Abstract

This study systematically examined state‐level laws protecting breastfeeding, including their current status and historical development, as well as identified gaps across US states and regions. The National Conference of State Legislatures summarised breastfeeding laws for 50 states and DC as of September 2010, which we updated through May 2011. We then searched LexisNexis and Westlaw to find the full text of laws, recording enactment dates and definitions. Laws were coded into five categories: (1) employers are encouraged or required to provide break time and private space for breastfeeding employees; (2) employers are prohibited from discriminating against breastfeeding employees; (3) breastfeeding is permitted in any public or private location; (4) breastfeeding is exempt from public indecency laws; and (5) breastfeeding women are exempt from jury duty. By May 2011, 1 state had enacted zero breastfeeding laws, 10 had one, 22 had two, 12 had three, 5 had four and 1 state had laws across all five categories. While 92% of states allowed mothers to breastfeed in any location and 57% exempted breastfeeding from indecency laws, 37% of states encouraged or required employers to provide break time and accommodations, 24% offered breastfeeding women exemption from jury duty and 16% prohibited employment discrimination. The Northeast had the highest proportion of states with breastfeeding laws and the Midwest had the lowest. Breastfeeding outside the home is protected to varying degrees depending on where women live; this suggests that many women are not covered by comprehensive laws that promote breastfeeding.

Keywords: breastfeeding, public policy, state government

Breastfeeding confers a range of benefits to children, mothers and society (Gartner et al. 2005; Ip et al. 2007; Bartick & Reinhold 2010; USDHHS 2011). The Agency for Health Care Research and Quality 2007 report concluded that children who are breastfed are at reduced risk for ear infections, gastroenteritis, asthma and obesity, while mothers who breastfeed are at lower risk for type 2 diabetes, and breast and ovarian cancers (Ip et al. 2007). Despite the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation that mothers should exclusively breastfeed for the first 6 months and continue breastfeeding for at least 1 year (Gartner et al. 2005), 75% of US mothers initiate breastfeeding and 43% of infants receive any breast milk at 6 months (CDC 2010a). Bartick & Reinhold (2010) estimated that $10.5 billion would be saved annually and 741 deaths averted if 80% of US mothers exclusively breastfeed for 6 months.

The US Surgeon General's Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding (2011) identified several barriers to breastfeeding. Among these, returning to work and embarrassment about breastfeeding, particularly in public places, remain significant challenges. In 2010, half of all mothers worked outside the home during their infant's first year, and among those employed, 71% worked full‐time (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2010). Research has found that women who return to work soon after birth or return full‐time are less likely to start breastfeeding than women who are not employed (Hawkins et al. 2007a; Guendelman et al. 2009; Mandal et al. 2010). Mothers who work full‐time also have a shorter duration of breastfeeding than non‐employed mothers (Hawkins et al. 2007b; Guendelman et al. 2009; Mandal et al. 2010). A survey in 2010 found that only 28% of companies reported having an on‐site lactation room and 5% offered lactation support services (Society for Human Resource Management 2011). Even for women who wish to continue breastfeeding after returning to work, they may be faced with inflexible work hours, insufficient break times and lack of private and clean facilities to express and store breast milk (USDHHS 2011).

In the 2010 HealthStyles Survey, an annual national survey of adults in the US, 32% believed that it is embarrassing for a mother to breastfeed in front of others (CDC 2010b). While only 59% of adults in 2010 reported that women should have the right to breastfeed in public places (CDC 2010b), this is much higher than the 43% of adults who agreed with this statement in 2001 (Li et al. 2004). If a woman breastfeeds in a public space or place and there is no legislation protecting her right to do so, then she may be asked to stop or leave. For the US to achieve the Healthy People 2020 objectives for breastfeeding (USDHHS 2010), mothers need support to breastfeed outside the home whether at work or in public.

