Abstract

Previous studies have shown a high level of noncompliance with recommendations on breastfeeding duration, especially in France. The objective was to describe the association between breastfeeding initiation and duration and the statutory duration of postnatal maternity leave, the gap between the end of legal maternity leave and the mother's return to work, and maternal working time during the first year post‐partum. Analyses were based on 8,009 infants from the French nationwide ELFE cohort. We assessed the association with breastfeeding initiation by using logistic regression and, among breastfeeding women, with categories of breastfeeding duration by using multinomial logistic regression. Among primiparous women, both postponing return to work for at least 3 weeks after statutory postnatal maternity leave (as compared with returning to work at the end of the statutory period) and working less than full‐time at 1 year post‐partum (as compared with full‐time) were related to higher prevalence of breastfeeding initiation. Among women giving birth to their first or second child, postponing the return to work until at least 15 weeks was related to a higher prevalence of long breastfeeding duration (at least 6 months) as compared with intermediate duration (3 to <6 months). Working part‐time was also positively related to breastfeeding duration. Among women giving birth to their third child or more, working characteristics were less strongly related to breastfeeding duration. These results support extending maternity leave or working time arrangements to encourage initiation and longer duration of breastfeeding.

Keywords: breastfeeding, cohort, epidemiology, longitudinal, maternity leave

Key messages.

Our study provides insights into the influence of maternity or parental leave on the initiation and duration of breastfeeding among French women who worked during pregnancy. French regulations regarding maternity and parental leave differ by occupational status, multiple or single birth, parity, and gestational age.

Our findings highlight that in the context of statutory postnatal maternity leave of about 10 weeks, postponing the maternal return to work and reducing working time to part‐time during the first year post‐partum is related to higher initiation prevalence and longer duration of breastfeeding.

1. INTRODUCTION

Most international paediatric societies recommend exclusively breastfeeding until a child reaches 6 months of age (Agostoni et al., 2009; Section on Breastfeeding, 2012; World Health Organization, 2002), and the WHO recommends also continuation of breastfeeding for at least 2 years (World Health Organization, 2002). However, results from various studies of infant feeding practices have shown a high level of noncompliance with these recommendations. For instance, the prevalence of any breastfeeding initiation (defined as the infant receiving any amount of breast milk) was 83% in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018; Rossen, Simon, & Herrick, 2015) for babies born in 2015, 81% in the United Kingdom (McAndrew et al., 2012) for babies born in 2010, but only 70% in France (Kersuzan et al., 2014) for babies born in 2011. Furthermore, the prevalence of any breastfeeding declined rapidly with infant age, and at 6 months, the prevalence of any breastfeeding decreased to 58% in the United States, 34% in the United Kingdom, and only 19% in France (McAndrew et al., 2012; Rossen et al., 2015; Wagner et al., 2015).

Several studies have tried to identify the factors that could explain low breastfeeding rates in France (Bonet et al., 2013; Kersuzan et al., 2014; Salanave, de Launay, Guerrisi, & Castetbon, 2012; Wagner et al., 2015; Wagner et al., 2019). In particular, we recently highlighted that previous experience with breastfeeding was strongly associated with breastfeeding initiation (Wagner et al., 2019). Although having been breastfed as an infant was a key factor in breastfeeding initiation among primiparous mothers, having breastfed previous children was the most significant predictor among multiparous mothers. However, the relationship between previous breastfeeding experience and subsequent breastfeeding behaviour was not as strong for breastfeeding duration. One factor commonly suggested to explain why women did not breastfeed for as long as recommended is the difficulty to combine breastfeeding and working, especially in France, where maternal employment is relatively frequent (Baranowska‐Rataj & Matysiak, 2016). In France, few studies have investigated the association between maternity leave policies and breastfeeding practices. Scarce available studies have yielded mixed results (Bonet et al., 2013; Wallace et al., 2013). Furthermore, none has investigated the complexity and also the flexibility of the French maternal leave policy (Pénet, 2006) in association with breastfeeding practices. In fact, for a single birth, women covered by the general health insurance system are entitled to a maximum of 16 weeks (6 weeks before and 10 weeks after delivery) of fully paid maternity leave (Gouvernement français, in force in 2011a). For women with two previous children, this duration is extended to 26 weeks (8 for prenatal and 18 for postnatal leave; Gouvernement français, in force in 2011a). Upon medical agreement, the starting date of fully paid prenatal leave can be shifted up to 3 weeks to extend fully paid postnatal leave (Gouvernement français, in force in 2011a). This fully paid maternity leave may be extended by a parental leave (Gouvernement français, in force in 2011c), partially paid for 6 months for primiparous women or up to the child's first 3 years for multiparous women, that can be used to postpone the return to work or to reduce working time to part‐time. The length of maternity or parental leave does not depend on maternal working time during pregnancy, but the amount of the compensation that should be paid during maternity or parental leave is proportional to the salary before pregnancy. For self‐employed women (covered by the health insurance system for self‐employed people), the total duration of paid maternity leave is limited to 8 weeks.

Studies of the relationship between maternity leave, employment, and breastfeeding practices conducted in other high‐income countries have produced mixed results. In fact, the maternal plan to work full‐time post‐partum has been related to a lower likelihood to initiate breastfeeding (Fein & Roe, 1998; Kurinij, Shiono, Ezrine, & Rhoads, 1989; Mandal, Roe, & Fein, 2010). Similarly, women who planned to return to work before 6 weeks post‐partum (Noble, 2001) or before 1 month post‐partum (Chuang et al., 2010) were less likely to initiate breastfeeding, but planning to go back to work within 6 months post‐partum was not related to breastfeeding initiation. Furthermore, a later return to work appeared positively related to breastfeeding duration whatever the child's age considered: 2–3 months (Bai, Fong, & Tarrant, 2015; Gielen, Faden, O'Campo, Brown, & Paige, 1991), 6–7 months (Chuang et al., 2010; Kurinij et al., 1989), or 1 year (Visness & Kennedy, 1997) but not in all studies (Logan et al., 2016). In a U.S. study, total maternity leave available (summing fully paid, partially paid, and unpaid) was not clearly related to breastfeeding initiation or duration, but maternal return to work before 12 weeks (partially or full‐time) or full‐time after 12 weeks was related to reduced breastfeeding duration (Mandal et al., 2010). However, a recent review highlighted that the level of evidence for the association between early cessation of breastfeeding and a return to work within 12 weeks post‐birth is low (Mangrio, Persson, & Bramhagen, 2017). Data from the U.K. Millennium Cohort Study (Hawkins, Griffiths, Dezateux, & Law, 2007a; Hawkins, Griffiths, Dezateux, & Law, 2007b) found that mothers who were employed full‐time were less likely to initiate breastfeeding than were women who were students or not employed. Among employed mothers, those who returned to work within the first 4 months post‐partum or for financial reasons were less likely to initiate breastfeeding. Significant variation in how the maternity leave policy is structured across high‐income countries, and methodological heterogeneity could explain differences in results across studies. In fact, legal maternity leave duration varies greatly in Europe, from 14 weeks in Germany or Sweden to 52 weeks in the United Kingdom, and only some countries allow maternity leave to be followed by parental leave (International Labour Organization, 2010).

