Abstract

Preterm infants are usually breastfed less than full‐term infants, and successful breastfeeding requires a supportive environment and special efforts from their mothers. A breastfeeding peer‐support group, utilising social media, was developed for these mothers in order to support them in this challenge. Mothers were able to discuss breastfeeding and share experiences. The purpose of this study was to describe the perceptions of breastfeeding mothers of preterm infants based on the postings in peer‐support group discussions in social media. The actively participating mothers (n = 22) had given birth <35 gestational weeks. They were recruited from one university hospital in Finland. The social media postings (n = 305) were analysed using thematic analysis. A description of the process of breastfeeding a preterm infant from the point of view of a mother was created. The process consisted of three main themes: the breastfeeding paradox in hospital, the ‘reality check’ of breastfeeding at home and the breastfeeding experience as part of being a mother. The mothers encountered paradoxical elements in the support received in hospital; discharge was promoted at the expense of breastfeeding and pumping breast milk was emphasised over breastfeeding. After the infant's discharge, the over‐optimistic expectations of mothers often met with reality – mothers did not have the knowledge or skills to manage breastfeeding at home. Successful breastfeeding was an empowering experience for the mothers, whereas unsuccessful breastfeeding induced feelings of disappointment. Therefore, the mothers of preterm infants need evidence‐based breastfeeding counselling and systematic support in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and at home.

Keywords: breastfeeding, breast milk, preterm infant, mother support group, qualitative methods

Introduction

Breastfeeding is the most natural, and nutritionally the best, way to feed an infant (WHO/UNICEF 2003). For vulnerable preterm infants, breast milk provides nutritional, gastrointestinal, immunological and developmental benefits. The psychological benefits should not be underestimated either; breastfeeding strengthens the mother–infant relationship, which may be threatened by the separation often necessary with preterm infants (Callen & Pinelli 2005). For very low‐birthweight infants, the benefits of breast milk ingestion may even continue for several years (Vohr et al. 2007). Their initial weight gain may be suboptimal, but the neurodevelopmental outcome at the age of five is better for a very preterm infant when they had been breastfed (Rozé et al. 2012).

Breastfeeding preterm infants present many challenges for mothers, including establishing and maintaining their milk supply without the stimulation of the infant. Another major challenge is the transition from gavage feeding to breastfeeding (Callen & Pinelli 2005). Preterm infants are usually breastfed less than full‐term infants (Flacking et al. 2007; Donath & Amir 2008). The breastfeeding rates of preterm infants at the time of discharge vary from 19% to 70% in Europe (Bonet et al. 2011); in Sweden, for example, as many as 74% of preterm infants are exclusively breastfed at discharge and 49% after 2 months (Flacking et al. 2003). However, the breastfeeding rates in Finland are not as high as those in Sweden; fewer than 30% of preterm infants in Finland are exclusively breastfed at 2 months of age (Uusitalo et al. 2012). Breastfeeding a preterm infant can be quite a different experience from that which the mothers had expected (Flacking et al. 2006). However, it is possible to breastfeed even the smallest of preterm infants; indeed, an infant's gestational age at birth is not associated with the likelihood of that infant being breastfed at the time of their hospital discharge (Hedberg Nyqvist 2008; Zachariassen et al. 2010). Exclusive breastfeeding may be possible even at the post‐conceptional age of 32 weeks (Hedberg Nyqvist 2008).

Most of the previous studies on the breastfeeding of preterm infants have focused on the benefits or duration of breastfeeding (Andersson et al. 1999; Heiman & Schanler 2006; Quigley et al. 2007; Vohr et al. 2007) or the ability of preterm infants to breastfeed (Hedberg Nyqvist & Ewald 1999; Dodrill et al. 2008; Hedberg Nyqvist 2008; Jones 2012); only a few studies have addressed the views of mothers breastfeeding preterm infants. Earlier studies by Hill et al. (1994) and Kavanaugh et al. (1995) found that the main concerns of these mothers were whether the preterm infants consumed an adequate volume of milk and concerns over milk production. However, the mothers managed their concern about the adequate volume of milk by using complemental and supplemental feedings (Kavanaugh et al. 1995). Furthermore, according to the study of Jaeger et al. (1997), the reasons for changing from breastfeeding to formula feeding were separation, stress and problems with expressing the milk. Most notable was the study conducted by Flacking et al. (2006), which investigated how the mothers of very preterm infants experienced the breastfeeding process emotionally. The authors suggested that the best support for breastfeeding is a favourable environment, enhancing the mother's self‐confidence. To facilitate this environment, and to succeed in breastfeeding, a preterm infant's mother needs counselling and support, which may be provided by peer‐support. Peer support conducted by home visits or via the telephone is an efficient way to increase breastfeeding in preterm infants (Merewood et al. 2006; Ahmed & Sands 2010).

In this study, a breastfeeding peer‐support group utilising Internet‐based social media (Facebook) was developed for the mothers of preterm infants to support them in their challenges to breastfeeding. The mothers of preterm infants were able to discuss breastfeeding from their own point of view and were able to share their experiences and feelings with peer supporters provided by the study and with the other participating mothers. Based on these peer discussions, it was possible to access the mothers' views and perceptions and understand the issues and problems that were relevant to them when they were breastfeeding their preterm infants. The purpose of this study was to describe these perceptions.

Key messages

The mothers of preterm infants encountered many paradoxical elements related to breastfeeding in hospital; early discharge was promoted at the expense of breastfeeding and breast milk was emphasised over breastfeeding.

Mothers' optimistic visions of breastfeeding met with the reality at home after the infant's discharge. Breastfeeding counselling in the NICU had been inadequate and the mothers did not have the skills to manage breastfeeding.

Mothers regarded successful breastfeeding to be an empowering experience, whereas unsuccessful breastfeeding was associated with feelings of disappointment and shame.

Peer support through social media is one possibility to support breastfeeding mothers of preterm infants.

Materials and methods

Setting and sample

This qualitative study was performed in Finland, where the common attitude towards breastfeeding is positive (Hannula 2003), but the breastfeeding rates are not as good as those outlined within the recommendations (Uusitalo et al. 2012). A clinical practice guideline for breastfeeding support has been published in Finland, but it is only based on research concerning healthy, full‐term infants (Hannula et al. 2010). The Finnish National Institute for Health and Welfare has guidelines for breastfeeding preterm infants, including practical advice for breastfeeding counselling, which were created for nurses in child health clinics (Ikonen et al. 2012).

