Abstract

The present review focuses on the role of one of the D-series resolvins (Rv) RvD1 in the regulation of conjunctival goblet cell secretion and its role in ocular surface health. RvD1 is the most thoroughly studied of the specialized proresolution mediators in the goblet cells. The anterior surface of the eye consists of the cornea (the transparent central area) and the conjunctiva (opaque tissue that surrounds the cornea and lines the eyelids). The secretory mucin MUC5AC produced by the conjunctival goblet cells is protective of the ocular surface and especially helps to maintain clear vision through the cornea. In health, a complex neural reflex stimulates goblet cell secretion to maintain an optimum amount of mucin in the tear film. The specialized pro-resolution mediator, D-series resolvin (RvD1) is present in human tears and induces goblet cell mucin secretion. RvD1 interacts with its receptors ALX/FPR2 and GPR32, activates phospholipases C, D, and A2, as well as the EGFR. This stimulation increases the intracellular [Ca2+] and activates extracellular regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 to cause mucin secretion into the tear film. This mucin secretion protects the ocular surface from the challenges in the external milieu thus maintaining a healthy interface between the eye and the environment. RvD1 forms a second important mechanism along with activation of a neural reflex pathway to regulate goblet cell mucin secretion and protect the ocular surface in health.

Keywords: Conjunctiva, Goblet cells, Allergic eye disease, Dry eye disease, Ocular surface, Mucins, Tear film, Signaling pathways, Resolvin D1, Inflammation, secretion

1.0. Tear Film, Cornea, and Conjunctiva

1.1. Introduction-

The present review focuses on the role of one of the D-series resolvins (Rv) RvD1 in the regulation of conjunctival goblet cell secretion. RvD1 is the most thoroughly studied of the specialized proresolution mediators in the goblet cells. This review is also focused on the role of RvD1 in maintenance of ocular surface health, but not its role in disease.

1.2. Function of Tear Film and Ocular Surface-

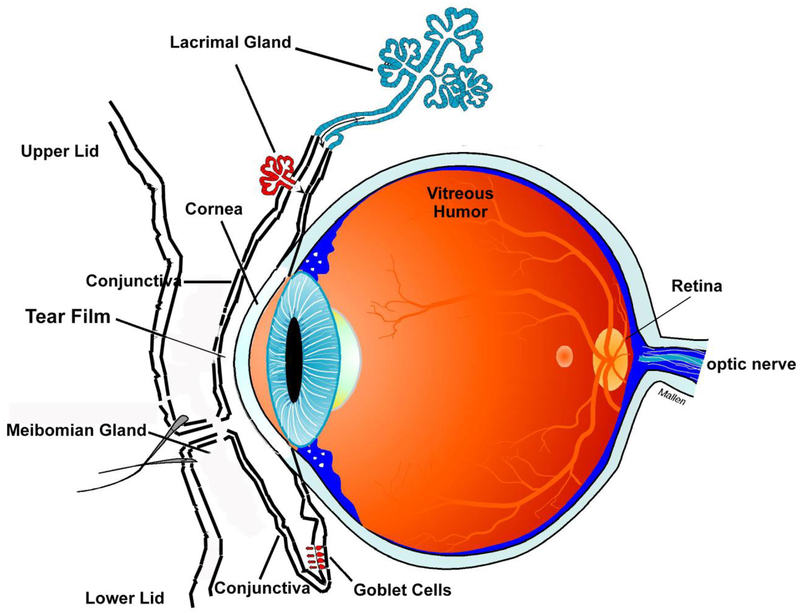

The eye is a unique, specialized organ whose function is to provide a clear optical path for image presentation on the retina and its analysis by the brain (Fig 1). The first optical surface in the eye is the tear film that overspreads the cornea, a transparent avascular tissue. Together the tear film and cornea provide most of the refractive power of the eye [1]. The tear film and the cornea are among the first components of the anterior eye aided by the conjunctiva to interact with the external environment. The conjunctiva is a vascular, optically dense tissue that surrounds the cornea and lines the eyelids. Together the tear film and ocular surface tissues (cornea and conjunctiva) form the outermost protective layer that functions to maintain a transparent, healthy and impermeable cornea [1]. These components each have unique properties that contribute to the protection of the eye from mechanical, thermal, and chemical injury; desiccation; allergens and pollutants; and pathogens from the external environment.

Figure 1.

Scehmatic diagram of the eye and ocular surface.

At the basal aspect, the cornea consists of a single layered endothelium, overlaid by stroma containing keratocytes, and on the apical side a multi-layered epithelium. One of the major protective properties of the cornea is that it is a very tight epithelium with limited permeability [1]. It is difficult to permeate the corneal epithelium because of the extensive tight junctions and other types of junctions between the topmost layers of cells. For example, bacteria cannot penetrate the corneal epithelium unless it is damaged [2]. Furthermore, the cornea is an immune privileged site and maintains an immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory environment preventing immune cells from migrating into the cornea or aqueous humor in response to an immune or inflammatory challenge [3]. When injured the cornea normally heals rapidly with minimal scarring and no blood vessel ingrowth. The number of mechanisms that the cornea can use to respond to the external environment is limited and often constrained, as this tissue needs to preserve transparency and remain avascular to ensure clear vision.

