Abstract

Interventions to prevent childhood obesity must consider not only how child feeding behaviours are related to child weight status but also which behaviours parents are willing and able to change. This study adapted Trials of Improved Practices (TIPs) to assess acceptability and feasibility of nutrition and parenting recommendations, using in‐depth interviews and household trials to explore families’ experiences over time. A diverse sample of 23 low‐income parents of 3–11‐year‐olds was recruited following participation in nutrition and parenting education. Parents chose nutrition and parenting practices to try at home and were interviewed 2 weeks and 4–6 months later about behaviour change efforts. Qualitative analysis identified emergent themes, and acceptability and feasibility were rated based on parents’ willingness and ability to try new practices. The nutrition goal parents chose most frequently was increasing children's vegetable intake, followed by replacing sweetened beverages with water or milk, and limiting energy‐dense foods. Parents were less inclined to reduce serving sizes. The parenting practices most often selected as applicable to nutrition goals were role‐modelling; shaping home environments, often with other adults; involving children in decisions; and providing positive feedback. Most recommendations were viewed as acceptable by meaningful numbers of parents, many of whom tried and sustained new behaviours. Food preferences, habits and time were common barriers; family resistance or food costs also constrained some parents. Despite challenges, TIPs was successfully adapted to evaluate complex nutrition and parenting practices. Information on parents’ willingness and ability to try practices provides valuable guidance for childhood obesity prevention programmes.

Keywords: behaviour change, child feeding, childhood obesity, parenting, low income, research methodology

Introduction

Evidence suggests that parenting practices and the home environment are strong influences on child eating behaviours and weight (Lindsay et al. 2006). Policies to create community environments that facilitate healthful choices are essential (Schwartz & Brownell 2007; Kumanyika 2008; Institute of Medicine 2011) but still need to be translated into lifestyle behaviours at home. Parents play fundamental roles in shaping home environments and influencing children's choices in the years when lifelong habits develop (Ventura & Birch 2008). Educational programmes can support parents’ efforts to promote healthy eating habits by focusing on the most relevant nutrition goals and also on influential parenting strategies. The design of effective interventions should be based on evidence of not only which behaviours are associated with weight status but also on which behaviours parents are willing and able to change. This second type of evidence must be grounded in parents’ real‐life experiences with child feeding.

Child feeding involves both food‐related practices (e.g. what is purchased, prepared and served) and parenting practices (e.g. how parents interact with, guide and respond to children). Parenting practices are behavioural strategies applicable to multiple situations and are related to parenting styles, broad patterns of attitudes that contribute to the emotional tone of parent–child relationships (Darling & Steinberg 1993). There is a growing literature on the complex interrelationships among parenting and feeding practices and styles, child weight status and dietary intake (Faith et al. 2004; Wardle et al. 2005). Evidence of direct and indirect effects on children is still emerging and sometimes appears contradictory, likely reflecting differences in measurement, population characteristics and statistical modelling of relationships (Hughes et al. 2006; Wardle & Carnell 2007; Joyce & Zimmer‐Gembeck 2009; Hennessy et al. 2010). For programmatic purposes, sufficient evidence exists to recommend that parents aim for a balance of firmness (i.e. setting limits, having high but appropriate expectations) and responsiveness (warmth and attentiveness to children's needs). Although appropriately firm and responsive feeding styles are associated with healthy child weights (Hughes et al. 2005; Patrick et al. 2005), translation of the research into interventions has been limited by the focus on negative behaviours (O'Connor et al. 2010), such as control and restriction (Faith & Kerns 2005). In addition, the cross‐sectional nature of much of the research prevents elucidation of the direction of causality and the degree to which behaviours are modifiable (Bante et al. 2008). Little is known about the acceptability and feasibility of the recommended practices, particularly in low‐income families who face multiple challenges to healthful eating and high risks of childhood obesity (Kumanyika & Grier 2006).

Lack of data on the acceptability and feasibility of food and parenting practices in low‐income families posed a dilemma during the development of ‘Healthy Children, Health Families: Parents making a difference!’ (HCHF). HCHF is a curriculum for an 8‐session series of hands‐on workshops integrating nutrition, active play and parenting education to help low‐income parents of 3–11‐year‐old children prevent unhealthy child weight gain (Lent et al. 2012). The nutrition‐related behaviours promoted in HCHF were selected based on evidence of their relevance for maintaining healthy weights and reducing chronic disease risk (Institute of Medicine 2004; Woodward‐Lopez et al. 2006; Davis et al. 2007; Institute of Medicine 2011). HCHF also covers a set of recommendations for firm and responsive parenting, adapted from parenting education programmes (Bailey et al. 1995; Birckmayer 2001) to complement the nutrition goals by helping parents influence children's habits. Programme developers focused on evidence‐based recommendations, but much of the available research on nutrition and parenting practices was conducted with middle to high income families, leaving gaps in knowledge about feasibility and acceptability of these practices in low‐income families. To guide programme development, in‐depth exploration of the factors influencing behaviour change in families was needed.

In the present study, we adapted a mixed‐methods approach known as Trials of Improved Practices (TIPs) to follow up parents who had participated in HCHF and explore their experiences with new behaviours over 4–6 months. The TIPs methodology was originally developed to test complementary feeding recommendations among mothers of young children in low‐income countries, tallying mothers’ willingness and actual trial of new practices and interviewing mothers on their perceptions of the practices (Dickin et al. 1997). TIPs data on acceptability and feasibility can guide the selection of messages and the development of behaviour change communications. In TIPs, the interviewer works with parents to identify a concern, consider a range of solutions, choose an option, implement the potential solution at home and discuss the results. In some ways, the approach resembles counselling techniques such as motivational interviewing (Resnicow et al. 2006) and problem‐solving therapy (Malouff et al. 2007). At the same time, the research objective is to gain insights that potentially apply to a population segment. Thus, the interviewing approach balances helping parents to make relevant choices with avoiding biasing their responses. The goal is to engage parents as autonomous stakeholders whose opinions and experiences put them in a position to vet programme recommendations for applicability in the context of everyday life.

The current study adapted the TIPs methodology to explore change in complex food‐related behaviours among 3–11‐year‐old children with diverse diets, in contrast to previous applications with infants and toddlers consuming a very limited number of complementary foods. We also adapted TIPs to test parents’ willingness and ability not only to try new food behaviours but also to apply parenting practices to nutrition goals. The usual length of follow‐up (1–2 weeks) was extended to examine sustained practice of recommended behaviours. The intent of the analyses presented here was to illustrate the application of TIPs to examine families’ experiences with widely recommended nutrition and parenting practices, combining categorical coding of responses with qualitative analysis of acceptability and feasibility. Thus, the research objectives were twofold:

to adapt TIPs methodology as a means of assessing acceptability and feasibility of recommended nutrition and parenting practices, and

to explore low‐income parents’ willingness to change, preferences for, and experiences with recommended nutrition and parenting practices and their perceptions of the barriers and facilitators that influence behaviour change in their families.

