Abstract

Purpose:

To determine the effect of aging methods on the fracture toughness of a conventional Bis-GMA based resin composite (Filtek Supreme), an ormocer-based resin composite (Admira), and an experimental hydrophobic Oxirane/Acrylate interpenetrating network resin System (OASys)-based composite.

Methods:

A 25 × 5 × 2.8 mm stainless-steel mold with 2.5 mm single edge center notch, following ASTM standards [E399–90], was used to fabricate 135 specimens (n=15) of the composite materials and randomly distributed into groups. For the baseline group, specimens were fabricated and then tested after 24-hours storage in water. For the biofilm challenge, specimens were randomly placed in a six well tissue culture plate and kept at 37°C with bacterial growth media (Brain Heart Infusion (BHI); Streptococcus mutans) changed daily for 15 days. For the water storage challenge, specimens were kept in 5 ml of deionized distilled autoclaved water for 30 days at 37°C. μCT evaluation by scanning the specimens was performed before and after the proposed challenge. Fracture toughness (KIc) testing was carried out following the challenges.

Results:

μCT surface area and volume analyses showed no significant changes regardless of the materials tested or the challenge. Filtek and Admira fracture toughness was significantly lower after the biofilm and water storage challenges. OASys mean fracture toughness values after water aging were significantly higher than that of baseline. Toughness values for OASys composites after biofilm aging were not statistically different when compared to either water or baseline values.

Conclusion:

The fracture toughness of BisGMA and ormocer-based dental resin composites significantly decreased under water and bacterial biofilm assault. However, such degradation in fracture toughness was not visible in OASys-based composites.

Clinical significance:

Current commercial dental composites are affected by the oral environment, which might contribute to the long-term performance of these materials.

INTRODUCTION

Recent resin-based dental composite materials have improved in regard to their physical and mechanical properties becoming both patients’ and clinicians’ first choice for restorative dentistry. As such, over 800 million dental composite restorations were placed in 2015. However, a meta-analysis shows that by 2025, 32 million of these restorations will be replaced or repaired due to fracture [1]. Therefore, the mechanical and physical properties of direct restorative filling materials require further improvement and new materials should be evaluated before widespread clinical use.

In particular, it has been shown that dental resin composite suffers from degradation when in contact with the oral environment [2]. Water absorption into the composite can contribute to leaching of unreacted monomer and chemicals, and degradation can lead to leaching of resin byproducts [3–5]. These phenomena can lead to defective margins and loss of retention [6, 7]. Beyond concerns with clinical durability, leached materials affects biocompatibility [8, 9]. In-vitro studies have used water for different amount of time to promote a challenge environment for the specimens.

To exasperate the situation, in-vitro studies have shown that resin monomers that have leached into the oral cavity can alter the expression of virulence factors and promote the growth of cariogenic bacteria [10]. Additionally, biofilms form more preferably on resin composites as compared to other restorative materials [11, 12].

Thus, Bis-GMA-alternative monomer compositions have been introduced to improve durability. One alternative is the ormocer-based dental composite material (Organic-Modified ceramic), which consists of inorganic-organic co-polymers. Ormocer-based composite materials were proposed to have less polymerization shrinkage than conventional Bis-GMA-based composites due to its larger three dimensionally cross-linked ceramic polysiloxane monomer [13]. Cavalcante et al. [14] also showed that pure ormocer composites (no added acrylate-based monomers) better maintained surface integrity in vitro after seven days of water storage and had the least hardness change after seven days of ethanol storage as compared to a partial ormocer composite and a bis-GMA-based resin composite. However, a recent systematic review has shown that ormocer composite materials have a higher global failure rate and poorer long-term clinical behavior than conventional resin composites [15].

More recently, an experimental resin material based on an Oxirane/Acrylate interpenetrating network resin System (OASys) was reported to have increased hydrophobicity and decreased polymerization shrinkage stress. Both of these properties were due to the inherent properties of oxirane and its ring-opening polymerization mechanism [16]. The addition of a fluorinated acrylate to an OASys-based composite further increased contact angles to great than 115° [17].

