Abstract

Melanosis is major problem of crustaceans during their rigor mortis storage. This study for the first time was designed to optimize the formula of preservatives to maintain the color feature of Pacific white shrimp using response surface methodology. A three-factors-three-levels Box-Behnken design was applied to evaluate the effect of chitosan, citric acid and l-cysteine on color features (L*, a*, b* and ΔE) of Pacific white shrimp. It was found that the increasing rate of ΔE was retarded by the higher concentrations of chitosan, citric acid and l-cysteine in a certain range. The optimal formula for inhibiting the increase of ΔE was 1.36% chitosan, 0.47% citric acid and 0.31% l-cysteine. Under the optimal pretreated conditions, the predicted ΔE of shrimp after 8 days of storage was 14.59, close to the measured values (14.49). These results indicated that the optimal combined preservatives could retard the decrease of lightness and the aggregation of ΔE and melanosis effectively, and might be a potential application for retarding melanosis and extending shelf life of Pacific white shrimp.

Keywords: Shrimp, Color, Response surface methodology, Chitosan, Citric acid, l-cysteine

Introduction

Pacific white shrimp is widely consumed over the world due to its rich nutrient and taste (Nirmal and Benjakul, 2012). However, postharvest shrimp is perishable during transportation and consumption as a result of microbial spoilage. In addition, melanosis occurs simultaneously which is produced in the reaction of oxidation of phenols by polyphenoloxidase (PPO) (Nirmal and Benjakul, 2011a). Although, melanosis (the black spots on shrimp carapace) is not harmful to human health, it seriously impacts the consumers’ favor and commercial value of shrimp (Mu et al., 2012).

Among most techniques for inhibition of melanosis, using additives is the most convenient and effective way. Sulfite-based agents have been used in food industry to inhibit the enzymatic browning that caused by PPO, which would cause asthma and was limited in addition amount (Hardisson et al., 2002). 4-Hexylresorcinol has been found to be an alternative on shrimp (Galvao et al., 2017). However, nowadays customers are aware of food safety and health risk associated with synthesis chemical agents and they prefer natural additives (Encarnacion et al., 2011). Some plant extracts such as green tea extract and cinnamaldehyde have been used to improve the quality of shrimp (Mu et al., 2012; Nirmal and Benjakul, 2011a). To find safe and healthy preservatives which can inhibit melanosis is still a great challenge. Combined preservatives can be used at lower concentration than a single preservative to obtain stronger inhibition effect on melanosis (Montero et al., 2006). Chitosan, citric acid and l-cysteine have been successfully applied in the fruit foodstuff to inhibit the enzymatic browning caused by PPO (Chiabrando and Giacalone, 2012; Guerrero-Beltrán et al., 2005; İyidoǧan and Bayındırlı, 2004; Xiao et al., 2010; Zhang and Quantick, 1997).

Color is one of important quality of shrimp which influences consumers’ acceptation. Researchers have been studied on the shrimp color under different processing or storage condition via colorimeter or computer vision system with CIE L* a* b* units (Hosseinpour et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2011; Qian et al., 2014). Color (CIE L* a* b* units) measurement is more objective and easier to find the distinction between samples compared with sensory evaluation. In some other foodstuffs, color measurement has also been used for evaluating the enzymatic browning (İyidoǧan and Bayındırlı, 2004; Özoğlu and Bayındırlı, 2002). Thus color measurement could be applied to estimate the effect of color feature on shrimp preserved by combined preservative during storage.

Due to the properties of shrimp such as perishable flesh and high rates of melanosis, it will be beneficial to investigate effectiveness of combined preservatives on melanosis. This study is aimed at investigating the optimal formula of combined preservative consisting of chitosan, citric acid and l-cysteine via response surface methodology and its effect of color variation on Pacific white shrimp during cold storage.

Materials and methods

Materials

Chitosan, citric acid and l-cysteine were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Shrimp sample preparation

Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) were purchased from Luchaogang Port in Shanghai, China. Shrimp were kept alive in plastic bags fulfilled with oxygen and transported to lab. The alive shrimp with an average weight of 13 ± 2 g were washed in flowing water and kept in ice less than 2 h before treated with preservatives. The combined preservatives consisting of chitosan, citric acid and l-cysteine were blended using ultrasound for 15 min to obtain homogeneous solutions. Then, the shrimp were immersed in combined preservatives for 5 min at a ratio of 1:2 (weight of shrimp to volume of solution). Shrimp treated with distilled water were used as control. After immersing, shrimp were drained for 10 min. Then, shrimp were packed in polyethylene plastic bags and stored at 4 °C. The shelf life of shrimp treated with combined preservation was evaluated as 8 days based on melanosis evaluation in preliminary experiments.

