Abstract

Vicarious experience gained through seeing women breastfeed may influence infant feeding decisions and self‐efficacy. Our aim was to measure the attributes of seeing breastfeeding and to investigate how these relate to feeding intention (primary outcome) and behaviour (secondary outcome). First, we developed a Seeing Breastfeeding Scale (SBS), which consisted of five attitudes (Cronbach's alpha of 0.86) to most recently observed breastfeeding: ‘I felt embarrassed’; ‘I felt uncomfortable’; ‘I did not know where to look’; and ‘It was lovely’ and ‘It didn't bother me’. Test–retest reliability showed agreement (with one exception, kappas ranged from 0.36 to 0.71). Second, we conducted a longitudinal survey of 418 consecutive pregnant women in rural Scotland. We selected the 259 women who had never breastfed before for further analysis. Following multiple adjustments, women who agreed that ‘It was lovely to see her breastfeed’ were more than six times more likely to intend to breastfeed compared with women who disagreed with the statement [odds ratio (OR) 6.72, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.85–15.82]. Women who completed their full‐time education aged 17 (OR 3.09, 95% CI 1.41–6.77) or aged 19 (OR 7.41 95% CI 2.51–21.94) were more likely to initiate breastfeeding. Women who reported seeing breastfeeding within the preceding 12 months were significantly more likely to agree with the statement ‘It was lovely to see her breastfeed’ (P = 0.02). Positive attitudes to recently seen breastfeeding are more important determinants of feeding intention than age of first seeing breastfeeding, the relationship to the person seen and seeing breastfeeding in the media.

Keywords: breastfeeding, behaviour, attitudes, vicarious experience, measures, psychosocial determinants

Introduction

The short‐term and long‐term health benefits for both the baby and the mother in developed countries are well documented (Horta et al. 2007; Ip et al. 2007), and UK governments are keen to improve breastfeeding rates. The UK continues to have one of the lowest breastfeeding rates in Europe (Renfrew et al. 2005). In Scotland in 2005, 70% of women initiated breastfeeding, however, the same study shows that only 44% of women breastfeed (exclusive or mixed breast and formula) at 6 weeks (Bolling et al. 2007). Understanding which factors influence pregnant women when they decide how to feed their babies is important for the design and delivery of effective interventions to improve breastfeeding rates. Multifaceted interventions are often more effective at increasing breastfeeding initiation and duration (Dyson et al. 2005; Renfrew et al. 2005). However, identifying which individual components are effective remains a challenge, and the overall quality of evidence is poor (Renfrew et al. 2007).

The psychosocial determinants of breastfeeding intention and behaviour are complex and antenatal breastfeeding intention and actual behaviour are highly correlated (Chambers & Mcinnes 2006). Older maternal age, higher educational level, previous breastfeeding experience and whether the woman herself was breastfed as a baby have been shown to be positively associated with initiating breastfeeding (Bolling et al. 2007). Several studies report that women often decide how they will feed their baby before conception or early in their pregnancy (Chambers & Mcinnes 2006).

Surveys have reported an association between seeing breastfeeding and more positive attitudes towards breastfeeding (Fitzpatrick et al. 1994; Connolley et al. 1998; Dewan et al. 2002; Greene et al. 2003). However, none have examined in detail the characteristics and context of seeing breastfeeding and how this relates to feeding intention and actual behaviour. A survey comparing 100 consecutive breastfeeding mothers with 100 consecutive bottle‐feeding mothers at hospital discharge in Ireland found that breastfeeding mothers were significantly more likely to have seen breastfeeding (P < 0.01) (Fitzpatrick et al. 1994). Another survey investigating attitudes of 419 teenagers in Northern Ireland found an association between having seen breastfeeding and intention to breastfeed, and more positive attitudes to breastfeeding in public (Greene et al. 2003). Higher social classes are more likely to report having seen breastfeeding (Connolley et al. 1998) and teenagers are less like to have seen breastfeeding (Dewan et al. 2002).

Theoretical models and tools applied to investigating breastfeeding attitudes and their translation into breastfeeding intention and actual behaviour include the Theory of Planned Behaviour, which was used to develop the Breastfeeding Attrition and Prediction Tool (Janke 1994), and the Social Cognitive Theory that includes the concepts of social modelling and self‐efficacy (Bandura 1977), which was used to develop the Breastfeeding Self‐Efficacy Scale (Dennis 2003). Bandura's self‐efficacy concept informs the design of the current study. Bandura describes four information sources that influence behaviour: previous experience of the behaviour; vicarious experience with observing others performing the behaviour; verbal persuasion; and physiological responses to anticipating the behaviour or experiencing it.

In this study, we focus on pregnant women's vicarious experience of directly seeing other women breastfeed and indirectly seeing breastfeeding on television or video. The aim of this study was to investigate how attributes of seeing breastfeeding relate to feeding intention and behaviour.

Background

This study formed part of a programme of research to design a complex intervention with the aim of improving breastfeeding rates in Scotland. It builds on an earlier qualitative study of primigravida women, which investigated infant feeding decision making and hypothesized that seeing breastfeeding could influence breastfeeding initiation both positively and negatively depending on the context (Hoddinott & Pill 1999). That study of early school leaving pregnant women, who were followed up 6 weeks after birth, found that women who had seen successful breastfeeding regularly and perceived this as a positive experience were more likely to initiate breastfeeding. In contrast, women who saw breastfeeding infrequently, particularly if it was indiscrete or in a public place, could find it off‐putting. A systematic review of the literature of maternal breastfeeding knowledge, attitudes, confidence or self‐efficacy and/or satisfaction failed to identify any measures of the attributes of seeing breastfeeding (Chalmers et al. 2007). We therefore set out to identify the key attributes of seeing breastfeeding and to design and validate a new scale.

