Abstract

Malnutrition in children under 5 years of age is pervasive in Ethiopia across all wealth quintiles. The objective of this study was to determine the willingness to pay (WTP) for a week's supply of Nutributter® (a lipid‐based nutrient supplement, or LNS) through typical urban Ethiopian retail channels. In February, 2012, 128 respondents from 108 households with 6–24‐month‐old children had the opportunity to sample Nutributter® for 2 days in their homes as a complementary food. Respondents were asked directly and indirectly what they were willing to pay for the product, and then participated in market simulation where they could demonstrate their WTP through an exchange of real money for real product. Nearly all (96%) of the respondents had a positive WTP, and 25% were willing to pay the equivalent of at least $1.05, which we calculated as the likely minimum, unsubsidised Ethiopian retail price of Nutributter® for 1 week for one child. Respondents willing to pay at least $1.05 included urban men and women with children 6–24 months old from low‐, middle‐ and high‐wealth groups from four study sites across three cities. Additionally, we estimated the initial annual market size for Nutributter® in the cities where the study took place to be around $500 000. The study has important implications for retail distribution of LNS in Ethiopia, showing who the most likely customers could be, and also suggesting why the initial market may be too small to be of interest to food manufacturers seeking profit maximisation.

Keywords: willingness to pay, Nutributter®, Lipid‐based Nutrient Supplement (LNS), malnutrition, Ethiopia, retail distribution

Introduction

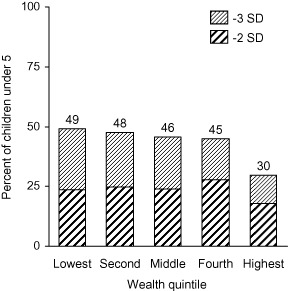

In Ethiopia, 44% of children under 5 years old are stunted, 29% are underweight and 10% are wasted [Central Statistical Agency (Ethiopia) and ICF International 2012]. However, these indicators of malnutrition are not only limited to resource‐poor households. Stunting of children (below −2 standard deviations in z‐scores) is pervasive in Ethiopia across wealth quintiles, including more than a third of children in the top wealth quintiles (Fig. 1). Even within urban areas, stunting is 22% in urban Addis Ababa, 31% in urban Tigray, and 30% in urban Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People's Region (SNNPR) [Central Statistical Agency (Ethiopia) and ICF International 2012]. While international programmes have understandably been focused on resource‐poor families, there is clearly a need for better nutrition among the middle‐ and upper‐wealth segments of the population as well. Direct‐to‐consumer, retail sales may be a viable distribution means to address childhood malnutrition across wealth quintiles, but hinges on consumer demand and willingness to pay (WTP) for the product.

Figure 1.

Children with low height‐for‐age by wealth. SD, standard deviation.

Rather than assessing WTP across all Ethiopian populations, the study focused first on four urban sites, where private sector retail activities would be most likely to initiate. If urban WTP were proven sufficient to support a market, future study could expand into more rural areas.

It is crucial to assess the retail potential of complementary foods for several reasons. First, the malnutrition problem is far larger than what donor‐driven and government programmes can tackle alone. Roughly one‐third of children under 5 years of age in the developing world are stunted (Black et al. 2008) and most will never be reached by free food programmes. Second, our respondents noted that urban households primarily look to retail shops for their baby food needs. Many of these families neither want nor need free food, so a retail approach may be more easily incorporated into everyday life. Third, private sector products can often travel further and faster into certain communities than products given away by the government or international programmes. Finally, profitable, retail approaches have the potential to be donor‐independent, as evidenced by the variety of baby foods currently sold in urban shops. So long as there is a competitive rate of return, the retail channel will sustain itself, regardless of the ebbs and flows of donor funds and political re‐direction.

There are many retail products with potential to help alleviate childhood malnutrition, but we have focused on a food‐based strategy, specifically using lipid‐based nutrient supplements (LNS). Healthy growth can only occur when all of the essential nutrients are provided in the required amounts at the same time. LNS has the advantage of providing both the micronutrients required for healthy growth, and also adequate macronutrients including high‐quality protein and essential fatty acids, which may not be readily available in common cereal‐based complementary foods. There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that LNS may be particularly useful in the prevention of early childhood malnutrition (Kuusipalo et al. 2006; Adu‐Afarwuah et al. 2008; Dewey et al. 2009; Phuka et al. 2009).

To date, LNS have been almost exclusively distributed via donor‐funded free distribution programmes to treat moderate and severe malnutrition. Little is known about their private sector retail potential for preventive purposes, making this study particularly relevant. As the evidence base for LNS grows stronger, there will be increasing interest in expanding the reach of the product, and substantial need to quantify its private sector retail potential through an examination of WTP across potential customer groups.

This paper was a first step in describing the private sector retail potential of Nutributter® by (1) assessing WTP using multiple methods; (2) using WTP data to estimate the potential market size; and (3) using WTP data to estimate the subsidy required to reach a larger portion of families in the study areas, and potentially make LNS attractive to private producers.

Nothing short of a genuine market launch can determine WTP with certainty, but we use three low‐cost, low‐risk methods in order to approximate WTP without a market launch: a direct method, an indirect method, and an experimental method. We use the simplest direct method, whereby respondents are asked an open‐ended question regarding their WTP for LNS. Several others have used this method for LNS, including Tripp et al. (2011) and several unpublished reports. We then use Van Westerdorp's Price Sensitivity Meter (PSM) as an indirect method to add nuance to the direct method in that it elicits a range of prices that respondents would consider1. PSM is a common tool used in commercial (as opposed to academic) consumer research. As in the direct method, PSM is a purely hypothetical exercise. Finally, we use an experimental method to elicit WTP in a context where a genuine trade can take place, grounding data collection in a context that more closely resembles the actual marketplace. Researchers are increasingly using experimental methods to elicit WTP for health and nutrition products (Masters & Sanogo 2002; Hoffmann et al. 2008; De Groote et al. 2010a,b; Dupas 2010; Berry et al. 2011; Adams et al. 2011). Well‐executed experimental methods elicit respondent WTP in a context where there is something of actual value to be gained or lost, thereby creating greater incentive to provide more careful, honest answers.

