Abstract

Antenatal iron and multiple micronutrient supplementation has been shown in randomized trials to improve birthweight, although mechanisms are unknown. We examined late pregnancy serum erythropoietin (EPO) and cortisol concentrations in relation to maternal micronutrient supplementation and iron status indicators (haemoglobin, serum ferritin, soluble transferrin receptor) in 737 rural Nepalese women to explore evidence of stress or anaemia‐associated hypoxia. A double‐masked randomized control trial was conducted from December 1998 to April 2001 in Sarlahi, Nepal, in which women received vitamin A alone (as control), or with folic acid (FA), FA + iron, FA + iron + zinc and a multiple micronutrient supplement. In a substudy, we collected maternal blood in the first and third trimester for biochemical assessments. Generalized estimating equations linear regression analysis was used to examine treatment group differences. EPO was ∼14–17 mIU mL −1 lower (P < 0.0001) in late pregnancy in groups receiving iron vs. the control group, with no difference in the FA‐only group. Cortisol was 1.3 μg dL −1 lower (P = 0.04) only in the micronutrient supplement group compared with the control group. EPO was most strongly associated with iron status indicators in groups that did not receive iron, and in the non‐iron groups cortisol was positively correlated with EPO (r = 0.15, P < 0.01) and soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR, r = 0.19, P < 0.001). In adjusted analyses, third trimester EPO was associated with a reduction in low birthweight, whereas cortisol was negatively associated with length of gestation and higher risk of preterm birth. Iron and multiple micronutrient supplementation may enhance birth outcomes by reducing mediators of maternal stress and impaired erythropoiesis.

Keywords: micronutrients, erythropoietin, cortisol, pregnancy, Nepal

Introduction

Maternal micronutrient deficiencies are common especially in pregnancy and may be associated with adverse birth outcomes including low birthweight and fetal growth restriction (Christian 2010). Furthermore, maternal anaemia, especially during pregnancy, continues to be a global problem, with 42% of pregnant women being anaemic (haemoglobin, Hb < 11 g dL−1) worldwide (World Health Organization 2008). The most important cause of anaemia during pregnancy is iron deficiency because of factors such as increased fetal demand and increase in maternal blood volume and red cell mass, although physiologic anaemia of pregnancy because of plasma volume expansion is normal. Iron deficiency is also known to be linked to adverse consequences: a recent meta‐analyses of controlled iron supplementation trials found a reduction in iron deficiency anaemia of 66% [Relative Risk (RR) 0.44, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.28, 0.68], consistent with two‐thirds of anaemia being due to iron deficiency, and showed a reduction of 20% in incidence of low birthweight (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.71, 0.90) (Imdad & Bhutta 2012) with iron supplementation. There exists an international policy for iron‐folic acid supplementation during pregnancy for women in the developing world, although programme reach and coverage need improvement. Other nutritional causes of anaemia include vitamin deficiencies of haematinics such as folate and vitamins B12, C and E (Fishman et al. 2000). Currently, a global recommendation for supplementation with multiple micronutrients during pregnancy does not exist.

In rural Nepal, in a randomized controlled trial of micronutrient supplementation, we found iron–folic acid supplementation to improve haematologic status (Christian et al. 2003a), birthweight (Christian et al. 2003b) and early infant mortality (Christian et al. 2003c). In the same trial, antenatal multiple micronutrient supplementation increased birthweight relative to the control by 64 g, but the improvement seen was only marginally higher than that seen with iron–folic acid (Christian et al. 2003b). However, a recent meta‐analysis of 16 trials comparing multiple micronutrients with iron plus folic acid as control has shown a reduction in low birthweight of 14% (pooled risk RR, 0.86; 95% CI 0.81, 0.91) and small‐for‐gestational age of 17% (pooled RR, 0.83, 95% CI 0.73, 0.95) (Ramakrishnan et al. 2012).

