Abstract

Nitro-fatty acids (NO2-FA) undergo reversible Michael adduction reactions with cysteine and histidine residues leading to the post-translational modification (PTM) of proteins. This electrophilic character of NO2-FA is strictly related to their biological roles. The NO2-FA-induced PTM of signaling proteins can lead to modifications in protein structure, function, and subcellular localization. The nitro lipid-protein adducts trigger a series of downstream signaling events that culminates with anti-inflammatory, anti-hypertensive, and cytoprotective effects mediated by NO2-FA. These lipoxidation adducts have been detected and characterized both in model systems and in biological samples by using mass spectrometry (MS)-based approaches. These MS approaches allow to unequivocally identify the adduct together with the targeted residue of modification. The identification of the modified proteins allows inferring on the possible impact of the NO2-FA-induced modification. This review will focus on MS-based approaches as valuable tools to identify NO2-FA-protein adducts and to unveil the biological effect of this lipoxidation adducts.

Highlights

-

•

Nitro-fatty acids (NO2-FA) are endogenous bioactive lipids.

-

•

NO2-FA form reversible Michael adducts with proteins leading to PTMs.

-

•

Adduction of NO2-FA with proteins culminates to anti-inflammatory, anti-hypertensive, and cytoprotective effects.

-

•

Mass spectrometry (MS)-based approaches allows to identify NO2-FA-protein adducts and to unveil their biological effects.

1. Introduction

During the last decade, nitrated lipid gained the interest of the scientific community, as new endogenous signaling molecules with important regulatory role in health and disease. Research on this is aimed at understanding the reactivity of reactive nitrogen species (RNS) with lipids, to unravel their occurrence in vivo and their biological roles. Among nitrated and nitroxidized lipids identified so far, the nitro-fatty acids (NO2-FA) are best-known products of RNS. These products have been widely detected in several tissues [1], [2], [3], [4], [5] and biofluids [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], and are nowadays a hot topic in nitro lipidomics. NO2-FA are considered important bioactive molecules and have been associated with anti-inflammatory [6], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], anti-hypertensive [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], and anti-thrombotic properties [31], [33] and cytoprotective effects [2], [34], [35], [36], [37]. More recently, other nitrated and nitroxidized lipids [1], [6], [7], [8], [13], [38] and also nitro derivatives of phospholipids (PL) [39], [40] and triglycerides (TAG) [41] have been detected in biological samples and were associated with protective and beneficial effects, but they are scarcely studied. Also, esterified forms of NO2-FA have been found as they can be generated either by direct nitration of the esterified fatty acyl moiety or by the incorporation of NO2-FA [41].

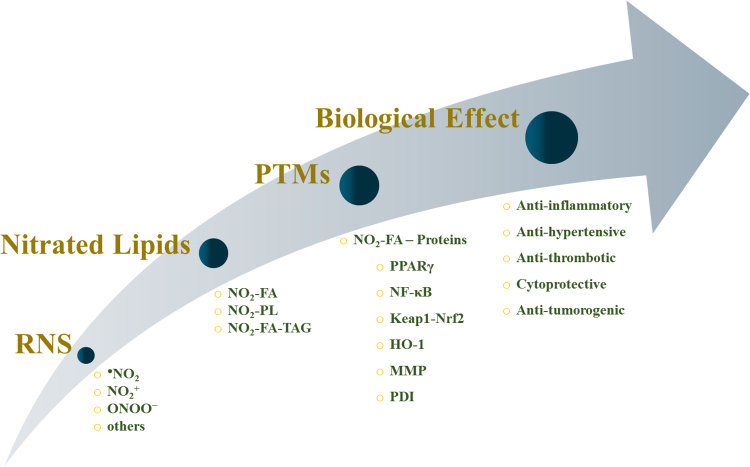

NO2-FA are also known as nitroalkenes derivatives of fatty acids since it includes a nitro group linked to the double bond (alkene group) of the unsaturated fatty acyl chain, and the nitro-alkene moiety makes these derivatives highly reactive with electrophilic properties. These endogenous electrophilic lipids are capable to covalently link to proteins, via Michael addition [42], leading to the formation of lipoxidation adducts. This type of post-translational modification (PTM) of proteins can modulate protein function, which underlies some of the biological roles attributed to the NO2-FA (Fig. 1). Some of these PTMs are shown to elicit a protective effect, which may provide clues for new therapeutic strategies and new drugs.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of nitrated lipids pathways: from their generation to their biological effect.

Detection of NO2-FA and especially their lipoxidation adducts are still a challenge that is mostly addressed by MS approaches. MS-based approaches have been extensively applied in the study of NO2-FA-protein adducts [4], [7], [34], [42], [43], [44], providing detailed structural information of these adducts both in vitro and in vivo. LC-MS and MS/MS-based proteomics approaches have been performed to characterize the NO2-FA protein adducts and the sites of adduction [34], [42], [45], [46], [47], [48]. Very recently peptide adducts were also reported for NO2-FA esterified in phospholipids using biomimetic in vitro studies and MS approaches [49].

In this review we will discuss the formation and type of nitrated FA found in biological systems, their structure and reactivity with proteins and characterization by a MS-based proteomic and lipidomic approach that allowed to disclose possible biological roles associate with nitrated lipids-protein adducts.

2. Endogenous nitro-fatty acids

2.1. Chemistry and analysis

NO2-FA are endogenous chemical entities generated by the attack of nitric oxide (NO)-derived reactive species, collectively called reactive nitrogen species (RNS), with unsaturated fatty acids. Nitrogen dioxide (•NO2), nitronium cation (NO2+), and peroxynitrite/peroxynitrous acid, whose decomposition yields •NO2 and hydroxyl radical (•OH), were reported as RNS that most frequently initiate nitration or nitroxidation reactions in biomolecules, including lipids. The prevalence and the yield of one process of these processes over the others are dependent on the oxygen levels, concentration of ROS versus RNS, the presence of secondary target molecules (scavengers, thiols, and transition metals), pH, and the partition between hydrophilic and hydrophobic milieu in cellular compartments [50]. The mechanism of FA nitration and nitroxidation in biological systems is not yet wholly undisclosed, and there are some alternative routes to explain the generation of NO2-FA (Fig. 2). The free radical-induced nitration of FA mediated by •NO2 is one of the most prominent reaction in vivo as a source of NO2-FA [51]. The endogenous formation of NO2-FA during free radical-mediated nitration reactions occurs in several biological processes such as digestion [52], metabolic stress, and inflammatory conditions [53]. Thus NO2-FA were already identified in human red blood cells [8], [9], plasma [6], [8], [9], [10], [12], urine [6], [7], and tissues [1], [2], [3], [4], [5] at concentrations ranging from picomolar [12] to micromolar [6]. Dietary sources of nitrite can also leads to the generation of NO2-FA via acid-catalyzed nitration reactions [52], [54], [55], [56]. Recently, NO2-FA were also reported in plants, fresh olives, and in extra virgin olive oil [56], [57], which are considered external sources of NO2-FA and can contribute to rising the endogenous levels of NO2-FA [58].

Fig. 2.

Representative mechanisms of nitro-fatty acid (NO2-FA) formation. Radical-induced nitration of unsaturated fatty acids by nitrogen dioxide (•NO2) yields a β-nitroalkyl radical that can further react with other •NO2 generating the nitronitrite intermediates. Further loss of nitrous acid (HNO2) leads to the generation of the nitroalkene derivatives also called NO2-FA. Electrophilic substitution at the double bond mediated by nitronium cation (NO2+) also yields NO2-FA.

