Abstract

4H-Pyrans (4H-Pys) and 1,4-dihydropyridines (1,4-DHPs) are important classes of heterocyclic scaffolds in medicinal chemistry. Herein, an indium(III)-catalyzed one-pot domino reaction for the synthesis of highly functionalized 4H-Pys, and a model of 1,4-DHP is reported. This alternative approach to the challenging Hantzsch 4-component reaction enables the synthesis of fused-tricyclic heterocycles, and the mechanistic studies underline the importance of an intercepted-Knoevenagel adduct to achieve higher chemoselectivity towards these types of unsymmetrical heterocycles.

Keywords: Intercepted-Knoevenagel condensation, Multicomponent reaction, 4H-pyrans, Domino reaction, Hydrogen-bond network

1. Introduction

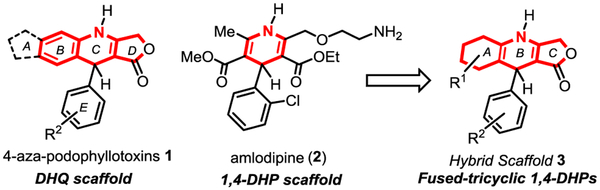

Etoposide (Vepesid®), a synthetic glycosylated derivative from the heterolignan natural product podophyllotoxin, is commonly used in cancer chemotherapy [1]. Other analogs such as the 4-aza-podophyllotoxins 1 have also shown important biological activity as antimitotic and vascular-disrupting agents (Fig. 1). We recently reported the synthesis of a library of potent 4-aza-podophyllotoxins from which several hits have emerged with a selective biological activity profile against leukemia [2]. While the cytotoxicity of the dihydroquinoline (DHQ) chemotype 1 has been underlined in several other biological screenings (Servier, NCI-60) for the development of potent antimitotic compounds, the current synthetic ability to diversify this portfolio of heterocycles is limited [3]. Interestingly, some closely related heterocycles, 1,4-dihydropyridines (1,4-DHPs), proved to be excellent scaffolds to advance L-type calcium channel blockers [4] which are used clinically to treat hypertension (e.g. amlodipine 2, barnidipine and other members of the “–dipine” family) [5]. Given the significant bio-activities of both chemotypes 1 and 2, we were drawn to synthesize novel analogs built on a hybrid scaffold between DHQ and 1,4-DHP such as the fused tricyclic 1,4-dihydropyridine skeleton 3 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Biologically active chemotypes of interest.

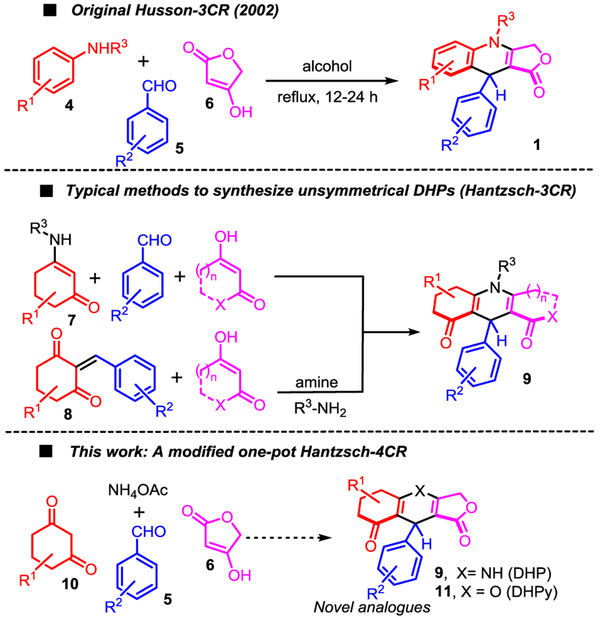

Multicomponent reactions (MCRs) are enjoying a prominent status in modern organic synthesis because they are amenable to snapping together multiple starting materials (components) into a complex molecule with outstanding atom economy in a single pot. MCRs are therefore ideal transformations to quickly generate architecturally, and functionally, diverse scaffolds for screening purposes in medicinal chemistry [6]. MCRs can only be practical and efficient if each partner has a specific reactivity, and plays an unambiguous role to react with the other components in a perfectly orchestrated fashion towards a single product. This dogma suggests that components with similar functional groups cannot effectively participate in a MCR without nurturing a problem of chemoselectivity, ultimately leading to undesirable competitive reaction pathways. For instance, the synthesis of the DHQs 1 is typically achieved via a 3-component reaction, the Husson-3CR, between an aniline 4, an aldehyde 5 and tetronic acid 6 (Scheme 1) [7]. Similarly, the Hantzsch-3CR is also a well-established MCR for the synthesis of symmetrical 1,4-dihydropyridines (1,4-DHPs) [8]. On the other hand, the efficiency and the scope of the Hantzsch-4CR towards unsymmetrical 1,4-DHP products 9 is extremely limited [9]. Seemingly, all published Hantzsch-4CRs showcase the specific use of a cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl (e.g. 10) with an acyclic alkyl acetoacetate partner. The issue of chemoselectivity between components highlights the challenge in expanding the scope of this MCR which led to the development of numerous creative solutions, typically with two of the components condensed separately prior to being engaged into a Hantzsch-3CR (e.g. β-enamino ketone 7 or Knoevenagel adduct 8, Scheme 1) [10,11].

Scheme 1.

Multicomponent reaction strategies towards 1,4- dihydroquinoline 1 and dihydropyridine 2 scaffolds.

Despite the recent advances in diastereoselective and enantioselective variants of the Hantzsch-3CR, the synthesis of unsymmetrical 1,4-DHPs 9 remains challenging [10]. Therefore, developing a Hantzsch-4CR (or a one-pot alternative) to synthesize complex fused-tricyclic 1,4-dihydropyridines [12] is an exciting endeavor that would require the discovery of a novel strategy to timely or chemoselectively introduce two, similarly reactive, cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl partners. Based on unexpected results for the Hantzsch-4CR reported herein, a mechanistic-based rationale is advanced to prepare unsymmetrical fused-tricyclic 4H-pyran (4H-Py) 11, and their 1,4-DHPs 9 counterparts. This primed us to optimize a novel domino one-pot protocol that takes advantage of an intercepted Knoevenagel condensation to access these unsymmetrical heterocycles 9/11 which could not be obtained via a direct MCR.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Attempts of a Hantzsch-4CR for the synthesis of fused-tricyclic 1,4-dihydropyridines

