Abstract

Prenatal iron supplementation is recommended to control anaemia during pregnancy. Low compliance and side effects have been claimed as the main obstacles for adequate impact of the supplementation. As part of a double‐blind supplementation study carried out in a hospital located in a shantytown in Lima, Peru, we monitored compliance throughout pregnancy and evaluated factors associated with variation in compliance over time. Overall, 985 pregnant women were enrolled in a supplementation study that was administered through their prenatal care from 10 to 24 weeks of gestation until 4 weeks postpartum. They received 60 mg iron and 250 µg folate with or without 15 mg zinc. Women had monthly care visits and were also visited weekly to query regarding compliance, overall health status, and potential positive and negative effects of supplement consumption. Median compliance was 79% (inter‐quartile range: 65–89%) over pregnancy, and the median number of tablets consumed was 106 (81–133). Primpara had lower average compliance; positive health reports were associated with greater compliance, and negative reports were associated with lower compliance. There was no difference by type of supplement. Women with low initial compliance did achieve high compliance by the end of pregnancy, and women who reported forgetting to take the supplements did have lower compliance. Compliance was positively associated with haemoglobin concentration at the end of pregnancy. In conclusion, women comply highly with prenatal supplementation within a prenatal care model in which supplies are maintained and reinforcing messages are provided.

Keywords: prenatal iron supplementation, compliance, anaemia, side effects, Peru

Introduction

Universal iron supplementation during pregnancy is one of the principal nutritional components of prenatal care services throughout Latin America and the world. Iron supplementation during pregnancy is recommended to prevent the occurrence of low haemoglobin concentration (<100 g L−1) in late pregnancy (Kulier et al. 1998), which presents a risk to women if they need surgery at delivery. Cumulative evidence demonstrates the efficacy of prenatal iron or iron and folic supplementation in preventing approximately 80% of low hemoglobin concentration at the end of pregnancy and 39% of delivery‐associated transfusions (Kulier et al. 1998; Pena‐Rosas & Viteri 2009).

Despite demonstrated efficacy and widespread policies and programs for prenatal iron supplementation, there remains a perception that such programs are not effective (Galloway & McGuire 1994; Galloway et al. 2002). Reasons given for the low effectiveness of these programs include (1) low compliance due to inadequate patient motivation; (2) low motivation of health personnel; (3) low coverage of the health system; (4) side effects; (5) inadequate supplies of tablets; and (6) lack of patient understanding of the role of iron supplements in preventing anaemia (Galloway & McGuire 1994; Galloway et al. 2002). Compliance with prenatal iron, iron + folic acid, or multiple micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy has been studied in diverse settings, and some have examined factors associated with compliance (Schultink et al. 1993; Ekstrom et al. 1996; Aguayo et al. 2005; Seck & Jackson 2007; Lutsey et al. 2008; Kulkarni et al. 2009; Zeng et al. 2009). Here we add to that literature by examining patterns of compliance with iron and folic acid supplementation among low‐income Peruvian women seeking prenatal care administered through a public health facility.

Key message

The findings here indicate that Peruvian women comply with prenatal supplementation consuming their supplements 5.5 days out of 7.

This work confirms other studies showing high levels of compliance.

Compliance was more variable during the initial months and was lower among primipara, and was greater among those who reported positive effects of supplement consumption and lower among those who reported negative effects.

Physicians, midwives, nutritionists and health care workers should consider these factors when promoting supplement use and monitoring compliance throughout pregnancy.

Materials and methods

This project was conducted from 1995 to 1997 as a prenatal supplementation trial in Villa El Salvador, a peri‐urban community in the southern part of Lima, Peru. During this time, 1295 pregnant women receiving prenatal care in a Maternity Hospital located in that community participated in a double‐masked study of prenatal zinc supplementation. Eligible women where those who began prenatal care between 10 and 24 weeks gestation, were considered healthy with a singleton low‐risk pregnancy, were living in the community, and had been living in Lima or other coastal regions of Peru for at least 6 months prior to pregnancy. Signed informed consent was obtained from each woman at enrolment. The protocol was approved by the Ethical Committees at the Instituto de Investigación Nutricional (IIN) in Lima, Peru, and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland.

