Abstract

Lower back pain is one of the main contributors to morbidity and chronic disability in the United States. Despite the significance of the problem, it is still not well understood. There is a clear need for objective, non-invasive biomarkers to localize specific pain generators and identify early stage changes to enable reliable diagnosis and treatment. In this study we focus on intervertebral disc degeneration as a source of lower back pain. Quantitative imaging markers T1ρ and T2 have been shown to be promising techniques for in vivo diagnosis of biochemical degeneration in discs due to their sensitivity to macromolecular changes in proteoglycan content and collagen integrity. We describe a semi-automated technique for quantifying T1ρ and T2 relaxation time maps in the nucleus pulposus (NP) and the annulus fibrosus (AF) of the lumbar intervertebral discs. Compositional changes within the NP and AF associated with degeneration occur much earlier than the visually observable structural changes. The proposed technique rigorously quantifies these biochemical changes taking into account subtle regional variations to allow interpretation of early degenerative changes that are difficult to interpret with traditional MRI techniques and clinical subjective grading scores. T1ρ and T2 relaxation times in the NP decrease with degenerative severity in the disc. Moreover, standard deviation and texture measurements of these values show sharper and more significant changes during early degeneration compared to later degenerative stages. Our results suggest that future prospective studies should include automated T1ρ and T2 metrics as early biomarkers for disc degeneration-induced lower back pain.

Keywords: quantitative MRI, intervertebral disc degeneration, T1ρ/T2, degenerative disc disease, lumbar spine

Lower back pain (LBP) has a tremendous impact on society; both physically through the morbidity of afflicted individuals, and financially, through lost productivity and increased health care costs. An estimated 149 million work days are lost every year because of lower back pain,1 with total costs estimated to be $100–200 billion annually (of which two-thirds are due to lost wages and reduced productivity).2 Seen as a growing trend since the 1990s, morbidity and chronic disability now account for nearly half of the US health burden with LBP contributing the largest number of years lived with disability (YLDs).3 As the population ages, the number of individuals suffering from LBP is likely to increase substantially.4 Despite the significance of this problem, the etiology of LBP is not well understood, and there are few reliable methods to prospectively determine the appropriate course of patient care (i.e., conservative management, interventional treatment or surgery).

A major challenge is that there are many potential sources of back pain (intervertebral discs, facet joints, vertebral bodies, muscles, tendons, nerve roots) and localizing a pain generator is difficult. Currently, congruent clinical findings along with MRI abnormalities are used to identify the most probable pain generators. Diagnostic injections are then often performed to confirm the pain source and inform the treatment strategy. This has some success, but clearly there is a need for more objective non-invasive biomarkers to localize specific pain generators. Additionally, morphological changes identified by traditional MRI techniques are typically seen in the later stages of disease progression. Biomarkers that could identify early stage changes could potentially lead to improved disease management and initiation of preventive interventions, such as physical therapy, at an earlier stage of disease.

In this study, we focus on intervertebral discs (IVD). A healthy intervertebral disc (IVD) consists of two distinct structural regions, the central nucleus pulposus (NP) and the peripheral annulus fibrosus (AF). The proteoglycan and water content of the disc increases on progressing from the outer AF to the NP, while the collagen content decreases from the outer AF to the NP.5 The composition and organization of these regions governs the disc’s mechanical function. The most dramatic changes in IVD with aging and degeneration are the altered biochemical composition and location of these structures. Degeneration in turn leads to loss of structural integrity (height and width) of the disc, which is a known cause for LBP. Quantitative imaging markers T1ρ and T2 have been shown to be promising techniques for in vivo diagnosis of biochemical degeneration,6,7 and have been previously shown to be correlated with LBP-related dissability.8,9 But to date, this analysis has been based on subjective identification of the regions of interest as it has primarily involved manual segmentation of the central NP region.10,11 Such techniques are subject to bias, time-consuming, and tedious. Further, while some studies have also looked at degeneration of the AF,7 no study to date has examined the spatial variations of T1ρ and T2 within these regions. Previous studies in the knee have shown that analyzing the spatial distribution of T1ρ and T2 using laminar and texture analysis is better at identifying degeneration than simple average values, leading to improved and earlier identification of cartilage matrix abnormalities.12

Here, we describe a technique for quantification of T1ρ and T2 measurements in the lumbar intervertebral discs, with semi-automatic segmentation of the NP and AF, to characterize the regional variations within these structures as a tool in the assessment of LBP for identification of early disc pathology. We believe this would help allow appropriate early conservative interventions before later stage surgical interventions are necessary.

METHODS

This is an analytic case-control study with Level 3 evidence where groups of intervertebral discs are separated by the current presence or absence of disease.

