Abstract

Introduction

Gender disparities in access to healthcare have been documented, including disparities in access to care for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Disparities in access to cardiologists could disadvantage some patients to the newer lipid-lowering proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor (PCSK9i) antibodies, as utilization management criteria for PCSK9is often require step therapy with statins and/or ezetimibe and prescription by a cardiologist. To assess whether these utilization management criteria disproportionally limit access to patients with certain characteristics, we assessed the use of cardiologist care and receipt of statin and/or ezetimibe prescriptions from a cardiologist by gender and other patient demographic and clinical characteristics.

Methods

This cross-sectional study used administrative claims data from Inovalon’s Medical Outcomes Research for Effectiveness and Economics Registry (MORE2 Registry®) for patients enrolled in commercial and Medicare Advantage healthcare plans from January 1, 2014, through December 31, 2014. Provider data from the registry were linked to individual demographic and administrative claims data. Logistic regression models were used to assess characteristics associated with outpatient visits to a cardiologist and receipt of a prescription for statin and/or ezetimibe from a cardiologist.

Results

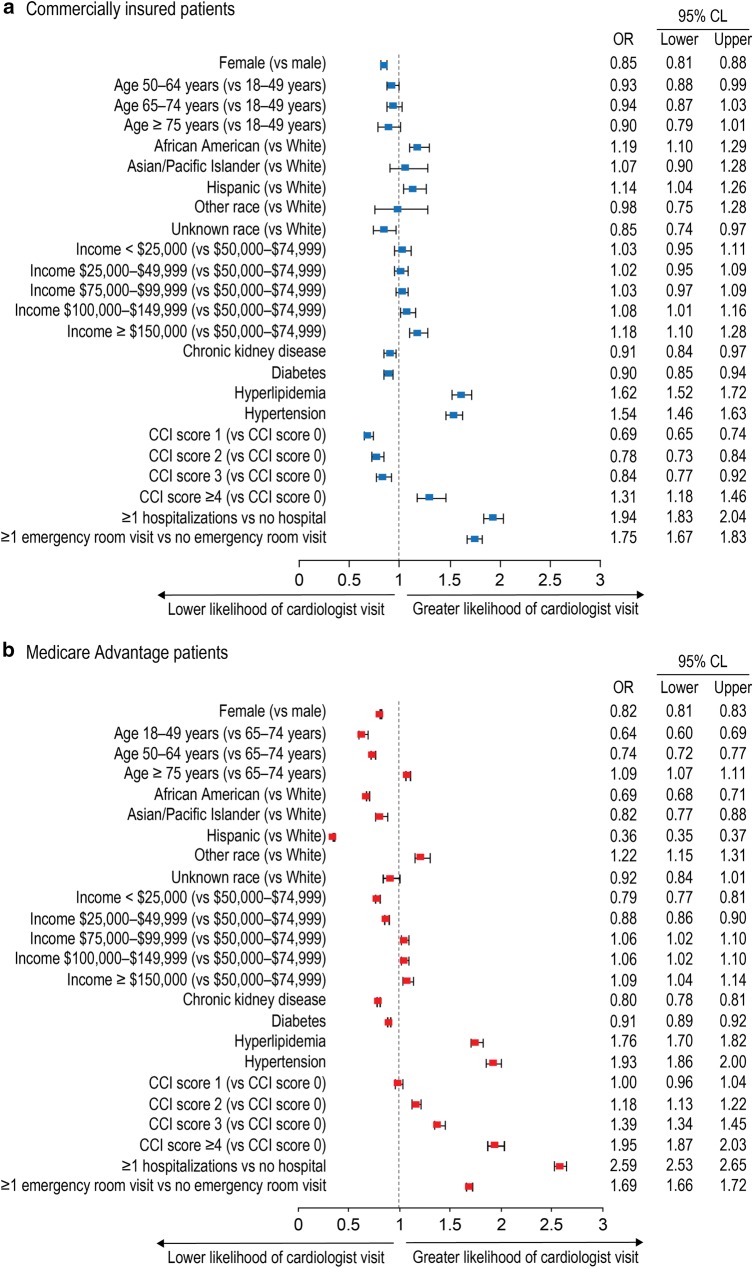

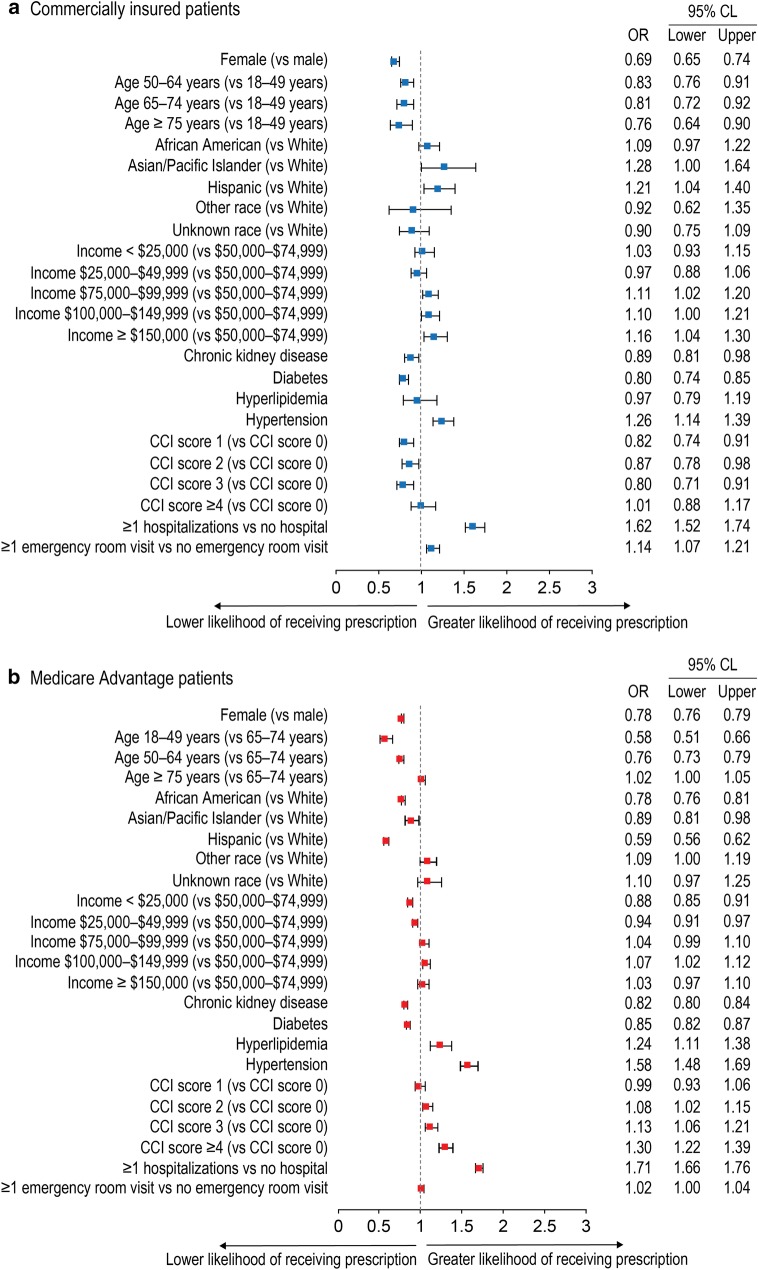

Data from 39,322 patients in commercial plans and 261,898 patients with Medicare Advantage were analyzed. Female gender (vs male) was associated with a significantly lower likelihood of visiting a cardiologist for patients in commercial plans (odds ratio [OR] 0.85; 95% confidence limit [CL] 0.81–0.88) and in Medicare Advantage plans (OR 0.82; 95% CL 0.81–0.83). Female gender was also associated with a lower likelihood of receiving a statin and/or ezetimibe prescription from a cardiologist for patients in commercial plans (OR 0.69; 95% CL 0.65–0.74) and in Medicare Advantage plans (OR 0.78; 95% CL 0.76–0.79).