Legislation can help address these barriers to breastfeeding. In March 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) became the first federal legislation in the United States to support breastfeeding (Public Law no. 111‐148). The legislation requires employers to provide break time and private space to express milk for 1 year after their child's birth. While the enactment of the ACA represents progress in promoting breastfeeding, most breastfeeding laws are enacted at the state level. Some laws support breastfeeding in the workplace, such as by offering break time and accommodations for breastfeeding employees and prohibiting employer discrimination based on breastfeeding. Murtagh & Moulton (2011) found that by 2009, 23 states and DC had enacted laws to encourage breastfeeding at work. The authors noted that coverage and requirements varied across states and most of the laws did not have enforcement provisions.

There are additional laws aimed to promote breastfeeding that affect all women and not only those who are employed. Legislation may encourage breastfeeding by creating a supportive environment for women to breastfeed outside the home, such as by permitting women to breastfeed in any location and exempting breastfeeding from public indecency laws. Kogan et al. (2008) found that US states with multiple pieces of breastfeeding legislation by 2003 had a higher proportion of mothers who initiated breastfeeding and continued through 6 months postpartum. However, their summary measure of the legislation did not differen‐tiate laws and there is still little known about the scope and strength of current breastfeeding laws.

By taking a more comprehensive approach, we identified all state‐level breastfeeding laws. We systematically examined laws protecting breastfeeding, including their current status and historical development, as well as identified gaps across US states and regions.

Key messages

-

•

Currently, the majority of the US states have legislation permitting women to breastfeed in any location and exempting breastfeeding from indecency laws; however, less than half encourage or require employers to provide break time and accommodations, prohibit employment discrimination based on breastfeeding or offer breastfeeding women exemption from jury duty.

-

•

The Northeast has the highest proportion of states with breastfeeding laws and the Midwest has the lowest.

-

•

Breastfeeding outside the home is protected to varying degrees depending on where women live; this suggests that many women are not covered by comprehensive laws that promote breastfeeding.

Materials and methods

The National Conference of State Legislatures summarised breastfeeding laws for 50 states and DC (‘51 states’) as of September 2010 (NCSL 2010). We then searched LexisNexis and Westlaw to find the full text of all laws listed, recording definitions, coverage and enactment dates. We noted penalties when they were listed in the legislation. Laws were coded into the following five categories: (1) employers are encouraged or required to provide break time and private space for breastfeeding employees; (2) employers are prohibited from discriminating against breastfeeding employees; (3) breastfeeding is permitted in any public or private location; (4) breastfeeding is exempt from public indecency laws; and (5) breastfeeding women are exempt from jury duty. Any restrictions to these laws are noted. To find new laws enacted through May 2011, we searched LexisNexis using the terms: breastfeed OR breast‐feed OR breast milk OR lactate.

First, we describe the historical development of breastfeeding laws across these five categories. We then present a detailed analysis of each law at both the state and the regional levels. We calculated the total number of breastfeeding laws and the average number of laws for each state and US Census region. The Census divides the United States into four regions: Northeast (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Vermont), Midwest (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota and Wisconsin), South (Alabama, Arkansas, DC, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia and West Virginia) and West (Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington and Wyoming).

