Abstract

Malnutrition in children under 5 years of age (U5s) is a serious public health problem in low‐ and middle‐income countries including Bangladesh. Improved maternal education can contribute effectively to reduce child malnutrition. We examined the long‐term impact of maternal education on the risk of malnutrition in U5s and quantified the level of education required for the mothers to reduce the risk. We used pooled data from five nationwide demographic and health surveys conducted in 1996–1997, 1999–2000, 2004, 2007 and 2011 in Bangladesh involving 28 941 U5s. A log‐binomial regression model was used to examine the association between maternal education (no education, primary, secondary or more) and malnutrition in children, measured by stunting, underweight and wasting controlling for survey time, maternal age, maternal body mass index, maternal working status, parity, paternal education and wealth quintile. An overall improvement in maternal educational attainment was observed between 1996 and 2011. The prevalence of malnutrition although decreasing was consistently high among children of mothers with lower education compared with those of mothers with higher education. In adjusted models incorporating time effects, children of mothers with secondary or higher education were at lower risk of childhood stunting [risk ratio (RR): 0.86, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.81, 0.89], underweight (RR: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.78, 0.88) and wasting (RR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.74, 0.91) compared with children of mothers with no education. We demonstrated the importance of promoting women's education at least up to the secondary level as a means to tackle malnutrition in Bangladesh.

Keywords: malnutrition, children under 5 years of age, maternal education, Bangladesh

Introduction

A recent report by UNICEF, World Health Organization (WHO) and The World Bank estimated that in 2011, globally, 165 million children under 5 years of age (U5s) were stunted, 101 million were underweight and 52 million were wasted (UNICEF, WHO, The World Bank 2012). The report further stated that the prevalence of underweight and wasting was highest in South Asia compared with other parts of the world and the prevalence of stunting was similar in South Asia and in sub‐Saharan Africa. In 2011, in Bangladesh, an estimated 6 million U5s were suffering from stunting, 5 million were suffering from underweight and 2 million were suffering from wasting (UNICEF 2013). Most countries in East Asia are well on track to achieve the Millennium Development Goal 1 of reducing prevalence of underweight by half, but by 2009 half of the countries in South Asia including Bangladesh had made insufficient or no progress in achieving this (UNICEF 2009).

The association between malnutrition and subsequent poor health and development is well documented in the literature. Malnutrition has been reported to be closely associated with poor cognitive and education performance in children (Grantham‐McGregor et al. 2007). Poor fetal growth or stunting in the first two years of life leads to shorter adult height, lower levels of attained schooling, reduced adult income and decreased offspring birthweight (Victora et al. 2008). Micronutrient malnutrition accompanied by metabolic adaptation in response to nutrition deficiencies in children can increase the risk of later obesity and related chronic diseases (Eckhardt 2006). Low birthweight has been reported to be associated with increased plasma glucose and insulin concentration, later type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance (Hales et al. 1991; Boyko 2000; Mi et al. 2000; Newsome et al. 2003; Bhargava et al. 2004), as well as higher blood pressure (Law & Shiell 1996; Huxley et al. 2000; Lawlor & Smith 2005) and higher risk of ischaemic heart diseases (Huxley et al. 2007). The long‐lasting health effects of childhood malnutrition suggest that it is critical to tackle its onset before critical stages of childhood development are attained.

Previous research has investigated the determinants of malnutrition among U5s. Maternal education has been found to be strongly associated with nutritional outcomes of children (Barrera 1990; Gupta et al. 1991; Lomperis 1991; Victoria et al. 1992; Kassouf & Senauer 1996). Maternal knowledge of the causes of malnutrition and other socioeconomic factors are stronger risk factors than health care availability or health care‐seeking attitudes (Saito et al. 1997). Maternal education is estimated to be responsible for almost 43% of the reduction in malnutrition in children that took place between 1970 and 1995 in developing countries (Smith & Haddad 2000).

Some researchers have differed on the interpretation of a direct effect of maternal education on nutritional outcomes of children. Using data from 22 demographic and health surveys (DHS) from different parts of the developing world, Desai & Alva (1998) concluded that maternal education acts as a proxy for the socioeconomic status of the family and geographic area of residence. Once those factors are controlled for, the effect of maternal education on nutritional outcome of children is greatly attenuated. Another study by Reed et al. (1996) concluded that the effect of maternal education on nutritional outcome of children depends on the socioeconomic position of the family. The effect is positive and significant for families in intermediate positions and weakly positive for families in the best economic positions. Although debate still continues about the direct effect of maternal education on nutritional outcomes in children, most studies have shown that the prevalence of malnutrition is high among children of mothers with no education compared with children of mothers with some education (Emina et al. 2009).