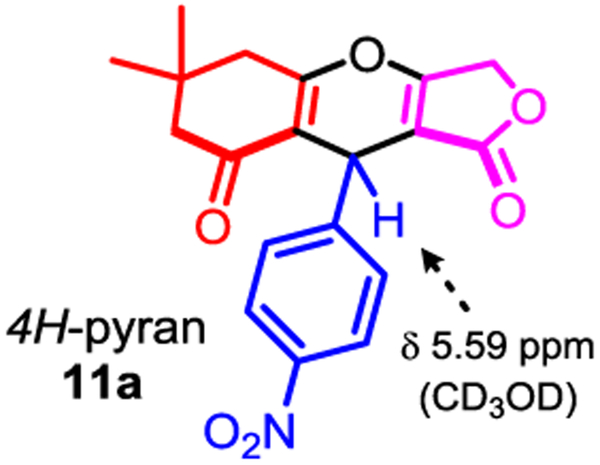

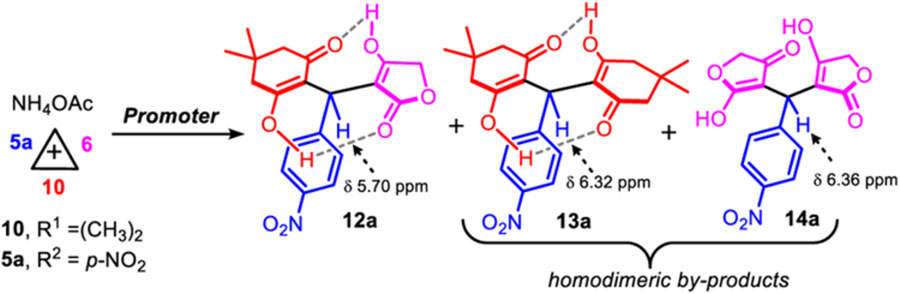

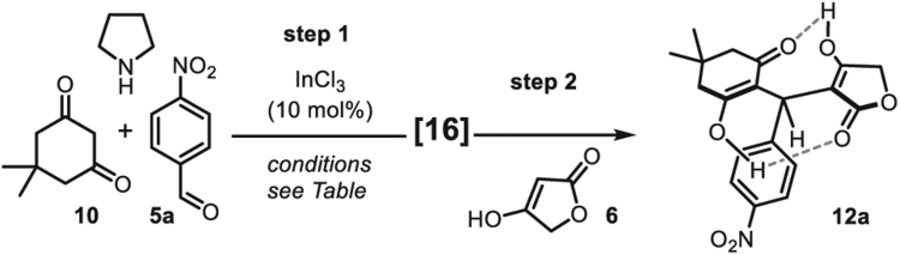

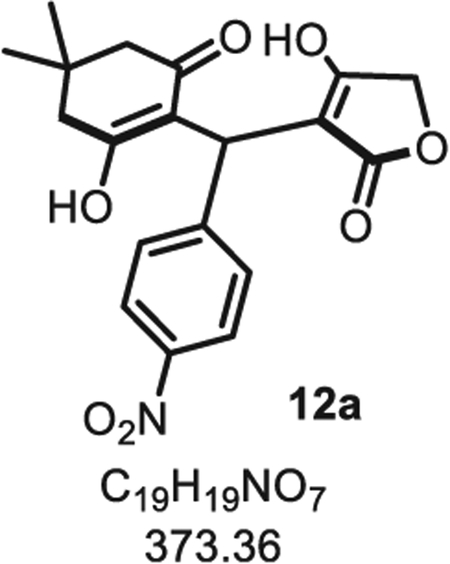

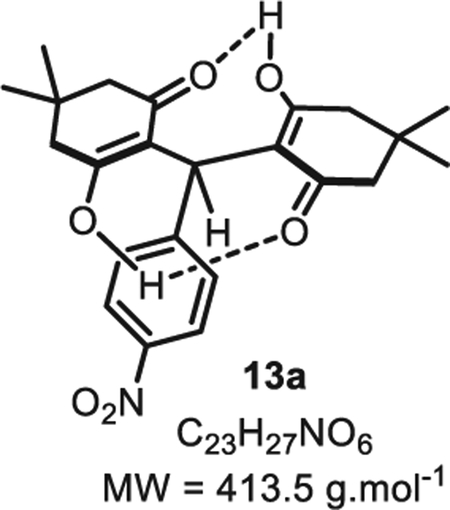

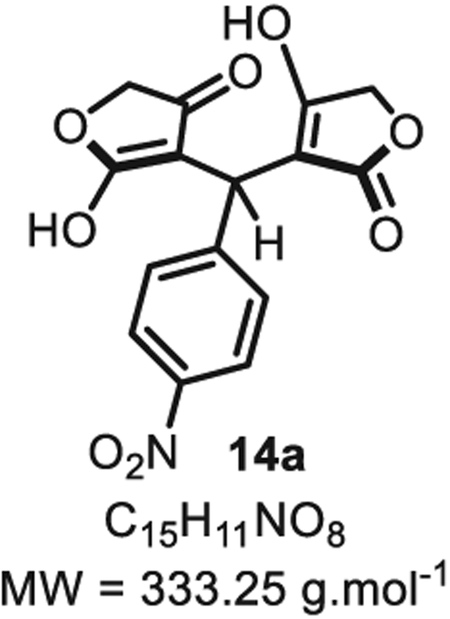

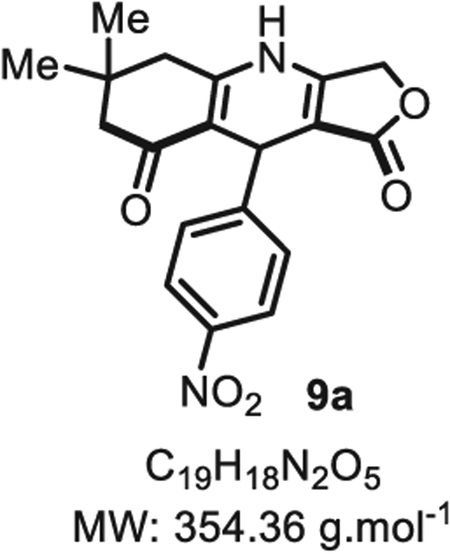

As mentioned in the scenario above, we anticipated that a Hantzsch-4CR engaging two distinct, but reactively comparable cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyls such as tetronic acid 6, and dimedone 10 may promote several competitive pathways. As model reaction, we examined the synthesis of fused-tricyclic dihydropyridine 9a in a racemic form, through the screening of established reaction conditions (Table 1) [9,13]. To identify a potential catalyst(s) that will promote an unbiased chemoselective Hantzsch-4CR orchestration, ratios between all components p-nitrobenzaldehyde 5a, tetronic acid 6, dimedone 10, and ammonium acetate were mainly kept equimolar (Table 1). Surprisingly, none of the conditions previously reported for Hantzsch-4CRs afforded any traces of the anticipated 1,4-DHP product 9a. Instead, a mixture of pseudo-symmetrical dienols 13a and 14a [14] along with the unsymmetrical dienol 12a were obtained uncyclized, without any evidence of nitrogen incorporation [15]. Secondly, only the unsymmetrical dienol 12a was found to spontaneously cyclize during the purification on (neutralized and anhydrous) silica gel or on alumina chromatography which further rendered the crude reactions’ characterization difficult. As previously stated by Sun, we found that dienol 12a (benzylic proton δ 5.71 ppm) transformed spontaneously into the corresponding 4H-pyran 11a (benzylic proton δ 5.61 ppm) on silica gel, or during any acidic workup (Fig. 2) [16b]. On the contrary, pseudo-symmetrical dienols 13a and 14a are highly stable and can be smoothly isolated (vide infra for a discussion about dienol stabilization by an intramolecular hydrogen-bond network). As shown in Table 1, dienol 12a (isolated as 11a) was obtained as the major product in most reactions, but significant amounts of pseudo-symmetrical homodimers 13a and 14a were also generated. For instance, upon simple grinding of the 4-components neat, 11a was isolated in 27% yield (entry 1) [9f]. Based off literature precedents, several reactions were evaluated in ethanol, in presence of either iodine [9a], cerium ammonium nitrate (CAN) as a catalyst [9c], or with a montmorillonite clay [9l] (entries 2–5). In comparison to the control experiment in pure ethanol (entry 2), the clay seems to have little effect on the course of the reaction and yielded the desired product 11a in 50% yield (entry 3). In contrast, the catalytic activity of CAN has a more drastic effect on the ratio of products (no dimedone dimer 13a observed), while accelerating the reaction rate to afford 11a in only 30 min and 40% yield (entry 5). Using either ytterbium or scandium triflates, as Lewis acid catalysts, product 11a was isolated in surprisingly modest yields 14% and 33% respectively (entries 6–7). [9b,9j] Acetoacetates are known bidentate ligands for Ru(III) metal, therefore a reaction with 1 mol% of RuCl3 Lewis acid was tested (entry 8). Under these conditions, the tetronic dimer 14a became the main product of the reaction, which likely indicates that a 3CR takes place around the metal center with the tetronic acid ligand henceforth extruding the dimedone partner 10 from the reaction. Given the result with CAN (entry 5), which could likely proceed through a single-electron oxidation mechanism of the 1,3-dicarbonyl, reactions with Ru(BPy)3Cl2 under blue LEDs visible-light irradiation or in the dark were attempted (entry 9), and remarkably afforded the tetronic dimer 14a as the main product (53% NMR yield).[9m] Finally, indium trichloride was also tested to catalyze this reaction in two different solvents (entries 10–11), and product 11a was preferentially synthesized in ethanol in 44% isolated yield. 1H NMR spectroscopy monitoring of the Hantzsch-4CR suggested that the major pathway might arise from a Knoevenagel adduct en route to the corresponding dienols products 12a, 13a, and 14a, which is in agreement with the results obtained by Sinha from mass spectrometry studies (ESI-MS/MS) [17]. These results might well explain why mostly biased examples of Hantzsch-4CR have been reported [9]. Taken together, these preliminary results suggest that CAN and InCl3 are the most efficient catalysts to synthesize the 4H-pyran 11a in a multicomponent fashion, and that further optimizations will be require in order to synthesize unsymmetrical 1,4-DHP products (e.g. 9a) [18].

Table 1.

Attempted Hantzsch-4CR toward fused-tricyclic dihydropyridine 9a.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Component ratio | Promoter | Solvent Time | Crude % -ratioa | % Yield (11a)b | ||

| 10 | 5a | 6 | |||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | –c | 2 h | 6 (8%); 12a (39%) 13a (25%); 14a (27%) | 27 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | EtOH, 18 h | 6 (0%); 12a (52%) 13a (17%); 14a (20%) | 40 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | montmorillonite (750 mg) | EtOH, 18 h | 6 (5%); 12a (51%) 13a (24%); 14a (20%) | 50 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | l2 (30mol%) | EtOH, 3 h | 6 (8%); 12a (26%) 13a (15%); 14a (23%) | 11 |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | CAN (5 mol %) | EtOH, 25min | 6 (11%); 12a (54%) 13a (0%); 14a (18%) | 40 |

| 6 | 1.5 | 1 | 1 | Yb (OTf)3 (10 mol%) | CH3CN, 4 h | 6 (4%); 12a (24%) 13a (0%); 14a (12%) | 14 |

| 7 | 1.5 | 1 | 1 | Sc(OTf)3(10 mol%) | CH3CN, 4 h | 6 (4%); 12a (24%) 13a (0%); 14a (15%) | 33 |

| 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | RuCl3 (1 mol %) | CH3CN, 3 h | 6 (0%); 12a (27%) 13a (26%); 14a (47%) | n.de |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Ru(BPy)3Cl2 (1 mol%)d | CH3CN, 3 h | 6 (0%); 12a (33%) 13a (14%); 14a (53%) | n.d. |

| 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | lnCl3 (10 mol%) | CH3CN, 5 h | 6 (0%); 12a (35%) 13a (17%); 14a (38%) | n.d. |

| 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | lnCl3 (10 mol%) | EtOH, 20 h | 6 (0%); 12a (50%) 13a (15%); 14a (28%) | 44 |

Reactions were conducted on 1.0 mmol of NH4OAc at room temperature and %-ratios were calculated from crude 1H NMR using signals indicated on the schematic (benzylic protons chemical shifts reported are in CD3OD).

Due to the unavoidable transformation of 12a into 11a on silica gel, the isolated yields of analytically pure product 11a are reported.

Reaction promoted by grinding the 4 components neat.

Similar results were obtained under blue LED-irradiation or in the dark as control which demonstrates that no visible-light photocatalysis is taking place.

The reaction yield was not determined because the major product was the undesired homodimer 14a.

Fig. 2.

Isolated Product 11a from the attempted Hantzsch-4CR.

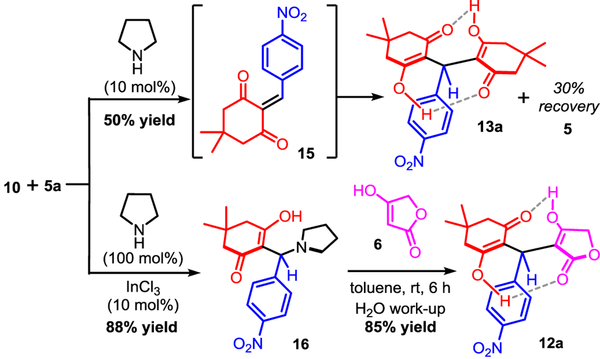

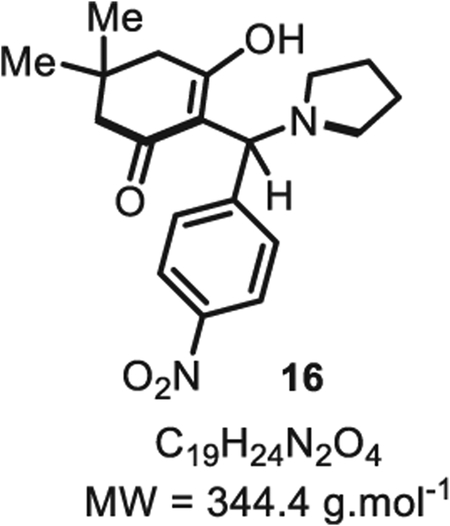

2.2. Discovery and reactivity of the Intercepted-Knoevenagel adduct 16 towards unsymmetrical products

To further probe the mechanism of this multicomponent reaction– which did not incorporate ammonia– we studied reactions of p-nitrobenzaldehyde 5a with tetronic acid 6 and dimedone 10 separately. It was found that 10 reacts more rapidly with 5a to deliver the pseudo-symmetrical homodimer 13a (Scheme 2). This reaction was found to be cleaner and faster upon the addition of a catalytic amount of pyrrolidine leading ultimately to the formation of 13a in 50% yield. The expected Knoevenagel adduct 15 was not observed which lead us to postulate that the two ketones flanking the alkylidene moiety enhanced its reactivity, thus triggering a spontaneously 1,4-addition of a second dimedone molecule, hence the formation of 13a as the sole product of the reaction [16]. Therefore, we hypothesized that a stable alkylidene surrogate of 15, such as the Mannich-base 16, could solve this issue of chemoselectivity via a stepwise approach. Bolte and others reported that Knoevenagel products could be intercepted by secondary amines to form stable Mannich bases [19], therefore we reasoned that such product 16 could be utilized for the synthesis of unsymmetrical heterocycles. Indeed we found that InCl3 efficiently catalyzed the condensation between 10 and 5a, while the Knoevenagel intermediate 15 was intercepted with pyrrolidine to afford the adduct 16 in 88% isolated yield [20]. As shown by Porco Jr. and others, pyrolidine adducts such as. 16 are stable and potential in situ precursors of Knoevenagel alkylidenes [21]. Directly treating 16 with the pro-nucleophile tetronic acid 6 enabled the clean formation of the unsymmetrical dienol adduct 12a in 85% yield. In this event, we propose that tetronic acid 6 (pKa(H2O) ~3.8) favorably protonates the pyrrolidine nitrogen of 16, triggering the leaving group extrusion while transforming the pro-nucleophile 6 into a more reactive conjugated enolate for the ensuing 1,4-addition. Using this strategy, the unsymmetrical open-dienol product 12a was obtained in 75% yield over 2 steps (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Role of the Knoevenagel condensation adduct 15 toward unsymmetrical homo- and heterodimers 13a/12a.a.

a Reactions carried on equimolar ratios of aldehyde 5a and dimedone 10 with pyrrolidine in toluene (0.1 M) at room temperature (1.0 mmol scale).

The intercepted Knoevenagel condensation–1,4-addition sequence was further optimized to synthesize the pseudo-symmetrical dienol 12a in one-pot (Table 2). Given that InCl3 was initially one of the best catalysts for the MCR (see Table 1, entries 10–11), this catalyst was selected for reaction optimization. The one-pot sequence could be carried out in deuterated solvents to facilitate reaction advancement monitoring by in situ 1H NMR spectroscopy (for the full Table, see Supporting Information Tables SI–1). While the 2-step reaction was low yielding in toluene-d8 (entry 1), reactions in CH3CN, CD3OD and DMSO-d6 were clean, and delivered 12a in less than 6 h. Without catalyst (entries 3 & 6), the reactions still proceeded to completion and delivered 12a in good yields despite longer reaction times. Overall, the reaction appeared to be cleaner and faster in DMSO-d6 and in CH3CN; the latter solvent was selected to further study the reaction scope due to an easier work-up with HCl (0.5 M) affording directly the fused tricyclic 4H-pyran 11a.