Subjects

All examinations were performed in accordance to the rules and regulations from the local Human Research Committee. The nature of the examination was fully explained to the participants and written informed consent was obtained prior to proceeding. Sixteen subjects (age range = 20–67 years, mean age = 48.12 ± 14.08 years, males = 5) with documented lower back pain participated in this study. Their Oswestry disability index ranged from 11 to 32 (mean = 23.58 ± 7.18, n = 12). Patients with prior back surgery, scoliosis, spine fractures, spinal infections, and tumors were excluded. Additionally, three healthy volunteers were scanned twice to examine the reproducibility of this technique. They were asked to leave the examination suite and walk around before being repositioned between the two exams.

MRI

MRI was performed at 3 T on a GE 750W scanner (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) with an embedded posterior array GEM (Geometry Embracing Method) coil. Depending on the patient size, 8–12 elements of the receive array (corresponding to a coverage of 24–48 cm) were engaged in signal reception, through an automatic coil selection software on the scanner. Quantitative T1ρ and T2 maps were acquired with a concatenated T1ρ/T2 sequence using 3D segmented SPGR acquisition—MAPSS.13 The imaging parameters used were—repetition time = 5.8 ms, bandwidth = 62.5 KHz, field-of-view = 20 cm, in-plane resolution = 0.8 mm, through-plane resolution = 8 mm. The T1ρ magnetization preparation consisted of four spin-lock times (TSL = 0, 10, 40, 80 ms) and 500 Hz spin lock frequency, and the T2 preparation used four echo times (TE = 0, 12, 25, 51 ms). The acquisition time for this combined sequence was 8 min. Additionally, sagittal T2 weighted images with no fat saturation were acquired with a 3D fast spin echo sequence (echo time/repetition time = 103/2,250 ms, bandwidth = 62.5 KHz, field-of-view = 24 cm, in-plane resolution = 0.9 mm, through-plane resolution = 1.6 mm) for Modified Pfirrmann grading.14

Image Analysis

All images were transferred to a Sun Workstation (Sun Microsystems, Mountain View, CA), which was used to perform image analysis. T1ρ and T2 parametric maps were generated by performing monoexponential fittings on a pixel-by-pixel basis using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm developed in-house. The equations used were:

For T1ρ map: , where TSL is the spin-lock time, S is the signal intensity of the image at that particular TSL, and S0 is the signal intensity at TSL = 0.

For T2 maps: , where TE is the echo time, S is the signal intensity of the image at that particular TE, and S0 is the signal intensity at TE = 0.

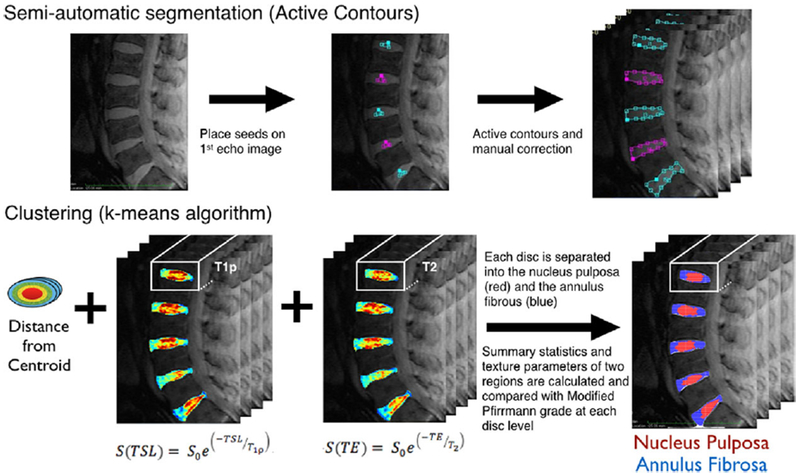

Disc segmentation and quantitative analysis was carried out using the new semi-automatic technique that was developed within the framework of the in-house image processing toolkit (IPP15) using Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA). Five intervertebral discs per subject (from L1–L2 to L5–S1) were examined volumetrically (four slices). Figure 1 shows the steps involved. Seed region-of-interests (ROIs) were initially placed in the center of the five discs on the TSL = TE = 0 image on a single slice. An active contours-based regiongrowing algorithm16 was then used to segment the entire discs in that slice. Based on these ROIs, the adjacent slices were then automatically segmented,17 for a total of four central slices to obtain volumetric ROIs of the five lumbar discs. The volumes were restricted to four slices to ensure minimal partial volume effects. The automatically segmented ROIS were reviewed and manually adjusted. Next, an unsupervised clustering analysis was performed on three dimensional feature space to automatically identify the boundary between NP and AF. The feature vector used included both topological and relaxation time information. The parameters used to describe each voxel were the distance from the disc centroid, T1ρ and T2 values. These were chosen based on; (i) the NP is located centrally in a healthy disc, and is surrounded by the AF5; and (ii) T1ρ and T2 of NP in a healthy disc is higher than that of the AF.7,18 The features were normalized to a 0–1 range, and the relaxation times were given a higher weight-age than the topological feature (1.25 vs. 1) in the clustering analysis. Morphological post-processing was carried out to ensure two contiguous regions. The region that resulted in the lesser difference after applying the closing morphological operation was assigned to be the NP.

Figure 1.

