Summary

Lymphatic contractile dysfunction has been identified in several diseases, including lymphedema, yet a detailed molecular understanding of lymphatic muscle physiology has remained elusive. With the advent of genetic methods to manipulate gene expression in mice, a new set of tools became available for the investigation and visualization of the lymphatic vasculature. To gain insight into the molecular regulators of lymphatic contractile function, regulated primarily by the muscle cell layer encircling lymphatic collecting vessels, ex vivo approaches to allow control of hydrostatic and oncotic pressures and flow have been invaluable tools to complement in vivo methods. While the original ex vivo techniques were developed for lymphatic vessels from large animals, and later adapted to rat vessels, here we describe modifications that enable the study of isolated, pressurized murine collecting lymphatic vessels. These methods, used in combination with transgenic mice, can be powerful tools to probe the molecular and cellular mechanisms of lymphatic function.

Keywords: cannulation, pressure, diameter, contraction, perfusion, collecting lymphatic vessel

1. Introduction

Ex vivo methods to study pressurized large blood vessels have been around for decades (1) but were scaled down in the 1980’s for studies of small arteries and arterioles (7, 15). The scaling process borrowed heavily from perfusion techniques for renal tubules developed by Burg and colleagues at the National Institutes of Health (2). In the 1990s, the small vessel methods were adapted further for the ex vivo study of rat collecting lymphatic vessels (8, 13) and subsequently by us for mouse collecting lymphatic vessels (12, 14, 16). The following chapter describes the protocols used in our laboratories for the isolation, cannulation, and ex vivo study of mouse collecting lymphatic vessels. Although the detailed descriptions given here are specific for popliteal afferent lymphatics, they are readily adaptable to lymphatic vessels from several different anatomic regions of the mouse as we have reported recently (20). These methods are in large part modifications of techniques described for arterioles (4), with adaptations to control inflow and outflow pressures independently over a much lower pressure range, 0–20 cmH2O, corresponding to the intraluminal pressure range measured in mesenteric lymphatic networks of the rat (10, 22). Unfortunately, corresponding pressure measurements are not available for the mouse, but it is assumed that the pressure levels are comparable to, or perhaps slightly lower than, those in the rat. In vivo protocols for the study of mouse popliteal lymphatics are given in other chapters (Chp. 15, 18), and comparisons of in vivo and ex vivo methods are the subject of a recent review (19).

2. Materials

Prepare all solutions using ultrapure water (purified to 18 MΩ-cm at 25 °C) and analytical grade reagents.

2.1. Krebs solution supplemented with 0.5% BSA.

Krebs buffer: 146.9mM NaCl, 4.7mM KCl, 2mM CaCl2•2H2O, 1.2mM MgSO4, 1.2mM NaH2PO4•H2O, 3mM NaHCO3, 1.5mM NaHEPES, and 5mM d-glucose. Divide the solution in half, add 0.5% BSA to one half and adjust the pH of both to 7.4 at 37°C. (See Note 1).

2.2. Sharpened forceps, micro-scissors and clamps.

Use Moria forceps and Vannas scissors (Fine Science Tools #11399–87, #15369–00, respectively) for coarse dissection. Sharpen the tips to ~50μm using successive grades of Aluminum grit (Thomas Scientific #6775E38) adhered to a 1/8” thick piece of Lucite. Use another pair of the same forceps and scissors for fine dissection after sharpening the tips to 20μm. Sharpening procedures are described in ref. (7). (See Note 2).

Use Dumont 45° angled fine forceps (Fine Science Tools #11251–35), sharpened to 20-μm tips, for cannulation.

Use 2–3 small clamps (#18038–45 or 18054–28, Fine Science Tools, Foster City, CA) to hold open the skin incision during dissection.

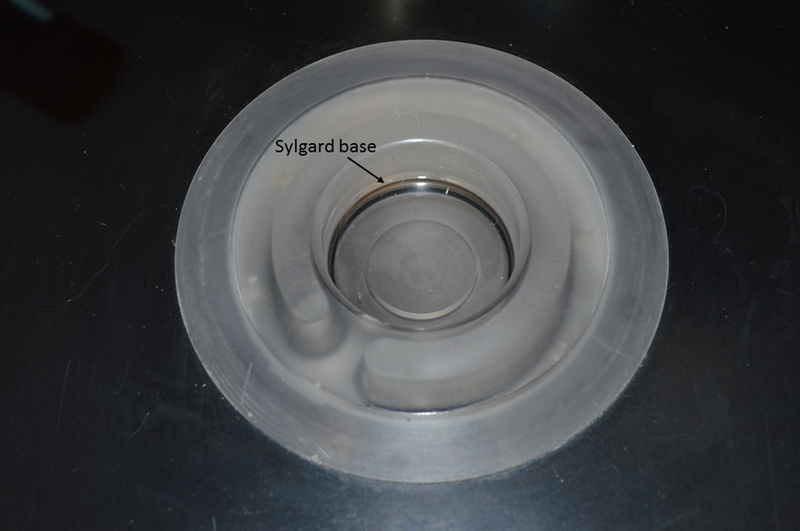

2.3. Dissection chamber, recessed into table (see Note 3).

The dissection dish should be recessed into a table top, allowing the operator’s elbows, forearms, and hands to rest on a stable base during the pinning and initial cleaning of the lymphatic vessel. See Fig. 2.

Figure 2-. Recessed dissection chamber.

The chamber opening is 5.3 cm in diameter; the depth is 2.5 cm of which 0.5 cm is filled with cured Sulgard.

2.4. Fine steel wire for pinning (See Note 4).

2.5. Two glass micropipettes with tip diameters 30–50 μm

Pull glass pipette tubing on a pipette puller or microforge. (See Note 5).

Lightly fire polish the pipette tips. (See Note 6).

Use a heated filament on a microforge to bend the tip 30° so that it matches the angle of the V-track system (or alternate pipette holder); once mounted, the end of the pipette should be parallel to the bottom of the cannulation chamber.

2.6. Syringes with filtered Krebs-BSA solution to fill pipettes

Fill two 10-mL syringes with Krebs + BSA.

Attach a 0.8 μm filter to each syringe.