The Facebook peer‐support group for mothers of preterm infants used in this study was developed as part of a randomised clinical trial, in which the aim was to recruit 128 mothers of preterm infants. The mothers were randomised into two groups. Both groups received routine care and support for breastfeeding, with the mothers in the experimental group also being given the possibility to join the breastfeeding peer‐support group in Facebook. The participating mothers had given birth before the full 35 gestational weeks and all the infants were transferred to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). The mothers were recruited during the first week post‐partum in one university hospital in Finland. This study hospital is one of the five level III (highly specialised care) hospitals in Finland, with 18 infant beds in its NICU. There are 45 nurses working in this NICU; one nurse had participated in the WHO/UNICEF 20‐h course for staff on breastfeeding, and approximately 10 nurses had participated in a breastfeeding support course organised by the hospital. The unit has free visiting hours for parents and there is one separate room designated for breastfeeding and for pumping milk. The hospital also has a breast milk bank for processing and storing donor breast milk. The aim is for infants in the NICU to have breast milk for nutrition from the day they are born. After the most critical period, some infants are transferred to other level II NICUs located nearer their homes.

The Facebook peer‐support group was only available for the mothers randomised into the experimental group. These mothers received guidance on how to find and join this group during the first week post‐partum: there was no organised Internet access in the hospital. The mothers were encouraged to use the peer‐support group based on their individual needs. The peer support was provided by three voluntary mothers, recruited from a local Finnish association for families with preterm infants, who thus had previous experiences of breastfeeding preterm infants. However, they all had very individual experiences of breastfeeding their own preterm infants and were not expected to have ‘successfully’ breastfed their own baby. The peer supporters had no special training; they were only asked to support and encourage the new mothers. In addition, the participating mothers provided peer support for each other, and a midwife (the first author) was available to answer any questions related to breastfeeding. The participating mothers had access to the group for at least a year after their infant was born.

Ethical issues

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital district of Southwest Finland, and permission for the study was granted by the hospital in which the mothers were recruited. Informed written consent was obtained from the participating mothers. The informed consent for analysing the postings was obtained in a separate form before the peer‐support group was accessed. Mothers who did not want to have their postings analysed could still participate in the study and the peer‐support group. During the data analysis, the participants' names were replaced with codes to protect their anonymity and confidentiality. Direct quotes were used with caution and possible identifiers, for example, the number of previous children or exact gestational weeks, were deleted.

Data collection

The data were accumulated between June 2011 and February 2013. All the postings from the peer‐support group were downloaded, and all of the mothers agreed to have their postings analysed, although eight mothers did not write any comments. In total, there were 305 postings written by 22 mothers, the three peer supporters and the midwife.

Data analysis

Inductive thematic analysis was used to explore the content of the peer discussions conducted by the breastfeeding mothers of preterm infants (Braun & Clarke 2006). The units of analysis were the online messages posted by the mothers, the peer supporters and the midwife. In the first phase, the data were inductively coded by the first author (HN‐V) and the initial themes were identified. During the second phase, the other author (AA) familiarised herself with the raw data and formed the initial codes. Based on several discussions, these two authors (HN‐V and AA) formed a comprehensive understanding about the underlying patterns within the data and produced suggestions for the major themes, such as breastfeeding challenges at discharge. During the third phase, after denser coding, the codes were collated under sub‐themes – such as early discharge at the expense of breastfeeding – which characterised them at a higher abstract level. In the fourth phase, the sub‐themes that formed a coherent pattern were then precisely defined. In the last phase, the sub‐themes were collated under three major themes. The other two authors (H‐LM & SS) also familiarised themselves with the raw data and provided feedback in every phase of the analysis. The themes and their definitions were discussed between all the authors. After a final review, these themes with definitions were identified and named.

It is noteworthy that the researcher and the first author of this paper was also the midwife participating in the peer‐support group. Inevitably, her education and previous work experience as a midwife had some influence on her perceptions of breastfeeding, although she has not worked in a NICU specifically. However, it is possible that the background of the researcher may have influenced the qualitative analysis; the attitude towards breastfeeding was positive from the outset, and the purpose of the group was to promote breastfeeding.

Results

Participants and postings

Altogether, 30 mothers and three peer supporters participated in the peer‐support group and 305 social media postings were included in the analysis. Most postings were written by the participating mothers (n = 221); the peer supporters had written 36 and the midwife 48 postings. Twenty‐two mothers and all the peer supporters (n = 3) actively participated in the discussions; the remaining participants (n = 8) could be considered as passive observers, in that they read but did not participate in discussions themselves. The median number of postings per actively participating mother was 4.5, ranging from 1 to 39. The median age of the mothers, not including the peer supporters, was 29 years, the range being 20–46 years; the number of previous children ranged between 0 and 4, but most (n = 21) of the mothers were primiparae.

In total, there were 44 discussions related to breastfeeding including several similar topics from different perspectives, of which 25 were started by the mothers and 19 by the midwife. The peer supporters did not initiate any discussions. Questions presented by the midwife acted as stimulants for discussion. These questions related to the infant's gestational age at birth and at first breastfeeding, how milk supply can be maintained at home and in hospital, breastfeeding expectations, the initiation of breastfeeding, breast pumps, counselling in child health clinics, the best possible breastfeeding counselling, kangaroo care and mastitis. In addition, on several occasions, the midwife encouraged the mothers to discuss the current situation of their breastfeeding.

The discussions had a mean response rate of six postings, ranging from 0 to 26 responses. Two of the discussions started by mothers were tips for other mothers; they did not include a question or request for an answer and therefore had zero responses. However, other participants reacted to these postings by clicking a ‘Like’ button, which is a way in Facebook to support someone's posting without necessarily writing any further comment. Mothers usually started new discussions during the day; 18 discussions were started between 7 am and 10 pm and 7 discussions were started between 10 pm and 7 am. The first answer to a new discussion topic was given, on almost every occasion, within one day, and often within a few hours.

