Abstract

Introduction

Oral semaglutide is the first orally administered glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, and has been evaluated in the PIONEER clinical trial program. These trials assessed the proportions of patients achieving single and composite endpoints, encompassing glycemic control [defined in terms of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c)], weight loss, and hypoglycemia. The present study assessed the cost of control with oral semaglutide versus empagliflozin, sitagliptin, and liraglutide in the US.

Methods

Four endpoints were evaluated: (1) HbA1c ≤ 6.5%; (2) HbA1c < 7.0%; (3) ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction and weight loss ≥ 3.0%; and (4) HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia and without weight gain. The proportions of patients achieving each endpoint were sourced from the PIONEER 2, 3 and 4 trials. Treatment costs were accounted over an annual time-period in 2019 US dollars (USD), based on wholesale acquisition cost. Cost of control was calculated by dividing treatment costs by the proportion of patients achieving each target.

Results

Oral semaglutide was consistently associated with the lowest cost of control for all four endpoints. For the targets of HbA1c ≤ 6.5% and HbA1c < 7.0%, oral semaglutide 14 mg was associated with lower cost of control than empagliflozin 25 mg, sitagliptin 100 mg and liraglutide 1.8 mg by USD 15,036, 14,697, and 6996, respectively, and USD 931, 346 and 4497, respectively. For the double composite endpoint, cost of control was lower with oral semaglutide 14 mg by USD 525, 32,277 and 13,011, respectively versus empagliflozin 25 mg, sitagliptin 100 mg and liraglutide 1.8 mg. For the triple composite endpoint, cost of control was lower with oral semaglutide 14 mg by USD 1255, 7510 and 5774, respectively.

Conclusion

Oral semaglutide was associated with lower cost of bringing patients with type 2 diabetes to four clinically-relevant treatment targets versus empagliflozin, sitagliptin, and liraglutide in the US.

Funding

Novo Nordisk A/S.

Keywords: Costs and cost analysis, Cost-effectiveness, Cost of control, Diabetes mellitus, GLP-1 receptor agonist, Oral semaglutide, United States

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Modern type 2 diabetes treatment guidelines recommend not only maintaining glycemic control [defined in terms of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c)] but also avoiding weight gain and hypoglycemic events. |

| The present analysis assessed the short-term cost-effectiveness of oral semaglutide versus empagliflozin 25 mg, sitagliptin 100 mg and liraglutide 1.8 mg for treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes, in terms of the cost per patient achieving four clinically-relevant treatment targets in the US setting. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Oral semaglutide was consistently associated with the lowest cost of control versus all comparators for all endpoints of HbA1c ≤ 6.5%, HbA1c < 7.0%, ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction and weight loss ≥ 3.0%, and HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia and without weight gain. |

| Oral semaglutide 14 mg represents a cost-effective treatment option versus empagliflozin 25 mg, sitagliptin 100 mg, and liraglutide 1.8 mg for bringing patients with type 2 diabetes to clinically-relevant treatment targets in the US. |

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus represents a significant healthcare challenge in the US, with 24.7 million people with a diagnosis, leading to direct healthcare expenditure of US dollars (USD) 237 billion and USD 90 billion in lost productivity in 2017 [1]. People with diabetes were estimated to have direct healthcare costs 2.3 times higher than people without diabetes [1]. Choosing therapies for diabetes that are both effective and cost-effective is key to minimizing the humanistic and economic burden associated with diabetes-related complications.

Controlling blood sugar levels remains the primary aim of treatment for diabetes, with landmark studies, such as the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study showing that improvements in glycemic control reduce the risk of micro- and macrovascular complications in people with type 2 diabetes [2, 3]. The American Diabetes Association suggests a glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) target of < 7.0% for many people with diabetes, with this individualized depending on the risk of adverse effects of treatment (such as hypoglycemia), disease duration, life expectancy, comorbidities, patient preference, and available support [4]. Recently issued treatment guidelines suggest a more rounded, patient-centered approach to the treatment of diabetes, with all overweight or obese people with diabetes recommended to lose weight, and that the impact of medications on body weight and hypoglycemia risk should be considered [5–7]. Furthermore, interventions associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease as demonstrated in cardiovascular outcomes trials are preferred, particularly for patients at high risk of these events [7].