This study builds upon the existing corpus in that it is the first to compare direct, indirect, and experimental methods in the assessment of WTP for LNS in Ethiopia. We also compare WTP across multiple sites, wealth groups and both genders. We then compare the assessed WTP to projected retail costs of LNS, and estimate the initial potential market size and level of subsidy required to serve the population.

Key messages

Stunting in children under 5 years of age is pervasive across all income quintiles in Ethiopia, suggesting that nutritional interventions are also relevant for relatively wealthy families who may already purchase fortified complementary food products for their 6–24‐month‐old children.

Stated willingness to pay (WTP) is not correlated with actual WTP in a market simulation where participants exchange real money for real product.

In market simulations, the majority (96%) of families in our study expressed a positive WTP real money for Nutributter®.

Nearly one‐fourth of families (25%) were willing to pay $1.05 or more for a week's supply of Nutributter®, suggesting that these families would readily buy an unsubsidised retail product.

Respondents willing to pay the unsubsidised price (or more) came from all three wealth classes, both genders, and the four urban sample sites.

Materials and methods

Choice of LNS

Nutributter® is the most studied LNS for complementary feeding, and the most mature product in terms of its packaging, costs and international standards compliance. The product is a ready‐to‐eat paste of peanuts, sugar, vegetable fat, skimmed milk powder, maltodextrin and whey, enriched with a vitamin and mineral complex. It comes in 20‐g sachets, packaged into sets of seven sachets (sometimes called ‘strings’), suitable for one week's consumption per child. While Nutriset manufactured the study samples in France, Nutriset's Plumpy'Field network has the capacity to produce the product in several other locations around the world, including Ethiopia. Nutributter® is manufactured in compliance with international standards (ISO 22000:2005), recommended by the Codex Alimentarius (HACCP method), and compliant with the Recommended International Code of Hygienic Practice for Foods for Infants and Children of the Codex Alimentarius Standard CAC/RCP 21–1979.

Locations

Consumption of packaged complementary foods is not common outside Ethiopian cities. An unpublished Alive & Thrive survey of nearly 3000 rural respondents from SNNPR and Tigray showed that over 90% of respondents had never purchased any packaged complementary food. To begin assessing WTP, therefore, we focused on three of the country's major cities, hypothesising that urban populations would be most likely to buy LNS products. We also hoped to be able to detect any dramatic regional variation in WTP. The four sites studied were in central Addis Ababa, peripheral Addis Ababa, Hawassa, and Mekelle. Addis Ababa is at least 10 times larger than the next most populous city, and would be an obvious choice for launching a commercial product. Hoping to detect differences in WTP between the central and periphery areas of the city, we sampled respondents from both. Mekelle is Ethiopia's second largest city, located in the northern region of Tigray. Hawassa is the largest city within SNNPR.

Respondents

The study collected responses from 108 households (128 parents) with children aged 6–24 months across the four sites. The convenience sample size of 128 respondents was a function of the time and resources available, with the objective of obtaining indicative rather than conclusive results. At each site, a local health extension worker (HEW) identified homes with children 6–24 months of age. Study staff met potential respondents at their household in order to introduce the study and interviewed participants to determine eligibility. Prospective participants had to be home with their child when the data collectors arrived, have partial or full decision making on the baby's diet, and sign an informed consent agreement. Although no potential respondents were excluded, exclusion criteria included prior participation in market research on complementary foods, households with allergies to peanuts or other Nutributter® ingredients, and respondents under age 18. In the recruitment process, we focused on studying a cross‐section of wealth in each area, as determined by visible assets. In order to establish the segmentation, we did a factor analysis of 2005 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) [Central Statistical Agency (Ethiopia) and ORC Macro 2006] data in the relevant geography to determine the most important indicators of wealth (e.g. housing construction materials, home appliances, etc.) We then matched participants to a specific wealth group. Depending on their visible assets, respondents were categorised into lower, middle and upper wealth segments. In each region, the study staff collected responses from mothers of lower, middle and upper wealth segments, as well as fathers in the middle wealth segment. At each study site, data collectors also identified local wholesalers and retailers of baby foods. At each one, data collectors demonstrated the product and administered a questionnaire on product perceptions and potential buying and selling price points. We used this data to build up the likely retail price of the product.

Product placement and qualitative data collection

A single team of 10 trained, trilingual data collectors with previous research experience worked in all four sites, interacting with respondents in Amharic and Tigrinya as applicable and reporting back in English. In most cases, data collectors were matched with respondents of the same sex. Once respondents gave informed consent to participate in the study, the staff used a set of survey tools and scripts to demonstrate the use of LNS, opening a sachet and tasting it in front of the parent before offering it to the parent and child to try as well. Staff described the potential nutritional benefits of LNS and then instructed parents to mix the Nutributter® with their child's normal food, offering half a sachet (10 g) as part of the morning meal and half as part of the evening meal. Staff then left two new, unopened sachets with the families and made a follow‐up appointment to observe the child consuming the product for later the same day or the following day in the home. After a 2‐day product placement, staff returned to the family's home to administer a qualitative questionnaire on product perceptions, including the caregiver's perception of product quality, ease of use and nutritional benefit as well as the baby's acceptance or rejection of the product. All responses were recorded directly on the survey tool, in the form of a numerical score on a Likert scale.

Assessment of stated WTP

During this one‐on‐one interaction, study staff also asked for the respondent's WTP with a single numerical response for their ideal price. We call this hypothetical value the ‘stated WTP’. In addition, we supplemented the directly stated WTP with an indirect assessment, using Van Westendorp's PSM (Van Westendorp 1976).