Table 2.

Optimization for the synthesis of unsymmetrical dienol 12a via the interrupted Knoevenagel pyrolidine adduct 16.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Solventa | Time | % Conv.b | % Yieldb | |

| Step 1 | Step 2 | ||||

| 1 | Toluene-d8 | 3 h | 12 h | 60 | 55 |

| 2 | CH3CN | 2 h | 30 min | 92 | 68 |

| 3c | CH3CN | 4 h | 1 h | 99 | 75 |

| 4 | CD3CD | 3 h | 2 h | 94 | 65 |

| 5 | DMSO-d6 | 2 h | 20 min | 100 | 90 |

| 6c | DMSO | 5 h | 1 h | 96 | 88 |

Reactions were conducted on 1.0 mmol scale of 10, 5, 6 with pyrrolidine (1.0 eq.) at room temperature, using InCl3 (10 mol%) unless otherwise stated.

Conversions and yields were calculated from crude 1H NMR using mesitylene as internal standard.

Reaction carried out without InCl3.

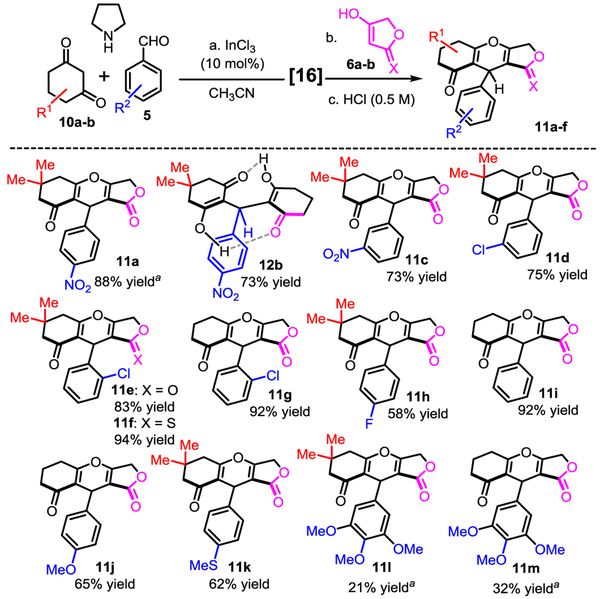

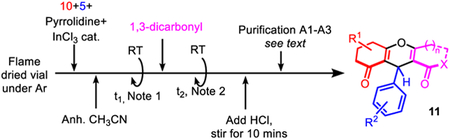

2.3. Synthesis of a library of 4H-pyrans 11

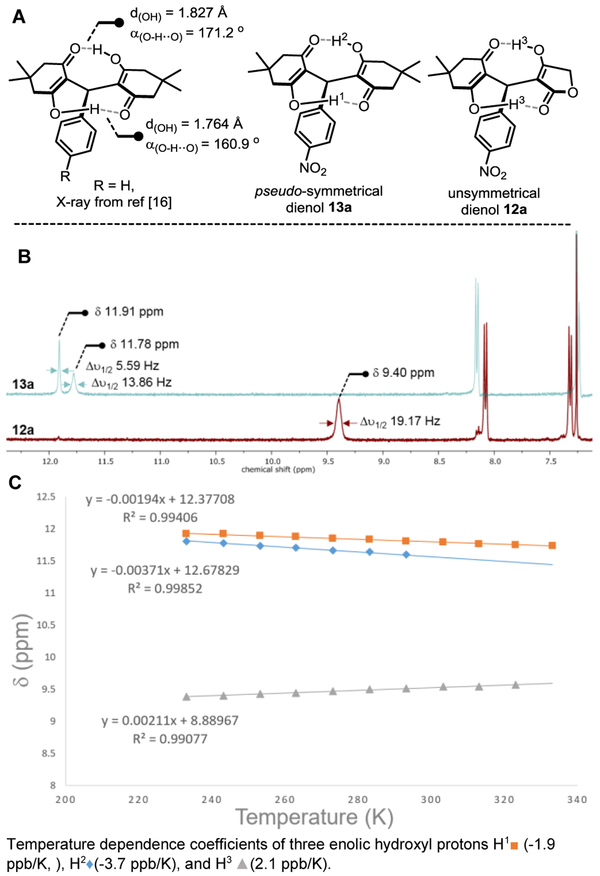

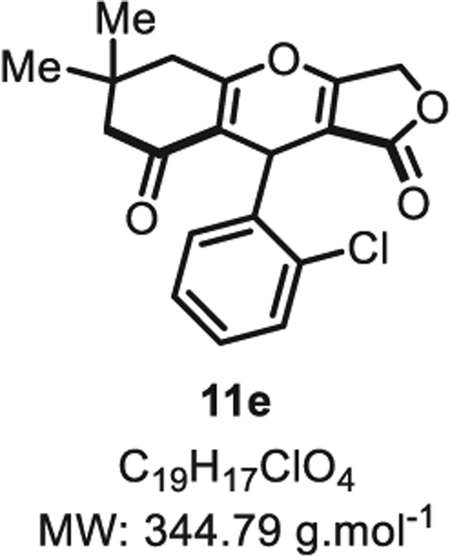

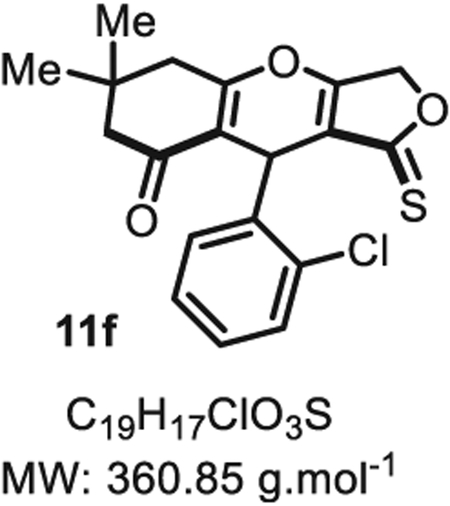

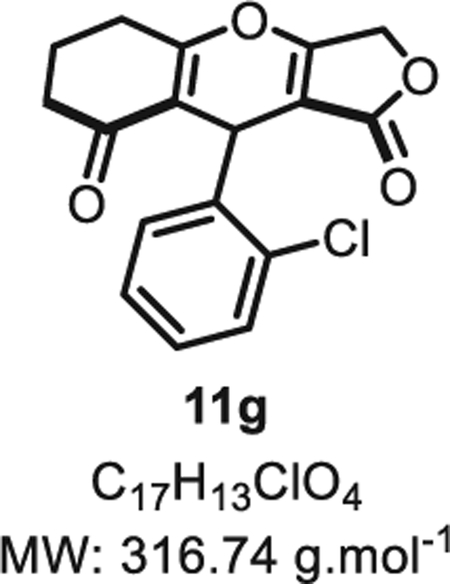

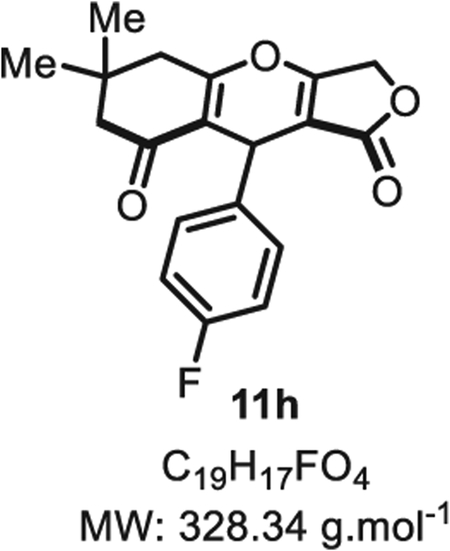

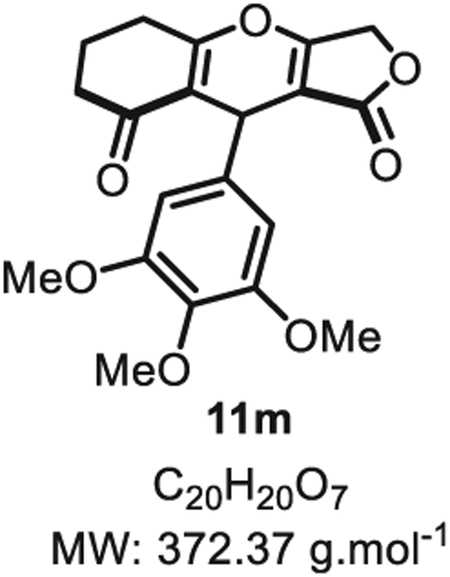

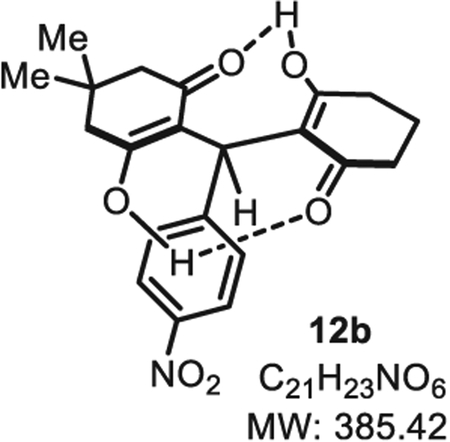

With an optimum set of conditions in hand, the scope of the one-pot reaction catalyzed by InCl3 in acetonitrile was examined (Scheme 3). A simple acidic work-up at the end of the reactions enabled the final cyclization for the preparation of 4H-pyrans 11a and 11c-m in moderate to good yields. The domino reactions proceeded smoothly with variously substituted benzaldehydes bearing electron withdrawing groups leading to various 4H-pyrans (e.g. 11a, 11c-d, 11g) in high yields. Reactions with less reactive benzaldehydes (with electron neutral and electron donating groups) produced the desired products (e.g. 11i-m) despite in lower yields. For the most electron-rich aldehyde the reaction delivered products 11l and 11m in modest yields (21% and 32% yields respectively); Even though we have no current explanations for these results, the reactions can be improved without indium catalysts to obtain 11l and 11m in 51% and 69% yields (Scheme 3). The reaction was found to tolerate not only dimedone, but also cyclohexanedione in ring A, and the thiotetronic acid in ring C, without major differences in yields (11e vs 11f, and 11g). Compound 12b, similarly to homodimer 13a, is the only substrate from the library which did not cyclize spontaneously during either acidic workup, or column chromatography. Accordingly to the report by Sun [16], some dimeric dienols are remarkably stable due to their intramolecular hydrogen-bond network across the two β-diketone enols. The X-ray crystal structure obtained by the Sun’s group revealed that both intramolecular hydrogen-bonds are relatively strong as shown by the bond lengths (~1.80 Å), and the donor-acceptor characteristic bond angles (close to 180°) (Fig. 3A).

Scheme 3.

Reaction scope in the synthesis of fused-tricyclic 4H-Pyrans 11..

a Without InCl3 catalysts, reactions delivered compounds 11a, 11l and 11m in 78%, 51% and 69% yields respectively.

Fig. 3.

Intramolecular hydrogen-bond strength observed by 1H NMR for pseudo- and un-symmetrical dienols 13a and 12a.