Conclusions

Compared with men, women were less likely to visit a cardiologist and less likely to receive a prescription for a statin and/or ezetimibe from a cardiologist.

Funding

Amgen Inc.

Keywords: Cardiology, Claims analysis, Equity, Ezetimibe, Gender, Healthcare utilization, PCSK9 inhibitor, Statin

Introduction

Atherosclerosis, a chronic inflammatory disease that leads to plaque deposition in arteries and is associated with increased levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) [1], is the leading cause of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) [2]. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is a common cause of myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke and can lead to a need for revascularization procedures such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass graft (CABG). Annually, 805,000 first or recurrent MIs and 795,000 first or recurrent strokes occur in the USA [3]. In 2014, 480,000 patients required a PCI and 371,000 patients required a CABG procedure [3].

Lipids, especially LDL-C, are implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and contribute to the development of atherosclerotic lesions [1]. Current treatment guidelines recommend the use of statins as first-line lipid-lowering therapy (LLT) in patients with clinical ASCVD (i.e., diagnoses of acute coronary syndromes, history of MI, stable or unstable angina, coronary or other arterial revascularization, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or peripheral arterial disease presumed to be of atherosclerotic origin) [4]. For patients who do not achieve lipid goals on a tolerable dose of statin monotherapy, combination therapy with a statin and a nonstatin LLT is recommended [4]. Nonstatin LLTs include ezetimibe and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor (PCSK9is) antibodies [4–6]. US guidelines currently recommend the use of PCSK9is for very high-risk patients and LDL-C greater than 70 mg/dL despite treatment with standard background therapy including statins and ezetimibe [4–6].

In clinical trials, PCSK9is demonstrated clinically significant and unprecedented reductions (60–70%) in LDL-C in patients whose LDL-C could not be controlled with a statin and/or ezetimibe [7]. Notably, reductions in LDL-C were independent of gender across phase 3 clinical trials of PCSK9is [8, 9]. Additionally, PCSK9is have been shown to reduce the rate of cardiovascular events by 15% to 20% compared with placebo in patients with ASCVD and other risk factors [10, 11].

Despite the demonstrated clinical benefit of PCSK9is for some patients, access to these medications has been difficult. Barriers to obtaining PCSK9i prescriptions include a requirement for prior authorization, step therapy (i.e., the trial of another medication first), and high prior authorization rejection rates that are not clinically based [12]. One PCSK9i prior authorization requirement implemented in some health plans requires the prescription to be written by a specialist or cardiologist, which may pose a significant barrier for patients with limited access to cardiologists. The primary objective of this study was to describe the distribution of demographic and clinical characteristics of PCSK9i-eligible patients with clinical ASCVD receiving cardiologist care in the outpatient setting in commercial and Medicare Advantage plans. This high-risk population was of particular interest because disparities in care could lead to an increase in major cardiovascular events. We also examined the characteristics of patients who received a statin and/or ezetimibe prescription from a cardiologist. The results of this study can be used to inform whether requiring a prescription for a PCSK9i from a cardiologist disproportionally limits access to patients with certain characteristics.

Methods

Data Sources

This cross-sectional study was based on administrative claims data from Inovalon’s Medical Outcomes Research for Effectiveness and Economics Registry (MORE2 Registry®). The MORE2 Registry is a warehouse of healthcare data representing 132 million members in the USA and includes information about enrollment and demographic characteristics, medical encounters (office visits, outpatient services, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, postacute care services), laboratory results, and retail and mail order pharmacy records. The registry includes commercial, Affordable Care Act Marketplace, Medicare Advantage, and managed Medicaid health plans. The MORE2 Registry was linked to an external database that provides individual-level data on race/ethnicity, education level, marital status, and household income.