Results

Historical development

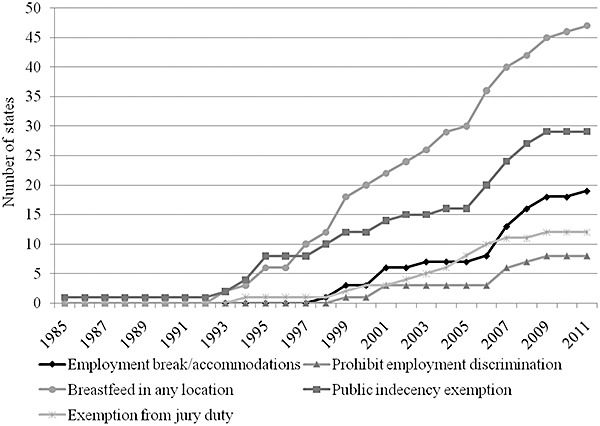

The first breastfeeding law was passed in New York in 1984 with legislation exempting breastfeeding from public indecency offences. In 1993, Florida and North Carolina enacted laws to permit women to breastfeed in any public or private location. In 1994, Iowa passed the first legislation to excuse or postpone jury duty for breastfeeding women. Beginning in 1998, laws to support breastfeeding in the workplace were enacted. Minnesota passed a law that required employers to provide break time and a private space for mothers to express milk. In 1999, Hawaii enacted the first legislation prohibiting employers from discriminating against an employee because she chose to breastfeed or express milk in the workplace. Figure 1 illustrates the development of these laws from 1984 to present. From 1993 to 2004, breastfeeding laws steadily increased at a rate of approximately five laws per year. From 2005 to 2011, the rate increased to approximately eight laws annually.

Figure 1.

Development of US state breastfeeding laws.

Overview of current laws

By May 2011, 1 state had zero laws, 10 had one, 22 had two, 12 had three, 5 had four and 1 state had laws across all five categories (Table 1). The average number of laws per state was 2.3. While 92% of states allowed mothers to breastfeed in any location and 57% exempted breastfeeding from indecency laws, 37% encouraged or required employers to provide break time and accommodations and 16% prohibited employment discrimination based on breastfeeding. Twenty‐four per cent of states offered breastfeeding women an exemption from jury duty.

Table 1.

Year breastfeeding laws were enacted for 50 US states and DC

| State | Employers encouraged or required to provide break time and private space | Employers prohibited from discriminating against breastfeeding employees | Breastfeeding permitted in any public or private location | Breastfeeding exempt from public indecency laws | Breastfeeding mothers exempt from jury duty | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | 2006 | 1 | ||||