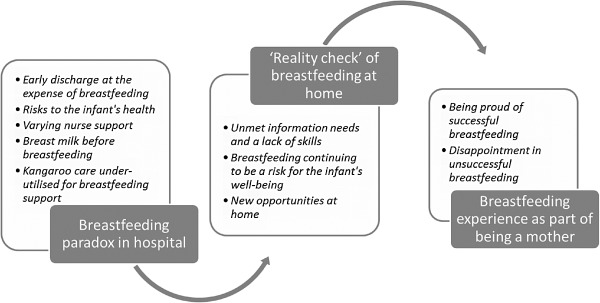

By analysing these postings, three major themes describing the process of breastfeeding a preterm infant from the point of view of mothers were identified. They describe the process of breastfeeding a preterm infant beginning in hospital, directly after the infant was born and being re‐actualised at home, after the hospital discharge. Eventually, this process also affected the experience of motherhood. Thus, themes describing this process were defined as follows: the breastfeeding paradox in hospital, the ‘reality check’ of breastfeeding at home and the breastfeeding experience as part of being a mother (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The process of breastfeeding from the point of view of a mother of a preterm infant.

Breastfeeding paradox in hospital

Breastfeeding in hospital was described as paradoxical from the point of view of the mothers, as they felt that they received contrasting advice and counselling from the nurses. In addition, they did not have the energy themselves to focus on breastfeeding without support in the hospital due to the many other issues related to their infant's care. There were several different paradoxical elements that were related to the initiation of breastfeeding in hospital. This breastfeeding paradox in hospital consisted of five dimensions: (1) early discharge at the expense of breastfeeding; (2) risks to the infant's health; (3) varying nurse support; (4) breast milk before breastfeeding; and (5) kangaroo care under‐utilised for breastfeeding support.

Early discharge at the expense of breastfeeding

According to most of the mothers, the main goal of NICU care was discharging the infant as early as possible. Important criteria for discharge were oral feeding and sufficient weight gain. The mothers highlighted that the infants' weight gain was strongly emphasised during their hospitalisation; furthermore, they were clearly advised by the staff that bottle‐feeding ensured a faster discharge than breastfeeding as optimal growth was easier to obtain with bottle‐feeding.

Some of the mothers admitted that they did not have the mental resources to be interested in breastfeeding in the hospital. They imagined that breastfeeding would be something that would happen in the future, when the infant was at home; thus, they assumed that they would be able to start breastfeeding successfully at home.

As I recall, in the NICU we tried to breastfeed once and that ended up in crying because it hurt my nipple so much. After that, we were transferred to another children's ward, from where my topmost recollection is that bottle‐feeding ensures a faster discharge, although one nurse did try to arrange some breastfeeding training. Now the baby is suckling/tries to suckle at my breast once or twice per day, but usually he is still hungry after our breast sessions or our nerves fray. (010)

Risks to the infant's health

The mothers also reported that breastfeeding was sometimes restricted by the nurses. For example, that the duration of breastfeeding was limited, or that they were only allowed to breastfeed once a day. The nurses explained these breastfeeding limitations to the mothers with concerns for the infant's health, such as compromised breathing, limited physical resources and optimal weight gain. According to the mothers' discussions, these restrictions inevitably resulted in a decrease in breast milk secretion, or in the infant being unable to suckle the breast because she or he was used to suckling a bottle.

During the hospitalisation, baby ate 5–30 mL/time. However, generally around 15 mL. There wasn't even time to eat more because the duration of breastfeeding was limited to 15 minutes (in my opinion, it was a stupid rule, so that the baby still had the resources to suck the bottle after breastfeeding). There was no problem with breathing. (014)

Varying nurse support

Most of the mothers perceived that the quality of support for breastfeeding was dependent on the individual nurse. Some mothers were satisfied with the breastfeeding counselling and they felt encouraged by their nurses. The mothers felt that breastfeeding was more likely to be successful in the future if their milk secretion started fluently and their infant's condition was stable enough to allow breastfeeding within a few days. The mothers who were satisfied with the support described their first breastfeeding experience as a positive and successful event. However, according to the mothers' discussions, nurses who favoured breastfeeding were in the minority.

Some of the mothers were not satisfied with the guidance and support provided in the NICU. These mothers felt that not all the nurses were motivated enough to support breastfeeding – in fact, some nurses did not provide any support for breastfeeding and the mothers were left alone in their efforts to breastfeed. The intensive care environment was also considered to be too restless for practising breastfeeding. This was particularly a problem for the mothers who wished to practise breastfeeding alone with their infants in a quiet place. Most of all, the mothers wished for equal and individual guidance and support from all the nurses, as they considered the NICU to be the most important place to obtain guidance and support for breastfeeding. The counselling given in the NICU was crucial for them to be able to manage breastfeeding and its potential challenges at home. Furthermore, based on the peer‐support group discussions, most of the mothers of preterm infants followed, without question, the breastfeeding guidance they had received from nurses.

In the NICU some nurses were really sweet and supportive, but some seemed to be a little confused with the whole breastfeeding issue. I think the support is much more than just training the latch or the breastfeeding position, and I was hoping for more information especially about how to manage at home, when the baby is used to the bottle, and what kind of problems may exist and how to manage them. You are not able to ask all relevant questions in hospital when you are worried about the health of your baby and the main issue is that the baby is getting food, one way or another. In hindsight, I would have acted differently when we got home, but then, as a novice, I ruined my opportunity to exclusively breastfeed. (024)

Breast milk before breastfeeding

All of the mothers reported that nurses constantly emphasised the importance of breast milk and of pumping milk. They asked the mothers on a daily basis about the amount of breast milk and the frequency of pumping, and some of the mothers felt that this questioning was oppressive. Some mothers felt that the use of formula was totally undesirable; however, they were led to believe that they would not be able to manage infant feeding at home without expressing their own breast milk. In the mothers' comments about breastfeeding during their care in hospital, breast milk and breastfeeding seemed to be two unconnected issues, with the first related to the NICU and the latter to the home.