Attach a 3-way stopcock and 16-gauge needle hub to each filter.

Attach a 1-foot length of PE-190 tubing (Intramedic, Fisher Scientific) to each needle hub.

With the stopcock turned appropriately, pressurize each syringe to fill the entire line with Krebs-BSA, making sure there are no remaining of air bubbles.

Attach each piece of tubing to a port on a pipette holder (or directly to the back of the cannulating pipette if not using a pipette holder). (See Note 7).

2.7. Two pipette holders with micromanipulator mounting system

Clamp the pre-filled cannulation pipettes to the manipulators. The manipulators must be mounted on a stable base platform to which the perfusion chamber is also mounted. (see Note 7).

Use the y-axis control to lower the pipette tip to about 2 mm above the surface of the glass slide that comprises the bottom of the cannulation/bath chamber. Use the x-axis control(s) to separate the pipette tips by about 1 cm in preparation for vessel cannulation.

2.8. 12–0 monofilament suture or teased strands of 4–0 silk suture (see Note 8).

Cut the suture to 2–3 mm lengths and pre-tied into single-tie loops using a loose surgical knot. This is best performed on a wetted Kimwipe (to help hold the suture in place and reduce static electricity), using the dissection microscope in advance of the experiment.

A loop of suture should be loosely secured to the shank of each glass micropipette tip before cannulating the vessel.

2.9. Dissection microscope, magnification range 8–64x (see Note 9).

2.10. Dual fiber optic light source (see Note 10).

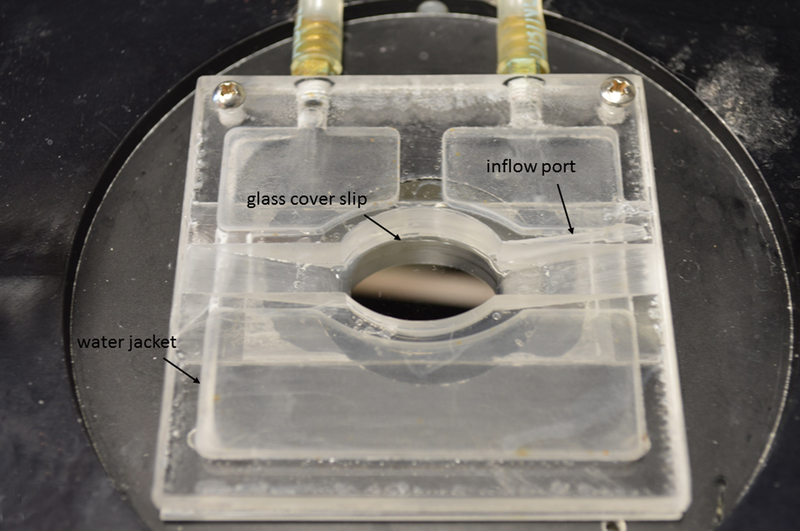

2.11. Heated perfusion chamber for the ex vivo experimental studies (see Note 11).

2.12. Inverted microscope (see Note 12).

2.13. Temperature-controlled water circulator and bath perfusion pump (see Note 13).

2.14. Pressure control system.

The simplest pressure control system is a single (or pair of) moveable reservoir(s) mounted on a post or wall (e.g. with pulley system) near the microscope. Inverted glass syringe (e.g. 30 ml) barrels can serve as reservoirs, connected through needle hubs to appropriate lengths of Silastic (Cole-Palmer) and/or polyethylene (Intramedic) tubing to the back of the glass cannulation pipettes. The zero point of the reservoir should be level with the vertical position of the vessel in the perfusion chamber after it is mounted on the microscope (e.g. 1–2 mm above the bottom glass surface of the chamber). The transmural pressure is the important variable determining vessel responses and may need to be corrected later for the depth of fluid covering the vessel. For simple experiments in which the inflow and outflow ends of the vessel will always be equal, only a single pressure reservoir is needed, with the outflow line connected to a T-tube and then to each cannulation pipette holder. If separate control of inflow and outflow pressure is needed, then two independently-adjustable reservoirs will be required.

For most experiments the tubing from the reservoir(s) to the pipette holders can be filled with distilled H2O because there will not be sufficient cumulative flow through the cannulated mouse vessel, even over several hours, to displace the 0.3–0.5 ml of Krebs-BSA in the connecting tubing / pipette holders / cannulating pipettes. However, protocols involving extended periods of unidirectional (forward) flow may require filling the entire inflow line with Krebs-BSA, which should then be thoroughly cleaned after each experiment.

If a more sophisticated (e.g. computer-controlled) two-channel pressure system is available, connect both it and the reservoir system to high-quality, 3-way stop-cocks (e.g. HPLC grade,; Hamilton, Reno NV) and connect the outflow ports to the backs of the cannulation pipettes or pipette holders. (see Note 14)

2.15. Video-camera, computer, and diameter measurement software (see Note 15).

3. Methods

Carry out all procedures at room temperature unless otherwise specified.

3.1. Surgical procedures to expose the popliteal afferent lymphatic vessels

A 6–8 week-old mouse (optimal age) is anesthetized with an injection of sodium pentobarbital or ketamine/xylazine, i.p. Once a surgical plane of anesthesia is reached, shave the dorsal surface of one hind-leg and place the mouse face down on a heating pad. Extend one hind leg and hold it in place with a piece of tape.

Using a dissection scope at low power (8x), locate the saphenous vein on the medial-dorsal surface of the hind leg and make a 1 cm-long incision over and parallel to the vein while gently pulling upward on the skin to avoid nicking the vein.

As soon as the skin is opened, moisten the exposed tissue with room-temperature Krebs-BSA. Pull the medial edge of the cut skin toward the animal’s midline and hold it open using 2–3 small clamps, spaced a few mm apart. Slide the wide end of a cotton-tipped applicator under the clamps so they are raised slightly and form a well that holds Krebs-BSA. Flush any loose hair or debris from the incision by dripping Krebs-BSA as needed from a syringe at the proximal end of the incision while using a suction tube at the distal end, formed from PE-190 tubing and connected to a vacuum line (with water trap).

