Abstract

This systematic review investigates the relationship between maternal obesity and breastfeeding intention, initiation, intensity, duration and milk supply. A comprehensive search was performed through three major databases, including Medline, Cochrane Library and Cumulative Index For Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and by screening reference lists of the relevant publications. Selection criteria were: report of original research, studies on low‐risk obese mothers and the comparison with normal weight mothers which met at least two of the following primary outcomes: breastfeeding intention; initiation; intensity; duration and/or milk supply. Furthermore, the included reports had to contain a clear definition of pre‐pregnant obesity, use compensation mechanisms for potential confounding factors, have a prospective cohort design and had to have been published between 1997 and 2011 and in English, French or Dutch. Effects of obesity on breastfeeding intention, initiation, intensity, duration and milk supply were analysed, tabulated and summarised in this review. Studies have found that obese women are less likely to intend to breastfeed and that maternal obesity seems to be associated with a decreased initiation of breastfeeding, a shortened duration of breastfeeding, a less adequate milk supply and delayed onset of lactogenesis II, compared with their normal weight counterparts. This systematic review indicates therefore that maternal obesity is an adverse determinant for breastfeeding success.

Keywords: body mass index, breastfeeding, lactation, maternal obesity

Key messages.

Maternal obesity is associated with a decreased intention and initiation of breastfeeding, a shortened duration of breastfeeding, a less adequate milk supply, a delayed onset of lactogenesis II and can thus be considered as a risk factor for adverse breastfeeding outcomes.

Health care professionals should target obese women for additional education and assistance for breastfeeding, starting before conception until 6 months post‐partum, to maximise breastfeeding outcomes as much as possible.

Breastfeeding promotion interventions and counselling practices targeting obese women should be developed to ensure successful initiation and continuation of breastfeeding.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), obesity can be considered as an abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to health (WHO 2011). A crude but clinically applicable population measure of body composition is the body mass index (BMI), which is defined as a person's weight in kilograms divided by the square of his height in meters (kg per m2). A BMI greater or equal to 30 is generally considered obese accordant to the WHO criteria (WHO 2011). Obesity is a public health concern, as it has an increasing prevalence globally. Worldwide, obesity has more than doubled since 1980 (WHO 2011). Current obesity levels range from below 5% in China, Japan and certain African nations, to over 75% in urban Samoa. But even in relatively low prevalence countries like China, rates are almost 20% in some cities (WHO 2003). The results of a recent report in France show an increase in the prevalence of obesity, affecting 12.4% of the population, including women of childbearing age (Obépi 2006; WHO 2011). The situation in the United States is even worse. In 2010, no state had a prevalence of obesity less than 20% (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2012). A study about obesity in pregnant women in the United States revealed a prevalence of obesity of approximately 20%, and in some state and race/ethnicity subgroups, the prevalence was as high as one third (Chu et al. 2009).

Overweight and obesity are major risk factors for the health of women, associated with considerable morbidity and even mortality (Guelinckx et al. 2008). As breastfeeding is important for child health (Gartner et al. 2005), it is interesting to investigate the relationship between different maternal body compositions and associated infant feeding outcome. Recent systematic reviews have shown the association between duration of breastfeeding and the reduced risk for development of obesity and overweight in later life (Harder et al. 2005; Owen et al. 2005). Therefore, it seems important to focus on breastfeeding in the post‐partum period, in particular with obese mothers, because children of obese women have an additional increased risk to develop obesity or overweight in later life (Boney et al. 2005; Dabelea & Crume 2011). Previous research has focussed on the relationship between obesity and breastfeeding. The authors of a systematic review published in 2007 demonstrated that obesity was associated with a significant decrease in breastfeeding intention, initiation and duration (Amir & Donath 2007). While the authors made a thorough and comprehensive analysis of possible contributing factors and potential actions, the review did not include a formal appraisal of the quality of all the studies included. Also, inclusion criteria were less well defined. As a result, studies were included without clarity on the BMI of the studied population (Amir & Donath 2007). Two additional systematic reviews investigated obesity and lactational performance but did not study breastfeeding intention, initiation or duration (Lovelady 2005; Rasmussen 2007). Furthermore, as new evidence is being published in recent years, this subject needs to be updated.

This aim of this article is to review the relationship between maternal obesity and breastfeeding by investigating whether pre‐pregnant BMI can be a determinant for breastfeeding intention, initiation, intensity and duration, and whether it can affect the milk supply and the onset of lactation.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

The literature review was conducted by a two‐step search strategy. First, relevant research articles were identified by consulting electronic databases, including Medline, Cochrane Library, and Cumulative Index For Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), using the keywords ‘Lactation'[Mesh], ‘Breast Feeding'[Mesh], ‘Obesity'[Mesh], ‘Overweight'[Mesh], ‘duration’ and ‘initiation’ in different combinations by one of the authors independently (RT). Date restrictions were articles published between 1996 and 2011. Language restrictions were Dutch, English and French. Second, the reference lists of the relevant publications identified in the first step of the searching method were screened in order to find additional relevant research articles (snowball method).