2.4. NMR and synthetic studies underlining the strength of the dienol intramolecular hydrogen-bond network

To further characterize this donor-acceptor pair of hydrogen bonds connected by a resonant π–system (resonance-assisted hydrogen bonding: RAHB) [22], a careful 1H NMR spectral analysis was performed (Fig. 3B/3C) [13]. At −30 °C, the NMR spectra of 13a in CDCl3 revealed the presence of two distinct signals corresponding to a strong and a weaker hydrogen bond (OH-1 and OH-2) at δ 11.91 ppm and 11.78 ppm, as shown by the narrow and larger peak widths at half-height characterizing their exchange rates (Δυ1/2 5.59 and 13.86 Hz respectively), which are in agreement with previous reports on similar intramolecular RAHB network of enols (Fig. 3B) [23]. In stark contrast, dienol 12a presented only one broad signal accounting for the 2 enolic protons (OH-3), significantly deshielded (δ 9.40 ppm) with a larger peak width at half-height Δυ1/2 of 19.17 Hz typical of a fast equilibrium between rotational conformers resulting from a weaker hydrogen-bond network. Variable-temperature 1H NMR studies were further performed to determine the chemical shift deviation and the melting temperature for 12a and 13a (Fig. 3C) [24]. As shown in this graph, the temperature dependence coefficients of three enolic hydroxyl protons (Δδ/T: slopes of linear regressions) were obtained at 25 mM concentrations in a range of temperatures from −50 °C to 70 °C for OH-1 (■, −1.9 ppb/K), OH-2 (◆, −3.7 ppb/K) of 12a, and OH-3 (▲, 2.1 ppb/K) of 13a. These results suggest that in the range of temperatures studied, the OH chemical shifts are minimally affected as expected for moderately strong intramolecular hydrogen bonds (Δδ/T < 4 ppb/K) [25]. While examining the temperature dependency on the enolic chemical shifts in CDCl3, it was found that the enolic signal OH-3 for 12a slowly disappeared upon temperature increase [25a]. The melting temperature (Tm) corresponding to the rupture of the hydrogen-bond network between dienol conformers in 12a was found to be 50 ± 5 °C, corresponding to a relatively low transition-state energy barrier ΔGǂ = 15.1 ± 0.3 kcal/mol [26]. On the other hand, the melting temperature of 13a could not be determined in CDCl3 (Tm > 70 ± 5 °C), but the corresponding ΔGǂ of H-bonds cleavage was determined to be significantly larger by ~2 kcal/mol (ΔGǂ = 17.5 ± 0.5 kcal/mol).

These calculations are found to be in general agreement with the reported stabilities of intramolecular RAHB networks which might be rationalized by the fact that both enols forming the π-resonance-assisted network have similar dipole moments due to the locked W-configuration of the conjugated cyclic enols [27]. Taken together, these calculations and spectroscopic data suggest that the pseudo-symmetrical dienol 13a (e.g. 12b, 14a) possess a stronger and tighter intramolecular hydrogen-bond network that restricts free rotation around the benzylic C–C bond, which in turn might hamper the final dehydrative cyclization.

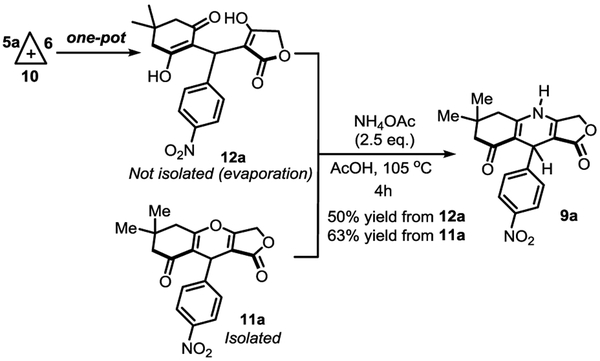

Given that the dienol moieties in 12a can be considered as vinylogous acid and carbonate with weaker intramolecular interactions, we thought to attempt the final annulation reaction promoted by a BrØnsted acid with ammonium acetate as the source of ammonia at a higher temperature (Scheme 4). Compound 12a was obtained using the domino reaction via the Knoevenagel-intercepted adduct 16, further evaporated and engaged directly in the annulation reaction at 105 °C. As suggested above, the high temperature is required to cleave the hydrogen-bond network and enable the final cyclization. From this domino one-pot reaction, the desired 1,4-DHP product 9a was ultimately obtained in 50% yield. To conclude this study, 4H-Py 11a was also subjected to the annulation conditions, and once again product 9a could be prepared this time in 63% yield. In this case, 4H-Py 11a might undergo ring opening before the final cyclization and extrusion of water through an addition-elimination mechanism.

Scheme 4.

Endgame for the synthesis of the unsymmetrical 1,4-dihydropyridine 9a.

3. Conclusion

In summary, we reported a general and straightforward one-pot synthesis of various fused-tricyclic unsymmetrical 4H-pyrans 11. Indium trichloride has emerged from this study to be the most efficient catalyst to promote the domino reaction. The mechanistic and NMR studies revealed two important features to achieve the domino process: a) the critical role of the intercepted-Knoevenagel adduct 16 to achieve high chemoselectivity towards these unsymmetrical heterocycles and b) the importance of the hydrogen-bonds strength in the network of hydrogen-bonded dienol intermediates (e.g. 12a, 13a) which tempered the ease of annulation. According to the 1H VT-NMR experiments, we found that the intramolecular hydrogen-bond network of the most symmetrical dienols are tighter and stronger (ΔGǂ 17.5 ± 0.5 kcal/mol), than the network in unsymmetrical compounds (ΔΔGǂ ~ 2 kcal/mol) which could explain the facile synthesis of unsymmetrical 4H-pyrans 11. For the most symmetrical molecules, the final annulation is hampered by an intramolecular network of hydrogen bonds between enols, which can be ruptured at high temperature as suggested by the transition state energy barrier determined by the VT-NMR experiments. Even though the intercepted-Knoevenagel condensation with secondary amines has been known for a long time [19], the ability of such Mannich base 16 to slowly generate Michael acceptors in situ has been largely ignored. This concept offers far-reaching opportunities for the synthesis of unsymmetrical and complex 1,4-dihydropyrines such as 9a, which are “privileged structures” in medicinal chemistry [28]. Ongoing studies in our laboratory aim at developing the scope of this domino reaction, an alternative strategy to the Hantzsch-4CR, and an asymmetric variant for the synthesis of fused-tricyclic 1,4-dihydropyridines [29].

4. Experimental

4.1. General information

Reactions were performed in flame-dried glassware under a positive pressure of argon. Yields refer to spectroscopically pure compounds. Analytical TLC was performed on 0.25 mm glass backed 60 Å F-254 TLC plates (Silicycle, Inc.). The plates were visualized by exposure to UV light (254 nm) and developed by a solution of vanillin in ethanol/sulfuric acid or cerium-ammonium-molybdate in water/sulfuric acid and heat. Flash chromatography purifications were performed using 200–400 mesh silica gels (Silicycle, Inc.). Infrared spectra were recorded on a Nicolet IS5 FT-IR spectrophotometer. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury400 and a Bruker biospinGmbH (400 MHz) spectrometer and are reported in ppm using solvent as an internal standard (CDCl3 at 7.26 ppm, CD3OD at 3.31 ppm and DMSO-d6 at 2.50 ppm). NMR spectra were performed using standard parameter and data are reported as: (b = broad, s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet; coupling constant(s) in Hz, integration). 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury400 (100 MHz) spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm, with solvent resonance employed as the internal standard (CDCl3 at 77.2 ppm, CD3OD at 49.0 ppm and DMSO-d6 at 39.5 ppm). Melting points were determined using a Digimelt digital melting point apparatus. Electron ionization (EI) source was used and Restek (Rtx®−5) capillary column with 30 m length, 1.25 mm internal diameter and 0.1 μm film thickness. Accurate mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained from the University of Florida using an Agilent 6220 TOF, a Bruker Daltonics, or an Impact II QTOF instrument.

4.1.1. 6,6-Dimethyl-9-(4-nitrophenyl)-5,6,7,9-tetrahydrofuro [3,4-b]quinoline-1,8(3H,4H)-dione 12a

In a flame dried 20 mL scintillation vial, under argon, dimedone 10 (70 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.), p-nitrobenzaldehyde 5a (76 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.), pyrrolidine (50 μL, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) and indium chloride (13 mg, 0.050 mmol, 10 mol%) were dissolved in acetonitrile (2.5 mL, 0.20 M). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h to obtain the intercepted-Knoevenagel product 16 in situ. Tetronic acid 6 (60 mg, 0.60 mmol, 1.2 eq.) was then added directly to the vial and the mixture was left stirred at room temperature for 1.5 h. Acetonitrile was evaporated under vacuum to obtain the crude yellow solid, and an extraction was achieved with CH2Cl2 (3 × 20 mL) and water (5.0 mL). Note: Neutral condition must be used to avoid the spontaneous cyclization of 12a into 11a. The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated under vacuum to obtain the crude dienol 12a as a light-yellow solid (130 mg, 0.35 mmol, 70% crude yield, 2 steps). Rf =0.41 (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1). Mp = 135 ± 5 °C. IR νmax (neat): 3340, 1727, 1514, 1455, 1371, 1326, 1210, 1019, 975, 848, 777, 738, 696 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ (ppm): 8.06 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 5.70 (s, 1H), 4.57 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 2.28 (s, 4H), 1.06 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ (ppm): 191.3, 183.1, 180.2 (2C), 152.7, 147.2, 129.2 (2C), 124.0 (2C), 117.3, 99.3, 69.3, 46.7, 32.6, 32.5, 28.6 (2C), 25.0. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M-H20 + H]+ Calcd for [C19H17NO6 +H]+ 356.1129; Found 356.1126 (0.8 ppm).

SMILES: OC(CC(C)(C)C1) = C(C(C2=CC=C([N+]([O−]) = O)C=C2)C(C(OC3) = O)=C3O)C1=O.

4.1.2. 3,3,6,6-Tetramethyl-9-(4-nitrophenyl)-3,4,6,7,9,10-hexahydroacridine-1,8(2H,5H)-dione 13a

In a flame dried round bottom flask, a mixture of p-nitrobenzaldehyde 5a (76 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.), dimedone 10 (140 mg, 1.0 mmol, 2.0 eq.) and ammonium acetate (39 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) in ethanol (2.5 mL, 0.20 M) were stirred for a day at room temperature. The white precipitate was then filtered and washed with ethyl acetate (10 mL) and dry under high vacuum to obtain 13a in a pure form (176 mg, 0.42 mmol, 85% yield). Rf =0.49 (EtOAc/hexanes 30:70). IR νmax (neat): 3410, 3064, 2960, 1591, 1451, 1374, 1251, 967,820 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ (ppm) 8.02 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.27 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.32 (s, 1H), 2.26 (s, 8H), 1.08 (s, 12H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD): δ (ppm) 191.2 (4C), 154.7, 146.5, 128.9 (2C), 123.7 (4C), 115.9 (2C), 49.38(2), 33.2, 32.4 (2C), 28.8 (4C). HR-MS (ESI): m/z Calcd. for [C23H27NO6+H]+ = 414.1917, Found 414.1948 (+7.5 ppm). Spectral data for compound 13a were consistent with the data previously reported in the literature [30].

SMILES:O=C1C(C(C2=CC=C([N+]([O]) = O)C=C2)([H]) C3=C(O[H])CC(C)(C)CC3=O)=C(O[H])CC(C)(C)C1.

4.1.3. 8-(4-nitrophenyl)-5,8-dihydro-1H,3H-difuro[3,4-b:3′,4′-e] pyridine-1,7(4H)-dione 14a

In a flame dried round bottom flask, a mixture of p-nitrobenzaldehyde 5a (76 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.), tetronic acid 6 (100 mg, 1.0 mmol, 2.0 eq.) and ammonium acetate (39 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) in ethanol (2.5 mL, 0.20 M) were stirred for a day at rt. After solvent evaporation under vacuum, product 14a was recrystallized in hexane, filtered and dried (75 mg, 0.225 mmol, 45% yield). Rf=0.49 (EtOAc/hexanes 30:70; UV Active; stains white in KMnO4). IR νmax (neat): 3340, 1727, 1514, 1455, 1371, 1326, 1210, 1019, 975, 848, 777, 738, 696 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ (ppm) 9.65 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 9.15–9.06 (m, 2H), 6.36 (s, 1H), 6.03 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 5H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD): δ (ppm) 183.9 (2C), 180.5 (2C), 152.9, 147.5, 129.1 (2C), 124.4 (2C), 99.1 (2C), 70.0 (2C), 34.0. HRMS (ESI): m/z Calcd. for [C15H11NO8+H]+ 334.0563, Found 334.0589 (+7.8 ppm). Spectral data for compound 14a were consistent with the data previously reported in the literature [31]. SMILES: [H]N1C2 = C(C(OC2) = O)C(C3=CC=C([N+]([O−]) = O)C=C3)C4=C1COC4 = O.