Fracture toughness and flexural strength have been proposed as mechanical properties that have some correlation with the clinical performance of composite resin restorations. IIlie et al (2012) showed that the fracture toughness of sixty-nine direct tooth-colored materials measured after 24 hours in distilled water (baseline) varied according to each material [18]. In addition, Lin and Drummond [19] observed that a 50/50 mixture of ethanol and water was the most detrimental aging media to a nano-filled, hybrid, and micro-filled dental composites after cyclic loading. However, no study has evaluated the effect of a biofilm challenge on the fracture toughness of dental composite materials.

Thus, the objective of this work is to determine the effect of water and bacterial (Streptococcus mutans) biofilm challenge on Bis-GMA-based (Filtek Supreme Ultra), ormocer-based (Admira Fusion) and OASys-based dental composite degradation and fracture toughness (KIc).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples preparation

A stainless-steel mold of 25 × 5 × 2.8 mm with a 2.5 mm single edge center notch, following ASTM standards (E399–90 [20]) was used to fabricate specimens using three different dental composite materials (n=45) [Table 1]. Specimens were light cured with a polywave curing light (Valo light-curing system, Ultradent Products Inc., USA) on both sides to deliver a 20 J/cm2 radiant exposure. The specimens were polished with aluminum sandpaper 600 −1200 grit-size (Buehler, Illinois, USA) for 10 seconds on each side, then carefully examined to ensure that no surface defects were present.

Table 1:

Materials used in this study, manufacturer, composition, and LOT numbers

| Material | Manufacturer | Matrix | Fillers | Fillers by weight/ volume %wt/ %vol | Lot Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admira Fusion (A) | VOCO, Cuxhaven, Germany | Ormocer resin multi-functional urethane thioetheroligo(meth)acrylate alkoxysilanes | SiO2, Ba-Al-B-Si-glass | 77%/54% | 1651310 1628174 1734497 1623194 1633336 |

| Filtek Supreme Ultra (F) | 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA | BisGMA, BisEMA, UDMA, TEGDMA | ZrO2/SiO2 cluster SiO2 nanofiller | 78.5%/63% | N820171 N853944 N870984 |

| OASys (OA) | UTHSCSA | - 25% DPHA - 25% Epalloy 8370 -20% UDMA -30% PFOEA |

- 0.7 μm barium glass filler - acrylate silanated |

70%/NI |

Abbreviations: NI= no information available; Bis-GMA = bisphenol A-glycidyl methacrylate; BisEMA = ethoxylated bisphenol-A dimethacrylate; UDMA= urethane dimethacrylate; TEGDMA= triethylene glycol dimethacrylate; DPHA= dipentaerythritol hexa/pentaacrylate; PFOEA = perfluorooctylethyl acrylate

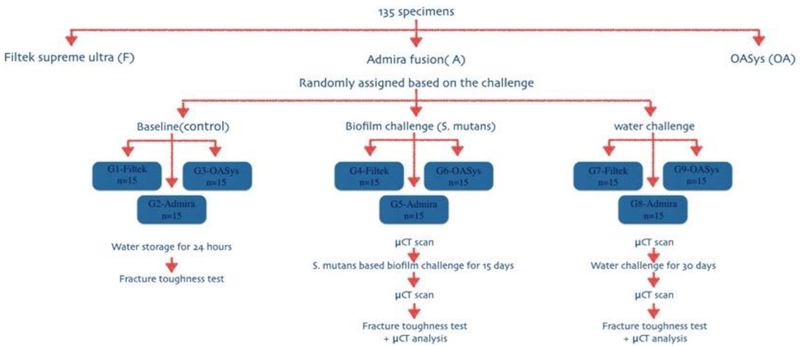

Specimens were randomly and equally assigned (n=15) to nine groups after 24 hours in water [Figure 1] as follows: G1: Bis-GMA-based dental composite (Filtek) baseline (control); G2: Ormocer-based dental composite (Admira) baseline (control); G3: Experimental oxirane/acrylate-based dental composite (OASys) baseline (control); G4: Filtek with 15-day biofilm challenge; G5: Admira with 15-day biofilm challenge; G6: OASys with 15-day biofilm challenge; G7: Filtek with 30-day water storage; G8: Admira with 30-day water storage; G9: OASys with 30-day water storage.