Methods

Participants and setting

The study took place in a rural primary care organization in North East Scotland in 2001–2002, when 33% of babies were receiving some breast milk at 6–8 weeks compared with the Scottish average of 36% (Hoddinott et al. 2006). It formed part of a breastfeeding coaching intervention study (Hoddinott et al. 2006), which used participatory action research methods and was publicized in local newspapers. An information pack was given to women prior to antenatal booking. Midwives provided further verbal information to women at antenatal booking consultations in the local maternity unit or the general practice, obtained signed consent and completed the questionnaire with women. The questionnaires were administered to a cohort of 418 women from 484 eligible women referred by 57 general practitioners working in 14 practices in a consecutive 10‐month period in 2001–2002.

Development of the SBS 1

Qualitative interview data (recorded interviews and complete transcripts) from an earlier study (Hoddinott & Pill 1999), which asked pregnant women prior to antenatal booking about their experiences seeing breastfeeding, were examined. Codes for all text relating to seeing other women breastfeed, either directly in person or indirectly through the media, were analysed. This informed the development of a new questionnaire consisting of five components:

-

1

Age of first seeing breastfeeding (years)

-

2

Frequency of seeing (never, once, a few times, regularly)

-

3

If seen, how recently was breastfeeding last seen (months)

-

4

Relationship to the person seen breastfeeding

-

5

Attitudes towards most recently seen breastfeeding

The last item, ‘attitudes to most recently seen breastfeeding’, consisted of a 15‐item subscale derived using actual quotations from the qualitative interviews (Hoddinott & Pill 1999).

We designed the questionnaire to be administered by a midwife or health visitor. It was assessed for face and content validity by three experts in breastfeeding research and a steering group consisting of four midwives, four health visitors, a nurse manager, a health promotion specialist and a voluntary breastfeeding organization representative. We used ‘think aloud’ techniques (Collins 2003) with 10 women to pilot the questionnaire. The first section of the questionnaire asked about socio‐demographic characteristics, birth and feeding history. Following piloting, an additional verbal consent was added prior to the questions about seeing breastfeeding, as some women and health professionals found these unacceptable depending on their previous experiences or attitudes towards breastfeeding. Many women and professionals reported enjoying and valuing the discussions generated when completing the questionnaire.

A total of 351 women completed all 15 questions asking about attitudes towards recently witnessed breastfeeding. Each item comprised a five‐point Likert scale with responses ranging from ‘strongly agree’, ‘agree’, ‘unsure’, ‘disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’. After reverse coding of the appropriate items, the Cronbach's alpha was found to be 0.86. Data reduction techniques involved repeated sequential removal of each item and recalculation of the Cronbach's alpha until further removal of any item caused a detrimental impact on its magnitude. Five items remained with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.86: ‘I felt embarrassed seeing her breastfeed’, ‘I felt uncomfortable seeing her breastfeed’, ‘I do not know where to look’, ‘It was lovely to see her breastfeeding’, and ‘It didn't bother me seeing her breastfeed’. Inter‐item correlations were checked for redundancy and all were below ±0.70.

The test–retest reliability of the original 15 questions was also examined. A practice nurse, independent of the research team, invited childless women attending a general practice for a consultation about contraception to participate. The practice nurse completed the questionnaire with 30 women and repeated the process 8 weeks later. Three women were subsequently excluded because of incomplete questionnaires. For each of the 15 questions, the percentage agreement of answers between the two time points was calculated and varied from 59 to 96%. Reliability was further assessed using the Kappa statistic (or the marginal homogeneity test if Kappa could not be computed because of asymmetric tables). Because of the limited sample size, the answers to each of the 15 questions were first collapsed into a three‐point scale (‘strongly agree’/‘agree’, ‘unsure’, ‘disagree’/‘strongly disagree’). With the exception of a value of 0.21 (for the statement ‘I felt it was inappropriate for her to be breast feeding with other people present’), Kappa values showed significant agreement and ranged from 0.36 to 0.71.

How seeing breastfeeding relates to feeding intention and behaviour

Midwives collected feeding outcomes at birth, which were linked to feeding intention and seeing breastfeeding in the questionnaire described above. Health visitors gave a postal return maternal satisfaction questionnaire to all mothers who initiated breastfeeding when attending for their 6–8‐week baby check. The questionnaire consisted of the Maternal Breastfeeding Evaluation Scale (MBES) which has been validated and consists of three subscales: (1) maternal enjoyment and role attainment; (2) infant satisfaction and growth; and (3) lifestyle and body image (Leff et al. 1994). This tool was chosen as we hypothesized that higher scores in subscales (1) and (3) might be associated with more positive attitudes to seeing other women breastfeeding and seeing breastfeeding more often. Midwives and health visitors received training in questionnaire conduct and completion. All questionnaires had unique identifiers and were in an envelope, which was transferred from the midwifery records to the health visiting records after birth, then returned to a data manager.

