Abstract

Diagnosis is a cornerstone of clinical practice for mental health care providers, yet traditional diagnostic systems have well-known shortcomings, including inadequate reliability in daily practice, high co-morbidity, and marked within-diagnosis heterogeneity. The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) is a data-driven, hierarchically based alternative to traditional classifications that conceptualizes psychopathology as a set of dimensions organized into increasingly broad, transdiagnostic spectra. Prior work has shown that using a dimension-based approach improves reliability and validity, but translating a model like HiTOP into a workable system that is useful for health care providers remains a major challenge. To this end, the present work outlines the HiTOP model and describes the core principles to guide its integration into clinical practice. We review potential advantages and limitations for clinical utility, including case conceptualization and treatment planning. We illustrate what a HiTOP approach might look like in practice relative to traditional nosology. Finally, we discuss common barriers to using HiTOP in real-world healthcare settings and how they can be addressed.

Keywords: Classification, Diagnosis, Nosology, Psychopathology, Diagnosis, Treatment

A reliable, valid, and clinically useful classification system for mental illness is a cornerstone of clinical practice in the ideal (Kendell & Jablensky, 2003; Krueger et al., 2018; Mullins-Sweatt & Widiger, 2009). It facilitates communication, orients and guides treatment planning, and serves as a common basis for administering care. It also can provide information about the natural course of illness against which to measure the effectiveness of treatment and create a foundation for research (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2006; APA, 2013; First et al., 2014). The present work briefly reviews limitations of the prevailing nosology in place for most clinicians. It introduces a new model of nosology spearheaded by quantitative nosologists (Kotov et al., 2017). Prior work has articulated the empirical basis for these newer models and made clear evidence to support its major contours. However, no work has articulated how such models can be integrated into practice or made a compelling case for its utility (Tyrer, 2018). The goal of the present review is to articulate major principles for integration of an alternative nosology into practice, illustrate its use, and discuss major advantages and challenges of this approach.

In contemporary mental health care systems, diagnosis has overwhelmingly meant using some version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM; APA, 2013) or the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD; World Health Organization [WHO], 2016). However, these nosologies fall short of ideal (Clark, Watson, & Reynolds, 1995; Krueger et al., 2018). Excessive co-occurrence of disorders (i.e., comorbidity) raises questions about their distinctiveness (Clark, Cuthbert, Lewis-Fernández, Narrow, & Reed, 2017). Marked within-diagnosis heterogeneity means that individuals with the same diagnosis can have distinct, even non-overlapping sets of symptoms (Galatzer-Levy & Bryant, 2013), so the pathophysiology, clinical course, and treatment of choice for patients with the same diagnostic label may differ dramatically (Hasler, Drevets, Manji, & Charney, 2004; Olbert, Gala, & Tupler, 2014; Shackman & Fox, 2018; Zimmerman, Ellison, Young, Chelminski, & Dalrymple, 2015). Reliability for several diagnostic categories is low (e.g., ~40% of diagnoses examined in the DSM-5 field trials showed poor inter-rater agreement; Chmielewski, Clark, Bagby, & Watson, 2015; Regier et al., 2013), although not out-of-line with estimates for diagnoses from other areas of medicine (Kraemer, Kupfer, Clarke, Narrow, & Regier, 2012). Finally, traditional systems define mental disorders in terms of demarcated categories of mental illness, yet it has been recognized that most psychopathology falls along a continuum with normality, without the sharp break implied by categories (e.g., Carragher et al., 2014; Clark et al., 2017; Haslam, Holland, & Kuppens, 2012; Kent & Rosanoff, 1910; Markon, Chmielewski, & Miller, 2011; Walton, Ormel, & Krueger, 2011; Wright et al., 2013).

Critically, there are concerns regarding the clinical utility of the DSM and ICD. Practicing clinicians frequently do not assess diagnostic criteria methodically, often lacking the time or incentives to do so (Beutler & Malik, 2002; Blashfield & Herkov, 1996; Bostic & Rho, 2006; Bruchmüller, Margraf, & Schneider, 2012; Hermes, Sernyak, & Rosenheck, 2013; Mohamed & Rosenheck, 2008; Morey & Benson, 2016; Morey & Ochoa, 1989; Taylor, 2016; Waszczuk et al., 2017; Zimmerman & Galione, 2010), although this concern may not be unique to DSM and ICD but a problem for any nosology. For many disorders, the most frequently used diagnosis is Other Specified/Unspecified (Not Otherwise Specified in previous editions of the DSM; Machado, Machado, Gonçalves, & Hoek, 2007; Verheul & Widiger, 2004), meaning the patient’s presentation does not fit any specific category. Moreover, the DSM and ICD categories provide little diagnosis-specific information to guide treatment decisions (First et al., 2018). Most categories have a wide range of applicable treatments, with many pharmaceutical and psychosocial treatments showing transdiagnostic effects (Barlow, Sauer-Zavala, Carl, Bullis, & Ellard, 2013; Weitz, Kleiboer, van Straten, & Cuijpers, 2018). Indeed, a driving force for assigning a patient a DSM or ICD diagnosis may often be less about clinical care and more about administrative or reimbursement requirements (Braun & Cox, 2005; Eriksen & Kress, 2004; First et al., 2018; Mead, Hohenshil, & Singh, 1997; Welfel, 2010; Zimmerman, Jampala, Sierles, & Taylor, 1993).

Quantitative nosology as an empirically based alternative

Quantitative nosology offers a data-driven alternative to classification of mental illness that can address some limitations of prevailing systems and better align with clinical practice. It identifies empirical constellations of co-occurring signs, symptoms, and maladaptive traits and behaviors, and classifies psychopathology accordingly (Kotov et al., 2017; Krueger et al., 2018). Unlike traditional systems that rely heavily on expert consensus (cf. Kendler & Solomon, 2016), quantitative nosology seeks a research-based solution to classification. Statistical analyses guide the grouping of symptoms into coherent dimensional symptom components and traits, which in turn are grouped into broader dimensions in a hierarchical fashion. Higher levels dimensions span diagnostic categories, solving the problem of comorbidity. Meanwhile, specification of lower level dimensions preserves the heterogeneity of symptoms.

Quantitative approaches to classification have a long history (Blashfield, 1984; Eysenck, 1944; Foulds, 1976; Lorr, Klett, & McNair, 1963; Moore, 1930; Overall & Gorham, 1962; Wittenborn, 1951), especially in childhood psychopathology. Two spectra of mental illness, internalizing and externalizing, are particularly well-established (Achenbach, Ivanova, & Rescorla, 2017), and a third spectrum – thought disorder – has also been identified (Keyes et al., 2013; Kotov et al., 2011a; Kotov et al., 2011b; Markon, 2010). Recent studies involving more varied types and severity of psychopathology have recognized other spectra, including antagonistic externalizing, disinhibited externalizing, detachment, and somatoform conditions (Kotov et al., 2011b; Markon, 2010).

The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP)

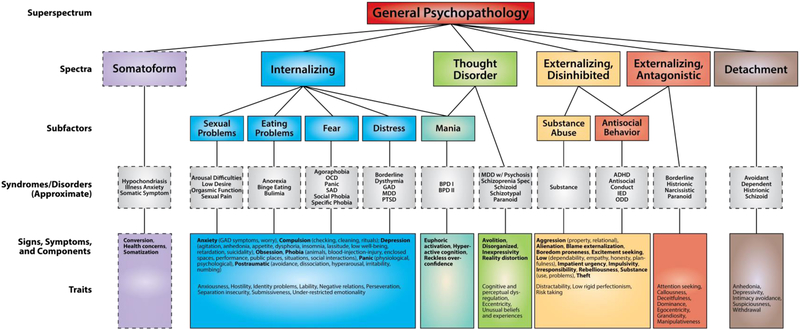

In 2015, a new consortium dedicated to advancing the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) was organized by psychologists and psychiatrists with a shared interest in quantitative nosology of mental illness. Its aim is to develop a common taxonomy based on existing evidence and continuing research with an emphasis on reliability, validity and utility in diagnosis and classification. Unlike traditional nosologies developed by committees, the HiTOP model hews closely to findings of quantitative nosology studies. Consortium members reviewed hundreds of prior studies in both community and clinical samples that investigated structure of psychopathology and its validity. Replicated dimensions were included in the model, those with emerging support were given provisional status, and those with insufficient or inconsistent support were not included. The resulting model—a work still in progress—is summarized in Figure 1, with a case illustration provided in Box 1. This model is not static, as the HiTOP consortium is actively integrating new evidence via a workgroup devoted to ongoing review of the literature and revision of the model.

