Abstract

Progress towards reducing mortality and malnutrition among children <5 years of age has been less than needed to achieve related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), so several international agencies joined to ‘reposition children's right to adequate nutrition in the Sahel’, starting with an analysis of current activities related to infant and young child nutrition (IYCN). The main objectives of the situational analysis are to compile, analyse, and interpret available information on infant and child feeding, and the nutrition and health situation of children <2 years of age in Mauritania as one of the six target countries (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal). These findings are available to assist countries in identifying inconsistencies and filling gaps in current programming. Between August and November of 2008, key informants responsible for conducting IYCN‐related activities in Mauritania were interviewed, and 46 documents were examined on the following themes: optimal breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices, prevention of micronutrient deficiencies, prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), management of acute malnutrition, food security, and hygienic practices. Mauritania is on track to reaching the MDG of halving undernutrition among children <5 years of age by 2015. National policy documents, training guides, and programmes address nearly all of the key IYCN topics, specifically or generally. Exceptions are the use of zinc supplements in diarrhoea treatment, prevention of zinc deficiency, and dietary guidelines for preventing mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV. Substantial infrastructure capacity building was also recently implemented in nutritionally high‐risk regions, and increases were reported in exclusive breastfeeding rates among children <6 months. The recent National Behaviour Change Communication Strategy is intended to address the needs of adapting programme activities to local needs. Despite these noteworthy accomplishments, the prevalence of acute malnutrition remains high, mortality rates did not decrease as malnutrition rates decreased, the overall prevalence of desirable nutrition‐related practices is low, and human resources are reportedly insufficient to carry out all nutrition‐related programme activities. Very little nutrition research has been conducted in Mauritania, and key informants identified gaps in adapting international programmes to local needs. Monitoring and evaluation reports have not been rigorous enough to identify which programme activities were implemented as designed or whether programmes were effective at improving nutritional and health status of young children. Therefore, we could not confirm which programmes might have been responsible for the reported improvements, or if other population‐wide changes contributed to these changes. The policy framework is supportive of optimal IYCN practices, but greater resources and capacity building are needed to (i) support activities to adapt training materials and programme protocols to fit local needs, (ii) expand and track the implementation of evidence‐based programmes nationally, (iii) improve and carry out monitoring and evaluation that identify effective and ineffective programmes, and (iv) apply these findings in developing, disseminating, and improving effective programmes.

Keywords: infant and young child nutrition, national policies, nutrition programs, monitoring and evaluation, West Africa, Islamic Republic of Mauritania

Background

The Islamic Republic of Mauritania covers 1 million square kilometres in north‐western Africa and is bordered by the Morocco‐controlled Western Sahara, Algeria, Mali, Senegal, and the Atlantic Ocean (1). Among the estimated 3.1 million inhabitants, 41% are <15 years and the population density is ∼3/km2. The per capita gross domestic product was estimated at $US2100 in 2008 with 40% of the population living below the poverty line (2004) (1). The country is divided into 13 health zones. The majority of the rural population is situated in the southern rain‐fed agriculture zone along the northern bank of the Senegal River where rainfalls reach 250–400 mm per year. Moving northward, there are also agro‐pastoral and pastoral zones, and then the mainly uninhabited desert in the north, in which there is very little annual rainfall (2). The rain‐fed planting and harvest season in Mauritania is very short, covering just June, July, and the beginning of August (3), and some flood planting occurs in the south. The primary exports are iron from the north, deep sea fish, and off‐shore petroleum (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Mauritania – map. Courtesy of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Regional Office for West and Central Africa.

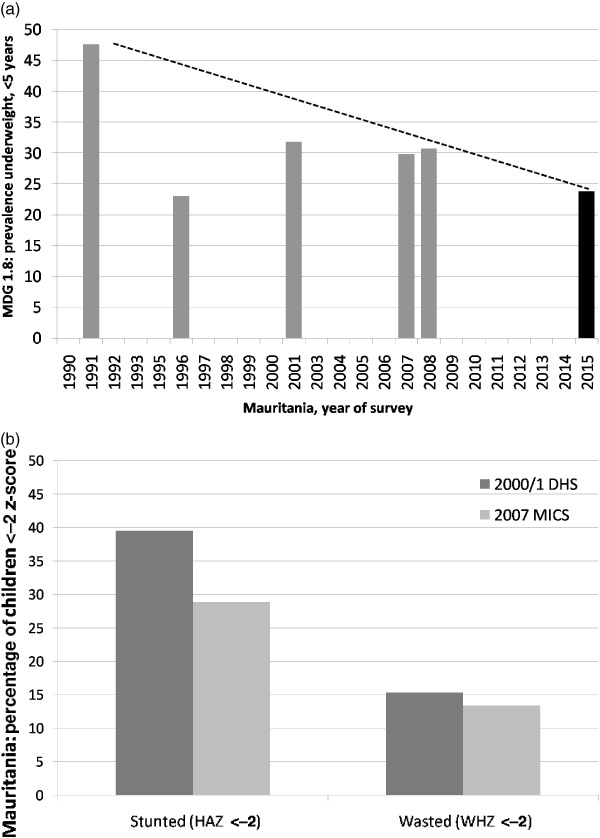

One indicator of progress towards the Millennium Development Goal (MDG), MDG #1: to half poverty and hunger by 2015 is the prevalence of underweight (weight‐for‐age z‐score <−2 among children <5 years, MDG #1.8). According to reported national survey data since 1990, Mauritania is on track to reaching this MDG. Despite this notable progress, there has been little or no change since 1996, and wasting is still very high among children <2 years of age (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Mauritania – percent of children <5 years with weight‐for‐age z‐score <−2 (WAZ), length‐for‐age <−2 (WAZ), or weight‐for‐height z‐score <−2 (WHZ). (a) Data source: http://www.childmortality.org/, from national Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) data compared with 2006 World Health Organization Child Growth Standards. Dotted line is target tragetory for Millennium Development Goal 2015. (b) Data source DHS 2000/2001 (4), MICS 2007(5).

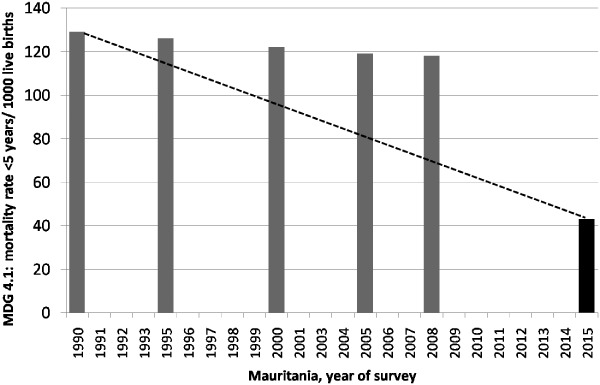

The most recent estimates for rates of mortality among children <5 years of age indicate that Mauritania is not yet on track towards MDG #4.1 to reduce mortality among children less than 5 years of age by two‐thirds by the year 2015 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Mauritania – mortality rate among children <5 years, 1990–2007, compared with 2015 Millennium Development Goal (MDG). Dotted line indicates target trajectory for MDG 4.1: to reduce mortality rates by 2/3 between 1990 and 2015. Data source: http://www.childmortality.org/; 2015 goal is 1/3 of 1990 estimate.

In 2008, National Nutrition Technical Committee was organized under the direction of the prime minister and with the assistance of the international REACH initiative (6), which was piloted in Mauritania. This committee was charged with overall supervision and collaboration on nutrition‐related activities in Mauritania. The importance of this organization was demonstrated when, following an abrupt change in government, the new government reinstated this committee and the associated National Nutrition and Development Council (CNDN in French), including regional branches of the CNDN. Infant and young child nutrition (IYCN)‐related activities are carried out within six divisions or sections within the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Agriculture, and the Ministry for the protection of women, children, and families. The Nutrition Division is placed within the Division of Basic Health Services in the Ministry of Health. In addition to the governmental and international organizations working on IYCN activities in Mauritania, more than 50 local non‐governmental organizations (NGOs) collaborated on a recent large‐scale nutrition project (7), demonstrating a strong local support for some of these nutrition activities.

