Abstract

Excessive cadmium (Cd) accumulation in rice poses a potential threat to human health. Rice varieties vary in their Cd content, which depends mainly on root-to-shoot translocation of Cd. However, cultivars accumulating high Cd in the natural population have not been completely investigated. In this study, we analyzed the variation in Cd accumulation in a diverse panel of 529 rice cultivars. Only a small proportion (11 of 529) showed extremely high root-to-shoot Cd transfer rates, and in seven of these cultivars this was caused by two known OsHMA3 alleles. Using quantitative trait loci mapping, we identified a new OsHMA3 allele that was associated with high Cd accumulation in three of the remaining cultivars. Using heterologous expression in yeast and comparative analysis among different rice cultivars, we observed that this new allele was weak at both the transcriptional and protein levels compared with the functional OsHMA3 genotypes. The weak Cd transport activity was further demonstrated to be caused by a Gly to Arg substitution at position 512. Our study comprehensively analyzed the variation in root-to-shoot Cd translocation rates in cultivated rice and identified a new OsHMA3 allele that caused high Cd accumulation in a few rice cultivars.

Keywords: Cadmium, OsHMA3, rice, root-to-shoot translocation, variation, weak allele

Variations in root-to-shoot Cd translocation rates in 529 rice cultivars were investigated and a new OsHMA3 non-functional allele that resulted in high Cd accumulation in a few rice cultivars was identified.

Introduction

Cadmium (Cd) is a highly toxic heavy metal that persists in the human body for 10−30 years and leads to health problems. Persistent intake of Cd from food can affect the renal tubules and cause rhinitis, emphysema, and other diseases (Nawrot et al., 2006). With industrial development and the overuse of phosphate fertilizers produced from Cd-rich phosphate rock, pollution of large areas of farmland by heavy metals, especially Cd, has become a significant threat to food security (Clemens and Ma, 2016). Rice (Oryza sativa), the staple food for almost half of the world's population, is a major dietary source of Cd because Cd accumulates at higher levels in rice than in other grain crops (Watanabe et al., 2004; Cheng et al., 2006). Therefore, methods of reducing Cd intake from food, especially rice, are urgently required.

Cd is not essential for plants and has no demonstrated biological function; therefore, it is assumed that specific systems for assimilating Cd have not evolved, and that Cd exploits transporters for essential metals such as manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), and iron (Fe), which show chemical characteristics similar to those of Cd (Clemens and Ma, 2016). In rice, Cd has been shown to mainly use a high-affinity Mn transporter, OsNRAMP5, to enter rice roots (Ishimaru et al., 2012; Sasaki et al., 2012). OsNRAMP5 is a gene of the natural resistance-associated macrophage protein (NRAMP) family and encodes a plasma membrane-localized protein. OsNRAMP5 is constitutively expressed in the roots and is responsible for the uptake of most Mn and Cd in rice. OsNRAMP5 knockout considerably reduced the uptake of Mn and Cd in rice (Ishikawa et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2014). Studies have also suggested that Cd can enter rice roots via Fe-transporting ion channels. OsIRT1, OsIRT2, and OsNRAMP1 are three major Fe2+ transporters in rice roots (Curie et al., 2000; Ishimaru et al., 2006) and can also transport Cd within the rice plant (Nakanishi et al., 2006; Takahashi et al., 2011). However, OsIRT1, OsIRT2, and OsNRAMP1 are mainly expressed under Fe-deficient conditions, and are therefore assumed to contribute to Cd uptake in rice roots only under such conditions.

Despite entering the root cells, most Cd still cannot reach the rice shoots, as rice plants have evolved strategies to limit Cd accumulation by compartmentalizing Cd in root cell vacuoles. In 2010, two research teams independently identified OsHMA3, the major transporter in rice responsible for sequestering Cd into root vacuoles (Ueno et al., 2010; Miyadate et al., 2011). OsHMA3 belongs to the gene family of P1B-type heavy metal ATPases and encodes a tonoplast-localized protein. The presence of non-functional OsHMA3 alleles increased Cd translocation from roots to shoots (Ueno et al., 2010; Yan et al., 2016). In contrast, overexpression of OsHMA3 enhanced the sequestration of Cd and consequently reduced Cd translocation from roots to shoots (Sasaki et al., 2014; Shao et al., 2018).

Although an increasing body of evidence shows that Cd is mainly transferred from roots to shoots via the xylem (Uraguchi et al., 2009), transporters directly involved in unloading Cd into the root xylem have not been identified. OsHMA2, a homolog of OsHMA3, has been suggested to be involved in root-to-shoot translocation of Cd and Zn, as overexpression of OsHMA2 decreased Cd and Zn translocation from roots to shoots, whereas OsHMA2 silencing produced the opposite effect (Satoh-Nagasawa et al., 2012; Takahashi et al., 2012). However, the in planta role played by OsHMA2 in root-to-shoot Cd translocation is still not clear. OsHMA2 has also been shown to be responsible for distribution of Cd and Zn to the upper nodes and panicle (Yamaji et al., 2013). OsHMA2 knockout rice plants showed low concentrations of Cd and Zn in the reproductive organs.

After reaching the nodes via the xylem, Cd is delivered to different tissues, including leaves and grains, via the vascular system in the nodes. Nodes are considered to be hubs for the distribution of almost all mineral elements, and their function requires the coordination of multiple transporters for each element (Yamaji and Ma, 2014). In addition to OsHMA2, OsLCT1 (low-affinity cation transporter 1) is another transporter involved in distributing Cd to the grain (Uraguchi et al., 2011). OsLCT1 is mainly expressed in phloem parenchyma cells in leaf blades and nodes during the reproductive stage, and encodes a plasma membrane-localized protein with Cd efflux activity. Furthermore, OsLCT1 knockdown in rice decreased the Cd concentration in grains. Therefore, OsLCT1 possibly participates in the loading of Cd into the phloem cells, and consequently facilitates the distribution of Cd from mature leaves and nodes into the grain in rice (Uraguchi et al., 2011).

Although many genes related to Cd accumulation in rice have been identified, the genetic mechanism involved in controlling the natural variation of Cd accumulation in rice is still largely unknown. Previous studies have identified two loss-of-function alleles of OsHMA3 harboring single amino acid mutations at positions 80 (Arg to His) and 380 (Ser to Arg), both of which result in excessive accumulation of Cd in rice shoots (Ueno et al., 2010; Miyadate et al., 2011; Yan et al., 2016). Interestingly, both type variants are rare in the cultivated rice population. In addition, a recent study reported that the expression level of the major Cd transporter OsNRAMP5 varied in rice cultivars, although the variations affected the accumulation of only Mn and not Cd (Liu et al., 2017). Furthermore, the levels of the iron transporter OsNRAMP1 have been reported to vary, although its contribution to Cd intake is negligible (Takahashi et al., 2011; Uraguchi and Fujiwara, 2013). CAL1, a defensin-like protein, has been suggested to regulate Cd accumulation in rice leaves, but did not affect Cd accumulation in grains (Luo et al., 2018). Thus, further mechanisms responsible for high Cd accumulation in rice grains have to be investigated.