During anaemia, hypoxia of iron deficiency may result from impaired erythropoiesis, which may stimulate erythropoietin (EPO) production and may increase cortisol levels (Allen 2001). Cortisol is a stress hormone that is involved in regulating parturition (McLean & Smith 1999) and rises significantly during the third trimester (Sandman et al. 2006). However, excess maternal cortisol may be associated with compromised pregnancy outcomes, including low birthweight, intrauterine growth restriction and preterm birth (McLean & Smith 1999; Allen 2001; Sandman et al. 2006). Women with high corticotropin‐releasing hormone (CRH), the factor that controls cortisol, in early pregnancy have been shown to be at an increased risk of preterm birth (McLean et al. 1995). Recently, small studies have shown an inverse association between maternal cortisol levels and fetal growth and measures at birth (Bolten et al. 2011; Hompes et al. 2012). Other micronutrient deficiencies may also increase maternal stress, but evidence for this is limited. Thus, EPO and cortisol may mediate effects of iron and other micronutrients on maternal and infant outcomes, but few studies have examined these potential mechanisms in the context of micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy.

Our data from a randomized antenatal micronutrient supplementation trial in rural Nepal were used to examine EPO and cortisol concentrations in late pregnancy in relation to supplementation, iron status and birth outcomes.

Key messages.

Biological mechanisms underlying the effects of micronutrients on improved birth size are not well elucidated. We show that antenatal iron and multiple micronutrient supplementation enhanced erythropoiesis and reduced maternal stress during pregnancy, two potential pathways that could influence birth size and gestational duration.

These data combined with evidence from randomized controlled trials reveal the benefit of iron‐folic acid and multiple micronutrient supplementation in pregnancy.

Current policy exists for antenatal iron‐folic acid supplementation in low income settings. Future policy and programs for multiple micronutrient supplement use in pregnancy may also be considered.

Materials and methods

Subjects and design

We conducted a double‐masked cluster randomized trial from December 1998 to the end of April 2001 in the southeastern plains district of Sarlahi, Nepal (Christian et al. 2003b). A population of approximately 200 000 people in 30 village development communities was divided into 426 smaller communities. These smaller communities, called sectors, served as the unit of randomization, which was performed in blocks of five within each village development community by drawing numbered chips from a hat. Approximately 100–150 households were in each unit of randomization. Women who were sterilized, widowed, menopausal or breastfeeding an infant <9 months were excluded given their low likelihood of becoming pregnant during the study enrollment period of about a year. In all, 426 local female workers visited eligible women of reproductive age once every 5 weeks, ascertained menstruation history and administered an hCG‐based urine test to determine pregnancy status among those who reported a missed menstrual cycle in the past 30 days. Women were enrolled into the study to receive supplements based on a positive urine test and their informed consent. Study enrollment took place from January 1999 until February 2000 (Christian et al. 2003b).

A baseline interview obtained the following information: date of the last menstrual period, diet, morbidity and work histories in the previous 7 days, socioeconomic status and reproductive history. Gestational age was calculated using the first day of the last menstrual period obtained at the baseline interview. This was verified alongside prospectively collected data on the menstrual cycle and the date of the positive pregnancy test. Anthropometric evaluation included the following measurements: weight, height and mid‐upper arm circumference.

Pregnant women were assigned to receive one of the five following type of micronutrient supplements based on sector of residence: folic acid (400 μg), folic acid + iron (60 mg), folic acid + iron + zinc (30 mg), folic acid + iron + zinc + other micronutrients (10 μg vitamin D, 10 mg vitamin E, 1.6 mg thiamine, 1.8 mg riboflavin, 20 mg niacin, 2.2 mg vitamin B6, 2.6 μg vitamin B12, 100 mg vitamin C, 65 μg vitamin K, 2 mg Cu, 100 mg Mg), vitamin A (control) (Christian et al. 2003b). All women also received vitamin A, as it was shown to reduce pregnancy‐related maternal mortality by 40% in a previous trial (West et al. 1999). All participants, investigators and staff were blinded throughout the study as the supplements were all visually identical. The supplements were replenished by the distributor who visited the women twice a week. They also monitored adherence and pregnancy outcomes.

