Abstract

In Egypt, the double burden of malnutrition and rising overweight and obesity in adults mirrors the transition to westernized diets and a growing reliance on energy‐dense, low‐nutrient foods. This study utilized the trials of improved practices (TIPs) methodology to gain an understanding of the cultural beliefs and perceptions related to feeding practices of infants and young children 0–23 months of age and used this information to work in tandem with 150 mothers to implement feasible solutions to feeding problems in Lower and Upper Egypt. The study triangulated in‐depth interviews (IDIs) with mothers participating in TIPs, with IDIs with 40 health providers, 40 fathers and 40 grandmothers to gain an understanding of the influence and importance of the role of other caretakers and health providers in supporting these feeding practices. Study findings reveal high consumption of junk foods among toddlers, increasing in age and peaking at 12–23 months of age. Sponge cakes and sugary biscuits are not perceived as harmful and considered ‘ideal’ common complementary foods. Junk foods and beverages often compensate for trivial amounts of food given. Mothers are cautious about introducing nutritious foods to young children because of fears of illness and inability to digest food. Although challenges in feeding nutritious foods exist, mothers were able to substitute junk foods with locally available and affordable foods. Future programming should build upon cultural considerations learned in TIPs to address sustainable, meaningful changes in infant and young child feeding to reduce junk foods and increase dietary quality, quantity and frequency.

Keywords: child feeding, complementary foods, breastfeeding, infant and child nutrition, practices, child public health

Introduction

Since 2005, Egypt has faced increased levels of food insecurity, combined with rising poverty rates, food prices and several food, fuel and financial crises, including the avian influenza epidemic in Lower Egypt. These successive crises resulted in reduced household access to food and purchasing power (World Food Programme 2013b). One of every three Egyptian children under 5 years old is stunted, ranking Egypt among the 34 countries with the highest burden of malnutrition – where 90% of the world's stunted children reside (El‐Zanaty & Way 2009; Black et al. 2013).

The total economic cost of child undernutrition is estimated at 20.3 billion Egyptian pounds (3.7 billion US dollars) or 1.9% of the gross domestic product, which mostly emanate from stunting‐related losses in manual labour productivity, affecting 64% of Egyptians (World Food Programme 2013a). Egypt is experiencing the double burden of malnutrition, with rising prevalence of stunting, accompanied by rising levels of overweight and obesity in adults and children (Food and Agriculture Organization 2006, El‐Zanaty & Way 2009). Twenty per cent of children under the age of 5 are overweight or obese (Food and Agriculture Organization 2006) and nearly 75% of adult women are overweight (Yang & Huffman 2013). In Egypt, losses because of chronic disease associated with obesity are estimated to be US$1.3 billion by 2015 (Abegunde et al. 2007).

In the face of increased poverty, there is a growing reliance on energy‐dense, low‐nutrient foods and subsidized foods, such as oil and bread in Egypt (Egyptian Cabinet's Information and Decision Support Centre & World Food Programme 2012). About 35% of Egyptians suffer from limited dietary diversity as a consequence of limited awareness of the connection between nutritious foods and health, shifts to westernized diets characterized by low intakes of fruit and vegetables and rising food prices (Musaiger 2011, International Food Policy Research Institute & World Food Programme 2013). Nutrient‐poor diets, which include a reliance on low‐nutritive, high fat ‘junk’ foods, may contribute to stunting and overweight (Huffman et al. 2014). Yet little is known about feeding practices of young children in Egypt and household and community level influences on infant and young child nutrition.

The current study explored perceptions and beliefs of mothers and other key informants related to infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices in Egypt. The intent of the study was to gain an understanding of the cultural and contextual influences on nutrition practices, including consumption of junk foods in Egyptian children 0–23 months of age. The research objectives were twofold: (1) to understand the cultural beliefs, perceptions and motivations for optimal and poor feeding practices, including feeding junk foods to children younger than 2 years of age; and (2) to assess the role of other caretakers and health providers in supporting mothers' feeding practices of toddlers.

Key messages

Prelacteal feeding is an entry point to early introduction of junk foods – as a remedy for perceived insufficient breast milk.

Mothers and family members routinely give these ‘preferred’ and ‘liked’ junk foods, as part of the daily meal, with small amounts of nutritious foods.

‘Junk’ foods are considered good, natural and ‘essential’ complementary foods and an easy way to feed toddlers.

Trials of Improved Practices (TIPs) revealed that mothers can substitute locally available nutritious snacks for junk foods.

Educational strategies should target families and health providers to not feed junk foods prior to 2 years of age to ensure that children reach their potential for growth.

Materials and methods

Study design and site

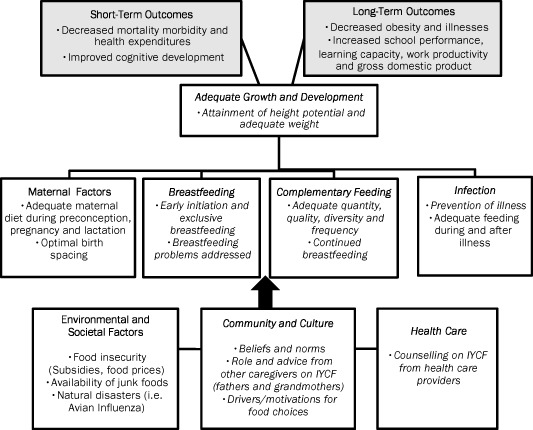

Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework for the study, adapted from the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework on Childhood Stunting which emphasizes the joint importance of exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months, complementary feeding and continued breastfeeding in children 6–24 months of age, within the context of other key factors for strengthening IYCF programmes (Stewart et al. 2013). The conceptual framework illustrates how contextual factors, including cultural beliefs and norms of mothers, motivations/drivers of food choices and advice given by other caregivers and health providers underlie feeding practices in the first 2 years of life (see Fig. 1, italicized concepts are discussed in this paper).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework adapted from World Health Organization framework on Childhood Stunting (Stewart et al. 2013).

Concepts that are italicized represent the variables for which results are presented in this paper.

The Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) is the United States Agency for International Development flagship project on maternal, newborn and child health focused on addressing the underlying causes of maternal, newborn and child mortality. MCHIP implemented the Community‐based Initiatives for a Healthy Life (SMART) project to improve health service delivery and nutritional status through private sector community development association clinics and community health workers in Egypt. The study sites reflect two of six SMART project governorates and allowed for comparisons of IYCF practices between regions with the highest (Lower Egypt) and the lowest (Upper Egypt) levels of stunting, according to the 2008 Egypt Demographic and Health Survey (El‐Zanaty & Way 2009).

The two study sites were Qaliobia governorate in Lower Egypt and Sohag governorate in Upper Egypt. Qaliobia, Lower Egypt is a semi‐urban region, north of Cairo in the Egypt Delta, with an estimated population of 4.2 million. Qaliobia is the top producer of chicken and eggs and 11% of the population are considered poor (United Nations Development Program & Institute of National Planning Egypt 2010). Sohag governorate, Upper Egypt, an agricultural rural region, nearly half of the population (3.7 million) is considered poor. Sohag produces sugar cane, grains and clover for animal husbandry (United Nations Development Program & Institute of National Planning Egypt 2010).

Mothers, 18 years and older with children 0–23 months of age (n = 150), were randomly selected from the SMART project‐generated, age‐stratified lists of project participants (i.e. every sixth child was selected from a random numbers table). Mothers were contacted by SMART project community health workers during routine home visits and oral consent was obtained for all three Trials of Improved Practices (TIPs) visits by study staff. Study participants were stratified according to child's age: 0–5, 6–8, 9–11, 12–17 and 18–23 months, based on known milestones for IYCF (n = 15 per age group) (Pan American Health Organization & World Health Organization 2003). A total of 150 mothers with children 0–23 months of age, n = 75 per site, participated in the study. In‐depth interviews (IDIs) with fathers (n = 40) and grandmothers (n = 40) of children 0–23 months of age, as well as and health providers (n = 40), were conducted to examine their perceptions, beliefs and role in influencing and providing advice to mothers on IYCF, which allowed for triangulation with information from mothers' interviews (Patton 2002; Ritchie & Lewis 2003). Husbands, grandmothers and health providers were recruited through purposive sampling from the same villages as mothers in both regions. Oral consent was also obtained for these participants, following initial contact by the SMART project.

Data collection

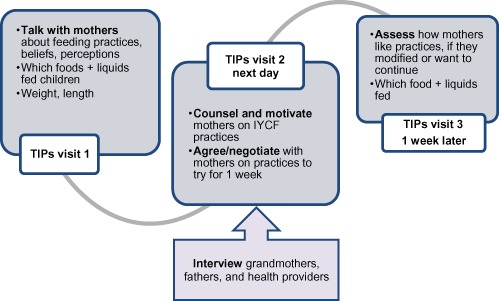

TIPs (Dicken et al. 1997) is a consultative research methodology which consists of three household visits with mothers (see Fig. 2), which combines both exploratory and participatory research components. Three pairs of study team members, a trained nutritionist and interviewer, conducted the three consecutive TIPs visits.

