Prognosis of adults with borderline left ventricular ejection fraction, JACC Heart Fail. 4 (6) (2016) 502–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kalam K, Otahal P, Marwick TH, Prognostic implications of global LV dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of global longitudinal strain and ejection fraction, Heart 100 (21) (2014) 1673–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Thavendiranathan Paaladinesh, Poulin Frédéric, Lim Ki-Dong, Juan Carlos Plana Anna Woo, Marwick Thomas H., Use of myocardial strain imaging by echocardiography for the early detection of cardiotoxicity in patients during and after cancer chemotherapy, J. Am. College Cardiol 63 (25) (2014) 2751–2768, 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jessup M, Abraham WT, Casey DE, et al. , 2009 focused update: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation, Circulation 119 (14) (2009) 1977–2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ammar KA, Jacobsen SJ, Mahoney DW, et al. , Prevalence and prognostic significance of heart failure stages: application of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association heart failure staging criteria in the community, Circulation 115 (12) (2007) 1563–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kuznetsova T, Herbots L, Jin Y, Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Staessen JA, Systolic and diastolic left ventricular dysfunction: from risk factors to overt heart failure, Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther 8 (2) (2010) 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Greenland P, Alpert JS, Beller GA, et al. , 2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, Circulation 122 (25) (2010) 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. , Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging, J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr 28 (1) (2015) 1–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Narayan HK, French B, Khan AM, et al. , Noninvasive measures of ventricular-arterial coupling and circumferential strain predict cancer therapeutics-related cardiac dysfunction, JACC Cardiovasc. Imag 13 (16) (2016) 30035 30033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Narayan HK, Finkelman B, French B, et al. , Detailed echocardiographic phenotyping in breast cancer patients: associations with ejection fraction decline, recovery, and heart failure symptoms over 3 years of follow-up, Circulation 135 (15) (2017) 1397–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Rafik Hamad R, Larsson A, Pernow J, Bremme K, Eriksson MJ, Assessment of left ventricular structure and function in preeclampsia by echocardiography and cardiovascular biomarkers, J. Hypertens 27 (11) (2009) 2257–2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Vaught AJ, Kovell LC, Szymanski LM, et al. , Acute cardiac effects of severe preeclampsia, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 72 (1) (2018) 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Shahul S, Medvedofsky D, Wenger JB, et al. , Circulating antiangiogenic factors and myocardial dysfunction in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, Hypertension 67 (6) (2016) 1273–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Shahul S, Ramadan H, Nizamuddin J, et al. , Activin A and late postpartum cardiac dysfunction among women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, Hypertension 72 (1) (2018) 188–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hare JL, Brown JK, Leano R, Jenkins C, Woodward N, Marwick TH, Use of myocardial deformation imaging to detect preclinical myocardial dysfunction before conventional measures in patients undergoing breast cancer treatment with trastuzumab, Am. Heart J 158 (2) (2009) 294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Smiseth OA, Torp H, Opdahl A, Haugaa KH, Urheim S, Myocardial strain imaging: how useful is it in clinical decision making? Eur. Heart J 37 (15) (2016) 1196–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zhang KW, French B, May Khan A, et al. , Strain improves risk prediction beyond ejection fraction in chronic systolic heart failure, J. Am. Heart Assoc 3 (1) (2014) 000550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Borlaug BA, Lam CS, Roger VL, Rodeheffer RJ, Redfield MM, Contractility and ventricular systolic stiffening in hypertensive heart disease insights into the pathogenesis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 54 (5) (2009) 410–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Brown HL, Warner JJ, Gianos E, et al. , Promoting risk identification and reduction of cardiovascular disease in women through collaboration with obstetricians and gynecologists: a presidential advisory from the american heart association and the American college of obstetricians and gynecologists, Circulation 137 (24) (2018) e843–e852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.