The mothers found that maintaining their milk supply was difficult and burdensome. Breast pumping had to be conducted regularly, both day and night, for up to several weeks. The major problems experienced with this were difficulties in initiating lactation and the small amounts of milk produced. At home, the mothers had to pump their milk very regularly and wash and disinfect the bottles and the parts of the breast pump; pumping seemed to demand a lot of work and they felt as if it were taking over their lives. The mothers reported that the quality of the breast pump was important for the milk supply and for successful pumping. However, the most important things for a successful milk supply were the environment, the mood of the mother and the amount of stress experienced. Some of the mothers were able to pump their milk for months even though the infant did not learn how to suckle the breast. In addition, a small number of the mothers donated their breast milk because the amount of milk exceeded the needs of their own infant.

I didn't consider breastfeeding or even breast milk to be very important in advance, even though I imagined that I would breastfeed exclusively for six months. However, during the baby's hospitalisation the older nurses created quite a pressure. When you were stressed and the mood was low, it wasn't nice to hear daily the report of whether my own pumped milk was enough or not. I had to answer the nurses' questions about whether I was pumping at night or not; and even if I said yes, I had a feeling that they didn't believe me. Near to the time of our discharge, the older nurses said that we were not going to have a prescription for formula and we MUST manage with my own breast milk. And, that the baby would not grow properly with ordinary formula. (014)

Kangaroo care under‐utilised for breastfeeding support

A few mothers thought that kangaroo care promoted their milk secretion, but not all mothers noticed these effects. Kangaroo care was particularly provided, almost every day, for very preterm infants who were hospitalised for long periods. The mothers, without exception, expressed the opinion that kangaroo care was ‘wonderful’. Despite these positive experiences, very few mothers continued with the kangaroo care at home. According to the mothers' discussions, nurses and doctors were very positive about kangaroo care and they always encouraged parent to ‘kangaroo’. Nevertheless, the mothers also perceived that staff did not use kangaroo care to support breastfeeding; indeed, none of the mothers reported that they had been encouraged to provide their infants with the possibility to suckle the breast when kangarooing.

I believe that the daily kangarooing was really important because if the milk secretion didn't start properly, but during kangarooing it started to flow. (025)

Yes, we were able to kangaroo with both babies and they really encouraged us to do it! Both nurses and doctors! It was absolutely wonderful. We hardly ever practiced kangaroo at home. (033)

The ‘reality check’ of breastfeeding at home

From the point of view of the mothers, the next step in the process of breastfeeding a preterm infant was their discharge from hospital – the long‐awaited event had eventually arrived. In the hospital, the nurses had been taking care of the infants but suddenly, at home, the mother was responsible for the infant's care alone. This was also seen as the time to start breastfeeding, but it was more challenging than the mothers had expected. This ‘reality check’ of breastfeeding at home included three dimensions: (1) unmet information needs and a lack of skills; (2) breastfeeding continuing to be a risk for the infant's well‐being; and (3) new opportunities at home.

Unmet information needs and a lack of skills

After the infant's discharge, the mothers' breastfeeding expectations were met with reality. Previously, most of the mothers had held a generally optimistic vision of breastfeeding and they had not expected any problems. However, the mothers often reported realising that the breastfeeding counselling provided in the hospital was insufficient for their needs at home. Indeed, they discussed the counselling given in the hospital as inadequate, or even as a barrier to breastfeeding. For example, the mothers had been advised to avoid breastfeeding until the infant's weight was sufficient, or they had been advised to breastfeed only once a day. Importantly, in addition to a lack of knowledge, the mothers felt that they did not have the skills required to solve their problems.

After discharge, we tried to practice breastfeeding by ourselves. It didn't work out at all; the ducts were constantly blocked, the baby's latch wasn't right and I was awfully stressed about it. (014)

They said no breastfeeding at all before the weight is clearly increasing. Well, after a few weeks the baby refused to suckle the breast and he only accepted the bottle. (011)

Almost all of the questions posted by the mothers were related to breastfeeding problems encountered at home. They reported being insecure about when and how to change from bottle‐feeding to breastfeeding; they wanted to know if there were guidelines concerning the optimal age or weight of the infant. The mothers also asked questions concerning whether the infants were getting enough milk from the breast and how to improve the latch. They felt that they did not have enough knowledge about maintaining or increasing their milk supply. One mother asked why her infant refused to latch and instead just cried. Some questions were also related to breastfeeding at night and breastfeeding with mastitis.

Many of the questions asked were related to other mothers' experiences. For example, they wanted to know about their experiences of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and breastfeeding, and the use of breast milk supplements, fortifiers and breast pumps. In addition, the mothers compared the advice they had been given by health care professionals about infant feeding or pumping.

In what phase have you transferred from bottle to breast? Is there any age/weight‐based guideline when you can try breastfeeding only? It is so much easier with a bottle, when you know for sure how much the baby is eating. Nevertheless, you can't perform test weighing at home, so how can I manage? (014)

Breastfeeding continuing to be a risk for the infant's well‐being

At home, despite their desire to breastfeed their infant, the mothers considered bottle‐feeding – preferably with expressed breast milk but also with formula – to be a safer method than breastfeeding, as it would ensure the infant would be getting enough milk. The mothers did not want to risk their vulnerable infants' well‐being; therefore, they prioritised their infant's weight gain over every other aspect of infant feeding. One solution to safeguarding the infant's weight gain at home for some breastfeeding mothers was weighing the infant before and after breastfeeding. However, this infant test weighing was not possible for all mothers. Based on the mothers' discussions, it seems that test weighing at home was not recommended in the NICU, but the reason for this was not clearly explained.

A further concern expressed by the mothers was that when an infant was used to suckling the bottle, he or she then usually had difficulties in suckling from the breast. One of the mothers' main problems was to get the infant properly latched. In this situation, the easiest solution was to continue with bottle‐feeding to ensure the weight gain and the health of the infant.

I think my milk supply is a little dried up. I already had mastitis and after that the amount of milk is about half of that what it was. We got the baby home today and I feel it's safer to bottle‐feed her, so I can see how much she is eating. The constant weight gain is so important. (008)

New opportunities at home

For some mothers, discharge from hospital was a new beginning and thus a new opportunity for breastfeeding. These highly motivated mothers consciously struggled towards successful breastfeeding and actively searched for solutions to their problems. Sometimes the only solution they needed was test weighing, despite it not being officially advised or encouraged. These mothers described increasing breastfeeding incrementally, first once a day, then twice a day and so forth, until they had reached their goal. Every step towards progress enhanced their self‐confidence in breastfeeding, creating a positive feedback loop.