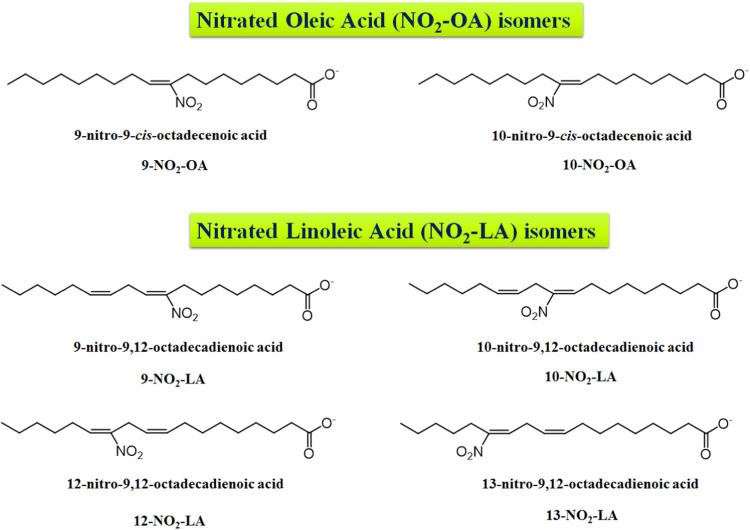

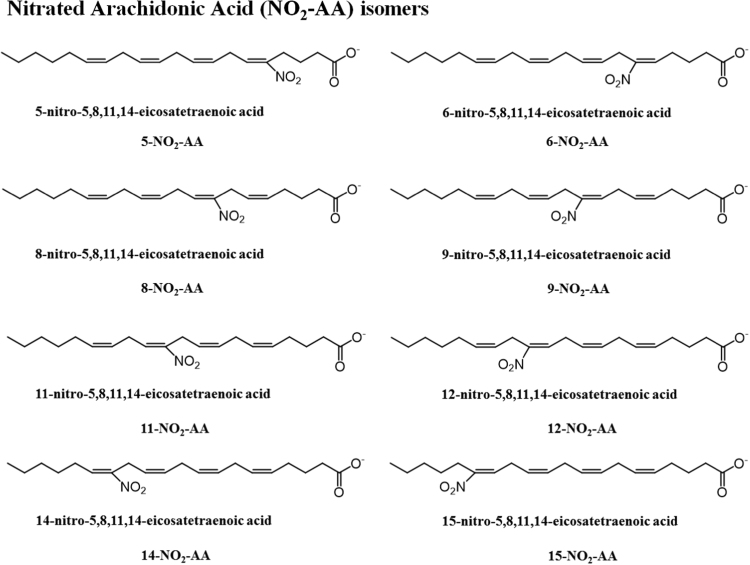

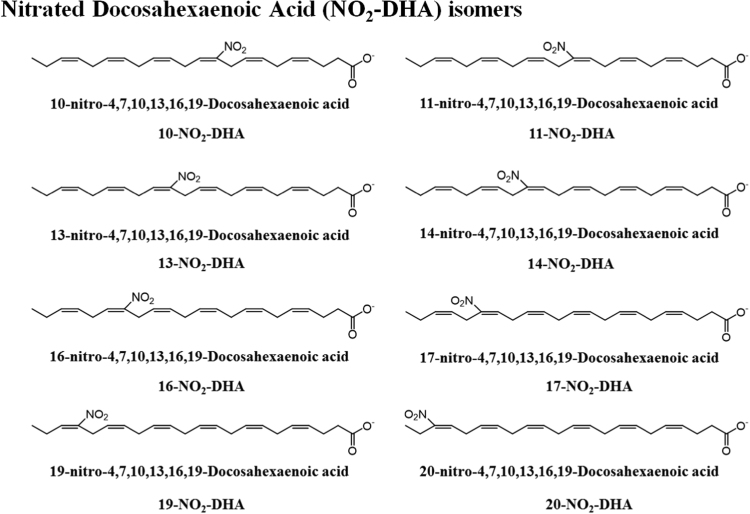

The most common NO2-FA identified in vivo were the nitrated forms of the nitro-oleic acid (NO2-OA), nitro-linoleic acid (NO2-LA), and nitro-conjugated linoleic acid (NO2-cLA) [6], [8], [9]. However, the reaction of RNS with fatty acids can lead to the generation of several nitroalkene derivatives of other fatty acids, such as the nitro-palmitoleic acid (NO2-POA), nitro linolenic acid (NO2-LNA), nitro-arachidonic acid (NO2-AA), nitro eicosapentaenoic acid (NO2-EPA), and nitro-docosahexaenoic acid (NO2-Dha) [6], [8], [38], [51]. Different stereo or positional isomers of NO2-FA were detected in vitro and in biological samples [6], [8], [38], as represented in Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5 and Table 1.

Fig. 3.

Proposed structures for nitro-oleic (NO2-OA) and nitro-linoleic acids (NO2-LA), with assignment of their different positional isomers, which were previously detected in in vitro studies and/or biological samples.

Fig. 4.

Proposed structures for nitro arachidonic acid (NO2-AA), with assignment of its different positional isomers, which were previously detected in in vitro studies and/or biological samples.

Fig. 5.

Proposed structures for nitro-docosahexaenoic acid (NO2-DHA), with assignment of its different positional isomers, which were previously detected in in vitro studies and/or biological samples.

Table 1.

Nitro-fatty acids identified in biological samples and in vitro mimetic model systems.

|

In vitromimetic model systems | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO2-FA | Isomer | Experimental model | Method | Ref. |

| Nitro-oleic acid (NO2-OA) | ||||

| NO2-OA | 9-NO2-OA | Gastric juice artificial + NO2− | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a API 4000 triple quadrupole and LTQ Orbitrap Velos | [56] |

| 10-NO2-OA | ||||

| Pancreatic lipase-digested EVOO | ||||

| NO2-OA | MPO + H2O2 + NO2− | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple quadrupole-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [6] | |

| ONOO− | ||||

| NO2− in acidic conditions | ||||

| NO2-OA | 9-NO2-OA | ●NO2 | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in API 2000 triple quadrupole | [80] |

| 10-NO2-OA | ||||

| Nitro-linoleic acid (NO2-LA) | ||||

| NO2-LA | 9-NO2-LA | Gastric juice artificial + NO2− | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in an API 4000 triple quadrupole and LTQ Orbitrap Velos | [56] |

| 10-NO2-LA | ||||

| 12-NO2-LA | Pancreatic lipase-digested EVOO | |||

| 13-NO2-LA | ||||

| NO2-LA | NO2− in acidic conditions | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a Quattro triple quadrupole | [10] | |

| Nitro-conjugated linoleic acid (NO2-cLA) | ||||

| NO2-cLA | 8-NO2-cLA | Gastric juice artificial + NO2− | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in an API 4000 triple quadrupole and LTQ Orbitrap Velos | [56] |

| 9-NO2-cLA | ||||

| 11-NO2-cLA | Pancreatic lipase-digested EVOO | |||

| 12-NO2-cLA | ||||

| NO2-cLA | 9-NO2-cLA | MPO + H2O2 + NO2− | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in an API 5000 triple quadrupole, API Q-Trap 4000, and Velos Orbitrap | [3] |

| ONOO− | ||||

| 12-NO2-cLA | ●NO2 | |||

| NO2-cLA | NO2-cLA | Photocontrollable peroxynitrite donor 2,3,5,6-tetramethyl-4- (methylnitrosoamino)phenol (P-NAP) | ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple quadrupole-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [38] |

| Multiple nitro, nitroso, and nitroxidized derivatives | ||||

| Cholesteryl-nitro linoleic acid (Chol-NO2-LA) | ||||

| Chol-NO2-LA | NO2− in acidic conditions | C18-HPLLC-ESI/MS/MS in a Quattro II triple quadrupole | [9] | |

| Chol-NO2-LA | NO2− in acidic conditions | ESI–MS and MS/MS in a 2000 Q-Trap | [66] | |

| C18-HPLC-ESI–MS and MS/MS in a 2000 Q-Trap | ||||

| Nitro-arachidonic acid (NO2-AA) | ||||

| NO2-AA | ●NO2 | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in an Esquire ion trap | [26] | |

| NO2-AA | 9-NO2-AA | NO2− in acidic conditions | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid quadrupole-linear ion trap | [51] |

| 12-NO2-AA | ||||

| 14-NO2-AA | ||||

| 15-NO2-AA | ||||

| Biological samples | ||||

| Nitro-palmitoleic acid (NO2-POA) | ||||

| NO2-POA | Human plasma and urine | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple Q-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [6] | |

| Nitrohydroxy-palmitoleic acid (NO2OH-POA) | ||||

| NO2OH-POA | Human plasma and urine | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple Q-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [6] | |

| Nitro-oleic acid (NO2-OA) | ||||

| NO2-OA | Human red cells, plasma and urine | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple Q-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [6] | |

| NO2-OA | 9-NO2-OA | Myocardial heart tissue from a murine model of focal myocardial ischemia/reperfusion | C18-HPLC-ESI MS/MS | [1] |

| 10-NO2-OA | ||||

| NO2-OA | NO2-OA and β-oxidation metabolites | NO2-OA acute intravenous treatment of mice with LPS-induced inflammation | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS/MS in an API 5000 triple quadrupole | [107] |

| NO2-OA | NO2-OA and its metabolic derivatives | Human and rat urine after intravenous administration of NO2-OA | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a LTQ Velos Orbitrap and API 5000 triple quadrupole | [61] |

| NO2-OA | NO2-OA and its metabolic derivatives | Mitochondrial extracts from rat hearts after ischemia-reperfusion | BME trans-nitroalkylation + C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a 4000 Q trap hybrid triple quadrupole-linear ion trap | [62] |

| Dinitro-OA | Rat cardiomyocytes treated with peroxynitrite donor 3- | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple quadrupole-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [38] | |

| morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1) | ||||

| NO2-OA | NO2-OA and its Saturation, Desaturation | Plasma from NO2-OA-treated mice | C18-HPLC-ESI MS/MS coupled to an API 4000 hybrid triple quadrupole or API 5000 triple quadrupole | [59] |

| β-oxidation metabolic derivatives | ||||

| NO2-OA | NO2-OA saturation derivatives | NO2-OA-treated BAEC cells | C18-HPLC-ESI MS/MS coupled to an API 4000 hybrid triple quadrupole or API 5000 triple quadrupole | [59] |

| NO2-OA | NO2-OA and its derivatives | Liver lipid extracts from NO2-OA-treated mice | C18-HPLC-ESI MS/MS coupled to an API 4000 hybrid triple quadrupole or API 5000 triple quadrupole | [59] |

| Nitrohydroxy-oleic acid (NO2OH-OA) | ||||

| NO2OH-OA | Human red cells, plasma and urine | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple Q-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [6] | |

| Nitro-linoleic acid (NO2-LA) | ||||

| NO2-LA | Myocardial heart tissue from a murine model of focal myocardial ischemia/reperfusion | C18-HPLC-ESI MS and MS/MS | [1] | |

| NO2-LA | Human plasma and urine | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple Q-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [6] | |

| NO2-LA | Human blood plasma | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a Quattro triple quadrupole | [10] | |

| NO2-LA | 9-NO2-LA | Human red cell membranes and plasma | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple Q-linear ion trap | [8] |

| 12-NO2-LA | ||||

| NO2-LA | NO2-LA and its metabolic derivatives | Mitochondrial extracts from rat hearts after ischemia-reperfusion | BME trans-nitroalkylation + C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a 4000 Q trap hybrid triple quadrupole-linear ion trap | [62] |

| Nitrohydroxy-linoleic acid (NO2OH-LA) | ||||

| NO2OH-LA | Myocardial heart tissue from a murine model of focal myocardial ischemia/reperfusion | C18-HPLC-ESI MS and MS/MS | [1] | |

| NO2OH-LA | Human plasma and urine | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple Q-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [6] | |

| Nitrokto-linoleic acid (NO2-oxo-LA) | ||||

| NO2-oxo-LA | Myocardial heart tissue from a murine model of focal myocardial ischemia/reperfusion | C18-HPLC-ESI MS/MS | [1] | |

| Nitro-conjugated linoleic acid (NO2-cLA) | ||||

| NO2-cLA | Plasma and vaginal lavages after cLA inoculation in the vaginal lumen from mice infected intravaginally with HSV-2 | C18-HPLC-MS/MS in a 6500+ Q-trap or a API 5000 | [16] | |

| Nitro-linolenic acid (NO2OH-LNA) | ||||

| NO2-LNA | Human plasma and urine | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple Q-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [6] | |

| Nitrohydroxy-linolenic acid (NO2OH-LNA) | ||||

| NO2OH-LNA | Human plasma and urine | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple Q-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [6] | |