3.2. Excise the vessel

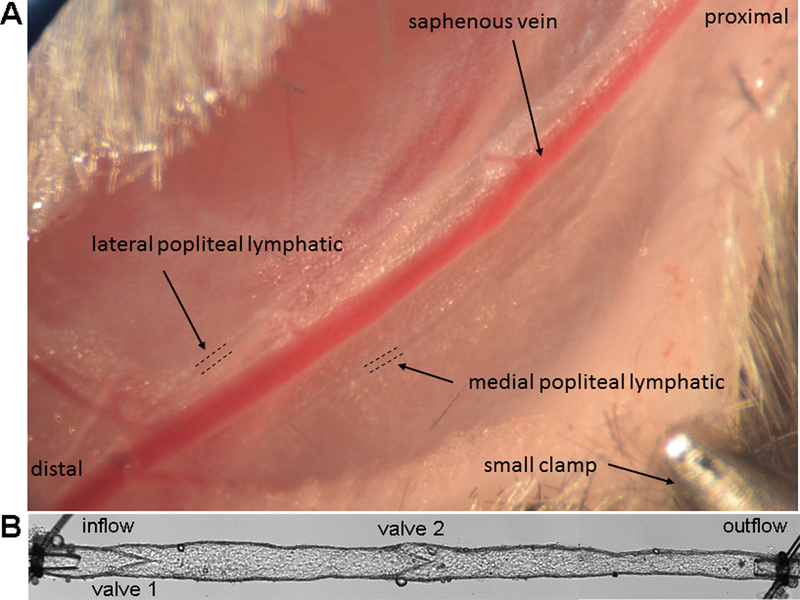

A pair of popliteal afferent lymphatic vessels run alongside and parallel to the saphenous vein from the ankle to the knee, deviating from the saphenous vein as they approach the popliteal node deeper behind the knee (See Fig. 1A; a short segment of each vessel is demarcated with dotted lines). With practice these vessels can be observed readily in younger mice (due to less perivascular adipose tissue) without the distal injection of any contrast agents (19). Use coarse micro-scissors to cut the loose connective tissue on the lateral side of the more superficial popliteal lymphatic (away from the saphenous vein) for a distance of 5–8 mm. The vessel will retract towards the saphenous vein.

Carefully grab the remaining loose connective tissue near the distal end of the vessel with one of the coarse forceps, being careful not to grab the vein, and pull it slightly upward. While still holding the loose connective tissue, use the coarse micro-scissors to cut between the popliteal lymphatic and the vein. Once they separate, cut the distal end of the vessel and, continuing to hold the loose connective tissue and severed end of the popliteal lymphatic and pulling it up slightly from the rest of the tissue (but still covered by Krebs-BSA), extend the cut between the popliteal lymphatic and the saphenous vein proximally. (It is also possible to first cut the proximal end, retaining lymph and pressure in the vessel and then work distally, but that method is more difficult for a beginner.) The lymphatic vessel, covered by connective tissue and fat will separate from the vein and cutting should become easier (without risk of nicking the saphenous vein) as the cut is extended. Stop when the vessel turns and runs deeper toward the popliteal node. The vessel can be dissected more proximally but at this point there should be at least 0.5 cm length of vessel free.

Cut the proximal end and, continuing to grasp the distal end, lift the vessel out of the animal and place it in a shallow 35-mm petri dish filled with Krebs-BSA. The BSA helps prevent the vessel from sticking to the forceps and other surfaces. If needed, the medial popliteal lymphatic can be removed using a somewhat similar procedure; the medial vessel tends to be more branched than the lateral vessel. If the vein is nicked, it will bleed profusely. In that case keep flushing the area with Krebs-BSA for 2–3 min until the bleeding stops; the vein will constrict, making both popliteal vessels easier to see and remove. If the area is flushed well to prevent blood from clotting around the popliteal vessels there will be no permanent damage to the lymphatics from the blood. (A similar procedure can be used to dissect lymphatic vessels from other regions of the mouse, with only minor modifications, as we have recently described (20); the dissection of mesenteric lymphatics is described in Ch. 4.)

Upon completion of this step, the animal can be removed from the heating pad and euthanized.

Figure 1-. Mouse popliteal lymphatic vessel surgery.

A) Photo of surgically exposed region of the mouse hindlimb showing the two popliteal afferent lymphatic vessels (diameter ~60 microns) coursing in parallel with the superficial saphenous vein. The skin overlying the region has been retracted using several small clamps (one clamp is shown). B) A photomontage of a cannulated popliteal afferent lymphatic; the diameter of the outflow pipette is 50 μm.

3.3. Set up pipettes and chamber

Both cannulation pipettes will be connected at their back ends to a 10-mL disposable syringe filled with Krebs-BSA. After filling the syringe, connect it to the luer port of a 0.8-μm disposable filter. Connect this filter to a 3-way stopcock that has a 16-gauge needle hub on the opposite end. Affix ~12” of PE-190 tubing to the 16 gauge needle hub. Pressurize the syringe to fill all of the components, taking care to avoid introducing small pockets of air.

Fill the perfusion chamber with filtered Krebs-BSA and then attach the syringe to the pipette holder (or pipette if not using a holder) and pressurize further to fill the holder, making sure not to leave any bubbles. Insert the pipette into the holder and pressurize the syringe to fill the pipette with buffer. Mount the pipette/holder to the micromanipulator.

Repeat this procedure for the other cannulation pipette.

3.4. Prepare the vessel for cannulation

Using a siliconized Pasteur pipette with fire-polished tip, transfer the excised popliteal lymphatic from the 35-mm petri dish to the recessed dissection dish, which should be pre-filled 0.5 cm deep with room temperature, filtered Krebs-BSA (see previous step, Fig. 2). Dissection in room temperature Krebs-BSA is preferred for rat and mouse lymphatic vessels, in contrast to arterioles, which require dissection at 4°C, necessitating the use of a cooling jacket around the dissection chamber.

Using the coarse forceps, grab a piece of 40-μm stainless steel wire and pin one end of the vessel to the Sylgard-coated bottom of the dissection chamber. Then grab the connective tissue covering the other end of the vessel, lengthen the vessel until slack is removed, and pin the other end. The pins should be driven through the connective tissue or fat rather than the vessel itself.

