Abstract

Objective:

Young adult (YA) cancer survivors who received gonadotoxic therapy are at risk for impaired fertility and/or childbearing difficulties. This study explored the experiences and financial concerns of survivors pursuing family-building through assisted reproductive technology (ART) and adoption.

Methods:

Retrospective study of data collected from grant applications for financial assistance with family-building. Grounded theory methodology using an inductive data-driven approach guided qualitative data analysis.

Results:

Participants (N=46) averaged 32 years old (SD=3.4), were primarily female (81%) and married/partnered (83%). Four main themes were identified representing the (1) emotional experiences and (2) financial barriers to family-building after cancer, (3) perceived impact on partners, and (4) disrupted life trajectory. Negative emotions were pervasive, but were balanced with hope and optimism that parenthood would be achieved. Still, the combination of high ART/adoption costs, the financial impact of cancer, and limited sources for support caused extreme financial stress. Further, in the face of these high costs, many survivors reported worry and guilt about burdening partners, particularly as couples failed to meet personal and societal expectations for parenthood timelines.

Conclusion:

After cancer, YAs face numerous psychosocial and financial difficulties in their pursuits of family-building when ART/adoption is needed to achieve parenthood. Survivors interested in future children may benefit from follow-up fertility counseling post-treatment including discussion of ART options, surrogacy, and adoption, as appropriate, and potential barriers. Planning for the financial cost and burden in particular may help to avoid or mitigate financial stress later on.

Keywords: Cancer Survivors, Fertility, Infertility, Long-term Cancer Survivors, Oncology

Young adult (YA, 18–39 years old) cancer survivors who received gonadotoxic therapy are at risk for impaired fertility and childbearing difficulties. A growing literature has characterized survivors’ reproductive concerns and recommends increased counseling and referral of newly diagnosed patients to reproductive specialists before treatment.1,2 Clinical guidelines include discussions of infertility risk and options for fertility preservation before treatment as a part of standard care.3,4 While survivorship care guidelines include monitoring fertility post-treatment,5 guidance around follow-up counseling for the emotional and financial burden of family-building appears nonexistent. The experiences of YA survivors pursuing parenthood after gonadotoxic therapy, irrespective of fertility preservation history, and particularly for those unable to achieve pregnancy naturally, are not well understood.

Family-building options for patients who experience infertility or fertility impairment from cancer treatment typically requires the use of assisted reproductive technology (ART) with fresh or frozen gametes or with donated gametes. Female patients unable to carry a pregnancy can pursue surrogacy with a gestational carrier. Alternatively, patients may choose adoption. Factors affecting family-building options and decision-making include reproductive health, fertility preservation, and the preferences and values of the prospective parents.6,7 Fertility problems and parenthood uncertainty are significant sources of distress for YA survivors.8–10

Another critical factor in family-building decisions is cost. Costs can be difficult to predict, given uncertainty surrounding what ART procedures may be needed (e.g., number of in vitro fertilization [IVF] cycles to achieve pregnancy) and extent of insurance coverage.11 In the U.S., cost estimates range from $12,000–24,000 per IVF cycle ($24,000–50,000 for IVF-donor egg cycles) and $40,000–$85,000 per live birth using IVF, as more than one cycle is often needed; $100,000-$150,000 for gestational carrier; and $30,000–40,000 for adoption.12,13 An estimated 85% of IVF costs are out-of-pocket for patients.14 Compassionate care discounts and cancer charity contributions exist for pre-treatment fertility preservation,11 but financial assistance is rarer for post-treatment family-building.

Simultaneously, family-building costs may occur amidst “financial toxicity” effects of cancer (e.g., medical debt, education/career disruption) and age-related financial pressures (e.g., student loans).15 YA survivors experience greater cancer-related financial toxicity than older survivors,16 and are at greater financial risk than non-cancer peers.17 The combined difficulties of fertility impairment and financial effects pose challenges for survivors hoping to achieve parenthood.

This study aimed to characterize the real-world experiences of YA survivors pursuing family-building through ART, surrogacy, or adoption, focusing on the financial pressures. The study was conducted in collaboration with The Samfund, a nonprofit organization that provides YA survivors with online support and financial assistance (www.thesamfund.org). In addition to family-building, grant categories include medical/insurance payments, rent/mortgage assistance, continuing education, and student loan payments, among others. Family-building grants are no more than $4,000 and are intended to support ART/adoption financing, but require survivors to cover the remaining costs.

Methods

This study was approved by the Northwell Health Institutional Review Board. Retrospective data collected from family-building grant applications submitted to The Samfund between 2007–2016 were evaluated. All grant applicants signed a waiver authorizing use of their de-identified data for research purposes.17 This study reports on data collected from the subset of family-building grant recipients. All grant funds were paid directly to billing departments (e.g., reproductive medicine clinics, adoption agencies), thus confirming survivors’ pursuit of the family-building option described in their application.

Participants

To be eligible for a grant, applicants had completed treatment and were in remission, were at least one post-treatment with stable disease, or were in remission and on long-term targeted or hormonal therapy. All recipients of family-building grants were included.