The main objectives of the situational analysis are to compile, analyse, and interpret available information on infant and child feeding, and the nutrition and health situation of children <2 years of age in Mauritania as one of the six target countries (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal). Additional aims were to identify inconsistencies with international recommendations and gaps in programme activities, and to provide recommendations based on these findings to guide the development of more effective IYCN‐related programmes and activities.

Methods

From May to July 2008, the Mauritanian coordinator of this IYCN situational analysis contacted organizations involved in nutrition‐ and health‐related activities, which were identified by governmental, United Nations, and university‐based nutrition focal points. Participating organizations (see Supporting Information Appendix) completed a questionnaire regarding their IYCN activities and shared pertinent documents that we reviewed for inclusion in this analysis. The types of information obtained include (i) national policies, strategies, and plans of action; (ii) formative research; (iii) programme protocols and training materials; (iv) reports of programmes implemented, with the intended and actual programme coverage; and (v) surveys and programme monitoring and evaluation reports, with available national statistics.

Unfortunately, we were not able to obtain all documents from all agencies contacted, and some activities conducted by these organizations might not have been documented in formal reports. The analyses are limited to those documents we were able to obtain. Detailed tables of the documents, with summaries of topics addressed by each, are found in the Supporting Information Appendix. The topics reviewed in these documents include the promotion of optimal breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices, prevention of micronutrient deficiencies, management of acute malnutrition, prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), food security, and the promotion of good hygiene for optimal health (8). Because it would have been beyond the scope of these analyses to include all documents regarding HIV, food security, and hygiene, we focused on respective activities that targeted infants and young children. We found few of these programmes with specific activities targeted at young children. However, because the family's food security status has an impact on the health and nutritional status of young children, we provide a brief overview of food security tracking that is taking place in‐country along with other relevant findings.

The majority of activities identified in this review are joint activities between the relevant governmental agencies and international or national NGOs, and/or United Nations agencies.

Findings

The following sections present the findings of the situational analyses by infant and young child feeding practice and supporting nutrition‐related activities. These findings are summarized in Table 1 by feeding practice‐promoted or supporting nutrition‐related activity (rows) and by type of document reviewed (columns). The section on breastfeeding (Promotion of optimal infant and young child feeding practices) provides examples on how Table 1 was completed, and the contents are further explained in the table's footnotes.

Table 1.

Summary of actions documented in Mauritania with respect to key infant and young child feeding practices and documents reviewed (explanations found at the end of the table)

| Key practice † | Summarized findings by type of document reviewed, with selected national‐level findings* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policies | Formative research | Training/curricula | Programmes | Intended programme coverage | Actual programme coverage | Programme monitoring | Survey/evaluation | |

| Promotion of optimal feeding practices | ||||||||

| Timely introduction BF 1 h | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | National | Sub‐national | (✓) | 44% ‡ |

| EBF to 6 months | ✓ | ✓ | ✓/–✓ | ✓/–✓ | National | Sub‐national | (✓) | 11% § |

| Continued BF to 24 months | ✓ | N/I | ✓ | ✓ | National | Sub‐national | (✓) | 33% ¶ |

| 50%** | ||||||||

| Introduce CF at 6 months | ✓ | (✓) | ✓/–✓ | ✓/–✓ | National | Sub‐national | (✓) | 40% †† |

| Nutrient‐dense CF | ✓ | N/I | ✓ | (✓) | National | Sub‐national | (✓) | 30% ‡‡ |

| Responsive feeding | ✓ | N/I | ✓ | ✓ | National | N/I | (✓) | N/I |

| Appropriate frequency/consistency | (✓) | N/I | ✓ | ✓ | N/I | Sub‐national | (✓) | 8% §§ |

| Dietary assessments to evaluate consumption | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I | Food groups ¶¶ |

| Micronutrients | ||||||||

| Vitamin A supplements young children | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | National | 56%*** | MICS | N/I |

| Post‐partum maternal vitamin A supplementation | ✓ | N/I | (✓) | (✓) | National | 30% ††† | 27% increase ‡‡‡ , (7) | N/I |

| Zinc to treat diarrhoea | None | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I |

| Prevention of zinc deficiency | (Fortify) | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I |

| Anaemia prevention (malaria, parasites) | ✓ | (✓) | ✓ | ✓ | (National) | Sub‐national | 12% §§§ | 85% |

| <11 g dL−1 ¶¶¶ , (8) | ||||||||

| Anaemia prevention (iron/folic acid in pregnancy) | ✓ | N/I | ✓ | ✓ | National | Sub‐national | N/I | N/I |

| Assessment of iron‐deficiency anaemia | (✓) | (✓) | ✓ | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I |

| Iodine programmes | ✓ | N/I | ✓ | ✓ | National | 23% homes****, (8) | (✓) | MICS |

| Other nutrition support | ||||||||

| Management of malnutrition | ✓ | N/I | ✓ | ✓ | N/I | Sub‐national | (✓) | 13% WHZ |

| 25% WAZ | ||||||||

| 32% HAZ †††† | ||||||||

| Prevention MTCT HIV/AFASS | ✓ | N/I | (✓) | (✓) | N/I | N/I | 53% ‡‡‡‡ | |

| Food security | ✓ | N/I | N/I | ✓ | N/I | N/I | (✓) | ✓ |

| Hygiene and food safety | (✓) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N/I | N/I | 20% | N/I |

| 38%HH §§§§ | ||||||||

| Related tasks | ||||||||

| IEC/BCC in programmes | ✓ | N/I | ✓ | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I |

EXPLANATION OF TABLE HEADERS AND MARKINGS:

Confirmed documentation of actions specific to these key practices.

N/I

No documentation of the activity was provided or identified.

(✓)

Actions more generally related to the key practices, but without referencing the practice specifically.

Practice that is addressed but that is not specifically consistent with international norms – e.g. in case of anaemia: haemoglobin assessments are used and these cannot distinguish the cause of the anaemia, but treatments only address iron‐deficiency anaemia.

n/a

Not applicable.

† KEY PRACTICES AND RELATED ACTIVITIES AS OUTLINED IN WUEHLER ET AL., 2011 (9) , TEXT BOX 1.

Timely Introduction of BF, 1 h: commencement of breastfeeding within the first hour after birth.

EBF to 6 Months: with no other food or drink other than required medications, until the infant is 6 months of age.

Continued BF to 24 Months: continuation of any breastfeeding until at least 24 months of age as CFs are consumed.

Initiation of CFs at 6 Months: gradual commencement of CFs at 6 months of age.

Nutrient‐Dense CF: promotion of CFs that are high in nutrient density, particularly animal source foods and other foods high in vitamin A, iron, and zinc.

Responsive Feeding: encouragement to assist the infant or child to eat and to feed in response to hunger cues.

Appropriate Frequency/Consistency: encouragement to increase the frequency of CF meals or snack as the child ages (two meals for breastfed infants 6–8 months, three meals for breastfed children 9–23 months, four meals for non‐breastfed children 6–23 months, ‘meals’ include both meals and snacks, other than trivial amounts and breast milk) and to increase the consistency as their teeth emerge and eating abilities improve.

Dietary Assessments to Evaluate Consumption: indicates whether dietary assessments are being conducted, particularly those that move beyond food frequency questionnaires.

Vitamin A supplements young children: commencement of vitamin A supplementation at 6 months of age and repeated doses every 6 months.

Post‐partum maternal vitamin A: vitamin A supplement to mothers within 6 weeks of birth.

Zinc to treat diarrhoea: 10 mg/day for 10–14 days for infants and 20 mg/day for 10–14 days for children 12–59 months.

Prevention of zinc deficiency: provision of fortified foods or zinc supplements to prevent the development of zinc deficiency among children >6 months.

Anaemia prevention (malaria, parasites): iron/folate supplementation during pregnancy, insecticide‐treated bed nets for children and women of child‐bearing years, anti‐parasite treatments for children and women of child‐bearing years.

Assessment of iron‐deficiency anaemia: any programme to go beyond the basic assessment of haemoglobin or haematocrit to assess actual type of anaemia, such as use of serum ferritin or transferrin receptor to assess iron‐deficiency anaemia.

Iodine programmes: promotion of the use of iodized salt; universal salt iodization or other universal method of providing iodine with programmes to control the production and distribution of these products.

Management of malnutrition: diagnosis of the degree of malnutrition, treatment at reference centres/hospitals for severe acute malnutrition and appropriate follow‐up in the community, or local health centre; or community‐based treatment programmes for moderately malnourished children.