Experimental design

Box-Behnken design was used to evaluate the effect of combined preservatives on total color change of shrimp. It was supposed that there was a mathematical function between the response value and three independent coded variables according to İyidoǧan and Bayındırlı (2004) as follows:

| 1 |

where Y is the predicted response, b0 is the constant coefficient, b1, b2 and b3 are the linear coefficients, b12, b13 and b23 are cross product coefficients, b11, b22 and b33 are quadratic coefficients, X1, X2 and X3 represent the content of chitosan, citric acid and l-cysteine, respectively.

Concentrations of preservatives at − 1, 0 and + 1 coded variable levels are given in Table 1. The levels of independent variables were selected based on values obtained in preliminary experiments (Xiong et al., 2014).

Table 1.

Concentration of combined preservations studied using responsible surface design in terms of actual and coded factors

| Levels | Concentration (w/v) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan(CH) % | Citric acid(CA) % | l-cysteine(CY) % | |

| − 1 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.05 |

| 0 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.275 |

| 1 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 0.5 |

Color determination

Lightness (L*), redness (a*) and yellowness (b*) were determined by Konica colorimeter (Konica CR-10, Osaka, Japan). L* presents color from darkness (−) to lightness (+), a* presents color from green (−) to red (+), b* presents blue (−) to yellow (+). Samples were measured on two sides of the cephalothorax according to Qian et al. (2014). Total color change (ΔE) was described according to İyidoǧan and Bayındırlı (2004) as following:

| 2 |

where L*i, a*i, b*i were measured on day i (0, 2, 4, 6 and 8), L*0, a*0, b*iwere measured on day 0.

Melanosis evaluation

Melanosis evaluation was carried out by trained panelists according to Nirmal and Benjakul (2011b). When melanosis score drops to 5 which indicated shrimp was neither like nor dislike by panelists, it was considered as the end of storage.

Statistical analysis

All determinations were carried out in 8 replicates. For all statistics, SAS V8.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and Excel (2010) were used. Three dimension curves were developed by Design Expert V8.0.6 (Statease Inc., Minneapolis, USA).

Results and discussion

Model fitting

The color feature of fresh shrimp was translucent with slight green and yellow. During storage, the color of shrimp changed gradually and melanosis appeared on the shell. ΔE was influenced by the three factors individually or interactively. The experimental results obtained on day 8 as function of different concentration of combined preservatives are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Box-behnken experimental design and results

| Number | CH % | CA % | CY % | ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | X2 | X3 | Y | |

| 1 | − 1 | 0 | − 1 | 16.11 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14.81 |

| 3 | 1 | − 1 | 0 | 16.03 |

| 4 | − 1 | − 1 | 0 | 16.09 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14.12 |

| 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 16.74 |

| 7 | 0 | − 1 | 1 | 16.10 |

| 8 | − 1 | 0 | 1 | 15.29 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14.16 |

| 10 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 16.83 |

| 11 | 0 | 1 | − 1 | 17.30 |

| 12 | − 1 | 1 | 0 | 16.55 |

| 13 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 16.98 |

| 14 | 1 | 0 | − 1 | 17.72 |

| 15 | 0 | − 1 | − 1 | 17.72 |

Table 3 displays the ANOVA results of the response surface quadratic models. ANOVA results demonstrated that the response surface quadratic models were significant for ΔE (p < 0.05). The models presented high correlation with ΔE, as R2 was higher than 0.90. The increasing concentrations of chitosan, citric acid and l-cysteine used in the formula were helpful to inhibit the increase of ΔE. The linear terms (b2 and b3) were significant (p < 0.05), and the quadratic terms (b22 and b33) were very significant (p < 0.01), but the interactive terms b12, b13 and b23 were not significant. Therefore, the individual effect was more significant than the interactive effect. The b2 and b3 were more significant than b1, and the b22 and b33 were more significant than b11, indicating that citric acid and l-cysteine played a major role in restrain total color change rather than chitosan according to the t test. In comparison with carvacrol, chitosan also showed less effectiveness (Wang et al., 2018).

Table 3.