Figure 1.

HiTOP consortium working model. Constructs higher in the figure are broader and more general, whereas constructs lower in the figure are narrower and more specific. Dashed lines denote provisional elements requiring further study. At the lowest level of the hierarchy (i.e., traits and symptom components), conceptually related signs and symptoms (e.g., phobia) are indicated in bold for heuristic purposes, with specific manifestations indicated in parentheses. ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BPD = bipolar disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; HiTOP = Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology; IED = intermittent explosive disorder; MDD = major depressive disorder; OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; PD = personality disorder; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Box 1. Case illustration.

Differences between categorical and HiTOP conceptualizations are highlighted through a hypothetical case of a 27-year-old woman referred to an outpatient practice by a family member concerned about her increasing social isolation. Comparisons focus on aspects relevant to the diagnostic nosology being used.

Clinical Symptom Presentation

The client presented as guarded, with constricted affect, initially providing only cursory answers. In time, she settled into a conversational tone and maintained appropriate eye contact. She reported feeling depressed most of each day over the last several months. Despite sleeping “all the time” she felt constant fatigue that had her wondering if “a permanent sleep” might bring relief. She had lost interest in activities, was eating less than usual and was attending few social functions. She described having had close friendships, but said she had “burned” many of them, in part because she said she “uses” her friends to get what she wants. She was living alone and was not dating anyone, although she had had brief, chaotic relationships with men in the past. She described excitement (e.g., “on top of the world”) and “getting carried away” at the start of these relationships, but said they often became volatile. Some began after excessive drinking, and most ended poorly. She persisted with attending family functions, where she described feeling evaluated and judged for “looking depressed.” These feelings would prompt anxiety and a desire to flee, upon which she did not act. She noted she would sweat, tremble, and become short of breath and dizzy at the peak of her anxiety. Although this passed within minutes, she was left with a lingering fear that she may be “going crazy.” Even before her recent symptoms, she recalled years of feeling worthless in the eyes of others. She reported once being sexually abused during adolescence but was reluctant to elaborate. She did, however, describe being upset when reminded of it, and said she avoids the neighborhood where it occurred.

Categorical nosology approach

Traditionally, a clinician might start with an interview to assess psychiatric symptoms and psychosocial history, conduct a suicide-risk assessment, and determine the need to rule out symptoms due to a medical condition (e.g. hypothyroidism) or active substance use. A clinician would likely conceptualize the presenting problems from one of various possible theoretical orientations or known risk factors. But at the point of diagnosis, a clinician would entertain a more specific series of alternative (differential) diagnoses if he or she is relying on traditional nosology. In our hypothetical case, this would include criteria related to at least six classes of disorders from the DSM-5: Depressive Disorders, Anxiety Disorders, Bipolar and Related Disorders, Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders, Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders, and Cluster B and C Personality Disorders. Altogether, these six classes encompass 40 possible diagnoses and 88 potential modifiers.

Careful differential review of respective sets of diagnostic criteria takes time. If time is short or the setting is an acute one (e.g. an emergency department), diagnoses may be considered provisional (i.e., to be refined over the course of treatment), or may focus only on the most prominent condition, comparing the case to prototypes, for example (Martinez et al., 2008).

With more time, clinicians can review symptoms more carefully to reach a diagnosis. In our hypothetical case, a clinician takes the time to assess relevant criteria and settles on six traditional diagnoses, remaining provisional with respect to a personality disorder: F32.1 Major Depressive Disorder, single episode, Moderate; F43.10 Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, F40.10 Social Anxiety Disorder, and F41.0 Panic Disorder; provisionally, F60.0 Borderline Personality Disorder, F60.6 Avoidant Personality Disorder.

The clinician would discuss these initial formulations and diagnoses with the patient and review treatment options. Each of the six diagnoses has evidence-based therapies, and there is no clear direction for prioritization, so the clinician may decide to sequence treatment, or to apply a transdiagnostic one. Of course, it is important to realize that there is nothing in these traditional nosologies per se to suggest one approach or the other. To the degree that a clinician believes that the diagnoses are valid representations of different disorders, he or she might decide that each disorder requires its own treatment, although the nosology per se certainly does not require this. Supposing that the patient expressed a preference for psychotherapy over medications, a clinician might begin with cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for depression, followed by CBT for social anxiety and prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD, reserving the possibility of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) for the provisional borderline personality disorder diagnosis. To the degree that indicators of avoidant personality disorder do not resolve after treating the social anxiety disorder, it would require another treatment if a sequenced approach based on diagnosis were followed. Finally, clinicians would coordinate care with other health professionals, and provide for ongoing monitoring (Gelenberg et al., 2010).

HiTOP approach

How would clinical assessment and decision-making differ with a HiTOP approach? As before, a clinician would conduct a diagnostic interview, including a suicide-risk assessment, and investigate the extent to which symptoms were related to a medical condition or active substance use. As before, the assessment can occur within the larger context of a theoretical orientation or evidence-based approach (e.g., Hunsley & Mash, 2007). However, with HiTOP the client’s presenting symptoms are understood from a fundamentally different diagnostic perspective. A clinician does not view presenting symptoms in relation to a specific diagnostic category, so he or she does not look for diagnostic rule-outs related to the fit of symptoms within disorders. Rather, presenting symptoms are conceptualized as related to one another, with varying degrees of overlap and specificity, in a hierarchical scheme.

A clinician could begin by screening for problems within the six higher level spectra. In acute settings (e.g., an emergency department) where time is limited, the assessment may not progress in detail past this level, with determination of elevations for each spectra based on cardinal or prototypic symptoms, or by noting relevant lower level symptom components (e.g., suicidality). As time permits, elevated spectra scores would prompt more nuanced assessment at lower levels of that branch of the hierarchy. In this way, a diagnostician can drill down further depending on the level of detail they wish to achieve or time allows. He or she would also rate psychosocial impairment globally, regardless of symptoms.

In our hypothetical case, the clinician is again in a setting with time for detailed assessment. He or she may initially opt to screen the six spectra and psychological functioning with a questionnaire or brief interview, ideally with population-based norms to specify severity relative to normative values. For example, a routine first step might be to administer the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 – Brief Form (PID-5-BF; Krueger, Derringer, Markon, Watson, & Skodol, 2012), a 25-item measure of pathological traits that are broadly relevant to several HiTOP spectra. It can be used to provide a quick overview of elevated internalizing problems (Negative Affectivity) and antagonistic externalizing problems (Antagonism), and can confirm absence of elevations on other spectra (e.g. thought disorder, as indexed by the PID-5-BF Psychoticism scale). The clinician would also rate the degree of global impairment through an interview or questionnaire (e.g., WHO-DAS; WHO, 2000).

Based on initial screening and interviews, the clinician could then flesh out a more nuanced profile of the lower level dimensions. For the example above, the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS-II; Watson et al., 2012) can be used to specify subdimensions of internalizing symptomatology; the brief form of the Externalizing Spectrum Inventory (ESI-BF; Patrick, Kramer, Krueger, & Markon, 2013) can be used for its antagonism-related symptom subscales; and the PID-5 has additional scales that can be used to assess Negative Affect and Antagonism. For the hypothetical case, administering these instruments would likely reveal elevations on subscales related to dysphoria, appetite loss, suicidality, insomnia, panic, social anxiety, traumatic intrusions and traumatic avoidance, as well as elevated traits of emotional lability, alienation, and manipulativeness.

