Summary

The Gram‐negative soil‐borne bacterium Ralstonia solanacearum first infects roots of host plants and then invades xylem vessels. In xylem vessels, the bacteria grow vigorously and produce exopolysaccharides (EPSs) to cause a wilt symptom on host plants. The EPSs are thus the main virulence factors of R. solanacearum. The strain OE1‐1 of R. solanacearum produces methyl 3‐hydroxymyristate as a quorum‐sensing (QS) signal, and senses this QS signal, activating QS. The QS‐activated LysR‐type transcriptional regulator PhcA induces the production of virulence‐related metabolites including ralfuranone and the major EPS, EPS I. To elucidate the function of EPS I, the transcriptomes of R. solanacearum strains were analysed using RNA sequencing technology. The expression of 97.2% of the positively QS‐regulated genes was down‐regulated in the epsB‐deleted mutant ΔepsB, which lost its EPS I productivity. Furthermore, expression of 98.0% of the negatively QS‐regulated genes was up‐regulated in ΔepsB. The deficiency to produce EPS I led to a significantly suppressed ralfuranone productivity and significantly enhanced swimming motility, which are suppressed by QS, but did not affect the expression levels of phcA and phcB, which encode a methyltransferase required for methyl 3‐hydroxymyristate production. Overall, QS‐dependently produced EPS I may be associated with the feedback loop of QS.

Keywords: major exopolysaccharide EPS I, quorum sensing, Ralstonia solanacearum

The Gram‐negative bacterium Ralstonia solanacearum infects more than 250 plant species worldwide and causes bacterial wilt (Mansfield et al., 2012). The soil‐borne R. solanacearum first invades plant roots through wounds or natural openings, colonizes the root intercellular spaces and then invades xylem vessels (Araud‐Razou et al., 1998; Hikichi et al., 2017; Vasse et al., 1995). Ralstonia solanacearum produces and extracellularly secretes nitrogen‐ and carbohydrate‐rich exopolysaccharides (EPSs) dependent on quorum sensing, which consists of phc regulatory elements (phc QS), indicating that EPSs are abundantly produced at high cell densities (McGarvey et al., 1999; Schell, 2000). In xylem vessels, R. solanacearum grows vigorously and produces copious EPSs. EPS productivity‐deficient mutants of R. solanacearum show significantly reduced virulence levels (Denny and Baek, 1991). It is thus thought that the EPSs are main virulence factors.

Bacterial cells release QS signals, which are small diffusible signal molecules, and monitor QS signals to track changes in their cell numbers (Rutherford and Bassler, 2012). Ralstonia solancearum strains AW1 and K60, and OE1‐1 and GMI1000, produce methyl 3‐hydroxypalmitate and methyl 3‐hydroxymyristate (3‐OH MAME), respectively, as QS signals with the methyltransferase PhcB (Flavier et al., 1997; Kai et al., 2015). These QS signals are sensed through the histidine kinase PhcS sensor, leading to the activation of phc QS (Fig. S1, see Supporting information). The LysR‐type transcriptional regulator PhcA, activated through phc QS, plays a central role among global virulence regulators, including major EPS I (Genin and Denny, 2012).

PhcA, when activated by phc QS, also induces the expression of ralA, encoding ralfuranone synthase, which induces the production of a precursor, ralfuranone I, for the aryl‐furanone secondary metabolites, ralfuranones (Fig. S1). Ralfuranone B is produced by an extracellular non‐enzymatic conversion from ralfuranone I. The enzymatic oxidation of ralfuranone B produces ralfuranones J and K. The benzaldehyde is non‐enzymatically eliminated from ralfuranone B, producing ralfuranone A (Kai et al., 2014, 2016; Pauly et al., 2013). Interestingly, ralfuranones also affect the function of PhcA in positively feedback‐regulating phc QS (Hikichi et al., 2017; Mori et al., 2018b). Furthermore, functional PhcA induces the expression of lecM, encoding the lectin LecM (Meng et al., 2015; Mori et al., 2016). LecM affects the extracellular stability of 3‐OH MAME, contributing to the phc QS signalling pathway (Hayashi et al., 2019).

EPSs cloak bacterial surface features, which plants can recognize, to protect R. solanacearum from plant antimicrobial defences (D’Haeze and Holsters, 2004). Although EPS production is metabolically expensive for R. solanacearum, EPSs are involved in the bacterial survival under desiccation conditions in soil (Denny, 1995; McGarvey et al., 1999; Peyraud et al., 2016; Saile et al., 1997). Furthermore, R. solanacearum that has infected xylem vessels produces copious amounts of EPS I, which is essential for wilting because it restricts water flow through xylem vessels, killing the hosts (Genin and Denny, 2012). Interestingly, bacterial wilt‐resistant tomato plants specifically recognize EPS I from R. solanacearum (Milling et al., 2011), demonstrating that EPS I also functions as a signal for plant–R. solanacearum interactions. However, the role of EPS I in the intracellular and intercellular signalling of R. solanacearum cells associated with the bacterial virulence has remained unknown.