A number of modern interventions for type 2 diabetes that continue to primarily target glycemic control, but have additional benefits by addressing other risk factors for complications are available to clinicians and patients. These include glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors. GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as once-weekly semaglutide, liraglutide, exenatide and dulaglutide, have been shown to have high efficacy in terms of glycemic control, and are associated with weight loss and low risk of hypoglycemia [6]. DPP-4 inhibitors, such as sitagliptin, are associated with intermediate efficacy in terms of glycemic control, are weight neutral and have a low risk of hypoglycemia [6]. SGLT-2 inhibitors, such as empagliflozin, canagliflozin and dapagliflozin, are considered to have intermediate efficacy for glycemic control, and are associated with weight loss and a low risk of hypoglycemia [6]. Oral semaglutide is the first GLP-1 receptor agonist developed for oral administration, using an absorption enhancer to facilitate absorption across the gastric mucosa [8–12]. Oral semaglutide aims to provide the benefits of existing GLP-1 receptor agonists, without the requirement for daily or weekly injections.

The PIONEER trial program compared oral semaglutide with a number of interventions for type 2 diabetes, including empagliflozin 25 mg (PIONEER 2), sitagliptin 100 mg (PIONEER 3), and liraglutide 1.8 mg (PIONEER 4) [9–12]. In these studies, the primary endpoint was change from baseline in HbA1c after 26 weeks of treatment evaluated by the treatment policy estimand, and oral semaglutide 14 mg was associated with a superior reduction in HbA1c compared with empagliflozin 25 mg and sitagliptin 100 mg, and a non-inferior reduction in HbA1c compared with liraglutide 1.8 mg. When change in body weight was evaluated using the treatment policy estimand, oral semaglutide 14 mg was associated with superior weight loss compared with sitagliptin 100 mg and liraglutide 1.8 mg. Across the three trials, rates of hypoglycemic events were low with oral semaglutide 14 mg, empagliflozin 25 mg, sitagliptin 100 mg and liraglutide 1.8 mg. The three trials also collected data on the proportions of patients achieving a series of treatment targets, including the single endpoints of HbA1c ≤ 6.5% and HbA1c < 7.0%, a double composite endpoint of ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction and weight loss ≥ 3.0%, and a triple composite endpoint of HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia and without weight gain. These treatment targets allow the efficacy of interventions to be assessed in a manner highly relevant to modern treatment of type 2 diabetes.

The present analysis assessed the short-term cost-effectiveness of oral semaglutide versus empagliflozin 25 mg, sitagliptin 100 mg and liraglutide 1.8 mg for treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes, in terms of the cost per patient achieving treatment targets in the US setting. The primary analyses assessed the cost per patient achieving four endpoints: (1) HbA1c ≤ 6.5%, (2) HbA1c < 7.0%, (3) ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction and weight loss ≥ 3.0%, and (4) HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia and without weight gain.

Methods

Clinical Data

Data on the proportion of patients achieving the four endpoints: (1) HbA1c ≤ 6.5%, (2) HbA1c < 7.0%, (3) ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction and weight loss ≥ 3.0%, and (4) HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia and without weight gain were taken from the PIONEER 2, 3 and 4 clinical trials for comparison of oral semaglutide 14 mg with empagliflozin 25 mg, sitagliptin 100 mg and liraglutide 1.8 mg, respectively [9–12]. The PIONEER 2 and 3 trials enrolled patients with diabetes with HbA1c values between 7.0% and 10.5%, and PIONEER 4 enrolled patients with diabetes with HbA1c values between 7.0% and 9.5%. In PIONEER 2, patients were receiving metformin monotherapy before randomization, whereas patients were receiving metformin with or without a sulfonylurea in PIONEER 3, and metformin with or without an SGLT-2 inhibitor in PIONEER 4. The present cost of control analysis used observed proportions of patients achieving targets at 26 weeks regardless of discontinuation and addition of rescue medication (Table 1).