Patients

The study population included patients at least 18 years of age who were continuously enrolled in commercial or Medicare Advantage health plans during the study period (January 1, 2014, through December 31, 2014) and had evidence of ASCVD recorded on medical claims based on diagnosis or procedure codes (Table 1). Eligible patients had to have filled at least one prescription for statin, ezetimibe, or statin plus ezetimibe combination therapy and have an LDL-C level of at least 70 mg/dL. Statins included atorvastatin, atorvastatin/amlodipine, cerivastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pitavastatin, pravastatin, pravastatin/aspirin, rosuvastatin, simvastatin, and simvastatin/sitagliptin.

Table 1.

Diagnosis and procedure codes for identification of ASCVD conditions

| ASCVD condition | Code(s) |

|---|---|

| Acute coronary syndromes |

Acute myocardial infarction: ICD-9-CM: 410.xx Unstable angina: ICD-9-CM: 411.xx |

| History of myocardial infarction |

ICD-9-CM: 412.xx MS-DRG: 280–282 |

| Stable angina | ICD-9-CM: 413.xx |

| Coronary artery revascularization |

CPT: 33140, 33141, 33508, 33510–33519, 33521–33523, 33530, 33533–33536, 33572, 35500, 35572, 35600, 92920, 92921, 92924, 92925, 92928, 92929, 92933, 92934, 92937, 92938, 92941, 92943, 92944, 92973, 92975, 92977, 92980–92984, 92995–92996, 00566, 00567 HCPCS: C9600–C9608, G0290, G0291, S2205–S2209 ICD-9-CM: 36.03, 36.04, 36.06, 36.07, 36.09, 36.11–36.17, 36.19, 36.2, 36.31–36.34, 36.39, 00.45–00.48, 00.66, 17.55, 36.10 MS-DRG: 231–236, 246–251 |

| Peripheral artery revascularization |

CPT: 34051, 34101, 34111, 34201, 34203, 35302–35306, 35311, 35321, 35331, 35341, 35351, 35344, 35361, 35363, 35371, 35372, 35450, 35452, 35454, 35456, 35458, 35459, 35470–35475, 35480–35485, 35490–35495, 35511–35512, 35516, 35518, 35521–35523, 35525, 35526, 35531, 35533, 35535–35540, 35548, 35549, 35551, 35556, 35558, 35560, 35563, 35565, 35566, 35570–35571, 35583, 35585, 35587, 35612, 35616, 35621, 35623, 35626, 35631–35634, 35636–35638, 35646, 35647, 35650, 35651, 35654, 35656, 35661, 35663, 35665, 35666, 35671, 35875, 35876, 35879, 35881, 35883, 35884, 37184–37186, 37201, 37202, 37205–37208, 75960, 75962–75964, 75966, 75968, 93668 ICD-9-CM: 38.13–38.16, 38.18, 39.71, 39.73, 00.55, 00.60, 38.10, 39.50, 39.90 |

| Peripheral artery disease | ICD-9-CM: 250.70–250.73, 362.30, 362.31–362.33, 433.00, 433.10, 433.20, 433.30, 433.80, 433.90, 434.00, 434.10, 434.90, 440.0x, 440.1x, 440.20–440.24, 440.29, 440.30–440.32, 440.4x, 440.8x, 440.9x, 443.9x, 444.01, 444.09, 444.1x, 444.21, 444.22, 444.81, 444.89, 444.9x, 445.01, 445.02, 445.081, 445.89 |

| Ischemic stroke |

MS-DRG: 061–063 HCPCS: G8600–G8602 ICD-9-CM: 433.01, 433.11, 433.21, 433.31, 433.81, 433.91, 434.01, 434.11, 434.91 |

| Transient ischemic attack |

MC-DRG: 069 ICD-9-CM: 362.34, 435.xx, 435.1x, 435.2x, 435.3x, 435.8x, 435.9x |

| Stroke/transient ischemic attack |

HCPCS: G8837 ICD-9-CM: V12.54 |

ASCVD atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, CPT current procedural terminology, HCPCS Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System, ICD-9-CM International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, MS-DRG Medicare Severity-Diagnosis Related Group

Study Outcomes

Outcomes included (1) whether the patient had at least one outpatient cardiologist visit during the study period, and (2) whether the patient filled at least one prescription for statin, ezetimibe, or statin plus ezetimibe combination therapy written by a cardiologist during the study period.