We borrowed the scales from the child health clinic and I test weighed the baby before and after breastfeeding during the weekend. I found out that he was getting enough milk from the breast; so now I am breastfeeding exclusively. Yes! And today is the due date ☺ I wouldn't have had the courage to stop pumping and bottle‐feeding without the test weighing. They said in the NICU that they don't want to lend out scales. Luckily, my nurse in the child health clinic didn't know that ☺ (036)

Breastfeeding experience as part of being a mother

Finally, the mothers assimilated their breastfeeding experiences into their experiences of motherhood. They generally used the concepts of ‘successful’ or ‘unsuccessful’ breastfeeding experiences, although their definitions of ‘successful’ or ‘unsuccessful’ breastfeeding were not clear. Based on the discussions, it was understood that successful breastfeeding referred to breastfeeding according to the recommendations by Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, which are in concordance with the recommendations by World Health Organization (WHO) (WHO/UNICEF 2003). ‘Unsuccessful’ breastfeeding was usually described in terms of a shorter period, or a lack, of breastfeeding.

Being proud of successful breastfeeding

Based on the mothers' discussions, successful breastfeeding seemed to be very empowering: the mothers felt proud in achieving it. They considered successful breastfeeding as something to their own credit, as it was the result of a great deal of work and persistence from them. Mothers who were successful in breastfeeding felt satisfied with their motherhood, and both the mothers and their infants enjoyed breastfeeding.

They didn't provide much support or instructions for home. ‘You can breastfeed once a day for a start’. That was the only advice I got. It is purely based on my own persistence that she has been exclusively breastfed for 4 weeks. (025)

Disappointment in unsuccessful breastfeeding

Unsuccessful breastfeeding was associated with feelings of disappointment, failure and even shame and was explained with indefinable factors such as ‘the baby never learnt how to suckle the breast’ or ‘breastfeeding did not work out with us’. The mothers described their experiences of shame further: for example, that ‘it is embarrassing to buy formula’ and ‘you feel yourself a bad mother and unwomanly because breastfeeding is not succeeding’. Breastfeeding had been seen as an opportunity to compensate for an ‘unsuccessful’ pregnancy, but now this compensation was not realised. The mothers experienced feelings of guilt about their unsuccessful breastfeeding, but eventually they accepted it as part of their motherhood experience. These mothers often imagined a new opportunity for breastfeeding with a different baby in the future. Retrospectively, the mothers saw the infant's hospitalisation period from a different perspective, and sometimes they were able to identify the factors that led to the cessation or the decrease in their milk secretion, such as limitations and restrictions on breastfeeding in the NICU.

I just thought, because the pregnancy didn't work out according to the plan, and I feel guilty because of the preterm birth, breastfeeding would have been the thing to compensate. (024)

A proportion of the mothers were not even able to start breastfeeding, as they could not maintain lactation until the time that the infant was mature enough to suckle the breast. Abandoning breastfeeding at this stage was a very difficult decision, and one that the mothers also felt guilty about. In some cases, these feelings of guilt were increased by the questions and comments made by nurses about their breastfeeding. The mothers who struggled with this decision reported that they would have appreciated peer support at this time.

Discussion

Based on the findings of this qualitative study, the support for breastfeeding preterm infants in NICUs is not optimal. According to these mothers, many nurses considered breastfeeding fragile infants to be a risk to the infant's health and a factor that would delay discharge. This fostered some paradoxical elements in the nursing support, by emphasising breast milk over breastfeeding and placing too much responsibility for successful breastfeeding on the mothers at home. However, the mothers considered breastfeeding to be an important part of being a mother of a preterm infant.

The mothers also encountered some paradoxical elements when initiating lactation and breastfeeding in the hospital. The importance of breast milk was strongly emphasised and mothers sometimes felt pressured about lactating. Some of the mothers even experienced oppressive behaviour related to breastfeeding; their breastfeeding and pumping became a duty and the emotional aspects of this were forgotten, which Flacking et al. (2006) and Swanson et al. (2012) have also reported. Indeed, long‐term breast pumping may result in breast milk objectification, which has a negative impact on the overall breastfeeding experience (Sweet 2006). These paradoxical elements and varying support resulted in the mothers facing difficulties at home. According to the study by Murdoch & Franck (2012), when a preterm infant is discharged from hospital, their mother loses the support of the NICU nurses and so, at this point, their confidence in their parenting abilities may be low. Similarly, in this study, the mothers reported lacking the skills and knowledge to manage breastfeeding at home. Moreover, some of the counselling provided in the NICU could actually create more barriers to breastfeeding, making it even more difficult. Notably, regarding the nature of the peer‐support group, it is possible that mothers who actively participated in the group were also the ones with more negative experiences and thus do not represent ‘typical’ mothers of preterm infants. However, most of the mothers reported a reliance on the nurses' expertise about all aspects concerning their infants, a result consistent with earlier studies (Flacking et al. 2006; Swanson et al. 2012).

It seems that nurses in NICUs have varying skills in breastfeeding counselling and also varying attitudes towards it, according to the participating mothers. Staff value early discharge from hospital because home is seen as the natural and best environment for the infants. Breastfeeding was often seen as a threat to a preterm infant's health and, by implication, for early discharge. If staff were to better understand the value of breastfeeding for infant development, it would cease being a threat to early discharge and rather become an integral part of planning for discharge. There is some evidence that breastfeeding is a more physiological feeding method for preterm infants compared with bottle‐feeding; for example, occurrences of oxygen desaturation and apnoea are reportedly higher during bottle‐feeding than during breastfeeding (Chen et al. 2000). Furthermore, energy expenditure did not differ between breastfed and bottle‐fed infants born after 32 gestational weeks in a study by Berger et al. (2009). Therefore, the initiation of oral feeding should not be based on gestational weeks at birth or post‐conceptional age, but instead should be guided by careful observation and assessment of the infant's individual feeding readiness behaviour (Jones 2012). Thus, when the preterm infant is stable enough to breathe, suck and swallow, the primary feeding method could be breastfeeding, not bottle‐feeding (Spatz 2004). In some NICUs in Denmark, the use of bottle‐feeding is already restricted (Maastrup et al. 2012). This avoidance of bottle‐feeding would also better support a mother's milk supply and her efforts to pump.