Data Collection

Participants submitted grant applications through The Samfund web portal, which required reporting of sociodemographic, medical, and financial information and four short essays (Supplemental Table). Grant selection criteria and procedures have been described previously.17

Data Analysis

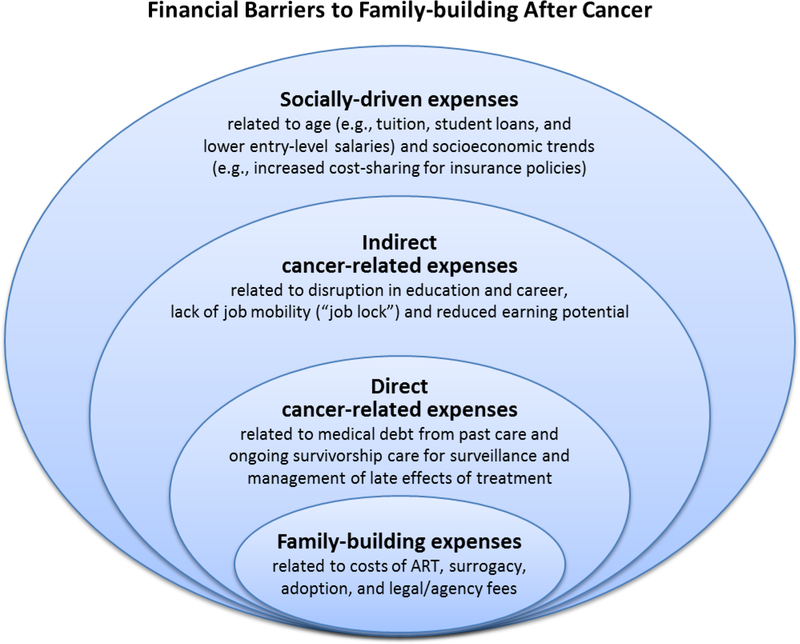

Analyses were conducted on data from 46 family-building grant applications. Descriptive statistics evaluated sociodemographic, medical, and financial characteristics. Qualitative analyses were guided by grounded theory using thematic content analysis with an inductive, data-driven approach.18 Open coding was conducted by two coders to create a codebook and establish uniformity in coding (inter-rater reliability >80%).19,20 The codebook was modified if concepts arose that were not represented by existing codes until saturation was reached and no new themes emerged from the data. Each transcript was then coded by two coders following an iterative process of individual and consensus coding using the codebook. A round of axial coding was conducted reviewing codes and categories and identifying patterns and developing a thematic framework. With respect to financial-related codes, axial coding was guided by a conceptual framework of the financial barriers to family-building after cancer, based on the literature and clinical experiences of co-authors (Figure 1).11,21 Themes were assessed through analyst triangulation and reviewed by a cancer and fertility specialist.22 As a final step, The Samfund reviewed findings as patient research partners, but made no changes to themes or the thematic framework. Independent sample t-tests and chi-square tests examined whether themes varied across subgroups based on quantitative descriptive data.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the financial barriers to family-building after cancer.

Results

Sample Description

The sample (N=46) was primarily female (81%), partnered (83%), nulliparous (74%), and averaged 32 years old (SD=3.4); median time since most recent treatment was 3.8 years and 20% had undergone fertility preservation before treatment (Table 1). Seventy-six percent of participants identified a family-building plan they were committed to, with most pursuing ART using fresh/frozen/donated gametes to achieve pregnancy in the female survivor/partner (n=16) or a gestational carrier (n=10). For others, decisions depended on contingencies such as test results to determine ART feasibility or resolution of financial barriers (e.g., receipt of grant funds). Most expected to have a biologically-related child using ART and plans to use donated gametes, gestational carrier, or adopt were considered secondary options.

Table 1.

Sample descriptives (N=46).

| Sociodemographic and medical characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | Median | Range | |

| Current age (years) | 31.6 (3.4) | 31 | 23 – 38 |

| Age of most recent diagnosis (years) | 25.8 (1.3) | 26 | 1 – 37 |

| Age finished most recent treatment (years) | 26.9 (1.3) | 28 | 1 – 37 |

| Time since most recent treatment (years)1 Diagnosed in childhood (<15 years old), n=5 |

5.4 (6.1) | 3.8 | .46 – 29.0 |

| n | % | ||

| Female | 37 | 80 | |

| Diagnosis (first cancer) | |||

| Breast | 15 | 32.6 | |

| Gynecologic (ovarian, cervical, and uterine cancers) | 8 | 17.0 | |

| Lymphoma | 7 | 15.2 | |

| Anal, rectal, colon, colorectal | 4 | 8.7 | |

| Testicular | 3 | 6.5 | |

| Leukemia | 2 | 4.3 | |

| Bone | 2 | 4.3 | |

| Brain | 2 | 2.2 | |

| Ewing’s Sarcoma | 1 | 2.2 | |

| Wilms Tumor | 1 | 2.2 | |

| 1 | |||

| Recurrence or secondary primary cancer (≥2 cancer diagnoses) | 7 | 15.2 | |

| Health insurance± | |||

| Yes, employer-based | 25 | 54.4 | |

| Yes, privately-funded | 5 | 10.8 | |

| Yes, publicly-funded (e.g., Medicaid) | 3 | 6.5 | |

| Relationship status | |||

| Married/partnered | 38 | 82.6 | |

| Children± | |||

| 0 | 34 | 73.9 | |

| ≥1 | 10 | 21.7 | |

| Geographic region | |||

| South | 19 | 41.3 | |

| West | 9 | 19.6 | |

| Midwest | 9 | 19.6 | |

| Mid-Atlantic | 7 | 15.2 | |

| New England | 2 | 4.3 | |

| Family-building± | |||

| Pregnancy via ART | 11 | 23.9 | |

| Pregnancy via ART with donated gametes | 5 | 10.9 | |

| Surrogacy with own gametes | 8 | 17.4 | |

| Surrogacy with donated gametes | 2 | 4.3 | |

| Adoption | 7 | 15.2 | |

| Fertility preservation (for future family-building) | 1 | 2.3 | |

| Undecided2 | 8 | 17.4 | |

| Financial Information (USD) | |||

| M (SD) | Median | range | |

| Annual income (household total) | $51,342 ($28,605) | $49,402 | $0 – $112,656 |