Assessment of actual WTP

At the conclusion of the structured interview, one or both parents were invited to participate in a ‘market simulation’ workshop with other study participants the next day. Upon arrival at the market simulation location (typically a room at the local health centre), respondents were given an envelope containing 50 Ethiopian Birr (ETB), the equivalent of $2.85, as compensation for their participation in the study. The study staff engaged the full group in a round of introductions and explained the planned activities. Participants were then separated by wealth status as previously determined in the selection surveys, and joined their peer group (low, medium or high wealth) for a market simulation. Group sizes ranged from 5 to 12 participants.

The market simulation then followed a variation of the Becker–Degroot–Marschak (BDM) structure (Becker et al. 1964) whereby the participant submits a bid for a product of unknown price. The price is then determined randomly. If the bid is greater than or equal to the price, money is exchanged for product. If the bid is lower than the price, no transaction takes place, and the money is returned to the participant. In this way, participants express their WTP exchanging real money for real product.

In order to explain the process to participants, the facilitator ran a market simulation for a common Ethiopian brand of bar soap known as B‐29. Participants and study staff sat in a circle such that each study staff member had a participant on each side. This was typically the same staff member who had done the in‐home visit with that respondent in the preceding days. Participants were asked to imagine that a bar of B‐29 soap was for sale in a nearby market at an unknown price. The price would be determined randomly, by drawing a pre‐printed price from coffee cup filled with randomly generated prices. The facilitator drew several such prices out of a coffee cup to show that the market prices drawn were unknown ahead of time and should not influence the actual bids. The facilitator then explained that each participant's ‘trusted friend’ (role‐played by the project staff member at their side) was going to the market and could buy a bar of soap for them, but would need the cash up front. Participants were asked to discreetly give the friend exactly as much cash as they would be willing to spend for that bar of soap – this was their bid. The study staff held the cash in hand and recorded the amount while the facilitator drew the market price from the cup. If the price was higher than the bid, the study staffed returned the money. If the price was at or lower than the bid, the staff gave the participant a bar of soap and change as applicable. After a practice round, the group participated in a binding round where participants bid for and bought soap. The project staff used this soap exercise to confirm their participants' comprehension of the market simulation process.

Prior to the final market simulation round using a week's supply of Nutributter® (e.g. seven sachets packaged together), the facilitator drew sample prices of Nutributter® from a second coffee cup. Several prices were drawn to show a wide range from approximately 5–50 ETB ($0.29–$2.85). The facilitator conducted a practice round and then a binding round for 1 week's supply of Nutributter®, with project staff recording bids from each participant. The binding bid using real money for real product was recorded as the ‘actual WTP’ because the respondent was willing to exchange real money for real product at that moment. Adams et al. (2011) discuss the theoretical basis for this approach, which they also used for LNS products in Ghana.

Results

Respondents

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the 128 respondents.

Table 1.

Respondent characteristics by wealth and gender (n = 128)

| Asset wealth | Low(%) | Medium (%) | High (%) | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | Female | Male | Female | |

| Central addis | 7.0 | 7.0 | 4.7 | 2.3 | 21.0 |

| Peripheral addis | 8.6 | 4.7 | 6.3 | 3.9 | 23.5 |

| Mekelle | 7.0 | 8.6 | 4.7 | 3.9 | 24.2 |

| Hawassa | 6.3 | 7.8 | 9.4 | 7.8 | 31.3 |

| Sole decision maker on baby foods | 7.0 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 5.5 | 18.0 |

| Child consumes food especially for children | 9.4 | 14.8 | 15.6 | 10.9 | 50.8 |

| Only one child in household | 9.4 | 14.8 | 18.8 | 10.9 | 53.9 |

| Some secondary education or better | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 8.6 | 55.5 |

| Fully or partially employed | 7.0 | 8.6 | 16.4 | 3.9 | 35.9 |

| Buy food from supermarkets (vs. kiosks) | 2.3 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 7.0 | 14.8 |

WTP results

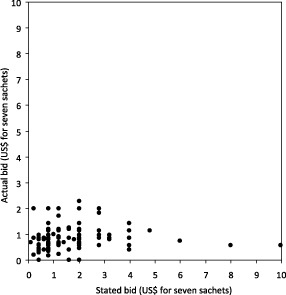

While stated WTP ranged from roughly $0.10 to $10.00 for a week's supply of LNS, actual bids ranged from zero to $2.28. With a correlation coefficient of 0.05, there was no evidence (P = 0.58) of a relationship between stated and actual WTP (Fig. 2). This finding has important implications for future assessments of WTP for LNS, in that relying on stated WTP is not at all predictive of actual WTP.

Figure 2.

Stated vs. actual bid for one week's supply of Nutributter®.

The Van Westerdorp PSM was also inconsistent with actual WTP. The PSM yielded a price range of $1.00–$2.00, and an optimal price of about $1.30. During the market simulation, only 9% of respondents bid at or above $1.30, suggesting that reliance on the PSM method would have priced beyond the WTP of 91% of the market.

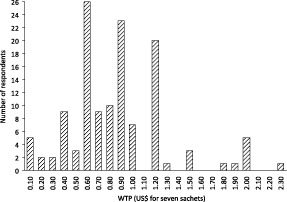

In the market simulation, the median actual bid was around $0.80, and a histogram shows pronounced spikes in frequency at 10, 15, and 20 Ethiopian Birr ($0.57, $0.86 and $1.14, respectively) which are convenient denominations of Ethiopian currency (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Actual bids for one week's supply of Nutributter®. WTP, willingness to pay.