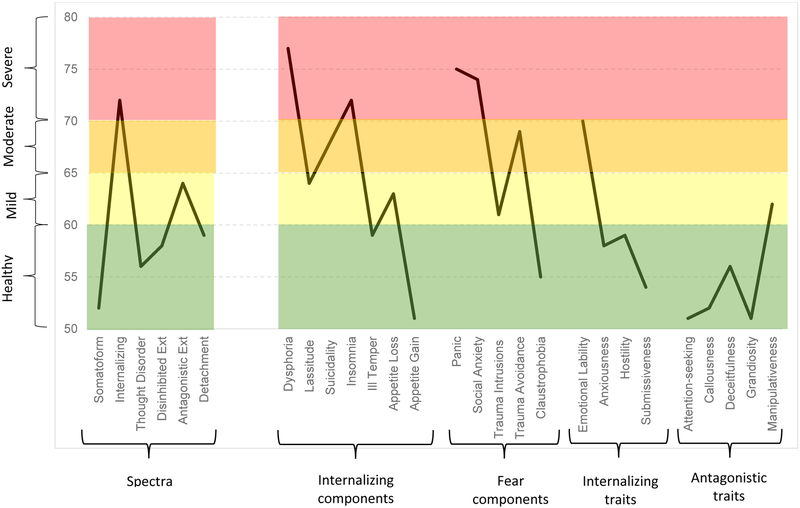

On the assessment report, the clinician would profile the six spectra, indicating which are elevated and providing percentile scores based on normative comparisons when available. Within each spectrum, the clinician would note elevations on lower order symptom and trait dimensions. For example, our hypothetical case would report “Internalizing Spectrum, Severe,” followed by specific lower order symptoms and traits, with norm-based percentiles provided for each. Table 1 briefly contrasts what diagnosis based on the DSM-5 versus HiTOP would look like. Figure 2 provides a profile of relevant HiTOP scales (i.e., spectra are on the left and more narrow components on the right).

The shift in classification approach carries over to treatment planning. Rather than distinct diagnostic categories, the clinician would conceptualize two broad domains for treatment (i.e., internalizing and antagonistic externalizing in this example), with lower order symptoms and traits characterizing nuances within each. Here, the clinician would have flexibility to target narrower symptoms or broader spectra depending on the tools at his or her disposal and patient preferences (e.g., in this case, preference for psychotherapy). HiTOP’s structure naturally suggests the use of transdiagnostic approaches, given that the internalizing symptoms, for example, all cluster together. In our illustrative case, the clinician decides to pair a broad approach for the internalizing symptoms (i.e., transdiagnostic Unified Protocol discussed earlier; Barlow et al., 2017), but a narrow intervention for antagonistic externalizing symptoms (i.e., techniques from interpersonal therapy to target trait manipulativeness).

The HiTOP approach to treatment planning in this illustrative case has at least four benefits. First, comorbidity no longer raises questions over the valid distinction between disorders, but becomes part of the conceptualization. In the illustration, rather than multiple distinct disorders, specific symptoms and traits are conceptualized as part of an internalizing spectrum. Clinicians who use a single therapy for multiple disorders may already be conceptualizing disorders this way. Second, HiTOP resolves the issue of heterogeneity, enabling clinicians to target narrow dimensions if they choose. For example, rather than focus on a heterogeneous category such as borderline personality disorder, a clinician can target specific symptoms or traits (e.g., trait manipulativeness in this illustrative case). The flexibility to determine the level at which to intervene becomes an important feature of the classification. Third, HiTOP explicitly incorporates subthreshold symptoms into its nosology, rather than relying on a single cut point for diagnosis. In our hypothetical case, for example, the clinician could monitor appetite loss as part of the overall treatment plan, and address this if weight loss becomes significant. Fourth, traits from the HiTOP system offer prognostic information to assist planning (Bagby, Gralnick, Al-Dajani, Uliaszek, 2016)—for example, highlighting the degree to which antagonistic externalizing traits may affect the therapeutic alliance (Hirsh, Quilty, Bagby & McMain, 2012).

At the lowest level of the HiTOP hierarchy are sign/symptom components (tightly knit groups of signs and symptoms) and maladaptive traits. Each of these is designed to be a coherent dimension with minimum heterogeneity. Examples would include performance anxiety or social interaction anxiety.

At the next level of the hierarchy are syndromes—constellations of related symptoms, signs, and traits that strongly co-occur. For example, the syndrome of social phobia includes trait submissiveness as well as anxiety about both performance and social interactions. Syndromes do not necessarily map onto DSM-5 or ICD-10 disorders, but they form the HiTOP level that most closely corresponds to them.

At the next hierarchical level up are subfactors, reflecting small clusters of strongly related syndromes. For example, a fear subfactor includes social as well as specific phobia, and also agoraphobia and avoidant personality pathology.

Above this are spectra—broad groups of subfactors that are distinct from one another yet still interrelated. For instance, distress, fear, eating, and sexual problem subfactors (among others) are grouped into an overarching internalizing spectrum. Higher levels beyond spectra are recognized in HiTOP, up to a general psychopathology factor (p) reflecting overall maladaptation (e.g., Caspi & Moffitt, 2018).

HiTOP provides a research-based framework for organizing psychopathology. Already, there is evidence of enhanced validity and reliability compared to more traditional, categorical systems (reviewed in more depth in Kotov et al., 2017; Krueger et al., 2018). However, the full value of the HiTOP model can only be realized if it informs clinical practice (Tyrer, 2018), a major remaining challenge.

Core principles for integrating HiTOP into clinical practice

Three core principles guide integration of HiTOP into practice.

Dimensions with ranges of cutoff scores, not categories.

In the HiTOP framework, patient psychopathology is no longer described in terms of categorical diagnoses. Rather, psychopathology is conceptualized along dimensions with varying degrees of severity. This dimensional aspect pervades every level of HiTOP, from components and traits through spectra and superspectra (Figure 1). HiTOP explicitly acknowledges the clinical reality that no clear divisions are empirically supported between most mental disorders and normality or, oftentimes, even between neighboring disorders (e.g., Clark et al., 2017; Zimmerman et al., 2015). Subsyndromal symptoms are not a shortcoming of the HiTOP nosology, but an inherent feature. Moreover, the concept of “diagnosis” is not one of “present” versus “absent,” but rather a profile that emphasizes the patient’s symptom severity across each component, syndrome and spectrum.

Of course, HiTOP’s adoption of a dimensional perspective in no way precludes the use of categories in clinical practice. For example, it is common in medicine to superimpose data-driven categories (e.g., normal, mild, moderate, or severe) on dimensional measures, such as blood pressure, cholesterol or weight (Kraemer, Noda & O’Hara, 2004). A similar approach can be used with HiTOP. Ranges of cut points can be based on a pragmatic assessment of relative costs and benefits. For instance, in primary care settings, a more liberal (i.e., inclusive or sensitive) threshold can be used for identifying patients requiring more detailed follow-up. Conversely, decisions about more intensive or risky treatments can use a more conservative (i.e., exclusive or specific) threshold. Research has begun to delineate such ranges for some measures (Stasik-O’Brien et al., 2019), but much more is needed to cover the full spectrum.

Most importantly, HiTOP explicitly acknowledges that ranges are pragmatic and not absolute, recognizing the need for flexibility in clinical decision-making. Categorical and dimensional systems can relay equivalent information (Kraemer et al., 2004) as long as cut points are not reified, an approach that is explicit in the HiTOP model.

In the meantime, providers ready to implement HiTOP now can use the template of intelligence testing as a guide for making clinical decisions. For example, decisions about intellectual disability, a dimensional construct with no clear demarcations, involve pairing statistical criteria related to a dimensional construct with impaired psychosocial dysfunction. An IQ lower than 1–2 standard deviations (SDs) from the mean (i.e., in the 85–70 range) commonly serves as the basis for receiving assistance and resources along with a specified level of severity (APA, 2013). Similarly, a statistically based criterion for psychopathology dimensions can be paired with ratings of life-functioning or clinical risk (e.g., suicide potential) to guide intervention.