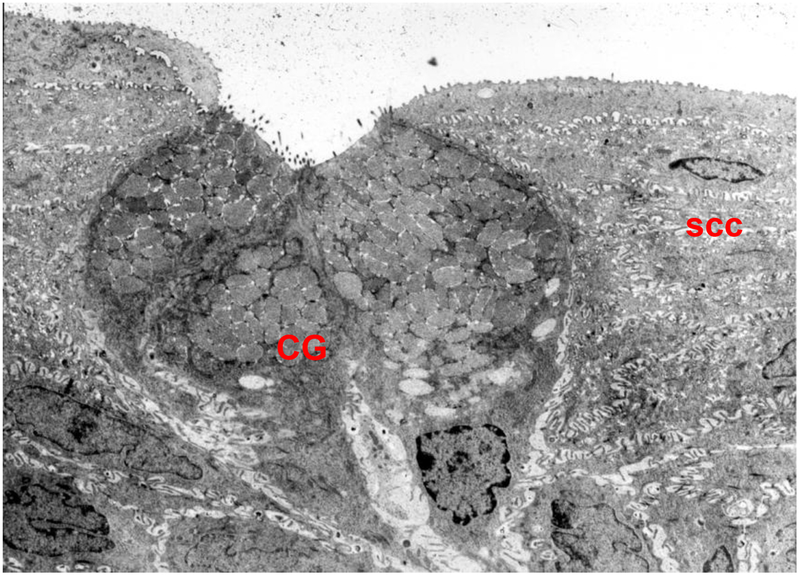

The conjunctiva, the focus of this review, surrounds the cornea and lines the lids. One of its major functions is to secrete electrolytes, water, and multiple types of mucins that together form the glycocalyx and the inner layer of the tear film [4]. The conjunctiva is a stratified squamous epithelium that overlies a loose, disorganized stroma containing plentiful blood vessels and nerves. This epithelium consists of two major cell types, stratified squamous cells and goblet cells (Fig 2) [4]. Stratified squamous cells are multilayered, have complex interdigitated lateral membranes, and contain a plethora of small clear vesicles. The second cell type is the goblet cells [5]. These cells occur singly or in clusters and span the entire epithelium in rodents, but only occupy the mid portion of the epithelium reaching to the surface in humans [5]. The goblet cells are polarized with a basal nucleus, substantial Golgi apparatus, and a plethora of secretory granules that occupy most of the cell volume and reach to the apical membrane and the tear film. The stratified squamous cells and the goblet cells both produce the mucous layer of the tear film but release different types of mucins. Both cells secrete electrolytes and water,.

Figure 2.

An electron micrograph of rat conjunctival goblet cells (GC). Numerous secretory vesicles can be seen in the apical portion of the cells, while nuclei can be seen in the basal portion. ssc, stratified squamous cells. Magnification ×6000. Reprinted from Dartt, D. A. Regulation of mucin and fluid secretion by conjunctival epithelial cells. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 2002, 21: 555–576.

Secretion of mucins is one of the major protective mechanisms of the conjunctiva. The mucins produce an extensive glycocalyx and the soluble mucous layer that overspreads both the cornea and conjunctiva. Stratified squamous cells produce the membrane spanning mucins MUC1, MUC4, MUC16, and MUC20 (for a review see [6]). These mucins help form the glycocalyx, a thick coat of carbohydrates that emerges from the apical membranes of epithelial cells and protects the corneal and conjunctival surface. The glycocalyx interfaces with the tear film. The glycocalyx is critical to maintaining the barrier function of the cornea, preventing access of microbes to the plasma membrane, and preventing apical adhesion [7]. In contrast, the goblet cells secrete the large soluble, gel-forming mucin MUC5AC [8]. This mucin is the major component of the inner mucous layer of the tear film and is essential for ocular surface health. MUC5AC upon secretion by the goblet cells overspreads the entire ocular surface including the cornea. It protects the underlying epithelia as a mucus gel by preventing attachment of bacteria and keeping them suspended in the gel. The water and electrolytes in the gel keep the ocular surface hydrated. The movement of the mucus gel across the ocular surface into the lacrimal drainage ducts removes particles, pollutants, and other environmental components from the ocular surface. Goblet cells and their secretion of MUC5AC are regulated by nerves. Afferent sensory nerves and efferent parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves extend into the conjunctival epithelium interdigitating between the stratified squamous cells. Efferent parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves surround the goblet cells. The localization of the nerves in the epithelium provides the basis for these epithelial cells to respond quickly to changes in the external environment by secretion of MUC5AC into the tears.

The conjunctiva has multiple protective mechanisms in addition to the secretion of MUC5AC. As the conjunctival epithelium is opaque, well vascularized, and very permeable, unlike the cornea, it is not constrained in its responses to the environment. The conjunctiva in fact can respond very robustly. The conjunctiva contains conjunctival associated lymphoid tissue that is part of the mucosal immune system [9]. In addition the conjunctival stroma contains numerous different cells for innate defense (macrophages, neutrophils, and mast cells) and for immune protection (lymphocytes, plasma cells, and dendritic cells). In addition for the innate defense system the conjunctiva has most of the Toll-like receptors [10], multiple NOD-like receptors, and a constitutively assembled NLRP3 inflammasome poised for activation [11, 12]. The conjunctiva also has goblet cell associated passages (GAPs) that are openings between goblet cells that allow the stroma to sample antigens and other immune activating material in the external environment[13]. These GAPs are under parasympathetic muscarinic control.

1.3. Role Goblet Cells in Ocular Surface Health-

As goblet cells and their secretion of MUC5AC are critical for ocular surface health, both a decrease and an increase in goblet cell mucin secretion leads to ocular surface disease. Loss of goblet cells from the conjunctival epithelium and depletion of MUC5AC in the tear film lead to serious damaging, painful ocular surface diseases such as dry eye and vitamin A deficiency [14]. Increase in goblet cell mucin in the tear film is also characteristic of specific diseases, such as ocular allergy, that upset ocular surface homeostasis and can be damaging to the ocular surface. The finding that both a decrease and an increase in goblet cell mucin secretion leads to disease suggests that goblet cell mucin secretion must be tightly regulated to maintain an optimal amount of mucin in the tear film [6, 8, 15].

In health neural regulation of goblet cell mucin secretion provides this regulation[16, 17]. Using a complex neural reflex, goblet cell mucin secretion can be exquisitely regulated to respond to changes in the external environment to secrete mucins as needed to protect the occur surface [18]. Corneal and conjunctival afferent sensory nerves are activated by changes in temperature, acid or bases, or mechanical stimuli (including trauma and particulates that occur in pollution), for examples. The stimulated afferent nerves then activate the trigeminal ganglion that by a complex neural reflex within the brain activates efferent parasympathetic nerves In the conjunctiva parasympathetic nerve endings surround the goblet cells and stimulate them to secrete mucins into the tear film [17]. The goblet cells also likely secrete electrolytes and water, but the evidence for this is indirect [19, 20].