4.2. General procedure A for the preparation of unsymmetrical 4H-pyrans 11

In a flame dried 20 mL scintillation vial under argon, dimedone or 1,3-cyclohexandione (0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.), a selected benzaldehyde (0.50 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), pyrrolidine (50 mL, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) and indium chloride (0.05 mmol, 10 mol%) were dissolved in acetonitrile (2.5 mL, 0.20 M). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for the indicated amount of time (t1 in h). Note 1: Intercepted intermediate 16 formed a precipitate in the reaction media. A selected 1,3-dicarbonyl molecule (0.60 mmol, 1.2 eq.) was then added directly to the vial and the mixture was stirred at room temperature until reaction completion (t2 in h). Note 2: The intercepted intermediate 16 disappeared over time after the addition of the 1,3-dicarbonyl partner to the reaction media. A HCl solution (10 mL, 0.50 M) was then poured into the reaction mixture, and stirred for 15 min to achieve cyclization. Three distinct methods of isolation have been developed. Procedure A1: If a precipitate formed during stirring with HCl, the product can directly be filtered and washed with cold ethyl acetate (2 × ~2.0 mL). Procedure A2: If no precipitate appeared after stirring with HCl, an extraction was achieved with CH2Cl2 (3 × 20 mL) and the combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and evaporated under vacuum. The crude product was then purified by trituration with minimum amounts of ethyl acetate (2 × ~2.0 mL). Procedure A3: If the crude product after extraction/evaporation is an oil, the oil can be triturated with petroleum ether and the resulting solid can then be filtered and triturated a second time with ethyl acetate (2 × ~2.0 mL) to isolate the desired product 11.

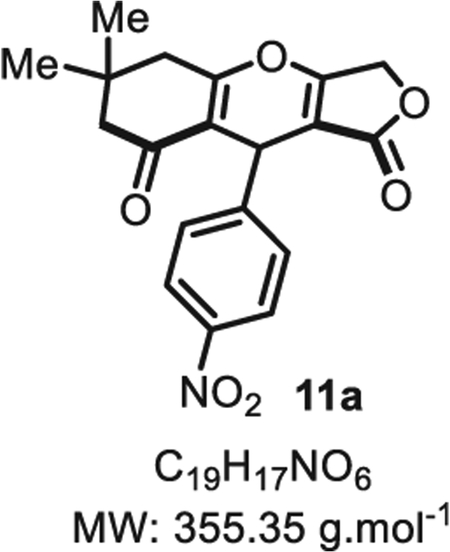

4.2.1. 6,6-Dimethyl-9-(4-nitrophenyl)-5,6,7,9-tetrahydro-1H-furo [3,4-b]chromene-1,8(3H)-dione 11a

Compound 11a was synthesized from p-nitrobenzaldehyde (76 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) at room temperature and purified accordingly to general procedure A2 (t1 = 2 h, t2 = 1.5 h) to obtain 11a in pure form as a white solid (156 mg, 0.43 mmol, 88% yield). Rf = 0.51 (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1). Mp = 135 ± 5 °C. IR νmax (neat): 3340, 1727, 1514, 1455, 1371, 1326, 1210, 1019, 975, 848, 777, 738, 696 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ (ppm): 8.10 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 5.59 (s, 1H), 4.73 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 4.58 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 2.38 (s, 4H), 1.08 (s, 6H). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 8.09 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 5.35 (s, 1H), 4.74 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 4.64 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 2.35 (s, 4H), 1.01 (s, 6H). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.12 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.28 (s, 2H), 5.52 (s, 1H), 4.86 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 4.70 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 2.71 (d, J = 18.0 Hz, 1H), 2.63 (d, J = 18.0 Hz, 1H), 2.33 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 2.26 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.08 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ (ppm): 191.2, 178.1, 177.5 (2C), 150.1, 147.5, 130.4, 128.9 (2C), 124.2 (2C), 116.2, 101.1, 68.3, 47.8, 33.2, 32.9, 28.4 (2C). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 202.6, 178.5, 178.0 (2C), 147.3, 146.6, 127.5 (2C), 123.8 (2C), 115.4, 101.0, 68.0, 50.6, 43.4, 32.3, 31.6, 28.4 (2C). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C19H18NO6 356.1129; Found 356.1128 (0.3 ppm). SMILES: O=C(OC1)C2=C1OC3 = C(C(CC(C)(C)C3) = O)C2C4 = CC=C([N+]([O−]) = O)C=C4.

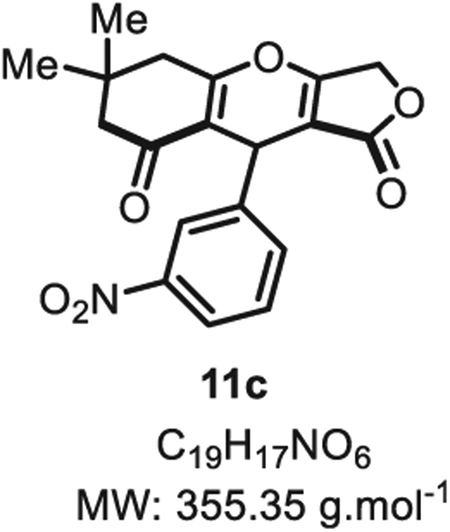

4.2.2. 6,6-Dimethyl-9-(3-nitrophenyl)-5,6,7,9-tetrahydro-1H-furo [3,4-b]chromene-1,8(3H)-dione 11c

Compound 11c was synthesized from m-nitrobenzaldehyde (76 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) at room temperature, and purified accordingly to general procedure A1 (t1 = 2 h, t2 = 2 h) to be obtained in pure form as a white solid (128 mg, 0.36 mmol, 73% yield). Rf = 0.51 (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1). Mp = 138 ± 5 °C. IR νmax (Neat): 3335, 1798, 1505, 1399, 1368, 1308, 1210, 1025, 970, 849, 777, 738, 698 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.10–8.03 (m, 1H), 8.02–7.95 (m, 1H), 7.52–7.40 (m, 2H), 5.53 (s, 1H), 4.88 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 4.70 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 2.73 (d, J = 17.9 Hz, 1H), 2.64 (d, J = 17.9 Hz, 1H), 2.34 (d, J 16.8 Hz, 1H), 2.27 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 1.19 (s, 3H), 1.09 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 202.5, 178.6, 177.9 (2C), 148.7, 141.6, 132.7, 129.5, 121.9, 121.7, 115.3, 101.2, 68.1, 50.7, 43.4, 32.3, 31.4, 28.7, 28.3. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + NH4]+ Calcd for C19H21N2O6 373.1394; Found 373.1385 (2.4 ppm).

SMILES: O=C(OC1)C2=C1OC3 = C(C(CC(C)(C)C3) = O) C2C4 = CC=CC([N+]([O−]) = O)=C4.

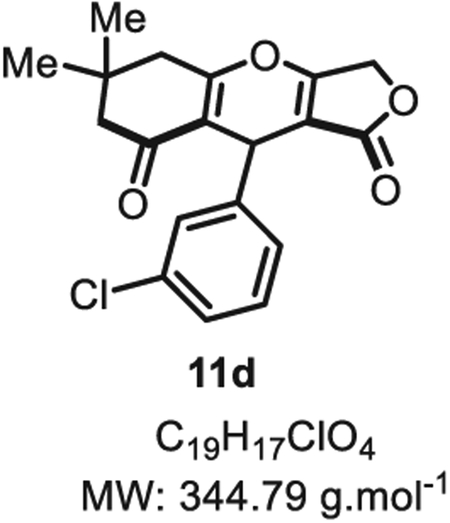

4.2.3. 8-(4-Nitrophenyl)-5,8-dihydro-1H,3H-difuro[3,4-b:3′,4′-e] pyridine-1,7(4H)-dione 11d

Compound 11d was synthesized from m-chlorobenzaldehyde (71 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1 eq.) at room temperature, and purified accordingly to general procedure A3 (t1 = 2 h, t2 = 2 h) to be obtained in pure form as a white solid (129 mg, 0.37 mmol, 75% yield). Rf = 0.53 (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1). Mp = 126 ± 5 °C. IR νmax (Neat): 2958, 1714, 1638, 1593, 1570, 1469, 1380, 1313, 1260, 1178, 1156, 1126, 1074, 1031, 999, 891, 790, 777, 709, 681 cm−1.1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.22–7.14 (m, 2H), 7.08 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.02–6.98 (m, 1H), 5.43–5.39 (m, 1H), 4.83 (d, J =16.5 Hz, 1H), 4.67 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 2.66 (d, J = 17.7 Hz, 1H), 2.58 (d, J = 17.7 Hz, 1H), 2.33 (d, J = 16.7 Hz, 1H), 2.25 (d, J = 16.7 Hz, 1H), 1.16 (s, 3H) 1.08 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 202.5, 178.7, 177.8 (2C), 141.5, 134.5, 129.7, 126.9, 126.6, 124.8, 115.6, 101.3, 67.9, 50.7, 43.5, 32.2, 31.1, 28.4 (2C). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C19H18ClO4 345.0888; Found 345.0873 (4.3 ppm).

SMILES: O=C(OC1)C(C2C3 = CC=CC(Cl)=C3) = C1OC4 = C2C(CC(C)(C)C4) = O.

4.2.4. 9-(2-Chlorophenyl)-6,6-dimethyl-5,6,7,9-tetrahydro-1H-furo [3,4-b]chromene-1,8(3H)-dione 11e

Compound 11e was synthesized from o-chlorobenzaldehyde (70 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) at room temperature and purified accordingly to general procedure A2 (t1 = 2 h, t2 = 2 h) to be obtained in pure form as a white solid (143 mg, 0.41 mmol, 83% yield). Two atropoisomers are observed by 1H NMR at room temperature in an 88:12 ratio [13]. Rf = 0.53 (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1). Mp = 141 ± 5 °C. IRν max (Neat): 3059, 2958, 1721, 1667, 1591, 1469, 1418, 1379, 1316, 1281, 1259, 1202, 1169, 1109, 1037, 1016, 941, 908, 813, 754, 727 cm−1.1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 7.37 (dd, J = 7.6 Hz, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (td, J = 7.5, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (td, J = 7.5, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 5.49 (s, 1H), 4.76 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 4.63 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 2.59 (s, 2H), 2.32 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 2.24 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 1.10 (s, 3H), 1.06 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 195.5, 174.1, 174.0, 172.8, 139.1, 132.5, 130.5, 128.9, 127.3, 126.0, 112.4, 99.4, 66.1, 46.6, 31.5, 31.4 (2C), 27.8 (2C). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M+H]+ Calcd for C19H18ClO4 345.0888; Found 345.0877 (3.2 ppm).

SMILES: O=C(OC1)C(C2C3 = CC=CC=C3Cl)=C1OC4 = C2C(CC(C)(C)C4) = O.

4.2.5. 9-(2-chlorophenyl)-6,6-dimethyl-1-thioxo-1,3,5,6,7,9-hexahydro-8H-furo [3,4-b]chromen-8-one 11f

Synthesis of the tetronic acid thiono-analogue was achieved in three steps accordingly to a literature precedent [32]. Compound 11f was synthesized from o-chlorobenzaldehyde (70 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) at room temperature and purified accordingly to general procedure A2 (t1 = 2 h, t2 = 1.5 h) to be obtained in pure form as a white-yellow solid (170 mg, 0.47 mmol, 94% yield). Rf 0.50 (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1). Mp = 142 ± 5 °C. IRνmax (Neat): 2958, 1619, 1522, 1469, 1409, 1385, 1326, 1325, 1298, 1156, 1124, 1075, 1027, 1014, 962, 886, 777, 749, 705 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.42 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (td, J = 7.6, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (td, J = 7.6, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 5.72 (s, 1H), 5.10 (d, J = 18.5 Hz, 1H), 4.92 (d, J = 18.5 Hz, 1H), 2.53–2.45 (m, 2H), 2.37–2.10 (m, 2H), 1.09 (s, 3H), 1.06 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 216.9, 190.1, 178.8, 135.6, 133.3, 130.3, 129.4, 128.3, 126.6, 117.2, 115.6, 115.2, 74.6, 35.2 (2C), 31.6 (2C), 28.5, 28.2. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H20 + H]+ Calcd for C19H20ClO4S 379.0761; Found 379.0770 (2.4 ppm).