Selection of articles

All studies identified were screened for the following inclusion criteria:

report of original research;

specific studies on low‐risk obese mothers and the comparison with normal weight mothers;

at least two of the following relevant primary outcomes: breastfeeding intention, initiation, intensity, duration and milk supply (delayed onset of lactation);

clear definition of obesity;

cohort studies;

published between 1997 and 2011; and

published in English, French or Dutch.

Studies were excluded from this systematic review when they met any of the following exclusion criteria:

containing a high risk obstetric population; and

published before 1997.

Only quantitative cohort designs were considered for inclusion because this design shows relevance for the postulated aim of this systematic review. The studies needed to show original collected data, therefore, reviews and debates were excluded from this systematic review.

The first author (RT) screened all the articles identified by the search strategy by reading them. This literature search process was discussed with the last author (RD).

Definition of obesity

Most of the included studies used the WHO or the US Institute of Medicine (IOM) definition of obesity (IOM 1990; WHO 2011). Table 1 provides the classification of obesity based on the two BMI criteria. If authors defined obesity differently, it is mentioned in Table 2. This review only covers the comparison between obese and normal weight women. The under‐ or overweight categories have not been taken into account.

Table 1.

| Classification | BMI (kg per m2) | |

|---|---|---|

| WHO criteria | IOM criteria | |

| Underweight | <18.5 | <19.8 |

| Normal weight | 18.5–24.9 | 19.8–26.0 |

| Overweight | 25.0–29.9 | 26.1–29.0 |

| Obese | ≥30.0 | >29.0 |

BMI, body mass index; WHO, World Health Organization; IOM, Institute of Medicine.

Table 2.

Summary of included articles

| Authors, year and country | Design | Sample and years of data collection | Definitions | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention | Initiation | Intensity/duration | Milk supply | ||||

|

Hilson et al. (1997) United States |

Observational prospective cohort | n = 1109 birthing women between 19 and 40 years of age who delivered at term from a healthy singleton infant in Bassett Hospital in Cooperstown, NY between 1992 and 1994 |

BMI calculated from pre‐pregnancy weight and height – IOM definition of obesity Initiation of BF: defined as BF at hospital discharge (HD) 2 days after birth |

NR |

|

|

NR |

|

Donath & Amir (2000) Australia |

Observational retrospective cohort | National Health Survey of 1995 in Australia, n = 2612 children under the age of 4 years | Maternal BMI calculated from the mother's self‐reported height and weight at the time of interview – WHO definition of obesity | NR |

|

|

NR |

|

Chapman & Perez‐Escamilla (2000) United States |

Observational prospective cohort | n = 57 healthy BF women who gave birth to a healthy, single, term infant in Hartford Hospital, Hartford, CT between June 1997 and November 1998 |

Definition of obesity: at least 2 or 3 of the following criteria: BMI at 72 h pp > 30 (WHO definition), subscapular skinfold thickness at 72 h pp > 33.7 mm or heavy/obese build on day 1. Delayed onset of lactation: maternal perception on onset of lactation ≥72 h pp or milk transfer at 60 h pp <9.2 g/feeding. Milk transfer was measured by weighing the infant before and after the BF session |

NR | NR |

|

|

|

Li et al. (2002) United States |

Observational retrospective cohort | The Third National Health and Nutrition Survey, n = 8765 children younger than 6 years (for duration analyses: n = 7712), between 1988 and 1994 | Maternal BMI calculated from the mother's self‐reported height and weight at the time of interview – WHO definition of obesity | NR |

|

|

NR |

|

Li et al. ([Link]) United States |

Observational prospective cohort | n = 51 329 mother–infant pairs of single birth in 1996 from the Pediatric and the Pregnancy Nutrition Surveillance System, USA, for the analysis of BF initiation of whom 13 234 were included for BF duration (conducted between 1996 and 1998) | Maternal BMI calculated from self‐reported pre‐pregnancy weight – IOM definition of obesity | NR | Pre‐pregnant obese women, regardless of their gestational weight gain, are more likely to never breastfeed than women with a normal BMI before pregnancy and who gained the recommended weight during pregnancy (P < 0.01) |

|

NR |

|

Kugyelka et al. (2004) United States |

Observational prospective cohort | Medical Record review, upstate NY, healthy mothers between 19 and 40 years old at delivery, with a BMI ≥ 19.1 who gave birth to a healthy singleton infant at term between 1998 and 2000, n = 263 black women and 235 Hispanic women |

Maternal BMI calculated from pre‐pregnancy weight and height – IOM definition of obesity Initiation of BF: defined as BF at hospital discharge |

NR |

|

|

NR |

|

Hilson et al. (2004) United States |

Observational prospective cohort | Antenatal cohort eligibility, n = 114 pregnant women between 19 and 45 years old carrying a singleton foetus and with an intention to BF, Cooperstown, NY, between August and November 1998 | Maternal BMI calculated from self‐reported pre‐pregnancy weight and height – IOM definition of obesity |

|

NR |

|

Pre‐pregnant BMI was by itself a borderline significant predictor of delayed onset of lactogenesis II (>72 h) (OR 1.08; CI 1.0–1.2) (P < 0.04) |

| Grjibovski et al. (2005) Russia | Observational prospective cohort | Antenatal community‐based cohort of all pregnant women registered at municipal clinics in 1999, n = 1078 | Pre‐pregnancy weight defined as under‐, normal and overweight based on ‘doctor's diagnosis’ | NR |

|

|

NR |

|

Hilson et al. (2006) United States |

Observational retrospective cohort | n = 2783 mother–infant dyads in which BF was ever attempted and with low contraindications to BF, mother between 19 and 49 years of age, Cooperstown, NY, who gave birth between January 1988 and December 1997 |