Table 1.

Observed proportion, % (standard error) of patients achieving treatment targets at 26 weeks

| PIONEER 2 | Oral semaglutide 14 mg | Empagliflozin 25 mg |

|---|---|---|

| HbA1c ≤ 6.5% | 47 (3)* | 17 (2) |

| HbA1c < 7.0% | 67 (2)* | 40 (2) |

| ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction and weight loss ≥ 3.0% | 45 (3)* | 28 (2) |

| HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia, and no weight gain | 60 (2)* | 36 (2) |

| PIONEER 3 | Oral semaglutide 14 mg | Sitagliptin 100 mg |

|---|---|---|

| HbA1c ≤ 6.5%a | 37 (2)* | 14 (2) |

| HbA1c < 7.0% | 56 (2)* | 32 (2) |

| ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction and weight loss ≥ 3.0% | 38 (2)* | 10 (1) |

| HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia, and no weight gain | 48 (2)* | 20 (2) |

| PIONEER 4 | Oral semaglutide 14 mg | Liraglutide 1.8 mg |

|---|---|---|

| HbA1c ≤ 6.5% | 48 (3) | 43 (3) |

| HbA1c < 7.0% | 68 (3) | 62 (3) |

| ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction and weight loss ≥ 3.0% | 47 (3)* | 34 (3) |

| HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia, and no weight gain | 61 (3) | 54 (3) |

Values are observed proportion, % (standard errors) of patients achieving each treatment target based on week 26 data regardless of discontinuation and addition of rescue medication

HbA1c glycated hemoglobin

*Statistically significant difference at the 95% confidence level based on the estimated odds-ratio (evaluated by the treatment policy estimand) [9–12]

aData not previously presented, based on data on file. Standard errors have not previously been presented, based on data on file

Cost Data

Costs with oral semaglutide 14 mg, empagliflozin 25 mg, sitagliptin 100 mg, and liraglutide 1.8 mg were accounted over an annual time period, based on wholesale acquisition cost (WAC; Table 2) [13]. All interventions were dosed at the highest recommended daily doses, as per the PIONEER 2, 3, and 4 trial protocols. Liraglutide 1.8 mg was associated with one needle per day for injection, but all other interventions were associated with no needle use. Costs relating to self-monitoring of blood glucose were not included, as resource use was not expected to differ between the treatment arms. Costs associated with additional anti-diabetic medications and discontinuation of study treatments were not incorporated in the analyses.

Table 2.

Wholesale acquisition cost applied in the analysis

| Medication | Pack contents | Days per pack | Pack price (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral semaglutide 14 mg | 420 mg | 30 | 772.43 |

| Empagliflozin 25 mg | 750 mg | 30 | 492.85 |

| Sitagliptin 100 mg | 3000 mg | 30 | 451.20 |

| Liraglutide 1.8 mg | 54 mg | 30 | 921.78 |

| Needles for injection of liraglutide (NovoFine 30G) | 100 needles | – | 39.41 |

Costs taken from the IBM Micromedex. RED BOOK in September 2019 [13]

USD 2019 United States dollars

Assessment of Cost-Effectiveness

The short-term cost-effectiveness of oral semaglutide 14 mg versus empagliflozin 25 mg, sitagliptin 100 mg, and liraglutide 1.8 mg was assessed using a cost of control model developed in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). Outcomes were assessed for four pre-specified endpoints in the primary analysis: a single endpoint of HbA1c ≤ 6.5%, a single endpoint of HbA1c < 7.0%, a double-composite endpoint of ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction and weight loss ≥ 3.0%, and a triple-composite endpoint of HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia and without weight gain (Table 1). The cost of control with each intervention for each endpoint was calculated by dividing the annual treatment costs by the proportion of patients achieving each target (observed proportions of patients achieving targets at 26 weeks using data regardless of discontinuation and addition of rescue medication). This approach allows the short-term cost-effectiveness of interventions to be evaluated in a clinically-relevant manner that is both straightforward and transparent. Analyses using this approach have been previously published in the peer-reviewed literature [14–17].