Recent data indicate that women's education is improving in Bangladesh. The adult female literacy rate increased from 25.8% in 1991 to 54.3% in 2011 (Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh 2012). The net enrolment rate in primary level education for girls was close to 100% in 2012 (Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh 2013). These notable improvements in education of the female population in the last two decades would be expected to positively contribute to reducing malnutrition in U5s in the country. Indeed, previous research conducted in Bangladesh has demonstrated a positive association between nutritional outcomes of children and maternal educational attainment (Rayhan & Khan 2006; Mohsena et al. 2010; Jesmin et al. 2011; Siddiqi et al. 2011). However, all these studies relied on a single cross‐sectional dataset conducted at a particular time point. It remains unclear whether improvement of maternal education over time has positively contributed to reducing malnutrition in U5s in Bangladesh. In this study, we aim to investigate the impact of maternal education on nutritional outcome of U5s and quantify the level of education required for the mothers to reduce the risk of malnutrition in children utilizing the five most recent (i.e. 1996–1997, 1999–2000, 2004, 2007 and 2011) nationwide cross‐sectional DHS data in Bangladesh.

Key messages.

We investigated the impact of maternal education on nutritional outcome of children under 5 years of age for the past 15 years (1996 to 2011) in Bangladesh.

We found that over the past 15 years children of mothers with secondary or higher level of education were at lower risk of childhood stunting, underweight and wasting compared with children of mothers with primary education or with no education.

Future policy to tackle malnutrition in Bangladesh may consider promotion of women's education at least up to the secondary level.

Methods

Data sources

We pooled five DHS data conducted in 1996–1997, 1999–2000, 2004, 2007 and 2011 in Bangladesh. The DHS are cross‐sectional nationally representative surveys generally carried out in less‐developed countries. The surveys use a standardized questionnaire to gather basic demographic and health data. Data obtained using a DHS are generally considered to be of very high quality because of careful questionnaire design, training and supervision of interviewers and quality control checks during data processing (Pullum 2008). In Bangladesh, the DHS are conducted under the authority of the National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) and implemented by Mitra and Associates with financial support from the United States Agency for International Development and technical assistance from ICF International (formerly ORC Macro, Macro International Inc. and Institute for Resource Development, Inc.) (NIPORT et al. 2013). The surveys use a two‐stage stratified sampling design with urban/rural stratification in each division of the country (NIPORT et al. 2009, 2013). At the first stage, primary sampling units (PSUs), also known as census enumeration areas, are selected from both urban and rural areas based on probability proportional to enumeration size. At the second stage, households are systematically selected from these PSUs. Reproductive aged women (aged 15–49 years) are interviewed to collect information on child health (vaccination, childhood illness and newborn care), child feeding practices, vitamin supplementation, anthropometry, anaemia, salt iodization among others (The DHS Program 2014).

Variable definitions

We considered three common indicators of child malnutrition: stunting, underweight and wasting as the outcomes for this study. The WHO child growth standard was used to categorize children as stunted, underweight or wasted (WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group 2006). The main predictor was maternal education which was categorized as no education, primary education and secondary or higher education. The other covariates included as potential confounders in the models were paternal education, year of survey, maternal age, maternal body mass index (BMI), maternal working status, number of children ever born and wealth quintile. Paternal education was categorized as for maternal education. Year of survey was considered a categorical covariate with values 1996, 1999, 2004, 2007 and 2011. Maternal age was grouped into three categories: less than 20 years, 20–30 years and 31 years and more. Maternal BMI, calculated as weight in kilogram divided by height in metre squared, was categorized into three groups: underweight mothers (BMI < 18.5 kg m−2), normal‐weight mothers (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg m−2) and overweight mothers (BMI ≥ 25.0 kg m−2) (WHO 2000). In DHS, height and weight data of mothers are collected in kilograms and centimetres, respectively, by trained interviewers (Pullum 2008). We excluded information of BMI of mothers who were pregnant at the time of surveys. Maternal working status was classed into two categories: working mothers and non‐working mothers. Working mothers were those who engaged in any work at the time of the surveys. They could be self‐employed or employed by others. Their type of earnings could be cash, cash and kind, in cash only and not paid at all. Number of children ever born (parity) was grouped into three categories: one child, 2–3 children and 4 or more. Finally, wealth index was classed into quintiles: poorest, poor, middle, rich and richest. In DHS, the wealth index is constructed using data on household assets and utility services as well as information on whether there is a domestic servant in the household and whether the household owns agricultural land (Rutstein & Johnson 2004). The index is genetrated by applying a similar technique (principal component analysis) in all surveys.

Statistical analysis

We summarized socioeconomic characteristics of 28 941 U5s. A trend of the prevalence of stunting, underweight and wasting by maternal educational attainment for the period 1996 to 2011 was shown. A log‐binomial regression model was used to examine the association of maternal education with nutritional outcomes of U5s over time (1996 to 2011). Previous studies have recommended using a log‐binomial model or a Poisson regression model with robust error variance to estimate relative risk when outcomes are common, as opposed to logistic regression model (Barros & Hirakata 2003). In this study, outcomes (stunting, underweight and wasting) were common. Therefore, a log‐binomial regression model was considered as an appropriate choice. We used the difficult option in Stata to overcome the convergence problems in model estimation (Cummings 2009).