In practice, this strategy could be partially implemented now (see Box 1 illustration), although it would require validation. Several existing assessment instruments congruent with HiTOP are readily available to clinicians (see https://psychology.unt.edu/hitop), although no single one covers the full range of the model. Almost all measures listed have normative data, which would allow patients’ scores to be converted into standardized T-scores. These scores can then be used as a starting point for clinical decisions (e.g., 60 – 64 being mild, 65 – 69 moderate, 70+ severe). We explore limitations and barriers of this approach more below, but highlight this strategy now simply to underscore that HiTOP’s use of dimensions is entirely consistent with other areas of medicine and could be integrated into practice even now.

Hierarchical nature of illness.

Classification in HiTOP is organized and conceptualized hierarchically. This feature acknowledges that some clinical questions concern narrow forms of psychopathology (e.g., auditory hallucinations in psychosis), whereas others cut across conditions (e.g., elevated neuroticism as a vulnerability to all internalizing disorders; Shackman et al., 2016). From a provider perspective, HiTOP permits a flexible, step-wise approach to assessment, beginning with brief screening of higher order spectra, and then—based on time and need—progressing to more focused assessments to characterize the subfactors, syndromes, and symptoms/traits within each spectrum more fully (e.g., Box 1). This enables clinicians to target a specific level for assessment or intervention.

This flexibility may be especially important across settings with different resources and needs. For example, in acute settings, where assessment time may be limited and clinical decision-making focused on urgent care (e.g., suicide risk; mania), providers can limit assessment to the six higher level spectra or to the most relevant lower level ones. Cardinal or prototypic symptoms can indicate which spectra are elevated—analogous, for example, to diagnosing an unspecified mood disorder. Elevations of higher level spectra can guide treatment planning, either by indicating the need for more granular assessment of spectra components and traits, or by signaling cross-cutting processes common to the target domain. Alternatively or in addition, clinicians can focus on the lower level components most relevant to that setting. In longer term treatment, or with more time, clinicians can cascade down the hierarchy to flesh out more nuanced profiles of narrower, lower order symptoms and traits (e.g. social vs. situational phobia of a fear syndrome).

Naturally, this flexibility raises questions about the optimal level for assessment and intervention. For example, a clinician could decide to intervene at higher levels of the hierarchy, targeting symptoms and processes common to all the components that constitute a spectrum. The Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (Barlow et al., 2017) is one such intervention focused on vulnerability processes (e.g., high negative affect, cognitive processing biases, behavioral avoidance) that are thought to underpin many symptoms within the internalizing spectrum. Similarly, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been shown to be efficacious for multiple internalizing conditions (Martinez, Marangell, & Martinez, 2008) and appear to be effective for subfactors of the spectra (i.e., fear, distress, some eating pathology, etc.). Other spectra can also be targeted by techniques with broad effects (e.g., motivational interviewing for disinhibited externalizing spectral; Lundahl, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson, & Burke, 2010).

Efficacy of these transdiagnostic treatments suggests that shared mechanisms and processes related to higher level spectra may be a parsimonious level for assessment and then intervention, but further research-based evidence is needed to confirm this hypothesis. As a counterpoint, general treatments may be insufficient to address all specific problems; or, treatment of lower-order components can have cascading benefit that could make them better initial targets (e.g., treating sleep improves broader syndromes; Taylor & Pruiksma, 2014). So a clinician could instead focus, for example, on specific sleep symptoms using hypnotic medications (e.g., Kuriyama, Honda, & Hayashino, 2014) or highly specific therapies for sleep problems (e.g., sleep restriction) with more narrow targets of action.

Ultimately, the optimal strategy may be to focus first on the spectra, because interventions that are efficacious for such fundamental problems as negative affectivity or social detachment are likely to provide the patient with maximal benefit, and augment this with additional intervention for syndromes or components that are elevated relative to the corresponding spectrum. However, the existing arsenal of spectra-level treatments is limited and at present the choice may be pragmatic, depending on options available for elevated dimensions and on the therapist’s expertise in these options.1

Impairment rated separately.

Functional impairment is not tied to each specific syndrome in HiTOP, but instead is rated separately and reflects global impairment (e.g., Range of Impaired Functioning Tool, RIFT; Leon et al., 1999 or World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule, WHO-DAS; WHO, 2000). This feature recognizes the practical and psychometrically questionable challenge of disentangling impairment from symptoms, especially when multiple syndromes are present (Gijsen et al., 2001; McKnight & Kashdan, 2009; Ustün & Kennedy, 2009). Impairment can continue to be used to assist with clinical decision-making (e.g. pairing elevated symptoms with an impairment threshold to determine “caseness”), but this is not a necessary condition of the symptom profile.

The explicit inclusion of an impairment-or-distress requirement in DSM for most diagnoses (i.e., the “clinical significance criterion”) reflected an attempt to address concerns over false positives and has been a source of subsequent debate (e.g., Clark et al., 2017; Spitzer & Wakefield, 1999; Ustün & Kennedy, 2009). HiTOP’s conceptual shift away from categories to dimensions allows for this problem to be solved in another way: empirical studies can determine symptom ranges that warrant intervention, and these ranges can be validated against a series of criteria, including impairment but others as well (e.g., future suicide attempts). Of course, it will take time for this body of evidence to develop, and results will likely vary across populations.

Advantages and limitations of HiTOP for clinical practice

A more valid and reliable classification system means little if clinicians do not use it. Although further work is needed, there are at least three ways in which HiTOP has the potential to improve clinical utility, and hence more likely be adopted into practice. We discuss these potential advantages, as well as noting limits for each (cf. Reed, 2010) and outlining needed research.

Enhanced communication.

HiTOP may improve communication. Its dimensional ratings convey more specific information by relaying symptom severity (i.e., percentile scores can now be provided relative to population norms for elevated dimensions) in addition to increasing reliability of a given diagnostic construct (e.g., Markon et al., 2011) In contrast, DSM and ICD typically provide a single dichotomous rating with a diagnostic group including a wide range of severity (see Box 1 for illustration), although efforts have been made to incorporate some severity ratings within both systems (Clark et al., 2017; Kraemer et al., 2012).

HiTOP also provides flexibility to communicate in greater or less detail depending on the level of review, focusing on a relatively small number of elevated spectra or elaborating on specific syndromes, symptoms, or traits as appropriate. The incremental benefit of the latter may be limited, given that one could do something similar with traditional systems (e.g. review diagnostic classes as opposed to individual diagnoses). However, hierarchies in traditional systems have been limited in scope, and often at odds with data (Kotov et al. 2017).

Importantly, surveys of clinicians suggest that practitioners find dimensional diagnosis, at least with respect to personality traits which has most often been studied, informative and workable. For example, clinicians surveyed in recent studies rated dimensional descriptions of personality pathology as better for communication purposes than traditional diagnoses, although the differences were not always statistically significant and prior studies did not always find a clear preference (Glover, Crego, & Widiger, 2012; Hansen et al. in press; Morey, Skodol, & Oldham, 2014).

Improved prognostic power.

HiTOP may provide clinicians with greater prognostic power (Hasler et al., 2004). When compared to categorical diagnoses, dimensional scores show superior prediction of clinical outcomes such as chronicity (Kim & Eaton, 2015), functional impairment (Forbush et al., 2017, 2018; Keyes et al., 2013; Morey et al., 2007, 2012), and physical health comorbidities (e.g., Eaton et al., 2013). HiTOP constructs also show notable links with significant non-disorder outcomes. For instance, the association of internalizing disorders with suicide appears to be driven primarily by commonalties within the spectrum rather than specific disorders (e.g., Eaton et al., 2013).

Despite this promise, more work is needed to confirm improved prognostic power across the range of HiTOP spectra, and that any improvements are clinically significant, not simply statistically so. Moreover, these benefits may not be unique to HiTOP, but may occur for continuous measures of psychopathology generally (e.g., Shankman et al., 2018)

Treatment utility potential.

In the ideal, HiTOP-based assessments would provide better guidance for clinical decision-making and, most importantly, improve outcomes (i.e. enhance the treatment utility of assessment; Hayes, Nelson & Jarrett, 1987). This incremental benefit is not a forgone conclusion, as DSM and ICD have established utility: existing treatment guidelines are based on these diagnoses, categories may seem more aligned with the dichotomous appearance of many clinical actions and existing administrative systems rely on traditional diagnoses. However, these utilities have limitations.