In order to better understand the determinants of WTP, we used multivariate linear regression to estimate actual bids while controlling for potential confounding factors. We incorporated demographic, geographic and socioeconomic status information while examining the impact of respondent perceptions of product health and safety, number of children in the household, shopping preferences, stated bid, and enthusiasm for the product. This enthusiasm was defined as assigning the highest survey rating for Nutributter®'s taste, colour, texture, smell, preparation ease and package design. A priori, we hypothesised that higher wealth, education and enthusiasm along with geographic region would impact WTP. Table 2 shows the multivariate regression results. The parent's employment status was the most significant predictor of WTP differences. Surprisingly, parents who were employed part or full‐time produced a WTP $0.23 lower (P = 0.02) on average than unemployed parents of otherwise similar backgrounds. Similarly, those with full grocery decision power tended to bid $0.19 lower (P = 0.10) than parents who shared decision making. Perhaps parents with a greater awareness of their food budget were more reserved in their WTP. No other predictors of WTP were significant at the 5% level.

Table 2.

Multivariate regression of actual willingness to pay

| Estimate | 95% CI | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 0.81 | 0.43 to 1.19 | 0.00 |

| Addis periphery | 0.03 | −0.24 to 0.30 | 0.82 |

| Mekele | 0.04 | −0.22 to 0.31 | 0.74 |

| Hawassa | 0.12 | −0.13 to 0.37 | 0.36 |

| Medium wealth | −0.11 | −0.32 to 0.10 | 0.32 |

| High wealth | 0.10 | −0.16 to 0.36 | 0.47 |

| Male parent | −0.01 | −0.22 to 0.21 | 0.95 |

| Health perception very believable | −0.05 | −0.21 to 0.11 | 0.52 |

| Highest safety perception | 0.01 | −0.16 to 0.17 | 0.94 |

| Highest enthusiasm | 0.10 | −0.06 to 0.26 | 0.24 |

| Stated bid (dollars) | 0.03 | −0.03 to 0.09 | 0.34 |

| Full grocery decision power | −0.19 | −0.41 to 0.03 | 0.10 |

| Eats special children's food | 0.14 | −0.04 to 0.33 | 0.13 |

| Secondary/college education | 0.04 | −0.14 to 0.21 | 0.70 |

| Employed (full or part‐time) | −0.23 | −0.41 to −0.04 | 0.02 |

| Shops in supermarkets | 0.11 | −0.15 to 0.36 | 0.41 |

| Multiple children | 0.03 | −0.13 to 0.19 | 0.72 |

The baseline population above denotes respondents with the following characteristics: from central Addis, low wealth, female, low perception of health benefit, low perception of product safety, low enthusiasm for product, partial grocery decision maker, child eats only adult food, primary education or less, unemployed, shops in kiosks, has one child only.

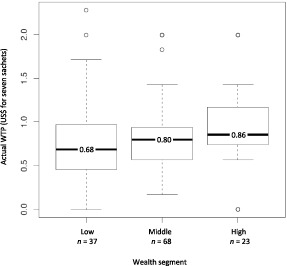

Nevertheless, we did look for trends that might not be statistically significant, but which might be explored in more detail were a larger study to take place with sufficient power to detect multiple differences simultaneously. Specifically, WTP may vary with respondent wealth (Fig. 4). Not surprisingly, the wealthiest respondents had a median WTP almost 18% more than the least wealthy respondents. Several respondents mentioned that they were willing to pay more for the product in order to save money over time, either because their child would be stronger, or because they speculated that the price of Nutributter® would be offset by money saved from purchasing less of other foods. Additionally, WTP only varied slightly with city.

Figure 4.

Actual bid for seven sachets by wealth group. WTP, willingness to pay.

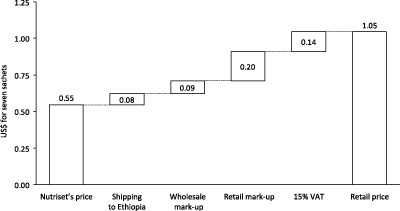

Cost results

The study determined the retail cost of seven sachets of Nutributter® to be $1.05 including 15% value added tax (VAT), but excluding any import duties into the country (Fig. 5). This is based on several sources of cost data. In May 2012, Nutriset quoted Nutributter® at $3.90 per kg prior to delivery charges. The most cost‐effective way to move product to Ethiopia would be by a full 20‐ft container carrying just over 12 012 kg of product, serving just over 1650 child‐years at 20 g per day. The container would be shipped by sea to Djibouti and over land to Addis Ababa at a cost of $6781 with a delivery time of about 1 month. Assuming no import duties, the cost on arrival in Ethiopia is about $0.55 for the product plus $0.08 for shipping.

Figure 5.

Cost build to estimated retail pricing for one week's supply of Nutributter® (exclusive of import duties).

In order to approximate the costs in the retail channel, we interviewed 17 retailers and three wholesalers of complementary foods, demonstrating Nutributter® to each one. While it would have been better to determine their planned buying and selling price using a market simulation method, we simply asked them for their recommended buying and selling prices. Wholesalers stated they would buy the product from $0.14 to $0.40 per seven sachet string. All noted that they are heavily influenced by what their customers are willing to pay. Wholesalers recommended markups of $0.06 to $0.10.

Retailers stated they would buy the product from $0.30 to $2 per seven sachets, giving wholesalers considerable room to increase their buying and selling prices. Retailers' median and mode buying and selling prices were $0.60 and $0.80, respectively. For the purposes of modelling, we add the average wholesale mark‐up of $0.09 and median retail mark‐up of $0.20 to the seven sachet and shipping costs. Finally, we add a VAT of 15% for a total retail price of $1.05 for 7 sachets, translating to $0.15 per day (20 g). This is a price before any duty rate, excise tax, surtax or withholding tax that could be levied on the importation of LNS, or in the case of local manufacturing, on the raw materials.

Discussion

WTP discussion

At the outset of the study, we had hypothesised that WTP would be dramatically higher among wealthy, educated women of central Addis, and lowest among poorer, less educated men outside the heart of the city. While the data cannot prove this hypothesis either way, it does suggest that WTP may not decline steeply with changes of education, wealth, or city. This leaves room for optimism regarding a broad reach of direct‐to‐consumer retail sales of this product.

