Abstract

Research tools that are comparable across ethnic groups are needed in order to understand sociodemographic disparities in breastfeeding rates. The Infant Feeding Intentions (IFI) scale provides a quantitative measure of maternal breastfeeding intentions. IFI score ranges from 0 (no intention to breastfeed) to 16 (very strong intentions to fully breastfeed for 6 months). The objective of this study was to examine intra‐ and inter‐ethnic validity of the IFI scale. The IFI scale was administered to 218 white non‐Hispanic, 75 African‐American, 80 English‐speaking Hispanic, 62 Spanish‐speaking Hispanic and 64 Asian expectant primiparae. Participants were asked their planned duration of providing breast milk as the sole source of milk (full breastfeeding). The IFI scale was examined for intra‐ethnic internal consistency and construct validity and for inter‐ethnic comparability. For all five ethnic categories, principal component analysis separated the scale into the same two factors: intention to initiate breastfeeding and intention to continue full breastfeeding. Across ethnic categories, the range in Cronbach's alpha was 0.70–0.85 for the initiation factor and 0.90–0.93 for the continuation factor. Within each ethnic category, IFI score increased as planned duration of full breastfeeding increased (P < 0.0001 for all). Within the planned duration categories of <1, 1–3, 3–6 and ≥6 months, the median IFI score by ethnic category ranged from (low–high) 5–8, 9–10, 12–14 and 16–16, respectively. The IFI scale provides a valid measure of breastfeeding intentions in diverse populations of English‐ and Spanish‐speaking primiparae, and may be a useful tool when researching disparities in breastfeeding practices.

Keywords: breastfeeding practices, lactation, African‐American, Hispanic, assessment tools, health disparities

Introduction

Within the United States, large disparities exist in breastfeeding rates by ethnic and economic group (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2007). In conducting research addressing these disparities, it is important to use assessment tools with etic constructs, (i.e. comparable across ethnic groups) (Warnecke et al. 1997). The Infant Feeding Intentions (IFI) scale was developed to provide a quantitative measure of maternal breastfeeding intentions (Nommsen‐Rivers & Dewey 2009). The IFI scale was initially validated in a multi‐ethnic sample of low‐income primiparae (n = 170) interviewed within the first 24 h post‐partum and followed to 6 months post‐partum. In this sample, the IFI scale showed strong internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha coefficient = 0.90). Construct and criterion validity were demonstrated by significant associations between IFI score and both planned and actual exclusive breastfeeding duration (P < 0.0001 for both analyses). However, the initial validation was not without limitations. Even though the sample was multi‐ethnic, the sample size within each ethnic group was not large enough to examine intra‐ethnic validity or inter‐ethnic comparability of the IFI scale. Furthermore, only 16 study participants completed the Spanish version of the scale. The aim of this study was to examine the intra‐ethnic group construct validity and between‐ethnic group comparability of the IFI scale in a multi‐ethnic, threefold larger sample of English‐ and Spanish‐speaking primiparae.

Key messages

-

•

Valid research tools are needed to better understand socio‐economic disparities in breastfeeding practices in the United States.

-

•

The Infant Feeding Intentions Scale is a simple tool for quantitative assessment of maternal breastfeeding intentions.

-

•

Construct validity of the scale was demonstrated both within and across multiple ethnic groups, including African‐American, Hispanic and non‐Hispanic white women.

-

•

The scale is available in English and Spanish.

Methods

Sample

Study participants were recruited as part of a longitudinal cohort study examining barriers to early lactation success in a multi‐ethnic population. All expectant primiparous women receiving prenatal care at a University of California Davis Medical Center (UCDMC) clinic (Sacramento, California) between January 2006 and December 2007 were screened for study eligibility. Selection criteria were: expecting first live‐born infant (primiparous), between 32–40 weeks gestation at time of interview, single foetus, speaks either English or Spanish and ZIP code in catchment area (8‐mile radius of the medical centre). Exclusion criteria were: referred to the UCDMC due to medical condition (high‐risk referral), known absolute contraindication to breastfeeding, or less than 19 years old and not able to obtain parental consent. The study protocol and consent form were approved by the University of California Davis Institutional Review Board.