Figure 2.

Trials of improved practices involve discussing with counselling and motivating mothers to make feasible modifications to feeding practices.

During TIPs visit 1, the study team discusses mothers' current and past IYCF practices and positive aspects and challenges mothers face with feeding her child. During the first visit, qualitative data on cultural beliefs, perceptions and behaviours related to IYCF practices were collected through IDIs with mothers. Dietary intake was collected using 24‐h recall and food frequency questionnaires for all children aged 6–23 months of age (n = 120). Weight (kg) and recumbent length (cm) was measured by trained local nutritionists. During this exploratory phase, junk food was uncovered as a feeding problem, along with other poor feeding practices, as well as motivators and drivers of feeding junk foods.

Prior to the next day's visit (between TIPs visit 1 and TIPs visit 2), the study team reviewed the IDI data and dietary information to identify challenges and gaps mothers faced in feeding, based on global feeding recommendations, according to child age (Pan American Health Organization & World Health Organization 2003). During TIPs visit 2, the participatory research component, the study team counselled mothers on optimal feeding practices, as a basis for discussing feasible, locally available solutions to address identified IYCF problems contextualized by cultural beliefs and perceptions that emerged from TIPs visit 1. The second TIPs visit provided an opportunity to explore how to further address junk food consumption. Mothers agreed to try feeding practices that are new to them and carry out affordable culturally appropriate practices for a 1‐week period. During TIPs visit 3, the study team documented mothers' experiences with recommended practices and whether they modified and/or intended to continue the practice(s) in the future.

During TIPs visit 3, a second 24‐h recall, food frequency was used to determine changes in dietary intake. Formal household observations were planned but were not carried out because of cultural superstitions concerning ‘evil eye’ (Dundes 1992).

Interviews with grandmothers, fathers, as well as health providers, from each of the study sites were conducted on the same day as TIPs visit 2.

Analyses

The study team conducted preliminary analyses of IDIs and identified dominant IYCF themes based on the concepts and variables presented in the conceptual framework, including themes related to breastfeeding and complementary feeding. IDIs included questions pertaining to cultural beliefs, perceptions, as well as roles and behaviours related to IYCF and growth.

Findings from these preliminary analyses were used to develop an agreed‐upon coding structure or ‘a priori’ coding framework, which served as the basis of our analyses. Qualitative analyses of transcripts were carried out using the NVivo version 10.0 analytic program (QSR International Pty Ltd 2012). The subsequent coding process allowed for the identification of additional themes that emerged during interviews. Trained transcribers audiorecorded all IDIs from TIPs, fathers, grandmothers and health care providers and transcribed them verbatim into Arabic. Trained interpreters translated transcripts from Arabic into English, which were checked against Arabic transcripts (SM, GK, MH). The three TIPs visits were coded and verified by separate researchers (SM, JAK, MH, GS, MAF). Two researchers (SM, GK) coded interviews with fathers, health care providers and grandmothers. Once coding was complete, three researchers (MH, JAK, GS) looked independently at a subset of transcripts to verify the themes in the original framework and confirm additional emergent concepts. Transcripts were reviewed and triangulated with field data collection forms. Fieldwork took place in February–April 2013 in Lower and Upper Egypt.

Egyptian food consumption tables were used to compute nutrient intake from 24‐h recall data at the first and third TIPs visits for children aged 6–23 months (n = 120), using recommended intakes from WHO and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (Dewey & Brown 2003, Pan American Health Organization & World Health Organization 2003, Food and Agriculture Organization & World Health Organization 2008) and recent calculations made for protein in this age group (Reeds & Garlick 2003; Paul et al. 2011). Medians were used to describe the centre of the nutrient intake data, given outliers. Percentage of children whose nutrient intakes are below the estimated requirement from complementary food were calculated.

Food frequency, collected at first TIPs visit only, was analysed daily and weekly (<3 times, ≥ 3 times per week) by age group and region and percentages are reported. Nutritional status was categorized by anthropometric (i.e. physical growth) measures of stunting: <−2 standard deviation (SD) height for age, wasting <−2 standard deviation weight for height, underweight <−2 SD weight for age, as well as overweight (>+2 SD) and obesity (>+3 SD), which were computed using the WHO International Growth Reference Curves (de Onis et al. 2006).

Junk foods are high energy, low in nutrient content and/or high in fat (i.e. some contained trans‐fats) snack foods that contain added sugar (i.e. sugary biscuits, cream‐filled sponge cakes, candy, fizzy drinks) or have high salt content (i.e. fried potato crisps (chips) (World Health Organization 2010). Nutritious snack foods were noted as yogurt or fruit. Other beverages, low in nutrient content, including herbal teas/drinks and fruit juices were also investigated in this study. In collaboration with local researchers, all instruments were piloted in communities in Lower and Upper Egypt and then adapted to the local cultural context. Ethical approval was granted by the Egyptian Society for Healthcare Development, PATH Research Ethics Committee and the American University in Cairo Social Research Center.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Mothers, with children 0–23 months of age, participating in TIPs (n = 150) were 18–43 years of age. Mothers were not formally employed and worked as housewives (see Table 1). Greater than half of mothers had completed secondary education and twice as many mothers in Lower Egypt vs. Upper Egypt had completed post‐secondary education. Fathers ranged in age from 24 to 50 years old. Most fathers completed either secondary education or held a post‐secondary degree and worked in white collar positions and in unskilled labour. Most grandmothers did not have formal schooling. IDIs with health care providers consisted of primarily medical doctors in Lower Egypt. A variety of health providers in Upper Egypt participated in IDIs because of a shortage of physicians. Both regions of Egypt are primarily Muslim.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Characteristics | Mothers participating in TIPs* | Supporting in‐depth interviews on IYCF † | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other caregivers | Health providers | (n = 270) | |||||||

| Fathers | Grandmothers | ||||||||

| LE | UE | LE | UE | LE | UE | LE | UE | ||

| (n = 75) | (n = 75) | (n = 20) | (n = 20) | (n = 20) | (n = 20) | (n = 20) | (n = 20) | ||

| Gender of child | |||||||||

| Male | 38 | 46 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 6 | – | – | 123 |

| Female | 37 | 29 | 11 | 8 | 8 | 14 | – | – | 107 |

| Age of child in months | |||||||||

| 0–5.99 | 15 | 15 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | – | – | 41 |

| 6–8.99 | 15 | 15 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 5 | – | – | 43 |

| 9–11.99 | 15 | 15 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | – | – | 35 |

| 12–17.99 | 15 | 15 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 7 | – | – | 57 |

| 18–23.99 | 15 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 5 | – | – | 54 |

| Education | |||||||||

| Illiterate | 3 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 13 | – | – | 28 |

| Read and write | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 4 | – | – | 26 |

| Primary school | 7 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | – | – | 20 |

| Secondary school | 39 | 47 | 11 | 9 | 1 | 0 | – | – | 107 |

| Post‐secondary school | 21 | 11 | 9 | 7 | 0 | 1 | – | – | 49 |

| Occupation | |||||||||

| Unemployed | 62 | 69 | 1 | 0 | 19 | 18 | – | – | 169 |

| Unskilled labour | 5 | 2 | 10 | 6 | 0 | 2 | – | – | 25 |

| Professional | 8 | 4 | 9 | 14 | 1 | 0 | – | – | 36 |

| Health provider specialty | |||||||||

| Medical doctor | – | – | – | – | – | – | 17 | 3 | 20 |

| Pharmacist | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Nurse | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 10 | 11 |

| Community health worker | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Midwife | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0 | 1 | 1 |

IYCF, infant and young child feeding; LE, Lower Egypt; TIPs, trials for improved practices; UE, Upper Egypt. *Participants in three household TIPs visits – include in‐depth interviews, dietary recall and food frequency on IYCF. †Caregiver and health provider in‐depth interviews supplemented TIPs interviews.

Qualitative findings from TIPs visit 1 and supporting IDIs: cultural beliefs and perceptions are drivers of IYCF practices

Dominant themes that emerged from analyses of TIPs data are presented in Table 2 and presented here. The summary in the succeeding paragraphs reflects mothers' most salient perceptions and beliefs pertaining to IYCF, which were confirmed by grandmothers, fathers and health providers. No differences were found between Lower and Upper Egypt.

Table 2.