At enrolment, women were randomized within parity (nullipara or multipara), and gestational age (<17 weeks or ≥17 weeks gestation) to receive one of two supplements. Gestational age was determined based on maternal reporting of date of last menses, as well as by clinical indications of pregnancy duration at enrolment (detection of fetal heart sounds and/or fetal movements; fundal height measure; ultrasound). The supplements contained 60 mg iron (as ferrous sulphate) and 250 µg folic acid with or without 15 mg zinc (as zinc sulphate). They had the same appearance and taste, and neither the subjects, the health personnel nor the investigative team knew the coding scheme until analyses of the data were completed.

The supplementation trial was designed to follow the protocol of prenatal care and not alter the daily work of the health personnel at the hospital. Women received their supplements as part of their regular monthly prenatal care appointment with the recommendation to take one tablet every day, between meals (11 am or 3 pm were suggested), together with lemonade, an available juice rich in ascorbic acid, or water. Women were advised that they might experience some temporary side effects (e.g. stomach discomfort and constipation), but that these would not indicate any health problem. In such cases, women were advised to take the supplements after lunch or dinner for several days until the side effects disappeared. A pamphlet with information and instructions was given to each woman to take home. At the health center, posters were dispayed which promoted prenatal iron supplementation.

The number of tablets given to each woman was monitored on a monthly basis at the clinic. Field workers visited the women in their homes twice per month to inquire about their general health and supplement consumption. The field workers also checked the blister packs to count the number of tablets taken and inquired whether women had experienced any of a number of potential benefits or side effects since the last visit. The reported benefits were: ‘feels better’, described in general as feeling good, healthy, confident that she is OK; ‘feels more energetic’, in doing her work at home or other physical work; increased appetite or hunger, eating more; and any other reported benefit. The side effects were: darkened faeces; pirosis or stomach discomfort; nausea; constipation; headache; and any other reported symptom. The field workers were trained to respond to minor concerns regarding side effects, and to motivate women. We did not watch women consume their supplements, and thus we are analyzing reported compliance with supplementation. We also did not ask women for specific details, such as the time of day or whether they took the tablets with juice as opposed to water.

During the study, information was collected on maternal socio‐demographic characteristics, clinical history, and the evolution and outcome of the pregnancy. Anthropometric measures, including weight, height, circumferences and skinfold thicknesses, as well as biochemical indicators (haemoglobin, serum ferritin, serum and urinary zinc) were determined at enrolment, 28–30 weeks and 37–38 weeks gestation. A blood sample was also taken from the umbilical cord at delivery to characterize neonatal iron and zinc status. The overall study has been previously described, as well as the changes in iron and zinc status in sub‐samples of these women (Caulfield et al. 1999a; Zavaleta et al. 2000).

Of the 1295 pregnant women initially enrolled in the supplementation trial, 1016 remained in the study until delivery (Caulfield et al. 1999b). Here, we present data on 985 women completing the study for whom we also have data on relevant maternal demographic and socioeconomic characteristics for this analysis. The actual number of women contributing information varies by month of gestation, due to variations in week of gestation at enrolment and delivery, as well as missing data on supplement consumption for enrolled women when they were not available for a particular home visit.

For analyses, we calculated several measures of compliance. The overall compliance of each woman was calculated as the ratio of the reported number of tablets consumed from enrolment through the final home visit (within 1 week of delivery), over the total number of days adjusted for any missing days of observation (home visits). It can be conceptualized as a per cent or as the number of tablets taken per 100 days of pregnancy. Because women take one supplement per day, compliance also refers to consumption as a per cent of tablets provided. We also calculated compliance for each month of a woman's pregnancy (gestation month 3, 4, etc.), as well as for each study month so that we could examine variation in compliance as women began taking their supplements. Because the distribution of compliance was not normal, we report the median and inter‐quartile range. For regression analyses, we transformed the compliance ratio using the natural logarithm of 1+ value.