This highlights the fact that NICU nurses have a responsibility to maintain an adequate level of knowledge and skills about breastfeeding counselling and support, underlining the need for continuous further education for all nurses. Such education should contain information about the benefits of breastfeeding, the preterm infant's ability to be breastfed and the support needed for the transition from hospital to home. One breastfeeding promotion programme in NICUs in Italy has shown very positive effects on exclusive breastfeeding rates. The programme included information and support by a lactation consultant, the free use of electric breast pumps and a course for nursing staff. (Dall'Oglio et al. 2007.) In addition to increasing knowledge, nurses' attitudes towards breastfeeding have to be carefully observed, as these attitudes are as important as knowledge for supporting mothers (Bernaix 2000).

In addition to the behaviour of the hospital staff, a supportive environment is essential for the successful breastfeeding of preterm infants (Flacking et al. 2006). In a study by Wataker et al. (2012), preterm infants provided with the opportunity to be with their parents 24 h a day were breastfed more frequently after 3 months than the control group infants. However, not all NICUs provide optimal environmental support for breastfeeding (Maastrup et al. 2012). The possibility for ‘rooming‐in’ with the preterm infant would facilitate and support lactation and milk pumping, and some modified versions of the WHO Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative for preterm infants have been developed in the United States (Spatz 2004), Brazil (do Nascimento & Issler 2005) and Sweden (Hedberg Nyqvist & Kylberg 2008). However, most of the existing NICUs in Finland do not provide parents with the opportunity for round‐the‐clock rooming‐in with their infant.

It has been suggested that preterm infants should be given the opportunity to suckle the breast as soon as they are weaned from any respiratory support. With kangaroo care, it is possible to expose the preterm infant to the mother's breast and breast milk as early as possible. Kangaroo care provides an excellent opportunity for an infant to suckle the breast without any nutritional goals. This non‐nutritive sucking improves the transition to nutritive breastfeeding; for example, drops of milk can be manually expressed onto the infant's lips (Spatz 2004). Kangaroo care has been shown to particularly promote breastfeeding in very preterm infants (gestational age <32 weeks) (Flacking et al. 2011). If the infant is allowed to suckle the breast according to her or his own breastfeeding behaviour, the early establishment of exclusive breastfeeding is possible, and no limitations to the duration of the breastfeeding sessions are then needed (Hedberg Nyqvist & Ewald 1999). Furthermore, Rozé et al. (2012) found an interesting association between breastfeeding and very preterm infants in that even when their initial weight gain was suboptimal, the neurodevelopment of very preterm infants was better when they had been breastfed, a further factor to support the encouragement of breastfeeding preterm infants.

Merely providing care in NICUs that is favourable for breastfeeding is not enough; the care following hospitalisation also needs to be supportive and skilful. In Finland, nearly all infants visit community child health clinics regularly. Therefore, public health nurses in child health clinics must have profound knowledge about the breastfeeding of preterm infants in order to support mothers in breastfeeding after discharge from the NICUs. The use of test weighing after discharge should be considered more frequently because it seemed that some mothers of preterm infants benefit from using the scales at home. Test weighing will not be the best solution for all mothers because some mothers may experience it as stressful additional routine (Flacking et al. 2006), but the possibility of test weighing at home should be more readily available. In hospital settings, test weighing has shown good results when preterm infants are transferring to exclusive breastfeeding (Funkquist et al. 2010).

In addition to support from public health nurses in child health clinics, peer support through social media seems to be a good and accessible source of information and support after hospital discharge. Generally speaking, the Finnish population are active users of the Internet and of social media. Almost 100% of people aged 25–44 use the Internet, and a major proportion of these users are engaged in some kind of social network service (Official Statistics of Finland 2012). In this study, the participating mothers sought answers to any unclear issues from the peer‐support group. All the questions posted were answered, and the use of social media made answering or commenting possible at any time of the day or night, regardless of the participants' geographical distance. In addition to answering questions, the mothers supported each other in managing conflicting advice. Cowie et al. (2011) have also reported that Internet‐based peer‐support groups may be an important resource for breastfeeding mothers in need of support or information.

Breastfeeding is a very sensitive and complex aspect of motherhood (Marshall et al. 2007), and something that needs to be recognised as an important and empowering part of being a mother of a preterm infant. In this study, the mothers expressed feelings of guilt surrounding their preterm births and felt that breastfeeding, if it were to succeed, would be a way for them to compensate for the inadequacy of the pregnancy. Furthermore, in the study by Swanson et al. (2012), expressing and pumping breast milk symbolised a deeper contact between a mother and her preterm infant. During an infant's hospitalisation, mothers are often concerned about their milk supply (Dowling et al. 2012) – even 20 years ago, the mothers of preterm infants had outlined that their main concern after discharge was whether the infant was getting enough milk (Kavanaugh et al. 1995). These same concerns were still relevant to the mothers in this study. In a study by Larsen & Kronborg (2013), the mothers of full‐term babies had also experienced anxiety connected to unsuccessful breastfeeding. Thus, mothers who are not able to breastfeed need empathy and support from health care professionals. According to a study by Williamson et al. (2012), breastfeeding is considered an essential part of motherhood and breastfeeding difficulties may have problematic implications for maternal identity. The results presented here also show that the mothers connected their disappointment over unsuccessful breastfeeding with their feelings of being a mother.

To allow for more preterm infants to be successfully breastfed, the primary target for the future is the development and standardisation of the breastfeeding counselling and support given from the time of admission in an NICU. Firstly, kangaroo care and closeness between the mother and her infant should be connected more clearly to breastfeeding. Also, families require particular support for breastfeeding at the time of discharge; NICU staff should thus provide mothers with possible solutions for common problems concerning breastfeeding at home. Public health nurses in child health clinics should actively and systematically support mothers in their efforts to breastfeed. Furthermore, additional support for mothers of preterm infants could be available, for example, through Internet‐based peer‐support groups led by a midwife to support breastfeeding and promote the sharing of experiences. In future research, mothers' experiences of using such groups should thus be further explored. In addition, it would be important to understand the implication of the attitudes of NICU nurses and unit culture to breastfeeding in more depth.