| Nitro-arachidonic acid (NO2-AA) | ||||

| NO2-AA | Human plasma and urine | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS into a hybrid triple Q-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [6] | |

| NO2-AA | Rat cardiomyocytes treated with peroxynitrite donor 3- | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple quadrupole-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [38] | |

| morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1) | ||||

| Nitrohydroxy-arachidonic acid (NO2OH-AA) | ||||

| NO2OH-AA | Human plasma and urine | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple Q-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [6] | |

| Nitro-Eicosapentaenoic acid (NO2-EPA) | ||||

| NO2-EPA | Human plasma and urine | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple Q-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [6] | |

| Nitrohydroxy- Eicosapentaenoic acid (NO2OH-EPA) | ||||

| NO2OH-EPA | Human plasma and urine | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple Q-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [6] | |

| Nitro-Docosahexaenoic acid (NO2-DHA) | ||||

| NO2-DHA and dinitro-DHA | Rat cardiomyocytes treated with peroxynitrite donor 3- | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple quadrupole-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [38] | |

| morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1) | ||||

| Nitrohydroxy-Docosahexaenoic acid (NO2-DHA) | ||||

| NO2OH-DHA | Rat cardiomyocytes treated with peroxynitrite donor 3- | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple quadrupole-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [38] | |

| morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1) | ||||

| Nitrohydroxy-Docosapentaenoic acid (NO2OH-DPA) | ||||

| NO2OH-DPA | Rat cardiomyocytes treated with peroxynitrite donor 3- | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple quadrupole-linear ion trap (4000 Q-Trap) | [38] | |

| Morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1) | ||||

| Nitro-conjugated linoleic acid (NO2-cLA) | ||||

| NO2-cLA | 9-NO2-cLA | Pancreatic lipase-digested EVOO | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in an API 4000 triple quadrupole and LTQ Orbitrap Velos | [56] |

| 12-NO2-cLA | ||||

| NO2-cLA | 9-NO2-cLA | Urine of healthy humans | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a LTQ Velos Orbitrap and AB 5000 or API4000 Q-trap triple quadrupole | [7] |

| 12-NO2-cLA | ||||

| β-oxidation-metabolic derivatives of NO2-cLA | ||||

| NO2-cLA | 9-NO2-cLA | Rodents urine, plasma, and tissues (stomach, small intestine, colon, liver) after supplementation with cLA + NO2− and gastric acidification | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in an API 5000 triple quadrupole, API Q-Trap 4000, and Velos Orbitrap | [3] |

| Rodents liver and cardiac mitochondria incubated with NO2− in acidic conditions | ||||

| 12-NO2-cLA | ||||

| Rodents cardiac tissue under ischemia-reperfusion | ||||

| Raw 264.7 macrophages stimulated with LPS/IFNγ | ||||

| Healthy human plasma | ||||

| NO2-cLA | 9-NO2-cLA | RAW264.7 macrophages stimulated with LPS/IFNγ and M1, M2 and M0 polarized bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) treated with cLA | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in an API 5000 or a Q-Trap 6500+ and LTQ Velos Orbitrap | [13] |

| 12-NO2-cLA | ||||

| Reduction and β-oxidation-metabolic derivatives | ||||

| Mice Peritoneal exudates after zymosan-A induced peritonitis | ||||

| and cLA supplementation | ||||

| NO2-cLA | NO2-cLA and β-oxidation-metabolic derivatives | Urine and plasma healthy humans after ingestion of nitrite, nitrate and cLA | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a 5000 triple quadrupole | [58] |

| Cholesteryl-nitro linoleic acid (Chol-NO2-LA) | ||||

| Chol-NO2-LA | Human blood plasma and lipoproteins from normolipidemic/healthy subjects | C18-HPLLC-ESI/MS/MS in a Quattro II triple quadrupole | [9] | |

| Chol-NO2-LA | J774.1 macrophages timulated with LPS/IFNγ | C18-HPLC-ESI–MS and MS/MS in a 2000 Q-Trap | [66] | |

Nevertheless, the recovery of NO2-FA from biological samples, together with their detection and accurate quantification is a challenge due to their low concentration, stability issues, metabolism (β-oxidation and saturation/desaturation reactions) [59], reactivity with proteins [59] and esterification [39], [40], [41], and different distribution among tissues and biofluids [6], [12]. In line with these limitations, there has been an effort for the development of specific, standardized and reproducible methodologies of sample preparation and sensitive analytical approaches. The advent of more sensitive and sophisticated instruments, allied with the possibility of high-throughput analysis prompted by MS-based approaches, combined or not with liquid chromatography (LC-MS), has been the selected tool for the identification, structural characterization and quantification of free NO2-FA. Indeed, the detection of these lipids is an indication to disclose the bioactive properties of these nitrated derivatives. The progress in the field of MS-based approaches enabled the discovery of NO2-FA and contributed to the knowledge of NO2-FA biological roles giving information on the structure-function relationships [60]. The development of improved sample preparation techniques, chromatographic separations, high-resolution instruments with great sensitivity, and innovative tools raised the possibility of detection, structural characterization and quantification of nitro lipids in human samples and animal models both under physiological and pathological conditions [1], [3], [4], [8], [59], [61], [62], and also in plants [56] as summarized in Table 1. The identification of NO2-FA by MS is based on the detection of specific mass shifts compared to non-modified fatty acid (FA+45 Da). Using MS-based approaches, NO2-FA are preferentially analyzed in negative-ion mode as [M-H]− ions [3], [63]. However, positive-ion mode ionization can also occur, and NO2-FA can also be identified as [M+H]+ [26], [M+Li]+ [51], [M+NH4]+ [9], [41], and [M+Na]+ ions [9]. Tandem mass spectra acquired both in positive- and negative-ion mode provides information that allows the structural characterization of NO2-FA [8], [38], [51], [63], [64]. The fragmentation pattern of NO2-FA under tandem MS (MS/MS) conditions includes the typical neutral losses of 47 Da (HNO2) and product ions formed by cleavage of the hydrocarbon chain in the vicinity of the NO2 group that allow assigning this modified FA. The differentiation of isomers can be addresses by the identification of reporter fragment ions that are formed by cyclization, followed by heterolytic carbon chain fragmentation, which allows pinpointing the correct position of the NO2 group [2], [63]. These product ions have been used as diagnostic ions broadly employed for targeted analysis and quantitation of specific NO2-FA using reversed phase LC-MS/MS approaches, in biomimetic systems and in cells, tissues and biofluids [3], [6], [8], [9], [10], [12], [17], [38], [59], [65], [66]. Structural information gathered by using MS studies can be further confirmed by infrared and nuclear magnetic resonance analysis for the confirmation of the functional groups and the final structure [6], [9], [10], [30], [31], [51].

The generation of NO2-FA can be considered as the first step of nitration reactions. These species can be precursors of other nitrated and nitroxidized species because NO2-FA can undergo additional reaction with ROS and RNS to be further nitrated, leading to the formation of nitroso, dinitroso, nitronitroso, di and trinitro species, or oxidized generating the assorted nitroxidized species as nitrohydroxy, nitrohydroperoxy, nitro-epoxy and nitro-keto (Table 1) [3], [6], [8], [26], [54], [64]. All of these derivatives were already identified by (LC)-MS and characterized by (LC)-MS/MS [1], [6], [9], [38]. In fact, the great sensitivity of MS-based approaches allowed to identify both nitro and nitrohydroxy derivatives of palmitoleic, oleic, linoleic, linolenic, arachidonic and eicosapentaenoic acids in human plasma and urine [6]. However by far the NO2-FA are the most studied mostly because, in opposition to other nitrated and nitroxidized FA, they are electrophilic molecules with great capability to react with protein with the formation of lipoxidation adducts.

2.2. Biological roles of nitro-fatty acids as new metabolic mediators, signaling molecules, and new therapeutic drugs candidates

NO2-FA have raised the interest of the scientific community in last years, mainly because of their biological roles as key mediators in physiological and pathophysiological processes, as demonstrated in a variety of preclinical animal models of disease and in plants [2], [5], [13], [15], [20], [28], [32], [34], [45], [56]. They were assigned as biologically relevant and putative signaling molecules in cardiovascular disease [28], [33], myocardial ischemia/reperfusion and ischemia preconditioning [1], [2], [24], nephropathy [24], renal ischemia/reperfusion [24], diabetes and metabolic syndrome [14], pulmonary inflammation [15], [67] and chronic inflammatory disease [65]. NO2-FA reach endogenous levels that allow them to mediate pivotal signaling actions as cytoprotective and pro-survival players [2], [34], [35], [36], [37], and based on their pleiotropic actions, NO2-FA has emerged as potential therapeutic agents with high potential for therapeutic use (Table 2). In fact, NO2-FA already undergo clinical trials [68]. The 10-NO2-OA (CXA-10) demonstrated promising pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics characteristics during preclinical experiments [61], [68], [69]. CXA-10 is currently in phase II clinical trials for the treatment of chronic inflammatory and metabolic-related diseases, namely focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension, since it demonstrated beneficial effects when administrated via intravenous injections or through ingestion [61], [68], [69].

Table 2.

Modulation of target signaling pathways by NO2-FA and related biological properties.

| Anti-inflammatory |

|---|

|

| Vasorelaxation |

| Antioxidant |

| Anti-hypertensive |

| Anti-hyperglycemic |

| Anti-thrombotic |

| Cytoprotective |

| Anti-tumorogenic |

|

The biological actions of NO2-FA are mediated via a) decay reactions and transduction of nitric oxide (•NO) signaling actions [29], [70], since NO2FA can be considered NO donor; b) via receptor-dependent and c) via electrophilic adduction reactions to proteins [42], with formation of lipoxidation adducts. All these processes mediate important and specific signaling roles. These signaling actions are summarized in Table 2. Nitric oxide release by NO2-FA has been associated with potential antioxidant properties through inhibition of lipid peroxidation process [71]. Additionally, the release of •NO by both NO2-FA and nitrohydroxy FA derivatives has also been related with vasorelaxation properties of these nitrated lipid [26], [29], [30], [31], [51]. The nitro derivatives of arachidonic acid, NO2-AA and nitrohydroxy-AA, were also reported to be able to release •NO and thus to induce cGMP-dependent vasorelaxation in rat aortic ring in an endothelium-independent manner [26], [31], [51]. NO2-LA, NO2-cLA and nitrohydroxy-LA promoted vessel relaxation via cGMP-dependent and endothelial-independent manner in pre-constricted rat aortic rings [29], [30]. Nevertheless, the •NO release by nitro lipids remains a controversial issue, and at some level, considered of minor relevance at endogenous levels [28], [29], [51], [70], [72]. Actually, •NO signaling actions mediated by NO2-FA mainly occurs via cGMP-independent mechanisms. NO2-FA modulates endothelial (eNOS) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) gene expression and activity and consequently the eNOS- and iNOS-mediated •NO generation and reactions. Also, NO2-FA modulates a broad array of signaling pathways that culminates with the downstream activation or inactivation of •NO signaling [67], [73], [74].