Step-by-step procedure showing lumbar intervertebral disc segmentation and T1ρ and T2-based quantitative analysis used in the techniques describe here.

Summary statistics of the T1ρ and T2 relaxation time maps were calculated separately for the two regions, NP and AF. Additionally, GLCM (Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix)-based19 texture analysis of the relaxation time maps was performed on the two regions. This provided important information regarding regional variation as GLCM extracts information related to the spatial distribution of pixel intensities using their co-occurrence at specific orientations and offsets. One pixel offset and four directions were used to extract nine GLCM features for each map in both regions. The features included contrast, dissimilarity and homogeneity from the contrast group, angular-second-moment (ASM), energy and entropy from the orderliness group, and mean, variance and correlation from the statistics group.

Reproducibility

To examine the reproducibility of this technique three volunteers underwent two scan sessions. After the first scan, the volunteers were asked to walk out of the magnet suite before reentering it to be repositioned for the second one. The complete image analysis was performed independently for the images acquired in the two sessions. Reproducibility was measured as the percentage coefficient of variation (% CV) between the T1ρ and T2 values in the NP and AF generated in the two sessions.

Clinical Evaluation

Modified Pfirrmann grading14 was performed, by a board certified neuroradiologist (JT) with 5 years of experience, based on the T2-weighted images. Grades ranged from healthy (Modified Pfirrmann grade 1) to severe degeneration (Modified Pfirrmann grade 8). This grading system was used as it allows better separation between the early degenerative grades. Grades 1–5 were characterized as having no loss of disc height, but were distinguished based on the signal intensity of the NP and AF, as compared with the CSF and the presacral fat. Distinction between grades 6–8 was based on morphological changes, specifically on the percentage reduction in the disc height.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using JMP Pro 11 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A linear mixed-effects regression analysis of MR-derived parameters on Modified Pfirrmann grade was performed to determine the association between the MR relaxation time based quantitative parameters and clinical (qualitative) degenerative grades. Modified Pfirrmann grade was modeled as the fixed-effects component, and the subject as the random-effects component to account for multiple discs measured within each subject. This modeling approach allowed explicit estimates of the within-subject and between-subject variations. The random-effect component models the mean of a subject’s MR-based quantitative parameters (T1ρ/T2 mean, texture, etc) as a Gaussian distributed random observation from a population distribution. Individual lumbar measurements are then modeled as having an additional within-subject variation component (independently and identically distributed zero mean Gaussian variables). Pairwise comparisons were carried out to check for significant differences between grades using Students t-test. All statistical analysis was considered significant at p < 0.05. Additionally, confirmatory Spearman’s correlations between Modified Pfirrmann grades and MRI-based quantitative parameters were performed.

RESULTS

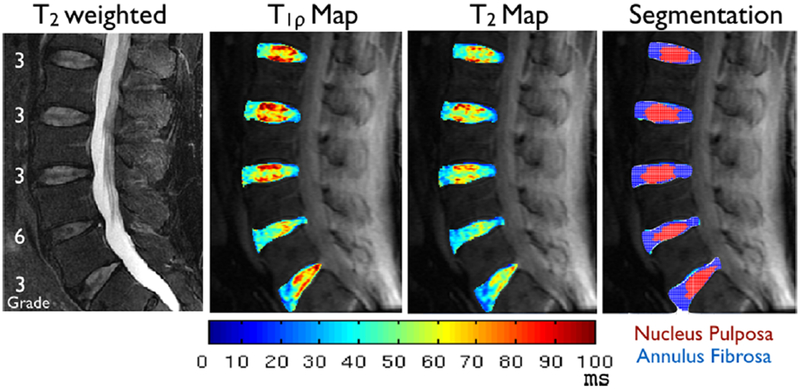

Figure 2 shows representative images from one subject. T1ρ and T2 color maps illustrate the spatial variations in those values within the intervertebral disc. There is heterogeneous distribution of T1ρ and T2 values in both the NP and the AF. Results of the reproducibility test are shown in Table 1. The CV for T1ρ and T2 was 4.66% and 3.13%, respectively in the NP, with slightly higher values of 6.75% and 6.12% in the AF. The CV for the NP and AF volumes segmented with k-means clustering was 3.18% and 1.72% respectively. These variations are substantially smaller than the variations observed in the study cohort for discs classified with the same Modified Pfirrmann grade. Table 1 lists the mean CVs over the 8 grades.

Figure 2.

Representative T2-weighted images and T1ρ and T2 color maps from a 62-year-old subject with lower back pain. The Modified Pfirrmann grades of the five lumbar discs for this subject are overlaid on the T2-weighted anatomical image. Also shown are the segmented results for the discs, with NP in red and AF in blue.

Table 1.