Maternal BMI calculated from pre‐pregnancy weight and height – IOM definition of obesity Initiation of BF = BF at 4 days |

NR |

|

|

NR |

|

Scott et al. (2006b) Australia |

Observational prospective cohort | 2 longitudinal infant feeding studies, cohort of women recruited in hospital in Perth, between September 1992 and April 1993, or between mid‐September 2002 and mid‐July 2003, n = 587 | Measurement of maternal height and weight not reported in the study – WHO definition of obesity | NR |

|

|

NR |

|

Oddy et al. (2006) Australia |

Observational prospective cohort | Birth cohort, n = 1803 live‐born children and their mothers ascertained through antenatal clinics at the major tertiary obstetric hospital in Perth, between May 1989 and November 1991 | Maternal BMI calculated from pre‐pregnancy weight and height – WHO definition of obesity | NR |

|

|

NR |

|

Scott et al. (2006a) Australia |

Observational prospective cohort | 2 longitudinal infant feeding studies, cohort of women recruited in hospital in Perth between mid‐September 2002 and mid‐July 2003, n = 587 | Measurement of maternal height and weight not reported in the study – WHO definition of obesity | NR | NR |

|

NR |

|

Baker et al. (2007) Denmark |

Observational prospective cohort | Danish National Birth Cohort, n = 37 459 women who gave birth at term from 1999 to 2002, between 18 and 45 years old who chose to BF to a healthy baby with a normal birth weight | Maternal BMI calculated from self‐reported pre‐pregnancy weight and height – WHO definition of obesity: obese class I (BMI 30.0–34.9), obese class II (BMI 35.0–39.9) and obese class 3 (BMI ≥ 40.0) | NR |

|

|

NR |

|

Manios et al. (2009) Greece |

Observational retrospective cohort | Data from cross‐sectional GENESIS study were used, n = 2374 pre‐schoolers with full maternal anthropometric data before and during pregnancy and BF data between April 2003 and July 2004 | Maternal BMI calculated from pre‐pregnancy weight and height – IOM definition of obesity | NR |

|

BF duration: coefficient of mean weeks less BF than reference group: obese: 0.48; NS (P = 0.744) | NR |

|

Mok et al. (2008) France |

Observational prospective cohort | Obstetrics database at Poitiers, n = 222 French‐speaking women who delivered term from a singleton foetus between March and October 2005 | Maternal BMI calculated from self‐reported pre‐pregnancy weight and height – WHO definition of obesity | NR |

|

|

|

| Donath & Amir (2008) Australia | Observational retrospective cohort | Infant cohort, n = 3075 children of average 42 weeks old of whom data were available on BF duration to 6 months and mothers BMI, recruited in 2004. | Maternal BMI calculated from self‐reported weight and height at time of the interview (when children were 42 weeks old on average) – WHO definition of obesity | NR |

|

|

NR |

|

Kitsantas & Pawloski (2010) United States |

Observational prospective cohort | Early Childhood Longitudinal Study‐Birth Cohort, singleton births in 2001 with data for pre‐pregnancy BMI and BF initiation and duration, n = 2150 | Maternal BMI calculated from self‐reported pre‐pregnancy weight and height – IOM definition of obesity | NR |

|

|

NR |

|

Liu et al. (1990) United States |

Observational prospective cohort | n = 6375 women who delivered live infants between 2000 and 2005 for the analysis of BF initiation, of whom 3902 were for the analysis of BF duration, South Carolina | Maternal BMI calculated from self‐reported weight and height before conception – WHO definition of obesity: obese (BMI: 30–34.9), very obese (BMI ≥ 35) | NR |

|

|

NR |

|

Guelinckx et al. (2011) Belgium |

Retrospective epidemiological study | n = 200 women attending prenatal care for a singleton pregnancy and delivering a living infant at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Hospital Leuven, in 2006 and 2007. | Maternal BMI calculated from pre‐pregnancy weight and height – WHO definition of obesity: obese (BMI: ≥30) |

|

|

|

NR |

BMI, body mass index; WHO, World Health Organization; IOM, Institute of Medicine; BF, breastfeeding; OR, odds ratio; OR*, self‐calculation of odds ratio; EBF, exclusive breastfeeding; ABF, any breastfeeding; pp, postpartum; NS, not significant; SE, standard error; SD, standard deviation; ref, reference; IQR, interquartile range; CI, confidence interval; NR, not reported; RR, relative risk.

Outcome definitions

Breastfeeding intention is defined as the intention of the woman to breastfeed; initiation of breastfeeding is defined as the infant's first intake of breast milk; duration of (any) breastfeeding is defined as the total length of time an infant receives any breast milk at all; duration of exclusive breastfeeding is defined as the duration the infant exclusively receives breast milk as the source of nourishment; and delayed onset of lactogenesis is defined as an onset after 72 h post‐partum.

If authors defined these outcomes differently in their articles, it is again recorded in Table 2.