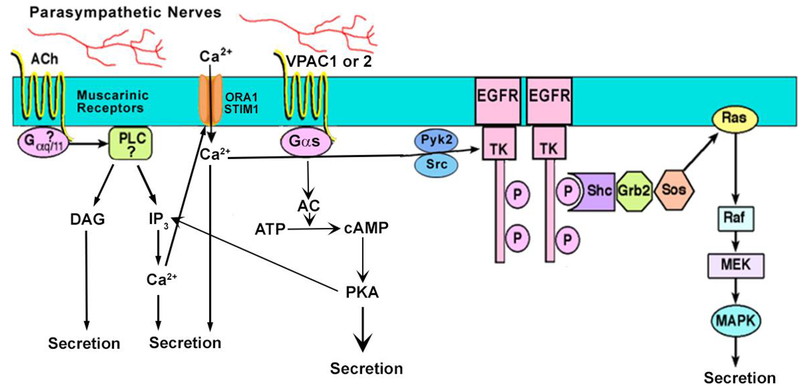

Parasympathetic nerves are the major stimulus of goblet cell mucin secretion in health [16, 21, 22] (Fig 3). There is no published evidence for the role of sympathetic nerves in this secretion. Parasympathetic nerves release the neurotransmitters acetylcholine that activate muscarinic receptors (MAchR) type 1, 2, and 3 and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) that uses the VIPAC1 and 2 receptors [21]. Both acetylcholine (carbachol is used experimentally) and VIP stimulate secretion by increasing intracellular [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]i) and activating extracellular regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 also known as p44/p42 mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) [13, 23]. In addition VIP activates adenylyl cyclase to increase the cellular cAMP level (For a review see [24]). Acetylcholine (carbachol), but not VIP, also works by activating a matrix metalloproteinase to cause ectodomain shedding of EGF to stimulate the EGFR that in turn increases [Ca2+]i and activates ERK1/2 to stimulate goblet cell secretion [22].

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of cholinergic pathway leading to goblet cell mucin secretion. Muscarinic receptors activate phospholipase C (PLC) to generate the production of inositol trisphosphate (IP3), which releases intracellular Ca2+ and diacylglycerol (DAG), which activates protein kinase C (PKC). The EGF receptor (EGFR) is transactivated leading to the activation of Ras, Raf, mitogen activated kinase kinase (MEK), and ERK 1/2. Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) binds to its receptors VPAC1 or 2 to activate adenylyl cyclase (AC) to generate cAMP from ATP. cAMP then activates protein kinase A (PKA) to stimulate secretion. Reprinted from Hodges et al. Encyclopedia of the Eye, Dartt D, Dana R, Besharse J eds. Elsevier, 2010.

Thus under normal conditions, the parasympathetic neurotransmitters use a common intracellular signaling pathway, an increase in [Ca2+]i and activation of ERK1/2 to stimulate mucin secretion by inducing exocytosis and release of all the secretory granules within a given goblet cell [25]. The molecular mechanism by which the exocytosis occurs is unstudied in the goblet cell. This pathway is tightly regulated in response to neural activation of the cornea and conjunctiva to maintain an optimal mucin layer that is critical for a healthy ocular surface.

As there is far less research on the conjunctiva than the cornea, the mechanisms used by the conjunctiva to respond to the environment are only beginning to be described. The role of the specialized pro-resolving mediator (SPM) resolvin D1 (RvD1) is one of these mechanisms and is the topic of the present review.

2.0. Specialized Pro-resolving Mediators

The SPMs comprise four families, lipoxins, resolvins, protectins, and maresins. The SPMs function in the resolution phase of acute inflammatory diseases and each family possess unique bioactions to resolve inflammation [26]. Each family of mediators has very potent actions as well as being structurally distinct, displaying stereospecific actions, and utilizing different biosynthetic pathways. Lipoxins are biosynthesized from the omega 6 fatty acid arachidonic acid after class switching from production of pro-inflammatory mediators. The omega 3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is precursor for the biosynthesis the D-series resolvins, the protectins, and the maresins. The omega 3 fatty acid, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) is precursor for the biosynthesis of the potent E-series resolvins. Each member of the RvD (RvD1–6) and RvE (RvE1 and 2) families possesses unique structures and has distinct functions in the treatment of disease in animal models and in cells.

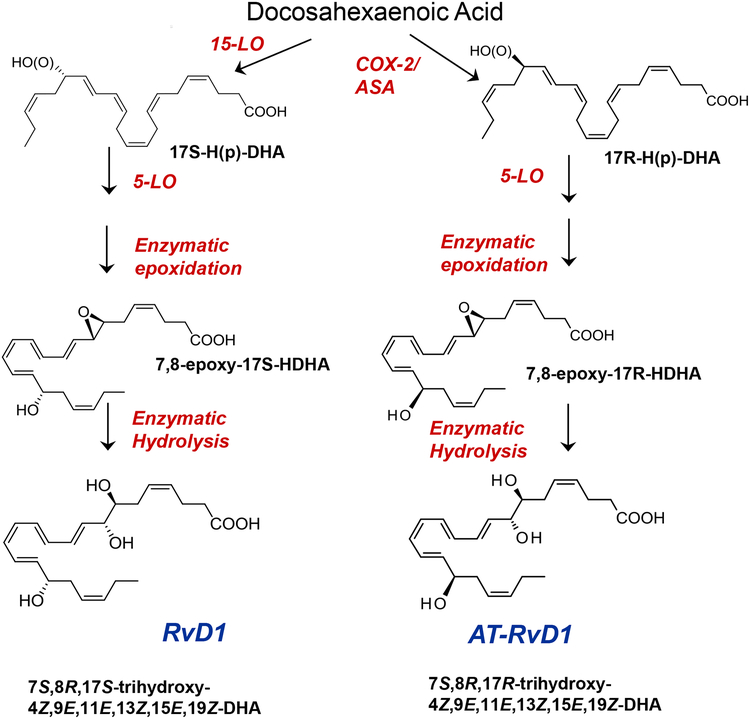

The enzymes responsible for this biosynthesis are the lipoxygenases (LOX) 5-LOX and 12/15 LOX. The location and specificity of the LOXs are cell and tissue specific. This determines the type and amount of SPM produced. In general 15-LOX and 5-LOX are needed to produce lipoxins from arachidonic acid. 5-LOX is required to biosynthesize E-series resolvins. 15-LOX and 5-LOX biosynthesize D-series resolvins and protectin (Fig 4). 12-LOX biosynthesizes maresins. There is little published information on LOX enzymes in the conjunctiva and especially the goblet cells. Several articles from the 1980s found that the normal, uninflamed conjunctiva from various species of animals has the capacity to synthesize both cyclooxygenases and lipoxygenases [27, 28]. The cycloxygenase was higher than the lipoxygenase activity. The major lipoxygenases produced by the conjunctiva were 12-HETE, 5-HETE, and 5,12-diHETE suggesting production of hepoxilin and LTA4. Subsequently conjunctiva and eyelids were demonstrated to possess EPA lipoxygenase products of the 5-series suggesting the capability of producing E-series resolvins [29].