A study suggested that root-to-shoot translocation of Cd is the major process that determines the accumulation of Cd in rice shoots and grains (Uraguchi et al., 2009). Therefore, in this study, we investigated the variation in rates of root-to-shoot Cd translocation in a population of 529 cultivated rice accessions. We also identified a new OsHMA3 allele, which was different from the previously identified alleles and led to high Cd accumulation in a few of the studied cultivars.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and field trials

The plant materials used in this study were a diverse panel of 529 rice (Oryza sativa) accessions that were collected from around the world and have been sequenced in our previous studies (Chen et al., 2014). Based on the sequence data, 295, 156, 46, 14, and 18 of the 529 accessions were grouped into indica, japonica, aus, type VI, and intermediate, respectively (see Supplementary Table 1 at JXB online). The indica accessions were further divided into indica I (IndI), indica II (IndII), and indica intermediates; similarly, the japonica accessions were further divided into temperate japonica (TeJ), tropical japonica (TrJ), and japonica intermediates. The code used in the present study for each cultivar corresponds to its ID in the public sequence database RiceVarMap2 (http://ricevarmap.ncpgr.cn/v2/) (Zhao et al., 2015), and their names and the subpopulation information are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Field trials were conducted at two locations in China: a Cd-contaminated experimental farm in Youxian, Hunan province, and a non-contaminated experimental farm of Huazhong Agricultural University in Wuhan, Hubei province. At the Youxian field site, the soil Cd concentration is ~0.4 mg kg–1 and soil pH is 5.6, whereas at the Wuhan field site the soil Cd concentration is ~0.1 mg kg–1 and the pH is 6.5. The investigation of Cd accumulation in the set of 529 accessions at the two field sites has been described in our previous study (Yang et al., 2018). An F2 population composed of 274 individuals derived from a cross between C029 (low Cd accumulation) and C093 (high Cd accumulation) was used for initial quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping. An enlarged F2 population containing 4400 individuals and a BC2F2 population with 1600 individuals were used for fine mapping. The BC2F2 population was derived from the same parents as the F2 population, and C029 was used as the recurrent parent. Five BC2F2 lines, which showed recombination in the interval between Indel7273 and Indel7626, were used to generate a BC2F3 population using self-pollination. All these populations were grown at the farm in Youxian. The planting density was 16.5 cm between plants in a row and 26 cm between rows. The trials were managed according to normal agricultural practices with regard to crop protection and paddy water management.

Hydroponic culture and Cd treatment

A series of hydroponic experiments was performed to investigate the uptake and root-to-shoot translocation of Cd and the OsHMA3 expression level in rice. Seeds were soaked in deionized water at 37 °C for 3 d and then transferred to a filter paper soaked with deionized water. After germination, the seeds were transferred to a net floating on deionized water for 7 d in a greenhouse. The seedlings were then transferred to plastic containers for hydroponic culture in the greenhouse. Hydroponic experiments were performed using a standard rice culture solution containing 1.44 mM NH4NO3, 0.3 mM NaH2PO4, 0.5 mM K2SO4, 1.0 mM CaCl2, 1.6 mM MgSO4, 0.17 mM Na2SiO3, 50 µM Fe-EDTA, 0.06 µM (NH4)6Mo7O24, 15 µM H3BO3, 8 µM MnCl2, 0.12 µM CuSO4, 0.12 µM ZnSO4, 29 µM FeCl3, and 40.5 µM citric acid, pH 5.5 (Yoshida et al., 1976). All nutrient solutions were changed every 3 d. For determination of Cd in the diverse panel of rice accessions, the plants were grown under normal conditions for 2 weeks and then transferred to 0.5 µM Cd supply for an additional week. In the Cd concentration gradient experiments, the plants were grown under normal condition for 2 weeks and then transferred to nutrient solutions with different Cd concentrations (0.02, 0.2, 2 µM) or without Cd for an additional week. At the end of the hydroponic culture, the shoots and roots were separated. Since we found no significant difference between washing the roots with water or CaCl2 in our pre-experiments (see Supplementary Fig. S1), we washed these samples three times with deionized water, and then dried them at 80 °C for 3 d before analysis.

Fine mapping of qGCd7.1

In this study, the insertion–deletion (InDel) markers were designed based on the DNA polymorphisms between C029 and C093 obtained from RiceVarMap2 (http://ricevarmap.ncpgr.cn/v2/). qGCd7.1 was fine mapped to a smaller region on chromosome 7 by integrating the genotypes and phenotypes (grain Cd concentrations) of the recombinant plants. Detailed information regarding all markers is provided in Supplementary Table S2. Gene annotation in the target region was performed using the Rice Genome Annotation Project database (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu).

Analysis of OsHMA3 sequences

Total DNA was extracted from young leaves of rice plants using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide method. To analyze the coding and promoter sequences of OsHMA3, six fragments covering the full length of OsHMA3 were amplified from the total DNA of the cultivars used in the present study and sequenced completely. The OsHMA3 sequence of Nipponbare, downloaded from the Rice Genome Annotation Project database using the locus identifier LOC_Os07g12900, was used as a reference to design the primers. All primers used for PCR amplification are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Expression level of OsHMA3

Total RNA was extracted from rice roots and shoots using the TransZol extraction kit (TransGen, Beijing, China). Total RNA was extracted from the yeast strains used for heterologous expression of OsHMA3 (see below) using EASYspin (Aidlab) following the manufacturer's protocol. The full-length cDNA was then synthesized using the EasyScript One-Step gDNA Remover and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen), following the manufacturer's protocol with an oligo(dT)20 primer. Quantitative reverse transcription–PCR was performed using the SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan) on an ABI 7500 PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems), using three independent RNA preparations as biological replicates. The rice UBQ5 gene was used as the internal control. The gene-specific primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Elemental analysis

Root samples were washed three times with distilled water prior to sampling. Root and shoot samples were dried at 80 °C for 3 d and then digested with 6 ml nitric acid at a gradient of temperatures from 120 °C to 180 °C for 1 h using a MARS6 microwave. After digestion, the samples were diluted with deionized water and then analyzed using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (Agilent 7700 series, USA).

Heterologous expression of OsHMA3 in yeast

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain Δycf1 (MATa; his3DΔ1; leu2DΔ0; met15DΔ0; ura3DΔ0; YDR135c::kanMX4), which cannot sequester Cd into vacuoles, was used for functional analysis of OsHMA3. The complete coding sequences of OsHMA3 from C029, C093, and Nipponbare were cloned into the EcoRI and KpnI sites of the yeast expression vector pYES2 (Invitrogen) and transformed into the yeast strain Δycf1. The expression of OsHMA3 in the pYES2 plasmid was driven by the GAL1 promoter (a galactose-inducible promoter). Transformants were selected on a synthetic defined (SD)-Ura medium, which contained 2% glucose, 0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 0.2% appropriate amino acids, 2% agar, and 50 mM 2-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid at pH 6.0. The drop-spotting assays were performed on SD-Ura plates in which glucose was replaced by galactose and containing 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, or 60 µM CdSO4. Cd accumulation in yeast was determined as described by Yan et al. (2016). The growth of yeast cells harboring different plasmids was monitored in liquid SD-Ura medium with or without CdSO4 in the presence of galactose. To detect the subcellular localization of OsHMA3 protein in yeast, vectors expressing eGFP:OsHMA3 fusion fragments were constructed and transformed into the yeast strain Δycf1. The green fluorescent protein (GFP) signals in yeast cells were observed by laser scanning confocal microscopy (Olympus FV1200, Japan) after incubation at 30 °C for 3 d.