A substudy area was selected from a third of study area (nine out of 30 Village Development Committees) in the parent trial (Jiang et al. 2005; Christian et al. 2006) to conduct biochemical studies of micronutrient status. It included 133 of the 426 sectors and was selected to be representative of different geographic and ethnic communities but also have reasonable access via roads and to the field laboratory. In a substudy area, maternal venous blood was collected twice during pregnancy, in the first and third trimester. Samples were drawn in trace‐mineral free test tubes (Vacutainer, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) brought back on ice from the field, and the serum was extracted within hours of blood collection, aliquoted, stored in liquid nitrogen and shipped to the Johns Hopkins University, where it was stored at −80° until it was analysed.

Laboratory analysis

The method for assessing iron status indicators, including Hb, serum ferritin and soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR) had been reported previously (Christian et al. 2003a). Briefly, Hb was assessed using a B‐Hemoglobin Analyzer (HemoCue, Lake Forest, CA, USA). Serum ferritin concentrations were determined using a commercial fluoroimmunometric assay (DELFIA; Perkin Elmer Wallac, Norton, OH, USA). Serum sTfR was measured using a commercial immunoassay kit (Ramco Laboratories, Houston, TX, USA). In addition, we analysed third trimester serum EPO (mIU mL−1) and cortisol (μg dL−1) among 737 women in whom we had both first and third trimester sera, using chemiluminescent immunoassays (Immulite, Siemens Diagnostics, Los Angeles, CA, USA). The inter‐assay coefficients of variation for cortisol and EPO in a pooled serum sample at the low end of the concentration range across 31 assays were 9.1% and 6.1%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

EPO, serum ferritin and sTfR were log‐transformed to normalize distributions. Correlation matrices were developed for EPO, cortisol and iron status indicators within intervention groups and combined among intervention groups. Differences in the third trimester EPO and cortisol by supplementation group were examined using generalized estimating equations (GEE) linear regression analysis with the control group as the reference. The relationship of EPO and cortisol to birth outcomes was also examined in multivariable linear and logistic regression models for continuous (birthweight and gestational age at birth) and dichotomous (low birthweight and preterm birth) outcomes, respectively. In the models for each outcome, supplementation group and gestational age at the time of blood draw were included. The models for each analyte also adjusted for the other. The study received ethical approved by the National Health Research Council of the Ministry of Health, Kathmandu, Nepal, and the Committee for the Human Research at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Results