Strengths and limitations

This study had some limitations that are discussed here in relation to credibility, dependability and transferability (Graneheim & Lundman 2004). Regarding credibility, the first author, who has previously worked as a midwife, acted as the breastfeeding counsellor in the social media‐based peer‐support group. Therefore, this might have influenced the credibility of the data analysis. However, she was aware of these issues and constantly strived to avoid any presuppositions influencing the results. The credibility of the analysis was improved by the participation of the co‐authors who were also familiarised with the raw data and who critically reviewed the analysis at every phase. Representative quotations from the original data have been presented here to enhance the credibility. Regardless of the small number of participating mothers, data saturation was reached, which was realised as repetitive discussion topics. The data were rich and the study produced some new knowledge that has not been previously reported.

Concerning dependability, the questions presented by the midwife in the peer‐support group were the same for all the participants, and were delivered simultaneously. They worked only as stimulants for the discussions and were not aimed to manipulate their content. However, there is a possibility that the presence of the midwife inhibited some mothers in expressing their opinions or sharing their experiences, or that some areas of interests were missed because the group was midwife‐led. It is also possible that the midwife, rather than the participating mothers, initiated themes such as breast milk before breastfeeding and kangarooing; however, the mothers themselves created the contents of these discussions. Thus, a deeper understanding of these phenomena might have been provided through personal interviews with the mothers. The data collection period was almost 2 years, and therefore, the first mother had a different starting point in the group than did the 30th mother. In the hospital, the breastfeeding guidance did not change significantly during the data collection period. The data analysis was conducted over quite a short time period, requiring very intensive analysis and close cooperation between the research group. Thematic analysis was a functional method for the analysis because our interest was in the content of the discussions. Other methods, such as conversation analysis or discourse analysis, could possibly have provided different results.

The transferability of the results is limited because breastfeeding counselling is associated with hospital policies and culture. Although the results are from a small area in Finland, they provide us with a good idea of how breastfeeding support and the breastfeeding of preterm infants might be experienced by mothers.

Conclusions

The mothers of preterm infants faced many challenges related to breastfeeding in hospital and at home after discharge. The mothers encountered paradoxical elements related to breastfeeding and varying nurse support. The staff emphasised breast milk over breastfeeding, which led on some level to breast milk objectification and breastfeeding becoming more of a duty than a mutual pleasure between mother and infant. Despite such challenges, the mothers considered breastfeeding to be an important part of being a mother of a preterm infant. More attention should be paid not only to the breastfeeding counselling in the NICU but also to the attitudes of NICU staff. Breastfeeding peer‐support groups utilising social media may be a good channel for mothers to access necessary encouragement and support.

Source of funding

This study was supported by Finnish Doctoral Network in Nursing Science.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributions

All four named authors contributed to all aspects of the research and writing of this journal article.

Niela‐Vilén, H. , Axelin, A. , Melender, H.‐L. , and Salanterä, S. (2015) Aiming to be a breastfeeding mother in a neonatal intensive care unit and at home: a thematic analysis of peer‐support group discussion in social media. Matern Child Nutr, 11: 712–726. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12108.

References

- Ahmed A.H. & Sands L.P. (2010) Effect of pre‐ and postdischarge interventions on breastfeeding outcomes and weight gain among premature infants. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing 39, 53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson J.W., Johnstone B.M. & Remley D.T. (1999) Breast‐feeding and cognitive development: a meta‐analysis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 70, 525–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger I., Weintraub V., Dollberg S., Kopolovitz R. & Mandel D. (2009) Energy expenditure for breastfeeding and bottle‐feeding preterm infants. Pediatrics 124, e1149–e1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernaix L.W. (2000) Nurses' attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioral intentions toward support of breastfeeding mothers. Journal of Human Lactation 16, 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonet M., Blondel B., Agostino R., Combier E., Maier R.F., Cuttini M. et al (2011) Variations in breastfeeding rates for very preterm infants between regions and neonatal units in Europe: results from the MOSAIC cohort. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition 96, F450–F452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V. & Clarke V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Callen J. & Pinelli J. (2005) A review of the literature examining the benefits and challenges, incidence and duration, and barriers to breastfeeding in preterm infants. Advances in Neonatal Care 5, 72–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.‐H., Wang T.‐M., Chang H.‐M. & Chi C.‐S. (2000) The effect of breast‐ and bottle‐feeding on oxygen saturation and body temperature in preterm infants. Journal of Human Lactation 16, 21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowie G.A., Hill S. & Robinson P. (2011) Using an online service for breastfeeding support: what mothers want to discuss. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 22, 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall'Oglio I., Salvatori G., Bonci E., Nantini B., D'Agostino G. & Dotta A. (2007) Breastfeeding promotion in neonatal intensive care unit: impact of a new program toward a BFHI for high‐risk infants. Acta Paediatrica 96, 1626–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do Nascimento M.B.R. & Issler H. (2005) Breastfeeding the premature infant: experience of a baby‐friendly hospital in Brazil. Journal of Human Lactation 21, 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodrill P., Donovan T., Cleghorn G., McMahon S. & Davies P.S.W. (2008) Attainment of early feeding milestones in preterm neonates. Journal of Perinatology 28, 549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donath S.M. & Amir L.H. (2008) Effect of gestation on initiation and duration of breastfeeding. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition 93, F448–F450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling D.A., Blatz M.A. & Graham G. (2012) Mothers' experiences expressing breast milk for their preterm infants. Does NICU design make a difference? Advances in Neonatal Care 12, 377–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flacking R., Ewald U., Nyqvist K.H. & Starrin B. (2006) Trustful bonds: a key to ‘becoming a mother’ and to reciprocal breastfeeding. Stories of mothers of very preterm infants at a neonatal unit. Social Science & Medicine 62, 70–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flacking R., Ewald U. & Wallin L. (2011) Positive effect of kangaroo mother care on long‐term breastfeeding in very preterm infants. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing 40, 190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flacking R., Nyqvist K.H. & Ewald U. (2007) Effects of socioeconomic status on breastfeeding duration in mothers of preterm and term infants. European Journal of Public Health 17, 579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flacking R., Nyqvist K.H., Ewald U. & Wallin L. (2003) Long‐term duration of breastfeeding in Swedish low birth weight infants. Journal of Human Lactation 19, 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funkquist E.‐L., Tuvemo T., Jonsson B., Serenius F. & Nyqvist K.H. (2010) Influence of test weighing before/after nursing on breastfeeding in preterm infants. Advances in Neonatal Care 10, 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim U.H. & Lundman B. (2004) Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today 24, 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannula L. (2003) Perceptions of Breastfeeding and the Outcomes of Breastfeeding. (Finnish, English abstract.) Dissertation, Annales Universitatis Turkuensis C 195. University of Turku: Finland.