Prevention MTCT HIV/AFASS MTCT‐Mother‐to‐child‐transmission, HIV‐Human immuno deficiency virus AFASS: appropriate anti‐retroviral treatments for HIV‐positive women during and following pregnancy to avoid transmission to the infant, exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months, breast milk substitutes only when exclusive breastfeeding is not possible, and AFASS alternatives to breast milk are available, followed by gradual weaning or continued partial breastfeeding depending on the risk factors (see Text Box 4 of Wuehler et al., 2011 (9)).

Food security: programmatic activities with impact on infant and young child nutrition, including agency response to crises, tracking markers of food security, and food aid distributions.

Hygiene and food safety: all aspects of appropriate hand washing with soap, proper storage of food to prevent contamination, and environmental cleanliness, particularly appropriate disposal of human wastes (latrines, toilets, burial).

* CATEGORIES OF ACTIONS UNDER WHICH THE KEY PRACTICES WERE CORRECTLY ADDRESSED.

Policies: nationally written and ratified policies, strategies, or plans of action.

Formative research: Studies that specifically assess barriers and beliefs among the target population regarding each topic, and bibliographic survey of published studies identified through PubMed search of ‘nutrition’ plus either ‘child’ or ‘woman’ plus the name of the country and/or by key informant.

Training/curricula: programme protocols, university or vocational school curricula, or other related curricula that specifically and correctly addresses each desired practice, these include pre‐ and in‐service training manuals.

Programmes: documented programmes that are functioning at some level that are intended to specifically address each key practice listed.

Intended programme coverage: the level at which the programme is meant to be implemented, according to programme roll‐out plans.

Actual programme coverage: the extent of programme implementation that was confirmed in one of the received documents.

Programme monitoring: monitoring activities that are conducted for a given programme that specifically quantify programme coverage, training, activities implemented, whether messages are retained by caregivers and result in change.

Surveys and evaluations: studies that have been conducted to evaluate changes in specific population indicators in response to a programme and/or cross‐sectional surveys.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

BF, breastfeeding; EBF, exclusive breastfeeding; CFs, complementary foods; IEC, information education communication; BCC, behaviour change communication; MTCT HIV, Mother to child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus; AFASS, acceptable, feasible, affordable, sustainable and safe; MICS, multiple Indicator Cluster Survey; NCHS, National Center for Health Statistics; DHS, Demographic and Health Survey; MS‐UNICEF, Ministry of Health‐UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund; WHO, World Health Organization. ‡Percentage of women who commenced breastfeeding within 1 h of birth, MICS 2007. §Percentage of infants 0–5 months consuming exclusively breast milk, MICS 2007. ¶Percentage of infants 20–23 months consuming breast milk, MICS 2007.**Percentage of infants 20–23 months consuming breast milk, MS‐UNICEF December 2008 rapid assessment report. ††Percentage of infants 6–9 months receiving CFs in addition to breast milk, MICS 2007. ‡‡Percentage of infants 6–36 months consuming meat, fish, and poultry the day prior to the study, DHS 2000; vitamin A‐rich foods not reported. §§Percentage of breastfed infants 9–11 months who also consumed CFs at least three times in the 24 h prior to the survey (age‐appropriate frequency, MICS 2007). ¶¶Dietary data collected in MICS 2007 include consumption of food groups, but no quantities of these foods.***Percentage of children reportedly receiving vitamin A supplements in the 6 months prior to the survey, MICS 2007. †††Percentage of women (15–49 years) reportedly receiving vitamin A supplements in the 2 months post‐partum during the last pregnancy occurring during the previous 5 years, MICS 2007. ‡‡‡Percentage of increase in women reportedly consuming vitamin A supplements early post‐partum. §§§Percentage of households in which insecticide treated bed nets are reportedly available, MICS 2007. ¶¶¶Percentage of children 6–59 months with whole blood haemoglobin concentration <11 g dL−1 Hb, 2008 rapid nutrition survey.****Percentage of homes with adequately iodized salt (≥15 ppm iodine) available; this is up from MICS 2007 of 1.6%. ††††Percentage of children <5 years with z‐scores <−2, weight‐for‐height (WHZ), weight‐for‐age (WAZ), height‐for‐age (HAZ), by WHO Growth Standards, as reported in MICS 2007 (also reported data according to NCHS references). ‡‡‡‡Percentage of women 15–49 years reporting knowledge that HIV can be passed mother‐to‐child through breast milk, MICS 2007. §§§§Percentage of households in which a child's (<2 years) human wastes are disposed of in toilets, latrines, or buried and percentage of households (HH) with access to appropriate method of disposing of human wastes (toilet, latrine), MICS 2007.

The notable nutrition‐related programmes in Mauritania are the Minimum Package of Activities (PMA in French) whose goal is to integrate nutrition activities into regular health care activities, and the Nutricom project, which developed into the Project Help to the Health and Nutrition Sector (PASN in French). These latter projects promote both health centre‐based and community‐based nutrition activities. Key informants indicated that they had not yet been able to implement the nutrition components of the PMA because of insufficient human resource capacities. The Nutricom project commenced in 2000 in 3 of the 13 health zones of Mauritania where food insecurity, malnutrition, and population are the most concentrated. This project was expanded into five zones. Notable activities of the Nutricom project include (i) the creation of 117 community nutrition centres; (ii) training of 234 community nutrition agents (CNAs) to provide information, education, and communication activities through these centres; (iii) community mobilization activities; (iv) evaluation of regional nutrition rehabilitation centres followed by provision of lacking equipment and supplies; and (v) extensive collaboration with local NGOs to accomplish these activities (7). The Nutricom project's CNAs, who were literate members of the community, were trained on basic nutrition topics, such as the importance of exclusive breastfeeding (at that time to just 4–6 months) and food groups rich in energy, protein, and micronutrients; the gradual introduction of complementary foods; the importance of vitamin A supplements for children and women early post‐partum; and proper hygiene in food preparation. The training also emphasized developing educational messages based on identified local barriers and practices. Programme reports did not clarify how much support was provided to these agents following their training, to ensure that they were capable of carrying out their responsibilities.

Promotion of optimal infant and young child feeding practices

Breastfeeding

National policies, strategies, and plans of action

The three key breastfeeding practices identified in the first three rows of Table 1 are specifically promoted in the National Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding (ANJE in French) (10), as demonstrated by check marks in the first column for these three rows. The National Nutrition Development Policy (PNDN) (11) also addresses these topics, though not specifically. Other crucial breastfeeding practices addressed by the ANJE and/or the PNDN include (i) the need to practice responsive breastfeeding or to breastfeed ‘on demand’, (ii) maternity leave for breastfeeding women early post‐partum, (iii) implementation of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative practices in hospitals and community health centres, (iv) the need to implement the international code for marketing breast milk substitutes (not yet officially adopted), and (v) support for infants of women with HIV.

Formative research

Three identified studies evaluated local barriers and beliefs related to breastfeeding practices 12, 13, 14, two of which were related to programme development activities 13, 14. These surveys identified positive and negative beliefs for use in developing educational messages for their respective programmes. For example, some mothers reported that breast milk should not start for several days or weeks after birth, and there was a consistent belief that breast milk is not adequate for infants, requiring introduction of water or other liquids. This high use of water and other liquids was demonstrated in the national surveys reported below. Women in one study also reported that they trust advice from their family members over the advice of health centre personnel (14). This highlights the need to identify decision makers to target with programme interventions.

The check marks under the heading of formative research for the first two rows of Table 1 summarize the survey of beliefs related to the timely introduction of breastfeeding in the first hour and exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months. Because the continuation of breastfeeding was not discussed in these surveys and we found no research articles on breastfeeding, the third cell is filled with N/I for ‘none identified’.

Training manuals, protocols, and curricula

We received several training manuals that address the key breastfeeding practices identified in the first three rows of Table 1, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20. This is indicated by the check marks in these cells. However, many of the identified documents were developed before the new recommendations to continue exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months, so this outdated information is identified with a check mark preceded by a negative sign in the corresponding cell.