Costs were accounted in 2019 USD, from the perspective of a healthcare payer in the US. Outcomes were not projected beyond a 1-year time horizon, and therefore cost and clinical outcomes were not discounted.

Sensitivity Analyses

A probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was performed using a second-order Monte Carlo approach, with sampling around the base case clinical inputs based on the standard errors of the proportions of patients achieving targets collected in the PIONEER 2, 3, and 4 trials (Table 1). Following sampling of the proportion of patients achieving target, the cost of control with each intervention was recorded. This process was repeated 1000 times, with the mean cost of control with each intervention calculated across all 1000 iterations.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Therefore, ethical approval was not required.

Results

Treatment Costs

Across all included PIONEER trials, annual treatment costs with oral semaglutide 14 mg were estimated to be USD 9404, comprised of only the acquisition cost of the medication. Annual treatment costs for empagliflozin 25 mg in PIONEER 2 and sitagliptin 100 mg in PIONEER 3 were estimated to be USD 6000 and USD 5493, respectively, while annual treatment costs with liraglutide 1.8 mg in PIONEER 4 were estimated to be USD 11,367, with needle costs accounting for USD 144 of this total (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Annual treatment cost. USD 2019 United States dollars

Number Needed to Treat

The numbers of patients needed to treat to bring one patient to target was consistently lowest for oral semaglutide 14 mg across all included PIONEER trials. Based on the PIONEER 2 trial, 2.1, 1.5, 2.2, and 1.7 patients needed to be treated with oral semaglutide 14 mg to bring one patient to targets of HbA1c ≤ 6.5%; HbA1c < 7.0%; ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction with weight loss ≥ 3.0%; and HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia and without weight gain, respectively, versus 5.8, 2.5, 3.6, and 2.8 patients needed to be treated to bring one patient to target with empagliflozin 25 mg (Fig. 2). For the two single-, double- and triple-composite endpoints in the PIONEER 3 trial, 2.7, 1.8, 2.6, and 2.1 patients needed to be treated with oral semaglutide 14 mg, respectively, and 7.3, 3.1, 10.4, and 5.0 patients needed to be treated with sitagliptin 100 mg, respectively, to bring one patient to target (Fig. 3). To bring patients to each of the four targets based on the PIONEER 4 trial, 2.1, 1.5, 2.1, and 1.6 patients needed to be treated with oral semaglutide 14 mg, while 2.3, 1.6, 2.9, and 1.9 patients needed to be treated with liraglutide 1.8 mg (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Numbers needed to treat based on PIONEER 2. HbA1c glycated hemoglobin. Analysis based on week 26 data regardless of discontinuation and addition of rescue medication

Fig. 3.

Numbers needed to treat based on PIONEER 3. HbA1c glycated hemoglobin. Analysis based on week 26 data regardless of discontinuation and addition of rescue medication

Fig. 4.

Numbers needed to treat based on PIONEER 4. HbA1c glycated hemoglobin. Analysis based on week 26 data regardless of discontinuation and addition of rescue medication

