Abstract

Progress towards reducing mortality and malnutrition among children < 5 years of age has been less than needed to achieve related Millennium Development Goals. Therefore, several international agencies joined to ‘Reposition children's right to adequate nutrition in the Sahel’, starting with an analysis of current activities related to infant and young child nutrition (IYCN). The objectives of the present paper are to compare relevant national policies, training materials, programmes, and monitoring and evaluation activities with internationally accepted IYCN recommendations. These findings are available to assist countries in identifying inconsistencies and filling gaps in current programming. Between August and November 2008, key informants responsible for conducting IYCN‐related activities in Burkina Faso were interviewed, and 153 documents were examined on the following themes: optimal breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices, prevention of micronutrient deficiencies, screening and treatment of acute malnutrition, prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV, food security and hygienic practices. National policy documents addressed nearly all of the key IYCN topics, specifically or generally. Formative research has identified some local barriers and beliefs related to general breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices, and other formative research addressed about half of the IYCN topics included in this review. However, there was little evidence that this formative research was being utilized in developing training materials and designing programme interventions. Nevertheless, the training materials that were reviewed do provide specific guidance for nearly all of the key IYCN topics. Although many of the IYCN programmes are intended for national coverage, we could only confirm with available reports that programme coverage extended to certain regions. Some programme monitoring and evaluation were conducted, but few of these provided information on whether the specific IYCN programme components were implemented as designed. Most surveys that were identified reported on general nutrition status indicators, but did not provide the detail necessary for programme impact evaluations. The policy framework is well established for optimal IYCN practices, but greater resources and capacity building are needed to: (i) conduct necessary research and adapt training materials and programme protocols to local needs; (ii) improve, carry out, and document monitoring and evaluation that highlight effective and ineffective programme components; and (iii) apply these findings in developing, expanding, and improving effective programmes.

Keywords: infant and young child nutrition, national policies, nutrition programs, monitoring and evaluation, West Africa, Burkina Faso

Background

Burkina Faso is a landlocked country of 274 200 km2 bordered by Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast and Cote d'Ivoire, Ghana, Togo and Benin to the south (Fig. 1). Among the nearly 14.8 million inhabitants, 45% were less than 15 years of age in 2008 (1). The GDP per capita was $1200 in 2008 with an unemployment rate of 77% in 2004 (1). About 18% of the landmass is considered arable, with less than 1% devoted to permanent crops (1). Cotton is the main cash crop. Burkina Faso is divided into 13 regions and 45 provinces with approximately one health district per province.

Figure 1.

Map of Burkina Faso. Courtesy of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Regional Office for West and Central Africa.

In Burkina Faso, the rainy season lasts from about May to September. The three climatic zones are defined as the Sahel (600 mm rain/year) to the north, the Sudan‐Sahel transitional zone (mid‐range precipitation) in the middle, and the Sudan‐Guinea (900 mm rainfall/year) across the south (1). The short rainy season can lead to large fluctuations in food security due to the vulnerability of agriculture to annual fluctuations in rainfall, particularly in the Sahel and Sudan‐Sahel regions.

The main crops cultivated in the various economy zones of Burkina Faso include, in alphabetical order: cotton, fruits, garden crops, groundnuts, maize, millet and other cereals, rice, sorghum, and tubers. Additional food economy zones are defined as transhumant, or seasonal migration of livestock, and nomadic pastoralist, and cross‐border trade and tourism (2).

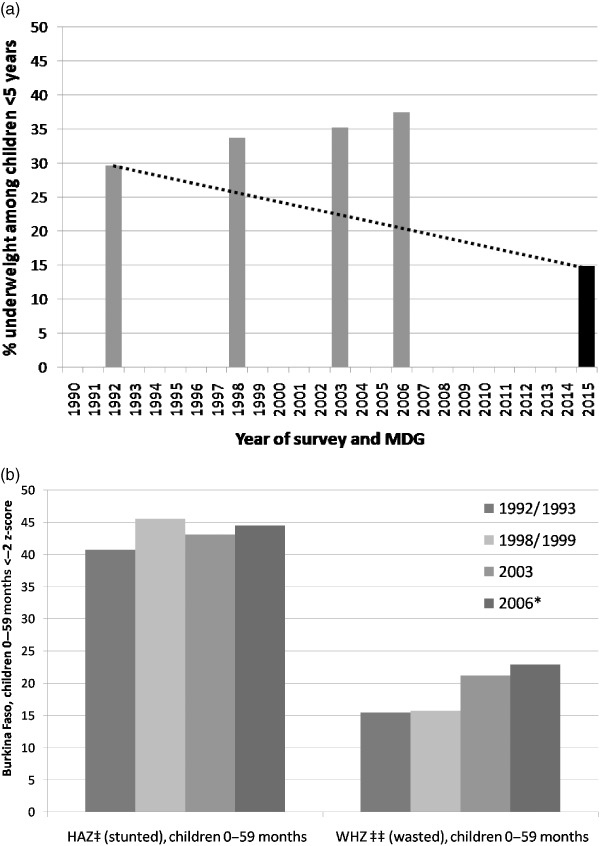

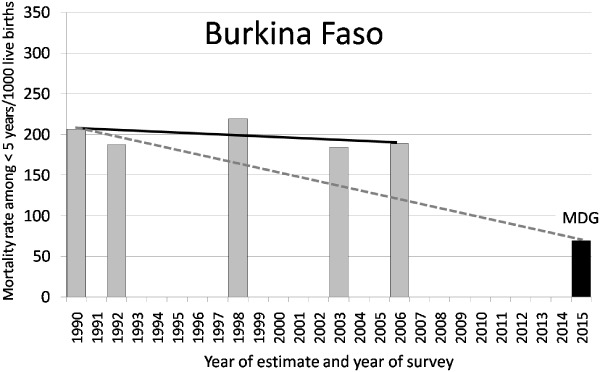

No progress has been reported in Burkina Faso towards achieving Millennium Development Goals (MDG) I: to reduce hunger by half, one indicator of which is the prevalence of underweight among children less than 5 years of age (Fig. 2); or in MDG IV: to reduce mortality among young children by two‐thirds (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Burkina Faso – changes in indicators of malnutrition and progress towards Millennium Development Goal (MDG) I, to reduce hunger by half. (a) Progress towards MDG I, as measured by prevalence of underweight, 1992 to 2006. (b) Changes between 1992/1993 and 2006 national surveys in prevalence of stunting (height‐for‐age z‐score < −2, HAZ) and wasting (weight‐for‐height z‐score < −2, WHZ) among children < 5 years of age. Underweight, stunting, and wasting according to 2006 WHO Growth Standards. Figure demonstrates reported data from 1992 to 2006 in Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) for 1992/1993, 1998/1999 and 2003 3, 4, 5 and *Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) for 2006 (6); dotted line indicates target MDG for 2015.

Figure 3.

Burkina Faso – progress towards MDG 4.1, to reduce child < 5 years mortality rate/1000 births by two‐thirds, 1990 estimate with subsequent DHS/MICS reported values; 2015 goal trajectory indicated by dotted line. Data sources: 1990 estimate from http://www.childmortality.org/; 1992, 1998/1999, and 2003 from DHS; 2006 from MICS, 2015 goal is one‐third of 1990 estimate.

The lack of progress towards these MDGs demonstrates the continued need for support of targeted nutritional and other health‐related activities for infants and young children in Burkina Faso.

Governmental and non‐governmental organizations and United Nations organizations working on infant and young child nutrition (IYCN) and related topics are listed in Supporting Information Appendix S1. The Nutrition Division coordinates nutrition activities within the structure and support of the Ministry of Health. Various aspects of IYCN activities are also carried out in other governmental organizations and ministries such as the National Centre for Scientific Research and Technology/Institute for Science and Health Research, the General Direction of Forecasting and Agricultural Statistics, the General Direction of Health, the Direction for Prevention and Early Warning, the Direction of the Health of the Family, the National Institute of Statistics and Demographics, the Ministry of Agriculture, Hydraulics and Fishery resources; the Ministry of Economy and Finances, and the Permanent Secretariat of the National Counsel for Food Security.