Use both fine forceps to gently tease and loosen the connective tissue/fat from the vessel by grabbing on both sides and pulling gently and equally in opposite directions. Be careful never to touch the wall of the vessel during this and subsequent procedures. As the connective tissue loosens, pull it away from the vessel with one pair of fine forceps and use the fine micro-scissors to cut close to the vessel wall. Repeat while moving along the length of the vessel. Take care to avoid overstretching the vessel, as this could damage the smooth muscle cells and prevent contractions during the experiment. It is not necessary to clean the vessel completely at this point and in fact it is not advisable because the lumen will be collapsed, difficult to see, and easy to nick inadvertently. Only the two ends of the vessel need to be cleaned well and will they be damaged during cannulation.

Once the vessel is cleaned, it will float to the surface if a sufficient number of fat cells remain attached; otherwise it will simply settle to the bottom of the chamber. Either way, draw it up into a Pasteur pipette and transfer it to the cannulation/bath chamber (Fig. 3) with mounted cannulation pipettes (Krebs-BSA in all).

A piece of 40-μm stainless steel wire, 5–8 mm in length can be used to weight the vessel down and keep it from floating; weighting is also helpful during the next step even if no fat cells remain attached.

Figure 3-. Cannulation/bath chamber.

Chamber has a water jacket and two connecting tubes with quick-connect/disconnect adaptors (Cole-Palmer). The water bath has the corresponding adaptors (not shown). Outer chamber edge is 6.5 cm on each side. A glass slide (0.17 mm thickness) is glued to the chamber bottom.

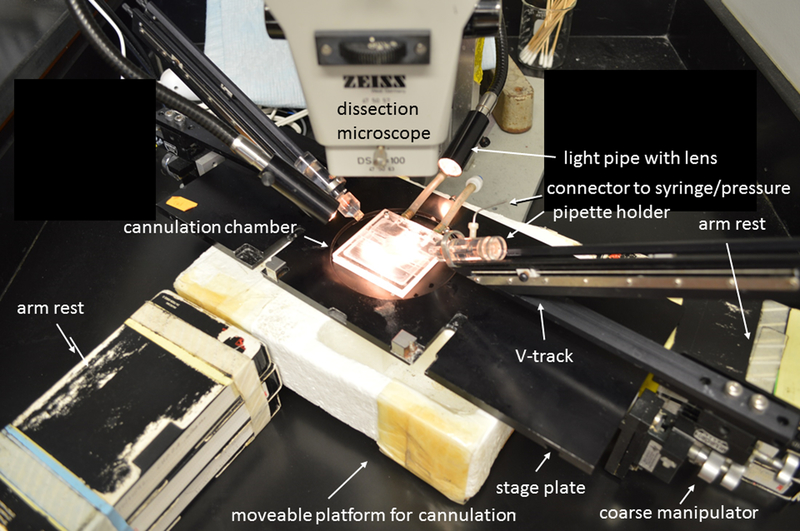

3.5. Adjust the stage and illumination

Position the stage assembly with pipettes/holders at a 45° angle relative to the operator (Fig. 4). Position the two fiber optic light guides as close as possible to the vessel/chamber to provide maximum illumination without interference from finger tips and surgical instruments; adjust the lenses appropriately for the distance used (typically 1–2 inches). Position the moveable arm rests so that the operator can reach each side of the vessel while keeping one cannulating pipette/holder/manipulator pointed at one of the operator’s shoulders (i.e. the large dissecting microscope objective will not allow the vessel to be oriented perfectly perpendicular to the operator).

During cannulation and cleaning, magnifications of 50–64x provide good resolution of the vessel ends while retaining some depth of field. Good lighting will aid in minimizing eye strain. Adjust the height of operator’s chair relative to the microscope eyepieces and chamber/stage; it is important to maintain good posture (e.g. a straight back) during the next few steps as they may require 1 hour or more of intense concentration. After extensive practice cannulation should take less than 10 min. Cleaning will require an additional 30–40 min. Vessel viability is in general inversely proportional to the amount of time required in Steps 3.6–3.8.

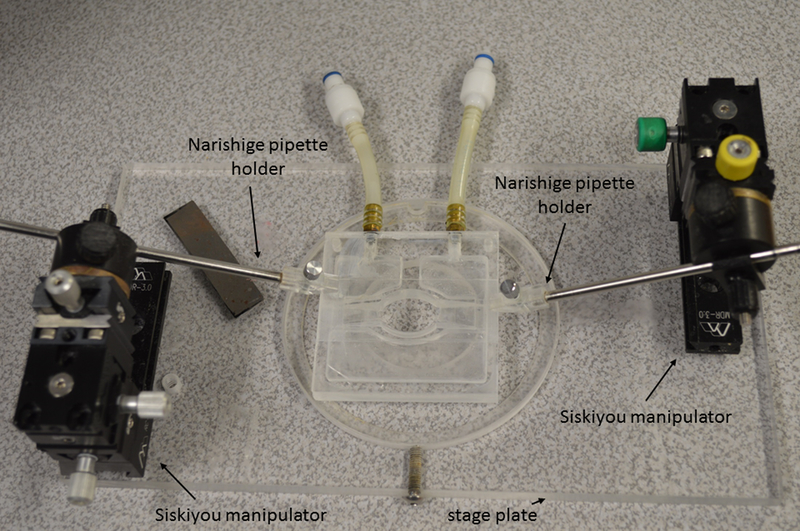

Figure 4-. Stage plate, manipulators and V-track pipette system.

Stage plate is shown with a pair of coarse micromanipulators (Narishige model MN-189) attached underneath, each supporting a V-tracks with a pipette holder for a cannulation pipette. Stage is raised onto a moveable platform so that the manipulators clear the surface of the table. Arm rests are positioned for right-handed operator to cannulate a lymphatic vessel in the cannulation chamber.

3.6. Cannulate the first vessel end

With one end of the vessel weighted down to the bottom of the perfusion chamber, lower one cannulation pipette close to, but not touching, the chamber bottom; the cut ends of the suture tied around the pipette tip will likely touch the bottom. The other pipette can be lowered to an intermediate depth. It is essential that the stopcock-syringe be opened to atmosphere prior to cannulation. The syringe should be turned and/or elevated so that the open port is 2–3 cmH2O above the level of the chamber, creating a slight positive pressure head prior to cannulation.