The covalent adduction to key proteins propelled by the electrophilic character of NO2-FA seems to be the most prominent mechanism by which these nitro lipids spread their modulatory and protective actions. The identification and characterization of these NO2-FA-protein adducts in distinct biological conditions have been achieved by reversed phase LC-MS-based proteomics approaches [28], [42], [56], [59], [75], [76]. This topic will be discussed in more detail in the next section.

As endogenous molecules, NO2-FA undergo a series of metabolic, trafficking and clearance pathways that influences the regulation of activity, half-life and levels of free NO2-FA. Protein adduction and esterification in complex lipids [70], [77], [78] are considered as reservoirs of NO2-FA, allowing to regulate their endogenous levels [70], [77], [78]. NO2-FA–protein adducts are reversible in biological systems [59], [73], [79] and NO2-FA esterified forms can be hydrolyzed and mobilized by esterases and lipases, allowing NO2-FA to return to free active forms [70], [80]. NO2-FA can be metabolized via β-oxidation that mediates the formation of shorter and more polar electrophilic species [59] that retains the electrophilic power, but also to inactive nitroalkane species [7], [59]. In fact, in humans and rodents, the bio-elimination pathways of 10-NO2-OA involves the generation of a series of shorter metabolites that were detected in urine using C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS using both LTQ Velos Orbitrap and API 5000 triple quadrupole instruments [61]. However, the electrophilic functionality of NO2-FA is irreversibly inactivated after reduction and conversion to the correspondent nitroalkane derivative by the nitroalkene saturase prostaglandin reductase-1 [81]. Both saturation and desaturation of the double bond of NO2-FA are related with the generation of non-electrophilic NO2-FA [59], which are nitro derivatives without signaling abilities. Adduction to peptides or proteins seems to have other proposes, such as the case of conjugation with GSH, which increases the urinary excretion rate of NO2-FA excreted in urine [82]. Incorporation of NO2-FA into lipoproteins is another way for NO2-FA to enter in circulation and to be systemically distributed among tissues. The modulation of all of these diverse pathways will impact the potential reactivity, the efficacy of signaling actions and behavior of these nitration products.

The signaling actions of NO2-FA are also mediated through the modulation of the structure and regulation of the expression and activity of anti- and pro-inflammatory proteins, heat shock proteins and phase II antioxidant response proteins. The capability of NO2-FA to react with specific peptides and proteins determines the role of this nitrated lipids in redox regulation with consequence in cell signaling, as will be described in the following section.

3. Nitro-fatty acids and protein lipoxidation adducts

3.1. Main target and biological significance of PTM by nitro-fatty acids

NO2-FA are electrophilic compounds, able to react via reversible Michael addition with nucleophiles within key proteins, leading to the formation of lipid-protein adducts (lipoxidation) in a process generally denominated nitroalkylation [83], [84]. The target nucleophiles in peptides and proteins include the deprotonated thiolate group of cysteine and the nucleophilic amino group of the imidazole moiety of histidine or the amino groups of lysine and arginine [83], [84], [85]. The high electronegative olefinic NO2 group facilitate the addition to the double bond of the unsaturated hydrocarbon chain of NO2-FA. This addition generates an important positive density of charge in the methylenic β-carbon adjacent to the nitration site. The oxygens of the NO2 group withdraw electrons and the double bond is rearranged over the C–N bond, generating a carbocation. This conjugation makes the β-carbon adjacent to the NO2 group electron poor and with potential reactivity. The NO2-FA-protein covalent adducts generated during the nitroalkylation process are reversible, which seems to be related with the possibility of redox regulation [59], [73], [79] and thus can be associated with the apparent lack of toxicity of these modified lipids. All of the aforementioned characteristics make NO2-FA as promising pharmacological compounds. In fact, pre-clinical and human trials has demonstrated the NO2-FA favorable pharmacokinetics and safety.

The formation of NO2-FA adducts with proteins is considered a key PTM of proteins. This modification of functionally-relevant proteins can modulate the patterns of gene expression programs, transcription factors function, enzyme function and activity, metabolic and inflammatory responses, and cell signaling networks [50], [59], [73], [84]. This lead to a series of downstream signaling events that are intrinsically related to the biological signaling roles of NO2-FA [2], [6], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [61], [74], [75], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90] (Table 2). The activation of several of these pathways are considered essential for restoring the homeostasis and the redox balance and makes NO2-FA promising pharmacological compounds [91].

There are several proteins reported to be targets of NO2-FA electrophilic reactivity, for example, the p65 subunit of NF-κB [1], [23], [92], heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) [17], [19], [22], [67], [89], [93], mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphatase 1 (MPK-1) [92], Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap 1) [17], [22], [46], [88], metalloproteinases (MMP-7 and MMP-9) [75], glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) [42], [94], protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) [95], and transient receptor potential (TRP) channels [96], [97], [98], [99] (Table 3). NO2-FA can also conduct their biological signaling roles by a receptor-dependent signaling action and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) is one of the main targets, which is a significant route for the anti-inflammatory effect associated with NO2-FA derivatives [6], [23], [47], [65], [93], [100], [101], [102].

Table 3.

Nitro-fatty acids lipoxidation adducts identified in biological samples and in vitro mimetic model systems by using mass spectrometry-based approaches.

| Protein/peptide | Model system | Method | Molecular mechanism signaling action | Biological role | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitro-oleic acid (NO2-OA) | |||||

| Cysteine | Incubation of NO2-OA and cysteine | C18-HPLC-MS and MS/MS in a triple quadrupole API 4000 | [56] | ||

| Incubation of NO2-OA and cysteine | C18-HPLC-MS and MS/MS in a triple quadrupole | [43] | |||

| Whole olives, mesocarp and peel | C18-HPLC-MS and MS/MS in a triple quadrupole API 4000 | [56] | |||

| GSH | NO2-OA-Cys adduct generation after incubation between NO2-OA and GSH | BME trans-nitroalkylation + C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a Q trap 4000 | [62] | ||

| NO2-OA-Cys adduct generation after incubation between NO2-OA and GSH | (BME trans-nitroalkylation +) C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple quadrupole API 4000 or API 5000 triple quadrupole | [59] | |||

| Plasma from NO2-OA-treated mice | (BME trans-nitroalkylation) C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple quadrupole API 4000 or API 5000 triple quadrupole | [59] | |||

| NO2-OA-Cys adduct generation after incubation between NO2-OA and GSH | ESI-MS in LCQ ion trap | [42] | |||

| Tryptic digestion + C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in an ESI-LCQ ion trap | |||||

| C18-HPLC-ESI-MS/MS in a Q-Trap 4000 | |||||

| Red blood cells obtained from healthy humans | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS/MS in a Q-Trap 4000 | Translocation to membrane | Regulation of enzyme function, cell signaling, and protein trafficking | [42] | |

| GAPDH | Cytosolic and membrane-associated protein fractions from red blood cells obtained from healthy humans | SDS-PAGE under non-reducing and denaturing conditions + Tryptic digestion + C18-nanospray LC-MS and MS/MS in a LTQ ion trap | Translocation to membrane | Regulation of enzyme function, cell signaling, and protein trafficking | [42] |

| Cys149 | |||||

| His303 | |||||

| GAPDH | Incubation of NO2-OA and GAPDH | MALDI-TOF MS (Voyager DE PRO system) | [42] | ||

| Cys149 | |||||

| C18-HPLC-MS in a LTQ ion trap | |||||

| Cys153 | |||||

| Tryptic digestion and MALDI-TOF MS (Voyager DE PRO system) | |||||

| Cys244 | |||||

| His108 | |||||

| Tryptic digestion + C18-HPLC-ESI-MS in an ESI-LCQ ion trap | |||||

| His134 | |||||

| His327 | Tryptic digestion + C18-nanospray LC-MS and MS/MS in a LTQ ion trap | ||||

| GAPDH | Incubation of NO2-OA and GAPDH | Electrophoresis under reducing conditions + BME trans-nitroalkylation + C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a 4000 Q trap hybrid triple quadrupole-linear ion trap | [62] | ||

| 5-LOX | Incubation of NO2-OA and human recombinant 5-LOX | Tryptic digestion and C18-nanoHPLC-ESI-MS and MS in an Orbitrap XL | Irreversible inhibition of 5-LOX activity and | Anti-inflammatory | [45] |

| Cys416 | |||||

| Cys418 | |||||

| His125 | |||||

| His360 | Incubation of NO2-OA and human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNL) (intact and cell lysates) | ||||

| Prevention of lung injury and systemic immune responses | |||||

| His362 | |||||

| His367 | |||||

| His372 | NO2-OA treatment in murine model of LPS-induced inflammation (lung injury and cellular infiltration) | ||||

| His432 | |||||

| Keap1 | Incubation of NO2-OA and recombinant Keap1 | Tryptic digestion C18-HPLC-MS and MS/MS in a LTQ | Release of Nrf2 tracsription factor to the nucleous for induction of expression of antioxidant phase II enzymes | Antioxidant | [46] |

| Cys38 | |||||

| Cys151 | |||||

| Cys226 | |||||

| Cys273 | Human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293T cells transfected with recombinant Keap1 and treated with NO2-OA | ||||