The National Nutrition Coordination Council (CNCN 1 in French) was created in 2008 by governmental decree (7). Participation involves key governmental, non‐governmental and United Nations organizations focused on nutrition‐related activities such as health, nutrition, agriculture, economy, and education. Meetings are intended to be held monthly to organize, collaborate, and reach policy agreement. Plans are to create decentralized CNCNs to expand these collaborations nationally. The objective of the CNCN is to ‘coordinate multi‐sectorial nutrition action, scale‐up of essential health and nutrition actions at all levels, implement effective community mobilization strategies through the dense network of local associations and strengthen the nutritional surveillance system’(8). Because this council was established shortly before data collection, the expected impact of this council's activities is not yet apparent in the reports reviewed for these analyses.

Summary of methods

Between August and November 2008, the Burkinabé project coordinator contacted organizations known to be involved in nutrition and health‐related activities specific to IYCN. Participating organizations completed a questionnaire regarding IYCN activities that they were conducting in Burkina Faso and shared 153 pertinent documents that we reviewed for inclusion in this analysis (see Supporting Information Appendix S1). Unfortunately, all relevant documents were not available for review, and some activities conducted by these organizations might not have been documented in formal reports. Therefore, the analyses are limited to those documents we were able to obtain during the time period mentioned. Because it would have been beyond the scope of these analyses to include all documents regarding HIV, food security, and hygiene, we focused on respective activities that targeted infants and young children. We found few food security programmes with specific activities targeted at young children. However, because the family's food security status has an impact on the health and nutritional status of young children, we provide a brief overview of food security tracking that is taking place in‐country.

The documents reviewed include information on: (i) national policies, strategies, and plans of action; (ii) formative research studies, including studies of local barriers and beliefs concerning IYCN‐related behaviours and peer‐reviewed research relevant to programme development; (iii) training materials and programme protocols; (iv) programmes implemented, with the intended and actual programme coverage, where available; and (v) programme monitoring and evaluation reports, including available survey results. The topics we reviewed in these documents included: breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices, prevention of micronutrient deficiencies, management of acute malnutrition, prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV, food security, and hygienic practices. The criteria for selecting these topics and the international recommendations used in comparison, are outlined in the introductory chapter in this issue (9). Reported activities and gaps in information are discussed in the following sections by feeding practices or other related activities, in the order found in Table 1. Due to the number of activities and documents reviewed, we were only able to discuss the most relevant activities in this publication. Summary tables of additional activities and documents identified are listed in Supporting Information Appendix S1 by type of document reviewed. These tables provide brief summaries of the sponsors, sites of intervention, IYCN topics discussed and occasionally some key findings reported (see Supporting Information Appendix S1).

Table 1.

Burkina Faso – Summary of actions documented with respect to the promotion of key infant and young child feeding practices and supporting activities (explanations found at the end of the table)

| Key practice promoted and related activities* | Summarized findings by type of document reviewed, with selected national‐level findings † | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policies | Formative research | Protocols/training | Programmes | Intended programme coverage | Actual programme coverage | Programme monitoring | Surveys & evaluations | |

| Promotion of optimal feeding practices | ||||||||

| Timely introduction BF, 1st h | (✓) | (✓) | ✓ | ✓ | National | Sub‐national | ✓ ‡ | 20% § |

| EBF to 6 mo | ✓ | ✓ | ✓/‐✓ | ✓/‐✓ | National | Sub‐national | ✓ ‡ | 8% ¶ |

| Continued BF to 24 months | (✓) | (✓) | ✓ | ✓ | National | Sub‐national | (✓) | 85%** |

| Introduce CF at 6 months | ✓ | (✓) | ✓/‐✓ | ✓ | National | Sub‐national | (✓) | 50% †† |

| Nutrient dense CF | (✓) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | National | Sub‐national | N/I | 14% ASF, 21% VA ‡‡ |

| Responsive feeding | (✓) | N/I | ✓ | ✓ | National | Sub‐national | N/I | N/I |

| Appropriate frequency/consistency | (✓) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | National | Sub‐national | (✓) §§ | (✓) ¶¶ |

| Dietary assessments | N/I | (✓) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | (✓)*** |

| Prevention of micronutrient deficiencies | ||||||||

| Vitamin A supplements young children | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | National | 67% ††† | ✓ | N/I |

| (Oil fortified with vitamin A) | – | – | – | – | (National: vitA fort) | (VitA fort: 70% oil) | 70% oil fortified | N/I |

| Postpartum maternal vitamin A supplementation | ✓ | N/I | (✓) | (✓) | National | 48% ‡‡‡ | ✓ | 13% §§§ |

| Zinc to treat diarrhoea | N/I | N/I | N/I | ✓ | National | Sub‐national | N/I | N/I |

| Prevention of zinc deficiency | N/I | ✓ | N/I | N/I | n/a | n/a | N/I | N/I |

| Anaemia prevention (malaria, parasites) | N/I | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | National | Sub‐national | 10% ¶¶¶ | 92%**** |

| Anaemia prevention (iron/folic acid in pregnancy) | ✓ | N/I | ✓ | ✓ | National | Sub‐national | 10% †††† | 54% ‡‡‡‡ |

| Assessment of iron deficiency anaemia | N/I | N/I | N/I | N/I | n/a | n/a | N/I | N/I |

| Iodine programmes | ✓ | N/I | ✓ | ✓ | National | Sub‐national | 32% §§§§ | N/I |

| Other nutrition support | ||||||||

| Management of malnutrition | ✓ | ✓ ¶¶¶¶ | ✓ | ✓ | National | Sub‐national | (✓)***** | <−2 Z‐score: 37% WA 35% HA 23% WH ††††† |

| Prevention MTCT HIV/AFASS | (✓) | (✓) | (✓) | (✓) | (National) | N/I | N/I | 56% ‡‡‡‡‡ |

| Food security | ✓ | (✓) | N/I | ✓ | National | National | ✓ | ✓ |

| Hygiene and food safety | ✓ | (✓) | ✓ | ✓ | National | National | 17% 40% HH §§§§§ | N/I |

| Related tasks | ||||||||

| IEC/BCC in programmes | ✓ | N/I | ✓ | ✓ | National | N/I | ✓ | ✓ |

EXPLANATION OF TABLE HEADERS AND MARKINGS:

Confirmed documentation of actions specific to these key practices.

N/I

No documentation of the activity was provided or identified.

(✓)

Actions more generally related to the key practices, but without referencing the practice specifically.

‐✓

Practice that is addressed but that is not specifically consistent with international norms – e.g. in case of anaemia: haemoglobin assessments are used and these cannot distinguish the cause of the anaemia, while treatments only address iron deficiency anaemia.

n/a

Not applicable.

* KEY PRACTICES AND RELATED ACTIVITIES AS OUTLINED IN TEXTBOX 1 OF THE DETAILED METHODS PAPER IN THIS ISSUE (9) .

Timely introduction BF, 1st h, commencement of breastfeeding within the first hour after birth.

EBF to 6 months, Exclusive Breast Feeding, with no other food or drink, other than required medications, until the infant is 6 months of age.

Continued BF to 24 months, continuation of any breast feeding until at least 24 months of age as complementary foods (CF) are consumed.

Initiation of CF at 6 months, gradual commencement of CF at 6 months of age.

Nutrient dense CF, promotion of CF that are high in nutrient density, particularly animal source foods and other foods high in vitamin A, iron, zinc.

Responsive feeding, encouragement to assist the infant or child to eat and to feed in response to hunger cues.

Appropriate frequency/consistency, encouragement to increase the frequency of CF meals or snack as the child ages (two meals for breastfed infants 6–8 months, three meals for breastfed children 9–23 months, four meals for non‐breastfed children 6–23 months, ‘meals’ include both meals and snacks, other than trivial amounts, and breast milk), and to increase the consistency as teeth erupt and eating abilities improve.

Dietary assessments to evaluate consumption, indicates whether dietary assessments are being conducted, particularly those that move beyond food frequency questionnaires.

Vitamin A supplements young children, commencement of vitamin A supplementation at 6 months of age and repeated doses every 6 months.

Postpartum maternal vitamin A, vitamin A supplement to mothers within 6 weeks of birth.

Zinc to treat diarrhoea, 10 mg day−1 for 10–14 days for infants and 20 mg day−1 for 10–14 days for children 12–59 months.

Prevention of zinc deficiency, provision of fortified foods, or zinc supplements to prevent the development of zinc deficiency among children > 6 months.