Despite the country's rather favourable maternal leave policy, in France, the prevalence of breastfeeding initiation and duration of breastfeeding remain low as compared with other European countries (Ibanez et al., 2012). In this context, our aim was to describe the association between the initiation or duration of any breastfeeding and several work‐related characteristics among women who worked during pregnancy: the statutory duration of postnatal maternity leave, postponing the return to work until after the statutory period of maternity leave, and maternal working time during the first year post‐partum (and change as compared with the mother's prenatal situation, e.g., from full‐ to part‐time). Because rules for maternity or parental leave differ by parity, we separately analysed data for mothers who gave birth to their first child, second child, or third (or more) child. Understanding how the relationships between work transition pattern and breastfeeding practices vary according to birth order is of great importance in a country with one of the highest fertility rates in Europe. This analysis could also help governments in designing policies and programs to improve breastfeeding practices, taking into consideration that mothers could need varying support depending on their number of children to meet the conflicting demands of employment and motherhood.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study population

The present analysis was based on data from the ELFE (Etude Longitudinale Française depuis l'Enfance) study, a multidisciplinary, nationally representative birth cohort including 18,258 children born in a random sample of 349 maternity units in France in 2011 (Vandentorren et al., 2009). Beginning in April 2011, recruitment for the study took place during 25 selected enrolment days, with four waves of 4 to 8 days spanning each season of the year. Inclusion criteria were children born after 33 weeks' gestation whose mothers were aged 18 years or older and were not planning to move outside metropolitan France in the following 3 years. Participating mothers signed a consent form for themselves and for their child. Fathers signed the consent form for the child's participation when present on inclusion days or were otherwise informed about their right to object.

Mothers were interviewed at the maternity ward to obtain medical information concerning their pregnancy and their newborn, their demographic and socio‐economic characteristics, and their eating habits. Information was completed by using records from obstetric and paediatric medical files. At 2 and 12 months post‐partum, telephone interviews with mothers and fathers included more detailed questions about (a) demographic and socio‐economic variables, such as country of birth, education level, employment, monthly income, and number of family members; (b) health variables concerning both children and their parents, such as parents' asthma and eczema, mother's psychological difficulties, and children's birth weight and height; and (c) feeding practices during the first 2 months. From 3 to 10 months after delivery, families were asked to complete a monthly questionnaire on their infant's diet, either online or in writing (regarding feeding methods and introduction of food and beverages).

The ELFE study was approved by the Advisory Committee for Treatment of Health Research Information (CCTIRS, Comité Consultatif sur le Traitement des Informations pour la Recherche en Santé), the National Data Protection Authority (CNIL, Commission National Informatique et Libertés), and the National Statistics Council (CNIS, Conseil National de l'information statistique).

2.2. Infant feeding

During each follow‐up wave, the infant's feeding method was recorded: solely breast milk, solely infant formula, both breast milk and formula (including plant‐based infant formula), animal milk, or plant‐based beverage. If the mother had stopped breastfeeding, the exact age of the child when breastfeeding ended was obtained, along with the child's age when formula was introduced. Longitudinal follow‐up of the children allowed for ensuring that the feeding methods reported each month were compatible (i.e., the mother could not breastfeed at month X + 1 if she had not breastfed at all during month X). The duration of any breastfeeding (defined as the infant receiving any amount of breast milk) was calculated. If the information needed to calculate duration was only partially available for a certain infant, we attributed to that infant the median breastfeeding duration of infants with the same dietary profile (e.g., still breastfed at month X but receiving only formula at month Y). This situation concerned 15% of infants included in the ELFE cohort but less than 5% of infants considered in the present study. If no information was available concerning breastfeeding, no imputation was performed.

Because of the very short breastfeeding duration in France, breastfeeding was considered as a four‐category variable to limit misunderstanding the findings. The cut‐offs were defined to have both a homogeneous sample size in each category and a meaningful value. For instance, the value of 1 month corresponds to the median duration of predominant breastfeeding among all women; the value of 3 months is close to the end of the legal maternity leave for most women; and the value of 6 months corresponds to the recommended duration for exclusive breastfeeding.

2.3. Maternity leave and return to work

The duration of a given statutory maternity leave period was derived by using the woman's professional status during pregnancy, infant's gestational age, infant birth order (the order in which they were born with respect to their maternal siblings), and prenatal leave duration. Because this variable was not normally distributed, it was considered as a four‐category variable. Self‐employed women were considered in a specific category because their maternity leave was very short (<10 weeks category). Then women who were able to shift 1 to 3 weeks of prenatal maternity leave to postnatal maternity leave (11–12 weeks and 13 weeks categories) were distinguished from those with a postnatal maternity leave of 10 weeks. These categories were similar for women having a first or second child and, for those having at least a third child, a similar reasoning was applied to a legal duration of 18 weeks.

The difference between the legal end of postnatal maternity leave and the mother's return to work was then calculated to identify women who returned to work before the end of the statutory maternity leave and those who postponed their return to work after the statutory maternity leave period; this variable was labelled “Time of return to work.” Because this variable was not normally distributed, it was considered as a five‐category variable. A first category defined as “legal duration ± 6 days” was defined to account for small discrepancies between the date of pregnancy start recorded in the obstetrical record and the date transmitted by women to health authorities to calculate the maternity leave period. Women who returned to work before the legal end of maternity leave were then identified in the category “at least 1 week before legal end.” For women who postponed a return to work, three different categories were considered: “1–2 weeks after legal end,” to identify women using usual holidays rather than parental leave to postpone a return to work; “at least 15 weeks after legal time,” corresponding to the infant's age just below 6 months at maternal return to work for women having a first or second child and allowing to identify women using completely parental leave; and the in‐between category “3–14 weeks after legal time.”

Because maternity leave may be extended by a partially paid parental leave (either not working or working part‐time), we assessed the potential change in maternal working time from pregnancy to 1 year post‐partum (already part‐time in pregnancy; full‐time in pregnancy and part‐time at 1 year; full‐time in pregnancy and not working at 1 year; and full‐time both in pregnancy and at 1 year); this variable was labelled “Maternal working time.” All women who worked part‐time during pregnancy were considered together, whatever their working time when the child turned 1 year old, because most of them (84%) also worked part‐time at this time.

2.4. Infant and parental characteristics

Because more comprehensive family data were collected during the 2‐month interview than the maternity interview and because family sociodemographic characteristics evolved only marginally during these 2 months, we used the data collected at 2 months in our analyses. Sociodemographic characteristics collected during the maternity stay were used only in the case of missing values at 2 months.