The manual for the ‘food nutrition training programme for technicians’(19) provides a recipe for home‐prepared alternatives to breast milk that is nutritionally inadequate for infants <6 months of age. Home‐prepared alternatives are no longer recommended due to the risk of poor sanitation and the inadequate nutritional quality of these alternatives. The guide for surveillance of children 0–5 years (GSE, Guide for Surveillance of Children in French) provides several useful protocols for health and nutrition (20), and most of the figures would be useful for training purposes. The Nutrition Behaviour Change Communication (BCC) Strategy (12) provides instructions on information education communication (IEC) approaches specific to breastfeeding practices, but the extent of implementation of this new strategy was not yet available.

Programmes

The Nutricom project (2000–2004) 16, 17 was implemented in five health zones through a variety of health centres and local and international humanitarian agencies and was followed by the PASN project. The minimum packet of nutrition activities (15), which also includes the promotion of optimal breastfeeding practices, is intended for national use. However, key informants indicated that the nutrition component was not yet being implemented nationally. These and other programme documents address all key breastfeeding practices but some still promote exclusive breastfeeding to just 4 months, thus the check marks under programmes in Table 1 are similar to those under training materials. Because we could not confirm that any programmes are reaching all regions of Mauritania, the intended coverage is listed as national for the PMA, but the actual coverage is listed as sub‐national for the five health zones of the Nutricom–PASN project.

Surveys, programme monitoring, and impact evaluations

We identified monitoring reports of some programmes that promoted breastfeeding, but these reports did not evaluate specifics, such as whether educational messages matched the needs of the participants or whether participants implemented the practices recommended. Therefore, these cells in Table 1 are filled with check marks enclosed in parentheses to indicate that the monitoring was not specific to the particular breastfeeding practice. The Nutricom project evaluated changes in some breastfeeding practices following the intervention, but these changes were not confirmed by comparison to non‐intervention sites and the results varied greatly by zone. No other project evaluations reported on the impact of the programme for these indicators. Therefore, in Table 1 under surveys and evaluations, we report the relevant data available through national surveys.

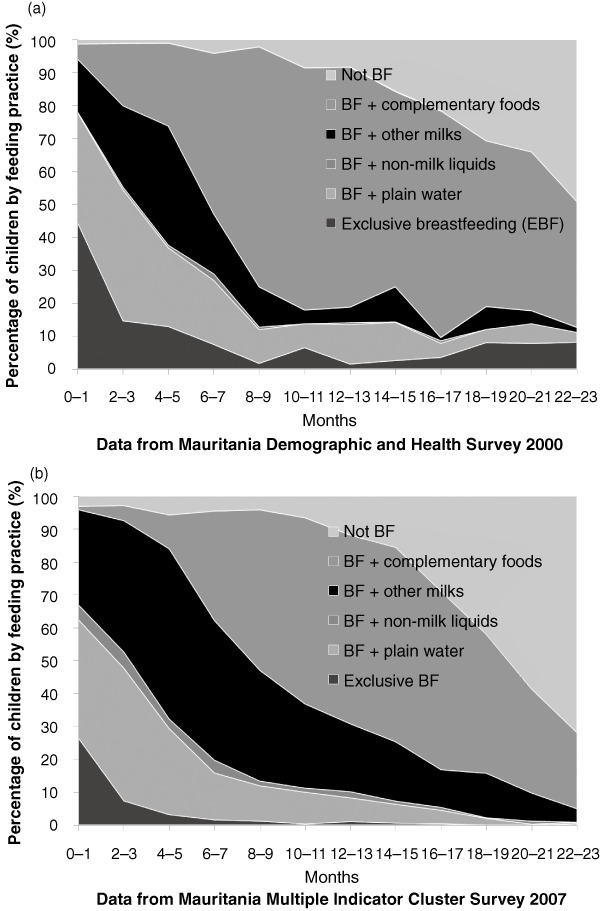

There appears to have been a decrease in exclusive breastfeeding and an increase in the use of other milks among infants <6 months of age between the 2000/1 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) (4) and 2007 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) (5) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Mauritania – national breastfeeding (BF) practices by age group. (a) BF practices by age, 2000/1 Demographic and Health Survey (4). (b) BF practices by age, 2007 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (5). EBF, exclusive breastfeeding.

For example, among infants 4–5 months of age, the reported prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding was 13% in 2000/1 and just 3% in 2007, while the reported use of other milks at this same age in these surveys was 36% and 52%, respectively. There were no programmatic explanations for these negative trends. The differences could be due to differences in data collection between the DHS and MICS, and if the standard errors were large, these differences might not be statistically important. The total prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding, reported in either survey, is well below the desired prevalence of at least 80% among infants <6 months of age.

Key informants report findings of substantial increases in exclusive breastfeeding since 2007, but final results were not yet published. The variability of these findings demonstrates the need for consistent data collection, effective programme interventions, and clear educational messages in support of optimal breastfeeding practices.

The data available in the 2000/1 DHS and 2007 MICS are adequate for calculating national breastfeeding statistics that match the recently recommended core breastfeeding indicators of infant and young child feeding (21), which will be useful for future reference.

The survey for the Grandmother project in Nouakchott (14), which included breastfeeding promotion, identified needs for (i) increased nutrition capacity among health care providers, (ii) formative research to identify more specific beliefs and decision making dynamics for use in nutrition education, (iii) community forums to engage all members in understanding the cause and prevention of malnutrition, and (iv) reinforcement of positive beliefs and practices discovered through this process. These recommendations echo the undocumented findings of the Nutricom project, that there is a need to adapt internationally recommended programmes to local needs. According to key informants, Nutricom project findings contributed to the development of the national nutrition BCC strategy (12).

Summary of findings – breastfeeding

-

•

National legislation, training materials, and programmes address all three key breastfeeding practices. In addition, a national BCC strategy for nutrition has recently been developed to aid in adapting educational messages to local needs and to improve the counselling methods used in providing these messages.

-

•

The reported prevalences of appropriate breastfeeding practices are very low.

-

•

Although breastfeeding promotion is carried out through programmes in some health zones, the national programmes were not yet functioning at the time of these analyses.

-

•

We found no monitoring and evaluation identifying whether available programmes are implementing promotional activities as designed or reasons that might explain why there is a negative trend in breastfeeding practices.

Summary of recommendations – breastfeeding

-

•

There is a need for improved monitoring and evaluation to confirm whether breastfeeding programmes are implemented as designed and to identify the impact of these programmes.

-

•

There is a need to increase human resources to implement breastfeeding promotion as designed in national programmes.

Complementary feeding

National policies, strategies, and plans of action

Several national policies and strategies promote the importance of complementary feeding practices for the health of young children 22, 23, 24, 25. In particular, the National Infant and Young Child Feeding Strategy (22) appropriately addresses the importance of commencing complementary foods at 6 months, providing complementary foods that are high in vitamin A, zinc, iron, and protein, feeding in response to the child's hunger cues and increasing the frequency of meals/snacks as the infant ages.

Formative research

In a university thesis study comparing dietary patterns among both high‐income and low‐income communities in the capital of Nouakchott (26), the author reported that all porridges provided to infants contained 35–55 kcal/100 mL (100 mL would weigh about 100 g). This energy density is below the recommended average density of complementary foods for infants of at least 80 kcal/100 g (27). Reported local barriers to optimal complementary feeding practices include beliefs that complementary foods can commence as early as birth, wait as long as 12 months of age, and can be made up of unaltered family foods 13, 14, 28. Although these are findings of small surveys, they provide data for developing more representative surveys to identify critical programmatic needs.

The 2001 survey of the Nutricom intervention zones (29) evaluated local understanding of vitamin A‐rich foods. They found that the most commonly identified vitamin A‐rich foods were carrots and beans. Beans are not a good source of vitamin A, and the vitamin A precursors in carrots are much less bioavailable than vitamin A from animal source foods. The report did not identify how or whether this information was used in improving educational messages.

Training manuals, protocols, and programme guidelines

Optimal complementary feeding practices, as outlined in Table 1, are emphasized in the training manuals for the minimum packet of nutrition activities (PMA) (15) and the Nutricom project 16, 17, 18, which was expanded into the PASN project. However, as mentioned before, the nutrition components of the PMA were not yet implemented, and the coverage of the PASN project was not documented beyond the five health zones of the previous Nutricom project. Complementary feeding was not included in the recent national BCC strategy (12).