First, community clinicians frequently do not select treatment according to diagnosis (Baldwin & Kosky, 2007; First et al., 2018; Hermes et al., 2013; Mohamed & Rosenheck, 2008; Taylor, 2016), instead they focus on symptoms and presenting complaints. Recent studies found that decision-making of community clinicians is more aligned with HiTOP description than with traditional diagnoses (Hopwood et al., 2019; Rodriguez-Seijas, Eaton, Stohl, Mauro, & Hasin, 2017; Waszczuk et al., 2017). Consequently, HiTOP can provide clinicians with normed, systematic tools to support their preferred practices more effectively than informal interviews on which many providers currently rely.

Importantly, reluctance of clinicians to follow DSM-based practice guidelines may be a rational choice, given shortcomings of traditional diagnoses. The limited ability of the DSM to address the problem of comorbidity resulted in clinical trials being performed in patients who have little comorbidity (e.g., Zimmerman, Mattia, & Posternak et al., 2002), although comorbidity is the norm and may affect patient profiles (e.g., Newman, Moffitt, Caspi, & Silva et al., 1998). Recent efforts to change this practice have seen more generalizable trials for psychotherapy (Franco et al., 2016), but many studies remain focused on unrepresentative cases (Lorenzo-Luaces, Zimmerman & Cuijpers, 2018) especially for pharmacotherapy trials (Franco et al., 2016). This has resulted in multiple, highly similar versions of, for example, Cognitive Therapy (CT)/Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) (e.g., 15 versions of CT/CBT that have each been tested in clinical trials; Society of Clinical Psychology, n.d.). This is not the most efficient use of resources compared to testing and using a single treatment (e.g., Unified Protocol) focused on the common dimension(s) underlying multiple mental-health conditions.

Second, many treatment decisions appear to be categorical (e.g. one either hospitalizes or not; cf. Kraemer et al., 2004) and a dichotomous diagnosis may seem better aligned with this clinical need. However, much more typically, clinical decision-making occurs within a complex and nuanced frame and cannot be reduced to just a few categories, as choices need to be made about degree of care, provider, and treatment modality (Verhuel, 2005). Built-in DSM diagnostic cutoffs may be less useful for such multi-layered and multi-sequenced clinical decision-making. The HiTOP approach enables specification of multiple ranges on a dimension of interest based on research-based evidence, more explicitly underscoring the need for flexibility. More directly to the point, recent clinician surveys with improved methodology show that practitioners find dimensional diagnoses to be more helpful in formulating treatment plans (Glover et al., 2012; Hansen et al. in press; Morey et al., 2014).

Third, DSM and ICD codes are likely to remain the language of administrative systems for years to come. HiTOP profiles can be translated into these codes and we have developed a cross-walk for converting profiles to codes (see below “Barriers” on how this can be addressed).

At this point then, there is consistent but modest evidence that the decision-making of community clinicians aligns better with quantitative diagnoses than traditional diagnoses, such that clinicians may find the former to be more useful clinically. Also, HiTOP’s integrated use of traits and signs/symptoms, rather than treating them as distinct types of disorders, facilitates reconceptualization of psychopathology in a way that builds on their interdependence and relevance for one another (Goldstein, Kotov, Perlman, Watson, Klein et al., 2018), and makes traits a more focal point of treatment.

Finally, HiTOP may help with basic understanding of psychopathology and discovery of new treatments. For example, Harkness and colleagues (2014) have advocated for functional theories that connect psychopathology to evolved adaptive systems; HiTOP’s empirically-derived structure may better scaffold this research and link with those systems. Alternatively, Hofmann and Hayes (2018) advocate for process-oriented treatments and describe how efficacy of these treatments is moderated by relevant patient characteristics. HiTOP’s dimensions may better catalogue these characteristics and provide a platform for discovering relevant processes.

Needed research.

Despite the potential for increased treatment utility, there is no direct evidence yet that implementation of HiTOP diagnoses in clinical settings will improve treatment outcomes (let alone prevent the development of psychopathology) or realize potential synergy with treatment research. We hypothesize that HiTOP will be a better guide for practitioners to optimize treatment, as it provides richer and more precise description of patients, but we need studies that randomize patients to HiTOP assessment versus current “best practice” and treatment as usual conditions to test this hypothesis directly.

Initial examples of novel treatments that map onto HiTOP dimensions and have been found to be efficacious (e.g., Barlow et al., 2017; Norton, 2012) are encouraging. However, many more treatments need to be designed for different elements of HiTOP, including other spectra. The heterogeneity of traditional diagnostic categories can weaken and obscure the benefit of a given treatment. With HiTOP, clinical interventions can instead be evaluated with respect to the specificity of effects. Whether improved outcomes can be realized for all elements of the model, or just some, remains to be investigated.

Ultimately, new HiTOP-based treatments will need to be evaluated with randomized clinical trials before it will be clear whether HiTOP is more effective in guiding treatment than traditional systems. It is possible that for some forms of psychopathology, especially conditions for which highly efficacious treatments already exist (e.g., panic disorder), that HiTOP-based treatment research will not improve outcomes. Nevertheless, even in these domains, HiTOP can reduce the number treatments that need to be considered by identifying a smaller set of interventions acting at more general levels but with efficacy comparable to syndrome-specific treatments.

Barriers to the integration of HiTOP into practice

Integration of a diagnostic model like HiTOP into clinical practice faces significant barriers and concerns. We address eight prominent questions raised by these concerns here.

Is HiTOP harder to communicate to patients and providers?

HiTOP communicates clinical problems based on psychopathological profiles rather than categorical diagnoses. Explaining the meaning of higher level profiles can be more parsimonious than listing multiple, comorbid diagnoses. In turn, lower levels are analogous to communicating about symptoms. The hierarchical structure accommodates clinical complexity but also provides a flexible model for conceptualization and communication. The use of profiles, however, may initially present as more complicated to communicate for clinicians who are not accustomed to them. We believe familiarity will resolve this issue over time. Data indicating that clinicians find dimensional models of personality acceptable or even preferred for communicating (Glover et al., 2012; Hansen et al. in press; Morey et al., 2014), suggest that potential initial resistance to HiTOP based on it being viewed as more complex to communicate can be overcome as a barrier to integration.

Are there measures for assessing psychopathology within a HiTOP framework?

Many measures consistent with HiTOP nosology are already widely available and used in clinical practice (e.g., Achenbach et al., 2017; Clark, Simms, Wu, & Casillas, 2014; Krueger et al., 2012; Morey, 2007a). For example, the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) originated in the 1960’s in work with children and revealed dimensional syndromes organized into the higher order groupings of Internalizing, Externalizing, and Severe/Diffuse Psychopathology (Achenbach et al., 2017). Based on subsequent work over 50 years, ASEBA now has measures with norms that cover the lifespan and have been adapted for use in multiple languages and cultures (Achenbach et al., 2017). A HiTOP website (https://hitop.unt.edu) provides examples of other measures consistent with HiTOP.

However, no single measure listed on our website fully captures the HiTOP model. Several can be combined to cover most of it, and the consortium is piloting versions of these batteries (available upon request). The HiTOP website provides an illustration of a battery that can be created today from existing instruments, all with measures that have normative data. The consortium is also in the middle stages of rigorously developing a free, omnibus HiTOP instrument, which is being tested at multiple sites with diverse samples, but this may not be available for some time.

Will HiTOP-based assessment take too long or not be feasible?

The hierarchical nature of HiTOP allows clinicians to take a stepwise approach, starting at higher levels and cascading downward as time permits and need requires. Much like a classic “review of systems” performed in general medicine (cf. Harkness, Reynolds, & Lilienfeld, 2014), such a stepwise approach facilitates comprehensive evaluation at higher levels, which can be more efficient than review of criteria for multiple categorical disorders.

Moreover, many components can be assessed by self-report measures described earlier, which can be administered and scored simply and efficiently (although interviews are also available for many domains, if preferred). These can mitigate the issue of feasibility by reducing provider burden without necessarily compromising validity (Samuel et al., 2013; Samuel, Suzuki, & Griffin, 2016).