Figure 4.

Synthetic Pathways of theD-series specialized pro-resolving mediators. Each is derived from DHA. 5-LO: 5 lipoxygenase Modified from Sun Y, Oh SF et al. J Biol Chem 282:9323–9234, 2007.

There is substantial work on the LOX enzymes in the cornea and the draining lymph nodes of the eye that contribute to ocular surface disease especially [30–32], 5- and 15-LOX are the rate limiting enzymes responsible for the generating SPMs [33]. The corneal epithelium has high expression of 15-LOX and functions as part of a LXA4-ALX/FPR2 circuit that controls wound healing and immune response in the cornea. In particular there is a population of tissue specific polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) that contain especially high amounts of 15-LOX and that in a sex-specific manner play a role in exacerbating autoimmune dry eye disease in females. These PMNs were detected in the lacrimal gland, draining lymph nodes, and limbus of the cornea. As the cornea and its limbus is adjacent to the conjunctiva, it is possible that conjunctival epithelial cells also have elevated levels of 15-LOX. Furthermore, conjunctival goblet cells are a target of disease in autoimmune dry eye. Study of ocular surface disease has shown the presence of high levels of the biosynthetic enzymes for the SPMs and the circuits for their regulation. These enzymes could also function in health especially as during eye closure in sleep PMNs migrate into the tear film and could interact with the conjunctival epithelial cells to set up a transient, low level activation of a LXA4-ALX/FPR2 like circuit or other circuits potentially in the conjunctiva. The same enzymes produce RvD1 and could be critical for regulating RvD1 biosynthesis in conjunctival goblet cells.

In addition to the production of SPMs in disease, SPMs are also endogenously produced in human tissues rich in omega 3 fatty acids in the absence of disease [34]. Thus SPMs are produced in human milk [35, 36], blood [37, 38], brain [39], and retina [40]. SPMs are major players in the regulation of ocular surface health as SPMs are detected in the tear film and stimulate conjunctival goblet cell mucin secretion under physiologic conditions. They function to maintain an optimum mucin layer of the tear film in response to the normal changes in the cornea and conjunctiva and to the extracellular environment. Multiple SPM family members are present within emotional human tears and stimulate goblet cell secretion to maintain the healthy tear film[41]. Herein we will review the evidence for the role of the D-series resolvin RvD1 in conjunctival health.

3.0. RvD1 Is Present in Tears from Healthy Individuals

A number of eicosanoids as well as SPMs are found in human tears. Human emotional tears were collected from six male and six female subjects and the lipid profile analyzed using an LC-MS-MS based metabololipidomics along with deuterium-labeled SPM as internal standards for quantitation [41]. We documented the presence of pro-inflammatory prostaglandins and the leukotriene B4. For the SPMs, the D-series resolvins (RvD1, RvD2, RvD5), protectin D1, and lipoxin A4, but neither the maresins nor E-series resolvins, were identified in these samples from healthy human subjects. The SPM biosynthesis pathway markers 17-HDHA, 14-HDHA, and 18-HEPE were also identified. These compounds could be bioactive themselves [42] or could suggest that both D- and E-series resolvins may be present in higher amounts locally than measured in the present study. The presence of pathway markers would also be consistent with the further metabolism of these bioactive resolvins to their oxo- and dehydro-resolvin products that were not profiled in the present study and are usually less or devoid of bioactivity. Thus, RvD1was present in human tears and available to regulate the function of the conjunctival goblet cells. There are two other studies on SPMs in tears that are in agreement with that of English et al [41]. Walter et al [43] found DHA, the ω3 fatty acid from which RvD1 is biosynthesized, in tears. RvD1 was not measured directly in this study. Masoudi S et al [44] found RvD1 in tears, but this was the only SPM analyzed.

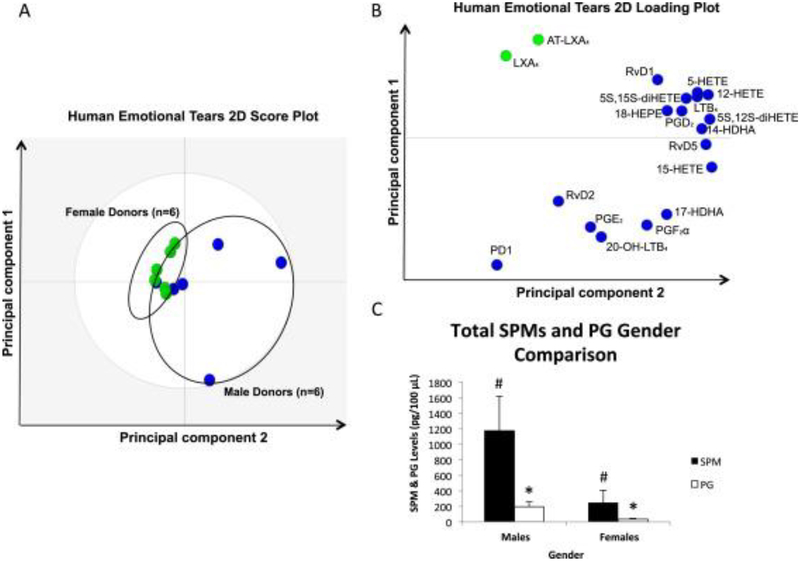

Surprisingly the lipid profile of male and female tears differed substantially [41]. Use of a principal component analysis demonstrated a gender difference in the SPMs in tears (Fig 5). The loading plot calculated from LC-MS-MS identified RvD1, RvD2, RvD5 and protectin D1 in male tears. In contrast LXA4 and aspirin-triggered LXA4 were detected in female tears. When the ratio of SPMs, 17-HDHA, and 18-HEPE versus the pro-inflammatory compounds PGE2 and PGF2a was compared between males and females, the ratio of SPMs to prostaglandins was much higher in males

Figure 5.