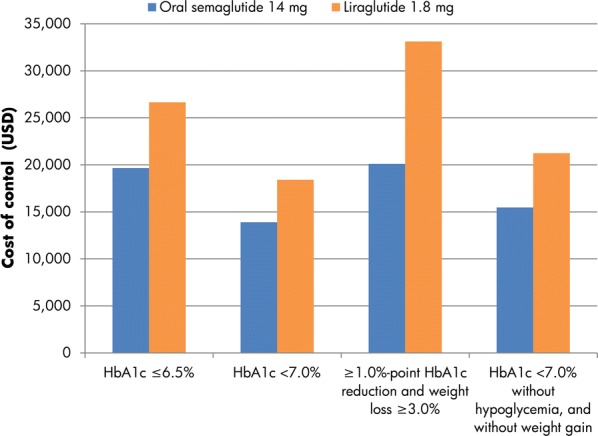

Cost of Control

Annual cost of control was lowest for oral semaglutide 14 mg for all four endpoints versus all comparators (Figs. 5, 6, 7). In PIONEER 2, for the glycemic control targets of HbA1c ≤ 6.5% and HbA1c < 7.0%, oral semaglutide 14 mg was associated with lower cost of control by USD 15,036 and USD 931, respectively, versus empagliflozin 25 mg (Fig. 5). For the composite endpoint of ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction with weight loss ≥ 3.0%, the cost of control was USD 525 lower with oral semaglutide 14 mg than with empagliflozin 25 mg. For the composite endpoint of HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia and without weight gain, oral semaglutide 14 mg was associated with a USD 1255 lower cost of control than empagliflozin 25 mg.

Fig. 5.

Cost of control based on PIONEER 2. HbA1c glycated hemoglobin, USD 2019 United States dollars. Analysis based on week 26 data regardless of discontinuation and addition of rescue medication

Fig. 6.

Cost of control based on PIONEER 3. HbA1c glycated hemoglobin, USD 2019 United States dollars. Analysis based on week 26 data regardless of discontinuation and addition of rescue medication

Fig. 7.

Cost of control based on PIONEER 4. HbA1c glycated hemoglobin, USD 2019 United States dollars. Analysis based on week 26 data regardless of discontinuation and addition of rescue medication

In PIONEER 3, annual costs of control were estimated to be lower with oral semaglutide 14 mg than sitagliptin 100 mg by USD 14,697, USD 346, USD 32,277 and USD 7510 for endpoints of HbA1c ≤ 6.5%, HbA1c < 7.0%, ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction with weight loss ≥ 3.0% and HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia and without weight gain, respectively (Fig. 6).

When the endpoints of HbA1c ≤ 6.5%, HbA1c < 7.0%, ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction with weight loss ≥ 3.0% and HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia and without weight gain were considered for PIONEER 4, costs of control were lower with oral semaglutide 14 mg than liraglutide 1.8 mg by USD 6996, USD 4497, USD 13,011 and USD 5774, respectively (Fig. 7).

Sensitivity Analysis

PSA showed that the results of the base case analysis were robust to sampling around input data. In the analyses for PIONEER 2, 3 and 4, the results remained comparable to the base case analysis, with oral semaglutide 14 mg associated with a lower cost of control than all comparators for all four endpoints (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis results: difference in cost of control for oral semaglutide 14 mg versus the comparator

| Difference in cost of control (USD) | ||

|---|---|---|

| PIONEER 2 (oral semaglutide 14 mg versus empagliflozin 25 mg) | Base case | PSA |

| HbA1c ≤ 6.5% | − 15,036 | − 15,415 |

| HbA1c < 7.0% | − 931 | − 1011 |

| ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction and weight loss ≥ 3.0% | − 525 | − 509 |

| HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia, and no weight gain | − 1255 | − 1315 |

| PIONEER 3 (oral semaglutide 14 mg versus sitagliptin 100 mg) | Base case | PSA |

|---|---|---|

| HbA1c ≤ 6.5% | − 14,697 | − 15,128 |

| HbA1c < 7.0% | − 346 | − 431 |

| ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction and weight loss ≥ 3.0% | − 32,277 | − 33,452 |

| HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia, and no weight gain | − 7510 | − 7607 |

| PIONEER 4 (oral semaglutide 14 mg versus liraglutide 1.8 mg) | Base case | PSA |

|---|---|---|

| HbA1c ≤ 6.5% | − 6996 | − 6930 |

| HbA1c < 7.0% | − 4497 | − 4506 |

| ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction and weight loss ≥ 3.0% | − 13,011 | − 13,130 |

| HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia, and no weight gain | − 5774 | − 5763 |

HbA1c glycated hemoglobin, PSA probabilistic sensitivity analysis, USD 2019 United States dollars

Discussion

The present analysis has demonstrated that the cost of bringing patients to four clinically-relevant endpoints was consistently lower with oral semaglutide 14 mg than with empagliflozin 25 mg, sitagliptin 100 mg and liraglutide 1.8 mg, based on data from PIONEER 2, 3 and 4, respectively. These endpoints are in line with modern treatment of type 2 diabetes, where improvements in additional parameters alongside glycemic control have been demonstrated to be important to both patients’ quality of life and long-term health [2–7].