Grab the free end of the vessel (preferably the input end if orientation has been retained from Step 3.2) using the two 45° angled forceps and carefully pull in opposite directions on the crimped vessel end until the lumen appears to open partially. Slide that end onto the cannulating pipette, being careful not to force it; the slight positive pressure in the pipette will suddenly fill and expand the vessel if the pipette tip cleanly enters the lumen. Mouse vessels are covered in sticky, dense connective tissue that tightens like a Chinese finger trap (18) when pulled with too much force, so pull gently to open the vessel end while simultaneously attempting to slide the open end onto the pipette. If unsuccessful, remove the vessel from the pipette tip and rotate it, pulling from a different angle; repeat if necessary to partially open the lumen. Grabbing the vessel wall rather than the connective tissue around the wall, usually is required for a successful cannulation.

Expansion of the vessel for only part of its length upon approach of the open end to the cannulation pipette indicates that the outflow end is being cannulated, as any valves that are present will prevent retrograde flow from filling up the entire vessel. Either end can be cannulated first but cannulating the inflow end will result in the filling of the entire vessel and make subsequent cannulation of the outflow end easier.

Once the lumen is open and the vessel is filled or partly filled, loosen the suture tie, slide it over the end of the vessel and re-tighten it. Readjusting the tie can usually be performed with one forceps, while maintaining a hold on the vessel end with the other forceps to prevent the internal pressure from pushing it off of the cannulation pipette.

3.7. Cannulate the second vessel end

Using the z-axis control of the manipulator, raise the vessel off the chamber bottom 1–2 mm, adjust the z-axis control of the other manipulator so that the both pipette tips are in focus, and repeat Step 3.6 with the other vessel end and other cannulation pipette.

3.8. Clean the vessel

When both ends are cannulated, the lumen should be filled and distended over the entire length of the vessel, causing it to bow laterally between the cannulae. Use one manipulator (x-axis control) to move the pipettes apart in the axial direction and thereby eliminate slack from the vessel. A stretched vessel is easier to clean.

[This description is for a right-handed operator; reverse it for left-handed operator]. Starting at one end, grab the loose connective tissue on both sides of the vessel with the two 45° angled forceps and gently pull in equal and opposite directions, working around the circumference of the vessel. The tissue will slowly retract after it is released, so work in 200-μm segments. After the tissue and/or fat are loosened, pull the tissue away from the vessel (causing the vessel to bow slightly) with the left-hand forceps while using the fine micro-scissors to cut along the left edge of the vessel wall. The scissors will cross over the top of the vessel in order to cut along the left edge. The scissors must be very sharp and only the very tips should be used to cut. If necessary, anchor the scissors on the oval edge of the chamber (1–2 cm away) so that the scissor tips remain stationary and use the forceps to lift the connective tissue and vessel up to the scissors. Do not touch the wall with either the forceps or scissors. The vessel may occasionally contract during the cannulation procedure even with the vessel at room temperature. Contractions during the cleaning step can be used to one’s advantage if the connective tissue is held to one side during the contraction and a scissor cut is made close to the wall during the peak of the contraction.

Repeat this cleaning routine on the next 200-μm length segment and then move slowly toward the other cannulating pipette. If tissue remains on the right edge of the vessel, turn the entire stage assembly with cannulating pipettes 180° and repeat the procedure on the opposite vessel edge.

Repeat Step 3.8.1–3 two or three times, as necessary, to thoroughly clean the vessel. Depending on the design of the experiment, a clearly visible outer wall may be needed for diameter tracking only along a short section of the vessel, but that option also dictates that there should be no damaged areas of the wall and that the contraction amplitude of the vessel (when subsequently warmed) be consistent along the entire vessel length. Cleaning the entire length of the vessel provides options later for diameter tracking at various sites and/or assessment or exclusion of damaged areas.

Make sure that both pipette tips are still clear after the cleaning procedure by jiggling each syringe slightly and observing the vessel; the smallest movement of either syringe should cause the vessel to move as the luminal pressure changes slightly.

Finally, tighten both suture knots as needed. If the knots loosen later during the experiment (this will depend on the taper of the pipettes and the type of suture used), two sets of ties may be needed on each vessel end. A photomontage of a cannulated popliteal lymphatic from an SVF129 mouse is shown in Fig. 1B.

3.9. Mount the stage to the inverted microscope

Transfer the pipette/perfusion chamber/micromanipulator assembly to the inverted microscope and secure it to the stage.

Disconnect the PE or Silastic tubing from the 16-gauge blunt needle hub and reconnect it to the tubing from the pressure reservoir set at 3 cmH2O. It is imperative that the stopcocks be opened to the atmosphere when disconnecting and connecting the tubing; otherwise damaging levels of negative and positive intraluminal pressure, respectively, will be imposed on the vessel.

Connect the perfusion tube and suction tube to the chamber and begin bath perfusion with temperature control. (See Note 13). A typical vessel will begin to show slow, large-amplitude (>50% passive diameter) contractions within 10 min. These will accelerate in frequency and decline somewhat in amplitude as the bath temperature stabilizes at 37°C.

Allow 30–60 min for full equilibration and stabilization of contractions. Contraction frequency is very sensitive to temperature. Vessels will contract between 28–40°C but sustained temperatures >38°C often lead to declining function.

3.10. Conduct the experimental protocol

Numerous types of protocols are possible (19), including testing the effects of a) changes in intraluminal pressures, either inflow, outflow or both (17), b) changes in imposed flow by raising inflow pressure while simultaneously lowering outflow pressure (8) within certain ranges (negative outflow pressures will close the vessel), c) valve function tests (11) as described in Ch. 4, and d) bath application of endothelial-dependent (16) or independent (5) agonists/inhibitors.

3.11. Disassembly and cleaning

Pipettes can be reused if they are cleaned well after each experiment: remove the pipette from its holder, wash the outside with distilled water, connect the back end to a vacuum tube (with water trap), dip the tip in filtered distilled H2O for 20 secs, then HPLC-grade acetone for 20 sec and allow it to air dry for 20 sec, all while connected to suction.