Coefficient estimates and ANOVA regression parameters of the response surface

| Coefficients | ΔE |

|---|---|

| b0 | 26.46***(3.11) |

| b1 | − 8.09(3.50) |

| b2 | − 15.77*(4.23) |

| b3 | − 18.94*(5.09) |

| b12 | 0.57(1.76) |

| b13 | − 0.34(2.35) |

| b23 | 4.83(3.92) |

| b11 | 2.91*(1.10) |

| b22 | 14.31**(3.06) |

| b33 | 27.20**(5.44) |

| Lack of fit (p) | 0.31 |

| R2 | 0.93 |

| Total model (p) | 0.02 |

Values of coefficients are given as estimate value (standard error)

*Significant at p ≤ 0.05, **significant at p ≤ 0.01, ***significant at p ≤ 0.001

Based on the result of response surface analysis, terms which were not significant were removed to optimize predict models through nonlinear regression analysis. The coefficients after optimization were shown in Table 4. Model was significant for ΔE (p < 0.01).

Table 4.

Optimal predict models based on response surface analysis

| Parameters | Model |

|---|---|

| ΔE | 19.695 − 13.034 X2 − 16.484 X3 + 0.308 X21 + 13.759 X22 + 26.208 X23 |

Optional formula of combined preservatives

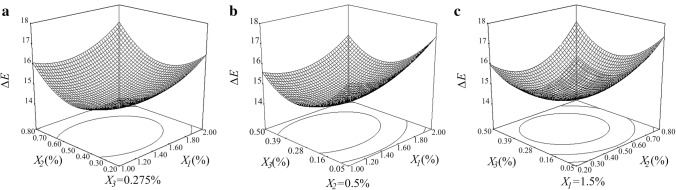

Figure 1 is an example of response surface of ΔE. The values of ΔE decreased with the increasing content of chitosan, citric acid and l-cysteine within certain range. Thus, chitosan, citric acid and l-cysteine could inhibit total color change. Stationary points were found in this response surface model. According to canonical analysis, the optimal formula for inhibiting ΔE is 1.36% chitosan, 0.47% citric acid and 0.31% l-cysteine. The stationary point of ΔE was 14.25. The predicted value of ΔE on day 8 in the optimal models was 14.59. To examine the accuracy of the predicted models, the optimal formula of ΔE which was calculated from L*, a* and b* was carried out for further study under the same condition.

Fig. 1.

Response surfaces illustrating effect of chitosan, citric acid and l-cysteine on ΔE. X1: chitosan; X2: citric acid; X3: l-cysteine

Color change during storage

Variation of L*, a*, b*, ΔE and melanosis of shrimp treated with combined preservative mentioned above during storage were shown in Table 5. On day 0, no melanosis was observed and the lightness value of fresh shrimp was about 39.78. Shrimp treated combined preservative showed higher lightness due to the membrane formed by the preservative.

Table 5.

Color change of shrimp during cold storage

| Time (d) | L* | a* | b* | ΔE | Melanosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cont | CP | Cont | CP | Cont | CP | Cont | CP | Cont | CP | |

| 0 | 39.78 ± 3.09aA | 45.08 ± 7.47aA | − 0.07 ± 1.08aB | − 0.26 ± − 0.66aC | 9.22 ± 1.54aA | 6.46 ± 2.64bB | 0.00 ± 0.00aC | 0.00 ± 0.00aD | 0.00 ± 0.00aD | 0.00 ± 0.00aC |

| 2 | 32.40 ± 1.61bB | 41.12 ± 0.92aA | 0.43 ± 0.38aAB | 1.55 ± 1.07aBC | 5.85 ± 1.92aAB | 8.47 ± 2.13aB | 8.32 ± 1.23aB | 3.06 ± 0.06bC | 3.20 ± 0.45aC | 0.90 ± 0.42bC |

| 4 | 21.77 ± 1.71bC | 28.68 ± 0.81aB | 0.89 ± 0.31aAB | 1.02 ± 1.88aBC | 4.56 ± 0.58aB | 7.87 ± 4.12aB | 18.63 ± 1.78aA | 11.82 ± 0.87bB | 5.00 ± 1.41aB | 2.80 ± 1.30bB |

| 6 | 20.82 ± 0.63bC | 28.81 ± 1.55aB | 1.52 ± 0.89aA | 2.15 ± 2.05aB | 5.79 ± 4.39aAB | 9.59 ± 3.39aB | 19.65 ± 1.27aA | 11.67 ± 1.28bB | 5.22 ± 1.02aB | 3.66 ± 1.33bB |

| 8 | 20.53 ± 1.10bC | 28.07 ± 2.50aB | 1.17 ± 0.45bAB | 4.83 ± 1.56aA | 5.23 ± 1.97bB | 15.82 ± 1.37aA | 19.75 ± 1.42aA | 14.49 ± 1.56bA | 8.60 ± 0.89aA | 5.00 ± 1.00bA |