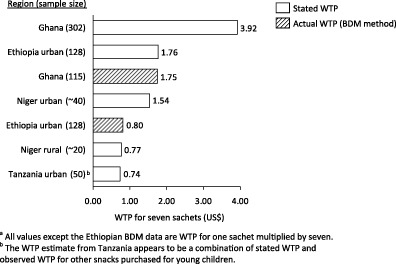

To put the bids in context, median actual WTP per daily sachet (about $0.11) is approximately the cost of one egg purchased in a local market. Eggs were a common food purchase for children among about half the respondent groups. The vast majority of respondents (125 of 128) feed their children some form of complementary food especially designed for children. Although these families can afford food, it is not clear why children across wealth groups are stunted. Perhaps the foods they purchase are not providing an optimal mix of nutrients and calories (Banerjee & Duflo 2011) or other factors such as feeding behaviours or the child's illness may contribute. Most respondents purchased cereals for their children, and in the Addis Ababa groups, most mentioned powdered milk products as well. Several of the brands and prices mentioned are summarised in Table 3. Of these foods, Cerifam – an Ethiopian‐packaged soy and wheat cereal – was popular across nearly all respondent groups, whereas other product preferences varied across respondent groups. The WTP per sachet of Nutributter® is on par with what parents currently spend on other packaged complementary foods (∼$0.09 day−1 for Cerefam), but is likely an additional expense given that Nutributter® is a meal supplement and not a meal replacement. Five other assessments of WTP for LNS have been published in recent years, summarised in Fig. 6. In Ghana, Adams et al. (2011) used both indirect and experimental (BDM) methods to elicit what we would call a stated and actual WTP. Their results were based on 1 day's serving (20 g) of LNS intended for maternal nutrition during pregnancy and lactation. As we observed in Ethiopia, the Ghanaian range of responses ($0–$2.00/20 g) and the mean response ($0.56/20 g) was much higher when respondents did not exchange real money for real product. Using the BDM method the Ghanaian range narrowed ($0–$0.67) and the mean fell by roughly half to $0.26/20 g. In Niger, Tripp et al. (2011) used a direct method of asking mothers what they would pay for 20 g of Nutributter in both urban and rural locations. If the Nigerian population were to follow the pattern observed in Ethiopia and Ghana, the actual WTP may be closer to half the stated values. The fifth study, in Tanzania, collected responses from 50 participants in Dar es Salaam, but did not specify the method used to reach a price target of $0.09–$0.12 per sachet (Claeyssens et al. 2011).

Table 3.

Packaged infant foods popular in Ethiopian cities

| Cereals | ETB price | Pack (g) | US$/20g |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faffa | 14 | 500 | $0.03 |

| Favena | 20 | 500 | $0.05 |

| Barley mix | 22 | 500 | $0.05 |

| Safa corn flour | 18 | 400 | $0.05 |

| Grano pasta | 25 | 500 | $0.06 |

| Cerefam | 16 | 200 | $0.09 |

| Mameal | 28 | 250 | $0.13 |

| Powdered milk | ETB price | Pack (g) | US$/30g |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abay | 80 | 400 | $0.34 |

| Nido | 107 | 400 | $0.46 |

| NAN 1/NAN 2 | 138 | 400 | $0.59 |

| S‐26 | 143 | 400 | $0.61 |

| Supplements | ETB price | Pack (g) | US$/day |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seven seas vitamin syrup | 70 | 150 | $0.13/5g |

| Nutributter median WTP/day | 14 | 140 | $0.11/20g |

ETB, Ethiopian birr; WTP, willingness to pay.

Figure 6.

Willingness to pay for a seven sachets of Nutributter® (140 g). BDM, Becker–Degroot–Marschak, WTP, willingness to pay.

Costs discussion

Cost reduction of LNS is an important topic, and some would argue that local manufacturing could help to reduce shipping costs and potential import duties associated with international production. However, local manufacturing triggers other costs that can make local production more expensive. Like international producers, local producers must import a large proportion of the ingredients and packaging materials to their site of manufacture, often paying import duties on these raw materials (Komrska 2012). The lowest priced, highest quality powdered milk, for example, often comes from New Zealand, the United States and Europe, metallised plastic films for packaging may come from India, sugar may come from Brazil, vitamin mix from Europe, etc. Compared with international producers, local producers may incur higher costs of capital and longer cash conversion cycles as they pay for inputs months before they are able to sell the finished product. Even inputs that can be sourced locally may ultimately prove more expensive than imported inputs. In the case of peanuts, for example, local crops may be rejected because of unacceptable levels of aflatoxin, sometimes making imported peanuts a more reliable and potentially lower cost option. Lower costs of local labour have a minimal effect, as much of the high‐volume production of LNS is automated. Additionally, local manufacturing operates at a small fraction of the scale of large suppliers like Nutriset. Nutriset's French plant has an annual capacity of 61 500 metric tons, which is currently more than twice the capacity of the entire Plumpy' Field network of 15 local manufacturers combined (Nutriset 2011). In the case of ready‐to‐use therapeutic foods (RUTF), the net effect in 2010 was that UNICEF paid, on average, over 20% more (before shipping) on local products than on imported products (Komrska 2010). For RUTF, the cost of local production is significantly higher than imported products, even after considering the costs of freight (UNICEF 2011; Komrska 2012). For LNS, the cost of local and offshore production will be closer. Local production may or may not be less expensive. The site of manufacture has no impact on the 15% VAT charged on all retail products in Ethiopia (Herouy 2004).