Definitions and outcomes

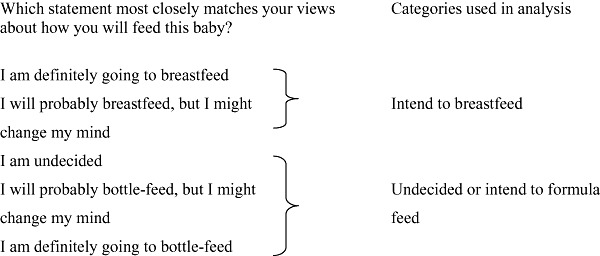

Our primary outcome was feeding intention. We used a five‐point classification of feeding intention (see Fig. 1), informed by earlier qualitative research (Hoddinott & Pill 1999). However, for the analysis, the five‐point scale was collapsed into two groups. Our secondary outcomes were breastfeeding initiation at birth and the MBES. Breastfeeding initiation was defined as any woman who has put her baby to the breast even if only once (Bolling et al. 2007). Breastfeeding outcomes were recorded as exclusive breast milk, breast and formula milk, or formula milk only. Exclusive breast milk was defined as no formula milk given to the baby ever. Any breastfeeding refers to women who exclusively breastfeed or breast and formula feed. Women were asked how long ago (months) they had last observed breastfeeding. We defined seeing breastfeeding within the 12 months prior to the antenatal booking appointment as recent. Reported frequencies for seeing relatives and friends breastfeeding were generally low in the study population. Therefore, several variables were merged and we created three new variables: (1) family (mother, sister, father's relatives, other relatives); (2) friends and/or colleagues; and (3) media (television or video).

Figure 1.

Categorization of infant feeding intention.

Statistical methods

All data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Science, Version 17.0. Demographic characteristics and previous breastfeeding behaviour were compared between women who had never breastfed before and those who had breastfed using the chi‐squared test (for categorical factors) and the independent two sample t‐test (for continuous factors).

Multiple binary logistic regression was used to examine the association between exposure history to breastfeeding, feelings around breastfeeding practices and each of feeding intention and feeding behaviour. Predictor variables were entered into the model if they were found to show an association in univariate analyses (using a conservative P ≤ 0.10 cut‐off). A forward stepwise procedure was used, and variables were subsequently removed if P ≥ 0.10.

Ethics approval was obtained from Grampian Ethics Committee, Scotland.

Results

Recruitment, participation and sample characteristics

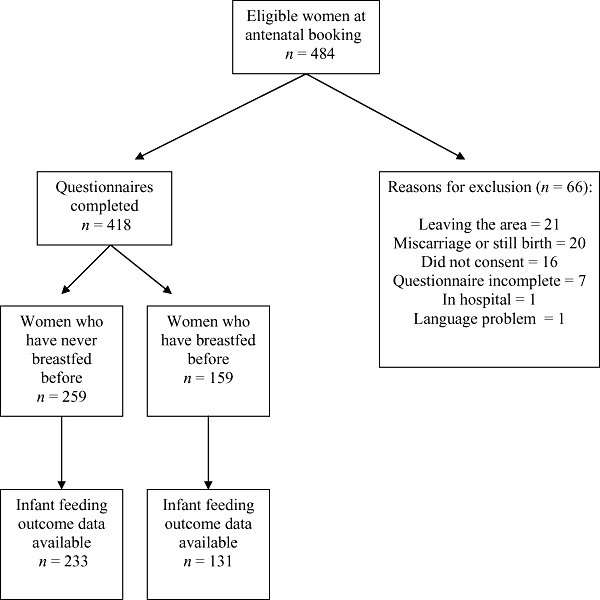

Midwives approached 484 women to complete the questionnaire, and 66 were excluded for various reasons (see Fig. 2). Of the participating 418 women, parity was missing for two women. One hundred and ninety women were primigravida, and 69 of the remaining 226 multiparous women had never breastfed before. Table 1 shows parity, maternal age, age at leaving full‐time education, birth method of delivery, feeding intention and feeding behaviour for the 418 study respondents. Women who had previously breastfed were significantly older (P < 0.001), more likely to intend to breastfeed at antenatal booking (P < 0.001) and to have had a normal vaginal delivery (P < 0.001). A total of 267 (64.5%) women intended to either definitely or probably breastfeed their expected baby. There was no significant difference in actual breastfeeding behaviour at birth between women who had previously breastfed and those who had not.

Figure 2.

Recruitment and participation.

Table 1.

Characteristics and previous breastfeeding behaviour of the 418 participating women

| At antenatal booking | Women who have never breastfed before (n = 259) | Women who have breastfed before (n = 159) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | |||

| Primiparous | 190 (71.7) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Multiparous | 75 (28.3) | 151 (100) | |

| Feeding intention | |||

| Definitely breastfeed | 90 (34.2) | 96 (63.6) | <0.001 |

| Probably breastfeed | 61 (23.2) | 20 (13.2) | |

| Undecided | 40 (15.2) | 13 (8.6) | |

| Probably bottle‐feed | 17 (6.5) | 10 (6.6) | |

| Definitely bottle‐feed | 55 (20.9) | 12 (7.9) | |

| Age at completion of full‐time education | |||

| Age 16 or under | 99 (43.6) | 47 (37.0) | 0.366 |

| Age 17 | 59 (26.0) | 44 (34.6) | |

| Age 18 | 31 (13.7) | 15 (11.8) | |

| Age 19 or over | 38 (16.7) | 21 (16.5) | |

| After birth | |||

| Method of delivery | |||

| Normal vaginal delivery | 152 (58.5) | 120 (80.5) | <0.001 |

| Forceps or ventouse | 54 (20.8) | 8 (5.4) | |

| Elective Caesarean | 18 (6.9) | 11 (7.4) | |

| Emergency Caesarean | 36 (13.8) | 10 (6.7) | |

| Feeding method at birth | |||

| Breastfeeding | 95 (39.7) | 45 (34.4) | 0.362 |

| Formula milk feeding | 144 (60.3) | 86 (65.6) | |

| Maternal age* | 26.8 (5.5) | 30.1 (4.6) | <0.01 |

Mean (standard deviation).