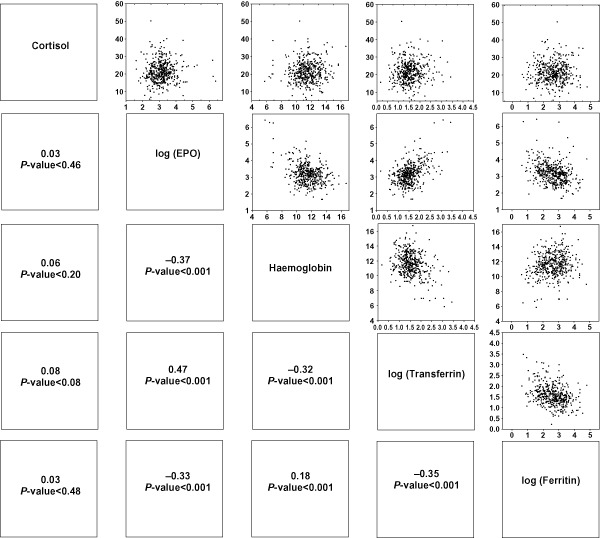

The total number of women in the substudy in whom we analysed late pregnancy cortisol and EPO were those who provided a venous blood sample in both trimesters 1 (early pregnancy, prior to supplementation) and 3 (n = 737) (Fig. 1). Loss to follow‐up was related to refusal to provide consent, migration and fetal loss. The proportion of women who dropped out because of these reasons did not differ by supplement group, with about 120–160 women available for the analysis per group. Mean age at enrolment in the first trimester was about 23 years, and mean weight and height were low (Table 1). Women had low mean concentrations of Hb and iron status indicators in the third trimester, which were improved in the groups having received iron supplementation, as previously shown (Christian et al. 2003a). Mean log EPO and cortisol concentrations in the third trimester are presented by supplement group (Table 1). Circulating concentrations of EPO were significantly lower by about 14–17 mIU mL−1 in each of the groups that included iron in the supplement formulation, unlike in the folic acid group relative to the control (Fig. 2). Cortisol concentrations did not differ in any of the supplement groups, but was marginally lower by 1.32 μg dL−1 (P = 0.062) in the multiple micronutrient supplement relative to the control (Fig. 2). Adjustment for one of the land variable that was different by supplement group did not alter these findings (data not shown). Log EPO was strongly negatively correlated with Hb (r = −0.60, P < 0.001) and ferritin (r = −0.37, P < 0.001) and positively correlated with transferrin receptor (r = 0.71, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3) in the sample of women who did not receive iron, but were somewhat attenuated in those that did (Fig. 4). Serum cortisol concentration was significantly correlated with log EPO and sTfR but not with Hb or serum ferritin concentrations in the groups that did not receive iron (Fig. 3). There was poor or no correlation between cortisol and iron status indicators in the groups which received iron (Fig. 4). In adjusted analyses, EPO was marginally associated with birthweight and significantly associated with a reduction in low birthweight (Table 2). In contrast, each unit increase in cortisol concentration was associated with a small but statistically significant lower gestational age and an elevated risk of preterm birth.

Figure 1.

Study design and number of substudy pregnant women by treatment group and final sample contributing to the erythropoietin and cortisol data and analysis. FA, folic acid; FAFe, folic acid and iron; FAFeZn, folic acid, iron and zinc; MM, multiple micronutrients; TM, trimester.

Table 1.

Characteristics of pregnant women at enrollment, biochemical indicators in late pregnancy and birth outcomes by supplementation group

| Control | FA | FAFe | FAFeZn | MM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 164 | n = 129 | n = 126 | n = 164 | n = 158 | |

| Enrollment (First trimester) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Age, years | 23.2 (5.6) | 23.1 (5.8) | 23.1 (5.5) | 22.8 (5.2) | 23.2 (5.8) |

| Weight, kg | 43.1 (5.7) | 44.4 (5.5) | 44.2 (5.3) | 44.2 (5.5) | 43.7 (5.5) |

| Height, cm | 150.7 (5.8) | 151.8 (6.3) | 150.8 (5.2) | 150.4 (5.4) | 150.7 (5) |

| n (%) | |||||

| Schooling | 41 (25.0) | 39 (30.2) | 35 (27.8) | 50 (30.7) | 34 (21.5) |

| Own land* | 78 (47.6) | 49 (38.0) | 55 (44.0) | 48 (29.3) | 57 (36.1) |

| Parity 0 | 42 (25.6) | 40 (31.0) | 31 (24.6) | 45 (27.4) | 43 (27.2) |

| Third trimester assessment | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Gestational age, week | 32.4 (3.6) | 32.7 (3.5) | 32.6 (4.3) | 32.9 (3.9) | 32.1 (4.1) |

| Hb, g dL−1 | 10.6 (1.6) | 10.3 (1.9) | 11.6 (1.4) | 11.6 (1.4) | 11.4 (1.6) |

| Log ferritin, μg L−1 | 2.13 (0.75) | 1.94 (0.73) | 2.60 (0.72) | 2.60 (0.70) | 2.78 (0.77) |

| Log sTfR, μg mL−1 | 1.90 (0.58) | 2.08 (0.60) | 1.51 (0.39) | 1.58 (0.48) | 1.55 (0.48) |

| Log EPO, mIU mL | 3.66 (0.77) | 3.82 (0.80) | 3.14 (0.57) | 3.19 (0.55) | 3.13 (0.64) |

| Cortisol, μg dL−1 | 21.7 (5.6) | 22.0 (5.1) | 21.6 (6.1) | 21.8 (5.8) | 20.4 (5.7) |

EPO, erythropoietin; FA, folic acid; FAFe, folic acid and iron; FAFeZn, folic acid, iron and zinc; Hb, haemoglobin; MM, multiple micronutrients; sTfR, soluble transferrin receptor. *P < 0.01; Cortisol conversion: μg dL−1 × 27.59 nmol L−1.

Figure 2.

Differences (95% confidence interval) in log erythropoietin (EPO) and cortisol concentrations in the intervention groups relative to the control. Differences estimated using generalized estimating equations linear regression models.

Figure 3.