Parental sociodemographic characteristics included in the analyses were maternal country of birth (France vs. another country), maternal age at the birth of her first child (18–24, 25–29, 30–34, and ≥35 years), family composition (traditional, stepfamily, one‐parent family), birth order of the ELFE child (first, second, third, fourth, or more), maternal education level (below secondary school, secondary school, high school, 2‐year university degree, 3‐year university degree, and at least 5‐year university degree), parental age difference (younger father, father 0–1 year older, father 2–3 years older, father 4–7 years older, and father at least 8 years older), maternal region of residence, and monthly family income per consumption unit (≤1,500 €, 1,501–2,300 €, 2,301–3,000 €, 3,001–4,000 €, 4,001–5,000 €, and >5,000 €). Paternal presence at delivery (yes/no) was considered an indicator of paternal involvement in pregnancy. Among multiparous women, previous breastfeeding experience of the mother (breastfed all previous children, breastfed some but not all previous children, and breastfed no previous children) was also considered.

Parental health‐related characteristics included reported maternal height and weight before pregnancy, maternal smoking status during pregnancy (never smoked, smoker only before pregnancy, smoker only in early pregnancy, and smoker during the whole pregnancy). Newborn characteristics were collected from medical records: sex, twin birth, birth weight, and gestational age.

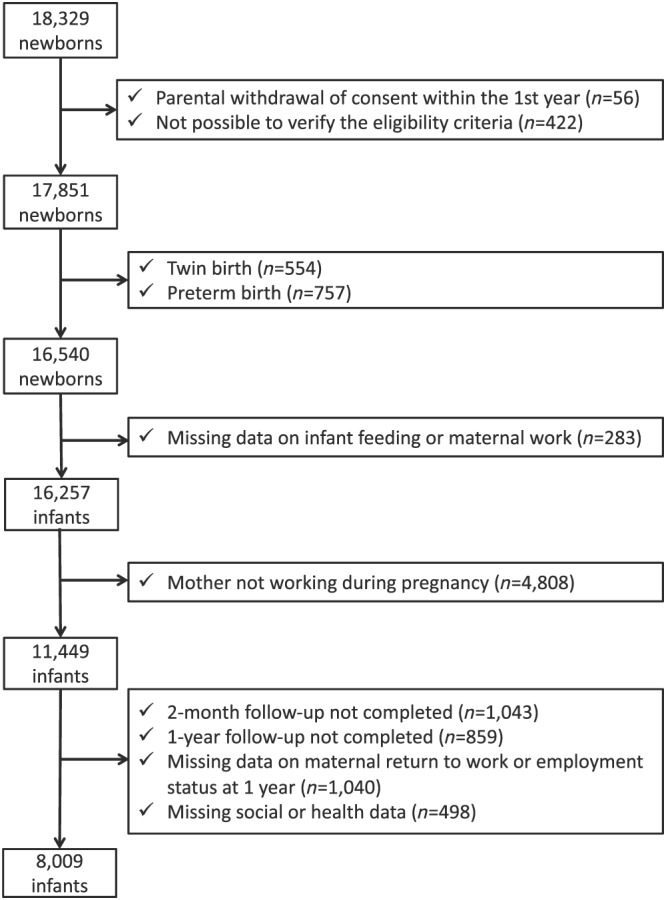

2.5. Sample selection

For the 18,329 infants recruited, 56 parents withdrew consent within the first year. Infants for whom eligibility criteria could not be verified because of missing data were also excluded (n = 422). Therefore, 17,851 infants were eligible. Because they define a specific context for breastfeeding, twin births (n = 554) and preterm births (n = 757) were excluded from our analyses. Also, because we examined the effect of maternity leave on breastfeeding among working women, we excluded women without data on infant feeding or maternal work (n = 283) and women who did not work during pregnancy (n = 4,808), which left a sample of 11,449 mother–child pairs. Finally, we excluded mother–child pairs without any data at the 2‐month or 1‐year follow‐up and those with missing data on employment status at 1 year or on potential confounding factors (see details in Figure 1). Then the complete‐case analysis involved 8,009 mother–child pairs.

Figure 1.

Flow chart

The sample selection is described in Figure 1.

2.6. Statistical analyses

Bivariate analyses involved using chi‐square test or Student t test.

Associations between working characteristics and any breastfeeding initiation (yes vs. no) were tested by multivariate logistic regression. Among breastfeeding women, associations between working characteristics and the duration of any breastfeeding (<1 month, 1 to <3 months, 3 to <6 months, 6 to <9 months, and at least 9 months) were tested by multivariate multinomial logistic regression. Because the duration of any breastfeeding was an ordered outcome, ordinal logistic regression was first considered. However, the proportional‐odds assumption was not verified (P < .0001 for all analyses), so we used a less restrictive model, multinomial logistic regression. All models were adjusted for infant characteristics (sex and birth weight), maternal characteristics (age at first child's birth, country of birth, education level, pre‐pregnancy body mass index, and smoking status), paternal characteristics (age difference with mother and presence at delivery), household income, or characteristics related to study design (maternal region of residence, size of maternity unit, and recruitment wave). Among multiparous women, models were also adjusted for previous breastfeeding experience.

Given that the duration of maternity leave and the possibility to postpone a return to work or modify the working time depending on the child's birth order, all analyses were stratified by the child's birth order. For women giving birth to their first child, models were not adjusted on maternal previous breastfeeding experience.

To assess the potential impact of missing measurements on confounding variables, we performed multiple imputations as a sensitivity analysis with the SAS software. We assumed that data were missing at random and generated five independent datasets by using the fully conditional specification method (MI procedure, FCS statement, NIMPUTE option, Yuan 2000) and then calculated pooled effect estimates (MIANALYSE procedure). These sensitivity analyses involved data for all women who worked during pregnancy (n = 11,435).

All analyses involved using SAS v9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC).

2.7. Availability of data and materials

The data underlying the findings cannot be made freely available because of ethical and legal restrictions. This is because the present study includes an important number of variables that, together, could be used to re‐identify the participants based on a few key characteristics and then be used to have access to other personal data. Therefore, the French ethical authority strictly forbids making such data freely available. However, they can be obtained upon request from the ELFE principal investigator. Readers may contact marie-aline.charles@inserm.fr to request the data.

2.8. Ethics approval and consent to participate

Participating mothers signed a consent form for themselves and for their child. Fathers signed the consent form for the child's participation when present on inclusion days, or were otherwise informed about their right to object. The ELFE study was approved by the Advisory Committee for Treatment of Health Research Information (CCTIRS, Comité Consultatif sur le Traitement des Informations pour la Recherche en Santé), the National Data Protection Authority (CNIL, Commission National Informatique et Libertés), and the National Statistics Council (CNIS).

3. RESULTS

The comparison of women who worked during pregnancy to other women included in the ELFE study is presented in Table S1. Among women who worked during pregnancy, some were excluded from the analyses because of missing data, and these women were compared with the women included in the analyses in Table S1 as well. Women excluded due to missing data were younger than women included in the present analyses, had a lower education level, and were more likely to be born in a country other than France and to be obese.