The eps operon containing epsB, of which expression is positively regulated by the phc QS, is involved in the production and extracellular secretion of EPS I (Genin and Denny, 2012). In this study, to elucidate the functions of EPS I, transcriptome profiles of R. solanacearum strains, including the epsB‐deletion mutant ΔepsB that lost its EPS I productivity (Mori et al., 2018a), were first examined using RNA sequencing (RNA‐Seq) technology. The functions of EPS I in phc QS‐dependent R. solanacearum virulence‐related phenotypes were then analysed.

We first analysed the transcriptomes of R. solanacearum strains, the ΔepsB mutant, the phcB‐deletion mutant ΔphcB (Kai et al., 2015), the phcA‐deletion mutant ΔphcA (Mori et al., 2016) and the strain OE1‐1 (Kanda et al., 2003), which were cultured in one‐quarter‐strength M63 medium (1/4 M63; Cohen and Rickenberg, 1956) until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was 0.3. RNA sample preparation and sequencing were performed as previously described (Hayashi et al., 2019). RNA‐Seq data mapping and analyses were performed with an Illumina HiSeq 2000 system (Illumina, Madison, WI, USA) according to the protocols of Hayashi et al. (2019). For each strain, we conducted two biologically independent experiments. After RNA‐Seq using a final 400 ng RNA yield, the two experiments produced 46.5 and 43.9, 45.3 and 44.4, 45.4 and 44.9, and 47.0 and 46.0 million 100‐bp paired‐end reads from the strains ΔepsB, ΔphcB, ΔphcA and OE1‐1, respectively. An iterative alignment per experiment successfully mapped 42.5 and 43.5, 42.1 and 44.1, 44.7 and 44.5, and 41.8 and 43.8 million 100‐bp paired‐end reads from the strains ΔepsB, ΔphcB, ΔphcA and OE1‐1, respectively, to the reference genome of R. solanacearum strain GMI1000 (Salanoubat et al., 2002). We identified 4501 protein‐coding transcripts from the RNA‐Seq reads of strain OE1‐1 by mapping to the GMI1000 genome (Table S1, see Supporting information). The read counts of each sample as fragments per kilobase of open reading frame per million fragments mapped values were calculated with Cufflinks v. 2.2.1 (http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/cufflinks/). The normalized gene expression levels of strains ΔepsB, ΔphcB and ΔphcA were compared with that of strain OE1‐1 to detect differentially expressed transcripts. Genes were considered differentially expressed if they exhibited expression level fold‐changes ≤−4 or ≥4 [log2(fold changes) ≤−2 or ≥2].