Anaemia prevention (malaria, parasites), iron/folate supplementation during pregnancy, insecticide treated bed nets (ITN) for children and women of child‐bearing years, anti‐parasite treatments for children and women of child‐bearing years.

Assessment of iron deficiency anaemia, any programme to go beyond the basic assessment of haemoglobin or hematocrit to assess actual type of anaemia, such as use of serum ferritin or transferrin receptor to assess iron deficiency anaemia.

Iodine programmes, promotion of the use of iodized salt; universal salt iodization or other universal method of providing iodine with programmes to control the production and distribution of these products.

Management of malnutrition, diagnosis of the degree of malnutrition, treatment at reference centres/hospitals for severe acute malnutrition, and appropriate follow‐up in the community, or local health centre; or community‐based treatment programmes for moderately malnourished children.

Prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission (MTCT) of Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) through, appropriate anti‐retroviral treatments for HIV+ women during and following pregnancy to avoid transmission to the infant, exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months, breast milk substitutes only when exclusive breastfeeding is not possible. Substitutes should be Acceptable, Feasible, Affordable, Sustainable and Safe (AFASS), weaning should be gradual or EBF should be followed by partial breastfeeding depending on the risk factors [see text box 4 of the detailed methods paper in reference (9)].

Food security, programmatic activities with impact on infant and young child nutrition (IYCN), including agency response to crises, tracking markers of food security and food aid distributions.

Hygiene and food safety, all aspects of appropriate hand washing with soap, proper storage of food to prevent contamination, and environmental cleanliness, particularly appropriate disposal of human wastes (latrines, toilets, burial).

‡ Categories of Documents and Selected Findings.

Policies, nationally written and ratified policies, strategies or plans of action.

Formative research, Studies that specifically assess barriers and beliefs among the target population regarding each topic and/or bibliographic survey of published studies related to programme development, as identified through PubMed search of ‘nutrition’ plus either ‘child’ or ‘woman’ plus the name of the country and/or by key informant.

Training/curricula, programme protocols, university or vocational school curricula, or other related curricula that specifically and correctly addresses each desired practice, these include pre‐ and in‐service training manuals.

Programmes, documented programmes that are intended to specifically address each key practice listed.

Intended programme coverage, the level at which the programme is meant to be implemented, according to programme roll‐out plans.

Actual programme coverage, the extent of programme implementation that was confirmed in at least one of the reviewed documents. Sub‐national refers to coverage ranging from just one district (about 45 districts nationally) to several districts or regions (13 regions nationally), but for which we could not confirm that the coverage is national.

Programme monitoring, monitoring activities that are conducted for a given programme that specifically quantify programme coverage, training, activities implemented, whether messages are retained by care‐givers and result in change.

Surveys & evaluations, studies that have been conducted to evaluate changes in specific population indicators in response to a programme and/or cross‐sectional surveys.

ADDITIONAL EXPLANATIONS

Evaluated whether pregnant women received the counselling to commence breastfeeding in the first hour or to continue exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months of age (Projet conjoint HKI/TDH: Réduction de la sous‐nutrition aiguë et de la mortalité des enfants de moins de cinq ans et des femmes enceintes et allaitantes: Rapport de l'enquête de base).

§ Per cent of infants reportedly put to the breast within one hour of birth, time period of data collection not specified, MICS 2006.

Total < 6 months exclusively breastfed, MICS 2006.

Total 22–23 months continued breastfeeding, MICS 2006.

Total 6–9 months breastfed plus complementary foods, MICS 2006.

Per cent of children < 5 years consuming animal source foods (ASF, meat, fish, poultry, eggs) or vitamin A‐rich foods (VA), DHS 2003.

§§ Research studies of acceptability/effectiveness of complementary foods processed to alter consistency.

¶¶ Frequency of consumption of certain food groups was collected in the DHS 2003 (see Nutrient dense CF), but these data did not include all meals. Therefore, total meal frequency was not available.

***Dietary data collected in the DHS 2003 include groupings of foods, but not quantity of intakes.

Per cent of children 6–59 months who reportedly received vitamin A supplement in the previous 6 months, MICS 2006.

‡‡‡ Per cent of women who reportedly received vitamin A supplement in the 8 weeks postpartum during their last pregnancy, MICS 2006.

§§§ Prevalence of reported night blindness among pregnant women, last pregnancy in the previous 5 years, DHS 2003.

¶¶¶Per cent of children reportedly sleeping under insecticide treated bed net the night prior to the survey, MICS 2006.

Prevalence of anaemia (whole blood haemoglobin concentration < 11 g dL−1) among children 6–59 months, DHS 2003.

Per cent of women who took ≥ 90 days of iron‐folic acid supplementation during previous pregnancy, DHS 2003.

Prevalence of anaemia (whole blood haemoglobin concentration < 11 g dL−1) among women 15–49 years, DHS 2003.

§§§§ Children living in homes with iodized salt, MICS 2006.

¶¶¶¶ Research studies of processed foods used to increase nutrient density of malnutrition treatment diets.

*****Monitoring of Axios‐led nutrition rehabilitation centers found the need for increased training, see section on malnutrition.

Per cent of children < 5 years with <−2 z‐score for weight‐for age (WA), height‐for‐age (HA) and weight‐for‐height (WH) according to WHO Growth Standards, as printed in MICS 2006.

‡‡‡‡‡ Per cent of women able to identify that HIV could be transmitted to the infant from an infected mother during pregnancy, birthing and lactation, MICS 2006.

§§§§§ Per cent of households in which hygienic practices are followed for disposal of children's human wastes and per cent homes with access to hygienic method of this disposal, MICS 2006.

Results

The wide range of the activities reported in the documents that were retrieved demonstrates the government's awareness of the existing nutritional problems and its commitment to implement appropriate actions to improve the health and nutritional status of Burkinabé infants and young children.

The findings of our analyses are summarized in Table 1 by feeding practice promoted, and by other nutrition‐related activities (rows), and by type of document reviewed with identified programme coverage and some related national statistics (columns). The following section on breastfeeding provides examples on how to interpret the information provided in Table 1, and the contents are further explained in the table's footnotes. The majority of activities identified in our review are joint activities between the relevant governmental agencies and international or national non‐governmental organizations (NGOs) and/or United Nations agencies. We found little information on the actual human and institutional resources available to implement these programmes, how well individual educational messages were promoted by facility staff or whether participants were applying messages received. Therefore, this table and this situational analysis are lacking the depth of information that we hoped to find in commencing this process.

Promotion of optimal infant and young child feeding practices

Breastfeeding

National policies, strategies, and plans of action

Exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months of age is promoted through the National Health Policy (10) and the National Nutrition Action Plan (11). Thus there is a checkmark in the policy column for this topic in Table 1. The National Nutrition Policy and Action Plan also encourage use of the Essential Nutrition Actions (ENA), which include the promotion of the introduction of breastfeeding within the first hour of life and the continuation of breastfeeding to 24 months of age. However, because these two breastfeeding practices are not specifically promoted in national policy documents, it might be construed that these practices are not as important for the health of infants and young children as is exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months of age. Therefore, we have placed a checkmark inside parentheses in Table 1 next to these two breastfeeding practices to indicate that national policies only promote these practices indirectly. Additional national support for breastfeeding is found in an official national decree regulating the use of breast milk substitutes (12) and promotion of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative and the international code for the use of breast milk substitutes (10).

Formative research

Due to the importance of adapting educational messages and programmes to local needs, we searched for studies that identified local barriers and beliefs related to the promoted breastfeeding practices. One identified study, conducted in selected populations of all 13 regions of Burkina Faso, inquired into beliefs regarding breastfeeding initiation and exclusivity (13) and a second study was conducted in just one health district out of ∼45 health districts nationally (14). Each of these studies identified negative beliefs regarding breastfeeding, such as the belief that colostrum is ‘dirty’ and that breastfed infants also require water to quench their thirst. Positive beliefs that were identified in the smaller study included that breastfeeding ensures a strong emotional attachment between the mother and child and that breastfed children are healthier than non‐breastfed children. These are important local beliefs that should be dispelled or promoted, as appropriate, in educational messages to promote optimal breastfeeding practices. Unfortunately, we found no evidence that relevant training materials were adapted to incorporate these findings.