The sample characteristics and breastfeeding duration are described by infant birth order in Table 1. Bivariate analyses between working characteristics and any breastfeeding are detailed in Table S2.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics according to child birth order (n = 8,009)

| Variable | First child | Second child | Third child or more |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 3,677) | (n = 3,100) | (n = 1,232) | |

| Child's characteristics | |||

| Boys | 50.9% (1,869) | 52.0% (1,610) | 51.4% (632) |

| Birth weight (g) | 3,309 (423) | 3,433 (439) | 3,437 (463) |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 39.5 (1.1) | 39.5 (1.1) | 39.3 (1.2) |

| Family characteristics | |||

| Type of family | |||

| Traditional | 96.1% (3,534) | 93.1% (2,887) | 79.9% (984) |

| Single parenthood | 1.3% (49) | 0.6% (20) | 1.5% (18) |

| Step family | 2.6% (94) | 6.2% (193) | 18.7% (230) |

| Maternal age at first child (years) | 29.3 (4.2) | 28.3 (3.8) | 26.1 (3.8) |

| <25 | 10.6% (388) | 14.3% (444) | 32.4% (399) |

| 25–29 | 44.7% (1,644) | 50.5% (1,565) | 50.4% (621) |

| 30–34 | 33.2% (1,222) | 29.3% (909) | 15.4% (190) |

| 35 or more | 11.5% (423) | 5.9% (182) | 1.8% (22) |

| Mother born abroad | 5.7% (210) | 5.8% (180) | 8.8% (109) |

| Difference between parental ages | |||

| Younger father | 19.5% (718) | 18.4% (570) | 20.1% (248) |

| Same age | 14.4% (529) | 14.0% (435) | 12.8% (158) |

| Father 1–2 years older | 27.8% (1,024) | 27.1% (841) | 25.4% (313) |

| Father 3–4 years older | 23.0% (847) | 24.9% (772) | 23.0% (283) |

| Father at least 5 years older | 15.2% (559) | 15.5% (482) | 18.7% (230) |

| Paternal presence at delivery | 89.3% (3,285) | 88.6% (2,747) | 86.3% (1,063) |

| Family income per consumption unit (€) | 1,980 (968) | 1,889 (2,036) | 1,654 (1,222) |

| Maternal education level | |||

| Below secondary school | 2.0% (74) | 2.2% (69) | 5.2% (64) |

| Secondary school | 7.8% (288) | 7.9% (246) | 12.7% (156) |

| High school | 15.1% (557) | 15.4% (478) | 17.4% (214) |

| 2‐year university degree | 26.4% (970) | 26.6% (826) | 24.5% (302) |

| 3‐year university degree | 22.0% (809) | 23.2% (719) | 19.6% (241) |

| At least 5‐year university degree | 26.6% (979) | 24.6% (762) | 20.7% (255) |

| Maternal body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.9 (4.3) | 23.2 (4.4) | 23.6 (4.4) |

| Maternal smoking | |||

| Never smoker | 57.2% (2,102) | 59.2% (1,834) | 61.8% (761) |

| Smoker only before pregnancy | 27.2% (999) | 25.7% (797) | 22.7% (280) |

| Smoker only in early pregnancy | 4.4% (163) | 3.3% (101) | 2.2% (27) |

| Smoker throughout pregnancy | 11.2% (413) | 11.9% (368) | 13.3% (164) |

| Previous breastfeeding experience | |||

| None | 26.4% (818) | 23.5% (290) | |

| Yes, all children | 73.6% (2,282) | 64.9% (800) | |

| Yes, but not all | 11.5% (142) | ||

| Any breastfeeding duration | |||

| Never | 25.2% (927) | 25.7% (796) | 24.6% (303) |

| <1 month | 19.0% (699) | 15.2% (471) | 12.3% (151) |

| 1 to <3 months | 17.9% (660) | 16.3% (504) | 11.5% (142) |

| 3 to <6 months | 19.9% (733) | 20.5% (636) | 19.0% (234) |

| 6 to <9 months | 9.6% (354) | 11.0% (342) | 16.2% (200) |

| At least 9 months | 8.3% (304) | 11.3% (351) | 16.4% (202) |

| Maternal type of employment | |||

| Socioprofessional category | |||

| Farmer, trader, artisan | 3.5% (130) | 3.5% (110) | 3.2% (40) |

| Manager | 23.8% (874) | 23.6% (733) | 19.5% (240) |

| Intermediate profession | 29.2% (1,074) | 30.3% (938) | 30.0% (369) |

| Employee | 42.4% (1,560) | 41.4% (1,282) | 45.0% (554) |

| Worker | 1.1% (39) | 1.2% (37) | 2.4% (29) |

| Type of contract | |||

| Non‐permanent position | 7.7% (265) | 4.8% (139) | 6.9% (79) |

| Permanent position | 92.3% (3,185) | 95.2% (2,779) | 93.1% (1,074) |

| Maternal return to work | |||

| Infant age at maternal return to work | |||

| <10 weeks | 22.2% (815) | 19.1% (592) | 3.7% (45) |

| 10–13 weeks | 45.9% (1,689) | 41.0% (1,271) | 4.8% (59) |

| 14 weeks to <6 months | 16.9% (620) | 17.1% (529) | 63.1% (777) |

| ≥6 months | 15.0% (553) | 22.8% (708) | 28.5% (351) |

| Infant age at the end of legal maternity leavea | |||

| <10 weeks | 3.7% (135) | 3.2% (99) | 4.4% (54) |

| 10 weeks | 40.4% (1,487) | 39.2% (1,214) | 37.6% (463) |

| 11–12 weeks | 39.9% (1,466) | 43.3% (1,343) | 26.7% (329) |

| ≥13 weeks | 16.0% (589) | 14.3% (444) | 31.3% (386) |

| Time of return to work | |||

| At least 1 week before legal end | 29.3% (1,076) | 26.0% (806) | 36.7% (452) |

| Legal duration ±6 days | 10.9% (401) | 9.0% (278) | 14.9% (183) |

| 1–2 weeks after legal time | 22.5% (826) | 19.9% (618) | 10.1% (125) |

| 3–14 weeks after legal time | 22.9% (841) | 23.6% (731) | 15.0% (185) |

| At least 15 weeks after legal time | 14.5% (533) | 21.5% (667) | 23.3% (287) |

| Maternal working time | |||

| Part‐time in pregnancy | 11.6% (428) | 23.0% (714) | 36.3% (447) |

| Full‐time in pregnancy and not working at 1 year | 7.4% (271) | 15.8% (489) | 19.2% (236) |

| Full‐time in pregnancy and part‐time | 11.7% (430) | 25.4% (786) | 18.3% (226) |

| Full‐time in pregnancy and at 1 year | 69.3% (2,548) | 35.8% (1,111) | 26.2% (323) |

In the third‐child sample, thresholds were <18, 18, 19, and at least 20 weeks because the fully paid postnatal maternity leave is 18 weeks in this group.