Nevertheless, adoption of a fully dimensional system will face the burdens of administering and scoring dimensional measures, which would be particularly problematic for acute settings. To overcome this barrier, integration of assessment instruments with newer technologies is critical. Computerized adaptive testing, and administration via internet portals or smartphone applications, can reduce burden and increase the clinical utility of dimensional systems. Such second-generation advances exist for several instruments congruent with HiTOP, but more work is needed to make these fully available and easily integrated into diverse practice settings.

Are there validated “cutoffs” for use in determining the need for treatment?

With only a few exceptions, empirically determined cut points for guiding treatment decision-making remain rare for HiTOP as well as for DSM-5 or ICD-10. Although a practical barrier for all systems, it also underscores a compelling impetus for HiTOP: Using a hierarchical and dimensional system of measurement allows one to fine-tune assessments based on research in the field, and move away from a “one size fits all” cut point typically associated with dichotomous diagnoses. Although this will take time, we believe that the resulting ranges and cut points may be clinically meaningful, show increased sensitivity, and may fit more naturally into “stepped-care” models (cf. van Straten, Hill, Richards, & Cuijpers, et al., 2015).

Can HiTOP be used in conjunction with DSM/ICD-based assessment protocols?

Some HiTOP principles can be integrated with DSM/ICD-based assessments. DSM-5 began taking steps toward quantitative nosology by grouping similar syndromes into diagnostic classes, such as the autism and schizophrenia spectra, and by incorporating the DSM-5 alternative model for personality disorder, which is a functioning-and-trait-based diagnostic system. Many DSM-5 disorders could be regrouped into classes consistent with HiTOP spectra, and conceptualized as part of a hierarchy (e.g. grouping depressive with generalized anxiety disorder as part of a distress subfactor, which was considered for DSM-5, but ultimately not adopted). Disorder criteria can also be scored continuously as symptom counts and used as severity indicators (e.g., Shankman et al., 2018), as is done now for DSM-5 substance use disorders. Doing so provides some benefit over categories, although resulting scales would not map precisely onto HiTOP’s dimensions because of the greater heterogeneity of many diagnoses. Such modifications would not be equivalent to a HiTOP approach, but nonetheless demonstrate how clinicians could begin to integrate HiTOP’s underlying principles into case conceptualization without changing their assessment protocols.

Is HiTOP appropriate for youth?

A number of studies have supported components of a hierarchical model in youth (Achenbach et al., 2017; Laceulle, Vollebergh, & Ormel, 2015; Lahey, Van Hulle, Singh, Waldman, & Rathouz, 2011) and assessment tools exist for diverse ages. ASEBA, for example, has instruments specifically for children. Other instruments consistent with HiTOP have adolescent versions (e.g., Butcher et al., 1992; Linde, Stringer, Simms, & Clark, 2013; Morey, 2007b) and some were developed expressly for children and adolescents (e.g., De Clercq, De Fruyt, Van Leeuwen, & Mervielde, 2006). However, the bulk of evidence to support the HiTOP model has come from adults and more work is needed to support the model from a developmental psychopathology perspective, including youth. Hence, HiTOP-consistent approaches to classification can be integrated into the assessment and treatment of youth, but more work is needed in this area.

How can a clinician using HiTOP be reimbursed?

Reimbursement is often tied to ICD codes (i.e., an ICD diagnostic code must be submitted for an encounter for clinician to be paid). Every diagnostic grouping in ICD includes an “unspecified” category for cases that do not meet the diagnostic criteria for a specific disorder within that grouping or for patients for whom clinicians choose not to provide a specific code. Thus, the appropriate “unspecified” categories that correspond to the patient’s presenting symptoms can be used to meet administrative requirements. The HiTOP Clinical Translation Workgroup has developed a free HiTOP-ICD crosswalk (available upon request) to facilitate clinicians using HiTOP in their practice by linking HiTOP domains to ICD codes for billing and administrative purposes (e.g., the illustrative case described with the profile in Figure 2 could be given ICD codes F39, F41.9, F51.9, F60.9). This approach has limitations, but can provide a solution until billing and administrative procedures are better aligned with quantitative nosology.

Figure 2.

Standardized HiTOP profile for the fictional case described in Box 1. The Y-axis indicates normalized t-scores (M = 50, SD = 10) for select dimensions relevant to the case.

How can HiTOP be incorporated into training?

With time, we anticipate that diagnostic manuals may transition to a dimensional approach along the lines of HiTOP. For example, ICD recently adopted a dimensional perspective for personality (Tyrer, Mulder, Kim, & Crawford, 2019). However, until that time, many courses in psychopathology will likely continue to be organized around categorical DSM/ICD models, which creates challenges for incorporating HiTOP into training. We suggest a transition with respect to training that mirrors the transition in clinical practice. The HiTOP model incorporates DSM-like constructs, partitioning them into smaller (e.g., sign/symptom component) and larger (e.g., spectra) units in a hierarchical fashion. In our experience, this mapping is readily learned, making it straightforward to teach students the DSM categories for practical (and, we hope, temporary) purposes, while familiarizing them simultaneously with evidence-based hierarchical models. The connection between dimensional and categorical diagnosis is also easily grasped. As discussed earlier, it is common for students to learn how to apply cut scores along recognized continua, such as blood pressure or intellectual functioning, or with instruments commonly taught as part of psychological assessment training. Thus, students can be taught to think about diagnostic cut scores for psychopathology diagnosis in the same way.

Conclusions

Features of an alternative classification system based on quantitative methods are becoming increasingly clear and offer advantages over traditional nosology. The hierarchical-dimensional classification approach described here—the HiTOP system—is characterized by six overarching spectra of mental disorder, each encompassing more narrowly defined and more homogenous elements, consisting of narrower sign/symptom components and traits. Our aims in this article have been to describe major principles for integrating HiTOP into clinical practice, to introduce tools that can assist clinicians, and to illustrate what such an integration might look like. HiTOP has several advantages over traditional nosology that may improve clinical utility, and clinicians may already be practicing with several of its principles in mind. However, the system shares some limitations of traditional nosology and may introduce new ones, so more work is needed to prove its utility for improving patient care.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Illustrative Diagnoses for DSM-5 versus HiTOP

| DSM-5 | HiTOP |

|---|---|

|

|

Note. Percentiles reflect scores relative to normative distribution and would come from test scores when available.

Significance:

Redefining a taxonomy of psychopathology according to data results in dimensions, not categories, that can be organized hierarchically—with at least six higher level spectra near the top of the model and more specific lower level components and traits at the bottom. This approach may improve case conceptualizations and align more closely with transdiagnostic treatments, while also specifying more narrow targets for intervention. Case illustration shows how the HiTOP model can be used in clinical practice today, although additional research is needed to fully assess the utility of this approach for providers and patients.

Author acknowledgements

This article was organized by members of the HiTOP Consortium, a grassroots organization open to all qualified investigators (https://medicine.stonybrookmedicine.edu/HITOP). AJS was supported by the National Institutes of Health (DA040717 and MH107444) and the University of Maryland.

Footnotes

It is worth highlighting that traits play an important role in HiTOP-related treatment planning. Notably, HiTOP recognizes the joint structure of traits and symptoms (e.g., Klein, Kotov, & Bufferd, 2011; Ormel et al., 2013), ensuring they are both considered in conceptualizing cases and in treatment. HiTOP remains agnostic about how particular traits affect specific components or vice versa, instead grouping those that co-occur and providing a platform for future research to specify these interactions, or how traits may moderate effects of treatment on particular components. Such decisions will be guided based on what treatments are available to a clinician and the evidence for the range of their effects, an evidence base that needs to be greatly expanded to improve care. For example, certain treatments are particularly effective in promoting personality change (e.g., Hudson & Fraley, 2015; Roberts et al. 2017), which in turn can improve other mental health symptoms (e.g., Conrod et al., 2013; Zinbarg, Uliaszek, & Adler et al., 2008). Alternatively, explication of traits can guide clinicians in matching treatments to patient’s personality vulnerabilities, as they have been found to moderate therapeutic process (e.g., traits related to agreeableness moderate efficacy of behavioral therapy for distress; Kushner, Quilty, Uliaszek, McBride, & Bagby, 2016; Samuel, Bucher, & Suzuki et al., 2018).