How women chose to feed previous babies is known to be a significant influence on how they choose to feed later babies (Bolling et al. 2007). As this would be likely to confound any relationship with seeing breastfeeding, all subsequent analyses were conducted on the 259 women who had never breastfed before. For these women, there was a significant association between intending to breastfeed and breastfeeding at birth (P < 0.01).

Seeing breastfeeding and how it relates to feeding intention and actual behaviour

Those aspects of seeing breastfeeding which were significantly associated with feeding intention on univariate analysis are listed in Table 2. Among women who had never breastfed, those who reported having seen breastfeeding (n = 191) were more likely to intend to breastfeed compared with women who reported never having seen breastfeeding [odds ratio (OR) 1.64, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.90–2.97]. Forty four per cent (n = 115) of women reported seeing breastfeeding within the previous 12 months and these women were more likely to intend to breastfeed (OR 1.46, 95% CI 0.87–2.41). The median age when breastfeeding was first seen was 12 years (minimum age 1 year and maximum age 34 years). Among the women who reported having seen breastfeeding, 26.6% (n = 48) stated this was age 11 or younger, and 73.4% (n = 133) stated this was age 12 or over. Women who agreed with the statements ‘I felt uncomfortable seeing her breastfeed’, ‘I felt embarrassed seeing her breastfeed’ or ‘I didn't know where to look’ were significantly less likely to intend to breastfeed. In contrast, women who agreed with the statement ‘It was lovely to see her breastfeed’ were significantly more likely to intend to breastfeed. The results of the forward stepwise model identified only one item to be a significant independent predictor of intention to breastfeed. Women who agreed with the statement ‘It was lovely to see her breastfeed’ were more than six times more likely to intend to breastfeed compared with women who disagreed with the statement (adjusted OR 6.72, 95% CI 2.85–15.82).

Table 2.

How women's exposure history and attitudes to most recently seen breastfeeding relate to infant feeding intention when pregnant for the 259 women who had never breastfed before

| Intention to breastfeed | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definitely or probably breastfeeding | Undecided or likely to bottle‐feed | Unadjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted odds ratio* (95% CI) | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||||

| Ever seen breastfeeding | ||||||||

| No | 28 | 19.3 | 29 | 26.1 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 117 | 80.7 | 74 | 66.7 | 1.64 | 0.90–2.97 | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 8 | 7.2 | – | – | ||

| Has seen breastfeeding in the last 12 months | ||||||||

| No | 74 | 51.0 | 67 | 60.4 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 71 | 49.0 | 44 | 39.6 | 1.46 | 0.87–2.41 | ||

| Age first seen breastfeeding | ||||||||

| ≤age 11 | 32 | 22.1 | 16 | 14.4 | 1.00 | |||

| ≥age 12 | 77 | 53.1 | 56 | 50.5 | 0.69 | 0.34–1.37 | ||

| Missing | 36 | 24.8 | 39 | 35.1 | 0.46 | 0.22–0.98 | ||

| Seen family member breastfeeding | ||||||||

| No | 46 | 31.7 | 36 | 32.4 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 40 | 27.6 | 17 | 15.3 | 1.84 | 0.90–3.77 | ||

| Missing | 59 | 40.7 | 58 | 52.3 | 0.80 | 0.45–1.40 | ||

| Has seen breastfeeding in media | ||||||||

| No | 35 | 24.1 | 30 | 27.0 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 110 | 75.9 | 81 | 73.0 | 1.16 | 0.66–2.05 | ||

| Age at completion of full‐time education | ||||||||

| Age 16 or under | 52 | 42.3 | 45 | 47.4 | 1.00 | |||

| Age 17 | 31 | 25.2 | 27 | 28.4 | 0.99 | 0.52–1.91 | ||

| Age 18 | 17 | 13.8 | 11 | 11.6 | 1.34 | 0.57–3.15 | ||

| Age 19 or over | 23 | 18.7 | 12 | 12.6 | 1.66 | 0.74–3.71 | ||

| Maternal age † | 27.0 (5.5) | 26.4 (5.5) | 1.02 | 0.97–1.07 | ||||

| I felt uncomfortable seeing her breastfeed | ||||||||

| Disagree | 105 | 82.0 | 56 | 65.1 | 1.00 | |||

| Unsure | 11 | 8.6 | 10 | 11.6 | 0.59 | 0.24–1.47 | ||

| Agree | 12 | 9.4 | 20 | 23.3 | 0.32 | 0.15–0.70 | ||

| It was lovely to see her breastfeeding | ||||||||

| Disagree | 16 | 12.5 | 27 | 31.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Unsure | 36 | 28.1 | 39 | 45.3 | 1.56 | 0.72–3.35 | 1.46 | 0.65–3.28 |

| Agree | 76 | 59.4 | 20 | 23.3 | 6.41 | 2.91–14.14 | 6.72 | 2.85–15.82 |

| I felt embarrassed seeing her breastfeed | ||||||||

| Disagree | 109 | 85.2 | 59 | 69.4 | 1.00 | |||

| Unsure | 8 | 6.3 | 7 | 8.2 | 0.62 | 0.21–1.79 | ||

| Agree | 11 | 8.6 | 19 | 22.4 | 0.31 | 0.14–0.70 | ||

| I do not know where to look | ||||||||

| Disagree | 106 | 82.8 | 50 | 58.1 | 1.00 | |||

| Unsure | 8 | 6.3 | 13 | 15.1 | 0.29 | 0.11–0.75 | ||

| Agree | 14 | 10.9 | 23 | 26.7 | 0.29 | 0.14–0.61 | ||

| It didn't bother me seeing her breastfeeding | ||||||||

| Disagree | 11 | 8.6 | 17 | 19.8 | 1.00 | |||

| Unsure | 3 | 2.3 | 8 | 9.3 | 0.58 | 0.13–2.67 | ||

| Agree | 114 | 89.1 | 61 | 70.9 | 2.89 | 1.27–6.56 | ||

CI, confidence interval; *from forward stepwise logistic regression; †mean (standard deviation).