Percentage Coefficient of Variance (% CV) in the T1ρ and T2 Values and Volumes of the NP and AF Observed in the Volunteer Images for the Reproducibility Test and the Corresponding Variations Seen in the Discs of LBP Patients Within Each Modified Pfirrmann Grade

| % CV | T1ρ | T2 | Volumes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results of reproducibility study (averaged over three volunteers) | ||||

| All discs (n = 15) | NP | 4.66 ± 2.62 | 3.13 ± 1.69 | 3.18 ± 2.47 |

| AF | 6.75 ± 2.97 | 6.12 ± 4.99 | 1.72 ± 0.99 | |

| Variation observed in subjects within each Modified Pfirrmann grade | ||||

| Grade 1 (n = 3) | NP | 12.96 | 20.74 | 19.28 |

| AF | 22.75 | 18.32 | 14.55 | |

| Grade 2 (n = 35) | NP | 24.4 | 15.25 | 16.27 |

| AF | 18.31 | 16.64 | 10.54 | |

| Grade 3 (n = 14) | NP | 17.91 | 17.86 | 20.8 |

| AF | 14.48 | 13.42 | 16.59 | |

| Grade 4 (n = 7) | NP | 8.78 | 6.99 | 26.93 |

| AF | 8.04 | 9.43 | 20.05 | |

| Grade 5 (n = 2) | NP | 14.29 | 14.28 | 2.01 |

| AF | 9.24 | 14.75 | 2.37 | |

| Grade 6 (n = 9) | NP | 15.95 | 15.94 | 30.47 |

| AF | 19.99 | 18.57 | 25.46 | |

| Grade 7 (n = 8) | NP | 7.8 | 10.26 | 30.79 |

| AF | 28.51 | 17.14 | 27.57 | |

| Grade 8 (n = 2) | NP | 11.25 | 9.8 | 8.02 |

| AF | 4.61 | 1.78 | 3.79 | |

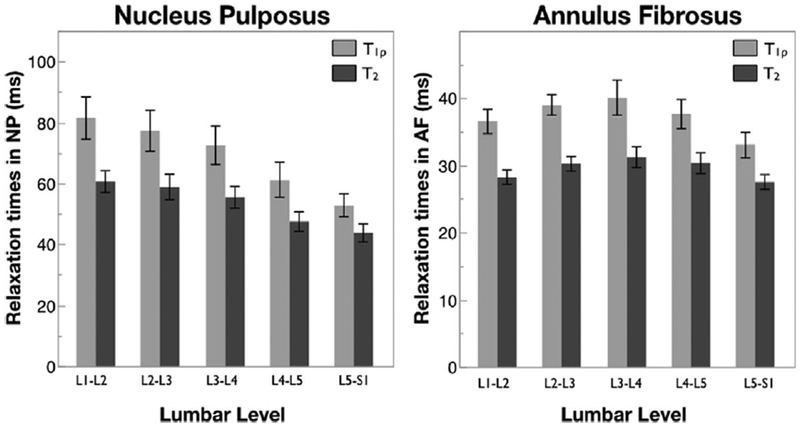

All five lumbar discs were analyzed for each subject. The median Modified Pfirrmann Grade increased as a function of lumbar level, with values of 2, 2, 2.5, 4, 4.5 from levels L1/L2 to L5/S1, respectively. Figure 3 shows mean T1ρ and T2 values in the NP and AF as a function of lumbar level. Decreasing T1ρ and T2 values were observed in the NP from L1/L2 to L5/S1. Mixed-effect regression analysis showed a significant relation between NP T1ρ and T2 values with lumbar level. In contrast the T1ρ and T2 values in the AF did not show such a trend.

Figure 3.

T1ρ and T2 relaxation times in the NP and AF as a function of lumbar level. Error bars represent standard error. n = 16 for each lumbar level.

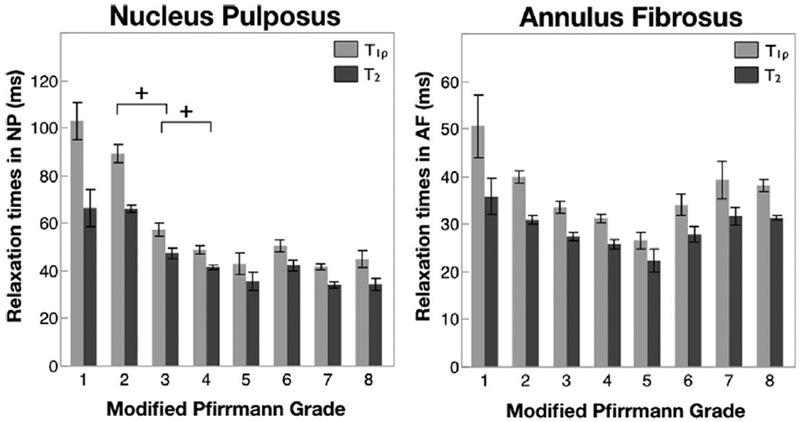

A total of 80 discs were categorized according to the Modified Pfirrmann grade. The distribution among the grades was; 3 in grade 1, 35 in grade 2, 14 in grade 3, 7 in grade 4, 2 in grade 5, 9 in grade 6, 8 in grade 7, 2 in grade 8. Graphs of mean T1ρ and T2 values in the NP and AF as a function of Modified Pfirrmann grade are shown in Figure 4. Error bars represent standard error. In the NP, a clear trend of decreasing T1ρ and T2 values with increasing grade of degeneration can be seen. Mixed-effect regression analysis showed a significant relation between T1ρ and T2 values with the clinical degeneration grade. A significant difference was observed in the T1ρ values between consecutive Modified Pfirrmann grades 2 and 3, and 3 and 4. Additionally, T1ρ values in Modified Pfirrmann grade 1 and 2 were significantly different than all other grades. The T2 values showed similar trends. A second mixed-effect model that included lumbar level as another fixed effect was performed and the results demonstrated that the Modified Pfirrmann grade continued to have a significant effect on the NP T1ρ and T2 parameters even after accounting for the lumbar level.