Summary of dominant themes within each study participant group*

| Themes | Mothers from TIPs (n = 150) | Health providers (n = 40) | Grandmothers (n = 40) | Fathers (n = 40) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LE (n = 75) | UE (n = 75) | LE (n = 20) | UE (n = 20) | LE (n = 20) | UE (n = 20) | LE (n = 20) | UE (n = 20) | |

| Breastfeeding practices | ||||||||

| ✓(24) | ✓(26) | ✓(23) | ✓(22) | ✓(15) | ✓(19) | ✓(14) | ✓(4) | |

| Breastfeeding is important for child health | ‘Good for the child's immune system and it helps him grow’ | ‘It is very important that the child exclusively breastfeeds’ | ‘The more the child breastfeeds, the more he will grow, all praise be to God’ | ‘The most important thing for having a healthy child is breastfeeding’ | ||||

| ✓(50) | ✓(33) | ✓(8) | ✓(6) | ✓(2) | ✓(4) | ✓(2) | ✓(4) | |

| Prelacteal feeding of liquids and herbal drinks common cultural practice | ‘I gave her herbal drink for about 2 days, until my milk came in’ | ‘What should be given after birth immediately is colostrum, and herbal drink’ | ‘The doctor prescribed herbal drink for colic, he started taking it since he was born’ | ‘He took herbal drink during the first week’ | ||||

| ✓(28) | ✓(33) | ✓(16) | ✓(9) | ✓(12) | ✓(10) | ✓(3) | ✓(5) | |

| Prelacteal feeding/perceptions of milk insufficiency is an entry point to mixed feeding and early introduction of snack | ‘The flow of my milk is weak. The doctor asked that I buy milk from the pharmacy to give the baby alongside my own’ | ‘I advise mothers to give their children milk and biscuits when their milk is not enough’ | ‘When mother's breast milk is light she can make him anise and caraway drink until he is 4 months then she can feed him yoghurt’ | ‘The child drinks herbal baby drink since delivery, the mother is working, so baby drink is important’ | ||||

| ✓ (18) | ✓ (10) | ✓ (2) | ✓ (2) | ✓ (8) | ✓(7) | ✓ (4) | ✓ (5) | |

| Cultural practice of ‘talhees’ † is a form of early food introduction | ‘I was told to start giving him a taste (tongue licking) of the food I eat’ | ‘The mother can dip her finger in beans then the child can lick it’ | ‘We started to introduce food at 4–5 months by dipping our finger in food and letting him lick it’ | ‘He should be offered a lick from the food we eat by 3 months, so by 6 months, everything is introduced’ | ||||

| Complementary feeding Practices | ||||||||

| ✓(17) | ✓(26) | ✓(14) | ✓(10) | ✓(30) | ✓(28) | ✓(11) | ✓(2) | |

| Herbal drinks, tea, snack cakes and biscuits are ‘essential’ for infants | ‘Important things that are essential for the baby's growth, like cakes and biscuits’ | ‘Herbal drinks are the 1st things to be introduced to the child at 6 months to help the child grow’ | ‘First we gave them yogurt, rice with milk, tea with bread, biscuits or sponge cake until they began to eat’ | ‘Biscuits are important items in the child diet’ | ||||

| ✓(33) | ✓(24) | ✓(22) | ✓(34) | ✓(6) | ✓(4) | ✓(4) | ✓(3) | |

| Simple and light snack foods address fears of illness, digestion and allergy | ‘Father helps by getting [purchasing] yogurt and store‐bought small sponge cakes my child is ill, these foods are light (akl‐khafeef), easy to give and easy to chew’ | ‘Akl khafeef – light meals, such as biscuits that can be easily digested can be offered to the child until he can digest without troubles’ | ‘I advice mothers to give akl khafeef – light foods so they don't get sick. For breakfast, I just give her some cake’ | ‘When he is with me I give him a biscuit. He does not eat akl al‐bait or tabeekh – family or heavy foods‐ in order not get sick or have a fever’ | ||||

| ✓(34) | ✓(25) | ✓(8) | ✓(19) | ✓74 | ✓(44) | ✓(14) | ✓(8) | |

| Snack foods are good and natural, are not ‘outside’ food | ‘His father gives him soothing foods to eat like yogurt, biscuits and chocolate cream filled snack cakes’ | ‘I advised a mother yesterday to keep away from unhealthy snacks [..] and give biscuits until he is fed meals’ | ‘I decided that I will not give her anything from the store, so I add some biscuits, or sponge cake to the yogurt’ | ‘We give good foods like strawberry flavored yogurt, chocolates, cakes, and biscuits’ | ||||

| ✓(58) | ✓(31) | ✓(2) | ✓(4) | ✓(9) | ✓(2) | ✓(15) | ✓(8) | |

| Snack foods, teas and sugary drinks are an easy way to feed children as they get older or stop breastfeeding as these foods are ‘liked’ | ‘He doesn't like the taste of akl al‐bait‐ home cooked food‐ , he likes yogurt, infant cereal sweetened with sugar, and store‐bought small sponge cakes’ | ‘She can encourage him to eat by offering some sweets or potato chips … because children like crunchy and sweet flavors’ | ‘We give her bags of potato chips 4–5 times a day, these give good nutrition to the child when we are not free to feed her she can sit & eat’ | ‘He started eating packed crisps, chocolates, and other preserved items which he likes’ | ||||

| ✓(29) | ✓(25) | ✓(9) | ✓(14) | ✓(15) | ✓(17) | ✓(6) | ✓(3) | |

| Limiting to non‐nutritive foods also means delayed introduction of family foods and meats | ‘The pediatrician advised me to start giving him from our family food when he is 15 months’ | ‘He can eat eggs and meat at the age of 18 months’ | ‘As long as the child is grown table food is alright, before a year and six months, tabeekh table foods is too heavy’ | ‘For the first two years, akl kafeef – light foods and liquids are important’ | ||||

LE, Lower Egypt; UE, Upper Egypt. Text within quotation marks represents direct quotes from study participants. Check mark (✓) indicates that theme was present in the specified study site. Numbers in brackets indicate the number of references to theme present in each specified study site and participant group. Akl khafeef; light simple foods. Akl al‐bait, table/household foods cooked for the family. Tabeekh, heavy simmered foods cooked in tomatoes and/or meat stew. *n indicates the number of individuals interviewed in each study participant group; †‘talhees’ is a licking process that is traditionally used to introduce infants to food where a caretaker dips fingers into food and allows infant to lick it. This process is repeated a few times.

The context: cultural beliefs around growth

All study participants were asked to discuss their personal perspectives on growth in their communities. Caregivers perceived children were healthy and health workers noted recent improvements in child health because of the SMART/MCHIP messages on nutritious foods. A mother from Upper Egypt explains, ‘we were given the right eating habits to give to small children by a project nearby [SMART] … they educate us’. Participants often did not link growth with dietary intake. A commonly held belief is stunting is hereditary and ‘genetic’. Health providers stated ‘some families are short by nature’ and ‘family genes should be considered’, indicating that growth is not amenable to change.

Breastfeeding practices

Breastfeeding is valued, yet prelacteal feeding of herbal drinks is common

Mothers held the common belief that colostrum or the ‘first milk’ is ‘valuable’, ‘clean’ and ‘full of nutrients’ and eagerly discussed how breastfeeding allows the child ‘to immediately feel the mothers love’ creating ‘a bond between the mother and child’, as well as protects the child against illness. Yet although mothers understand the benefits of colostrum and breastfeeding as a ‘natural choice’, mothers experienced challenges to initiating exclusive breastfeeding and qualified their views of breastfeeding based on whether they had ‘enough’ breast milk. Mothers are often persuaded by health providers and grandmothers to give prelacteal liquids, such as herbal drinks,1 herbal tea infusions (i.e. caraway, anise) and sugar/rice water, after birth in the initial days of life. Commercial herbal health products are locally produced and marketed as nutritional supplements for babies and young children.

Mothers relayed that health providers prescribe herbal drinks to ‘wash the gut of the baby’, thereby soothing the baby's colic or crying until mothers are able to initiate breastfeeding, 6–8 h after birth or until a mother's milk ‘comes in’. Mothers are often separated from their newborn babies after birth and herbal drinks are used as temporary solution to provide some fluids to babies until mothers and babies are reunited.

I had a natural delivery at a private doctor's clinic. The first breastfeeding session was 2–3 h after birth. When I went home my mother gave my baby herbal drink using a syringe as prescribed by my doctor. I gave her herbal drink for about two days, once in the morning and once at night until my milk came in and the baby was able to latch on. (Mother, Lower Egypt)

Prelacteal feeding is an entry point to mixed feeding and early introduction of junk foods

Encouraged and prescribed prelacteal feeding is the entry point for mixed feeding – which is believed to remedy insufficient breast milk and other problems of ‘fussy’ children. Continued use of herbal drinks in the first 6 months is believed to act as soothing and calming agents to ‘help babies sleep at night’. Herbal teas (i.e. anise, caraway) are also viewed as solutions for stomach trouble or ‘cries from hunger’ – an indication that the child is not nourished enough from breastfeeding alone.

As a mother from Lower Egypt explains, ‘I still give her prescribed herbal tea because I felt the milk was not enough, she used to cry a lot’.

This was confirmed by a grandmother from Lower Egypt: ‘If mothers' milk is weak, then we make him [the baby] the anise and caraway herbal mixture, we bought it when we saw that her milk was not satisfying him …’

Mothers justified their decision to continue to supplement breastfeeding with additional food or drink based on perceived quantity and/or quality of breast milk as ‘too weak’, ‘too light’ or ‘too little’. The notion of insufficient milk underlies early introduction of foods as a cultural practice in Egypt, given to children as young as 2 months and commonly fed at 3 to 5 months of age.