Key messages

Successful adoption of nutrition and parenting recommendations to improve child feeding depends on parents' views of the acceptability and feasibility of these practices.

Trials of Improved Practices (TIPs) is a useful approach for assessing acceptability and feasibility by exploring how and why parents choose, implement and experience actual trial of recommended practices.

Low‐income parents who are motivated to promote healthy eating at home can successfully implement many currently recommended nutrition and parenting practices but face barriers such as food preferences, habits, time and convenience, as well as constraints related to stressful life circumstances and food insecurity.

Materials and methods

Sampling

Parents were recruited from among participants in HCHF programs delivered by Cornell Cooperative Extension in November 2009–September 2011. We used a two‐stage purposive sampling approach (Patton 1990) to recruit a diverse sample of low‐income families. First, we selected two rural and two urban counties that served populations varying in race and ethnicity. Nutrition educators in each site were informed of the purpose of the study and asked to contact parents who had completed HCHF to ask if they were interested in participating. Programme staff made initial contacts with potential respondents to preserve the confidentiality of programme participants’ data. Educators were asked to invite participants who varied in motivation and response to programme, not just those with positive experiences. Researchers then contacted interested parents by mail, phone or email to provide further information and set up interviews. The pool of programme graduates in these sites for whom educators had current contact information was relatively small so most of those who expressed an interest were included. Final inclusion was based on representation of the range of child ages (3–11 years) covered by HCHF and availability on the dates that interviews were conducted, including expected availability for a follow‐up interview 4–6 months later.

Researchers requested that parents participate in data collection at four time points: an intake survey on background characteristics, followed by three in‐depth interviews related to the selection and trial of new behaviours (Table 1). Recent programme graduates as well as parents who completed the programme several months or a year earlier were included. This was acceptable because the research did not evaluate change resulting from programme participation, but investigated parents’ responses when asked to choose a new practice to change. The reason for recruiting HCHF participants was to reach parents who had already been introduced to the recommended practices of interest. Although practices were reviewed during the interviews (using HCHF programme materials), there was not enough time to teach the parenting practices in sufficient detail to parents who were not familiar with them.

Table 1.

Overview of data collection time points in adapted Trials of Improved Practices methodology

| Intake (day 1) | T1 interview (day 2) | T2 interview (2 weeks) | T3 interview (4–6 months) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Background characteristics | What would you like to try to change? | Did you try? How did it go? | Did you continue? |

|

|

|

|

BMI, body mass index.

Parents selected one of their children aged 3–11 years on whom to focus when answering questions. Parents were compensated 20, 25, 30 and 40 dollars, respectively, across the four time points. Interviews were conducted in participants’ homes (n = 13) or in a private room in a familiar location, usually a church or school (n = 10). One follow‐up interview was conducted by phone and one parent was lost to follow‐up and did not complete the final interview. Protocols were approved by the Cornell University Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Recommended practices

The TIPs interviews focused on responses to nutrition and parenting recommendations covered in HCHF workshops. HCHF promotes four broad nutrition goals (and two goals related to physical activity that were not addressed in this study). These goals, common to many evidence‐based nutrition interventions, include (1) eating more vegetables and fruits; (2) drinking water and low‐fat dairy instead of sugar‐sweetened beverages (SSBs); (3) limiting high‐fat, high‐sugar foods (energy‐dense foods or EDFs); and (4) eating appropriate amounts by ‘having sensible servings’ or eating just enough to satisfy hunger. Within any of these broad nutrition goals, there are multiple options of what HCHF refers to as ‘healthy steps’ that parents can try at home. Examples of specific steps towards the goals are discussed in the programme and parents are encouraged to choose the particular foods, preparations and other changes that fit their family context. Reflecting self‐determination theory (Deci & Ryan 1985), this approach works from the premise that allowing parents to make choices within an array of health‐promoting options will enhance motivation. Likewise in TIPs, parents chose a broad goal and then focused on specific changes to try, tailoring their selections to their own family context.

In addition, HCHF covers four clusters of parenting practices relevant to positive family interactions and promotion of healthful eating: (1) teaching by example; (2) supportive interactions; (3) offering choices within limits; and (4) creating home environments that make healthy choices easier. Each cluster comprises one to four specific practices presented to parents as strategies to help children make progress towards nutrition goals. Similarly in TIPs, parents first chose a nutrition goal and then selected parenting practices to apply to that goal. Table 2 summarises the parenting practices covered, based on HCHF descriptions.

Table 2.

Clusters, labels and explanations of parenting practices assessed. From Healthy Children, Healthy Families: Parents making a difference! curriculum (Lent et al. 2012)

| Cluster | Specific parenting practices |

|---|---|

| Showing: Teach by example |

|

| Supporting: Help children feel good about themselves |

|

| Guiding: Offer choices within limits |

|

| Shaping: Make healthy choices easier |

|

Surveys

At intake, participants completed questionnaires on demographic characteristics (parent's race/ethnicity, marital status, education, employment, rural or urban residence, household size, and parent and child age and gender); weight concerns and perceptions; and food security. Food security over the prior 12 months was assessed with the 18‐item US Household Food Security Survey Module, which has been shown to be valid and consistent across diverse populations (Bickel et al. 2000; Economic Research Service 2012). Two items from the Child Feeding Questionnaire (Birch et al. 2001) assessed (on a 5‐point scale) parental concerns that the child would become overweight in the future or would eat too much when the parent was not around. Parents also rated the child as very underweight, underweight, normal weight, overweight or very overweight. Parent and child heights and weights were measured in duplicate and converted to body mass index (BMI, kg m−2) and for children, to BMI percentile for age and sex, using ANTHRO software (version 1.02, Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, GA, USA). Survey and BMI data were descriptively analysed (Stata/IC 10.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) to characterise the sample.

Trials of Improved Practices (TIPs)

The TIPs methodology is primarily qualitative and consists of a series of interviews using semi‐structured question guides that ask about parental perceptions and preferences related to recommended behaviours and the motivations, facilitators, barriers and other contextual factors that influence selection, trial and sustained use of new behaviours. During the first TIPs interview (T1), parents discussed their views and interpretation of the recommended nutrition goals and selected one goal to work towards with the focus child for the next 2 weeks (Table 1). After reviewing the parenting practices, parents were asked to choose one or more practices to apply in their efforts towards the selected nutrition goal. The T1 interview covered willingness to act on all nutrition and parenting recommendations, motivations for selecting specific behaviours, and expected barriers and facilitators. During the second TIPs interview (T2) at 2 weeks, parents discussed experiences with the selected practices including actual trial, response of family members, barriers and facilitators encountered, and intentions to continue. A final interview 4–6 months later (T3) assessed long‐term responses and factors affecting the sustainability of families’ efforts to improve eating behaviours.