Figure 4.

T1ρ and T2 relaxation times in the NP and AF as a function of Modified Pfirrmann grade. n = 3 in grade 1, 35 in grade 2, 14 in grade 3, 7 in grade 4, 2 in grade 5, 9 in grade 6, 8 in grade 7, 2 in grade 8. Error bars represent standard error. + indicates significant difference in paired t-test (p < 0.05).

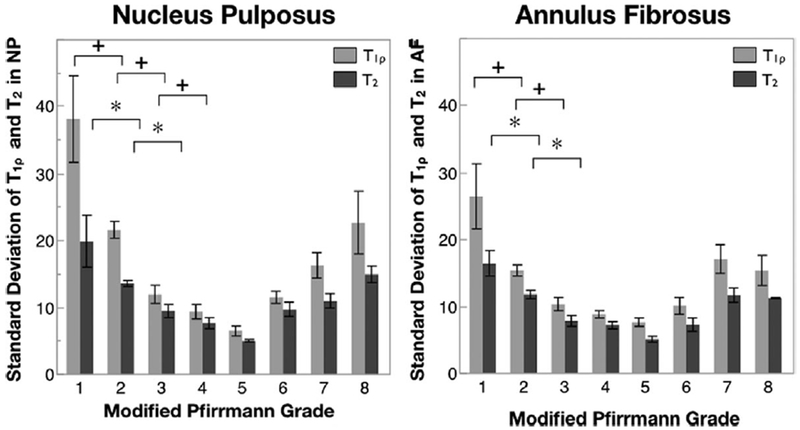

Standard deviation in the T1ρ and T2 values in the NP and AF are shown in Figure 5 as a function of the Modified Pfirrmann grade. Error bars represent standard error. Unlike the mean T1ρ values that decrease continuously with degeneration, the standard deviation of T1ρ values decreases sharply during early degeneration, and then stabilizes during intermediate degeneration before increasing again in severely degenerated discs. Pairwise Students t-test within the mixed effects model shows significant difference between consecutive Modified Pfirmmann grades 1 and 2, 2 and 3, and 3 and 4 for T1ρ values in the NP. A similar trend is seen in the AF, and also with T2 values in both compartments, though significant difference in consecutive grades is seen only between grades 1 and 2, and 2 and 3. For all four measurements, values in grade 1 are significantly different than in grades 2 to 7, and values in grade 2 are significantly different than those is grades 3–6.

Figure 5.

Standard deviation of T1ρ and T2 relaxation times in the NP and AF as a function of Modified Pfirrmann grade. n = 3 in grade 1, 35 in grade 2, 14 in grade 3, 7 in grade 4, 2 in grade 5, 9 in grade 6, 8 in grade 7, 2 in grade 8. Error bars represent standard error. + indicates significant difference in paired t-test (p < 0.05) in T1ρ in consecutive grades, while *indicates significant difference in paired t-test (p < 0.05) in T2 in consecutive grades.