| Cys288 | |||||

| Cys257 | |||||

| Cys489 | |||||

| Catephsin S | Incubation of NO2-OA with a synthetic Cat S peptide (Cat S23–29) | C18-HPLC-MS and MS/MS in a Q Exactive Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap | Downregulation of Cat S expression and activity | Tissue Protection | [5] |

| (Cat S) | |||||

| Anti-inflammatory | |||||

| Cys25 | |||||

| Fp subunit of mitochondrial complex II | Incubation of NO2-OA with recombinant human complex II Fp subunit | Tryptic digestion and C18-HPLC-MS and MS/MS in a LTQ-XL | Inhibition of mitochondrial respiration complex II and O2●− production | Cytoprotective | [48] |

| His2 | |||||

| His5 | |||||

| His6 | |||||

| Rat heart mitochondria treated with OA-NO2 | Blue native electrophoresis, BME trans-nitroalkylation, C18-HPLC-MS amd MS/MS in a hybrid triple-quadrupole linear ion trap mass spectrometer (4000 Q trap) | Promotion of glycolysis | Antioxidant | ||

| Cys9 | |||||

| Cys14 | |||||

| AT1R | HEK293 cells overexpressing AT1R treated with NO2-OA | Immunoprecipitation of AT1R from cell lysates, BME trans-nitroalkylation reaction of AT1R-bound NO2-OA, and C18-HPLC-MS and MS/MS in a 4000 Q-Trap triple quadrupole | Inhibits AT1R-dependent vasoconstriction by reduction of heterotrimeric G-protein coupling and inhibition of IP3 and calcium mobilization | Anti-hypertensive | [28] |

| MMP-7 | Incubation of NO2-OA with recombinant human proMMP-7 and proMMP-9 | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a LTQ-XL | Modulation of proteolytic activity | Anti-inflammatory | [75] |

| Cys70 | |||||

| C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple quadrupole-linear ion trap 4000 Q-Trap | Decrease of enzyme expression | ||||

| MMP-9 | |||||

| Cys100 | |||||

| Albumin | Plasma from intraperitoneal NO2-OA-treated mice | Electrophoresis under reducing conditions + BME trans-nitroalkylation + C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a 4000 Q trap hybrid triple quadrupole-linear ion trap | [62] | ||

| Plasma from NO2-OA-treated mice | Electrophoresis + BME trans-nitroalkylation + C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple quadrupole API 4000 or API 5000 triple quadrupole | [59] | |||

| PPARγ | Incubation of NO2-OA with human recombinant PPARγ LBD | Tryptic digestion and C18-HPLC-MS and MS/MS in a LTQ | Activation of PPARγ-related gene expression for glucose regulation and adipogenesis | Anti-hyperglycemic | [47] |

| HEK 293 T cells were transfected with PPARγ and treated with NO2-OA | Immunoprecipitation, gel electrophoresis, BME- trans-nitroalkylation and ESI-MS and MS/MS in a hybrid triple quadrupole-linear ion trap mass spectrometer (4000 Q Trap, | Decrease in adipogenesis | |||

| Cys285 | Increase glucose uptake | Anti-adipogenic effect | |||

| His266 | |||||

| His323 | Restore insulin sensivity | ||||

| His425 | |||||

| His449 | |||||

| STING | Incubation human STING-transfected HEK293T cells with 10-NO2-OA | Purification with magnetic beads, tryptic digestion and MALDI LTQ | Deregulation of STING palmitoylatio | Anti-inflammatory | [16] |

| Cys88 | |||||

| Inhibition of STING signaling | |||||

| Cys91 | Orbitrap XL | Inhibition the release of type I IFN | |||

| His16 | |||||

| Nitro-linoleic acid (NO2-LA) | |||||

| cysteine | NO2-LA-Cys adduct generation after incubation between NO2-LA and cysteine | (C18-HPLC)-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a triple quadrupole | [107] | ||

| GSH | NO2-LA-Cys adduct generation after incubation between NO2-LA and GSH | ESI-MS in LCQ ion trap | [42] | ||

| C18-HPLC-ESI-MS/MS in a Q-Trap 4000 | |||||

| NO2-LA-Cys adduct generation after incubation between NO2-LA and GSH | BME trans-nitroalkylation + C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in a Q trap 4000 | [62] | |||

| NO2-LA-Cys adduct | C18-HPLC/ESI/MS in Micromass Quattro II triple quadrupole | [76] | |||

| Generation after incubation between NO2-LA and GSH | |||||

| Red blood cells obtained from healthy humans | C18-HPLC-ESI-MS/MS in Q-Trap 4000 | [42] | |||

| MCF7/WT and MCF7/MRP1–10 cells treated with NO2-LA | C18-HPLC/ESI/MS in Micromass Quattro II triple quadrupole | [76] | |||

| ANT1 | NO2-LA-treated intact perfused hearts | Immunoprecipitation + SDS-PAGE + in-gel digestion tryptic digestion + ABSciex 5800 MALDI-TOF-TOF MS and MS/MS | Mitochondrial uncoupling | Cytoprotective | [34] |

| Cys57 | |||||

| Nitro-conjugated linoleic acid (NO2-cLA) | |||||

| cysteine | NO2-cLA-Cys adduct generation after incubation between NO2-cLA and cysteine | C18-HPLC-MS and MS/MS in LTQ Velos Orbitrap and AB 5000 or API4000 Q-trap triple quadrupole | [7] | ||

| Urine from healthy humans | C18-HPLC-MS and MS/MS in LTQ Velos Orbitrap and AB 5000 or API 4000 Q-trap triple quadrupole | [7] | |||

| NO2-cLA-Cys adduct generation after incubation between NO2-cLA and cysteine | C18-HPLC-MS and MS/MS in API 5000 triple quadrupole | [44] | |||

| Urine from healthy humans | C18-HPLC-MS and MS/MS in API 5000 triple quadrupole | [44] | |||

| Nitro-arachidonic acid (NO2-AA) | |||||

| PDI | Incubation of human recombinat PDI with NO2-AA | C4-HPLC-MS of intact protein in a hybrid triple quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Q-trap 4500) | Inhibition of reductase and chaperone activity of PDI | Anti-inflammatory | [95] |

| digestion tryptic digestion and C18-HPLC-MS and MS/MS | |||||

| Cys397 | |||||

| Cys400 | |||||

The nitro lipoxidation PTM of the proteins shown in the Table 3 have been correlated with specific biological effects. For example, nitroalkylation of the p65 subunit of NF-κB [23], induction of HO-1 expression [93], PPARγ modulation [100], inhibition of the correct assembly of the active NADPH oxidase (NOX2) [74], and inhibition of both reductase and chaperone activities of PDI and possible prevention of NOX2 activation [95] have been associated with the anti-inflammatory properties of NO2-FA. Another important anti-inflammatory action of NO2-FA is attributed to their capability to induce PTM of 5-Lipoxygenase (5-LOX) limiting the inflammation induced by the 5-LOX-dependent leukotriene synthesis. This point deserves to be further explored as a potential therapeutic/pharmacological strategy due to the physiological relevance of 5-LOX, namely in inflammation [45]. Induction of HO-1 and activation of Nrf2 have been correlated with protection against oxidative stress and antioxidant actions of NO2-FA [93]. Activation of PPARγ by NO2-FA has also been associated with glucose uptake and anti-hyperglycemic effects [100]. Inhibition of the catalytic activity of sHE was associated with anti-hypertensive properties of NO2-FA [32]. Finally, neuroprotective effects associated with the decrease of protein aggregation were related with PTMs of α-synuclein by NO2-OA [35].

3.2. Identification of protein-nitro-fatty acids adducts: tools and challenges

Identification of protein nitroalkylation by NO2-FA has been disclosed by using different experimental approaches, as crystallographic analysis [100], [101], western immunoblot-based assay [2], [23], [32], [34], [87], spectrophotometry [7], [43], [44], [94] and MS-based approaches [4], [7], [34], [42], [43], [44]. However, spectrophotometry and immunoassays do not give detailed structural information and crystallography requires pure proteins, being difficult to be used in the analysis of complex biological samples.

Mass spectrometry, namely using matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) or electrospray (ESI) MS-based proteomics approaches, often coupled to reverse phase (RP) liquid chromatography (LC–MS), are the most suitable methods for detection and characterization of adducts formed between NO2-FA and proteins. In vitro generation of NO2-FA-protein adducts, in biomimetic systems, between standards of NO2-FA and candidate peptides or proteins has been used as strategy for the initial identification by (LC)-MS and further characterization of these adducts by MS/MS. Data obtained using these biomimetic approaches using controlled reaction conditions are more straightforward and relatively easy to analyze. This, in turn, allows to obtain knowledge on the reactivity of each individual NO2-FA and the typical fragmentation pathways under MS/MS needed to identify these adducts. The information gathered by tandem mass experiments concerning the typical fragmentation pathways and reporter ions can be used to identify these lipoxidation products in complex biological samples by using MS-based proteomics approaches and to develop MS target analysis, namely multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) analysis. This has contributed to achieve the ultimate goal that consists of the identification of the NO2-FA-protein adducts in complex biological samples as cells, tissues, biological fluids, which requires specific and targeted approaches. Bottom-up proteomics approaches are usually performed. Through these analytical approaches, it is possible to unequivocally identify the modified peptides after enzymatic digestion of NO2-FA-protein adduct, usually using trypsin, followed by the analysis of the tryptic peptides by reverse-phase (RP)-LC-MS and MS/MS. The addition of the NO2-FA moiety increases the retention time of the modified peptides [42], which are identified on the mass spectra as singly, [M+H]+ ions, or multiple charged ions, [M+nH]n+, based on the mass shift against the unmodified peptide. This gives information on the nature of NO2-FA covalently attached to the protein. The observed mass shift in the mass spectra for the Michael adducts will be equal to the molecular weight of the NO2-FA. Thus, a mass shift of + 327 Da and + 325 Da corresponds to the addition of NO2-OA and NO2-LA, respectively [42]. MS/MS data allows to confirm the nature of the modification and provides information on the fragmentation pattern of NO2-FA-peptide adducts. These data further allows to pinpoint the location of the modification site and thus the targeted residue in the peptide backbone [103], [104]. Detailed information to identify the sites of adduction is revealed by a mass shift of the typical b and y product ions of the adducted peptide, when compared with the non-modified one. The modified immonium ions are also useful to confirm the presence of a modified amino acid residue within the adducted peptide.