Statistical analysis

ANOVA was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v. 19.0. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by comparisons of means using Tukey's test.

Results

Variation of Cd accumulation in a diverse panel of 529 rice cultivars

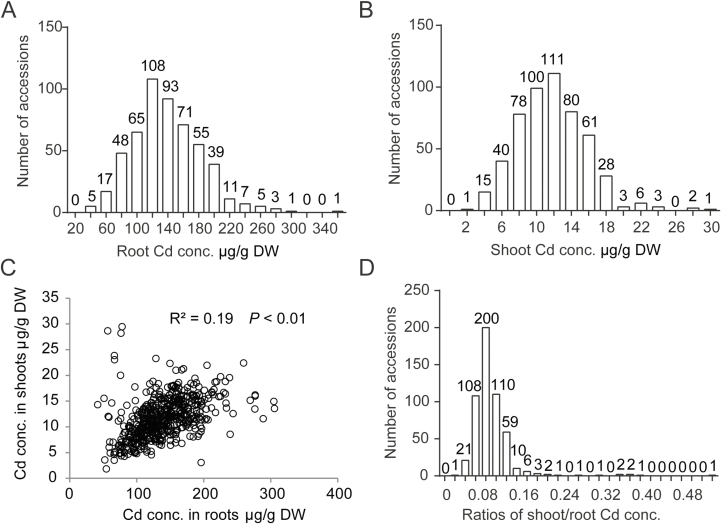

We first investigated the Cd concentration in the roots and shoots of 529 accessions grown in a hydroponic solution supplemented with 0.5 μM Cd. The root and shoot Cd concentrations ranged from 38.3 to 353.9 and from 1.8 to 29.5 µg g–1 dry weight, respectively (Fig. 1A, B). In addition, a significantly positive correlation was observed between the Cd concentrations of roots and shoots (Fig. 1C); however, the regression explained less than 20% of the variability, because the translocation factor strongly varied among cultivars. It is noteworthy that certain accessions showed extremely high levels of Cd in shoots although their root Cd concentrations were relatively low. This suggested that these accessions had high root-to-shoot Cd translocation rates (or weak barriers to transfer of Cd away from the roots) and that the process of root-to-shoot Cd translocation was an essential process in determining shoot Cd accumulation (Uraguchi et al., 2009). Interestingly, only a few accessions showed high levels of root-to-shoot Cd translocation rates, whereas the rates in most accessions were relatively low (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Variation in Cd concentrations in a diverse panel of cultivated rice. Plants were grown under normal conditions for 2 weeks and then transferred to nutrient solution supplemented with 0.5 µM Cd for an additional week. (A, B) Frequency distributions of Cd concentration in rice roots (A) and shoots (B). (C) Correlation between Cd concentrations in the shoot and root. (D) Frequency distributions of ratios of shoot/root Cd concentrations.

Eleven of the accessions in our collection showed extremely high root-to-shoot Cd translocation rates (i.e. ratio of shoot/root Cd concentration >0.20) and four additional accessions also had relatively high rates (with ratios of 0.16–0.18) (Fig. 1D). Previous studies have demonstrated that two loss-of-function alleles of OsHMA3 harboring single amino acid mutations at positions 80 (Arg to His) and 380 (Ser to Arg) caused excessive Cd accumulation in rice shoots (Ueno et al., 2010; Miyadate et al., 2011; Yan et al., 2016). We therefore analyzed the types of amino acid at these two positions in OsHMA3 in these accessions. Of the 11 cultivars with extremely high root-to-shoot Cd translocation rates, two and five had mutant alleles at position 80 and 380, respectively; the remaining four accessions with very high translocation rates and the four additional accessions with relatively high rates showed no variation at these two positions, indicating the existence of other mechanisms underlying the high root-to-shoot Cd translocation rates in these cultivars.

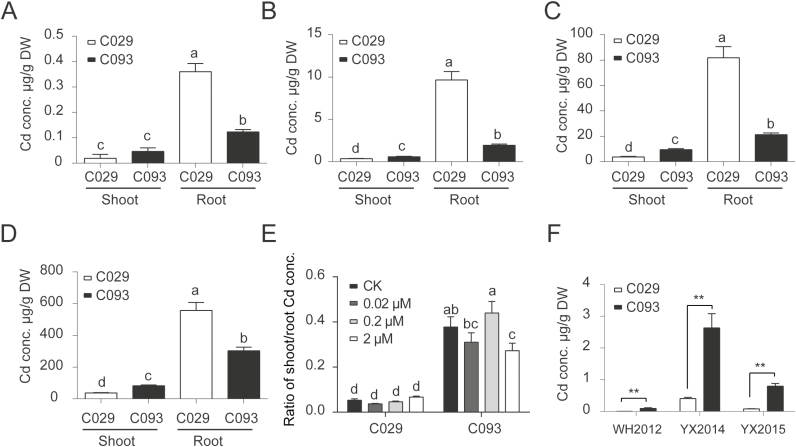

Genetic linkage analyses

In the Cd concentration gradient experiments, the Cd content was significantly higher in the shoots but lower in the roots of C093 plants grown in all three Cd concentrations than in C029 plants (Fig. 2A–E), confirming that C093 had a higher shoot/root translocation rate. In rice plants grown in two paddy fields, namely a Cd-contaminated soil at Youxian, Hunan province, and a non-contaminated soil at Wuhan, Hubei province, the grain Cd concentration significantly differed between the two parental varieties, with the brown rice (dehusked) Cd concentration in C093 being approximately 10-fold higher than in C029 (Fig. 2F); there was no consistent difference in the concentrations of other metals, including Mg, Mn, Zn, and Cu (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Cd accumulation in the two QTL parents (C029 and C093) grown under hydroponic and field conditions. (A–D) Cd concentrations in the shoots and roots of the two varieties grown in hydroponic culture without Cd supply (A), or supplied with (B) 0.02 μM, (C) 0.2 μM, or (D) 2 μM Cd. (E) Ratios of shoot/root Cd concentrations presented in A–D. (F) Cd concentrations in brown rice from plants grown in three different field conditions. WH2012 indicates that the plants were grown in a non-contaminated experimental farm in Wuhan, Hubei province, in 2012. YX2014 and YX2015 indicate that the plants were cultivated in a Cd-contaminated experimental farm in Youxian, Hunan province, in 2014 and 2015, respectively. Data shown are means ±SD of three biological replicates; the roots, shoots, or brown rice of three plants were aggregated for one replicate. Means with different letters are significantly different at P<0.05 (one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test). ** Significant differences (P<0.01) between varieties C029 and C093.