Key strengths of the present analysis can be found in the simplicity and transparency of the model, which allows inputs being readily updated to match latest unit costs and/or new clinical data. An additional strength is that no projections of long-term outcomes were made from short-term data, avoiding a common limitation of health economic analyses conducted for diabetes interventions. Nonetheless, the present analysis is designed to complement, not replace, these long-term analyses, which are pertinent for fully capturing the long-term complications associated with diabetes, which can be influenced by changes in HbA1c and additional secondary parameters [2, 3, 7]. Previous cost of control analyses published in the US setting for GLP-1 receptor agonists once-weekly semaglutide and liraglutide have demonstrated the value of the cost of control approach, offering pertinent information to healthcare payers focused on short-term budgets [14–17].

The present analysis included differing patient populations, with background diabetes therapies received varying across the PIONEER trial program. PIONEER 2 included patients only receiving metformin, while PIONEER 3 included patients receiving metformin with or without sulfonylurea and PIONEER 4 included patients receiving metformin with or without an SGLT-2 inhibitor. Oral semaglutide is the first GLP-1 receptor agonist administered orally, and therefore may potentially overcome barriers relating to therapeutic inertia. There is significant evidence that people with type 2 diabetes in the US, UK and worldwide do not intensify treatment, despite not achieving glycemic control targets, with concerns around potential side effects of therapies (such as weight gain and hypoglycemia) and fear of injection often cited as reasons for therapeutic inertia [18–22]. The oral formulation of semaglutide allows people with type 2 diabetes to receive the benefits of treatment with a GLP-1 receptor agonist, such as improved glycemic control without weight gain and a low risk of hypoglycemia, without the requirement for daily or weekly injections [9–11]. The present analysis demonstrated that oral semaglutide is efficacious and cost-effective in varying patient populations versus comparators for patients with type 2 diabetes receiving differing background therapies, indicating it is a viable treatment option for a variety of patients, irrespective of prior treatment.

It is important to consider the adverse events associated with new interventions. Gastrointestinal events are the most common category of adverse events with currently available GLP-1 receptor agonists, and this is also the case with oral semaglutide. Safety and tolerability of oral semaglutide were consistent with subcutaneous liraglutide 1.8 mg in the PIONEER 4 study [9]. Data from PIONEER 3 suggest that gastrointestinal adverse events are more common with the highest dose of oral semaglutide than with the lower doses [10].

The present analysis represents the first short-term cost-effectiveness analysis of oral semaglutide in the US, but similar studies have assessed the cost of control of other diabetes medications included in the present analysis. Liraglutide 1.2 mg and 1.8 mg were shown to be associated with a lower cost per patient achieving a target of HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia and without weight gain than sitagliptin in a 2013 study based on a head-to-head randomized controlled trial [23]. The cost of control with liraglutide 1.8 mg and lixisenatide 20 µg was compared for five endpoints [(1) HbA1c ≤ 6.5%; (2) HbA1c < 7.0%; (3) HbA1c < 7.0% and no weight gain; (4) HbA1c < 7.0% with no weight gain and no confirmed hypoglycemia; (5) HbA1c < 7.0% with no weight gain and systolic blood pressure < 140 mmHg], with liraglutide 1.8 mg associated with a lower cost of control for all targets [24]. A cost per response analysis evaluating the SGLT-2 inhibitors took a different approach, calculating the cost per 1% reduction in HbA1c with empagliflozin 10 mg or 25 mg (the SGLT-2 inhibitor included in the present analysis), canagliflozin 100 mg and 300 mg, dapagliflozin 5 mg or 10 mg, and in monotherapy, dual therapy with metformin, and triple therapy with metformin and sulfonylurea [25]. This analysis found that canagliflozin 300 mg was associated with the lowest cost per 1% reduction in HbA1c at all three points in the diabetes treatment pathway, though differences in cost-effectiveness between the SGLT-2 inhibitors were small.