Figure 1:

Flowchart of the experimental study design

Biofilm challenge

Streptococcus mutans (ATCC, 215175, American Type Culture Collection) was revived from frozen stocks on Trypticase Soy Agar (TSA) with 5% sheep’s blood for 24 hours. Colonies from the blood agar plates were inoculated into Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth using a sterile Q-tip. Specimens were sterilized and placed in six wells tissue culture plates (Falcon 353046, Corning Inc.) and kept at 37° C. BHI medium was then added and supplemented with 0.5% sucrose for 24 hours to promote the establishment of a biofilm on the composite sticks. The (BHI) growth medium was changed every day for the 15 days [21].

Water challenge

Specimens were randomly placed in tissue culture plates (Falcon 353046, Corning Inc.) with 5 ml deionized distilled autoclaved water and kept at 37°C. The autoclaved water was changed once every week for 30 days.

MicroCT evaluation

After 24 hours in water, specimens (n=3) from each group were randomly selected for baseline surface area and volumetric μCT evaluation (Xradia Versa 3D XRM-520, Zeiss, Germany). Specimens were then submitted to the proposed challenges then scans were repeated. The x-ray settings were as follows: voltage (kV): 90, power (watts): 8, rotation: 360, projections: 1601, exposure time (seconds): 1.25, objective: 0.4x, reconstructed pixel size: 25 microns, beam hardening correction, reconstruction binning: 1. These settings were based on composite density. The constructed 3D models of the pre/post challenge were analyzed using Object Research System (ORS) software (ORS, Canada) for surface area and volumetric analyses. The software reconstructs the 3D model using a specific region of interest (ROI) for each composite material based on the material density.

Fracture toughness

Fracture toughness testing was carried out using a universal test machine (Zwick Roell Group, Germany) with a load cell capacity of 500 N. Single edge notch (SENB) three-point bending was performed with a 20 mm span at a cross-head speed of 0.5 mm/min. The width, thickness, and the notch length of each specimen were carefully measured and verified using a digital caliper.

The mode I critical stress intensity factor (KIc) was calculated using the following equation:

Where KIc is mode I crack opening, P is load at fracture (N), L is the span length in mm, W is the specimen width in mm, B is the specimen thickness in mm, and a is the notch length in mm [20].

Hydrophobicity (Contact Angle Measurements)

Contact angles were determined with a VCA1000 video contact angle instrument (AST Products, Billerica, MA). Three images of ~0.05 mL drops (one on the center, two on opposite edges) of deionized water were captured by the camera 15 seconds after placement of water droplets on the specimens and the angles determined.

Statistical analysis

Two-Way ANOVA was carried out to evaluate the effect of the material type and the challenge on the fracture toughness (KIc). A statistical significant interaction between material and challenge was observed (p = 0.007). A one-way ANOVA was then used and followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test. One-way Repeated Measure ANOVA was used to evaluate the surface area and volume before and after aging. Levene’s test of Equality confirmed homogeneity for the surface area and volume measurements. All tests were at 5% level of significance.

RESULTS

Fracture Toughness results

Filtek Supreme composites had significantly higher baseline KIc (1.37±0.29 MPa m1/2) than Admira and OASys composites (0.88±0.52 MPa m1/2 and 0.575±0.28 MPa m1/2, respectively, p<0.05) [Table 2]. The same pattern was observed after the biofilm challenge. Filtek and Admira KIc significantly decreased following biofilm and water challenges. On the contrary, OASys KIc significantly increased following water storage (0.795 MPa m1/2) as compared to the baseline measurement (0.575MPa m1/2, p<0.05), while no significant difference in KIc was found between the OASys biofilm group and either baseline or water groups.

Table 2:

Mean (SD) of the fracture toughness KIc results (MPa m1/2). (Different uppercase letters in columns and lowercase letter in rows represent statistical significant differences)

| n=15 | Baseline (control) mean(SD) (MPa m1/2) | Biofilm (15 days) mean(SD) | Water (30 days) mean(SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| OASys | 0.575(.28) Ba | 0.69(.16) Bab | 0.795(.08) Ab |

| Filtek | 1.37(.29) Aa | 0.97(.18) Ab | 0.95(.33) Ab |

| Admira | 0.88(.52) Ba | 0.50(.24) Bb | 0.56(.22) Bb |

Surface area and Volume changes

OASys composites had significant lower volumes than Admira and Filtek composites [Tables 3,4]. However, no significant change was observed in the surface area and volume after aging regardless of the material (p>0.05).