Figures in bold are statistically significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Table 3 shows that women who were aged 12 or over when they first saw breastfeeding were more likely to initiate breastfeeding (OR 1.69 95% CI 0.83–3.42). Women who recalled seeing other women breastfeed either on television or in a video were more likely to initiate breastfeeding (OR 1.54, 95% CI 0.85–2.81). Interestingly, contrary to expectations, women who initiated breastfeeding were significantly younger than those who did not (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.89–0.98). Following the stepwise regression procedure, only two items were found to be significant independent predictors of initiating breastfeeding. Women who completed their full‐time education aged 17 were over three times more likely to initiate breastfeeding (OR 3.09, 95% CI 1.41–6.77) and those who completed their full‐time education aged 19 and over were more than seven times more likely to initiate breastfeeding (OR 7.41, 95% CI 2.51–21.94) compared with women who had completed full‐time education aged 16 and under. In addition, the statement ‘It was lovely to see her breastfeed’ was a significant predictor of initiating breastfeeding (P = 0.029).

Table 3.

How women's exposure history and attitudes to most recently seen breastfeeding relate to breastfeeding initiation after birth among the 259 women who had never breastfed before

| Initiated breastfeeding of this child at birth | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Unadjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted odds ratio* (95% CI) | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||||

| Ever seen breastfeeding | ||||||||

| No | 35 | 25.2 | 19 | 20.2 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 98 | 70.5 | 71 | 75.5 | 0.75 | 0.40–1.42 | ||

| Missing | 6 | 4.3 | 4 | 4.3 | 0.81 | 0.20–3.25 | ||

| Has seen breastfeeding in last 12 months | ||||||||

| No | 76 | 54.7 | 52 | 55.3 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 63 | 45.3 | 42 | 44.7 | 1.03 | 0.61–1.74 | ||

| Age first seen breastfeeding | ||||||||

| ≤age 11 | 20 | 14.4 | 22 | 23.4 | 1.00 | |||

| ≥age 12 | 72 | 51.8 | 47 | 50.0 | 1.69 | 0.83–3.42 | ||

| Missing | 47 | 33.8 | 25 | 26.6 | 2.07 | 0.95–4.49 | ||

| Seen family member breastfeeding | ||||||||

| No | 42 | 30.2 | 27 | 28.7 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 28 | 20.1 | 23 | 24.5 | 0.78 | 0.38–1.63 | ||

| Missing | 69 | 49.6 | 44 | 46.8 | 1.01 | 0.55–1.86 | ||

| Has seen breastfeeding in media | ||||||||

| No | 30 | 21.6 | 28 | 29.8 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 109 | 78.4 | 66 | 70.2 | 1.54 | 0.85–2.81 | ||

| Age at completion of full‐time education | ||||||||

| Age 16 or under | 43 | 32.6 | 55 | 61.8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Age 17 | 41 | 31.1 | 17 | 19.1 | 3.09 | 1.54–6.16 | 3.09 | 1.41–6.77 |

| Age 18 | 18 | 13.6 | 11 | 12.4 | 2.09 | 0.90–4.90 | 1.73 | 0.67–4.47 |

| Age 19 or over | 30 | 22.7 | 6 | 6.7 | 6.40 | 2.44–16.75 | 7.41 | 2.51–21.94 |

| Maternal age † | 25.9 (5.1) | 27.9 (5.8) | 0.93 | 0.89–0.98 | ||||

| I felt uncomfortable seeing her breastfeed | ||||||||

| Disagree | 84 | 73.7 | 57 | 72.2 | 1.00 | |||

| Unsure | 13 | 11.4 | 9 | 11.4 | 0.98 | 0.39–2.45 | ||

| Agree | 17 | 14.9 | 13 | 16.5 | 0.89 | 0.40–1.97 | ||

| It was lovely to see her breastfeeding | ||||||||

| Disagree | 24 | 21.1 | 16 | 20.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 † | ||

| Unsure | 48 | 42.1 | 20 | 25.3 | 1.60 | 0.71–3.63 | 1.79 | 0.75–4.31 |

| Agree | 42 | 36.8 | 43 | 54.4 | 0.65 | 0.30–1.40 | 0.66 | 0.29–1.51 |

| I felt embarrassed seeing her breastfeed | ||||||||

| Disagree | 88 | 77.9 | 60 | 75.9 | 1.00 | |||

| Unsure | 9 | 8.0 | 7 | 8.9 | 0.88 | 0.31–2.48 | ||

| Agree | 16 | 14.2 | 12 | 15.2 | 0.91 | 0.40–2.06 | ||

| I do not know where to look | ||||||||

| Disagree | 82 | 71.9 | 55 | 69.6 | 1.00 | |||

| Unsure | 12 | 10.5 | 8 | 10.1 | 1.01 | 0.39–2.62 | ||

| Agree | 20 | 17.5 | 16 | 20.3 | 0.84 | 0.40–1.76 | ||

| It didn't bother me seeing her breastfeeding | ||||||||

| Disagree | 14 | 12.3 | 11 | 13.9 | 1.00 | |||

| Unsure | 8 | 7.0 | 2 | 2.5 | 3.14 | 0.55–17.89 | ||

| Agree | 92 | 80.7 | 66 | 83.5 | 1.10 | 0.47–2.56 | ||

CI, confidence interval; *from forward stepwise logistic regression; †mean (standard deviation).