Surveys, programme monitoring, and impact evaluations

The Nutricom project reported substantial increases in participation in child feeding programmes and participation by female caregivers in educational sessions between 2000 and 2004 (7). As described above, the project's CNAs were charged with leading these sessions. Participation increased more in the rural health zones of H. Gharbi, Assaba, and Gorgol than in the urban Nouadhibou and Nouakchott zones. This indicates that the CNAs may have had more of an impact on increasing participation in these rural zones than in the urban zones, but the report did not explain how these numbers were derived. One interesting comment in the final Nutricom report was that the community culinary demonstrations were attended by all women and not just those targeted by the programme. The general interest and participation in these demonstrations indicates these could be used to promote feeding practices to female decision makers who do not participate in the more traditional clinic‐based counselling sessions.

Between the 2000/2001 DHS and 2007 MICS, the percent of children 6–7 months of age who reportedly consumed complementary foods during the day prior to the survey decreased from 49% to 33%, respectively. Although data collection methods could have affected these reports, this is not a desirable shift and both reports are very low.

Few of the currently recommended core indicators of complementary feeding (21) were collected across national surveys for comparison across time. In 2000 (DHS), reportedly 50–70% of children 10–23 months consumed meat, fish, or eggs in the 24 h prior to the survey. These foods are generally more micronutrient dense than plant‐based foods, but these data do not clarify whether the amounts consumed were adequate for micronutrient needs. The 2007 MICS identified that just 41% of children 6–23 months of age were consuming the recommended minimum frequency of meals.

There were no other available dietary analyses to confirm whether it is feasible for children to consume nutritionally adequate local diets given available resources. The most recent annual estimations of the gross national food supply (30) indicate that 40% of available proteins are found in animal source foods. This relatively high availability of animal source protein foods may be reflected in the percent of young children who reportedly consume animal source foods in Mauritania compared with other countries included in the situational analyses 31, 32, 33, 34. Across these other countries, generally about one‐fourth of children reportedly consumed animal source foods in the previous day, and national food supplies provide just 13–28% of available protein as animal source foods.

Summary of findings – complementary feeding

-

•

Although the four key complementary feeding practices are addressed in national policies and in programmes, these programmes were not yet implemented nationally, and complementary feeding was not included in the packet of minimum activities or the national nutrition BCC strategy.

-

•

National surveys indicate that iron‐rich foods are consumed by more than half of young children 6–23 months. These assessments were not detailed enough to confirm whether the actual nutritional quality of complementary foods is adequate for young children.

Summary of recommendations – complementary feeding

-

•

As with the promotion of breastfeeding, there is a need to increase human resources to implement protocols and programmes that promote optimal complementary feeding practices.

-

•

The promotion of complementary feeding should be expanded in national programmes such as the BCC strategy and recommended PMA.

-

•

Improved programme monitoring and evaluations are needed to ensure that programmes are implemented as planned. As programmes are implemented, tracking should be carried out in both zones where the programme has commenced and in similar zones where it has not yet commenced to confirm the impact of the programme and for use in improving activities as the programme expands.

-

•

Surveys of locally available and affordable nutrient‐rich complementary foods are needed to determine which foods may be promoted in educational messages and whether local diets can be nutritionally adequate for young children, considering available resources.

Prevention of micronutrient deficiencies

Vitamin A

National policies, strategies, and plans of action

Vitamin A supplementation (VAS) is specifically promoted for children 6–59 months of age semi‐annually and for women early post‐partum through the National Vitamin A Supplementation Directives (35).

Formative research, training materials, and programmes

National guidelines describe the correct method of providing VAS semi‐annually to children 6–59 months and women early post‐partum (36). The PMA guidelines indicate that VAS should be provided through all health care facilities, in addition to promotion through the annual national vaccination programme, and national VAS campaigns are now occurring semi‐annually (37).

Surveys, monitoring, and evaluation

Although there was no national VAS campaign in 2003, and the second coverage in 2005 was less than 60% of the population, more recent reports (2009) demonstrate that Mauritania has the capacity to reach more than 90% of children 6–59 months with VAS (37). The Nutricom project reported increases in VAS among women early post‐partum, from 45% to 57% between 2000 and 2004. The most substantial increases were reported in sites where baseline coverage was the lowest. Despite this reported coverage during the Nutricom project, the 2006 MICS found just 10–31% coverage early post‐partum in these zones (5). We found no assessments of vitamin A status or consumption of vitamin A‐rich foods.

Zinc

National legislation, training materials, and programmes do not yet address the importance of preventing zinc deficiency or the use of zinc supplements in the treatment of diarrhoea. During key informant interviews, Ministry of Health officials indicated that the use of therapeutic zinc supplementation to treat diarrhoea was under discussion.

The International Zinc Nutrition Consultative Group estimated that Mauritania is at medium risk of zinc deficiency based on stunting rates among children <5 years of age, indicating that evaluations should be conducted to determine the actual prevalence of zinc deficiency, while programmes are implemented among high‐risk populations (38).

Iron and anaemia

National policies, strategies, and plans of action

Anaemia prevention is addressed in national policies 24, 39, 40 through the promotion of iron–folic acid to pregnant women, iron‐fortified foods, and the promotion of the use of insecticide‐treated bed nets (ITNs) against malaria, as one cause of anaemia.

Formative research, training materials, and programmes

As suggested in national strategies, the national PMA promotes these activities to prevent anaemia. However, we could not confirm whether these activities are promoted nationally. The Nutricom guides 16, 17 and training programme in food and nutrition for technicians (19) also promoted the consumption of some iron‐dense foods, such as liver, meat, poultry, and fish, for young children and pregnant and lactating women. Peanuts, beans, and green leaves are also promoted as good food sources of iron, but the iron in these foods is not as bioavailable as in the meat sources just mentioned.

There are no guidelines promoting the use of iron supplements to treat anaemia, except among malnourished children (41). These protocols did not yet address any risk of providing iron supplements to young children in the malaria‐endemic regions of Mauritania.

Plans are moving forward to fortify wheat flour with iron (personal communication with Helen Keller International, Senegal, which is assisting these efforts), and the micronutrient premix currently also includes zinc, folic acid, and several B vitamins. This fortified flour may have an impact on the iron status of women in child‐bearing years, but it is unlikely to be consumed in high‐enough quantities to have an impact on iron status of young children.

Surveys, monitoring, and evaluations

The rapid assessment surveys reported in 2008 8, 42 evaluated haemoglobin concentrations and found that 85% of children 6–59 months have anaemia (<11 g dL−1). Thus, there are high rates of anaemia despite the relatively high percentage of children 10–23 months who had consumed an animal source food in the 24 h prior to the 2000 DHS. Additional analyses are needed to identify the actual cause of the anaemia among these children and how to reduce this health risk through dietary or other interventions.

The special mortality and malaria survey conducted in 2003/4 found that although 56% of households had at least one bed net, only 6% of households had ITNs. There is a lower risk of malaria in the northern zones of Mauritania, and household reports indicate the fewest number of ITNs are available in these zones. These findings were similar in the 2007 MICS. In the southern regions where malaria is endemic, 8–18% of households had ITNs (43). These totals are still very low. The actual use of these bed nets was not reported in these surveys.

Iodine

National policies promote the control of imported iodized salt and the promotion of use of this salt 44, 45. Because it was beyond the scope of these analyses, we did not seek any training manuals for the evaluation of salt iodization. However, the PNDN (11) discusses training customs officials on control of the level of iodine in imported salt and training staff in health centres on promotion of iodized salt. Most of the reviewed nutrition training manuals and programme documents encourage the use of iodized salt.

A 1996 survey among Mauritanian school children (46) found that the median urinary iodine concentration was between 50 and 99 µg L−1 and 31% of the population had goitre (45). These indicate that the Mauritanian population is at mild to severe risk of iodine deficiency. Despite the above‐described national policies, the 2000 DHS (4) and 2007 MICS (5) indicated that less than 2% of households had salt with ≥15 ppm iodine, the household level of salt iodization that is considered adequate. The 2007 PASN survey (47) reported that 34% of household salt was moderately iodized while only 1% was adequately iodized, indicating a need for tighter control of the levels of iodine in salt. The more recent rapid assessment survey in 2008 (8) found that 23% of households had adequately iodized salt, indicating there may have been improvements in the coverage of salt iodization. However, this coverage is still below the goal of 90% coverage.