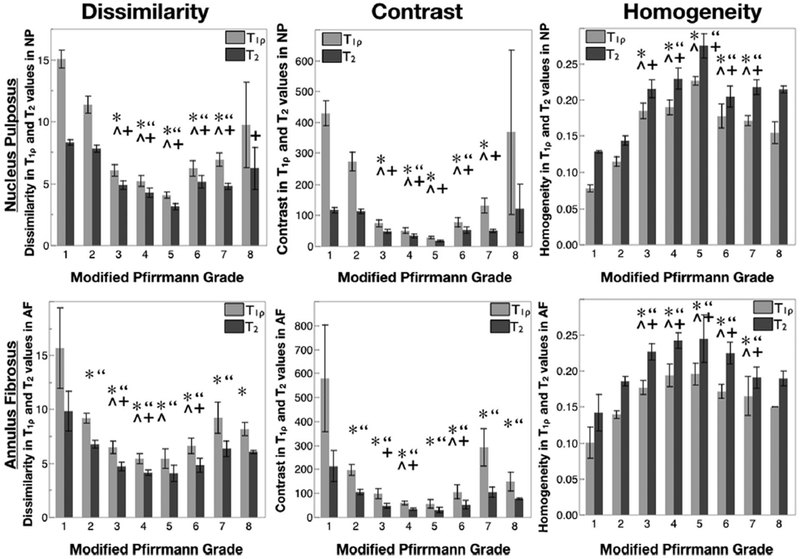

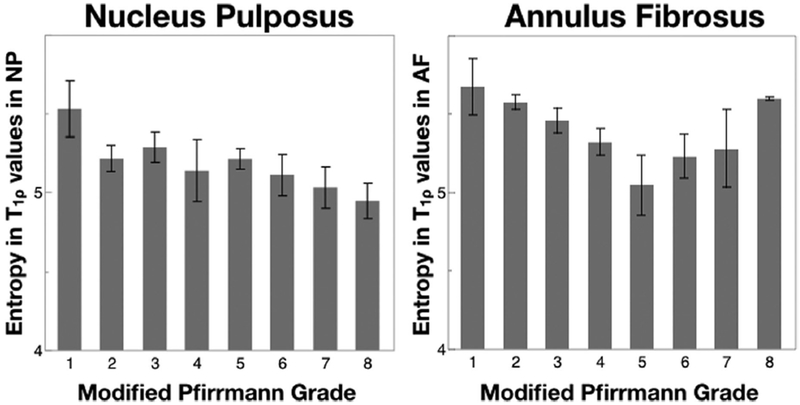

For evaluating metrics of disc texture, the contrast group parameters (contrast, dissimilarity and homogeneity) for T1ρ and T2 values in NP and AF are shown in Figure 6. As can be seen, these results mirror the trends seen in the standard deviation. Contrast and dissimilarity decrease while homogeneity increases with disc degeneration, signifying that more pixels with similar relaxation times were neighboring in discs with higher degeneration. For T1ρ values in NP the three contrast texture parameters in grade 1 and 2 were significantly different from those in grades 3–7, according to pairwise Student’s t-test. T2 values in NP and T1ρ and T2 values in AF followed similar trends. The significant differences for these parameters are also noted in Figure 6. Figure 7 shows orderliness parameter, entropy for T1ρ values in both the NP and the AF. Entropy in the NP decreases with degeneration, whereas in the AF, it decreases in early degeneration before rising again in severely degenerated discs. Mixed-effect regression analysis shows a significant relation between T1ρ and T2 texture values with the clinical degeneration grade. The relation is stronger (p < 0.001) in the contrast parameters than in entropy (p = 0.036 in NP and p = 0.006 in AF).

Figure 6.

Dissimilarity, contrast and homogeneity (texture parameters from the contrast group) in T1ρ (light) and T2 (dark) relaxation times in the NP (top row) and AF (bottom row) as a function of Modified Pfirrmann grade. n = 3 in grade 1, 35 in grade 2, 14 in grade 3, 7 in grade 4, 2 in grade 5, 9 in grade 6, 8 in grade 7, 2 in grade 8. Error bars represent standard error. *, ^ indicates significant difference between that grade and grades 1 and 2 in paired t-test (p<0.05) respectively for T1ρ values. “, +indicates significant difference between that grade and grades 1 and 2 in paired t-test (p<0.05) respectively for T2 values.

Figure 7.

Entropy (texture parameter in the orderliness group) in T1ρ relaxation times in the NP and AF as a function of Modified Pfirrmann grade. n = 3 in grade 1, 35 in grade 2, 14 in grade 3, 7 in grade 4, 2 in grade 5, 9 in grade 6, 8 in grade 7, 2 in grade 8. Error bars represent standard error.

Table 2 summarizes the Spearman’s correlation coefficients between the clinical Modified Pfirrmann grading and the T1ρ and T2-based quantitative parameters in both disc compartments. They confirm the results from the mixed effect regression analysis.

Table 2.

Spearman’s Correlation Between Modified Pfirrmann Grade and All T1ρ and T2 Derived Parameters for NP and AF

| Spearman’s ρ |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | NP T1ρ | NP T2 | AF T1ρ | AF T2 |

| Global parameters | ||||

| Mean | −0.8589* | −0.8474* | −0.3257** | −0.2340*** |

| Standard deviation | −0.5133* | −0.4570* | −0.3757** | −0.4042** |

| Texture parameters | ||||

| Contrast | −0.5241* | −0.6567* | −0.3666** | −0.4132** |

| Dissimilarity | −0.6077* | −0.7011* | −0.3890** | −0.4046** |

| Homogeneity | 0.6146* | 0.6871* | 0.3677** | 0.3142** |

| Angular second moment | 0.0820 | 0.0012 | 0.1685 | 0.1500 |

| Energy | 0.1477 | 0.0693 | 0.3274** | 0.2806*** |

| Entropy | −0.2086 | −0.0492 | −0.2883*** | −0.3127** |

| Mean | −0.8580* | −0.8402* | −0.2741*** | −0.1809 |

| Variance | −0.4491* | −0.3736** | −0.3536** | −0.3880** |

p < 0.0001;

p < 0.005;

p < 0.05.