Figures in bold are statistically significant at P ≤ 0.05.

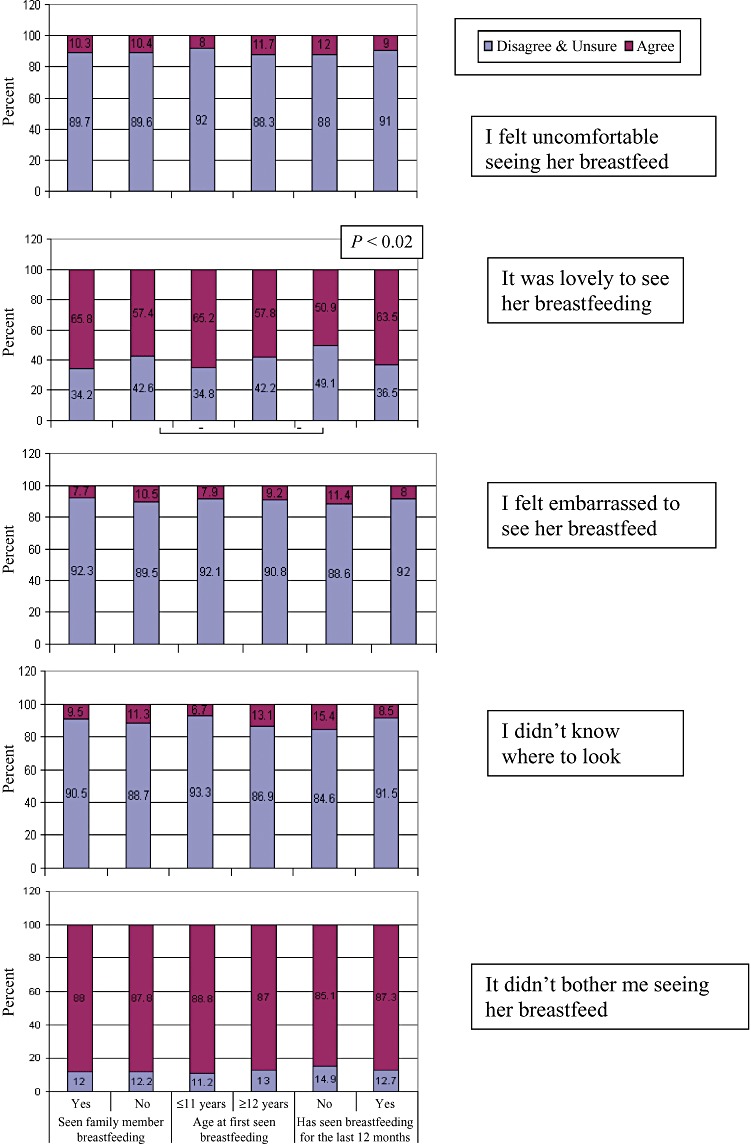

Attitudes towards seeing breastfeeding and their relationship to when and who was seen

The relationship between the five attitudes towards most recently seen breastfeeding and each of the timing of first recall of seeing breastfeeding, seeing breastfeeding in the preceding 12 months and seeing a family member breastfeed were then explored descriptively (Fig. 3). The only significant association was between women who agreed with the statement ‘It was lovely to see her breastfeed’ and reporting that they had seen breastfeeding in the previous 12 months (P = 0.02, data not shown).

Figure 3.

How breastfeeding exposure history relates to attitudes towards most recently seen breastfeeding among the 259 women who had never breastfed before.

Seeing breastfeeding and relationship to maternal breastfeeding satisfaction

Of the 259 women who had never breastfed before, 109 completed the MBES, a secondary outcome measure. We found no statistically significant differences in the median total MBES score among women who had seen breastfeeding, early age of exposure, frequent exposure or any of the four sources of exposure (family, known person, unknown person or media). Similarly, there were no differences in median scores for each of the three subscales in the MBES (data not shown).

Discussion

Our study suggests that how recently breastfeeding has been seen, age at first seeing breastfeeding and the relationship to the person seen are less important in influencing feeding intention and actual behaviour than the attitudes engendered when observing breastfeeding and age of completing full‐time education. Different forms of social modelling may have an impact at different times. If women agreed that ‘It was lovely to see her breastfeeding’ when describing their most recent experience of seeing breastfeeding, they were significantly more likely to intend to breastfeed, however, the relationship was less clear for breastfeeding initiation. Reporting seeing breastfeeding in the 12 months prior to becoming pregnant was significantly associated with agreeing with that ‘It was lovely to see her breastfeeding’. Seeing breastfeeding on television or on a video had no significant influence on feeding intention or behaviour. Age at leaving full‐time education was the strongest predictor of initiating breastfeeding. Older women who had never breastfed before, which included 69 multiparous women who had previously formula fed a baby or babies, were less likely to initiate breastfeeding, which is counter to most published data for all primigravidae and multiparous women (Bolling et al. 2007; Chalmers & McInnes 2006). It is probably not surprising that there was no association between maternal satisfaction and seeing breastfeeding at 6–8 weeks, as there are so many other known and unknown confounding factors, including health service care and experiences, other measures of disadvantage besides age at leaving full‐time education and cultural factors.