Because some of the above studies evaluated beliefs or activities directly related to exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months, the respective cell in Table 1 is a checkmark. These studies also addressed reasons why mothers might not give colostrum and reasons for continuing breastfeeding. However, in terms of programme development, these studies did not evaluate specifically reasons for or against introduction of breast milk in the first hour after birth, or continuation through at least 23 months of age. Therefore, because these topics are addressed indirectly, these cells are filled with checkmarks in parentheses.

Protocols and training materials

The ENA training manual (15), the manual for the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) guidelines for the mother (16) and the guidelines for optimal infant and child feeding (17) provide training guidelines for all three key breastfeeding practices and are intended for use nationally. The ENA presumably replaces the Minimum Packet of Nutritional Activities (18), which was promoted in 2005. None of these documents were adapted to provide educational messages specific to local beliefs and practices. Because these documents clearly recommended the three key breastfeeding practices, Table 1 includes checkmarks in the appropriate column and rows for ‘Training materials’. We also found two documents that still recommended breastfeeding to just 4–6 months of age 18, 19, so the row for exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months also includes a checkmark preceded with a negative sign to indicate that documents containing this outdated recommendation are still in circulation.

Programmes

Breastfeeding is promoted through the government supported IMCI programme's ‘Counsel for mothers’(16), the ENA approach (15), the ‘Practical guide for optimal nutrition’(17) and the ‘Minimum packet of nutritional activities’(18). A 2005 document describes plans to implement the IMCI in all heath districts, at least 60% of health centres and 70% of households by 2010. No subsequent monitoring reports were available to confirm the actual coverage of this programme. We also found little monitoring of whether nutrition education messages are actually provided to participants. Several other programmes, which are supported by NGOs in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, also promote optimal breastfeeding practices at the district‐level (see Supporting Information Appendix S1). Although several identified programmes promote some aspect of breastfeeding, just three of the nine relevant programmes promoted all three key practices. The checkmarks in Table 1 for ‘programmes’ are similar to those for training materials because we also found outdated recommendations to continue breastfeeding to just 4 months in a programme implemented in five regions (20). Although these programme activities are intended for national implementation, we could only confirm that they had been implemented in certain districts or regions. Therefore, the columns in Table 1 for intended and actual coverage indicate these practices are intended to be promoted nationally, but we could only confirm that they are promoted in certain areas or ‘sub‐nationally’.

Surveys, monitoring, and evaluation

In the following, ‘surveys’ refer to cross‐sectional data collection among a given subset of the population. These surveys are not necessarily related to a programme or study. ‘Monitoring’ refers to studies that evaluate the implementation of a specific programme and whether it is implemented according to protocol. ‘Evaluation’ refers to findings regarding the outcomes or impact of a programme. We identified monitoring reports that collected data such as whether responsible individuals were trained on recommended breastfeeding practices or the number of participants in a programme, but few reported whether mothers actually received the intended recommendations or educational messages. One exception is a study that evaluated breastfeeding topics provided to about 100 women per district in three health districts (21). Depending on the breastfeeding topic, the per cent of women who received appropriate breastfeeding counselling ranged from just 1 to 44%, indicating a serious need for additional support for the promotion of appropriate breastfeeding. The reasons for the gaps in counselling were not evaluated. Because this study reported whether recommended counselling was provided to mothers on the promotion of breastfeeding in the first hour and continuation of exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months in these three districts, the relevant cells in Table 1 include checkmarks under ‘programme monitoring’. The checkmark in the third cell under monitoring is in parentheses to indicate that general breastfeeding promotion was evaluated, but the authors did not evaluate whether mothers were encouraged to breastfeed until children are at least 24 months of age. Because we found no evaluations that reported whether breastfeeding practices changed in response to programme intervention sites compared with non‐intervention sites, it is not possible to confirm whether any of the programme approaches currently applied in Burkina Faso are effectively improving breastfeeding practices. Due to this lack of evaluations for breastfeeding programmes, and a similar lack in programme specific evaluations for most of the following topics, the values reported under ‘surveys and evaluation’ in Table 1 refer to the relevant national findings of the most recent DHS or MICS surveys.

The findings of the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) conducted in Burkina Faso since 1990 indicate that breastfeeding promotion activities have had little or no impact on improving breastfeeding practices. There appear to have been improvements in 2003 compared with other years in timely introduction of breastfeeding and in exclusive breastfeeding at 4–5 months of age, but statistical analyses were inadequate to compare data across surveys (Table 2). Exclusive breastfeeding remains an uncommon practice among infants less than 6 months of age.

Table 2.

Burkina Faso – Breastfeeding indicators reported between 1992 and 2006 by Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS)

| Breastfeeding indicator | 1992 DHS (3) | 1998 DHS (4) | 2003 DHS (5) | 2006 MICS (23) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Timely introduction of breastfeeding in the first hour after birth (TIBF)* | 28.1 | 25.2 | 33.3 | 19.6 |

| % Infants 4–5 months exclusive breastfed during previous day | 2.3 | 6.4 | 16.0 | 3.9 |

| % Infants 0–5 months exclusively breastfed during previous day* | 2 | 5.2–5.8 † | 18.8 | 7 |

| % Children 12–15 months breastfed during the previous day* | 96 | 97.6–98.5 [Link] , [Link] | 98.1 ‡ | 96.1 |

| % Children 22–23 months breastfed during the previous day | 79.1 | 82.7 | 75.4 | 82.6 |

Descriptive statistics, such as standard deviations were not reported, so differences between surveys cannot be confirmed. *These are ‘core indicators’ recommended by international counsel to evaluate and track national breastfeeding practices (22). †1998 values not reported at exact ages for this indicator. Thus, values for exclusive breastfeeding are the range for reported prevalences among infants 0–1, 2–3, and 4–5 months (1998), and the prevalences of any breastfeeding among children 12–13 and 14–15 months. ‡Values calculated as the difference from 100% of children who were not breastfed.

The data necessary to calculate the infant and young child breastfeeding indicators recommended in 2008 by international consensus (22) are available in these DHS and MICS surveys, and some indicators were already calculated. Therefore, it will be possible to include these indicators in subsequent survey reports without the addition of further questions.

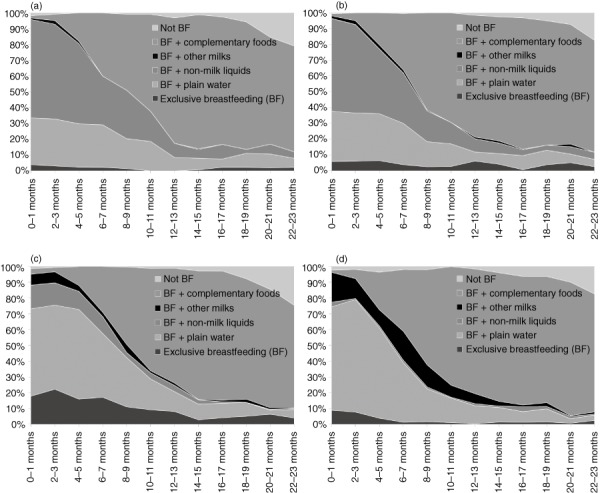

Although the use of non‐milk liquids other than water appears to have been high in 1992 and 1998, the majority of non‐exclusively breastfed infants in 2003 and 2006 appear to be receiving just water Fig. 4, 3, 4, 5, 23). Again, statistical analyses do not confirm whether this is an actual shift. If this was a real shift in practices, there may have been progress in discouraging non‐milk liquids other than water prior to 6 months of age during this period, but water is still commonly used prior to 6 months of age. As explained in the introduction to this supplement issue (9), researchers have demonstrated associations between non‐exclusive breastfeeding and increased prevalence of diarrhoea and respiratory infections among young infants. Therefore, there is a great potential for improving the health and well‐being of infants in Burkina Faso through continued efforts to promote exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life.

Figure 4.

Burkina Faso – breastfeeding practices by age according to Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) (1992/1993, 1998/1999, 2003) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) (2006) 3, 4, 5. (a) DHS 1992/1993. (b) DHS 1998/1999. (c) DHS 2003. (d) MICS 2006.

Despite low rates of the timely introduction of breastfeeding in the first hour and exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months of age, continued breastfeeding is a common practice in Burkina Faso (23).