Cont control; CP combined preservative

Different letters in the same row within the same item indicate the significant differences (P < 0.05)

Different capital letters in the same column within the same treatment indicate the significant difference (P < 0.05). Values are mean ± standard deviation

During the storage, L* of both control and combined preservative group decreased due to the increase of melanosis. The combined preservative inhibited the declination of L* and increase of melanosis. PPO accelerated melanosis action during storage leading to appearance of black spots on the surface of shrimp. Shrimp in control group was considered unacceptable on day 4 as the score of melanosis was about 5. The combined preservative could restrain the PPO activity or act with intermediates to retard melanosis. Chitosan is considered to be an oxygen barrier, which can form a layer of member on the surface of food to isolate the O2 to avoid the enzymatic browning. Besides, due to the excellent chelating ability of chitosan (Gamage and Shahidi, 2007), it may be able to chelate the cupric ions which are the active center of PPO resulting inactive the enzyme. Sulfhydryl-containing amino acid, l-cysteine, can act with intermediates of melanosis action to form stable and colorless compounds (İyidoǧan and Bayındırlı, 2004). Citric acid was also reported to inhibit the development of melanosis alone or with other preservatives, due to its ion-chelating ability and pH-reducing activity (Nirmal and Benjakul, 2012). Melanosis could also be intensified by compounds secreted by spoilage bacteria (Qian et al., 2014). The combined preservative restrained melanosis acceleration by inhibiting the growth of bacteria on shrimp at some extent.

Redness (a*) increased throughout the storage, which was intensified by the preservative. Shrimp turned to red due to denaturation of carotenoprotein in shrimp muscle, which may free the red astaxanthin esters (Li et al., 2013).

For b*, control group showed downtrend, but the group treated with combined preservative increased. A similar phenomenon discovered when shrimp treated with 5 g kg−1 cinnamaldehyde, the value of b* increased from 7.85 to 10.21, but decreased later (Mu et al., 2012). The formation of light color compounds from l-cysteine or citric acid chelating ions should be responsible for this phenomenon (Montero et al., 2006).

Total color change (ΔE) was inhibited by the combined preservative. ΔE, which was a reflection of variation of L*, a*, b*, had high correlation with melanosis (p < 0.0001). Although the combined preservative intensified redness and yellowness, it passivated PPO and inhibited melanosis which enhanced lightness and decreased total color change.

In conclusion, chitosan, citric acid and l-cysteine could inhibit color change of shrimp during storage at 4 °C. Response surface methodology was carried out to optimize the formula to inhibit total color change. Prediction model of ΔE was effective to forecast ΔE on day 8. The optimal formula for inhibiting ΔE was 1.36% chitosan, 0.47% citric acid and 0.31% l-cysteine. This combined preservative was efficient to restrain the decrease of lightness and increase of total color change and melanosis.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China [31571914, 31501551], the National “13th Five-Year” Key Research and Development Program for Science and Technology Support [2016YFD0400106], Key science and technology project on agriculture-developing of Shanghai [No. 1-1(2016), Shanghai Agric. Sci.], Foundation for platform developing of Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai [16DZ2280300] and Startup Foundation for Doctors of Shanghai Ocean University [A2-2006-00-200360].

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yun-Fang Qian and Qing Xiong are joint lead authors of this paper.

Contributor Information

Yun-Fang Qian, Email: yfqian@shou.edu.cn, Email: yunfangqian@126.com.

Qing Xiong, Email: 444180528@qq.com.

Sheng-Ping Yang, Email: spyang@shou.edu.cn.

Jing Xie, Phone: +86 21 619 00 385, Email: jxie@shou.edu.cn.