Instruments and data collection

After obtaining informed consent, study participants were interviewed in person at a prenatal clinic visit. In addition to the IFI scale, data were collected regarding ethnicity (self‐identified), education level, age, health insurance status, breastfeeding initiation plans and infant age at which they are planning to introduce formula or other milks (if planning to breastfeed). Item numbers one and two of the IFI scale probe the strength of intentions to initiate breastfeeding and subsequent items assess strength of intentions to provide breast milk as the sole source of milk to 1, 3 or 6 months (see Table 2). The response to each statement is scored from 0 (very much disagree) to 4 (very much agree), except for item 1, which is reverse scored (thus, a response of ‘very much agree’ with the item 1 statement, ‘I am planning to only formula feed my baby . . .’ receives a score of 0). Total IFI score is calculated by averaging the score for the first two items and summing this average with the scores for items 3–5. Possible score thus ranges from 0 to 16, with 0 representing a very strong intention to not breastfeed at all and 16 representing a very strong intention to fully breastfeed to 6 months of age (Nommsen‐Rivers & Dewey 2009).

Table 2.

Infant Feeding Intentions scale principal component analysis and Cronbach's alpha results by ethnic category

| Ethnic category | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian | English‐speaking Hispanic | Spanish‐speaking Hispanic | African‐American | White, non‐Hispanic | Total sample | |

| Sample size | 64 | 80 | 62 | 75 | 218 | 532 |

| Breastfeeding initiation factor* | ||||||

| Cronbach's coefficient alpha (standardized) | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.81 |

| Factor items | Varimax normalized factor loadings | |||||

| 1. I am planning to only formula feed my baby (I will not breastfeed at all) | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.73 |

| 2. I am planning to at least give breastfeeding a try | 0.77 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.73 |

| Breastfeeding duration factor* | ||||||

| Cronbach's coefficient alpha (standardized) | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| Factor items | Varimax normalized factor loadings | |||||

| 3. When my baby is 1 month old, I will be breastfeeding without using any formula or other milk | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.84 | 0.64 | 0.80 | 0.73 |

| 4. When my baby is 3 months old, I will be breastfeeding without using any formula or other milk | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| 5. When my baby is 6 months old, I will be breastfeeding without using any formula or other milk | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.83 |

Based on principal component analysis, the five‐item scale had a two‐factor solution.

Data analysis

Self‐identified ethnicities were collapsed into five broad categories: African‐American, Asian, English‐speaking Hispanic, Spanish‐speaking Hispanic and white non‐Hispanic. Study participants self‐identifying with more than one of the above ethnic categories were categorized as ‘mixed ethnicity’ and were not included in the inter‐ or intra‐ ethnic validity analyses (but were included in overall summary measures). Most Hispanic participants were bilingual to some extent. The interview was conducted in the language the participant was most comfortable with, and this was the basis for classification as English‐speaking or Spanish‐speaking Hispanic.

Intra‐ethnic IFI scale validity was assessed using two measures of internal consistency and one measure of construct validity within each ethnic category. First, within each ethnic category, factor analysis was used to confirm the existence of two dimensions within the IFI: (1) strength of intention to initiate breastfeeding (items 1 and 2), and (2) strength of intention to continue full breastfeeding (items 3, 4 and 5). Principal component analysis with a varimax rotation was used to examine the factor solutions. Second, within each ethnic category, Cronbach's coefficient alpha value was calculated for each dimension, which represents the proportion of a scale's total variance that is attributable to a common source.

Intra‐ethnic construct validity was examined by comparing IFI scores across categories of planned duration of full breastfeeding, defined here as planned duration of providing breast milk as the sole source of milk (<1 month, 1 month to <3 months, 3 months to <6 months or >= 6 months) within each ethnic category. As the distributions of IFI scores tended to be left‐skewed, non‐parametric summary measures (median, inter‐quartile range) and statistical tests (mean rank sum scores) were used to examine IFI scores within and between ethnic and planned duration of full breastfeeding categories. Within each ethnic category, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to determine if rank sum mean scores differed significantly by planned duration of full breastfeeding category. A significant increase in average rank sum scores as planned duration of full breastfeeding increases is indicative of construct validity within each ethnic category.