| Total amount of assets | $42,139 ($55,549) | $19,708 | -$27,000 – $196,471 |

| Total amount of liquid assets | $9,176 ($13,627) | $3745 | $0 – $55,000 |

| Total liabilities | $137,083 ($127,092) | $103,035 | $0 – $417,000 |

| Total liabilities excluding mortgage and student loan | $16,183 ($36,016) | $5,080 | $0 – $183,500 |

| Debt subgroups: | |||

| Medical debt (n=24; 52%) | $3,773 ($7,672) | $1,019 | $300 – $28,394 |

| Credit card debt (n=32; 70%) | $10,020 ($14,441) | $4,400 | $200 – $58,000 |

| Student loan debt (n=15; 33%) | $38,508 ($46,891) | $30,000 | $3,000 – $177,000 |

| Bank loans (n=8; 17%) | $34,663 ($58,323) | $14,500 | $1,000 – $176,000 |

| Assets to liabilities ratio | 1.12 (2.9) | .07 | 0 – 14.4 |

| Monthly income | $4279 ($2384) | $4117 | $0 – $9,388 |

| Monthly expenses | $3154 ($1798) | $2960 | $0 – $7,854 |

| Medical expenses (per month) | $297 ($744) | $82.50 | $0 – $4,010 |

| Income to expense ratio | 1.2 (.50) | 1.1 | 0 – 2.1 |

Variable includes missing data; percentages calculated based on full sample size. Health insurance data only collected since 2014.

Excluding hormone therapy (e.g., tamoxifen for breast cancer survivors) and long-term targeted therapy (e.g., Gleevec or Herceptin).

Participants were considering more than one option with most indicating a plan to start with IVF to achieve pregnancy in which they would progress to IVF with donated gametes if initial IVF failed; 6 mentioned adoption as a final attempt for family building and 1 mentioned foster care.

Participants reported an average household income of $51,342 (SD=$28,605; range: $0–112,656) with average liabilities of $137,083 (SD=$127,092; range: $0–417,000). Debt was common and 76% reported credit card debt (M=$10,020, SD=$14,441; range: $200–58,000), 52% had medical debt (M=$3,773, SD=$7,672; range: $300–28,394), and 33% had student loan debt (M=$38,508, SD=$46,891; range: $3,000–177,000). The average income-to-expense ratio was 1.2 (SD=0.50), indicating that participants’ monthly income was slightly greater than their monthly expenses. For reference, The Samfund overall applicant pool reported an income-to-expense of 0.88, indicating monthly expenses that exceeded monthly incomes.17 Most survivors had employer-based (54%) or privately-funded (11%) insurance.

Qualitative Findings

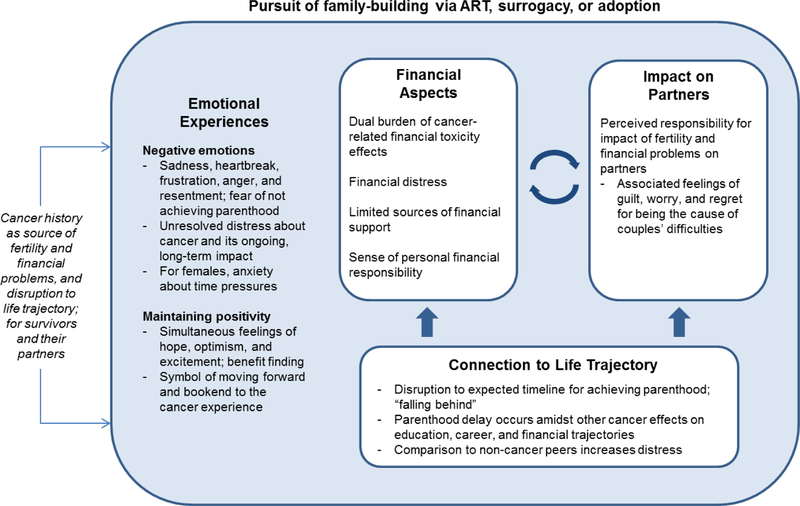

Overall, four major themes were identified: Emotional Experiences of Family-Building after Cancer, Financial Aspects of Family-Building After Cancer, Impact on Partners, and Connection to Life Trajectory. Themes are depicted in Figure 2, with definitions and sample quotes in Table 2. Survivors’ emotional experiences suggested a complex interplay between negative reactions to family-building and financial challenges, with efforts to maintain positivity. Negative emotions associated with (risk of) infertility, family-building, and financial issues were discussed with greater emotional salience than positive emotions, and were underlying factors across all themes identified. The perceived impact of fertility and financial problems on partners was additionally distressing, as was the connection of parenthood to broader life plans, which required couples to accept delays in their expected timeline for parenthood. Themes did not vary by age at diagnosis, current age, or nulliparity; however, those with more negative financial indicators (lower income, greater debt) were more likely to endorse Financial Aspects of Family-Building After Cancer subthemes (p’s<.05). We aimed to describe these independent, yet interconnected factors characterizing family-building processes to better understand survivors’ challenges.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework for the dimensions of young adult cancer survivors’ experiences pursuing family-building via ART or adoption.

Table 2.