DISCUSSIONS

In this study we describe a semi-automated technique for quantification of T1ρ and T2 relaxation time maps for the lumbar intervertebral discs. T1ρ and T2 provide information about slow-motion water interactions, between bulk water and its macromolecular environment and between water protons themselves, respectively. Previous studies in both cartilage and intervertebral discs have shown that T1ρ is more sensitive to macromolecular changes like proteoglycan (PG) loss and less dependent on the integrity of collagen fibers.20,21 T2, on the other hand is highly related to collagen integrity while not being as sensitive to PG loss.20,22 In the intervertebral disc, the nucleus pulposus and the annulus fibrosus are comprised of varying proportions of PG and collagen,5 and as such T1ρ and T2 are excellent biomarkers for monitoring the biochemical content of the intervertebral disc. Compositional changes within the NP and AF caused by degeneration occur much earlier than the visually observable structural changes on conventional MRI sequences. The proposed technique rigorously quantifies these biochemical changes taking into account subtle regional variations to allow interpretation of early degenerative changes that are difficult to interpret with traditional clinical grading scores.

T1ρ and T2 relaxation maps were obtained in 16 subjects with different grades of disc degeneration. This study confirmed the previously reported negative relationship between relaxation times and lumbar level.8,18 The average relaxation time values measured in the NP were lower than previously reported. We believe this to be due to our study cohort being entirely of patients suffering from lower back pain, with a higher mean age than the previous studies. Additionally, unlike the earlier study where the measurement was taken in a single, manually identified 5mm-diameter ROI in the mid-sagittal section in the center of the NP, here the measurement was taken in a large volumetric region defined over the entire NP.

A trend of decreasing T1ρ and T2 values was observed with increasing degree of degeneration. This corroborates with previously reported results. Notably though, the significant differences in the mean T1ρ and T2 values in the NP of early stage degenerative discs observed here was not shown in the previous study.8 This demonstrates the potential of this technique as a tool for distinguishing early disc degenerative changes at the biochemical level.

Similar significant differences were found when evaluating the standard deviation of T1ρ and T2 values as well as in the texture parameters of these variables as a function of Modified Pfirrmann grade. Though unlike the mean, and more interestingly, these parameters did not show a monotonous trend with increasing degeneration. Standard deviation, dissimilarity and contrast decreased sharply with degeneration in the early stages before increasing again in the later stages of severe degeneration. This increase though is more gradual and significant differences are not seen within the consecutive grades. The reason for this increase is likely the gross morphological changes seen in severely degenerated discs, namely the nitrogen bubbles that form in the NP.23 But these advanced structural changes are easily identifiable with conventional imaging techniques and hence not a target for this quantitative technique.

Homogeneity shows an opposite effect, with sharply increasing value during early degeneration, which then plateaus and decreases in the severely degenerated discs. A likely cause of the initial increase in homogeneity could be the destruction of the collagen network and hence disorganization in the disc structure.

GLCM entropy is a measure of disorder in an image, with high values signifying that the probability of pixel co-occurrence is uniform throughout the ROI being investigated. Decreasing entropy values with Modified Pfirrmann grade in the NP thus reflect the loss of uniformity in the region due to compositional changes occurring with degeneration.

T1ρ and T2 are highly correlated with Spearman’s ρ = 0.9821 (p < 0.0001). T2 shows trends that are very similar, but the effects in T1ρ are more prominent due to the larger dynamic range in the T1ρ values.

Compared to the NP, the trends in the AF were not as clear. We considered the posterior and the anterior annulus as a single compartment. Previous studies have evaluated the two as distinct compartments due to their dissimilar loading patterns and shown differing trends in their T2 values with degeneration.7 Additionally, conflicting results have been reported in the T2 trends in the AF with some reporting an increasing trend, while others show a decrease in T2 values with degeneration.24,25 Our results show an initial decrease followed by a slight increase. It should be noted that we use the Modified Pfirmman14 grading criterion (with more grades) as opposed to the Pfirrmann26 grading criterion used in these studies.

Another notable distinction in the NP and the AF that would reflect in their T1ρ and T2 values is the difference in hydration between the two compartments. Healthy NP has higher water content than the AF (80% vs. 70%).27 Degeneration causes loss of GAG, which in turn causes loss of water retention and hence dehydration in the disc. This effect is more prominent in the NP compared to the AF.

The primary limitation of the study was the small sample size, particularly because the discs were classified into eight grades and each grade was not equally represented. Additionally, the patient population was not restricted to those with discogenic LBP, and hence no correlations with clinical symptoms (like pain scores or disability index) could be drawn. Studies with a selective patient population have previously shown such correlations.8,9 Additional studies with a larger and more selective sample size are warranted to explore this. Future studies will also incorporate a broader range of disability in the study population. The current study used 8 mm thick slices as a compromise between imaging time, spatial extent and image SNR. Future studies will incorporate compressed sensing-based techniques to obtain higher resolution images while maintaining high SNR and shorter scan times. Another limitation, albeit without an easy solution, was the lack of gold standards, such as histology of the discs to unambiguously verify the NP and AF classification from the data acquired in vivo.