Perceptions of poor breast milk quality and quantity prompt mothers to supplement with infant formula and light wajabat khafifia/akl khafeef and simple hagha basseta, including sugary biscuits, yogurt and herbal teas, which was advised by half of the health providers and most grandmothers. A grandmother from Lower Egypt affirmed this notion, ‘I told my daughter … your breastfeeding is not nourishing him, and he is a human like us who needs to eat, what will your milk do for him?’

This is further reinforced by another cultural practice of initial screening of foods through ‘licking’ (talhees), which mothers with children less than 6 months of age discussed during the interviews. Talhees is a practice in which a mother dips her finger in the food for the child to lick. This practice is believed to adapt the child to different tastes, textures and allows the mother to determine the child's ‘readiness’ to eat and swallow as well as the child's likes and dislikes for certain foods.

Complementary feeding practices

Herbal drinks, snack cakes and biscuits are ‘essential’ for young children

After 6 months of age, an overreliance on herbal drinks, tea and juices occur, based on recommendations from some doctors and grandmothers that these drinks are part of healthy growth and should be consumed by children at this age.

The types of food and drinks that should be given first to the children after six months are: anise, tilia (mint like herb), herbal drinks, potatoes, and fruits. (Health Provider, Lower Egypt)

In addition to liquids, mothers perceive cream‐filled sponge cakes and sugary biscuits as light wajabat khafifia/akl khafeef and simple hagha basseta, which are appropriate for children because these foods are ‘nutritive and easy to digest’. These junk foods compensate for the trivial amounts of food given, as mothers limit the variety and how often children are fed. Yogurt, white cheese, rice, potatoes are eaten alongside these junk foods. Mothers tend to typically purchase these as ‘first foods’, as they do not prepare any special foods for children.

‘Simple and light’ nutritious snacks and junk foods address fears of illness, digestion and allergy

Overall, mothers believe that a limited range of foods should be introduced ‘gradually’ and in ‘small amounts’ as they are cautious and fearful that a variety of food will harm the child. Heeding a grandmother's advice on careful introduction of food is reflected in the following quote from a mother from Lower Egypt, ‘My child should eat egg yolks daily but my mother in law advises me to give eggs later, so as not to cause intestinal gas. I will introduce solid foods at the age of 9 months, now I give mashed potatoes, beans, rice and [sugary] biscuits’.

This restriction of food limits intake of fruits and vegetables, lentils/beans or meat and part of the egg – either yolk or egg white. In Lower Egypt, mothers specifically explained how their worries and fears surrounding digestion, illness and development of childhood allergies led to continued restriction of the children's dietary intake to light and simple foods as children became older.

Junk foods are good and natural, are not ‘outside’ food

Aside from these fears, generally considered light wajabat khafifia/akhl khafeef and simple hagha basset foods, such as sugary biscuits, processed cheese and snack cakes, are considered to be ideal foods for young children. These foods are given as a meal, as a snack – between meals, or in combination with another introductory food or liquid, such as yogurt or tea. These foods are not perceived to be an ‘outside’ food, but rather foods that are routinely fed at home, as part of daily meals. Store‐bought hand‐held sponge cakes are viewed as an acceptable convenient ‘first’ food that satisfy a child's hunger. Mothers said store‐bought small sponge cakes are ‘soft, squeezable, easy for children to hold and easy to swallow and the ‘ideal food for children’.

Grandmothers also see no harm in giving these foods, which are considered ‘good’ and ‘natural’. One grandmother mentioned, ‘I would advise all parents to feed their children cream‐filled sponge cakes and [sugary] biscuits’.

A grandmother discusses how sugary biscuits are an integral part of daily food intake.

We give him one container of yogurt, in the beginning, when he gets used to eating we can put a biscuit in the box, we do things gradually, this way, if he accepts, then we can increase the number of yogurt containers to two with a biscuit in each. She currently eats a bit of rice, eggs, a boiled potato, a container of yogurt (with honey or sugar), a pack of biscuits, that's about it. (Grandmother, Lower Egypt)

Junk foods are an easy way to feed infants from 12 to 23 months of age

If a child refuses food, mothers feel like they need to give children junk foods, such as cream‐filled sponge cakes, as a means to encourage a child to eat, along with nutritious foods.

I do not find it difficult to feed [my child] Reda. If she refuses food, I get her a different type of food like sponge cake. … – a child must also have milk, fruit and eggs, to make sure she is eating her meals, I have to feed her myself. (Mother, Lower Egypt)

Mothers and grandmothers are fueled by their desire to feed foods they perceive the children ‘like’. A mother expresses how the father helps with feeding and how the family accommodates to foods children like to eat.

At night, the father helps by getting [purchasing] yogurt and cream‐filled sponge cakes and feeding the child … he likes fried potatoes not boiled, these foods are akhl khafeef (‘light’) and sahl (easy to give) and easy to chew and he also eats rice and pasta … but he doesn't like the taste of home cooked food, he likes yogurt, infant cereal, sweetened with sugar, and cream‐ filled snack cakes. (Mother, Lower Egypt)

Limiting to non‐nutritive foods means delayed introduction of family foods

Mothers perceive that akl al‐bait/akl nass kobar or ‘heavy foods’ and tabeekh or simmered foods2 are difficult for children and hard to digest. These foods are not given to children until they are ‘ready’ to eat such foods, at 1 year of age. Some health providers and grandmothers forbid mothers to introduce meat before 12 months of age. As a health provider reinforced:

There are mustaheel (forbidden) foods that we should not feed the child until he is one year old like: meat. (Health Provider, Lower Egypt)

Grandmothers don't feed tabeekh or simmered food and meat until after a year because these foods are ‘for adults’ and are heavy foods akl al‐bait/akl nass kobar while simple and light foods are akl atfaal or children's food.

It is important for the child to eat a small amount of rice, some mashed potatoes, these are akl khafeef (light) and (simple) hagha basseta, easy to digest and better than eating akl al‐bait (heavy) and tabeekh (simmered) foods. … I also tell their mother not to make them food like us … , I tell her to make them a small amount of rice with milk, or bread with tea, akl atfaal (children's food), because children are not like us. (Grandmother, Lower Egypt)

Junk foods meet the gap in dietary intake when breastfeeding ceases

When children reach 12–23 months of age, mothers begin to feed common akl al‐bait/akl nass kobar or heavy foods given at family meal times, such as cooked vegetables, rice or pasta, lentils or fava beans and small quantities of chicken, liver, red meat, fish or boiled partial eggs (see Table 3). These foods are considered traditional foods. Mothers continued to compensate for the limited intake of foods, as well as children's refusal to eat in older children with feeding junk foods and beverages, such as potato crisps, sponge cakes and fizzy drinks. Mothers believe these foods have a calming effect and aid in pacifying fussy children. These junk foods are believed to be modern, as available, and ready‐made foods. These are often served with nutritious snack foods, such as yogurt or fruit.

His father gives him soothing foods to eat like yogurt, plain biscuits and chocolate creme filled snack cakes. (Mother, Lower Egypt)

Table 3.

Reasons for consumption of traditional and junk foods by age group in Lower and Upper Egypt

| Age in months | Traditional/local foods and liquids given | *Primary reason(s) for feeding | Junk foods given |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5.99 |

Light foods**

Wajabat kafifia/akl khafif

Liquids

|

←Insufficient milk→ ←Crying/colic→ ←Helps child sleep→ |

Light foods

|

| 6–11.99 |

Light foods

Family foods

†

‘akl bait’

Liquids

|

←Light foods are essential→ ←Light foods are good and natural→ ←Easy to digest→ ←Fear of illness→ ←Fear of allergy→ |

Light foods

|

| 12–23.99 |

Light foods

Family/heavy foods ‘akl naas kobar, akl bait’

Liquids

|

←Appropriate for the child's age→ ←Can give more family foods after 1 year Easy to give→ Child likes these foods→ |

Light foods

Other junk foods

|

*Arrows signify whether traditional or junk foods are related to specified reasons for feeding. **Light foods are perceived to be easy to digest. †Family foods are prepared for the family and are not given often to children less than 1 year of age. ‡ Tabeekh or simmered foods is considered to be heavy table food and is cooked with samna (clarified butter) and/or oil. It is also fed during family meals.

Participants were adamant about continued breastfeeding for 2 years based on religious text from the Quran, the Muslim's holy book. However, despite belief in this guidance, mothers discontinued breastfeeding because of misperceptions that breast milk is ‘poisonous’ or ‘harmful’ and ‘breastfeeding too long with affect the child's intelligence’. Mothers also shared their continued frustrations with feelings of weakness and exhaustion ‘my health is affected badly, when I breastfeed’, which also played a role.

An increasing reliance on junk foods may stem from the need to supplement dietary intake, as half of mothers stopped breastfeeding by 18–23 months of age. As one grandmother said:

I give my grandchildren eggs, yogurt, cream‐filled sponge cake. Because children were deprived of their mother's milk … if a child does not eat [much] for two or three days, I would give him some chips, or sponge cake, rice, or some cheese, calcium is good for the child. (Grandmother, Upper Egypt)

Early weaning appears to be connected to mothers' greater reliance on other liquids believed to nourish the child, such as juices or teas, as a replacement for breast milk.