Qualitative themes of family-building experiences after cancer.

| Themes | Subthemes (% reported) |

Definition | Sample quotes± |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional experiences of family-building after cancer | Negative emotions (63%) | - Concept of loss (or threat of loss) and subsequent feelings of stress, anxiety, sadness, devastation, hopelessness, and exhaustion - Uncertainty and fear that parenthood will be unachievable - For females, anxiety about reproductive time pressures associated with advancing age and/or diminishing ovarian reserve |

“The journey of infertility due to a cancer diagnosis is devastating. It devastates you emotionally, physically, and financially. It is very easy to become discouraged and defeated. It makes you lose faith in so many ways and at times, makes you want to give up on your dreams of having a family.” “I keep thinking about how the fertility doctor said I was very fertile prior to chemotherapy. Cancer DEFINITELY stole something very valuable and priceless from me.” “The five embryos are my only chance to have children” |

| Reframing to maintain positivity (74%) | - Feeling blessed, hopeful, and optimistic - Positive reframe of negative experiences - Finding sources of gratitude; benefit finding |

“We know that in God’s time, we will be blessed with a baby of our own; we just wish that money wasn’t a factor in that blessing. When my leukemia came back for the second time, in my testicle, I was very blessed to have been offered the decision to deposit sperm for a baby later down the road.” “There are considerable frustrations when a decision about your life is taken from you, but [husband] and I also feel thankful that we at least have options to build a family and that we both have our health.” |

|

| Financial barriers to family-building after cancer | Dual burden of cancer-related financial toxicity (89%) | - Direct and indirect financial effects of cancer such as medical debt and forced employment change (reduced income) - Cancer “financial toxicity” effects reduced financial resources to allocate toward family-building costs |

“Cancer has impacted my financial situation significantly. Initially, after treatment from my first diagnosis it became necessary for me to file [for bankruptcy] as I was drowning in medical debt. … The bankruptcy destroyed my credit and any hope I have in financing [family-building] has to be done through my husband, which we’ve maxed out.” “At this point we are trying to pay off our medical debt, student loans, and now adoption debt, so this additional fee will set us back even further and we would probably have to put it on our credit card and gradually pay it off.” |

| Financial distress (90%) | - Stress due to high cost of ART/adoption, amidst financial toxicity effects - Lack of adequate insurance coverage for fertility treatments - Uncertainty about how to use limited financial resources (e.g., ART vs. adoption) |

“There have been times when I have been devastated by the fear that, because of the significant costs associated with fertility treatments and surrogacy, I will never be able to have a family.” “I know not thinking about it doesn’t make it go away but staring at all the expenses fills me with uncontrollable sadness. Some people have debt from gaining an education; some people have debt from maintaining a luxurious new wardrobe. I have no savings because of cancer.” “Although I do have insurance, the remaining co-pays, lab work, genetic testing, egg storage, travel expense, etc. is overwhelming. We have been trying IUIs, IVF, and now my frozen eggs. The financial burden makes an already heart-breaking circumstance that much more stressful and anxiety provoking.” |

|

| Sense of financial responsibility (84%) | - Attempts made to budget, save, and reduce expenses - Ongoing struggle to balance multiple financial pressures - Recognition of financially irresponsible decision-making; perceived as unavoidable - Worry about affording a child once parenthood was achieved |

“The one thing stopping us of course is the thought of it being an irresponsible financial decision on our part. However, is it really a bad decision when the outcome could potentially be a beautiful baby to add to our family? We really can’t decide what the wrong or right answer to that question is.” “The tremendous costs of adoption are very scary. Our teaching income is limited, and I will continue to have medical expenses for the rest of my life. … Having a new baby will be very costly in and of itself. ... We do not want to deplete all of our savings right before adding a new member to our family.” |

|

| Limited financial support (24%) | - Need for greater financial help than family/friends can provide - Reluctance, concern, and guilt with needing to ask family or friends for money or help |

“Trying to find options to help with the financial costs after cancer is like finding a golden needle in a haystack.” “I feel we plan, budget, and adjust lifestyles accordingly, to make every dollar we have stretch as far as it can go. But there are so many days when it’s just not enough.” “I only have a limited amount of sperm, so we have to be smart about our decisions. Unfortunately, we have to pay for each of these procedures up front. We are unable to make payments and our insurances will not contribute either. Luckily, we have been putting back a little bit to help with the costs, but it’s barely a drop in the bucket to what we will have to endure.” |

|

| Impact on partners | (13%) | - Concern about spouses’ emotional well-being through the family-building process - Feeling personally responsible for couples’ fertility and/or financial problems and life disruption - For males, concern about female partners’ need to undergo ART procedures due to their own male-factor fertility problems |

“Cancer demolished any of my original plans for a family. … Grappling with infertility and mourning the loss of the life we had planned was devastating for both my husband and I.” “I often feel guilty that my cancer diagnosis had such an impact on us financially. … While many of our friends are taking vacations, or investing, we are paying old medical bills and saving for our insurance premium, not exactly how we envisioned things.” “Losing my fertility due to chemotherapy was not only devastating because I want children of my own, but also because I felt like I let my wife down. ... Being a mom has always been one of her greatest dreams. Being parents, and creating a child, has always been OUR dream.” |

| Connection to life trajectory | Life disruption and comparison to peers (76%) | “Falling behind” personal expected timeline for achieving parenthood Amidst other cancer-related life disruptions Comparison to peers increased distress about “falling behind” |

“My husband and I were married for six short months when I was diagnosed with stage 3 breast cancer. Being in our mid-thirties, never married before and without children, we were anxious to start a family as soon as possible. Our initial reaction to my diagnosis was ‘what does this mean for our family plans?’. This was actually the first question I asked the oncologist I met with the day I was diagnosed.” “In a sideways manner cancer has also burdened me by coming about during a time that was critical for me to continue my education. This would have helped in securing a higher salary. I was in school to be a nurse; instead I’m still a secretary.” “Parenthood has been a long-time dream of ours. We have being trying to conceive for over 6 years. It has been a difficult and emotionally and financially draining journey. … My wife and I have seen all of our friends and relatives move on with their lives and start a family while we seem to be stuck in this hole called infertility.” |

Some quotes were double coded and represent more than one theme/subtheme.