PCA and quantitative ratio by gender for LM-SPMs identified in human emotional tears. (A) 2-dimensional score plot of human emotional tear donors; blue circles (n=6) are representative of males, while green circles (n=6) are representative of females. Gray ellipse denotes 95% confidence interval. (B) 2-dimensional loading plot of LM-SPMs identified in human emotional tears; blue circles are those mediators associated with male donors & green circles are associated with female donors. (C) Bar graph depicting the ratio of total SPMs including RvD1, RvD2, RvD5, PD1, LXA4, AT-LXA4, 17-HDHA, and 18-HEPE compared to PGE2 and PGF2α (pg/100 μl), in males compared females (n=6 for each gender;#P <0.05 for male donors vs. female donors; *P<0.05, females vs. males). Reprinted from English et al. Identification and Profiling of Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators in Human Tears by Lipid Mediator Metabolomics. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 2017, 117:17–27.

4.0. Exogenous RvD1 Stimulates Conjunctival Goblet Cell Mucin Secretion Using Multiple Intracellular Signaling Pathways

4.1. RvD1 Stimulates of Goblet Cell Mucin Secretion-

As the major function of goblet cells is to secrete mucins, the action of RvD1 on mucin secretion was our focus. RvD1 stimulated human and rat conjunctival goblet cell high molecular weight glycoconjugate secretion (that includes mucin) [45, 46]. Secretion peaked at 1 hr and then declined over time for the next 3 hrs. RvD1 stimulated secretion by increasing the [Ca2+]i and activating ERK1/2 [45], similarly to the effect of cholinergic agonists and VIP [21] (Fig 6). RvD1 was effective in the range of 10−10 to 10−8 M, a much lower concentration range than for carbachol (10−6–10−4 M), but similar to VIP (10−11–10−7 M) [21, 23]. The RvD1 stimulation of secretion was blocked by chelating the intracellular Ca2+ with BAPTA and by inhibiting ERK1/2 activation with U0126 [47] substantiating the role of these signaling molecules in RvD1stimulation of goblet cell secretion.

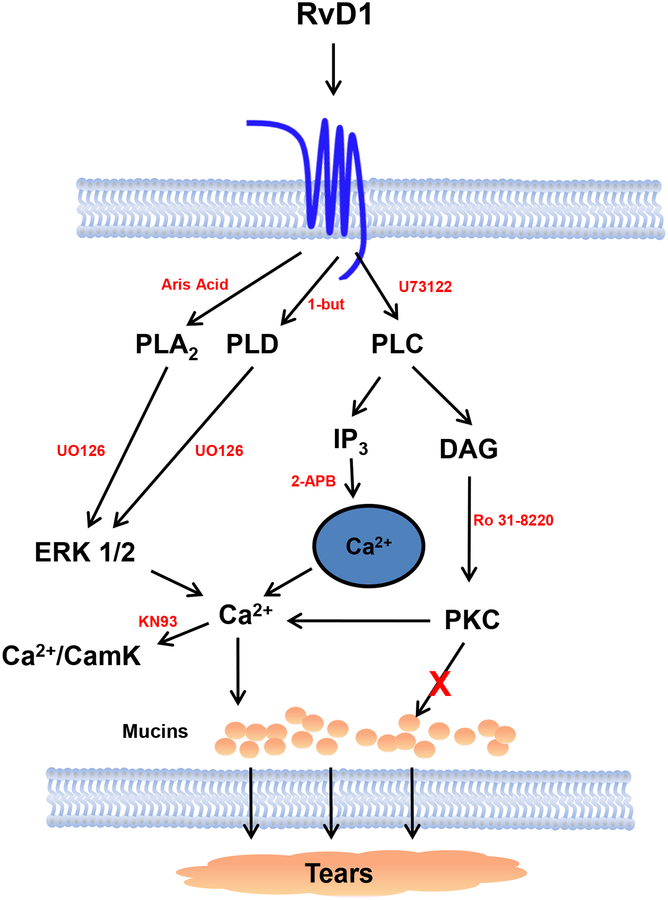

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of signaling pathways of RvD1 in conjunctival goblet cells. RvD1 binds to the ALX/FPR2 receptor and activates the signaling pathways of PLA2, PLC, and PLD. PLA2 and PLD are believed to activate ERK 1/2 to increase [Ca2+]i and Ca2+/CamK. PLC increases IP3 and DAG. IP3 releases Ca2+ while DAG activates PKC. Activation of these pathways leads to mucin secretion. PLA2- phospholipase A2; PLD- phospholipase D; PLC- phospholipase C; ERK 1/2- extracellular regulated kinase 1/2; IP3- inositol trisphosphate; DAG- diacylglycerol; Ca2+/CamK- calcium/calmodulin dependent kinase; PKC- protein kinase C. Inhibitors to pathways are shown in red. Reprinted from Lippestad et al Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science 2017, 58:4530–4544.

To induce goblet cell function the appropriate receptors must be present on conjunctival goblet cells. RvD1 uses the ALX/FPR2 receptor in rat and the GPR32/DRV1 receptor in human goblet cells. PCR, western blot and immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrated that the ALX/FPR2 receptor was present on rat conjunctival goblet cells in vivo and in culture [48, 49]. There is as yet no published report of GPR32/DRV1 on human goblet cells. There is also functional evidence for the presence of ALX/FPR2 receptor in rat conjunctival goblet cells. To address whether RvD1 uses the ALX/FPR2 receptor in the rat, both the ALX/FPR2 inhibitor N-Boc−Phe-Leu-Phe-Leu-Phe (BOC-2) and siRNA for ALX/FPR2 blocked RvD1 stimulated increase in [Ca2+]i [45, 47]. Functional evidence also demonstrates that RvD1 uses the GPR32/DRV1 receptor in human goblet cells. In human cells inhibition of ALX/FPR2 with its inhibitor BOC-2 does not block RvD1 stimulated increase in [Ca2+]i [49]. Furthermore, in desensitization experiments in human cells in which LXA4 and RvD1 were used sequentially, RvD1 does not desensitize LXA4 response [49]. This suggests use of separate receptors in human goblet cells. Thus RvD1 activates ALX/FPR2 in rat goblet cells and GPR32/DRV1 in human goblet cells. Further experiments using GPR32 siRNA in human goblet cells is warranted.