Thirteen structures were at one time certified as ‘Baby Friendly’ facilities in the cities of Ouagadougou and Bobo‐Dioulasso, but a 2007 survey reported that support was needed to reanimate and rebuild the capacity necessary to continue this initiative in these facilities (24). The denominator was not reported, but there were only about 13 likely facilities functioning at the time of the survey. Aguayo et al. (25) also evaluated implementation of the International Code of Marketing Breast Milk Substitutes. They identified a number of Code violations, including gifts and educational materials from manufacturers of breast milk substitutes in health facilities, and less than half of the interviewed health providers working in Baby Friendly Hospital facilities had received relevant training on the Code.

Summary of findings – breastfeeding

-

•

National policy documents promote exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months and promote the ENA that, in turn, promote all three key breastfeeding practices.

-

•

Research results covering most of the regions of Burkina Faso are available on barriers to optimal breastfeeding practices, such as reasons for not providing colostrum. However, we found no adaptations in training materials and programme protocols to incorporate these findings.

-

•

All three key breastfeeding practices were addressed in at least one of the identified training documents and programmes, although some outdated materials are still in circulation.

-

•

The actual application of the breastfeeding counselling recommended in these programmes was only reported in one survey, which found that <10% of women had received counselling regarding exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months, initiation of breastfeeding in the first hour or the use of colostrum.

-

•

National survey results of the core indicators of breastfeeding practices indicate that the timely introduction of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life remain low, but most children are breastfed to nearly 24 months of age 3, 4, 5, 23

-

•

There is a need to increase human capacity to carry out programmes promoting optimal breastfeeding practices.

Summary of recommendations – breastfeeding

-

•

Although the key breastfeeding practices are promoted in the national nutrition policy through the ENA, high‐level political support for all three key practices would be better emphasized with direct promotion of these practices.

-

•

Effective monitoring and evaluation activities are necessary to confirm whether breastfeeding components of current programmes are being implemented as designed and whether these activities are having the desired impact on improving breastfeeding practices.

-

•

Programmes and training materials should be altered or updated as needed according to the findings of programme evaluations and population surveys of barriers and beliefs regarding breastfeeding practices.

-

•

Increased support for improved supervision, training is needed to ensure that health providers can provide the necessary counselling and education to have an impact on breastfeeding practices.

-

•

As new national nutrition surveys are conducted, it is recommended to include calculations of the core indicators now recommended for evaluating national infant and young child feeding practices. Where possible, these indicators can also be calculated using previous data for comparison.

Complementary feeding

National policies, strategies, and plans of action

Introduction of complementary feeding at 6 months of age is specifically addressed in the National Nutrition Action Plan (11). As with breastfeeding, the other three key complementary feeding practices (promotion of the use of nutrient‐dense complementary foods, gradual increase in frequency and consistency of these foods, and feeding in response to hunger cues) are only referred to through the promotion of the ENA (10).

Formative research

A substantial amount of IYCN‐related research in Burkina Faso addresses processing methods such as fermentation to improve the quality and acceptability of complementary foods (see Supporting Information Appendix S1). However, few studies have tested food processing methods in population‐based studies to evaluate their impact on nutritional status of children or feasibility that caregivers will utilize these methods.

In a recent study, Ouedraogo et al. (26) reported on an intensive home‐based technology transfer for preparing a complementary food from foods frequently grown at home: millet, sorghum, beans, and peanuts; plus some purchased items: sugar, simbala (a fermented bean product) and iodized salt. They found that it was possible to train housewives in 27 study villages to process these ingredients in such a way to prepare a complementary food product with average nutrient contents of 1.8–2.6 mg iron, and 1.2–1.7 mg zinc in 100 calories of the final product, which is similar to recommended concentrations of these nutrients in complementary foods intended for children 9–24 months of age (27). The authors reported that the cost of the ingredients were likely affordable for participants, but the cost analysis of the time required for the intensive processing was not included in their assessment. The researchers expected the bioavailability of the iron and zinc to be high due to the processing techniques used, but they did not evaluate the impact of the product on children's nutritional status. Although these findings are promising, it is unlikely that current health centre education activities would be adequate to train caregivers on the intensive processing techniques described, and the time required might make this processing too labour intensive for caregivers. Further research would be needed to determine whether this methodology could feasibly be transferred to caregivers through typical health centre settings.

Training materials and programme documents

All four key complementary feeding practices are specifically addressed in the national‐level ENA guidelines (15) and some of these practices are addressed in IMCI and other Ministry of Health and NGO supported training materials and programme documents (see Supporting Information Appendix S1). The 2005 Practical guide for optimal infant and young child feeding (17), which was developed by the Ministry of Health and Nutrition Division included recipes for preparing complementary foods, presumably for use in health centres. These recipes did not include an explanation of fermentation, one processing method that was found to improve the nutritional quality of local complementary foods (see Supporting Information Appendix).

As described in the section on breastfeeding, there are plans to extend the coverage of the IMCI programme in health centres and communities to nearly national levels by 2010 (28), but the current coverage was not yet available. As with programmes that promote breastfeeding, there is a variety of district or region‐level programmes that also promote complementary feeding practices, though generally with fewer details on optimal methods of complementary feeding practices than for the promotion of breastfeeding (see Supporting Information Appendix S1). One community nutrition pilot study/programme was initiated in two health districts in 2008, in which the ENA approach was included with the promotion of home gardens (29). The impact was not yet available. Community‐based production of complementary foods, similar to the complementary food described above under formative research, is also promoted in at least three health districts (of ∼45) under the title of Nutrifaso or ben‐sogho 30, 31, 32, 33, 34. These projects were mainly promoted by local research institutes that work with the permission of the appropriate governmental agencies. For example, the Nutrifaso community project provided educational messages in three health districts on topics such as health care, hygiene, vaccinations, exclusive breastfeeding, complementary feeding after 6 months of age, prenatal care, and nutrition. Reportedly 42–71% of residents had heard of or participated in promotional activities, and 79% of interviewed caregivers had actually used the complementary food. There were no evaluations of the impact of the programme on the nutritional status of children in the intervention area.

The Prolonged Programme for Assistance and Recuperation (IPSR/PPRO) (35) was a two year programme based on promoting food security in the five regions most affected by food insecurity. The programme provided supplemental food, such as corn/soy blend, legumes and oil, to malnourished children and to pregnant and lactating women during the first 4–6 months postpartum. Additional activities included the promotion of anti‐parasite treatment, proper hygiene, exclusive breastfeeding, and access to basic health care. The results of some programme evaluations are provided in the following section.

Surveys, monitoring, and evaluation

Nationally representative survey data for the 2003 DHS (5) found that only 45% of infants 6–9 months had consumed complementary foods in the 24 h prior to the survey. Just 8% of these infants had consumed vitamin A rich foods and 6% had consumed a food expected to be rich in iron (meat, fish, poultry, or egg). Additionally, consumption of vitamin A‐ or iron‐rich foods, during the day prior to the survey, at 20–21 months of age was very low, only about 12 or 36%, respectively. These intakes are well below recommendations, indicating that any activities to promote the consumption of complementary foods commencing at 6 months, and to introduce nutritionally rich complementary foods were not yet achieving desired results.

Although the 2003 DHS included many questions regarding complementary feeding, the data necessary to calculate the infant and young child complementary feeding indicators recommended in 2008 by international consensus (22) are not all available. The indicator on the consumption of complementary foods at 6–8 months of age can already be calculated using data available from the 2003 DHS.

Because quantity of foods consumed is not assessed in DHS, it is not certain whether the amounts of vitamin‐A or iron‐rich foods reportedly consumed are sufficient to meet children's daily requirements. To date, there are insufficient data to calculate the recommended core feeding indicators of minimum diversity, minimum meal frequency and minimum acceptable diet.

The ENA approach, which is the most complete nationally available document to promote optimal complementary feeding practices, was published in 2008 in Burkina Faso, several years after the most recent dietary data available in the 2003 DHS. There are no data yet available to determine whether the implementation of the ENA approach is reaching national coverage or if there have been improvements in complementary feeding practices since its introduction.