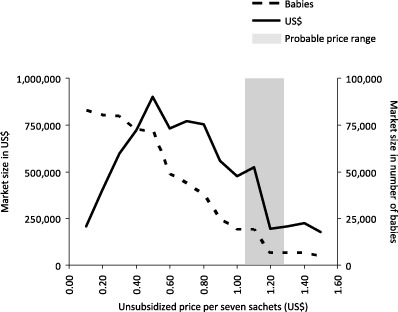

Potential market size

A few generous assumptions can help to roughly quantify the maximum potential market size for Nutributter® in the study areas. Assuming that (1) our respondents were fully representative of the cities where they live; that (2) repeat purchase behaviour over 6 months would be similar to single purchases in a market simulation; that (3) entire populations would have an awareness of a retail LNS product; and that (4) retail shops would actually stock it, the maximum annual retail market size for Addis Ababa, Mekelle, and Hawassa combined is around $500 000 annually (Table 4). If the retail price were to rise, total sales volumes would likely fall as fewer customers would be willing to pay for the product. If the sales price were to fall, the increase in customer volume would substantially grow the market even as revenue per customer fell. Figure 7 uses our WTP data to suggest the relationship of price to market size, and suggests that a pricing of around $0.50 would yield the largest market in terms of revenue. This projection suggests a substantial benefit to cost reduction or subsidy of this product.

Table 4.

Maximum potential market size in three cities

| Region | Population | Annual births* | 1 year olds† | Price/week | %WTP‡ | Weeks/child§ | Max market size¶ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addis Ababa | 3 147 000 | 83 081 | 78 179 | $1.05 | 21% | 25 | $430 962 |

| Hawassa | 162 179 | 4 282 | 4 029 | $1.05 | 25% | 25 | $26 440 |

| Mekelle | 201 528 | 5 320 | 5 006 | $1.05 | 32% | 25 | $42 054 |

*Population multiplied by urban crude birth rate from EDHS 2011.

†Births less urban infant mortality rate from EDHS 2011.

‡Percent of respondents from each site with actual WTP over the $1.05 threshold for unsubsidised product.

§Nutriset recommends Nutributter for at least 4 months. Although conclusive data is not available, leading nutritionists suggest 6 months.

¶The maximum market size assumes all families with WTP ≥$1.05 at each site purchase the product for 25 weeks.

EDHS, Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey; WTP, willingness to pay.

Figure 7.

Potential lipid‐based nutrient supplements market size in four cities as a function of price.

From a manufacturer's point of view, the $500 000 unsubsidised retail market translates into roughly $260 000 in revenue, as the manufacturer only gets about $0.55 per $1.05 in retail sales. To put this in context, $260 000 would be about 0.2% of Nutriset's 2011 revenue of $ 126 million (Nutriset 2011). Multinational food manufacturers seeking to maximise their return on investment may not find such a small market interesting.

Reputable Ethiopian manufacturers with substantial scale and reach may also find this new potential market somewhat small. Fafa Food Shares Company, a recently privatised Ethiopian company is the manufacturer of Ethiopia's top‐selling packaged infant cereal, Cerefam. In 2012, the company anticipates sales of $11 M in 2012 (Belete 2012). Given that cereals for small children sell for $0.03–$0.13 per day in Ethiopia, a company like Fafa could be encouraged by the $0.11 per day WTP figure for LNS. At that price, LNS could potentially serve as an extension of existing cereal product lines, providing incremental revenues without reducing current cereal sales. While an RUTF manufacturer may be best suited to manufacture LNS, a cereal producer might best know how to sell it.

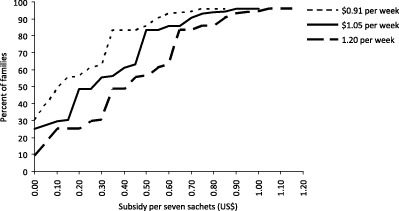

Potential effects of product subsidy

Assuming a retail price of $1.05, 25% of respondents would buy at least one week's supply of Nutributter®. As the retail price falls, according to our simulations, more and more respondents would be willing to buy the product. Figure 8 shows the proportion of respondents that would be willing to purchase the product at varying subsidy levels in three scenarios. The $0.91 assumes that no taxes were applied to the product. The $1.05 price includes 15% VAT, but no import duties. The $1.20 price assumes 15% VAT and a 15% import duty.

Figure 8.

Percentage of families likely to buy Nutributter® at various subsidy levels.

While the market size may or may not be sufficient to garner immediate interest from private companies, these data may have important implications for public/social sector organisations wishing to maximise their reach per donor dollar spent. Specifically, the WTP data open the door for social marketing efforts, which specialise in the for‐profit retail promotion of subsidised health products. Additionally, a retail approach (with or without subsidy) could dramatically extend the reach of donor programmes to distribute LNS.

The most significant challenges, however, will likely be related to product promotion and awareness. As in many other countries around the world, there may be guidelines discouraging the promotion of infant and young child feeding products as per the World Health Assembly Resolution 63.23 section 4, which urges member states to ‘ensure that nutrition and health claims shall not be permitted for foods for infants and young children, except where specifically provided for, in relevant Codex Alimentarius standards or national legislation.’ Unless Ethiopia has specific language to permit the promotion of LNS (which seems unlikely as the product is new to the country), there could be significant obstacles to raising the awareness of LNS. There is still some uncertainty in the interpretation and enforcement of these resolutions, but conservative interpretation combined with strict enforcement would severely impair the development of private markets for LNS products (Greiner 2011; Lybbert 2012). Even if promotion is permitted, it can be costly. Pilots of private sector sales of LNS in Niger have shown that product sales rose and fell sharply when mass media campaigns started and stopped (Beltran‐Fernandez et al. 2011). Maintaining a media campaign can imply significant ongoing costs not currently included in our cost calculation.

Limitations

The limited sample size of this study made it difficult to identify the determinants of WTP with statistical significance. There is additional risk that the respondents may not have been representative of the larger urban population as their families all had existing relationships with a local health extension worker who identified them. As the study staff often came during working hours, we were further limited to respondents who were able to be home with their children during the day.

On the product side, only one version of Nutributter® was offered for sample, which made it challenging for respondents to voice a preference around specific product attributes. For example, on a scale of 1–5, nearly all respondents gave Nutributter® the maximum rating on taste, texture, smell, ease of preparation and other attributes partly because they had no baseline for comparison. Using a comparator product would have made these responses more meaningful.