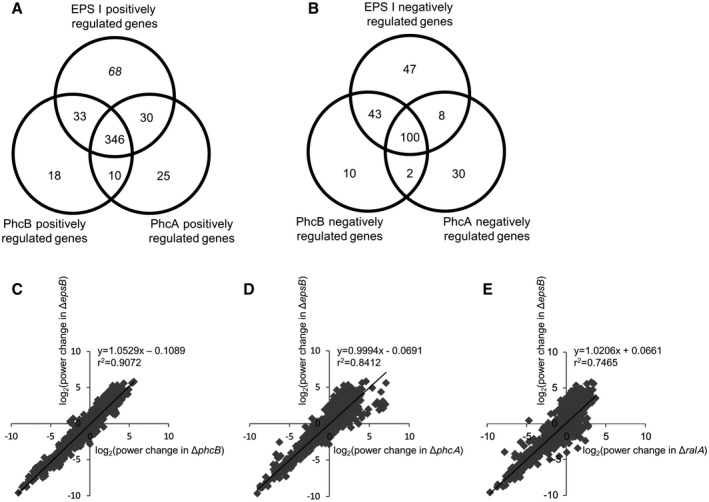

We observed significantly lower expression levels of 411 genes (positively PhcA‐regulated genes) in ΔphcA than in strain OE1‐1 (Fig. 1A and Table S1). The expression levels of 407 genes (positively PhcB‐regulated genes) were significantly lower in ΔphcB. Among the positively PhcB‐regulated genes, 356 genes were also included in the positively PhcA‐regulated genes, suggesting that these genes are the positively phc QS‐regulated genes. The expression levels of 140 genes (negatively PhcA‐regulated genes) in ΔphcA were significantly greater than in strain OE1‐1 (Fig. 1B and Table S1). The expression levels of 155 genes (negatively PhcB‐regulated genes) in ΔphcB were significantly greater than in strain OE1‐1. Among the negatively PhcB‐regulated genes, 100 genes were included in the negatively PhcA‐regulated genes, suggesting that these genes are the negatively phc QS‐regulated genes. We detected 477 genes (EPS I‐positively regulated genes) and 198 genes (EPS I‐negatively regulated genes) that were expressed at significantly lower and higher levels, respectively, in ΔepsB than in OE1‐1 (Fig. 1A and Table S1). Among the positively EPS I‐regulated genes, 346 genes were included in the positively phc QS‐regulated genes, including not only ralfuranone production‐related genes (i.e. ralA and ralD), lecM, plant cell wall degradation enzyme genes (i.e. cbhA, egl and pme), the effector gene RSc1723 for a protein secreted through the type III secretion system (T3SS) and type VI secretion system‐related genes, but also EPS I productivity‐related genes (Fig. 1A, Tables [Link], [Link] and [Link], [Link], see Supporting information). Furthermore, among the negatively EPS I‐regulated genes, 100 genes were included in the negatively phc QS‐regulated genes, including chemotaxis‐related genes, flagellar motility‐related genes, five T3SS‐related genes and six effector genes secreted through the T3SS (Fig. 1B, Tables [Link], [Link] and [Link], [Link], see Supporting information). Conversely, we detected no significant differences between ΔepsB and OE1‐1 in the expression levels of phcB and phcA (Table S1). The expression levels of all the transcripts in ΔepsB were positively correlated with those in ΔphcB (Fig. 1C) and ΔphcA (Fig. 1D). Although the expression levels of all the transcripts in ΔepsB were positively correlated with those in the ralfuranone productivity‐deficient mutant (ΔralA; Kai et al., 2014), the coefficients of correlation were lower than those between ΔepsB and the phc QS‐deficient mutants (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

The numbers of genes that exhibited expression level fold‐changes ≤−4 (A) or ≥4 (B) in the Ralstonia solanacearum phcB‐deletion mutant (ΔphcB), phcA‐deletion mutant (ΔphcA) and epsB‐deletion mutant (ΔepsB), which lost major EPS I productivity, relative to their expression levels in strain OE1‐1, and correlations in gene expression level changes between ΔphcB and ΔepsB of R. solanacearum strains (C), between ΔphcA and ΔepsB of R. solanacearum strains (D), and between the ralfuranone productivity‐deficient mutant (ΔralA) and ΔepsB of R. solanacearum strains (E). The fragments per kilobase of open reading frame per million fragments mapped values for R. solanacearum strains OE1‐1, ΔphcB, ΔphcA, ΔralA and ΔepsB were normalized prior to analyses of differentially expressed genes. Data for the genes affected by the deletion of ralA are from Mori et al. (2018b).

We then created a native epsB‐expressing complemented ΔepsB mutant (epsB‐comp). An 803‐bp DNA fragment (cepsB‐1) of OE1‐1 genomic DNA was amplified by PCR using cepsB‐1‐FW (5′‐TGTCG AAGTT CATGT CCCAC ACC‐3′) and cepsB‐1‐RV (5′‐ATGCG ACCAC CATGA TCGGA TGTCC TTGCG TC‐3′) as primers. A 2322‐bp DNA fragment (cepsB‐2) of OE1‐1 genomic DNA was amplified by PCR using the primers cepsB‐2‐FW (5′‐GGACG CATTC ATGAC GCAGA ACCTC TCTCA GC‐3′) and cepsB‐2‐RV (5′‐CATTC CCCTC CTGAT TCGCA ATC‐3′). A 3104‐bp DNA fragment was then amplified by PCR using cepsB‐1 and cepsB‐2 as templates and cepsB‐1‐FW and cepsB‐2‐RV as primers. The 3104‐bp DNA fragment was ligated into pMD20 (Takara Bio, Otsu, Japan) to create pMD20cepsB (Table 1). A KpnI‐ and SpeI‐digested 3.2‐kb fragment of pMD20cepsB was ligated into a KpnI‐ and SpeI‐digested pUC18‐mini‐Tn7‐Gm (Choi et al., 2006) to create pCepsB (Table 1). pCepsB was electroporated into ΔepsB with pTNS2 (Choi et al., 2006), and the gentamycin‐resistant strain epsB‐comp was created.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Relevant characteristics | Source | |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids used for cloning | ||

| pMD20 | pUC19 derivative, Ampr | Takara Bio |

| pUC18‐mini‐Tn7‐Gm | Gmr | Choi et al. (2006) |

| pTNS2 | Helper plasmid carrying T7 transposase gene | Choi et al. (2006) |

| pMD20cepsB | pMD20 derivative carrying a 3.1‐kbp fragment containing epsB | This study |

| pCepsB | pUC18‐mini‐Tn7T‐Gm derivative carrying a 3.1‐kbp fragment containing epsB, Gmr | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi‐1 hsdR17supE44 Δ(lac)U169(ϕ80lacΔM15) | Takara Bio |

| Ralstonia solanacearum | ||

| OE1‐1 | Wild‐type strain, phylotype I, race 1, biovar 4 | Kanda et al. (2003) |

| ΔepsB | epsB‐deletion mutant of OE1–1 | Mori et al (2018a) |

| epsB‐comp | A transformant of ΔepsB with pCepsB containing native epsB, Gmr | This study |