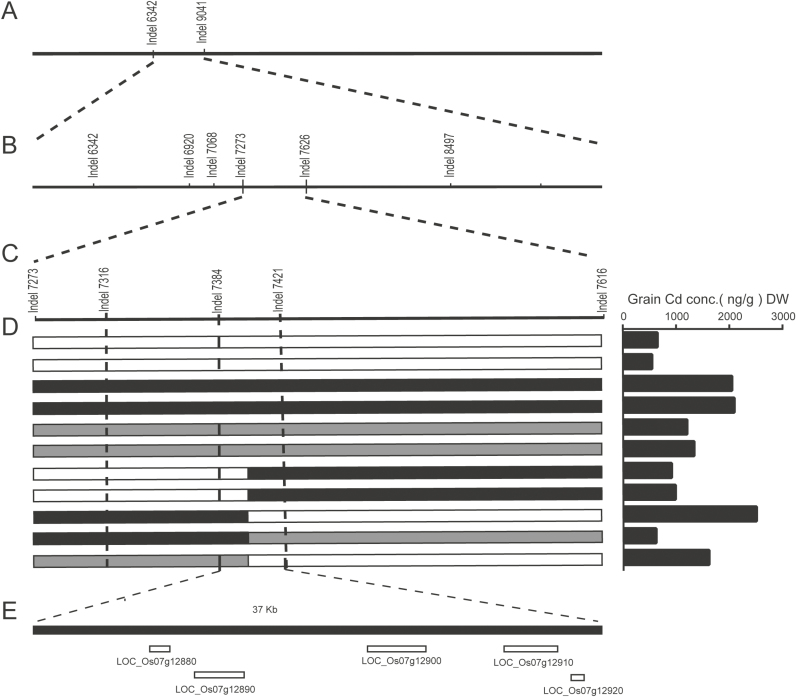

An F2 population was then generated from a cross between varieties C029 and C093. To facilitate phenotypic analysis, we planted the F2 population in the Cd-contaminated soil at Youxian and investigated the Cd accumulation in brown rice. The Cd concentrations in the F2 population showed a continuous distribution and varied considerably (ranging from 22 to 1935 ng g–1 dry weight; Supplementary Fig. S3), suggesting that Cd accumulation at Youxian is controlled quantitatively. Therefore, we performed QTL analysis to detect the corresponding genetic factors (or chromosomal regions) involved in the variation of Cd accumulation in the F2 population. Based on the QTL analysis, we unexpectedly observed that one QTL responsible for high Cd accumulation in brown rice was located on chromosome 7. For further fine mapping of this QTL, a larger F2 population (~4400 plants) was used to achieve a higher-resolution map. The candidate genomic region of this QTL was consequently defined to ~353 kb (defined by InDel markers Indel7273 and Indel7626), and the QTL was temporarily named qGCd7.1. To further narrow the interval of this QTL, we constructed a BC2F2 population using C029 as the recurrent parent. Among 1600 BC2F2 plants, five plants showing recombination between markers Indel7273 and Indel7626 were obtained. Using four newly developed InDel makers within this region, qGCd7.1 was finally defined to a 37 kb genomic region, using the markers Indel7384 and Indel7421 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fine mapping of qGCd7.1. (A) A QTL gene for Cd accumulation was mapped on chromosome 7 between markers Indel6342 and Indel9041. (B) qGCd7.1 was delimited to a region between markers Indel7273 and Indel7626 based on examination of 4400 F2 plants. (C) A total of 1600 segregating individuals derived from a BC2F2 population were used for mapping at finer resolution. (D) Genotyping and phenotyping of recombinants delimited qGCd7.1 to within a 37 kb region flanked by Indel7384 and Indel7421. White, black, and grey bars indicate homozygous C029, homozygous C093, and heterozygous alleles, respectively. The grain Cd concentrations were phenotyped for QTL analysis. (E) The Rice Genome Annotation Project predicted five genes in the target region.

Identification of the candidate gene for qGCd7.1

The Rice Annotation Database (http://rapdb.dna.affrc.go.jp) predicts five genes that lie within the genomic region defined by markers Indel7384 and Indel7421; these are LOC_Os07g12880, LOC_Os07g12890, LOC_Os07g12900, LOC_Os07g12910, and LOC_Os07g12920, which encode a putative transposon protein, a metal transporter (known as OsZIP8), a cadmium/zinc-transporting ATPase (known as OsHMA3), a PHD finger protein, and an unknown protein, respectively. According to previous studies, OsZIP8 and three other genes (except OsHMA3) were not reliable candidates for Cd translocation (Ueno et al., 2010; Miyadate et al., 2011); therefore, OsHMA3 was the most likely candidate gene for qGCd7.1.

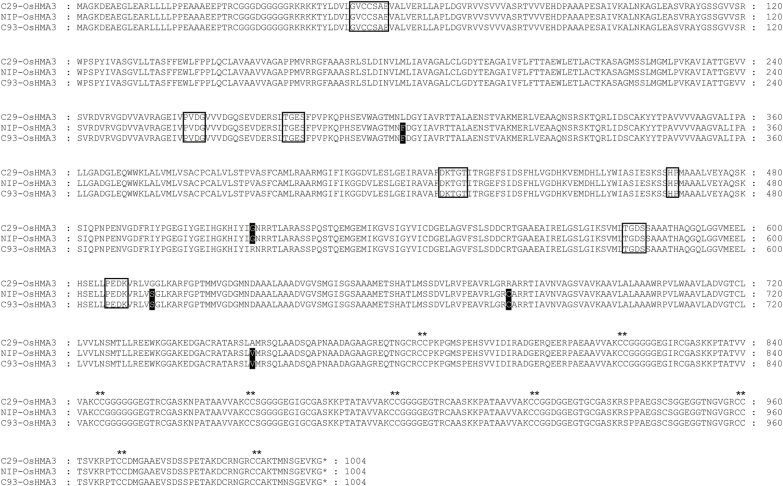

To confirm whether OsHMA3 is the true candidate for qGCd7.1 and responsible for the difference in Cd translocation rate between the parental cultivars C029 and C093, we sequenced the complete promoter and coding sequence of this gene isolated from these two varieties. As Nipponbare has been demonstrated to harbor a functional OsHMA3, the OsHMA3 sequence from Nipponbare was used as a reference. Within the OsHMA3 coding sequence, C029 and C093 showed in total 10 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), which led to five amino acid variations at positions 299, 512, 614, 678, and 752 (Fig. 4). These variations were also observed between the parent (i.e. C029 or C093) and Nipponbare. Of the five amino acid variations, four (except for the one at position 512) existed between C029 and Nipponbare, and only the mutation at position 512 (Gly to Arg substitution) was observed between C093 and Nipponbare. Within the 3 kb promoter region, a few variations (i.e. SNPs and InDels) were also observed between C029 and C093 (Supplementary Table S3).

Fig. 4.

Alignment of OsHAM3 amino acid sequences from Nipponbare, C029, and C093 rice. Black boxes indicate amino acid substitutions. Open boxes indicate motifs essential for P1B-ATPase (Baxter et al., 2003). Asterisks indicate cysteine pairs in the C-terminal region.

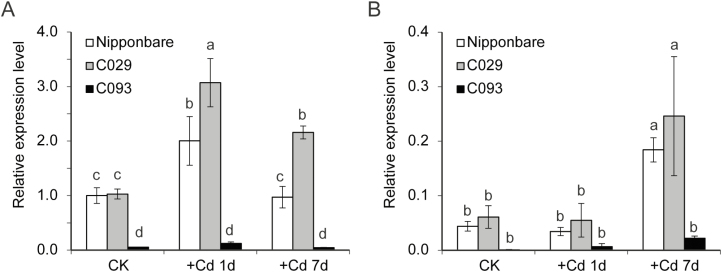

Expression levels of OsHMA3 in parental cultivars and functional analysis in yeast of different OsHMA3 alleles

Considering that cultivars C029 and C093 showed differences in the promoter sequence, the expression levels of OsHMA3 in these two varieties were investigated. Interestingly, C093, which had a high ratio of shoot/root Cd concentrations, showed a considerably lower level of OsHMA3 expression in the root, under both normal and Cd-treated conditions, than both C029 and Nipponbare (Fig. 5), consistent with the role of OsHMA3 as a barrier to root-to-shoot Cd translocation.