CONCLUSION

Modified Pfirrmann grading is a quantitative technique for characterizing disc degeneration. Distinction in the early degenerative grades is difficult with this method since those are defined as having no morphological changes and early disc changes often go unrecognized in conventional sequences. In contrast, the quantitative biomarkers described in this study allow for more objective characterization. As shown here, they are sensitive to early disc degeneration, and have the potential of being able to make that differentiation better. This would make an important tool in the assessment of LBP for identification of early disc pathology, thereby allowing appropriate early preventative/conservative interventions before surgical intervention is needed. Present data suggest that future prospective studies in lower back pain should include automated T1ρ and T2 metrics as biomarkers for early disc degeneration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr. Martin Kretzschmar for helpful discussions related to clinical interpretations during the initial stages of study design.

Grant sponsor: Radiology and Biomedical Imaging, UCSF.

REFERENCES

- 1.Frymoyer JW, Cats-Baril WL. 1991. An overview of the incidences and costs of low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am 22:263–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz JN. 2006. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: socioeconomic factors and consequences. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:21–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJL. 2013. The state of US health, 1990–2010. JAMA 310:591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, et al. 2012. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum 64:2028–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raj PP. 2008. Intervertebral disc: anatomy-physiology-pathophysiology-treatment. Pain Pract 8:18–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mwale F, Iatridis JC, Antoniou J. 2008. Quantitative MRI as a diagnostic tool of intervertebral disc matrix composition and integrity. Eur Spine J 17:432–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trattnig S, Stelzeneder D, Goed S, et al. 2010. Lumbar intervertebral disc abnormalities: comparison of quantitative T2 mapping with conventional MR at 3.0 T. Eur Radiol 20:2715–2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blumenkrantz G, Zuo J, Li X, et al. 2010. In vivo 3.0-tesla magnetic resonance T1ρ and T2 relaxation mapping in subjects with intervertebral disc degeneration and clinical symptoms. Mag Reson Med 63:1193–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zuo J, Joseph GB, Li X, et al. 2012. In vivo intervertebral disc characterization using magnetic resonance spectroscopy and T1ρ imaging: association with discography and Oswestry Disability Index and Short Form-36 Health Survey. Spine 37:214–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Auerbach JD, Johannessen W, Borthakur A, et al. 2006. In vivo quantification of human lumbar disc degeneration using T1ρ-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Spine J 15:338–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borthakur A, Maurer PM, Fenty M, et al. 2011. T1ρ magnetic resonance imaging and discography pressure as novel biomarkers for disc degeneration and low back pain. Spine 36:2190–2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carballido-Gamio J, Stahl R, Blumenkrantz G, et al. 2009. Spatial analysis of magnetic resonance T1ρ and T2 relaxation times improves classification between subjects with and without osteoarthritis. Med Phys 36:4059–4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, Wyatt C, Rivoire J, et al. 2013. Simultaneous acquisition of T1ρ and T2 quantification in knee cartilage: repeatability and diurnal variation. J Magn Reson Imaging 39:1287–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffith JF, Wang Y-XJ, Antonio GE, et al. 2007. Modified Pfirrmann grading system for lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine 32:E708–E712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carballido-Gamio J, Bauer JS, Keh-Yang Lee, et al. 2006. Combined image processing techniques for characterization of MRI cartilage of the knee. IEEE 3043–3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan TF, Vese LA. 2001. Active contours without edges. IEEE Trans Image Process 10:266–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carballido-Gamio J, Bauer JS, Stahl R, et al. 2008. Inter-subject comparison of MRI knee cartilage thickness. Med Image Anal 12:120–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blumenkrantz G, Li X, Han ET, et al. 2006. A feasibility study of in vivo T1ρ imaging of the intervertebral disc. Magn Reson Imaging 24:1001–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haralick RM, Shanmugam K, Dinstein I. 1973. Testural features for image classification. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern SMC-3:610–621. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Regatte RR, Akella SVS, Borthakur A, et al. 2002. Proteoglycan depletion-Induced changes in transverse relaxation maps of cartilage. Acad Radiol 9:1388–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akella SVS, Regatte RR, Wheaton AJ, et al. 2004. Reduction of residual dipolar interaction in cartilage by spin-lock technique. Magn Reson Med 52:1103–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xia Y, Farquhar T, Burton-Wurster N, et al. 1997. Origin of cartilage laminae in MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 7:887–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ford LT, Gilula LA, Murphy WA, et al. 1977. Analysis of gas in vacuum lumbar disc. Am J Roentgenol 128:1056–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe A, Benneker LM, Boesch C, et al. 2007. Classification of intervertebral disk degeneration with axial T2 mapping. AJR Am J Roentgenol 189:936–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stelzeneder D, Welsch GH, Kovács BK, et al. 2012. European journal of radiology. Eur J Radiol 81:324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfirrmann CWA, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M, et al. 2001. Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine 26:1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urban JP, Roberts S. 2003. Degeneration of the intervertebral disc. Arthritis Res Ther 5:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]