To examine the comparability of the IFI scale across ethnic groups (inter‐ethnic validity) the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to determine if rank sum mean scores differed significantly by ethnic group within each planned duration of full breastfeeding category. Non‐significance in the ranking of scores between ethnic categories within each category of planned duration of full breastfeeding is indicative of scale comparability across ethnic groups.

All data analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.1 (2002–2003, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Sample characteristics

Over the 24 months of study enrolment, 768 of those screened met the eligibility criteria and 532 of these women agreed to the prenatal interview (69% of those eligible). Reasons for refusal were: too busy, 51%; not interested, 25%; study too intrusive, 18%; doesn't want to be interviewed about breastfeeding, 3%; and miscellaneous, 2%.

Characteristics of study participants by ethnic category are shown in Table 1. The cohort consisted of 64 Asian women (birthplace: United States, n = 24; south east Asia, n = 13; India/Pakistan/Sri Lanka, n = 10; China, n = 7; Pacific islands, n = 6; other, n = 4), 80 English‐speaking Hispanic women (birthplace: United States, n = 72; Mexico, n = 6; Spain, n = 1; Peru, n = 1), 62 Spanish‐speaking Hispanic women (birthplace: Mexico, n = 57; Central America, n = 4; United States, n = 1), 75 African‐American women, 218 white, non‐Hispanic women and 33 women who self‐identified with more than one of the above ethnic groups. Maternal age ranged from 16 to 41 years old (median age = 26 years). Overall, 40% of study participants had a high school education or less. The proportion of study participants who did not have private health insurance or were enrolled in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children was 49% and 44%, respectively. The proportion of study participants planning to provide human milk as the sole source of milk was as follows: 9% for <1 month, 9% for 1 to <3 months, 15% for 3 to <6 months and 67% for 6 months or more.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants (n = 532)

| Self‐identified ethnicity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian | Hispanic, English | Hispanic, Spanish | African‐American | Mixed ethnicity | White, non‐Hispanic | Overall | |

| Sample size* | 64 (12) | 80 (15) | 62 (12) | 75 (14) | 33 (6) | 218 (41) | 532 (100) |

| Education † | |||||||

| High school or less | 14 (22) | 42 (53) | 51 (82) | 52 (69) | 18 (55) | 37 (17) | 214 (40) |

| Some college | 50 (78) | 38 (48) | 11 (18) | 23 (31) | 15 (45) | 181 (83) | 318 (60) |

| Health Insurance status † | |||||||

| Public | 25 (40) | 46 (58) | 59 (95) | 62 (83) | 16 (52) | 53 (24) | 261 (49) |

| Private | 38 (60) | 34 (43) | 3 (5) | 13 (17) | 15 (48) | 164 (76) | 267 (51) |

| Maternal age † | |||||||

| ≤25 years | 18 (28) | 53 (66) | 48 (77) | 63 (84) | 20 (60) | 56 (26) | 258 (49) |

| >25 years | 46 (72) | 27 (34) | 14 (23) | 12 (16) | 13 (39) | 162 (74) | 274 (51) |

| Planned full breastfeeding months † | |||||||

| <1 | 4 (6) | 6 (8) | 12 (19) | 12 (16) | 6 (18) | 9 (4) | 49 (9) |

| 1–<3 | 8 (13) | 9 (11) | 4 (6) | 13 (18) | 1 (3) | 11 (5) | 46 (9) |

| 3–<6 | 6 (9) | 13 (16) | 11 (18) | 13 (18) | 3 (9) | 32 (15) | 78 (15) |

| 6 or more | 46 (72) | 51 (65) | 35 (56) | 35 (48) | 23 (70) | 165 (76) | 355 (67) |

Number (%) of total sample (i.e. across the row).

† Number (%) within ethnic category (i.e. down the column).

Intra‐ethnic internal consistency

Intra‐ethnic factor analysis results are shown in Table 2. For all five ethnic categories, the IFI scale items separated cleanly into two factors: one representing breastfeeding initiation intentions (items 1 and 2, varimax rotated factor loadings ranging from 0.63 to 0.80 across ethnic categories), and the other representing full breastfeeding continuation intentions (items 3, 4 and 5, varimax rotated factor loadings ranging from 0.64 to 0.94 across ethnic categories).