To examine whether maternal education was independently associated with child malnutrition, we developed three models for each of the dichotomous outcomes – stunting, underweight and wasting. Model 1 included maternal education and year of survey as covariates to examine the effect of maternal education and time on nutritional outcome of children. Model 2 extended model 1 by including potential confounders such as paternal education, maternal age, maternal BMI, maternal working status, number of children ever born and wealth quintile in addition to maternal education and year of survey. Model 3 included a two‐way interaction between maternal education and year of survey and all the confounders included in model 2. The purpose of model 3 was to check if the effect of maternal education on nutritional outcome of U5s was different across survey years. Risk ratios (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated and statistical significance was determined by examining the P‐value of the Wald test statistic. All analyses include sampling weights based on the DHS design and were conducted using Stata version 12 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Sample characteristics

Half of the 28 941 U5s were females and one‐fifth were aged less than 1 year (Table 1). The proportion of children living in urban areas steadily increased from 9.4% in 1996 to 22.1% in 2011. An improvement in maternal educational attainment was observed during the period 1996 to 2011. The proportion of mothers with secondary or higher education increased from 16.7% in 1996 to 49.3% in 2011. Meanwhile, the proportion of mothers with no education decreased from 55.7% in 1996 to 20.0% in 2011.

Table 1.

Selected background characteristics and prevalence of malnutrition among 28 941 children aged less than 5 years: Bangladesh demographic and health surveys 1996–1997, 1999–2000, 2004, 2007 and 2011

| Characteristics | 1996–1997 (n = 4706) | 1999–2000 (n = 5351) | 2004 (n = 5937) | 2007 (n = 5300) | 2011 (n = 7647) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | Mean (%) | Total | |

| Gender of child | ||||||||||||

| Female | 50.3 | 2353 | 49.3 | 2639 | 49.3 | 2932 | 50.4 | 2628 | 49.2 | 3740 | 49.7 | 14 292 |

| Male | 49.7 | 2353 | 50.7 | 2712 | 50.7 | 3005 | 49.6 | 2672 | 50.8 | 3907 | 50.3 | 14 649 |

| Age of child (in months) | ||||||||||||

| <12 | 20.3 | 943 | 21.0 | 1109 | 19.5 | 1170 | 20.0 | 1049 | 19.5 | 1484 | 20.1 | 5 755 |

| 12–23 | 19.8 | 941 | 21.0 | 1129 | 19.7 | 1169 | 20.5 | 1095 | 18.8 | 1443 | 19.9 | 5 777 |

| 24–35 | 19.6 | 922 | 19.2 | 1036 | 20.0 | 1216 | 20.2 | 1073 | 18.5 | 1441 | 19.5 | 5 688 |

| 36–47 | 20.4 | 959 | 18.5 | 991 | 20.7 | 1216 | 19.4 | 1048 | 22.2 | 1679 | 20.2 | 5 893 |

| 48–59 | 20.0 | 941 | 20.3 | 1086 | 20.1 | 1166 | 19.9 | 1035 | 21.1 | 1600 | 20.3 | 5 828 |

| Maternal education | ||||||||||||

| No education | 55.7 | 2572 | 46.4 | 2385 | 37.5 | 2118 | 26.8 | 1420 | 20.0 | 1449 | 37.3 | 9 944 |

| Primary | 27.6 | 1337 | 29.1 | 1559 | 31.3 | 1868 | 31.6 | 1659 | 30.7 | 2330 | 30.1 | 8 753 |

| Secondary or higher | 16.7 | 797 | 24.4 | 1407 | 31.2 | 1951 | 41.6 | 2219 | 49.3 | 3868 | 32.6 | 10 242 |

| Maternal body mass index (BMI) | ||||||||||||

| Underweight (BMI ≤18.5 kg m−2) | 51.9 | 2233 | 45.4 | 2183 | 38.2 | 2084 | 32.4 | 1610 | 28.5 | 2053 | 38.1 | 10 163 |

| Normal (18.5 ≤ BMI < 25 kg m−2) | 45.5 | 1977 | 50.6 | 2552 | 56.4 | 3146 | 60.0 | 2941 | 60.0 | 4266 | 55.2 | 14 882 |

| Overweight (BMI ≥25 kg m−2) | 2.6 | 115 | 4.0 | 238 | 5.4 | 360 | 7.6 | 455 | 11.5 | 900 | 6.7 | 2068 |

| Maternal working status | ||||||||||||

| Not working | 66.0 | 3126 | 82.5 | 4456 | 82.3 | 4915 | 73.3 | 4036 | 90.9 | 6918 | 79.0 | 23 451 |

| Working | 34.0 | 1578 | 17.5 | 895 | 17.8 | 1022 | 26.7 | 1263 | 9.1 | 729 | 21.0 | 5 487 |

| Paternal education | ||||||||||||

| No education | 46.4 | 2131 | 43.3 | 2176 | 40.1 | 2243 | 35.1 | 1787 | 29.7 | 2141 | 38.9 | 10 478 |

| Primary | 26.5 | 1262 | 25.0 | 1296 | 27.4 | 1622 | 28.0 | 1474 | 29.1 | 2224 | 27.2 | 7 878 |

| Secondary or higher | 27.1 | 1273 | 31.7 | 1800 | 32.5 | 2069 | 36.9 | 2033 | 41.2 | 3276 | 33.9 | 10 451 |