In the whole sample (n = 8,009), older infant age at maternal return to work was related to greater likelihood to initiate breastfeeding and longer breastfeeding duration among breastfeeding mothers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate associations between infant's age at maternal return to work and breastfeeding initiation or duration (n = 8,009)

| Variable | Initiation | Duration among breastfeeding women (ref: 3 to <6 months) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 month | 1 to <3 months | 6 to <9 months | ≥ 9 months | ||

| Infant age at maternal return to work | |||||

| <10 weeks | 0.84 [0.71–0.98] | 1.49 [1.20–1.86] | 1.28 [1.03–1.59] | 1.22 [0.92–1.61] | 1.48 [1.10–1.98] |

| 10–13 weeks | 1 [ref] | 1 [ref] | 1 [ref] | 1 [ref] | 1 [ref] |

| 14 weeks to <6 months | 1.52 [1.26–1.82] | 0.70 [0.56–0.87] | 0.49 [0.39–0.61] | 1.16 [0.92–1.46] | 1.32 [1.02–1.70] |

| ≥6 months | 1.85 [1.54–2.22] | 0.87 [0.69–1.08] | 0.59 [0.47–0.74] | 2.03 [1.61–2.57] | 3.49 [2.75–4.44] |

Note. Values are multivariable odds ratios (95% confidence intervals), also adjusted for infant characteristics (sex, birth weight, and birth order), maternal characteristics (age at first child's birth, parity, country of birth, education level, pre‐pregnancy BMI, and smoking status), paternal characteristics (age difference with mother and presence at delivery), family type (traditional, step‐family, and single parenthood), family income, previous maternal breastfeeding experience, or study design‐related characteristics (maternal region of residence, size of maternity unit, and recruitment wave).

3.1. Breastfeeding initiation

Among women with a first or second child, the legal duration of maternity leave was not related to breastfeeding initiation (Table 3). Among women with a third child or more, the legal duration of maternity leave was related to breastfeeding initiation but not with a linear trend. Among women with a first child, those who postponed their return to work until at least 3 weeks after the legal period were more likely to initiate breastfeeding. Reduction of working time in the first year post‐partum was also positively associated with breastfeeding initiation.

Table 3.

Association between work‐related variables, considered simultaneously, and initiation of any breastfeeding according to child birth order (n = 8,009)

| Work‐related variables |

First child (n = 3,677) |

Second child (n = 3,100) |

Third child or more (n = 1,232) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant age at the end of legal maternity leavea | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.02 | |||

| <10 weeks | 0.79 [0.50–1.23] | 0.89 [0.45–1.80] | 0.27 [0.10–0.70] | |||

| 10 weeks | 1 [ref] | 1 [ref] | 1 [ref] | |||

| 11–12 weeks | 0.84 [0.70–1.00] | 0.98 [0.76–1.25] | 0.59 [0.34–1.00] | |||

| ≥13 weeks | 0.99 [0.76–1.27] | 0.98 [0.68–1.42] | 0.84 [0.51–1.38] | |||

| Time of return to work | <0.0001 | 0.09 | 0.03 | |||

| At least 1 week before legal end | 0.98 [0.75–1.29] | 1.02 [0.67–1.56] | 0.75 [0.41–1.36] | |||

| Legal duration ±6 days | 1 [ref] | 1 [ref] | 1 [ref] | |||

| 1–2 weeks after legal time | 1.07 [0.80–1.43] | 1.09 [0.69–1.72] | 1.71 [0.73–4.02] | |||

| 3–14 weeks after legal time | 1.76 [1.30–2.38] | 1.42 [0.91–2.22] | 1.02 [0.49–2.14] | |||

| At least 15 weeks after legal time | 2.16 [1.53–3.04] | 1.49 [0.94–2.37] | 1.67 [0.86–3.25] | |||

| Maternal working time | 0.0006 | 0.05 | 0.8 | |||

| Part‐time in pregnancy | 1.22 [0.94–1.59] | 1.40 [1.02–1.90] | 1.26 [0.76–2.09] | |||

| Full‐time in pregnancy and not working at 1 year | 1.20 [0.87–1.65] | 1.58 [1.10–2.27] | 1.04 [0.58–1.87] | |||

| Full‐time in pregnancy and part‐time | 1.77 [1.34–2.35] | 1.19 [0.89–1.58] | 1.07 [0.59–1.96] | |||

| Full‐time in pregnancy and at 1 year | 1 [ref] | 1 [ref] | 1 [ref] | |||

Note. Values are multivariable odds ratios (95% confidence intervals), also adjusted for infant characteristics (sex and birth weight), maternal characteristics (age at first child's birth, country of birth, education level, pre‐pregnancy BMI, and smoking status), paternal characteristics (age difference with mother and presence at delivery), family type (traditional, step‐family, and single parenthood), family income, or study design‐related characteristics (maternal region of residence, size of maternity unit, and recruitment wave). In the second‐child and third‐child samples, models were also adjusted on previous maternal breastfeeding experience.

In the third‐child sample, thresholds were < 18, 18, 19, and at least 20 weeks.

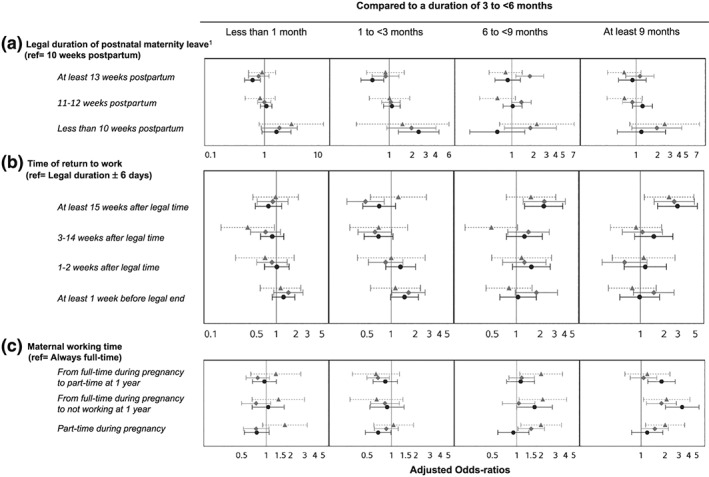

3.2. Breastfeeding duration

Among women with a first child, a longer legal duration of postnatal maternity leave (at least 13 weeks) was associated with reduced likelihood of short breastfeeding duration (<3 months), as compared with an intermediate duration (3 to <6 months; Figure 2 and details in Table S3); a short duration of postnatal maternity leave (<10 weeks) was related to greater likelihood of short breastfeeding duration (1 to <3 months) as compared with an intermediate duration (3s to <6 months). Mothers who postponed their return to work until at least 15 weeks after the legal period were more likely to breastfeed for at least 6 months as compared with an intermediate duration (3 to <6 months). Women who worked part‐time during pregnancy were less likely to breastfeed for a short duration (1 to <3 months), and a decrease in working time in the first year post‐partum was related to greater likelihood of breastfeeding for at least 9 months as compared with an intermediate duration (3 to <6 months).

Figure 2.