The foods that Hesham eats are fish, rice, fries and chicken … he loves to drink tea a lot and I add 3 spoons of sugar and he also drinks strawberry juice. Sometimes I make guava juice at home. … He also drinks soda around twice a week and I see that these drinks are fit with his age. (Mother, Lower Egypt)

TIPs visit 1: anthropometric status, food frequency and assessment of nutrient intakes via 24‐h dietary recall

Analysis of anthropometric data revealed a small proportion of children were stunted (11%, n = 13) (n = 7 in Lower Egypt, n = 6 in Upper Egypt). Eight per cent of children were categorized as overweight and 7% of children were underweight, the majority of which resided in Upper Egypt. The 24‐h recall data from TIPs visit 1 revealed that the majority of children suffered from inadequate intakes of key nutrients (Table 4 ). Regardless of nutritional status, 96% of children were below estimated requirements for zinc and vitamin A and 81% and 73% of children did not meet iron and energy requirements, respectively. Calcium deficiency affected half (47%) of children, except in 9–11 months old children in Lower Egypt. In terms of energy, the majority of children, who were not stunted, were 92%, 59% and 50% below energy requirements at 6–8, 9–11 and 12–23 months of age, respectively. Junk foods comprised 20.9% of energy intake at 6–8 months, 18.8% of intake at 9–11 months and 9.0% of intake at 12–23 months, as children ate greater variety of foods by 1 year of age.

Table 4.

Trials of improved practices visit 1: 24‐h dietary recall in Lower and Upper Egypt by age group and stunted vs. non‐stunted

| Variable | Estimated requirements for complementary food | Stunted children (n = 13) | Non‐stunted children (n = 104) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6–8 months | 9–11 months | 12–23 months | 6–8 months (n = 3) | 9–11 months (n = 2) | 12–23 months (n = 8) | 6–8 months (n = 24)* | 9–11 months (n = 28) | 12–23 months (n = 52) | |||||||

| Median | % below | Median | % below | Median | % below | Median | % below | Median | % below | Median | % below | ||||

| Energy (kcal per day) | 615 | 686 | 894 | 270.4 | 100 | 334.5 | 100 | 958.6 | 50 | 411.36 | 92 | 461.9 | 100 | 899.5 | 50 |

| Protein (g per day) | 4.6 | 5 | 6.6 | 15.6 | 67 | 16.3 | 0 | 19.0 | 0 | 17.60 | 0 | 17.3 | 0 | 19.9 | 2 |

| Fat (g per day) | 34% of energy (kcal) | 38% of energy (kcal) | 42% of energy (kcal) | 1.4 | 100 | 1.7 | 100 | 33.7 | 100 | 2.45 | 96 | 2.95 | 100 | 27.3 | 94 |

| Vitamin A (μg RE per day) | 6 months = 180 | 7–12 months = 190 | 12 months = 190; 1–3 years = 200 | 442.2 | 33 | 260.8 | 50 | 158.5 | 63 | 453.30 | 4 | 464.0 | 0 | 403.9 | 37 |

| Vitamin D (μg per day) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 8.4 | 33 | 4.4 | 50 | 3.00 | 75 | 8.94 | 4 | 8.94 | 0 | 8.73 | 46 |

| Calcium (mg per day) | 6 months = 300 human milk; cow's milk = 400) | 7–12 months = 400 | 1–3 years = 500 | 249.4 | 67 | 294.1 | 100 | 371.4 | 63 | 350 | 38 | 322.8 | 75 | 494.7 | 31 |

| Iron (mg per day) | 0.5–1 year = 9.3 | 1–3 years = 5.8 | 1–3 years = 5.8 | 0.9 | 100 | 1.1 | 100 | 4.1 | 75 | 1.55 | 100 | 2.20 | 100 | 4.9 | 62 |

| Zinc (mg per day) | 6 months = 6.6 | 7–12 months = 8.4 | 1–3 years = 8.3 | 7.4 | 33 | 7.5 | 100 | 4.2 | 100 | 4.55 | 88 | 4.48 | 100 | 4.6 | 100 |

*Three children: two sick and one refused.

RE = Retinol equivalent

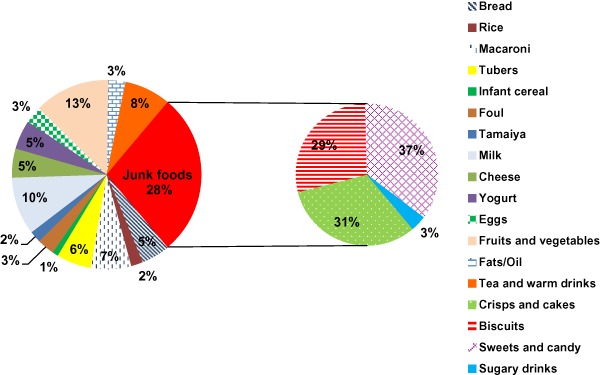

These data are supported by food frequency (Fig. 3) that indicated children's diets were predominately composed of starches/carbohydrates such as Baladi bread (i.e. made of wheat flour and sprinkled with bran), rice, macaroni and/or potato, junk foods, dairy products (milk, yogurt and/or cheese) and lentils/beans. A list of traditional and junk foods consumed by age group are compiled in Table 3. Dairy products and lentils/fava beans are mainstays of the Egyptian diet. In Lower Egypt, yogurt was the most commonly consumed dairy product, whereas buffalo or cow's milk was given to the majority of children in Upper Egypt. Fruits and vegetables comprised 13% of foods consumed on a daily basis. No daily intake of red meat, chicken, fish, liver or luncheon meat was reported via food frequency.

Figure 3.

Daily food frequency for Upper and Lower Egypt (n = 120).

Definitions and specifications: Tubers are plants yielding starchy roots and here they include potato, sweet potato and taro; Junk foods include sugary biscuits, locally made fried potato crisps, commercial potato crisps, store‐bought small sponge cakes, sugary fizzy drinks, as well as sweets and candies (halawa tahenaya: a sweet made from sugar, butter and sesame paste; molasses cane, honey, sugar and hard candy). Foul is traditionally cooked fava beans. T amaiya is traditional bean patties. Milk includes both fresh cow and buffalo milk and powdered milk. Cheese includes traditional white cheese as well as soft processed cheese. Teas and warm drinks include black tea and herbal drinks sweetened with sugar or honey as well as chocolate powdered drink.

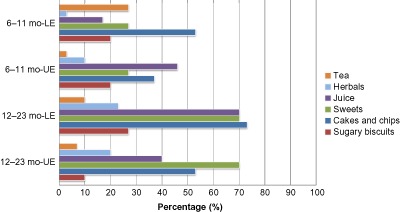

Junk foods including sugary biscuits, sweets/candy, chips and cakes were featured prominently in the diets of young children. As shown in Fig. 3, one‐third of foods consumed daily are junk foods. Junk food consumption was pervasive in both areas and increased from 6 to 11 months of age, peaking at 12–23 months. Greater frequency of consumption of cakes and crisps, sugary biscuits, juice and herbal drinks/teas was reported among 12–23‐month‐old children in Lower Egypt compared with Upper Egypt (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Percentage of foods consumed ≤3 times a week that are junk foodsa and beverages, by age group in months (mo) and regionb (n = 120).

aCakes and crisps include small cream‐filled sponge cakes, fried potato crisps (chips), sweets include candy, chocolates, traditional desserts made with sugar; juice includes fresh and packaged fruit juice; herbals include herbal teas and herbal drinks, tea is black tea often mixed with milk.

b Lower Egypt (LE) and Upper Egypt (UE), n = 30 for each age group and region.

Understanding gaps in IYCF (TIPs visit 1), recommending IYCF practices new to mothers (TIPs visit 2) and mothers' experiences with trying these practices (TIPs visit 3)

The study team used the interview and dietary data from TIPs visit 1 to understand the challenges and gaps Egyptian mothers face in IYCF. Mothers were counselled about optimal IYCF practices in TIPs visit 2 (see Table 5) and were offered several infant feeding practices to try for a 1‐week period to address identified feeding problems in TIPs visit 1. During the TIPs visit 2, mothers were offered age‐specific feeding recommendations to remedy identified feeding problems from TIPs visit 1 and were counselled to try these recommendations (Table 5).

Table 5.