Interviews were conducted by the principal investigator (KLD) and a graduate research assistant who was trained and supervised by the PI. Semi‐structured interview guides, training and regular debriefing sessions between interviews were used to ensure that the interviewing techniques were consistent, supported parents’ decisions and avoided bias in assessing responses to recommended practices. The PI reviewed the recorded interviews to monitor interviewing technique and data quality, and interview guides were adjusted as needed. Longitudinal spreadsheets were used to track participant response over time and prepare for subsequent interviews.

Qualitative data analysis and categorisation of responses

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and relevant text segments were qualitatively coded using the constant comparative method (Strauss & Corbin 1998) and sorted to allow analysis of responses across practices (ATLAS.ti, Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany). Textual data were analysed qualitatively to identify emergent themes (Strauss & Corbin 1998) related to the motivations, barriers and facilitators that influenced responses to each practice.

In addition to this thematic analysis, parents’ responses were categorised by indicators of acceptability and feasibility of practices. As originally designed, TIPs involved tallies of parents’ yes/no responses on willingness, actual trial and ability to continue new practices (Dickin et al. 1997). While small samples limit statistical analysis of such data, these categorical comparisons of recommendations help programme planners to identify practices that are viewed positively by substantial proportions of respondents.

A goal of this research was to categorise responses so that results could be summarised in simple programme‐relevant ways; however, the complexity and inter‐related nature of the HCHF recommendations made it challenging to code interview responses as yes or no. To address this, we undertook an iterative process of data reduction as part of the analysis (Miles & Huberman 1994). For each practice, we created four variables representing parental response across the series of interviews: ‘willing to change’ a practice (assessed at T1 interview), ‘selected’ a practice as a preferred option to try (at T1); ‘tried’ the practice (at T2); and ‘sustained’ trial (at T3). Qualitative responses were compiled in a spreadsheet by interviewers, facilitating identification of clusters of responses to each practice on each of the four variables. To strengthen the credibility of the analysis, another researcher not involved in interviewing (GS) independently coded all responses directly from interview transcripts. Results were compared, clusters of responses were refined, labelled and merged, and discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached.

For each variable, clusters of responses were categorised as positive (e.g. willing to change), negative (e.g. not willing to change) or not applicable (because the practice was not discussed in the relevant interview). This general scheme applied to all four variables (willing to change, selected, tried and sustained), although categorisation was not completely parallel because variation in clustering of responses emerged for different variables. The response categories and variations are summarised in Table 3 and are described below.

Table 3.

Summary of how Trials of Improved Practices interview responses on nutrition goals and parenting practices were categorised as indicating willingness, selection, initial and sustained trial

| Category | Willing to change (T1) | Selected to try (T1) | Tried (T2) | Sustained (T3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | Not discussed (researcher saw as not applicable) | Not discussed because parent not willing | Not discussed because parent did not select | Not discussed because parent did not select/try |

| Negative response |

|

|

|

|

| Positive response |

|

|

|

|

| *Notes on variation in categories by variable | ‘Already doing’ was categorised as not willing to change if parent not willing to increase/did not see as relevant to change. Interpreted as still indicating acceptability. | If parent viewed practice as a part of what they selected to try, categorised as selected even if not listed as primary selection by interviewer | Use of new practice at T2 was categorised as trial even if practice was not selected at T1. Interpreted as an indicator of feasibility. | Use at T2 that continued at T3 was categorised as sustained, even if practice was not originally selected at T1 |

Responses on willingness to change, selection, trial and sustained trial were categorised as positive only when the parents’ statements clearly indicated affirmative responses. Somewhat positive responses that sounded half‐hearted or hesitant in the context of the interview were categorised as negative (e.g. not willing to change, did not try). This conservative approach was adopted to counteract possible social desirability bias or a tendency for parents to respond in a way that would be viewed favourably by the interviewer (Hebert et al. 1995). Clear negative responses were also categorised as negative for all variables. Practices that were not discussed were categorised as ‘not applicable’. For example, in the T1 interviews, willingness to change was discussed for all practices, except for the few occasions when a parent's earlier comments made it clear that a practice was not applicable. After participants made their selections at T1, however, the focus of T2 and T3 interviews narrowed to the selected practices, such that fewer practices were discussed with each parent and more practices were scored as not applicable.

Subcategories were developed as needed to capture the nuances and patterns in qualitative data gathered over multiple time points. While this adds complexity to the presentation of results, it enriches the interpretation. For example, among parents who were not willing to change a particular practice, many stated that this was because they already used a practice or the child was doing well on a nutrition goal so there was no need for improvement. To capture this response, the subcategory ‘already doing’ was created. While categorised as ‘not willing to change’ because parents were not willing to increase use (not seeing it as relevant to do so), their pre‐existing use of the practice did indicate acceptability. Thus, it was important to distinguish between this ‘already doing’ response and that of parents who were not willing to try a practice because they saw it as unimportant or unacceptable. This subcategory and its interpretation are discussed in the presentation of results.

A subcategory of ‘selected’ was developed when we found that a review of interviews over time indicated that a parent felt an additional practice overlapped with the primary selected practice in a way that amounted to selecting it as well. For example, parents might explicitly select the goal of reducing EDFs but see providing more fruit or vegetable snacks as part of their strategy to achieve this. While not explicitly stating at T1 that they had chosen to try increasing vegetable and fruit intake, at subsequent interviews, they discussed the practice as part of what they selected. Categorising this practice as ‘not selected’ would not accurately represent parents’ perceptions and decisions. This subcategory of ‘selected’ took into account that parents sometimes chose to change their behaviour in ways that integrated several practices that they saw as closely related.

At T2, responses on ‘tried’ were categorised as positive if the parent reported trying a new practice, regardless of how well the child responded, and as negative if parent did not try the practice or provided an unconvincing report of trial. Parents were asked if they had used any other practices, to probe for changes in what they decided to try, and some reported trying practices that were different from their initial selections. These responses were categorised as positive for ‘tried’ using a subcategory to indicate that the practice was tried even though not explicitly selected. These practices were then discussed at T3 and categorised as positive for sustained trial if use of the practice had continued, even if not originally selected at T1.

After consensus on categorisation was reached, the frequency with which parents were willing to change, selected, tried and sustained new behaviours was compared across recommended practices. Results of categorisation were triangulated with qualitative analysis of why and under what circumstances the recommendations were chosen and used. Analysis and interpretation focused on the acceptability and feasibility of practices from the perspective of the parents interviewed.