Table 3:

Volumes of composites before and after aging (Different uppercase letters in columns and lowercase letter in rows represent statistical significant differences)

| Water | Biofilm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Materials n=3 |

Mean(std)(×1011 μm3) Before |

Mean(std) (×1011 μm3) After |

Mean(std) (×1011 μm3) Before |

Mean(std)(×1011 μm3) After |

| OASys | 3.08(0.06)Aa | 3.09(0.07)Aa | 3.146(0.01)Aa | 3.15(0.01)Aa |

| Filtek | 3.19(0.05)Bb | 3.23(0.05)Bb | 3.23(0.03)Bb | 3.26(0.03)Bb |

| Admira | 3.15(0.03)Bb | 3.17(0.03)Bb | 3.26(0.06)Bb | 3.27(0.06)Bb |

Table 4:

Surface areas of composites before and after aging (Different uppercase letters in columns and lowercase letter in rows represent statistical significant differences)

| Water | Biofilm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Materials n=3 |

Mean(std) (×108 μm2) Before |

Mean(std) (×108 μm2) After |

Mean(std) (×108 μm2) Before |

Mean(std) (×108 μm2) After |

| OASys | 5.08(0.06)Aa | 5.1(0.08)Aa | 4.83(0.04)Aa | 4.84(0.06)Aa |

| Filtek | 4.42(0.03)Bb | 4.57(0.09)Bb | 4.46(0.04)Bb | 4.45(0.01)Bb |

| Admira | 4.41(0.05)Bb | 4.46(0.07)Bb | 4.41(0.1)Bb | 4.48(0.12)Bb |

Hydrophobicity

An average and standard deviation of 108.2(9.2) was observed for OASys-based composites, showing a high degree of hydrophobicity. Lower average values were observed for Filtek [79.9 (11.9)] and Admira groups [59.39 (12.6)].

DISCUSSION

Degradation is a major factor in the shortened longevity of dental composite restoratives [2, 22]. Recent advancements in dental materials technology to overcome this challenge includes the development of ormocer-based composites and an experimental oxirane/acrylate interpenetrating polymer resin (OASys)-based composites [16, 17]. Fracture toughness (KIc) has been shown to be a good predictor of a clinical performance for direct restorative materials that are used in stress-bearing areas [1, 2].

The results of this study revealed that the type of resin composite material had a significant effect on the fracture toughness KIc (p<0.05). At baseline, Filtek Supreme composite had a significant higher KIc than Admira and OASys composites. Other studies have demonstrated similar results in regards to Filtek and Admira [18, 23–25]. The mechanical properties, including fracture toughness, of ormocer based composites has been reported to be comparable to the conventional hybrid and nanohybrid when stored in water for 24h [15, 18]. However, differences in the amount and type of filler in the composite matrix can be significant contributors to the differences in KIc of these materials [26, 27]. Filtek has a higher filler content compared to that of Admira and OASys. In addition, it could be hypothesized that the nanoclusters present in the Filtek Supreme might contribute to crack deflection [28]. On the other hand, Admira has larger glass fillers that might elicit less resistance to crack propagation [29]. Although OASys composite material had voids, most likely due to it being an experimental composite without a delivery device, its fracture toughness was similar to Admira.

Following water storage, the KIc of both Filtek and Admira composite materials significantly decreased. Some studies have reported no change in KIc values after water storage [25] while others have shown significant reductions [30, 31], [4]. Dental composites tend to slowly absorb water, some of which accumulates between the inorganic fillers and matrix. This process could take up to 2 months until equilibration [31, 32]. The accumulated water molecules separate the chains of the polymer network resulting in unpredictable polymer expansion and chemical degradation [33], which can affect the mechanical properties of composites.

OASys composites had a significant increase in KIc after being aged in water. Ilie et al. (2009)[34] has stated that silorane based resin composites (a monomer that contains siloxane and oxirane) showed good mechanical properties compared to Bis-GMA- based resin composite and was mechanically stable following 5000 cycles of thermocycling and four weeks of water, artificial saliva, or alcohol storage [34]. It is possible that the hydrophobic surface of the OASys composite as demonstrated by the contact angle measurement prevented water inhibition into the composite and the slower oxirane polymerization continued, showing higher fracture toughness.