A limitation of the present analysis is the use of endpoints that rely on binary classification (i.e., patients did or did not reach the target). This excludes possibly substantial reductions in HbA1c levels that patients may have experienced if they did not reach the < 7.0% threshold. However, given the greater improvements in HbA1c seen with oral semaglutide throughout the PIONEER trial program, this assumption is likely to be conservative from the oral semaglutide perspective. Moreover, the use of WAC for the included medications does not reflect any rebates that might be applied for specific medical insurance companies. However, these rebates vary from payer to payer, from medication to medication (i.e., varying rebates would be applied to all interventions included in the analysis), and are confidential. Use of WAC therefore represents the best-available approach for the costs of the included interventions.

Conclusion

Oral semaglutide 14 mg represents a cost-effective treatment option versus empagliflozin 25 mg, sitagliptin 100 mg, and liraglutide 1.8 mg for bringing patients with type 2 diabetes to clinically-relevant treatment targets of a single endpoint of HbA1c ≤ 6.5%, a single endpoint of HbA1c <7.0%, a double-composite endpoint of ≥ 1.0%-point HbA1c reduction and weight loss ≥ 3.0%, and a triple-composite endpoint of HbA1c < 7.0% without hypoglycemia and without weight gain in the US.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was supported by funding from Novo Nordisk A/S, Denmark. Novo Nordisk A/S also funded the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Barnaby Hunt is an employee of Ossian Health Economics and Communications, which received consulting fees from Novo Nordisk A/S to support preparation of the analysis. Samuel Malkin is an employee of Ossian Health Economics and Communications, which received consulting fees from Novo Nordisk A/S to support preparation of the analysis. William Valentine is an employee of Ossian Health Economics and Communications, which received consulting fees from Novo Nordisk A/S to support preparation of the analysis. Brian Bekker Hansen is an employee of Novo Nordisk A/S. Klaus Kallenbach is an employee of Novo Nordisk A/S. Åsa Ericsson is an employee of Novo Nordisk Scandinavia AB. Sarah Ali is an employee of Novo Nordisk Inc. Tam Dang-Tan is an employee of Novo Nordisk Inc. and a shareholder in Novo Nordisk. Brian Bekker Hansen is a shareholder in Novo Nordisk. Åsa Ericsson is a shareholder in Novo Nordisk.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Therefore, ethical approval was not required.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.9929951.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2017. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(5):917–928. doi: 10.2337/dci18-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) Lancet. 1998;352:837–853. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34) Lancet. 1998;352:854–865. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Diabetes Association 6. Glycemic targets: standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S61–S70. doi: 10.2337/dc19-S006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Diabetes Association 8. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S81–S89. doi: 10.2337/dc19-S008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Diabetes Association 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S90–S102. doi: 10.2337/dc19-S009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, Kernan WN, Mathieu C, Mingrone G, Rossing P, Tsapas A, Wexler DJ, Buse JB. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Diabetes Care. 2018;41(12):2669–2701. doi: 10.2337/dci18-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buckley ST, Bækdal TA, Vegge A, Maarbjerg SJ, Pyke C, Ahnfelt-Rønne J, Madsen KG, Schéele SG, Alanentalo T, Kirk RK, Pedersen BL, Skyggebjerg RB, Benie AJ, Strauss HM, Wahlund PO, Bjerregaard S, Farkas E, Fekete C, Søndergaard FL, Borregaard J, Hartoft-Nielsen ML, Knudsen LB. Transcellular stomach absorption of a derivatized glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(467):eaar7047. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aar7047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodbard HW, Rosenstock J, Canani LH, Deerochanawong C, Gumprecht J, Lindberg SØ, Lingvay I, Søndergaard AL, Treppendahl MB, Montanya E, For the PIONEER 2 investigators Oral semaglutide versus empagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled on metformin: the PIONEER 2 trial. Diabetes Care. 2019 doi: 10.2337/dc19-0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenstock J, Allison D, Birkenfeld AL, Blicher TM, Deenadayalan S, Jacobsen JB, Serusclat P, Violante R, Watada H, Davies M, PIONEER 3 Investigators Effect of additional oral semaglutide vs sitagliptin on glycated hemoglobin in adults with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled with metformin alone or with sulfonylurea: the PIONEER 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;321(15):1466–1480. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.2942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenstock J, Allison D, Birkenfeld A, Blicher T, Deenadayalan S, Jacobsen J, Serusclat P, Violante R, Watada H, Davies M. SAT-139 clinical impact of oral semaglutide compared with sitagliptin in T2D on metformin ± sulfonylurea: the Pioneer 3 trial. J Endocr Soc. 2019;3(Suppl 1):SAT–139. doi: 10.1210/js.2019-SAT-139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pratley R, Amod A, Hoff ST, Kadowaki T, Lingvay I, Nauck M, Pedersen KB, Saugstrup T, Meier JJ, PIONEER 4 investigators Oral semaglutide versus subcutaneous liraglutide and placebo in type 2 diabetes (PIONEER 4): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3a trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10192):39–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.IBM Micromedex. RED BOOK. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/home/dispatch. 2019. Accessed 27 September 2019.