Results

Characteristics of the sample (n = 23) reflected the population served by HCHF. All parents were low‐income and most were female and lived in urban areas (Table 4). Households had 4.3 members on average, ranging from 2 to 8. Almost one quarter reported low or very low food security in the preceding 12 months, similar to national rates in US households with children in 2010 (Coleman‐Jensen et al. 2011), and an additional quarter reported some concern about food security (classified as marginal food security). Parents’ age ranged from 21 to 42 years, with a mean of 31.6 (±6.25) years. Children were 3–11 years, with a mean of 6.5 (±2.3) years. About 65% of parents were overweight or obese, as were 30% of children. While over one‐third of parents reported some concern about children becoming overweight or eating too much, only 2 saw their child as overweight, 17 as normal weight and 4 as under or very underweight.

Table 4.

Descriptive analysis of sample characteristics (n = 23)

| Parents | Percent | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 91.3 | 21 | |

| Married/co‐habitating | 56.5 | 13 | |

| Single | 43.5 | 10 | |

| High food security | 52.2 | 12 | |

| Marginal food security | 26.1 | 6 | |

| Low food security | 8.7 | 2 | |

| Very low food security | 13.0 | 3 | |

| Participation in social programmes (for low‐income population) | 100.0 | 23 | |

| Employed part‐time | 26.1 | 6 | |

| Employed full‐time | 13.0 | 3 | |

| Urban residence (vs. rural or small town) | 61 | 14 | |

| Race | White | 52.2 | 12 |

| African American | 30.4 | 7 | |

| Caribbean Immigrant | 13.0 | 3 | |

| Latino | 4.4 | 1 | |

| Education | <High school | 8.7 | 2 |

| High school | 52.2 | 12 | |

| >High school | 39.1 | 9 | |

| Number of children | 1–2 | 56.5 | 11 |

| 3–4 | 43.4 | 10 | |

| BMI ≥ 25 (overweight) | 65.2 | 15 | |

| BMI ≥ 30 (obese) | 34.8 | 8 | |

| Focus child | Percent | Frequency | |

| Female | 52.2 | 12 | |

| Underweight (<5th percentile) | 8.7 | 2 | |

| Normal weight (5th to <85th percentile) | 60.9 | 14 | |

| Overweight (85th to <95th percentile) | 8.7 | 2 | |

| Obese (≥95th percentile) | 21.7 | 5 | |

BMI, body mass index.

Acceptability and feasibility of nutrition goals

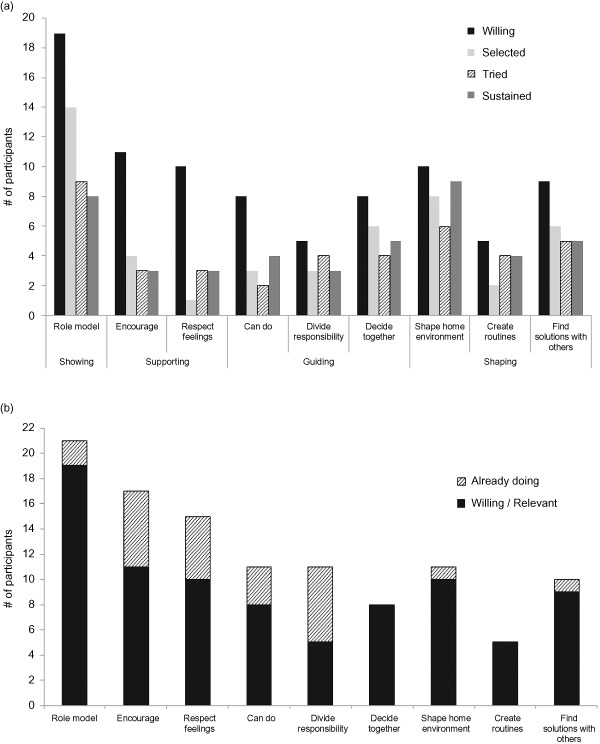

Results of categorical coding of interview data on parents’ willingness to change, selection, initial and sustained trial of practices related to nutrition goals are summarised in Fig. 1a. Willingness to change each practice often reflected views of whether or not a practice was relevant to the child since parents tended not to state that any practice was completely unacceptable. In Fig. 1b, stacked bars show the proportions of parents who were willing to change plus those who felt they were already doing well on a practice (i.e. it was not relevant for behaviour change but was acceptable, as evidenced by current use). Combining the two groups illustrates that most nutrition goals were widely accepted in the sample. The majority of parents who were willing to change practices aimed at improving vegetable and beverage intake went on to select and try these practices, but such responses were less common for reducing EDFs or limiting serving sizes. Results of categorising responses to each goal are integrated with the results of qualitative analysis on motivations, barriers and facilitators below.

Figure 1.

Parental response (n = 23) to recommended nutrition goals: eating more vegetables and fruit (V&F); drinking water or low‐fat milk instead of sugar‐sweetened beverages (SSBs); eating fewer energy‐dense foods (EDFs); and limiting amount of food consumed (Servings). (a) Response across four stages of interviews on willingness to change (or perceived relevance for behaviour change), selection of priority nutrition goal, initial (2 weeks) and sustained (4–5 months) trial. (b) Acceptability: Combining parents who were willing to work on or already doing well on recommended nutrition goals illustrates that most goals were well‐accepted.

‘Eating more vegetables and fruits’ was seen as relevant and selected by the largest number of parents, all of whom wanted children to eat larger amounts or a greater variety of vegetables (rather than fruit). Only the few parents who said their children already ate plenty of vegetables did not view this goal as relevant. Perceived barriers for achieving this goal were child preferences and pickiness and, to a lesser extent, adult food preferences, cost, spoilage and not knowing how to prepare vegetables. Parents were motivated by knowledge that vegetables were important for children's health and/or by health problems in the family. Almost all parents who selected this goal were able to try practices to encourage child vegetable consumption and reported sustaining the practices at long‐term follow‐up. Parents reported progress towards this goal, finding a few new vegetables that children would eat or strategies that helped children learn to try new vegetables.

Almost all parents recognised the importance of children drinking water or low‐fat milk in place of SSBs but fewer saw this as a relevant goal for their family because almost half felt they already did well in this area (Fig. 1b). The phrasing of this goal included several related aspects, and some parents focused on only one part, i.e. increasing water or increasing low‐fat milk intake or reducing SSBs. Interestingly, a couple of parents ended up trying practices related to this goal instead of what they originally selected, suggesting high feasibility relative to other practices. Some parents who originally did not see a need for change came to realise during or after the T1 interview that they could further reduce SSB intake. Most parents who selected this goal reported successful trial and ability to sustain new behaviours. The main motivations were to keep the child well hydrated, avoid sugar or increase calcium intake. Giving children their own water bottles was mentioned by several parents as a facilitator. Parents noted that it was helpful when schools and day cares restricted SSBs and one person mentioned saving money by not buying soda. Barriers included child not liking milk or water, a tendency to order soda when eating out, and children being accustomed to having SSBs at mealtime or as an affordable treat.