Fig. 5.

Expression of OsHMA3 in C029 and C093 in the presence or absence of 0.2 μM Cd. (A) Root; (B) shoot. All the expression data were calculated relative to the expression level in root of Nipponbare cultivated under control (CK) conditions. Data show means ±SD of three biological replicates; the roots or shoots of three plants were aggregated for one replicate. Means with different letters are significantly different at P<0.05 (one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test).

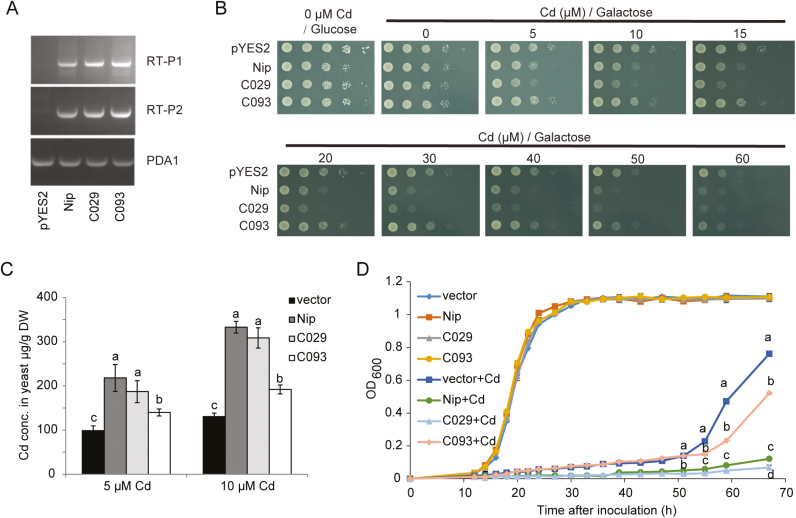

The Cd transport activities of different OsHMA3 alleles from C029, C093, and Nipponbare were analyzed using heterologous expression assays in a Cd-sensitive yeast mutant strain (Δycf1). In the presence of glucose, which repressed expression of the gene, there was no difference in Cd sensitivity among the yeast strains harboring either the vector control or different alleles of OsHMA3 (Fig. 6A, B). In the presence of galactose (which induced gene expression), the strain expressing OsHMA3 from Nipponbare and C029 showed increased sensitivity to Cd, whereas the strain expressing OsHMA3 from C093 showed similar growth to the vector control (Fig. 6B). After exposure to 5 or 10 μM Cd for 2 h, the yeast strains expressing the OsHMA3 alleles from Nipponbare or C029 accumulated significantly more Cd than the vector control and the strain expressing the allele from C093 (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, the Cd concentration in the strain expressing the allele from C093 was also higher than that in the vector control (Fig. 6C). We further monitored the growth of yeast strains expressing different OsHMA3 alleles with or without Cd treatment. In the absence of Cd, the growth curves of the different yeast strains did not differ (Fig. 6D). In the presence of Cd, the degree of growth inhibition of cells harboring the OsHMA3 allele from C093 was significantly smaller than that of cells harboring the OsHMA3 allele from C029 or Nipponbare, but slightly higher than that of cells carrying the empty vector (Fig. 6D). This phenomenon was further confirmed by yeast growth experiments performed at different concentrations of exogenous Cd supply (Supplementary Fig. S4). Previous studies have explained that the increased Cd sensitivity in yeast cells expressing a functional OsHMA3 is due to mislocalization of OsHMA3 in yeast cells (Ueno et al., 2010; Yan et al., 2016). This was confirmed by expressing fusion proteins of eGFP with different OsHMA3 alleles in yeast (Supplementary Fig. S5). In all cases, the OsHMA3 proteins appeared to be localized to the endoplasmic reticulum rather than the tonoplast in yeast cells. These results indicated that, similar to Nipponbare, C029 harbored a functional OsHMA3 allele, whereas the OsHMA3 from C093 possibly encodes a Cd transporter with weak activity.

Fig. 6.

Heterologous expression of different OsHMA3 haplotypes in yeast. (A) Expression of OsHMA3 in yeast strains revealed by reverse transcription–PCR. The yeast PDA1 gene was used as an internal control. RT-P1 and RT-P2 are two different fragments within the OsHMA3 coding region. Twenty-five PCR cycles were performed for PDA1, and 35 PCR cycles were used for OsHMA3 fragments. (B) Growth of yeast strains carrying the empty vector pYES2 or different alleles of OsHMA3 on SD-Ura plates containing different Cd concentrations in the presence of glucose or galactose. (C) Determination of Cd concentrations in yeast cells expressing the empty vector or different OsHMA3 alleles after exposure to 5 or 10 μM Cd for 2 h. (D) Growth curves of yeast cells expressing different alleles of OsHMA3 or empty vector in liquid SD-Ura medium with or without 20 μΜ CdSO4. Data are means ±SD of three biological replicates. Means with different letters are significantly different at P<0.05 (one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test).

Analysis of co-segregation between the OsHMA3 haplotypes and high Cd accumulation

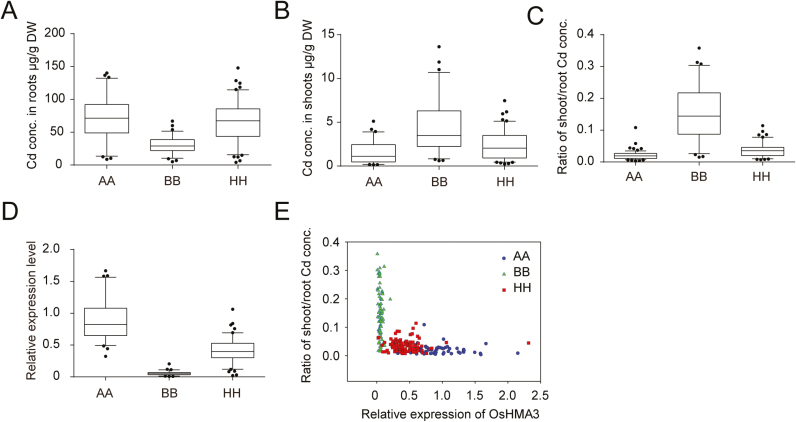

To further confirm that OsHMA3 was the causal gene for the high rate of root-to-shoot Cd translocation in C093, a BC2F3 population consisting of 239 plants was used to investigate the co-segregation between the OsHMA3 haplotypes and phenotypic variance. As qGCd7.1 was ultimately defined by Indel7384 and Indel7421, the genomic region of OsHMA3 in the 239 BC2F3 plants was genotyped using these two markers. Of the 239 plants, 64 and 70 were homozygous at this interval and their genotypes were identical to those of cultivars C029 and C093, respectively; therefore, these plants were referred to as types AA and BB. The remaining 105 plants were heterozygous at this interval and consequently were grouped as the HH type. Subsequently, we analyzed the Cd concentrations in roots and shoots and their ratios, and the expression levels of OsHMA3, in these recombinant plants (Fig. 7A–D). Consistent with the performance of the two parental cultivars, the BB-type plants showed considerably lower levels of OsHMA3 transcription than the AA-type plants, as well as the HH-type plants (Fig. 7D). Interestingly, the levels of OsHMA3 transcripts in the heterozygotes were generally half those in the AA-type plants (Fig. 7D). In contrast to these transcriptional variations, the BB-type plants had higher shoot/root Cd concentration ratios than the AA- and HH-type plants (Fig. 7C–E), suggesting a strong negative correlation between the levels of OsHMA3 transcription and the rates of Cd root-to-shoot translocation, and confirming that the OsHMA3 haplotypes co-segregated with the phenotypes.