Summary of findings – prevention of micronutrient deficiencies

-

•

National policies, training manuals, and programmes promote the prevention of vitamin A and iodine deficiency and anaemia through VAS for children 6–59 months semi‐annually and for women early post‐partum, iron–folic acid supplements during pregnancy, deworming, the use of ITNs, and use and control of iodized salt.

-

•

VAS has reached more than 90% of children 6–59 months of age during recent national health days. The Nutricom project reported increasing coverage of early post‐partum VAS between 2001 and 2004, to 57% coverage. However, the coverage in these zones was <30% according to subsequent 2007 MICS data. The prevalence of vitamin A deficiency is unknown.

-

•

Policies, programmes, and protocols do not yet promote the prevention of zinc deficiency or the use of zinc in the treatment of diarrhoea. Plans are moving forward to fortify wheat flour with micronutrients and the current premix includes iron, zinc, folate, and B vitamins.

-

•

As with other countries in the region, anaemia is a serious health problem among children 6–59 months of age (85% (8)). We identified no studies evaluating the principal causes of anaemia for use in prevention programme development.

-

•

Salt iodization is mandated by national decree (44), and recent reports indicate that the proportion of households disposed of adequately iodized salt has increased. However, there are still less than one‐fourth of households with adequately iodized salt.

-

•

Effective programmes to prevent micronutrient deficiencies are needed to speed progress towards reducing mortality among young children

Summary of recommendations – prevention of micronutrient deficiencies

-

•

Support for VAS among young children must continue to maintain high coverage. Studies are needed to identify possible intervention sites where women can receive VAS early post‐partum, such as during early infant check‐ups.

-

•

Therapeutic zinc supplements should be integrated into the treatment of diarrhoea.

-

•

The risk of zinc and iron deficiencies should be evaluated among high‐risk populations of young children and women in child‐bearing years to guide possible prevention programmes and quantify the possible risk of providing iron to non‐iron‐deficient children.

-

•

There is a need to identify and close the gaps in the control of salt iodization, and if necessary, to pursue other methods of addressing iodine deficiency among high‐risk populations.

Other nutrition support activities

Management of malnutrition

National policies, strategies, and plans of action

National legislation promotes community‐based and centre‐based management of malnutrition 22, 23, 48.

Formative research, training materials, and programmes

We found one peer‐reviewed research article through PubMed search of an evaluation of B12 status in children with marasmus in Mauritania in 1990 (49). This was the only identified peer‐reviewed article of nutrition research in Mauritania, demonstrating a lack of support or capacities for nutrition‐related scientific research. The National Protocols for the Management of Malnutrition (41) provide specific guidelines for screening and management of acute malnutrition, including promotion of community growth monitoring and malnutrition screening (17). These guidelines also provide brief discussions of the importance of IEC during the recovery phase. The growth reference charts are not yet updated to the new World Health Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards for evaluating weight‐for‐height cut‐offs for moderate and acute malnutrition. The guide for surveillance of children 0–5 years of age, identifies moderate acute malnutrition with mid‐upper arm muscle circumference (MUAC) of 12.5 to <13.5 cm and severe malnutrition with a cut‐off of <12.5 cm. These are more strict than the international cut‐offs of 11.5 to <12.5 cm for moderate and <11.5 cm for severe malnutrition. Although the MUAC is promoted as a screening tool 19, 20, it is not clear whether malnutrition treatment could also be initiated based on a low MUAC without confirmation of low weight‐for‐height or identification of complications. Oedema is one complication used in diagnosing acute malnutrition. However, it is not also listed as a criterion for referring children to malnutrition treatment centres (20). Programme coverage was not available in identified documents.

We received a curricula outline for the State Diploma in Nursing (50) that referred to malnutrition and nutrition as general topics, but actual texts were not available for review.

Surveys, programme monitoring, and impact evaluations

We found no monitoring and evaluation reports specific to programmes managing malnutrition. The recent national nutrition surveys (8) present anthropometric analyses based on both the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) standards and the 2006 WHO Child Growth Standards, indicating a shift towards using these new standards.

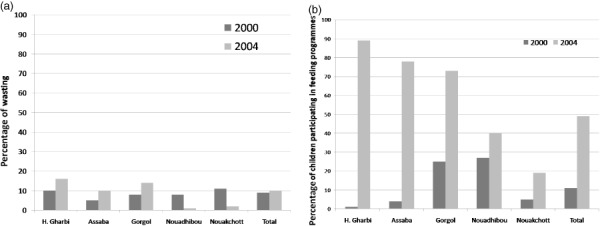

The Nutricom project reported substantial increases in participation in child feeding programmes, particularly in the more rural health zones (Fig. 5a). However, the prevalence of wasting appears to have increased in these zones during this same period. More data and more rigorous analyses were needed, but not provided, to clarify these apparent conflicting findings. For example, these data represent just baseline and follow‐up without any indication of how well the programme was implemented, the sample sizes and standard errors were not reported to determine whether there was enough data to compare across sites or from baseline, and data from non‐intervention zones were not available for comparison to determine whether the situation was actually worse in non‐intervention zones. Furthermore, although there were reported increases in health centre infrastructures, particularly in the rural zones, the timing was not available to determine whether these improvements occurred sufficiently prior to the final assessments to have an impact on desired outcomes.

Figure 5.

Changes in wasting compared with participation in child feeding programmes, from baseline, 2000, to end of the project, 2004, by health zone (7). (a) Prevalence of wasting (<−2 height‐for‐age z‐score, age not defined). (b) Percentage of children participating in child feeding programmes.

Prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV

The special needs of infants who are HIV positive or who have AIDS are addressed in the National Protocol for the Management of Malnutrition (41), but we found no infant or young child feeding guidelines to reduce the risk of mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV. This document was developed prior to the recent international recommendations for anti‐retroviral therapy (ART) in conjunction with exclusive breastfeeding for infants of HIV‐positive women (51). The national strategy to combat HIV discusses a goal to keep the level of HIV <1% in the population, but no current prevalence data were available.

Food security

The importance of food security to Mauritanian policy makers is demonstrated in the number of national legislative documents that promote methods of ensuring food security 11, 22, 23, 48, 52, 53, 54 and the number of food security surveys identified 3, 55, 56. Due to variations in indicators collected in some of these surveys, the findings could not be used to track changes across time. The Famine Early Warning System Network collects consistent quarterly food security data (http://www.fews.net/Pages/default.aspx), along with other indicators, which are available online.

The Nutricom project's child feeding programme was implemented in the health zones or ‘Wilayas’ with the highest prevalence of food insecurity, and this programme continued through at least 2008 (57).

Hygiene

Several national legislative documents identify proper hygienic practices as critical contributors to health and development 12, 40, 52, 58. Several nutrition guidelines promoted the use of proper hygienic practices in general 12, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 41, 50, but few specifics were included. The Nutricom project addressed the issue of low accessibility to potable water in its baseline surveys (59), and the final report indicated that 117 health centres involved in the intervention were equipped with reservoirs for potable water (7). Access to potable water at the household level was reportedly fairly high at baseline (73% in 2000) and after the intervention period (75% in 2004 (7)). The 2007 MICS (5) reported that 38% of households had access to appropriate methods of disposing human wastes (toilets, latrines), but just 20% of households used these methods of disposal.

Summary of findings – other nutrition support

-

•

National policies, strategies, and programmes specifically promote the prevention, screening, and treatment of malnutrition among young children. The coverage of these activities was confirmed in regions where the prevalence was highest but not in other regions.

-

•

Screening for malnutrition is based on MUAC and apparently confirmed by weight‐for‐height or weight‐for‐age of children referred to health centres or nutrition rehabilitation centres. The cut‐offs used for screening MUAC were more conservative than those recommended internationally, thus allowing referral of more children for treatment. The new WHO Child Growth Standards were not yet in use, but national surveys now compare anthropometric indicators using both the old NCHS and the new WHO standards.

-

•

The coverage of community‐based prevention and screening activities was confirmed in the Nutricom zones, but this coverage in the following PASN programme was not available.

-

•

We found no protocols or guidelines for specific feeding recommendations to reduce mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV.

-

•

Household vulnerability and food security surveys collect a wide variety of data, without harmonized methodology and indicators across agencies. Therefore, it is difficult to track certain indicators across time.