Methodological limitations

The study took place in a rural area of Scotland, which has below average breastfeeding rates and rurality may influence the opportunities women have for seeing breastfeeding. The levels of reported exposure to breastfeeding may therefore be lower than other areas of the UK or other developed countries. Known and unknown confounding factors are a major limitation of this study, as breastfeeding intention and behaviour are known to be associated with maternal age, educational level and how the mother herself was fed (Bolling et al. 2007). Infant feeding decisions are complex, and attempting to isolate the variable ‘seeing breastfeeding’ has limitations. We did not perform a formal sample size calculation prior to this study, and it is likely that this study is actually underpowered to examine associations between some of the variables reported. This study was conducted during an action research project, which aimed to increase breastfeeding rates, and this increased the focus on breastfeeding within the locality (Hoddinott et al. 2006). This could have influenced our data. There is likely to be selection bias because of several factors: women who do not speak English as their first language, women with learning difficulties and women who default from antenatal care will be under‐represented.

The five‐item Seeing Breastfeeding Scale has potential, but requires further testing and validation, particularly as the attitudinal variables were derived from a sample of early school leavers. Limitations include: several midwives administering the questionnaires during routine care; missing data for some questions; and a possibility that women might have felt pressurized to comply. However, we did not receive any feedback to support this latter concern. As this was part of an action research study (Hoddinott et al. 2006), the ethical conduct of the study was discussed at steering group meetings. Every effort was made to minimize pressure and a second consent was included prior to the seeing breastfeeding questions, to allow women to opt out if they so wished. Non‐responders to questions about seeing breastfeeding may have felt embarrassed when answering them. Overall, informal feedback from women and midwives was positive, particularly the value of discussing feeding experiences of friends and family. In fact, after study completion, several midwives reported their intention to continue to discuss experiences of seeing breastfeeding to help assess a woman's breastfeeding support needs.

Studies that have investigated recall of direct breastfeeding experience have shown that this is reliable (Launer et al. 1992), however, we were investigating vicarious experience, and the reliability of recall for this is unknown. It is possible that women who are more interested in breastfeeding are more likely to recall seeing other mothers' breastfeeding. Unfortunately, we were only able to reliably collect breastfeeding exposure at antenatal booking. We attempted to collect data immediately after birth to capture exposure during pregnancy. However, this proved not to be feasible in terms of low response rates on the post‐natal ward and unreliability because some women found it difficult to accurately recall whether exposure had taken place before or after completing the first questionnaire. A prospective exposure diary during pregnancy would be preferable. Content analysis of British television programmes has revealed that the media rarely presents positive information or images of breastfeeding (Henderson et al. 2000). Any future research should also examine other media, such as DVD and the Internet, and differentiate among educational materials, advertisements and entertainment. This is particularly important in the light of a UK television documentary focusing on breastfeeding older children, which was considered off‐putting by many (Trotter 2006).

Implications for policy and practice

Our study suggests that more focus should be given to addressing the feelings invoked by seeing other women breastfeeding in women of childbearing age and in pregnancy. Initiatives, which provide opportunities for women of childbearing age to get to know and observe breastfeeding mothers, should aim to increase positive attitudes and future research should evaluate the most effective ways to achieve this. Organizing health care to run antenatal and post‐natal clinics concurrently could maximize opportunities for informal networking and peer support between breastfeeding mothers and pregnant women. The Baby Café Projects in England are an example of a community intervention where positive attitudes to seeing breastfeeding may be encouraged (Abbott et al. 2006). It remains unclear whether media‐based campaigns are as effective in raising the likelihood of breastfeeding as known social role models to the women. Multiple methods may be useful to overall enhance the breastfeeding rates, but it may be a matter of timing when to use different forms of social messaging.

Dykes (2006) has highlighted the importance of integrating embodied, vicarious, practice‐based and theoretical knowledge when educating health practitioners about breastfeeding and recommends critical reflection in this area. Asking women whether they have seen breastfeeding, who, when and how they felt about it is feasible as part of routine antenatal care. It can provide relevant information about feeding intention and likely outcome, and provide opportunities to discuss sensitive issues like embarrassment. It can highlight women who may require additional support when learning how to breastfeed and those with social networks with little direct or vicarious experience of breastfeeding.

There is potential for using the SBS to evaluate policies and initiatives that increase the visibility of breastfeeding, and to monitor how attitudes change over time. Recent examples of such policies would be the Breastfeeding (Scotland) Act 2005, which protects women's right to breastfeed in public and breastfeeding television advertisements (National Health Service 2008). Similarly, there is uncertainty about the most effective age to implement the recommendations to promote breastfeeding in schools (Renfrew et al. 2005). Encouraging known mothers of pupils to breastfeed in primary school classrooms is feasible and justifies further evaluation (Russell et al. 2004). The evidence that exposure to smoking both in family members and in movies increases the incidence of smoking in children as young as 9 years old provides evidence that vicarious experience can influence behaviour at this stage (Titus‐Ernstoff et al. 2008). Further studies of exposure to breastfeeding both in real life and through television and other visual media are needed.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest have been declared.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the National Health Service (NHS) Grampian who funded this study; the Chief Scientist's Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorate, who funded Pat Hoddinott through the research practice scheme and a Primary Care Research Career Award; and the Alliance for Self Care Research, who partly funds Thilo Kroll. We would also like to thank Kirsten Coady, practice nurse at Macduff Medical Practice; Maretta Chalmers, research training midwife; all the midwives, health visitors and women in Banff and Buchan who were involved in collecting or contributing data for this study; Gail Cowie for data management; Professor Roisin Pill (Department of Primary Care, University of Wales) and Professor Dave Godden, Director of the Centre for Rural Health, University of Aberdeen, who provided advice at several stages of the study; and Manimekalai Thiruvothiyur Kesavan, statistician at the Centre for Rural Health, University of Aberdeen, who provided initial statistical support and cleaned the data.