Fig. 7.

Co-segregation analysis between genotypes and phenotypes of OsHMA3 in BC2F3 plants. (A–D) Box plots for root (A) and shoot (B) Cd concentrations, ratio of shoot/root Cd concentrations (C), and expression levels of OsHMA3 (D) in the different genotypes. Box plots represent the interquartile range, the line in the middle of each box represents the median, the whiskers represent 1.5 times the interquartile range, and the dots represent outlier points. The correlation of expression levels of OsHMA3 and ratios of shoot/root Cd concentrations was based on the 239 BC2F3 individuals (E). Different colors in E indicated different genotypes. AA, Plants with identical genotype to parental cultivar C029; BB, plants with identical genotype to parental cultivar C093; HH, heterozygous plants.

Analysis of variation in OsHMA3 in cultivars with high Cd translocation rates

We further investigated the amino acid sequences of OsHMA3 from the remaining cultivars (besides C093) showing extremely high rates of root-to-shoot Cd translocation. As observed in C093, two more temperate japonica cultivars (C130 and C187) harbored only one amino acid difference compared with Nipponbare, replacing Gly with Arg at amino acid position 512 (Table 1). It is noteworthy that the variety W125, which showed a high ratio of root-to-shoot Cd translocation (~0.269), had an identical OsHMA3 coding sequence to that of Nipponbare.

Table 1.

Information on cultivars with high ratios of shoot/root Cd concentrations in this collection and their causal variations

| Accession ID | Serial number in this population | Name | Population | Mean shoot Cd (μg g–1) | Mean root Cd (μg g–1) | Mean shoot/root Cd ratio | Causal variation a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C130 | 130 | Xiangnuo | TeJ | 28.65 | 56.82 | 0.513 | 512 |

| C093 | 93 | Magunuo | TeJ | 29.46 | 78.34 | 0.378 | 512 |

| W280 | 483 | Sada solay | Aus | 28.18 | 76.55 | 0.367 | 80 |

| C187 | 187 | Niankenuo | TeJ | 23.83 | 66.63 | 0.350 | 512 |

| C035 | 35 | Yelicanghua | TeJ | 23.04 | 67.06 | 0.349 | 380 |

| W099 | 302 | SL 22–620 | Aus | 14.29 | 41.94 | 0.342 | 80 |

| C023 | 23 | Funingzipi | TeJ | 15.52 | 51.34 | 0.309 | 380 |

| W125 | 328 | Yong Chal Byo | Int | 20.02 | 75.91 | 0.269 | ? |

| C017 | 17 | AnnongwanjingB | TeJ | 14.62 | 62.84 | 0.221 | 380 |

| C177 | 177 | Maguzi | TeJ | 12.04 | 57.42 | 0.209 | 380 |

| W018 | 221 | UZ ROSZ M38 | TeJ | 11.88 | 58.70 | 0.203 | 380 |

| W252 | 455 | SADRI RICE 1 | VI | 17.74 | 97.37 | 0.179 | ? |

| C002 | 2 | Dom Sufid | VI | 23.26 | 128.75 | 0.178 | ? |

| W133 | 336 | TD 70 | Ind | 12.81 | 77.05 | 0.172 | ? |

| W014 | 217 | Red Khosha Cerma | VI | 14.19 | 85.40 | 0.167 | ? |

Ind, indica intermediates; Int, intermediates; TeJ, temperate japonica.

a Data indicate the variant amino acid position in OsHMA3. ?, Unknown cause (might not be caused by variation in OsHMA3).

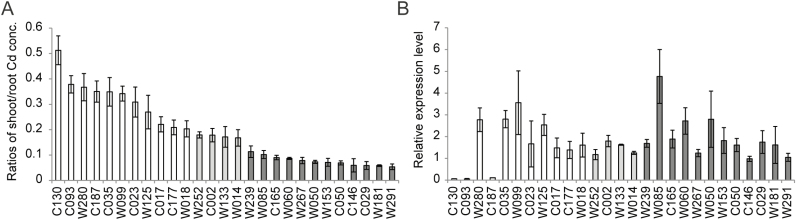

To further investigate the expression levels of OsHMA3 from the cultivars with high Cd transfer rates as well as from the general cultivars, all 15 cultivars with high Cd transfer rates and 12 other randomly selected cultivars (including Nipponbare as a reference) from the diverse panel were used (Fig. 8A). Interestingly, all three varieties with a substitution at amino acid position 512 expressed lower levels of OsHMA3 transcripts than the other cultivars (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Variation in OsHMA3 expression levels in the varieties with high ratios of shoot/root Cd concentrations and a random selection of normal varieties. (A) Ratios of shoot/root Cd concentrations for the selected varieties. (B) Expression levels of OsHMA3 in roots of 4-week-old seedlings of the selected varieties. In A, the varieties are arranged in order from large to small ratios; they are presented in the same order in B. Accession number C146 is Nipponbare. White bars represent the 11 varieties with extremely high ratios of shoot/root Cd concentrations; light grey bars represent the additional three varieties with high ratios of shoot/root Cd concentrations; dark grey bars indicate the 12 selected normal varieties. Data represent the means ±SD of three biological replicates; the roots or shoots of three plants were aggregated for one replicate.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that the accumulation of Cd in various populations of cultivated rice varies significantly (Arao and Ae, 2003; Pinson et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2018), although the molecular mechanism is still not completely understood. The high Cd accumulation in a few varieties examined in this study was caused by single amino acid substitutions in the coding sequence of OsHMA3 at position 80 (Arg to His) or 380 (Ser to Arg) (Ueno et al., 2010; Miyadate et al., 2011; Yan et al., 2016). The substitutions at these two positions generally occurred in different rice subpopulations. Of the 529 rice accessions used in this study, two were found to harbor the substitution at position 80, and five at position 380, as well as showing high Cd accumulation in the shoots and grains. In the present study, we also identified a new weak allele of OsHMA3 involving a substitution at amino acid position 512, but with no substitution at either position 80 or position 380. This new allele was identified based on a fine QTL mapping in a BC2F2 population and was demonstrated to be the causal gene of a major QTL responsible for a high root-to-shoot Cd translocation rate in the parent variety C093 as well as in this rice population (Fig. 3). Further sequence analysis revealed that this new allele harbored only a single SNP in the coding sequence, which led to a Gly to Arg substitution at amino acid position 512 compared with the functional allele represented by OsHMA3 of Nipponbare (Fig. 4). Heterologous expression in the Cd-sensitive yeast mutant Δycf1 showed that this new allele had lost most of its Cd transport activity, resulting in Cd sensitivity similar to that of the empty vector control, whereas the positive control harboring a functional OsHMA3 allele from Nipponbare showed higher sensitivity to Cd (Fig. 6). The functional allele of OsHMA3, causing more sensitivity than tolerance to Cd in yeast, has been previously shown to be attributed to mislocalization of OsHMA3 in yeast (Ueno et al., 2010). Further evidence for this new allele leading to high root-to-shoot Cd translocation rate in rice was that two other temperate japonica cultivars harboring the new OsHMA3 allele (other than the C093 variety) also showed high shoot/root Cd concentration ratios (Table 1).