Correlation matrices showing correlation coefficients and P‐values for log erythropoietin (EPO), cortisol and iron status indicators among pregnant women in the intervention groups not containing iron.

Figure 4.

Correlation matrices showing correlation coefficients and P‐values for log erythropoietin (EPO), cortisol and iron status indicators among pregnant women in the intervention groups containing iron.

Table 2.

Adjusted association between cortisol and EPO and birth outcomes

| Outcomes | Birthweight | Gestational age | Low birthweight | Preterm birth | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE), g | P‐value | β (SE), week | P‐value | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Cortisol | 4.2 (3.1) | 0.17 | −0.05 (0.02) | 0.009 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 1.04 (1.00, 1.08) |

| Log EPO | 43.5 (25.9) | 0.09 | 0.10 (0.17) | 0.53 | 0.78 (0.61, 0.98) | 0.93 (0.70, 1.26) |

CI, confidence interval; EPO, erythropoietin; OR, odds ratio. Adjusted for supplement group, gestational age at blood collection and for the other analyte.

Discussion

Our study found that maternal antenatal supplementation with micronutrients in a rural setting in Nepal, where deficiencies are common, influenced biomarkers of erythropoiesis and stress in the third trimester of pregnancy. Our study revealed a significant reduction in EPO because of iron supplementation, indicative of enhanced erythropoiesis which was reflected in significant improvements across all the iron status and haematologic indicators assessed in the original study (Christian et al. 2003a) and in this sample. All supplement combinations containing iron resulted in lower EPO levels in late pregnancy. On the other hand, the supplement containing multiple micronutrients marginally lowered maternal serum cortisol concentrations in the third trimester. Both of the supplement combinations previously showed significant improvements in birthweight in the parent trial (Christian et al. 2003b).

Iron deficiency during pregnancy or in other states results in the stimulation of erythroid progenitor cells by EPO. Although this is well known, only a few human studies have examined EPO concentrations in pregnancy in response to iron supplementation status in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) context. While EPO was strongly correlated with other iron status indicators, its correlation with these vis‐à‐vis supplementation with iron–folic acid alone and with other micronutrients that included haematinics provides additional information regarding the magnitude and variability of change in EPO in response to nutrient supplementation and improved iron status in this unique setting. In pregnancy, specifically, red cell mass is increased unrelated to and regardless of iron deficiency, and a higher amount of EPO than during the non‐pregnancy state is needed for this expansion. Higher EPO in pregnancy may therefore be a marker of adequate red cell mass expansion, which has been linked with improved fetal growth (Rasmussen 2001). In the control group not getting iron, iron deficiency resulting in hypoxia may stimulate a higher amount of EPO. That it did not decline even more with added haematinics in the supplement also indicates that iron deficiency is the predominant cause of anaemia in this setting.

Exposure of the fetus to glucocorticoids in animal experiments can result in impaired fetal growth, and a placental enzyme 11β‐hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase‐2 protects the fetus by converting cortisol to cortisone in maternal circulation (Christian 2010). Limited evidence for the effect of micronutrients on this axis exists, but in addition to iron deficiency‐induced stress (Allen 2001), retinoic acid has been shown to stimulate the production of 11β‐hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase‐2 (Tremblay et al. 1999). We showed multiple micronutrient supplementation to reduce levels of cortisol in maternal circulation in late pregnancy, perhaps explaining the birthweight effect seen in the parent trial and over and above that seen with iron–folic acid supplementation (64 g vs. 37 g) (Christian et al. 2003b). We have also previously observed iron supplementation effects to impact largely the lower tail of the birthweight distribution, whereas the multiple micronutrient supplement moved the entire birthweight distribution to the right (Katz et al. 2006). This finding led us to postulate that the underlying mechanisms by which different combinations of micronutrient supplements influence fetal growth could differ between iron and other micronutrients in the supplement. We posit that the iron effects on birthweight may be mediated via pathways linked to hypoxia of iron deficiency of which EPO is a biomarker, whereas other micronutrients beyond iron that were in the multiple micronutrient supplement may likely increase birthweight (and gestational duration) through reduction in maternal stress as reflected by lower serum cortisol concentration. Although our data are suggestive of this, we cannot rule out an effect of multiple micronutrients on birthweight that may also be due to mitigation of hypoxia‐caused stress because of iron deficiency or anaemia, specifically because iron was also included in the supplement.