- 14.Wilkinson L, Hunt B, Johansen P, Iyer NN, Dang-Tan T, Pollock RF. Cost of achieving HbA1c treatment targets and weight loss responses with once-weekly semaglutide versus dulaglutide in the United States. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9(3):951–961. doi: 10.1007/s13300-018-0402-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansen P, Hunt B, Iyer NN, Dang-Tan T, Pollock RF. A relative cost of control analysis of once-weekly semaglutide versus exenatide extended-release and dulaglutide for bringing patients to HbA1c and weight loss treatment targets in the USA. Adv Ther. 2019;36(5):1190–1199. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-00915-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunt B, McConnachie CC, Gamble C, Dang-Tan T. Evaluating the short-term cost-effectiveness of liraglutide versus lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes in the United States. J Med Econ. 2017;20(11):1117–1120. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2017.1347793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langer J, Hunt B, Valentine WJ. Evaluating the short-term cost-effectiveness of liraglutide versus sitagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes failing metformin monotherapy in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2013;19(3):237–246. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.3.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pantalone KM, Misra-Hebert AD, Hobbs TM, Ji X, Kong SX, Milinovich A, Weng W, Bauman J, Ganguly R, Burguera B, Kattan MW, Zimmerman RS. Clinical inertia in type 2 diabetes management: evidence from a large. Real-world data set. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(7):e113–e114. doi: 10.2337/dc18-0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu AZ, Sheehan JJ. Treatment intensification for patients with type 2 diabetes and poor glycaemic control. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(9):892–898. doi: 10.1111/dom.12683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khunti K, Millar-Jones D. Clinical inertia to insulin initiation and intensification in the UK: a focused literature review. Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khunti K, Gomes MB, Pocock S, Shestakova MV, Pintat S, Fenici P, Hammar N, Medina J. Therapeutic inertia in the treatment of hyperglycaemia in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(2):427–437. doi: 10.1111/dom.13088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khunti K, Nikolajsen A, Thorsted BL, Andersen M, Davies MJ, Paul SK. Clinical inertia with regard to intensifying therapy in people with type 2 diabetes treated with basal insulin. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(4):401–409. doi: 10.1111/dom.12626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langer J, Hunt B, Valentine WJ. Evaluating the short-term cost-effectiveness of liraglutide versus sitagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes failing metformin monotherapy in the United States. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(3):237–246. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.3.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunt B, McConnachie CC, Gamble C, Dang-Tan T. Evaluating the short-term cost-effectiveness of liraglutide versus lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes in the United States. J Med Econ. 2017;20(11):1117–1120. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2017.1347793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez JM, Macomson B, Ektare V, Patel D, Botteman M. Evaluating drug cost per response with SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(6):309–318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.