| Residence | ||||||||||||

| Urban | 9.4 | 636 | 16.4 | 1366 | 19.6 | 1771 | 21.0 | 1850 | 22.1 | 2342 | 17.7 | 7 965 |

| Rural | 90.6 | 4070 | 83.6 | 3985 | 80.4 | 4166 | 79.0 | 3450 | 77.9 | 5305 | 82.3 | 20 976 |

| Division | ||||||||||||

| Barisal | 6.5 | 488 | 6.1 | 469 | 6.0 | 656 | 6.4 | 696 | 5.4 | 837 | 6.1 | 3 146 |

| Chittagong | 24.6 | 852 | 22.2 | 1166 | 22.1 | 1302 | 21.8 | 1093 | 22.7 | 1516 | 22.7 | 5 929 |

| Dhaka | 31.3 | 1302 | 31.3 | 1287 | 30.7 | 1294 | 31.8 | 1122 | 31.3 | 1272 | 31.3 | 6 277 |

| Khulna | 10.1 | 465 | 10.4 | 796 | 10.9 | 776 | 9.6 | 630 | 9.4 | 894 | 10.1 | 3 561 |

| Rajshahi | 21.3 | 1063 | 22.7 | 942 | 22.2 | 1129 | 22.0 | 856 | 12.6 | 916 | 20.1 | 4 906 |

| Sylhet | 6.3 | 536 | 7.3 | 691 | 8.2 | 780 | 8.4 | 903 | 7.7 | 1219 | 7.6 | 4 129 |

| Rangpur | 10.9 | 993 | – | 993 | ||||||||

| Household wealth quintile | ||||||||||||

| Poorest | 21.4 | 974 | 25.1 | 1247 | 25.2 | 1353 | 22.4 | 1050 | 23.6 | 1682 | 23.5 | 6 306 |

| Poorer | 23.1 | 1048 | 22.1 | 1106 | 20.6 | 1127 | 21.6 | 1089 | 20.4 | 1489 | 21.6 | 5 859 |

| Middle | 19.4 | 920 | 19.3 | 997 | 19.7 | 1112 | 19.4 | 996 | 19.4 | 1456 | 19.4 | 5 481 |

| Richer | 19.8 | 914 | 17.3 | 919 | 18.1 | 1080 | 18.9 | 991 | 19.1 | 1493 | 18.6 | 5 397 |

| Richest | 16.4 | 850 | 16.2 | 1082 | 16.5 | 1265 | 17.8 | 1174 | 17.5 | 1527 | 16.9 | 5 898 |

| Prevalence of malnutrition | ||||||||||||

| Stunting | 60.0 | 2823 | 51.2 | 2698 | 50.5 | 2951 | 42.9 | 2210 | 41.2 | 3110 | 49.2 | 13 792 |

| Underweight | 52.2 | 2443 | 41.8 | 2203 | 42.4 | 2461 | 40.8 | 2109 | 36.2 | 2738 | 42.7 | 11 954 |

| Wasting | 20.6 | 958 | 12.3 | 656 | 14.6 | 844 | 17.4 | 898 | 15.5 | 1184 | 16.1 | 4 540 |

Trend of maternal education and malnutrition in U5s

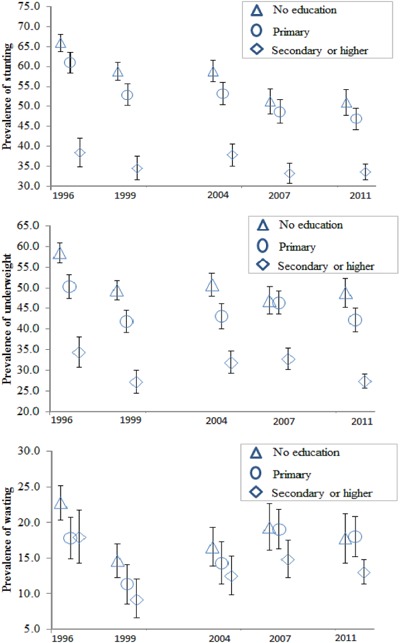

A decreasing trend in the prevalence of stunting, underweight and wasting was observed among U5s during 1996–2011 regardless of maternal educational attainment (Fig. 1). The prevalence of stunting decreased by 15 percentage points (from 66.0% in 1996 to 51.0% in 2011) among children of mothers with no education compared with 4.9 percentage points (from 38.5% in 1996 to 33.6% in 2011) among children of mothers with secondary or higher education. The prevalence of underweight decreased by 9.7 percentage points (58.5% in 1996 to 48.8% in 2011) among children of mothers with no education whereas it decreased by 7.0 percentage points (from 34.3% in 1996 to 27.3% in 2011) among children of mothers with secondary or higher education. The prevalence of wasting did not change much – from 22.8% in 1996 to 17.8% in 2011 among children of mothers with no education and from 17.9% in 1996 to 13.0% in 2011 among children of mothers with secondary or higher education. Overall, the gap in the prevalence of stunting, underweight and wasting by maternal educational attainment narrowed over time.

Figure 1.

Trends in stunting, underweight and wasting by educational attainments of mothers: Bangladesh demographic and health surveys 1996–1997, 1999–2000, 2004, 2007 and 2011.