Store in a covered dish.

Clean the pipette holders (disassemble if necessary) and the perfusion chamber after each experiment with 10% neutral detergent followed by a distilled H2O rinse, a rinse with 30% pure ETOH in distilled H2O, and another distilled H2O rinse.

The dissection chamber should be drained and rinsed several times with boiling-hot distilled H2O.

Hot distilled H2O should also be flushed liberally through the tubing in the bath perfusion pump and then allowed to air dry by running the pump for a few minutes.

Wash all surgical instruments carefully with distilled water and then 70% ETOH and store them in a protected case.

Figure 5-. Alternative stage plate, manipulators and pipette holders.

Manipulators are attached to the top of the stage plate and pipette holders clamp the pipette glass directly. The same cannulation/bath chamber is used.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health R01 HL-120867, R01 HL-122608, R01 HL-122578 to MJD, and R00 HL-124142 to JPS.

Notes

If unpurified BSA (e.g. Sigma #A2058) is used it should be extensively dialyzed and lyophilized or normal vessel reactivity may be affected. As an alternative use a more expensive BSA from US Biochemicals (#10856,Cleveland, OH), which is purified and lyophilized. Krebs+0.5% BSA is used to fill the dissection dish, the cannulating pipettes and holders and (initially) the perfusion chamber. Albumin-free Krebs is used to perfuse the chamber during the actual experiment.

The highest quality, hardened stainless steel instruments are preferable because they can withstand daily use and maintain fine points. We recommend two pairs of forceps and two pairs of scissors for each investigator. One “coarse” pair of each is sharpened to ~50μm tips and used for gross dissection (holding skin, removing the vessel, manipulating pins); the other “fine” pair of forceps and scissors is sharpened to 20μm tips and used only for fine dissection once the vessel is pinned down in the dissection dish. Once the instruments are sharpened they should be stored in protective cases such as those sold by Electron Microscopy Services (Ft. Washington, PA). Do NOT slide Silastic tubing over the sharpened tips (even if they are so supplied by the manufacturer) because it will press them together with too much force.

The inside of the dish is 5.3 cm in diameter, 2 cm deep, and layered with 0.5 cm of cured Sylgard 184 (Dow Corning).

We use 40-μm stainless steel wire (Danish Myo, Aarhus, Denmark) originally intended for wire-myograph studies. The wire is cut into 1.5–2 mm pieces to use as pins or in longer pieces to use as weights.

The type of capillary glass is not critical as long as the tip is the appropriate size and shape for cannulation (30–50 μm, with a straight barrel profile). Vessels may, over the course of an experiment, loosen or slip off tips that are tapered. We use Drummond R6 glass (0.084” O.D., 0.064” I.D.; Drummond Scientific Co. Broomall, PN 19008) and fashion the cannulating pipettes on a microforge as described in ref. (4) so that the shank rapidly tapers to short length (100–200 um) with parallel sides equal to the desired tip size. R6 glass fits the standard Burg-style pipette holders (2) originally manufactured at NIH. Alternatively, smaller diameter glass can be used and the pipettes simply pulled on a standard puller (e.g. Sutter Instrument Co., model P-97) but precise control of tip size will be more difficult. The tips of pulled glass tubing can be broken to approximately the desired size by bumping them gently against a flat surface while observing the process under a dissecting microscope, but this usually results in jagged edges (in contrast to the clean break and flat end possible using a microforge) that are more difficult to fire polish. A bevel-shaped tip may make cannulation easier but it may also be more susceptible to occlusion against the inside wall of the vessel during spontaneous contractions, particularly at low pressures.

Fire polishing is performed after the pipette is pulled to the desired diameter. The method is essentially the same as described for patch clamp pipettes (9) and should be carefully performed under 40–50x magnification so that the sharp outer edge is softened without reducing the internal diameter at the tip. Cannulation of a mouse lymphatic vessel with unpolished pipettes will usually result in puncture of the fragile vessel wall during subsequent cleaning of fat and adventitia as the vessel is manipulated during the cleaning procedure.

Burg-style pipette holders were designed to mount to and slide on a corresponding V-track system (Fig. 4) (Jim White Instruments, NIH or Vestavia Scientific, Birmingham, AL) which is secured to the underside of a stage plate using a pair of Narishige MN-189 coarse manipulators; however, new V-track systems are no longer available. A simple alternative system is to avoid a pipette holder altogether and connect the filled glass pipette directly with the appropriate size of Silastic tubing (Cole-Palmer); the fit should be snug to prevent pressure leaks, e.g. 0.125” I.D. tubing (cat. #508–008) fits Drummond #R6 glass. Narishige “electrode holders” can be used to clamp the glass (Narishige cat #H-12) to simple micromanipulators (Siskiyou Instruments, Grant’s Pass OR, #DT100-AB + DT3–100 with MXC clamp, RC-8C base, and MDR-3.0 mount for each side); see Fig. 5. The entire apparatus should be designed to fit on (or preferably lock to) the stage of the inverted microscope used for experiments.

We prefer 12–0 nylon black suture (14 μm in diameter) from S&T (Neuhausen, Switzerland); sterile suture is not required. This suture has the proper mix of bendability and tensile strength for mouse lymphatic vessels. A cheaper but more fragile alternative is to cut 1-cm lengths of 4–0 silk black braided suture (Ethicon) and tease apart the individual strands.

A high-quality dissection microscope is advisable because cannulation may take up to 1 hour, particularly when the operator is inexperienced. The use of a poorer quality microscopes (and/or poor illumination) will result in significant eye strain. We use Zeiss SV-80, Zeiss Stemi 508, or Leica S9i dissection microscopes; Greenough optics provide a true stereo light path, which greatly enhances the visual depth perception needed for successful cannulation. When cannulating, we use moveable armrests that are the same height as the level of the perfusion chamber when it is positioned under the dissection scope (but not necessary for the stage assembly shown in Fig. 5). The arm rests serve to stabilize the forearms (and thereby relieve muscle tension) during cannulation and fine cleaning of the vessel.