Initial analyses revealed greater variability in compliance across women during their initial month of supplementation, and, therefore, we conducted analyses stratified by quartiles of compliance during the first month of supplementation. We examined the frequency of reporting of each positive or negative health response for each month of pregnancy, and over the entire pregnancy. Only a subset of these responses was related to compliance either monthly or over the entire pregnancy. Because the results did not differ between monthly analyses and the entire pregnancy, we chose to use the comprehensive measures in the analyses. We fit a longitudinal model to examine the pattern of compliance over gestation and to identify influences on compliance (log transformed for analyses). A random effect was added to the model to allow for variability in compliance across women at the beginning of the study. We retained factors in the model if they were statistically significant or were structural features of the study (i.e. type of supplement) Haematologic data were available during pregnancy on a sub‐sample of 638 women (Zavaleta et al. 2000). In this sub‐sample, we examined whether anaemia affected compliance, and whether compliance was associated with mean haemoglobin concentration or the risk of low haemoglobin at the end of pregnancy. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Data analyses were accomplished using Statistical Analysis System Version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Selected characteristics of the 985 women are presented in Table 1. On average, the women were 16 weeks gestation at enrolment, and nearly one‐half were having their first baby. Most women had access to basic community services such as electricity and water about 50% had completed high school education.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of 985 Peruvian women at entry into prenatal care and the study (10–24 weeks gestation)

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 24.6 ± 5.4 |

| Gestational age (week) | 16.1 ± 4.6 |

| Height (cm) | 151.4 ± 5.6 |

| Weight (kg) | 55.2 ± 8.2 |

| Body mass index (kg m−2) | 24.1 ± 3.3 |

| Single (%) | 14.8 |

| Parity (%) | |

| 0 | 45.0 |

| 1 | 28.6 |

| 2–3 | 20.9 |

| 4+ | 5.5 |

| Education (%) | |

| Primary | 7.8 |

| Incomplete secondary | 40.5 |

| Secondary | 30.8 |

| Secondary+ | 20.9 |

| In‐home services (%) | |

| Potable water | 56.6 |

| Sewage | 64.0 |

| Electricity | 78.2 |

| Housing material (%) | |

| Cardboard | 25.9 |

| Wood | 16.2 |

| Brick | 57.9 |

Overall, median compliance with supplementation was 79%, with an inter‐quartile range of 65–89%. In terms of the number of tablets consumed, this translated into a median number of tablets consumed of 106 (81 to 133). The distribution of compliance with supplementation varied by month of gestation and rose toward the end of pregnancy (Table 2). Median compliance varied from 76% to 87% during the pregnancy. Each month 25% of women consumed 90–100% of the tablets provided, but 25% consumed less than 53–63% of the tablets provided during pregnancy. There were no differences in compliance by type of supplement consumed. Initially, approximately 60% of women reported forgetting to take their supplements, the proportion declining progressively to 52% in the ninth month of pregnancy.

Table 2.

Median and inter‐quartile distribution of compliance with supplementation by month gestation among Peruvian women

| Gestation (mo) | n | Compliance percentile | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 75th | 50th | 25th | ||

| 3 | 289 | 95.0 | 80.8 | 58.3 |

| 4 | 533 | 92.3 | 76.3 | 55.6 |

| 5 | 770 | 96.4 | 82.4 | 58.6 |

| 6 | 870 | 96.2 | 81.6 | 56.7 |

| 7 | 897 | 95.2 | 82.4 | 62.1 |

| 8 | 888 | 96.4 | 82.1 | 57.1 |

| 9 | 714 | 100.0 | 87.3 | 63.6 |

Presented in Table 3 are the monthly maternal reports of each positive or negative health response. As expected, darkened faeces was reported by women 90% of the time, and did not vary across pregnancy or by type of supplement consumed. As shown, many of the negative responses declined and the reporting of positive responses increased as pregnancy progressed.

Table 3.

Maternal health reports by month of gestation, collected during home surveillance using a structured questionnaire

| Maternal report (%) | Gestation (mo) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Negative | |||||||

| Constipation | 42 | 43 | 34 | 33 | 33 | 29 | 27 |

| Bothers | 64 | 59 | 52 | 51 | 54 | 49 | 51 |

| Nausea | 68 | 46 | 31 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 25 |

| Diarrhoea | 8 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 18 | 16 | 16 |