Trials of improved practices (TIPs) visits 1, 2 and 3 summarized: main feeding problems, recommended practices, motivations, benefits and challenges*

| Main infant feeding problem (TIPs 1) | Recommended practices for mothers to try (TIPs 2) | Motivations discussed with mothers (TIPs 2) | Benefits of practice cited by mothers (TIPs 3) | Challenges to practice cited by mothers (TIPs 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breastfeeding is not exclusive † ; mother introduces foods and non‐nutritive liquids such as water, tea and herbal drinks |

|

|

‘The baby is much better, and she no longer has colic or swelling of the stomach’ ‘Her immunity is better’ |

‘My baby refuses to breastfeed and prefers to feed from the bottle because he has gotten used to it’ ‘My baby is constantly crying and she keeps waking up because she has gotten used to eating yogurt before sleeping’ |

| Child consumes tea, made from black tea leaves; mothers often mix tea with milk |

|

|

‘Not nourishing’ ‘Causes anemia’ ‘Appetite increases’ ‘Burns iron in food’ ‘Child can eat now’ |

‘Difficult to reduce [black] tea, I gave anise tea instead’ |

| Child is not fed vegetables or fruits daily |

|

|

‘Child eats more’ ‘Good for health of child’ ‘Health improved’ ‘Gives immunity to child’ ‘Has vitamins’ |

‘She eats just a little bit of these’ ‘She is now eating them a little. I hope she would eat more of these because she is weak’ |

| Child eats junk foods, such as chips, store‐bought small sponge cakes, sodas, sweets and chocolates |

|

|

‘Happy he is eating better’ ‘Eating more’ ‘Don't like preservatives in these foods’ ‘Harmful/bad for health’ |

‘I have reduced it a little and will gradually stop it’ |

| Child is not fed chicken/meat/fish daily |

|

|

‘Child looks forward to eating’ ‘These are very good for his growth and health’ ‘Accepting/eating foods’ ‘Meats are good’ |

|

| Child is not fed often enough (<2 or 3 times per day) |

|

|

‘Eating better/accepting food’ ‘Doesn't stay hungry’ ‘More she grows, more she eats’ ‘Food is good for the child’ |

|

| Child is not fed enough food |

|

|

‘He ate from it’ ‘It contains all the foods that are good for the child’ ‘So she can be nourished’ |

‘My daughter did not like seasamina – the taste and color’ ‘I did not like how it looked’ ‘He refused to eat it’ |

Tbsp, tablespoons; TIPs 1‐2‐3, trials for improved practices first, second and third visit, respectively. *This table presents a summary of TIPs visits 1, 2 and 3: most frequently reported feeding problems captured in the TIPs 1. Recommended practices developed from TIPs 1 and offered to mothers during TIPs 2. Motivational messages developed from TIPs 1 and used to counsel mothers to try recommended practices during TIPs 2. Observed benefits/motivations to continue practices tried cited during TIPs 3. Challenges to practices cited during TIPs 3. †Problem specific to infants 0–5.99 months; ‡The recommendation to give seasamina was given to all mothers of children age 6–23.99 months.

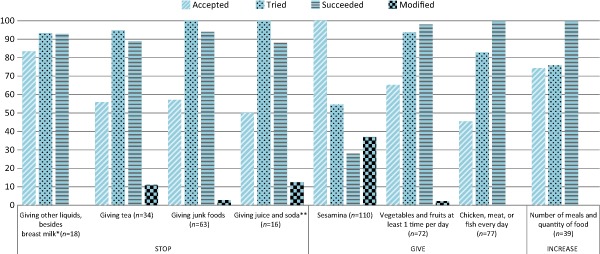

Mothers expressed their willingness to accept and try between one and four culturally tailored IYCF practices (with a maximum of four practices), which mothers selected, for 1 week. Most mothers were able to ‘try’ the recommended practices with few modifications. The percentage of women who ‘accepted’ to try the recommendation, ‘tried’ the recommendation, ‘succeeded’ in carrying out the recommended practice for 1 week and ‘modified’ the recommendation to suit the needs of her child are summarized in Fig. 5. For the majority of recommendations, there were no differences between the two regions in how mothers responded to suggested IYCF practices, yet when applicable, these are discussed in the succeeding paragraphs. Motivations given during counselling, what mothers liked about the recommendations and challenges faced by mothers during the trial period are shown in Table 5.

Figure 5.

Main outcomes of trials for improved practices in children 0–23 months of age in Lower and Upper Egypt (n = 150).

This figure illustrates recommendations that were offered to mothers during trials of improved practices (TIPs) visit 2 based on gaps in current practices and dietary intake identified in TIPs visit 1. The n next to each recommendation represents the number of mothers who were offered the proposed recommendation. Accepted is the percentage of mothers who agreed to try the recommendation proposed during the TIPs visit 2. Tried is the percentage of accepted recommendations that were carried out by mothers. Succeeded is the percentage of tried recommendations which mothers liked and decided to continue after TIPs. Modified is the percentage of tried recommendations that were modified to fit the specific needs of the mother. TIPs recommendations for improving dietary intake was restricted to 6–23‐month‐old children (n = 120) as it is recommended that complementary foods are introduced from 6 months of age. *Recommendation restricted to infant age 0–5.99 months (n = 30); **juice includes fruit juices.

Stop giving any other liquids, besides breast milk, 0–5 months only

In both Upper and Lower Egypt, 18 mothers were counselled to stop giving any liquids aside from breast milk. Of the mothers who accepted to try the practice, 93% succeeded in stopping this practice. More women in Upper Egypt (89%) were willing to stop giving other liquids prior to 6 months of age than in Lower Egypt (56%) (data not shown). The cesarean section rate, among participants in TIPs, was twice as high in Lower Egypt (56%) than Upper Egypt (28%). Herbal drinks are given at a higher frequency in Lower Egypt because of cesarean sections. Initiation of breastfeeding was delayed up to 6–8 h after the surgical procedure and herbal drinks are typically used to calm babies following cesarean sections.

Stop giving your baby tea

Thirty‐four mothers of children 6–23 months of age were counselled on the recommendation, slightly over half agreed not to give tea. Of these mothers who accepted, 89% were successfully able to stop giving tea, while 11% of mothers modified and replaced herbal tea instead of black tea. Mothers were motivated and relayed that ‘tea is harmful for your health and causes anemia’ as reasons for ceasing this practice.

Stop giving junk foods

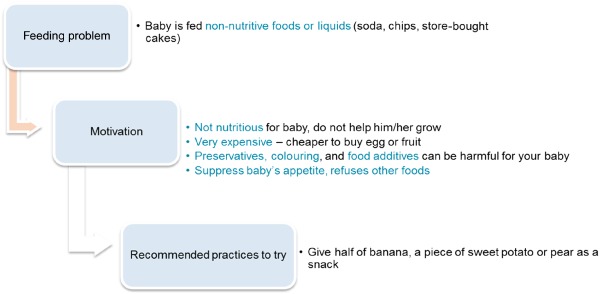

Sixty‐three mothers of children 6–23 months of age were counselled on stopping junk foods for 1 week. Of these mothers, nearly 60% accepted the recommended practice of stopping junk food and giving nutritious snack foods, such as fruits, instead. For example, a stunted 21‐month‐old boy from Upper Egypt was fed luncheon meat, potato chips and small snack cakes, along with small piece of egg and no vegetables or fruits. The mother remarked the boy liked to eat a lot of sugar. The mother was counselled to give cooked vegetables and a piece of fruit (i.e. banana or guava instead of junk food which is full of artificial colouring and preservatives). The mother was able to try all the suggestions in a 1‐week period of time. Regardless of nutritional status, mothers were able to carry out recommended practices. Figure 6 shows three TIPs visits, including motivations and locally available substitutions for junk foods discussed with mothers.

Figure 6.

An example of how trials of improved practices addressed snack food feeding problem in both sites.

Overall, of all mothers who tried the practice of reducing junk foods, nearly all (94%) succeeded (Fig. 5). Junk food consumption tended to occur during dinner/evenings. By region, a greater proportion of mothers stopped feeding snack foods in Lower Egypt (67%) compared with Upper Egypt (44%) (data not shown). Mothers expressed their support for substituting nutritious snacks, such as pieces of fruit for non‐nutritive foods, as ‘better for my child's health’. For one mother, the quantity of chips given to her child was reduced, with the intention to stop giving chips entirely. Mothers expressed that ‘this is more economical for us’.

Stop giving your baby juice or soda

About half of mothers accepted this recommended practice. Of these mothers, all tried the practice and 88% succeeded in carrying it out.

Give your child vegetables and fruits at least once per day

Of the mothers who were counselled on the practice (n = 72), two‐thirds of mothers accepted the practice. Of these mothers, 94% tried the practice and 98% of mothers successfully carried out the practice. Mothers cited ‘vegetables will protect his health and help him grow’ as a motivating factor.

Feed your child a portion of chicken, meat or fish every day

Only 45% of mothers accepted this practice. Overall, combined data revealed all mothers were able to successfully carry out feeding animal source foods. Chicken liver, a more affordable animal source food, was recommended to mothers as an alternative to chicken meat or red meat. Regional stratification show that less than half of mothers in each area succeeded in trying this practice (data not shown).

Feed seasamina, a locally available, complementary food

Seasamina was recommended to all mothers to meet poor IYCF practices for children 6–23 months of age, as mothers did not typically prepare foods for their children.