-

•

The identified nutrition‐related training materials and programme documents did not provide specifics of proper hygienic practices to support optimal nutrition practices beyond the importance of potable water.

Summary of recommendations – other nutrition support

-

•

As appropriate, specific guidelines should be included in national policies, strategies and plans of action, training materials, and programme protocols on (i) detailed malnutrition screening procedures; (ii) guidance on optimal feeding practices for infants of women with HIV, including the recent international recommendations ART and exclusive breastfeeding for infants <6 months of age whose mothers are HIV positive; and (iii) appropriate techniques for good hygiene and food safety in support of good nutrition practices.

-

•

National and international agencies should identify a basic set of harmonized indicators to collect across all food security and/or vulnerability surveys to facilitate tracking over time and across agencies.

-

•

Surveys are needed to identify barriers to using available methods of disposing of human wastes and appropriate educational messages should provide guidance on methods of maintaining proper hygiene in food preparation and storage.

General findings

Nutrition education is included in health sector training programmes in Mauritania (50), but nutrition is a limited part of these programmes, and there are no training programmes specifically for nutritionists. Although key informants were interested in sharing pertinent information, documents were not always readily available. This highlights the need for a central repository of nutrition‐ and health‐related documentation so these documents will be easily accessible when developing and updating policies, training materials, and programme protocols.

The most recent information on the human and institutional resources available to implement health programmes was found in the 1998 evaluations in preparation for the Nutricom project (59). We found no surveys evaluating the human capacities to carry out nutrition programmes. Furthermore, there was little information on how well nutrition education messages were promoted by facility staff or whether participants were applying messages received. Therefore, this situational analysis is lacking the depth of information that we hoped to find.

Summary

Nationally ratified legislation, training materials, and programmes promote most of the key IYCN practices and related activities. National collaboration across health, nutrition, and agriculture is directed by the National Nutrition Technical Committee and CNDN to improve nutrition programme coordination in Mauritania. Large‐scale improvements in health centre infrastructure were implemented in regions with high prevalence of food insecurity.

These activities demonstrate high‐level support for promoting optimal nutrition in Mauritania. However, progress towards reducing mortality among young children is not on track for reaching the MDG, and the prevalence of underweight has not decreased in the past decade. Due to inadequate programme monitoring and evaluation, it was not possible to identify any nutrition programmes that contributed to reductions in underweight in the early 1990s or to clarify why mortality did not also decrease as underweight decreased.

Nutrition‐related components of the national minimum packet of activities had not yet been implemented during our data collection, and gaps in human resources to carry out these activities were identified by key informants. These gaps were also apparent in the serious lack of nutrition‐related research in Mauritania and were identified in small‐scale surveys. According to national survey results, the prevalence is low in practices known to have an impact on reducing mortality and morbidity, such as timely introduction of breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months, and consumption of nutrient‐dense complementary foods. In addition, VAS is not consistently reaching women early post‐partum, and few women and children are using available methods of reducing the risk of anaemia and iron deficiency.

National policies and strategies form the foundation of appropriate IYCN activities in Mauritania. Continued support is needed to (i) maintain and expand, as needed, the collaborative activities of the national nutrition council and committee, (ii) increase human resources to carry out nutrition programmes and evaluations, (iii) improve nutrition‐related programmes through implementation of the nutrition portion of the minimum packet of activities and the more recent national nutrition BCC strategy, and (iv) support more rigorous programme monitoring and evaluation so that effective programmes can be clearly identified and expanded as needed.

Supporting information

mcn_308

Supporting info item

Financial support, in alphabetical order: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Helen Keller International, Micronutrient Initiative, Save the Children, United Nations Children's Fund, United Nations World Food Programme, and World Health Organization.

References

- 1. Central Intelligence Agency of the United States of America (2009) The World Factbook. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/countrylisting.html

- 2. United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS NET) (2005) Mauritania Livelihood Profiles March 2005. Available at: http://www.fews.net/livelihood/mr/Profiling.pdf

- 3. United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) (2009) Mauritania Food Security Update November 2009. Available at: http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/RWFiles2009.nsf/FilesByRWDocUnidFilename/SODA-7Z7QKS-full_report.pdf/$File/full_report.pdf

- 4. Office National de la Statistique (ONS) – Mauritanie, OCR Macro (2002) Enquête Démographique et de Santé Mauritanie 2000–2001. Office National de la Statistique (ONS) – Mauritanie et ORC Macro: Calverton, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Office National de la Statistique (ONS) – Mauritanie (2008) Enquête par Grappe à Indicateurs Multiples 2007 (MICS).

- 6. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) (2006) REACH: Ending Child Hunger and Undernutrition Initiative: Oral Report. Available at: http://www.unicef.org/about/execboard/files/Ending_Child_Hunger_background_note.pdf

- 7. République Islamique de Mauritanie (2005) Rapport d'achèvement du Projet (Draft 0). Nouakchott, March 2005.

- 8. Ministère de la Santé– Mauritanie, United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) (2008) Rapport de l'enquête rapide nationale sur la nutrition et survie de l'enfant en Mauritanie. April 2008.

- 9. Wuehler S.E., Hess S.Y. & Brown K.H. (2011) Accelerating improvements in nutritional and health status of young children in the Sahel region of sub‐Saharan Africa: review of international guidelines on infant and young child feeding and nutrition. Maternal & Child Nutrition 7 (Suppl. 1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. République Islamique de Mauritanie, Secrétaire d'Etat à la Condition Féminine, Office National de la Statistique, Projet TAGHDHIA‐NUTRICOM (2002) Rapport d'analyse des résultats de l'enquête en milieu rural: deuxième phase: milieu rural. March 2002.

- 11. Ministère de la Santé– Mauritanie , Direction des Services de Soins de Base – Mauritanie , Service de Nutrition – Mauritanie . (2007) Stratégie nationale pour l’alimentation du nourrisson et du jeune enfant en Mauritanie, septembre. 2007.

- 12. République de la Mauritanie, Satec Developpement International , Camacho M. & Ould Dehah C.M.E.H. (2008) Stratégie nationale de communication pour le changement de comportement en matière de nutrition. Draft final.

- 13. Ag Iknane A., Diarra M., Kante N., Yattara H., Traore M., Fofana A. et al (2008) Evaluation rapide de l'état de santé et nutritionnel des populations des communes de Medbougou (Prefecture de Koubeni‐Region du Hodh el Gharbi en Mauritanie) et Bamba (Cercle de Bourem‐Region de Gao au Mali).

- 14. Aubel J., Ould Yahya S., Diagana F. & Ould Isselmou S. (2006) Le contexte socioculturel de la malnutrition à Arafat, milieu périurbain de Nouakchott: L'expérience et l'autorité dans la famille et la communauté, Une étude rapide et qualitative.

- 15. République Islamique de Mauritanie, Ministère de la Santé– Mauritanie, Direction des Services de Base – Mauritanie (2007) Paquet Minimum d'Activités. Nutrition. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ministère de la Santé et des Affaire Sociales – Mauritanie, Direction de la Protection Sanitaire – Mauritanie (2000) Manuel de Formation des Formateurs des Intervenants en Nutrition Communautaire. Projet Taghdhia – Nutricom, Crédit IDA 3187 – Mau.

- 17. Sall A.M. & République Islamique de Mauritanie, Ministere de la Santé et des Affaire Sociales – Mauritanie, Direction de la Protection Sanitaire , Secrétaire d'Etat à la Condition Féminine (SECF) (2000) Manuel de Formation des Intervenants en Nutrition Communautaire. SECF/Projet Taghdhia Nutricom.

- 18. Ould Sid'Ahmed Vall M. & République Islamique de Mauritanie, Secrétaire d'Etat à la Condition Féminine (SECF) , Projet TAGHDHIA‐NUTRICOM (2001) Module de Formation en IEC/Mobilisation sociale. SECF/Projet Nutricom. January 2001.

- 19. Délegation de la Croix‐Rouge Italienne en Mauritanie, Croissant Rouge Mauritanien, Croix Rouge Italienne (n.d.) Programme de formation en alimentation – nutrition des agents auxilliaires.

- 20. République Islamique de Mauritanie, Ministere de la Santé et des Affaire Sociales – Mauritanie, Direction de la Protecton Sanitaire (1998) Guide de suivi de l'Enfant de 0 a 5 ans. April 1998.