4.2. Cellular Signaling Pathways Activated by RvD1

4.2.1. Phospholipase C Pathway-

RvD1 activates a several specific intracellular signaling pathways to stimulate mucin secretion from rat goblet cells. One pathway is activation of phospholipase (PL) C that produces water soluble 1,4,5- inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and lipid soluble (membrane-bound) diacylglycerol (DAG) (Fig 6). IP3 binds to its receptors (IP3R) on the endoplasmic reticulum that releases Ca2+ from this intracellular store to increase the cytosolic [Ca2+] that stimulates exocytosis and mucin secretion. The DAG produced activates protein kinase (PK)C that phosphorylates as yet unidentified substrates to stimulate secretion. We used multiple techniques and inhibitors to determine if a PLC-dependent pathway plays a role in RvD1 stimulated goblet cell secretion [47]. First the active PLC inhibitor U73122 blocked RvD1 stimulated increase in [Ca2+]i and secretion as well as the increase caused by the positive control the cholinergic agonist carbachol. As expected, the inactive inhibitor U73343 did not block either the RvD1 or cholinergic agonist stimulation of secretion nor the cholinergic agonist induced increase in [Ca2+]i. Unfortunately the inactive inhibitor blocked the RvD1 induced increase in [Ca2+]i but was not as effective as the active analog. As the inactive inhibitor did not block three out of four responses, we concluded that RvD1 activates PLC in conjunctival goblet cells. To investigate IP3 interaction with its receptor to release Ca2+ from intracellular stores, an inhibitor of the IP3 receptor 2-aminoethyl diphenylborate (2-APB) was used. 2-APB blocked both the RvD1 stimulated increase in [Ca2+]i and secretion. A second method of determining the role of intracellular Ca2+ stores is the use of thapsigargin that blocks the re-uptake of Ca2+ into the stores, thereby depleting them of Ca2+. If RvD1 used intracellular Ca2+ stores, the addition of thapsigargin before RvD1 should prevent the increase in [Ca2+]i by RvD1. In goblet cells this did not occur [45]. However, depletion of extracellular Ca2+ blocked the RvD1stimulated elevation in [Ca2+]I supported the activation of Ca2+ influx by RvD1 [45].

The DAG arm of the PLC pathway was investigated by determining the role of PKC using the PKC inhibitor Ro 31–8220. The PKC inhibitor blocked the RvD1-stimulated increase in [Ca2+]i, but not in secretion. Activation of PKC may be important for the increase in [Ca2+]i, but not for secretion. There are multiple isoforms of PKC that are differentially activated by Ca2+ and diacylglycerol and can have opposing effects on a given process [50]. Thus investigation of the types of PKC isoforms present in goblet cells and inhibition of single isoforms would demonstrate more accurately whether PKC isoforms are involved in goblet cell secretion.

We concluded that RvD1 uses a PLC pathway to increase IP3 that releases Ca2+ from intracellular stores and causes an increase in the influx of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig 6). The resultant increase in the cytosolic [Ca2+]i stimulates secretion. The second arm of the PLC pathway production of DAG and activation of PKC is used to increase the [Ca2+]i, but whether PKC plays a role in secretion awaits investigation of the different PKC isoforms.

PLCγ is activated by EGF as PLCγ is an adapter molecule attached to the EGFR. PLCγ can be phosphorylated and activated upon stimulation and dimerization of the EGFR. We recently found that RvD1 uses a matrix metalloproteinase ADAM17 to release EGF by ectodomain shedding and activate the EGFR to increase [Ca2+]i and activate ERK1/2 to stimulate secretion [51]. Thus RvD1 could also activate PLCγ in addition to PLCβ to increase [Ca2+]i and stimulate secretion. Thus two different types of PLC are used by RvD1 to stimulate goblet cell mucin secretion.

4.2.2. Phospholipase D and A2-

The next two pathways investigated were activation of PLD and PLA2 [47] (Fig 6). These pathways were not investigated in as much detail as PLC. The role of PLD in RVD1 stimulated increase in [Ca2+]i and secretion was investigated using 1-butanol the active inhibitor of PLD and tert-butanol, its inactive control. The RvD1-induced increase in [Ca2+]i and stimulation of secretion was almost completely blocked by 1-butanol. The inactive control only partially blocked the increase in [Ca2+]i and did not block the stimulation of secretion. To study PLA2 aristolochic acid was used. Aristolochic acid blocked both the RvD1 caused increase in [Ca2+]i and stimulation of secretion. These results are consistent with RvD1 using both PLD and PLA2 to stimulation goblet cell secretion. Additional experiments should identify the components of these pathways.

4.2.3. Extracellular Regulated Kinase 1/2 Pathway-

RvD1 activates ERK1/2 to increase [Ca2+]i and stimulate secretion as shown by inhibition of both functions by the MEK inhibitor U0126 [45] (Fig 6). ERK1/2 could function as a component in several of the pathways studied. ERK1/2 could be activated by induction of the EGFR using the adapter proteins Ras, Raf, and MEK. ERK1/2 could also be downstream of PLD or PLA2.

4.3. Summary of Pathways Activated by RvD1-

RvD1 stimulates mucin secretion from conjunctival goblet cells by a receptor specific mechanism using ALX/FPR2 in rats and GPR32 in humans. RvD1 uses multiple signaling pathways including PLC, PLD, and PLA2 that each use specific signaling components to increase [Ca2+]i and could also activate ERK1/2 to stimulate secretion. In addition RvD1 transactivates the EGFR to increase [Ca2+]i, activate ERK1/2 and stimulate secretion. Endogenously produced RvD1 has multiple pathways available to stimulate conjunctival goblet cell mucin secretion to help maintain a normal mucous layer of tears.