Key messages

-

•

The ‘Seeing Breastfeeding’ Scale consists of five attitudes to most recently observed breastfeeding and warrants further testing.

-

•

The most important predictor of intending to breastfeed was the woman's attitude to her most recent experience of seeing breastfeeding. This was more important than either reported age of first seeing breastfeeding or the woman's relationship to the person seen.

-

•

Women who agreed with the statement ‘It was lovely to see her breastfeed’ were more than six times more likely to intend to breastfeed compared with women who disagreed with the statement.

-

•

Age at completing full‐time education was the strongest predictor of breastfeeding initiation.

-

•

Women who report seeing breastfeeding in the 12 months prior to becoming pregnant were more likely to agree with the statement ‘It was lovely to see her breastfeed’.

Footnotes

The Seeing Breastfeeding Scale is available on request from Pat Hoddinott.

References

- Abbott S., Renfrew M.J. & Mcfadden A. (2006) ‘Informal’ learning to support breastfeeding: local problems and opportunities. Maternal & Child Nutrition 2, 232–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1977) Self‐efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychological Review 84, 191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolling K., Grant K., Hamlyn B. & Thornton A. (2007) Infant Feeding Survey 2005. The Information Centre, Government Statistical Service: London. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers J., Mcinnes R., Hoddinott P. & Alder E. (2007) A systematic review of measures assessing mothers' knowledge, attitudes, confidence and satisfaction towards breastfeeding. Breastfeeding Review 15, 17–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers J. & McInnes R. on behalf of the Breastfeeding Expert Group (BEG) convened by NHS Health Scotland in partnership with the Health Improvement Strategy Division, Scottish Executive (2006) Psychosocial Factors Associated with Breastfeeding: A Review of Breastfeeding Publications Between 1990–2005. NHS Health Scotland: Edinburgh. [Google Scholar]

- Collins D. (2003) Pretesting survey instruments: an overview of cognitive methods. Quality of Life Research 12, 229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolley C., Friel S., Gabhainn S., Becker G. & Kelleher C.C. (1998) Attitudes of young men and women to breastfeeding. Irish Medical Journal 91, 1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis C.L. (2003) The breastfeeding self‐efficacy scale: psychometric assessment of the short form. Journal of Obstetric, Gynaecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 32, 734–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewan N., Wood L., Maxwell S., Cooper C. & Brabin B. (2002) Breast‐feeding knowledge and attitudes of teenage mothers in Liverpool. Journal of Human Nutrition & Dietetics 15, 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykes F. (2006) The education of health practitioners supporting breastfeeding women: time for critical reflection. Maternal & Child Nutrition 2, 204–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson L., McCormick F. & Renfrew M.J. (2005) Interventions for promoting the initiation of breastfeeding. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2, CD001688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick C.C., Fitzpatrick P.E. & Darling M.R.N. (1994) Factors associated with the decision to breastfeed among Irish women. Irish Medical Journal 87, 145–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene J., Stewart‐Knox B. & Wright M. (2003) Feeding preferences and attitudes to breastfeeding and its promotion among teenagers in Northern Ireland. Journal of Human Lactation 19, 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson L., Kitzinger J. & Green J. (2000) Representing infant feeding: content analysis of British media portrayals of bottle feeding and breast feeding. British Medical Journal 321, 1196–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott P., Lee A.J. & Pill R. (2006) Effectiveness of a breastfeeding peer coaching intervention in rural Scotland. Birth 33, 27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott P. & Pill R. (1999) Qualitative study of decisions about infant feeding among women in east end of London. British Medical Journal 318, 30–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horta B.L., Bahl R., Martines J.C. & Victora C.G. (2007) Evidence of the Long‐Term Effects of Breastfeeding. World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Ip S., Cheung M., Raman G., Chew P., Magula N., Devine D. et al. (2007) Breastfeeding and Maternal and Infant Health Outcomes in Developed Countries. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke J.R. (1994) Development of the breast feeding attrition prediction tool. Nursing Research 43, 100–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launer L.J., Forman M.R., Hundt G.L., Sarov B., Chang D., Berendes H.W. et al. (1992) Maternal recall of feeding events is accurate. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 46, 203–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff E.W., Jefferis R.N. & Gagne M.P. (1994) The development of the Maternal Breastfeeding Evaluation Scale. Journal of Human Lactation 10, 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service (2008) Breastfeeding – what could be more natural? Available at: http://www.breastfeeding.nhs.uk/en/fe/page.asp?n1=2&n2=7 (accessed 20 March 2009).

- Renfrew M., Dyson L., Wallace L., D'Souza L., McCormick F. & Spiby H. (2005) The Effectiveness of Public Health Interventions to Promote the Duration of Breastfeeding. A Systematic Review. National Institute of Clinical Excellence: London. [Google Scholar]

- Renfrew M.J., Spiby H., D'Souza L., Wallace L.M., Dyson L. & McCormick F. (2007) Rethinking research in breast‐feeding: a critique of the evidence base identified in a systematic review of interventions to promote and support breast‐feeding. Public Health Nutrition 10, 726–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell B., Richards H., Jones A. & Hoddinott P. (2004) ‘Breakfast, lunch and dinner’: attitudes to infant feeding amongst children in a Scottish primary school. A qualitative focus group study. Health Education Journal 63, 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Titus‐Ernstoff L., Dalton M.A., Adachi‐Mejia A.M., Longacre M.R. & Beach M.L. (2008) Longitudinal study of viewing smoking in movies and initiation of smoking by children. Pediatrics 121, 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotter S. (2006) Extraordinary opportunity. RCM Midwives Journal 9, 200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]