| ΔphcB | phcB‐deletion mutant of OE1–1 | Kai et al. (2015) |

| ΔphcA | phcA‐deletion mutant of OE1–1 | Mori et al. (2016) |

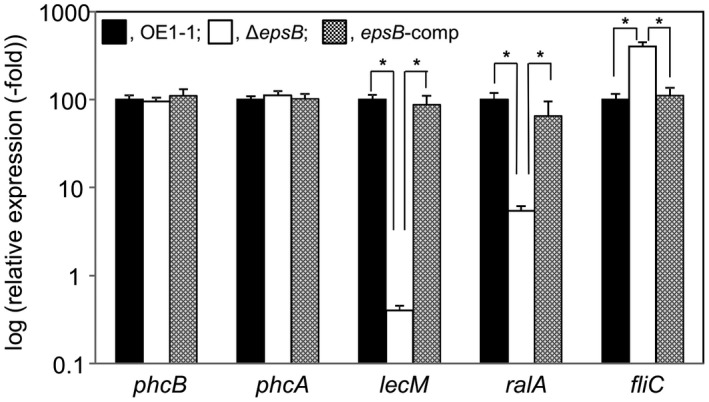

The expression levels of phcB and phcA were analysed in R. solanacearum strains ΔepsB, epsB‐comp and OE1‐1 grown in 1/4 M63 (until OD600 = 0.3) by quantitative reverse transcription‐PCR (qRT‐PCR) assays. We conducted a qRT‐PCR assay using a 500 ng total RNA template sample and 10 pm primers (Table 2) with an Applied Biosystems 7300 Real‐time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as described by Mori et al. (2016). We normalized all the values against the rpoD expression level in which there was no significant difference among samples. We conducted the experiment twice using independent samples with eight technical replicates in each experiment. Because we did not observe any significant differences between replicates, we provided results of a single representative sample. We did not observe any significant differences in the expression levels of phcB and phcA among these strains (P < 0.05, Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Primers used in the qRT‐PCR assays

| Name of gene | Name of primer | Nucleotide sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| rpoD | rpoD‐FW | ATCGTCGAGCGCAACATCCC |

| rpoD‐RV | AGATGGGAGTCGTCGTCGTCGTG | |

| fliC | fliC‐FW2 | CAAACGCAAGGTATTCAGAACG′ |

| fliC‐RV2 | ATTGGAAGGTCGTCGAAGCCAC | |

| lecM | fml‐FW2 | GTATTCACGCTTCCCGCCAACAC |

| fml‐RV2 | ATGCCGTCGTTGTAGTCGT TGTC | |

| phcB | phcB‐FW3‐514 | TACAAGATCAAGCACTACCTCGACTG |

| phcB‐RV3‐1011 | GTGCTGTACGCCATCCATCTC | |

| phcA | phcA‐FW5 | ATGCGTTCCAATGAGCTGGAC |

| phcA‐RV5 | AGATCCTTCATCAGCGAGTTGAC | |

| ralA | ralA‐FW | GCCTGGGGATAAGGTTGTAC |

| ralA‐RV | CGTCAGTACGAAAACAGCG |

Figure 2.

Expression of the quorum sensing (phc QS)‐related genes phcB and phcA, the positively phc QS‐regulated genes lecM and ralA, and the negatively phc QS‐regulated gene fliC in strains OE1‐1, the epsB‐deletion mutant (ΔepsB), which lost major EPS I productivity, and native epsB‐expressing complemented ΔepsB (epsB‐comp) of Ralstonia solanacearum. Total RNA was extracted from the bacterial cells grown in one‐quarter‐strength M63 medium (until OD600 = 0.3). The gene expression levels were presented relative to the rpoD expression level. The experiment was conducted twice using independent samples with eight technical replicates in each experiment, and produced similar results. Results of a single representative sample are provided. Bars indicate the standard errors. Asterisks indicate values that are significantly different between strains (P < 0.05, t‐test).