An array of aging methods can be used to evaluate mechanical and physical properties of dental materials. Studies have shown that water and artificial saliva had similar effect on the mechanical properties of resin composites after cyclic fatigue [19, 22, 34]. The main degradation mechanism of composite materials aged in water and/or artificial water is possibly due to hydrolytic degradation of the filler-matrix interface. When using water as the environmental challenge, hydrolytic degradation is the only anticipated mechanism.[3, 22] In our study, both 15 days of biofilm challenge and 30 days of water challenge reduced the fracture toughness of Filtek and Admira resin composites but did not reduce the fracture toughness of OASys composites. This could be related to the high degree of hydrophobicity of the experimental composite.

Although the biofilm challenge has high technical demands compared to water storage, it includes a potential enzymatic activity known to be responsible for degradation of dental composite materials[35, 36]. Streptococcus mutans biofilm is known to be associated with dental plaque and dental caries [37, 38]. Lactic acid and enzymes, such as esterase, that are produced by bacteria, such as Streptococcus mutans, can hamper the resin composite via hydrolysis and chemical breakdown of ester bond in resin matrix and affect its surface roughness and physical stability [11, 12]. In this study, for Filtek and Admira, the effect of biofilm aging was similar to that of water storage aging with a significant reduction of KIc. This is in agreement with Zhou et al’s [39] report that Streptococcus mutans biofilm aging produced a significant flexural strength reduction in resin composites. Interestingly, there was no such reduction in fracture strength for OASys composites after bacterial biofilm aging, further lending evidence that the hydrophobic surface may have prevented or reduced degradation by preventing water and enzyme imbibition.

Several studies have confirmed the accuracy and validity of using μCT to evaluate the volumetric change of resin composite materials [40–44]. The small increase in volume of the specimens were mostly attributed to hygroscopic expansion caused by water sorption. Water molecules are slowly absorbed between the inorganic particles and organic matrix [3]. This accumulated water might interact with the monomer through hydrogen bond, allowing for further accumulation of water molecules inside the polymer. Moreover, resin composites that contained Bis-GMA/TEGDMA co-polymers have up to 3.3% increase in volume due to hygroscopic expansion [45]. Boaro et al.[46] has shown that the same Filtek Supreme resin composite has a high sorption rate compared to seven other resin composite materials and silorane based resin composite (a monomer that contains siloxane and oxirane) had a low sorption rate. The surface area and volume change results from this work, however, did not show any significant increases for any of the materials.

Conclusion

Within the limitations of this study, both biofilm aging and water storage significantly reduced the fracture toughness of the commercially available dental composite materials - Filtek Supreme Ultra and Admira Fusion. However, biofilm aging did not affect the fracture toughness of the OASys dental composites and water storage actually increased the fracture toughness. All tested dental composite materials showed no significant surface area or volume changes after the environmental challenges as measured using μCT. The use of a hydrophobic OASys-based dental composite shows promise for increasing restoration longevity while further studies are warranted.

Funding:

This work was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health [NIH/NIDCR Grant U01 DE23778]

Ethical approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of Interest: Hamad Algamaiah declares that he has no conflict of interest. Robert Danso declares that he has no conflict of interest. Jeffrey Banas declares that he has no conflict of interest. Steve R. Armstrong declares that he has no conflict of interest. Kyumin Whang declares that he has no conflict of interest. H. Ralph Rawls declares that he has no conflict of interest. Erica C. Teixeira declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Informed consent: For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

References

- Heintze SD, Ilie N, Hickel R, Reis A, Loguercio A and Rousson V (2017) Laboratory mechanical parameters of composite resins and their relation to fractures and wear in clinical trials-A systematic review. Dent Mater 33:e101–e114. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2016.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferracane JL (2013) Resin-based composite performance: are there some things we can’t predict? Dent Mater 29:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martos J, Osinaga PWR, Oliveira E, Castro LAS (2003) Hydrolytic Degradation of Composite Resins: Effects on the Microhardness. Materials Research 6:99–604. [Google Scholar]