Cronbach's coefficient alpha values for each factor are also shown in Table 2. For the breastfeeding initiation factor, coefficient alpha values were somewhat lower in the English‐speaking Hispanic (0.70) and Spanish‐speaking Hispanic ethnic categories (0.75) as compared to the other ethnic categories (range, 0.81–0.85). For the breastfeeding continuation factor, coefficient alpha values were uniformly high (range, 0.90–0.93 across ethnic categories). It was not possible to examine item‐total correlations within the breastfeeding initiation factor (>2 items needed). However, within the breastfeeding continuation factor, all three items contributed positively to the coefficient alpha value in all five ethnic categories.

Intra‐ethnic construct validity

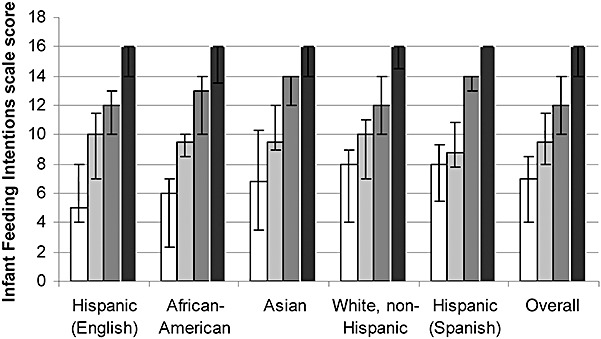

As shown in Fig. 1, for all five ethnic categories median IFI scores increased as planned duration of full breastfeeding increased (Kruskal–Wallis mean rank sum analysis, P < 0.0001 for all analyses). Similarly, within both income groups (public and private health insurance) and within both education groups (less than a college education and at least some college), median IFI scores increased as planned duration of full breastfeeding increased (Kruskal–Wallis mean rank sum analysis, P < 0.0001 for all analyses, data not shown).

Figure 1.

Intra‐ethnic and inter‐ethnic comparison of median Infant Feeding Intentions scale scores by planned full breastfeeding duration category (in months): □ <1 month;  1 to <3 months;

1 to <3 months;  3 to <6 months;

3 to <6 months;  6 months or more; upper and lower bars represent the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively (within the Spanish‐speaking Hispanic ethnic category, upper and lower bars do not appear for the highest category because the median score = 75th percentile = 25th percentile). Total possible score ranges from 0 to 16. Within ethnic category Kruskal‐Wallis test of equivalence of rank sum scores stratified by planned full breastfeeding duration category (intra‐ethnic construct validity): P < 0.0001 for all 5 ethnic categories. Within planned full breastfeeding duration category Kruskal‐Wallis test of equivalence of rank sum scores stratified by ethnic category (inter‐ethnic comparability) chi‐square and P‐values: 5.3 and 0.26; 0.8 and 0.94; 6.8 and 0.15; 11.5 and 0.02; for full breastfeeding duration categories of <1 month, 1 to <3 months, 3 to <6 months, and 6 months or more, respectively.

6 months or more; upper and lower bars represent the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively (within the Spanish‐speaking Hispanic ethnic category, upper and lower bars do not appear for the highest category because the median score = 75th percentile = 25th percentile). Total possible score ranges from 0 to 16. Within ethnic category Kruskal‐Wallis test of equivalence of rank sum scores stratified by planned full breastfeeding duration category (intra‐ethnic construct validity): P < 0.0001 for all 5 ethnic categories. Within planned full breastfeeding duration category Kruskal‐Wallis test of equivalence of rank sum scores stratified by ethnic category (inter‐ethnic comparability) chi‐square and P‐values: 5.3 and 0.26; 0.8 and 0.94; 6.8 and 0.15; 11.5 and 0.02; for full breastfeeding duration categories of <1 month, 1 to <3 months, 3 to <6 months, and 6 months or more, respectively.