Previous studies have demonstrated that HMA3 controls the Cd variations of both rice and Arabidopsis mainly via amino acid polymorphisms in the protein sequence Ueno et al., 2010; Chao et al., 2012). In this study, we observed that the expression of OsHMA3 also varied among the cultivars. The new OsHMA3 allele (i.e. mutation at position 512) was expressed at a lower level in the three cultivars harboring this allele than the functional allele in Nipponbare and other cultivars (Fig. 8). However, no common SNP or InDel was detected within the ~3 kb promoter region of OsHMA3 in these three cultivars compared with the corresponding region in Nipponbare (Supplementary Table S3). This indicated that the causal variation resulting in the reduced expression level of OsHMA3 in these three cultivars might lie outside this promoter region. As the new OsHMA3 allele appeared to still possess some weak Cd transport activity (Fig. 6), the reduction in OsHMA3 expression could further weaken the function of this allele. Interestingly, a recent study showed that the two OsHMA3 alleles previously identified as loss-of-function owing to variations at the amino acid positions 80 and 380 were also weak alleles (Sui et al., 2019). Possibly owing to the double negative effects at the transcriptional and protein levels, the new allele identified here presented weaker function than the two previously identified alleles, and therefore resulted in a higher shoot/root Cd concentration ratio (Table 1). Sui et al. (2019) also reported a new total loss-of-function allele of OsHMA3, which is caused by a deletion of 14 amino acid residues; however, this allele was not identified in our collection, indicating its rarity in rice cultivars.

A gene dosage effect for the functional OsHMA3 allele was observed, based on differences in the performance of the homozygotes and heterozygotes of OsHMA3 in terms of Cd accumulation and in gene expression levels (Fig 7), indicating that the effect of functional OsHMA3 should be highly associated with its expression levels, even when the changes in expression levels were minor. Interestingly, the cultivars other than the three harboring the new allele also showed differences in OsHMA3 expression levels (Fig 8); however, possibly due to the small number of cultivars used, we did not observe any correlation between OsHMA3 transcripts and Cd levels. The variations in the expression of OsHMA3 in the entire collection, as well as their association with Cd accumulation, should be investigated in future studies.

Of the 529 varieties we studied, 11 showed extremely high shoot/root Cd concentration ratios (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. S6). Of these 11 varieties, 10 were caused by the three different types of HMA3 weak allele, with two, five, and three being caused by an amino acid substitution in OsHMA3 at position 80, 380, and 512, respectively. The remaining cultivar, W125, did not show functional variations in OsHMA3 at the mRNA or protein levels, indicating that, in addition to OsHMA3, at least one other gene also controls the variation in Cd translocation. Further efforts will be needed to identify the molecular mechanism controlling the high rate of transfer of Cd from root to shoot in W125. Interestingly, the 11 cultivars showing high ratios of shoot/root Cd concentrations comprised eight temperate japonica varieties, two Aus, and one intermediate type, but no indica variety. In fact, three indica rice varieties (Anjana Dhan, Cho-Ko-Koku, and Jarjan), which were not included in this collection, have been reported to harbor an amino acid substitution at position 80 in OsHMA3 as well as high Cd accumulation (Ueno et al., 2010; Miyadate et al., 2011; Ueno et al., 2011). Nevertheless, the proportion of varieties with high shoot/root Cd ratios in indica was lower than that in japonica, although these type varieties in both subpopulations are actually rare. However, according to previous studies, varieties of rice showing high Cd in the grains appeared to be more common in indica than in japonica (Arao and Ae, 2003; Uraguchi and Fujiwara, 2013). In this study, apart from the remarkable ability of the specific cultivars mentioned above to transfer Cd from root to shoot, the general cultivars of indica and japonica showed no significant differences in root Cd concentrations, although the shoot Cd and the shoot/root Cd ratios in indica were significantly higher than those in japonica (Supplementary Fig. S7), indicating a higher root-to-shoot transfer rate in indica than in japonica. Furthermore, in our previous field experiments (Yang et al., 2018), the median grain Cd concentration in indica at the maturation stage was significantly higher than that in japonica, as expected, but the shoot Cd concentration in indica was lower than or similar to that in japonica. Together, these findings indicated that the higher Cd accumulation in indica grain may be due to higher rates of Cd transfer, but not Cd uptake, in indica rice plants than in japonica. A recent study showed that the differential Cd transfer rates between indica and japonica rice may be attributed to mild variations in OsHMA3 expression levels (Liu et al., 2019).

In conclusion, we investigated the variation in root-to-shoot Cd translocation rates in a diverse rice population and identified a new weak allele of OsHMA3 that was different from those reported previously, which caused a few new japonica cultivars to accumulate large amounts of Cd in the shoots and grains. We also comprehensively analyzed the distribution of all three weak alleles of OsHMA3 in the diverse population, which will allow these genotypes or cultivars to be avoided when breeding low-Cd rice. The presence of multiple weak or loss-of-function alleles of OsHMA3 also provides new insights for the study of homologous genes in other species.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Fig. S1. Comparison of the Cd concentrations in rice roots washed with distilled water or 5 mM CaCl2.

Fig. S2. Accumulation of Mg, Mn, Zn, and Cu in brown rice varieties C029 and C093 grown under field conditions.

Fig. S3. Distribution of Cd concentrations in 274 F2 individuals of brown rice grown in a Cd-contaminated experimental farm in Youxian, Hunan province.

Fig. S4. Growth curves of yeast cells expressing different alleles of OsHMA3 or empty vector (pYES2) in liquid SD-Ura medium with different concentrations of Cd.

Fig. S5. Subcellular localization of eGFP:OsHMA3 in yeast.

Fig. S6. Comparison of Cd accumulation between the 11 varieties with extremely high ratios of shoot/root Cd concentrations and other varieties in this collection.

Fig. S7. Difference in Cd accumulation between indica and japonica in the general cultivars (excluding the 11 varieties with extremely high ratios of shoot/root Cd concentrations).

Table S1. Information regarding the 529 accessions used in this study.

Table S2. Primers used in the present study.

Table S3. Differences in OsHMA3 promoter sequences (~ 3 kb) from different rice cultivars.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31600194, 31821005, and 31520103914), the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (2014AA10A603), and the Gates Foundation.