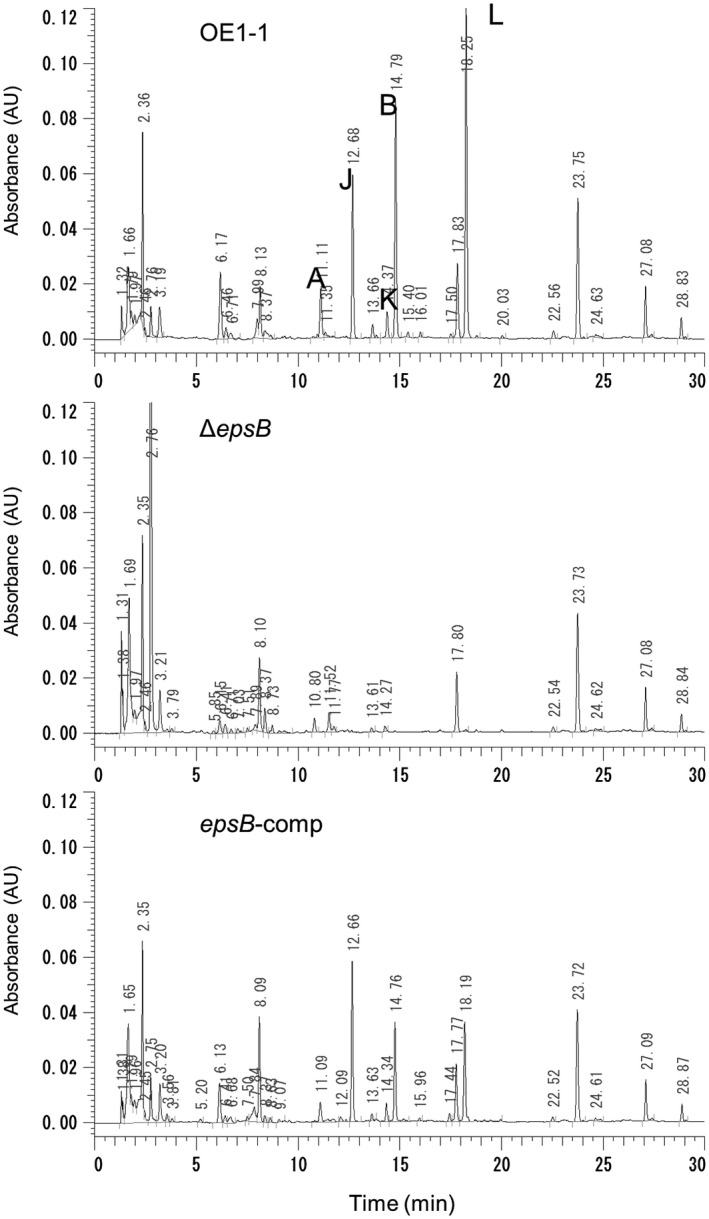

The transcriptome analysis showed that deletion of epsB led to significantly reduced expression levels of ralA and ralD. We next assessed the production of ralfuranones by R. solanacearum strains ΔepsB, epsB‐comp and OE1‐1 that were grown in 100 mL of MGRL medium (1.75 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 5.8: 1.5 mM MgSO4: 2.0 mM Ca(NO3)2: 3.0 mM KNO3: 67 Mm Na2EDTA: 8.6 Mm FeSO4: 10.3 Mm MnSO4: 30 Mm H3BO3: 1.0 Mm ZnSO4: 24 nM (NH4)6Mo7024: 130 nM CoC12: 1 μM CuS04; Fujiwara et al., 1992) including 3% sucrose for 4 days, according to a previously described procedure (Kai et al., 2014). ΔepsB produced less ralfuranones A, B, J, K and L than the strain OE1‐1 as well as epsB‐comp strain (Fig. 3). To analyse the ralA expression levels, we conducted a qRT‐PCR assay using 10 pm primers (Table 2). We observed a significantly lower expression level of ralA in ΔepsB than in the strain OE1‐1 as well as epsB‐comp strain (P < 0.05, Fig. 2). Therefore, deletion of epsB led to significantly reduced production of ralfuranones.

Figure 3.

Ralfuranone productivity of the OE1‐1 (A), the epsB‐deletion mutant (ΔepsB, B), which lost major EPS I productivity, and native epsB‐expressing complemented ΔepsB (epsB‐comp, C) Ralstonia solanacearum strains. An HPLC analysis of culture extracts from the R. solanacearum strains is shown. The peaks of ralfuranones are marked A, B, J, K and L. The experiment was conducted at least twice using independent samples and produced similar results. Results for a single representative sample are provided.

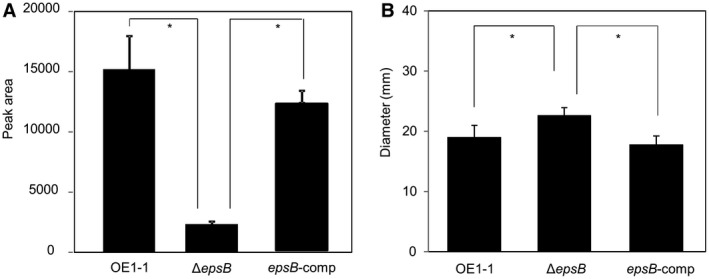

The transcriptome analysis showed that deletion of epsB led to significantly reduced expression levels of lecM. LecM affects the extracellular stability of 3‐OH MAME, contributing to the phc QS signalling pathway (Hayashi et al., 2019). We next assayed the extracellular 3‐OH MAME contents of R. solanacearum strains ΔepsB, epsB‐comp and OE1‐1. We assessed the extracellular 3‐OH MAME contents of R. solanacearum strains that were grown in B medium at 30 °C for 4–6 h, according to a previously described protocol (Kai et al., 2015). We observed a lower extracellular 3‐OH MAME content for ΔepsB than for the OE1‐1 and epsB‐comp strains (P < 0.05, Fig. 4A). To analyse the lecM expression levels in R. solanacearum strains, we conducted a qRT‐PCR assay with 10 pm primers described in Table 2. The expression level of lecM in ΔepsB was significantly lower than those in the strain OE1‐1 as well as epsB‐comp strain (P < 0.05, Fig. 2). Because the deletion of epsB did not change the expression of phcB, it was thought that the deletion of epsB resulted in significantly reduced phc QS‐dependent lecM expression, affecting the extracellular stability of 3‐OH MAME.