RP-LC-ESI-MS and MS/MS were used to detect lipoxidation adducts formed between NO2-OA or NO2-LA and GAPDH and GSH in vivo in healthy human red cells [42]. This methodology was also applied to confirm the post-translational modifications of matrix metalloproteinase by NO2-OA [75], and for the identification of reversible Michael adducts of NO2-OA and thiols of proteins and GSH in liver and plasma of NO2-OA-treated mice [59]. Significant levels of protein cysteine adducts of NO2-OA were also observed in fresh olives, especially in the peel [56]. AT1-R adducts with NO2-OA were quantified by HPLC-MS/MS using MRM scan mode in the negative-ion mode as BME adducts (BME-NO2-OA adducts) after a nucleophilic exchange of NO2-OA from AT1-R to BME. The presence of exchangeable NO2-OA demonstrated the direct adduction of AT1-R by NO2-OA, and therefore that AT1-R is a relevant cellular target for NO2-OA alkylation [28]. RP-LC-MRM scan in the positive-ion mode ([M+H]+ ions) was applied for the characterization of NO2-LA-GSH adducts in vitro and further identification in MCF7 cells treated with NO2-LA [76]. Nitroalkylation of albumin by NO2-OA and NO2-LA have been found in the plasma of mice gavage with these fatty acids [62]. Nitroalkylation of p65 subunit of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) was observed in vivo in myocardial tissue of a murine model of ischemia-reperfusion with intravenous supplementation of OA and LA [1]. One study also reported the direct analysis by MALDI-TOF-TOF MS and MS/MS, in positive-ion mode, of adenine nucleotide translocase 1 (ATN 1) adducts after NO2-LA infusion into intact perfused heats allowing to pinpoint that the nitroalkylation of ANT1 by NO2-LA occurred on Cys57 [34]. Adduction of NO2-OA to PPAR-γ [47], and to Keap1 [46] are also examples of biological detection and characterization of NO2-OA-protein adducts by MS.

The Michael addition reactions between NO2-FA and proteins is remarkably selective and depends on the nature and structural features of the NO2-FA. The fatty acyl chain length and the position of the electrophilic carbon, i.e., the position of the nitroalkene group, has a pivotal effect on the reactivity of NO2-FA [102]. Therefore both factors regulate the formation of NO2-FA-protein adducts and the biological activity of the NO2-FA [22], [42], [65], [73], [100], [101]. In spite of its four possible isomers (at C9, C10, C12 or C13), only the NO2-LA isomers bearing the NO2 at C10 and C12 were reported to selectively bind to cysteine 285 (Cys285) in the ligand-binding domain and activate PPARγ [101]. The C10 isomer of NO2-OA is more reactive toward to Cys285 in the ligand binding domain of PPARγ than the C9 isomer [47]. On the other hand, Keap1 is easily activated by the C9 isomer via nitroalkylation of Cys273 and Cys288 [22], [46]. Xanthine oxidoreductase activity is preferentially inhibited by the C9 isomer of NO2-OA or a mixture of both C9 and C10 isomers [73]. It has been reported that NO2-FA with shorter acyl chains interact stronger with Nrf2 and NF-kB [60].

Overall, the identification of NO2-FA-protein adducts is important, because it may give information, as shown in several examples reported earlier, on the potential protein targets whose modulation by NO2-FA can have potential therapeutic interest.

4. Esterified nitro-fatty acids

4.1. Nitrated phospholipids and their lipoxidation adducts

In spite of their free forms, NO2-FA can be stabilized by esterification in more complex lipids in hydrophobic compartments, as the biological membranes. Nitrated derivatives of phospholipids were identified in biomimetic model systems and also in vivo [39], [40]. In mimetic model studies, nitrated PLs were generated after in vitro incubation of PL standards (phosphatidylcholines, PCs and phosphatidylethanolamines, PEs) and NO2BF4, and its characterization was performed using C5-LC-MS and MS/MS in a Linear ion trap [39], [40]. Nitrated PCs and nitrated PEs were detected by HILIC-LC-MS and MS/MS-based lipidomic approaches in cardiac mitochondria from diabetic rats [39] and cardiomyoblasts subjected to starvation [40]. Nitrated 1-palmitoyl-2-oleyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (nitrated POPC) was reported to have antioxidant properties as scavenging agent, mediated by its anti-radical potential and ability to inhibit lipid peroxidation. Anti-inflammatory properties of nitrated POPC, related with its ability to inhibit iNOS expression in LPS-activated macrophages, were also reported [105].

NO2-FA incorporation in PLs was also reported by using C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in API 4000 Q-trap triple quadrupole in adipocytes supplemented with NO2-SA, NO2-OA, NO2-cLA, and NO2-LA, before and after acidic hydrolysis. The incorporation yield and profile was specific for each supplemented NO2-FA and PL class, being PC the PL class with highest levels of incorporation of NO2-FA [106].

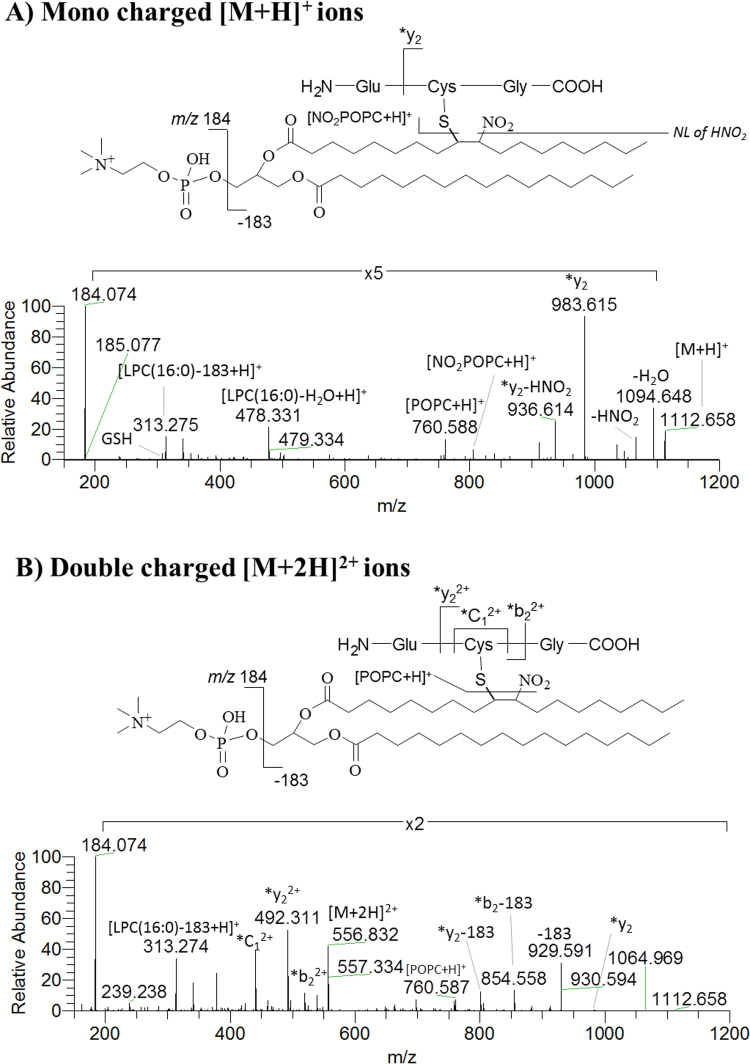

Nitrated POPC was also found to have the capability to form adducts with peptides. The identification of the covalent adducts of NO2POPC with GSH was characterized by tandem MS in different instruments and the typical fragmentation pathways were disclosed for the first time. In this study, the NO2POPC-GSH adducts were generated under biomimetic conditions and characterized by direct infusion MS and MS/MS using different instrumental platforms including LXQ linear ion trap, Q-TOF 2, and Q-Exactive Hybrid Orbitrap. The observed fragmentation pattern of NO2POPC-GSH adducts included product ions that confirmed the presence of the phosphatidylcholine moiety (m/z 184.074 and neutral loss of 183 Da), the nitro group (neutral loss of HNO2), and *y2, *b2 and *C1 fragment ions of the modified peptide. All of these product ions pinpointing that NO2POPC was linked to a cysteine residue of GSH (Fig. 6) and can be used as reporter ions applied in the search of these lipoxidation adducts in biological samples [49].

Fig. 6.

ESI-MS spectra of mono charged [M+H]+ (A) and double charged [M+ 2H]2+ ions (B) of NO2POPC-GSH adducts, acquired in Q-Exactive Orbitrap, with identification of major fragmentation pathways. (Reprinted with permission from [49], copyright 2018 [John Wiley & Sons]).

4.2. Nitrated triacylglycerides

Nitrated triacylglycerides (NO2-FA-TAG) have been reported in rat plasma after oral administration of NO2-OA, together with β-oxidation and dehydrogenation derivatives of NO2-FA-TAG in adipocytes supplemented with NO2-OA. These studies were performed by C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in API4000 Q-trap triple quadrupole and LTQ Velos Orbitrap instruments [41]. Another study reported the differential esterification profile of NO2-FA and their metabolites in TAGs in adipose tissue of rats fed with 10-NO2-OA. By using C18-HPLC-ESI-MS and MS/MS in API 4000 Q-trap triple quadrupole, the NO2-FA were observed to be preferentially incorporated in monoacyl- and diacylglycerides. This was found to be in opposite to its reduced metabolites, which were favorably incorporated in TAGs. These observations were corroborated by the analysis of the lipid polar and neutral fractions from adipocytes supplemented with NO2-SA (nitro-stearic acid), NO2-OA, NO2-cLA, and NO2-LA, after acidic hydrolysis [106].

The occurrence of nitrated phospholipids and triacylglycerides can be of high relevance at biological level. The NO2-FA-containing phospholipids and triacylglycerides can act as a reservoir of NO2-FA. Additionally, these esterified NO2-FA can be further mobilized by lipases in turn to exert their adaptive and anti-inflammatory signaling actions. In the case of NO2-FA-containing phospholipids, the NO2-FA moiety seems to be able to retain the electrophilic character, and thus the ability to undergo reversible reactions via Michael addition with key proteins. Also, these phospholipid-esterified NO2-FA can have an impact as anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective species. The nitration of esterified NO2-FA or its incorporation into more complex lipids, together with the occurrence of lipoxidation products of NO2-FA-containing phospholipids, and perhaps NO2-FA-TAGs, can also contribute to the systemic distribution and metabolism of NO2-FA.