There were also limitations in the assessment of WTP itself. Although study staff assured respondents that any WTP value was acceptable, even zero, it is possible that some respondents who wished to participate in the study gave artificially high WTP because of some form of courtesy bias. Additionally, it is possible that the up‐front payment of 50 ETB to each respondent prior to the start of the market simulation could have inflated bids. Finally, the fact that the product was promoted in a one‐on‐one likely affected its perceived value, and it is unlikely that such one‐on‐one interactions would take place at a massive scale. We do not know the relative influence of one‐on‐one interaction as used in this study vs. mass media more commonly used to promote consumer products.

At several points in this analysis, we also assert that the WTP for a week's supply of Nutributter® is seven times the WTP for a single sachet. This is not necessarily the case. Poorer customers are often more willing to buy single‐serving ‘sachets’ of products like shampoo or detergents than bottles that might last for weeks or months (Hammond & Prahalad 2004). In our market‐sizing estimate, we also assume that WTP for a week's worth of product would hold every week for 6 months. This has not been validated.

Finally, this study used an asset index based on 2005 EDHS data determine the relative wealth of respondents in each geography. The resulting wealth segmentations did not split the population evenly into thirds, nor were the cutoffs for low, medium, and high wealth the same across study sites. This may have clouded our ability to detect wealth as a determinant of WTP.

Next steps

A future study might further improve on this work by sufficiently powering the sample size to detect the determinants of WTP with greater precision. Both increasing and decreasing the exposure time to LNS could also have important effects. For example, a longer duration of use could more convincingly demonstrate nutritional benefit, as observed by Tripp et al. (2011). Decreasing exposure to simply show the product on a store shelf or have participants listen to a radio advertisement for the product could help to estimate WTP for new users that might not have personal experience with the product. Geographically, a future study could expand to include rural families. A follow on could also address several other possible determinants of WTP. For example, stunting is slightly more common in boys than in girls in Ethiopia [Central Statistical Agency (Ethiopia) and ICF International 2012], but the gender of each child was not recorded. The timing of the study could also matter. Adams et al. (2011) have shown that WTP for LNS can vary seasonally in Ghana.

Once the likely contribution of LNS to the prevention of stunting has been firmly established, private sector retail approaches show great promise in expanding the reach of LNS. A well‐planned product launch might begin by marketing an unsubsidised product in urban areas in order to establish the value of the product and more carefully measure purchase and continuation rates among vulnerable (but not necessarily destitute) populations. Marketing to wealthier consumers can also create an aspirational image for the product that could draw in the interest of lower wealth consumers (whereas the reverse is unlikely to be true.) Simultaneously with a product launch, further consumer research could help to identify the product attributes that might increase WTP without dramatically increasing cost (for example, offering multiple flavours). Such attributes would help to increase coverage faster than cost. Subsidy can also be a valuable option to increase coverage but may best take the form of differentiated brand so as not to diminish revenues in the unsubsidised market.

Source of funding

Alive & Thrive (A&T), funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, is a 6‐year initiative managed by FHI 360 to improve infant and young child nutrition.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributions

JS designed the study with input from KW, KL, TA and YA. JS analysed and interpreted the data and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. DS provided statistical guidance in data analyses. All co‐authors participated in manuscript preparation and critically reviewed all sections of the text.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the mothers and fathers who welcomed them into their homes and took the time to participate in the study; the Ethiopia Health and Nutrition Research Institute for critically reviewing and approving the study's IRB application; and Nutriset for providing Nutributter® for the study. Additionally, several advisors provided invaluable input to the study design and interpretation of results. These included Katie Adams and Steve Vosti of UC Davis; Virginie Claeyssens of Nutriset; Jan Komrska of UNICEF; Geoffrey Kimani and TNS/RMS Kenya, the SART/Ethiopia data collection team; Adam Weiner for his technical analysis; Ellen Piwoz of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; Zo Rambeloson of FHI 360; and Alive & Thrive's Wondafrash Abera Bedada (Ethiopia), and Jean Baker and Luann Martin (FHI 360 Headquarters).

Segrè, J. , Winnard, K. , Abrha, T. H. , Abebe, Y. , Shilane, D. , and Lapping, K. (2015) Willingness to pay for lipid‐based nutrient supplements for young children in four urban sites of Ethiopia. Matern Child Nutr, 11: 16–30. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12022.

Footnotes

In the PSM approach, respondents are asked for four prices: (1) at what price is the product too expensive to buy (2) at what price is the product expensive, but within reach (3) at what price is the product inexpensive enough that one might consider it a bargain and (4) at what price is the product so inexpensive that one begins to doubt its quality, and would therefore not consider buying it. The PSM approach then uses the fraction of total respondents at each price to optimise pricing where price and volume are at their peaks, thereby maximising profit.

References

- Adams K.P., Vosti S.A., Lybbert T.J. & Ayifah E. (2011) Integrating Economic Analysis with a Randomized Controlled Trial: Willingness‐to‐Pay for a New Maternal Nutrient Supplement. In: Agricultural and Applied Economics Association, 2011 Annual Meeting, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, July 24–26, 2011. Available at: http://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:ags:aaea11:103793 (Accessed 11 June 2012).

- Adu‐Afarwuah S., Lartey A., Brown K.H., Zlotkin S., Briend A. & Dewey K. (2008) Home fortification of complementary foods with micronutrient supplements is well accepted and has positive effects on infant iron status in Ghana. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 87, 929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A. & Duflo E. (2011) Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty. Public Affairs: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G., DeGroot M. & Marschak J. (1964) Measuring utility by a single‐response sequential method. Behavioral Science 9, 226–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belete P. (2012) Fafa first to produce powdered milk in Ethiopia. Capital Ethiopia, 28 March. Available at: http://capitalethiopia.com/index.php?option=com_content%26view=article%26id=756 (Accessed 1 June 2012).