It's just … going to be hard. Like the main reason that we do get the big things of iced tea is because it'll last us throughout the month. You know, so by the time the end of the month comes and we have nothing, we at least have the iced tea. That's the main reason we get it, so the kids will at least have something to drink.

Eating fewer EDF was seen as relevant by many families, but fewer selected this as an area for change, sometimes because they viewed it as a difficult goal to achieve. Among those who did select this goal, most reported trying a new behaviour related to it. Motivations included health, weight problems (of child or in extended family) and concern that sugar negatively affected children's behaviour. As with SSBs, restriction of EDFs in schools and day care was mentioned as a facilitator, and some EDFs were seen as costly. The main perceived barriers were child and parental preferences for EDFs and their ubiquity outside the home. Change was seen as particularly challenging when a spouse or other adult in the household did the shopping or tended to bring EDFs into the home.

Well like I said, we don't do the fast foods, so that's good… Umm, Dad really likes sweets. So, I mean, they do come into the house.

Assessing parents’ willingness to try ‘having sensible servings’ was complicated by different interpretations of the wording of this recommendation. In HCHF, this refers to limiting the amount of food consumed by serving smaller amounts or eating only when hungry. Most parents who considered choosing ‘sensible servings’ as a goal did so because they felt that their child should eat more, not less, and once the meaning was clarified, many parents felt this was not relevant for their family.

Interviewer: And then what about sensible servings? Is that idea something you might like to try over the next 2 weeks?

Parent: Uh, no. We eat a lot but I think it's, it's good servings, you know. We're not like overweight or anything like that [chuckle]. I think we're doing good with that.

A few parents chose to be more conscious of amounts and started using measuring spoons or designated scoops to serve food, but did not explicitly limit the amount that children ate. The primary reason not to choose this was the perception that the child did not need to eat less (even when child BMI was indicative of obesity). In response to the questionnaire, many parents reported a concern about future child overweight or overeating, but few perceived children as currently overweight. Only one parent felt strongly that her child should eat less. She selected this goal and subsequently reported trying new practices and making some progress on limiting servings.

Acceptability and feasibility of parenting practices

Responses categorised as positive for parents’ willingness to change, selection, initial and sustained trial of parenting practices are summarised in Fig. 2a, grouped by cluster (see Table 2). In Fig. 2b, the number of parents willing to change each practice is combined with the number of parents who reported already using these practices in stacked bars that illustrate variation in acceptability. Figure 2 must be interpreted somewhat differently from Fig. 1 because parents were asked about parenting practices after they had selected a nutrition goal and responses reveal their views on whether a parenting practice was relevant and likely to be effective in encouraging children to make progress towards the selected nutrition goal. Lower ratings in Fig. 2, compared with Fig. 1, represent views on applicability to nutrition goals and do not indicate that parents viewed a parenting practice as generally unacceptable. There were also more parenting practices and those not initially selected were not discussed at later interviews, so results on initial and sustained trial are based on very small numbers for some practices. Although it was of interest to explore which parenting practices were selected in relation to each nutrition goal, this was best examined qualitatively because the numbers were very small when graphed by nutrition goal. Therefore, links between nutrition goals and parenting practices are discussed in the text and illustrated with quotes to highlight the reasons parents gave for seeing parenting practices as more or less relevant to nutrition goals.

Figure 2.

Response (n = 23) to recommended parenting practices, grouped by category. (a) Response across four stages of interviews on willingness to change (or perceived relevance as applied to nutrition goal), selection, initial (2 weeks) and sustained (4–5 months) trial. (b) Acceptability: Combining parents who were willing to change or already doing well on recommended parenting practices.

The first cluster, ‘showing,’ includes only one specific practice, role‐modelling. This was the most acceptable parenting practice, seen as relevant to all or most nutrition goals and selected most frequently by parents, although a few felt that their children were unlikely to adopt behaviours in response to parents’ example. Parents saw modelling as an important part of parenting and were sometimes motivated by the benefit of the nutrition practices for their own health, in addition to benefits for the child. Although it was also feasible, with many parents reporting that they successfully tried and sustained this practice, quite a few did not. Figure 2a shows that although willingness to change and selection were highest for this practice, actual trial occurred less frequently. Barriers were that parents found it difficult to change their own behaviours and be consistent, and sometimes lacked time to model behaviours to children. Role‐modelling was selected by most parents who chose the goals of increasing intake of vegetables and of healthy beverages, and also by about half of the parents aiming to decrease EDF consumption or limit servings and amounts of food consumed. The following quote illustrates perceived challenges and effectiveness of role‐modelling.

Interviewer: So why modelling? Why would you choose that one?

Parent: Because he really pays attention to what mommy does… I can't stand peas, but he had them when he was a baby and then once he realised mommy doesn't eat peas because mommy doesn't like them, then he didn't like them. So I'm like, ‘I'll eat peas, Ben, see?’ And yeah, he tried them. I had to wash my mouth out, but he tried them!

The cluster of ‘supporting’ or helping children feel better about themselves included two practices: ‘encouraging’ and ‘respecting feelings’. In HCHF, encouraging means noticing and providing positive feedback when the child does something that the parent likes. However, some parents interpreted ‘encouraging’ as explaining to children what they should eat and why. Interviewers clarified the intended meaning, but some responses were difficult to interpret. About half of the participants were willing to try using more encouragement and most of the rest felt that they already did this enough. Some parents did not select this because they felt that it was not likely to be effective depending on the child's mood or that it would be hard for parents to be positive when children refused to eat. Parents’ reasons for choosing this practice were that they felt the positive feedback would be effective and the child would respond well.

But one day she tried her vegetables… Everybody got really excited and we were saying how proud we were that she tried them and the next meal she wanted to eat every vegetable she had (laughs). Yeah, so I think just the positive feedback on it made her feel really good.

Respecting feelings (i.e. accepting children's feelings about the practices, including their negative responses) was seen as acceptable by many parents but most reported that they already practiced this. Only two selected this as a new practice to try, both as a means to increase vegetable intake. They used a strategy from the curriculum called a ‘no thank you bite,’ i.e. asking the child to try at least one bite of a food with the understanding that they would not have to eat it all, respecting that the child may or may not like the food. Other parents reported previous use of this approach and most of them felt that it was effective in the long run although some noted it could be frustrating if the child simply refused to try the new food.

But if he continues not to want it, we try not to pressure him into it because that's when he'll… develop a resentment for it or something like that.

The cluster of ‘guiding’ comprised three practices related to offering choices within limits: ‘can do’ (offering a child two or three options of what they can do or eat), ‘decide together’ (asking the child to suggest options themselves) and ‘divide responsibility’ (parents provide healthy foods and let children decide what and how much to eat) (Satter 2008). Given the overlap among these practices, it was informative to look at this category as a whole. Overall, about one‐third of parents were willing to change and about a quarter selected one or more of these practices. Most of these reported going on to try the practice, occasionally not until T3 because they had not yet had time to involve the child in meal planning by T2. Barriers included concerns that the child was not old enough to make decisions or would not be willing to choose the foods offered.