Critical appraisal

The methodological quality of the cohort studies was evaluated by the cohort study quality assessment list proposed by the Dutch Cochrane Centre (2010). The following criteria were assessed: sample description, selection bias, definition of obesity, definition of outcomes, length of follow‐up, selective loss‐to‐follow‐up and confounders. The appraisal questions were graded ‘+’ when the criterion was fulfilled, ‘+/−’ when the criterion was unclear and ‘−’ when the criterion was not fulfilled. Results of the evaluation of methodological quality of the studies are presented in Table 3. This assessment was carried out independently by the first author (RT) and in case of any doubt, the last author (RD) was consulted.

Table 3.

Critical appraisal of the included articles by appraisal criteria (Dutch Cochrane Centre 2010)

| Author and year | Sample clearly described | Selection bias excluded | Clear definition of obesity | Clear definition of outcomes | Sufficient length of follow‐up | Selective loss to follow‐up excluded | Adjusted for potential confounding factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hilson et al. (1997) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Donath & Amir (2000) | +/− | + | + | + | NA | NA | + |

| Chapman & Perez‐Escamilla (2000) | + | − | + | + | + | +/− | − |

| Li et al. (2002) | + | +/− | + | + | NA | NA | − |

| Li et al. ([Link]) | + | + | + | + | + | +/− | + |

| Kugyelka et al. (2004) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Hilson et al. (2004) | + | + | + | − | +/− | +/− | + |

| Grjibovski et al. (2005) | +/− | + | + | − | + | +/− | + |

| Hilson et al. (2006) | + | + | + | + | NA | NA | + |

| Scott et al. (2006a) | +/− | +/− | + | + | + | + | + |

| Oddy et al. (2006) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Scott et al. (2006b) | + | +/− | + | + | + | − | − |

| Baker et al. (2007) | + | + | + | + | + | +/− | + |

| Manios et al. (2009) | + | + | + | + | NA | NA | + |

| Mok et al. (2008) | + | + | + | + | − | + | +/− |

| Donath & Amir (2008) | + | + | + | + | NA | NA | + |

| Kitsantas & Pawloski (2010) | + | + | + | + | + | +/− | + |

| Liu et al. (2010) | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| Guelinckx et al. (2011) | + | + | + | + | NA | NA | + |

NA, not applicable (retrospective design); + = criteria fulfilled; − = criteria not fulfilled; +/− = unclear if criteria are fulfilled.

Results

Selection of studies

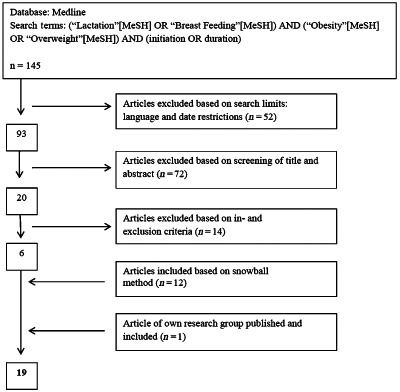

The Medline search with the previously mentioned keywords provided 145 search results. Based on search criteria, 93 articles were withheld. Based on title and abstract, 20 articles were withheld. After reading the articles, based on in‐ and exclusion criteria, 14 more articles were excluded. Afterwards, 12 additional articles were found by checking the reference lists of the relevant publications. This literature search process is shown in Fig. 1. A literature search in the Cochrane Library and CINAHL did not reveal any articles of relevance. One additional study of our series, conducted at the University Hospital Leuven and published at about the same time this review was conducted, was also included in this review (Guelinckx et al. 2011). Finally, 19 articles were included in this review (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flowchart literature search and selection of articles.

Quality appraisal of the included articles

Most studies have a prospective cohort design (Hilson et al. 1997, 2004; Chapman & Perez‐Escamilla 2000; Li et al. [Link]; Kugyelka et al. 2004; Grjibovski et al. 2005; Oddy et al. 2006; Scott et al. 2006a,b; Baker et al. 2007; Mok et al. 2008; Kitsantas & Pawloski 2010; Liu et al. 2010), except for six retrospective cohort studies (Donath & Amir 2000, 2008; Li et al. 2002; Hilson et al. 2006; Manios et al. 2009; Guelinckx et al. 2011). Two included prospective studies reported on the same study sample but described different outcomes (breastfeeding initiation and duration) (Scott et al. 2006a,b). In the retrospective design studies, two of the critical appraisal criteria involving follow‐up are considered not applicable. In the prospective design studies, sufficient length of follow‐up for the duration of breastfeeding is defined as a minimal follow‐up of 6 months.

Although all of the included studies describe a clear definition of obesity, one study used a definition of obesity different from the WHO or IOM definition (Grjibovski et al. 2005), where pre‐pregnancy weight is classified as underweight, normal or overweight based on a ‘doctor's diagnosis’. Measuring methods for maternal BMI are also quite diverse in the included studies. There were 8 of the 18 included studies that use self‐reported pre‐pregnancy weight and height (Donath & Amir 2000; Li et al. 2002, [Link]; Hilson et al. 2004; Baker et al. 2007; Mok et al. 2008; Kitsantas & Pawloski 2010; Liu et al. 2010), one study uses self‐reported weight and height at the time of the interview (Donath & Amir 2008), and two articles (from the same study) do not report measurement of weight and height in the study (Scott et al. 2006a,b). The remaining eight studies calculate maternal BMI from pre‐pregnancy weight and height.