Figure 4.

The extracellular content of 3‐OH MAME (A) and swimming motility (B) of Ralstonia solanacearum strains OE1‐1, the epsB‐deletion mutant (ΔepsB), which lost major EPS I productivity, and native epsB‐expressing complemented ΔepsB (epsB‐comp). (A) The experiment was conducted three times using independent samples. Bars indicate the standard errors. Asterisks indicate values significantly different from those of strain OE1‐1 (P < 0.05, t‐test). (B) The experiment was repeated three times, with five technical replicates in each experiment. Bars indicate the standard errors. Asterisks indicate values that are significantly different between strains (P < 0.05, t‐test).

The phc QS negatively regulates flagellar biogenesis, suppressing the swimming motility of R. solanacearum (Tans‐Kersten et al., 2001). To analyse the expression levels of fliC encoding flagellin in the strains, we conducted qRT‐PCR assays using 10 pm primers (Table 2). We observed a significantly greater expression level of fliC in ΔepsB than in the strain OE1‐1 as well as epsB‐comp strain (P < 0.05, Fig. 2). We next analysed the swimming motilities of the ΔepsB, epsB‐comp and OE1‐1 strains incubated on 1/4 M63 solidified with 0.25% agar. ΔepsB strain exhibited significantly greater swimming motility than the OE1‐1 strain, which was similar to that of the epsB‐comp mutant (P < 0.05, Fig. 4B).

A transcriptome analysis with RNA‐Seq showed that a loss of EPS I productivity led to changes in the expression levels of c.15% of the genes expressed in strain OE1‐1 (Fig. 1). Among them, the expression levels of the genes that are positively and negatively regulated through the phc QS in strain OE1‐1 decreased (97.2%; Fig. 1A) and increased (98.0%; Fig. 1B), respectively, in ΔepsB. The expression levels of genes in ΔepsB were positively correlated with those in both ΔphcB (Fig. 1C) and ΔphcA strains (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, a deficiency of EPS I productivity led to significantly reduced ralfuranone production (Fig. 3) and a significantly enhanced swimming motility (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, the deficiency of EPS I productivity led to a significantly reduced lecM expression (Tables S1 and Fig. 2) and extracellular 3‐OH MAME content (Fig. 4A). Thus, the deficiency of EPS I production induces a negative feedback effect on the regulation of PhcA‐controlled genes, contributing to phc QS‐dependent phenotypes. Overall, EPS I may be associated with the feedback loop of QS (Fig. S1).

The epsB deletion did not affect the expression of phcB and phcA (Fig. 2 and Table S1). Although a loss in EPS I productivity led to the increased expression of 477 genes and the decreased expression of 198 genes that were expressed in strain OE1‐1, the expression levels of 27.5% and 49.5% of these genes, respectively, were independent of phc QS (Fig. 1). Thus, EPS I may not directly affect phcA expression and PhcA function, but may be involved in mechanisms supporting regulation through PhcA or a co‐transcription activator functioning with PhcA. Although the expression levels of all the transcripts in ΔepsB were positively correlated with those in ΔralA (Fig. 1E), the coefficients of correlation were lower than those of the expression levels of all the transcripts between ΔepsB and the phc QS‐deficient mutants (Fig. 1C,D). Thus, EPS I‐supported mechanisms of PhcA function may be different from the ralfuranone‐mediated feedback of phc QS.

In this study, the deficiency of EPS I production led to an induction of a negative feedback effect on the regulation of phc QS‐dependent genes. Additionally, 85% of EPS I is released as a cell‐free slime (Denny, 2006). Therefore, EPS I may mediate intercellular signalling among OE1‐1 cells, contributing to the regulation of PhcA‐controlled genes during phc QS.

Supporting information

Fig. S1 Model of the regulation of quorum sensing (phc QS) in Ralstonia solanacearum strain OE1‐1.

Table S1 RNA‐sequencing data for all the transcripts in Ralstonia solanacearum strain OE1‐1, phcB‐deletion mutant (ΔphcB), phcA‐deletion mutant (ΔphcA) and epsB‐deletion mutant (ΔepsB), which lost major exopolysaccharide (EPS I) productivity.

Table S2 Predicted functions of proteins encoded by genes that were both positively major exopolysaccharide (EPS) I‐regulated and positively phc QS‐regulated in Ralstonia solanacearum strain OE1‐1 grown in one‐quarter‐strength M63 medium.