| AK | 1998 | 1998 | 2 | |||

| AZ | 2006 | 2006 | 2 | |||

| AR | 2009 | 2007 | 2007 | 3 | ||

| CA | 2001 | 1997 | 2000 | 3 | ||

| CO | 2008 | 2004 | 2 | |||

| CT | 2001 | 2001 | 1997 | 3 | ||

| DE | 1997 | 1 | ||||

| DC | 2007 | 2007 | 2007 | 2007 | 4 | |

| FL | 1993 | 2008 | 2 | |||

| GA | 1999 | 1999 | 2 | |||

| HI | 1999 | 2000 | 2 | |||

| ID | 2002 | 1 | ||||

| IL | 2001 | 2004 | 1995 | 2005 | 4 | |

| IN | 2008 | 2003 | 2 | |||

| IA | 2000 | 1994 | 2 | |||

| KS | 2006 | 2006 | 2 | |||

| KY | 2006 | 2006 | 2007 | 3 | ||

| LA | 2001 | 2001 | 2 | |||

| ME | 2009* | 2009 | 2001 | 3 | ||

| MD | 2003 | 1 | ||||

| MA | 2009 | 2009 | 2 | |||

| MI | 1994 | 1 | ||||

| MN | 1998 | 1998 | 1998 | 3 | ||

| MS | 2006 | 2006 | 2006 | 3 | ||

| MO | 1999 | 1 | ||||

| MT | 2007 | 2007 | 1999 | 1999 | 2009 | 5 |

| NE | 2011 | 2003 | 2 | |||

| NV | 1995 | 1995 | 2 | |||

| NH | 1999 | 1999 | 2 | |||

| NJ | 1997 | 1 | ||||

| NM | 2007*, † | 1999 | 2 | |||

| NY | 2007* | 2007 | 1994 | 1984 | 4 | |

| NC | 2010*, † | 1993 | 1993 | 3 | ||

| ND | 2009 | 2009 | 2 | |||

| OH | 2005 | 1 | ||||

| OK | 2006 | 2004 | 2004 | 2004 | 4 | |

| OR | 2007 | 1999 | 1999 | 3 | ||

| PA | 2007 | 2007 | 2 | |||

| RI | 2003 | 2008 | 2008 | 3 | ||

| SC | 2008 | 2008 | 2 | |||

| SD | 2002 | 1 | ||||

| TN | 1999 | 2006 | 2006 | 3 | ||

| TX | 1995 | 1 | ||||

| UT | 1995 | 1995 | 2 | |||

| VT | 2008 | 2008 | 2002 | 3 | ||

| VA | 2001 | 2002 | 1994 | 2005 | 4 | |

| WA | 2009 | 2001 | 2 | |||

| WV | 0 | |||||

| WI | 2010 | 1995 | 2 | |||

| WY | 2007 | 2007 | 2 | |||

| Total (%) | 19 (37%) | 8 (16%) | 47 (92%) | 29 (57%) | 12 (24%) |

*Law requires the employer to provide break time for breastfeeding or expressing milk and does not explicitly state in the legislation that there is an exemption if doing so would impose undue hardship. †Law requires employers to provide private space for breastfeeding or expressing milk and does not explicitly state in the legislation that employers must merely make a reasonable effort.

There was also regional variation in the enactment of breastfeeding laws (Table 2). The Northeast had a mean of 2.6 laws, the South and West had 2.3 laws, and the Midwest had 1.9 laws. While the Northeast had the highest proportion of states with legislation in three of the five categories, the Midwest had the lowest proportion across four of the five categories.

Table 2.

Breastfeeding laws by US Census region

| Region (n states) | Employers encouraged or required to provide break time and private space | Employers prohibited from discriminating against breastfeeding employees | Breastfeeding permitted in any public or private location | Breastfeeding exempt from public indecency laws | Breastfeeding mothers exempt from jury duty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |

| Northeast (n = 9) | 56% (5) | 44% (4) | 100% (9) | 56% (5) | 0% (0) |

| Midwest (n = 12) | 25% (3) | 0% (0) | 83% (10) | 50% (6) | 33% (4) |

| South (n = 17) | 35% (6) | 12% (2) | 94% (16) | 65% (11) | 24% (4) |

| West (n = 13) | 38% (5) | 15% (2) | 92% (12) | 58% (7) | 33% (4) |

Employment break time and accommodations

Nineteen states had laws encouraging or requiring provisions for break time and private accommodations where an employee can express milk or breastfeed, often specified as other than a bathroom or toilet stall (Table 1). However, 15 of these states did not require such provisions if doing so would unduly disrupt operations. Thus, only four states (Maine, New Mexico, New York and North Carolina) required employers to provide break time without including an exemption for undue hardship. Likewise, most states with room provisions for mothers (17/19) report that employers shall make ‘reasonable efforts’ with such efforts being defined as not necessitating significant difficulty or expense. As a result, only two states (New Mexico and North Carolina) required employers to provide accommodations for breastfeeding mothers. Virginia, which was not included in the total count, passed a House Joint Resolution to encourage employers to provide unpaid break time and appropriate space for mothers to express milk or breastfeed. Indiana specified that breaks were paid only for public employees to breastfeed or express milk. Hawaii and Mississippi did not designate specific break times and private space for expressing milk; rather, both states prohibited employers from disallowing a woman to use her already existing lawful breaks to express milk. The Departments of Health in DC, Oklahoma and Rhode Island are required to issue periodic reports on benefits and complaints reported by mothers and employers as well as breastfeeding rates.

Laws in five states included coverage limitations. Illinois defined employers as those with 5 or more employees, while Oregon only required employers with 25 or more employees to provide rest periods and accommodations for breastfeeding. Indiana, Montana and North Carolina had break time and accommodation provisions for public employees only. However, Indiana also required employers with at least 25 workers to make reasonable effort to provide a private space.

We found that three states specified penalties in the legislation. California had a penalty of $100 for each violation. In Oregon, the penalty could be up to $1000 for those who intentionally violate the employment break time/room provision. Vermont employers face a civil penalty of up to $100 for each violation with jurisdiction for violations under the Vermont Judicial Bureau. Alternatively, the attorney general or a state's attorney in Vermont can enforce this provision by bringing a civil action for injunctive relief, lost wages of up to a year and expenses for the investigation and litigation. However, all three states exempted employers from providing break time if doing so would seriously disrupted operations.