Seven studies receive maximal quality scores (Hilson et al. 1997, 2006; Kugyelka et al. 2004; Oddy et al. 2006; Donath & Amir 2008; Manios et al. 2009; Guelinckx et al. 2011). Although the majority of studies give a clear description of breastfeeding outcomes, the definition of initiation of breastfeeding varies quite strongly between different studies. The study of Hilson et al. (2006), for example, defines breastfeeding initiation as breastfeeding at 4 days post‐partum. Another finding in the quality appraisal of the included studies is that the study of Chapman & Perez‐Escamilla (2000) could not exclude selection bias, as they did not clearly describe the in‐ and exclusion criteria for their sample. The study is also limited by the sample size, which is significantly smaller than in other reports (Chapman & Perez‐Escamilla 2000).

One criterion in the cohort study quality assessment list proposed by the Dutch Cochrane Centre (2010) not used in the quality assessment of this review is the applicability of the results on all Western developed countries, as there are various countries where the included studies were conducted. This criterion is also not considered of major relevance for this subject, as breastfeeding is a universal and widely applicable subject and obesity is a global increasing problem.

Breastfeeding intentions

There are two studies included in this review that examine how maternal pre‐pregnant BMI influences infant feeding intentions (Hilson et al. 2004; Guelinckx et al. 2011). A small US study found that obese women planned to breastfeed their infant for a significant shorter period than their normal weight counterparts (6.9 months vs. 9.3 months) (Hilson et al. 2004). The results of the study conducted in Leuven (Belgium) indicate that significantly fewer obese mothers intended to breastfeed (Guelinckx et al. 2011).

Breastfeeding initiation

There were 15 of the 16 studies about breastfeeding initiation included in this review that demonstrate decreased breastfeeding initiation rates among obese women, compared with their normal weight counterparts (Hilson et al. 1997, 2006; Donath & Amir 2000, 2008; Li et al. 2002, [Link]; Kugyelka et al. 2004; Oddy et al. 2006; Scott et al. 2006a; Baker et al. 2007; Mok et al. 2008; Manios et al. 2009; Kitsantas & Pawloski 2010; Liu et al. 2010; Guelinckx et al. 2011). The difference is statistically significant in most studies (Donath & Amir 2000, 2008; Li et al. 2002, [Link]; Hilson et al. 2006; Scott et al. 2006a; Baker et al. 2007; Mok et al. 2008; Manios et al. 2009; Guelinckx et al. 2011). The study of Hilson et al. (1997), however, only find a significant difference between obese and normal weight women in breastfeeding at hospital discharge. The difference is not statistically significant for black women in two US studies (Kugyelka et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2010), nor for women in a study in Western Australia (Oddy et al. 2006) or women in a Greek study after adjusting for confounding factors (Kitsantas & Pawloski 2010). In the studies that demonstrate a statistical significant difference in breastfeeding initiation, the estimated effect of obesity on not initiating breastfeeding (compared with normal weight women) range from an odds ratio (OR) of 1.19 to 3.65. In contrast with these results, a Russian study found that more obese women than non‐obese women initiated breastfeeding (100% vs. 98.7%), although this difference was not significant (Grjibovski et al. 2005).

Duration of any breastfeeding

Maternal obesity seems to be associated with a shortened (median) duration of any breastfeeding (Hilson et al. 1997, 2004, 2006; Chapman & Perez‐Escamilla 2000; Donath & Amir 2000, 2008; Li et al. 2002, [Link]; Kugyelka et al. 2004; Grjibovski et al. 2005; Oddy et al. 2006; Scott et al. 2006b; Baker et al. 2007; Mok et al. 2008; Manios et al. 2009; Kitsantas & Pawloski 2010; Liu et al. 2010; Guelinckx et al. 2011). Eighteen studies about the duration of any breastfeeding are included in this review, of which the majority show a decrease in the duration of any breastfeeding in obese women compared with normal weight women, even after adjusting for possible confounding factors (Donath & Amir 2000, 2008; Li et al. 2002, [Link]; Hilson et al. 2004, 2006; Grjibovski et al. 2005; Oddy et al. 2006; Scott et al. 2006b; Baker et al. 2007; Mok et al. 2008; Manios et al. 2009; Kitsantas & Pawloski 2010; Liu et al. 2010; Guelinckx et al. 2011). This difference is statistically significant in 11 of the 18 studies, with the exception of two studies in the United States that did not find any difference in duration of any breastfeeding among black women (only among Hispanic women) (Kugyelka et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2010). In four studies, the mean duration did not differ significantly between obese and non‐obese women (Hilson et al. 2004; Grjibovski et al. 2005; Mok et al. 2008; Manios et al. 2009); and in one study, the difference in duration could only be shown at 6 months (Scott et al. 2006b). Obese women also have a significant higher risk of an early cessation/discontinuation of breastfeeding at any time, with hazard ratios ranging from 1.24 to 2.54 (Hilson et al. 1997, 2004, 2006; Donath & Amir 2000, 2008; Oddy et al. 2006; Baker et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2010). This increase in risk is, however, only significant in Hispanic women (not in black women) (Liu et al. 2010). Secondly, Hispanic obese women have a higher ratio of combining formula feeding to breastfeeding instead of exclusive breastfeeding [OR 1.92; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.20–3.08] (Kugyelka et al. 2004), compared with normal weight mothers. Chapman & Perez‐Escamilla (2000), in contrary, demonstrate in their study that obese women are more likely to breastfeed longer than their non‐obese counterparts (likelihood of not breastfeeding: OR 2.28; 95% CI 1.02–5.11). But this study contains a small sample of participants compared with the other studies and does not carry out a multivariate analysis (Chapman & Perez‐Escamilla 2000).