5. Conclusion and future perspectives

NO2-FA own important physiological functions that are mediated via formation of lipoxidation adducts and associated regulation of protein function. Several signaling proteins, with key roles in anti-inflammatory, anti-hypertensive, anti-hyperglycemic, and cytoprotective pathways, are targets of NO2-FA adduction. This points to potential for new therapeutic strategies in important non-communicable diseases as cardiovascular, renal, pulmonary, and metabolic diseases. Mass spectrometry is a promising analytical tool in the detection of NO2-FA-protein adducts. Nevertheless, there is a need for new methodological developments to improve the detection of these elusive lipoxidation adducts, and to obtain more insights regarding the protein targets of NO2-FA and its roles in biological signaling pathways.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding from the European Commission's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme for the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement number 675132 (MSCA-ITN-ETN MASSTRPLAN) to University of Aveiro, Portugal. Thanks are due to the University of Aveiro, FCT/MEC, European Union, QREN, COMPETE for the financial support to the QOPNA (FCT UID/QUI/00062/2013) and CESAM (UID/AMB/50017 - POCI-01-0145-FEDER-007638), through national funds and where applicable co-financed by the FEDER, within the PT2020 Partnership Agreement, to the Portuguese Mass Spectrometry Network, RNEM, Portugal (LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-402-022125). Tânia Melo (BPD/UI51/5388/2017) is grateful to FCT for her grant.

Contributor Information

Tânia Melo, Email: taniamelo@ua.pt.

Javier-Fernando Montero-Bullón, Email: montero.bullon@ua.pt.

Pedro Domingues, Email: p.domingues@ua.pt.