Association between maternal education and malnutrition in U5s

Multivariate log‐binomial regression results examining the effect of maternal education on the risk of stunting in U5s are presented in Table 2. Model 1 shows that children of mothers with secondary and higher education were at low risk of childhood stunting (RR: 0.63, 95% CI: 0.61, 0.65) compared with children of mothers with no education. However, adjustment for potential confounders (maternal age, maternal BMI, maternal working status, parity, paternal education and wealth quintile) in model 2 reduced the effect size (RR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.81, 0.89) suggesting that the maternal education effect seen in model 1 was partly confounded by these covariates. After including two‐way interaction between maternal education × year of survey in model 3, the protective effects of secondary education of mothers remains apparent for different surveys; however, there is a lack of evidence of significant risk differentials over time between children of mothers with secondary and higher education and children of mothers with no education (P‐value for interaction = 0.818).

Table 2.

Adjusted risk ratios (RRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between maternal education and stunting in children aged less than 5 years, 1996 to 2011

| Covariates | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | |

| Maternal education | |||

| Primary (vs. No education) | 0.91 (0.89 0.94) | 0.99 (0.97 1.03) | 1.01 (0.95 1.07) |

| Secondary (vs. No education) | 0.63 (0.61 0.65) | 0.86 (0.81 0.89) | 0.81 (0.73 0.90) |

| Year of survey | |||

| 1999 (vs. 1996) | 0.88 (0.85 0.92) | 0.87 (0.84 0.91) | 0.88 (0.84 0.92) |

| 2004 (vs. 1996) | 0.89 (0.85 0.94) | 0.89 (0.85 0.94) | 0.90 (0.85 0.95) |

| 2007 (vs. 1996) | 0.80 (0.76 0.84) | 0.79 (0.75 0.83) | 0.78 (0.72 0.84) |

| 2011 (vs. 1996) | 0.79 (0.75 0.83) | 0.79 (0.75 0.83) | 0.78 (0.73 0.84) |

| Maternal education × year of survey | |||

| Primary × 1999 | 0.97 (0.92 1.04) | ||

| Secondary × 1999 | 0.83 (0.76 0.92) | ||

| Primary × 2004 | 0.97 (0.91 1.04) | ||

| Secondary × 2004 | 0.85 (0.79 0.92) | ||

| Primary × 2007 | 1.04 (0.95 1.13) | ||

| Secondary × 2007 | 0.86 (0.77 0.95) | ||

| Primary × 2011 | 1.00 (0.91 1.08) | ||

| Secondary × 2011 | 0.88 (0.81 0.95) | ||

| P‐value for overall interaction effect | 0.818 |

Model 1 is adjusted for maternal education and year of survey. Model 2 is adjusted for maternal education, year of survey, maternal age, maternal BMI, maternal working status, parity, paternal education and wealth quintile. Model 3 is adjusted for all covariates in model 2 plus the interaction between maternal education and year of survey.

Similarly, secondary or higher education has strong protective effects against underweight and wasting in U5s as shown in Tables 3 and 4. In adjusted models (model 2 in Tables 3 and 4), children of mothers with secondary or higher education had lower risks of being underweight (RR: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.78, 0.88) and wasted (RR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.74, 0.91) compared with children of mothers with no education. The interaction effect between maternal education × year of survey in model 3 provided little evidence to conclude that the effect of maternal education in the risk of underweight and wasting in U5s have changed over time (P‐value for overall test of interaction for underweight, P = 0.095; P‐value for overall test of interaction for wasting, P = 0.128).

Table 3.

Adjusted risk ratios (RRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between maternal education and underweight in children aged less than 5 years, 1996 to 2011

| Covariates | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | |

| Maternal education | |||

| Primary (vs. No education) | 0.88 (0.85 0.91) | 0.97 (0.94 1.01) | 0.97 (0.91 1.04) |

| Secondary (vs. No education) | 0.60 (0.57 0.63) | 0.83 (0.78 0.88) | 0.85 (0.75 0.96) |

| Year of survey | |||

| 1999 (vs. 1996) | 0.83 (0.79 0.88) | 0.84 (0.80 0.88) | 0.85 (0.80 0.91) |

| 2004 (vs. 1996) | 0.87 (0.82 0.92) | 0.89 (0.84 0.94) | 0.89 (0.83 0.95) |

| 2007 (vs. 1996) | 0.88 (0.83 0.93) | 0.89 (0.85 0.94) | 0.83 (0.77 0.90) |

| 2011 (vs. 1996) | 0.82 (0.77 0.87) | 0.85 (0.80 0.90) | 0.88 (0.81 0.96) |

| Maternal education × year of survey | |||

| Primary × 1999 | 0.95 (0.87 1.02) | ||

| Secondary × 1999 | 0.79 (0.71 0.89) | ||

| Primary × 2004 | 0.95 (0.88 1.03) | ||

| Secondary × 2004 | 0.85 (0.77 0.94) | ||

| Primary × 2007 | 1.07 (0.97 1.17) | ||

| Secondary × 2007 | 0.95 (0.85 1.06) | ||

| Primary × 2011 | 0.95 (0.86 1.03) | ||

| Secondary × 2011 | 0.75 (0.68 0.83) | ||

| P‐value for overall interaction effect | 0.095 |

Model 1 is adjusted for maternal education and year of survey. Model 2 is adjusted for maternal education, year of survey, maternal age, maternal BMI, maternal working status, parity, paternal education and wealth quintile. Model 3 is adjusted for all covariates in model 2 plus the interaction between maternal education and year of survey.