Statistical Considerations

The distribution of patient characteristics based on study outcomes was evaluated. Logistic regression models were used to identify patient characteristics associated with an outpatient visit to a cardiologist and with receipt of a statin and/or ezetimibe prescription from a cardiologist. Logistic regression models controlled for age, gender, race or ethnicity, household income, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, comorbidities (hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and diabetes), and patient baseline healthcare resource utilization. The analysis was separately stratified by payer type (commercial or Medicare Advantage).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This analysis of deidentified claims data conformed to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Ethics committee approval was not required, as this was a retrospective analysis and no human participants were involved in the study.

Results

Patients

A total of 39,322 patients with commercial insurance and 261,898 patients with Medicare Advantage met eligibility criteria and were included in the study. The mean age was 57.4 years for commercially insured patients and 72.4 years for patients with Medicare Advantage (Table 2). Most patients had hypertension (80.5% and 94.0% of commercially insured patients and patients with Medicare Advantage, respectively) and hyperlipidemia (85.8% and 93.2%). Mean Charlson Comorbidity Index score was higher for patients with Medicare Advantage (score 2.7) compared with commercially insured patients (score 1.7).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

| Commercial (N = 39,322) | Medicare Advantage (N = 261,898) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean, years | 57.4 | 72.4 |

| Gender, n female (%) | 16,194 (41.2) | 135,157 (51.6) |

| Race or ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 32,731 (83.2) | 187,466 (71.6) |

| African American | 3050 (7.8) | 45,141 (17.2) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 546 (1.4) | 3734 (1.4) |

| Hispanic (ethnicity) | 1800 (4.6) | 19,155 (7.3) |

| Other race | 236 (0.6) | 4402 (1.7) |

| Missing | 959 (2.4) | 2000 (0.8) |

| Household income, US$, n (%) | ||

| < 25,000 | 3998 (10.2) | 75,512 (27.7) |

| 25,000–49,999 | 6201 (15.8) | 89,093 (34.0) |

| 50,000–74,999 | 10,633 (27.0) | 55,930 (21.4) |

| 75,000–99,999 | 8670 (22.0) | 17,516 (6.7) |

| 100,000–149,000 | 5909 (15.0) | 16,829 (6.4) |

| ≥ 150,000 | 3911 (9.9) | 10,018 (3.8) |

| Select comorbidities, % | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 11.9 | 31.4 |

| Diabetes | 36.8 | 56.6 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 85.8 | 93.2 |

| Hypertension | 80.5 | 94.0 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean score | 1.7 | 2.7 |

| Hospitalizations during study period, mean number | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Emergency department visits during study period, mean number | 0.6 | 0.8 |

Patients with a Cardiologist Visit

The percentages of commercially insured and Medicare Advantage patients with a visit to a cardiologist during the study period were 56.9% and 61.7%, respectively (Table 3). Patient characteristics associated with a decreased likelihood of a cardiologist visit for both commercially insured patients and those with Medicare Advantage included female gender, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes. Patient characteristics associated with an increased likelihood of a cardiologist visit for both cohorts included household income of at least US$100,000, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, recent hospitalization, and recent emergency room visit (Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Outpatient physician visits

| Commercial (N = 39,322) | Medicare Advantage (N = 261,898) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiologists | ||

| Patients with a visit, % | 56.9 | 61.7 |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 4.2 (4.9) | 5.1 (5.8) |

| Primary care physicians | ||

| Patients with a visit, % | 82.9 | 87.5 |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 7.7 (9.6) | 12.7 (12.5) |

| Other physicians | ||

| Patients with a visit, % | 84.6 | 88.9 |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 9.8 (12.8) | 14.1 (14.3) |

SD standard deviation

Fig. 1.

