Abstract

Adults age 65 and older have high rates of suicide, despite recent efforts to reduce the suicide rate in this population. One suicide prevention strategy with burgeoning empirical support is safety planning; however, there is a lack of information and resources on safety planning for older adults to support uptake of this evidence based practice in clinical settings where older adults are commonly seen. Safety plans can address risk factors for suicide in older adults, including social isolation, physical illness, functional limitations, and use of highly lethal means. Safety plans also promote relevant protective factors, including increasing use of coping strategies, social support, and help-seeking. Clinicians may encounter challenges and barriers to safety planning with older adults. This paper describes a collaborative, creative approach to safety planning that is relevant and useful for this vulnerable population. Using two case examples, we illustrate how to engage older adults in safety planning, including ways to minimize barriers associated with the aging process.

Keywords: Suicide, Safety Planning, Older Adults, Mental Health

Suicide rates increase with age in most countries around the world. In 2015, men age 75 and older died by suicide at a rate of 38.68 per 100,000 compared to the overall population age-adjusted rate of 13.26 (CDC, 2017). Projections indicate subsequent cohorts of older adults will usher in even higher rates (Phillips, 2014), underscoring the importance of late-life suicide prevention. Safety planning is a brief intervention for promoting safety during times of heightened suicide risk. Safety plans include a list of concrete warning signs for a suicidal crisis, coping strategies, social supports, professionals’ contact information for use during crisis, and plans for means safety (Stanley & Brown, 2012). Safety planning is associated with fewer suicide attempts (Bryan et al., 2017; Stanley et al., 2018), faster resolution of suicidal crises (Bryan et al., 2017), fewer hospitalizations (Gamarra, Luciano, Gradus, & Wiltsey Stirman, 2015), and increased engagement in outpatient mental health services (Stanley et al., 2018). Safety planning has high acceptability with patients (Stanley et al., 2016). However, collaboration with clinicians is essential (Kayman, Goldstein, Dixon, & Goodman, 2015), and there is little guidance for clinicians on how to implement safety planning with older adults in a way that targets risk and protective factors unique to this age group. Using two case examples, this paper describes strategies to tailor safety planning for older adults.

We suggest a framework targeting the “Five Ds” of late-life suicide (Conwell, Van Orden, & Caine, 2011): Depression, functional impairment (Disability), physical illness and pain (Disease), social isolation (Disconnectedness), and access to lethal (Deadly) means. Addressing these factors as well as age-associated barriers (e.g., cognitive/functional/sensory impairment), represent strategies for safety planning with older patients. Table 1 presents coping skills that directly target the Five D’s and can be incorporated into the six steps of safety planning as outlined by Stanley and Brown (2008).

Table 1.

Coping Skills to Target Risk Factors for Late-Life Suicide During a Crisis

| Depression symptoms | Disability & Dependence |

Disease | Disconnectedness | Deadly Means |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anhedonia more common than sadness: pleasant activities, exercise, helping others, prayer/religious readings | Talk back to thoughts about being a burden (these thoughts are associated with suicidal behavior) | Take medications as prescribed; attend to physical illness to increase mastery; list primary care doctor’s number | Loneliness: reach out to friends/family, call support hotline, attend social groups, online support groups, plan for future social activities, write letters, help others, volunteer | Firearm safety: store unloaded firearms in a locked cabinet, separately from ammunition; use a gun lock |

| Irritability: exercise, soothe with 5 senses (music, tea, pets), relaxation exercises | Help/support others (in a way that is safe) to counter burden thoughts | Refocus attention on reasons for living and meaning. | Grief: journaling, looking at photographs, writing a letter to loved one; containment exercises if grief is too intense | Enlist family in helping with safe storage of medications |

| Apathy: enlist family to schedule & start pleasant events | Practice meditation & acceptance exercises to tolerate distress | Coping skills for stressors involving lack of control: Relaxation & other pain management strategies | List resources for transportation assistance on plan | Planned check-ins with family, neighbors, providers |

| Insomnia: Sleep hygiene | Activities that promote feelings of dignity | List helpful thoughts to cope with hopelessness about illness (especially new diagnoses) | Go to common areas (if in senior housing), listen to the radio or music, distract with mentally engaging activities (e.g., puzzles) | Remove alcohol from home during crises |