There were regional differences in the enactment of laws requiring employers to provide break time and private space for nursing employees. The Northeast had the highest proportion of states enacting such laws (56%) and the Midwest had the lowest (25%) (Table 2).

Employment discrimination prohibited

Eight states prohibited employer discrimination based on breastfeeding (Table 1). In Hawaii, the Civil Rights Commission is also required to collect, assemble and publish data on instances of employer discrimination related to breastfeeding or expressing milk in the workplace. Two states restricted the law's coverage. In Montana, the law only applied to public employers including all state and county governments, municipalities, school districts and the university system. In Virginia, only employers with more than 5 but less than 15 employees were prohibited from discriminating on the basis of breastfeeding.

There was substantial variation across regions in enacting laws to prohibit employers from discriminating based on breastfeeding. While 44% of states in the Northeast had legislation in this category, the South, West and Midwest had 12%, 15% and 0%, respectively (Table 2).

Breastfeeding in any location

Forty‐seven states permitted mothers to breastfeed in any public or private location where she is otherwise authorised to be, making it the most common type of breastfeeding legislation (Table 1). Virginia's law specified that women were permitted to breastfeed only on property that was owned, leased or controlled by the state.

We found that six states listed penalties for violations. In Hawaii, violations may lead to the plaintiff being awarded attorney's fees, the cost of the suit and $100. In Illinois, women who were subject to the violation and file suit against the owner or manager of the public or private location may be awarded attorney's fees and reasonable expenses of the litigation. In Massachusetts, women who were subject to the violation and filed a civil action suit may be awarded attorney's fees and up to $500. In New Jersey, the fine was $25 for the first violation, $100 for the second and $200 for subsequent violations. In Rhode Island, women who were subject to the violation may receive injunctive relief and be awarded compensatory damages, attorney's fees and expenses in a civil action suit. Lastly, women in Vermont may file a charge of discrimination with either the human rights commission or bring action in superior court for injunctive relief and compensatory and punitive damages. The place of accommodation violating this law may be required to pay a fine of up to $1000.

The majority of states in each region had legislation that permitted women to breastfeed in any public or private location. All states in the Northeast had this legislation, while the Midwest had the lowest proportion of states with this law (83%) (Table 2).

Exemption from public indecency laws

Women who breastfeed were exempt from public indecency laws in 29 states (Table 1) and at least half of states in each region had this law (Table 2). The South had the highest proportion of states that exempted breastfeeding from public indecency laws (65%) and the Midwest had the lowest (50%).

Jury duty

Twelve states permitted mothers who are breastfeeding to postpone or be excused from jury duty upon request (Table 1). Nebraska instructed mothers to submit a physician's certificate in support of the request. While at least one‐quarter of states in the South (24%), Midwest (33%) and West (33%) had legislation permitting breastfeeding mothers' exemption from jury duty, the Northeast did not have any states with this law (Table 2).

Discussion

As of May 2011, there were gaps in the enactment of laws protecting breastfeeding both across states and regions. While 92% of states had legislation permitting women to breastfeed in any public or private location and 57% exempted breastfeeding from indecency laws, less than half of states encouraged or required employers to provide break time and accommodations, prohibited employment discrimination based on breastfeeding or offered breastfeeding women exemption from jury duty. Despite the rise in breastfeeding laws beginning in the mid‐1990s, we found that only one state had enacted all five of these laws. The Northeast had the highest proportion of states with breastfeeding laws and the Midwest had the lowest. Furthermore, when state‐level laws existed, many laws lacked enforcement provisions and few laws included penalties for violations.

This paper provides a comprehensive review of current state‐level breastfeeding laws and their historical development for all of the US. We are aware of only one study that has examined breastfeeding legislation. Murtagh & Moulton (2011) reviewed state legislation supporting breastfeeding in the workplace. They also found wide variation in coverage and requirements across states and the lack of enforcement provisions for many of these laws. By reviewing all types of breastfeeding laws, we have shown that the lack of legislation to protect breastfeeding extends beyond work sites. This suggests that many women are not protected by comprehensive laws that promote breastfeeding. There is little known about whether and/or what type of state‐level laws encourage breastfeeding and further research is needed to test the effectiveness of laws on increasing breastfeeding initiation and duration.