Likelihood of an outpatient cardiologist visit. CCI Charlson Comorbidity Index, CL confidence limit, OR odds ratio

Patients with a Statin and/or Ezetimibe Prescription from a Cardiologist

The percentages of commercially insured and Medicare Advantage patients with a prescription for statin and/or ezetimibe were 58.2% and 67.6%, respectively; however, only 27.3% and 22.5% of patients received a statin and/or ezetimibe prescription from a cardiologist (Table 4). Patient characteristics associated with a decreased likelihood of a prescription from a cardiologist for both commercially insured patients and those with Medicare Advantage included female gender, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes. Patient characteristics associated with an increased likelihood of a prescription from a cardiologist for both commercially insured patients and those with Medicare Advantage included hypertension, recent hospitalization, and recent emergency room visit (Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Statin and/or ezetimibe prescriptions

| Commercial (N = 39,322) | Medicare Advantage (N = 261,898) | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with ≥ 1 statin and/or ezetimibe prescription, % | 58.2 | 67.6 |

| Prescriber: cardiologist | ||

| Patients with ≥ 1 prescription, % | 27.3 | 22.5 |

| Number of prescriptions, mean (SD) | 0.6 (1.5) | 0.3 (0.8) |

| Prescriber: primary care physician | ||

| Patients with ≥ 1 prescription, % | 51.5 | 57.1 |

| Number of prescriptions, mean (SD) | 1.2 (2.1) | 1.2 (1.8) |

| Prescriber: other physician | ||

| Patients with ≥ 1 prescription, % | 39.8 | 47.0 |

| Number of prescriptions, mean (SD) | 0.8 (1.4) | 1.0 (1.7) |

| Prescriber: unknown physician type | ||

| Patients with ≥ 1 prescription, % | 38.5 | 32.9 |

| Number of prescriptions, mean (SD) | 0.9 (1.6) | 0.8 (1.6) |

SD standard deviation

Fig. 2.

Likelihood of receiving a prescription for statin and/or ezetimibe from a cardiologist. CCI Charlson Comorbidity Index, CL confidence limit, OR odds ratio

Discussion

In this analysis of patients with ASCVD and risk factors such as LDL-C levels of at least 70 mg/dL, women were significantly less likely than men to have an outpatient visit to a cardiologist. Women were also significantly less likely than men to receive a prescription for a statin and/or ezetimibe from a cardiologist. These observations were made in both commercially insured patients and in patients in Medicare Advantage plans. Likewise in a study of PCSK9i access and cardiovascular outcomes published in 2019, Myers et al. reported that PCSK9i rejection rates were higher in women versus men and that access disparities were associated with higher rates of cardiovascular events [13].

Women experience many aspects of CVD differently than men—most notably, different symptom patterns for MI (less chest pain, more shortness of breath, nausea/vomiting, and back or jaw pain) [14]. Although men and women share similar risk factors for CVD, women are disproportionally affected by some of these common risk factors [15]. For example, elevated levels of LDL-C are a known risk factor for CVD in both genders, and LDL-C levels in postmenopausal women can exceed levels seen in men. Elevation of triglyceride levels increase cardiovascular risk more in women than in men. Notably, statin therapy is as effective at lowering lipid levels in women as in men [16]. Women also have gender-specific risk factors for CVD, including pregnancy-related risks (hypertension, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes), oral contraceptive use, and menopause [17]. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the number of men and women with CVD, as measured by the 2013–2016 US prevalence of CVD excluding hypertension, is nearly the same (9.6% vs 8.4%, respectively). Likewise, 2016 cardiovascular mortality estimates show that a similar number of men and women die each year from CVD [3]. The similarity in CVD and mortality rates between men and women underscores the need for parity in access to and utilization of evidence-based, risk-reducing treatment.