| Headache | 56 | 51 | 37 | 34 | 39 | 36 | 35 |

| Darkened stool | 89 | 88 | 90 | 91 | 94 | 92 | 90 |

| Positive | |||||||

| Feel good/better | 81 | 91 | 91 | 94 | 95 | 88 | 84 |

| Good/better appetite | 78 | 88 | 92 | 92 | 96 | 95 | 93 |

| Good/more energy | 67 | 83 | 85 | 89 | 90 | 84 | 73 |

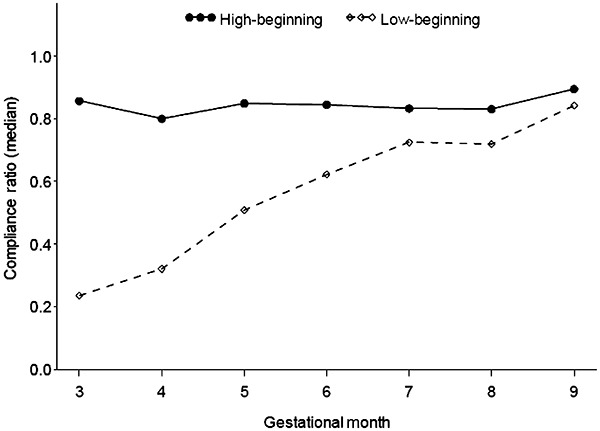

Presented in Table 4 are the results of the regression analysis describing the influences on overall compliance and the changes in compliance across pregnancy. Only significant factors were retained, with the exception of type of supplement consumed and the month when supplementation began (3–5th month of pregnancy), which were retained as structural features of the study. Maternal age, education or access to community services did not influence compliance with prenatal supplements, nor did maternal body mass index or other nutritional variables. Primiparity was the only maternal factor associated with compliance, and it was associated with lower compliance with supplementation. As shown, there was an interaction between initial low compliance and changes in compliance over the course of pregnancy. Women in the lowest quartile of consumption during their first month (identified here as low) increased their consumption to levels reported by the rest of women throughout pregnancy (see Fig. 1). Reasons for the initial low compliance were not identified amongst those factors examined (analyses not shown). Maternal compliance was negatively affected by reports of nausea, and was positively affected by reports of feeling good/better and of good appetite. Women reporting forgetting to take the supplement also had lower compliance; adding this variable to the model reduced the negative effect of nausea on the compliance ratio, but did not affect other variables in the model.

Table 4.

Factors associated with compliance † with antenatal supplementation among Peruvian women

| Factors | Estimate | Standard error |

|---|---|---|

| Gestational month | 0.054* | 0.003 |

| Low‐beginning group (0 vs. 1) | 0.149* | 0.008 |

| Interaction of low‐beginning group and gestational month (0 vs. 1) | −0.055* | 0.004 |

| Primiparity | −0.017* | 0.006 |

| Forgetting to take | −0.424* | 0.047 |

| Positive reports of well‐being | ||

| Better | 0.219* | 0.071 |

| Appetite | 0.307* | 0.074 |

| Negative reports of well‐being | ||

| Nausea | −0.086* | 0.041 |

*P < 0.05. †Natural logarithm of compliance ratio.

Figure 1.

Median compliance with prenatal supplementation among Peruvian women during pregnancy by initial level of compliance.

In the sub‐sample of women with haematologic data, anaemia at enrolment or mid‐pregnancy was not associated with the subsequent pattern of compliance. Overall compliance, however, was positively associated with haemoglobin concentration at the end of pregnancy (r = 0.17; P < 0.01). Further, the risk of ending pregnancy with a low haemoglobin concentration was diminished with increasing levels of compliance. Women who took six tablets per week instead of five per week over pregnancy (a difference in compliance of 15%) reduced their risk of ending pregnancy with a low haemoglobin by 34% (95% CI: 21–46%).

Discussion

Routine iron supplementation during pregnancy has been recommended to prevent or control maternal anaemia for decades. In 1998, the International Consultative Group on Nutritional Anemias (INACG) produced new guidelines for iron supplementation during pregnancy, recommending that prenatal iron supplements be reduced from 120 mg day−1 to 60 mg day−1, and be taken for 6 months during pregnancy in areas where the underlying prevalence of anaemia is <40% (Stoltzfus & Dreyfuss 1998). This study provides a description of compliance with this recommendation as implemented through an enhanced prenatal care delivery system in a low‐income population in Lima, Peru.

Low compliance and multiple side effects are often cited as factors limiting the effectiveness of this intervention implemented through the primary health system (Galloway & McGuire 1994; Galloway et al. 2002). Yet in reality, patterns of compliance with prenatal supplementation have changed over time, as evidenced by the more recent literature. In our study, women took their supplements 79 of the time, which on a weekly basis means they consumed a supplement 5.5 days week−1. This level of compliance is in line with the estimated compliance of 70–95% reported in other recent studies from other resource‐constrained settings (Aguayo et al. 2005; Seck & Jackson 2007; Lutsey et al. 2008; Kulkarni et al. 2009; Zeng et al. 2009).