References

- Achenbach TM, Ivanova MY, & Rescorla LA (2017). Empirically based assessment and taxonomy of psychopathology for ages 1½−90+ years: Developmental, multi-informant, and multicultural findings. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 79, 4–18. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2006). American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: Compendium 2006. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bagby RM, Gralnick TM, Al-Dajani N, & Uliaszek AA (2016). The Role of the Five-Factor Model in Personality Assessment and Treatment Planning. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 23(4), 365–381. 10.1111/cpsp.12175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin DS, & Kosky N (2007). Off-label prescribing in psychiatric practice. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 13(6), 414–422. 10.1192/apt.bp.107.004184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Bullis JR, Gallagher MW, Murray-Latin H, Sauer-Zavala S, … & Cassiello-Robbins C (2017). The Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders Compared With Diagnosis-Specific Protocols for Anxiety Disorders: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 74(9), 875–884. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Sauer-Zavala S, Carl JR, Bullis JR, & Ellard KK (2013). The nature, diagnosis, and treatment of neuroticism: Back to the future. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(3), 344–365. 10.1177/2167702613505532 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardini F, Attademo L, Cleary SD, Luther C, Shim RS, Quartesan R, & Compton MT (2017). Risk prediction models in psychiatry: toward a new frontier for the prevention of mental illnesses. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(5), 572–583. 10.4088/JCP.15r10003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler LE, & Malik ML (2002). Rethinking the DSM: A psychological perspective. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 10.1037/10456-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blashfield RK (1984). The Classification of Psychopathology. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 10.1007/978-1-4613-2665-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blashfield RK, & Herkov MJ (1996). Investigating clinician adherence to diagnosis by criteria: A replication of Morey and Ochoa (1989). Journal of Personality Disorders, 10(3), 219–228. 10.1521/pedi.1996.10.3.219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bostic JQ, & Rho Y (2006). Target-symptom psychopharmacology: between the forest and the trees. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 15(1), 289–302. 10.1016/j.chc.2005.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun SA, & Cox JA (2005). Managed mental health care: Intentional misdiagnosis of mental disorders. Journal of Counseling & Development, 83(4), 425–433. 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00364.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruchmüller K, Margraf J, & Schneider S (2012). Is ADHD diagnosed in accord with diagnostic criteria? Overdiagnosis and influence of client gender on diagnosis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(1), 128–138. 10.1037/a0026582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher JN, Williams CL, Graham JR, Archer RP, Tellegen A, Ben-Porath YS, & Kaemmer B (1992). The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-Adolescent (MMPI-A): Manual for administration and scoring. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 10.1037/t15122-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carragher N, Krueger RF, Eaton NR, Markon KE, Keyes KM, Blanco C, … & Hasin DS (2014). ADHD and the externalizing spectrum: direct comparison of categorical, continuous, and hybrid models of liability in a nationally representative sample. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(8), 1307–1317. 10.1007/s00127-013-0770-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, & Moffitt TE (2018). All for one and one for all: Mental disorders in one dimension. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(9), 831–844. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17121383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski M, Clark LA, Bagby RM, & Watson D (2015). Method matters: Understanding diagnostic reliability in DSM-IV and DSM-5. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(3), 764–769. 10.1037/abn0000069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Cuthbert B, Lewis-Fernández R, Narrow W, & Reed GM (2017). ICD-11, DSM-5, and RDoC: Three approaches to understanding and classifying mental disorder. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 18(2), 72–145. 10.1177/1529100617727266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Simms LJ, Wu KD, & Casillas A (2014). Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality, 2nd Edition (SNAP-2): Manual for administration, scoring, and interpretation. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D, & Reynolds S (1995). Diagnosis and classification of psychopathology: Challenges to the current system and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 46(1), 121–153. 10.1146/annurev.ps.46.020195.001005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, O’Leary-Barrett M, Newton N, Topper L, Castellanos-Ryan N, Mackie C, & Girard A (2013). Effectiveness of a selective, personality-targeted prevention program for adolescent alcohol use and misuse: a cluster randomized controlled trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(3), 334–342. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq B, De Fruyt F, Van Leeuwen K, & Mervielde I (2006). The structure of maladaptive personality traits in childhood: A step toward an integrative developmental perspective for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115, 639–657. 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Markon KE, Keyes KM, Skodol AE, Wall M, … & Grant BF (2013). The structure and predictive validity of the internalizing disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(1), 86–92. 10.1037/a0029598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen K, & Kress VE (2004). Beyond the DSM Story: Ethical Quandaries, Challenges, and Best Practices. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ (1944). Types of personality: a factorial study of seven hundred neurotics. Journal of Mental Science, 90(381), 851–861. 10.1192/bjp.90.381.851 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Bhat V, Adler D, Dixon L, Goldman B, Koh S, … & Siris S (2014). How do clinicians actually use the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in clinical practice and why we need to know more. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 202(12), 841–844. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Rebello TJ, Keeley JW, Bhargava R, Dai Y, Kulygina M, … & Reed GM (2018). Do mental health professionals use diagnostic classifications the way we think they do? A global survey. World Psychiatry, 17(2), 187–195. 10.1002/wps.20525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbush KT, Chen PY, Hagan KE, Chapa DA, Gould SR, Eaton NR, & Krueger RF (2018). A new approach to eating‐disorder classification: Using empirical methods to delineate diagnostic dimensions and inform care. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(7), 710–721. 10.1002/eat.22891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbush KT, Hagan KE, Kite BA, Chapa DA, Bohrer BK, & Gould SR (2017). Understanding eating disorders within internalizing psychopathology: A novel transdiagnostic, hierarchical-dimensional model. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 79, 40–52. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulds GA. (1976). The Hierarchical Nature of Personal Illness. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Franco S, Hoertel N, McMahon K, Wang S, Rodríguez-Fernández JM, Peyre H, … & Blanco C (2016). Generalizability of Pharmacologic and Psychotherapy Clinical Trial Results for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder to Community Samples. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77(8), 975–981. 10.4088/JCP.15m10060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galatzer-Levy IR, & Bryant RA (2013). 636,120 ways to have Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(6), 651–662. 10.1177/1745691613504115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, Rosenbaum JF, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, … & Schneck CD (2010). Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder, third edition Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gijsen R, Hoeymans N, Schellevis FG, Ruwaard D, Satariano WA, & van den Bos GA (2001). Causes and consequences of comorbidity: a review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(7), 661–674. 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00363-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover NG, Crego C, & Widiger TA (2012). The clinical utility of the Five Factor Model of personality disorder. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 3, 176–184. 10.1037/a0024030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BL, Kotov R, Perlman G, Watson D, Klein DN (2018). Trait and facet-level predictors of first-onset depressive and anxiety disorders in a community sample of adolescent girls. Psychological Medicine, 48(8), 1282–1290. 10.1017/S0033291717002719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen SJ, Christensen S, Kongerslev MT, First MB, Widiger TA, Simonsen E, & Bach B (in press). Mental health professionals’ perceived clinical utility of the ICD-10 versus ICD-11 classification of personality disorders. Personality and Mental Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness AR, Reynolds SM, & Lilienfeld SO (2014). A review of systems for psychology and psychiatry: Adaptive systems, personality psychopathology five (PSY-5), and the DSM-5. Journal of Personality Assessment, 96, 121–139. 10.1080/00223891.2013.823438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam N, Holland E, & Kuppens P (2012). Categories versus dimensions in personality and psychopathology: a quantitative review of taxometric research. Psychological Medicine, 42(5), 903–920. 10.1017/S0033291711001966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasler G, Drevets WC, Manji HK, & Charney DS (2004). Discovering endophenotypes for major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology, 29(10), 1765–1781. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Nelson RO, & Jarrett RB (1987). The treatment utility of assessment: A functional approach to evaluating assessment quality. American Psychologist, 42(11), 963–974. 10.1037/0003-066X.42.11.963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermes ED, Sernyak M, & Rosenheck R (2013). Use of second-generation antipsychotic agents for sleep and sedation: a provider survey. Sleep, 36(4), 597–600. 