Duration of exclusive breastfeeding

Eleven studies included in this review study the duration of exclusive breastfeeding in obese women (Hilson et al. 1997, 2004, 2006; Chapman & Perez‐Escamilla 2000; Li et al. 2002; Kugyelka et al. 2004; Scott et al. 2006a,b; Baker et al. 2007; Mok et al. 2008; Guelinckx et al. 2011). There were 10 of the 11 studies that find that obese women have a consistently higher risk of discontinuing exclusive breastfeeding than normal weight women. The proportional hazard regressions of obese women of (early) discontinuing exclusive breastfeeding vary from 1.19 to 1.43, but this is not significant in black women (Hilson et al. 1997, 2004, 2006; Chapman & Perez‐Escamilla 2000; Li et al. 2002; Kugyelka et al. 2004; Scott et al. 2006a; Baker et al. 2007; Mok et al. 2008). This difference, however, is only significant in Hispanic women (not in black women) (Kugyelka et al. 2004). Obese women also breastfeed exclusively for a shorter period than their normal weight counterparts. In the study of Hilson et al. (2004), this difference in mean duration between obese and non‐obese women is not statistically significant. Scott et al. (2006b) showed a statistically significant difference between obese and non‐obese women at the time of 7 days post‐partum, but not at 1, 3 or 6 months post‐partum (Scott et al. 2006b).

One study, however, shows that obese women are more likely to breastfeed exclusively for a longer period than non‐obese women (likelihood of not exclusively breastfeeding: OR 1.23; 95% CI 0.67–2.27), although not statistically significant (Chapman & Perez‐Escamilla 2000).

Milk supply

Chapman & Perez‐Escamilla (2000) demonstrate that obese women have a higher risk of low milk transfer (less than 9.2 g per feeding) at 60 h post‐partum than non‐obese women (OR: 6.14, 95% CI: 1.10–37.41). They were not able, however, to show a significant difference in maternal perception on perceiving the onset of lactation to be early (<72 h post‐partum) vs. late (≥72 h postpartum) between obese and non‐obese women (P = 0.49). Hilson et al. (2004), however, demonstrate in their study that pre‐pregnant BMI, by itself, was a borderline significant (P < 0.04) predictor of delayed onset of lactogenesis II (copious milk secretion) (OR 1.08; CI 1.0–1.2).

Among non‐obese women, Chapman & Perez‐Escamilla (2000) also find that women who breastfed more frequently had higher milk transfer values and earlier onset of lactogenesis, compared with women who breastfed less frequently, but they could not find a relationship between those variables in obese women.

Another study shows that fewer obese women perceived their milk supply as adequate vs. reference‐weight mothers at 1 month (60% vs. 94%) and 3 months (55% vs. 92%) post‐partum (Mok et al. 2008).

Guelinckx et al. (2011) find that obese women give insufficient milk as a reason to cease breastfeeding more frequently than other women (24% vs. 13%, P = 0.041) (Guelinckx et al. 2011).

Discussion

The results of this review indicate that obese women plan to breastfeed for a shorter period and are less likely to initiate and continue breastfeeding than their normal‐weight counterparts. Concerning milk supply, obese women have a significant lower milk transfer and fewer obese women perceive their milk supply as adequate, compared with non‐obese women, although there is no significant difference in the time of onset of lactation. The latter is in contrast to animal studies suggesting that maternal obesity is detrimental to the initiation of lactation (Rasmussen 1998; Flint et al. 2005).

Overall, using more stringent inclusion criteria and including recent publications, our findings confirm the results of an earlier systematic review on the effect of obesity on intention, initiation and duration of breastfeeding (Amir & Donath 2007). Additionally, we show decreased intensity of breastfeeding in this population.

It is important to reflect on possible explanations for adverse breastfeeding outcomes among obese women. It is an obvious observation that obese women are generally likely to have larger breasts, which can be a mechanical barrier to put the baby to the breast, and can therefore have a negative influence on the milk production and secretion. A significantly higher proportion of obese women report difficulties breastfeeding (e.g. cracked nipples, fatigue or difficulty initiating breastfeeding) on the maternity ward, at 1 month and at 3 months post‐partum in comparison with normal‐weight women (Mok et al. 2008). Breastfeeding practices should also be considered as a social act, which can be influenced by psychosocial and cultural factors. Obese women report more often feeling uncomfortable breastfeeding at 3 months in the presence of others compared with reference‐weight mothers (Mok et al. 2008). The included studies that compared characteristics of obese women vs. non‐obese women also demonstrate that obese women are more likely to belong to groups with a lower socio‐economic status. Three national health surveys in Australia demonstrated that a low socio‐economic status is a determinant for reduced intention and initiation of breastfeeding (Amir & Donath 2008). Not all of the included studies in this review, however, considered socio‐economic status as a potential confounding factor, thus alternative explanations for the inverse relationship between BMI and breastfeeding practices are possible. As comprehensively reviewed by Amir & Donath (2007), the reasons why overweight and obese women are less likely to breastfeed include anatomical, socio‐cultural, but also medical and psychological factors.