I've been trying to figure out should I make something that is new, along with something that I know they'll like to eat and I'm thinking no because the way I'm looking at it is, if I give them the choice between the two, they're going to go with the familiar thing. I don't want that… So I'm thinking probably the best thing is to make them have the new without the option of the other. Once they're used to it, then let them have the choice.

‘Can do’ was chosen by six participants and sustained by four. ‘Can do’ was not seen as relevant when parents had a specific food they wanted a child to eat. Parents who chose this practice said they did so because they recognised the importance of being firm and consistent, and not overwhelming young children with too many choices.

So that's what I do, just give him two choices. Sometimes he'll throw a fit for a little bit, but I just keep telling him, ‘These are your only choices,’ and it works.

Parents were also willing to use ‘decide together’ and of the six who selected it, most tried and sustained the practice. Parents often planned to try this by taking children to the grocery store to help choose items but reported barriers such as lack of time and the challenges of having young children make choices. As a result, this sometimes shifted towards ‘can do’ because parents let children choose from the vegetables in the fridge. Parents were motivated by the expectation that children would be more willing to eat foods that they chose, and some parents reported that this turned out to be the case.

Well it was really hectic the day I went to the grocery store, so I didn't bring her… I did, when I made a couple of meals, let her decide which vegetable we were going to have. So I would hold up two different things of vegetables and ask, ‘Which one do you want?’ We got her to eat corn and she hadn't eaten corn in over a year. So we've gotten her to eat corn and I don't know how exactly…’

‘Divide responsibility’ was slightly less likely to be seen as relevant and selected, compared to other practices in this category, but appeared feasible because those who chose it did try it. Parents applied this by asking children how much they wanted and by not pressuring children to ‘clean the plate’ or eat certain foods, but rarely allowed children to serve themselves.

The final cluster of parenting practices involved ‘shaping’ the home environment to make healthy choices easier, usually prioritising the availability of healthful foods at home by changing what was purchased and kept on hand. This was seen as relevant and selected by many parents, and was tried and sustained by most who chose it. Some did not try this until after the first 2 weeks, when they had a chance to shop or had used up the less healthy foods already in the home. This was the second most frequently selected parenting practice and was seen as particularly relevant for decreasing intake of EDFs and increasing vegetable intake.

‘Creating healthy routines’ was presented as another way to influence child behaviours through structuring the home environment. Parents rarely perceived this as relevant to the nutrition goals, perhaps due to lack of interviewer assistance in envisioning how to create routines that would help. A few parents did report this practice at T3 despite not originally selecting it, having discovered that they naturally created a routine, such as drinking water after active play, which was helpful for sustaining new practices.

‘Finding solutions with others’ was another way to shape home environments, particularly when a spouse or other adult was responsible for food shopping. Almost half of the parents were willing to work with another adult to change the foods brought into the house or model different eating patterns. The majority of this group went on to select this practice, most often in connection with the goals of increasing vegetables or decreasing EDFs.

I think the biggest one is just to talk to my husband about not buying it at all. Because then … they'll forget about it once it's not there. And they'll be hungry (laughs), you know, they'll eat what I cook. And sooner or later they're going to get used to it, and it's not going to be that much of a problem anymore.

Most who selected this were able to try it, and all who tried the practice reported sustaining it. Behaviour change was facilitated when the other adult's own health concerns motivated change in eating practices. The main barriers were lack of time to discuss changes or feeling powerless to gain consensus on food‐related behaviours. Particularly intractable problems were reported in cases of shared custody or with a relative other than a spouse, such as a grandparent.

Cross‐cutting barriers to behaviour change

Across the goals and practices tested, parental concerns with their own or children's health or weight motivated behaviour change, yet parents placed a very high priority on providing meals that children enjoy, so child preferences and responses had a great influence on parents’ views of acceptability and feasibility. The responses of spouses or other adults, which ranged from support to resistance, also strongly affected some parents’ ability to modify family eating practices. Occasionally, when another adult resisted changes, parents resorted to covert methods such as pouring low‐fat milk into another container to disguise what was being served. In a few families, very stressful circumstances such as living in a shelter or coping with chronic illness constrained adoption of new behaviours, evidence that the feasibility of commonly recommended practices cannot be assumed in high‐risk families. All of the families in this study had limited household resources and some faced food insecurity. Although keeping fruits and vegetables on hand was sometimes limited by cost, short shelf life and infrequent grocery shopping, parents more often reported that behaviour change was constrained by food preferences, habits and convenience.

Discussion

Identifying nutrition and parenting behaviours that low‐income parents can and will change is essential for designing effective programmes to prevent unhealthy weight gain among vulnerable children. This study tracking parents’ choices and trial of strategies to improve family eating habits addresses this need, both by assessing acceptability and feasibility in a small sample of parents and by adapting the TIPs methodology to explore responses to complex nutrition and parenting practices. Adaption of an approach that incorporates actual home‐based trial and follow‐up of response to new behaviours is an important contribution to the field and creates opportunities to apply the methodology in larger and more representative samples.

Although not all of the recommended practices worked well for everyone, most were seen as acceptable and feasible by proportions of the sample that were large enough to indicate suitability for inclusion in nutrition and parenting programmes promoting behaviour change in low‐income families. The main reason for not choosing any of the recommended nutrition goals was the parent's perception that the child was ‘already doing well’ in that area, so willingness to change was often best interpreted as perceived relevance for behaviour change. Increasing vegetable intake was the practice seen as most relevant and was selected most often, followed by drinking milk/water in place of SSBs and reducing consumption of EDFs. Parents were least willing to limit the amounts served to children. Almost all parents who selected a goal reported being able to take steps towards it and usually found it feasible to sustain the new behaviours. When asked to apply parenting strategies to reach the nutrition goals, parents reported that many of the practices related to role‐modelling, shaping home environments, giving limited choices and positive feedback helped them make changes at home. Acceptability of parenting practices was less consistent and the selection and trial of parenting practices varied according to nutrition goal selected. While role‐modelling appeared to be most widely accepted, changing the foods available at home and encouraging children were also seen as acceptable and feasible and were favoured as strategies to increase vegetable consumption. Shaping home environments was important for reducing consumption of EDFs. Lower scores for respecting feelings and creating routines reflected parents’ perceptions that these were already being used or were less directly applicable to nutrition goals.

We found no previously published studies following low‐income families through trials of new behaviours, although cross‐sectional studies or research in other populations generally support the findings reported here. Previous evidence that parents both understand the importance of increasing children's vegetable consumption and view it as challenging (Hingle et al. 2012) were confirmed in this sample of low‐income families. The importance of household food availability and the successful use of non‐directive parenting practices to promote vegetable consumption have been found among parents of Head Start children (O'Connor et al. 2010). Barriers to healthy eating (e.g. child food preferences, cooking skills, time, cost) and the importance of practices like role‐modelling and incorporating healthy eating into family routines have also been reported in other studies (Berge et al. 2012; Hingle et al. 2012; Pescud & Pettigrew 2012). Many of the practices and barriers reported by middle‐class parents were salient in this sample; in addition, families in the current sample reported barriers related to difficult living situations, food insecurity and economic instability.