- Hannula L., Kaunonen M., Koskinen K. & Tarkka M.‐T. (2010) Breastfeeding Support for Mothers and Families during Pregnancy and Birth and After – A Clinical Practice Guideline Nursing Research Foundation: Hotus. Available at: http://www.hotus.fi/system/files/BREASTFEEDING_all.pdf (Accessed 26 June 2013).

- Hedberg Nyqvist K. (2008) Early attainment of breastfeeding competence in very preterm infants. Acta Paediatrica 97, 776–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedberg Nyqvist K. & Ewald U. (1999) Infant and maternal factors in the development of breastfeeding behaviour and breastfeeding outcome in preterm infants. Acta Paediatrica 88, 1194–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedberg Nyqvist K. & Kylberg E. (2008) Application of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative to neonatal care: suggestions by Swedish mothers of very preterm infants. Journal of Human Lactation 24, 252–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman H. & Schanler R.J. (2006) Benefits of maternal and donor human milk for premature infants. Early Human Development 82, 781–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill P.D., Hanson K.S. & Mefford A.L. (1994) Mothers of low birthweight infants: breastfeeding patterns and problems. Journal of Human Lactation 10, 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonen R., Ruohotie P., Ezeonodo A., Mikkola K. & Koskinen K. (2012) Preterm Infants, Initiation of Breastfeeding (Finnish). Finnish National Institute for Health and Welfare. Available at: http://www.thl.fi/fi_FI/web/lastenneuvola-fi/tietopaketit/imetys/keskoset/aloittaminen (Accessed 19 June 2013).

- Jaeger M.C., Lawson M. & Filteau S. (1997) The impact of prematurity and neonatal illness on the decision to breast‐feed. Journal of Advanced Nursing 25, 729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L.R. (2012) Oral feeding readiness in the neonatal intensive care unit. Neonatal Network 31, 148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh K., Mead L., Meier P. & Mangurten H.H. (1995) Getting enough: mothers' concerns about breastfeeding a preterm infant after discharge. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing 24, 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen J.S. & Kronborg H. (2013) When breastfeeding is unsuccessful – mothers' experiences after giving up breastfeeding. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 27, 848–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maastrup R., Norby Bojesen S., Kronborg H. & Hallström I. (2012) Breastfeeding support in neonatal intensive care: a national survey. Journal of Human Lactation 28, 370–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J.L., Godfrey M. & Renfrew M.J. (2007) Being a ‘good mother’: managing breastfeeding and merging identities. Social Science & Medicine 65, 2147–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merewood A., Chamberlain L.B., Cook J.T., Philipp B.L., Malone K. & Bauchner H. (2006) The effect of peer counselors on breastfeeding rates in the neonatal intensive care unit. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine 160, 681–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch M.R. & Franck L.S. (2012) Gaining confidence and perspective: a phenomenological study of mothers' lived experiences caring for infants at home after neonatal unit discharge. Journal of Advanced Nursing 68, 2008–2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Official Statistics of Finland (2012) Use of Information and Communications Technology by Individuals ISSN=2323‐2854. 2012. Statistics Finland: Helsinki. Available at: https://www.tilastokeskus.fi/til/sutivi/2012/sutivi_2012_2012-11-07_tie_001_en.html (Accessed 26 June 2013).

- Quigley M., Henderson G., Anthony M.Y. & McGuire W. (2007) Formula milk versus donor breast milk for feeding preterm or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4)CD002971. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002971.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozé J.‐C., Darmaun D., Boquien C.‐Y., Flamant C., Picaud J.‐C., Savagner C. et al (2012) The apparent breastfeeding paradox in very preterm infants: relationship between breast feeding, early weight gain and neurodevelopment based on results from two cohorts, EPIPAGE and LIFT. BMJ Open 2, e000834. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spatz D.L. (2004) Ten steps for promoting and protecting breastfeeding for vulnerable infants. Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing 18, 385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson V., Nicol H., McInnes R., Cheyne H., Mactier H. & Callander E. (2012) Developing maternal self‐efficacy for feeding preterm babies in the neonatal unit. Qualitative Health Research 22, 1369–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet L. (2006) Breastfeeding a preterm infant and the objectification of breast milk. Breastfeeding Review 14, 5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uusitalo L., Nyberg H., Pelkonen M., Sarlio‐Lähteenkorva S., Hakulinen‐Viitanen T. & Virtanen S. (2012) Infant Feeding in Finland 2010 National Institute for Health and Welfare THL, Report 8/2012. (Finnish, English summary). Available at: http://www.thl.fi/thl-client/pdfs/ee5adaff-90c4-4005-a3ad-77887817f091 (Accessed 26 June 2013).

- Vohr B.R., Poindexter B.B., Dusick A.M., McKinley L.T., Higgins R.D., Langer J.C. & Poole W.K. (2007) Persistent beneficial effects of breast milk ingested in the neonatal intensive care unit on outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants at 30 months of age. Pediatrics 120, e953–e959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wataker H., Meberg A. & Nestaas E. (2012) Neonatal family care for 24 hours per day. Effects on maternal confidence and breast‐feeding. Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing 26, 336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO/UNICEF (2003) Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding World Health Organization: Geneva. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241562218.pdf (Accessed 19 June 2013).

- Williamson I., Leeming D., Lyttle S. & Johnson S. (2012) ‘It should be the most natural thing in the world’: exploring first‐time mothers' breastfeeding difficulties in the UK using audio‐diaries and interviews. Maternal & Child Nutrition 8, 434–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariassen G., Faerk J., Grytter C., Esberg B.H., Juvonen P. & Halken S. (2010) Factors associated with successful establishment of breastfeeding in very preterm infants. Acta Paediatrica 99, 1000–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]