The evaluations of the Prolonged Programme for Assistance and Recuperation (IPSR/PPRO), promoted in 5 of the 13 regions, were not very promising 36, 37. The authors reported that the overall diversity score did not improve across the 12 months of the project and the average number of meals consumed by children less than 5 years remained nearly the same (mean diversity score at baseline: 4.4 ± <0.1; 12 months: 4.5 ± 1.2). The only change that may have been significant was a decrease in the percentage of homes where legumes, fruits and vegetables, and dairy products were consumed (reductions of 21, 57 and 47%, from baseline to 12 months, respectively). Although still fairly large, the sample size dropped considerably from baseline to 6 and 12 months (n = 3568, 690 and 643, respectively). Because statistical analyses were not conducted and there were no non‐intervention groups for comparison, the meaning of these findings is unknown. For example, there may have been food crises in the region leading to even greater reductions in optimal complementary feeding practices in non‐intervention sites than those observed in the intervention sites.

Summary of findings – complementary feeding

-

•

National policy documents promote complementary feeding practices through the promotion of the ENA in which all four key complementary feeding practices are promoted.

-

•

Researchers have evaluated several aspects of the nutrient quality and acceptability of complementary foods through home and centralized production. The impact of these products or projects on children's nutritional status was not evaluated, so their effectiveness cannot be confirmed.

-

•

National‐level training materials and programmes promote the key complementary feeding practices, but the actual extent of coverage of these programme components was only confirmed in certain regions or districts where evaluations were conducted.

-

•

National surveys have found that only about 80% of children are consuming complementary foods by 12 months of age, and very few children are consuming vitamin A‐ and iron‐rich foods. These findings indicate that efforts are needed to improve the impact of programmes promoting nutrient‐dense complementary foods.

-

•

We found no studies with adequate statistical analyses to confirm whether implemented programmes are having a positive impact on feeding practices, either nationally or following smaller interventions.

Summary of recommendations – complementary feeding

-

•

National nutrition policies should be expanded to ensure high‐level support for the key complementary feeding practices by promoting these practices directly, rather than just through the promotion of the ENA.

-

•

In order to enhance the effectiveness of programmes, there is a need for research‐based adaptations to programmes and educational messages that promote optimal complementary feeding practices.

-

•

Rigorous monitoring and evaluation is needed to ensure that the resulting programmes are implemented as designed.

-

•

The lack of programme specific monitoring and evaluation reporting indicates there may be inadequate understanding of how these reports could be used to improve programming, or there may be insufficient human or financial capacities to complete appropriate evaluations.

-

•

As new national nutrition surveys are conducted, it is recommended to include calculations of the core indicators now recommended for evaluating national infant and young child feeding practices. Where possible, these indicators can also be calculated using previous data for comparison.

Prevention and treatment of micronutrient deficiencies

Vitamin A

National policies, strategies, and plans of action

The National Nutrition Action Plan (11) promotes national dissemination of vitamin A supplementation (VAS) within 1 month postpartum. The importance of preventing vitamin A deficiency is discussed in the National Health Policy (10) and the National Plan for Health Development (PNDS) (38). The specifics of providing VAS semi‐annually to children 6–59 months is addressed according to international guidelines in a supporting document for the PNDS (39).

Formative research

Locally available vitamin A‐rich foods that were identified by researchers include mango, liver, and red palm oil (40). One set of researchers evaluated the impact of weekly in‐home promotion of mango and liver on vitamin A status among 150 children 2–3 years of age, during 15 weeks of intervention, compared with the same intervention plus financial support. Serum retinol concentrations increased significantly from baseline in both groups, and there was reportedly no difference between the two groups. These findings imply that families were able to increase mango and/or liver consumption even without the additional finances provided to one group. However, the total increase in liver consumption was reportedly higher in the group that received financial support than in the group without financial support.

Red palm oil was promoted as a source of vitamin A in a 2‐year study among 10 000 women and children in seven project sites of central‐north Burkina Faso, of which 210 mother–child pairs were randomly selected for evaluation (41). Among children, the risk of inadequate vitamin A intake dropped from 87 to 60%, based on dietary intakes of vitamin A‐rich foods, and the prevalence of low serum retinol concentrations (<0.70 µmol L−1) decreased from 84.5 ± 6.4 to 66.9 ± 11.2% (P = 0.004). The fact that participants voluntarily purchased the red palm oil indicates this approach to improving vitamin A status may be financially feasible. Nearly all of the children had consumed vitamin A supplements 6 months prior to the intervention, which may have masked the findings. These two studies provide promising findings using locally available foods to improve vitamin A status, which may be affordable for the target populations. However, neither programme reduced the prevalence of vitamin A deficiency to desirable levels, so additional interventions are still indicated in addition to these interventions.

Based on the presence of clinical signs of vitamin A deficiency as identified by night blindness, and of parasites among children 2–18 years, other researchers identified intestinal parasites as the primary non‐nutritional cause of vitamin A deficiency among 3597 children between the ages of 2 and 14 years living in one health district (out of ∼45 health districts) (42). These findings provide evidence in support of programmes to combine VAS with anti‐parasite treatment in combating vitamin A deficiency.

Training materials and programme documents

The Minimum Packet of Nutrition Activities (18) and the Vitamin A Supplementation Implementation Guide (43) promote national distribution of VAS through health centres to children 6–59 months, semi‐annually, and to women early postpartum. Semi‐annual VAS distribution through national health days has also been occurring since at least 2001 (44). The Essential Nutrition Actions (ENA) (15), which presumably replaces the Minimum Packet of Nutrition Activities, does not include details on where VAS would be provided. The ENA and a module for training health workers on micronutrient deficiencies (45), which are both available for national use, clarify that postpartum VAS should occur within 40–45 days. But a number of other documents lack this clarity, indicating simply that VAS should occur early postpartum. The use of vitamin A‐rich foods in the diets of women and young children is promoted in the ENA and the above‐mentioned training module. Smaller scale programs that promote the use of vitamin A‐rich foods are VitA Burkina (46) and the SCPB/HKI community nutrition project (47).

Surveys, monitoring, and evaluation

According to coverage estimates for the 2004–2006 semi‐annual national VAS campaigns 100% of children 6–59 months of age received vitamin A supplements (44). Due to differences in evaluating coverage the 2006 MICS found that just 67% of children 6–59 months had reportedly consumed a VAS within the previous 6 months and 48% of women who had given birth in the previous 2 years had received a VAS within 8 weeks of birth.

We found no national surveys assessing vitamin A status of young children or women, beyond assessment of night blindness. A study in 10 villages, reported from 1999, found that 85% of children 12–36 months of age (n = 315) and 64% of mothers (n = 215) had serum retinol < 0.7 µmol L−1, indicating high rates of vitamin A deficiency in the study population (41). In 2006, researchers found low serum retinol concentrations (<0.7 µmol L−1) among 148 children 2–3 years in another region (40). According to the 2003 DHS (5), 13% of women reported night blindness during their previous pregnancy. Unfortunately, no more recent data are available for comparison. The findings of these surveys indicate that vitamin A deficiency remains a public health concern in Burkina Faso for which continued interventions are required.

The Fortification Rapid Assessment Tool (FRAT) survey conducted in 1999 identified cooking oil as a potential food vehicle for vitamin A fortification. Plans are moving forward to fortify cooking oil with vitamin A nationally 48, 49, and some producers are already doing so voluntarily. Due to low consumption of oil among young children, the fortification of cooking oil with vitamin A is more likely to have an impact on women's than on children's vitamin A status, except through breast milk.

Zinc

National policies, strategies, and plans of action

Reviewed national policies do not yet address the risk of zinc deficiency or its use in the treatment of diarrhoea. Nevertheless, Burkina Faso has recently adopted the World Health Organization/United Nations Children's Fund (WHO/UNICEF) recommendations to include zinc supplements in the treatment of diarrhoea (50).

Formative research

We found no formative programme‐related research on zinc in the treatment of diarrhoea or the prevention of zinc deficiency.

Training materials and programme documents

We also found no national protocols or training manuals promoting the use of zinc in the treatment of diarrhoea. Food sources of zinc are included in the 2001 national training manual on micronutrients for health workers (45). A capacity building programme, conducted in 3 of the ∼45 health districts, was also developed to improve activities to treat acute malnutrition in three Sahelian countries, including Burkina Faso. This project includes a component to train and promote the use of zinc supplements in the treatment of diarrhoea (51).