Cross‐sectional research has identified food and parenting practices associated with healthier eating habits and weights among young children, but few studies measure whether interventions lead to changes in child feeding or parenting practices that are expected to mediate intervention effects on child outcomes (Skouteris et al. 2011). Methods for measuring these mediators have not generally been tested for sensitivity to change (Skouteris et al. 2011), highlighting a need for longitudinal qualitative research examining how behaviours change in families. Using TIPs to investigate responses over time and gather data on what is actually tried and why permits examination of how parents themselves view the causes and outcomes of their behaviours. Self‐determination theory (Deci & Ryan 1985) highlights the impact of choice on intrinsic motivation. HCHF presents an array of ‘paths’ towards healthier lifestyles and a set of parenting strategies to apply to these efforts, but allows parents to determine which specific behaviours to change, recognising that self‐determination can increase success in changing and maintaining behaviours. Similarly in TIPs, parents are asked to determine for themselves what works – at first verbally and then by trying new behaviours. In‐depth exploration of these choices and responses constitutes the unique value of the TIPs approach for assessing the relevance of programmatic recommendations.

Challenges were encountered in adapting the TIPs methodology to the diverse dietary recommendations and inter‐related parenting practices relevant to this population. The semi‐structured nature of the interviews, coupled with the complexity of the practices being discussed, led to differing amounts of discussion on practices across interviews and the results must be interpreted accordingly. For nutrition goals, parents were limited to one choice and this ‘forced choice’ highlighted priorities. Certain parenting practices were seen as relevant to particular nutrition goals, so selecting a nutrition goal first directly influenced which parenting practices were more likely to be selected and tried. Sometimes parents went on to try a practice other than their original choice. This complicated analysis but was an important source of information, suggesting that the practice the parent actually tried was more feasible or applicable in the home context.

The adaptation of TIPs and the categorisation of responses were preliminary and these data, particularly results on trial of practices, should be carefully interpreted given the self‐report nature of the data. The analytical process of categorising responses involved in‐depth qualitative review of interview data, and then the categorical data were interpreted together with the textual data (Miles & Huberman 1994). In addition to capturing information about difficulties and motivations, interview data were used to spot inconsistencies or hesitation suggestive of social desirability, and scoring was adjusted accordingly. Categorisation and graphing of responses was undertaken as a way to summarise and compare results across practices. While this led to insights about patterns of behaviour and was useful for succinct presentation of the data, there were limitations. This group of parents had already been through a programme that promoted changes in key nutrition and parenting behaviours, so there may have been little room to improve on some practices. Hence, acceptability was shown using stacked bars that combined ‘willing to change’ with ‘already doing this’. When participants reported no need for change, the practice was usually not discussed in subsequent interviews so results provide fewer insights on behaviours that were already widely practiced.

Assessing response to parenting practices was complicated by different interpretations of wording used in HCHF and by overlap among practices, e.g. convincing a spouse to set a good example by eating vegetables or by drinking water instead of soda is related to ‘finding solutions with others’ and also to role‐modelling. Discussion among researchers and review of interview responses helped to clarify parents’ responses and create a consistent approach for categorising responses. In the future, a format that allows interviewers to score willingness, selection and trial during the interviews and confirm scores with parents would increase the ease and validity of scoring.

Except when parents did not have time to try new practices by T2, little new information was obtained at the 4–6 month follow‐up. Most parents reported sustaining the new practices but it was difficult to assess long‐term impacts on behaviour. Sometimes, children's development over this period meant that the selected nutrition goal was no longer as relevant. To avoid this problem and still assess whether use is sustained beyond 2 weeks, it might be more useful and efficient to conduct T3 after an interval of about 2 months. It is also important to note that although parents shared their views on whether new practices influenced children's eating, this study focused on acceptability and feasibility and was not designed to assess whether changes significantly improved child diets. Trial was categorised as positive based on the parent trying the new practice, not on the impact on the child's behaviour.

Although adequate for illustrating the use of TIPs and developing categories for summarising qualitative responses, sample size was limited by the demands of adapting the methodology to complex practices and the in‐depth nature and number of data collection episodes. Sample representativeness was constrained because of the need to select HCHF programme participants familiar enough with the practices to select and try them. Interpretation must take into account that during programme participation, these parents were exposed to and may have already adopted some of the recommendations. However, many of the practices covered in HCHF are also widely promoted in the media and any sample of parents would include people who currently practice some of these recommendations. Although the programme‐based sample may limit generalisation of the results, the families were purposefully sampled to maximise variation on several characteristics including HCHF educators’ perceptions of parents' motivation and behaviour change during the programme. This was a diverse, low‐income sample of families that faced many challenges to eating well and was representative of families who participate in HCHF and similar programmes. As such, this sample was appropriate for testing the methodology and the programmatic recommendations.

Conclusions

TIPs is a mixed‐methods approach to obtain parents’ input on recommended nutrition and parenting practices, based on actual choices and experiences trying practices at home. The adaptation of TIPs to assess acceptability and feasibility of practices related to promoting healthy weights among 3–11‐year‐olds presented challenges but demonstrated a new application of this method. Results contributed to greater understanding of factors influencing behaviour change in low‐income families. Parents were interested in increasing children's vegetable consumption and reducing consumption of EDFs and SSBs, and preferred to focus on the types of foods that were served or available rather than limiting portions. Parenting practices such as role‐modelling, shaping home environments, providing positive feedback and sharing decision‐making were well‐received by many parents, although there was variation in perceived effectiveness and relevance to particular nutrition goals. Overall, practices were viewed as acceptable and feasible by meaningful proportions of the small sample, but there were also salient barriers related to time, cost, food preferences and habits, and perceptions that a strategy would not be effective. This study demonstrated that the TIPs approach can be applied to new contexts and practices and has strong potential for providing valuable guidance for designing childhood obesity prevention programmes.

Source of funding

This research was supported by Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station federal formula funds, Project No. NYC‐399860, received from the US Department of Agriculture. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the US Department of Agriculture.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributions

KLD designed and implemented the research, led data analysis and interpretation, and prepared the final manuscript. GS conducted quantitative data coding and contributed to analysis, drafting and revision of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Amelia Willits‐Smith for data collection and qualitative data coding, Cornell Cooperative Extension staff for assistance in recruiting participants, and Jamie Dollahite, Tisa Hill and Wendy Wolfe for collaboration on developing HCHF. Marcia Griffiths laid the foundations for this study through her years of work developing the TIPs methodology. Special thanks to the families who put time and effort into sharing their experiences with us.