An inexpensive Fiber-Lite MI-80 illuminator with dual, flexible fiber optic + lenses (Dolan-Jenner, #EEG2836M) will work well. Once a vessel is pinned out, the best method of illumination is to use only one of the fiber optic guides, positioned at a 30–45° angle in such a way that ½ the field of view is dark and the other ½ is light, with the vessel in the midline. This pseudo-oblique illumination allows the walls and lumen of the vessel to be more easily distinguished from the overlying fat and connective tissue.

Any number of chamber designs will suffice. We prefer water-jacketed chambers (custom machined) for more stable temperature control (±0.3°C if fluid level is adjusted correctly). An alternative is a servo-controlled heating plate (e.g. RC-series small volume chamber with heating platform and temperature controller from Warner Instruments), but in our experience temperature varies ±1°C with that system and the fluid level is difficult to control and reproduce between experiments. Our custom-machined chambers are elliptical (18×25 mm), 0.5 cm deep, with 30° angled sides for the glass pipettes (see Fig. 3). The total volume is 3 mL. This width provides sufficient room for angled Dumont forceps during cannulation and the curved rim can be used to rest and steady the fine scissors when trimming away connective tissue once the vessel is cannulated.

Almost any inverted microscope with a camera port will suffice. Mounting the microscope on a vibration isolation table is preferred to prevent the introduction of vibration artifacts into the water-filled pressure lines. A moveable stage is preferable but not essential. For most studies, brightfield, Köhler illumination is all that is needed. Objectives can range from 2x for multi-valve segments up to 3 mm in length, to 16x for close-up views of intraluminal valves, to 40x for calcium imaging if the microscope is also equipped for fluorescence epi-illumination with the appropriate filters. An upright microscope alternatively could be used but dry objectives will fog with prolonged observation using an open, heated perfusion bath so an upright microscope should be equipped with a water immersion objective. In that case attention should be given to the manufacture of the pipettes (i.e. angled tips) so they are not touched by the objective when it is focused.

Our cannulation/bath chamber is water jacketed (Fig. 3) and a stable temperature is achieved by connection to a Lauda E100 (or similar) temperature-regulated water bath controller/pump. The chamber has quick-disconnect adaptors so it can be used under both the dissection and inverted microscopes. The set temperature of the water bath varies with the design of the perfusion chamber. We calibrate each of our chambers with the controller set points ranging from 50–60°C. Temperature is measured in the middle of the perfusion chamber close to the vessel with a Physiotemp BAT-12 thermistor. Exchange of the bath solution is critical for prolonged experiments. The osmolarity of non-perfused, open-top chambers will change sufficiently over a 20 min period to affect spontaneous contractions; frequency and amplitude will usually decline. Several types of perfusion pumps can be adapted to continuously perfuse and exchange the bath. We use a Gilson Minipuls 3 pump, with Silastic tubing (Cole-Palmer #96449–48) for a single channel connected to PE-190 tubing that terminates in PE-60 tubing, which slides into a channel drilled into one side of our perfusion chamber. The perfusion rate of Krebs solution is set to 0.4–0.5 mL/min. A suction tube terminating in PE-90 is placed on the opposite end of the chamber, held even with the top surface; it should have a beveled end that faces upward; we anchor the tube with wax or tape so that it is easily adjusted. This tube is connected to a vacuum line (with water trap). Positioning of the suction tube is critical to determining the bath fluid level of the chamber, which in turns affects the bath temperature; the ideal level is one that is flush with the top surface of the chamber.

A reservoir system is preferable for initial set up and vessel equilibration. A computer-controlled system is preferable to run the actual experiment. One caution with moveable reservoir systems is that large pressure transients can occur at the level of the vessel when the reservoir is moved, depending on the system used to move it. More sophisticated pressure control systems include microfluidic devices such as the 2-channel systems from Fluigent (Villejuf, France) or Elveflow (Paris, France). We have successfully used both systems in addition to our own custom system described in previous papers (6, 21).

Digital monochrome cameras are best suited for ex vivo vessel studies; color cameras offer little advantage. The camera should be interfaced to a computer with the appropriate image acquisition hardware and software. We use a Basler 641f firewire camera, bypassing the need for a frame grabber card if the computer is equipped with a firewire port. This camera has a resolution of 1632×1224 pixels at 14 fps. If the vessel image is turned horizontally, the progressive scan field can be adjusted vertically until it is just wider than the vessel, allowing for much higher acquisition speeds, e.g. 40 Hz is typical for our applications. We use LabVIEW (National Instruments, Austin TX) for in-house video and data acquisition and diameter tracking software. A few automated diameter tracking systems are commercially available, e.g. from Danish Myo (Aarhus, Denmark) or IonOptix (Westfield, MA). These are very accurate for outside edge detection but much less so for internal diameter measurement. We use our own method for inner diameter measurement (3).

Make sure the vessel is untwisted. After cannulation is complete and the vessel is cleaned, extravascular tethering forces are minimal and the vessel may have become twisted during the procedure. This can lead to diameter tracking artifacts (i.e. tracking wall twisting rather than contraction) and most often will damage the vessel at the site of twisting such that two pacemaking sites, rather than a single one, will appear. The best method to prevent twisting is to carefully observe the orientation of the attached fat/connective tissue prior to cleaning. If the fat encircles the vessel in a spiral, the vessel is twisted. In that event, loosen the tie at one end, grab the end of the vessel with 45° angled forceps and rotate it around the tapered shank of the pipette until the lines of fat cells on both sides of the vessel run in parallel.

If a branch is revealed during/after cleaning, consider advancing one of the cannulating pipettes past the branch point: loosen the tie on that pipette and then retie the suture after the branch so that it is not part of the vessel segment under study. Here, the taper of the pipette tip will determine how far the pipette can be advanced inside the vessel (a wide taper will limit the advance). Most branches are sealed during the initial excision step and will remain sealed unless they are trimmed extremely clean and/or pressure is raised to high levels during subsequent protocols. Thus, if a branch is spotted during cleaning one option is to leave it alone and monitor it throughout the protocol, but this is not preferred.