The recommendation to feed Seasamina to children 6–23 months of age was the complementary feeding practice most often counselled (n = 110) and accepted (100%) by mothers in Lower and Upper Egypt. Seasamina, a local complementary food, made from locally available lentils, flour and tehena, was originally developed by the National Nutrition Institute (Moussa 1973). Local nutritionists discussed with mothers how to prepare seasamina for their children. Yet 55% of mothers tried the practice, 28% succeeded with the practice and 37% of mothers modified seasamina. Seasamina was the only recommendation that was modified frequently by mothers to suit the tastes and preferences of the child. Mothers modified the recipe by either changing the consistency or adding fruits or vegetables to accommodate the tastes or preferences of their children. While some mothers felt their children liked the taste, others reported that seasamina was ‘too thick’, ‘tastes terrible’ and the child ‘refused to eat it’.

Increase the number of meals and the quantity given

About 75% of mothers accepted and tried the practice and all mothers were able to successfully carry out this practice, with no modifications.

Overall, mothers observed positive changes in their child's health following TIPs. The ‘child is full’ ‘less sick’ and ‘having regular bowl movements and is eating better’, were reported as motivators for continuing these practices.

Twenty‐four hour dietary recall: TIPs visit 3

At the third TIPs visit, after the mothers tried the recommended practices for a 1‐week period, improvements in fat, energy, calcium, iron and vitamin A (slightly improved) were noted for all children. Energy increased slightly as a result of increasing the number of meals and amounts given; the greatest increase was in children 9–11 months old, as 41% more children met the nutrient requirement and there was an increase in median caloric intake of 143 calories after the mothers tried the new nutrition practices.

Discussion

Identifying cultural perceptions and beliefs that influence withholding and/or delaying introduction of nutritious food from children and feeding of snack foods, which are ‘junk’ foods, is essential for designing effective IYCF programmes and informing policy. This study gained an understanding of the extent of and reasons for feeding junk foods rather than nutritious, locally available foods. The study also assessed the acceptability and feasibility of using the TIPs methodology with Egyptian mothers to explore whether mothers can try optimal IYCF practices that were new to them, how to motivate mothers to use these practices and what empowers mothers' choices to improve feeding at the household level. Mothers were followed to examine their reactions to trying recommended practices, focusing on reducing junk food and improving the quality and quantity of young children's diets.

Previous evidence from nationally representative surveys and small studies report frequent consumption of junk foods by infants and young children. Recent analyses revealed that 18–66% of children 6–23 months of age consumed low‐nutritive foods in African and Asian countries (Huffman et al. 2014). Past studies reported consumption of junk foods was greater than nutritious foods, such as eggs or fruits, and higher junk food intake in children 12–23 month of age compared with their younger counterparts and in urban areas, which confirmed findings from this study (Anderson et al. 2008; Lander et al. 2010; Engle‐Stone et al. 2012; Huffman et al. 2014). We found no previous studies from Egypt or elsewhere, specifically examining the role of cultural beliefs and perceptions in shaping motivations and reasons for feeding junk foods to toddlers.

Mothers routinely gave sugary biscuits, a common introductory food, as early as 2 months of age. Newborn babies have an innate fondness for sweet tastes (Desor et al. 1973; Steiner 1977; Pepino & Mennella 2006). Yet sensory experiences early in life can shape and modify preferences for flavours and foods (Mennella et al. 2001; Cowart et al. 2011). Early and repeated exposure of sugary foods and beverages accustom the child to sweet flavours (Adair 2012; Stein et al. 2012), which can lead to greater preference, liking and consumption of sweetened foods (Ventura & Mennella 2011), as seen with increased consumption of sponge cakes, sweets and sugary drinks in this study. Junk foods often contain unhealthy fats with trans‐fatty acids (Adair 2012; Stein et al. 2012) and sugar that puts children at risk for dental caries (Selwitz et al. 2007), overweight and obesity (Ludwig et al. 2001). Early salt intake, in the first 6 months, may influence preference for salt, which has been implicated in the development of elevated blood pressure (Geleijnse et al. 1997; Strazzullo et al. 2012).

Previous studies, largely conducted in high‐income countries, reveal that babies who are considered ‘fussy’ are more likely to be fed solid foods or liquids before the recommended age of 6 months, in order to ‘sooth’ children (Carey 1985; Wells et al. 1997; Darlington & Wright 2006; Wasser et al. 2011), which corroborates with the findings from this study. In one study, ice cream, fried potatoes or juice were fed from 1 to 3 months of age to deal with ‘problem’ babies (Wasser et al. 2011). Parenting styles may reflect inappropriate responses or interpretation of infant and young child behaviours, i.e. using cues that crying is a sign that the child is not satiated after being breastfed (Wasser et al. 2011).

Restriction of food to ‘simple and light’ foods went hand in hand with high intake of junk foods and liquids to meet the gap in children's diets not filled by nutritious foods. Egyptian mothers' stated that their primary reasons for withholding introduction of nutritious food and delaying family/table foods until 1 year of age were fears of illness, inability to digest these foods and/or allergy. The belief that certain foods are ‘appropriate’ according to the child's age underlie these feeding behaviours. A few other studies which employed TIPs echo these findings. In Malawi, mothers required convincing that any ‘new food’ would not result in digestive problems (USAID's Infant and Young Child Feeding Project 2011) and in Bangladesh, animal source foods were not considered suitable and withheld from children until 24–35 months of age (Rasheed et al. 2011). Mothers from Lower Egypt expressed greater cautiousness than mothers from Upper Egypt in regard to introduction of meat and variety of foods likely related to the 2006 avian influenza outbreak. Mass removal of chicken and eggs was carried out by the Egyptian government during this period of time. Reductions in diversity of children's diets, as a response to fear of illness, were documented in several studies (Geerlings 2007; Lambert & Radwan 2010). Eggs, poultry, red meat and milk/milk products were replaced with beans, lentils and chickpeas and an overreliance on cereals and tubers was documented (Geerlings 2007; Lambert & Radwan 2010). Fathers and grandmothers discussed not feeding poultry, meat and eggs to children for 1 to 2 years post‐outbreak.

Poor feeding practices in Egypt consisted of feeding small quantities of food, infrequently and delayed introduction of foods, such as meat until 1 year of age. As children continued to receive low amounts of nutritious food with increasing age, junk food consumption increased from 6 months onwards. Intake of junk foods was pervasive in the second year of life, peaking at 12–23 months. This finding is confirmed by Egypt Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) 2008 data – half of children, 12–23 months of age, consumed sugary foods (El‐Zanaty & Way 2009).

Prescription of herbal drinks early in life, by health providers, reinforces the acceptance of herbal drinks as a remedy to signs of colic, illness and/or insufficient milk in the first 6 months of life. Half of Egyptian mothers delay initiation of breastfeeding and do not breastfeed within an hour of birth (El‐Zanaty & Way 2009). Further, prelacteal feeding is common in Egypt, nearly half of babies receive herbal drinks/teas and sugary water (El‐Zanaty & Way 2009). Prelacteal feeding was an entry point to early introduction of foods and beverages. Mothers had an overreliance on beverages of low‐nutritive value, including herbal teas/drinks, juices and black tea. Excessive juice consumption can cause loose stools (Pan American Health Organization & World Health Organization 2003). The liquid form of food satiates children less than solid food, which may lead to overeating (Pan & Hu 2011). Excessive intake of juice is associated with short stature and obesity and failure of children to thrive (Smith & Lifshitz 1994; Dennison et al. 1997). Mothers should be taught to reduce liquid intake of juices and instead feed locally available fruits. Tea interferes with the absorption of iron and zinc, which exacerbates existing deficiencies.

Replacing unhealthy foods with locally available alternatives is an important component of improving poor IYCF practices and nutritional status (Huffman et al. 2014). Through TIPs, mothers were able to substitute non‐nutritive foods with available and affordable nutritious foods with one counselling session during the second TIPs visit. Mothers responded well to TIPs and substituted store‐bought small sponge cakes, sweets and potato crisps with fruit or sweet potato. In Lower Egypt, where reported junk food and beverage consumption was higher, a greater proportion of mothers were willing and successfully able to carry out the recommendation of not feeding these foods to their children. Mothers were convinced of the harmful effects of junk foods (e.g. preservatives, lack of nutrients) and reported their children's positive reactions to eating fruit instead, which included the children ‘eating more’ and ‘eating better’. Mothers were motivated by the cost savings and children's improved health and appetite. Mothers and fathers expressed withholding junk foods has an economic benefit, of saving up to 40 Egyptian pounds per week (∼$5.00 US dollars), in comparison with purchasing traditional foods for the family, which are less costly. For example, 10 Egyptian pounds or ∼$1.43 US dollars is the approximate price per kilogram of lentils and 4 Egyptian pounds or ∼$0.57 US dollar is the approximate price per kilogram of tomatoes.

Mothers were at home, which may have facilitated the ability to carry out recommended practices in a short period of time. Mothers should be encouraged to feed a diverse diet, which includes adding fruits and vegetables, animal source foods, such as ground chicken liver or eggs, which are affordable, and the local available complementary food, seasamina, according to children's tastes. Mothers liked seasamina because of its affordability and ease in preparing this complementary food. Some mothers modified the practice to accommodate the food preferences of their children with regard to taste, texture and appearance.