Inter‐ethnic comparability

IFI scores were compared across the five ethnic categories within each of the four planned full breastfeeding categories. The range (lowest median score – highest median score) of median values across the ethnic categories was 5.0–8.0, 8.8–10.0, 12.0–14.0, and 16.0–16.0, within the planned full breastfeeding categories of <1 month, 1 month to <3 months, 3 months to <6 months, and ≥6 months, respectively (Fig. 1). Even though all five ethnic categories had the same median IFI score (16.0) within the highest planned full breastfeeding category (≥6 months), the chi‐squared value of 11.5 for the Kruskal–Wallis test was statistically significant (P < 0.02). Mean rank sum scores for Spanish‐speaking Hispanic women within this full breastfeeding category suggest that they had an IFI score of 16 more often than the other ethnic categories (mean rank sum score 32% higher than for the other ethnic categories, data not shown). This result is consistent with this sub‐group's longer planned duration of full breastfeeding (mean ± standard deviation): 10.3 ± 3.6 vs. 9.4 ± 3.3 months in the Spanish‐speaking Hispanic category vs. all other ethnic categories combined. There was no significant difference in median IFI scores within each of the four planned full breastfeeding duration categories when compared between income (public vs. private insurance) or education (no college vs. college) groups (data not shown).

Discussion

These findings support the validity of the IFI scale for measuring the strength of maternal breastfeeding intentions across the English‐ and Spanish‐speaking ethnic groups in our sample. The scale demonstrated internal consistency, intra‐ethnic group construct validity and between ethnic group comparability. The ‘gold standard’ for intention against which the scale was validated was maternal report of planned duration of providing breast milk as the sole source of milk. Although there is no known gold standard measure of breastfeeding intentions and maternal report is the best measure of intention currently available, we acknowledge this as a theoretical limitation of the study, as it may be an imperfect measure.

The IFI scale arose out of an identified need for a tool that provides a quantitative measure incorporating both intentions regarding duration of breastfeeding and the strength of those intentions (Nommsen‐Rivers & Dewey 2009). Such a tool is particularly relevant at this time in the United States as the overall rate of breastfeeding initiation is close to meeting the Healthy People 2010 goal, but the percentage of those who continue to exclusively breastfeed to 6 months remains far below the 2010 goal of 25% (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2007). While previous assessment tools have provided insights into maternal breastfeeding intentions, they often are not suitable for current research needs. Earlier tools either focused solely on breastfeeding initiation intentions (Manstead et al. 1984; Wambach 1997; Kloeblen et al. 1999), or were based on a breastfeeding duration intention model (Humphreys et al. 1998) that was neither quantitative nor reflective of current infant feeding recommendations (World Health Organization 2003; American Academy of Pediatrics 2005). Furthermore, none of the previous assessment tools has been validated in a multi‐ethnic sample.

In a multi‐cultural society such as the United States, an important component of questionnaire quality is assuring that the questions will be commonly understood across all cultural groups, otherwise known as having an etic construct (Warnecke et al. 1997). Thus, when seeking to understand disparities in breastfeeding success across cultural groups, an initial key step is confirming that the tool used to assess breastfeeding intentions indeed has an etic construct. For this reason, both the inter‐ and intra‐ethnic validity of the IFI scale were examined. IFI scale score will be a key variable in our forthcoming analysis of barriers to lactation success in a multi‐ethnic population.

The IFI scale demonstrated good internal consistency. Within each of the five ethnic categories, factor analysis revealed the same two‐factor solution as initially hypothesized: ‘intention to initiate breastfeeding’ and ‘intention to continue full breastfeeding’. For the ‘intention to continue full breastfeeding’ factor, Cronbach's alpha coefficients for all ethnic categories were in the ‘excellent’ range (Bland & Altman 1997). However, results were somewhat less robust for the ‘intention to initiate breastfeeding’ factor. Cronbach's alpha coefficient values for the two Hispanic categories (English‐speaking and Spanish‐speaking, values of 0.70 and 0.75, respectively) were somewhat lower than for the other ethnic categories, which had alpha values ranging from 0.81 to 0.85. It is possible that item number two, which reads, ‘I plan to at least give breastfeeding a try’ may be difficult for some women to interpret, particularly those from Hispanic cultures. Based on subjective feedback from the prenatal interview team for the current study, item number two was occasionally misunderstood as meaning ‘I will do no more than give breastfeeding a try’, and thus, some women who had strong breastfeeding intentions may have felt reluctant to respond ‘strongly agree’ to this item. In the initial pilot testing and development of the IFI scale, there was some evidence that inclusion of item number two slightly lowered the Cronbach's alpha coefficient (Nommsen‐Rivers & Dewey 2009). It is possible that rewording item number two to read ‘I plan to breastfeed my baby’ will improve the intra‐ethnic comparability of this item and its contribution to the overall scale. Further cognitive assessment testing is warranted regarding this item. However, it is important to note that Cronbach's coefficient alpha values are lower when there are fewer items in the subscale (Streiner & Norman 2003) and the conventional cut‐off for ‘satisfactory’ internal consistency is an alpha coefficient of 0.70 (Bland & Altman 1997; Streiner & Norman 2003). Therefore, although the values for Hispanic women were somewhat lower than for the other ethnic categories, the internal consistency measures were still within the ‘satisfactory’ range despite being based on only two items.