Case 1 – Mr. V.: A Proud Veteran

Mr. V. was a 73-year-old, white, male Veteran who lived alone after his wife of 49 years died 8-months prior. He was honorably discharged from the military after serving in Vietnam. He was proud of his long career as a state trooper and kept two firearms at home. He was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit for suicide ideation with plan. At his intake session with an outpatient therapist after discharge from the unit, Mr. V. denied feeling depressed; he spoke mostly about difficulties sleeping. He reported worsening vision over the last year, difficulty walking due to diabetic neuropathy, and poor appetite. He reported feeling “lost” since his wife’s passing. He was concerned that he would not be able to live independently and feared becoming a burden on his son. Two days prior to admission, his son broached the topic of whether his father should stop driving and move in with him for help with transportation and management of health problems. The afternoon of the admission, he watched a news report that highlighted demands of caring for an aging parent. He began thinking his son would be better off if he were gone and felt certain he would soon become an emotional and financial burden. He removed a firearm from the locked safe, loaded it, and held it. After a few minutes, he put the firearm down and called his neighbor, a friend and fellow Vietnam Veteran, who called Mr. V.’s son.

Formulation and approach.

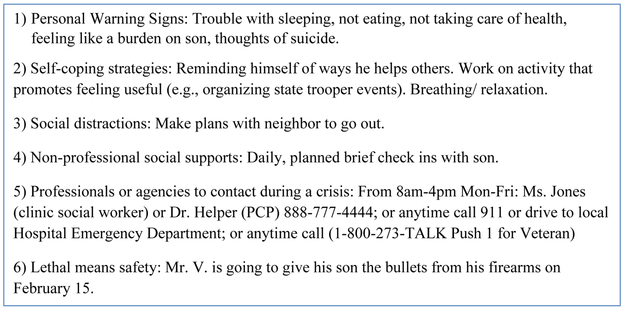

Mr. V.’s therapist expressed appreciation for his openness and provided rationale for safety planning. Mr. V. and his therapist collaboratively completed a safety plan over four sessions (Figure 1). The process was extended because Mr. V. was initially adamant that he would not discuss firearms; thus, his therapist used strategies from motivational interviewing over several sessions to help Mr. V. develop motivation to engage fully in the process.

Figure 1.

Safety Plan for Mr. V.

Mr. V. illustrates the 5 D’s with denial of depressed mood, combined with behaviors consistent with anhedonia (feeling “lost”), as well as sleep and appetite disturbances—a common presentation for depression in later life. Mr. V. had several chronic health problems (disease) as well as associated disability, which manifested in beliefs that his son would be better off if he were gone – a belief that is associated with suicide risk in older adults (Conwell, Van Orden, & Caine, 2011). Mr. V. voiced disconnectedness and missing his wife.

Mr. V.’s willingness to reach out for help is a strength that cannot be over-emphasized. Many older adults with Mr. V.’s profile die by suicide on a first attempt. Helping Mr. V. conceptualize reaching out as a sign of courage and strength was essential, as well as reframing concerns about being a burden, to promote willingness to utilize social supports in the safety plan. The therapist reframed Mr. V.’s reluctance to engage in lethal means safety as a manifestation of his pride in his career as a state trooper; doing so allowed the therapist to identify ways to help Mr. V. retain his sense of pride while also reducing access to firearms during crises. The therapist took care to remind Mr. V. of his autonomy and that safety planning was a collaborative effort.

Outcome.

Once Mr. V. realized his therapist was not going to lock up his firearms without his permission, he was willing to discuss strategies. He agreed his son could keep his bullets until his risk for suicide had lowered. In session 1, Mr. V. listed personal warning signs and discussed how to seek professional help in a crisis (steps 1 and 5 on the written safety plan). In the second session, Mr. V. identified coping strategies; his therapist taught him a relaxation activity to practice on his own; and they discussed involving his son via phone check-ins and firearm safety. In session 3, Mr. V. discussed concerns about being a burden and developed strategies for involving others in his safety plan that would make him less of a burden (e.g., planned check-ins with his son would reduce his son’s anxiety about his father’s safety). In the fourth session, Mr. V. developed a concrete plan for lethal means safety that was acceptable to him.