M. Rosário Domingues, Email: mrd@ua.pt.

References

- 1.Rudolph V., Rudolph T.K., Schopfer F.J., Bonacci G., Woodcock S.R., Cole M.P., Baker P.R.S., Ramani R., Freeman B.A. Endogenous generation and protective effects of nitro-fatty acids in a murine model of focal cardiac ischaemia and reperfusion. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010;85:155–166. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nadtochiy S.M., Baker P.R.S., Freeman B.A., Brookes P.S. Mitochondrial nitroalkene formation and mild uncoupling in ischaemic preconditioning: implications for cardioprotection. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009;82:333–340. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonacci G., Baker P.R.S., Salvatore S.R., Shores D., Khoo N.K.H., Koenitzer J.R., Vitturi D.A., Woodcock S.R., Golin-Bisello F., Cole M.P., Watkins S., Croix C., St, Batthyany C.I., Freeman B.A., Schopfer F.J. Conjugated linoleic acid is a preferential substrate for fatty acid nitration. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:44071–44082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.401356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoeman J.C., Harms A.C., van Weeghel M., Berger R., Vreeken R.J., Hankemeier T. Development and application of a UHPLC–MS/MS metabolomics based comprehensive systemic and tissue-specific screening method for inflammatory, oxidative and nitrosative stress. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018;410:2551–2568. doi: 10.1007/s00216-018-0912-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddy A.T., Lakshmi S.P., Muchumarri R.R., Reddy R.C. Nitrated fatty acids reverse cigarette smoke-induced alveolar macrophage activation and inhibit protease activity via electrophilic S-alkylation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0153336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker P.R.S., Lin Y., Schopfer F.J., Woodcock S.R., Groeger A.L., Batthyany C., Sweeney S., Long M.H., Iles K.E., Baker L.M.S., Branchaud B.P., Chen Y.E., Freeman B.A. Fatty acid transduction of nitric oxide signaling: multiple nitrated unsaturated fatty acid derivatives exist in human blood and urine and serve as endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:42464–42675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504212200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salvatore S.R., Vitturi D.A., Baker P.R.S., Bonacci G., Koenitzer J.R., Woodcock S.R., Freeman B.A., Schopfer F.J. Characterization and quantification of endogenous fatty acid nitroalkene metabolites in human urine. J. Lipid Res. 2013;54:1998–2009. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M037804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker P.R., Schopfer F.J., Sweeney S., Freeman B.A. Red cell membrane and plasma linoleic acid nitration products: synthesis, clinical identification, and quantitation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:11577–11582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402587101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lima E.S., Di Mascio P., Abdalla D.S.P. Cholesteryl nitrolinoleate, a nitrated lipid present in human blood plasma and lipoproteins. J. Lipid Res. 2003;44:1660–1666. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200467-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lima É.S., Di Mascio P., Rubbo H., Abdalla D.S.P. Characterization of linoleic acid nitration in human blood plasma by mass spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10717–10722. doi: 10.1021/bi025504j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsikas D., Zoerner A.A., Jordan J. Oxidized and nitrated oleic acid in biological systems: analysis by GC-MS/MS and LC-MS/MS, and biological significance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2011:694–705. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsikas D., Zoerner A.A., Mitschke A., Gutzki F.M. Nitro-fatty acids occur in human plasma in the picomolar range: a targeted nitro-lipidomics GC-MS/MS study. Lipids. 2009;44:855–865. doi: 10.1007/s11745-009-3332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villacorta L., Minarrieta L., Salvatore S.R., Khoo N.K., Rom O., Gao Z., Berman R.C., Jobbagy S., Li L., Woodcock S.R., Chen Y.E., Freeman B.A., Ferreira A.M., Schopfer F.J., Vitturi D.A. In situ generation, metabolism and immunomodulatory signaling actions of nitro-conjugated linoleic acid in a murine model of inflammation. Redox Biol. 2018;15:522–531. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang T., Wang H., Liu H., Jia Z., Guan G. Effects of endogenous PPAR agonist nitro-oleic acid on metabolic syndrome in obese Zucker rats. PPAR Res. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/601562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy A.T., Lakshmi S.P., Reddy R.C. The nitrated fatty acid 10-nitro-oleate diminishes severity of lps-induced acute lung injury in mice. PPAR Res. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/617063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen A.L., Buchan G.J., Rühl M., Mukai K., Salvatore S.R., Ogawa E., Andersen S.D., Iversen M.B., Thielke A.L., Gunderstofte C., Motwani M., Møller C.T., Jakobsen A.S., Fitzgerald K.A., Roos J., Lin R., Maier T.J., Goldbach-Mansky R., Miner C.A., Qian W., Miner J.J., Rigby R.E., Rehwinkel J., Jakobsen M.R., Arai H., Taguchi T., Schopfer F.J., Olagnier D., Holm C.K. Nitro-fatty acids are formed in response to virus infection and are potent inhibitors of STING palmitoylation and signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E7768–E7775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1806239115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iles K.E., Wright M.M., Cole M.P., Welty N.E., Ware L.B., Matthay M.A., Schopfer F.J., Baker P.R.S., Agarwal A., Freeman B.A. Fatty acid transduction of nitric oxide signaling: nitrolinoleic acid mediates protective effects through regulation of the ERK pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;46:866–875. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coles B., Bloodsworth A., Clark S.R., Lewis M.J., Cross A.R., Freeman B.A., O’Donnell V.B. Nitrolinoleate inhibits superoxide generation, degranulation, and integrin expression by human neutrophils: novel antiinflammatory properties of nitric oxide-derived reactive species in vascular cells. Circ. Res. 2002;91:375–381. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000032114.68919.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole M.P., Rudolph T.K., Khoo N.K.H., Motanya U.N., Golin-Bisello F., Wertz J.W., Schopfer F.J., Rudolph V., Woodcock S.R., Bolisetty S., Ali M.S., Zhang J., Chen Y.E., Agarwal A., Freeman B.A., Bauer P.M. Nitro-fatty acid inhibition of neointima formation after endoluminal vessel injury. Circ. Res. 2009;105:965–972. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathers A.R., Carey C.D., Killeen M.E., Diaz-Perez J.A., Salvatore S.R., Schopfer F.J., Freeman B.A., Falo L.D. Electrophilic nitro-fatty acids suppress allergic contact dermatitis in mice. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017;72:656–664. doi: 10.1111/all.13067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang J., Lee K.E., Lim J.Y., Park S.I. Nitrated fatty acids prevent TNFα-stimulated inflammatory and atherogenic responses in endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;387:633–640. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kansanen E., Jyrkkänen H.K., Volger O.L., Leinonen H., Kivelä A.M., Häkkinen S.K., Woodcock S.R., Schopfer F.J., Horrevoets A.J., Ylä-Herttuala S., Freeman B.A., Levonen A.L. Nrf2-dependent and -independent responses to nitro-fatty acids in human endothelial cells: identification of heat shock response as the major pathway activated by nitro-oleic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:33233–33241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui T., Schopfer F.J., Zhang J., Chen K., Ichikawa T., Baker P.R.S., Batthyany C., Chacko B.K., Feng X., Patel R.P., Agarwal A., Freeman B.A., Chen Y.E. Nitrated fatty acids: endogenous anti-inflammatory signaling mediators. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:35686–35698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603357200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu H., Jia Z., Soodvilai S., Guan G., Wang M.-H., Dong Z., Symons J.D., Yang T. Nitro-oleic acid protects the mouse kidney from ischemia and reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2008;295:F942–F949. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90236.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kansanen E., Kuosmanen S.M., Ruotsalainen A.-K., Hynynen H., Levonen A.-L. Nitro-oleic acid regulates endothelin signaling in human endothelial cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2017;92:481–490. doi: 10.1124/mol.117.109751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balazy M., Iesaki T., Park J.L.L., Jiang H., Kaminski P.M.M., Wolin M.S.S. Vicinal nitrohydroxyeicosatrienoic acids: vasodilator lipids formed by reaction of nitrogen dioxide with arachidonic acid. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;299:611–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rudnicki M., Faine L.A., Dehne N., Namgaladze D., Ferderbar S., Weinlich R., Amarante-Mendes G.P., Yan C.Y.I., Krieger J.E., Brüne B., Abdalla D.S.P. Hypoxia inducible factor-dependent regulation of angiogenesis by nitro-fatty acids. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011;31:1360–1367. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.224626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J., Villacorta L., Chang L., Fan Z., Hamblin M., Zhu T., Chen C.S., Cole M.P., Schopfer F.J., Deng C.X., Garcia-Barrio M.T., Feng Y.H., Freeman B.A., Chen Y.E. Nitro-oleic acid inhibits angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circ. Res. 2010;107:540–548. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.218404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lima É.S., Bonini M.G., Augusto O., Barbeiro H.V., Souza H.P., Abdalla D.S.P. Nitrated lipids decompose to nitric oxide and lipid radicals and cause vasorelaxation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005;39:532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lim D.G., Sweeney S., Bloodsworth A., White C.R., Chumley P.H., Krishna N.R., Schopfer F., O’Donnell V.B., Eiserich J.P., Freeman B.A. Nitrolinoleate, a nitric oxide-derived mediator of cell function: synthesis, characterization, and vasomotor activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:15941–15946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232409599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blanco F., Ferreira A.M., López G.V., Bonilla L., González M., Cerecetto H., Trostchansky A., Rubbo H. 6-Methylnitroarachidonate: a novel esterified nitroalkene that potently inhibits platelet aggregation and exerts cGMP-mediated vascular relaxation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011;50:411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charles R.L., Rudyk O., Prysyazhna O., Kamynina A., Yang J., Morisseau C., Hammock B.D., Freeman B.A., Eaton P. Protection from hypertension in mice by the Mediterranean diet is mediated by nitro fatty acid inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:8167–8172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402965111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coles B., Bloodsworth A., Eiserich J.P., Coffey M.J., McLoughlin R.M., Giddings J.C., Lewis M.J., Haslam R.J., Freeman B.A., O’Donnell V.B. Nitrolinoleate inhibits platelet activation by attenuating calcium mobilization and inducing phosphorylation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein through elevation of cAMP. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:5832–5840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nadtochiy S.M., Zhu Q., Urciuoli W., Rafikov R., Black S.M., Brookes P.S. Nitroalkenes confer acute cardioprotection via adenine nucleotide translocase. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:3573–3580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.298406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Souza J.M., Trostchansky A., Batthyany C., Durán R., Freeman B.A., Rubbo H. Posttranslational modification of human alpha-synuclein by nitro-oleic acid. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;49:S158. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sánchez-Calvo B., Cassina A., Rios N., Peluffo G., Boggia J., Radi R., Rubbo H., Trostchansky A. Nitro-arachidonic acid prevents angiotensin II-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in a cell line of kidney proximal tubular cells. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Hoose P.M., Kelm N.Q., Piell K.M., Cole M.P. Conjugated linoleic acid and nitrite attenuate mitochondrial dysfunction during myocardial ischemia. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016;34:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Milic I., Griesser E., Vemula V., Ieda N., Nakagawa H., Miyata N., Galano J.M., Oger C., Durand T., Fedorova M. Profiling and relative quantification of multiply nitrated and oxidized fatty acids. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015;407:5587–5602. doi: 10.1007/s00216-015-8766-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melo T., Domingues P., Ferreira R., Milic I., Fedorova M., Santos S.M., Segundo M.A., Domingues M.R.M. Recent advances on mass spectrometry analysis of nitrated phospholipids. Anal. Chem. 2016;88:2622–2629. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melo T., Domingues P., Ribeiro-Rodrigues T.M., Girão H., Segundo M.A., Domingues M.R.M. Characterization of phospholipid nitroxidation by LC-MS in biomimetic models and in H9c2 Myoblast using a lipidomic approach. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017;106:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fazzari M., Khoo N., Woodcock S.R., Li L., Freeman B.A., Schopfer F.J. Generation and esterification of electrophilic fatty acid nitroalkenes in triacylglycerides. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;87:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Batthyany C., Schopfer F.J., Baker P.R.S., Durán R., Baker L.M.S., Huang Y., Cerveñansky C., Branchaud B.P., Freeman B.A. Reversible post-translational modification of proteins by nitrated fatty acids in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:20450–20563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602814200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Padilla M.N., Mata-Pérez C., Melguizo M., Barroso J.B. In vitro nitro-fatty acid release from Cys-NO2-fatty acid adducts under nitro-oxidative conditions. Nitric Oxide - Biol. Chem. 2017;68:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turell L., Vitturi D.A., Coitiño E.L., Lebrato L., Möller M.N., Sagasti C., Salvatore S.R., Woodcock S.R., Alvarez B., Schopfer F.J. The chemical basis of thiol addition to nitro-conjugated linoleic acid, a protective cell-signaling lipid. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:1145–1159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.756288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Awwad K., Steinbrink S.D., Frömel T., Lill N., Isaak J., Häfner A.-K., Roos J., Hofmann B., Heide H., Geisslinger G., Steinhilber D., Freeman B.A., Maier T.J., Fleming I. Electrophilic fatty acid species inhibit 5-lipoxygenase and attenuate sepsis-induced pulmonary inflammation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;20:2667–2680. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kansanen E., Bonacci G., Schopfer F.J., Kuosmanen S.M., Tong K.I., Leinonen H., Woodcock S.R., Yamamoto M., Carlberg C., Ylä-Herttuala S., Freeman B.A., Levonen A.L. Electrophilic nitro-fatty acids activate Nrf2 by a Keap1 cysteine 151-independent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:14019–14027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.190710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schopfer F.J., Cole M.P., Groeger A.L., Chen C.S., Khoo N.K.H., Woodcock S.R., Golin-Bisello F., Nkiru Motanya U., Li Y., Zhang J., Garcia-Barrio M.T., Rudolph T.K., Rudolph V., Bonacci G., Baker P.R.S., Xu H.E., Batthyany C.I., Chen Y.E., Hallis T.M., Freeman B.A. Covalent peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ adduction by nitro-fatty acids: selective ligand activity and anti-diabetic signaling actions. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:12321–12333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.091512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koenitzer J.R., Bonacci G., Woodcock S.R., Chen C.S., Cantu-Medellin N., Kelley E.E., Schopfer F.J. Fatty acid nitroalkenes induce resistance to ischemic cardiac injury by modulating mitochondrial respiration at complex II. Redox Biol. 2016;8:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Montero-Bullon J.-F., Melo T., Domingues M.R., Domingues P. Characterization of nitrophospholipid-peptide covalent adducts by electrospray tandem mass spectrometry: a first screening analysis using different instrumental platforms. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2018;0:1800101. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freeman B.A., Baker P.R.S., Schopfer F.J., Woodcock S.R., Napolitano A., D’Ischia M. Nitro-fatty acid formation and signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2008:15515–15519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800004200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trostchansky A., Souza J.M., Ferreira A., Ferrari M., Blanco F., Trujillo M., Castro D., Cerecetto H., Baker P.R.S., O’Donnell V.B., Rubbo H. Synthesis, isomer characterization, and anti-inflammatory properties of nitroarachidonate. Biochemistry. 2007 doi: 10.1021/bi602652j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Napolitano A., Panzella L., Savarese M., Sacchi R., Giudicianni I., Paolillo L., D’Ischia M. Acid-induced structural modifications of unsaturated fatty acids and phenolic olive oil constituents by nitrite ions: a chemical assessment. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2004;17:1329–1337. doi: 10.1021/tx049880b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pereira C., Ferreira N.R., Rocha B.S., Barbosa R.M., Laranjinha J. The redox interplay between nitrite and nitric oxide: from the gut to the brain. Redox Biol. 2013;1:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Napolitano A., Camera E., Picardo M., D’Ischia M. Acid-promoted reactions of ethyl linoleate with nitrite ions: formation and structural characterization of isomeric nitroalkene, nitrohydroxy, and novel 3-nitro-1,5-hexadiene and 1,5-dinitro-1,3-pentadiene products. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:4853–4860. doi: 10.1021/jo000090q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weitzberg E., Lundberg J.O. Novel aspects of dietary nitrate and human health. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2013;33:129–159. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071812-161159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fazzari M., Trostchansky A., Schopfer F.J., Salvatore S.R., Sánchez-Calvo B., Vitturi D., Valderrama R., Barroso J.B., Radi R., Freeman B.A., Rubbo H. Olives and olive oil are sources of electrophilic fatty acid nitroalkenes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e84884. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mata-Pérez C., Sánchez-Calvo B., Padilla M.N., Begara-Morales J.C., Valderrama R., Corpas F.J., Barroso J.B. Nitro-fatty acids in plant signaling: new key mediators of nitric oxide metabolism. Redox Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Delmastro-Greenwood M., Hughan K.S., Vitturi D.A., Salvatore S.R., Grimes G., Potti G., Shiva S., Schopfer F.J., Gladwin M.T., Freeman B.A., Gelhaus Wendell S. Nitrite and nitrate-dependent generation of anti-inflammatory fatty acid nitroalkenes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;89:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.07.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rudolph V., Schopfer F.J., Khoo N.K.H., Rudolph T.K., Cole M.P., Woodcock S.R., Bonacci G., Groeger A.L., Golin-Bisello F., Chen C.S., Baker P.R.S., Freeman B.A. Nitro-fatty acid metabolome: saturation, desaturation, β-oxidation, and protein adduction. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:1461–1473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802298200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khoo N.K.H., Li L., Salvatore S.R., Schopfer F.J., Freeman B.A. Electrophilic fatty acid nitroalkenes regulate Nrf2 and NF-κB signaling: a medicinal chemistry investigation of structure-function relationships. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:2295. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Salvatore S.R., Vitturi D.A., Fazzari M., Jorkasky D.K., Schopfer F.J. Evaluation of 10-nitro oleic acid bio-elimination in rats and humans. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:39900. doi: 10.1038/srep39900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schopfer F.J., Batthyany C., Baker P.R.S., Bonacci G., Cole M.P., Rudolph V., Groeger A.L., Rudolph T.K., Nadtochiy S., Brookes P.S., Freeman B.A. Detection and quantification of protein adduction by electrophilic fatty acids: mitochondrial generation of fatty acid nitroalkene derivatives. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;46:1250–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]