Emotional Experiences of Family-building after Cancer

The majority of survivors indicated intense negative emotions surrounding family-building difficulties. These included emotions stemming from the ups and downs of going through ART and adoption, as well as an underlying uncertainty and fear that the opportunity to have a child could be missed. Feelings of sadness, heartbreak, frustration, anger, and resentment were common, and depictions of cancer having “robbed” or “stolen” a natural right of parenthood was often used. Survivors were particularly distressed by the unexpected long-term nature of cancer effects and referenced the injustice of both the cancer diagnosis and effects on fertility. The emotional impact of long-term cancer effects also included survivors’ reactions to financial effects (see Financial Distress).

For some, prolonged difficulties in the family-building process were experienced as a second wave trauma after cancer. There was a sense of shock and outrage, related to learning about gonadotoxic treatment effects. Notably, having successfully frozen gametes prior to cancer treatment did not alleviate anxiety about whether parenthood would eventually be achieved. Females described frozen eggs/embryos as quantified representations of their parenthood potential, which led to complex feelings of anxiety and hope. Females also described negative emotions stemming from a perceived reproductive time pressure. Factors such as advancing age, knowledge of pre-existing fertility problems, and knowledge about the extent of gonadotoxic treatment effects contributed to pregnancy-related distress. Fears about reproductive potential (or lack thereof) were common among females and several referenced their “biological clocks.”

Amidst these challenges, survivors simultaneously expressed some degree of hope, optimism, and excitement. Positive emotions were described as a means of coping with or adjusting to family-building challenges and unresolved grief about cancer. There appeared to be deliberate efforts to reframe negative experiences to maintain positivity. Survivors described sources of gratitude (e.g., “thankful for our health”) and sentiments of hope. Some also took solace in viewing family-building as a “symbol of moving forward,” beyond cancer. While fertility and family-building difficulties were seen as yet another frustrating, disheartening step in the cancer journey, the hope of one day having a child was expected to be a positive bookend to cancer. Having children represented a return to former life plans, which was connected to hope that parenthood would be achieved and to a perceived notion that cancer could then be relegated to the past.

In discussing hope about parenthood, the importance of having children and a determination to do so was emphasized, sometimes depicting long-held childhood dreams of one day becoming mothers/fathers. At times, there was a fine line between dreaming of future parenthood as a source for positivity and these same desires being the cause of anxiety and distress. For example, one survivor felt empowered by ART options, but also described motherhood as “crucial to [her] existence” and referenced her biological ticking clock, hinting at underlying anxiety. Others similarly appeared to be struggling to remain hopeful in the face of uncertainty and family-building difficulty, or referenced dwindling hope, giving insight into potential temporal changes in emotional experiences as survivors navigate ART/adoption.

Financial Barriers to Family-Building After Cancer

The costs of family-building via ART and adoption were described as “suffocating and outrageous,” despite insurance status. Survivors often faced costs that were unexpected, such as additional IVF cycles after failed attempts, pregnancy-related healthcare and medical emergencies (for the survivor/partner or surrogate), escalating legal expenses, and unplanned travel for surrogacy and adoption. Survivors indicated varying degrees of financial planning, but the full extent of accumulated costs often exceeded their expectations..

Financial stress of family-building was exacerbated by cancer-related financial toxicity. Direct and indirect financial effects included the depletion of savings and assets to cover cancer care, medical and credit card debt, high costs of survivorship care and surveillance tests, and reduced work and income due to ongoing side effects (e.g., fatigue or pain). This put survivors in “catch-up mode.” Resources that could otherwise be allocated to family-building funds were instead used for cancer-related healthcare needs and paying off debt. For some, unexpected cancer-related medical emergencies drained savings initially allocated for ART/adoption payments.

Survivors cited multiple competing financial pressures and reported that family-building added to this stress, especially given the emotional significance of parenthood goals. Many of the YAs had tuition costs, school loans, and early career entry-level salaries. Survivors struggled with balancing family-building desires with their ability to pay for ART/adoption costs amidst other financial pressures. As one survivor stated, “We regularly lose sleep planning for how we can maintain our dream to have a child and pay for this family making process.”

Survivors felt discouraged, overwhelmed, defeated, and exhausted from managing their combined financial burdens, and described feelings of stress, anger, anxiety, sadness, and hopelessness related to their financial outlook. Many survivors described feeling anxious and fearful that financial barriers would prevent parenthood.

Uncertainty about where to focus limited financial resources contributed to distress. For example, some survivors struggled with decisions about whether to attempt another IVF cycle after initial failure or to invest that money in adoption. Those with frozen gametes were particularly determined to persist with ART options, even after experiencing initial failures and despite mounting debt. One woman referenced her “frozen babies” and a refusal to “abandon them,” providing insight into the emotional sequelae of fertility preservation and what that might mean for survivors’ post-treatment experiences and decision-making.

For females, perceived reproductive time pressures increased anxiety when pregnancy was the goal, which increased pressure to accumulate financial resources. Survivors felt unable to postpone family-building in order to save money and justified accumulating debt. For others, time pressures stemmed from the need for cancer-related medical procedures that would impact reproductive viability. For example, one survivor’s oncologist had told her to “get pregnant as soon as possible,” as she was recommended to have a prophylactic hysterectomy. She described feeling extremely anxious about postponing childbearing as she would also be delaying recommended care, but did not have the money for ART. Another survivor feared “the next cancer event” and felt a time pressure to freeze her eggs for future use with similar anxieties about taking time to save money.

Predictably, financial distress was due in part to survivors having limited outside resources for financial support. This contributed to a sense of emotional fatigue and a reliance on loans and credit cards, sometimes with evidence of long-term financial risk. One survivor described “maxing out” her credit cards as well as her mother’s credit cards to pay ART bills. Others attempted to cover costs through fundraising events or ad hoc strategies such as garage sales. Survivors were grateful for support from loved ones in the form of monetary gifts, loans, or free housing, but it did not fully alleviate financial stress and at times increased distress. Guilt about needing to ask for help tempered feelings of relief and led to frustration, anger, and shame.