Detecting incomplete cannulations. Poor cannulations will plague beginners. Tapping or raising the syringe connected to the pipette is the best way to determine a successful cannulation. If the vessel does not expand immediately when the syringe is raised there are two likely causes. 1) Complete occlusion: If the vessel appears to be cannulated but raising the syringe does not result in any appreciable movement of the vessel or expansion of the lumen, the pipette tip is occluded. During cannulation the endothelial layer easily can become separated from the smooth muscle layer so that it folds over the tip of the pipette during cannulation, occluding the pipette. In this event it is necessary untie the suture and slowly pull the vessel off the pipette; the folded endothelium will unravel and after it detaches from the pipette tip, it can be cut off using the fine micro-scissors. Then reopen and recannulate the vessel end. Another cause of complete occlusion on the output valve end is that the pipette tip may be jammed up against a closed output valve. In that case loosen the tie and pull back slightly on the pipette (x-axis control), if possible, until the tip is no longer touching the valve and retie the suture; raise/lower the syringe while watching the valve to make sure the leaflets can open/close freely. If there is not sufficient length of the outflow segment to permit this, then the vessel should be cut in the upstream side of that valve and recannulated. Forcing the pipette backwards through a closed valve will often plug the pipette. 2) Partial occlusion: Weak or delayed expansion of the vessel after raising the syringe indicates a partially occluded tip. This can be the result of connective tissue being folded into the lumen or the tip touching the inner surface of the vessel wall (particularly a beveled tip). The solution is to untie the suture, then advance the pipette tip further into the lumen and repeat the syringe pressure test; if it fails again, pull the vessel off completely, reopen it and recannulate. Another cause may be an air bubble or particulate matter in the syringe line or the pipette, in which case the vessel must be removed from the pipette tip, the stopcock turned and light pressure applied to the syringe plunger to flush the bubble/material out of the pipette tip. After the pipette is clear be sure to open the stopcock back to atmosphere before recannulating the vessel.

References

- 1.Bayliss WM. On the local reactions of the arterial wall to changes of internal pressure. Journal of Physiology 28: 220–231, 1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burg MB, and Orloff J. Perfusion of isolated renal tubules In: Handbook of Physiology, Renal Physiology, edited by Orloff J, and Berliner RW. Washington,D.C.: American Physiological Society, 1973, p. 145–159. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis MJ. An improved, computer-based method to automatically track internal and external diameter of isolated microvessels. Microcirculation 12: 361–372, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis MJ, Kuo L, Chilian WM, and Muller JM. Isolated, Perfused Microvessels In: Clinically Applied Microcirculation Research, edited by Barker JH, Anderson GL, and Menger MD. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, 1995, p. 435–456. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis MJ, Lane MM, Davis AM, Durtschi D, Zawieja DC, Muthuchamy M, and Gashev AA. Modulation of lymphatic muscle contractility by the neuropeptide substance P. American Journal of Physiology (Heart and Circulatory Physiology) 295: H587–H597, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis MJ, Scallan JP, Wolpers JH, Muthuchamy M, Gashev AA, and Zawieja DC. Intrinsic increase in lymphatic muscle contractility in response to elevated afterload. American Journal of Physiology (Heart and Circulatory Physiology) 303: H795–H808, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duling BR, Gore RW, Dacey RG Jr., and Damon DN. Methods for isolation, cannulation, and in vitro study of single microvessels. American Journal of Physiology (Heart and Circulatory Physiology) 241: H108–H116, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gashev AA, Davis MJ, and Zawieja DC. Inhibition of the active lymph pump by flow in rat mesenteric lymphatics and thoracic duct. Journal of Physiology 450: 1023–1037, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, and Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Archives European Journal of Physiology 391: 85–100, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hargens AR, and Zweifach BW. Contractile stimuli in collecting lymph vessels. American Journal of Physiology (Heart and Circulatory Physiology) 233: H57–H65, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lapinski PE, Lubeck BA, Chen D, Doosti A, Zawieja SD, Davis MJ, and King PD. RASA1 regulates the function of lymphatic vessel valves in mice. J Clin Invest 127: 2569–2585, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maejima D, Kawai Y, Ajima K, and Ohhashi T. Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF)-BB Produces NO-Mediated Relaxation and PDGF Receptor b-Dependent Tonic Contraction in Murine Iliac Lymph Vessels. Microcirculation 18: 474–486, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizuno R, Dornyei G, Koller A, and Kaley G. Myogenic responses of isolated lymphatics: modulation by endothelium. Microcirculation 4: 413–420, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizuno R, Ono N, and Ohhashi T. Parathyroid hormone-related protein-(1–34) inhibits intrinsic pump activity of isolated murine lymph vessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H60–66, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osol G, and Halpern W. Myogenic properties of cerebral blood vessels from normotensive and hypertensive rats. American Journal of Physiology 249: H914–H921, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scallan JP, and Davis MJ. Genetic removal of basal nitric oxide enhances contractile activity in isolated murine collecting lymphatic vessels. Journal of Physiology 591: 2139–2156, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scallan JP, Wolpers JH, Muthuchamy M, Zawieja DC, Gashev AA, and Davis MJ. Independent and interactive effects of preload and afterload on the lymphatic pump. American Journal of Physiology (Heart and Circulatory Physiology) 303: H809–H824, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolinsky H, and Glagov S. Structural basis for the static mechanical properties of the aortic media. Circulation Research XIV: 400–413, 1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zawieja SD, Castorena-Gonzalez JA, Dixon B, and Davis MJ. Experimental models used to assess lymphatic contractile function. Lymphat Res Biol (in press): 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Zawieja SD, Castorena-Gonzalez JA, Scallan J, and Davis MJ. Differences in L-type calcium channel activity partially underlie the regional dichotomy in pumping behavior by murine peripheral and visceral lymphatic vessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Zhang R, Gashev AA, Zawieja DC, Lane MM, and Davis MJ. Length-dependence of lymphatic phasic contractile activity under isometric and isobaric conditions. Microcirculation 14: 613–625, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zweifach BW, and Lipowsky HH. Pressure-flow relations in blood and lymph microcirculation In: Handbook of Physiology Section 2: The Cardiovascular System, Volume IV, Chp 7, p297, edited by Renkin EM, and Michel CC. Bethesda, Maryland: American Physiological Society, 1984, p. 251–307. [Google Scholar]