5.0. Conclusion

The SPM RvD1, along neural regulation, is available to protect the ocular surface from dessicating stress, chemicals, temperature, allergens, particulate matter, and pathogens in the external environment. RvD1 is present in the tear film where it can access its receptors on the basolateral membranes of the goblet cells. RvD1 uses the ALX/FPR2 receptor in rat goblet cells and the GPR32 in human goblet cells. Activation of these receptors employs multiple intracellular pathways including PLC, PLD, PLA2 and the EGFR to increase [Ca2+]i and activate ERK1/2 to stimulate secretion. The main secretory product of the goblet cells is the large, gel-forming mucin MU5AC, which is released into the innermost layer of the tear film where it is protective of the ocular surface. This mucin can trap bacteria and particulate matter and remove them from the ocular surface via the nasal lacrimal drainage. RvD1 thus preserves ocular surface homeostasis and maintains this surface in a non-inflamed, normal physiologic state of an optimum amount of mucin secretion. RvD1 forms a second important mechanism along with activation of a neural reflex pathway to regulate goblet cell mucin secretion and protect the ocular surface in health.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Dartt is supported by the National Institutes of Health RO1 EY019470 and Dr. Serhan also thanks the NIH for support from 1P01GM095467 (CNS).

References

- 1.DelMonte DW, Kim T. Anatomy and physiology of the cornea. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. [Review]. 2011. March;37(3):588–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramphal R, McNiece MT, Polack FM. Adherence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the injured cornea: a step in the pathogenesis of corneal infections. Annals of ophthalmology. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. 1981. April;13(4):421–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Streilein JW. Ocular immune privilege: therapeutic opportunities from an experiment of nature. Nature reviews Immunology. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S. Review]. 2003. November;3(11):879–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dartt DA. Regulation of mucin and fluid secretion by conjunctival epithelial cells. Progress in retinal and eye research. [Review]. 2002. November;21(6):555–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gipson IK, Argueso P. Role of mucins in the function of the corneal and conjunctival epithelia. International review of cytology. [Review]. 2003;231:1–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mantelli F, Argueso P. Functions of ocular surface mucins in health and disease. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Review]. 2008. October;8(5):477–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mauris J, Mantelli F, Woodward AM, Cao Z, Bertozzi CR, Panjwani N, et al. Modulation of ocular surface glycocalyx barrier function by a galectin-3 N-terminal deletion mutant and membrane-anchored synthetic glycopolymers. PLoS One. [Research Support, American Recovery and Reinvestment Act Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. 2013;8(8):e72304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodges RR, Dartt DA. Tear film mucins: front line defenders of the ocular surface; comparison with airway and gastrointestinal tract mucins. Experimental eye research. [Comparative Study]. 2013. December;117:62–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knop E, Knop N. The role of eye-associated lymphoid tissue in corneal immune protection. Journal of anatomy. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Review]. 2005. March;206(3):271–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinoshita S, Ueta M. Innate immunity of the ocular surface. Japanese journal of ophthalmology. [Review]. 2010. May;54(3):194–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li D, Hodges RR, Bispo P, Gilmore MS, Gregory-Ksander M, Dartt DA. Neither non-toxigenic Staphylococcus aureus nor commensal S. epidermidi activates NLRP3 inflammasomes in human conjunctival goblet cells. BMJ open ophthalmology. 2017;2(1):e000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGilligan VE, Gregory-Ksander MS, Li D, Moore JE, Hodges RR, Gilmore MS, et al. Staphylococcus aureus activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in human and rat conjunctival goblet cells. PloS one. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.]. 2013;8(9):e74010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbosa FL, Xiao Y, Bian F, Coursey TG, Ko BY, Clevers H, et al. Goblet Cells Contribute to Ocular Surface Immune Tolerance-Implications for Dry Eye Disease. International journal of molecular sciences. 2017. May 5;18(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baudouin C, Rolando M, Benitez Del Castillo JM, Messmer EM, Figueiredo FC, Irkec M, et al. Reconsidering the central role of mucins in dry eye and ocular surface diseases. Progress in retinal and eye research. [Review]. 2018. November 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dartt DA, Masli S. Conjunctival epithelial and goblet cell function in chronic inflammation and ocular allergic inflammation. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Review]. 2014. October;14(5):464–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dartt DA, Kessler TL, Chung EH, Zieske JD. Vasoactive intestinal peptide-stimulated glycoconjugate secretion from conjunctival goblet cells. Experimental eye research. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. 1996. July;63(1):27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dartt DA, McCarthy DM, Mercer HJ, Kessler TL, Chung EH, Zieske JD. Localization of nerves adjacent to goblet cells in rat conjunctiva. Current eye research. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. 1995. November;14(11):993–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler TL, Mercer HJ, Zieske JD, McCarthy DM, Dartt DA. Stimulation of goblet cell mucous secretion by activation of nerves in rat conjunctiva. Current eye research. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. 1995. November;14(11):985–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Candia OA, Alvarez LJ. Fluid transport phenomena in ocular epithelia. Progress in retinal and eye research. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Review]. 2008. March;27(2):197–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Candia OA, Kong CW, Alvarez LJ. IBMX-elicited inhibition of water permeability in the isolated rabbit conjunctival epithelium. Experimental eye research. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. 2008. March;86(3):480–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rios JD, Zoukhri D, Rawe IM, Hodges RR, Zieske JD, Dartt DA. Immunolocalization of muscarinic and VIP receptor subtypes and their role in stimulating goblet cell secretion. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. 1999. May;40(6):1102–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanno H, Horikawa Y, Hodges RR, Zoukhri D, Shatos MA, Rios JD, et al. Cholinergic agonists transactivate EGFR and stimulate MAPK to induce goblet cell secretion. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2003. April;284(4):C988–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li D, Jiao J, Shatos MA, Hodges RR, Dartt DA. Effect of VIP on intracellular [Ca2+], extracellular regulated kinase 1/2, and secretion in cultured rat conjunctival goblet cells. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. 