Despite a lack of financial resources and support, most participants indicated some level of commitment to being financially responsible. Survivors tried their best to save money and described “working extremely hard,” “diligently saving,” and employing multiple strategies to cover ART/adoption costs. At the same time, however, they struggled with integrating their preconceived ideas of financial responsibility into family-building decisions. The financial burden of family-building was seen as unavoidable, effectuated by an unfair diagnosis and unjust insurance policies, and for some, justified financially risky decisions such as accruing large debt. The chance to achieve parenthood outweighed the financial burden and was seen as “worth it.” Although survivors acknowledged that this necessitated financial decisions they previously would have viewed as irresponsible, there was no indication of regret. More so, survivors described a determination to not let finances be a barrier to parenthood. Achieving parenthood was the first priority. In the wake of such decisions, some worried about being able to afford a child once parenthood was achieved.

Impact on Partners

The perceived impact fertility and financial challenges had on partners was another source of distress among a subset of participants. Survivors described feeling personally responsible for the couples’ problems and expressed guilt, worry, and regret about burdening their partners. Distress stemmed from the entirety of cancer, fertility, and financial problems, including distress about failing to meet or falling behind their joint expectations for life achievements. One female referenced her husband’s long-held dreams for fatherhood and worried she would be the cause of him being unable to experience being a parent. One male survivor reported guilt for being the cause of his female partner undergoing ART procedures due to his cancer history and uncertainty about achieving parenthood. Notably, a few survivors discussed how facing family-building difficulties had brought the couple closer together, but these depictions also referenced concern and self-blame about the impact on partners.

Connection to Life Trajectory

Many survivors connected family-building difficulties to expected timelines and achievement of broader life plans and goals. Feelings of grief, anger, and resentment about cancer-related life disruptions as a whole were the backdrop of survivors’ distress about parenthood delays. Cancer had not been “a part of the plan,” and many survivors were simultaneously adjusting to derailment from educational pursuits or careers, and achieving financial solvency in adulthood. They were frustrated, saddened by, and angry that cancer was causing such pervasive problems across multiple areas of their lives, particularly when compared to their non-cancer peers. Survivors also found themselves failing to meet societal expectations and markers of success broadly and described being highly attuned to expected timelines for having children. They compared themselves to peers who were becoming parents, as well as greater career advancement and financial success. One survivor described feeling frustrated and bitter that her financial resources were drained by cancer and fertility expenses, while friends had disposable income to take vacations and go shopping. Feelings of “falling behind” were difficult to accept and added significantly to distress related to ART/adoption difficulties.

Discussion

This study adds to limited research evaluating YA cancer survivors’ experiences pursuing family-building via ART, surrogacy, and adoption. The use of real-world evidence and patient-powered data offers a unique perspective of what family-building after cancer may look like for a subset of survivors seeking financial assistance.23 Family-building included significant psychosocial and financial difficulties. Survivors struggled to manage uncertainty and remain hopeful that parenthood would be achieved, while managing the aftermath of their cancer experience and adjusting to the reality of long-term cancer effects. Although some described a determination to focus on positive aspects of their situation, the challenges were discussed with greater emotional significance and were connected to broader questions about what life would look like after cancer.

Participants included primarily female YAs applying to a non-profit organization for financial assistance to help cover costs of ART, surrogacy, and adoption. This real-world exploration of family-building after cancer provides a unique perspective that may be informative and hypothesis generating.23 In this study, the financial burden of family-building came as a surprise to many survivors and was exacerbated by unexpected cancer-related costs, medical emergencies, medical debt, and other financial pressures typical of this age such as student loan repayment. Prior studies have described survivors’ concerns about pregnancy costs and financial stability as potential barriers to future parenthood.24 Difficulties achieving pregnancy after cancer and an unfulfilled desire to have children have also been related to worse mental health.8,10 This study extends this work to better understand the ways in which financial aspects of family-building after cancer play out for survivors that need to pursue ART, surrogacy, or adoption to achieve parenthood.

Further examination of themes within a larger study design is needed. Findings suggest, however, that follow-up fertility counseling, in conjunction with financial guidance, early in post-treatment survivorship is warranted. This is consistent with a recent systematic review, which concluded that fertility and parenthood topics need to be integrated into post-treatment survivorship care.25 Irrespective of financial well-being, offering the opportunity to discuss parenthood options to interested patients could improve referrals to specialists and informational resources, and could allow more time for financial planning. For females, providing information about reproductive timeline, combined with a discussion of parenthood goals and priorities, may be an important step.26 With respect to ART, information about success rates and costs is critical to increase awareness of the potential challenges. Difficulties with adoption, including high costs and stigma, have also been reported by cancer survivors.27,28 Informational resources should be tailored to specific family-building options, particularly as ART and adoption policies vary across the U.S. and internationally. Support resources utilizing evidence-based strategies may help survivors manage negative emotions, make decisions, and plan for potential psychological, logistical, and financial difficulties ahead. More difficult clinical scenarios may involve helping patients with late-stage or recurrent disease cope with emotions and make decisions about frozen gametes, embryos, or tissue, as needed, including consideration of legal and ethical guidelines; or decisions about unused frozen gametes/embryos/tissue. The laws regulating ART and adoption also vary by geographic location, highlighting the confusion that may exist for patients and need for targeted services.