SMILES: S=C(OC1)C(C2C3 = CC=CC=C3Cl)=C1OC4 = C2C(CC(C)(C)C4) = O.

4.2.6. 9-(2-chlorophenyl)-6,6-dimethyl-5,6,7,9-tetrahydro-1H-furo [3,4-b]chromene-1,8(3H)-dione 11g

Compound 11g was synthesized from o-chlorobenzaldehyde (70 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) at room temperature, and purified accordingly to general procedure A2 (t1 = 2 h, t2 = 2 h) to be obtained in pure form as a white solid (145 mg, 0.46 mmol, 92% yield). Two atropoisomers are observed by 1H NMR at room temperature in an 88:12 ratio [13]. Rf = 0.52 (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1). Mp = 138 ± 5 °C. IRνmax (Neat): 3141, 2947, 1714, 1633, 1555, 1442, 1415, 1385, 1305, 1253, 1200, 1158, 1118, 1005, 968, 914, 858, 758, 742 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.29 (dd, J 7.5, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (dd, J = 7.5, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (dtd, J = 13.1, 7.3, 3.5 Hz, 2H), 5.29 (s, 1H), 4.67 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 4.58 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 2.39–2.36 (m, 4H), 1.90–1.76 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 195.7, 174.3 (2C), 172.9, 138.8, 132.6, 130.4, 129.1, 127.4, 126.1, 113.7, 99.6, 66.3, 33.1 (2C), 31.5, 20.3. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C17H14ClO4 317.0575; Found 317.0574 (0.3 ppm).

SMILES: O=C(OC1)C(C2C3 = CC=CC=C3Cl)=C1OC4 = C2C(CC([H])([H])C4) = O.

4.2.7. 9-(4-fluorophenyl)-6,6-dimethyl-5,6,7,9-tetrahydro-1H-furo [3,4-b]chromene-1,8(3H)-dione 11h

Compound 11h was synthesized from p-fluorobenzaldehyde (62 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) at room temperature, and purified accordingly to general procedure A3 (t1 = 2 h, t2 = 2.5 to be obtained in pure form as a white solid (96 mg, 0.29 mmol, 58% yield). Rf = 0.56 (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1). Mp = 136 ± 5 °C. IR νmax (Neat): 2957, 2920, 2851, 1710, 1634, 1505, 1377, 1269, 1157, 1033, 927, 766, 715 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.08 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (t, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 5.45 (s, 1H), 4.80 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 2.65 (d, J = 17.8 Hz, 1H), 2.59 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 2.32 (d, J = 16.6 Hz 1H), 2.25 (d, J = 16.7 Hz, 1H), 1.14 (s, 3H), 1.07 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 202.4, 178.8, 177.4, 177.2, 161.5 (d, J = 244.8 Hz), 134.5, 128.2 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2C), 116.0, 115.4 (d, J = 21.3 Hz, 2C). 102.0, 68.0, 60.6, 50.7, 43.4, 32.1, 30.9, 28.5. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M+H]+ Calcd for C19H18FO4 329.1184; Found 329.1186 (0.6 ppm).

SMILES: O=C(OC1)C2=C1OC3=C(C(CC(C)(C)C3)=O) C2C4 = CC=C(F)C=C4.

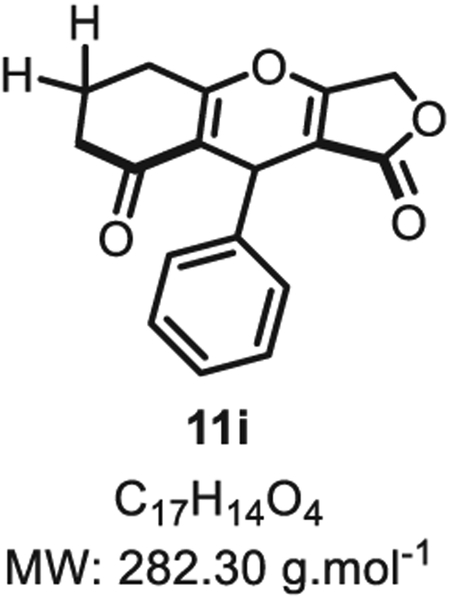

4.2.8. 9-Phenyl-5,6,7,9-tetrahydro-1H-furo [3,4-b]chromene-1,8(3H)-dione 11i

Compound 11i was synthesized from benzaldehyde (53 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) at room temperature, and purified accordingly to general procedure A2 (t1 = 2.5 h, t2 = 2.5 h) to be obtained in pure form as a white solid (130 mg, 0.46 mmol, 92% yield). Rf (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1). Mp = 138 ± 5 °C. IRνmax (Neat): 2940, 1709, 1634, 1558, 1413, 1185, 1045, 1020, 981, 857, 793, 716, 693 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.27 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.22–7.16 (m, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 5.41 (s, 1H), 4.81 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 2.78 (d, J = 17.6 Hz, 1H), 2.69 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 2.45 (d, J = 17.8 Hz, 1H), 2.37 (d, J = 14.1 Hz, 1H), 2.12–1.95 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 202.5, 178.9, 178.7, 176.7, 138.3, 128.6 (2C), 126.5 (2C), 126.4, 117.5, 102.2, 68.1, 36.8, 31.6, 29.9, 20.2. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H20 + H]+ Calcd for C17H17O5 301.1076; Found 301.1226 (50 ppm). SMILES: O=C(OC1) C2=C1OC3 = C(C(CC(C)(C)C3) = O)C2C4 = CC]CC]C4.

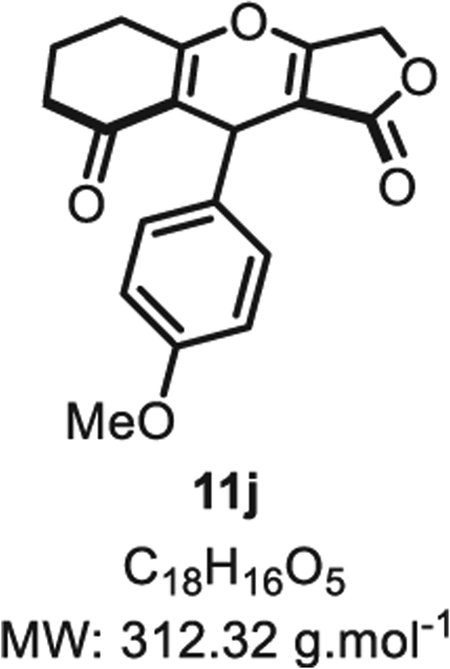

4.2.9. 9-(4-methoxyphenyl)-5,6,7,9-tetrahydro-1H-furo [3,4-b] chromene-1,8(3H)-dione 11j

Compound 11j was synthesized from p-methyloxybenzaldehyde (68 mg, 0.5 mmol, 1.0 eq.) at room temperature, and purified accordingly to general procedure A2 (t1 = 3 h, t2 = 2.5 h) to be obtained in pure form as a white solid (102 mg, 0.33 mmol, 65% yield). Rf = 0.52 (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1). Mp = 142 ± 5 °C. IR νmax (Neat): 2947, 1719, 1642, 1507, 1374, 1244, 1172, 1022, 980, 823, 740 cm−1.1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 6.95 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.78 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 5.29 (s, 1H), 4.76 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 4.61 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 3.69 (s, 3H), 2.50 (m, 4H), 1.88 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 175.8, 175.6, 157.7, 132.7, 127.8 (2C), 116.7 (2C), 113.9 (2C), 101.0 (2C), 66.8, 55.4 (2C), 30.6 (2C), 20.5. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H20 + H]+ Calcd for C18H19O6 331.1221; Found 331.1182 (12 ppm).

SMILES: O=C(OC1)C2=C1OC3=C(C(CC([H])([H])C3)=O) C2C4 = CC=C(OC)C=C4.

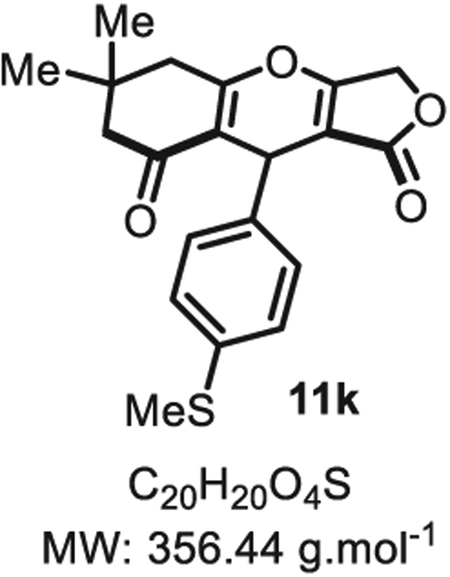

4.2.10. 6,6-Dimethyl-9-(4-(methylthio)phenyl)-5,6,7,9-tetrahydro-1H-furo [3,4-b]chromene-1,8(3H)-dione 11k

Compound 11k was synthesized from p-thio-methylbenzaldehyde (76 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) at room temperature, and purified accordingly to general procedure A2 (t1 = 3 h, t2 = 2.5 h) to be obtained in pure form as a white solid (110 mg, 0.31 mmol, 62% yield) Rf = 0.53 (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1). Mp = 141 ± 5 °C. IR νmax (Neat): 2957, 1713, 1637, 1576, 1380, 1313, 1260, 1047, 969, 860, 727 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm) 7.16 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.09–7.00 (m, 2H), 5.42 (s, 1H), 4.80 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H), 2.61–2.59 (m, 2H), 2.44 (s, 3H), 2.30–2.26 (m, 2H), 1.13 (s, 3H), 1.01 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 202.3, 178.8, 177.2 (2C), 136.2, 136.1, 127.2 (2C), 127.1 (2C), 116.0, 102.0, 68.0, 50.7, 43.4, 32.1 (2C), 31.0, 28.5, 16.2. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M + H20 + H]+ Calcd for C20H23O5S 375.1289; Found 375.1266 (6.1 ppm). SMILES: O=C(OC1)C2=C1OC3=C(C(CC(C)(C)C3) = O)C2C4=CC=C(SC)C=C4.

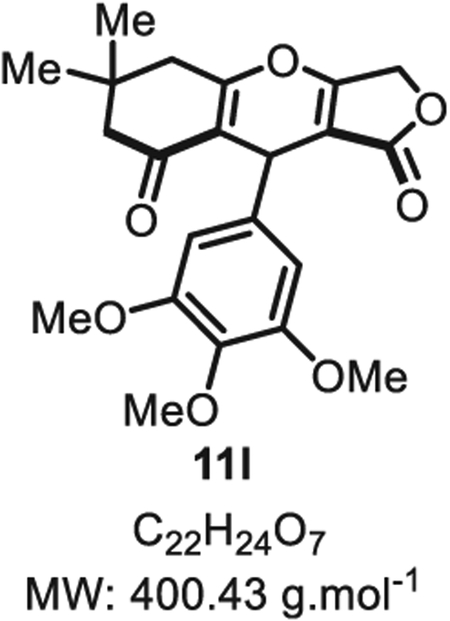

4.2.11. 6,6-Dimethyl-9-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-5,6,7,9-tetrahydro-1H-furo [3,4-b]chromene-1,8(3H)-dione 11l

Compound 11l was synthesized from 3,4,5-methyloxybenzaldehyde (53 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) at room temperature, and purified accordingly to general procedure A1 (t1 = 2 h, t2 = 2.5 h) to be obtained in pure form as a white solid (42 mg, 0.10 mmol, 21% yield). Rf = 0.55 (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1). Mp = 130 ± 5 °C. IR νmax (Neat): 2940, 1709, 1634, 1558, 1413, 1185, 1045, 1020, 981, 857, 793, 716, 693 cm−1.1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 6.34 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 2H), 5.43–5.37 (m, 1H), 4.80 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 3.76 (s, 6H), 2.62 (s, 2H), 2.36–2.24 (m, 2H), 1.17 (s, 3H), 1.10 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 202.1, 178.6, 177.3, 177.0, 153.2 (2C), 136.6, 134.6, 116.1, 104.1 (2C), 101.9, 67.8, 60.9, 56.2 (2C), 50.7, 43.4, 32.0, 31.5, 28.9, 27.9. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M+H]+ Calcd for C22H25O7 401.1595; Found 401.1600 (1.2 ppm).