- Arikawa H, Kuwahata H, Seki H, Kanie T, Fujii K and Inoue K (1995) Deterioration of mechanical properties of composite resins. Dent Mater J 14:78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaderhane L, Nascimento FD, Breschi L, Mazzoni A, Tersariol IL, Geraldeli S, Tezvergil-Mutluay A, Carrilho M, Carvalho RM, Tay FR and Pashley DH (2013) Strategies to prevent hydrolytic degradation of the hybrid layer-A review. Dent Mater 29:999–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferracane JL and Condon JR (1999) In vitro evaluation of the marginal degradation of dental composites under simulated occlusal loading. Dent Mater 15:262–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suiter EA, Watson LE, Tantbirojn D, Lou JS and Versluis A (2016) Effective Expansion: Balance between Shrinkage and Hygroscopic Expansion. J Dent Res 95:543–9. doi: 10.1177/0022034516633450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferracane JL (1994) Elution of leachable components from composites. J Oral Rehabil 21:441–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferracane JL and Condon JR (1990) Rate of elution of leachable components from composite. Dent Mater 6:282–7. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(05)80012-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busscher HJ, Rinastiti M, Siswomihardjo W and van der Mei HC (2010) Biofilm formation on dental restorative and implant materials. J Dent Res 89:657–65. doi: 10.1177/0022034510368644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucio SB, Carvalho FG, Sobrinho LC, Sinhoreti MA and Puppin-Rontani RM (2008) The influence of 30-day-old Streptococcus mutans biofilm on the surface of esthetic restorative materials--an in vitro study. J Dent 36:833–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyth N, Bahir R, Matalon S, Domb AJ and Weiss EI (2008) Streptococcus mutans biofilm changes surface-topography of resin composites. Dent Mater 24:732–6. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2007.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra S, Singh A, Gupta M and Chadha V (2012) Ormocer: An aesthetic direct restorative material; An in vitro study comparing the marginal sealing ability of organically modified ceramics and a hybrid composite using an ormocer-based bonding agent and a conventional fifth-generation bonding agent. Contemp Clin Dent 3:48–53. doi: 10.4103/0976-237x.94546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante LM, Schneider LF, Silikas N and Watts DC (2011) Surface integrity of solvent-challenged ormocer-matrix composite. Dent Mater 27:173–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsarrat P, Garnier S, Vergnes JN, Nasr K, Grosgogeat B and Joniot S (2017) Survival of directly placed ormocer-based restorative materials: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Dent Mater 33:e212–e220. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2017.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawls HRJAD, Norling BK, Whang K (2015) Restorative Resin Compositions and Methods of Use, WIPO Patent WO20151557329A1.

- Danso RMA, Oldham M, Whang K, Wendt S, Johnston A, Ralph HR (2017) A Hydrophobic Composite Based on an Oxirane/Acrylate Interpenetrating Network. J Dent Res 96(A), #3014. [Google Scholar]

- Ilie N, Hickel R, Valceanu AS and Huth KC (2012) Fracture toughness of dental restorative materials. Clin Oral Investig 16:489–98. doi: 10.1007/s00784-011-0525-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L and Drummond JL (2010) Cyclic loading of notched dental composite specimens. Dent Mater 26:207. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E399–90 A (1997) ASTM E399–90(1997), Standard Test Method for Plane-Strain Fracture Toughness of Metallic Materials,. Book title., http://www.astm.org/cgi-bin/resolver.cgi?E399-90(1997)