Association between work‐related variables and duration of any breastfeeding among breastfeeding mothers (n = 5,983). 1In the third‐child sample, thresholds were <18, 18, 19, and at least 20 weeks. Values are multivariable odds ratios, also adjusted for infant characteristics (sex and birth weight), maternal characteristics (age at first child's birth, country of birth, education level, pre‐pregnancy body mass index, and smoking status), paternal characteristics (age difference with mother and presence at delivery), family income, family type (traditional, step‐family, and single parenthood), or study design‐related characteristics (maternal region of residence, size of maternity unit, and recruitment wave). In the second‐ and third‐child samples, models were also adjusted on previous maternal breastfeeding experience. Black circle/solid line: first child; grey diamond/solid line: second child; grey triangle/dashed line: third child or more

Among women with a second child, the duration of postnatal maternity leave was not clearly related to breastfeeding duration. Postponing the maternal return to work until at least 15 weeks was associated with longer breastfeeding duration, whereas a return to work before the end of the legal period was related to greater likelihood of breastfeeding for a short duration (1 to <3 months) as compared with an intermediate duration (3 to <6 months). Women who worked part‐time during pregnancy or who did not return to work within the first year were more likely to breastfeed for at least 9 months as compared with an intermediate duration (3 to <6 months) than were those who worked full‐time in pregnancy and at 1 year post‐partum.

Among women with a third child or more (with longer legal maternity leave), postponing a return to work until at least 15 weeks after the legal period was positively related to longer breastfeeding duration (at least 9 months) as compared with an intermediate duration (3 to <6 months). Not working full‐time at 1 year post‐partum was related to longer breastfeeding duration.

3.3. Sensitivity analyses

In analyses based on multiple imputations of missing data, for women giving birth to their first child, we found similar positive associations between legal duration of postnatal maternity leave, time of a return to work and working time, and initiation or duration of breastfeeding (Table S4) as well as a higher likelihood to breastfeed for a short duration among women with a return to work before the legal time. For women having a second child, we found no association with breastfeeding initiation; the association between time of return to work and breastfeeding duration remained similar, but the association between maternal working time and breastfeeding duration was less consistent. Finally, for women having a third child, we found a positive link only between a mother delaying her return to work until at least 15 weeks after the legal period and breastfeeding initiation or duration.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Main findings

Among primiparous women, both postponing a return to work for at least 3 weeks after legal postnatal maternity leave and not working full‐time at 1 year post‐partum were related to higher prevalence of breastfeeding initiation. Among women giving birth to their first or second child (with a legal postnatal maternity leave of about 10 weeks), those with a return to work before the legal period were more likely to breastfeed for a shorter duration, whereas those who delayed a return to work until at least 15 weeks were more likely to breastfeed for a longer duration. Working part‐time also related positively to breastfeeding duration, especially among primiparous women. Among women giving birth to their third child or more (with a legal postnatal maternity leave of about 18 weeks), working characteristics were less related to breastfeeding duration, except working time.

4.2. Maternal return to work

In the ELFE study, women who postponed their return to work until at least 15 weeks after the end of legal maternity leave were more likely to initiate breastfeeding. Likewise, in the ALSPAC study in the United Kingdom, the timing of a mother's return to work seemed of great importance, with higher breastfeeding initiation prevalence among those who did not return before 6 weeks post‐partum (Noble, 2001); in the U.S. National Survey of Family Growth, paid maternity leave for at least 12 weeks was associated with greater breastfeeding initiation (Mirkovic, Perrine, & Scanlon, 2016); in the U.K. Millennium Cohort Study (Hawkins et al., 2007b), employed mothers who returned to work within the first 4 months post‐partum were less likely to initiate breastfeeding.

Also, in the ELFE study, women who postponed their return to work by at least 15 weeks after the end of legal maternity leave were more likely to breastfeed for a long duration. Similarly, returning to work earlier has been associated with shorter breastfeeding duration in previous studies (Bonet et al., 2013; Hawkins et al., 2007a; Mandal et al., 2010; Robert, Coppieters, Swennen, & Dramaix, 2014; Skafida, 2012). Some studies specifically investigated the effect of paid maternity leave on breastfeeding duration. In the U.S. National Survey of Family Growth, paid maternity leave for at least 12 weeks was associated with greater breastfeeding prevalence at 6 months post‐partum (Mirkovic et al., 2016). In Canada, the length of paid maternity leave was extended from 6 months to 1 year in 2001. Studies were conducted to assess the effect of this policy on breastfeeding: the increase in length of maternity leave was followed by increase in breastfeeding duration by more than 1 month (Baker & Milligan, 2008).

The negative association between maternal employment and breastfeeding duration could be due to the difficulty in managing both breastfeeding and employment commitments. French law states that breastfeeding mothers are allowed to use 1 hr of their working time to pump milk or to breastfeed their child (Gouvernement français, in force in 2011b). Because few workplaces actually provide in situ child care arrangements or lactation rooms for pumping breast milk, this limited amount of time allotted for breastfeeding during working hours could be insufficient to allow mothers to maintain an adequate level of lactation or comfortable working conditions. Previous studies underlined the importance of workplace accommodations to support breastfeeding after the mother's return to work (Kozhimannil, Jou, Gjerdingen, & McGovern, 2016).

4.3. Working time

In France, a decrease in working time is promoted during parental leave, because reduced wages are partially compensated by financial social assistance. We found that a decrease in working time during the first year post‐partum was associated with longer breastfeeding duration. In line with these results, several studies underlined that working part‐time was related to greater breastfeeding initiation (Mandal et al., 2010) and later breastfeeding cessation (Hawkins et al., 2007b; Skafida, 2012; Xiang, Zadoroznyj, Tomaszewski, & Martin, 2016). We hypothesized that some women may prepare for parenthood by planning to reduce their working time and as a consequence are in better conditions for breastfeeding, but others may wish to breastfeed and consequently decide to adjust their working time for this purpose. Moreover, managing both breastfeeding and occupational constraints could be easier with part‐time work. However, we did not collect relevant data to test these hypotheses.

4.4. Discrepancies according to birth order

As noted previously, in France, the statutory duration of postnatal maternity leave is shorter for primiparous women or those with a second child than women with three children or more. Among women with a first or second child, postponing a return to work by at least 15 weeks after the legal period was related to greater prevalence of long breastfeeding duration (at least 6 months). To a lesser extent, extending this legal duration from 10 weeks to at least 13 weeks (by postponing the beginning of prenatal leave) was also positively related to breastfeeding duration. Among women with a third child (therefore a longer legal duration of postnatal maternity leave), the most important factor related to breastfeeding duration was the decrease in working time allowed by the parental leave; however, this was not related to breastfeeding initiation. For women with a third child, previous breastfeeding experience may be the major determinant of breastfeeding initiation or the intention to breastfeed (Moimaz, Rocha, Garbin, Rovida, & Saliba, 2017), and thus factors related to breastfeeding duration may encompass breastfeeding facilities and support. Unfortunately, in our analyses, we could not distinguish whether women who are more inclined to breastfeed used these facilities to favour breastfeeding success or whether the facilities encouraged women to initiate and extend the duration of their breastfeeding.