There are limitations in the coverage of workplace breastfeeding laws within and across states. Despite almost half of states having some type of employment legislation, only eight states have laws that prohibit employers from discriminating based on breastfeeding. Most states exempt employers from providing break time and private space if doing so would cause undue hardship or significantly disrupt operations. State laws generally defined undue hardship as actions requiring significant expense or difficulty considering the size of the business, its financial resources, or its structure and operations. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) also includes an undue hardship exemption for employers with fewer than 50 employees. In 2008, there were 5.8 million establishments in the US with fewer than 50 employees, employing 33.5 out of 121 million workers (USSBA 2008). Furthermore, Section 4207 of the ACA only covers employees that are not exempt from the overtime pay requirements of the Fair Labor Standards Act. As a result, the ACA generally covers hourly workers but not salaried employees. While both salaried and hourly workers may benefit from legislation to support breastfeeding in the workplace, ensuring at least hourly workers are covered may be an appropriate first step. Hourly workers face greater barriers to breastfeeding compared with salaried workers. They have less control in their schedules and may face possible pay reductions if they take breaks to breastfeed (USDHHS 2011). Most state‐level breastfeeding laws pertaining to the workplace do not have business size or other coverage restrictions. This is one way the state laws can provide added protection to fill in gaps left by the ACA. However, some states have laws that only cover particular groups of employees, such as public employees. Also, breaks are usually unpaid. Indiana is the only state that specifies that breaks are paid, but for public employees only. Thus, even when employers offer break time and a private space, employees may not be able to afford to take unpaid breaks. Furthermore, enforcement of these laws is minimal. We found that only three states specified any penalties for violations. Similarly, the ACA does not specify penalties for violations of the break time and accommodation provisions. Without penalties for violations or incentives to encourage compliance, the enforceability of these laws is severely limited. However, the ACA does not pre‐empt states from providing greater protection than the federal legislation. This highlights the importance of states to continue enacting stronger laws with greater protection and penalties.

The coverage of breastfeeding laws that affect all women is also highly variable. The most common type of law protects a woman's right to breastfeed in any public or private location. Without this legislation, a woman in a restaurant, shopping mall or park may be asked to stop breastfeeding or leave. While 47 states have legislation permitting women to breastfeed in any location, we found that only 6 states listed penalties for violations. Section 647 of the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act, effective in 1999, affirms that a woman may breastfeed her child at any location only in a Federal building or on Federal property where she is otherwise authorised to be (Public Law no. 106‐058). However, an enforcement provision is not included. There are also 29 states that have made breastfeeding exempt from public indecency laws and 12 states that permit breastfeeding mothers to postpone or be excused from jury duty, but none have listed penalties for violations or how compliance will be monitored. Despite an increase in the enactment of breastfeeding laws over the past decade, most have come without enforcement provisions. When there are penalties, they are often minimal. The enforceability of breastfeeding laws is limited and the laws may be viewed as less effective without substantial consequences for violations.

For any law to be effective, people need to know it exists and its significance. Employers and the public may unknowingly violate state laws that specify women's rights to breastfeed at work and in public simply because they are not aware of the laws' existence. Some states have enacted legislation for campaigns to increase the public's awareness about the importance of breastfeeding and women's legal rights related to breastfeeding (Congressional Research Service 2009). These laws can increase public awareness and support for breastfeeding and begin to change social norms around breastfeeding. How educational campaigns are implemented can vary from year to year. Campaigns may need to be continually maintained as each new year brings a new group of mothers, and the public's knowledge may fade with time without reminders or reinforcement of the message.