Despite the burden of CVD in women, women with CVD experience increased hurdles in accessing healthcare compared with men. For example, a gender bias in referral of women for secondary prevention measures, including cardiac rehabilitation and medications to control hypercholesterolemia, has been observed [18, 19]. Other studies have shown that women with CVD are less likely to undergo and more likely to experience a delay in coronary angiography during hospitalization [20, 21]. An analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that effective cardiac medications (beta-blockers, angiotensin II converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers) used to reduce the risk of death and recurrent coronary events in patients with coronary artery disease are underused in women [22]. Low income or socioeconomic status, more prevalent in women, is a significant predictor of cardiovascular death or MI [23]. The 2015 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report (based on priority areas defined by the National Quality Strategy established by the Affordable Care Act) noted a disparity in access to healthcare for women in general that requires immediate attention [24].

Reduction of LDL-C levels to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events is the goal of treatment in patients with ASCVD [4]. Statins have been shown to effectively reduce levels of LDL-C. Despite the demonstrated efficacy of these medications, studies have shown that women are less likely to receive statin therapies than men [22, 25]. PCSK9is can be used in patients who need further LDL-C reduction in order to decrease their risk for MI, stroke, and coronary revascularizations [4]. A study by the American Society for Preventive Cardiology (ASPC) reported significant barriers to patients attempting to fill prescriptions for PCSK9is, including requirements for prior authorization, step therapy, and appeals [12]. The present analysis extends this finding, suggesting that utilization management criteria that require patients try ezetimibe before a PCSK9i (i.e., step therapy) and require prescriptions for PCSK9i be written by a cardiologist could further obstruct women from accessing these therapies at the same rate as men, reinforcing the gender gap in cardiovascular care.

This study was subject to limitations associated with claims-based analyses, including errors due to miscoding. In addition, we were not able to identity the reason why a cardiologist may have decided not to prescribe LLT for a given patient. For example, some patients may have been receiving a stable and well-tolerated LLT regimen prescribed by another physician, or a patient may have been intolerant to statins or had a contraindication; therefore, we did not analyze prescription patterns between patients who did versus did not see a cardiologist. Given the observational and cross-sectional design of the study, confounding factors other than those accounted for in the multivariate analysis could have affected the results. Moreover, the percentage of patients under the care of a cardiologist may be underestimated if patients did not have a visit during the data collection period but had seen a cardiologist previously. Results may not be representative of patients who are uninsured or underinsured or who have different demographic or clinical characteristics.

Conclusion

In summary, results demonstrated that women with ASCVD were less likely than men to visit a cardiologist and to receive a prescription for a statin and/or ezetimibe from a cardiologist. Utilization management criteria that require prescriptions be written by a cardiologist may disproportionally limit women with ASCVD access to needed LLTs.

Acknowledgements

Amgen employees were involved in study design, interpretation of data, writing of the report, and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Funding

Sponsorship for this study, editorial assistance, and the Rapid Service Fees were funded by Amgen Inc. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Michael Johnsrud (Avalere), David Harrison (Amgen), and Juan Maya (formerly of Amgen) provided insight on prior iterations of reporting this study. Tim Peoples (Amgen), Cathryn M. Carter (Amgen), and Julia R. Gage (on behalf of Amgen) provided medical writing support.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Prior Presentation

A subset of these data was presented at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2017 during November 11–15, 2017, in Anaheim, CA.

Disclosures

Xian Shen is an employee of Avalere Health LLC, which received consultant fees from Amgen Inc. Stefan DiMario is an employee and shareholder of Amgen Inc. Kiran Philip is an employee and shareholder of Amgen Inc.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This analysis of deidentified claims data conformed to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Ethics committee approval was not required, as this was a retrospective analysis and no human participants were involved in the study.

Data Availability

Qualified researchers may request data from Amgen clinical studies. Complete details are available at http://www.amgen.com/datasharing.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.9224312.