10.5665/sleep.2554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh JC, Quilty LC, Bagby RM, & McMain SF (2012). The relationships between agreeableness and the development of the working alliance in patients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 26(4), 616–627. 10.1521/pedi.2012.26.4.616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, & Hayes SC (2018). The future of intervention science: Process-based therapy. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(1), 37–50. 10.1177/2167702618772296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood C, Bagby RM, Gralnick TM, Ro E, Ruggero C, Mullins-Sweatt S, … & Patrick CJ (2019). Integrating psychotherapy with the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP). Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, in press. Advance online publication. 10.31234/osf.io/jb8z4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson NW, & Fraley RC (2015). Volitional personality trait change: Can people choose to change their personality traits? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(3), 490–507. 10.1037/pspp0000021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsley J, & Mash EJ (2007). Evidence-based assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 29–51. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendell R, & Jablensky A (2003). Distinguishing between the validity and utility of psychiatric diagnoses. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(1), 4–12. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, & Solomon M (2016). Expert consensus v. evidence-based approaches in the revision of the DSM. Psychological Medicine, 46(11), 2255–2262. 10.1017/S003329171600074X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent GH, & Rosanoff AJ (1910). A study of association in insanity. American Journal of Psychiatry, 67(2), 317–390. 10.1176/ajp.67.2.317 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Eaton NR, Krueger RF, Skodol AE, Wall MM, Grant B, … & Hasin DS (2013). Thought disorder in the meta-structure of psychopathology. Psychological Medicine, 43(8), 1673–1683. 10.1017/S0033291712002292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, & Eaton NR (2015). The hierarchical structure of common mental disorders: Connecting multiple levels of comorbidity, bifactor models, and predictive validity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(4), 1064–1078. 10.1037/abn0000113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Kotov R, & Bufferd SJ (2011). Personality and depression: explanatory models and review of the evidence. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 269–295. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Chang S-W, Fochtmann LJ, Mojtabai R, Carlson GA, Sedler MJ, & Bromet E (2011a). Schizophrenia in the internalizing-externalizing framework: a third dimension?. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 37(6), 1168–1178. 10.1093/schbul/sbq024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D, Achenbach TM, Althoff RR, Bagby RM, … & Zimmerman M (2017). The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(4), 454–477. 10.1037/abn0000258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Ruggero CJ, Krueger RF, Watson D, Yuan Q, & Zimmerman M (2011b). New dimensions in the quantitative classification of mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(10), 1003–1011. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ, Clarke DE, Narrow WE, & Regier DA (2012). DSM-5: how reliable is reliable enough?. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(1), 13–15. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Noda A, & O’Hara R (2004). Categorical versus dimensional approaches to diagnosis: methodological challenges. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 38(1), 17–25. 10.1016/S0022-3956(03)00097-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Derringer J, Markon KE, Watson D, & Skodol AE (2012). Initial construction of a maladaptive personality trait model and inventory for DSM-5. Psychological Medicine, 42(9), 1879–1890. 10.1017/S0033291711002674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Kotov R, Watson D, Forbes MK, Eaton NR, Ruggero CJ, … & Bagby RM (2018). Progress in achieving quantitative classification of psychopathology. World Psychiatry, 17(3), 282–293. 10.1002/wps.20566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama A, Honda M, & Hayashino Y (2014). Ramelteon for the treatment of insomnia in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine, 15(4), 385–392. 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.11.788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner SC, Quilty LC, Uliaszek AA, McBride C, & Bagby RM (2016). Therapeutic alliance mediates the association between personality and treatment outcome in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 201, 137–144. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laceulle OM, Vollebergh WA, & Ormel J (2015). The structure of psychopathology in adolescence replication of a general psychopathology factor in the TRAILS Study. Clinical Psychological Science, 3(6), 850–860. 10.1177/2167702614560750 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Van Hulle CA, Singh AL, Waldman ID, & Rathouz PJ (2011). Higher-order genetic and environmental structure of prevalent forms of child and adolescent psychopathology. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(2), 181–189. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Solomon DA, Mueller TI, Turvey CL, Endicott J, & Keller MB (1999). The Range of Impaired Functioning Tool (LIFE–RIFT): a brief measure of functional impairment. Psychological Medicine, 29(4), 869–878. 10.1017/S0033291799008570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linde JA, Stringer D, Simms LJ, & Clark LA (2013). The Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality for Youth (SNAP-Y) A New Measure for Assessing Adolescent Personality and Personality Pathology. Assessment, 20(4), 387–404. 10.1177/1073191113489847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Luaces L, Zimmerman M, & Cuijpers P (2018). Are studies of psychotherapies for depression more or less generalizable than studies of antidepressants?. Journal of Affective Disorders, 234, 8–13. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorr M, Klett CJ, & McNair DM (1963). Syndromes of Psychosis. New York, NY: Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, & Burke BL (2010). A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice, 20(2), 137–160. 10.1177/1049731509347850 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Machado PP, Machado BC, Gonçalves S, & Hoek HW (2007). The prevalence of eating disorders not otherwise specified. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(3), 212–217. 10.1002/eat.20358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE (2010). Modeling psychopathology structure: A symptom-level analysis of Axis I and II disorders. Psychological Medicine, 40(2), 273–288. 10.1017/S0033291709990183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE, Chmielewski M, & Miller CJ (2011). The reliability and validity of discrete and continuous measures of psychopathology: a quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 137(5), 856–879. 10.1037/a0023678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez M, Marangell LB, & Martinez JM (2008). Psychopharmacology In Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, & Gabbard GO (Eds.), The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry, Fifth Edition Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR (2013). Exploring trait assessment of samples, persons, and cultures. Journal of Personality Assessment, 95(6), 556–570. 10.1080/00223891.2013.821075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight PE, & Kashdan TB (2009). The importance of functional impairment to mental health outcomes: a case for reassessing our goals in depression treatment research. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(3), 243–259. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead MA, Hohenshil TH, & Singh K (1997). How the DSM system is used by clinical counselors: A national study. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 19(4), 383–401. No doi. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed S, & Rosenheck RA (2008). Pharmacotheray of PTSD in the US Department of Veterans Affairs: diagnostic- and symptom-guided drug selection. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(6), 959–965. 10.4088/JCP.v69n0611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TV (1930). The empirical determination of certain syndromes underlying praecox and manic-depressive psychoses. American Journal of Psychiatry, 86(4), 719–738. 10.1176/ajp.86.4.719 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC (2007a). Professional manual for the Personality Assessment Inventory (2nd ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC (2007b). Personality Assessment Inventory – Adolescent (PAI-A). Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC, & Benson KT (2016). An investigation of adherence to diagnostic criteria, revisited: clinical diagnosis of the DSM-IV/DSM-5 section II personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 30(1), 130–144. 10.1521/pedi_2015_29_188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC, Hopwood CJ, Gunderson JG, Skodol AE, Shea MT, Yen S, … & McGlashan TH (2007). Comparison of alternative models for personality disorders. Psychological Medicine, 37(7), 983–994. 10.1017/S0033291706009482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC, Hopwood CJ, Markowitz JC, Gunderson JG, Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, … Skodol AE (2012). Comparison of alternative models for personality disorders, II: 6-, 8- and 10-year follow-up. Psychological Medicine, 42(8), 1705–1713. 10.1017/S0033291711002601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC, & Ochoa ES (1989). An investigation of adherence to diagnostic criteria: Clinical diagnosis of the DSM-III personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 3(3), 180–192. 10.1521/pedi.1989.3.3.180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC, Skodol AE, & Oldham JM (2014). Clinician judgments of clinical utility: A comparison of DSM-IV-TR personality disorders and the alternative model for DSM-5 personality disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(2), 398–405. 10.1037/a0036481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins-Sweatt SN, & Widiger TA (2009). Clinical utility and DSM-V. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 302–312. 10.1037/a0016607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman DL, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, & Silva PA (1998). Comorbid mental disorders: Implications for treatment and sample selection. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(2), 305–311. 10.1037/0021-843X.107.2.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]