Surveys, monitoring, and evaluation

In a national survey conducted in 2003, 43.1% of children aged <5 years were stunted (height‐for‐age < −2 SD of the new WHO Child Growth Standards). Similarly, two recent studies in southwestern Burkina Faso found a stunting rate of 44% in children aged 6–72 months in the Dandé health district (52) and 33% aged 6–23 months in the Toussiana district (Wessells et al. unpublished observations). The latter study done in 2009 (53) found that 63% of the children (n = 450) had a plasma zinc concentration below the cut‐off of 65 µg dL−1 (54). Another study completed among children aged 6–31 months in the Nouna district of northwestern Burkina Faso reported serum zinc concentrations in a subsample of 80 children and found that 72% had a concentration < 85 g dL−1 (55). According to these rates of growth stunting and the prevalence of low serum zinc concentrations, the Burkinabé population is considered to be at high risk of zinc deficiency (54).

According to the MICS 2006, packaged oral rehydration solution (ORS) was provided to just 15% of young children who had diarrhoea during the 2 weeks prior to data collection and 8% received home‐preparations of ORS. Because therapeutic zinc supplements are likely to be distributed with ORS in the treatment of diarrhoea, the use of zinc supplements will likely be similar to the use of ORS. Therefore, there is a need to improve national diarrhoea treatment programmes as zinc supplements are introduced in the treatment of diarrhoea.

Iron and anaemia

National policies, strategies, and plans of action

Activities to prevent anaemia, such as the use of insecticide‐treated bed nets (ITN), treatment of helminths and consumption of iron‐folic acid supplements during pregnancy, are promoted in the PNDS (38), the Strategic Plan for Low‐Risk Maternity (56) and the National Nutrition Action Plan (11). The National Nutrition Action Plan (11) also promotes using iron‐folic acid supplements in treating all children with anaemia. This 2001 document does not yet include the recent recommendations to take additional precautions for infection control when iron supplements are provided to young children in regions where infections, such as malaria, are endemic and the iron status of the child is unknown (57).

Formative research

Ouédraogo et al. (58) evaluated the effect of three micronutrient supplements (iron, iron and zinc, or multiple micronutrients provided 5 days/week for 6 months) to 296 children 6–23 months (96–100 per group) with low haemoglobin (70–109 g L−1). In this study children who received the multiple micronutrients were more likely to recover from anaemia than those receiving just iron, indicating a need to evaluate other micronutrients contributing to anaemia in this population. A second study by Ouédraogo et al. (59) found plasmodium falciparum malaria infection among 53% of the 456 rural children surveyed, half of which was afebrile malaria. These two studies identify two possible risk factors that are not necessarily addressed in Burkina Faso's programmes to prevent or treat anaemia: (i) nutritional factors other than iron deficiency; and (ii) afebrile malaria. Additional studies should be considered to better identify the prevalence of anaemia‐related micronutrient deficiencies and, if necessary, how programmes might be expanded to prevent and treat anaemia.

Training materials and programme documents

The methods promoted for the prevention of anaemia and malaria in Burkina Faso include the use of iron‐folic acid supplements during pregnancy and early postpartum 15, 17, 18, 45, 51, 60, 61, use of ITNs against malaria 15, 28, 51, semi‐annual deworming 15, 17, 51, 61, and the promotion of some iron‐rich foods 15, 45, 62. The ENA approach (15), which is intended for use nationally, addresses all of these topics. As mentioned previously, we could only confirm that ENA has been implemented in certain regions.

The FRAT survey mentioned above also identified wheat flour as a food vehicle for iron fortification 48, 49. Some flour producers are voluntarily fortifying wheat flour with iron, zinc, folic acid, and other B vitamins. As with cooking oil, women may consume enough wheat flour to reduce the risk of iron deficiency, but it is unlikely that young children will consume enough wheat flour to have an impact on their iron status. Fortified foods that are targeted at young children may be needed to ensure that children meet their physiological requirement of iron.

Surveys, monitoring, and evaluation

The prevalence of iron deficiency among children or women has not been evaluated in Burkina Faso. In the 2003 DHS (5), 92% children 6–59 months and 54% women 15–49 years had haemoglobin concentrations < 11.0 g dL−1, indicating very high rates of anaemia in these populations. Additional findings reported in this survey are: (i) only about one‐third of children 6–23 months consumed iron‐rich foods the day prior to survey; and (ii) just 17% of women consumed at least 90 days of iron‐folic acid supplements during their previous pregnancy. In the MICS 2006, reportedly 52% of households had bed nets but only 23% of households had ITNs, which provide extra protection against mosquitoes and thus malaria. Therefore, the programmes promoting these practices to prevent anaemia are not yet attaining desired impacts. Further evaluations are needed to identify whether the lack of improvements in anaemia rates is related to inadequate programme implementation, such as neglecting to provide pertinent educational messages regarding methods of preventing anaemia, or whether additional risk factors should also be considered to reduce the prevalence of anaemia.

Iodine

National policies, strategies, and plans of action

The prevention or treatment of iodine deficiency disorders is promoted in three national legislative documents through the promotion and control of iodized salt 10, 11, 38. National legislation enacted in 1995 or 1996 reportedly required salt to be iodized at 150 ppm (63), which is more than adequate to meet the international recommendation to fortify salt at 20–40 ppm iodine during production (64).

Formative research

No studies evaluating iodine status among preschoolers were identified. In 1999 Delange et al. (65) evaluated the prevalence of iodine deficiency in 10 areas of Burkina Faso where the prevalence was high in previous surveys (57% goitre in 1987) and found just 22% goitre. They found that nearly one‐third of salt in households was not adequately iodized to the then recommended 50 ppm, but the average level of iodine in salt was 48 ppm. They found a wide range in the amount of iodine in salt, indicating there is a need for improved monitoring of the level of iodine in salt.

Training materials and programme documents

The prevention of iodine deficiency disorder is addressed through the promotion of iodized salt in the Essential Nutrition Actions (15), which is intended for national promotion, and in other national 18, 45 and sub‐national 62, 66 training materials and programme documents. The 2001 training module for health agents on micronutrients (45) was the only document we identified that recommended using alternatives, such as iodine supplements, in regions where salt iodization is not sufficient to prevent iodine deficiency disorders. If iodine deficiency disorders at present are still prevalent, as was found in 1999, additional interventions might be needed.

Surveys, monitoring, and evaluation

The 2003 DHS reported that iodized salt is only available in about one‐third of households, which is similar to the survey reported by Delange et al. mentioned above (65). These findings indicate that the control of iodized salt in Burkina Faso is not yet achieving the desired goal of >90% of household with access to iodized salt. As recommended by WHO/UNICEF, the lack of adequate coverage of iodized salt, or the lack of impact of salt iodization on preventing iodine deficiency indicates that there is a need to consider additional strategies to prevent and treat iodine deficiency disorders (64).

Summary of findings – prevention and treatment of micronutrient deficiencies

-

•

National policies support activities to prevent vitamin A, iron and iodine deficiencies.

-

•

Nationally promoted activities include: (i) the distribution of VAS to children 6–59 months and early postpartum women through routine health centre visits and national vaccination campaigns; (ii) the promotion of iron‐folic acid supplements during pregnancy, use of bed nets to avoid malaria and regular deworming; and (iii) the promotion of universal salt iodization.

-

•

One regional‐level programme was developed to commence the promotion of use of zinc supplements in the treatment of diarrhoea, but this is not yet promoted nationally. There are no programmes to identify the prevalence of zinc or iron deficiency or to prevent zinc deficiency.

-

•

Research conducted in Burkina Faso contributed to the selection of cooking oil as a carrier for vitamin A fortification. The fortification of cooking oil with vitamin A and of wheat flour with iron, zinc and B vitamins is now voluntary in Burkina Faso.

-

•

Recent surveys indicate that VAS coverage is reaching nearly all children 6–59 months of age (67) and about half of women early postpartum (23). Recent evaluations of the prevalence of vitamin A deficiency are not available, but 13% of women reported night blindness in 2003.

-

•

Anaemia prevalence is very high among young children (92%, DHS 2003) and women in child‐bearing years (54%, DHS 2003), and use of nationally promoted methods of preventing anaemia (ITNs, deworming, iron‐folic acid supplementation during pregnancy) are low. The reasons for lack of adopting these practices have not been evaluated.