References

- 1.Wu MY, Li CJ, Hou MF, Chu PY. New insights into the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2034. doi: 10.3390/ijms18102034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barquera S, Pedroza-Tobias A, Medina C, et al. Global overview of the epidemiology of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Arch Med Res. 2015;46:328–338. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56–e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amgen Inc. REPATHA® (evolocumab) prescribing information. Updated February 2019. https://pi.amgen.com/~/media/amgen/repositorysites/pi-amgen-com/repatha/repatha_pi_hcp_english.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr 2018.

- 6.sanofi-aventis US LLC. PRALUENT® (alirocumab) prescribing information. Updated April 2019. http://products.sanofi.us/praluent/praluent.pdf. Accessed 6 May 2019.

- 7.Gouni-Berthold I, Descamps OS, Fraass U, et al. Systematic review of published phase 3 data on anti-PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies in patients with hypercholesterolaemia. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82:1412–1443. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stroes E, Robinson JG, Raal FJ, et al. Consistent LDL-C response with evolocumab among patient subgroups in PROFICIO: a pooled analysis of 3146 patients from phase 3 studies. Clin Cardiol. 2018;41:1328–1335. doi: 10.1002/clc.23049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vallejo-Vaz AJ, Ginsberg HN, Davidson MH, et al. Lower on-treatment low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and major adverse cardiovascular events in women and men: pooled analysis of 10 ODYSSEY phase 3 alirocumab trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009221. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al. Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2097–2107. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baum SJ, Toth PP, Underberg JA, Jellinger P, Ross J, Wilemon K. PCSK9 inhibitor access barriers-issues and recommendations: improving the access process for patients, clinicians and payers. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:243–254. doi: 10.1002/clc.22713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myers KD, Farboodi N, Mwamburi M, et al. Effect of access to prescribed PCSK9 inhibitors on cardiovascular outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12:e005404. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Heart Association. Heart attack symptoms in women. Updated July 31, 2015. 2015. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/heart-attack/warning-signs-of-a-heart-attack/heart-attack-symptoms-in-women. Accessed April 12, 2019.

- 15.Roeters van Lennep JE, Westerveld HT, Erkelens DW, van der Wall EE. Risk factors for coronary heart disease: implications of gender. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:538–549. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00388-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cholesterol Treatment Trialistss' (CTT) Collaboration. Fulcher J, O’Connell R, et al. Efficacy and safety of LDL-lowering therapy among men and women: meta-analysis of individual data from 174,000 participants in 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;385:1397–1405. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61368-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SK, Khambhati J, Varghese T, et al. Comprehensive primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:832–838. doi: 10.1002/clc.22767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aragam KG, Moscucci M, Smith DE, et al. Trends and disparities in referral to cardiac rehabilitation after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2011;161(544–551):e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colella TJ, Gravely S, Marzolini S, et al. Sex bias in referral of women to outpatient cardiac rehabilitation? A meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22:423–441. doi: 10.1177/2047487314520783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabbag A, Matetzky S, Porter A, et al. Sex differences in the management and 5-year outcome of young patients (< 55 years) with acute coronary syndromes. Am J Med. 2017;130:1324.e15–1324.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alnsasra H, Zahger D, Geva D, et al. Contemporary determinants of delayed benchmark timelines in acute myocardial infarction in men and women. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:1715–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.07.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tran HV, Waring ME, McManus DD, et al. Underuse of effective cardiac medications among women, middle-aged adults, and racial/ethnic minorities with coronary artery disease (from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005 to 2014) Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:1223–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaw LJ, Merz CN, Bittner V, et al. Importance of socioeconomic status as a predictor of cardiovascular outcome and costs of care in women with suspected myocardial ischemia. Results from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute-sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:1081–1092. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore JE, Mompe A, Moy E. Disparities by sex tracked in the 2015 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report: trends across National Quality strategy priorities, health conditions, and access measures. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ladapo JA, Coles A, Dolor RJ, et al. Quantifying sociodemographic and income disparities in medical therapy and lifestyle among symptomatic patients with suspected coronary artery disease: a cross-sectional study in North America. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e016364. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Qualified researchers may request data from Amgen clinical studies. Complete details are available at http://www.amgen.com/datasharing.