This study demonstrated that grandmothers, fathers and health providers are important influencers of IYCF and should be involved in programmes to improve breastfeeding and complementary feeding (Aubel et al. 2004, Alive & Thrive 2010, Affleck & Pelto 2012). Cultural practices may contradict the recommendations of health providers or best practices for IYCF because of pressures from other family members.

Health providers repeatedly indicate that they leverage their experience and influential position as a means to positively influence IYCF practices. Yet some also encouraged junk food and beverage consumption when children refuse to eat or for perceived insufficient milk. Health providers continue to prescribe herbal drinks for prelacteal feeding and/or prior to 6 months of age to ‘calm’ babies. Only one‐quarter of mothers in this study exclusively breastfeed. Maintaining exclusive breastfeeding is challenging, as mothers, fathers, grandmothers and health providers do not recognize early introduction of herbal drinks and foods as a feeding problem, as long as mothers continue to breastfeed, which is highly valued. Continuing education is needed for health care providers and community health workers to counsel on insufficient breast milk, as well as to encourage health providers to not prescribe herbal drinks to children less than 6 months of age, including ensuring mothers and babies are not separated following childbirth can go far in remedying this problem.

Messages on breastfeeding and complementary feeding need to be given to mothers and their families who do not have this information to improve quantity, quality and frequency of meals within the context of reducing junk food. These messages should be disseminated through local organizations, community health workers and health care providers and reinforced through cooking classes and through maternal and child health clinics.

Community‐level strategies should prioritize educational messages that target mothers, fathers, grandmothers, health care providers to not feed junk foods – including sugary, salty foods and soft drinks – to children less than 2 years of age. Families should be advised that junk foods are detrimental to the growth of children and the entire family's health and well‐being. A national policy on junk food should be developed, stating that junk foods should not be given to children less than 2 years of age and should not be marketed to young children (World Health Organization 2010). To better understand the extent of junk food consumption in other countries, information should be routinely collected on junk foods through surveys (i.e. Demographic Health Survey) to capture the wide range of junk foods consumed (e.g. store‐bought small sponge cakes, chips, sugary drinks/soda, sugary biscuits) by children less than 2 years of age (Kavle et al. 2014).

Challenges and limitations

Not all recommended practices from TIPs worked well for mothers. Mothers tried practices for a short period of time. Although most mothers were able to adopt new practices for 1 week, a small number of mothers struggled with a few recommendations. Mothers were more successful in increasing fruits and vegetables than meats, which are typically eaten by families once to twice a week and are more expensive. Mothers not able to carry out the recommendations expressed: ‘I have no time to cook for my children’, ‘I have no free time’ and ‘I felt lazy’ while others relegated cooking to others; as one mother stated, ‘my mother‐in‐law cooks, so I don't cook’. Reducing snack food and beverage consumption is a challenge, as mothers often give these foods out of convenience.

In Egypt, older siblings play a role in feeding junk foods, such as sponge cakes, to young children when mothers are out of the home for short periods of time (i.e. to market). In another study using TIPs, junk foods were fed to young Malawian children when working mothers were away from home (USAID's Infant and Young Child Feeding Project 2011). Mothers and other caregivers need support and information to adequately feed children, regardless of working status (Roshita et al. 2012).

Seasamina is a promising and nutritious local complementary food that is affordable and available and can aid in improving dietary intake. Further work is needed to ascertain how variations of the recipe change nutrient content as well as considering mothers' concerns regarding lack of time as well as children's tastes and perceptions of colour and texture.

Conclusion

The intention of TIPs is to shift mothers' thinking, building on their motivations for making small changes in choosing to feed locally available high quality foods, while also taking ownership of their children's health. Future programmes and interventions should be prepared to build on successes and the challenges revealed through TIPs to achieve meaningful and sustained improvements in IYCF practices and to reduce junk food consumption, designed with cultural influences and beliefs in mind.

Source of funding

This study was funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the USAID‐funded Maternal and Child Integrated Program (MCHIP) Project under the cooperative agreement GHS‐A‐00‐08‐00002‐000.

Conflicts of interest

We have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributions

JAK was involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data and writing of the paper. SM, GS, MAF, DH, MR, was involved in collection, analyses, interpretation of data and writing of the paper. GK contributed to analyses, preparation of summaries of the data, and writing of the paper. RG was involved in study design, analysis, interpretation of data, and provided comments to drafts. All authors were involved in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank our Egypt‐based MCHIP/SMART project team, Dr. Issam Aldawi, Dr. Ali Abdelmegeid, and Mr. Farouk Salah, who organized field visits, initial community‐level meetings with local leaders and Community Development Associations, and identification of mothers, fathers, grandmothers, and health care providers through SMART project community health workers, which were instrumental in implementing this study. We acknowledge Sawsan El Sherief, a data analyst in aiding with identification and coding of themes with the study team, affiliated with American University in Cairo, Social Research Center. We acknowledge Dr. Valerie Flax, of the University of North Carolina, for her help with initial drafts of in‐depth interview guides.

Footnotes

Each 5 g sachet typically contains chamomile, thyme, licorice, anise and peppermint oil and is added to one‐fourth cup of water, boiled, cooled and given to the baby to drink following childbirth.

Tomato‐based vegetable stews cooked with meats and oil or samna (clarified butter).

References

- Abegunde D.O., Mathers C.D., Adam T., Ortegon M. & Strong K. (2007) The burden and costs of chronic diseases in low‐income and middle‐income countries. Lancet 370, 1929–1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adair L.S. (2012) How could complementary feeding patterns affect the susceptibility to NCD later in life? Nutrition, Metabolism & Cardiovascular Diseases 22, 765–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affleck W. & Pelto G.H. (2012) Caregivers' responses to an intervention to improve young child feeding behaviors in rural Bangladesh: a mixed method study of facilitators and barriers to change. Social Science & Medicine 75, 651–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alive & Thrive (2010) IYCF Practices, Beliefs and Influences in the SNNP Region, Ethiopia. Alive & Thrive: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson V.P., Cornwall J., Jack S. & Gibson R.S. (2008) Intakes from non‐breastmilk foods for stunted toddlers living in poor urban villages of Phnom Penh, Cambodia, are inadequate. Maternal and Child Nutrition 4, 146–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubel J., Touré I. & Diagne M. (2004) Senegalese grandmothers promote improved maternal and child nutrition practices; the guardians of tradition are not averse to change. Social Science & Medicine 59, 945–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black R.E., Victora C.G., Walker S.P., Bhutta Z.A., Christian P., de Onis M. et al (2013) Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low‐income and middle‐income countries. Lancet 382, 427–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey W.B. (1985) Temperament and increased weight gain in infants. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics 6, 128–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowart B., Beauchamp G. & Mennella J. (2011) Development of taste and smell in the neonate In: Fetal and Neonatal Physiology (eds Polin R.A., Fox W.W. & Abman S.H.), 4th edn Saunders: Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Darlington A.S.E. & Wright C.M. (2006) The influence of temperament on weight gain in early infancy. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics 27, 329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison B.A., Rockwell H.L. & Baker S.L. (1997) Excess fruit juice consumption by preschool‐aged children is associated with short stature and obesity. Pediatrics 99, 15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desor J.A., Maller O. & Turner R.E. (1973) Taste in acceptance of sugars by human infants. Journal of Comparative & Physiological Psychology 84, 496–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey K.G. & Brown K.H. (2003) Update on technical issues concerning complementary feeding of young children in developing countries and implications for intervention programs. Food & Nutrition Bulletin 24, 5–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicken K., Griffiths M. & Piwoz E. (1997) Design by Dialogue: A Program Planner's Guide to Consultative Research for Improving Young Child Feeding. Manoff Group and Academy for Educational Development: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Dundes A. (1992) Evil Eye: A casebook. University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI. [Google Scholar]

- Egyptian Cabinet's Information and Decision Support Centre & World Food Programme (2012) Egyptian food observatory. In: Egyptian Food Observatory. Cairo, Egypt. [Google Scholar]

- El‐Zanaty F. & Way A. (2009) Egypt Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Ministry of Health and Population, National Population Council, El‐Zanaty and Associates, and ORC Macro: Cairo, Egypt. [Google Scholar]

- Engle‐Stone R., Ndjebayi A.O., Nankap M. & Brown K.H. (2012) Consumption of potentially fortifiable foods by women and young children varies by ecological zone and socio‐economic status in Cameroon. The Journal of Nutrition 142, 555–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (2006) The double burden of malnutrition: Case studies from six developing countries. FAO Food and Nutrition Paper 84, 1–334. Rome, Italy. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization & World Health Organization (2008) Interim Summary of Conclusions and Dietary Recommendations on Total Fat and Fatty Acids. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Geerlings H. (2007) Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza: A Rapid Assessment of the Socio‐Economic Impact on Vulnerable Households in Egypt. Food and Agriculture Organization: Cairo, Egypt. [Google Scholar]

- Geleijnse J.M., Hofman A., Witteman J.C., Hazebroek A.A., Valkenburg H.A. & Grobbee D.E. (1997) Long‐term effects of neonatal sodium restriction on blood pressure. Hypertension 29, 913–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]