4.5. Strengths and limitations

We must acknowledge the inability to study exclusive breastfeeding according to the WHO definition with the ELFE study data, given that information on the use of water, water‐based drinks, and fruit juice during the period from 0 to 2 months was not collected in the ELFE study. The ELFE study provides a unique opportunity to report data concerning a large sample of births in metropolitan France. Data were collected each month from 2 to 12 months to reduce the risk of memory bias regarding infant diet. Our sensitivity analyses, based on multiple imputations of missing data, provided consistent findings except for those on maternal working time among women giving birth to their third child or more. The large data collection within the ELFE study allows us to account for the main risk factors in our analyses. We attempted to distinguish between the different aspects of public policies surrounding a child's birth and their potential influence on breastfeeding. Unfortunately, we did not have data concerning women's breastfeeding facilities or places for breast milk pumping at work and were thus unable to assess the impact of these policies on breastfeeding duration among women returning to work in the early post‐partum period. Moreover, because of their strong association with our variables of interest, we were not able to consider other characteristics of maternal employment, such as socio‐professional category or type of contract.

5. CONCLUSION

From a large national cohort study, we highlighted the positive association between the duration of legal maternity leave and duration of any breastfeeding. We also established that extending a mother's return to work beyond the legal maternity leave period, regardless of the infant's birth order, or decreasing a mother's working time in the first year post‐partum for women with three children or more were related to greater prevalence of breastfeeding initiation and longer breastfeeding duration. These results support extending maternity leave or promoting different working time arrangements to encourage a longer period of breastfeeding.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

BL‐G and XT conceptualized and designed the study, conducted the statistical analyses, interpreted the results, and drafted the initial manuscript. CK, SW, EK, and HV contributed to the statistical analyses and the interpretation of the results and critically reviewed the manuscript. MB, SN, SL, and CD‐P contributed to the interpretation of the results and critically reviewed the manuscript. CB and M‐ND designed the data collection instruments, supervised data collection and data management, and critically reviewed the manuscript. MAC conceptualized and designed the study, contributed to the interpretation of the results, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supporting information

Table S1. Comparison between included and excluded women

Table S2. Bivariate analyses between work‐related characteristics and any breastfeeding duration (n = 8,009)

Table S3. Multivariate association between work‐related characteristics and breastfeeding duration, among breastfeeding women (n = 5,983)

Table S4. Sensitivity analysis (multiple imputations) for multivariate analysis between work‐related characteristics and breastfeeding initiation or duration (n = 11,435)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the scientific coordinators (M.A. Charles, B. Geay, H. Léridon, C. Bois, M.‐N. Dufourg, J.L. Lanoé, X. Thierry, and C. Zaros), IT and data managers, statisticians (A. Rakotonirina, R. Kugel, R. Borges‐Panhino, M. Cheminat, and H. Juillard), administrative and family communication staff, and study technicians (C. Guevel, M. Zoubiri, L.G.L. Gravier, I. Milan, and R. Popa) of the ELFE coordination team as well as the families that gave their time for the study. This analysis was funded by an ANR grant within the framework “Social determinants of health” (grant number: ANR‐12‐DSSA‐0001).The Elfe survey is a joint project between the French Institute for Demographic Studies (INED) and the National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM), in partnership with the French blood transfusion service (Etablissement francais du sang, EFS), Sante publique France, the National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE), the Direction generale de la sante (DGS, part of the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs), the Direction generale de la prevention des risques (DGPR, Ministry for the Environment), the Direction de la recherche, des etudes, de l'evaluation et des statistiques (DREES, Ministry of Health and Social Affairs), the Departement des etudes, de la prospective et des statistiques (DEPS, Ministry of Culture), and the Caisse nationale des allocations familiales (CNAF), with the support of the Ministry of Higher Education and Research and the Institut national de la jeunesse et de l'education populaire (INJEP). Via the RECONAI platform, it receives a government grant managed by the National Research Agency (ANR) under the “Investissements d'avenir” programme (ANR‐11‐EQPX‐0038).

de Lauzon‐Guillain B, Thierry X, Bois C, et al. Maternity or parental leave and breastfeeding duration: Results from the ELFE cohort. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15:e12872 10.1111/mcn.12872

REFERENCES

- Agostoni, C. , Braegger, C. , Decsi, T. , Kolacek, S. , Koletzko, B. , Michaelsen, K. F. , … ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition (2009). Breast‐feeding: A commentary by the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 49, 112–125. 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31819f1e05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, D. L. , Fong, D. Y. , & Tarrant, M. (2015). Factors associated with breastfeeding duration and exclusivity in mothers returning to paid employment postpartum. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19, 990–999. 10.1007/s10995-014-1596-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M. , & Milligan, K. (2008). Maternal employment, breastfeeding, and health: Evidence from maternity leave mandates. Journal of Health Economics, 27, 871–887. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowska‐Rataj, A. , & Matysiak, A. (2016). The causal effects of the number of children on female employment—Do European institutional and gender conditions matter? Journal of Labor Research, 37, 343–367. 10.1007/s12122-016-9231-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonet, M. , Marchand, L. , Kaminski, M. , Fohran, A. , Betoko, A. , Charles, M. A. , … EDEN Mother–Child Cohort Study Group (2013). Breastfeeding duration, social and occupational characteristics of mothers in the French ‘EDEN mother‐child’ cohort. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17, 714–722. 10.1007/s10995-012-1053-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018). CDC releases 2018 Breastfeeding Report Card. August 20, 2018 edn.

- Chuang, C. H. , Chang, P. J. , Chen, Y. C. , Hsieh, W. S. , Hurng, B. S. , Lin, S. J. , & Chen, P. C. (2010). Maternal return to work and breastfeeding: A population‐based cohort study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47, 461–474. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein, S. B. , & Roe, B. (1998). The effect of work status on initiation and duration of breast‐feeding. American Journal of Public Health, 88, 1042–1046. 10.2105/AJPH.88.7.1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gielen, A. C. , Faden, R. R. , O'Campo, P. , Brown, C. H. , & Paige, D. M. (1991). Maternal employment during the early postpartum period: Effects on initiation and continuation of breast‐feeding. Pediatrics, 87, 298–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouvernement français (in force in 2011a). [Code du travail ‐ Chapitre V: Maternité, paternité, adoption et éducation des enfants ‐ Section 1: Protection de la grossesse et de la maternité ‐ Sous‐section 3: Autorisations d'absence et congé de maternité ‐ articles L1225–16 à L1225–28]. Legifrance.

- Gouvernement français (in force in 2011b). [Code du travail ‐ Chapitre V: Maternité, paternité, adoption et éducation des enfants ‐ Section 1: Protection de la grossesse et de la maternité ‐ Sous‐section 5: Dispositions particulières à l'allaitement ‐ articles L1225–30 à L1225–33]. Legifrance.

- Gouvernement français (in force in 2011c). [Code du travail ‐ Chapitre V: Maternité, paternité, adoption et éducation des enfants ‐ Section 4: Congés d'éducation des enfants ‐ Sous‐section 1: Congé parental d'éducation et passage à temps partiel ‐ articles L1225–47 à L1225–60]. Legifrance.