Case 2 – Mrs. T.: Overwhelmed

Mrs. T. was a 68-year-old woman who had a stroke one year ago, as well as end stage renal disease; she completed dialysis 3 times per week. She lived with her husband in an apartment complex for low-income seniors. Before the stroke, Mrs. T. attended church every Sunday and usually left the apartment to run errands or visit her sister on days she did not receive dialysis. After the stroke, she developed significant weakness on her left side and needed a wheelchair. She also developed short-term memory impairment and spent most of her time watching TV, rarely leaving home except for medical appointments. She needed increased assistance with bathing and dressing as well as prompting to take medications. Her husband had became overwhelmed caring for Mrs. T. He believed his wife’s motivation was decreasing and thought she was depressed, which he reported to her primary care provider (PCP). The PCP asked the primary care clinical social worker to meet with the couple while they were in the clinic to conduct a depression screening.

Formulation and approach.

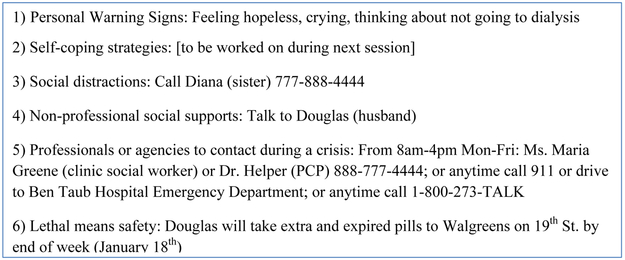

The social worker asked Mrs. T. if she had thoughts of wanting to die or of hurting herself. Mrs. T. became tearful and said that she was considering stopping dialysis because “it was pointless.” She also thought about taking prescription medication to end her life but had not made specific plans to do so. The social worker helped Mrs. T. complete a safety plan over two sessions (see Figure 2) and took follow-up actions (described below) in between sessions.

Figure 2.

Safety Plan for Mrs. T.

Mrs. T. represents a complex but common combination of chronic illness, cognitive impairment, and late life social circumstances. Mrs. T. had been coping adequately with kidney disease until her stroke (disease). The social worker’s analysis was that Mrs. T. had the right to stop treatment, but that her thought of discontinuing dialysis was a reaction to the overall hopelessness she felt (symptoms of depression), rather than drawbacks of dialysis. Because she found it harder to plan her day and remember the things she wanted to do (disability), she spent most of her time on an easy but unrewarding activity – watching TV alone. Her meaning in life had eroded with limited spiritual and family interaction (disconnection).

Mrs. T. had several strengths relevant to safety planning, including a supportive and involved spouse, previous good coping, and willingness to disclose and discuss thoughts about suicide. In addition, collaboration between her PCP and social worker facilitated a timely assessment. The social worker made the PCP aware of changes in Mrs. T.’s mood and behavior, ensuring that medical treatment was geared towards maximizing physical functioning. Because Mrs. T. experienced cognitive decline after the stroke, the social worker simplified the rationale for safety planning (“a plan for what to do when you feel really down”) and involved her husband, with Mrs. T.’s consent. The social worker’s goal with safety planning was creating a tool to prompt Mrs. T. to engage in meaningful, distracting activities and to reduce isolation. During the initial meeting, they focused on social supports and means safety. It was very important that the plan be written on a card Mrs. T. could carry with her. If she didn’t remember the plan, her husband could gently remind her.

Outcome.