We also showed a strong negative correlation of EPO with Hb and ferritin and a positive correlation with sTfR, as is to be expected after months of daily iron supplementation leading to a decreased production of EPO for promotion of Hb synthesis. We also showed that both the measured analytes were linked to birth outcomes in this sample, increasing the biological plausibility of our findings. Cortisol in this sample significantly increased the risk of preterm birth whereas EPO, a biomarker of hypoxia related to iron deficiency, may influence birthweight by improving fetal growth. These data are preliminary, but provide evidence of the role for micronutrients in improving birth outcomes by influencing the two underlying biological causes of low birthweight, viz. preterm birth and fetal growth restriction. As explained above, cortisol may operate via maternal stress, whereas EPO may improve red cell production and blood volume expansion to enhance fetal growth.

Our study's strength includes a randomized design, with a reasonable sample size in which we examined these biomarkers of interest. However, we did not assess the levels of EPO and cortisol in early pregnancy, largely because of resource constraints, although baseline comparability between groups was good. We also did not assess CRH as has been performed in other studies. The role of cortisol and CRH in causing spontaneous preterm birth is considered well established. Although our parent trial did not show a direct impact on preterm birth or improvement in gestational duration with multiple micronutrient supplementation, a small benefit that can only be shown with much larger sample sizes cannot be ruled out, especially given our findings on cortisol and preterm birth.

There is an increasing and urgent need in low‐ and middle‐income countries to improve pregnancy‐related nutrition and improve birth outcomes. Among other interventions, iron and multiple micronutrient supplementation in these settings have been shown to have a significant benefit for birth outcomes and maternal status (Bhutta et al. 2013). Our study reveals that the impact on birthweight with iron as observed in the parent trial (Christian et al. 2003b) may involve modulation of EPO, whereas multiple micronutrient supplementation effects on birthweight may be mediated by reduced cortisol levels. Although not straightforward, these are important mechanisms to unveil to better understand the biological basis and plausibility of effects on public health outcomes with a high global burden, such as low birthweight and preterm birth.

Source

This work was carried out by the Center for Human Nutrition, Department of International Health of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA in collaboration with the National Society for the Prevention of Blindness, Kathmandu, Nepal, under the Micronutrients for Health Cooperative Agreement No. HRN‐A‐00‐97‐00015‐00 and the Global Research Activity Cooperative Agreement No. GHS‐A‐00‐03‐00019‐00 between the Johns Hopkins University and the Office of Health, Infectious Diseases and Nutrition, United States Agency for International Development, Washington, DC, USA and grant 614 (Global Control of Micronutrient Deficiency) from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, WA, USA and the Sight and Life Global Nutrition Research Institute, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Contributions

PC was the principal investigator, conceived the research question, wrote the paper and helped with data analysis; ANB did the lab analysis for EPO and cortisol and assisted with writing the paper; KS supervised lab analysis and edited the paper; LW conducted the data analysis; SLC and SKK were involved in study design, procedures and implementation and edited the paper.

Acknowledgements

In addition to the authors, the following members of the Nepal study team contributed to the design and successful implementation of the study: Keith P. West Jr., Joanne Katz, who served as co‐investigators on the study, along with a dedicated management staff including the field managers, coordinators and supervisors and the data management staff.

Christian, P. , Nanayakkara‐Bind, A. , Schulze, K. , Wu, L. , LeClerq, S. C. , and Khatry, S. K. (2016) Antenatal micronutrient supplementation and third trimester cortisol and erythropoietin concentrations. Matern Child Nutr, 12: 64–73. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12138.