- Hawkins, S. S. , Griffiths, L. J. , Dezateux, C. , & Law, C. (2007a). The impact of maternal employment on breast‐feeding duration in the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Public Health Nutrition, 10, 891–896. 10.1017/S1368980007226096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, S. S. , Griffiths, L. J. , Dezateux, C. , & Law, C. (2007b). Maternal employment and breast‐feeding initiation: Findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 21, 242–247. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00812.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez, G. , Martin, N. , Denantes, M. , Saurel‐Cubizolles, M. J. , Ringa, V. , & Magnier, A. M. (2012). Prevalence of breastfeeding in industrialized countries. Revue d'Épidémiologie et de Santé Publique, 60, 305–320. 10.1016/j.respe.2012.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization (2010). Maternity at work: A review of national legislation. Geneva: Second edition edn. International Labour Office ‐ Conditions of Work and Employment Branch. [Google Scholar]

- Kersuzan, C. , Gojard, S. , Tichit, C. , Thierry, X. , Wagner, S. , Nicklaus, S. , … de Lauzon‐Guillain, B. (2014). Prévalence de l'allaitement à la maternité selon les caractéristiques des parents et les conditions de l'accouchement. Résultats de l'enquête Elfe Maternité, France métropolitaine, 2011. Bulletin Epidémiologique Hebdomadaire, 27, 440–449. [Google Scholar]

- Kozhimannil, K. B. , Jou, J. , Gjerdingen, D. K. , & McGovern, P. M. (2016). Access to workplace accommodations to support breastfeeding after passage of the Affordable Care Act. Womens Health Issues, 26, 6–13. 10.1016/j.whi.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurinij, N. , Shiono, P. H. , Ezrine, S. F. , & Rhoads, G. G. (1989). Does maternal employment affect breast‐feeding? American Journal of Public Health, 79, 1247–1250. 10.2105/AJPH.79.9.1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan, C. , Zittel, T. , Striebel, S. , Reister, F. , Brenner, H. , Rothenbacher, D. , & Genuneit, J. (2016). Changing societal and lifestyle factors and breastfeeding patterns over time. Pediatrics, 137, e20154473 10.1542/peds.2015-4473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, B. , Roe, B. E. , & Fein, S. B. (2010). The differential effects of full‐time and part‐time work status on breastfeeding. Health Policy, 97, 79–86. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangrio, E. , Persson, K. , & Bramhagen, A. C. (2017). Sociodemographic, physical, mental and social factors in the cessation of breastfeeding before 6 months: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 32, 451–465. 10.1111/scs.12489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew F., Thompson J., Fellows L., Large A., Speed M. & Renfrew M.J. (2012). Infant Feeding Survey 2010.

- Mirkovic, K. R. , Perrine, C. G. , & Scanlon, K. S. (2016). Paid maternity leave and breastfeeding outcomes. Birth, 43, 233–239. 10.1111/birt.12230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moimaz, S. A. S. , Rocha, N. B. , Garbin, C. A. S. , Rovida, T. A. , & Saliba, N. A. (2017). Factors affecting intention to breastfeed of a group of Brazilian childbearing women. Women and Birth, 30, e119–e124. 10.1016/j.wombi.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble, S. (2001). Maternal employment and the initiation of breastfeeding. Acta Paediatrica, 90, 423–428. 10.1080/08035250121419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pénet, S. (2006). Le congé de maternité In Etudes et Resultats. Direction de la Recherche des Etudes et l'évaluation et des statistiques (vol. 531). Paris: Direction de la Recherche des Etudeset l'évaluation et des statistiques. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, E. , Coppieters, Y. , Swennen, B. , & Dramaix, M. (2014). Breastfeeding duration: A survival analysis‐data from a regional immunization survey. BioMed Research International, 2014, 529790–8. 10.1155/2014/529790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossen, L. M. , Simon, A. E. , & Herrick, K. A. (2015). Types of infant formulas consumed in the United States. Clinical Pediatrics, 55, 278–285. 10.1177/0009922815591881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salanave, B. , de Launay, C. , Guerrisi, C. , & Castetbon, K. (2012). Breastfeeding rates in maternity units and at 1 month. Results from the EPIFANE survey, France, 2012. Bulletin Epidémiologique Hebdomadaire, 2012, 383–387. [Google Scholar]

- Section on Breastfeeding (2012). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 129, e827–e841. 10.1542/peds.2011-3552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skafida, V. (2012). Juggling work and motherhood: The impact of employment and maternity leave on breastfeeding duration: A survival analysis on Growing Up in Scotland data. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16, 519–527. 10.1007/s10995-011-0743-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandentorren, S. , Bois, C. , Pirus, C. , Sarter, H. , Salines, G. , Leridon, H. , & Elfe team (2009). Rationales, design and recruitment for the ELFE longitudinal study. BMC Pediatrics, 9, 58 10.1186/1471-2431-9-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visness, C. M. , & Kennedy, K. I. (1997). Maternal employment and breast‐feeding: Findings from the 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey. American Journal of Public Health, 87, 945–950. 10.2105/AJPH.87.6.945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, S. , Kersuzan, C. , Gojard, S. , Tichit, C. , Nicklaus, S. , Geay, B. , … de Lauzon‐Guillain, B. (2015). Breastfeeding duration in France according to parents and birth characteristics. Results from the ELFE longitudinal French Study, 2011. Bulletin Epidémiologique Hebdomadaire, 29, 522–532. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, S. , Kersuzan, C. , Gojard, S. , Tichit, C. , Nicklaus, S. , Thierry, X. , … de Lauzon‐Guillain, B. (2019). Breastfeeding initiation and duration in France: The importance of intergenerational and previous maternal breastfeeding experiences—Results from the nationwide ELFE study. Midwifery, 69, 67–75. 10.1016/j.midw.2018.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, M. , Saurel‐Cubizolles, M.‐J. , & the EDEN mother‐child cohort study group (2013). Returning to work one year after childbirth: Data from the mother–child cohort EDEN. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17, 1432–1440. 10.1007/s10995-012-1147-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2002). Infant and young child nutrition—Global strategy on infant and young child feeding. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, N. , Zadoroznyj, M. , Tomaszewski, W. , & Martin, B. (2016). Timing of Return to Work and Breastfeeding in Australia. Pediatrics, 137, e20153883 10.1542/peds.2015-3883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Comparison between included and excluded women

Table S2. Bivariate analyses between work‐related characteristics and any breastfeeding duration (n = 8,009)

Table S3. Multivariate association between work‐related characteristics and breastfeeding duration, among breastfeeding women (n = 5,983)

Table S4. Sensitivity analysis (multiple imputations) for multivariate analysis between work‐related characteristics and breastfeeding initiation or duration (n = 11,435)

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying the findings cannot be made freely available because of ethical and legal restrictions. This is because the present study includes an important number of variables that, together, could be used to re‐identify the participants based on a few key characteristics and then be used to have access to other personal data. Therefore, the French ethical authority strictly forbids making such data freely available. However, they can be obtained upon request from the ELFE principal investigator. Readers may contact marie-aline.charles@inserm.fr to request the data.