Table S3 Predicted functions of proteins encoded by genes that were negatively major exopolysaccharide (EPS) I‐regulated and negatively phc QS‐regulated in Ralstonia solanacearum strain OE1‐1.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant numbers 17K03773, 17K19271 and 19K22310, a research donation from Sumitomo Chemical Co. Ltd and a Cabinet Office Grant‐in‐Aid, the Advanced Next‐Generation Greenhouse Horticulture by IoP (Internet of Plants), Japan to Y.H., a Sasakawa Scientific Research Grant from the Japan Science Society (no. 2018‐4060) to K.H., and a grant from the Project of the NARO Bio‐Oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution (Research Program on Development of Innovative Technology, grant no. 29003A) to K.K. and Y.H. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Araud‐Razou, I. , Vasse, J. , Montrozier, H. , Etchebar, C. and Trigalet, A. (1998) Detection and visualization of the major acidic exopolysaccharide of Ralstonia solanacearum and its role in tomato root infection and vascular colonization. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 104, 795–809. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.H. , DeShazer, D. and Schweizer, H.P. (2006) mini‐Tn7 insertion in bacteria with multiple glmS‐linked attTn7 sites: example Burkholderia mallei ATCC 23344. Nat. Protoc. 1, 162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, G.N. and Rickenberg, H.V. (1956) La galactoside‐perme´ ase d’ Escherichia coli . Ann. Inst. Pasteur (Paris), 91, 693–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Haeze, W. and Holsters, M. (2004) Surface polysaccharides enable bacteria to evade plant immunity. Trends Microbiol. 12, 555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny, T.P. (1995) Involvement of bacterial polysaccharides in plant pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Pathol. 33, 173–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny, T.P. (2006) Plant pathogenic Ralstonia solanacearum. P In: Plant‐Associated Bacteria (Gnanamanickam S. eds), pp. 573–644. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Denny, T.P. and Baek, S.R. (1991) Genetic evidence that extracellular polysaccharide is a virulence factor of Pseudomonas solanacearum . Mol. Plant‐Microbe Interact. 4, 198–206. [Google Scholar]