References

- Chiabrando V, Giacalone G. Effect of antibrowning agents on color and related enzymes in fresh-cut apples during cold storage. J. Food Process Preserv. 2012;36:133–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4549.2011.00561.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Encarnacion AB, Fagutao F, Shozen KI, Hirono I, Ohshima T. Biochemical intervention of ergothioneine-rich edible mushroom (Flammulina velutipes) extract inhibits melanosis in crab (Chionoecetes japonicus) Food Chem. 2011;127:1594–1599. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.02.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galvao JA, Vazquez-Sanchez D, Yokoyama VA, Savay-Da-Silva LK, Canniatti Brazaca SG, Oetterer M. Effect of 4-hexylresorcinol and sodium metabisulphite on spoilage and melanosis inhibition in Xiphopenaeus kroyeri shrimps. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017;41:e12943. doi: 10.1111/jfpp.12943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gamage A, Shahidi F. Use of chitosan for the removal of metal ion contaminants and proteins from water. Food Chem. 2007;104:989–996. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Beltrán JA, Swanson BG, Barbosa-Cánovas GV. Inhibition of polyphenoloxidase in mango puree with 4-hexylresorcinol, cysteine and ascorbic acid. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2005;38:625–630. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2004.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hardisson A., Rubio C., Frías I., Rodríguez I., Reguera J.I. Content of sulphite in frozen prawns and shrimps. Food Control. 2002;13(4-5):275–279. doi: 10.1016/S0956-7135(02)00022-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinpour S, Rafiee S, Mohtasebi SS, Aghbashlo M. Application of computer vision technique for on-line monitoring of shrimp color changes during drying. J. Food Eng. 2013;115:99–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2012.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- İyidoǧan NF, Bayındırlı A. Effect of l-cysteine, kojic acid and 4-hexylresorcinol combination on inhibition of enzymatic browning in Amasya apple juice. J. Food Eng. 2004;62:299–304. doi: 10.1016/S0260-8774(03)00243-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M, Liu S, Wang Y. Effects of antimicrobial coating from catfish skin gelatin on quality and shelf life of fresh white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) J. Food Sci. 2011;76:M204–M209. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Liu S, Cline D, Chen S, Wang Y, Bell LN. Chemical treatments for reducing the yellow discoloration of channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) fillets. J. Food Sci. 2013;78:S1609–S1613. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero P, Martínez-Álvarez O, Zamorano JP, Alique R, Gómez-Guillén MC. Melanosis inhibition and 4-hexylresorcinol residual levels in deepwater pink shrimp (Parapenaeus longirostris) following various treatments. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006;223:16–21. doi: 10.1007/s00217-005-0080-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mu H, Chen H, Fang X, Mao J, Gao H. Effect of cinnamaldehyde on melanosis and spoilage of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) during storage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012;92:2177–2182. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirmal NP, Benjakul S. Retardation of quality changes of Pacific white shrimp by green tea extract treatment and modified atmosphere packaging during refrigerated storage. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011;149:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirmal NP, Benjakul S. Use of tea extracts for inhibition of polyphenoloxidase and retardation of quality loss of Pacific white shrimp during iced storage. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2011;44:924–932. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2010.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nirmal NP, Benjakul S. Effect of green tea extract in combination with ascorbic acid on the retardation of melanosis and quality changes of Pacific white shrimp during iced storage. Food Bioprocess Tech. 2012;5:2941–2951. doi: 10.1007/s11947-010-0483-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Özoğlu H, Bayındırlı A. Inhibition of enzymic browning in cloudy apple juice with selected antibrowning agents. Food Control. 2002;13:213–221. doi: 10.1016/S0956-7135(02)00011-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y-F, Xie J, Yang S-P, Wu W-H, Xiong Q, Gao Z-L. In vivo study of spoilage bacteria on polyphenoloxidase activity and melanosis of modified atmosphere packaged Pacific white shrimp. Food Chem. 2014;155:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Lei J, Ma J, Yuan G, Sun H. Effect of chitosan-carvacrol coating on the quality of Pacific white shrimp during iced storage as affected by caprylic acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;106:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.07.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C, Zhu L, Luo W, Song X, Deng Y. Combined action of pure oxygen pretreatment and chitosan coating incorporated with rosemary extracts on the quality of fresh-cut pears. Food Chem. 2010;121:1003–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.01.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Q, Xie J, Gao ZL, Shi JB, Zhang LP, Qian YF. Effects of natural preservatives on shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) during cold storage. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2014;35:270–274. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Donglin, Quantick Peter C. Effects of chitosan coating on enzymatic browning and decay during postharvest storage of litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) fruit. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 1997;12(2):195–202. doi: 10.1016/S0925-5214(97)00057-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]