We assessed whether positive or negative effects of supplementation perceived by women affected their compliance. Perceived positive health effects of iron supplements (feeling better and good appetite) positively affected compliance, whereas reports of nausea negatively affected compliance throughout pregnancy. Interestingly, neither diarrhoea nor constipation – both considered negative side effects of iron supplements (at higher doses) – was found to significantly affect compliance during pregnancy. Again, these results are consistent with other studies examining this influence on compliance (Seck & Jackson 2007; Lutsey et al. 2008; Kulkarni et al. 2009). We also examined interactions with month of pregnancy to determine if some factors, such as nausea, differentially affected compliance over time, e.g. during early pregnancy, but none were found to be statistically significant. Overall, the effects of positive or negative perceptions regarding supplements are average influences and do not alter our conclusions regarding the overall high level of compliance with supplementation. As shown here and in line with the results of other studies, negative side effects did not keep women from taking their supplements (Galloway et al. 2002).

Importantly, we found that mothers sometimes forget to take their supplements and this lowers compliance. This is also reported in at least three other studies (Seck & Jackson 2007; Lutsey et al. 2008; Kulkarni et al. 2009). We did find that adding this variable to the model reduced the negative impact of reported nausea on compliance, suggesting that these two factors may somehow be linked in their relationship with compliance. These results likely confirm the importance of follow up with women and reinforcement regarding consumption of supplements through counselling, other aspects of the care setting or through community initiatives.

Several studies identified various maternal characteristics associated with variation in compliance. These included maternal age, education, income, marital status, caste, smoking and drinking (Ekstrom et al. 1996; Aguayo et al. 2005; Seck & Jackson 2007; Lutsey et al. 2008; Kulkarni et al. 2009). In contrast, we did not find that younger or older maternal age or low education or other maternal factors affected compliance. We did find lower average compliance among primiparous women, which is somewhat consistent with these findings, and with the finding from one study (Lutsey et al. 2008) that prior experience with iron supplements positively affected compliance.

Our study is unique in that we examined compliance monthly throughout pregnancy. This allowed us to demonstrate that compliance was high throughout pregnancy and to detect an average trend of increasing compliance. We found greater variability in compliance during the first month of supplementation, and examined changes over time in women who initially had low compliance (<25% of tablets consumed). We found that these women increased rapidly their compliance over time, achieving by the end of pregnancy levels of compliance of women who complied highly with the recommendation throughout pregnancy. Within the care setting of this study, messages from prenatal care providers to reinforce the consumption of the supplements in order to prevent anaemia and its complications would have had an influence on compliance, along with messages from health workers during home visits to pregnant women to reinforce the messages given at health centre and to address problems, such as constipation or stomach pain, that women commonly attribute to iron pills. Although we cannot link this data directly, it is likely that such efforts resulted in the rise in compliance over pregnancy and especially among women with low initial compliance.

Importantly, we did not find that adding 15 mg elemental zinc (zinc sulphate) to the tablets containing 60 mg iron (as ferrous sulphate) and folic acid affected compliance. Similarly, studies comparing compliance across supplements involving multiple micronutrients have not detected differences in compliance, suggesting that the various prenatal formulations available are generally accepted by women.

Two strengths of the study are its relatively large sample size and the longitudinal nature of the data enabling us to characterize compliance over the course of pregnancy, as well as the influence of various factors on its course. The study is limited by the lack of information on the specific nature of the counselling received by women as well as summary reports by women on their experience of taking supplements.

In summary, this study demonstrates that when iron supplements are available and the health care setting promotes their consumption, the majority of women do take their supplements on a regular basis during pregnancy. Women who start out with low compliance do improve over time within this care setting, reaching the average level of compliance during the third trimester of pregnancy. Maternal assessments of the positive and negative effects of supplement consumption each affect compliance during pregnancy in anticipated ways. Further research is needed to continue to identify and refine best practices for optimizing compliance with prenatal supplements within the prenatal care setting.