Study strengths and limitations

Limitations of this review need to be mentioned. As evaluated in the quality appraisal of the studies included in this review, 9 of the 18 studies included used self‐reported maternal weight and height. Such estimates are not completely accurate with the possible risk of misclassification of BMI categories, which could have biased the reliability of the results in these studies.

We have used strict and well‐defined criteria for the studies to be included. As a result, less studies were selected than in a previous review, including 22 studies (Amir & Donath 2007). Some of the papers included in their work reported on women with ‘weight concerns’ or who were ‘heavy before becoming pregnant’ without certainty about their pre‐pregnancy BMI. We feel that these well‐defined criteria add to the validity of our findings.

The study of Chapman & Perez‐Escamilla (2000) could not exclude selection bias as they do not clearly describe the in‐ and exclusion criteria for their sample. The sample size used in this study was also significantly smaller than in the other studies, which resulted in the impossibility of carrying out a multivariate analysis. Their results often disagree with the results of the majority of the other studies included in this review (Chapman & Perez‐Escamilla 2000). The major strength of this study is the study design. Being a systematic review, all the evidence on the subject has been collected in a systematic way. Most of the included studies are relatively small, but the results of most studies are concordant in their conclusions. Second, because of this systematic review, it is possible to formulate hypotheses to be tested as a basis for recommendations for clinical practice.

Implications for further research

Little is known about the effect that breastfeeding in obese women has on weight retention after pregnancy and on their obesity in general. One animal study, published in 2010 (Makarova et al. 2010), examined if pregnancy and lactation have anti‐obesity effects, but for possible ethical considerations, this has not yet been conducted among humans. There is also a need for qualitative studies to help us understand women on their infant feeding decisions and behaviour. As to date, no study has examined this issue from the women's perspective, which could be useful to facilitate the development of more effective breastfeeding promotion interventions targeted at obese women. Finally, counselling practices aimed at obese women need to be evaluated in further research.

Implications for clinical practice

In this systematic review, a number of negative breastfeeding outcomes are identified in obese women. Findings from this review suggest that health care professionals should consider obese women at risk for poor breastfeeding success and that they merit additional attention. To optimise the breastfeeding practice in obese women, health care professionals could target obese women for additional education and assistance for breastfeeding, starting before conception until 6 months post‐partum. Breastfeeding promotion interventions and counselling practices targeted at obese women specifically should be developed and tested for efficacy before implementation to ensure successful initiation and continuation of breastfeeding.

Conclusion

Findings from this systematic review suggest that maternal obesity can be considered as a risk factor for adverse breastfeeding outcomes. Health care professionals should be aware of this problem, as obese women are in need of intensive guidance and counselling, starting from conception, to maximize breastfeeding outcomes as much as possible. Breastfeeding promotion interventions should be developed in collaboration with obese women and tested before implementation.

Source of funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

The author declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributions

RT and SB analysed and interpreted the data and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. RD provided statistical guidance in data analyses. RT, SB, SG and RD assisted in the interpretation of results. All co‐authors participated in manuscript preparation and critically reviewed all sections of the text for important intellectual content.

References

- Amir L.H. & Donath S. (2007) A systematic review of maternal obesity and breastfeeding intention, initiation and duration. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 7, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir L.H. & Donath S.M. (2008) Socioeconomic status and rates of breastfeeding in Australia: evidence from three recent national health surveys. Medical Journal of Australia 189, 254–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker J.L., Michaelsen K.F., Sorensen T.I. & Rasmussen K.M. (2007) High prepregnant body mass index is associated with early termination of full and any breastfeeding in Danish women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 86, 404–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boney C.M., Verma A., Tucker R. & Vohr B.R. (2005) Metabolic syndrome in childhood: association with birth weight, maternal obesity, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics 115, e290–e296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012) Overweight and Obesity. Data and Statistics. US Obesity Trends . Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/trends.html Last updated: 27 February 2012. (Accessed 19 March 2012).

- Chapman D.J. & Perez‐Escamilla R. (2000) Maternal perception of the onset of lactation is a valid, public health indicator of lactogenesis stage II. Journal of Nutrition 130, 2972–2980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu S.Y., Kim S.Y. & Bish C.L. (2009) Prepregnancy obesity prevalence in the United States, 2004–2005. Maternal and Child Health Journal 13, 614–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabelea D. & Crume T. (2011) Maternal environment and the transgenerational cycle of obesity and diabetes. Diabetes 60, 1849–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donath S.M. & Amir L.H. (2000) Does maternal obesity adversely affect breastfeeding initiation and duration? Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 36, 482–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donath S.M. & Amir L.H. (2008) Maternal obesity and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: data from the longitudinal study of Australian children. Maternal & Child Nutrition 4, 163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutch Cochrane Centre (2010) Formulier voor het beoordelen van een cohortonderzoek . Available at: http://dcc.cochrane.org/beoordelingsformulieren-en-andere-downloads Last updated: 1 July 2010. (Accessed 9 March 2011).