- 21. World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), University of California Davis – Program in International and Community Nutrition (UCDavis), Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA), Academy for Educational Development (AED) et al (2008) Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices: Part I Definitions. Geneva 2008. Available at: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/9789241596664/en/index.html

- 22. Ministère de la Santé– Mauritanie, Direction des Services de Soins de Base – Mauritanie , Service de Nutrition – Mauritanie (2007) Stratégie nationale pour l'alimentation du nourrisson et du jeune enfant en Mauritanie. September.

- 23. République Islamique de Mauritanie (2004) Politique National pour le Développement de la Nutrition (PNDN). [Google Scholar]

- 24. Primature Mauritanie (2006) Politique Nationale de Développement de la Nutrition: plan d'Action Sectoriel (Nutrition dans le Système de Santé).

- 25. République Islamique de Mauritanie (ed.) (2008) Atelier d'élaboration de la stratégie nationale de survie de l'enfant en Mauritanie. Nouakchott, June 4–5.

- 26. Baro M. (2000) Pratiques de sevrage et aliments de complément à Nouakchott. Mémoire de fin d'étude Sciences et Techniques, Université de Montpelier II. Partie 2: etude descriptive sur les pratiques de sevrage en Mauritanie: Université de Montpelier II.

- 27. Pan American Health Organization & World Health Organization (WHO) (2004) Guiding Principles for Complementary Feeding of the Breastfed Child. Available at: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guiding_principles_compfeeding_breastfed.pdf

- 28. The grandmother project. Sommaire du Cadre Stratégique 2008–2012: introduction au Projet Grand‐Meres (The Grandmother Project).

- 29. République Islamique de Mauritanie, Secrétaire d'Etat à la Condition Féminine, Office National de la Statistique, Projet TAGHDHIA‐NUTRICOM (2001) Rapport d'analyse des résultats de l'Enquête sur le suivi des indicateurs de nutrition (2000–01), (Version préléminaire). June 2001.

- 30. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2010) FAOSTAT. Rome 2010. Available at: http://faostat.fao.org/site/368/DesktopDefault.aspx?PageID=368#ancor

- 31. Wuehler S.E. & Ouedraogo A.W. (2011) Situational analysis of infant and young child nutrition policies and programmatic activities in Burkina Faso. Maternal & Child Nutrition 7 (Suppl. 1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wuehler S.E. & Djasndibye N. (2011) Situational analysis of infant and young child nutrition policies and programmatic activities in Chad. Maternal & Child Nutrition 7 (Suppl. 1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wuehler S.E. & Coulibaly M. (2011) Situational analysis of infant and young child nutrition policies and programmatic activities in Mali. Maternal & Child Nutrition 7 (Suppl. 1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wuehler S.E. & Biga Hassoumi A. (2011) Situational analysis of infant and young child nutrition policies and programmatic activities in Niger. Maternal & Child Nutrition 7 (Suppl. 1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ministère de la Santé– Mauritanie, Direcion des Services de Base – Mauritanie & Service de Nutrition – Mauritanie (2007) Directives Nationales de Supplémentation en Vitamine A.

- 36. Ministére de la Santé– Mauritanie, Service Nutrition – Mauritanie (2006) Guide pour la supplémentation en vitamine A des enfant de 6 à 59 mois.

- 37. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) (2009) UNICEF Humanitarian Action Report Mid‐Year Review. Available at: http://www.unicef.org/har09/files/HAR_Mid-Year_Review_2009.pdf

- 38. Hess S.Y., Lonnerdal B., Hotz C., Rivera J.A. & Brown K.H. (2009) Recent advances in knowledge of zinc nutrition and human health. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 30 (Suppl., 1), S5–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. République Islamique de Mauritanie, Ministère de la Santé (MS) – Mauritanie (2008) Stratégie National de Survie de l'Enfant en Mauritanie (Draft 1). May.

- 40. Fonds Monaitaire International, République Islamique de Mauritanie (2007) Document de Stratégie pour la Réduction de la Pauvreté, Janvier.

- 41. République Islamique de Mauritanie, Ministere de la Santé et des Affaire Sociales – Mauritanie (2007) Protocole nationale de prise en charge de la malnutrition aiguë. March 2007.

- 42. République Islamique de Mauritanie, Ministere de la Santé et des Affaire Sociales – Mauritanie, United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) (2007) Rapport de l'enquête nationale d'évaluation rapide du stat nutritionnel et survie des enfants âgés de 0–59 mois en Mauritanie.

- 43. Office National de la Statistique (ONS) – Mauritanie , Ould Isselmou A., Ould Ekeibed M.A., Ould Mohamed M.A., Ag Bendech M., Djibi T. et al (2008) Surveillance de la Situation des Femmes et des Enfants, Enquête par Grappe à Indicateurs Multiples 2007, Rapport final.

- 44. République Islamique de Mauritanie (2005) Rapport de présentation en Conseil des Ministres.

- 45. Koita Y., Ag Bendech M. & Mubalama J.C. (2009) Les defis d'iodation du Sel en Mauritanie. Available at: http://www.iodinenetwork.net/documents/salt-sym-2009-paper-11-fr.pdf

- 46. Ntambue‐Kibambe (1996) Mauritania. IDD Newsletter 12 [serial on the Internet]. Available at: http://www.iccidd.org/media/IDD%20Newsletter/1991-2006/idd1196.htm [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ould El Joud D. & République Islamique de Mauritanie, Secrétaire d'Etat à la Condition Féminine, Projet d'Appui au Secteur de la Santé et de la Nutrition – PASN (2007) Enquête Connaissances, Attitudes et Pratiques sur la Nutrition au niveaux des zones du Projet, version provisoire. June 2007.

- 48. République Islamique de Mauritanie (2002) Cadre Stratégique National de Lutte Contre les IST/VIH/SIDA 2003–2007, Mauritanie, Août.

- 49. Feillet F., Gueant J.L., Lambert D., Djalali M., Nicolas J.P. & Vidailhet M. (1990) Vitamin B12 status in marasmic children. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 11, 283–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. République Islamique de Mauritanie, Ministere de la Santé et des Affaire Sociales – Mauritanie, Direction des affares Administrative et Financières, Service de la Formation et des Stages (1993) Programme des Etudes conduisant au Diplôme d'Etat d'Infirmier de l'Ecole Nationale de Santé Publique.

- 51. World Health Organization (WHO) (2009) Rapid Advice: revised WHO principles and recommendations on infant feeding in the context of HIV.

- 52. République Islamique de Mauritanie (2006) Cadre Stratégique de Lutte Contre la Pauvreté. Plan d'Action 2006–2010.

- 53. République Islamique de Mauritanie, Ministère de l'Agriculture et de l'Elevage – Mauritanie (2004) Lettre de Politique de Développement de l'Elevage.

- 54. République Islamique de Mauritanie, Ministère du Développement Rural et de l'Environnemnet – Mauritanie (2001) Stratégie de développement du secteur rural horizon 2015.

- 55. République Islamique de la Mauritanie, Vulnerability Analysis and Mapping (VAM), Strengthening Emergency Needs Assessmetn Capacity, United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), World Food Program of the United Nations (WFP), Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWSNET) et al (2005) Analyse de la Sécurité Alimentaire et de la Vulnérabilité (CFSVA), Données en décembre 2005 – vulnerability analysis and mapping.

- 56. République de la Mauritanie, Commisariat à la Protection Sociale et à la Sécurité Alimentaire (CPSSA), World Health Organization of the United Nations (WFP) (2008) Note de synthèse. Etude sur la sécurité alimentaire des ménages (ESAM‐08).

- 57. République Islamique de Mauritanie, United Nations World Food Program (WFP) (n.d.) Sommaire d'activité du programme du pays, 2003–2008.

- 58. République Islamique de Mauritanie, Ministere de la Santé et des Affaire Sociales – Mauritanie (2005) Politique Nationale de Santé et d'Action Sociale 2005–2015.

- 59. Ould Dehah C.M.E.H. & République Islamique de Mauritanie, Secrétaire d'Etat à la Condition Féminine, Projet TAGHDHIA‐NUTRICOM (1998) Rapport ciblage zones d'intervention du projet Nutricom: etude monographique des Wilayas Cibles, Rapport 1, Juillet 1998.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

mcn_308

Supporting info item