Research is also needed to better characterize survivors’ financial literacy and interest in financial planning support. Notably, 65% of the survivors in this study had health insurance through an employer or privately-funded, yet still experienced significant financial burden. Rather than being a discrete affordable/not affordable decision, patients face complex risk/benefit trade-offs about where to spend resources, whether to incur debt, and if so, how much. As seen in this study, decisions often need to be re-evaluated if treatments fail or other setbacks occur – all of which may happen amidst a racing “biological clock.”29 Low health cost literacy is associated with patients being unprepared for bills, making uninformed treatment decisions, and being unable to access financial support resources.30 Survivors reported wanting financial issues to be included in fertility preservation discussions.31 Decision support interventions have improved fertility decision-making, but appear limited in addressing financial topics.32,33 It may be that intervention modules to support financial literacy and individualized financial planning would benefit survivors in need.

A better understanding of how these factors evolve for females versus males and among couples will also inform targeted approaches to support. Evidence suggests female survivors have greater unmet information needs and report more negative emotions, compared to males.34,35 However, less research has focused on male fertility distress post-treatment compared to female experiences. Gorman et al. developed measures of male and female reproductive concerns after cancer and it is clear that both genders report concerns.36,37 Our findings support this as males struggled with uncertainty about achieving fatherhood and felt responsible for being the cause of couples’ fertility and/or financial problems and for female partners needing to undergo invasive ART procedures. Other work has demonstrated differences in oncofertility care for sexual and gender identity minorities.38 Further examination of the temporal differences and preceding factors that lead to heightened distress for survivor subgroups and how to best provide individualized support is warranted.

Study Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. Data were collected from The Samfund grant applications. While this allowed for a unique, real-world evaluation of what family-building after cancer can look like, there was no opportunity to probe responses to enhance the data. Applications spanned a nine year time period in which public discussion of reproductive health issues and medical options to address infertility has increased in the U.S., particularly around non-medical egg freezing and insurance coverage.39 Although we did not observe a variation in themes based on year of submission, research should explore how sociocultural factors impact survivors’ awareness, expectations, and experiences. The sample was comprised of primarily females who received family-building financial support, which limits the generalizability of findings. Survivors may have overstated their levels of financial stress in an attempt to make a case for a grant award. On the other hand, applicants are required to demonstrate a family-building plan and financial ability to utilize the grant within six months and cover the remaining costs. As such, they may have been further along in their planning, particularly with respect to financial planning, and more optimistic about their ability to succeed in becoming parents; and data indicate they had more financial resources than the general pool of applicants. Despite these limitations, findings capture an important but understudied source of difficulty for YA cancer survivors at the intersection of fertility, family-building, and finances.

Clinical Implications

There is a well-established need for education about treatment-related infertility risk and fertility preservation for reproductive-aged patients starting cancer treatment.3,4 Consistent with prior calls to action,40 this study highlights the equally important need to address survivors’ challenges post-treatment. For survivors who may be at-risk for fertility or financial problems and wish to become parents after cancer, follow-up counseling about reproductive potential and alternative family-building options, including the practical and financial realities and potential barriers, may be warranted. Early financial planning may help to avoid or mitigate financial stress later on. Themes identified here should be evaluated in larger trials to determine the generalizability of findings with consideration to gender, disease, and fertility-related factors, and in the context of quantitative designs. Better understanding of the family-building and financial support needs of YA survivors may inform the development of targeted, evidence-based patient resources. Findings also support prior research and ethical arguments advocating for mandated insurance coverage for ART in the U.S and are consistent with calls for professional and governmental organizations in other countries to be more transparent about costs.29,41 This is an important debate with significant implications for many YA survivors who hope to be parents.

Conclusion

This study explored the experiences of YA survivors pursuing family-building after cancer, including the financial realities of facing ART/adoption costs and the emotional and psychosocial difficulties of ART/adoption. Themes identified i should be further evaluated in larger trials to determine the generalizability of findings and to inform targeted, evidence-based patient resources.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards: This study was not funded.

Conflict of Interest: Authors Michelle Landwehr and Samantha Watson are employed by The Samfund. Authors Catherine Benedict, Jody-Ann McLeggon, Bridgette Thom, Joanne F. Kelvin, and Jennifer Ford declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Logan S, Perz J, Ussher JM, Peate M, Anazodo A. A systematic review of patient oncofertility support needs in reproductive cancer patients aged 14 to 45 years of age. Psychooncology. 2018; 27(2): 401–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barlevy D, Wangmo T, Elger BS, Ravitsky V. Attitudes, beliefs, and trends regarding adolescent oncofertility discussions: A systematic literature review. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oktay K, Harvey BE, Partridge AH, Quinn GP, Reinecke J, Taylor HS, et al. Fertility preservation in patients with cancer: Asco clinical practice guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018: JCO.2018.78.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coccia PF, Pappo AS, Beaupin L, Borges VF, Borinstein SC, Chugh R, et al. Adolescent and young adult oncology, version 2.2018, nccn clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2018;16(1): 66–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Society of Clinical Oncology. American society of clinical oncology clinical practice survivorship guidelines and adaptations. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silva C, Caramelo O, Almeida-Santos T, Ribeiro Rama AC. Factors associated with ovarian function recovery after chemotherapy for breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horowitz JE. Non-traditional family building planning. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;732: 115–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armuand G, Wettergren L, Rodriguez-Wallberg K, Lampic C. Desire for children, difficulties achieving a pregnancy, and infertility distress 3 to 7 years after cancer diagnosis. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014; 22(10): 2805–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benedict C, Thom B,N. Friedman D, Diotallevi D,M. Pottenger E,J. Raghunathan N, et al. Young adult female cancer survivors’ unmet information needs and reproductive concerns contribute to decisional conflict regarding posttreatment fertility preservation. Cancer. 2016; 122(13): 2101–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawshaw M. Psychosocial oncofertility issues faced by adolescents and young adults over their lifetime: A review of the research. Hum Fertil (Camb). 2013;16(1): 59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inhorn MC, Birenbaum-Carmeli D, Westphal LM, Doyle J, Gleicher N, Meirow D, et al. Medical egg freezing: How cost and lack of insurance cover impact women and their families. Reproductive Biomedicine & Society Online. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Is in vitro fertilization expensive? http://www.reproductivefacts.org/detail.aspx?id=3023. Accessed April 20, 2016.