The social worker listened for thoughts associated with Mrs. T. wanting to stop dialysis or use pills to end her life and listed these as personal warning signs. They agreed she would call her sister when she felt hopeless and that it was okay for her husband to encourage her to call. The social worker invited Mrs. T. to call her office if she had thoughts of suicide or did not go to dialysis appointments, and for her husband to bring her to the emergency room or call 911 if she started to make a plan for taking pills. Mrs. T.’s husband agreed to collect expired and unneeded medications and take them to a pharmacy for disposal. The PCP placed a consult for Mrs. T. to receive occupational therapy in addition to twice-per-week in-home care. The social worker scheduled a follow-up visit for next week. She planned to explore how Mrs. T. could use her spirituality to cope (e.g., listening to Christian radio, reading a simple devotional) and add these coping strategies to the safety plan.

Discussion

Risk and protective factors common among older adults at risk for suicide should be used to tailor safety plans to older adults’ strengths and needs. These factors can be easily recalled as the ‘5 D’s.’ The clinicians working with Mr. V. and Mrs. T. both addressed symptoms of depression that were most tightly linked to the patients’ risk for suicide—relaxation for insomnia (Mr. V.) and distraction for hopelessness (Mrs. T.). Physical illness was identified as warning signs for both patients and identified as a target for future therapy, but was not directly addressed with the safety plan given its focus on short term coping strategies. Coping skills to tolerate distress from functional impairment were used for both patients—selecting activities to counter perceptions of burden (Mr. V) and distraction techniques to promote calm and comfort (Mrs. T). Other strategies can be identified by having clients brainstorm ways to actively contribute to valued relationships when feeling like a burden (e.g., volunteering, calling a grandchild to support him/her, sending cards or letters) or reflect on times he/she has actively supported others (e.g., “remind myself how I contribute”).

When time allows, clinicians can incorporate brief skill building exercises and psychoeducation into the safety planning process, including mindful breathing, guided imagery, or progressive muscle relaxation. Clinicians can provide audio recordings for additional guidance. Listening to these tapes or using written instructions for practice can be listed on safety plans.

Social isolation and loneliness can be addressed with senior centers, senior living community activities, peer companionship programs, aging services care management, and volunteering opportunities. These strategies have the added benefit of also addressing anhedonia. When patients have supports, such as Mr. V.’s neighbor and son and Mrs. T.’s husband, these can be capitalized on and included in safety plans. For older adults without supports, professional contacts can be sufficient in the short term, with building social supports as a longer-term therapy goal. For caregivers, resources of the local Alzheimer’s Association, including respite and support groups, can address isolation. For older adults coping with bereavement, support groups can be helpful. In times of distress, older adults can reach out to people they met through such activities, receive verbal support, join an activity that might be happening that day, or make plans to engage in a social activity, all of which may reduce painful feelings of isolation and loneliness.

Clinicians should also address sensory impairment that could hamper the safety planning process (e.g., vision/hearing) and employ frequent repetition and memory aids to address age-related cognitive changes and cognitive impairment (when present). Safety planning with older adults will frequently include family members and may involve other providers to address sensory/functional/cognitive impairments, such as including Mrs. T.’s husband to help her remember to use her plan.

Approximately 71% of older adults who die by suicide use firearms (CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control). The presence of a firearm in the home is associated with risk for suicide in later life and suicide attempts are more often fatal among older adults (Conwell, Van Orden, & Caine, 2011). Thus, addressing means safety—including firearms when relevant—is critical. Strategies from motivational interviewing may be useful if patients are reluctant to address the sensitive issue of firearm possession. Resources are available to assist clinicians with these conversations (Harvard Injury Control Research Center, 2019; Pinholt, Mitchell, Butler, & Kumar, 2014).

While safety planning may be conducted over several sessions with patients of any age, an extended approach may be especially useful with older patients who may benefit from repetition and moving through the process more slowly. . For a client whose risk can be managed as an outpatient, identifying a few key supports and emergency numbers, as well as devising a plan for means safety, is often a reasonable goal for a first session. At the same time, appropriate actions must be taken at each session to manage risk, using safety planning as one tool, and will necessarily vary with the client’s presentation.),.

Finally, tailoring safety planning to older adults should also draw upon strengths that older adults bring to the process, such as self-awareness, wisdom, and resiliency.

Clinical Implications.

Safety planning is an evidence-based brief intervention for promoting safety during times of heightened risk for suicide.