- Beltran‐Fernandez A., Sauguet I., Da Costa F., Claeyssens V., Lescanne A. & Lescanne M. (2009) Social marketing of a nutritional supplement in Niger. The Field Exchange 35, 28 Available at: http://fex.ennonline.net/35/social.aspx (Accessed 11 June 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Berry J., Fischer G. & Guiteras R. (2011) Eliciting and Using Willingness to Pay: Evidence from Field Trials in Northern Ghana. Available at: http://www.povertyactionlab.org/publication/eliciting-and-utilizing-willingness-pay-evidence-field-trials-northern-ghana (Accessed 6 June 2012).

- Black R.E., Allen L.H., Bhutta Z.A., Caulfield L.E., De Onis M., Ezzati M. et al (2008) Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet 371, 243–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistical Agency (Ethiopia) and ICF International (2012) Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Central Statistical Agency and ICF International: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA.

- Central Statistical Agency (Ethiopia) and ORC Macro (2006) Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Central Statistical Agency and ORC Macro: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA.

- Claeyssens V., Taha O., Jungjohann S. & Richardson L. (2011) Social marketing in public‐private partnerships as a tool for scaling up nutrition: a case study from Tanzania. UN SCN News 39, 45–50. Available at: http://www.unscn.org/files/Publications/SCN_News/SCNNEWS39_10.01_low_def.pdf (Accessed 1 June 2012). [Google Scholar]

- De Groote H., Kimenju S.C. & Morawetz U. (2010a) Estimating consumer willingness to pay for food quality with experimental auctions: the case of yellow versus fortified maize meal in Kenya. Agricultural Economics 42, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- De Groote H., Tomlins K., Haleegoah J., Awool M., Frimpong B., Banerji A. et al (2010b) Assessing Rural Conumers' WTP for Orange, Biofortified Maize in Ghana with Experimental Auctions and a Simulated Radio Message. Paper prepared for submission to the African Agricultural Economics Association Meetings. Cape Town, 19–23 September, 2010. Available at: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/96197/2/167.%20Assessing%20rural%20consumers%20WTP%20for%20orange%20maize%20in%20Ghana.pdf (Accessed 11 June 2012).

- Dewey K.G., Yang Z.Y. & Boy E. (2009) Systematic review and meta‐analysis of home fortification of complementary foods. Maternal & Child Nutrition 5, 283–321. [Google Scholar]

- Dupas P. (2010) Short‐Run Subsidies and Long‐Run Adoption of New Health Products: Evidence from a Field Experiment. NBER working paper w16298. Available at: http://www.stanford.edu/~pdupas/Subsidies%26Adoption.pdf (Accessed 11 June 2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Greiner T. (2011) Draft guidelines for the marketing of ready to use supplemental foods for children. The Field Exchange 41, 47–51. Available at: http://www.ennonline.net/pool/files/ife/fex41-draft-guidance-on-marketing-rusf-for-children-%26-responses-fex41.pdf (Accessed 14 June 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Hammond A. & Prahalad C.K. (2004) Selling to the poor. Foreign Policy 142, 30–37. May 1, 2004. Available at: http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2004/05/01/selling_to_the_poor?page=full (Accessed 1 June 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Herouy B. (2004) The VAT Regime under Ethiopian Law with special Emphasis on Tax Exemption: The Ethiopian and International Experience. Available at: http://www.crdaethiopia.org/PolicyDocuments/Executive%20Summary%20on%20VAT.pdf (Accessed 13 June 2012).

- Hoffmann V., Barrett C. & Just D. (2008) Do Free Goods Stick to Poor Households? Experimental Evidence on Insecticide Treated Bednets. World Development 37, 607–617. [Google Scholar]

- Komrska J. (2010) Overview of UNICEF's RUTF Procurement in 2010 and Past Years. In: Consultation with RUTF Suppliers. Copenhagen, Denmark, 18 October 2010. Available at: http://www.unicef.org/supply/files/Overview_of_UNICEF_RUTF_Procurement_in_2010.pdf (Accessed 1 June 2012).

- Komrska J. (2012) Increasing access to ready‐to‐use therapeutic foods (RUTF). The Field Exchange 42, 46–47. Available at: http://www.ennonline.net/pool/files/fex/fieldexchange42.pdf (Accessed 11 June 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Kuusipalo H., Maleta K., Briend A., Manary M. & Ashorn P. (2006) Growth and change in blood hemoglobin concentration among underweight Malawian infants receiving fortified spreads for 12 weeks: a preliminary trial. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition 43, 525–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lybbert T. (2012) Hybrid public‐private delivery of preventative lipid‐based nutrient supplement products: key challenges, opportunities and players in an emerging product space. SCN News 39, 32–39. Available at: http://www.unscn.org/files/Publications/SCN_News/SCNNEWS39_10.01_low_def.pdf (Accessed 14 June 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Masters W. & Sanogo D. (2002) Welfare gains for quality certification of infant foods: results from a market experiment in Mali. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 84, 974–989. [Google Scholar]

- Nutriset (2011) Key Figures. Nutriset: Paris, France. Available at: http://www.nutriset.fr/en/about-nutriset/2011-key-figures.html (Accessed 1 June 2012).

- Phuka J.C., Maleta K., Thakwalakwa C., Cheung Y.B., Briend A., Manary M.J. et al (2009) Post intervention growth of Malawian children who received 12‐mo dietary complementation with a lipid‐based nutrient supplement or maize‐soy flour. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 89, 382–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripp K., de Perrine C.G., Campos P., Knieriemen M., Hartz R., Ali F. et al (2011) Formative research for the development of a market‐based home fortification programme for young children in Niger. Maternal & Child Nutrition 7 (Suppl. 3), 82–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF (2011) RUTF Pricing Data. December 15, 2011. UNICEF: New York. Available at: http://www.unicef.org/supply/index_59716.html (Accessed 1 June 2012).

- Van Westendorp P. (1976) NSS‐Price Sensitivity Meter: A New Approach to Study Consumer Perception of Prices. Proceedings of the 29th ESOMAR Congress, pp. 139–167. ESOMAR Publications: Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]