Table 4.

Adjusted risk ratios (RRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between maternal education and wasting in children aged less than 5 years, 1996 to 2011

| Covariates | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI ) | RR (95% CI) | |

| Maternal education | |||

| Primary (vs. No education) | 0.89 (0.82 0.95) | 0.92 (0.85 1.00) | 0.81 (0.69 0.95) |

| Secondary (vs. No education) | 0.72 (0.67 0.78) | 0.82 (0.74 0.91) | 0.90 (0.74 1.10) |

| Year of survey | |||

| 1999 (vs. 1996) | 0.62 (0.55 0.69) | 0.65 (0.58 0.72) | 0.67 (0.58 0.77) |

| 2004 (vs. 1996) | 0.74 (0.67 0.83) | 0.79 (0.71 0.88) | 0.77 (0.66 0.89) |

| 2007 (vs. 1996) | 0.92 (0.82 1.02) | 0.98 (0.88 1.09) | 0.90 (0.78 1.04) |

| 2011 (vs. 1996) | 0.84 (0.76 0.93) | 0.90 (0.81 1.01) | 0.88 (0.72 1.02) |

| Maternal education × year of survey | |||

| Primary × 1999 | 0.81 (0.67 1.00) | ||

| Secondary × 1999 | 0.73 (0.58 0.92) | ||

| Primary × 2004 | 0.92 (0.77 1.09) | ||

| Secondary × 2004 | 0.85 (0.70 1.03) | ||

| Primary × 2007 | 1.02 (0.86 1.21) | ||

| Secondary × 2007 | 0.86 (0.73 1.05) | ||

| Primary × 2011 | 1.02 (0.86 1.20) | ||

| Secondary × 2011 | 0.81 (0.68 0.97) | ||

| P‐value for overall interaction effect | 0.128 |

Model 1 is adjusted for maternal education and year of survey. Model 2 is adjusted for maternal education, year of survey, maternal age, maternal BMI, maternal working status, parity, paternal education and wealth quintile. Model 3 is adjusted for all covariates in model 2 plus the interaction between maternal education and year of survey.

Discussion

In this study, we utilized a series of cross‐sectional nationally representative DHS data from Bangladesh to assess the contribution of maternal education to reduce childhood malnutrition for a period of 15 years (1996–2011). We observed that higher levels of maternal education are beneficial for better nutritional outcome of U5s. Importantly, our study demonstrates that children of mothers with secondary or higher education had a lower risk of childhood stunting, underweight and wasting compared with children of mothers with no education. This risk differential existed even after controlling for time, maternal age, maternal BMI, maternal working status, parity, paternal education and wealth quintile.

Previous research (Rayhan & Khan 2006; Das et al. 2008) found that primary education of mothers reduced the risk of childhood stunting, underweight and wasting in U5s in Bangladesh. However, our study extends existing knowledge in that we found that it is specifically secondary or higher education of mothers that contributes significantly to reducing the risk of malnutrition in U5s in Bangladesh, after adjusting for other factors related to socioeconomic position. This finding parallels that of Makoka (2013) who showed that a higher level of maternal education significantly reduced the odds of malnutrition in U5s in Malawi, Tanzania and Zimbabwe and that a lower level of education had no impact.

The prevalence of stunting, underweight and wasting were lower among children of mothers with secondary or higher education compared with children of mothers with primary education or with no education in most of the surveys. This pattern of prevalence was also reported in previous research (Rayhan & Khan 2006; Das et al. 2009; Siddiqi et al. 2011). While we could not explore the reason why the prevalence of malnutrition was low in children of educated mothers, studies have indicated that high levels of maternal education is associated with protective childcare behaviours such as vitamin A capsule receipt, complete childhood immunizations, better sanitation and use of iodized salt (Semba et al. 2008). Higher education also gives women a higher level of autonomy, greater decision‐making power in the family regarding health‐related matters and better use of modern health facilities which could lead to better health outcomes of children (Cleland & Van Ginneken 1988; Kishor 1995).

Our findings suggest that long‐term strategies for tackling malnutrition in U5s in Bangladesh must consider extending maternal education beyond primary education. Past studies have indicated various pathways such as socioeconomic status, health knowledge and attitudes towards health care, health and reproductive behaviours and female autonomy, through which maternal education could positively influence nutritional outcome of children (Frost et al. 2005; Emina et al. 2009). Since 1990, the Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh has taken several initiatives to promote women education, such as free education up to higher secondary level, a female stipend programme, providing scholarships to meritorious students, providing financial support to purchase books and paying fees for public examinations (Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh 2012). These initiatives may have positively contributed to achieving gender parity both at primary and secondary level education (Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh 2013). However, until now female participation in secondary or higher level education is low compared with male (Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh 2012). According to the most recent estimates, 15% of the men and 10% of the women completed secondary or higher education in 2011 (NIPORT et al. 2013). Despite the need to improve female participation in the secondary or higher level education, government interventions largely focused on meeting the Millennium Development Goal 2 of achieving universal primary education for all. While it is important to ensure primary education for all, our findings suggest that it is now time to start focusing on improving female participation in secondary or higher level education to reduce the risk of malnutrition in U5s in Bangladesh.