2013. April 23;54(4):2872–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickson L, Finlayson K. VPAC and PAC receptors: From ligands to function. Pharmacology & therapeutics. [Review]. 2009. March;121(3):294–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puro DG. Role of ion channels in the functional response of conjunctival goblet cells to dry eye. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2018. August 1;315(2):C236–C46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serhan CN. Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature. 2014. June 5;510(7503):92–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams RN, Bhattacherjee P, Eakins KE. Biosynthesis of lipoxygenase products by ocular tissues. Experimental eye research. 1983. March;36(3):397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulkarni PS, Srinivasan BD. Cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase pathways in anterior uvea and conjunctiva. Progress in clinical and biological research. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S. Review]. 1989;312:39–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kulkarni PS, Kaufman PL, Srinivasan BD. Eicosapentaenoic acid metabolism in cynomolgus and rhesus conjunctiva and eyelid. Journal of ocular pharmacology. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. 1987. Winter;3(4):349–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao Y, Su J, Zhang Y, Chan A, Sin JH, Wu D, et al. Dietary DHA amplifies LXA4 circuits in tissues and lymph node PMN and is protective in immune-driven dry eye disease. Mucosal immunology. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. 2018. November;11(6):1674–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao Y, Min K, Zhang Y, Su J, Greenwood M, Gronert K. Female-Specific Downregulation of Tissue Polymorphonuclear Neutrophils Drives Impaired Regulatory T Cell and Amplified Effector T Cell Responses in Autoimmune Dry Eye Disease. Journal of immunology. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. 2015. October 1;195(7):3086–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei J, Gronert K. The role of pro-resolving lipid mediators in ocular diseases. Molecular aspects of medicine. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Review]. 2017. December;58:37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serhan CN, Hamberg M, Samuelsson B. Lipoxins: novel series of biologically active compounds formed from arachidonic acid in human leukocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. 1984. September;81(17):5335–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barden AE, Mas E, Mori TA. n-3 Fatty acid supplementation and proresolving mediators of inflammation. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2016. February;27(1):26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiss GA, Troxler H, Klinke G, Rogler D, Braegger C, Hersberger M. High levels of anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving lipid mediators lipoxins and resolvins and declining docosahexaenoic acid levels in human milk during the first month of lactation. Lipids Health Dis. 2013. June 15;12:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arnardottir H, Orr SK, Dalli J, Serhan CN. Human milk proresolving mediators stimulate resolution of acute inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2016. May;9(3):757–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mas E, Croft KD, Zahra P, Barden A, Mori TA. Resolvins D1, D2, and other mediators of self-limited resolution of inflammation in human blood following n-3 fatty acid supplementation. Clin Chem. 2012. October;58(10):1476–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colas RA, Shinohara M, Dalli J, Chiang N, Serhan CN. Identification and signature profiles for pro-resolving and inflammatory lipid mediators in human tissue. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014. July 1;307(1):C39–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu M, Wang X, Hjorth E, Colas RA, Schroeder L, Granholm AC, et al. Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators Improve Neuronal Survival and Increase Abeta42 Phagocytosis. Mol Neurobiol. 2016. May;53(4):2733–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mukherjee PK, Marcheselli VL, Serhan CN, Bazan NG. Neuroprotectin D1: a docosahexaenoic acid-derived docosatriene protects human retinal pigment epithelial cells from oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004. June 1;101(22):8491–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.English JT, Norris PC, Hodges RR, Dartt DA, Serhan CN. Identification and Profiling of Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators in Human Tears by Lipid Mediator Metabolomics. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2017. February;117:17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lima-Garcia JF, Dutra RC, da Silva K, Motta EM, Campos MM, Calixto JB. The precursor of resolvin D series and aspirin-triggered resolvin D1 display anti-hyperalgesic properties in adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2011. September;164(2):278–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walter SD, Gronert K, McClellan AL, Levitt RC, Sarantopoulos KD, Galor A. omega-3 Tear Film Lipids Correlate With Clinical Measures of Dry Eye. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.]. 2016. May 1;57(6):2472–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Masoudi S, Zhao Z, Willcox M. Relation between Ocular Comfort, Arachidonic Acid Mediators, and Histamine. Current eye research. [Clinical Trial]. 2017. June;42(6):822–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li D, Hodges RR, Jiao J, Carozza RB, Shatos MA, Chiang N, et al. Resolvin D1 and aspirin-triggered resolvin D1 regulate histamine-stimulated conjunctival goblet cell secretion. Mucosal Immunol. 2013. November;6(6):1119–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dartt DA, Hodges RR, Li D, Shatos MA, Lashkari K, Serhan CN. Conjunctival goblet cell secretion stimulated by leukotrienes is reduced by resolvins D1 and E1 to promote resolution of inflammation. J Immunol. 2011. April 1;186(7):4455–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lippestad M, Hodges RR, Utheim TP, Serhan CN, Dartt DA. Resolvin D1 Increases Mucin Secretion in Cultured Rat Conjunctival Goblet Cells via Multiple Signaling Pathways. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017. September 1;58(11):4530–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hodges RR, Li D, Shatos MA, Bair JA, Lippestad M, Serhan CN, et al. Lipoxin A4 activates ALX/FPR2 receptor to regulate conjunctival goblet cell secretion. Mucosal Immunol. 2017. January;10(1):46–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hodges RR, Li D, Shatos MA, Serhan CN, Dartt DA. Lipoxin A4 Counter-regulates Histamine-stimulated Glycoconjugate Secretion in Conjunctival Goblet Cells. Sci Rep 2016. November 8;6:36124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zoukhri D, Hodges RR, Sergheraert C, Dartt DA. Protein kinase C isoforms differentially control lacrimal gland functions. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;438:181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaye R, Botten N, Lippestad M, Li D, Hodges RR, Utheim TP, et al. Resolvin D1, but not resolvin E1, transactivates the epidermal growth factor receptor to increase intracellular calcium and glycoconjugate secretion in rat and human conjunctival goblet cells. Exp Eye Res. 2018. December 1;180:53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]