SMILES:O=C(OC1)C2=C1OC3=C(C(CC(C)(C)C3)=O) C2C4 = CC(OC)=C(OC)C(OC)=C4.

4.2.12. 6,6-Dimethyl-9-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-5,6,7,9-tetrahydro-1H-furo [3,4-b]chromene-1,8(3H)-dione 11m

Compound 11m was synthesized from 3,4,5-methyloxybenzaldehyde (98 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) at room temperature and purified accordingly to general procedure A1 (t1 = 3 h, t2 = 2.5 h) to obtain in pure form as a white solid 11m (60 mg, 0.16 mmol, 32% yield). Rf = 0.55 (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1). Mp 132 ± 5 °C. IR νmax (Neat): 2950, 1717, 1641, 1587, 1505, 1379, 1280, 1183, 1121, 1018, 977, 775, 725 cm−1.1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 6.34 (t, J = 1.2 Hz, 2H), 5.36 (s, 1H), 4.80 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (dd, J = 16.4, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 3.77 (s, 6H), 2.71 (s, 2H), 2.41 (s, 2H), 2.11–1.92 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 202.5, 178.7 (2C), 177.0, 153.2 (2C), 136.8, 134.4, 117.5, 104.1 (2C), 102.0, 67.9, 60.9, 56.2 (2C), 36.9, 31.7, 29.8, 20.3. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M+H]+ Calcd for C20H21O7 373.1282; Found 373.1287 (1.3 ppm).

SMILES: O=C(OC1)C2=C1OC3 = C(C(CC([H])([H])C3) = O) C2C4 = CC(OC)=C(OC)C(OC)=C4.

4.2.13. 3-Hydroxy-2-((2-hydroxy-6-oxocyclohex-1-en-1-yl)(4-nitrophenyl)methyl)-5,5-dimethylcyclohex-2-en-1-one 12b

Compound 12b was synthesized from p-nitrobenzaldehyde (76 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) at room temperature, and purified accordingly to general procedure A (t1 = 2 h, t2 = 2.5 h). After drying the crude solid, a column chromatography using (Ethyl acetate/methanol 9:1) was necessary to obtain 12b in pure form as a white-yellow solid (141 mg, 0.365 mmol, 73% yield).; Rf 0.53 (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1). Mp = 137 ± 5 °C. IR νmax (Neat): 2956, 1723, 1583, 1513, 1491, 1343, 1291, 1032, 851, 731 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 12.03 (s, 1H), 11.84 (s, 1H), 8.12 (d, J 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.27–7.23 (m, 2H), 5.50 (s, 1H), 2.72–2.34 (m, 8H), 2.061/4(dd, J = 10.2, 4.8 Hz, 2H), 1.24 (s, 3H), 1.12 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 192.3, 191.9, 191.5, 188.9, 146.6, 146.3, 127.68 (2C), 123.6 (2C), 116.2, 114.8, 46.9, 46.8, 33.7, 33.5, 32.8, 31.4, 29.9, 27.4, 20.2. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M+H]+ Calcd for C21H24NO6 386.1598; Found 386.1607 (2.3 ppm); [M+Na]+ Calcd for C21H23NO6Na 408.1418; Found 408.1423 (1.2 ppm).

SMILES: OC(CC(C)(C)C1) = C(C(C2=CC=C([N+]([O−]) = O)C=C2)([H])C3=C(O)CCCC3=O)C1=O.

4.2.14. 6,6-Dimethyl-9-(4-nitrophenyl)-5,6,7,9-tetrahydrofuro [3,4-b]quinoline-1,8(3H,4H)-dione 9a

In a flame dried 10 mL scintillation vial, under argon, dimedone 10 (17 mg, 0.12 mmol, 1.0 eq.), p-nitrobenzaldehyde 5a (18 mg, 0.12 mmol, 1.0 eq.), pyrrolidine (20 μL, 0.12 mmol, 1.0 eq.) and indium chloride (2.0 mg, 0.01 mmol, 10 mol%) were dissolved in acetonitrile (0.60 mL, 0.20 M). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. Tetronic acid 6 (24 mg, 0.24 mmol, 1.2 eq.) was then added directly to the vial, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1.5 h. After full reaction conversion, as confirmed by TLC, acetonitrile was evaporated to obtain the crude product 12a which was dissolved in the same flask with acetic acid (0.60 mL, 0.20 M). Ammonium acetate (23 mg, 0.30 mmol, 2.5 eq.) was then added, and the solution and stirred under reflux for 4 h at 105 °C. The reaction was then quenched with ice cold water (1.0 mL). The resulting precipitate was filtered through a filter paper, and the solid was triturate with ethanol (2 × 0.50 mL) to obtain 9a in pure form as a yellow solid (20 mg, 0.06 mmol, 50% overall yield).

Compound 9a was also synthesized from compound 11a, using the following procedure. In a flame dried 10 mL scintillation vial under argon, 11a (64 mg, 0.18 mmol, 1.0 eq.) and ammonium acetate (23 mg, 0.30 mmol, 2.5 eq.) were dissolved in acetic acid (0.60 mL, 0.20 M) and the reaction mixture was stirred for 4 h at 105 °C. The reaction was then quenched with ice cold water (1.0 mL). The resulted precipitate was filtered through a filter paper and the solid was triturate with ethanol (2 × 0.50 mL) to obtain 9a in pure form (40 mg, 0.11 mmol, 63% yield). Rf 0.78 (EtOAc/MeOH 9:1). Mp = 165 ± 5 °C. IRνmax (neat): 2960, 1729, 1678, 1504, 1346, 1193, 1047, 999, 762 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.20 (s, 1H), 8.12 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 4.95 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 4.88 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 4.78 (s, 1H), 2.47 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 2H), 2.21 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 2.07 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 1.03 (s, 3H), 0.96 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm):195.1, 171.7, 157.3, 153.2, 151.6, 146.4, 129.5 (2C), 123.7 (2C), 110.3, 101.9, 65.9, 50.7, 35.1, 32.6 (2C), 28.9, 27.4. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M+H]+ Calcd for C19H19N2O5 355.1288; Found 355.1303 (4.2 ppm); [M + NH4]+ Calcd for C19H22N3O5 372.1554; Found 372.1549 (1.3 ppm). SMILES: O=C(OC1)C(C2C3 = CC=C([N+]([O−]) = O)C=C3) = C1NC4 = C2C(CC(C)(C)C4) = O.

4.2.15. 3-Hydroxy-5,5-dimethyl-2-((4-nitrophenyl)(pyrrolidin-1-yl)methyl)cyclohex-2-en-1-one 16

Dimedone 10 (70 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.), p-nitrobenzaldehyde 5a (76 mg, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.), and indium chloride (13 mg, 0.050 mmol, 10 mol%) were dissolved sequentially in anhydrous toluene (2.0 mL). Pyrrolidine (50 μL, 0.50 mmol, 1.0 eq.) was then added and the reaction mixture was left to stir at room temperature for 3 h. The reaction was then quenched with water (10 mL) and extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 5.0 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and dichloromethane was evaporated to obtain the crude material as a yellow powder. The yellow powder was then washed with diethyl ether to eliminate residual traces of aldehyde and obtain 16 in a pure form (151 mg, 0.44 mmol, 88% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.15 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 5.07 (s, 1H), 3.54–3.37 (m, 1H), 2.89 (d, J = 44.8 Hz, 2H), 2.39 (s, 1H), 2.20 (s, 4H), 2.00 (s, 5H), 0.97 (s, 6H). Spectral data for compound 16 are consistent with the data previously reported in the literature [33].

SMILES: O=C1CC(C)(C)CC(O)=C1C(C2=CC=C([N+]([O−]) = O) C = C2)([H])N3CCCC3.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful for the financial support from the NIH (NIGMS Grant: R15GM116025 to C.S. and S.S.S.). We would like also to acknowledge the Florida Atlantic University Office of Under-graduate Research and Inquiry for funding C.S. through several Undergraduate Research Grants. The authors thank Ms. Margaret Whims for obtaining some preliminary data on this project. The authors also thank Dr. Kari B. Basso at the Mass Spectrometry Research and Education Center from the Department of Chemistry at the University of Florida for the high-resolution mass spectrometry analysis supported by the NIH (S10 OD021758–01A1).

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2019.130606.

References

- [1].(a) Rusch VW, Giroux DJ, Kraut MJ, Crowley J, Hazuka M, Winton T, Johnson DH, Shulman L, Shepherd F, Deschamps C, Livingston RB, Gandara D, J. Clin. Oncol 25 (2007) 313–318; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) For a review on etoposide, see:Hande KR Eur. J. Cancer 34 (1998) 1514–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].(a) Jeedimalla N, Johns J, Roche SP, Tetrahedron Lett 54 (2013) 5845–5848; [Google Scholar]; (b) Jeedimalla N, Flint M, Smith L, Haces A, Minond D, Roche SP, Eur. J. Med. Chem 106 (2015) 167–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].(a) Kamal A, Suresh P, Mallareddy A, Kumar BA, Reddy PV, Raju P, Tamboli JR, Shaik TB, Jain N, Kalivendi SV, Med. Chem 19 (2011) 2349–2358; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shi F, N Zeng X, Zhang G, Ma N, Jiang B, Tu S, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 21 (2011) 7119–7123; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Magedov IV, Frolova L, Manpadi M, Bhoga UD, Tang H, Evdokimov NM, George O, Hadje GK, Renner S, Getlic M, Kinnibrugh TL, Fernandes MA, Van SS, Steelant WFA, Shuster CB, Rogelj S, Van OWAL, Kornienko A, J. Med. Chem 54 (2011) 4234–4246; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) N Semenova M, Kiselyov AS, Tsyganov DV, Konyushkin LD, Firgang SI, Semenov RV, Malyshev OR, Raihstat MM, Fuchs F, Stielow A, Lantow M, Philchenkov AA, Zavelevich MP, Zefirov NS, Kuznetsov SA, Semenov VV, J. Med. Chem 54 (2011) 7138–7149; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Chernysheva NB, Tsyganov DV, Philchenkov AA, P Zavelevich M, Kiselyov AS, Semenov RV, N Semenova M, Semenov VV, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 22 (2012) 2590–2593; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Kamal A, Tamboli JR, Nayak VL, Adil SF, Vishnuvardhan MVPS, Ramakrishna S, Bioorg. Med. Chem 22 (2014) 2714–2723; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) For a review on the synthesis and biological evaluation of 4-aza-podophyllotoxins, see:Botes MG, Pelly SC, Blackie MAL, Kornienko A, van Otterlo WAL Chem. Heterocycl. Compd 50 (2014) 119–138. [Google Scholar]