- Flavier, A.B. , Clough, S.J. , Schell, M.A. and Denny, T.P. (1997) Identification of 3‐hydroxypalmitic acid methyl ester as a novel autoregulator controlling virulence in Ralstonia solanacearum . Mol. Microbiol. 26, 251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara, T. , Hirai, M.Y. , Chino, M. , Komeda, Y. and Naito, S. (1992) Effects of sulfur nutrition on expression of the soybean seed storage protein genes in transgenic petunia. Plant Physiol. 99, 263–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genin, S. and Denny, T.P. (2012) Pathogenomics of the Ralstonia solanacearum species complex. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 50, 67–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, K. , Kai, K. , Mori, Y. , Ishikawa, S. , Ujita, Y. , Ohnishi, K. , Kiba, A. and Hikichi, Y. (2019) Contribution of a lectin, LecM, to the quorum sensing signalling pathway of Ralstonia solanacearum strain OE1‐1. Mol. Plant Pathol. 20, 334–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikichi, Y. , Mori, Y. , Ishikawa, S. , Hayashi, K. , Ohnishi, K. , Kiba, A. and Kai, K. (2017) Regulation involved in colonization of intercellular spaces of host plants in Ralstonia solanacearum . Front. Plant Sci. 8, 967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai, K. , Ohnishi, H. , Mori, Y. , Kiba, A. , Ohnishi, K. and Hikichi, Y. (2014) Involvement of ralfuranone production in the virulence of Ralstonia solanacearum OE1‐1. ChemBioChem, 15, 2590–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai, K. , Ohnishi, H. , Shimatani, M. , Ishikawa, S. , Mori, Y. , Kiba, A. , Ohnishi, K. , Tabuchi, M. and Hikichi, Y. (2015) Methyl 3‐hydroxymyristate, a diffusible signal mediating phc quorum sensing in Ralstonia solanacearum . ChemBioChem, 16, 2309–2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai, K. , Ohnishi, H. , Kiba, A. , Ohnishi, K. and Hikichi, Y. (2016) Studies on the biosynthesis of ralfuranones in Ralstonia solanacearum . Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 80, 440–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, A. , Yasukohchi, M. , Ohnishi, K. , Kiba, A. , Okuno, T. and Hikichi, Y. (2003) Ectopic expression of Ralstonia solanacearum effector protein PopA early in invasion results in loss of virulence. Mol. Plant‐Microbe Interact. 16, 447–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, J. , Genin, S. , Magori, S. , Citovsky, V. , Sriariyanum, M. , Ronald, P. , Dow, M. , Verdier, V. , Beer, S.V. , Machado, M.A. , Toth, I. , Salmond, G. and Foster, G.D. (2012) Top 10 plant pathogenic bacteria in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13, 614–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarvey, J.A. , Denny, T.P. and Schell, M.A. (1999) Spatial‐temporal and quantitative analysis of growth and EPS I production by Ralstonia solanacearum in resistant and susceptible tomato cultivars. Phytopathology, 89, 1233–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng, F. , Babujee, L. , Jacobs, J.M. and Allen, C. (2015) Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals cool virulence factors of Ralstonia solanacearum race 3 biovar 2. PLoS One, 10, e0139090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milling, A. , Babujee, L. and Allen, C. (2011) Ralstonia solanacearum extracellular polysaccharide is a specific elicitor of defense responses in wilt‐resistant tomato plants. PLoS One, 6, e15853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Y. , Inoue, K. , Ikeda, K. , Nakayashiki, H. , Higashimoto, C. , Ohnishi, K. , Kiba, A. and Hikichi, Y. (2016) The vascular plant‐pathogenic bacterium Ralstonia solanacearum produces biofilms required for its virulence on the surfaces of tomato cells adjacent to intercellular spaces. Mol. Plant Pathol. 17, 890–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Y. , Ishikawa, S. , Hosoi, Y. , Hayashi, K. , Asai, Y. , Ohnishi, H. , Shimatani, M. , Inoue, K. , Ikeda, K. , Nakayashiki, H. , Ohnishi, K. , Kiba, A. , Kai, K. and Hikichi, Y. (2018a) Ralfuranones contribute to mushroom‐type biofilm formation by Ralstonia solanacearum strain OE1‐1, leading to its virulence. Mol. Plant Pathol. 19, 975–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Y. , Ohnishi, H. , Shimatani, M. , Morikawa, Y. , Ishikawa, S. , Ohnishi, K. , Kiba, A. , Kai, K. and Hikichi, Y. (2018b) Involvement of ralfuranones in the quorum sensing signalling pathway and virulence of Ralstonia solanacearum strain OE1‐1. Mol. Plant Pathol. 19, 454–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly, J. , Spiteller, D. , Linz, J. , Jacobs, J. , Allen, C. , Nett, M. and Hoffmeister, D. (2013) Ralfuranone thioether production by the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum . ChemBioChem, 14, 2169–2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyraud, R. , Cottret, L. , Marmiesse, L. , Gouzy, J. and Genin, S. (2016) A resource allocation trade‐off between virulence and proliferation drives metabolic versatility in the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum . PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford, S.T. and Bassler, B.L. (2012) Bacterial quorum sensing: its role in virulence and possibilities for its control. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2, a012427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saile, E. , McGarvey, J.A. , Schell, M.A. and Denny, T.P. (1997) Role of extracellular polysaccharide and endoglucanase in root invasion and colonization of tomato plants by Ralstonia solanacearum . Phytopathology, 87, 1264–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salanoubat, M. , Genin, S. , Artiguenave, F. , Gouzy, J. , Mangenot, S. , Arlat, M. , Billault, A. , Brottier, P. , Camus, J.C. , Cattolico, L. , Chandler, M. , Choisne, N. , Claudel‐Renard, C. , Cunnac, S. , Demange, N. , Gaspin, C. , Lavie, M. , Moisan, A. , Robert, C. , Saurin, W. , Schiex, T. , Siguier, P. , Thébault, P. , Whalen, M. , Wincker, P. , Levy, M. , Weissenbach, J. and Boucher, C.A. (2002) Genome sequence of the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum . Nature, 415, 497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell, M.A. (2000) Control of virulence and pathogenicity genes of Ralstonia solanacearum by an elaborate sensory network. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 38, 263–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tans‐Kersten, J. , Huang, H. and Allen, C. (2001) Ralstonia solanacearum needs motility for invasive virulence on tomato. J. Bacteriol. 183, 3597–3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasse, J. , Frey, P. and Trigalet, A. (1995) Microscopic studies of intercellular infection and protoxylem invasion of tomato roots by Pseudomonas solanacearum . Mol. Plant‐Microbe Interact. 8, 241–251. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Model of the regulation of quorum sensing (phc QS) in Ralstonia solanacearum strain OE1‐1.

Table S1 RNA‐sequencing data for all the transcripts in Ralstonia solanacearum strain OE1‐1, phcB‐deletion mutant (ΔphcB), phcA‐deletion mutant (ΔphcA) and epsB‐deletion mutant (ΔepsB), which lost major exopolysaccharide (EPS I) productivity.

Table S2 Predicted functions of proteins encoded by genes that were both positively major exopolysaccharide (EPS) I‐regulated and positively phc QS‐regulated in Ralstonia solanacearum strain OE1‐1 grown in one‐quarter‐strength M63 medium.

Table S3 Predicted functions of proteins encoded by genes that were negatively major exopolysaccharide (EPS) I‐regulated and negatively phc QS‐regulated in Ralstonia solanacearum strain OE1‐1.