Breastfeeding outside the home is protected to varying degrees depending on where women live. Currently, only Montana has enacted all five breastfeeding laws and West Virginia has yet to enact a law. Furthermore, women in the Midwest are less likely to be covered by breastfeeding laws than women in other regions. Increasing the proportion of mothers that start and continue breastfeeding is a public health priority (Gartner et al. 2005; USDHHS 2010, 2011). Legislation can help this effort through reducing the barriers to breastfeeding. The inclusion of breastfeeding in the ACA and recent increases of state‐level laws are encouraging, but greater coverage at the federal and/or state level is needed to broaden and strengthen the support for breastfeeding mothers.

Source of funding

SSH is a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health & Society Scholar at the Harvard University site in Boston, Massachusetts. There was no additional funding source for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributions

SSH contributed to the study design, data analysis and drafting of the paper. TTN collected the policy data and contributed to the data analysis and drafting of the paper.

References

- Bartick M. & Reinhold A. (2010) The burden of suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: a pediatric cost analysis. Pediatrics 125, e1048–e1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor (2010) Employment Status of Mothers with Own Children under 3 Years Old by Single Year of Age of Youngest Child and Marital Status, 2009–2010 Averages Available at: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/famee.t06.htm (Accessed October 2011).

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) (2010a) Breastfeeding Report Card: United States, 2010 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htm (Accessed February 2011).

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) (2010b) HealthStyles Survey – Breastfeeding Practices: 2010 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/healthstyles_survey/survey_2010.htm#2010 (Accessed October 2011).

- Congressional Research Service (2009) Summary of State Breastfeeding Laws and Related Issues, June 2009 Available at: http://maloney.house.gov/sites/maloney.house.gov/files/documents/women/breastfeeding/062609%20CRS%20Summary%20of%20State%20Breastfeeding%20Laws.pdf (Accessed October 2011).

- Gartner L.M., Morton J., Lawrence R.A., Naylor A.J., O'Hare D., Schanler R.J. et al (2005) Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 115, 496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guendelman S., Kosa J.L., Pearl M., Graham S., Goodman J. & Kharrazi M. (2009) Juggling work and breastfeeding: effects of maternity leave and occupational characteristics. Pediatrics 123, e38–e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins S.S., Griffiths L.J., Dezateux C. & Law C. (2007a) Maternal employment and breast‐feeding initiation: findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 21, 242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins S.S., Griffiths L.J., Dezateux C. & Law C. (2007b) The impact of maternal employment on breast‐feeding duration in the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Public Health Nutrition 10, 891–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip S., Chung M., Raman G., Chew P., Magula N., DeVine D. et al (2007) Breastfeeding and Maternal and Infant Health Outcomes in Developed Countries. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 153. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan M.D., Singh G.K., Dee D.L., Belanoff C. & Grummer‐Strawn L.M. (2008) Multivariate analysis of state variation in breastfeeding rates in the United States. American Journal of Public Health 98, 1872–1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Hsia J., Fridinger F., Hussain A., Benton‐Davis S. & Grummer‐Strawn L. (2004) Public beliefs about breastfeeding policies in various settings. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 104, 1162–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal B., Roe B.E. & Fein S.B. (2010) The differential effects of full‐time and part‐time work status on breastfeeding. Health Policy 97, 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh L. & Moulton A.D. (2011) Working mothers, breastfeeding, and the law. American Journal of Public Health 101, 217–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCSL (National Conference of State Legislatures) (2010) Breastfeeding Laws Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/default.aspx?tabid=14389#Res (Accessed December 2010).

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010) Public Law No. 111‐148, Section 4207.

- Society for Human Resource Management (2011) 2011 Employee Benefits: A Survey Report by the Society for Human Resource Management Available at: http://www.shrm.org/Research/SurveyFindings/Articles/Documents/2011_Emp_Benefits_Report.pdf (Accessed October 2011).

- Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act (2000) Public Law No. 106‐058, Section 647.

- USDHHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) (2010) Healthy People 2020: Topics & Objectives. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/pdfs/HP2020objectives.pdf [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) (2011) The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General.

- USSBA (United States Businesses Administration, Office of Advocacy) (2008) Firm Size Data. Businesses by Size, 2008 Available at: http://www.sba.gov/advocacy/849/12162 (Accessed October 2011).