- [4].(a) Marciniak G, Delgado A, Leclerc G, Velly J, Decker N, Schwartz J, J. Med. Chem 32 (1989) 1402–1407; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vo D, Matowe WC, Ramesh M, Iqbal N, Wolowyk MW, Howlett SE, Knaus EE, J. Med. Chem 38 (1995) 2851–2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].(a) Loev B, Goodman MM, Snader KM, Tedeschi R, Macko E, J. Med. Chem 17 (1974) 956–965; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Atwal KS, Swanson BN, Unger SE, Floyd DM, Moreland S, Hedberg A, O’Reilly BC, J. Med. Chem 34 (1991) 806–811; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kappe CO, Eur. J. Med. Chem 35 (2000) 1043–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].For selected reviews on MCR, see:; (a) Dömling A, Ugi I, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 39 (2000) 3168–3210; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhu J, Eur. J. Org. Chem (2003) 1133–1144; [Google Scholar]; (c) Ramon DJ, Yus M, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 44 (2005) 1602–1634; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Enders D, Grondal C, Huttl MRM, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 46 (2007) 1570–1581; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Touré BB, Hall DG, Chem. Rev 109 (2009) 4439–4486; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Ganem B, Acc. Chem. Res 42 (2009) 463–472; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Dömling A, Wang W, Wang K, Chem. Rev 112 (2012) 3083–3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tratrat C, Giorgi-Renault S, P Husson H, Org. Lett 4 (2002) 3187–3189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].For selected leading references, see:; (a) Ohberg L, Westman J, Synlett (2001) 1296–1298; [Google Scholar]; (b) Zolfigol MA, Safaiee M, Synlett (2004) 827–828; [Google Scholar]; (c) Sharma GVM, Reddy KL, Lakshmi PS, Palakodety KR, Synthesis (2006) 55–58; [Google Scholar]; (d) Debache A, Ghalem W, Boulcina R, Belfaitah A, Rhouati S, Carboni B, Tetrahedron Lett 50 (2009) 5248–5250; [Google Scholar]; (e) Tamaddon F, Razmi Z, Jafari AA, Tetrahedron Lett 51 (2010) 1187–1189. [Google Scholar]

- [9].(a) Ko S, Sastry MNV, Lin C, Yao CF, Tetrahedron Lett 46 (2005) 5771–5774; [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang LM, Sheng J, Zhang L, Han JW, Fan FY, Tian H, Qian CT, Tetrahedron 61 (2005) 1539–1543; [Google Scholar]; (c) Ko S, Yao CF, Tetrahedron 62 (2006) 7293–7299; [Google Scholar]; (d) Legeay JC, Goujon JY, Vanden Eynde JJ, Toupet L, Bazureau JP, J. Comb. Chem 8 (2006) 829–833; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kumar A, Maurya RA, Tetrahedron 63 (2007) 1946–1952; [Google Scholar]; (f) Kumar S, Sharma P, Kapoor KK, Hundal MS, Tetrahedron 64 (2008) 536–542; [Google Scholar]; (g) Cherkupally SR, Mekala R, Chem. Pharm. Bull 56 (2008) 1002–1004; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Sapkal SB, Shelke NF, B Shingate B, Shingare MS, Tetrahedron Lett 50 (2009) 1754–1756; [Google Scholar]; (i) Pasunooti KK, Nixon Jensen C, Chai H, Leow ML, Zhang DW, Liu XW, J. Comb. Chem 12 (2010) 577–581; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Evans CG, Jinwal UK, Makley LN, Dickey CA, Gestwicki JE, Chem. Commun 47 (2011) 529–531; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Rajesh UC, Manohar S, Rawat DS, Adv. Synth. Catal 355 (2013) 3170–3178; [Google Scholar]; (l) Liu YP, Liu JM, Wang X, Cheng TM, Li RT, Tetrahedron 69 (2013) 5242–5247; [Google Scholar]; (m) Ghosh PP, Paul S, Das AR, Tetrahedron Lett 54 (2013) 138–142. [Google Scholar]

- [10].(a) Berson JA, Brown E, J. Am. Chem. Soc 77 (1955) 444–447; [Google Scholar]; (b) Correa WH, Scott JL, Green Chem 3 (2001) 296–301; [Google Scholar]; (c) Dondoni A, Massi A, Minghini E, Bertolasi V, Tetrahedron 60 (2004) 2311–2326. [Google Scholar]

- [11].For recent reviews on the Hantzsch reaction, see:; (a) Simon C, Constantieux T, Rodriguez J, Eur. J. Org. Chem (2004) 4957–4980; [Google Scholar]; (b) Wan JP, Liu Y, RSC Adv 2 (2012) 9763–9777; [Google Scholar]; (c) Comins DL, Higuchi K, Young DW, Adv. Heterocycl. Chem 110 (2013) 175–235. [Google Scholar]

- [12].For the synthesis of fused-tricyclic 1,4-DHPs either via a Hantzsch-3CR or in several steps, see:; (a) Drizin WA, Gopalakrishnan M, Henry RF, Kort ME, Kym PR, Milicic I, Smith JC, Tang R, Turner SC, Whiteaker KL, Zhang H, Sullivan JP, J. Med. Chem 47 (2004) 3180–3192; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Altenbach RJ, Brune ME, Buckner SA, Coghlan MJ, Daza AV, Fabiyi A, Gopalakrishnan M, Henry RF, Khilevich A, Kort ME, Milicic I, Scott VE, Smith JC, Whiteaker KL, Carroll WA, J. Med. Chem 49 (2006) 6869–6887; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tu S, Zhang Y, Jia R, Jiang B, Zhang J, Ji S, Tetrahedron Lett 47 (2006) 6521–6525; [Google Scholar]; (d) Ahmed N, Babu BV, Singh S, Mitrasinovic PM, Heterocycles 85 (2012) 1629–1653; [Google Scholar]; (e) Paul S, Das AR, Tetrahedron Lett 53 (2012) 2206–2210; [Google Scholar]; (f) Shi CL, Chen H, Shi D, J. Heterocycl. Chem 49 (2012) 125–129; [Google Scholar]; (g) Jiang YH, Xiao M, Yan CG, RSC Adv 6 (2016) 35609–35616. [Google Scholar]

- [13].See Supporting Information for full experimental details.

- [14].Dienols 13a and 14a Are Pseudo-symmetrical Due to the Presence of the Benzylic Stereogenic Center that Creates a Different Chemical Environment for Each Hydrogen-Bonded Enols. For a Detailed Analysis, see reference [23].

- [15].Both Pseudo-symmetrical Dienols 13a and 14a Have Been Synthesized Individually Using a Simpler 3-component Reaction to Confirm Their Chemical Structures; see Experimental Section.

- [16].(a) Chung TW, Narhe BD, Lin CC, Sun CM, Org. Lett 17 (2015) 5368–5371; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen LH, Chung TW, Narhe BD, Sun CM, Comb. Sci 18 (2016) 162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kumar R, Andhare NH, Shard A, Richa A.K. Sinha, RSC Adv 4 (2014) 19111–19121. [Google Scholar]

- [18].By Simply Switching the Tetronic Acid Partner 6 (Cyclic Ketoester) with the Acyclic Ethyl Acetoacetate, the Reaction Conditions from Table 1 (Entries 3, 5 or 11) Delivered the Corresponding Unsymmetrical 1,4-DHP Smoothly in above 80% Yields in Each Case. These Results Highlight the Difficulties in Condensing Two Cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl Partners for the Hantzsche4CR.

- [19].(a) Bolte ML, Crow WD, Yoshida S, Aust. J. Chem 35 (1982) 1421–1429; [Google Scholar]; (b) Sielemann D, Keuper R, Risch N, Eur. J. Org. Chem (2000) 543–548; [Google Scholar]; (c) Kennedy JWJ, Vietrich S, Weinmann H, Brittain DEA, J. Org. Chem 73 (2008) 5151–5154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].We propose that the Mannich-base 16 is obtained by an intercepted-Knoevenagel mechanism, because while the Mannich condensation between 5a, 10 and pyrrolidine proceeds to completion in 9 hours large amounts of by-product 13a were isolated. On the other end, the stepwise Knoevenagel condensation between 5a and 10 followed by pyrrolidine addition (intercept) delivered 16 in ~2 hours as the sole reaction product. See also:; Rao P, Konda S, Iqbal J, Oruganti S Tetrahedron Lett (2012) 5314–5317. [Google Scholar]

- [21].(a) Givelet C, Bernat V, Danel M, André-Barrés C, Vial H, Eur. J. Org. Chem (2007) 3095–3101; [Google Scholar]; (b) Gervais A, Lazarski KE, Porco JA, J. B, Org. Chem 80 (2015) 9584–9591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Steiner T, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 41 (2002) 48–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].(a) Frosen S, Frankle WE, Laszlo P, Lubochinsky J, J. Magn. Reson 1 (1969) 327–338; [Google Scholar]; (b) De S. Ferreira M, Figueroa-Villar JD, J. Braz. Chem. Soc 25 (2014) 935–946. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kessler H, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 21 (1989) 512–523. [Google Scholar]

- [25].(a) Exarchou V, Troganis A, Gerothanassis IP, Tsimidou M, Boskou D, Tetrahedron 58 (2002) 7423–7429; [Google Scholar]; (b) Oh J, Quan KT, Lee JS, Park I, Kim CS, Ferreira D, Thuong PT, Kim YH, Na M, J. Nat. Prod 81 (2018) 2429–2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].(a) Gasparro FP, Kolodny NH, J Chem. Educ 54 (1977) 258–261; [Google Scholar]; (b) Haushalter KA, Lau J, Roberts JD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 118 (1996) 8891–8896; [Google Scholar]; (c) Zimmer KD, Shoemaker R, Ruminski RR, Inorg. Chim. Acta 359 (2006) 1478–1484. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Corral-Bautista F, Mayr H, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2015 (2015) 7594–7601. [Google Scholar]

- [28].(a) Krämer A, Mentrup T, Kleizen B, Rivera-Milla E, Reichenbach D, Enzensperger C, Nohl R, Täuscher E, Görls H, Ploubidou A, Englert C, Werz O, Arndt HD, Kaether C, Nat. Chem. Biol 9 (2013) 731–738; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tang L, Gamal El-Din TM, Swanson TM, Pryde DC, Scheuer T, Zheng N, Catterall WA, Nature 537 (2016) 117–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].(a) Rose U, Draeger M, J. Med. Chem 35 (1992) 2238–2243; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gordeev MF, Patel DV, Gordon EM, J. Org. Chem 61 (1996) 924–928; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sridhar R, Perumal PT, Tetrahedron 61 (2005) 2465–2470; [Google Scholar]; (d) Evans C, Gestwicki JE, Org. Lett 11 (2009) 2957–2959; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]; (f) Han ZS, Xu Y, Fandrick DR, Rodriguez S, Li Z, Qu B, Gonnella NC, Sanyal S, Reeves JT, Ma S, Grinberg N, Haddad N, Krishnamurthy D, Song JJ, Yee NK, Pfrengle W, Ostermeier M, Schnaubelt J, Leuter Z, Steigmiller S, Däubler J, Stehle E, Neurmann L, Trieselmann T, Tielmann P, Buba A, Hamm R, Koch G, Renner S, Dehli JR, Schmelcher F, Stange C, Soyka R, Senanayake CH, Org. Lett 16 (2014) 4142–4145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].(a) IIangovan A, Muralidharan S, Sakthivel P, Malayppasamy S, Karuppusamy S, Kaushik M, Tetrahedron Lett 54 (2013) 491–494; [Google Scholar]; (b) Cheng TW, Narhe BD, Lin CC, M Sun C, Org. Lett 17 (2015) 5368–5371; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shirini F, Daneshvar N, RSC Adv 6 (2016) 110190–110205. [Google Scholar]

- [31].(a) Zhang ZZ, Zhang NT, Hu LM, Wei ZQ, Zeng CC, Zhong RG, She YB, RSC Adv 1 (2011) 1383–1388; [Google Scholar]; (b) Pandit KS, Desai UV, Wadgaonkar PP, Kodam KM, Res. Chem. Intermed 43 (2017) 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Labruére R, Désbene-Finck S, Helissey P, Giorgi-Renault S, Synthesis (2006) 4163–4166. [Google Scholar]

- [33].(a) Rao P, Konda S, Iqbal J, Oruganti S, Tetrahedron Lett 53 (2012) 5314–5317; [Google Scholar]; (b) Sabzi NE, Kiasat AR, Catal. Lett 148 (2018) 2654–2664. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.