- Jain A (2016) A biofilm-based aging model for testing degradation of dental adhesive microtensile bond strength. University of Iowa, Iowa Research Online. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond JL (2008) Degradation, fatigue, and failure of resin dental composite materials. J Dent Res 87:710–9. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mese A, Ea Palamara J, Bagheri R, Fani M and Burrow MF (2016) Fracture toughness of seven resin composites evaluated by three methods of mode I fracture toughness (KIc). Dent Mater J 35:893–899. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2016-140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomaidis S, Kakaboura A, Mueller WD and Zinelis S (2013) Mechanical properties of contemporary composite resins and their interrelations. Dent Mater 29:e132–41. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sookhakiyan M, Tavana S, Azarnia Y and Bagheri R (2017) Fracture Toughness of Nanohybrid and Hybrid Composites Stored Wet and Dry up to 60 Days. J Dent Biomater 4:341–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbishari H, Silikas N and Satterthwaite J (2012) Filler size of resin-composites, percentage of voids and fracture toughness: is there a correlation? Dent Mater J 31:523–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, Khera SC, Vargas MA and Qian F (2008) Fracture toughness comparison of six resin composites. Dent Mater 24:418–25. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2007.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohbauer U, Belli R and Ferracane JL (2013) Factors involved in mechanical fatigue degradation of dental resin composites. J Dent Res 92:584–91. doi: 10.1177/0022034513490734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apel E, Deubener J, Bernard A, Holand M, Muller R, Kappert H, Rheinberger V and Holand W (2008) Phenomena and mechanisms of crack propagation in glass-ceramics. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 1:313–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2007.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijelic-Donova J, Garoushi S, Lassila LV, Keulemans F and Vallittu PK (2016) Mechanical and structural characterization of discontinuous fiber-reinforced dental resin composite. J Dent 52:70–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2016.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferracane JL and Marker VA (1992) Solvent degradation and reduced fracture toughness in aged composites. J Dent Res 71:13–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345920710010101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musanje L, Shu M and Darvell BW (2001) Water sorption and mechanical behaviour of cosmetic direct restorative materials in artificial saliva. Dent Mater 17:394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Sunbul H, Silikas N and Watts DC (2015) Resin-based composites show similar kinetic profiles for dimensional change and recovery with solvent storage. Dent Mater 31:e201–17. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2015.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilie N and Hickel R (2009) Macro-, micro- and nano-mechanical investigations on silorane and methacrylate-based composites. Dent Mater 25:810–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2009.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaviz Y, Finer Y and Santerre JP (2014) Biodegradation of resin composites and adhesives by oral bacteria and saliva: a rationale for new material designs that consider the clinical environment and treatment challenges. Dent Mater 30:16–32. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.08.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedeljkovic I, De Munck J, Ungureanu AA, Slomka V, Bartic C, Vananroye A, Clasen C, Teughels W, Van Meerbeek B and Van Landuyt KL (2017) Biofilm-induced changes to the composite surface. J Dent 63:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2017.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahnel S, Muhlbauer G, Hoffmann J, Ionescu A, Burgers R, Rosentritt M, Handel G and Haberlein I (2012) Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus biofilm formation and metabolic activity on dental materials. Acta Odontol Scand 70:114–21. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2011.600703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napimoga MH, Hofling JF, Klein MI, Kamiya RU and Goncalves RB (2005) Tansmission, diversity and virulence factors of Sreptococcus mutans genotypes. J Oral Sci 47:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Wang S, Peng X, Hu Y, Ren B, Li M, Hao L, Feng M, Cheng L and Zhou X (2018) Effects of water and microbial-based aging on the performance of three dental restorative materials. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 80:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2018.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain MV and Xue J (2009) State of the art of Micro-CT applications in dental research. Int J Oral Sci 1:177–88. doi: 10.4248/ijos09031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa T, Sadr A and Tagami J (2017) microCT-3D visualization analysis of resin composite polymerization and dye penetration test of composite adaptation. Dent Mater J. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2016-323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata R, Clozza E, Giannini M, Farrokhmanesh E, Janal M, Tovar N, Bonfante EA and Coelho PG (2015) Shrinkage assessment of low shrinkage composites using micro-computed tomography. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 103:798–806. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiger DN, Sun J, Schumacher GE and Lin-Gibson S (2009) Evaluation of dental composite shrinkage and leakage in extracted teeth using X-ray microcomputed tomography. Dent Mater 25:1213–20. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2009.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prager M, Pierce M, Atria PJ, Sampaio C, Caceres E, Wolff M, Giannini M and Hirata R (2018) Assessment of cuspal deflection and volumetric shrinkage of different bulk fill composites using non-contact phase microscopy and micro-computed tomography. Dent Mater J. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2017-136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderholm KJ (1984) Water sorption in a bis(GMA)/TEGDMA resin. J Biomed Mater Res 18:271–9. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820180304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boaro LC, Goncalves F, Guimaraes TC, Ferracane JL, Pfeifer CS and Braga RR (2013) Sorption, solubility, shrinkage and mechanical properties of “low-shrinkage” commercial resin composites. Dent Mater 29:398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]