- Flint D.J., Travers M.T., Barber M.C., Binart N. & Kelly P.A. (2005) Diet‐induced obesity impairs mammary development and lactogenesis in murine mammary gland. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 288, 1179–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner L.M., Morton J., Lawrence R.A., Naylor A.J., O'Hare D., Schanler R.J. et al (2005) Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 115, 496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grjibovski A.M., Yngve A., Bygren L.O. & Sjostrom M. (2005) Socio‐demographic determinants of initiation and duration of breastfeeding in northwest Russia. Acta Paediatrica 94, 588–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guelinckx I., Devlieger R., Beckers K. & Vansant G. (2008) Maternal obesity: pregnancy complications, gestational weight gain and nutrition. Obesity Reviews 9, 140–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guelinckx I., Devlieger R., Bogaerts A., Pauwels S. & Vansant G. (2011) The effect of pre‐pregnancy BMI on intention, initiation and duration of breast‐feeding. Public Health Nutrition 15, 840–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder T., Bergmann R., Kallischnigg G. & Plagemann A. (2005) Duration of breastfeeding and risk of overweight: a meta‐analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology 162, 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilson J.A., Rasmussen K.M. & Kjolhede C.L. (1997) Maternal obesity and breast‐feeding success in a rural population of white women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 66, 1371–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilson J.A., Rasmussen K.M. & Kjolhede C.L. (2004) High prepregnant body mass index is associated with poor lactation outcomes among white, rural women independent of psychosocial and demographic correlates. Journal of Human Lactation 20, 18–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilson J.A., Rasmussen K.M. & Kjolhede C.L. (2006) Excessive weight gain during pregnancy is associated with earlier termination of breast‐feeding among White women. Journal of Nutrition 136, 140–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insitute of Medicine (IOM) (1990) Nutrition during Pregnancy. National Academy Press: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Kitsantas P. & Pawloski L.R. (2010) Maternal obesity, health status during pregnancy, and breastfeeding initiation and duration. Journal of Maternal‐Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 23, 135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugyelka J.G., Rasmussen K.M. & Frongillo E.A. (2004) Maternal obesity is negatively associated with breastfeeding success among Hispanic but not Black women. Journal of Nutrition 134, 1746–1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Ogden C., Ballew C., Gillespie C. & Grummer‐Strawn L. (2002) Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding among US infants: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Phase II, 1991–1994). American Journal of Public Health 92, 1107–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Jewell S. & Grummer‐Strawn L. (2003) Maternal obesity and breast‐feeding practices. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 77, 931–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Smith M.G., Dobre M.A. & Ferguson J.E. (2010) Maternal obesity and breast‐feeding practices among white and black women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 18, 175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovelady C.A. (2005) Is maternal obesity a cause of poor lactation performance. Nutrition Reviews 63, 352–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova E.N., Yakovleva T.V., Shevchenko A.Y. & Bazhan N.M. (2010) Pregnancy and lactation have anti‐obesity and anti‐diabetic effects in A(y)/a mice. Acta Physiologica (Oxford, England) 198, 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manios Y., Grammatikaki E., Kondaki K., Ioannou E., Anastasiadou A. & Birbilis M. (2009) The effect of maternal obesity on initiation and duration of breast‐feeding in Greece: the GENESIS study. Public Health Nutrition 12, 517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok E., Multon C., Piguel L., Barroso E., Goua V., Christin P. et al (2008) Decreased full breastfeeding, altered practices, perceptions, and infant weight change of prepregnant obese women: a need for extra support. Pediatrics 121, 1319–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obépi (2006) Enquete Epidémiologique Nationale sur le Surpoids et l'Obésité . INSERM/TNS Healthcare SOFRES/Roche: Paris, France.

- Oddy W.H., Li J., Landsborough L., Kendall G.E., Henderson S. & Downie J. (2006) The association of maternal overweight and obesity with breastfeeding duration. Journal of Pediatrics 149, 185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen C.G., Martin R.M., Whincup P.H., Smith G.D. & Cook D.G. (2005) Effect of infant feeding on the risk of obesity across the life course: a quantitative review of published evidence. Pediatrics 115, 1367–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K.M. (1998) Effects of under‐ and overnutrition on lactation in laboratory rats. Journal of Nutrition 128, 390–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen K.M. (2007) Association of maternal obesity before conception with poor lactation performance. Annual Review of Nutrition 27, 103–121, 103–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J.A., Binns C.W., Graham K.I. & Oddy W.H. (2006a) Temporal changes in the determinants of breastfeeding initiation. Birth 33, 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J.A., Binns C.W., Oddy W.H. & Graham K.I. (2006b) Predictors of breastfeeding duration: evidence from a cohort study. Pediatrics 117, 646–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2003) Obesity and Overweight Fact Sheet . Available at: http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/gs_obesity.pdf Last updated: 2003. (Accessed 22 March 2012).

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2011) Obesity and Overweight. Fact Sheet n.311 . Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html Last updated: March 2011. (Accessed 13 January 2012).