To guide clinicians in safety planning with older patients, we suggest a framework targeting key risk factors for suicide while addressing patient-level barriers common in later life (e.g., sensory and cognitive impairment).

Acknowledgments:

This paper is a collaborative effort of the Mental Health Practice & Aging Special Interest Group of the Gerontological Society of America (GSA); the authors would like to thank GSA staff, GSA annual conference organizers, and the other members of the Special Interest group.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth C. Conti, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center; Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX.

Danielle R. Jahn, Orlando VA Medical Center, Orlando, FL.

Kelsey V. Simons, VISN 2 Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention, Canandaigua VA Medical Center, Canandaigua, NY; Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester School of Medicine, Rochester, NY.

Lenis P. Chen-Edinboro, School of Health and Applied Human Sciences, University of North Carolina, Wilmington, Wilmington, NC.

M. Lindsey Jacobs, Geriatric Mental Health Clinic, VA Boston Healthcare System, Brockton Division, Brockton, MA; Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

Latrice Vinson, Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care Services, Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC; VISN 5 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center, Baltimore VA Medical Center, Baltimore, MD.

Sarah T. Stahl, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA.

Kimberly A. Van Orden, Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester School of Medicine, Rochester, NY

References

- Bryan CJ, Mintz J, Clemans TA, Leeson B, Burch TS, Williams SR, … Rudd MD (2017). Effect of crisis response planning vs. contracts for safety on suicide risk in U.S. Army Soldiers: A randomized clinical trial. J Affect Disord, 212, 64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2017). QuickStats: Age-Adjusted Rate for Suicide, by Sex — National Vital Statistics System, United States, 1975–2015. Retrieved from [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti E, Arnspiger C, Kraus-Schuman C, Uriarte J, & Batiste M (2016). Collaborative safety planning for older adults Retrieved from Washington, DC: https://www.mirecc.va.gov/VISN16/docs/Safety_Planning_for_Older_Adults_Manual.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Conwell Y, Van Orden KA, & Caine ED (2011). Suicide in older adults. The Psychiatric clinics of North America, 34(2), 451–468. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarra JM, Luciano MT, Gradus JL, & Wiltsey Stirman S (2015). Assessing Variability and Implementation Fidelity of Suicide Prevention Safety Planning in a Regional VA Healthcare System. Crisis, 36(6), 433–439. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvard Injury Control Research Center. (2019). Means Matter: Recommendations for Clinicians. Retrieved from https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/means-matter/recommendations/clinicians/

- Kayman DJ, Goldstein MF, Dixon L, & Goodman M (2015). Perspectives of Suicidal Veterans on Safety Planning: Findings From a Pilot Study. Crisis, 36(5), 371–383. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, & May AM (2015). The Three-Step Theory (3ST): A New Theory of Suicide Rooted in the “Ideation-to-Action” Framework. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 8(2), 114–129. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RC (2011). The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behavior. Crisis, 32(6), 295–298. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JA (2014). A changing epidemiology of suicide? The influence of birth cohorts on suicide rates in the United States. Soc Sci Med, 114C, 151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinholt EM, Mitchell JD, Butler JH, & Kumar H (2014). “Is there a gun in the home?” assessing the risks of gun ownership in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc, 62(6), 1142–1146. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B, & Brown GK (2008). Safety Plan Treatment Manual to Reduce Suicide Risk: Veteran Version. Retrieved from Washington, D.C: http://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/VA_Safety_planning_manual.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B, Brown GK, Brenner LA, Galfalvy HC, Currier GW, Knox KL, … Green KL (2018). Comparison of the Safety Planning Intervention With Follow-up vs Usual Care of Suicidal Patients Treated in the Emergency Department. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(9), 894–900. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B, Chaudhury SR, Chesin M, Pontoski K, Bush AM, Knox KL, & Brown GK (2016). An Emergency Department Intervention and Follow-Up to Reduce Suicide Risk in the VA: Acceptability and Effectiveness. Psychiatr Serv, appips201500082. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, & Joiner TE Jr. (2010). The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]