-

•

Although a nearly national survey in 1999 reported that the average level of salt iodization was 48 ppm (65), this survey also found low urinary iodine concentrations among nearly half of school children. The 2003 DHS reported that only about one‐third of children < 5 years lived in households with adequately iodized salt (>15 ppm), indicating little change from the earlier study.

Recommendations – prevention and treatment of micronutrient deficiencies

-

•

The current VAS programmes should be evaluated to determine which components have been the most effective at distributing VAS to women early postpartum. The findings should be used to continue to expand this coverage and may also be useful for other countries in the region that report reaching no more than about one‐fourth of women early postpartum with VAS.

-

•

The distribution of vitamin A among infants immediately at 6 months should also be evaluated to determine whether programme changes are needed to reach infants at this critical age.

-

•

Research is needed to evaluate reasons for the low use of ORS in treating diarrhoea. These findings should be used to enhance and expand programmes to treat diarrhoea as therapeutic zinc supplements are introduced.

-

•

Surveys are needed to evaluate the prevalence of zinc deficiency, iron deficiency anaemia and other causes of anaemia in a nationally representative sample of women and young children. These data should then be used in developing and targeting programmes towards vulnerable populations. The findings should also be used to adapt programmes aimed at treating young children with anaemia, by taking into consideration the new international recommendations related to provision of iron supplements to young children (57).

-

•

Research is also needed to identify reasons why vulnerable women and children are not utilizing available methods of preventing anaemia. These findings should be used to develop and/or improve programme activities to prevent anaemia.

-

•

There is a need for up‐to‐date data on the prevalence of iodine deficiency disorders in Burkina Faso to determine whether and where additional interventions are needed, beyond the promotion of iodized salt.

Other nutritional support: management of malnutrition, prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV, food security, and hygiene

Management of malnutrition

National policies, strategies, and plans of action

National policies and strategies promote programmes to prevent and treat acute malnutrition through nutrition rehabilitation centres, health centres, and community outreach 11, 38, 68, 69, 70. Some of these facilities receive assistance from NGOs in addition to governmental agencies 51, 61, 71, 72, 73.

Formative research

In an effort to identify beliefs and knowledge regarding malnutrition and food security, two NGOs conducted community‐based focus groups in one to six villages of six provinces (74) (sample sizes of 10–15 participants per village). They discovered that participants understood correctly that malnutrition could be linked to insufficient food or food diversity, improper hand‐washing prior to preparing food and/or improper handling of foods. However, they also believed, incorrectly, that malnutrition could be caused by high ambient temperatures that cause breast milk to over‐heat and make the infant sick. Respondents also identified some characteristics of children with malnutrition, such as lethargy, but did not identify growth monitoring as a method of identifying growth faltering before it progresses to malnutrition. These findings may be useful in the development of educational messages.

Two food supplements used in treating malnutrition in Burkina Faso include Spiruline or Spirulina, an algae that contains some amino acids, iron, carotenoids, and possibly fatty acids, and Misola, a mix of millet, soy, peanuts, and sugar. Researchers who evaluated the impact of adding these products to traditional diets used in treating malnutrition reported that there was no advantage of adding either Spiruline or Misola to the traditional diet 75, 76, but the combination appeared to be beneficial (76). However, statistical analyses compared each feeding group to baseline, rather than comparing the changes across feeding groups and the traditional diets provided in addition to these two products were not comparable with the fortified foods recommended by the Ministry of Health for the treatment of acute malnutrition, foods such as F75, F100 and Plumpynut (77). Therefore, it is not clear whether there is any value added in promoting these products.

Training materials and programme protocols

The national Protocols for the Management of Acute Malnutrition (77), provide guidance for diagnosing and treating acute malnutrition. The cut offs for screening acute malnutrition are <110 mm mid‐upper arm circumference (MUAC) or bilateral oedema for severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and 110–125 mm for moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) (without bilateral oedema). Those screened with SAM are referred directly to a health centre or rehabilitation centre that cares for SAM, and those with MAM are referred to a health centre. At health centres and nutrition rehabilitation centres, children with confirmed MUAC between 110–124 mm or with weight‐for‐height between 70 and 79% of the median value of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reference are referred for treatment of MAM. Children with MUAC < 110 mm (among children ≥ 65 cm in length), weight‐for‐height < 70% of the median or bilateral oedema are referred to the nutrition rehabilitation centre for treatment of SAM. These cut offs do not yet reflect the new recommendations to screen for SAM with MUAC < 115 or weight‐for‐height z‐score < −3, according to the new WHO children's growth reference standards. Reports from UNICEF representatives in Burkina Faso indicate that these changes are currently being implemented and evaluated.

The Burkina Faso Red Cross developed a series of potentially useful training guides for the screening and treatment of malnutrition 61, 71, 72. These guidelines include: (i) visual aids explaining how to conduct anthropometric measurements and assess whether oedema is present in screening and diagnosing malnutrition (72); (ii) guidelines for the amount of supplemental food to provide according to the child's weight when treating malnutrition, and when to refer malnourished children to the hospital or nutrition rehabilitation centre (61); and (iii) village nutrition committee activities to screen for malnutrition (71). The visual aids provided in the manual for malnutrition screening (72) are useful for training, but the figure depicting the head position of the recumbent child is misplaced, tilted out of the desired plane. Measurements taken with the child's head in this position could lead to inaccurate assessments of the child's nutritional status and thus errors in growth monitoring. The correct figures are found in English and French versions of the original reference online (78).

Programmes

Nutritional rehabilitation and education centres in Burkina Faso provide intensive inpatient (Centre de Récupération Nutritionnelle Intensive ) and ambulatory (Centre de Récupération Nutritionnelle Ambulatoire) care to children and women with acute malnutrition. Community‐based therapeutic care (CTC) is also available through which supplementary foods are provided for use outside these centres. We did not find documentation of the actual coverage of these programmes, but the National Nutrition Policy (70) highlighted the lack of functioning malnutrition rehabilitation centres and inadequate financial and technical capacities of health centres to cover the corresponding void. Nine identified nutrition programmes for young children included a component for screening and referral of acutely malnourished young children (79). However, it is not clear whether human and institutional capacities are adequate to treat these children once referred.

Surveys, monitoring, and evaluation

As demonstrated in the introduction, there has been little change in the prevalence of malnutrition in Burkina Faso since 1990. To provide continuity across time, the most recent surveys assessing anthropometric measures 36, 80 provide data using both the old NCHS growth reference data and the currently recommended WHO growth standards. According to contacts at UNICEF, Burkina Faso is moving towards using the new WHO growth standards for evaluating nutritional status, but the impact on programmes, capacities and outcomes have not yet been evaluated.

Savadogo et al. (81) evaluated the management of severe malnutrition among 1322 children in one urban nutrition rehabilitation centre between 1999 and 2003. Key findings were the need for continued support, both for the capacity of the rehabilitation centre to appropriately manage severe malnutrition and for the participant once discharged into the community, to prevent relapse.

The Axios programme provided assistance to malnutrition recuperation centres, including support for decentralized nutrition centres, nutrition demonstrations and support for school lunches and school garden development (73). The authors evaluated knowledge of breastfeeding, complementary feeding and micronutrients in one health district and found better understanding among residents of the intervention sites compared with non‐intervention sites. However, this additional knowledge was not linked to participation in the nutrition demonstrations. This indicates that non‐participants may have heard of the educational messages through means not directly related to the intervention. However, because there was no baseline study, they could not confirm whether any differences between sites were due to the intervention. More rigorous evaluations are needed to confirm whether programmes such as this are effective at disseminating messages aimed at reducing malnutrition and whether there is any impact on rates of malnutrition in intervention areas.

Summary of findings – management of acute malnutrition

-

•

Children with acute malnutrition are treated through government and NGO supported ambulatory‐ and in‐patient nutrition rehabilitation centres and through CTC. However, the coverage is reportedly insufficient to reach all malnourished children.

-

•

The current MUAC cut off used to screen for malnutrition is 110 mm, which is lower than the recently updated recommendation of 115 mm. The growth standards for use in diagnosing children with low weight‐for‐height are in the process of changing from the NCHS reference to the new WHO child growth standards. Available evaluations of the quality of care provided at nutrition rehabilitation centres and health centres indicate there is a need for institutional and human capacity building to improve the care provided and to extend care into the community following discharge.

Recommendations – Management of acute malnutrition

-

•