Several strengths and weaknesses of our study should be noted. The main strength is the use of a set of nationally representative DHS data to examine the long‐term impact of maternal education on the nutritional outcomes of U5s. DHS data have been considered for a long time as the gold standard for developing countries (Johnson et al. 2009). However, it should be noted that the DHSs are cross‐sectional, therefore limiting, our ability to describe causal relationships between factors in a regression model. An important strength of our analysis is the inclusion of important potential confounders during the modelling process. However, it is impractical to control for all influencing factors that are associated with nutritional outcome of children.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that secondary or higher education of mothers may have contributed effectively in reducing the risk of malnutrition in U5s in Bangladesh. Future policy to tackle malnutrition in U5s in Bangladesh may emphasize promotion of women's education at least through the secondary level.

Source of funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not‐for‐profit sectors. M.T.H is supported by an International Postgraduate Research Scholarship from the University of Queensland (#43054112).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor statement

MTH and AAM conceived the study. MTH performed data analysis and wrote the first draft. AAM and RJSM contributed to data interpretation and preparation of the manuscript. GMW edited and provided important intellectual feedback.

Acknowledgement

We thank MEASURE DHS for granting permission to use the Bangladesh DHS data.

Hasan, M. T. , Soares Magalhaes, R. J. , Williams, G. M. , and Mamun, A. A. (2016) The role of maternal education in the 15‐year trajectory of malnutrition in children under 5 years of age in Bangladesh. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12: 929–939. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12178.

References

- Barrera A. (1990) The role of maternal schooling and its interaction with public health programs in child health production. Journal of Development Economics 32, 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Barros A.J. & Hirakata V.N. (2003) Alternatives for logistic regression in cross‐sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Medical Research Methodology 3, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava S.K., Sachdev H.S., Fall C.H., Osmond C., Lakshmy R., Barker D.J. et al (2004) Relation of serial changes in childhood body‐mass index to impaired glucose tolerance in young adulthood. New England Journal of Medicine 350, 865–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyko E.J. (2000) Proportion of type 2 diabetes cases resulting from impaired fetal growth. Diabetes Care 23, 1260–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland J.G. & Van Ginneken J.K. (1988) Maternal education and child survival in developing countries: the search for pathways of influence. Social Science and Medicine 27, 1357–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings P. (2009) Methods for estimating adjusted risk ratios. Stata Journal 9, 175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Das S., Hossain M.Z. & Islam M.A. (2008) Predictors of child chronic malnutrition in Bangladesh. Proceedings of Pakistan Academy of Science 45, 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Das S., Hossain M.Z. & Nesa M.K. (2009) Levels and trends in child malnutrition in Bangladesh. Asia‐Pacific Population Journal 24, 51–78. [Google Scholar]

- Desai S. & Alva S. (1998) Maternal education and child health: is there a strong causal relationship? Demography 35, 71–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt C.L. (2006) Micronutrient Malnutrition, Obesity, and Chronic Disease in Countries Undergoing the Nutrition Transition: Potential Links and Program/Policy Implications. International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Emina J.B., Kandala N.B., Inungu J. & Ye Y. (2009). The Effect of Maternal Education on Child Nutritional Status in the Democratic Republic of Congo. 26th International Population Conference, International Union for the Scientific Study of Population (IUSSP): Marrakesh, Morocco. Available at: http://iussp2009.princeton.edu/papers/92718 (Accessed 6 September 2013).

- Frost M.B., Forste R. & Haas D.W. (2005) Maternal education and child nutritional status in Bolivia: finding the links. Social Science and Medicine 60, 395–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh (2012) The Millennium Developments Goals: Bangladesh Progress Report 2011. Bangladesh Planning Commission: Dhaka, Bangladesh. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh (2013) The Millennium Developments Goals: Bangladesh Progress Report 2012. Bangladesh Planning Commission: Dhaka, Bangladesh. [Google Scholar]