Dickin, K. L. , and Seim, G. (2015) Adapting the Trials of Improved Practices (TIPs) approach to explore the acceptability and feasibility of nutrition and parenting recommendations: what works for low‐income families?. Matern Child Nutr, 11: 897–914. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12078.

References

- Bailey J., Perkins S. & Wilkins S. (1995) Parenting Skills Workshop Series. Cornell Cooperative Extension: Ithaca, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Bante H., Elliott M., Harrod A. & Haire‐Joshu D. (2008) The use of inappropriate feeding practices by rural parents and their effect on preschoolers’ fruit and vegetable preferences and intake. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 40, 28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge J.M., Arikian A., Doherty W.J. & Neumark‐Sztainer D. (2012) Healthful eating and physical activity in the home environment: results from multifamily focus groups. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 44, 123–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel G., Nord M., Price C., Hamilton W. & Cook J. (2000) Guide to Measuring Household Food Security, Revised 2000. U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service: Alexandria, VA.

- Birch L.L., Fisher J.O., Grimm‐Thomas K., Markey C.N., Sawyer R. & Johnson S.L. (2001) Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: a measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite 36, 201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birckmayer J. (2001) Discipline Is Not a Dirty Word. Media and Technology Services, Cornell University: Ithaca, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman‐Jensen A., Nord M., Andrews M. & Carlson S. (2011) Household Food Security in the United States in 2010. Economic Research Service: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Darling N. & Steinberg L. (1993) Parenting style as context: an integrative model. Psychological Bulletin 113, 487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M.M., Gance‐Cleveland B., Hassink S., Johnson R., Paradis G. & Resnicow K. (2007) Recommendations for prevention of childhood obesity. Pediatrics 120, S229–S253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci E.L. & Ryan R.M. (1985) Intrinsic Motivation and Self‐Determination in Human Behavior. Plenum: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Dickin K., Griffiths M. & Piwoz E. (1997) Designing by Dialogue: A Program Planners’ Guide to Consultative Research for Improving Young Child feeding. Academy for Educational Development: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Economic Research Service (2012) U.S. Adult Food Security Survey Module: Three‐stage Design, with Screeners [Online]. USDA: Washington, DC. Available at: http://ers.usda.gov/datafiles/Food_Security_in_the_United_States/Food_Security_Survey_Modules/ad2012.pdf (Accessed 10 November 2012).

- Faith M.S. & Kerns J. (2005) Infant and child feeding practices and childhood overweight: the role of restriction. Maternal & Child Nutrition 1, 164–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith M.S., Scanlon K.S., Birch L.L., Francis L.A. & Sherry B. (2004) Parent‐child feeding strategies and their relationships to child eating and weight status. Obesity Research 12, 1711–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert J.R., Clemow L., Pbert L., Ockene I.S. & Ockene J.K. (1995) Social desirability bias in dietary self‐report may compromise the validity of dietary intake measures. International Journal of Epidemiology 24, 389–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy E., Hughes S.O., Goldberg J.P., Hyatt R.R. & Economos C.D. (2010) Parent behavior and child weight status among a diverse group of underserved rural families. Appetite 54, 369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingle M., Beltran A., O'Connor T., Thompson D., Baranowski J.A. & Baranowski T. (2012) A model of goal directed vegetable parenting practices. Appetite 58, 444–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S.O., Power T.G., Orlet Fisher J., Mueller S. & Nicklas T. (2005) Revisiting a neglected construct: parenting styles in a child‐feeding context. Appetite 44, 83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S.O., Anderson C.B., Power T.G., Micheli N., Jaramillo S. & Nicklas T.A. (2006) Measuring feeding in low‐income African‐American and Hispanic parents. Appetite 46, 215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (2004) Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. National Academies Press: Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (2011) Early Childhood Obesity Prevention Policies. National Academies Press: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce J.L. & Zimmer‐Gembeck M.J. (2009) Parent feeding restriction and child weight. The mediating role of child disinhibited eating and the moderating role of the parenting context. Appetite 52, 726–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika S. & Grier S. (2006) Targeting interventions for ethnic minority and low‐income populations. The Future of Children 16, 187–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika S.K. (2008) Environmental influences on childhood obesity: ethnic and cultural influences in context. Physiology & Behavior 94, 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lent M., Hill T.F., Dollahite J.S., Wolfe W.S. & Dickin K.L. (2012) Healthy children, healthy families: parents making a difference! A curriculum integrating key nutrition, physical activity, and parenting practices to help prevent childhood obesity. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 44, 90–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay A., Sussner K., Kim J. & Gortmaker S. (2006) The role of parents in preventing childhood obesity. The Future of Children 16, 169–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouff J.M., Thorsteinsson E.B. & Schutte N.S. (2007) The efficacy of problem solving therapy in reducing mental and physical health problems: a meta‐analysis. Clinical Psychology Review 27, 46–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M. & Huberman M. (1994) Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor T.M., Hughes S.O., Watson K.B., Baranowski T., Nicklas T.A., Fisher J.O. et al (2010) Parenting practices are associated with fruit and vegetable consumption in pre‐school children. Public Health Nutrition 13, 91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick H., Nicklas T.A., Hughes S.O. & Morales M. (2005) The benefits of authoritative feeding style: caregiver feeding styles and children's food consumption patterns. Appetite 44, 243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M.Q. (1990) Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Pescud M. & Pettigrew S. (2012) ‘I know it's wrong, but…’: a qualitative investigation of low‐income parents’ feelings of guilt about their child‐feeding practices. Maternal & Child Nutrition [Epub ahead of print]. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00425.x (Accessed 2 January 2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K., Davis R. & Rollnick S. (2006) Motivational interviewing for pediatric obesity: conceptual issues and evidence review. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 106, 2024–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satter E. (2008) Secrets of Feeding a Healthy Family. Kelcy Press: Madison, WI. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M.B. & Brownell K.D. (2007) Actions necessary to prevent childhood obesity: creating the climate for change. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 35, 78–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skouteris H., McCabe M., Swinburn B., Newgreen V., Sacher P. & Chadwick P. (2011) Parental influence and obesity prevention in pre‐schoolers: a systematic review of interventions. Obesity Reviews 12, 315–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A. & Corbin J. (1998) Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura A. & Birch L. (2008) Does parenting affect children's eating and weight status? International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 5, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J. & Carnell S. (2007) Parental feeding practices and children's weight. Acta Paediatrica 96, 5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J., Carnell S. & Cooke L. (2005) Parental control over feeding and children's fruit and vegetable intake: how are they related? Journal of the American Dietetic Association 105, 227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward‐Lopez G., Ritchie L.D., Gerstein D.E. & Crawford P.B. (2006) Obesity: Dietary and Developmental Influences. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]