- 13.Gorman JR, Whitcomb BW, Standridge D, Malcarne VL, Romero SAD, Roberts SA, et al. Adoption consideration and concerns among young adult female cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2016: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz P, Showstack J, Smith JF, Nachtigall RD, Millstein SG, Wing H, et al. Costs of infertility treatment: Results from an 18-month prospective cohort study. Fertility and Sterility. 2011; 95(3): 915–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Connor JM, Kircher SM, de Souza JA. Financial toxicity in cancer care. J Community Support Oncol. 2016;14(3): 101–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gordon LG, Merollini KM, Lowe A, Chan RJ. A systematic review of financial toxicity among cancer survivors: We can’t pay the co-pay. The Patient-Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. 2017: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landwehr MS, Watson SE, Macpherson CF, Novak KA, Johnson RH. The cost of cancer: A retrospective analysis of the financial impact of cancer on young adults. Cancer Medicine. 2016; 5(5): 863–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armuand GM, Rodriguez-Wallberg KA, Wettergren L, Ahlgren J, Enblad G, Hoglund M, et al. Sex differences in fertility-related information received by young adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012; 30(17): 2147–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mersereau JE. To preserve or not to preserve: How difficult is the decision about fertility preservation? Cancer. 2013; 119: 4044–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2016. Atlanta2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thom B, Benedict C, Friedman Danielle N, Kelvin Joanne F. The intersection of financial toxicity and family building in young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2018; 0(0). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peate M, Meiser B, Hickey M, Friedlander M. The fertility-related concerns, needs and preferences of younger women with breast cancer: A systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009(116): 215–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hubbard TE, Paradis R. Real world evidence: A new era for health care innovation. The Network for Excellence in Health Innovation. 2015. https://www.nehi.net/publications/66-real-world-evidence-a-new-era-for-health-care-innovation/view. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorman JR, Bailey S, Pierce JP, Su HI. How do you feel about fertility and parenthood? The voices of young female cancer survivors. 2012;6(2):200–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt R, Richter D, Sender A, Geue K. Motivations for having children after cancer – a systematic review of the literature. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2016;25(1):6–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy D, Orgel E, Termuhlen A, Shannon S, Warren K, Quinn GP. Why healthcare providers should focus on the fertility of aya cancer survivors: It’s not too late! Front Oncol. 2013; 3: 248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gardino SL, Russell AE, Woodruff TK. Adoption after cancer: Adoption agency attitudes and perspectives on the potential to parent post-cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 2010; 156: 153–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quinn GP, Zebrack BJ, Sehovic I, Bowman ML, Vadaparampil ST. Adoption and cancer survivors: Findings from a learning activity for oncology nurses. Cancer. 2015; 121(17): 2993–3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klitzman R. How much is a child worth? Providers’ and patients’ views and responses concerning ethical and policy challenges in paying for art. PLoS One. 2017; 12(2): e0171939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zafar SY, Ubel PA, Tulsky JA, Pollak KI. Cost-related health literacy: A key component of high-quality cancer care. J Oncol Pract. 2015; 11(3): 171–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tam S, Puri N, Stephens D, Mitchell L, Giuliani M, Papadakos J, et al. Improving access to standardized fertility preservation information for older adolescents and young adults with cancer: Using a user-centered approach with young adult patients, survivors, and partners to refine fertility knowledge transfer. J Cancer Educ. 2016; 27: 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peate M, Meiser B, Cheah BC, Saunders C, Butow P, Thewes B, et al. Making hard choices easier: A prospective, multicentre study to assess the efficacy of a fertility-related decision aid in young women with early-stage breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012; 106(6): 1053–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ehrbar V, Urech C, Rochlitz C, Zanetti Dallenbach R, Moffat R, Stiller R, et al. Fertility preservation in young female cancer patients: Development and pilot testing of an online decision aid. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017; 31(10). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armuand GM, Wettergren L, Rodriguez-Wallberg KA, Lampic C. Women more vulnerable than men when facing risk for treatment-induced infertility: A qualitative study of young adults newly diagnosed with cancer. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(2): 243–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benedict C, Shuk E, Ford JS. Fertility issues in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2016; 5(1): 48–57. 4779291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gorman JR, Su I, Hsieh M. Measuring reproductive concerns among young adult male cancer survivors: Preliminary results. Fertility and Sterility. 2017; 108(3, Supplement): e185–e6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorman JR, Su HI, Pierce JP, Roberts SC, Dominick SA, Malcarne VL. A multidimensional scale to measure the reproductive concerns of young adult female cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2014; 8(2): 218–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamargo C, Quinn G, Schabath MB, Vadaparampil ST. The importance of disclosure for sexual minorities in oncofertility cases In: Woodruff TK, Gosiengfiao YC, eds. Pediatric and adolescent oncofertility: Best practices and emerging technologies. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017: 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inhorn MC. The egg freezing revolution? Gender, technology, and fertility preservation in the twenty-first century Emerging trends in the social and behavioral sciences: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy D, Orgel E, Termuhlen A. Why healthcare providers should focus on the fertility of AYA cancer survivors: It’s not too late! Front Oncol. 2013; 3: 248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campo-Engelstein L. For the sake of consistency and fairness: Why insurance companies should cover fertility preservation treatment for iatrogenic infertility. Cancer Treat Res. 2010;156:381–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.