Source of funding

The original study was supported by DAN‐5116‐A‐00–8051‐00 and HRN‐A‐00–97‐00015‐00, Cooperative Agreements between USAID/OHN and The Johns Hopkins University.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Contributions

NZ and LC directed the original study, as well as the analysis and interpretation of the data and preparation of the manuscript. AF participated in the original study, and contributed to the interpretation of the results. PC contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the women who volunteered to participate in this study. We thank the Director and Personnel of the Obstetric Ward at the Mother and Child Health Center Cesar Lopez Silva in Villa El Salvador, Lima, Peru, for their collaboration in the project. We also thank the Health Authorities of the Ministry of Health, especially those from DISA Lima Sur and MICRORED/Villa El Salvador‐LP for allowing us the use of their medical facilities. We thank the rest of the research team for their excellent care of the participating women and their babies.

References

- Aguayo V.M. , Kone D. , Bamba S.I. , Diallo B. , Sidibe Y. , Traore D. et al . ( 2005. ) Acceptability of multiple micronutrient supplements by pregnant and lactating women in Mali . Public Health Nutrition 8 , 33 – 37 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield L.E. , Zavaleta N. & Figueroa A. ( 1999a. ) Adding zinc to prenatal iron and folate supplements improves maternal and neonatal zinc status in a Peruvian population . The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 69 , 1257 – 1263 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield L.E. , Zavaleta N. , Figueroa A. & Leon Z. ( 1999b. ) Adding zinc to prenatal iron and folate supplements does not affect duration of pregnancy or size at birth in Peru . The Journal of Nutrition 129 , 1563 – 1568 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom E.C. , Kavishe F.P. , Habicht J.P. , Frongillo E.A. Jr , Rasmussen K.M. & Hemed L. ( 1996. ) Adherence to iron supplementation during pregnancy in Tanzania; determinants and hematologic consequences . The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 64 , 368 – 372 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway R. & McGuire J. ( 1994. ) Determinants of compliance with iron supplementation: supplies, side effects, or psychology? Social Science & Medicine (1982) 39 , 381 – 390 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway R. , Dusch E. , Elder L. , Achadi E. , Grajeda R. , Hurtado E. et al . ( 2002. ) Women's perceptions of iron deficiency and anaemia prevention and control in eight developing countries . Social Science & Medicine (1982) 55 , 529 – 544 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulier R. , De Onis M. , Gulmezoglu A.M. & Villar J. ( 1998. ) Nutritional interventions for the prevention of maternal morbidity . International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 63 , 231 – 246 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni B. , Christian P. , LeClerq S.C. & Khatry S.K. ( 2009. ) Determinants of compliance to antenatal micronutrient supplementation and women's perceptions of supplement use in rural Nepal . Public Health Nutrition 13 , 82 – 90 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutsey P.L. , Dawe D. , Villate E. , Valencia S. & Lopez O. ( 2008. ) Iron supplementation compliance among pregnant women in Bicol, Philippines . Public Health Nutrition 11 , 76 – 82 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena‐Rosas J.P. & Viteri F.E. ( 2009. ) Effects and safety of preventive oral iron or iron + folic acid supplementation of women during pregnancy . Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews ( 4 ), CD004736 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultink W. , Van Der Ree M. , Matulessi P. & Gross R. ( 1993. ) Low compliance with an iron supplementation program: a study among pregnant women in Jakarta, Indonesia . The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 57 , 135 – 139 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seck B.C. & Jackson R.T. ( 2007. ) Determinants of compliance with iron supplementation among pregnant women in Senegal . Public Health Nutrition 3 , 1 – 10 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltzfus R.J. & Dreyfuss M.L. ( 1998. ) Guidelines for the Use of Iron Supplements to Prevent and Treat Iron Deficiency Anemia . International Nutritional Anemias Consultative Group, United Nations Childrens Fund, World Health Organization . International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) Press; : Washington, DC . [Google Scholar]

- Zavaleta N. , Caulfield L.E. & Garcia T. ( 2000. ) Changes in iron status during pregnancy in Peruvian women receiving prenatal iron and folate supplements with or without zinc . The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 71 , 956 – 961 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L. , Yan H. , Cheng Y. , Dang S. & Dibley M.J. ( 2009. ) Adherence and costs of micronutrient supplementation in pregnancy in a double‐blind, randomized, controlled trial in rural western China . Food Nutrition Bulletin 30 ( 4 Suppl .), S480 – S487 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]