As a measure of intra‐ethnic construct validity, the Kruskal–Wallis test of rank sum scores was used to examine differences in IFI scores by planned full breastfeeding duration category. Despite some small cell sizes, this statistical test was highly significant (P < 0.0001) within every ethnic category. With the non‐parametric Kruskal–Wallis test, it is possible to have a statistically significant result with just one stratum being significantly different from the other categories. However, examination of the rank sum scores revealed that in every ethnic category, the mean rank sum score markedly increased with each one‐category increase in planned full breastfeeding duration (data not shown). This observation is supported by the data in the Fig. 1, which clearly show a steady increase in median IFI scores, with little overlap in the inter‐quartile ranges, as planned duration of full breastfeeding increases. A similar pattern was observed when data were stratified by income or education level.

The Fig. 1 also illustrates IFI scale comparability across ethnic groups. To demonstrate comparability, IFI scores should be similar across ethnic groups within a given category of planned full breastfeeding duration. There was no statistically significant difference in IFI scores across ethnic groups within any of the planned full breastfeeding duration categories with the exception of the last category (≥6 months, P = 0.02). However, this statistical finding has little practical relevance, as the median IFI scores were identical and consistent with planning to fully breastfeed for at least 6 months (equal to the maximum IFI score of 16) across all five ethnic groups. There was no difference in IFI scores within each planned breastfeeding duration category when compared by income or education level.

Conclusion

In summary, these analyses support the intra‐ethnic consistency and inter‐ethnic comparability of the IFI scale. The IFI scale can provide researchers and policy analysts with a quantitative measure of infant feeding intentions that is comparable across multi‐ethnic and bilingual (English and Spanish) populations in the United States.

Source of funding

This research was supported by grant R40 MC 04294 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (Title V, Social Security Act), Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services.

Conflicts of interest statement

No conflicts of interest have been declared.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the study participants and thank the University of California Davis Medical Center prenatal clinic staff for their cooperation. We also acknowledge the skilful and dedicated assistance of the prenatal team leaders (Leslie Lane, Zeina Maalouf, Barbora Rejmanek and Bineti Vitta,) and the 22 undergraduate student interviewers comprising the prenatal interview team.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics (2005) Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 115, 496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland J.M. & Altman D.G. (1997) Cronbach's alpha. BMJ 314, 572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2007) Breastfeeding trends and updated National Health Objectives for Exclusive Breastfeeding – United States, birth years 2000–2004. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 56, 760–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys A.S., Thompson N.J. & Miner K.R. (1998) Assessment of breastfeeding intention using the transtheoretical model and the theory of reasoned action. Health Education Research 13, 331–341. [Google Scholar]

- Kloeblen A.S., Thompson N.J. & Miner K.R. (1999) Predicting breast‐feeding intention among low‐income pregnant women: a comparison of two theoretical models. Health Education & Behavior 26, 675–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manstead A.S.R., Plevin C.E. & Smart J.L. (1984) Predicting mothers choice of infant feeding method. British Journal of Social Psychology 23, 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nommsen‐Rivers L.A. & Dewey K.G. (2009) Development and validation of the infant feeding intentions scale. Maternal and Child Health Journal 13, 334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streiner D.L. & Norman G.R. (2003) Health Measurement Scales, A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use, 3rd, edn. Oxford University Press: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Wambach K. (1997) Breastfeeding intention and outcome: a test of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Research in Nursing & Health 20, 51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnecke R.B., Johnson T.P., Chavez N., Sudman S., O'Rourke D.P., Lacey L. et al. (1997) Improving question wording in surveys of culturally diverse populations. Annals of Epidemiology 7, 334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2003) Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]