References

- Arao T, Ae N. 2003. Genotypic variations in cadmium levels of rice grain. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 49, 473–479. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter I, Tchieu J, Sussman MR, Boutry M, Palmgren MG, Gribskov M, Harper JF, Axelsen KB. 2003. Genomic comparison of P-type ATPase ion pumps in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Physiology 132, 618–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao DY, Silva A, Baxter I, Huang YS, Nordborg M, Danku J, Lahner B, Yakubova E, Salt DE. 2012. Genome-wide association studies identify heavy metal ATPase3 as the primary determinant of natural variation in leaf cadmium in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genetics 8, e1002923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Gao Y, Xie W, et al. 2014. Genome-wide association analyses provide genetic and biochemical insights into natural variation in rice metabolism. Nature Genetics 46, 714–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng F, Zhao N, Xu H, Li Y, Zhang W, Zhu Z, Chen M. 2006. Cadmium and lead contamination in japonica rice grains and its variation among the different locations in southeast China. Science of the Total Environment 359, 156–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S, Ma JF. 2016. Toxic heavy metal and metalloid accumulation in crop plants and foods. Annual Review of Plant Biology 67, 489–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curie C, Alonso JM, Le Jean M, Ecker JR, Briat JF. 2000. Involvement of NRAMP1 from Arabidopsis thaliana in iron transport. Biochemical Journal 347 Pt 3, 749–755. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa S, Ishimaru Y, Igura M, Kuramata M, Abe T, Senoura T, Hase Y, Arao T, Nishizawa NK, Nakanishi H. 2012. Ion-beam irradiation, gene identification, and marker-assisted breeding in the development of low-cadmium rice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 109, 19166–19171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y, Suzuki M, Tsukamoto T, et al. 2006. Rice plants take up iron as an Fe3+-phytosiderophore and as Fe2+. The Plant Journal 45, 335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y, Takahashi R, Bashir K, et al. 2012. Characterizing the role of rice NRAMP5 in manganese, iron and cadmium transport. Scientific Reports 2, 286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Chen G, Li Y, et al. 2017. Characterization of a major QTL for manganese accumulation in rice grain. Scientific Reports 7, 17704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CL, Gao ZY, Shang LG, Yang CH, Ruan BP, Zeng DL, Guo LB, Zhao FJ, Huang CF, Qian Q. 2019. Natural variation in the promoter of OsHMA3 contributes to differential grain cadmium accumulation between Indica and Japonica rice. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo JS, Huang J, Zeng DL, et al. 2018. A defensin-like protein drives cadmium efflux and allocation in rice. Nature Communications 9, 645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyadate H, Adachi S, Hiraizumi A, et al. 2011. OsHMA3, a P1B-type of ATPase affects root-to-shoot cadmium translocation in rice by mediating efflux into vacuoles. New Phytologist 189, 190–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi H, Ogawa I, Ishimaru Y, Mori S, Nishizawa NK.. 2006. Iron deficiency enhances cadmium uptake and translocation mediated by the Fe2+ transporters OsIRT1 and OsIRT2 in rice. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 52, 464–469. [Google Scholar]

- Nawrot T, Plusquin M, Hogervorst J, Roels HA, Celis H, Thijs L, Vangronsveld J, Van Hecke E, Staessen JA. 2006. Environmental exposure to cadmium and risk of cancer: a prospective population-based study. Lancet Oncology 7, 119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinson SRM, Tarpley L, Yan W, Yeater K, Lahner B, Yakubova E, Huang XY, Zhang M, Guerinot ML, Salt DE. 2015. Worldwide genetic diversity for mineral element concentrations in rice grain. Crop Science 55, 294–311. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A, Yamaji N, Ma JF. 2014. Overexpression of OsHMA3 enhances Cd tolerance and expression of Zn transporter genes in rice. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 6013–6021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A, Yamaji N, Yokosho K, Ma JF. 2012. Nramp5 is a major transporter responsible for manganese and cadmium uptake in rice. The Plant Cell 24, 2155–2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh-Nagasawa N, Mori M, Nakazawa N, Kawamoto T, Nagato Y, Sakurai K, Takahashi H, Watanabe A, Akagi H. 2012. Mutations in rice (Oryza sativa) heavy metal ATPase 2 (OsHMA2) restrict the translocation of zinc and cadmium. Plant & Cell Physiology 53, 213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao JF, Xia J, Yamaji N, Shen RF, Ma JF. 2018. Effective reduction of cadmium accumulation in rice grain by expressing OsHMA3 under the control of the OsHMA2 promoter. Journal of Experimental Botany 69, 2743–2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui F, Zhao D, Zhu H, Gong Y, Tang Z, Huang XY, Zhang G, Zhao FJ. 2019. Map-based cloning of a new total loss-of-function allele of OsHMA3 causes high cadmium accumulation in rice grain. Journal of Experimental Botany 70, 2857–2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R, Ishimaru Y, Senoura T, Shimo H, Ishikawa S, Arao T, Nakanishi H, Nishizawa NK. 2011. The OsNRAMP1 iron transporter is involved in Cd accumulation in rice. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 4843–4850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R, Ishimaru Y, Shimo H, Ogo Y, Senoura T, Nishizawa NK, Nakanishi H. 2012. The OsHMA2 transporter is involved in root-to-shoot translocation of Zn and Cd in rice. Plant, Cell & Environment 35, 1948–1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno D, Koyama E, Yamaji N, Ma JF. 2011. Physiological, genetic, and molecular characterization of a high-Cd-accumulating rice cultivar, Jarjan. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 2265–2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno D, Yamaji N, Kono I, Huang CF, Ando T, Yano M, Ma JF. 2010. Gene limiting cadmium accumulation in rice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 107, 16500–16505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uraguchi S, Fujiwara T. 2013. Rice breaks ground for cadmium-free cereals. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 16, 328–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uraguchi S, Kamiya T, Sakamoto T, Kasai K, Sato Y, Nagamura Y, Yoshida A, Kyozuka J, Ishikawa S, Fujiwara T. 2011. Low-affinity cation transporter (OsLCT1) regulates cadmium transport into rice grains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 108, 20959–20964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uraguchi S, Mori S, Kuramata M, Kawasaki A, Arao T, Ishikawa S. 2009. Root-to-shoot Cd translocation via the xylem is the major process determining shoot and grain cadmium accumulation in rice. Journal of Experimental Botany 60, 2677–2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Shimbo S, Nakatsuka H, Koizumi A, Higashikawa K, Matsuda-Inoguchi N, Ikeda M. 2004. Gender-related difference, geographical variation and time trend in dietary cadmium intake in Japan. Science of the Total Environment 329, 17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji N, Ma JF. 2014. The node, a hub for mineral nutrient distribution in graminaceous plants. Trends in Plant Science 19, 556–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji N, Xia J, Mitani-Ueno N, Yokosho K, Feng Ma J. 2013. Preferential delivery of zinc to developing tissues in rice is mediated by P-type heavy metal ATPase OsHMA2. Plant Physiology 162, 927–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Wang P, Wang P, Yang M, Lian X, Tang Z, Huang CF, Salt DE, Zhao FJ. 2016. A loss-of-function allele of OsHMA3 associated with high cadmium accumulation in shoots and grain of Japonica rice cultivars. Plant, Cell & Environment 39, 1941–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Lu K, Zhao FJ, et al. 2018. Genome-wide association studies reveal the genetic basis of ionomic variation in rice. The Plant Cell 30, 2720–2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Zhang Y, Zhang L, et al. 2014. OsNRAMP5 contributes to manganese translocation and distribution in rice shoots. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 4849–4861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Forno DA, Cock JH, Gomez KA. 1976. Laboratory manual for physiological studies of rice, 3rd edn Manila: International Rice Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Yao W, Ouyang Y, Yang W, Wang G, Lian X, Xing Y, Chen L, Xie W. 2015. RiceVarMap: a comprehensive database of rice genomic variations. Nucleic Acids Research 43, D1018–D1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.