- Grantham‐McGregor S., Cheung Y.B., Cueto S., Glewwe P., Richter L. & Strupp B. (2007) Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. The Lancet 369, 60–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta M.C., Mehrotra M., Arora S. & Saran M. (1991) Relation of childhood malnutrition to parental education and mothers' nutrition related KAP. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics 58, 269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales C.N., Barker D.J., Clark P.M., Cox L.J., Fall C., Osmond C. et al (1991) Fetal and infant growth and impaired glucose tolerance at age 64. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 303, 1019–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley R., Owen C.G., Whincup P.H., Cook D.G., Rich‐Edwards J., Smith G.D. et al (2007) Is birth weight a risk factor for ischemic heart disease in later life? American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 85, 1244–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley R.R., Shiell A.W. & Law C.M. (2000) The role of size at birth and postnatal catch‐up growth in determining systolic blood pressure: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Hypertension 18, 815–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesmin A., Yamamoto S.S., Malik A.A. & Haque M.A. (2011) Prevalence and determinants of chronic malnutrition among preschool children: a cross‐sectional study in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition 29, 494–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K., Grant M., Khan S., Moore Z., Armstrong A. & Sa Z. (2009) Fieldwork‐Related Factors And data Quality in the Demographic and Health Surveys Program. ICF Macro International: Calverton, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Kassouf A.L. & Senauer B. (1996) Direct and indirect effects of parental education on malnutrition among children in Brazil: a full income approach. Economic Development and Cultural Change 44, 817–838. [Google Scholar]

- Kishor S. (1995) Autonomy and Egyptian Women: Findings from the 1988 Egypt Demographic and Health Survey (English). Macro International: Calverton, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Law C.M. & Shiell A.W. (1996) Is blood pressure inversely related to birth weight? The strength of evidence from a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Hypertension 14, 935–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor D.A. & Smith G.D. (2005) Early life determinants of adult blood pressure. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension 14, 259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomperis A.M.T. (1991) Teaching mothers to read: evidence from Colombia on the key role of maternal education in preschool child nutritional health. The Journal of Developing Areas 26 (1), 25–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makoka D. (2013) The Impact of Maternal Education on Child Nutrition: Evidence from Malawi, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe. ICF Macro: Calverton, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Mi J., Law C., Zhang K.‐L., Osmond C., Stein C. & Barker D. (2000) Effects of infant birthweight and maternal body mass index in pregnancy on components of the insulin resistance syndrome in China. Annals of Internal Medicine 132, 253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohsena M., Mascie‐Taylor C.G. & Goto R. (2010) Association between socio‐economic status and childhood undernutrition in Bangladesh; a comparison of possession score and poverty index. Public Health Nutrition 13, 1498–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIPORT, Mitra and Associates & ICF International (2013) Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2011. National Institute of Population and Research Training, Mitra and Associates & ICF International: Dhaka, Bangladesh and Maryland, USA.

- NIPORT, Mitra and Associates & Macro International (2009) Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2007. National Institute of Population and Research Training, Mitra and Associates & Macro International: Dhaka, Bangladesh and Maryland, USA.

- Newsome C., Shiell A., Fall C., Phillips D., Shier R. & Law C. (2003) Is birth weight related to later glucose and insulin metabolism? – A systematic review. Diabetic Medicine 20, 339–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullum T.W. (2008) An Assessment of the Quality of Data on Health and Nutrition in the DHS Surveys 1993–2003. Macro International: Calverton, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Rayhan I.M. & Khan M.S.H. (2006) Factors causing malnutrition among under five children in Bangladesh. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 5, 558–562. [Google Scholar]

- Reed B.A., Habicht J.‐P. & Niameogo C. (1996) The effects of maternal education on child nutritional status depend on socio‐environmental conditions. International Journal of Epidemiology 25, 585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutstein S.O. & Johnson K. (2004) The DHS Wealth Index. ORC Macro: Calverton, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Saito K., Korzenik J., Jekel J.F. & Bhattacharji S. (1997) A case‐control study of maternal knowledge of malnutrition and health‐care‐seeking attitudes in rural South India. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 70, 149–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semba R.D., de Pee S., Sun K., Sari M., Akhter N. & Bloem M.W. (2008) Effect of parental formal education on risk of child stunting in Indonesia and Bangladesh: a cross‐sectional study. The Lancet 371, 322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi M.N.A., Haque M.N. & Goni M.A. (2011) Malnutrition of under‐five children: evidence from Bangladesh. Asian Journal of Medical Sciences 2, 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Smith L.C. & Haddad L.J. (2000) Explaining Child Malnutrition in Developing Countries: A Cross‐Country Analysis. International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- The DHS Program (2014) DHS Survey Topics. Available at: http://dhsprogram.com/What-We-Do/Survey-Types/DHS.cfm (Accessed 12 December 2014).

- UNICEF (2009) Tracking Progress on Child and Maternal Nutrition: A Survival and Development Priority. United Nations Children's Fund: New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF (2013) Improving Child Nutrition: The achievable Imperative for Global Progress. United Nations Children's Fund: New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF, WHO, The World Bank (2012) UNICEF‐WHO‐World Bank joint child malnutrition estimates. United Nations Children's Fund: New York, World Health Organization: Geneva, The World Bank: Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Victora C.G., Adair L., Fall C., Hallal P.C., Martorell R., Richter L. et al (2008) Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. The Lancet 371, 340–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victoria C.G., Huttly S.R., Barros F.C., Lombardi C. & Vaughan J.P. (1992) Maternal education in relation to early and late child health outcomes: findings from a Brazilian cohort study. Social Science and Medicine 34, 899–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group (2006) WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/Height‐for‐Age, Weight‐for‐Age, Weight‐for‐Length, WEIGHT‐for‐Height and Body Mass Index‐for Age: Methods and Development. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2000) Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic: Report of a WHO Consultation. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]