References

- Allen L.H. (2001) Biological mechanisms that might underlie iron's effects on fetal growth and preterm birth. The Journal of Nutrition 131, 581S–589S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta Z.A., Das J.K., Rizvi A., Gaffey M.F., Walker N., Horton S. et al (2013) Evidence‐based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost? Lancet 382, 452–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolten M.I., Wurmser H., Buske‐Kirschbaum A., Papousek M., Pirke K.M. & Hellhammer D. (2011) Cortisol levels in pregnancy as a psychobiological predictor for birth weight. Archives of Women's Mental Health 14, 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian P. (2008) Nutrition and maternal mortality in developing countries In: Handbook of Nutrition and Pregnancy (eds Lammi‐Keefe C.J., Couch S. & Philipson E.), pp. 319–336. Humana Press: Totowa, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Christian P. (2010) Micronutrients, birth weight, and survival. Annual Review of Nutrition 30, 83–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian P., Shrestha J., LeClerq S.C., Khatry S.K., Jiang T., Wagner T. et al (2003a) Supplementation with micronutrients in addition to iron and folic acid does not further improve the hematologic status of pregnant women in rural Nepal. The Journal of Nutrition 133, 3492–3498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian P., Khatry S.K., Katz J., Pradhan E.K., LeClerq S.C., Shrestha S.R. et al (2003b) Effects of alternative maternal micronutrient supplements on low birth weight in rural Nepal: double blind randomized community trial. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 326, 571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian P., West K.P., Khatry S.K., Leclerq S.C., Pradhan E.K., Katz J. et al (2003c) Effects of maternal micronutrient supplementation on fetal loss and infant mortality: a cluster‐randomized trial in Nepal. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 78, 1194–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian P., Jiang T., Khatry S.K., LeClerq S.C., Shrestha S.R. & West K.P. Jr (2006) Antenatal micronutrient supplementation and biochemical indicators of status and sub‐clinical infection in rural Nepal. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 83, 788–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman S., Christian P. & West K.P. Jr (2000) The role of vitamin supplementation in the prevention and treatment of anemia. Public Health Nutrition 3, 125–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hompes T., Vrieze E., Fieuws S., Simons A., Jaspers L., Van Bussel J. et al (2012) The influence of maternal cortisol and emotional state during pregnancy on fetal intrauterine growth. Pediatric Research 72, 305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imdad A. & Bhutta Z.A. (2012) Routine iron/folate supplementation during pregnancy: effect on maternal anaemia and birth outcomes. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 26, 168–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T., Christian P., Khatry S.K., Wu L. & West K.P. Jr (2005) Micronutrient deficiencies in early pregnancy are common, concurrent, and vary by season among rural Nepali women. The Journal of Nutrition 135, 1106–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J., Christian P., Dominici F. & Zeger S.L. (2006) Treatment effects of maternal micronutrient supplementation vary by percentiles of the birth weight distribution in rural Nepal. The Journal of Nutrition 136, 1389–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean M. & Smith R. (1999) Corticotropin‐releasing hormone in human pregnancy and parturition. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 10, 174–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean M., Bisits A., Davies J.J., Woods R., Lowry P.J. & Smith R. (1995) A placental clock controlling the length of human pregnancy. Nature Medicine 1, 460–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan U., Grant F.K., Goldenberg T., Bui V., Imdad A. & Bhutta Z.A. (2012) Effect of multiple micronutrient supplementation on pregnancy and infant outcomes: a systematic review. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 26, 153–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K. (2001) Is there a causal relationship between iron deficiency or iron deficiency anemia and weight at birth, length of gestation and perinatal mortality? The Journal of Nutrition 131, 590S–601S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandman C.A., Glynn L., Schetter C.D., Wadhwa P., Garite T., Chicz‐DeMet A. et al (2006) Elevated maternal cortisol early in pregnancy predicts third trimester levels of placental corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH): priming the placental clock. Peptides 27, 1457–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay J., Hardy D.B., Pereira L.E. & Yang K. (1999) Retinoic acid stimulates the expression of 11beta‐hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 in human choriocarinoma JEG‐3 cells. Biology of Reproduction 60, 541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West K.P. Jr, Katz J., Khatry S.K., LeClerq S.C., Pradhan E.K., Shrestha S.R. et al (1999) Low dose vitamin A or β‐carotene supplementation reduces pregnancy‐related mortality: a double‐masked, cluster randomized prevention trial in Nepal. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 318, 570–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2008) Worldwide Prevalence of Anaemia 1993−2005: WHO Global Database on Anaemia. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]